Advanced Motion Correction Strategies for Large-Scale Neuroimaging: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Motion artifacts present a significant challenge to the reliability and reproducibility of large-scale neuroimaging studies, particularly in pediatric and clinical populations.

Advanced Motion Correction Strategies for Large-Scale Neuroimaging: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

Motion artifacts present a significant challenge to the reliability and reproducibility of large-scale neuroimaging studies, particularly in pediatric and clinical populations. This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern motion correction strategies, from foundational concepts to advanced applications. We explore the critical trade-offs between prospective and retrospective methods, hardware-based and data-driven software solutions, and their implementation in multi-site research. The content details robust analytical frameworks for handling imperfect data, offers optimization strategies for study design, and presents rigorous validation protocols for comparing traditional and AI-based techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current evidence and practical recommendations to enhance data quality, accelerate discovery, and improve the clinical utility of neuroimaging biomarkers.

Understanding the Motion Problem: Scale, Impact, and Fundamental Challenges in Neuroimaging

Head motion is a significant confounding variable in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that can compromise data quality and lead to erroneous research findings and clinical interpretations. Between 10-15% of all MRI scans need to be repeated due to excessive motion, with even higher rates in young children and individuals with disabilities [1]. Motion introduces various artifacts including blurring, ghosting, and ringing in images, which subsequently affect derived metrics such as cortical thickness, regional volumes, and functional connectivity estimates [2].

This technical guide addresses the characterization of motion across different populations and provides evidence-based troubleshooting methodologies for researchers conducting large-scale neuroimaging studies.

Quantitative Characterization of Motion Across Populations

Motion Prevalence by Age and Clinical Status

Table 1: Motion Prevalence and Characteristics Across Demographic and Clinical Groups

| Population Group | Relative Motion Level | Key Characteristics | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children (5-10 years) | Highest | Exhibits the most movement in scanner; nonlinear cortical thickness associations disappear with stringent QC | [2] |

| Adolescents | Moderate | Dynamic brain development; motion shows test-retest reliability | [2] |

| Adults | Lower | Generally better motion control; intermediate rates of incidental findings | [3] |

| Older Adults (>40 years) | Increased | Higher motion returns; highest rates of incidental findings (54.9%) | [3] [2] |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | Significantly elevated | Increased motion compared to controls; affects cortical thickness measurements | [2] |

| ADHD | Significantly elevated | Motion-related symptoms manifest as increased head movement | [2] |

| Psychotic Disorders | Significantly elevated | Reduced cortical thickness effect sizes attenuate when motion accounted for | [2] |

Quantitative Impact of Motion on Data Quality

Table 2: Motion Impact on Neuroimaging Metrics and Outcomes

| Metric | Impact of Motion | Clinical/Research Consequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Thickness | Overestimation of thinning | Spurious neurodevelopmental trajectories | [2] |

| Grey Matter Volumes | Significant negative association | Misinterpretation of structural differences | [2] |

| White Matter Metrics | Weakened age correlations | Altered developmental trajectories | [2] |

| Functional Connectivity | Increased spurious correlations | Invalid network connectivity patterns | [2] |

| Incidental Finding Rates | No significant association | Clinical findings not obscured by motion | [3] |

| Prediction Accuracy | Decreased reliability | Reduced brain-age prediction accuracy | [4] |

Frequently Asked Questions: Motion Characterization

Q1: How does motion prevalence differ between children and adults in neuroimaging studies?

Motion follows a U-shaped curve across the lifespan. Children aged 5-10 years exhibit the most movement, with decreasing motion through adolescence and adulthood, followed by increased motion again in older adults (>40 years) [2]. One large-scale study found that while 9.6% of children have incidental findings on MRI, this increases to 54.9% in adults, though motion itself doesn't significantly affect the detection of these clinical findings [3].

Q2: Which clinical populations show elevated motion levels and how does this affect data interpretation?

Patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and psychotic disorders (bipolar disorder and schizophrenia) consistently exhibit significantly increased motion compared to healthy controls [2]. This motion difference can confound clinical interpretations - for example, early studies of ASD that did not adequately control for motion found no cortical thickness differences, while subsequent studies with stringent motion correction revealed significantly thicker cortex in ASD participants, aligning with histological evidence [2].

Q3: What is the quantitative impact of motion on cortical thickness measurements?

Motion produces a systematic bias toward thinner cortical measurements. Research has demonstrated that without adequate motion correction, reported nonlinear cortical thickness associations with age disappear when more stringent quality control is applied [2]. The direction of this bias is particularly problematic for case-control studies of clinical populations, as those groups that move more (such as ASD and ADHD) will appear to have artificially thinner cortex, potentially masking true neurobiological differences.

Q4: How does motion affect functional connectivity measures?

Motion increases the proportion of spurious correlations throughout the brain in functional MRI data [2]. The effects are complex and variable depending on the type of motion, but generally inflate short-distance correlations while reducing long-distance correlations. This artifact is particularly problematic because it can create systematic differences between groups that differ in motion levels, such as clinical populations versus healthy controls.

Q5: Can motion artifacts be adequately corrected through post-processing alone?

While numerous post-processing approaches exist, evidence suggests that prospective correction (during acquisition) provides superior results. As noted by researchers, "sedation is not allowed for research studies involving MRI scans" [1], necessitating alternative motion compensation strategies. Modern approaches like the MPnRAGE technique can effectively minimize artifacts and transform previously unusable scans into clinically useful images [1].

Experimental Protocols for Motion Characterization

Protocol for Quantifying Motion in Large-Scale Studies

Purpose: To standardize motion quantification across multiple sites and scanner platforms for large-scale neuroimaging studies.

Equipment and Software:

- MRI scanner with compatible motion tracking (e.g., volumetric navigators, optical tracking)

- Automated image processing pipeline (e.g., Freesurfer for Euler number calculation)

- Motion parameter estimation tools (FSL mcflirt, AFNI 3dvolreg, or SPM realign)

Procedure:

- Acquire structural and functional images using standardized protocols

- Extract motion parameters (6 rigid-body parameters: x, y, z translations and rotations)

- Calculate quantitative metrics:

- Euler number from Freesurfer processing [3]

- Frame-wise displacement from functional time series

- Root mean square of motion parameters

- Apply quality control thresholds based on study requirements

- Correlate motion metrics with demographic and clinical variables

Validation: Compare quantitative motion metrics with radiologist-reported motion ratings to ensure clinical relevance [3].

Protocol for Motion Characterization Across Development

Purpose: To characterize typical motion patterns across developmental stages from childhood through older adulthood.

Participant Groups:

- Children (5-10 years), Adolescents (11-19 years), Young Adults (20-39 years), Middle-aged Adults (40-64 years), Older Adults (65+ years)

Procedure:

- Acquire T1-weighted structural images and resting-state fMRI

- Compute motion estimates for all participants

- Group participants by age decades and clinical status

- Compare motion parameters across groups using ANOVA with post-hoc tests

- Assess test-retest reliability in longitudinal subsets

Analysis: Model motion as a function of age using both linear and nonlinear (quadratic) models to capture the U-shaped relationship [2].

