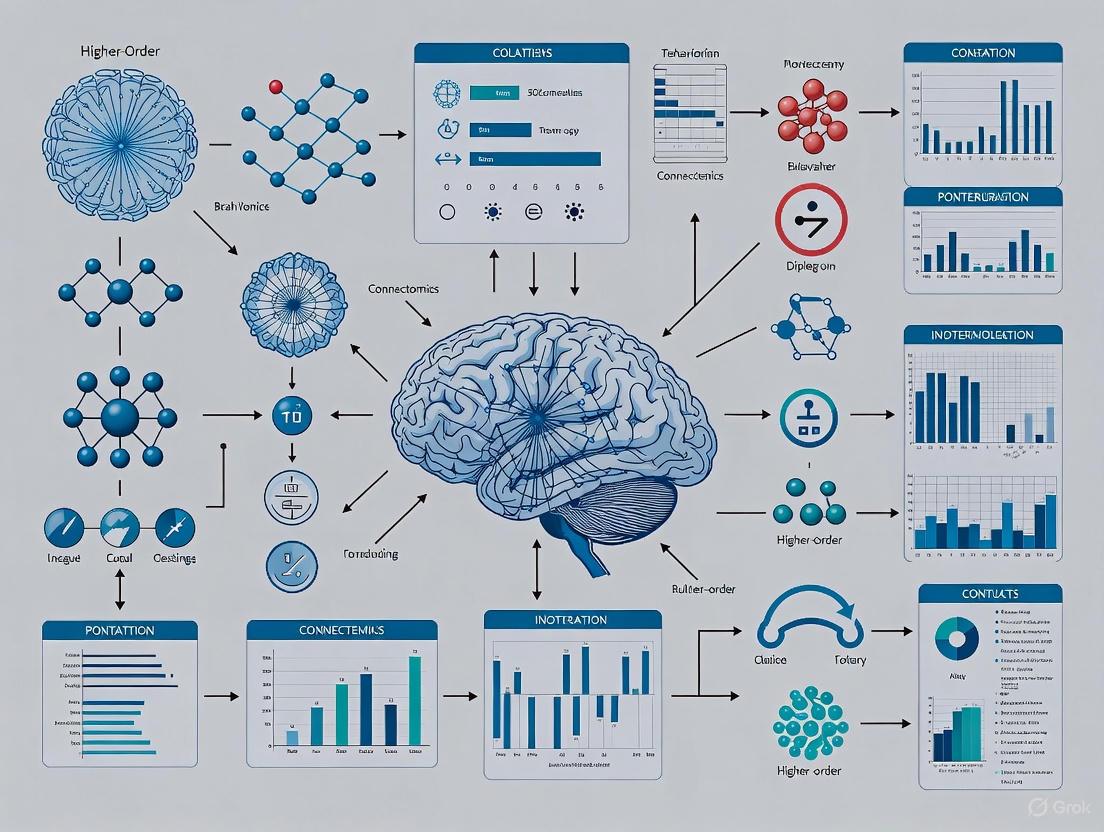

Beyond Pairwise Connections: How Higher-Order Connectomics is Revolutionizing Our Understanding of Human Brain Function

Moving beyond traditional pairwise models of brain connectivity, higher-order connectomics captures complex interactions among three or more brain regions simultaneously.

Beyond Pairwise Connections: How Higher-Order Connectomics is Revolutionizing Our Understanding of Human Brain Function

Abstract

Moving beyond traditional pairwise models of brain connectivity, higher-order connectomics captures complex interactions among three or more brain regions simultaneously. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles that define these multi-region interactions and the advanced mathematical frameworks, such as simplicial complexes and information theory, used to quantify them. We detail methodological applications that demonstrate superior performance in task decoding and individual identification, while also addressing critical statistical challenges and optimization strategies for robust analysis. Finally, we present comparative evidence validating higher-order approaches against traditional methods, highlighting their enhanced ability to reveal biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric conditions and their promising role in monitoring treatment response, thereby charting a course for their future in biomedical research and clinical application.

The Limits of Pairwise Models and the Rise of a Higher-Order Paradigm

Traditional models of human brain function have predominantly represented brain activity as a network of pairwise interactions between brain regions [1]. This approach, while foundational, is fundamentally limited by its underlying hypothesis that interactions between nodes are strictly dyadic [1]. Going beyond this limitation requires frameworks that can capture higher-order interactions (HOIs)—simultaneous relationships involving three or more brain regions [1]. In the context of brain connectomics, these HOIs are crucial for fully characterizing the brain's complex spatiotemporal dynamics, as significant information may reside only in joint probability distributions rather than pairwise marginals [1] [2].

The field has evolved along two primary paradigms for studying these complex relationships [2]. Implicit paradigms focus on quantifying the statistical strength of group interactions, while explicit paradigms construct higher-order structural representations using mathematical constructs like hypergraphs and topological data analysis [2]. This progression represents a fundamental shift in neuroscience, enabling researchers to detect brain biomarkers that remain hidden to traditional approaches and potentially differentiate between clinical populations [1].

Theoretical Frameworks and Representations

Comparative Analysis of Network Representations

| Representation Type | Basic Unit | Mathematical Structure | Key Properties | Brain Network Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Graph | Edge (2 nodes) | G = (V, E) where E ⊆ V × V | Models direct pairwise relationships; Limited to dyadic connections | Traditional functional connectivity; Simple correlation-based networks [1] |

| Network Motifs | Small subgraph (k nodes) | Frequent, statistically significant subgraphs | Identifies recurring local patterns; Building blocks of networks | Neural efficiency patterns; Functional subcircuits [3] |

| Simplicial Complex | Simplex (k nodes) | Collection closed under subset inclusion | Downward closure property; Natural for topological analysis | Temporal brain dynamics; Multi-region coordinated activity [1] [4] |

| Hypergraph | Hyperedge (k nodes) | H = (V, E) where E ⊆ 2^V | Most general representation; No subset requirement | Group co-activations; Abstract cognitive assemblies [4] [3] |

Explicit Higher-Order Representations

Simplicial complexes provide a natural mathematical framework for representing nested interactions in brain dynamics [4]. A simplicial complex is a collection of sets (simplices) that is closed under taking subsets—for any simplex in the complex, all its non-empty subsets are also included [4]. This downward closure property makes them ideal for modeling brain interactions where the presence of a three-region interaction implies the existence of all constituent two-region interactions [3]. In practice, a k-simplex represents an interaction among (k+1) brain regions, with 0-simplices as nodes, 1-simplices as edges, 2-simplices as triangles, and so on [1].

Hypergraphs offer a more flexible alternative where hyperedges represent multiway connections without the subset requirement of simplicial complexes [4]. This makes them particularly suitable for modeling group interactions where the entire set of regions functions as a unit, and subgroup interactions don't necessarily capture the same functional meaning [3]. For brain networks, this distinction is crucial when analyzing transient functional assemblies that operate as complete ensembles rather than through their subsets.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Topological Pipeline for Inferring HOIs from fMRI

Diagram Title: Topological Pipeline for Inferring HOIs from fMRI

Protocol 1: Topological Inference of Higher-Order Interactions

Application: Inferring instantaneous HOIs from fMRI time series data [1]

Step 1: Signal Standardization

- Obtain fMRI time series from N brain regions (typically 100 cortical and 19 subcortical regions) [1]

- Apply z-scoring to each regional BOLD signal to standardize variance [1]

- Output: N standardized time series x̂₁(t), x̂₂(t), ..., x̂_N(t)

Step 2: Compute k-order Time Series

- Calculate all possible k-order time series as element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored signals [1]

- For triangles (k=2): Wᵢⱼₖ(t) = x̂ᵢ(t) · x̂ⱼ(t) · x̂ₖ(t) followed by re-standardization [1]

- Apply sign remapping: positive for fully concordant group interactions, negative for discordant interactions [1]

- Output: Edge time series (k=1) and triangle time series (k=2) representing co-fluctuation magnitudes

Step 3: Construct Weighted Simplicial Complex

- For each timepoint t, encode all k-order time series into a weighted simplicial complex [1]

- Assign weight of each simplex as value of associated k-order time series at timepoint t [1]

- Output: Time-varying sequence of weighted simplicial complexes

Step 4: Extract Topological Indicators

- Apply computational topology tools to analyze simplicial complex weights [1]

