Beyond the Clinic: How VR is Outperforming Traditional Neuropsychological Tests in Sensitivity and Ecological Validity

This article systematically compares the sensitivity and validity of Virtual Reality (VR)-based neuropsychological assessments against traditional tools like the MoCA and ACE-III.

Beyond the Clinic: How VR is Outperforming Traditional Neuropsychological Tests in Sensitivity and Ecological Validity

Abstract

This article systematically compares the sensitivity and validity of Virtual Reality (VR)-based neuropsychological assessments against traditional tools like the MoCA and ACE-III. For researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational theory of ecological validity, present current methodological applications across conditions from mTBI to Alzheimer's, analyze troubleshooting for technical and adoption barriers, and synthesize validation studies demonstrating VR's superior predictive power for real-world functioning. Evidence indicates VR assessments offer enhanced sensitivity for early cognitive impairment detection, better prediction of functional outcomes like return to work, and more granular, objective data capture, positioning them as transformative tools for clinical trials and diagnostic precision.

The Ecological Validity Gap: Why Traditional Neuropsychological Tests Fail to Predict Real-World Functioning

Defining Veridicality vs. Verisimilitude in Cognitive Assessment

In neuropsychological assessment, ecological validity refers to the degree to which test performance predicts behaviors in real-world settings or mimics real-life cognitive demands [1]. The pursuit of ecological validity has become increasingly important as clinicians and researchers seek to translate controlled testing environments into meaningful predictions about daily functioning. This quest has given rise to two distinct methodological approaches: veridicality and verisimilitude. Within the rapidly evolving field of cognitive assessment, particularly with the emergence of virtual reality (VR) technologies, understanding the distinction between these approaches is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals evaluating cognitive outcomes. While veridicality concerns the statistical relationship between test scores and real-world functioning, verisimilitude focuses on the surface resemblance between test tasks and everyday activities [2] [3] [1]. This article examines how these approaches manifest across traditional and VR-based assessment paradigms, comparing their methodological foundations, experimental support, and implications for cognitive sensitivity research.

Conceptual Frameworks: Distinguishing the Two Approaches

Veridicality: The Statistical Correlation Approach

Veridicality represents a quantitative approach to ecological validity that emphasizes statistical relationships between test performance and measurable real-world outcomes [1] [4]. This methodology prioritizes predictive power through established correlation metrics between standardized test scores and criteria of everyday functioning. The veridicality approach underpins many traditional neuropsychological assessments, where the primary goal is to establish statistical associations that can forecast functioning in specific domains.

The theoretical foundation of veridicality assumes that cognitive processes measured in controlled environments have consistent, predictable relationships with real-world performance. For instance, a test exhibiting high veridicality would demonstrate strong correlation coefficients between its scores and independent measures of daily functioning, such as instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scales or occupational performance metrics [5]. This approach enables researchers to make evidence-based predictions about functional capacity based on test performance, which is particularly valuable in clinical contexts where decisions about diagnosis, treatment planning, or competency determinations are required.

Verisimilitude: The Appearance of Reality Approach

In contrast, verisimilitude emphasizes phenomenological resemblance between testing environments and real-world contexts [1] [4]. Rather than focusing primarily on statistical prediction, this approach aims to create tasks that closely mimic everyday cognitive challenges in their surface features, contextual demands, and required processing strategies. The term literally means "the appearance of being true or real," and in cognitive assessment, it translates to designing tests that engage perceptual, cognitive, and motor systems in ways that closely approximate real-world scenarios.

The theoretical premise of verisimilitude is that environmental context significantly influences cognitive processing, and therefore, assessments that incorporate realistic contextual cues will provide better insights into everyday functioning. This approach often involves simulating real-world environments where participants perform tasks that resemble daily activities, such as preparing a meal, navigating a neighborhood, or shopping in a virtual store [6] [4]. By embedding cognitive demands within familiar scenarios, verisimilitude-based assessments aim to capture cognitive functioning in contexts that more closely mirror the challenges individuals face in their daily lives.