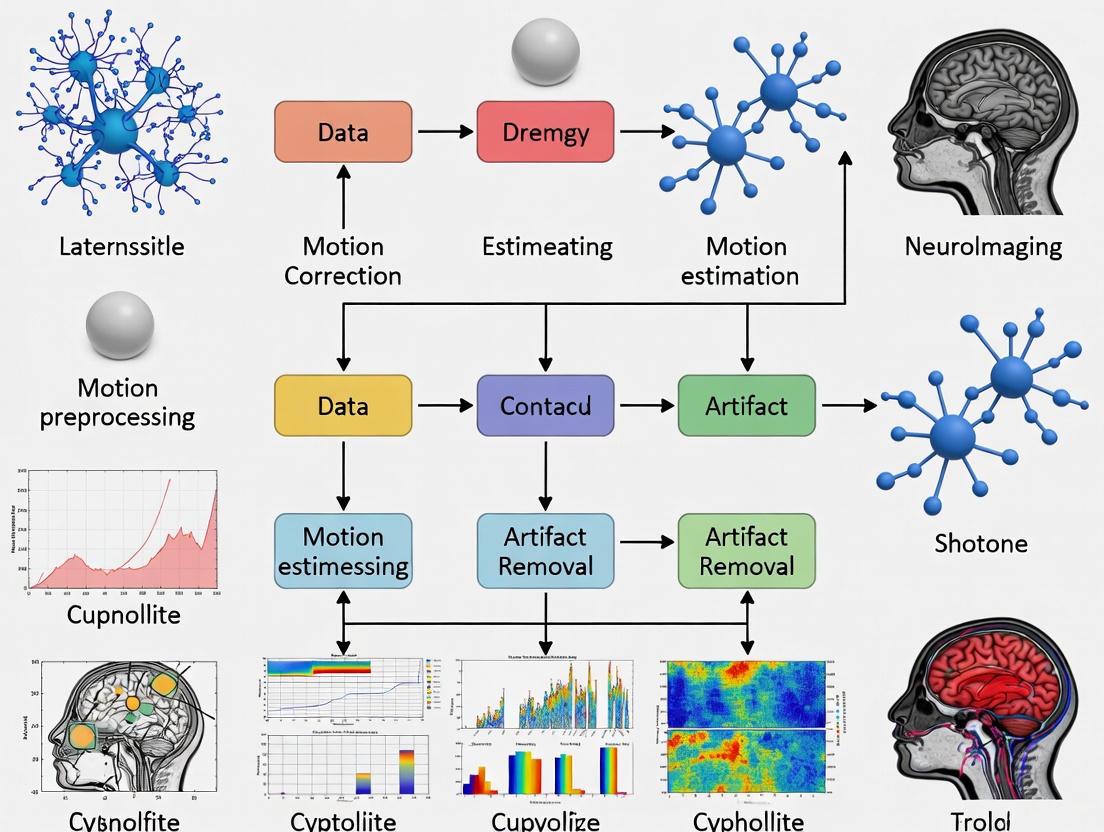

Motion Characterization Workflow

Diagram 1: Comprehensive motion characterization workflow for large-scale studies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Methods for Motion Characterization and Correction

| Tool/Method | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euler Number | Quantitative Metric | Automated motion quantification from structural images | Large-scale studies requiring automated QC [3] |

| FSL mcflirt | Software Tool | Motion parameter estimation and correction | Functional MRI preprocessing [5] |

| Volumetric Navigators | Prospective Correction | Real-time motion tracking and correction | High-resolution angiography and structural imaging [6] |

| MPnRAGE | Pulse Sequence | Motion-robust structural imaging | Studies with populations prone to movement [1] |

| HERON Pipeline | AI-Driven Framework | Real-time motion assessment and re-acquisition | Fetal MRI and challenging populations [7] |

| 3DMC Algorithms | Retrospective Correction | Post-acquisition image realignment | Standard functional and structural processing [8] |

| Motion Covariates | Statistical Control | GLM incorporation of motion parameters | Removing residual motion artifacts in fMRI [5] |

Motion Correction Decision Pathway

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for motion management strategies based on population characteristics

Quantifying the pervasiveness of motion across age and clinical populations is essential for valid neuroimaging research. The evidence demonstrates clear demographic and clinical patterns in motion characteristics, with children, older adults, and individuals with neuropsychiatric conditions exhibiting elevated motion that systematically biases research findings. Implementation of the characterization protocols, troubleshooting guides, and decision pathways outlined in this technical support document will enhance the reliability and validity of large-scale neuroimaging studies.

The Direct Impact of Motion on Data Quality and Statistical Power

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Motion Artifacts in Structural and Functional MRI

Problem: A structural MRI scan appears to have no major motion artifacts upon visual inspection, but subsequent morphometric analysis (e.g., cortical thickness or gray matter volume) shows significant bias and high variance, potentially confounding group-level statistics.

Explanation: Even subtle, "unnoticeable" motion can introduce systematic biases in morphometric analyses. When motion patterns differ between patient and control groups, this creates a significant confound, leading to erroneous conclusions about group differences [9]. Motion induces inconsistencies in k-space data, which after Fourier reconstruction, manifest as blurring, ghosting, or signal loss [10].

Solution:

- Step 1: Quantify Motion. Do not rely on visual inspection alone. Use the motion parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) generated by your scanner or preprocessing software to quantify the maximum displacement and mean framewise displacement for each subject [11].

- Step 2: Implement Prospective Motion Correction (if available). If your scanner is equipped with a system like volumetric navigators (vNavs), use it. vNavs track the subject's head and update the imaging coordinates in real-time, significantly reducing motion-induced bias and variance in morphometry [9].

- Step 3: Aggressive Data Scrubbing. For datasets already acquired, implement stringent motion censoring. Identify and remove volumes with framewise displacement exceeding a strict threshold (e.g., 0.2 mm). In severe cases, exclude subjects with excessive motion from the analysis [9].

- Step 4: Include Motion Parameters as Covariates. In your statistical model (e.g., GLM for fMRI), include the motion parameters as regressors of no interest to account for residual variance related to head motion [11].

Prevention:

- Use comfortable but effective head immobilization (pads, tape).

- For patient populations prone to movement, prioritize sequences with built-in prospective motion correction.

- Provide clear instructions to subjects and practice staying still before the scan.

Guide 2: Addressing Motion Corruption in Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS)

Problem: Single Voxel Spectroscopy (SVS) data shows poor spectral quality—broadened linewidth, low signal-to-noise, or unexplained lipid contamination—making metabolite quantification unreliable.

Explanation: MRS is exceptionally susceptible to motion because it requires long scan times and excellent B0 field homogeneity. Motion causes two primary issues: (1) incorrect voxel placement, leading to signals from outside the region of interest, and (2) degradation of B0 shimming, which broadens spectral lines and reduces resolution [12].

Solution:

- Step 1: Detect Corruption. For SVS, if data is acquired as a series of transients, inspect the individual transients for frequency and phase shifts. Spectroscopic imaging may show obvious spatial smearing [12].

- Step 2: Re-shim During Acquisition. The most effective solution is prospective correction with an internal navigator that can update both the voxel position and the B0 shim in real-time. This corrects for both localization and field homogeneity errors caused by motion [12].

- Step 3: Post-Processing Correction. If real-time correction is not available, use retrospective methods. This can include discarding motion-corrupted transients and performing spectral alignment (frequency and phase correction) on the remaining transients. Note that this cannot correct for the fact that data is averaged from different spatial locations [12].

Prevention:

- Use vendor-provided or custom prospective motion correction packages for MRS sequences.

- Minimize scan time where possible without compromising SNR.

- Ensure subjects are comfortably immobilized.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does motion reduce the statistical power of my fMRI study, even after motion correction?

Motion reduces statistical power primarily by increasing variance in the data. Motion artifacts add noise to the time series, which increases the residuals in your General Linear Model (GLM). Since statistical significance depends on the signal-to-noise ratio, higher noise reduces your ability to detect true activation [11]. While motion correction algorithms realign data and including motion parameters as covariates can help, they are imperfect and cannot fully reverse all spin history and magnetic field effects [11]. Therefore, the most effective strategy is to prevent motion from occurring in the first place.

FAQ 2: What is the difference between prospective and retrospective motion correction, and which should I use?

- Prospective Motion Correction: Motion is tracked during the scan (using cameras, MR markers, or navigators), and the imaging sequence is adaptively updated in real-time to follow the head's movement. The main advantage is that it acquires consistent, motion-free data from the start [9] [13].

- Retrospective Motion Correction: Motion is estimated after the scan from the acquired data itself, and corrections are applied during image reconstruction. This is more widely available but can be suboptimal as it cannot fully correct for spin history effects or changes in the magnetic field [10] [13].

You should use prospective correction whenever possible, as it directly addresses the root of the problem. Retrospective methods are a valuable fallback for existing data but are generally considered less comprehensive [13].

FAQ 3: We are planning a large-scale neuroimaging study. What is the minimum motion correction protocol we should implement?

For a large-scale study, a multi-layered approach is critical:

- Prevention: Standardize subject immobilization and communication across all sites.

- Prospective Correction: Mandate the use of prospective motion correction (e.g., vNavs, optical tracking) for all high-resolution structural and critical functional sequences [9].

- Quality Control: Implement an automated, quantitative motion assessment pipeline. Define clear, pre-registered exclusion criteria based on metrics like mean framewise displacement [9].