- Extract local indicators: violating triangles identity/weights and homological scaffolds [1]

- Extract global indicators: hyper-coherence and coherent/decoherent contributions [1]

- Output: Quantitative HOI metrics for downstream analysis

Validation and Analytical Protocols

Protocol 2: Task Decoding and Brain Fingerprinting with HOIs

Application: Dynamic task decoding and individual identification using HOI features [1]

Step 1: Data Preparation and Block Design

- Concatenate resting-state fMRI (first 300 volumes) with task fMRI data, excluding rest blocks [1]

- Create unified fMRI recording across multiple task conditions [1]

- Note: Uses HCP dataset with 100 unrelated subjects [1]

Step 2: Recurrence Plot Construction

- For each local method (BOLD, edges, triangles, scaffold), compute time-time correlation matrices [1]

- Calculate Pearson's correlation between temporal activation at distinct timepoints for each indicator [1]

- Output: Recurrence plots encoding temporal similarity structure

Step 3: Community Detection and Task Decoding

- Binarize correlation matrices at 95th percentile of respective distributions [1]

- Apply Louvain algorithm to identify communities in thresholded matrices [1]

- Output: Community partitions corresponding to task and rest blocks

Step 4: Performance Validation

- Compute element-centric similarity (ECS) between community partitions and ground truth task timings [1]

- ECS = 0 indicates bad task decoding, ECS = 1 indicates perfect task identification [1]

- Compare performance of HOI methods versus traditional pairwise approaches [1]

Quantitative Results and Performance Metrics

Comparative Performance of HOI versus Pairwise Methods

| Analytical Task | Traditional Pairwise Methods | Higher-Order Methods | Performance Improvement | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Task Decoding | Limited temporal resolution of task-rest transitions [1] | Enhanced identification of task timing through recurrence plots [1] | Significant improvement in block timing accuracy [1] | Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) [1] |

| Individual Identification | Moderate functional fingerprinting capability [1] | Improved identification of unimodal and transmodal subsystems [1] | Enhanced subject discrimination accuracy [1] | Functional fingerprinting accuracy [1] |

| Brain-Behavior Association | Moderate correlation with behavioral measures [1] | Significantly stronger associations with behavior [1] | Robust brain-behavior relationship modeling [1] | Correlation strength with behavior [1] |

| Local versus Global Encoding | Comparable global performance [1] | Superior local topological signatures [1] | Spatially-specific advantage for local connectivity [1] | Spatial specificity of signatures [1] |

Key HOI Metrics and Their Neurobiological Interpretation

| HOI Metric | Mathematical Definition | Neurobiological Interpretation | Analytical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyper-coherence | Fraction of higher-order triplets co-fluctuating more than expected from pairwise edges [1] | Identifies brain regions forming synergistic functional units beyond pairwise correlation [1] | Global indicator of higher-order brain coordination [1] |

| Violating Triangles (Δv) | Triangles whose standardized simplicial weight exceeds corresponding pairwise edges [1] | Represents triplets of regions with emergent coordination not explainable by pairwise relationships [1] | Local indicator of irreducible three-region interactions [1] |

| Homological Scaffold | Weighted graph highlighting edge importance in mesoscopic topological structures [1] | Identifies connections critical for maintaining global brain network architecture and 1D cycles [1] | Mesoscopic structural analysis; persistent homology [1] |

| Coherence/Decoherence Landscape | Distinction between fully coherent, transition, and fully decoherent contributions [1] | Quantifies balance between integrated and segregated brain states across time [1] | Dynamic brain state characterization [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Dataset | Neuroimaging Data | Provides high-quality fMRI data for 100+ unrelated subjects [1] | Primary data source for method validation and benchmarking [1] |

| Topological Data Analysis (TDA) Libraries | Computational Tool | Algorithms for simplicial complex construction and persistence homology [1] | Higher-order interaction inference and quantification [1] |

| 119-Region Brain Parcellation | Atlas Template | Standardized cortical (100) and subcortical (19) region definition [1] | Consistent ROI definition across studies [1] |

| Louivain Community Detection | Algorithm | Network community identification in thresholded recurrence matrices [1] | Task block identification and dynamic state decoding [1] |

| Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) | Validation Metric | Quantifies similarity between community partitions and ground truth [1] | Performance evaluation of task decoding accuracy [1] |

Conceptual Framework for HOI Method Selection

Diagram Title: HOI Method Selection Framework

The integration of higher-order interaction analysis into connectomics research represents a paradigm shift from traditional pairwise connectivity models. The protocols outlined here provide a comprehensive framework for detecting, quantifying, and interpreting these complex multi-region interactions in human brain function. The empirical evidence demonstrates that higher-order approaches significantly enhance dynamic task decoding, improve individual identification of functional subsystems, and strengthen associations between brain activity and behavior [1].

Critically, the advantages of higher-order methods appear most pronounced at local topological scales, suggesting a spatially-specific role for HOIs in functional brain coordination that complements rather than replaces traditional global pairwise approaches [1]. This indicates that future connectomics research should adopt a hybrid analytical strategy that selectively applies higher-order methods where they provide maximal insight—particularly for understanding transient brain states, cognitive task dynamics, and individual differences in brain network organization.

Implementation of these protocols requires careful attention to the theoretical distinctions between implicit and explicit higher-order modeling approaches [2], as well as selection of appropriate representation frameworks (hypergraphs, simplicial complexes, or motif-based analyses) based on the specific research question and data structure [4] [3]. The continued refinement of these methodologies promises to reveal a vast space of previously unexplored structures within human functional brain data that remain hidden when using traditional pairwise approaches alone [1].

Traditional models of human brain function have predominantly represented neural activity as a network of pairwise interactions between distinct brain regions. This approach, while foundational, is inherently limited by its underlying assumption that all complex brain dynamics can be decomposed into simple binary relationships. Mounting evidence now indicates that higher-order interactions (HOIs)–simultaneous relationships involving three or more brain regions–are crucial for fully characterizing the brain's complex spatiotemporal dynamics. These HOIs represent information that exists only in the joint probability distributions of neural activity and cannot be captured by analyzing pairwise marginals alone. This Application Note details the theoretical imperative for examining these joint distributions and provides standardized protocols for their analysis within human brain function research, with particular relevance for developing diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets [1].

The core theoretical insight is that methods relying solely on pairwise statistics are insufficient to identify significant higher-order behaviors in neural systems. Joint probability distributions contain a vast space of unexplored structures that remain hidden to traditional connectome approaches. Reconstructing HOIs from neuroimaging signals addresses this gap, offering a more nuanced framework to explain how dynamic neural groups coordinate to produce cognition, emotion, and perception. This approach represents a fundamental shift from methods like functional connectivity (FC) or Independent Component Analysis (ICA) toward a more comprehensive model that can differentiate between healthy states and clinical populations, including disorders of consciousness or Alzheimer's disease [1].

Quantitative Data on HOI Efficacy in Brain Research

Empirical Performance of HOI Methods

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Connectivity Methods in fMRI Analysis [1]

| Analysis Metric | Pairwise/Edge Methods | Higher-Order Methods | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Decoding (Dynamic) | Moderate | High | Greatly enhanced dynamic decoding between various tasks |

| Individual Identification | Possible | Improved | Better fingerprinting of unimodal and transmodal subsystems |

| Behavior-Brain Association | Significant | Significantly Stronger | Significantly strengthened associations |

| Global Scale Analysis | Effective | Not significantly better | Localized HOI role suggested |

| Local Scale Analysis | Effective | Superior | Local topological signatures provide primary benefit |

Table 2: 2025 Alzheimer's Disease Drug Development Pipeline Context [5]

| Therapeutic Category | Number of Drugs | Percentage of Pipeline | Relevance to HOI Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological DTTs | ~41 | 30% | High (Potential for novel HOI-based target engagement biomarkers) |

| Small Molecule DTTs | ~59 | 43% | High (Potential for novel HOI-based efficacy biomarkers) |

| Cognitive Enhancers | ~19 | 14% | Moderate (HOI could track acute functional changes) |

| Neuropsychiatric Symptom | ~15 | 11% | Moderate (HOI may relate to circuit-level dysfunction) |

| Total Novel Drugs | 138 | - | - |

| Repurposed Agents | ~45 | 33% | High (HOI can provide new mechanistic insights for existing drugs) |

| Trials Using Biomarkers | ~49 | 27% | Very High (HOI methods represent a new class of functional biomarker) |

Experimental Protocols for HOI Inference from fMRI

Protocol 1: Temporal Higher-Order Interaction Inference

This protocol details the topological data analysis approach for reconstructing HOI structures from fMRI time series, adapted from the method that demonstrated superior task decoding and individual identification in HCP data [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software Environment: Python (v3.9+) with NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn libraries.

