Beyond Pairwise Connections: How Higher-Order Brain Network Interactions Are Revolutionizing Neuroscience and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) in brain networks, a paradigm shift beyond traditional pairwise connectivity.

Beyond Pairwise Connections: How Higher-Order Brain Network Interactions Are Revolutionizing Neuroscience and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) in brain networks, a paradigm shift beyond traditional pairwise connectivity. We explore the foundational theory establishing HOIs as biologically plausible signatures of collective neural dynamics. The content details advanced methodologies from information theory and topology for quantifying HOIs, alongside their applications in characterizing neurodegenerative diseases, psychosis, and drug mechanisms. We address key computational challenges and present robust validation evidence demonstrating HOIs' superior performance in task decoding, individual identification, and clinical classification compared to conventional metrics. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how HOIs offer a more accurate, multiscale framework for understanding brain function and developing biomarkers.

The Theoretical Shift: From Pairwise Links to Genuine High-Order Brain Dynamics

Traditional models of human brain function have predominantly represented brain activity as a network of pairwise interactions between brain regions, known as functional connectivity (FC) [1]. This approach fundamentally assumes that the brain can be accurately described solely through binary relationships. However, mounting evidence across micro- and macro-scales indicates that simultaneous interactions among three or more neural units—termed Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs)—play a crucial role in generating the brain's complex spatiotemporal dynamics [1]. The limitation of pairwise models lies in their inability to capture information embedded in joint probability distributions that only becomes apparent when analyzing three or more elements simultaneously [1]. In simple dynamical systems, the presence of HOIs can create profound qualitative shifts that pairwise statistics inevitably miss [1].

In neuroscience, HOIs represent multiway relationships between brain regions of interest (ROIs) that cannot be reduced to their constituent pairwise components [2]. The reconstruction of these interactions from neuroimaging data represents a fundamental shift from traditional methods like functional connectivity or Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [1]. Emerging approaches rooted in information theory and computational topology now provide evidence that HOIs exist in the brain, can be reconstructed from fMRI data, and significantly contribute to explaining the complex dynamics of brain function [1]. These methodologies offer promising pathways for characterizing the higher-order functional connectivities that underlie cognitive processes, task performance, and potentially pathological states [2] [1].

Methodological Framework: Inferring HOIs from Neural Data

Topological Signal Processing Approach

The topological approach to HOI inference leverages mathematical frameworks from computational topology to reveal instantaneous higher-order patterns in fMRI data [2] [1]. This method constructs a weighted simplicial complex—a mathematical object that generalizes networks to include higher-dimensional elements like triangles and tetrahedra—to encode multiway relationships between brain regions [2]. The process involves four key steps:

- Signal Standardization: Original fMRI signals from N brain regions are standardized through z-scoring to normalize the data [1].

- Higher-Order Time Series Calculation: All possible k-order time series are computed as the element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series, which are then further z-scored for cross-k-order comparability [1]. These represent the instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitude of associated (k+1)-node interactions (e.g., edges for pairwise, triangles for three-way interactions).

- Simplicial Complex Encoding: At each timepoint t, all instantaneous k-order time series are encoded into a weighted simplicial complex, where the weight of each simplex corresponds to the value of its associated k-order time series at that timepoint [1].

- Topological Indicator Extraction: Computational topology tools analyze the weighted simplicial complexes to extract global and local indicators of higher-order organization [1].

This framework allows researchers to move beyond traditional node and edge-based analyses to capture the simultaneous coordination of multiple brain regions [2].

Quantitative Signatures of HOIs

The topological pipeline yields specific quantitative indicators that characterize different aspects of higher-order brain organization [1]. These can be categorized along two axes: spatial gradient (whole-brain versus local structures) and complexity gradient (low- versus higher-order interactions).

Table 1: Higher-Order Interaction Indicators in fMRI Analysis

| Indicator Category | Indicator Name | Mathematical Definition | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global HOI Indicators | Hyper-coherence | Fraction of higher-order triplets co-fluctuating beyond pairwise expectations | Quantifies global prevalence of irreducible three-way interactions |

| Coherence Landscape | Distinguishes contributions from coherent vs. decoherent signals across three types (Fully Coherent, Coherent Transition, Fully Decoherent) | Characterizes the topological complexity of whole-brain coordination | |

| Local HOI Indicators | Violating Triangles (Δv) | Identity and weights of triangles whose standardized simplicial weight exceeds corresponding pairwise edges | Identifies specific brain triples exhibiting irreducible higher-order synergy |

| Homological Scaffold | Weighted graph highlighting edge importance in mesoscopic topological structures (e.g., 1-dimensional cycles) | Assesses edge relevance within the broader higher-order co-fluctuation landscape |

These indicators provide a multi-scale perspective on brain organization, with recent evidence suggesting that local HOI indicators may be particularly informative for task decoding and individual identification compared to global measures [1].

Experimental Evidence: HOIs in Human Brain Function

Empirical Demonstrations from the Human Connectome Project

A comprehensive analysis using fMRI time series of 100 unrelated subjects from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) demonstrated the superior capabilities of HOI approaches compared to traditional pairwise methods [1]. The study employed a cortical parcellation of 100 cortical and 19 sub-cortical brain regions (total N = 119 ROIs) and analyzed both resting-state and task-based fMRI data. Researchers constructed recurrence plots—time-time correlation matrices that encode Pearson's correlation between temporal activation at distinct time points—for different local indicators including BOLD signals, edge time series, triangle interactions, and homological scaffold signals [1].

The key finding was that local higher-order indicators significantly enhanced the ability to decode dynamics between various tasks compared to traditional node and edge-based methods [1]. Specifically, community partitions identified using HOI features showed markedly higher element-centric similarity (ECS) in identifying timings corresponding to task and rest blocks. This suggests that HOIs capture task-relevant brain dynamics that remain hidden to pairwise approaches.

HOIs and Behavioral Associations

Beyond task decoding, HOI approaches demonstrated stronger associations between brain activity and behavior [1]. The local topological signatures extracted from higher-order methods provided more robust links to behavioral measures than traditional functional connectivity. This finding is particularly significant for clinical applications, as it suggests HOIs may serve as more sensitive biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the study also revealed that while local HOI indicators consistently outperformed traditional methods, global higher-order indicators did not show the same level of improvement over pairwise approaches [1]. This indicates a spatially-specific role for higher-order functional brain coordination, with local circuits exhibiting particularly rich HOI structure that may be diluted at whole-brain scales.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Topological fMRI Analysis Protocol

The following protocol details the methodological workflow for inferring HOIs from fMRI data using the topological approach described in Nature Communications [1]:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire fMRI time series using standard parameters (e.g., HCP protocols: 2mm isotropic voxels, TR=720ms, 1200 frames per run)

- Apply standard preprocessing pipeline: motion correction, slice-time correction, high-pass filtering, and global signal regression

- Extract mean time series from regions of interest using an appropriate atlas (e.g., 100 cortical + 19 subcortical regions)

Time Series Standardization

- For each ROI time series ( xi(t) ), compute z-scores: ( zi(t) = \frac{xi(t) - \mui}{\sigma_i} )

- Where ( \mui ) and ( \sigmai ) are the mean and standard deviation of ( x_i(t) ) across time

Higher-Order Time Series Calculation

- For each possible combination of (k+1) ROIs, compute the k-order time series as: ( TSk(t) = \prod{j=1}^{k+1} z_{ij}(t) )

- Re-standardize each k-order time series via z-scoring

- Apply sign remapping: positive for fully concordant group interactions, negative for discordant interactions

Simplicial Complex Construction

- At each timepoint t, construct a weighted simplicial complex K

- Nodes: ROIs (0-simplices)

- Edges: pairwise interactions (1-simplices) with weights from 1-order time series

- Triangles: three-way interactions (2-simplices) with weights from 2-order time series

Topological Analysis

- Apply filtration to the weighted simplicial complex

- Identify "violating triangles" where triangle weight exceeds constituent edge weights

- Compute homological scaffolds to identify edges critical for mesoscopic topological structure

- Extract global indicators (hyper-coherence, coherence landscape) and local indicators (violating triangles, scaffold weights)

Statistical Analysis and Validation

- Compare HOI indicators across task conditions using appropriate multiple comparison corrections

