Advances in Non-Sedated Pediatric MRI: A Research-Focused Review on Motion Artifact Reduction for Enhanced Neuroimaging and Drug Development

This article synthesizes current evidence and methodologies for obtaining high-quality, motion-free pediatric MRI without sedation, a critical objective for minimizing anesthetic neurotoxicity risks and streamlining clinical trial imaging.

Advances in Non-Sedated Pediatric MRI: A Research-Focused Review on Motion Artifact Reduction for Enhanced Neuroimaging and Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current evidence and methodologies for obtaining high-quality, motion-free pediatric MRI without sedation, a critical objective for minimizing anesthetic neurotoxicity risks and streamlining clinical trial imaging. We explore the foundational rationale, including risks of sedation and parental preferences, and detail a multi-faceted framework of non-pharmacological interventions. This framework encompasses patient preparation strategies, technological advancements in audiovisual distraction, rapid imaging protocols, and motion-correction algorithms. We further evaluate the efficacy and clinical validation of these approaches through recent trial data and discuss optimization strategies for troubleshooting common challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive evidence base to support the implementation of robust, sedation-free imaging protocols in pediatric populations, thereby improving safety and data quality in clinical research.

The Imperative for Sedation-Free Pediatric MRI: Risks, Rationale, and Clinical Demand

FAQs: Sedation Neurotoxicity and Risk Mitigation in Pediatric Research

Q1: What is the primary evidence for anesthesia-related neurotoxicity in the developing brain? Preclinical studies demonstrate that exposure to sedatives and anesthetics during critical periods of brain development can cause widespread apoptotic neurodegeneration and permanent neurocognitive impairment. The mechanism is linked to the modulation of NMDA and GABAA receptors, similar to the established neurotoxidrome of fetal alcohol syndrome. In rodent and non-human primate models, exposure to agents like midazolam, nitrous oxide, isoflurane, and ketamine has been associated with neuroapoptosis and persistent deficits in memory, learning, and task performance [1]. The window of vulnerability is during peak synaptogenesis, and effects appear to be dose-dependent, with amplified toxicity from multiple exposures [1].

Q2: How do findings from human studies compare to animal models? Human retrospective studies show an association between early childhood anesthesia exposure and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, but the strength of this association is weak (hazard ratios typically less than 2) and inconsistent [1]. Crucially, recent high-quality prospective studies suggest that single, brief exposures (under one hour) do not produce measurable neurodevelopmental deficits. The General Anesthesia Compared to Spinal Anesthesia (GAS) trial found no evidence of adverse neurodevelopment at 2 years of age in neonates receiving brief sevoflorane anesthesia [1]. Similarly, the Pediatric Anesthesia NeuroDevelopment Assessment (PANDA) study found no difference in IQ scores among healthy children exposed to a single anesthetic before 36 months of age compared to their unexposed siblings [1]. However, higher cumulative doses of specific agents like ketamine have been associated with poorer motor performance at 18 months in vulnerable populations, such as infants with congenital heart disease [2].

Q3: What is the clinical significance of the FDA warning on anesthetic and sedative drugs? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has mandated a warning label indicating that repeated or lengthy (>3 hours) use of general anesthetic and sedation drugs during surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years or in pregnant women during the third trimester may affect the child's developing brain [1]. This warning is based largely on robust animal data. The clinical consensus, endorsed by organizations like SmartTots, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia, is that concerns about the unknown risk of anesthetic exposure must be weighed against the potential harm of canceling or delaying a needed procedure [1].

Q4: What are the primary strategies for reducing sedation in pediatric MRI? Strategies can be categorized as follows:

- Behavioral and Non-Pharmacological: Parental presence, feed-and-swaddle techniques for infants, mock MRI scanners, child life specialist-led preparation, video goggles, and scheduling scans during evening hours to leverage natural sleep cycles [3] [4] [5].

- Technical and Protocol-Based: Using accelerated imaging techniques like parallel imaging, compressed sensing, and simultaneous multislice acquisition to shorten scan times. Employing motion-robust sequences like radial sampling to minimize motion artifacts without sedation [6] [7].

- Protocol Abbreviation: Focusing imaging protocols on essential "reporting elements" for a specific clinical indication to avoid unnecessary sequences and reduce the time a child must remain still [7].

Table 1: Key Findings from Human Studies on Anesthesia/Sedation Exposure and Neurodevelopment

| Study (Design) | Population | Exposure | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAS Trial [1] (Randomized Controlled Trial) | Neonates undergoing hernia repair | General anesthesia (sevoflorane) <1 hour vs. spinal anesthesia | No evidence of adverse neurodevelopment at 2 years of age. |

| PANDA Study [1] (Sibling-Matched Cohort) | Healthy children with inguinal hernia repair | Single anesthetic exposure before 36 months | No difference in IQ scores in later childhood compared to unexposed siblings. |

| Wilder et al. [1] (Retrospective Birth Cohort) | Children <4 years | Varied; single vs. multiple exposures | Two-fold increase in risk of learning disabilities among multiply exposed children. |

| Congenital Heart Disease Cohort [2] (Prospective Observational) | Infants with congenital heart disease | Cumulative inpatient sedative/anesthetic exposure | Each mg/kg increase in ketamine exposure was associated with a 0.34 point decrease in Bayley-III Motor scores at 18 months. No association found for volatile anesthetics, opioids, or benzodiazepines. |

Table 2: Efficacy of Non-Sedation Strategies for Pediatric MRI

| Intervention | Study Design | Population | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Presence [3] | Randomized Controlled Trial | Children 3-10 years | Significantly improved MRI success without sedation in children aged 3-6 years (OR=6.50). No significant benefit in children 7-10 years. |

| Movie Watching & Real-time Feedback [8] | Behavioral Intervention | Children 5-15 years | Head motion was significantly reduced during movie watching and when receiving real-time feedback, with effects driven by children aged 5-10 years. |

| Accelerated/Abbreviated Protocols [7] | Technical Review | Pediatric patients | Using accelerated imaging and protocol abbreviation based on clinical indication can reduce or eliminate the need for sedation. |

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Parental Presence for Non-Sedated MRI This protocol is based on a prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trial [3].

- Participant Recruitment: Children aged 3–10 years referred for pituitary MRI due to suspected growth hormone deficiency. Exclusions include diagnosed intellectual disability or neurodevelopmental disorder.

- Randomization: Participants are stratified by age (3–6 and 7–10 years) and randomly assigned to "parent present" or "parent absent" groups using block randomization.

- Preparation: All children receive standardized MRI preparation from a child life specialist or pediatrician, including verbal reassurance, printed materials, and a soft toy with a wooden mock MRI scanner.

- Intervention: For the "parent present" group, a parent accompanies the child into the scan room, sits on a chair next to the scanner, and is instructed to remain calm and speak gently to help prevent movement. In the "parent absent" group, a radiologic technologist accompanies the child.

- Outcome Measures:

- Step 1 - Completion: Successful completion of all MRI sequences.

- Step 2 - Image Quality: Blinded evaluation of image artifacts (none, mild, or severe).

- Step 3 - Final Success: Completion of MRI with no or only mild artifacts.

Protocol 2: Systematic Neurotoxicity Assessment in Immunotherapy Trials This protocol was developed for prospective evaluation of neurotoxicity in a Phase I anti-CD22 CAR-T cell trial [9].

- CNS Disease Evaluation: Includes routine lumbar punctures pre- and post-therapy for CSF analysis (cell count, protein, glucose, cytospin, flow cytometry for CAR-T cells) and a baseline brain MRI.

- Cognitive Assessment: A brief cognitive battery administered pre- and post-infusion by a psychologist, assessing:

- Attention and Cognitive Flexibility: Dimensional Change Card Sort Test (DCCS).

- Inhibitory Control: Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test.

- Working Memory: List Sorting Working Memory Test.

- Processing Speed: Wechsler Processing Speed Index (Symbol Search and Cancellation subtests).

- Neurologic Symptom Checklist (NSC): An observer-reported checklist completed by the caregiver at baseline, day 14, and day 21-28. It rates the severity and duration of symptoms like hallucinations, disorientation, and depressed mood.