- Topological Analysis: Ripser.py or GUDHI Python libraries for computational topology.

- Data Source: Preprocessed fMRI time series (e.g., from HCP: 100 unrelated subjects, 119 regions parcellation).

- Computational Resources: Minimum 16GB RAM; High-performance computing cluster recommended for large datasets.

Procedure:

- Signal Standardization: For each of the N original fMRI signals (representing BOLD activity from distinct brain regions), apply z-scoring to standardize the time series to mean=0 and standard deviation=1 [1].

- k-Order Time Series Computation: Calculate all possible k-order time series as the element-wise products of k+1 z-scored time series. For example, a 2-order time series (representing triple interactions) is computed as the product of three regional time series. Apply a second z-scoring to these product time series to ensure cross-k-order comparability [1].

- Sign Assignment: Assign a sign to each k-order time series at every timepoint based on parity:

- Positive: All (k+1) node time series have fully concordant values (all positive or all negative) → "fully coherent".

- Negative: A mixture of positive and negative values among the (k+1) nodes → "discordant" [1].

- Simplicial Complex Construction: At each timepoint t, encode all instantaneous k-order co-fluctuation time series into a weighted simplicial complex. Define each simplex's weight as the value of its associated k-order time series at t. This creates a temporal sequence of topological objects representing the evolving higher-order structure [1].

- Topological Indicator Extraction: Apply computational topology tools (persistent homology) to each simplicial complex at time t to extract indicators:

- Local: List and weights of "violating triangles" (Δv) - triangles whose weight exceeds their constituent edges.

- Local: Homological scaffolds - weighted graphs highlighting edges important to 1D cycles in the HOI landscape.

- Global: Hyper-coherence - fraction of higher-order triplets co-fluctuating beyond pairwise expectations [1].

- Validation and Downstream Analysis:

- Construct recurrence plots from local indicator time series (BOLD, edges, triangles, scaffold).

- Create time-time correlation matrices and binarize at 95th percentile.

- Apply community detection (e.g., Louvain algorithm) to identify task/rest states.

- Validate using Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) measure against known block timings [1].

Protocol 2: Multicellular Brain Model Validation for HOI Biomarkers

This protocol leverages advanced in vitro brain models to validate HOI signatures discovered in human neuroimaging, linking them to cellular and molecular mechanisms relevant to drug development.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- miBrain Platform: Multicellular Integrated Brains derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. Contains all six major human brain cell types: neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and vasculature [6].

- Customizable Hydrogel Neuromatrix: Polysaccharides, proteoglycans, and basement membrane blend mimicking brain's ECM [6].

- Cell Type Proportions: Experimentally determined balance for functional neurovascular units (reference: ~45-75% oligodendroglia, 19-40% astrocytes) [6].

- Genetic Editing: CRISPR/Cas9 tools for introducing disease-relevant variants (e.g., APOE4) [6].

Procedure:

- Model Generation: Generate miBrains from donor iPSCs, differentiating all six major cell types separately before combination in the optimized neuromatrix at validated ratios to form self-assembling, functioning units with blood-brain-barrier characteristics [6].

- Experimental Manipulation:

- Isolated Cell Type Effects: Integrate specific disease-variant cell types (e.g., APOE4 astrocytes) into otherwise wild-type (APOE3) assemblies to isolate cellular contributions to network-level dysfunction [6].

- Pharmacological Modulation: Administer pipeline therapeutic agents (from Table 2) at clinically relevant concentrations.

- Circuit Perturbation: Use optogenetic/chemogenetic tools to manipulate specific cellular populations while recording network activity.

- Functional Readouts:

- Calcium Imaging: Monitor spatiotemporal activity patterns across the miBrain network at cellular resolution.

- Multi-electrode Arrays: Record electrophysiological signatures of network function.

- Molecular Sampling: Collect medium for biomarker analysis (e.g., amyloid-beta, phosphorylated tau, inflammatory cytokines).

- HOI Analysis Application:

- Apply Protocol 1 to calcium imaging and electrophysiology time series data extracted from miBrain recordings.

- Identify HOI signatures that correlate with molecular pathology (e.g., amyloid accumulation, tau phosphorylation).

- Test if therapeutic interventions normalize specific HOI signatures toward wild-type patterns.

- Validate that HOI signatures require specific cellular interactions (e.g., by demonstrating that APOE4 astrocyte-induced tau pathology requires microglial cross-talk) [6].

- Biomarker Validation: Correlate specific HOI signatures from miBrains with human fMRI-based HOI patterns and cognitive measures to establish translational relevance for clinical trials.

Visualization of HOI Analytical Workflows

Higher-Order Connectomics Analysis Pipeline

Experimental Validation Pathway for Drug Development

The abstraction of the human connectome has evolved from traditional graph-based models, which represent pairwise interactions between brain regions, toward more sophisticated mathematical frameworks capable of capturing higher-order interactions (HOIs) that involve three or more regions simultaneously [1]. This paradigm shift is driven by mounting evidence that significant information about brain function exists in the joint probability distributions of neural activity that cannot be detected in pairwise marginals alone [1]. The limitations of traditional network analysis have prompted the adoption of three principal mathematical frameworks: hypergraphs, which represent group interactions as hyperedges connecting multiple nodes; simplicial complexes, which provide a combinatorial topology by grouping nodes into simplices of varying dimensions; and topological invariants, which offer quantitative descriptors of the shape and structure of neural data across multiple scales [7] [8]. These frameworks enable researchers to move beyond the constraints of dyadic connectivity and uncover a vast space of previously unexplored structures within human functional brain data [1].

The application of these mathematical frameworks to neuroimaging data, particularly fMRI time series, has demonstrated substantial advantages over traditional approaches. Higher-order methods have been shown to significantly enhance dynamic task decoding, improve individual identification of functional subsystems, and strengthen associations between brain activity and behavior [1] [9]. Furthermore, topological approaches provide a multiscale analysis framework that remains robust against the choice of threshold parameters that often plague conventional graph-theoretical measures [10]. This document provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers seeking to implement these advanced mathematical frameworks in their connectomics research, with detailed protocols, analytical workflows, and validation metrics specifically tailored for the analysis of higher-order brain function.

Core Mathematical Frameworks: Definitions and Comparative Analysis

Formal Definitions and Properties

Simplicial Complexes: A simplicial complex is a set of simplices that satisfies two conditions: every face of a simplex from the complex is also in the complex, and the non-empty intersection of any two simplices is a shared face [7]. Formally, a k-simplex σₖ is a convex hull of k+1 affinely independent points u₀, u₁, ..., uₖ ∈ ℝᵏ: σₖ = {θ₀u₀ + ⋯ + θₖuₖ | ∑θᵢ = 1, θᵢ ≥ 0} [7]. In neuroscience applications, a 0-simplex represents a brain region (node), a 1-simplex represents a connection between two regions (edge), a 2-simplex represents a triangle among three regions, and so on. The order of a simplicial complex is given by the order of its largest clique, with q_max representing the highest order interaction present [8].

Hypergraphs: A hypergraph H = (V, E) consists of a set of vertices V (brain regions) and a set of hyperedges E, where each hyperedge is a non-empty subset of V. Unlike simplicial complexes, hypergraphs do not require the downward closure property - every subset of a hyperedge does not necessarily need to be included as a hyperedge. This flexibility allows hypergraphs to represent arbitrary group interactions without the combinatorial constraints of simplicial complexes.

Topological Invariants: Persistent homology tracks the evolution of topological features across multiple scales through a process called filtration [7]. The most commonly used invariants in connectomics are the Betti numbers: β₀ counts the number of connected components, β₁ counts the number of 1-dimensional cycles (loops), and β₂ counts the number of 2-dimensional voids (cavities) [11]. These invariants are robust to continuous deformations and provide a multiscale descriptor of the topological structure of brain networks.