Conceptual Relationship and Distinctions

The relationship between veridicality and verisimilitude represents a fundamental distinction in assessment philosophy. Importantly, these approaches can dissociate—a test high in verisimilitude does not necessarily demonstrate strong veridicality, and vice versa [3]. For example, one study examining social perception in schizophrenia found that a task using real-life social stimuli (high verisimilitude) effectively discriminated between patients and controls but failed to correlate with community functioning (poor veridicality) [3].

This dissociation highlights that surface realism does not guarantee predictive utility, and conversely, that statistically predictive tests may lack face validity. Understanding this distinction is crucial when selecting assessment tools for specific research or clinical purposes, particularly in pharmaceutical trials where cognitive outcomes may serve as primary or secondary endpoints.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Veridicality and Verisimilitude

| Dimension | Veridicality | Verisimilitude |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Statistical prediction of real-world functioning | Surface resemblance to real-world tasks |

| Methodology | Correlation with outcome measures | Simulation of everyday environments |

| Strength | Established predictive validity | Enhanced face validity and participant engagement |

| Limitation | May overlook contextual factors | resemblance doesn't ensure predictive power |

| Common Assessment Types | Traditional neuropsychological batteries | Virtual reality and simulated environments |

Traditional Neuropsychological Assessment: A Veridicality-Based Paradigm

Predominant Approach and Methodologies

Traditional neuropsychological assessments predominantly embrace the veridicality approach to ecological validity [4]. Established instruments like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and Clock Drawing Test (CDT) rely on correlating test scores with measures of daily functioning, caregiver reports, or clinical outcomes [7] [8]. These assessments are typically administered in controlled clinical environments using standardized paper-and-pencil or verbal formats designed to minimize distractions and maximize performance [1].

The experimental protocol for establishing veridicality typically involves cross-sectional correlations or longitudinal predictive studies that examine relationships between test scores and independent functional measures. For example, researchers might administer the MoCA to a cohort of patients with mild cognitive impairment and then examine the correlation between MoCA scores and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) ratings provided by caregivers [4]. Alternatively, longitudinal studies might investigate how well baseline test scores predict future functional decline or conversion to dementia.

Experimental Evidence and Limitations

Research indicates that traditional neuropsychological tests demonstrate moderate ecological validity when predicting everyday cognitive functioning, with the strongest relationships observed when the outcome measure corresponds specifically to the cognitive domain assessed by the tests [5]. For instance, executive function tests tend to correlate better with complex daily living tasks than with basic self-care activities. However, the veridicality of these traditional measures is moderated by several factors, including population characteristics, illness severity, time since injury, and the specific outcome measures employed [5].

A significant limitation of the veridicality approach emerges from its methodological constraints. The veridicality paradigm is constrained by potential inaccuracies in the outcome measures selected for comparison, limited perspectives on a person's daily behavior, and oversight of compensatory mechanisms that might facilitate real-world functioning despite cognitive impairment [4]. Furthermore, this approach often fails to capture the complex, integrated nature of cognitive functioning in daily life, where multiple processes interact within specific environmental contexts.

Virtual Reality Assessment: Advancing Verisimilitude

Technological Foundations and Methodologies

Virtual reality technologies have enabled significant advances in verisimilitude-based assessment by creating immersive, interactive environments that closely simulate real-world contexts [7] [4]. VR systems can faithfully reproduce naturalistic environments through head-mounted displays (HMDs), hand tracking technology, and three-dimensional virtual environments that mimic both basic and instrumental activities of daily living [6] [4]. Unlike traditional assessments that abstract cognitive processes into discrete tasks, VR-based assessments embed cognitive demands within familiar scenarios that maintain the complexity and contextual cues of everyday life.