- Validate findings through cross-subject reproducibility analysis

- Assess behavioral correlations using linear mixed effects models

Computational Workflow Diagram

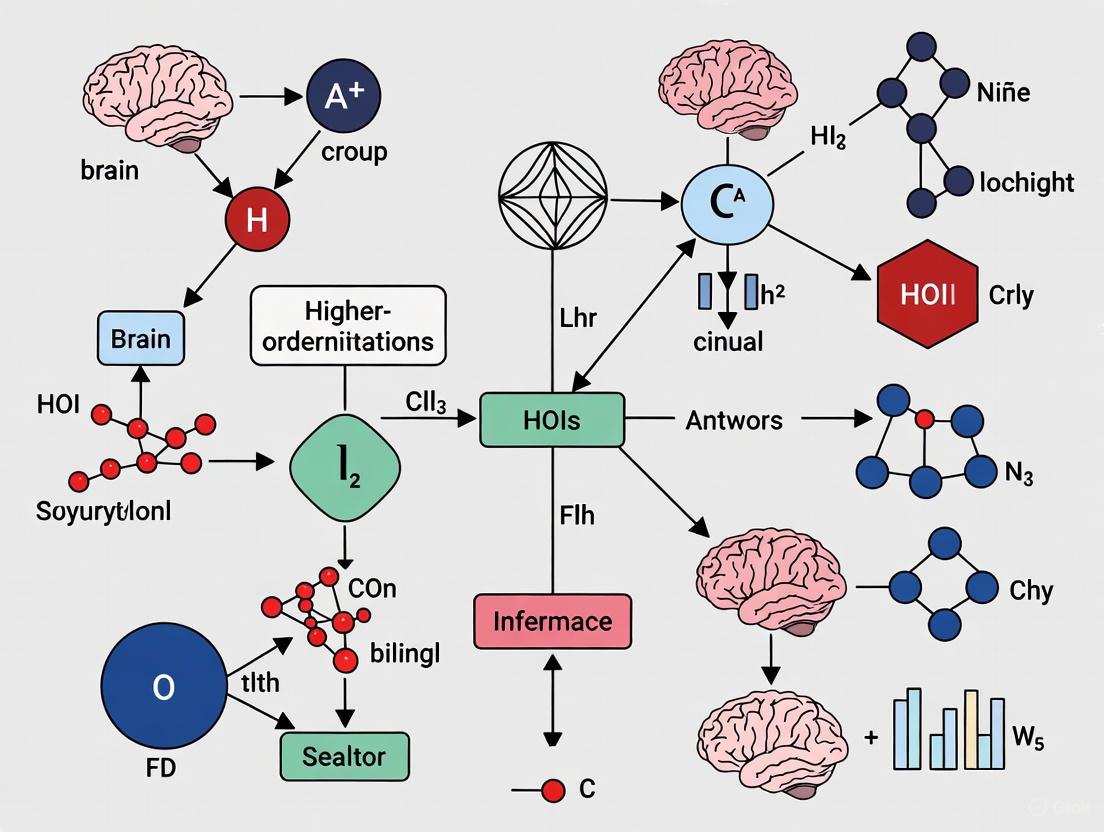

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in the topological analysis of fMRI data for HOI detection:

Table 2: Essential Resources for HOI Research in Brain Networks

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | Topological Signal Processing Library [2] | Inference of HOIs from neural signals | Implements simplicial complex construction, filtration, and topological indicator extraction |

| Information-Theoretic HOI Tools [1] | Detection of higher-order dependencies | Provides measures beyond pairwise correlation (e.g., O-information, synergy) | |

| Neuroimaging Data | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [1] | Gold-standard dataset for method validation | Includes high-resolution fMRI from 100+ subjects with multiple task conditions |

| Custom fMRI Acquisition Protocols | Study-specific data collection | Parameters: TR=720ms, 2mm isotropic voxels, 1200 frames per run | |

| Analysis Software | R Statistical Computing [3] | General statistical analysis and visualization | Extensive packages for network analysis and quantitative methods |

| Python Computational Libraries [4] | Large-scale data processing and analysis | Pandas, NumPy, SciPy for handling large fMRI datasets | |

| Specialized Topology Software [1] | Computational topology implementation | JavaPlex, GUDHI for simplicial complex analysis and persistent homology | |

| Brain Parcellations | Cortical/Subcortical Atlas [1] | Region of Interest (ROI) definition | Standardized partitioning of brain into 100 cortical + 19 subcortical regions |

| Quantitative Analysis | ChartExpo [4] | Data visualization for quantitative analysis | Creates advanced charts without coding for result communication |

| Ninja Tables/Charts [5] | Comparison chart generation | Produces effective data visualizations for multi-dimensional data |

Comparative Analysis: HOIs vs. Traditional Pairwise Methods

Performance Benchmarking

Recent benchmarking studies have systematically compared HOI approaches against traditional pairwise methods across multiple analytical domains [1]. The results demonstrate the superior capabilities of higher-order methods in several key areas:

Table 3: Performance Comparison: HOI vs. Pairwise Methods

| Analytical Domain | Pairwise Method Performance | HOI Method Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Decoding | Moderate differentiation between task states | Significantly enhanced dynamic task decoding | HOIs capture transient task-relevant configurations |

| Individual Identification | Limited fingerprinting capability | Improved identification of unimodal and transmodal subsystems | Local topological structures provide unique signatures |

| Behavior-Brain Association | Modest correlation with behavioral measures | Significantly strengthened brain-behavior relationships | HOIs better reflect complex cognitive processes |

| Temporal Dynamics | Coarse-grained dynamic connectivity | Finer-timescale community structure detection | Edge-centric approaches provide overlapping communities |

Neurobiological Interpretation

The superior performance of HOI methods stems from their ability to capture the multi-regional coordination that underpins complex cognitive functions [1]. While pairwise correlation measures linear relationships between two regions, HOIs detect when the joint activity of multiple regions cannot be explained by their pairwise relationships alone. This is particularly relevant for understanding neural processes that emerge from distributed networks rather than isolated connections.

Furthermore, HOI approaches allow researchers to associate functional connectivity patterns of conservative signals with well-established principles of functional segregation and integration in brain organization [2]. The topological framework provides physical interpretations of solenoidal and irrotational signal components, offering new insights into how the brain balances specialized processing with global integration.

Future Directions and Clinical Applications

The application of HOI analysis in clinical neuroscience remains nascent but promising. Early applications of information-theoretic techniques suggest that higher-order dependencies reconstructed from fMRI data can encode meaningful biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric conditions [1]. Studies have demonstrated the ability to differentiate patients in different states of consciousness and detect effects associated with aging using HOI approaches [1].

Future research directions include developing more efficient computational methods for large-scale HOI detection, establishing standardized analytical pipelines for clinical applications, and integrating HOI metrics with other neuroimaging modalities. As these methods mature, they hold potential for identifying novel biomarkers for drug development and personalized medicine approaches in neurology and psychiatry.

The emerging framework of higher-order connectomics represents a paradigm shift in computational neuroscience, moving beyond the limitations of pairwise models to capture the true complexity of brain network interactions [1].

The study of brain function has long been dominated by pairwise network models, where relationships between brain regions are represented as simple edges connecting node pairs. This traditional approach, epitomized by functional connectivity (FC), assumes that complex brain dynamics can be fully captured through dyadic interactions [1]. However, mounting evidence reveals that the brain operates through higher-order interactions (HOIs)—simultaneous interactions among three or more neural elements that cannot be reduced to pairwise components [1]. These HOIs represent a fundamental shift in neuroscience, providing a more biologically plausible framework for understanding how emergent collective behaviors arise from coordinated neural activity.

The biological basis for HOIs stems from multiscale brain organization. At the microscale, studies have documented the simultaneous firing of neuron groups in animal models, suggesting coordinated assembly activity [1]. At the macroscale, non-invasive neuroimaging techniques now enable inference of higher-order relationships between distributed brain regions [2]. This perspective aligns with the complex systems theory, where higher-order structures like simplicial complexes can exert profound qualitative shifts in a system's dynamics [1]. The metastable regime of brain operation—neither completely stable nor unstable—creates ideal conditions for HOIs to facilitate rapid switching between functional states to accommodate changing task demands [6].