Quantitative Comparison of Mathematical Frameworks

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Mathematical Frameworks for Higher-Order Connectomics

| Framework | Maximum Order Demonstrated in Brain Networks | Key Advantages | Computational Complexity | Primary Applications in Connectomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplicial Complexes | 6th order (tetrahedrons and beyond) [8] | Built-in hierarchical structure; direct connection to algebraic topology | O(2ⁿ) in worst case for n nodes | Mapping clique complexes; analyzing rich-club organization [8] |

| Hypergraphs | Not specified in results | Flexible representation of arbitrary group interactions | O(nᵏ) for k-uniform hypergraphs | Modeling non-clique group interactions; functional polyadic relationships [11] |

| Topological Invariants | 2nd order (H₂) homology commonly computed [11] | Multiscale analysis; robustness to noise and thresholds | O(n³) for persistent homology | Brain state classification; fingerprinting; genetic studies [10] |

Table 2: Topological Signatures of Brain States Identified Through Higher-Order Approaches

| Brain State | Higher-Order Topological Signature | Detection Method | Performance Advantage Over Pairwise Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Task | Distinct H₀ and H₁ homological distances [11] | Homological kernel analysis | Reveals self-similarity property between rest and motor tasks [11] |

| Emotion Task | Prominent H₁ homological signature [11] | Wasserstein distance between persistence diagrams | Identifies task-specific higher-order coordination patterns |

| Working Memory Task | Significant H₂ homological signature [11] | Multi-order homological analysis | Captures complex interactions missed by lower-order models |

| Resting State | Default mode network prominence at H₁ and H₂ scaffolds [11] | Functional sub-circuit consolidation | Reveals network-specific higher-order architecture |

Topological Processing Workflow for fMRI Data

Protocol: Higher-Order Topological Analysis of fMRI Time Series

Purpose: To extract higher-order topological signatures from fMRI data that capture interactions among three or more brain regions simultaneously, enabling improved task decoding, individual identification, and behavior association.

Materials and Equipment:

- fMRI data (e.g., from Human Connectome Project)

- Computational resources (minimum 16GB RAM for whole-brain analysis)

- Software: MATLAB, Python (with specialized libraries for TDA)

- Brain parcellation atlas (e.g., 100 cortical + 19 subcortical regions [1])

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize all original fMRI signals through z-scoring [1]

- Apply necessary preprocessing steps: head movement correction, temporal filtering

Compute k-Order Time Series:

- Calculate all possible k-order time series as element-wise products of k+1 z-scored time series

- For each resulting k-order time series, apply an additional z-scoring for cross-k-order comparability

- Assign a sign to each k-order time series at each timepoint based on parity rule: positive for fully concordant group interactions, negative for discordant interactions [1]

Construct Weighted Simplicial Complexes:

- For each timepoint t, encode all instantaneous k-order co-fluctuation time series into a weighted simplicial complex

- Define the weight of each simplex as the value of the associated k-order time series at timepoint t [1]

Extract Topological Indicators:

- Apply computational topology tools to analyze simplicial complex weights at each timepoint

- Extract two global indicators: hyper-coherence (fraction of higher-order triplets that co-fluctuate beyond pairwise expectations) and coherent/decoherent contributions [1]

- Extract two local indicators: violating triangles (Δv) and homological scaffolds [1]

Construct Recurrence Plots:

- For local methods (BOLD, edges, triangles, scaffold signals), construct recurrence plots by computing time-time correlation matrices

- Binarize matrices at the 95th percentile of their respective distributions [1]

Community Detection and Task Decoding:

- Apply Louvain algorithm to identify communities in recurrence plots

- Evaluate task identification performance using element-centric similarity (ECS) measure [1]

Validation and Quality Control:

- Compare higher-order approach performance against traditional pairwise methods across three domains: task decoding, individual identification, and behavior association [1]

- Verify that local higher-order indicators outperform traditional node and edge-based methods [1]

Troubleshooting:

- If computational demands are too high, consider reducing the number of brain regions in parcellation

- If signal-to-noise ratio is low, increase the number of timepoints in analysis

Figure 1: Topological data analysis workflow for extracting higher-order signatures from fMRI data. The pipeline transforms raw time series into simplicial complexes and extracts topological indicators that capture multi-region interactions.

Protocol: Persistent Homology for State-Space Estimation

Purpose: To identify and characterize distinct topological states in dynamically changing functional brain networks using persistent homology and Wasserstein distance metrics.

Materials and Equipment:

- Resting-state fMRI data (minimum 5 minutes acquisition recommended)

- MATLAB with PH-STAT toolbox (publicly available [10])

- High-performance computing resources for large distance matrices

Procedure:

Network Construction:

- Parcellate brain into regions of interest (116 regions with AAL template recommended [7])

- Compute functional connectivity matrices using Pearson correlation between regional time series

Graph Filtration:

- Construct a sequence of nested graphs over a range of correlation thresholds

- Track birth and death of topological features (connected components, cycles) during filtration [7]

Persistence Diagram Computation:

- Generate persistence diagrams encoding the birth-death scales of topological features

- Separate diagrams by dimension: H₀ (components), H₁ (cycles), H₂ (voids)

Wasserstein Distance Calculation:

- Compute pairwise Wasserstein distances between all persistence diagrams

- This quantifies topological differences between brain networks [10]

Topological Clustering:

- Apply clustering algorithms to Wasserstein distance matrix to identify recurrent brain states

- Validate clusters using silhouette analysis and stability measures

Heritability Analysis (for twin studies):

- Compare topological state dynamics between monozygotic and dizygotic twins

- Quantify heritability of topological features using intraclass correlations [10]

Validation:

- Compare performance against k-means clustering applied to raw connectivity matrices [10]

- Verify that topological clustering captures genetically influenced patterns in twin designs [10]

Application Contexts and Experimental Validation

Task Decoding and Functional Fingerprinting

Higher-order topological approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in decoding cognitive tasks from fMRI data. In comparative studies, local higher-order indicators significantly outperformed traditional node and edge-based methods in identifying the timing of task and rest blocks [1]. The element-centric similarity (ECS) measure, which quantifies how well community partitions identify task timings, approached 1 for higher-order methods compared to substantially lower values for pairwise approaches [1].

The homological scaffolds derived from simplicial complexes have proven particularly effective for functional brain fingerprinting, enabling individual identification based on unique topological patterns in unimodal and transmodal functional subsystems [1]. This suggests that an individual's higher-order functional architecture contains distinctive features that remain consistent across time, potentially serving as reliable biomarkers for personalized neuroscience applications.

Figure 2: Homological scaffold construction process. The filtration tracks topological feature persistence across scales, generating diagrams that distinguish robust features from noise, enabling individual identification and task decoding.

Behavioral and Genetic Correlates

Higher-order interactions in brain networks demonstrate significantly stronger associations with behavior compared to traditional pairwise connectivity measures [1]. The topological complexity captured through simplicial complexes and persistent homology provides more sensitive markers of individual differences in cognitive performance and behavioral traits.

In genetic studies, topological state changes in functional brain networks have shown heritable components, with monozygotic twins demonstrating greater similarity in their dynamic topological patterns compared to dizygotic twins [10]. This suggests that the higher-order organization of brain function is influenced by genetic factors, opening new avenues for understanding the genetic underpinnings of brain dynamics and their relationship to cognition and behavior.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Higher-Order Connectomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCP Dataset | Provides high-quality fMRI data for method validation | 100+ unrelated subjects; resting-state and 7 tasks; 1200 time points [1] [7] | Publicly available via NDA |

| AAL Atlas | Standardized brain parcellation for node definition | 116 anatomical regions; reproducible partitioning [7] | Publicly available |

| Yeo Functional Networks | A priori functional sub-circuits for mesoscopic analysis | 7 resting-state networks; enables sub-circuit analysis [11] | Publicly available |

| PH-STAT Toolbox | Implements persistent homology state-space estimation | MATLAB-based; Wasserstein distance computation [10] | GitHub repository |

| Budapest Connectome Server | Generates consensus connectomes for population analysis | Creates group-common networks; sex-specific comparisons [8] | Web interface |

| Graph Filtration Algorithms | Constructs nested graph sequences for persistent homology | Multi-scale topology analysis; Betti number computation [7] | Custom implementation |

Traditional models of human brain function have predominantly represented neural activity as a network of pairwise interactions between brain regions, a limitation that fails to capture the complex, group-level dynamics that define cognition [12]. Higher-order interactions (HOIs) represent simultaneous interactions between three or more neural elements and are critical for characterizing the brain's complex spatiotemporal dynamics [12] [13]. These interactions can be broadly characterized as either redundant or synergistic, terms derived from multivariate information theory that describe how information is shared across multiple brain regions [13].