- Biomarker Analysis: Serial serum cytokine levels are measured and correlated with neurotoxicity symptoms and severity to explore etiology.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

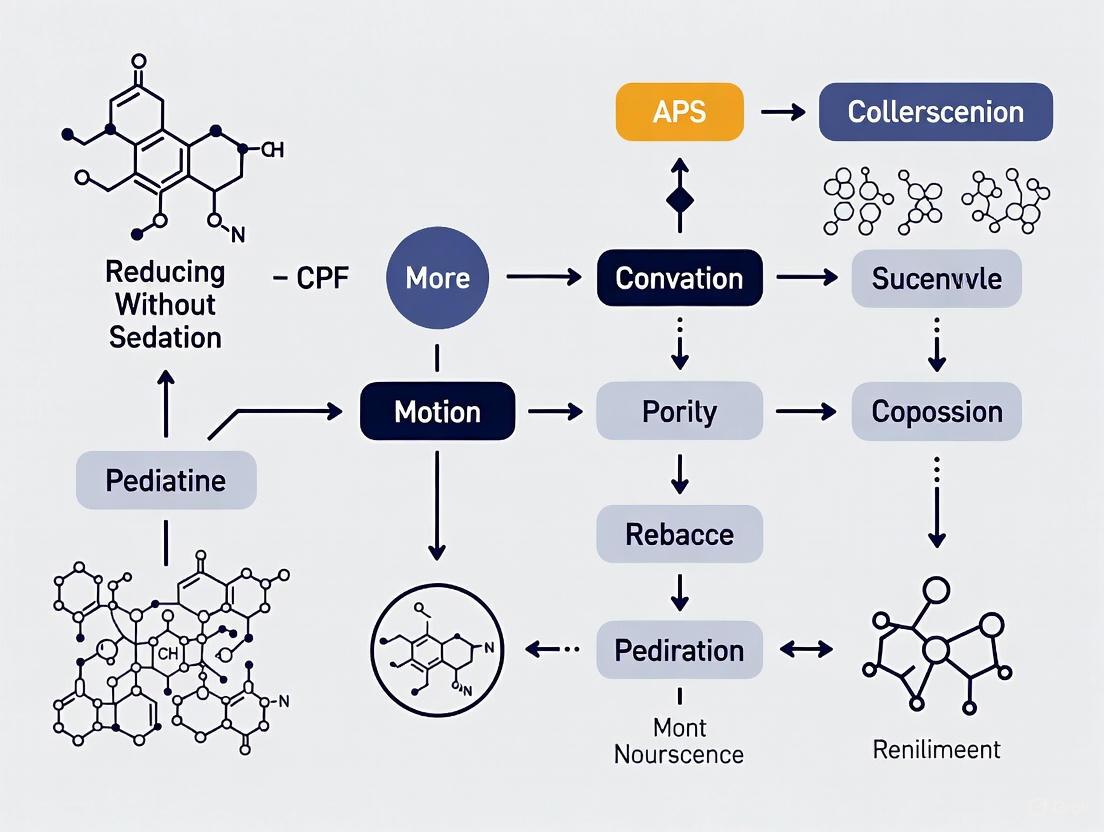

Diagram 1: Anesthetic Neurotoxicity Pathway

Diagram 2: Non-Sedated MRI Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Pediatric Neurotoxicity and Imaging Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bayley Scales of Infant & Toddler Development, 3rd Ed. (Bayley-III) | Gold-standard assessment of neurodevelopment in infants and toddlers (1-42 months). Provides composite scores for cognitive, language, and motor domains. | Used as a primary outcome measure in clinical studies like the GAS trial and cardiac cohort studies [1] [2]. |

| NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery | Computerized battery for assessing cognitive function in children and young adults. Efficient for serial testing. | Includes Dimensional Change Card Sort (cognitive flexibility), Flanker (inhibitory control), and List Sorting (working memory) tests [9]. |

| Wechsler Processing Speed Index (PSI) | Paper-and-pencil test from Wechsler intelligence scales to assess cognitive processing speed. | Comprises Symbol Search and Cancellation subtests; used in conjunction with other batteries [9]. |

| Neurologic Symptom Checklist (NSC) | Observer-reported checklist to systematically capture the type, severity, and duration of neurotoxic symptoms. | Custom-developed for CAR-T trials; can be adapted for sedation studies to document subtle symptoms [9]. |

| Accelerated MRI Sequences | Technical methods to reduce scan time and motion sensitivity, enabling non-sedated MRI. | Includes Parallel Imaging, Compressed Sensing, Simultaneous Multi-Slice, and Radial Sampling [6] [7]. |

| Mock MRI Scanner | A simulated MRI environment used to acclimate children to the sounds and confinement of a real scan. | Often made of wood or other non-magnetic materials; used with toy models for play therapy to reduce anxiety [3] [5]. |

FAQs for a Pediatric Imaging Research Core

FAQ 1: What are the most effective non-sedation techniques for reducing motion in pediatric MRI, and what is their typical success rate?

Several non-sedation techniques have proven effective. A 2025 quality improvement project demonstrated that audiovisual distraction (AVD) technology, when implemented as part of a structured "awake MRI" program, reduced the need for minimal and moderate sedation by 28.8 percentage points while maintaining a 100% diagnostic success rate across the cohort [10]. Furthermore, a 2025 randomized controlled trial found that for children aged 3-6 years, the simple, low-cost intervention of parental presence in the MRI room significantly improved the success rate of non-sedated MRI, with a success rate of 59.1% compared to 18.2% when the parent was absent [11]. These methods are complemented by preparatory techniques involving certified child life specialists and mock scanner training [10] [11].

FAQ 2: Which advanced imaging techniques can help salvage a study affected by motion artifacts?

Beyond behavioral techniques, technological and methodological advancements are crucial for mitigating motion. The following table summarizes key methods, particularly for abdominal MRI, where motion is a significant challenge [6]:

| Method | Brief Explanation | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Parallel Imaging | Accelerates data acquisition by using multiple receiver coils. | Reduces scan time, thereby decreasing the window for motion. |

| Simultaneous Multislice Imaging | Acquires multiple MRI slices at the same time. | Significantly shortens acquisition time. |

| Radial k-Space Sampling | Acquires data in a radial pattern, making it less sensitive to motion. | Inherently motion-insensitive, dispersing artifacts. |

| Compressed Sensing | Acquires fewer data points and uses algorithms to reconstruct the image. | Enables high-quality images from undersampled data, cutting scan time. |

| AI-Based Reconstruction | Uses deep learning models to reconstruct images from limited data. | Reduces scan times and can correct for motion artifacts [10]. |

For post-processing, deep learning methods, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), show promise in actively correcting motion artifacts in already-acquired images, potentially saving time and money by reducing the need for repeat scans [12].

FAQ 3: From a logistical standpoint, how can we improve workflow efficiency to reduce patient wait times and increase scanner throughput?

Optimizing patient flow logistics (PFL) is essential. Studies show that structured PFL interventions can drastically reduce hospital length of stay and emergency department boarding [13]. Key strategies include:

- Real-Time Dashboards: Implementing dashboards to monitor key performance indicators (KPIs) allows for rapid identification of bottlenecks and reallocation of resources [13].

- Process Mapping and Redesign: Analyze the patient journey from scheduling to discharge to eliminate redundancies. This can include implementing online pre-registration and staggered appointment scheduling to smooth patient flow [14] [15].

- Predictive Analytics: Using historical data to forecast busy periods and adjust staffing and scheduling accordingly prevents bottlenecks before they occur [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Sedation Rates in a Research Cohort

Problem: A high percentage of pediatric research participants in your study require sedation to complete MRI scans, introducing cost, risk, and logistical complexity.

Solution: Implement a systematic, tiered screening and intervention protocol.

Diagram: Tiered Screening and Intervention Protocol for Non-Sedated MRI.

Steps:

- Pre-Appointment Screening: Triage patients based on age, developmental level, and past medical experiences. Children 4 years and older should be considered potential candidates for non-sedated MRI [10].

- In-Person Assessment: On the day of the scan, a team (e.g., certified child life specialist, nurse, sedation provider) assesses the child's anxiety, understanding, and temperament [10].

- Apply Tiered Interventions:

- Failover Protocol: For children who cannot tolerate the scan without sedation, have a protocol for immediate, same-day sedation to avoid rescheduling and delays, thus maintaining workflow efficiency [10].

Guide 2: Managing Motion Artifacts in Acquired Image Data

Problem: Acquired research MRI datasets are degraded by motion artifacts, compromising their diagnostic and analytical quality.

Solution: A combined approach of proactive acquisition and post-processing correction.

Diagram: Decision Workflow for Managing Motion Artifacts.