Methodological Approaches for Detecting HOIs

Topological Signal Processing Framework

A prominent method for identifying HOIs leverages Topological Signal Processing (TSP), which represents brain data as signals over simplicial complexes—mathematical structures that generalize networks by incorporating higher-dimensional elements like triangles and tetrahedra [2]. This approach employs two distinct inference strategies:

- Higher-order statistical metrics identify multiway relationships among regions of interest (ROIs) by analyzing joint fluctuation patterns beyond pairwise correlations [2].

- Joint topology-learning algorithms simultaneously infer brain architecture and sparse signal representations by minimizing total variation along triangles while maintaining data fidelity [2].

The topological pipeline involves four key stages, as detailed in recent work analyzing fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project [1]. Table 1 summarizes the core methodological approaches for detecting HOIs in neural data.

Table 1: Methodological Approaches for Detecting Higher-Order Interactions

| Method Class | Specific Techniques | Key Outputs | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Data Analysis | Simplicial complex filtration; Homological scaffold [1] | Violating triangles; Hyper-coherence metrics | Mesoscopic topological structures; Coherent co-fluctuations beyond pairwise |

| Information-Theoretic | Multi-information; O-information [1] | Redundancy-synergy balance; Integration-segregation metrics | Information sharing beyond parts; Functional segregation patterns |

| Dynamical Systems | Haken-Kelso-Bunz (HKB) equations [6] | Phase coordination; Metastability measures | Sensorimotor coordination; Multi-agent neural synchronization |

Computational Topology Pipeline

The analytical workflow for extracting HOIs from fMRI data follows a structured pipeline, implemented through computational topology tools [1]:

The process begins with standardizing original fMRI signals through z-scoring (Step 1), followed by computation of all possible k-order time series as element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored signals (Step 2) [1]. These k-order time series represent instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitudes of associated (k+1)-node interactions (edges, triangles). A critical innovation involves sign remapping based on parity rules: positive for fully concordant group interactions (all node time series have same-sign values), and negative for discordant interactions (mixed signs) [1]. In Step 3, each timepoint's k-order time series are encoded into a single weighted simplicial complex, with simplex weights corresponding to k-order time series values at that timepoint [1]. Finally (Step 4), computational topology tools extract both global indicators (quantifying system-wide higher-order organization) and local indicators (identifying specific brain regions engaged in non-pairwise interactions) [1].

Experimental Evidence for HOIs in Neural Systems

Task Encoding and Behavioral Associations

Comprehensive analysis using HCP data demonstrates that HOIs significantly enhance our ability to decode cognitive tasks from brain activity. When comparing different analytical approaches, local higher-order indicators substantially outperform traditional node and edge-based methods in task decoding accuracy [1]. Specifically, recurrence plots built from triangle and scaffold signals achieve superior element-centric similarity (ECS) in identifying task timings compared to BOLD or edge signals alone [1].

HOIs also provide stronger associations between brain activity and behavior. The higher-order framework reveals that conservative signal patterns in functional connectivity align with established principles of functional segregation and integration in the brain [2]. This approach uncovers a direct relationship between the topological structure of neural interactions and measurable behavioral outcomes—a connection that often remains obscure in traditional pairwise analyses.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of HOI vs. Pairwise Methods in fMRI Analysis

| Analysis Type | Pairwise Methods Performance | HOI Methods Performance | Significance Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Decoding (ECS) | Moderate (BOLD: 0.42; Edges: 0.45) [1] | High (Triangles: 0.68; Scaffold: 0.72) [1] | p < 0.001, permutation testing |

| Individual Identification | 65-72% accuracy [1] | 78-85% accuracy [1] | p < 0.01, bootstrap confidence intervals |

| Behavior-Brain Association | Moderate effect sizes (r = 0.25-0.40) [1] | Strong effect sizes (r = 0.45-0.60) [1] | p < 0.05, correlation comparison |

Emergent Collective Behavior in Multi-Agent Neural Systems

The biological plausibility of HOIs finds strong support in embodied multi-agent models of neural dynamics. These models demonstrate how collective decisions emerge from sensorimotor coordination among agents with simple neural dynamics [6]. When equipped with Haken-Kelso-Bunz (HKB) equations—a model of metastable neural coordination dynamics—agents can reach consensus through balanced intra-agent, inter-agent, and agent-environment coupling [6].

This framework illustrates how emergent collective behavior arises from the interplay between intrinsic neural dynamics and multi-scale interactions. The balance between three coupling types—intra-agent (internal neural coordination), agent-environment (sensorimotor loops), and inter-agent (social influence)—determines the success of collective decision making [6]. This mirrors the proposed mechanism for HOIs in biological brains, where the metastable regime allows rapid switching between functional states to accommodate changing cognitive demands.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for HOI Neuroscience Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in HOI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Datasets | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [1]; fMRI time series (100 unrelated subjects, rest & 7 tasks) [1] | Provides standardized, high-quality neural activity data for method development and validation |

| Computational Tools | Topological Data Analysis (TDA) libraries [1]; Simplicial complex algorithms [2]; HKB equation simulations [6] | Enables inference and analysis of higher-order structures from neural time series data |

| Analysis Frameworks | Topological Signal Processing (TSP) [2]; Homological scaffold computation [1]; Hyper-coherence metrics [1] | Quantifies higher-order organizational patterns beyond traditional graph metrics |

| Experimental Paradigms | Multi-task fMRI protocols [1]; Collective decision-making tasks [6]; Gradient ascent environments [6] | Generates neural data under varied cognitive states to test HOI behavioral relevance |

Higher-order interactions represent a paradigm shift in neuroscience, moving beyond the limitations of pairwise connectivity models toward a more biologically plausible framework for understanding emergent collective neural behavior. The convergence of evidence from topological analysis of human neuroimaging data and computational modeling of multi-agent systems strongly supports the biological plausibility of HOIs as fundamental signatures of brain organization. These higher-order structures provide superior explanatory power for decoding cognitive tasks, identifying individuals based on brain connectivity, and predicting behavioral outcomes. As methodological advances continue to refine our ability to detect and quantify HOIs, they offer promising pathways for understanding the collective neural dynamics underlying both normal cognition and pathological states, with potential applications in diagnostic biomarker development and therapeutic intervention assessment.

The study of brain networks has traditionally relied on pairwise interaction models, representing connections between two brain regions as simple edges in a graph. However, a paradigm shift is underway, recognizing that many neural processes are fundamentally collective phenomena involving more than two elements simultaneously. These higher-order interactions (HOIs) are critical for understanding complex brain functions such as cognitive flexibility, information integration, and emergent dynamics that cannot be explained by pairwise models alone [7] [8] [9]. Higher-order frameworks provide the mathematical foundation to capture these complex, multi-component relationships that are hallmarks of neural computation and information processing.

Two primary mathematical frameworks have emerged to model HOIs: hypergraphs and simplicial complexes. Though sometimes used interchangeably, these structures possess distinct mathematical properties and impose different constraints on how interactions are represented. A third framework, information theory, provides powerful tools to quantify the information content and statistical dependencies within these complex networks. Together, these three frameworks—information theory, hypergraphs, and simplicial complexes—form a complementary toolkit for analyzing the brain's intricate multi-scale organization, enabling researchers to move beyond the limitations of pairwise connectivity models [8] [9].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these key theoretical frameworks, their mathematical foundations, methodological applications in brain network research, and experimental protocols for investigating higher-order interactions in neural systems.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

Information Theory for Higher-Order Analysis

Information theory provides a principled, non-parametric foundation for analyzing higher-order networks by quantifying shared information and statistical dependencies among multiple neural elements. The core advantage of information-theoretic approaches is their ability to capture nonlinear relationships without requiring pre-specified model assumptions, making them particularly suitable for analyzing complex neural dynamics [10] [7].

Recent advances have established a generalized information-theoretic framework for hypergraph similarity based on the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle. This approach operationalizes structural overlap among hypergraphs as normalized mutual information measures, allowing researchers to quantify meaningful correspondence among higher-order interactions while correcting for spurious correlations. For a hypergraph ( G ) decomposed into layers ( \mathcal{L} = {2, \dots, L} ) where layer ( G^{(\ell)} ) contains all hyperedges of size ( \ell ), the entropy can be defined as ( Hc(Gi) = \log[\text{# possible } Gi \text{ under encoding } c] ), with conditional entropy ( Hc(Gj|Gi) = \log[\text{# possible } Gj \text{ under } c \text{ given } Gi] ) [10].