Understanding this distinction is fundamental: redundant interactions occur when the same information is copied across regions, enhancing robustness, whereas synergistic interactions represent emergent information present only in the joint activity of the group, supporting complex computation and cognitive flexibility [13] [14]. Mounting evidence confirms that methods relying on pairwise statistics alone are insufficient, as significant information remains detectable only in joint probability distributions and not in pairwise marginals [12]. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for capturing these higher-order dynamics, framed within the advancing field of higher-order connectomics.

Application Notes: The Functional Advantage of HOIs

Key Advantages Over Pairwise Methods

Empirical studies demonstrate that higher-order approaches substantially enhance our ability to decode cognitive tasks, improve individual identification of functional subsystems, and strengthen the association between brain activity and behavior [12]. The following table summarizes the quantitative advantages of higher-order approaches as established in recent literature.

Table 1: Functional Advantages of Higher-Order Connectomics Methods

| Application Domain | Key Finding | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Task Decoding | Higher-order approaches greatly enhance the ability to decode dynamically between various tasks [12]. | Analysis of fMRI time series from 100 unrelated subjects from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) [12]. |

| Brain Fingerprinting | Improved individual identification of unimodal and transmodal functional subsystems [12]. | Local higher-order indicators provided improved functional brain fingerprinting based on local topological structures [12]. |

| Behavioral Prediction | Significantly stronger associations between brain activity and behavior [12]. | Strengthened brain-behavior relationships were observed using higher-order local topological indicators [12]. |

| Learning & Information Encoding | Information gain in goal-directed learning is encoded by distributed, synergistic higher-order interactions [14]. | MEG study showing IG encoded synergistically at the level of triplets and quadruplets, centered on ventromedial/orbitofrontal cortices [14]. |

Synergy and Redundancy Dynamics

The dynamic balance between synergy and redundancy is a hallmark of healthy brain function. Analysis of resting-state fMRI has revealed that the whole brain is strongly redundancy-dominated, with some subjects never experiencing a whole-brain synergistic moment [13]. However, smaller subsets of regions exhibit complex dynamic behavior, fluctuating between highly synergistic and highly redundant states [13]. Crucially, synergistic interactions, though less robust than redundant ones, are thought to be highly relevant to information modification and computation in complex systems [13].

These dynamics are not merely epiphenomenal; they are clinically significant. Synergistic interactions are implicated in various clinical conditions, including Alzheimer's disease, stroke recovery, schizophrenia, and Autism Spectrum Disorder, and are clinically manipulable through interventions like transcranial ultrasound stimulation [13]. Furthermore, the presence of synergistic structures in infant EEG is predictive of later cognitive development [13].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for inferring and analyzing higher-order interactions from neuroimaging data.

Protocol 1: Topological Inference of Instantaneous HOIs from fMRI

This protocol, adapted from [12], infers time-resolved higher-order interactions from fMRI BOLD signals using computational topology.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Acquire fMRI time series (e.g., from the Human Connectome Project) [12].

- Perform standard preprocessing: global signal regression, band-pass filtering (e.g., 0.008 Hz to 0.08 Hz), and removal of initial and final time points to stabilize signals [13].

- Parcellate the brain into regions of interest (e.g., 100 cortical and 19 subcortical regions) [12].

- Standardize each of the N original fMRI signals through z-scoring [12].

Computation of k-Order Time Series:

- For each time point, compute all possible k-order time series as the element-wise products of k+1 z-scored time series.

- For example, a 2-order time series (representing a triplet interaction) is the product of three z-scored regional time series.

- Z-score the resulting k-order time series for cross-k-order comparability.

- Assign a sign to each k-order time series at each time point based on parity: positive for fully concordant group interactions (all node time series have positive or all have negative values), and negative for discordant interactions (a mixture of positive and negative values) [12].

Construction of Simplicial Complex:

- For each time point t, encode all instantaneous k-order time series into a single mathematical object: a weighted simplicial complex.

- A 0-simplex represents a brain region, a 1-simplex an edge (pairwise interaction), a 2-simplex a triangle (triplet interaction), and so on.

- Define the weight of each simplex as the value of its associated k-order time series at time t [12].

Extraction of Higher-Order Indicators:

- Apply computational topology tools (e.g., persistent homology) to the weighted simplicial complex at each time t.

- Local Indicators: Use the list and weights of "violating triangles" (Δv)—triangles that co-fluctuate more than expected from their pairwise edges—and the "homological scaffold," a weighted graph highlighting the importance of edges to mesoscopic topological structures [12].

- Global Indicators: Calculate metrics like "hyper-coherence," which quantifies the fraction of higher-order triplets that co-fluctuate beyond pairwise expectations [12].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Time-Varying Synergy/Redundancy Dominance

This protocol details the use of the local O-information to track the moment-to-moment balance between synergistic and redundant higher-order interactions from fMRI data [13].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedure:

Data Preparation:

Subset Selection:

- Define subsets of brain regions for analysis. This can range from small sets (e.g., 3-5 regions) that may belong to a single functional network, to larger sets (e.g., 7+ regions) that necessarily span multiple networks [13].

Calculation of Local O-Information:

- The O-information is a scalable heuristic measure of redundancy/synergy dominance in a multivariate system [13].

- Calculate the local O-information for each specific state of the system at every time point t. This provides a time-resolved measure of synergy/redundancy dominance, as the system enters a new state with each TR [13].

- A negative local O-information value indicates a synergistic-dominant interaction at time t, while a positive value indicates a redundancy-dominant interaction.

Dynamic Analysis:

- Analyze the resulting time series of local O-information to identify moments of peak synergy or redundancy.

- Investigate the autocorrelation and recurrence of these states to uncover temporal structure.

- Relate these temporal patterns back to the co-fluctuation patterns of the individual brain regions involved to understand the nodal activity underlying synergistic or redundant states [13].

The following table contrasts the two primary methodologies outlined above, highlighting their distinct theoretical foundations and analytical outputs.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Protocols for Higher-Order Connectomics

| Protocol Feature | Topological Inference (Protocol 1) | Local O-Information (Protocol 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Computational Topology & Simplicial Complexes [12] | Multivariate Information Theory [13] |

| Primary Output | Instantaneous higher-order co-fluctuation patterns (e.g., violating triangles) [12] | Time-varying synergy/redundancy dominance metric [13] |

| Key Strength | Provides a geometrically intuitive map of HOI structures; excels at task decoding and fingerprinting [12] | Directly quantifies the informational character (synergy vs. redundancy) of HOIs; reveals dynamic balance [13] |

| Data Input | fMRI time series [12] | fMRI time series [13] |

| Clinical/Cognitive Link | Strongly associated with behavior and task performance [12] | Implicated in consciousness, cognitive development, and various neurological disorders [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section catalogs essential computational tools and data resources for conducting higher-order connectomics research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Higher-Order Connectomics

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Dataset | Data Resource | Provides high-quality, minimally preprocessed fMRI, dMRI, and MEG data from healthy adult twins and non-twin siblings [12] [13]. | Serves as a primary data source for methodology development and validation; includes resting-state and task data [12]. |

| Gephi / Gephi Lite | Visualization Software | An open-source platform for network visualization and exploration. Used for visualizing and manipulating graph representations of connectomes [15] [16]. | Enables interactive exploration of network structure; supports various layout algorithms and community detection [16]. |

| Cytoscape | Visualization & Analysis Software | A powerful open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating with attribute data [15] [16]. | Highly customizable via apps; ideal for producing publication-quality visualizations and performing specialized analyses [16]. |

| NetworkX | Software Library (Python) | A standard Python library for the creation, manipulation, and study of the structure, dynamics, and functions of complex networks [16]. | Provides the foundational data structures and algorithms for building custom network analysis pipelines. |

| iGraph | Software Library (R/Python) | A efficient network analysis library collection for R, Python, and C/C++ [16]. | Known for fast processing of large graphs; a strong alternative to NetworkX for performance-critical applications [16]. |

| Local O-Information Calculator | Computational Tool | Implements the algorithm for calculating time-varying synergy and redundancy dominance from multivariate time series data [13]. | Can be implemented in-house based on published mathematical formulations [13]. |