The experimental protocol for VR assessment typically involves immersive scenario-based testing where participants interact with virtual environments through natural movements and decisions. For example, the CAVIRE-2 system comprises 14 discrete scenes, including a starting tutorial and 13 virtual scenes simulating daily living activities in familiar residential and community settings [4]. Tasks might include making a sandwich, using the bathroom, tidying up a playroom, choosing a book, navigating a neighborhood, or shopping in a virtual store [6] [4]. These environments are designed with a high degree of realism to bridge the gap between unfamiliar testing environments and participants' real-world experiences.

Experimental Evidence and Advantages

Studies demonstrate that VR-based assessments offer enhanced ecological validity, engagement, and diagnostic sensitivity compared to traditional methods [7]. A feasibility study on VR-based cognitive training for Alzheimer's patients using the MentiTree software reported a 93% feasibility rate with minimal adverse effects, suggesting good tolerability even in cognitively impaired populations [6]. The CAVIRE-2 system has shown moderate concurrent validity with established tools like the MoCA while demonstrating good test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.89) and strong discriminative ability (AUC = 0.88) between cognitively normal and impaired individuals [4].

The advantages of VR-based verisimilitude approaches include automated data collection of performance metrics beyond simple accuracy scores, including response times, error patterns, navigation efficiency, and behavioral sequences [7] [4]. This provides richer, more objective data on cognitive functioning in contexts that closely approximate real-world demands. Additionally, the engaging nature of VR assessments may reduce testing anxiety and improve motivation, potentially yielding more valid representations of cognitive abilities [7] [4].

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Direct Comparison of Assessment Approaches

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between Traditional and VR Assessment Methods

| Metric | Traditional (Veridicality) | VR-Based (Verisimilitude) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Validity | Moderate [5] | Enhanced [7] | Multiple study comparisons |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | MoCA: 86%/88% for MCI [8] | CAVIRE-2: 88.9%/70.5% [4] | Discrimination of cognitive status |

| Test-Retest Reliability | Varies by instrument | ICC = 0.89 for CAVIRE-2 [4] | Repeated assessment studies |

| Participant Engagement | Often limited [7] | High immersion and motivation [9] | User experience reports |

| Cultural/Linguistic Bias | Significant concerns [10] [8] | Potentially reduced through customization | Multi-ethnic population studies |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Traditional Assessment Protocol (Veridicality-Focused)

The standard administration of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) exemplifies the veridicality approach [8]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Environment: Controlled, quiet room with minimal distractions

- Administration: Trained examiner provides standardized instructions

- Tasks: Assessment across eight cognitive domains (visuospatial abilities, naming, memory, attention, language, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation) using paper-based materials

- Scoring: Predetermined criteria with maximum score of 30 points

- Validation: Statistical correlation with clinical diagnoses and functional outcomes

The MoCA demonstrates discriminative ability through significant performance differences across clinical groups (young adults > older adults > people with Parkinson's Disease) [8]. However, limitations include susceptibility to educational and cultural biases, with Arabic-speaking cohorts demonstrating significantly lower scores despite similar clinical status [8].

VR Assessment Protocol (Verisimilitude-Focused)

The CAVIRE-2 assessment system exemplifies the verisimilitude approach [4]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Equipment: Head-mounted display (Oculus Rift S) with hand tracking technology

- Environment: 13 immersive virtual scenes simulating daily activities in residential and community settings

- Tasks: Performance of both basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL and IADL) with automatic difficulty adjustment

- Duration: Approximately 10 minutes for complete assessment

- Metrics: Automated scoring based on performance matrix of scores and completion time across six cognitive domains

This protocol has demonstrated strong discriminative ability (AUC = 0.88) in distinguishing cognitively healthy older adults from those with mild cognitive impairment in primary care settings [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Methodological Components for Ecological Validity Research