Steps:

- Prevention: Utilize fast acquisition sequences like parallel imaging or compressed sensing to minimize the time during which motion can occur [6].

- Assessment: Determine the severity of the artifact and whether the participant can tolerate a repeat sequence.

- Action:

- If reseaming is feasible: Re-acquire the images using a more motion-robust sequence (e.g., radial k-space sampling) [6].

- If reseaming is not feasible: Employ a post-processing correction algorithm. Deep learning models, particularly those based on a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) framework, have been shown to effectively remove motion artifacts, restoring image quality for analysis [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing an Audiovisual Distraction (AVD) Program

This protocol is based on a successful quality improvement project that reduced sedation use by 28.8% [10].

- Objective: To establish a reproducible workflow for conducting pediatric MRI without sedation using in-bore AVD technology.

- Materials:

- MRI-compatible AVD system (e.g., MRI in-bore video projector).

- Standard clinical MRI scanner.

- Multidisciplinary team (radiologists, technologists, sedation providers, certified child life specialists).

- Methodology:

- Planning: Convene a stakeholder group to design the workflow and select appropriate AVD technology.

- Screening: Identify eligible patients (e.g., initially ages 7+, expanding to 4+, without severe developmental delays) during the scheduling process [10].

- Preparation: On the day of the scan, a child life specialist or nurse prepares the child using age-appropriate explanations and mock scanners.

- In-Room Procedure: The child is positioned in the scanner. The AVD system is activated, and the child selects a movie. A parent may be present to provide additional comfort.

- Exit Strategy: If the child becomes distressed and cannot continue, a pre-arranged protocol for same-day sedation is activated to avoid rescheduling [10].

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Percentage reduction in minimal/moderate sedation use.

- Secondary: Rate of diagnostic quality studies, percentage of studies completed within allotted exam time.

Protocol 2: Randomized Controlled Trial of Parental Presence

This protocol summarizes the methods from a 2025 prospective RCT [11].

- Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the effect of parental presence on the success rate of non-sedated pituitary MRI in children aged 3-10 years.

- Materials:

- Standard 1.5T or 3T MRI scanner.

- Soft toy and wooden mock MRI scanner for preparation.

- Subject Population: Children aged 3-10 years requiring MRI for short stature evaluation, excluding those with known intellectual disabilities.

- Methodology:

- Randomization: Participants are stratified by age (3-6 and 7-10 years) and randomly assigned to "parent present" or "parent absent" groups using block randomization [11].

- Intervention: For the "parent present" group, a parent sits on a chair next to the MRI scanner, within reach of the child, and is instructed to speak gently to prevent movement. In the "parent absent" group, a radiologic technologist accompanies the child.

- Blinding: Image quality is assessed by pediatricians blinded to the group assignment.

- Outcome Assessment: Success is evaluated in three steps:

- Step 1: Completion of all MRI sequences.

- Step 2: Image quality (no, mild, or severe artifacts).

- Step 3: Final success, defined as completion with no or only mild artifacts [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key non-pharmacological "reagents" or tools for a research program focused on reducing motion without sedation.

| Item / Solution | Function in the Research Context |

|---|---|

| MRI-Compatible AVD System | The core technological intervention for behavioral distraction; projects video content into the MRI bore to engage pediatric patients and reduce anxiety and movement [10]. |

| Certified Child Life Specialist (CCLS) | A specialized human resource who prepares children for procedures using developmental support, education, and mock scanners to increase cooperation and success rates [10] [11]. |

| Mock MRI Scanner | A non-functioning replica of an MRI scanner used to acclimate children to the environment, sounds, and confinement, reducing fear and failure rates [11]. |

| Motion-Robust MRI Sequences | Advanced pulse sequences (e.g., radial k-space, compressed sensing) that are less susceptible to motion artifacts, serving as a technical buffer against data loss [6]. |

| AI-Based Artifact Correction Software | A computational tool employing deep learning (e.g., GANs) to post-process and correct for motion artifacts in image data, salvaging otherwise non-diagnostic scans [12]. |

| Parental Presence Protocol | A standardized operational guideline defining the role and positioning of a parent within the MRI suite to provide comfort and improve the child's ability to remain still [11]. |

This technical support guide provides resources for researchers investigating methods to reduce motion artifacts in pediatric medical imaging without sedation. A primary challenge in this field is that patient motion during scanning compromises image quality, often necessitating sedation with its associated risks, costs, and neurodevelopmental concerns. This document synthesizes current evidence and provides practical protocols for implementing and evaluating non-sedation approaches, with a specific focus on parental involvement and patient-centered care strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts in Sedation-Free Imaging

Q1: What is the evidence for parental presence as a motion-reduction strategy? A1: Recent Level I evidence demonstrates that parental presence significantly improves MRI success rates without sedation, particularly in young children. A 2025 randomized controlled trial found that for children aged 3-6 years, scan completion rates were significantly higher when a parent was present (59.1%) compared to when the child was alone (18.2%) [3] [11]. The final success rate (completion with no or mild artifacts) was significantly higher in the parent-present group for this age subgroup, with an odds ratio of 6.50 [3].

Q2: How do technological and preparation interventions compare in effectiveness? A2: Different non-pharmacological approaches show varying effectiveness across age groups, as summarized in Table 1 below. Multi-faceted programs that combine preparation, environmental modification, and distraction typically yield the highest success rates.

Q3: What factors should inform patient selection for non-sedated protocols? A3: Key considerations include:

- Age: Children 3-6 years benefit most from parental presence; those ≥7 years often succeed with preparation alone [3] [11]

- Developmental status: Children with neurodevelopmental disorders often require specialized approaches [16]

- Scan characteristics: Protocol length and motion sensitivity significantly impact success [16]

- Temperament: Baseline anxiety levels influence intervention selection [17]

Q4: How can researchers objectively measure intervention success? A4: Standardized metrics include:

- Completion rate: Percentage of scans fully acquired [3] [16]

- Image quality: Blindly scored artifact assessment using standardized scales [3] [18] [17]

- Anxiety measures: Validated instruments like the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children [17]

- Process measures: Scan time, need for rescans, parental satisfaction [19]

Troubleshooting Guides: Implementing Non-Sedation Protocols

Guide: Implementing Parental Presence Protocols

Problem: Inconsistent implementation of parental presence reduces potential benefits. Solution: Standardize parental involvement through this workflow:

Validation Data: This protocol achieved 70.0% final success rate versus 55.0% in parent-absent groups, with the most significant benefits in children aged 3-6 years (P=0.012) [3].

Guide: Optimizing Scan Environment and Protocols

Problem: Standard MRI environments increase pediatric anxiety and motion. Solution: Implement child-centered modifications:

- Acoustic noise reduction: Apply quiet imaging sequences (e.g., Quiet Suite) with maximal noise reduction for localizer scans [3]

- Visual modifications: Use projected visuals/themes in bore; coordinate lighting [19]

- Rapid imaging protocols: Implement parallel imaging, simultaneous multisection imaging, and compressed sensing [18] [16]

- Mock scanner training: Familiarize children using toy scanners and simulation [19]

Technical Specifications: Optimized protocols reduced average scan duration from 45±10 minutes to approximately 20-25 minutes while maintaining diagnostic quality [18] [17].

Quantitative Outcomes: Evidence Tables for Research Design

Table 1: Comparative Effectiveness of Non-Sedation Interventions

| Intervention Type | Age Group | Success Rate | Key Metrics | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Presence [3] [11] | 3-6 years | 70.0% | OR=6.50 (95% CI: 1.64-25.76) for final success | RCT, n=80 |

| Audiovisual Distraction (AVD) [16] | 4-18 years | 100% completion | 28.8% reduction in sedation use | Quality Improvement, n=92 |

| Child-Centered Care Program [19] | 4-10 years | 88% child comfort | 92% parental security vs. 79% control | Prospective Survey, n=265 |

| Audiovisual Preparation [17] | 7-11 years | Significantly improved image quality (P=0.005) | Reduced state anxiety (P=0.004) | RCT, n=48 |

Table 2: Motion Artifact Classification for Image Quality Assessment

| Artifact Grade | Definition | Research Implications | Sample Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | No motion artifacts detected; fully diagnostic | Optimal for quantitative analysis | 23/52 (44.2%) [3] |

| Mild | Minor artifacts not affecting diagnostic quality | Acceptable for most clinical research | 27/52 (51.9%) [3] |

| Severe | Significant artifacts compromising diagnostic utility | Requires scan repetition or exclusion | 2/52 (3.8%) [3] |

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Methodologies for Research

Protocol: Randomized Evaluation of Parental Presence

Objective: To quantitatively assess the impact of parental presence on MRI success rates without sedation.