From Theory to Practice: Computational Tools and Workflows for Mapping Complex Brain Interactions

The intricate functional organization of the human brain extends beyond simple pairwise connections to encompass complex higher-order interactions (HOIs) that simultaneously involve multiple brain regions [1]. Traditional network models of brain function, which represent interactions as strictly pairwise connections, fundamentally limit our understanding of this sophisticated higher-order organizational structure [17] [1]. Topological Data Analysis (TDA) has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for characterizing these complex relationships by providing quantifiable measures for capturing, understanding, and analyzing the 'shape' of high-dimensional neuroimaging data [18]. This application note details a comprehensive TDA pipeline that transforms fMRI time series into weighted simplicial complexes, enabling researchers to extract meaningful higher-order topological features for brain disorder diagnosis, task decoding, and individual identification [17] [1]. By moving beyond traditional pairwise connectivity approaches, this pipeline offers unprecedented insights into the higher-order organizational principles of human brain function, with significant implications for neuroscience research and clinical drug development.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Table 1: Core Concepts in Topological Data Analysis for fMRI

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Neurobiological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) | Simultaneous interactions among k+1 brain regions (k ≥ 2) | Group-wise neural co-fluctuations beyond pairwise connectivity that may represent functional assemblies [17] [1] |

| Weighted Simplicial Complex | Collection of simplices (nodes, edges, triangles, tetrahedra) with assigned weights | Comprehensive representation of brain connectivity incorporating both pairwise and higher-order relationships with interaction strengths [17] |

| Persistent Homology | Algebraic method tracking topological features across multiple scales | Technique for identifying robust higher-dimensional neural organizational patterns (connected components, cycles, voids) in brain data [17] [18] |

| Persistence Landscapes | Vectorized summaries of persistence diagrams | Stable topological descriptors suitable for statistical analysis and machine learning applications [18] |

| Multiplication of Temporal Derivatives (MTD) | Element-wise product of temporal derivatives of BOLD signals | Novel metric for quantifying dynamic functional co-fluctuations across group-level brain regions with adequate temporal resolution [17] |

Computational Workflow

The transformation of fMRI time series to weighted simplicial complexes involves a multi-stage computational workflow that extracts higher-order topological features from BOLD signal data.

Figure 1: Computational workflow for transforming fMRI time series into topological features via weighted simplicial complexes. The pipeline begins with raw fMRI data, progresses through signal preprocessing and higher-order interaction detection, constructs topological representations, and culminates in analytical features for downstream applications.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

fMRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Table 2: Data Acquisition Parameters for Higher-Order Connectomics

| Parameter | Recommended Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Scanner Field Strength | 3T or higher | Optimize BOLD signal-to-noise ratio [19] |

| Temporal Resolution (TR) | ≤ 1 second | Capture neural co-fluctuation dynamics [17] |

| Spatial Resolution | 2-3 mm isotropic | Balance whole-brain coverage with regional specificity [1] |

| Parcellation Scheme | AAL3 (100-200 regions) [20] | Standardize region of interest (ROI) definition |

| Task Design | Resting-state and task-based fMRI [1] [19] | Enable comparison across cognitive states |

| BOLD-Filter Application | Preprocessing step for task-based fMRI [19] | Enhance isolation of task-evoked BOLD signals |

Protocol Steps:

Data Acquisition: Acquire fMRI data using standardized protocols from initiatives such as the Human Connectome Project (HCP) [1] [21]. For task-based fMRI, employ paradigms that engage specific functional networks during cognitive or behavioral tasks [19].

Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing pipelines including slice-time correction, motion correction, spatial normalization, and band-pass filtering. For task-based fMRI, implement the BOLD-filter method to substantially improve isolation of task-evoked BOLD signals, identifying over eleven times more activation voxels at high statistical thresholds [19].

Signal Standardization: Z-score each regional BOLD time series to ensure comparability across regions and participants: ( Z(t) = \frac{BOLD(t) - \mu}{\sigma} ) where ( \mu ) is the mean and ( \sigma ) is the standard deviation of the BOLD signal [1].

Higher-Order Interaction Detection

Multiplication of Temporal Derivatives (MTD) Calculation:

Compute temporal derivatives for each ROI's BOLD signal: ( Di(t) = BOLDi(t) - BOLD_i(t-1) ) [17]

Calculate k-order MTD for groups of (k+1) ROIs as the element-wise product of their temporal derivatives: ( MTD{i,j,...,k}(t) = Di(t) \times Dj(t) \times \cdots \times Dk(t) ) [17]

The resulting MTD time series represents the instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitude for (k+1)-node interactions at each timepoint.

Signed Interaction Classification:

Positively Synergistic Interactions: Classify when multiple brain regions exhibit simultaneous activation at a given moment relative to the preceding one [17].

Negatively Synergistic Interactions: Classify when regions collectively exhibit inhibition at the current moment compared to the prior moment [17].

Weighted Simplicial Complex Construction

Figure 2: Construction of weighted simplicial complexes from fMRI time series. The process involves calculating interaction time series at different orders (edges, triangles, tetrahedrons), assigning signs based on signal concordance, and assembling these into a comprehensive topological representation of brain connectivity.

Protocol Steps:

k-order Time Series Calculation: For each timepoint t, compute all possible k-order time series as the element-wise products of k+1 z-scored BOLD signals. For example:

- 1-order (edges): ( E{ij}(t) = Zi(t) \times Z_j(t) )

- 2-order (triangles): ( T{ijk}(t) = Zi(t) \times Zj(t) \times Zk(t) ) [1]

Sign Assignment: Assign signs to each k-order interaction at each timepoint based on strict parity rules:

- Positive: Fully concordant group interactions (all regional BOLD signals have positive or all have negative values at that timepoint)

- Negative: Discordant interactions (a mixture of positive and negative values across regions) [1]

Complex Construction: Encode all instantaneous k-order time series into a monotonic weighted simplicial complex, where:

- Nodes (0-simplices) represent brain regions

- Edges (1-simplices) represent pairwise interactions

- Triangles (2-simplices) represent triplet interactions

- Tetrahedra (3-simplices) represent quadruplet interactions [17]

Weight Assignment: Assign weights to each simplex based on the value of the associated k-order time series at each timepoint, creating a time-varying topological representation of brain connectivity [1].

Persistent Homology Analysis

Protocol Steps:

Filtration: Construct a filtration of the weighted simplicial complex by thresholding across the range of weights, adding simplices as the threshold increases [17] [18].

Persistence Diagram Generation: At each filtration step, apply computational topology tools to extract topological features (connected components, cycles, voids) and record their birth and death parameters [18].

Persistence Landscape Conversion: Transform persistence diagrams to persistence landscapes, which are vectorized topological descriptors suitable for statistical analysis and machine learning: ( Lk(t) = \lambdak(t) ) where ( \lambda_k ) is the k-th largest persistence value [18].