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Creates immersive virtual environments | Oculus Rift S (2560 × 1440 resolution, 115-degree FOV) [6] |

| Hand Tracking Technology | Enables natural interaction with virtual objects | Sensor-based movement recognition projecting real-hand movements to virtual hands [6] |

| Virtual Scenario Libraries | Provides verisimilitude-based task environments | CAVIRE-2's 13 scenes including meal preparation, navigation, shopping [4] |

| Automated Scoring Algorithms | Standardizes assessment and reduces administrator variability | Performance matrices combining accuracy, time, and efficiency metrics [4] |

| Cultural Adaptation Frameworks | Addresses demographic diversity in assessment | Community-specific modifications in test development, administration, and scoring [8] |

| Real-World Outcome Measures | Establishes veridicality through correlation | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scales, caregiver reports, community functioning measures [5] [3] |

The comparison between veridicality and verisimilitude approaches in cognitive assessment reveals complementary strengths rather than mutually exclusive methodologies. Traditional veridicality-based assessments provide established statistical relationships with functional outcomes, while verisimilitude-based VR approaches offer enhanced ecological validity through realistic task environments. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal approach may involve integrating both methodologies to leverage their respective advantages.

Future directions should focus on developing hybrid assessment models that incorporate verisimilitude's realistic task environments with veridicality's robust predictive validation. Additionally, addressing technical challenges, establishing standardized protocols, and ensuring accessibility across diverse populations will be crucial for advancing both approaches [7]. As cognitive assessment continues to evolve, the thoughtful integration of veridicality and verisimilitude principles will enhance the sensitivity and clinical relevance of cognitive outcomes in research and therapeutic development.

Limitations of Pen-and-Paper Tests (MoCA, ACE-III, MMSE) in Isolated Settings

In the clinical and research assessment of cognitive impairment, traditional pen-and-paper tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE-III), and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) have long been the standard tools. Their widespread use is attributed to their brevity, ease of administration, and established presence in protocols. However, when used in isolated settings—deployed as stand-alone instruments without the context of a full clinical workup—significant limitations emerge that can compromise diagnostic accuracy and ecological validity. These tests, while useful for gross screening, are increasingly found to lack the sensitivity, specificity, and real-world applicability required for early detection and nuanced monitoring of cognitive decline, particularly in the context of progressive neurodegenerative diseases [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these traditional tools against emerging alternatives, such as computerized and Virtual Reality (VR)-based assessments, by synthesizing data from recent experimental studies. The analysis is framed within broader research on enhancing the sensitivity of neuropsychological evaluation.

Comparative Performance Data of Traditional Tests

The following tables summarize key experimental data on the performance and limitations of the MoCA, ACE-III, and MMSE, as identified in recent literature.

Table 1: Diagnostic Accuracy and Key Limitations of Traditional Tests

| Test | Primary Reported Strengths | Documented Limitations in Isolated Use | Reported Sensitivity/Specificity Variability |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoCA | Superior to MMSE in detecting Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI); assesses multiple domains including executive function [12] [13]. | Scores are significantly influenced by age and education (these factors account for up to 49% of score variance [14]); cut-off scores are not universally generalizable across cultures [14]. | Sensitivity for MCI: Variable, 75%-97% (at different thresholds); Specificity: Can be low (4%-77%), leading to high false positives, depending on population and threshold [15]. |

| ACE-III | Provides a holistic profile across five cognitive subdomains; sensitive to a wider spectrum of severity than MMSE [16]. | Lacks ecological validity; tasks do not correspond well to real-world functional demands [11]. Optimal thresholds for dementia/MCI are not firmly established, leading to application variability [15]. | Specificity is highly variable (32% to 100%), indicating a risk of both false positives and negatives when used as a stand-alone screen [15]. |

| MMSE | Well-known, widely used for global cognitive screening [17]. | Insensitive to MCI and early dementia; significant ceiling effects; poor predictor of conversion from MCI to dementia [17] [13]. | For predicting conversion from MCI to all-cause dementia: Sensitivity 23%-76%, Specificity 40%-94% [17]. |