Population: Children aged 3-10 years without neurodevelopmental disorders [3].

Stratification and Randomization:

- Stratify by age groups (3-6 and 7-10 years)

- Use block randomization within strata (blocks of 4)

- Allocate to parent present vs. absent groups [3] [11]

Intervention Protocol:

- Parent present group: Parent accompanies child, sits beside scanner, provides calm reassurance

- Parent absent group: Child accompanied by radiologic technologist only

- Standardized preparation: Both groups receive identical preparation by child life specialist or pediatrician [3]

Outcome Assessment:

- Step 1 - Completion: Ability to complete all MRI sequences

- Step 2 - Image Quality: Blinded assessment of artifacts (none, mild, severe)

- Step 3 - Final Success: Completion with no or mild artifacts only [3]

Statistical Considerations:

- Sample size: 40 per group (total n=80) provides adequate power for primary endpoint

- Analysis: Intention-to-treat with appropriate tests for categorical outcomes [3]

Protocol: Implementation of Audiovisual Distraction Systems

Equipment Setup:

- MRI-compatible AVD system (e.g., in-bore video projection)

- Child-friendly content selection (validated for anxiety reduction)

- Hearing protection with integrated audio capability [16] [17]

Patient Selection Criteria:

- Inclusion: Age ≥4 years, head-first positioning, scan duration <60 minutes (initial phase)

- Exclusion: Visual impairment, severe developmental delay, severe ASD [16]

Implementation Workflow:

Quality Control: All studies reviewed by radiologist before exam conclusion; motion sensitivity scoring for protocol optimization [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Pediatric Imaging Research

| Research Tool | Specifications | Research Application | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mock MRI Scanner | Wooden or plastic simulator with noise playback | Patient familiarization and training | [3] [19] |

| Audiovisual Distraction System | MRI-compatible projection with child-friendly content | Anxiety reduction during scanning | [16] [17] |

| Standardized Anxiety Assessment | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) | Quantifying intervention effectiveness | [17] |

| Image Quality Rating Scale | 3-point artifact scale (none, mild, severe) | Primary outcome assessment | [3] |

| Child Life Specialist Protocol | Standardized preparation and support procedures | Ensuring consistent patient preparation | [3] [16] |

| Accelerated MRI Sequences | Parallel imaging, compressed sensing, AI reconstruction | Reducing scan time and motion sensitivity | [18] [16] |

Motion artifacts represent one of the most significant obstacles in pediatric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), often rendering scans non-diagnostic and compromising research outcomes. Unlike adult patients, children present unique physiological and psychological challenges that complicate motion-free imaging. The conventional solution of sedation introduces its own risks, including potential neurotoxicity and respiratory complications, driving the urgent need for effective non-pharmacological motion mitigation strategies. This technical support guide examines the fundamental barriers to motion-free imaging in children and provides evidence-based troubleshooting methodologies for researchers and clinical scientists working to reduce sedation in pediatric imaging research.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Motion in Pediatric Imaging

What specific types of motion most severely degrade pediatric image quality?

Research utilizing electromagnetic motion tracking has identified key metrics that correlate with image quality degradation. In a study of 77 pediatric patients, both motion-free time (as a ratio of total scan time) and average displacement from a reference position were highly correlated with image quality, whereas maximum displacement was a less reliable predictor. Notably, 14.3% of patients with average displacements greater than 0.5 mm and 18.2% with less than 90% motion-free time resulted in non-diagnostic images [20]. The most problematic motions are those occurring during the acquisition of k-space center, which generate more pronounced artifacts [20] [21].

Which age groups present the greatest challenges for non-sedated imaging?

Success rates for non-sedated MRI vary significantly by developmental stage. Children aged 3-6 years present particular difficulties, with one study showing only 18.2% completion rates without parental presence. However, with intervention strategies like parental presence, completion rates in this age group can increase to 59.1% [3]. Infants (0-2 years) often respond well to feed-and-wrap techniques, while children over 7 years generally demonstrate better cooperation, especially with distraction techniques [18] [22] [3].

What are the quantified risks of sedation that justify alternative approaches?

Recent evidence indicates that 8.6% of children under sedation/anesthesia experience adverse events, with 57.7% of these occurring during MRI scans [20]. A 2025 quality improvement project reported that institutional sedation rates for pediatric MRI referrals reached 92% prior to implementing alternatives, with 55% requiring deep sedation [16]. These risks, coupled with concerns about potential neurotoxicity, have accelerated the development of non-sedated imaging protocols [23] [16].

How effective are current motion correction technologies?

Emerging technologies show promising results. The Scout Accelerated Motion Estimation and Reduction (SAMER) technique, evaluated in 2025, demonstrated motion artifact improvement in 79% of cases (19/24), with 50% of previously non-diagnostic cases reclassified as diagnostic after correction [24]. Deep learning-based reconstruction techniques like Deep Resolve have enabled scan time reductions of up to 50% for musculoskeletal protocols while maintaining diagnostic quality [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Implementing Non-Sedated Imaging Protocols

Preparation Phase Challenges

Problem: Patient anxiety and non-cooperation during positioning

Solution: Implement comprehensive preparation protocols

- Mock scanner training: Utilize practice sessions with simulated MRI environments to familiarize children with the procedure [3] [16].

- Preparation media: Develop institution-specific videos demonstrating the MRI process, facilities, and staff to reduce pre-procedural anxiety [22].

- Child Life Specialist involvement: Engage specialists to provide age-appropriate explanation and coping strategies [3] [16].

- Parental education: Instruct parents on preparation techniques, including keeping infants awake before appointments and timing feeding schedules [22] [21].

Problem: Inadequate screening for procedure suitability

Solution: Establish tiered assessment criteria

- Develop motion sensitivity scores for different protocols to match patient capabilities with appropriate techniques [16].

- Implement in-person assessments by Child Life Specialists, nurses, and sedation providers to evaluate cooperation potential [16].

- Consider developmental age, previous medical experiences, and specific anxieties when determining approach [3].

Acquisition Phase Challenges

Problem: Motion artifacts degrading image quality

Solution: Implement multi-layered motion mitigation strategies

Table: Motion Reduction Techniques and Applications

| Technique | Mechanism | Best Applications | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Imaging Sequences (GRE, EPI, bSSFP) | Reduced acquisition time | All pediatric populations, especially uncooperative children | Scan time reduction up to 50% [22] |

| Parallel Imaging | Simultaneous data acquisition with multiple coils | General pediatric imaging | 40% scan time reduction [3] |

| Compressed Sensing | Random k-space undersampling with iterative reconstruction | 3D isotropic imaging | Isotropic 3D MRI in under 3 minutes [21] |

| Radial k-space Sampling (PROPELLER/BLADE) | Oversampling of k-space center | High-contrast structures (neuroimaging) | Effective for moderate motion [21] |

| SAMER Method | Retrospective motion correction using scout data | Brain imaging in awake patients | 79% improvement in motion artifacts [24] |

Problem: In-bore anxiety and movement during acquisition

Solution: Create supportive scanning environment

- Audiovisual distraction: Implement MRI-compatible systems allowing movie viewing or music listening during scans [22] [16].

- Parental presence: Allow parents to remain within reach of the child during scanning, particularly effective for ages 3-6 years [3].

- Proper immobilization: Use specialized pediatric positioning aids, foam padding, and vacuum immobilizers to minimize movement while maintaining comfort [22] [21] [25].

- Acoustic noise reduction: Utilize quiet imaging sequences, hearing protection, and noise-insulating techniques to reduce startle responses [3] [16].

Technical Optimization Challenges

Problem: Suboptimal protocol parameters for pediatric populations

Solution: Implement age-specific protocol modifications

Table: Age-Specific Protocol Considerations

| Age Group | Key Challenges | Recommended Technical Adjustments | Success Rate Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants (0-2 years) | Inability to follow instructions, temperature regulation | Feed-and-wrap technique, smaller FOV, thinner slices, longer TR for improved SNR | 90-95% success with feed-and-wrap [16] |

| Young Children (3-6 years) | High anxiety, limited impulse control | Parental presence, rapid sequences, AVD, immobilization devices | Completion increased from 18.2% to 59.1% with parental presence [3] |

| Older Children (7+ years) | Boredom, discomfort with prolonged stillness | Audiovisual distraction, explanation of procedure, comfortable positioning | 75% completion with AVD vs. 55% without [3] [16] |

Problem: Balancing scan time with diagnostic image quality

Solution: Implement accelerated protocols with AI reconstruction

- Utilize deep learning-based reconstruction (e.g., Deep Resolve) to maintain image quality despite reduced acquisition times [22].