- Statistical Control: In your group-level analyses, include summary motion metrics as covariates to account for residual effects of motion across subjects.

FAQ 4: Can new Deep Learning methods correct for motion without the need for specialized hardware?

Yes, deep learning is a promising approach for retrospective motion correction directly in the image domain. Models like PI-MoCoNet and Res-MoCoDiff use architectures like U-Nets with Swin Transformer blocks to learn a mapping from motion-corrupted to motion-free images, leveraging both spatial and k-space information [14] [15]. These methods have shown significant improvements in metrics like PSNR and SSIM and have the advantage of not requiring raw k-space data or scanner modifications [14]. However, they require training on large datasets and there is a risk of "hallucinating" image features, so validation in a clinical context is ongoing.

Quantitative Data on Motion's Impact

Table 1: Impact of Motion and Correction on MRI Image Quality Metrics (Simulated Data)

| Motion Severity | Condition | PSNR (dB) | SSIM | NMSE (%) | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Motion-Corrupted | 34.15 | 0.87 | 0.55 | IXI [15] |

| After PI-MoCoNet Correction | 45.95 | 1.00 | 0.04 | ||

| Moderate | Motion-Corrupted | 30.23 | 0.80 | 1.32 | IXI [15] |

| After PI-MoCoNet Correction | 42.16 | 0.99 | 0.09 | ||

| Heavy | Motion-Corrupted | 27.99 | 0.75 | 2.21 | IXI [15] |

| After PI-MoCoNet Correction | 36.01 | 0.97 | 0.36 |

Table 2: Performance of Different Motion Correction Methods on a Clinical Dataset (MR-ART)

| Correction Method | PSNR (dB) | SSIM | NMSE (%) | Inference Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Correction (Low Artifact) | 23.15 | 0.72 | 10.08 | N/A |

| PI-MoCoNet (Low Artifact) | 33.01 | 0.87 | 6.24 | ~0.37s per batch [15] |

| No Correction (High Artifact) | 21.23 | 0.63 | 14.77 | N/A |

| PI-MoCoNet (High Artifact) | 31.72 | 0.83 | 8.32 | ~0.37s per batch [15] |

| Res-MoCoDiff (Various) | Up to 41.91 | Superior SSIM | Lowest NMSE | 0.37s per batch [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Correction

Protocol A: Implementing Prospective Motion Correction with Volumetric Navigators (vNavs)

Purpose: To acquire structural MRI data (e.g., MPRAGE) with reduced motion-induced bias for brain morphometry.

Methodology:

- Sequence Modification: Embed a low-resolution volumetric navigator (vNav) into the dead time of the pulse sequence, typically once per TR. Each vNav acquires a 3D head volume in approximately 300 ms [9].

- Real-time Tracking: The vNav volumes are rapidly registered to a reference volume to estimate the subject's head position (6 degrees of freedom) [9].

- Prospective Update: The estimated motion parameters are used to update the imaging plane and frequency of the subsequent TR in real-time, ensuring data is acquired in head-relative coordinates [9].

- Retrospective Reacquisition (Optional): The system can be set to automatically reacquire TRs that are determined to have been severely motion-degraded based on the motion estimates, providing a further reduction in artifacts [9].

Key Parameters:

- vNav resolution: Typically isotropic ~8-16 mm.

- vNav update rate: Once per TR (e.g., every 2-3 seconds).

- Reacquisition threshold: Define a motion threshold beyond which data is reacquired.

Protocol B: Data-Driven Motion Correction for fMRI using GLM Covariates

Purpose: To mitigate the effects of residual motion on the statistical analysis of fMRI data after volume realignment.

Methodology:

- Motion Estimation: During preprocessing, a rigid-body registration algorithm (e.g., FSL FLIRT, SPM realign) is used to align each volume to a reference volume (often the first one), producing 6 time series (3 translations, 3 rotations) that parameterize the head motion [11].

- Noise Regression: In the General Linear Model (GLM) set up for the fMRI time series, include the 6 motion parameters as predictors of no interest (regressors). This accounts for variance in the signal that is linearly related to head motion [11].

- Extended Model (Recommended): To further reduce motion-related noise, also include the temporal derivatives of the 6 motion parameters, and the time points identified as "motion outliers" (e.g., using Framewise Displacement) as additional regressors.

Visual Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Motion Correction in Neuroimaging Research

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Navigators (vNavs) | MR-based Tracking | Embedded low-resolution 3D scans to track head pose and update imaging coordinates prospectively. | Reduces bias in morphometry; adds minimal scan time [9]. |

| Optical Motion Tracking | External Tracking | Camera system tracks markers on the subject's head to provide high-frame-rate pose data. | High precision; can be obstructed by RF coils at ultra-high field [10] [13]. |

| FID Navigators | MR-based Tracking | Rapid Free Induction Decay signals to detect motion without prolonging scan time. | Can be used for automated image quality prediction and early scan termination [16]. |

| Swin Transformer U-Net | Deep Learning Model | Neural network architecture for image restoration; excels at capturing long-range dependencies for artifact removal. | Core component of modern DL correction models like PI-MoCoNet and Res-MoCoDiff [14] [15]. |

| Data Consistency Loss | Algorithmic Component | A loss function used in DL training that enforces fidelity between the corrected image and the original k-space data. | Prevents image "hallucinations" and ensures physically plausible corrections [15]. |

| PROPELLER/MULTIBLADE | Self-Navigating Sequence | K-space sampling with rotating blades where the center of each blade acts as a navigator. | Enables motion detection and correction without external hardware [13]. |

Special Challenges in Pediatric and Neurodegenerative Disease Cohorts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is head motion a more critical confound in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorder studies?

Head motion is a critical confound because it does not introduce random noise but rather spatially structured artifacts that can mimic or obscure genuine neurobiological effects. Specifically, motion adds spurious signal that is more similar at nearby voxels than at distant ones, creating a distance-dependent modulation of correlations in functional MRI (fMRI) [17]. This is particularly problematic when studying neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) or neurodegenerative diseases, as these patient populations often move more in the scanner than healthy control groups. Consequently, observed group differences in connectivity—such as the "underconnectivity" reported in children, the elderly, or autistic individuals—can be at least partially attributable to this motion artifact rather than the biology of the disorder itself [17] [18].

Q2: What are the specific challenges in normalizing brain images from pediatric cohorts?

A primary challenge is the use of standard brain templates, like those from the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI), which are based on adult brains. Normalizing a child's brain to an adult template can introduce significant inaccuracies because children's brains are structurally different; their skulls are thinner, sinuses are not fully formed, and there is less space for cerebrospinal fluid around the brain [18]. Furthermore, childhood and adolescence are periods of dynamic neurodevelopment, with whole-brain volume growing by approximately 25%, gray matter by 13%, and white matter by a remarkable 74% [18]. Using an adult template fails to account for these rapid and non-linear developmental changes, potentially leading to misalignment and misinterpretation of data.

Q3: How can motion artifacts bias structural MRI analyses, such as T1-weighted scans?

In structural T1-weighted MRI, even small, visually undetectable head motions can create imaging artifacts that systematically reduce estimates of gray matter volume [19]. This poses a severe problem for neuromorphometric studies, as motion is often correlated with variables of interest. For example, since older adults or individuals with certain neurological conditions may move more, the observed reductions in their gray matter volume could be an overestimation caused by motion bias rather than a true anatomical difference [19].

Q4: What is the utility of optical head tracking compared to image-based motion estimation?

Optical head tracking using depth cameras offers a direct, external method for measuring head motion with high accuracy and high frequency, capturing even rapid, burst movements [19]. In contrast, common image-based methods, like calculating realignment parameters from an fMRI time series, provide a low-frequency estimate that aggregates motion over the acquisition of a full volume (often 0.5 to several seconds). This makes them less sensitive to short, sharp movements. Furthermore, fMRI-based estimates are themselves affected by intra-frame motion artifacts and are inapplicable to single-volume structural scans, though they are sometimes used as a proxy for motion in adjacent acquisitions [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Mitigating Motion Artifacts in Functional Connectivity Analyses

Problem: Analysis of resting-state fMRI data from a cohort mixing patients and controls shows a pattern of stronger short-distance and weaker long-distance correlations in the patient group. You suspect motion may be causing a spurious, distance-dependent bias.

Solution: Implement a multi-step denoising pipeline that goes beyond simple realignment.