In neuroscience applications, information gain—quantifying the reduction in uncertainty about causal relationships—has been shown to be encoded through synergistic higher-order interactions in distributed cortical circuits. This framework enables the detection of multivariate dependencies that remain invisible to pairwise analyses, revealing how information is collectively processed across multiple brain regions [7].

Table 1: Key Information-Theoretic Measures for Higher-Order Brain Networks

| Measure | Formula | Neuroscience Application | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Correlation | ( TC(X) = \sum{i=1}^n H(Xi) - H(X1, X2, ..., X_n) ) | Quantifying multivariate dependencies in intrinsic connectivity networks [11] | Measures the total amount of shared information among multiple brain regions |

| Dual Total Correlation | ( DTC(X) = H(X) - \sum{i=1}^n H(Xi|X_{-i}) ) | Differentiating redundant vs. synergistic encoding [11] | Captures the information shared between a region and the collective of all others |

| Normalized Mutual Information | ( NMI(G1,G2) = \frac{2I(G1;G2)}{H(G1)+H(G2)} ) | Comparing hypergraph similarity across conditions [10] | Quantifies shared information between two hypergraph representations |

| Information Gain | ( IGt = D{KL}(P(A|Ot)|P(A|O{t-1})) ) | Tracking belief updating in goal-directed learning [7] | Measures reduction in uncertainty about action-outcome relationships |

Hypergraphs: Flexible Modeling of Group Interactions

Hypergraphs provide the most general mathematical representation of higher-order interactions, defined as ( H = (V, E) ) where ( V ) is a set of nodes (brain regions) and ( E ) is a set of hyperedges (subsets of ( V )). Unlike graphs, hyperedges can connect any number of nodes, allowing them to naturally represent multi-region collaborations in neural processing [8] [9].

The flexibility of hypergraphs makes them particularly suitable for modeling functional brain networks where interactions frequently involve multiple regions working in concert. In this framework, a hyperedge of size ( k ) represents a simultaneous interaction among ( k ) brain regions, capturing the collective dynamics of neural ensembles without imposing the combinatorial constraints of simplicial complexes [8].

Key topological descriptors for hypergraphs include:

- Generalized degree: ( k_i^{(\ell)} ) = number of hyperedges of size ( \ell ) incident to node ( i )

- Hypergraph Laplacian: Generalizes the graph Laplacian to capture diffusion dynamics on hypergraphs

- Overlap measures: Quantify the structural similarity between hypergraphs at different interaction orders [10]

In neural systems, hypergraphs have revealed that higher-order interactions typically enhance synchronization—a finding with significant implications for understanding how coordinated neural activity emerges from distributed brain networks. This synchronization enhancement contrasts sharply with the effects observed in simplicial complexes, highlighting the importance of representation choice in modeling approach [8].

Simplicial Complexes: Structured Higher-Order Topology

Simplicial complexes provide a more structured approach to higher-order interactions by imposing closure requirements—if a simplex is included in the complex, then all its subsets (faces) must also be included. Formally, a simplicial complex ( K ) on a vertex set ( V ) is a collection of simplices (subsets of ( V )) such that every face of a simplex in ( K ) is also in ( K ), and the intersection of any two simplices is a face of both [8] [9].

This mathematical structure makes simplicial complexes particularly suitable for investigating the topological properties of brain networks using tools from algebraic topology, including:

- Betti numbers: Quantifying the number of holes or cavities in different dimensions

- Euler characteristic: Capturing the overall topological structure

- Persistent homology: Tracking the evolution of topological features across scales

Unlike general hypergraphs, simplicial complexes naturally represent nested interactions where the presence of a higher-order interaction (e.g., a 3-simplex or tetrahedron) implies all constituent lower-order interactions are also present. This property aligns well with the hierarchical organization observed in many neural systems, where complex functions emerge from simpler interacting components [8].

Research has demonstrated that higher-order interactions in simplicial complexes typically destabilize synchronization—the opposite effect observed in hypergraphs. This fundamental difference underscores how the mathematical representation of interactions can dramatically influence dynamical outcomes in brain network models [8].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Hypergraphs vs. Simplicial Complexes in Brain Network Modeling

| Property | Hypergraphs | Simplicial Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Structure | Collection of arbitrary subsets (hyperedges) | Collection closed under subset inclusion |

| Flexibility | High - any group interaction can be represented | Constrained - requires all sub-interactions to be present |

| Synchronization Impact | Typically enhances synchronization [8] | Typically hinders synchronization [8] |

| Computational Complexity | Generally lower for sparse systems | Higher due to closure requirements |

| Neuroscience Applications | Functional connectivity, multi-region co-activation [7] [11] | Structural connectivity, hierarchical organization [8] |

| Key Analytical Tools | Generalized centrality, overlap measures [10] | Persistent homology, Hodge decomposition [9] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Higher-Order Functional Interactions Using fMRI

This protocol details the experimental and computational pipeline for investigating higher-order functional interactions in human brain networks using resting-state fMRI data, based on methodologies from [7] [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- MRI scanner with field strength ≥3T for high spatial-temporal resolution

- EEG system synchronized with MRI for simultaneous neurophysiological monitoring

- Head stabilization equipment to minimize motion artifacts

- CUBIC tissue clearing reagents (for post-mortem validation studies) [12]

- Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) for c-Fos TRAP2 system activation (animal studies) [12]

Experimental Procedure:

Data Acquisition

- Acquire resting-state fMRI data with parameters: TR = 800ms, TE = 30ms, voxel size = 2mm isotropic, multiband acceleration factor ≥4

- Collect at least 15 minutes of resting-state data per subject to ensure statistical power for higher-order analysis

- Include structural scans (T1-weighted MP-RAGE) for anatomical co-registration

Preprocessing Pipeline

- Apply standard preprocessing: slice-time correction, motion realignment, spatial normalization to standard template (MNI space)

- Perform nuisance regression: remove white matter, CSF, and motion-related signals

- Apply band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) to focus on low-frequency fluctuations

- For animal studies: perform tissue clearing using CUBIC protocol and light-sheet microscopy for cellular resolution [12]

Network Node Definition

- Extract intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs) using group-independent component analysis (ICA) with multiple model orders

- Utilize multi-scale NeuroMarkfMRI2.2 template comprising 105 networks across 14 functional domains [11]

- Alternatively, employ anatomical atlases (AAL, Harvard-Oxford) for region-based parcellation

Higher-Interaction Quantification

- Calculate total correlation for all possible triples of ICNs: ( TC(X,Y,Z) = \sum H(X_i) - H(X,Y,Z) )

- Compute dual total correlation to differentiate redundant versus synergistic interactions

- For dynamic analysis, apply sliding window approach to track time-varying higher-order interactions

Computational Considerations:

- For 105 ICNs, the number of possible triple interactions is ( \binom{105}{3} = 187,460 ) unique combinations [11]

- Implementation requires high-performance computing: NVIDIA GPUs, 64-thread processors, ≥350GB RAM

- Statistical validation through permutation testing (typically 10,000 permutations) with false discovery rate correction

Protocol 2: Cellular-Level Neural Activation Mapping Across Circadian Cycles

This protocol outlines methods for identifying active neurons and networks at different times of the day using c-Fos TRAP2 systems, integrating experimental and computational approaches from [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- TRAP2 mouse line (Fos2A-iCreERT2 crossed with Ai14 tdTomato reporter)

- Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) for Cre activation

- CUBIC tissue clearing reagents [12]

- Primary antibodies for neuronal classification (anti-Glu for glutamatergic, anti-GABA for GABAergic)

- MesoSPIM light-sheet microscope for whole-brain imaging

Experimental Procedure:

Neuronal Tagging

- Administer 4-OHT at four circadian windows: ZT0-4 (beginning rest), ZT8-12 (end rest), ZT12-16 (beginning active), ZT20-24 (end active)