- Develop protocol-specific acceleration factors based on motion sensitivity scores [16].

- Combine multiple acceleration techniques (parallel imaging + compressed sensing) for synergistic time reduction [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Awake MRI Program with Audiovisual Distraction

Based on quality improvement project with 320 patients [16]

Inclusion Criteria:

- Age ≥4 years (initially ≥7 years, expanded after PDSA cycles)

- Head-first MRI position

- Any scan duration (initially <60 minutes, restrictions removed)

- Absence of severe developmental delay or autism spectrum disorder

Workflow:

- Pre-procedural screening: Identification of eligible candidates through clinical information review and family communication

- In-person assessment: Evaluation by Child Life Specialist, nurse, and sedation provider on day of scan

- AVD setup: Installation of MRI-compatible video projection system (e.g., MRI in-bore video system)

- Positioning: Head-first positioning with appropriate immobilization devices

- Acquisition: Implementation of accelerated MRI protocols with noise reduction techniques

- Contingency planning: Immediate conversion to sedation for failed awake attempts

Outcomes: 28.8 percentage point reduction in minimal/moderate sedation use, 100% diagnostic quality achieved in AVD group, 96% of studies completed within allotted exam time [16]

Protocol 2: Quantitative Motion Measurement and Correlation

Based on study of 77 pediatric patients [20]

Motion Tracking Method:

- Electromagnetic tracker with two forehead sensors

- Modified T1-weighted 3D GRE sequence with embedded bipolar gradients

- Real-time position recording relative to magnet isocenter

- Accuracy: +/- 0.1 mm (phantom-validated)

Motion Metrics:

- Maximum displacement from reference position

- Mean displacement from reference (when k-space center acquired)

- Motion-free time (% of scan with <0.2 mm displacement)

Image Quality Assessment:

- Blind radiologic evaluation using 4-point Likert scale

- Grade 1: Non-diagnostic (severe motion artifacts)

- Grade 4: No visible motion artifacts

Key Findings: Both motion-free time ratio and average displacement highly correlated with image quality, providing thresholds for predicting diagnostic acceptability [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Resources for Pediatric Motion-Free Imaging Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Electromagnetic Motion Tracking | Quantitative measurement of patient motion during acquisition | Robin Medical Inc. tracker [20] |

| MRI-Compatible Audiovisual Systems | Patient distraction and anxiety reduction during scanning | NordicNeuroLab AS visualization systems; PDC Inc. in-bore video projection [22] [16] |

| Pediatric Immobilization Devices | Gentle motion restriction while maintaining comfort | Pearl Technology Multipads; Domico Med-Device Huggers, MedVac Immobilization System [22] [25] |

| Accelerated MRI Sequences | Reduced acquisition time to minimize motion opportunities | Deep Resolve; PROPELLER; Compressed Sensing; Parallel Imaging [22] [21] |

| Motion Correction Algorithms | Retrospective correction of motion artifacts in acquired data | SAMER (Scout Accelerated Motion Estimation and Reduction) [24] |

| Quiet Imaging Packages | Acoustic noise reduction to minimize startle response | Siemens Quiet Suite [3] |

| Mock MRI Scanners | Patient preparation and anxiety desensitization | Wooden mock scanners; simulation environments [3] [16] |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathways

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several research challenges remain in optimizing motion-free pediatric imaging. Future research priorities include:

- Predictive Modeling: Development of robust algorithms to predict individual patient motion risk based on age, developmental stage, and previous medical experiences

- Real-Time Adaptive Imaging: Creation of MRI sequences that dynamically adjust to detected motion during acquisition

- Standardized Outcome Metrics: Establishment of consensus measures for motion artifact quantification and image quality assessment across research studies

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Comprehensive evaluation of the economic and clinical tradeoffs between sedation and non-sedated imaging protocols

- Novel Sensor Technologies: Integration of non-contact motion detection systems (camera-based, physiological monitoring) for more accurate motion tracking

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with artificial intelligence playing an increasingly central role in both acquisition acceleration and motion correction. By addressing these fundamental physiological and psychological barriers, researchers can continue to advance toward the ultimate goal of reliable, diagnostic-quality pediatric imaging without sedation.

A Multimodal Toolkit: Evidence-Based Techniques for Motion Reduction Without Sedation

Minimizing motion artifacts is a critical challenge in pediatric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research. The use of sedation, while effective for ensuring stillness, carries risks including respiratory depression, potential neurotoxicity, and prolonged hospital visits, making non-sedation approaches methodologically and ethically preferable for research protocols [16] [10]. This guide details evidence-based, non-pharmacological strategies for successful MRI acquisition in child participants. Implementing these patient preparation and environmental adaptation techniques is essential for reducing data loss, improving image quality, and upholding the highest ethical standards in developmental neuroscience and pediatric drug development research.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Common Research Scenarios

FAQ 1: Which children are the best candidates for non-sedated MRI in a research setting? Success is highly age-dependent. Children aged 3-6 years represent the most challenging cohort, but studies show parental presence can significantly improve success rates in this group [3] [11]. Older children (7-10 years) are often capable of following instructions and may benefit less from parental presence but more from technological aids like audiovisual distraction (AVD) [3] [16]. For infants, the feed-and-swaddle technique is highly effective, with success rates ranging from 90-95% [16] [26]. Researchers should screen for neurodevelopmental disorders, severe anxiety, or sensory impairments that may require alternative strategies [16] [10].

FAQ 2: A participant cannot tolerate the scanner noise. What are the immediate steps? First, ensure universal hearing protection is correctly applied, using both earplugs and noise-attenuating headphones [26]. Second, employ "quiet" MRI scanning sequences. These protocols, available on modern scanners (e.g., Siemens' Quiet Suite), can significantly reduce acoustic noise by modifying gradient slew rates and pulse sequences [3] [27]. As a preemptive measure, incorporate exposure to recorded scanner noises during mock training sessions to desensitize participants [3] [28].

FAQ 3: How can we predict which participants will succeed without sedation? While no single predictor is perfect, a pre-scan behavioral assessment is highly recommended. This can be conducted by a child life specialist or a trained researcher and should evaluate the child's temperament, anxiety level, and understanding of the procedure [16] [10]. Interestingly, a study found that easily obtainable factors like "crying during routine vaccinations" or "number of siblings" were not reliable predictors of MRI success, underscoring the need for a tailored, in-person assessment [3] [29].

FAQ 4: What is the first-line intervention for a young child (3-6 years) showing distress during scan preparation? The evidence strongly supports implementing parental presence as a first-line strategy. A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that for children aged 3-6 years, having a parent in the scan room significantly increased the completion rate from 18.2% to 59.1% [3] [11]. Instruct the parent to remain calm, speak gently to their child, and provide reassurance without physical intervention that could cause motion [3].

FAQ 5: Our motion artifact rates are high despite participant cooperation. What technical solutions can we implement? Integrate advanced acquisition and reconstruction technologies into your protocol. Parallel imaging and simultaneous multi-slice scanning can reduce scan time, thereby decreasing the window for motion [16] [18]. Furthermore, utilize motion correction algorithms, which can be based on external optical tracking or software-based navigators [27] [18]. For post-processing, artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning models are now capable of reconstructing high-quality images from motion-corrupted data and performing super-resolution enhancement [27].

The following tables consolidate key performance metrics for various interventions, providing a basis for protocol selection and power calculations.