- Step 1: Quantify Motion Accurately. Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD) and DVARS for each subject. FD measures the volume-to-volume change in head position, while DVARS measures the rate of change of the BOLD signal across the entire brain at each timepoint [17] [20]. These metrics help characterize the extent of motion in your dataset.

- Step 2: Employ Rigorous Denoising Strategies. Use the motion parameters calculated in Step 1 to clean your data. Common strategies include:

- Regression: Include the 6 rigid-body realignment parameters (and optionally their derivatives and squares, making 24 regressors) as nuisance covariates in your model [20].

- * scrubbing:* Identify and censor volumes with excessive motion (e.g., FD > 0.2-0.5 mm) by adding additional regressors for those specific time points [20].

- Volume Interpolation: For motion outliers, replace the corrupted volume by interpolating from adjacent, non-corrupted volumes [20].

- Step 3: Control for Group-Level Motion Differences. Always test for and report whether your patient and control groups differ significantly in their mean FD or DVARS. If they do, include these motion metrics as covariates in your group-level statistical analyses to ensure that any observed effects are not driven by motion [17] [18].

Table 1: Common Motion Quantification Metrics

| Metric | Description | Typical Threshold | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Summarizes volume-to-volume changes in head position based on translation and rotation parameters [17]. | 0.2 - 0.5 mm | Identifying motion-contaminated volumes for scrubbing. |

| DVARS | Measures the root mean square change in BOLD signal across all voxels from one volume to the next [17] [20]. | 0.5% ΔBOLD | Detecting large, global signal shifts caused by motion or other artifacts. |

Guide 2: Addressing Pediatric-Specific Analysis Challenges

Problem: After processing structural MRI scans from a pediatric cohort using a standard adult-based pipeline, you notice poor normalization and segmentation, particularly in younger subjects.

Solution: Adapt your processing pipeline to be developmentally sensitive.

- Step 1: Use Pediatric Brain Templates. Instead of standard adult templates (e.g., MNI), warping participant brains to age-appropriate pediatric templates. These templates account for the smaller brain size and different structural proportions in children, leading to more accurate spatial normalization [18].

- Step 2: Account for Developmental Trajectories. Do not treat a pediatric cohort as a single, homogeneous group. The brain changes dramatically from childhood to adolescence. Your analysis should either:

- Step 3: Consider Psychotropic Medication Use. A significant proportion of children with NDDs may be taking psychotropic medications, which can alter brain structure and function. Document and, if possible, statistically account for medication use, as it is a potential confounding variable [18].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps for handling data from these challenging cohorts:

Experimental Protocols & Reagent Solutions

This section details a protocol for evaluating motion correction strategies in a task-based fMRI study, relevant to clinical populations like those with Multiple Sclerosis [20].

Protocol: Systematic Comparison of Motion Correction Models in Task-fMRI

- 1. Data Acquisition: Acquire task-fMRI data (e.g., a visual or motor paradigm) from participant groups (e.g., patients and healthy controls).

- 2. Motion Parameter Estimation: Realign all fMRI volumes to a reference volume (e.g., the first volume) to generate the 6 rigid-body motion parameters (translations X, Y, Z; rotations pitch, roll, yaw).

- 3. Create Expanded Parameter Sets: Derive the expanded sets of motion regressors:

- 12-Parameter Set: The 6 original parameters plus their temporal derivatives.

- 24-Parameter Set: The 12 parameters plus their squared values [20].

- 4. Detect Motion Outliers: Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD) for each volume. Flag volumes as motion outliers where FD exceeds a defined threshold (e.g., 0.5 mm).

- 5. Implement Correction Models: Analyze the data using multiple General Linear Models (GLMs) that incorporate different motion correction strategies:

- Model A: Nuisance regressors for the 6 motion parameters.

- Model B: Nuisance regressors for the 24 motion parameters.

- Model C: Model A plus scrubbing regressors for motion outliers.

- Model D: Model A with volume interpolation for motion outliers.

- 6. Evaluate Model Performance: Compare the resulting task-activation maps from each model. Assess performance based on metrics like the sensitivity and specificity for detecting expected task-related activation, and the reduction of motion-related artifacts.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Correction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Software Metric | Quantifies volume-to-volume head movement to identify scans with excessive motion [17] [20]. |

| DVARS | Software Metric | Measures the rate of global BOLD signal change to identify motion-corrupted timepoints [17] [20]. |

| Volume Interpolation | Software Algorithm | Replaces signal from motion-corrupted volumes with data interpolated from adjacent clean volumes, preserving the temporal structure of the data [20]. |

| High-Frequency Optical Tracking | Hardware/Software System | Provides an external, direct measure of head motion with high temporal resolution, independent of MRI image data [19]. |

| Pediatric Brain Templates | Digital Atlas | Age-specific brain templates for spatial normalization, crucial for accurate processing of pediatric neuroimaging data [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is motion correction particularly critical for large, multi-site neuroimaging studies?

In large, multi-site studies, data is aggregated from different research facilities using scanners from various vendors and with differing acquisition protocols. This introduces "batch effects"—variations in the data not due to the biological phenomenon under study but to the peculiarities of the acquisition equipment and parameters [22]. Head motion is a significant source of such batch effects. If not corrected, motion-induced artifacts can create systematic biases that confound true biological signals, reduce the statistical power of the study, and lead to unreliable or misleading results when developing automated tools like deep learning models for diagnosis [22].

FAQ 2: What are the main classes of motion correction strategies, and how do they differ?

Motion correction strategies can be broadly categorized into two classes:

- Prospective Motion Correction: This method adjusts the imaging plane in real-time to follow the subject's head movements during the scan. It often requires external hardware, like optical tracking systems, or dedicated navigator pulses [23] [24].

- Retrospective Motion Correction: This approach does not require special hardware. Instead, it estimates motion from the acquired data itself and corrects for it during the image reconstruction process. Techniques like PROPELLER (for 2D motion) and those using 3D radial sampling fall into this category [23] [24]. Retrospective methods are often more practical for large consortia as they do not depend on specific, and potentially expensive, hardware available at all sites.

FAQ 3: How can we quantitatively assess the success of motion correction in a dataset?

The success of motion correction can be evaluated using both qualitative (human-led) and quantitative (automated) measures:

- Qualitative Scoring: Expert radiologists or trained technicians can review images using a standardized Likert scale (e.g., 0-unusable to 4-excellent) to score image quality before and after correction [23].

- Quantitative Metrics: Automated, reference-free metrics like the Tenengrad metric provide a numerical measure of image sharpness, which is often reduced by motion-induced blurring [23]. Statistical analysis of vessel conspicuity, lumen area, and hemodynamic markers like blood flow rate can also reveal significant improvements post-correction [25].

FAQ 4: Our multi-site study uses different MRI scanners. How can we ensure motion correction strategies are effective across all platforms?

Ensuring effectiveness across platforms involves a combination of strategic sequence design and data harmonization:

- Use Robust Acquisition Sequences: Implement imaging sequences that are inherently more resilient to motion. 3D radial sampling is highly advantageous because motion artifacts manifest as diffuse blurring rather than distinct ghosts, and the oversampled k-space center can be used for self-navigation [23] [25].