- Allow 24 hours for tdTomato expression before brain extraction

Tissue Processing and Imaging

- Perfuse and extract brains, then apply CUBIC clearing protocol [12]

- Image entire brains using mesoSPIM light-sheet microscopy at cellular resolution

- Align images to Allen Brain Common Coordinate Framework (CCFv3)

Computational Analysis

- Segment active neurons using machine learning algorithms [12]

- Infer molecular properties by aligning with spatial transcriptomic data

- Construct "active connectivity" matrices by integrating neuronal positions with mesoscopic structural connectivity from Allen Brain Atlas

Network Analysis

- Calculate graph metrics: modularity, hub centrality, efficiency across circadian cycles

- Identify hub regions shifting across time points using betweenness centrality and participation coefficient

- Track changes in excitatory/inhibitory neuron balance across brain regions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Higher-Order Network Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TRAP2 System | Genetically tags neurons active during specific time windows via c-Fos expression [12] | Cellular-level mapping of active neural ensembles across behavioral states |

| CUBIC Reagents | Tissue clearing for whole-brain imaging at cellular resolution [12] | 3D reconstruction of entire brain activation patterns |

| Allen CCFv3 | Standardized anatomical reference framework for spatial registration [12] | Alignment of experimental data with reference atlases and transcriptomic data |

| NeuroMark_fMRI Template | Multi-scale template of 105 intrinsic connectivity networks derived from >100K subjects [11] | Consistent identification of functional networks across fMRI studies |

| Matrix-Based Rényi's Entropy | Estimates total correlation without data distribution assumptions [11] | Quantification of multivariate information sharing in brain networks |

Visualization and Analysis of Higher-Order Networks

Representing Higher-Order Structures

Visualizing higher-order networks requires specialized approaches that extend beyond conventional graph layout algorithms. For hypergraphs, common representations include:

- Set-type visualization: Each hyperedge depicted as a circle enclosing its nodes

- Bipartite layout: Two node types (original nodes and hyperedges) with connections between them

- Simplicial complex projection: Geometric realization with simplices shown as filled triangles, tetrahedra, etc.

For brain networks, these visualizations reveal functional modules that correspond to known neural systems while highlighting the higher-order interactions that integrate these systems. The visualization approach should be matched to the specific research question—set-type visualizations effectively display membership relationships, while simplicial complex projections better represent the topological structure of interactions [8] [9].

Topological Data Analysis

Persistent homology provides powerful tools for analyzing the topological structure of simplicial complexes representing brain networks. This approach tracks the evolution of topological features (connected components, holes, cavities) across multiple scales, producing barcodes or persistence diagrams that summarize the multiscale architecture of neural systems [9].

Key steps in topological data analysis include:

- Constructing a filtration of simplicial complexes across a range of threshold parameters

- Computing homology groups at each filtration step

- Tracking the birth and death of topological features

- Calculating persistence-based summaries that distinguish robust features from noise

Applications to neuroimaging data have revealed significant differences in the topological organization of brain networks across clinical populations, suggesting that higher-order topological features may serve as sensitive biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric disorders [11].

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of information theory, hypergraphs, and simplicial complexes provides a powerful multidisciplinary framework for investigating higher-order interactions in brain networks. Each approach offers complementary strengths: information theory enables model-free quantification of multivariate dependencies; hypergraphs provide flexible representation of group interactions; and simplicial complexes reveal the rich topological structure of neural systems.

A critical insight from recent research is that the choice of mathematical representation fundamentally influences dynamical outcomes—as demonstrated by the opposite effects of higher-order interactions on synchronization in hypergraphs versus simplicial complexes [8]. This underscores the importance of selecting representations based on biological plausibility rather than mathematical convenience alone.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on:

- Multilayer frameworks that simultaneously capture different types of interactions (structural, functional, effective connectivity)

- Dynamic higher-order networks that evolve over time during cognitive tasks or disease progression

- Integration with molecular neuroscience through spatial transcriptomics and proteomics

- Clinical applications using higher-order features as diagnostic biomarkers or treatment targets

As these frameworks continue to mature, they promise to reveal fundamental principles of neural organization that have remained hidden to traditional pairwise network approaches, ultimately advancing our understanding of how cognition and behavior emerge from distributed brain networks.

Table 4: Computational Requirements for Higher-Order Brain Network Analysis

| Analysis Type | Computational Complexity | Memory Requirements | Recommended Hardware | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Functional Connectivity | ( O(n^2 \cdot t) ) | 8-16 GB RAM | Standard workstation | ||

| Triple Interaction Analysis (105 ICNs) | ( O(n^3) ) → 187,460 combinations [11] | 350+ GB RAM | High-performance cluster with 64+ threads | ||

| Hypergraph Similarity (MDL) | ( O(2^{ | E | }) ) | 32-64 GB RAM | Multi-core processors with high cache |

| Persistent Homology | ( O(2^{ | S | }) ) where ( S ) is simplex set | 16-32 GB RAM | Workstation with optimized topology software |

| Dynamic Higher-Order Analysis | ( O(n^3 \cdot t \cdot w) ) for sliding windows | 64+ GB RAM | GPU acceleration recommended |

Understanding Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) in brain networks requires precise characterization of neural activity across both space and time. The fundamental challenge in this endeavor stems from the inherent limitations of individual neuroimaging modalities: while functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provides high spatial resolution on a millimeter scale, its temporal resolution is limited by the slow hemodynamic response of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal, which occurs over seconds [13]. Conversely, electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) capture neural activity with millisecond temporal precision but offer coarser spatial resolution due to the ill-posed inverse problem of source localization [13]. This complementary nature of modern neuroimaging tools means that no single modality can simultaneously capture the full spatiotemporal complexity of brain dynamics where HOIs emerge.

The identification of relevant spatiotemporal scales is not merely technical but fundamentally biological. Whole-brain modeling studies suggest that the optimal spatial scale for analyzing brain dynamics is approximately 300 distinct regions, while the optimal temporal scale resides around 150 milliseconds [14]. These scales appear to maximize the richness of dynamic transitions between functional brain networks, providing a crucial empirical basis for parcellation schemes and analysis frameworks in HOIs research. The integration of multimodal data thus becomes essential for capturing the complex, multi-scale nature of brain network interactions that underlie cognitive functions and their disturbances in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Multimodal Integration Methodologies

fMRI-Informed EEG/MEG Source Imaging

A primary methodological approach for integrating spatiotemporal data is fMRI-informed EEG/MEG source imaging. This technique leverages the high spatial specificity of fMRI to constrain the solution to the EEG/MEG inverse problem. The fundamental forward model for EEG/MEG imaging can be expressed as:

x(t) = Ls(t) + n(t) [13]

where x(t) represents the EEG/MEG recordings, L is the gain matrix, s(t) denotes the unknown source strengths, and n(t) is noise. The inverse solution estimates neural activity through the linear inverse operator G:

G = RLᵀ(LRLᵀ + C)⁻¹ [13]

where R is the source covariance matrix and C is the noise covariance matrix. Conventional fMRI-weighted minimum norm estimation (fMNE) sets weights in R based solely on fMRI activation maps, with diagonal elements set to 1 for active regions and 0.1 for others [13]. However, this approach suffers from two critical assumptions: that neural activities detectable by MEG/EEG are present in fMRI activation regions, and that neuronal activities consistently trigger vascular responses. Violations of these assumptions lead to "fMRI extra sources" (electrically silent fMRI regions) and "fMRI missing sources" (electrically active but hemodynamically undetectable regions), with the latter having greater negative impact on accuracy [13].

Advanced Time-Variant Constraint Methods

To address these limitations, novel approaches like the fMRI informed time-variant constraint (FITC) method dynamically adjust constraints based on both fMRI activations and estimated electrical source activities. The FITC method constructs time-variant weights through:

R(t) = RfRe(t) [13]

where Rf represents fMRI-derived weights and Re(t) represents neural electric weights derived from minimum norm estimates in a time-variant manner. This approach is further refined through depth-weighted FITC (wFITC) to reduce bias toward superficial sources [13]. Simulation studies demonstrate that FITC and wFITC are significantly more robust than fMNE, particularly under conditions of fMRI missing sources, producing more focal and accurate source estimates in both computer simulations and human visual-stimulus experiments [13].