Table 1: Success Rates of Primary Non-Sedation Interventions

| Intervention | Target Age Group | Reported Success Rate / Key Metric | Key Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Presence [3] | 3-6 years | 59.1% completion rate vs. 18.2% without parent | Prospective RCT; pituitary MRI |

| Audiovisual Distraction (AVD) [16] | 4-18 years | 100% completion (92/92 patients); 28.8% reduction in sedation use | Quality improvement project |

| Mock Scanner Training [28] | 6-9 years | Significant reduction in head motion after a 5.5-minute training | Growth curve study |

| Feed-and-Swaddle [26] | Infants | 51% of sites reported >75%-100% success | International survey |

| Child Life Specialist [26] | Children/Teens | Most sites reported >50%-75% success; crucial for preparation | International survey |

Table 2: Impact of Protocol Optimization on Key Workflow Metrics

| Performance Metric | Before Optimization [18] | After Optimization [18] | Key Changes Implemented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Scan Duration | 45 ± 10 minutes | 25 ± 7 minutes | Fast sequences (e.g., single-shot FSE), parallel imaging |

| Sedation Rate | 70% | 25% | Combined non-pharmacological strategies & protocol tweaks |

| Scans with Motion Artifacts | 40% (in infants & young children) | Significantly reduced (p<0.05) | Motion correction software, age-specific parameters |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Parental Presence in MRI

This protocol is based on a prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trial that demonstrated high efficacy for children aged 3-6 years [3] [11].

Methodology:

- Participant Stratification: Stratify participants by age (e.g., 3-6 years and 7-10 years) to account for developmental differences.

- Randomization: Use block randomization within each age group to assign participants to either "parent present" or "parent absent" groups.

- Parent Preparation: For the parent-present group, provide brief, standardized instructions prior to the scan. Parents should be instructed to:

- Remain calm and speak in a gentle, reassuring tone.

- Avoid sudden movements.

- Focus on providing verbal reassurance rather than physical contact that could cause motion.

- Safety Screening: Screen all accompanying parents for MRI contraindications (e.g., metal implants, pregnancy) before allowing them into the scan room.

- Procedure: The parent is provided with a wooden or non-metallic chair placed next to the scanner bore, within reach of the child. They remain there for the duration of the scan [3].

- Success Metrics:

Protocol for Audiovisual Distraction (AVD) Implementation

This protocol is derived from a successful quality improvement project that significantly reduced sedation needs [16] [10].

Methodology:

- Technology Setup: Implement an MRI-compatible in-bore AVD system (e.g., a video projector that displays a movie onto the inner surface of the scanner bore). This is typically suitable only for head-first positioning [16].

- Candidate Selection: Use a multi-step screening process:

- Pre-appointment Review: Identify potential candidates based on age (start with ≥7 years, can expand to ≥4 years), diagnosis, and scan type/duration [16].

- In-person Assessment: On the day of the scan, a certified child life specialist (CCLS), nurse, and sedation provider conduct a joint assessment of the child's temperament, demeanor, and anxiety level to determine final eligibility [10].

- Workflow Integration: Create a clear "awake MRI" pathway. Children who fail the AVD attempt should be seamlessly converted to a sedated protocol on the same day to avoid rescheduling and data loss [16].

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Percentage reduction in the use of minimal/moderate sedation.

- Balance Measures: Proportion of diagnostic studies and adherence to allotted exam times [10].

Protocol for Mock Scanner Training

This protocol leverages findings that a brief mock scan training can effectively suppress head motion in children and adolescents [28].

Methodology:

- Mock Scanner Session: Conduct a training session in a mock MRI scanner that replicates the look, sound, and confined space of a real scanner. The session should include:

- Exposure to simulated scanner noises.

- Practice lying still.

- Training on a motion-tracking feedback system, if available.

- Duration: A single, short session (e.g., 5.5 minutes) has been shown to be effective [28].

- Target Group: The intervention is particularly beneficial for younger children (aged 6-9 years) who demonstrate increased head motion [28].

- Success Metric: The primary outcome is a reduction in head motion parameters (e.g., framewise displacement) during the subsequent real MRI scan compared to pre-training baselines or control groups.

Implementation Workflows

The following diagrams outline logical workflows for integrating these strategies into a research pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Non-Sedated Pediatric MRI Research

| Item / Resource | Specification / Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mock MRI Scanner | Replicates scanner environment (bore, noise); can be full-scale or small-scale. | Participant acclimatization and behavioral training to reduce anxiety and motion [28] [26]. |

| MRI-Compatible AVD System | In-bore video projection or goggle systems; must be MR-safe. | Provides cognitive distraction during scanning, improving compliance and stillness [16]. |

| Child Life Specialist (CCLS) | Certified professional trained in child development and healthcare coping. | Conducts pre-scan preparation, in-person assessments, and provides procedural support [16] [30] [26]. |

| Quiet MRI Sequences | Pulse sequences with reduced gradient slew rates (e.g., Quiet Suite). | Minimizes acoustic noise, a major stressor, facilitating natural sleep or quiet rest [3] [27]. |

| Motion Correction Software | Algorithms for prospective (real-time) or retrospective motion correction. | Mitigates the impact of residual motion on image quality, salvaging otherwise corrupted data [27] [18]. |

| Pediatric RF Coils | Head, torso, and extremity coils sized for infants and children. | Improve signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution for smaller anatomical structures [27] [18]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our pediatric participants are still exhibiting high stress levels upon entering the MRI suite, despite the AVD system being functional. What preparatory protocols are recommended?

A1: Implement a structured preparatory protocol that begins before the child enters the scanning room.

- Filmed Modeling (FM): Prior to the scan, show children a short, child-friendly video that models the MRI procedure. The video should feature a peer successfully undergoing the scan, demonstrating appropriate behavior and familiarizing the child with the environment and sounds [31].

- Control and Choice: Empower children by allowing them to choose the first video or audiovisual content they will watch during the scan. This sense of control has been shown to improve calmness and cooperation [32].

- Combined Approach: Research indicates that a combination of AVD and filmed modeling is more effective in reducing anxiety and fear than either technique used alone [31].

Q2: We are experiencing significant motion artifacts in our imaging data from younger children (aged 6-10). How can the AVD content be optimized to reduce this?

A2: Motion artifacts are often a direct result of anxiety and a failure to engage the child's attention. Optimize content specifically for this age group.

- Content Pacing: Use calming, slow-paced visuals. Fast-paced content can overstimulate children and reduce their ability to follow instructions or regulate movement [32].

- Visual Focus: Design or select content where character movement is focused on the center of the screen. This helps minimize head motion and eye movements that can cause artifacts [32].

- Content Integration: A study on pediatric MRI found that a child-friendly audiovisual intervention significantly reduced scan issues (such as repeated sequences) and staff-reported stress levels specifically in children aged 6-10 years [32].

Q3: What are the most reliable physiological and psychometric metrics to quantitatively assess the efficacy of our AVD intervention in reducing anxiety?

A3: A multi-modal assessment strategy is recommended to capture both physiological and psychological dimensions of anxiety.

Table 1: Metrics for Assessing AVD Efficacy in Pediatric Anxiety Reduction

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description and Application | Evidence of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological | Salivary Cortisol | Stress hormone measured from saliva samples pre- and post-intervention. A decrease indicates reduced physiological stress [31]. | [31] |

| Pulse Rate | Monitored via pulse oximeter. A significant decrease from pre- to post-procedure is associated with lower anxiety [31]. | [31] | |

| Psychometric Scales | Facial Image Scale (FIS) | A visual scale of facial expressions from happy to very unhappy; used for children to self-report feelings [31]. | [31] |

| Fear Assessment Picture Scale (FAPS) | A picture-based scale used to assess a child's level of fear in a medical setting [31]. | [31] | |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) | A questionnaire used to measure state anxiety (transient) and trait anxiety (dispositional) in children [33]. | [33] | |

| Behavioral Observation | Modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale | An observational scale where staff rate behaviors (e.g., crying, clinging) exhibited by the child in the medical setting [32]. | [32] |

| Staff-Reported Stress Question | Staff answer "How stressed was the child?" on a Likert scale (e.g., 1-6) at multiple time points [32]. | [32] |

Q4: We are encountering technical failures with our in-bore AVD system. What are common complex AV issues and their solutions in a research environment?

A4: Research environments demand high reliability. Common issues often extend beyond simple connections.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Complex AV System Issues

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| System-wide Control Failure | Control system software crash or firmware incompatibility. | Perform root cause analysis on interconnected devices. Leverage system diagnostic logs. Ensure all firmware is updated and compatible [34]. |

| No Video/Audio Feed to In-Bore Display | Connection failure (e.g., HDMI), network disruption, or incorrect source selection on the control system. | Check physical connections and network stability. Use diagnostic software to verify signal path. Reboot and reconfigure the control system interface [34] [35]. |

| Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) | EMI from the MRI scanner affecting AV equipment or cables. | Use MRI-compatible and properly shielded AV equipment and cables. Assess cable routing to minimize interference [34]. |

| Integration Challenge with Legacy Systems | New AVD components conflicting with existing hospital or lab IT/AV infrastructure due to unsupported protocols. | Simulate the problem scenario to isolate the conflict. Collaborate with AV specialists familiar with the MRI environment to resolve compatibility issues [34]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Evaluating AVD with Filmed Modeling for Pediatric MRI

This protocol synthesizes methodologies from recent clinical studies to provide a framework for research on AVD systems [31] [33] [32].