- Apply Data Harmonization Methods: After data collection, use harmonization techniques to explicitly minimize the impact of site-specific batch effects. This can involve quality control protocols, statistical harmonization, or using deep learning models designed to be invariant to these technical variations [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Image Quality Due to Subject Motion

Problem: Reconstructed structural images (e.g., T1-weighted) show blurring or ghosts, making anatomical boundaries unclear.

| Step | Action & Rationale | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Motion Presence: Check for reported motion during the scan or use automated sharpness metrics (e.g., Tenengrad) on the raw images to confirm motion degradation [23]. | Establishes a baseline and confirms the root cause. |

| 2 | Apply Retrospective Correction: If a motion-resilient sequence (e.g., 3D radial) was used, employ a retrospective correction pipeline. This involves generating low-resolution 3D navigators from short-duration k-space data to estimate motion parameters via image registration, then applying these transforms to the k-space data before final reconstruction [23]. | Corrects for rigid-body motion after data acquisition without needing special hardware. |

| 3 | Optimize Navigator Parameters: If correction is suboptimal, adjust the resolution of the internal navigators. Very low resolution may miss subtle motion, while very high resolution may introduce aliasing. An optimal range (e.g., 5-7 mm) typically exists [23]. | Fine-tunes the motion estimation accuracy. |

| 4 | Re-score Image Quality: Have a blinded reviewer re-score the corrected image using a standardized scale and/or recalculate the sharpness metric to quantify improvement [23]. | Validates the effectiveness of the correction. |

Guide 2: Addressing Hemodynamic Bias in 4D-Flow MRI

Problem: Quantitative blood flow measurements in cerebral arteries are inconsistent or show unexpectedly high variability, potentially due to subject motion.

| Step | Action & Rationale | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Motion Bias: Compare quantitative flow rates, pulsatility indices, and lumen areas between subjects who moved and those who remained still. Look for significant differences that signal motion-induced bias [25]. | Diagnoses motion as a source of hemodynamic measurement error. |

| 2 | Implement Self-Navigated 4D-Flow: For new acquisitions, use a 3D radial trajectory with pseudorandom ordering. This allows the creation of high spatiotemporal resolution self-navigators from highly undersampled data for robust motion estimation [25]. | Acquires data that is well-suited for retrospective motion correction. |

| 3 | Apply Multi-Scale Motion Correction: Reconstruct the data using a multi-resolution low-rank regularization approach to support the motion correction process. Apply the derived rigid motion parameters to the 4D-Flow data [25]. | Corrects for motion throughout the acquisition, improving vessel sharpness and measurement accuracy. |

| 4 | Re-quantify Hemodynamics: Re-measure flow parameters after correction. Clinical exams have shown that motion correction can lead to statistically significant changes in these values, providing more reliable biomarkers [25]. | Yields more accurate and consistent quantitative results. |

Guide 3: Managing Batch Effects from Motion in Multi-Site DL Models

Problem: A deep learning model trained on aggregated multi-site data performs poorly on new data, likely because it learned site-specific motion artifacts instead of true biological features.

| Step | Action & Rationale | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Detect the Batch Effect: Use a simple classifier (e.g., a CNN) to try and predict the scanner site or protocol from the images. High accuracy indicates strong, problematic batch effects that the model can exploit [22]. | Proves the presence of confounding technical variation. |

| 2 | Apply Data Harmonization: Use explicit methods to standardize the data across sites. This can include strict quality control to exclude severely motion-corrupted images or using algorithms like ComBat to remove site-specific technical effects [22]. | Explicitly minimizes unwanted technical variability before model training. |

| 3 | Utilize Domain Adaptation: Develop DL models that are inherently robust to domain shifts. Train the model on the multi-site data, using techniques that force it to learn features that are invariant to the source site, thereby ignoring site-specific artifacts [22]. | Creates a model that implicitly handles variability, improving generalizability. |

| 4 | Validate on External Data: Benchmark the harmonized or domain-adapted model on a completely independent dataset acquired with different protocols to ensure its robustness and clinical utility [22]. | Tests the true generalizability of the developed tool. |

Quantitative Data on Motion Correction Efficacy

Table 1: Impact of Retrospective Motion Correction on Structural Image Quality

Data derived from a study of 44 pediatric participants scanned with a motion-corrected MPnRAGE sequence [23].

| Metric | Non-Corrected Images | Motion-Corrected Images | Change & (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Likert Score (0-4 scale) | 3.0 | 3.8 | +0.8 |

| Standard Deviation (Likert) | 1.1 | 0.4 | -0.7 |

| Quality Improvement | -- | -- | Significant (P < 0.001) |

| Worst-case Improvement | Unusable (Score 0) | Good (Score 3) | +3 points |

Table 2: Effect of Motion Correction on Neurovascular 4D-Flow Hemodynamics

Data from clinical-research exams showing significant changes in quantitative flow metrics after motion correction [25].

| Cerebral Artery | Blood Flow (P-value) | Lumen Area (P-value) | Flow Pulsatility Index (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left Internal Carotid (Lt ICA) | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | -- |

| Right Internal Carotid (Rt ICA) | P = 0.002 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.042 |

| Left Middle Cerebral (Lt MCA) | P = 0.004 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.002 |

| Right Middle Cerebral (Rt MCA) | P = 0.004 | P = 0.004 | -- |

Experimental Protocols for Motion-Corrected Imaging

Protocol 1: MPnRAGE with Integrated Motion Correction for Structural Imaging

This protocol is designed for acquiring high-resolution T1-weighted volumetric images in challenging populations (e.g., un-sedated pediatric participants) where motion is likely [23].

- Pulse Sequence: 3D radial sampling combined with an inversion-recovery magnetization preparation (MPnRAGE).

- Key Parameters:

- k-space View Ordering: Double bit-reversed scheduling to ensure pseudorandom sampling for both navigator formation and multi-contrast reconstruction.

- Navigator Formation: Subsets of consecutive radial views acquired between magnetization-preparation pulses (~400 views every 2 seconds) are used to form low-resolution 3D navigator images.

- Navigator Resolution: Reconstruct navigators at an isotropic resolution of 6 mm (optimized range 5-7 mm) by apodizing radial views with a Fermi filter.

- Motion Estimation: Use image coregistration tools (e.g., from the FSL library) on the navigator images to estimate 3D translational and rotational motion parameters.

- Final Reconstruction: Apply the estimated motion parameters to correct the k-space data before performing the full-resolution reconstruction.

Protocol 2: Self-Navigated 3D Radial 4D-Flow MRI for Hemodynamic Studies

This protocol enables retrospective rigid motion correction for neurovascular 4D-Flow MRI, crucial for accurate hemodynamic measurement in aging or other moving populations [25].

- Pulse Sequence: 4D-Flow MRI acquired using a 3D radial trajectory with pseudorandom view ordering.

- Key Components:

- Self-Navigation: The oversampled central k-space region of the 3D radial data is used to generate high spatiotemporal resolution navigators.

- Reconstruction Framework: A multi-scale low-rank reconstruction support is used to enable motion estimation from the extremely undersampled navigator data.

- Motion Correction: The rigid motion parameters derived from the self-navigators are applied retrospectively during the image reconstruction process.

- Outcome: This integrated approach reduces image blurring, increases vessel conspicuity, and decreases variability in quantitative hemodynamic markers.

Workflow Diagrams

Motion Correction in Multi-Site Studies

Retrospective Motion Correction Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| 3D Radial Sequence | An MRI acquisition technique where k-space is sampled along spokes radiating from the center. It is inherently motion-resilient, as motion artifacts manifest as benign blurring rather than ghosts, and the oversampled center enables self-navigation for motion estimation [23] [25]. |

| Self-Navigation Framework | A software and algorithmic framework that uses intrinsically acquired data (e.g., the central k-space of radial scans) to track and estimate subject motion during an MRI scan, eliminating the need for external tracking hardware [23] [25]. |

| Tenengrad Sharpness Metric | A reference-free, quantitative image quality metric that measures the sharpness of an image by computing the squared magnitude of the gradient. It is highly correlated with human perception of motion-induced blurring and is used for automated quality control [23]. |

| Data Harmonization Tools (e.g., ComBat) | Statistical or algorithmic tools designed to remove site-specific "batch effects" from aggregated multi-site datasets. This ensures that variability in the data is due to biological rather than technical differences, which is critical for training generalizable models [22]. |

| Domain Adaptation DL Models | A class of deep learning models (e.g., Domain Adversarial Neural Networks) specifically designed to learn features that are invariant across different data domains (e.g., different scanner sites). This makes the models robust to unseen data from new sites [22]. |

Motion Correction Arsenal: From Prospective Tracking to AI-Driven Solutions

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) is a sophisticated technique in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that addresses the persistent challenge of subject motion during scanning. Unlike retrospective methods that apply corrections after data acquisition, PMC operates in real-time by dynamically adjusting the imaging sequence to track and compensate for head movements as they occur. This approach is particularly crucial for high-resolution neuroimaging and functional MRI (fMRI) studies where even minor movements can significantly degrade data quality. PMC systems primarily utilize two technological approaches: external optical tracking devices that monitor head position using cameras and markers, and MR-based navigators (MR-Nav) that employ embedded sequence modifications to track motion directly from the acquired signal. Both methods enable continuous updating of scan planes by modifying gradient orientations and radiofrequency pulses, effectively "locking" the imaging volume to the moving anatomy. This technical framework is especially valuable for large-scale neuroimaging studies and drug development research where data consistency across subjects and sessions is paramount for reliable statistical analysis and outcome measurements [26] [27] [28].