Feature Extraction: Identify "violating triangles" - higher-order triplets that co-fluctuate more than expected from corresponding pairwise co-fluctuations - which represent irreducible higher-order interactions [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Specification | Application in Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI Datasets | HCP (100 unrelated subjects) [1], OASIS, ADNI [20] | Validation and benchmarking of topological methods |

| Parcellation Atlas | AAL3 (100 cortical, 19 subcortical regions) [1] [20] | Standardized ROI definition for reproducible complex construction |

| Topological Software | JavaPlex, GUDHI, Ripser | Persistent homology computation and persistence diagram generation |

| BOLD-Filter Method | Preprocessing technique for task-based fMRI [19] | Enhanced isolation of task-evoked BOLD signals |

| MTD Metric | Multiplication of Temporal Derivatives [17] | Quantification of dynamic functional co-fluctuations with high temporal resolution |

| Multi-channel Transformers | Architecture for integrating heterogeneous topological features [17] | Holistic information integration from lower and higher-order features |

Applications and Validation

Table 4: Performance Validation of TDA Pipeline Across Brain Disorders

| Application Domain | Dataset | Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) Diagnosis | OASIS, ADNI [20] | Accurate identification of key higher-order organizational patterns [17] | Concordant HOIs weakening in AD brain compared to healthy controls [17] |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Multi-site datasets | Effective differentiation from neurotypical controls [17] | Revealed characteristic HOI reductions in ASD patients [17] |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Parkinson's progression markers initiative | Successful classification of disease stages [17] | Detected opposite trend: enhanced concordant HOIs in PD [17] |

| Task Decoding | HCP (100 subjects) [1] | Superior task identification using element-centric similarity (ECS) measures [1] | Local higher-order indicators outperformed traditional node and edge-based methods [1] |

| Individual Identification | HCP (100 subjects) [1] | Improved functional brain fingerprinting [1] | Strengthened association between brain activity and behavior [1] |

The TDA pipeline demonstrates particular strength in clinical applications, showing consistently weakened concordant higher-order interactions in Alzheimer's disease and autism spectrum disorder, while revealing an opposite trend of enhancement in Parkinson's disease [17]. These disease-specific topological signatures offer mechanistic insights into brain disorders and present potential neuroimaging biomarkers for drug development.

For cognitive neuroscience applications, higher-order approaches significantly enhance task decoding capabilities, improving the characterization of dynamic group dependencies in both resting-state and task-based conditions [1]. The method also strengthens the association between brain activity and behavior, providing a more comprehensive understanding of brain-behavior relationships.

This application note has detailed a comprehensive TDA pipeline for transforming fMRI time series into weighted simplicial complexes, enabling researchers to extract and analyze higher-order interactions in human brain function. The protocol provides:

- Standardized Methodologies for consistent implementation across research sites

- Quantitative Validation across multiple brain disorders and cognitive states

- Clinically Relevant Biomarkers for diagnostic applications and treatment monitoring

- Computational Tools for reproducible higher-order connectomics research

The pipeline represents a fundamental shift from traditional pairwise connectivity approaches, revealing a vast space of unexplored structures within human functional brain data that may remain hidden when using conventional methods [1]. By providing detailed protocols and validation metrics, this framework enables researchers and drug development professionals to leverage higher-order topological analytics in their investigations, potentially accelerating the discovery of novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The study of brain networks, or connectomics, has traditionally relied on models that represent interactions as pairwise connections between regions. While this approach has been fruitful, it possesses a fundamental limitation: the inability to directly assess interactions involving three or more elements simultaneously [22]. This limitation holds significant implications for understanding higher-order brain functions such as thought, language, and complex cognition, which likely emerge from intricate, multi-regional collaborations [9].

Information theory provides a powerful mathematical framework to move beyond pairwise descriptions. This set of notes details the application of three key information-theoretic quantifiers—O-Information, Total Correlation, and Partial Entropy Decomposition (PED)—within human brain function research. These tools allow researchers to rigorously quantify the higher-order statistical dependencies that are invisible to standard network analyses, opening a vast space of unexplored structures in human brain data [22] [1]. Their application is poised to enhance our understanding of brain dynamics, improve individual identification, and strengthen the association between brain activity and behavior [1].

Theoretical Foundations and Quantifier Definitions

Total Correlation

Total Correlation (TC), also known as multi-information, is a generalization of mutual information for more than two variables. It quantifies the total amount of shared information—both redundant and synergistic—within a set of variables. For a set of ( n ) random variables ( \mathbf{X} = {X1, X2, ..., X_n} ), TC is defined as the sum of the individual entropies minus the joint entropy:

[ TC(\mathbf{X}) = \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi) - H(\mathbf{X}) ]

Where ( H(Xi) ) is the Shannon entropy of variable ( Xi ), and ( H(\mathbf{X}) ) is the joint entropy of the entire set. A high TC value indicates that the variables in the set share a substantial amount of information.

O-Information

O-Information (OI) extends the concept of TC to specifically characterize the nature of higher-order interactions—distinguishing between redundancy and synergy [22]. It is defined as:

[ \Omega(\mathbf{X}) = TC(\mathbf{X}) - \sum{i=1}^{n} TC(\mathbf{X}{-i}) ]

Where ( \mathbf{X}_{-i} ) denotes the set excluding the ( i )-th variable. Intuitively, OI measures the balance between synergistic and redundant dependencies.

- Positive Ω indicates a system dominated by redundancy, where the same information is duplicated across multiple elements.

- Negative Ω indicates a system dominated by synergy, where information is only accessible through the joint state of multiple elements and cannot be reduced to simpler combinations.

Partial Entropy Decomposition

The Partial Entropy Decomposition (PED) framework provides a granular decomposition of the joint entropy of a system into non-negative atoms that describe all possible information-sharing relationships among its constituents [22]. For a system of variables, PED dissects the joint entropy ( H(\mathbf{X}) ) into a sum of partial entropy atoms ( \mathcal{H}_{\partial} ), each representing a distinct mode of information sharing:

[ H(\mathbf{X}) = \sum{\alpha \in \mathcal{A}} \mathcal{H}{\partial}(\alpha) ]

These atoms describe the redundant, unique, and synergistic interactions that compose the system's structure [22]. For example, in a bivariate system ( {X1, X2} ), the joint entropy decomposes into:

- ( \mathcal{H}{\partial}^{12}({1}{2}) ): Redundant information shared between ( X1 ) and ( X_2 ).

- ( \mathcal{H}{\partial}^{12}({1}) ): Unique information present only in ( X1 ).

- ( \mathcal{H}{\partial}^{12}({2}) ): Unique information present only in ( X2 ).

- ( \mathcal{H}{\partial}^{12}({1,2}) ): Synergistic information that is only available when ( X1 ) and ( X_2 ) are observed together.

Table 1: Summary of Core Information-Theoretic Quantifiers

| Quantifier | Mathematical Definition | Primary Interpretation in Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|

| Total Correlation (TC) | ( TC(\mathbf{X}) = \sum{i=1}^{n} H(Xi) - H(\mathbf{X}) ) | Total shared information (redundant + synergistic) within an ensemble of brain regions. |

| O-Information (OI) | ( \Omega(\mathbf{X}) = TC(\mathbf{X}) - \sum{i=1}^{n} TC(\mathbf{X}{-i}) ) | Balance of information sharing: Ω > 0 = Redundancy; Ω < 0 = Synergy. |

| Partial Entropy Decomposition (PED) | ( H(\mathbf{X}) = \sum{\alpha} \mathcal{H}{\partial}(\alpha) ) | Fine-grained decomposition of all information-sharing modes (redundant, unique, synergistic). |

Applications in Higher-Order Connectomics

The application of these quantifiers to neuroimaging data, particularly fMRI, is revealing fundamental new principles of brain organization.

Widespread Higher-Order Interactions in Resting-State Dynamics

Applying PED to resting-state fMRI data has provided robust evidence of widespread synergistic information that is largely invisible to standard functional connectivity analyses [22]. This finding challenges the traditional network model, suggesting that the brain's functional architecture is composed of complex, higher-order dependencies that cannot be captured by pairs of regions alone. Furthermore, these structures are dynamic, with ensembles of regions transiently changing from being redundancy-dominated to synergy-dominated in a temporally structured pattern [22].

Enhanced Task Decoding and Individual Identification

A comprehensive analysis of fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project demonstrated that higher-order approaches, including those leveraging inferred higher-order interactions, significantly outperform traditional pairwise methods [1] [23]. Specifically, local topological signatures derived from higher-order co-fluctuations greatly enhance the ability to dynamically decode various cognitive tasks from fMRI signals. Moreover, these higher-order features provide a more unique "fingerprint" for individual identification, improving upon the discriminative power of functional connectivity based solely on pairwise correlations [1] [9].

Strengthened Brain-Behavior Associations

The same higher-order descriptors that improve task decoding also strengthen the association between brain activity and behavior [1]. This suggests that by capturing more complex neural interactions, information-theoretic quantifiers provide a more accurate and comprehensive model of the neural underpinnings of behavior and cognition.