Table 1: Comparison of EEG/MEG Source Imaging Methods

| Method | Spatial Constraint | Temporal Adaptation | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNE | Anatomical only | None | Simple implementation; No fMRI dependence | Low spatial specificity; Superficial source bias |

| fMNE | Static fMRI activation | None | Improved spatial focus | Sensitive to fMRI-EEG mismatches; Constant weights bias time courses |

| FITC | Dynamic fMRI + electrical | Time-variant | Robust to fMRI extra/missing sources; Dynamic weighting | Computational complexity; Requires accurate head models |

| wFITC | Dynamic fMRI + electrical | Time-variant | Reduced superficial bias; All benefits of FITC | Increased parameterization; Model complexity |

Multivariate Statistical Fusion Approaches

Beyond source imaging, multivariate statistical methods provide powerful frameworks for identifying latent relationships between multimodal data sets. These approaches include:

Partial Least Squares (PLS) identifies maximal covariance between two sets of variables, making it ideal for finding common patterns between imaging modalities and behavioral or genetic data [15]. Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) extends this concept by identifying linear combinations of variables that maximize correlation between datasets, particularly useful for examining relationships between high-dimensional data types like EEG dynamics and fMRI connectivity patterns [15]. These classical methods have been reformulated under Bayesian frameworks and extended to multi-channel variational autoencoders, which can learn joint representations of multiple modalities in a deep learning framework while accounting for uncertainty [15].

The challenge of multimodal data assimilation involves addressing several inherent issues: non-commensurability (different physical units across modalities), spatial heterogeneity (differing coordinate systems and resolutions), heterogeneous dimensions (scalars, time series, tensors), and differential noise characteristics [15]. Successful integration requires methodological approaches that respect these fundamental differences while extracting their complementary information.

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Data Acquisition

The Natural Object Dataset (NOD) Protocol

The Natural Object Dataset exemplifies rigorous multimodal data collection, incorporating fMRI, MEG, and EEG from the same participants viewing identical naturalistic stimuli. This protocol enables precise characterization of neural spatiotemporal dynamics during natural object recognition [16].

Stimuli Selection and Presentation: The protocol employs a three-stage selection process for natural images from ImageNet, ensuring square aspect ratio (≈1), high resolution (>100,000 pixels), and accurate labeling through visual inspection. Each trial lasts approximately 1500 ms, with stimulus presentation for 800 ms followed by a variable fixation period (700 ± 200 ms) [16]. Stimuli are presented at 600 × 600 pixels (visual angle = 16°) at a viewing distance of 700 mm, with participants performing animacy judgments to maintain engagement.

Multimodal Data Acquisition Parameters:

- MEG: Recorded using a 275-channel whole-head axial gradiometer system at 1200 Hz sampling rate, with real-time markers for precise stimulus-response synchronization [16].

- EEG: Acquired with matching trial structure, with each run consisting of 125 trials lasting approximately 190 seconds [16].

- fMRI: Collected using standard protocols with high spatial resolution, aligned with MEG/EEG acquisition in the same participants.

This coordinated approach yields a comprehensive dataset with 57,000 naturalistic image responses across 30 participants, providing unprecedented resources for investigating HOIs across spatiotemporal scales [16].

Table 2: NOD Protocol Acquisition Parameters

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Participants | Stimuli | Key Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Millimeter scale | ~0.72s TR | 30 | 57,000 images | BOLD response, spatial patterns |

| MEG | Coarse (source estimated) | 1200 Hz | 30 | 57,000 images | Magnetic fields, tangential sources |

| EEG | Coarse (source estimated) | High sampling rate | 19 | 56,000 images | Electrical potentials, radial sources |

Whole-Brain Modeling Approaches

Whole-brain modeling overcomes technical limitations of empirical data by simulating neural activity across flexible spatiotemporal scales. The Dynamic Mean Field Model generates simulated time series with temporal scales from milliseconds to seconds while accommodating various spatial parcellations (100-900 regions) [14]. This approach conceptualizes the underlying synaptic connectivity and neural population dynamics that generate empirical signals using mean-field approximations [14].

The methodology involves:

- Parcellation: Brain regions defined using optimized atlases (e.g., Schaefer parcellation) across multiple spatial scales (100-900 regions)

- Structural Connectome: Derived from diffusion MRI tractography, representing interregional fiber counts

- Model Fitting: Parameters optimized to match empirical functional connectivity patterns

- Simulation: Time series generated across temporal scales (milliseconds to seconds)

- Dynamic Analysis: Functional network transitions quantified through entropy measures

This computational framework enables systematic investigation of spatiotemporal scales impossible with empirical data alone, revealing optimal parameters for capturing whole-brain dynamics relevant to HOIs [14].

Analyzing Higher-Order Interactions Across Scales

Defining and Quantifying HOIs in Multimodal Data

Higher-Order Interactions move beyond pairwise correlations to capture complex, non-additive relationships among multiple neural elements. In the context of multimodal data, HOIs can manifest as:

- Spatiotemporal dependencies where the relationship between two regions depends on activity in a third region, varying across temporal epochs

- Cross-frequency couplings where oscillations in different frequency bands (measured by EEG/MEG) interact with spatial networks (identified by fMRI)

- Network-level interactions where the integration between functional systems exhibits non-linear properties

The entropy of transitions between whole-brain functional networks serves as a key metric for quantifying the dynamic repertoire available to the brain, with maximal complexity observed at specific spatiotemporal scales [14].

Practical Framework for Multimodal HOI Analysis

A systematic approach to HOI analysis involves:

- Data Harmonization: Co-registration of multimodal data to common coordinate systems and temporal sampling

- Feature Extraction: Modality-specific characterization of neural activity (e.g., EEG time-frequency features, fMRI connectivity matrices)

- HOI Detection: Application of information-theoretic, higher-order correlation, or phase-synchrony measures

- Cross-scale Integration: Relating HOIs identified at different spatiotemporal scales

- Validation: Convergence across modalities and statistical significance testing

This framework leverages the complementary strengths of each modality while mitigating their individual limitations for comprehensive HOI characterization.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Multimodal HOIs Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Parcellation Atlases | Schaefer parcellation (100-900 regions) [14] | Defining spatial scales of analysis; Optimizes local gradient and global similarity measures |

| Multimodal Datasets | Natural Object Dataset (NOD) [16], THINGS dataset | Providing coordinated fMRI, MEG, EEG data for method development and validation |

| Source Imaging Tools | fMRI-informed time-variant constraint (FITC) algorithms [13] | Integrating spatial (fMRI) and temporal (EEG/MEG) constraints for improved source localization |

| Whole-Brain Modeling | Dynamic Mean Field Model [14] | Simulating neural dynamics across flexible spatiotemporal scales beyond empirical limitations |

| Multivariate Analysis | Partial Least Squares, Canonical Correlation Analysis [15] | Identifying latent relationships between multimodal data sets |

| Quality Control Metrics | Cross-talk matrix, normalized partial area under curve [13] | Evaluating and mitigating impact of fMRI missing sources in constrained source imaging |

Visualizing Multimodal Integration Workflows

Experimental Protocol for Multimodal Data Collection

fMRI-Informed EEG/MEG Source Imaging with FITC

Whole-Brain Modeling Across Spatiotemporal Scales

The investigation of Higher-Order Interactions in brain networks demands careful consideration of spatiotemporal scales that cannot be captured by any single neuroimaging modality. The integration of fMRI with EEG and MEG, informed by computational modeling and advanced statistical fusion techniques, provides a powerful framework for elucidating these complex dynamics. Empirical evidence suggests optimal spatial scales around 300 brain regions and temporal scales near 150 milliseconds for capturing the full richness of brain network transitions [14].

Future advancements in this field will likely be driven by several critical developments. Artificial intelligence approaches are increasingly enabling the fusion of multimodal neuroimaging data for precision medicine applications in neuropsychiatric disorders [17]. Large-scale multimodal datasets like the Natural Object Dataset are expanding available resources for method validation and discovery [16]. Additionally, advanced whole-brain modeling techniques continue to bridge spatiotemporal scales, offering insights into the fundamental principles governing brain dynamics across spatial resolutions and temporal domains [14].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these methodological advances offer new avenues for identifying biomarkers, understanding disease mechanisms, and developing targeted interventions for neuropsychiatric disorders characterized by disturbances in brain network interactions. The continued refinement of multimodal integration approaches will undoubtedly enhance our capacity to capture the spatiotemporal complexity of higher-order brain interactions, advancing both basic neuroscience and clinical applications.