Technical Foundations

Optical Tracking Systems

Optical tracking systems for PMC utilize camera-based monitoring of specialized markers attached to the subject's head to provide real-time motion data. These systems typically employ either single or multiple cameras positioned within the scanner bore or mounted directly on the head coil. The fundamental principle involves continuous tracking of reflective or active markers secured to the subject via various attachment methods, with mouthpieces generally providing superior rigidity compared to skin attachments. Advanced implementations may utilize two markers placed on the forehead to enhance system robustness through "adaptive tracking" - if one marker becomes obscured, the system can infer its position from the visible marker using known relative transforms. This configuration also enables "squint detection" by monitoring relative positional changes between markers that indicate non-rigid facial movements, allowing the system to pause data acquisition during these events to prevent artifact introduction [29] [27] [30].

A critical requirement for optical tracking systems is cross-calibration - the process of determining the precise spatial transformation between the camera's coordinate system and the MRI scanner's inherent coordinate system defined by its gradients. This calibration must be extremely accurate (substantially below 1 mm and 1°) to ensure effective motion correction, as errors propagate through to residual tracking inaccuracies. Recent methodological advances have streamlined this process using custom calibration tools with wireless active markers, reducing calibration time from approximately 30 minutes to under 30 seconds per installation while maintaining sufficient accuracy for clinical applications. This improvement addresses a significant barrier to clinical deployment of optical PMC systems [29] [31].

MR-Based Navigators

MR-based navigators (MR-Nav) represent an alternative approach that embeds brief, additional acquisitions within the primary imaging sequence to directly monitor subject position. These specialized acquisitions sample limited k-space data that can be rapidly reconstructed and analyzed for motion detection. The PROMO (PROspective MOtion correction) system exemplifies this approach, utilizing three orthogonal 2D spiral navigator acquisitions (SP-Navs) combined with an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) algorithm for online motion measurement. This framework offers image-domain tracking within patient-specific regions-of-interest with reduced sensitivity to off-resonance-induced corruption of rigid-body motion estimates [32].

Spiral navigators provide efficient k-space coverage with parameters typically including: TE/TR = 3.4/14 ms, flip angle = 8° (to minimize impact on the acquired 3D volume), bandwidth = ±125 kHz, field-of-view = 32 cm, effective in-plane resolution = 10 × 10 mm, reconstruction matrix = 128 × 128, and slice thickness = 10 mm. The spiral readouts are particularly advantageous due to their efficient k-space coverage and reduced sensitivity to distortion, though they remain vulnerable to severe off-resonance effects (> ±100 Hz) which can be mitigated through center frequency correction before scanning. These navigators can be strategically inserted during intrinsic sequence dead time, such as the longitudinal recovery time in 3D inversion recovery spoiled gradient echo (IR-SPGR) and 3D fast spin echo (FSE) sequences, minimizing impact on total scan duration [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Optical and Navigator-Based PMC Approaches

| Feature | Optical Tracking | MR-Based Navigators |

|---|---|---|

| Tracking Principle | External camera monitors head-mounted markers | Embedded sequence modifications acquire limited k-space data |

| Hardware Requirements | MR-compatible camera system, markers, attachment method | No additional hardware required |

| Typical Accuracy | <0.1 mm position, <0.1° orientation [30] | <10% of motion magnitude, even for rotations >15° [32] |

| Key Advantages | Independent of MRI sequence, preserves magnetization steady state | No line-of-sight requirements, internal coordinate system |

| Primary Limitations | Line-of-sight requirements, marker attachment challenges | Sequence modification required, potential TR prolongation |

| Calibration Requirements | Cross-calibration between camera and scanner coordinates (<1 mm/1° accuracy) | No cross-calibration needed |

| Representative Systems | Moiré Phase Tracking (MPT), in-bore camera systems | PROMO with spiral navigators, cloverleaf navigators |

Experimental Protocols

Optical Tracking Implementation Protocol

Implementing optical PMC requires careful attention to system setup, calibration, and validation. The following protocol outlines the key steps for reliable operation:

System Setup and Cross-Calibration: Mount the camera securely on the head coil to maintain an unobstructed view of the marker throughout expected motion ranges. For systems requiring cross-calibration, use a calibration tool with integrated wireless active markers and optical tracking features. Perform the calibration scan by moving the tool through 10-20 poses including rotations about all three axes (maximum approximately 15°) while simultaneously tracking via both camera and active markers. This process typically requires approximately 30 seconds and needs repetition only if the camera position changes relative to the scanner. Implement a calibration adjustment method to automatically compensate for table motion between scans [29].

Marker Attachment and Validation: Attach the marker using a rigid attachment method. While skin adhesives are generally insufficient, custom-molded mouthpieces provide excellent rigidity. For forehead placement, consider using two markers to enable redundancy and squint detection. Validate marker rigidity by having the subject perform facial movements (e.g., squinting, talking) while monitoring relative marker positions. If significant motion (>0.5 mm or >0.5°) is detected between markers, reposition or reinforce the attachment [27] [30].

Sequence Integration: Integrate tracking data into the pulse sequence using libraries such as XPACE, applying motion compensation before each radiofrequency pulse to maintain consistent anatomical alignment. For multi-marker systems, implement logic to automatically switch tracking source if the primary marker becomes obscured, using the known relative transform between markers calculated during periods of simultaneous visibility [30].

MR-Navigator Implementation Protocol

Implementing MR-based navigators requires pulse sequence modification and optimization of navigator parameters:

PROMO with Spiral Navigators: Integrate three orthogonal 2D spiral navigator acquisitions (SP-Navs) into the pulse sequence, positioned during intrinsic dead time such as the T1 recovery periods in 3D sequences. For 3D IR-SPGR and 3D FSE sequences, acquire multiple SP-Navs during the recovery time (e.g., 5 SP-Navs over ~500 ms during a 700-1200 ms recovery period). Each SP-Nav requires approximately 42 ms for acquisition plus 6 ms for reconstruction of all three planes. Program the repetition time for each SP-Nav to 100 ms to allow ample time for estimation and feedback [32].

Motion Tracking and Correction: Implement the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) algorithm for real-time motion estimation using the dynamic state-space model. The EKF provides recursive state estimates in nonlinear dynamic systems perturbed by Gaussian noise, with the system equation: xk = Axk-1 + w; P(w)~N(0,Q) and measurement equation: yk = h(xk) + v; P(v)~N(0,R). Apply motion compensation by updating the imaging volume position and orientation based on the EKF estimates [32].

Performance Validation: Validate tracking performance using staged motions and compare with known motion parameters. The steady-state error of SP-Nav/EKF motion estimates should be less than 10% of the motion magnitude, even for large compound motions including rotations over 15°. For functional studies, verify improvement in temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) and reduction of spin history effects [32] [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Optical Tracking Issues

Problem: Poor Image Quality Despite PMC Activation

- Possible Cause 1: Inaccurate cross-calibration between camera and scanner

- Solution: Reperform cross-calibration using the rapid calibration method with the dedicated calibration tool. Ensure the tool moves through sufficient poses (10-20) with rotations about all three axes during calibration [29] [31].

- Possible Cause 2: Marker attachment flexibility

- Solution: Verify marker rigidity by monitoring relative position during facial movements. Switch to a custom-molded mouthpiece if skin attachments show excessive movement (>0.5 mm between markers) [27] [30].

- Possible Cause 3: Calibration drift due to table movement

- Solution: Implement automated calibration adjustment to compensate for table position changes between scans [29].

Problem: Intermittent Tracking Loss

- Possible Cause 1: Obstructed line-of-sight between camera and marker

- Solution: Reposition camera to maximize field of view within coil constraints. Implement two-marker tracking with automatic switching to maintain tracking when one marker is obscured [30].

- Possible Cause 2: Marker moving outside camera field of view

- Solution: Adjust camera angle or use wide-angle lens. For large motions, consider additional cameras or marker placement optimization [29].

Problem: Introduction of Artifacts During PMC

- Possible Cause 1: Non-rigid facial motions (squinting, talking)

- Solution: Implement two-marker system with squint detection. Pause data acquisition when non-rigid motion is detected (relative marker movement >0.5 mm or >0.5°) and resume once rigid-body conditions return [30].