1. Study Design and Population

- Design: Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). Participants are randomly assigned to an intervention group (AVD + FM) or a control group (standard care without AVD).

- Participants: Pediatric patients aged 6-12 years, scheduled for a first, awake MRI. Exclusion criteria typically include neurological disorders affecting stillness, developmental/cognitive disorders, or conditions requiring sedation [33] [32].

- Sample Size: Calculation should be based on a power analysis. For reference, recent studies have utilized samples ranging from 48 to 175 participants [33] [32].

2. Intervention Protocol

- AVD System: Utilize an MRI-compatible system with an in-bore screen (visible via a head-mounted mirror), a sound system, and optional ambient lighting [32].

- Intervention Group:

- Preparatory Phase (Filmed Modeling): Before entering the scan room, children view a 5-10 minute filmed modeling video. This video features a peer model calmly undergoing the MRI procedure, explaining the sounds and demonstrating cooperation [31].

- In-Bore Phase (AVD): During the scan, children watch specially designed, calming audiovisual content (e.g., slow-paced animated clips with central visual focus). The child is given a choice of content to enhance perceived control [32].

- Control Group: Undergoes the MRI scan with standard clinical care and staff reassurance, but without the structured AVD or FM intervention [31] [32].

3. Data Collection and Outcome Measures Data is collected at multiple time points: Pre-intervention (T1), Post-intervention/Pre-scan (T2), During scan (T3), and Post-scan (T4).

- Primary Outcomes:

- Secondary Outcomes: Physiological measures (e.g., pulse rate, salivary cortisol) where feasible [31].

4. Data Analysis

- Employ repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to compare changes in anxiety scores over time between the intervention and control groups [32].

- Use ANOVA or Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the number of repeated sequences and image quality scores between groups, potentially controlling for covariates like the total number of sequences [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for AVD Experiments

| Item | Function in Research | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MRI-Compatible AVD System | Core intervention delivery. Displays video and plays audio within the MRI suite without causing interference. | Must include in-bore screen or projector, head-mounted mirror, MRI-safe headphones, and a media player. Systems like "Ambient Experience" are specifically designed for this [32]. |

| Validated Psychometric Scales | Quantify the primary psychological outcome (anxiety). | Use age-appropriate, validated scales. Examples: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC), Facial Image Scale (FIS) [31] [33]. |

| Physiological Data Acquisition Tools | Provide objective, biometric data on stress and anxiety levels. | Pulse oximeter (for pulse rate), saliva collection kits (for cortisol analysis), digital thermometer [31]. |

| Child-Friendly Audiovisual Content Library | The active ingredient of the distraction intervention. | Content should be slow-paced, have center-screen visual focus, and feature familiar, calming characters. Collaboration with content creators (e.g., animation studios) may be beneficial [32]. |

| Filmed Modeling (FM) Video | Prepares the child for the procedure, reducing fear of the unknown. | Video should be ~10 minutes, feature a peer model, and explicitly address procedural steps, sounds, and desired behaviors [31]. |

| Data Logging & Analysis Software | For extracting and analyzing scan performance metrics. | Software capable of parsing MRI system logfiles to extract metrics like exam length, number of sequence repeats, and pauses [32]. Statistical software (e.g., SPSS, R) is essential for data analysis. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

FAQs: Optimizing Hardware and Protocols for Pediatric MRI

FAQ 1: What are the most effective hardware solutions for reducing motion in awake pediatric patients? Specialized head stabilization devices are highly effective. For instance, the MR-MinMo head stabilizer was specifically designed for high-resolution neuroimaging in awake participants, typically aged 6 and older. It uses a polycarbonate frame with inflatable pads and a hinged halo to gently immobilize the head, significantly reducing motion artifacts, particularly in pediatric volunteers [36]. Furthermore, MRI-compatible audiovisual distraction (AVD) systems, such as an in-bore video projector, allow children to watch movies during the scan, addressing anxiety and boredom that lead to movement [10].

FAQ 2: Which protocol modifications are key to shortening scan times and minimizing motion? Implementing fast imaging sequences is fundamental. Key techniques include:

- Parallel Imaging: Techniques like GRAPPA accelerate acquisition by undersampling k-space [11].

- Simultaneous Multi-Slice Imaging: Acquires data from multiple slices at once, dramatically reducing scan time [27].

- Compressed Sensing: Leverages image sparsity to reconstruct high-quality images from significantly fewer data points [10] [27].

- Single-Shot Sequences: Such as single-shot fast spin echo, are highly resilient to motion [18]. Integrating these into age-specific protocols with adjusted FOV, slice thickness, and TR further optimizes efficiency and signal-to-noise ratio [18].

FAQ 3: How can researchers quantitatively assess the effectiveness of their motion reduction strategies? Mean Framewise Displacement (FFD) is a standard quantitative metric for measuring head motion in functional MRI. It provides a scalar value (in mm) of how much a participant's head moves from one volume to the next throughout a scan. Analyzing the distribution of mean FFD values and the percentage of scans kept under specific thresholds (e.g., 0.10 mm, 0.15 mm) allows for objective comparison between different intervention groups [37].

FAQ 4: What non-hardware-based practices improve success rates for non-sedated MRI? A combination of preparatory and in-scanner techniques is highly effective:

- Mock Scanner Training: Placing participants in a simulated MRI environment to desensitize them and practice remaining still [37].

- Parental Presence: For children aged 3-6 years, having a parent in the scan room significantly improves the success rate of completing a non-sedated MRI [11].

- Child Life Specialists: These professionals use age-appropriate preparation, education, and support to reduce anxiety and improve cooperation [10] [26].

- In-Scan Incentive Systems: Providing positive reinforcement for keeping still during the scan can improve compliance in pediatric participants [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Excessive Motion Artifacts in School-Age Children (7-12 Years)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Anxiety and lack of preparation leading to an inability to lie still.

- Solution: Implement a comprehensive mock scanner protocol. This should include familiarization with scanner sounds, training on keeping still, and practice in a simulated environment. Combine this with an in-scan incentive system to motivate the child [37].

- Cause 2: Boredom and discomfort during long acquisition times.

- Cause 3: Inadequate physical stabilization.

- Solution: Beyond standard foam padding, employ a dedicated pediatric head stabilizer like the MR-MinMo device. This provides comfortable but firm immobilization, keeping motion within a correctable regime for post-processing algorithms [36].

Problem: Suboptimal Image Quality in Preschool Children (3-6 Years) Without Sedation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: High anxiety and developmental inability to understand and follow instructions.

- Solution: Leverage parental presence as a first-line strategy. A randomized study found parental presence in the scan room significantly improved non-sedated MRI success in this age group [11].

- Solution: Engage a Certified Child Life Specialist (CCLS). The CCLS should perform an in-person assessment on the day of the scan to evaluate the child's readiness and provide tailored, hands-on preparation and support [10].

- Cause 2: Protocol not optimized for faster acquisition.

Quantitative Data on Motion Reduction Strategies

The table below summarizes key performance data from recent studies on motion reduction techniques.

Table 1: Efficacy of Non-Sedation Motion Reduction Strategies in Pediatric MRI

| Technique | Study Population | Key Outcome Measure | Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audiovisual (AVD) Distraction | Children aged 4-18 years | Reduction in minimal/moderate sedation use | 28.8 percentage point decrease | [10] |

| MR-MinMo Head Stabilizer | Pediatric & adult volunteers (7T) | Reduction in motion artifacts (NGS metric) | Significant reduction, particularly in pediatric subjects | [36] |

| Parental Presence | Children aged 3-6 years | Odds Ratio for MRI success | OR: 6.50 (95% CI: 1.64–25.76) | [11] |

| Mock Scanner + Incentives | Children aged 7-17 years | Scans exceeding 0.20 mm mean FFD threshold | 4.17% of scans (vs. 33.9% in control group) | [37] |

| Feed-and-Swaddle (Infants) | International survey of institutions | Success rate reported by sites | 51% of sites reported >75%-100% success | [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Reduction

Detailed Protocol 1: Mock Scanner Training for Long-Duration fMRI

This protocol is designed to prepare children for 60-minute scan sessions, enabling the collection of high-quality, low-motion data [37].