Tracking Feature-Specific Information Flow

Beyond characterizing static structure, information theory can track the content of communication. The recently developed Feature-specific Information Transfer (FIT) measure quantifies how much information about a specific feature (e.g., a sensory stimulus) flows between two regions [24] [25]. FIT merges the Granger-causality principle with Partial Information Decomposition (PID) to isolate, within the total information flow, the part that is specifically about a feature of interest. This allows researchers to move beyond asking "Are two regions communicating?" to the more nuanced question, "What information are they communicating?" [24].

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from Higher-Order fMRI Studies

| Experimental Context | Finding | Implication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-State Analysis | Robust evidence of widespread, dynamic higher-order synergies. | Standard pairwise FC models are incomplete; a vast space of unexplored structure exists. | [22] |

| Task Decoding | Higher-order methods greatly enhance dynamic decoding between various tasks. | HOIs are crucial for supporting and distinguishing cognitive processes. | [1] [23] |

| Individual Identification | Higher-order features provide improved "brain fingerprinting." | Individual neuro-id is better achieved with HOIs than with pairwise connectivity. | [1] [9] |

| Brain-Behavior Link | HOIs significantly strengthen associations between brain activity and behavior. | HOIs provide a more valid neural substrate for behavioral and cognitive functions. | [1] |

Experimental Protocols

This section outlines a generalized workflow for computing higher-order information-theoretic measures from fMRI data.

Protocol: A Generalized Workflow for Higher-Order Information-Theoretic Analysis of fMRI Data

Objective: To quantify redundancy, synergy, and other higher-order statistical dependencies in functional brain networks using fMRI BOLD time series.

I. Data Acquisition & Preprocessing

- fMRI Data: Acquire resting-state or task-based BOLD fMRI data. A large sample size (e.g., n > 100) is recommended for robust statistical power. Publicly available datasets like the Human Connectome Project (HCP) are suitable [1].

- Preprocessing: Standard preprocessing pipelines should be applied. This typically includes:

- Slice-timing correction

- Motion realignment and regression

- Coregistration to structural images

- Spatial normalization to a standard template (e.g., MNI)

- Band-pass filtering (e.g., 0.01-0.1 Hz)

- Nuisance regression (e.g., white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, global signal)

- Parcellation: Parcellate the preprocessed fMRI data into N regions of interest (ROIs) using a standardized atlas (e.g., AAL, Yeo-17, Brainnetome). This yields an ( N \times T ) data matrix, where ( T ) is the number of time points.

II. Define Variable Set and Estimate Probabilities

- Ensemble Selection: Define the ensemble of brain regions for analysis. For computational feasibility, this is often done for all possible combinations of a fixed size (e.g., all triads or a large random subset of tetrads of regions) [22].

- State-Space Quantization: Discretize the continuous BOLD time series for each region into a finite set of symbolic states. This is a critical step for estimating information-theoretic quantities on continuous data. Common methods include:

- Binning: Dividing the signal amplitude range into a finite number of bins.

- Symbolic Encoding: Transforming the time series into symbols based on ordinal patterns.

III. Computation of Information-Theoretic Quantifiers

- Probability Estimation: For each selected ensemble of regions ( \mathbf{X} = {X1, X2, ..., X_k} ), estimate the joint probability distribution ( P(\mathbf{X}) ) and all relevant marginal distributions from the discretized data.

- Entropy Calculation: Compute the Shannon entropies ( H(X_i) ) and the joint entropy ( H(\mathbf{X}) ) from the estimated probability distributions.

- Quantifier Computation:

- Total Correlation: Calculate ( TC(\mathbf{X}) = \sum{i=1}^{k} H(Xi) - H(\mathbf{X}) ).

- O-Information: Calculate ( \Omega(\mathbf{X}) = TC(\mathbf{X}) - \sum{i=1}^{k} TC(\mathbf{X}{-i}) ).

- Partial Entropy Decomposition: Use a PED solver (e.g., based on the ( I{\min} ) redundancy function [22]) to compute the partial entropy atoms ( \mathcal{H}{\partial} ) for all possible combinations of sources within the ensemble.

IV. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

- Group-Level Analysis: Map the computed quantifiers (e.g., O-Information values, synergy/redundancy dominance) back to brain anatomy. Perform group-level statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) to identify networks or regions with significant effects.

- Temporal Dynamics: For a time-resolved analysis, apply the above computation within a sliding window to track how higher-order interactions evolve over the course of a recording [22].

- Correlation with Behavior: Regress higher-order metrics (e.g., the strength of synergy in a network) against behavioral measures to establish brain-behavior relationships [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Higher-Order Information-Theoretic Analysis

| Category / Item | Specification / Example | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Data & Atleses | ||

| fMRI Dataset | Human Connectome Project (HCP); 100 unrelated subjects [1] | Provides standardized, high-quality resting-state and task fMRI data for discovery and validation. |

| Brain Atlas | Cortical (100) + Subcortical (19) parcellation [1]; AAL; Yeo-17 | Defines the nodes (N) of the network for time series extraction and analysis. |

| Software & Libraries | ||

| Programming Language | Python (e.g., NumPy, SciPy) or MATLAB | Core computational environment for data handling and numerical computation. |

| Information Theory Toolkit | dit (Discrete Information Theory in Python), IDTxl |

Provides implemented functions for entropy, TC, and PID/PED calculations. |

| Neuroimaging Data Tools | FSL, AFNI, SPM, nilearn | Used for standard fMRI preprocessing, parcellation, and statistical mapping. |

| Topological Data Analysis | Applications of persistent homology to weighted simplicial complexes [1] | For alternative higher-order approaches based on co-fluctuation topology. |

| Computational Hardware | ||

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Cluster or workstation with high RAM and multi-core CPUs | Essential for the computationally intensive analysis of millions of region triads/tetrads [22]. |

Machine Learning and Hypergraph Neural Networks for Circuit Discovery and Interpretation

The study of the human connectome has traditionally relied on network models that represent brain activity through pairwise interactions between regions [1] [23]. While this approach has yielded significant insights, it fundamentally fails to capture the higher-order interactions (HOIs) that simultaneously involve three or more brain regions, which are increasingly recognized as crucial for understanding complex brain functions [1]. The emergence of hypergraph neural networks (HNNs) provides a powerful mathematical framework to model these complex group dynamics, offering unprecedented capabilities for circuit discovery and interpretation in neuroscience research [26] [27].

This paradigm shift is particularly relevant for higher-order connectomics, which aims to move beyond pairwise connectivity to map the brain's complex polyadic relationships [1] [28]. Recent research demonstrates that higher-order approaches significantly enhance our ability to decode tasks dynamically, improve individual identification of functional subsystems, and strengthen associations between brain activity and behavior [1] [23]. This application note details the methodologies and protocols for applying HNNs to circuit discovery, framed within the context of advancing human brain function research.

Theoretical Foundations: From Pairwise to Higher-Order Interactions

The Limitation of Pairwise Connectivity Models

Traditional functional connectivity (FC) models in fMRI analysis define weighted edges as statistical dependencies between time series recordings of brain regions [1]. These models assume the brain can be described solely by pairwise relationships, potentially missing significant information present only in joint probability distributions across multiple regions [1]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when studying complex cognitive functions that likely emerge from coordinated activity across distributed brain networks.

Hypergraphs for Higher-Order Interactions

Hypergraphs provide a mathematical foundation for modeling higher-order interactions [26] [29]. Unlike simple graphs where edges connect exactly two nodes, hypergraphs contain hyperedges that can connect any number of nodes [29]. A hypergraph is formally represented by an incidence matrix H of dimensions (N \times M), where (N) represents nodes and (M) represents hyperedges [29]. An entry (H_{ij}) is 1 if hyperedge (j) includes node (i), and 0 otherwise [29].

The node degrees and hyperedge degrees in a hypergraph are calculated as:

- Node degree: (d_V = H\sum(1)) (number of hyperedges including each node)

- Hyperedge degree: (d_E = H\sum(0)) (number of nodes included by each hyperedge) [29]

Neurobiological Evidence for Higher-Order Interactions

Mounting evidence at both micro- and macro-scales suggests that higher-order interactions are fundamental to the brain's spatiotemporal dynamics [1]. At the neuronal level, technologies have enabled recording of simultaneous firing in groups of neurons in animal models [1]. In humans, statistical methods must infer HOIs from neuroimaging signals, with recent topological approaches revealing their presence in fMRI data and their significant contribution to explaining complex brain dynamics [1].

Hypergraph Neural Networks: Architectural Principles