- Possible Cause 2: Latency in tracking data processing

- Solution: Optimize tracking data pipeline. Ensure camera operates at sufficient frame rate (≥60 Hz) and minimize processing delays between motion detection and sequence update [29].

Common MR-Navigator Issues

Problem: Increased Scan Time with Navigators

- Possible Cause: Navigator acquisition extending repetition time

- Solution: Optimize navigator placement within sequence dead time. For 3D sequences, insert multiple navigators during T1 recovery periods rather than between excitations [32].

Problem: Poor Tracking Accuracy

- Possible Cause 1: Severe off-resonance effects

- Solution: Perform center frequency correction before scanning. For areas with pronounced field inhomogeneities, consider alternative navigator trajectories less sensitive to off-resonance [32].

- Possible Cause 2: Insufficient navigator resolution or coverage

- Solution: Optimize navigator parameters balancing accuracy and acquisition time. Spiral navigators with 10×10mm in-plane resolution and 10mm thickness typically provide sufficient accuracy [32].

Problem: Navigator Interference with Image Contrast

- Possible Cause: Saturation effects from navigator RF pulses

- Solution: Use low flip-angle navigators (e.g., 8°) to minimize impact on longitudinal magnetization [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key benefits of prospective versus retrospective motion correction?

Prospective motion correction addresses motion at its source by keeping the measurement coordinate system fixed relative to the patient throughout scanning, preventing data inconsistencies before they occur. This avoids several limitations of retrospective correction, including inability to fully correct for through-plane motion in 2D sequences, k-space data inconsistencies from interpolation errors, and spin history effects. PMC particularly benefits high-resolution acquisitions where even sub-millimeter motions can significantly degrade image quality [32] [26].

Q2: How does motion affect fMRI data quality specifically?

In fMRI, motion introduces temporal signal variations that confound the detection of BOLD activity through multiple mechanisms: (1) spin history effects from movement relative to RF excitation pulses; (2) intensity modulation from changing position relative to receiver coil sensitivity profiles; (3) partial-volume effect modulation from anatomical structures moving relative to voxel grids; and (4) B0 field modulation from head motion relative to static magnetic field inhomogeneities. These effects can increase false positives and reduce statistical significance of activation maps, particularly problematic in patient populations with limited compliance [26] [28].

Q3: What level of tracking accuracy is required for effective PMC?

The required accuracy depends on the application and expected motion range. For most neuroimaging applications, cross-calibration accuracy should be substantially below 1 mm and 1°. Optical tracking systems typically achieve <0.1 mm positional and <0.1° orientation accuracy. MR-navigator systems like PROMO maintain steady-state errors of less than 10% of motion magnitude, even for large rotations exceeding 15°. The general principle is that scans with smaller expected movements require less calibration accuracy than those involving larger movements [31] [30].

Q4: What attachment method is most reliable for optical markers?

Mouthpieces generally provide superior rigidity compared to skin attachments. While custom dentist-molded mouthpieces offer optimal performance, recent research shows that inexpensive, commercially available mouthpieces molded on-site can provide comparable results without the time and expense of dental visits. Skin attachments, particularly on the forehead, are susceptible to non-rigid motion from facial movements and typically show greater displacement relative to the skull [27] [30].

Q5: Can PMC improve data quality even in cooperative subjects instructed to remain still?

Yes, studies demonstrate that PMC provides benefits even in the absence of deliberate motion. In fMRI, PMC significantly increases temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) and improves the quality of resting-state networks and connectivity matrices, particularly at higher resolutions. The benefit is most apparent for multi-voxel pattern decoding where accurate voxel registration across time is essential [27] [28].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Prospective Motion Correction

| Component | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Tracking Camera | Tracks marker position and orientation | MR-compatible camera, 640×480 resolution, 60 Hz frame rate, monochrome [29] |

| Tracking Markers | Provides visual reference for tracking | Checkerboard optical marker (15×15mm), reflective or active markers, with unique identification barcodes [30] |

| Marker Attachment | Secures marker rigidly to subject | Custom-molded mouthpieces, skin-adhesive markers, dental impression material for on-site molding [27] |

| Calibration Tool | Enables camera-to-scanner cross-calibration | Sphere with integrated wireless active markers and optical marker, rigid construction [29] |

| Wireless Active Markers | Provides scanner-trackable reference for calibration | Small RF coils with water samples, detectable via specialized tracking sequences [29] |

| Spiral Navigators | MR-based motion tracking | 2D spiral acquisitions, TE/TR=3.4/14ms, 8° flip angle, 10mm thickness, 10×10mm in-plane resolution [32] |

| Software Libraries | Integration of tracking data into sequences | XPACE library for communication between tracker and sequence, Extended Kalman Filter implementation [32] [30] |

Workflow Diagrams

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core principle behind retrospective motion correction? Retrospective motion correction methods work by estimating motion from the acquired data itself, without the need for external tracking hardware. This is typically achieved through image-based registration techniques, where a series of low-resolution "navigator" images are reconstructed from subsets of the acquired data. These navigators are then coregistered to a reference volume to estimate rigid transformation parameters (rotations and translations), which are subsequently applied to the data during the final reconstruction process to create a motion-corrected image [23] [33].

FAQ 2: How does data-driven motion correction in PET differ from methods used in MRI? While both rely on estimating and correcting motion from the data, PET-specific methods often use list-mode data. An ultra-fast list-mode reconstruction framework partitions the data into very short time frames, reconstructs them to create a motion time series via image registration, and then performs a final event-by-event motion-corrected reconstruction. This approach can correct for both fast and slow intra-frame motion, which is crucial for long PET acquisitions [33].

FAQ 3: My motion-corrected images still show blurring or artifacts. What could be the cause? Several factors can lead to suboptimal correction:

- Insufficient Navigator Resolution: If the navigator images used for motion estimation are reconstructed at a suboptimal resolution, motion estimates can be inaccurate. One study found an optimal navigator resolution range of 5–7 mm for 3D radial MRI data [23].

- Irreversible Data Corruption: Some data points may be so severely corrupted by artifacts that they are irrecoverable. Techniques like "reliability masking," which exclude such unreliable data points from final analysis, can supplement motion correction [34].

- Residual Effects: Retrospective correction is limited because intra-slice and intra-voxel information is affected by motion, and computational methods can leave residual artifacts of their own [35].

FAQ 4: Can retrospective correction fully replace the need for sedation in pediatric imaging? Evidence suggests that robust motion correction can significantly reduce reliance on sedation. A prospective pediatric brain FDG-PET study demonstrated that motion-corrected images from scans with scripted motion were qualitatively and quantitatively indistinguishable from, or better than, images obtained without motion. This indicates that motion correction software can produce diagnostic-quality images from corrupted data, moving towards reduced sedation use [36].

FAQ 5: What are the key subject factors that predict higher levels of head motion during scanning? Knowledge of these factors helps in anticipating motion and planning studies. Analysis of a large cohort (n=40,969) from the UK Biobank revealed the following key indicators [35]:

Table 1: Key Indicators of fMRI Head Motion

| Indicator | Association with Head Motion | Effect Size (Adjusted β) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Strongest positive association; a 10-point increase (e.g., "healthy" to "obese") linked to a 51% motion increase [35] | βadj = .050 [35] |

| Ethnicity | Significant association [35] | βadj = 0.068 [35] |

| Cognitive Task Performance | Associated with increased motion compared to rest [35] | t = 110.83 [35] |

| Prior Scan Experience | Associated with increased motion in follow-up scans [35] | t = 7.16 [35] |

| Disease Status (e.g., Hypertension) | Can be a significant indicator, but disease diagnosis alone is not a reliable predictor [35] | p = 0.048 [35] |

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Poor Registration Performance in Image-Based Motion Estimation

- Potential Cause: Inadequate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the navigator images used for registration.

- Solution: Optimize the number of data views or the duration of each sub-scan used to reconstruct the navigators. Ensure the navigator resolution is appropriate; for a 3D radial MPnRAGE acquisition, a resolution of 6 mm was found to be optimal [23].

- Protocol: To determine the ideal navigator parameters, perform a pilot analysis using a reference-free sharpness metric (e.g., Tenengrad) on motion-corrected images reconstructed from navigators of varying resolutions [23].