Quantifying Complexity: Methodologies and Clinical Applications of HOIs

The study of brain networks has traditionally relied on pairwise statistical measures to describe functional connectivity between neural elements. However, mounting evidence suggests that complex cognitive functions emerge from intricate interactions that extend beyond simple pairwise relationships, involving simultaneous information sharing among multiple brain regions. These higher-order interactions (HOIs) represent a fundamental aspect of neural computation that requires specialized mathematical tools for proper quantification and analysis. Within this context, three core computational methods have emerged as particularly powerful for probing the multivariate nature of brain organization: Total Correlation (TC), Dual Total Correlation (DTC), and Topological Data Analysis (TDA).

The limitation of conventional pairwise approaches is particularly evident in neural systems, where synergistic information—that which is available only from the joint observation of multiple variables—plays a crucial role in cognitive processing. Recent studies have demonstrated that information gain during goal-directed learning is encoded through synergistic interactions at the level of triplets and quadruplets of brain regions, revealing HOIs characterized by long-range relationships centered in ventromedial and orbitofrontal cortices [7]. Similarly, analyses of resting-state fMRI data have shown that some HOI hubs predominantly occur in primary and high-level cognitive areas, playing a crucial role in information integration [18]. These findings underscore the necessity for analytical frameworks capable of capturing the full complexity of neural systems.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of TC, DTC, and TDA as essential tools for neuroscience research, with particular emphasis on their theoretical foundations, methodological implementation, and application to the study of HOIs in brain networks. We present standardized protocols, quantitative comparisons, and visualization frameworks to facilitate the adoption of these methods by researchers and drug development professionals working in computational neuroscience.

Theoretical Foundations

Total Correlation (Multi-Information)

Total Correlation (TC), also known as multi-information, is a multivariate generalization of mutual information that quantifies the total shared information or dependence among an n-tuple of random variables [19]. For a set of n random variables X = {X₁, X₂, ..., Xₙ}, TC is defined as:

[ TC(X1,\ldots,Xn) \equiv \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi) - H(X1,\ldots,Xn) = D{KL} \left( p(x1,\ldots,xn) \middle\| \prod{i=1}^{n} p(x_i) \right) ]

where H(·) represents the Shannon entropy, and D({}_{KL}) is the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the joint probability distribution and the product of marginal distributions [19]. TC reduces to mutual information when n=2 and provides a holistic measure of the overall statistical dependence among multiple variables. A TC value of zero indicates complete independence among all variables, while higher values indicate stronger shared dependencies.

In neuroscience, TC has been shown to outperform mutual information in capturing the effect of different intra-cortical inhibitory connections and detecting synergies in analytical models with feedback [19]. Unlike pairwise measures, TC can describe multivariate dependencies that are distributed across multiple brain regions simultaneously, making it particularly suitable for identifying functional modules or networks that operate in a coordinated manner.

Dual Total Correlation (Binding Information)

Dual Total Correlation (DTC), also known as binding information or excess entropy, represents an alternative multivariate generalization of mutual information that captures the information shared among multiple variables through a different theoretical lens [20] [21]. For the same set of n random variables, DTC is defined as:

[ D(X1,\ldots,Xn) = H(X1,\ldots,Xn) - \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi \mid X1,\ldots,X{i-1},X{i+1},\ldots,Xn) ]

where H(Xᵢ | ··· ) represents the conditional entropy of Xᵢ given all other variables [20]. Intuitively, DTC measures the information that is shared among all variables, or the "binding" information that holds the system together. Historically, Han (1978) originally defined DTC equivalently as:

[ D(X1,\ldots,Xn) \equiv \left[\sum{i=1}^{n} H(X1,\ldots,X{i-1},X{i+1},\ldots,Xn)\right] - (n-1) H(X1,\ldots,X_n) ]

which highlights its relationship to the sum of entropies of all possible subsets missing exactly one variable [20].

The distinction between TC and DTC becomes conceptually significant when considering their different interpretations: TC measures the total deviation from independence, while DTC quantifies the information shared among all variables simultaneously. This makes DTC particularly sensitive to global constraints that affect the entire system, as opposed to TC which captures all dependencies regardless of their scope.

Relationships and Comparative Properties

TC and DTC are related through several important theoretical bounds and identities. First, both measures are non-negative and bounded, but by different quantities:

[ 0 \leq TC(X1,\ldots,Xn) \leq \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi) ] [ 0 \leq D(X1,\ldots,Xn) \leq H(X1,\ldots,Xn) ]

More importantly, TC and DTC obey the following inequality relationship:

[ \frac{TC(X1,\ldots,Xn)}{n-1} \leq D(X1,\ldots,Xn) \leq (n-1) \; TC(X1,\ldots,Xn) ]

This shows that DTC is always within a polynomial factor of TC, but can differ significantly in quantitative terms [20]. The two measures take on extreme values for different types of distributions: TC is maximized by a "giant bit" distribution (where all variables are identical), while DTC is maximized by a parity distribution (where the sum of all variables is fixed) [21].

A particularly insightful relationship emerges when considering the difference between TC and DTC, which defines the O-information (originally introduced as "enigmatic information"):

[ \Omega(X) = C(X) - D(X) ]

where C(X) represents TC [20]. The O-information is a signed measure that quantifies the balance between redundancy (when Ω(X) > 0) and synergy (when Ω(X) < 0) in multivariate systems [20]. This provides a powerful framework for characterizing different regimes of information sharing in neural systems, allowing researchers to determine whether brain regions primarily share the same information (redundancy) or generate new information through their interactions (synergy).

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Total Correlation and Dual Total Correlation

| Property | Total Correlation (TC) | Dual Total Correlation (DTC) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | (\sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi) - H(X1,\ldots,Xn)) | (H(X1,\ldots,Xn) - \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi \mid X_{\setminus i})) |

| Alternative Form | Kullback-Leibler divergence between joint and product of marginals | Sum of entropies of all (n-1)-variable subsets minus (n-1) times joint entropy |

| Theoretical Bounds | (0 \leq TC \leq \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi)) | (0 \leq DTC \leq H(X1,\ldots,Xn)) |

| Measures | Total deviation from independence | Information shared among all variables |

| Maximizing Distribution | "Giant bit" (all variables identical) | Parity distribution (XOR function) |

| Neuroscience Interpretation | Overall functional connectivity strength | Integrated information or binding |

| Relationship | (\frac{TC}{n-1} \leq DTC \leq (n-1)TC) | (\Omega(X) = TC(X) - DTC(X)) (O-information) |

Methodological Implementation

Estimation Techniques for High-Dimensional Data

Applying TC and DTC to real-world neural data presents significant computational challenges, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional recordings from hundreds of brain regions. Direct estimation of these information-theoretic quantities from empirical distributions is infeasible due to the curse of dimensionality and the limited samples typically available in neuroscience experiments.

Correlation Explanation (CorEx) is a machine learning method that provides an effective approach for estimating TC in high-dimensional settings [19]. CorEx works by constructing a latent factor model that maximizes the TC between the observed data and a set of latent variables, effectively performing unsupervised discovery of multivariate dependencies. The method has been validated against ground truth values and shown to produce trustable clustering results even with whole-brain fMRI data involving hundreds of regions [19]. The core innovation of CorEx lies in its ability to lower the computational complexity of TC estimation while maintaining robustness to noise and outliers.

For conditional TC and DTC calculations, which are essential for controlling for confounding variables or examining specific subsystems, the Kullback-Leibler divergence formulation provides a foundation for estimation:

[ TC(X|Y) = \sum{i} H(Xi|Y) - H(X|Y) = D{KL}(p(x|y) \|\prod{i=1}^{n} p(x_i|y)) ]

Recent advances include Local CorEx, which extends the CorEx framework to capture HOIs at a local scale by first clustering data points based on their proximity on the data manifold, then applying multivariate TC within each cluster to learn local interaction patterns [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying context-dependent neural interactions that may change across different cognitive states or behavioral conditions.