Table 2: Comparative Data from Emerging Assessment Modalities

| Study Focus | Experimental Protocol | Key Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|

| AI-Enhanced Computerized Test (ICA) [18] | 230 participants (95 healthy, 80 MCI, 55 mild AD) completed the 5-minute ICA, MoCA, and ACE. An AI model analyzed ICA performance. | The ICA's correlation with years of education (r=0.17) was significantly lower than MoCA (r=0.34) and ACE (r=0.41). The AI model detected MCI with an AUC of 81% and mild AD with an AUC of 88%. |

| VR-Based Assessment [11] | 82 young participants (18-28 years) completed both traditional ACE-III and goal-oriented VR/3D mobile games. Correlative and regression analyses were performed. | Game-based scores showed a positive correlation with ACE-III. Game performances provided more granular, time-based data and revealed real-world traits (e.g., hand-use confusion) not captured by ACE-III. |

| VR for Executive Function [19] | Meta-analysis of 9 studies investigating the correlation between VR-based assessments and traditional neuropsychological tests for executive function. | A statistically significant correlation was found between VR-based assessments and traditional measures across subcomponents of executive function (cognitive flexibility, attention, inhibition), supporting VR's validity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Validation of a Computerized AI-Based Assessment

A 2021 study directly compared the Integrated Cognitive Assessment (ICA) against MoCA and ACE-III [18].

- Participants: 230 individuals, including 95 healthy controls, 80 with MCI, and 55 with mild Alzheimer's disease.

- Methodology: All participants completed the ICA, MoCA, and ACE. The ICA is a 5-minute, language-independent, computerized test involving a rapid visual categorization task (distinguishing animal from non-animal images) with backward masking to reduce recurrent neural processing. An artificial intelligence (AI) model was trained on the test performance data to classify cognitive status.

- Outcome Measures: The study assessed convergent validity (correlation with MoCA/ACE), diagnostic accuracy (Area Under the Curve - AUC), and bias (correlation with years of education).

- Key Finding: The AI model demonstrated generalizable performance in detecting cognitive impairment, with the ICA showing significantly less education bias than the traditional paper-and-pencil tests [18].

Protocol: Validation of VR/3D Game-Based Assessment against ACE-III

A 2024 study piloted a novel approach using VR and mobile games for cognitive assessment in a young cohort [11].

- Participants: 82 young participants aged 18-28 years.

- Methodology: Participants underwent a traditional ACE-III assessment and also played three goal-oriented games (two in VR, one on a 3D mobile platform). The games were designed to simulate real-world cognitive challenges.

- Analysis: Researchers employed three main analysis methods:

- Correlative Analysis: To measure the relationship between game-based scores and ACE-III scores.

- Z-score Analysis: To compare the distribution of game scores and ACE-III scores.

- Regression Analysis: To explore the association between both scoring methods and cognitive health factors (e.g., age, smoking).

- Key Finding: The study established the plausibility of using goal-oriented games for more granular, time-based, and functional cognitive assessment that can inform about real-world behaviors, a dimension lacking in ACE-III [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Cognitive Assessment Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | A 30-point, one-page pen-and-paper test administered in ~10 minutes to screen for mild cognitive impairment. It assesses multiple domains: attention, executive functions, memory, language, abstraction, and orientation [18] [13]. |

| Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination-III (ACE-III) | A more detailed 100-point paper-based cognitive screen assessing five domains: attention and orientation, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities. Typically takes about 20 minutes to administer [18] [16]. |

| Integrated Cognitive Assessment (ICA) | A 5-minute, computerized cognitive test using a rapid visual categorization task. It employs an AI model to improve accuracy in detecting cognitive impairment and is designed to be unbiased by language, culture, and education [18]. |

| Virtual Reality (VR) Headsets (e.g., Meta Quest) | Standalone VR hardware used to create immersive, ecologically valid testing environments. It allows for natural movement recognition and the simulation of real-world activities for cognitive assessment [20] [11]. |

| VR Cognitive Games (e.g., Enhance VR) | A library of gamified cognitive exercises in VR that assess domains like memory, attention, and cognitive flexibility. These games adapt difficulty based on user performance and provide time-factored, objective metrics [20]. |

| CANTAB (Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery) | A computer-based cognitive assessment system consisting of a battery of tests. It is widely used in research and clinical trials to precisely measure core cognitive functions while minimizing human administrator bias [19]. |