- Primary Goal: To desensitize participants to the MRI environment and train them to minimize head movement.

- Materials: Mock MRI scanner (replica with sound system for playing recorded scanner noises), weighted blanket or bean bag, communication system, incentive system (e.g., token economy).

- Procedure:

- Pre-training: Explain the importance of keeping still using simple terms and visual aids.

- Familiarization: Have the child lie in the mock scanner. Introduce the sounds of various sequences (e.g., T1, fMRI) at gradually increasing volumes.

- Motion Training: Place a weighted blanket or bean bag on the child's forehead. Provide real-time feedback on head movement and practice correction.

- Practice Sessions: Conduct several practice runs, simulating the duration and sequence order of the actual scan protocol.

- In-Scan Procedures: During the actual MRI, use the weighted blanket and a simple incentive system (e.g., earning a reward for low motion) to reinforce behavior.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Reduction

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| MR-MinMo Device | A specialized head stabilizer that uses a frame with inflatable pads and a locking halo to minimize head motion during high-resolution scans [36]. |

| Audiovisual Distraction (AVD) System | MRI-safe video goggles or an in-bore projection system that displays movies to distract and calm the pediatric participant [10] [26]. |

| Mock MRI Scanner | A full-scale or small-scale replica of an MRI scanner used to acclimate children to the environment, sounds, and confinement of a real scan [37]. |

| Weighted Blanket | Used during mock and real scans to provide deep pressure touch, which has a calming effect and provides physical feedback about movement [37]. |

| Framewise Displacement (FFD) | A software metric calculated from fMRI data to quantify head motion; used as a primary outcome measure for motion reduction interventions [37]. |

Detailed Protocol 2: Implementing an Awake MRI Program with Audiovisual Distraction

This quality improvement framework outlines the steps for establishing a clinical service for scanning children without sedation [10].

- Primary Goal: To reduce the utilization of minimal/moderate sedation by at least 20% while maintaining diagnostic image quality.

- Materials: MRI-compatible AVD system (e.g., in-bore video projector), screening forms, trained multidisciplinary team (radiologists, technologists, sedation providers, child life specialists).

- Procedure (via PDSA Cycles):

- Planning: Convene a stakeholder group. Perform a retrospective review to establish baseline sedation rates.

- Targeting (Cycle 1): Install AVD technology. Develop an "awake MRI" workflow. Start with strict, low-risk inclusion criteria (e.g., children ≥7 years, head-first scans <60 minutes).

- Broadening Scope (Cycles 2 & 3): Successively broaden inclusion criteria to include any diagnosis and lower the age limit to 4 years, based on initial success.

- Optimization (Cycle 4): Implement a neuroradiology motion sensitivity score to guide sequence selection. Eliminate restrictions on scan duration.

- Reinforcement (Cycle 5): Install new AVD technology that allows scanning in any body position. Re-educate staff to reinforce the cultural shift towards awake MRI.

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

This technical support center resource is framed within a research thesis focused on reducing motion without sedation in pediatric imaging. For researchers and scientists, patient motion remains a primary confounder, degrading image quality and compromising data integrity. This guide details methodologies for implementing advanced acceleration technologies—Parallel Imaging (PI), Compressed Sensing (CS), and Deep Learning (DL) reconstruction—which are critical for shortening acquisition times to sub-minute durations and thereby mitigating motion artifacts in pediatric populations [38] [18]. The following sections provide foundational knowledge, troubleshooting guides for common experimental challenges, and detailed protocols for their application in a research setting.

Core Technical Foundations

The following table summarizes the key acceleration techniques, their operating principles, and relevance to motion reduction.

Table 1: Core Technical Foundations of Accelerated MRI

| Technique | Primary Operating Principle | Key Technical Parameters | Clinical Acceleration Factor | Relevance to Pediatric Motion Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Imaging (PI) [38] | Uses spatial information from multiple receiver coils to reconstruct undersampled data. | Acceleration Factor (R), Geometry Factor (g-factor). | R = 2 to 4 [38] | Directly reduces scan time, limiting the window for motion. Noise amplification (g-factor) can be limiting. |

| Compressed Sensing (CS) [38] [39] | Reconstructs images from randomly undersampled data by enforcing sparsity in a transform domain (e.g., wavelet). | Undersampling pattern, sparsity transform, regularization parameter (β). | R = 2.5 to 3 [38] | Random undersampling is key; allows for greater acceleration than PI alone but has long reconstruction times. |

| Deep Learning (DL) Reconstruction [38] [39] [22] | Learns a mapping from undersampled to fully-sampled data using neural networks trained on large datasets. | Network architecture (e.g., UNet), training loss function, amount of training data. | R = 4 to 8+ (in research) | Enables very high acceleration and near-instantaneous reconstruction; can be integrated with PI and CS. |

The logical integration of these techniques for maximizing motion robustness is depicted in the following workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Residual Aliasing Artifacts and Noise Amplification

Problem: Reconstructed images show significant noise or aliasing artifacts, often resembling overlapping ghosts or a "corduroy" pattern.

Investigation & Resolution:

Step 1: Check the Acceleration Factor (R).

- Symptoms: Severe noise that increases uniformly across the image.

- Cause: The overall acceleration factor (e.g., R = PI-factor × CS-factor) may be too high, leading to noise amplification characterized by a high g-factor in PI [38].

- Action: Systematically reduce the acceleration factor (R) in your protocol. For PI, clinical systems typically perform robustly at R = 2-4 [38].

Step 2: Verify the Sampling Pattern (for CS).

- Symptoms: Structured, coherent aliasing artifacts.

- Cause: The pseudo-random undersampling pattern used in CS may not be sufficiently "incoherent" relative to the sparsity transform [38].

- Action: Ensure the sampling mask uses a variable-density Poisson-disc or similar pattern that oversamples the low-frequency center of k-space.

Step 3: Calibrate Coil Sensitivity Maps (for PI).

- Symptoms: Aliasing artifacts localized to specific areas, often at the image periphery.

- Cause: Inaccurate estimation of coil sensitivity profiles used in SENSE-type reconstructions [38].

- Action: Ensure the auto-calibration scan is acquired with adequate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and is free of motion. Manually inspect the generated sensitivity maps for accuracy.

Guide 2: Managing Blurring and Loss of High-Frequency Detail

Problem: Reconstructed images appear overly smooth, lacking fine textural detail or having blurred edges.

Investigation & Resolution:

Step 1: Interrogate the DL Model.

- Symptoms: General loss of sharpness and texture; images may have a "painted" look.

- Cause: The deep learning model may be over-regularized or was trained on data that did not preserve high-frequency information. This is a known limitation of some CS algorithms without DL [38].

- Action: If using a commercially implemented DL tool (e.g., Deep Resolve [22]), adjust the "strength" or "sharpness" parameter if available. For custom models, review the training loss function and ensure it includes a term that preserves high-frequency details.

Step 2: Review CS Regularization Parameters.

- Symptoms: Images appear cartoon-like, with blocky or patchy areas.

- Cause: The regularization parameter (β) in the CS optimization is set too high, over-enforcing sparsity and suppressing fine details [38] [39].

- Action: In a research environment, gradually reduce the β parameter in the reconstruction algorithm and observe the output for a return of texture without introducing noise.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can these techniques be combined for greater acceleration? A1: Yes, they are highly synergistic. A common and powerful approach is to use PI for a moderate acceleration (e.g., R=2) and then apply CS or DL on top to achieve a higher net acceleration (e.g., R=4-6). Many state-of-the-art DL methods are unrolled networks that explicitly incorporate the data consistency steps of CS and the coil sensitivity information of PI [38] [39].

Q2: What are the key requirements for training a custom DL reconstruction model? A2: You need a large dataset of high-quality, fully-sampled k-space data as your ground truth. This is typically difficult to acquire clinically. A common workaround is to use publicly available datasets like fastMRI [38] [40]. The training requires significant computational resources (GPUs) and expertise in defining an appropriate loss function that balances artifact suppression with detail preservation [38].

Q3: How can I validate that an accelerated protocol is diagnostically reliable? A3: Beyond qualitative assessment, use quantitative metrics to compare against a fully-sampled reference. Common metrics include Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), and Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE) [38] [39]. For a clinical trial, a blinded review by radiologists to evaluate diagnostic confidence compared to a standard clinical scan is the gold standard [18].