Issue 2: High Variability in Quantitative Outcomes After Motion Correction

- Potential Cause: Motion-induced blurring increases the variability of quantitative measurements across subjects, reducing the statistical power of between-group differences.

- Solution: Implement a reliability masking step in your post-processing pipeline. This novel outlier rejection technique excludes irreversibly corrupted data points from the final analysis.

- Evidence: In a spinal cord DTI study, adding reliability masking to a processing chain (which already included registration and robust fitting) increased the statistical power of a between-group difference finding by 4.7%, primarily by reducing group-level variability [34].

Issue 3: Challenges in Handling Large-Scale, Multi-Site Neuroimaging Data

- Potential Cause: Traditional software may struggle with computational speed, memory allocation, and missing voxel-data common in aggregated datasets.

- Solution: Utilize a unified software framework like Image-Based Meta- & Mega-Analysis (IBMMA). This tool is designed for large-scale data, handles missing voxel-data robustly, uses parallel processing for efficiency, offers flexible statistical modeling, and can be implemented in R and Python [37].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Motion Correction Performance in Phantom Studies

This protocol is used to validate a list-mode-based motion correction method for PET imaging [33].

- Phantom Setup: Use a Hoffman phantom or a Mini Hot Spot phantom filled with 18F solution.

- Acquisition:

- Perform a static, motion-free acquisition as a ground truth.

- Perform a second acquisition while introducing continuous, complex rotation and translation using a motorized system (e.g., QUASAR).

- Motion Tracking: Simultaneously track phantom motion with a high-accuracy optical tracking system (e.g., Polaris Vega Camera) to obtain ground-truth transformation parameters.

- Data Processing: Apply the retrospective motion correction method to the moving phantom data.

- Validation: Compare the motion parameters estimated by the software with the optical tracking ground truth. Visually and quantitatively compare the motion-corrected image against the motion-free ground truth and the uncorrected moving image.

Protocol 2: Assessing Impact on Clinical Quantitative Measures

This protocol evaluates the effect of motion correction on the longitudinal measurement of tau accumulation in Alzheimer's disease research [33].

- Subject Population: Recruit subjects for longitudinal PET studies (e.g., baseline and follow-up scans months apart) using a tracer like [18F]-MK6240.

- Data Acquisition & Reconstruction: Acquire list-mode PET data. Reconstruct each scan twice: with motion correction (MC) and without (NoMC).

- Quantitative Analysis: For each reconstruction, calculate the standard uptake value (SUV) in key brain regions of interest (e.g., entorhinal cortex, inferior temporal, precuneus).

- Longitudinal Calculation: For each subject and reconstruction type, compute the rate of tau accumulation as the difference in SUV between time points.

- Statistical Comparison: Calculate the standard deviation of the accumulation rate across subjects for both MC and NoMC images. A reduction in standard deviation with MC indicates improved measurement consistency.

Table 2: Impact of Motion Correction on Tau PET Quantitation (Sample Results)

| Brain Region | Reduction in Standard Deviation of Tau Accumulation Rate with Motion Correction |

|---|---|

| Entorhinal Cortex | -49% [33] |

| Inferior Temporal | -24% [33] |

| Precuneus | -18% [33] |

| Amygdala | -16% [33] |

Workflow Visualization

Generic Retrospective Motion Correction Workflow

List-Mode PET Motion Correction Workflow [33]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Retrospective Motion Correction Research

| Tool / Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FSL (FMRIB Software Library) | A comprehensive library of MRI and fMRI analysis tools. Includes MCFLIRT for motion estimation and FLIRT for image registration [38] [23] [35]. | Coregistering navigator images for motion parameter estimation [23]. |

| List-Mode Reconstruction Framework | Enables event-by-event motion correction by using ultra-fast reconstructions of short data frames for motion tracking [33]. | Correcting for both fast and slow head motion in long-duration PET studies [33] [36]. |

| 3D Radial Sampling | An MRI acquisition sequence where k-space is sampled along radiating spokes. More motion-robust than Cartesian sampling, causing blurring instead of ghosting [23]. | Used in MPnRAGE acquisitions to enable effective 3D motion estimation and correction [23]. |

| BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure) | A standard for organizing and describing neuroimaging data. | Simplifying data management and ensuring interoperability between different processing tools in large-scale studies [39]. |

| Containerized Pipelines (e.g., Docker/Apptainer) | Package processing software and its dependencies into a portable, reproducible environment [39]. | Ensuring consistent processing results across different computing systems and over time [39]. |

| IBMMA (Image-Based Meta- & Mega-Analysis) | A unified R/Python software package for analyzing large-scale, multi-site neuroimaging data [37]. | Handling missing voxel-data and complex statistical designs in aggregated datasets from multiple studies [37]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Data Quality and Preprocessing

My multi-modal dataset has fMRI data with different repetition times (TRs). Can I still use a unified framework?

Yes, this is a common challenge. Modern frameworks like BrainHarmonix are specifically designed to handle heterogeneous TRs. Their key innovation is a Temporal Adaptive Patch Embedding (TAPE) layer, which generates token representations with consistent temporal length regardless of the input TR. As a solution, you can also implement data augmentation by artificially downsampling high-resolution time series to create a hierarchy of TR levels, which improves model robustness [40].

How do I check if my motion correction was successful?

First, use visualization tools to inspect your data. Most software, like BrainVoyager, generates a motion correction movie that toggles between the first and last volume of a functional run before and after correction, allowing you to visually assess improvement [41]. You can also use the "Time Course Movie" tool to screen the functional time series for sudden intensity changes or residual movement across volumes [41]. Quantitatively, plot the estimated motion parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) over time to identify any sudden motion spikes that might require additional processing [41].

A large portion of my volumes exceed the framewise displacement (FD) threshold. Should I censor them or use regression?

This is a critical decision that depends on your analysis goals and the extent of data loss.

- Censoring (Scrubbing): For task-based fMRI, one effective method is to "censor" high-motion time points by zeroing-out their entries in the design matrix and adding a single nuisance regressor for each censored time point (a stick regressor). This is recommended for significant motion artifacts that regression alone cannot fix [42].

- Regression: Including the motion parameters (e.g., 24-parameter model from Friston et al., 1996) as confounds in your General Linear Model (GLM) is a standard practice to mitigate motion-related variance [42].

- Best Practice: For the most rigorous approach, use both methods together. Motion correction (realignment) is the baseline. This should be followed by motion parameter regression in the GLM, and finally, censoring of volumes with extreme motion (e.g., FD > 0.5 mm) to prevent them from unduly influencing your results [42].

FAQ: Model Architecture and Integration

How can I architect a model to truly "unify" structure (sMRI) and function (fMRI) rather than just process them separately?

True unification requires an architecture that imposes neuroscientifically-grounded constraints. The Brain Harmony framework achieves this through a two-stage process:

- Unimodal Encoding: Train separate encoders for structure (e.g., a 3D Masked Autoencoder for T1 images) and function.

- Multimodal Fusion: Fuse the modality-specific representations using a set of shared, learnable "brain hub tokens." These tokens act as a representational bottleneck, explicitly trained to reconstruct both structural and functional latents, thereby creating a unified latent space. Crucially, the functional encoder incorporates a geometric pre-alignment step, using geometric harmonics derived from population-level cortical geometry to align functional dynamics with the underlying brain structure [40].

What fusion technique should I use for combining imaging and clinical data?

The choice of fusion technique depends on your model architecture and the nature of the data [43].

- Early Fusion: Combining raw or low-level features from different modalities before feeding them into the model. This can be powerful but is often challenging due to feature misalignment.

- Intermediate/Joint Fusion: Using architectures like Transformers or Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to learn interactions between modalities within the model. Transformers use self-attention to weight the importance of different features [43], while GNNs can explicitly model clinical and imaging data as nodes in a non-Euclidean graph, preserving their natural relationships [43].

- Late Fusion: Training separate models for each modality and combining their final predictions. This is simpler but may fail to capture complex cross-modal interactions.

For cutting-edge applications, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are particularly promising for representing non-Euclidean relationships between heterogeneous data types, such as linking an imaging feature to a clinical parameter [43].

I encounter the error "Get rid of patches that are too close to edges" during motion correction. What does this mean?