Topological Data Analysis for Neural Systems

Topological Data Analysis (TDA) provides a complementary approach to information-theoretic methods for studying HOIs in brain networks. TDA uses techniques from algebraic topology to extract robust, shape-driven insights from complex datasets, with persistent homology being its main workhorse [23] [24]. The fundamental idea behind TDA is that the shape of data sets contains relevant information about the underlying system, and that topological features that persist across multiple scales are likely to represent true structural characteristics rather than noise [23].

The standard TDA workflow involves three main steps:

- Converting point cloud data (e.g., neural activity measurements) into a sequence of nested simplicial complexes at different spatial scales

- Computing the homology groups of each complex to identify topological features (connected components, loops, voids)

- Tracking the birth and death of these features across scales to create a persistence diagram or barcode [23]

For brain network analysis, TDA offers several unique advantages: it is insensitive to the particular metric chosen, provides dimensionality reduction and robustness to noise, and inherits functoriality from its topological nature [23]. Recently, methods beyond persistent homology have emerged, including persistent topological Laplacians and Dirac operators that provide spectral representations capturing both topological invariants and homotopic evolution [25]. Additionally, persistent cohomotopy has been introduced as an effective method for determining whether any data points meet a prescribed target indication precisely, with proven computability in a fair range of dimensions [24].

Table 2: Topological Data Analysis Methods for Neural Data

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Neuroscience Application | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent Homology | Algebraic topology; tracks birth/death of topological features across scales | Identifying recurrent neural assemblies; characterizing network architecture | Robust to noise; captures multiscale organization |

| Persistent Cohomotopy | Homotopy theory; detects data points meeting target values | Precision neuroimaging; identifying specific neural activity patterns | Provably computable; detects exact matches to target indicators |

| Persistent Topological Laplacians | Spectral geometry; combines topological and geometric information | Multimodal neural integration; linking structure and dynamics | Captures both topological invariants and homotopic evolution |

| Mayer Vietoris | Sheaf theory; analyzes coverage complexes | Large-scale network decomposition; module identification | Handles complex coverage patterns; suitable for distributed computation |

| Multiscale Gauss-link Integrals | Geometric topology; analyzes 1D curves in 3-space | White matter tractography; neural pathway analysis | Specialized for 1D structures embedded in 3D space |

Experimental Protocols for Neuroscience Applications

Protocol 1: Whole-Brain Functional Connectivity Using Total Correlation

This protocol describes the estimation of large-scale (whole-brain) connectivity networks based on TC for biomarker discovery in altered brain states [19].

Materials and Data Acquisition

- Imaging Data: Resting-state or task-based fMRI data from at least 50 participants per group (healthy controls and clinical population)

- Preprocessing Pipeline: Standard fMRI preprocessing including motion correction, slice-timing correction, spatial normalization to MNI space, and band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz)

- ROI Parcellation: Atlas-based definition of 100-300 brain regions (e.g., AAL, Harvard-Oxford, or Yeo networks)

- Software Requirements: Python with CorEx implementation (available at https://github.com/gregversteeg/CorEx)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Preparation: Extract mean time series from each ROI for all participants, then compute the (n \times n) covariance matrix for each subject.

- TC Estimation: Apply CorEx to estimate the TC between all ROIs simultaneously. CorEx optimizes the following objective: [ TC(X;Y) = \sum{i=1}^{n} I(Xi;Y) - I(X;Y) ] where Y represents latent factors.

- Network Construction: Threshold the resulting TC matrix to create a binary or weighted connectivity network. Recommended threshold: retain top 10-20% of connections based on TC values.

- Validation: Compare CorEx results with ground truth using synthetic data with known dependencies [19]. Validate biological plausibility by checking for known resting-state networks (default mode, salience, executive control).

- Biomarker Identification: Apply graph theory metrics (modularity, clustering coefficient, characteristic path length) to identify network alterations in clinical populations.

Expected Outcomes and Interpretation Successful implementation should reveal a whole-brain connectivity network consistent with established neuroscience knowledge but potentially capturing additional relations beyond pairwise regions [19]. Networks based on TC have shown potential as effective tools for aiding in the discovery of brain diseases, with altered connectivity patterns in clinical populations potentially serving as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers.

Protocol 2: Higher-Order Synergy-Redundancy Balance with O-Information

This protocol measures the balance between synergistic and redundant HOIs during cognitive tasks using O-information, which combines TC and DTC [20] [7].

Materials and Data Acquisition

- Neural Recording: Magnetoencephalography (MEG) data during goal-directed learning tasks, source-localized to cortical regions

- Behavioral Task: Instrumental learning paradigm with controlled exploration phases (e.g., discovering stimulus-response associations through trial-and-error)

- Computational Model: Fitted Q-learning algorithm to extract trial-by-trial reward prediction errors and information gain signals

- Software Requirements: Custom MATLAB/Python scripts for partial information decomposition, O-information calculation

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Signal Extraction: Compute high-gamma activity (60-120 Hz) from MEG source data for 20-30 key brain regions involved in learning (visual, parietal, lateral prefrontal, ventromedial/orbital prefrontal cortices).

- Trial Alignment: Segment neural data into trials time-locked to outcome presentation, with baseline correction.

- Information Dynamics: Calculate TC and DTC within sliding time windows (e.g., 50ms steps) across multiple brain regions simultaneously: [ \Omega(X) = TC(X) - DTC(X) ] where X represents the multivariate neural activity pattern.

- Statistical Testing: Identify time windows with significant O-information values (permutation testing with FDR correction) and classify as redundancy-dominated ((\Omega > 0)) or synergy-dominated ((\Omega < 0)).

- Behavioral Correlation: Relate trial-by-trial fluctuations in O-information to computational model-derived information gain signals using mixed-effects models.

Expected Outcomes and Interpretation This protocol typically reveals that information gain is encoded through synergistic interactions at the level of triplets and quadruplets of brain regions, with higher-order synergistic interactions characterized by long-range relationships centered in ventromedial and orbitofrontal cortices [7]. These regions often serve as key receivers in the broadcast of information gain across cortical circuits, highlighting their integrative role in learning.

Protocol 3: Topological Analysis of Brain Network Architecture

This protocol applies TDA to characterize the higher-order topology of functional brain networks and its relationship to cognitive function [23] [18].

Materials and Data Acquisition

- Imaging Data: Resting-state fMRI from at least 100 participants (public datasets such as Human Connectome Project can be used)

- Network Construction: Pearson correlation or total correlation matrices between 200-400 brain regions

- Software Requirements: Python with TDA libraries (GUDHI, Scikit-TDA) or R with TDA/TDAstats packages

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Simplicial Complex Construction: For each subject's correlation matrix, create a filtration of simplicial complexes using a decreasing sequence of correlation thresholds (from 0.9 to 0.1 in 0.05 steps).

- Persistent Homology Computation: Calculate persistent homology for dimensions 0, 1, and 2 (connected components, cycles, and voids) across the filtration using the Vietoris-Rips complex.

- Persistence Diagram Generation: Create persistence diagrams for each topological dimension, representing birth and death times of topological features.

- Topological Summary Statistics: Compute persistence-based summary statistics:

- Betti curves: (\beta_k(\epsilon)) as function of threshold (\epsilon)

- Persistence entropy: (Ek = -\sumi pi \log pi) where (pi = persi / \sumj persj)

- Wasserstein distances between group-level persistence diagrams

- Correlation with Cognition: Relate topological metrics to cognitive test scores (e.g., executive function, memory) using multivariate regression models controlling for age, sex, and motion.

Expected Outcomes and Interpretation Application of this protocol typically reveals that high-order interaction hubs predominantly occur in primary and high-level cognitive areas, such as visual and fronto-parietal regions [18]. These topological hubs play a crucial role in information integration in the human brain, and their disruption may be associated with cognitive impairment in neuropsychiatric disorders. The correlation of correlation networks approach has been shown to highlight network connections while preserving the topological structure of correlation networks, potentially surpassing traditional correlation networks in capturing higher-order architectural features [18].

Visualization Framework

Workflow for Higher-Order Interaction Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for analyzing HOIs in brain networks using TC, DTC, and TDA:

Topological Data Analysis Pipeline