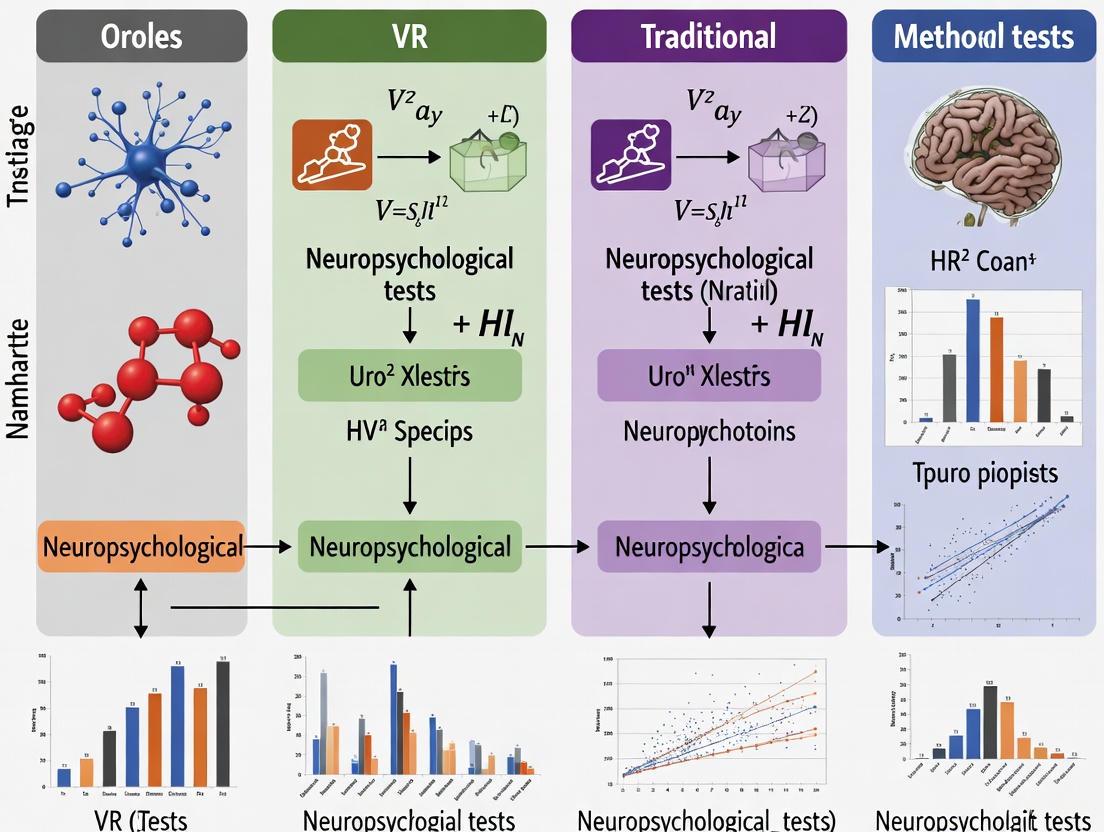

Visualizing the Research Paradigm Shift

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and key differentiators between the traditional pen-and-paper assessment paradigm and the emerging technology-enhanced approach.

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychological assessment, primarily due to its capacity to mimic real-life cognitive demands with high ecological validity. Traditional neuropsychological tests, while standardized and reliable, often lack realism and fail to capture how cognitive impairments manifest in daily living situations [7] [21]. In contrast, VR creates immersive, interactive environments that simulate the complexity of real-world scenarios, engaging multiple cognitive domains simultaneously within a controlled setting [7]. This article examines the theoretical foundations supporting VR's effectiveness, compares its sensitivity to traditional methods, and presents experimental data validating its use in research and clinical practice.

Theoretical Foundations: Ecological Validity and Cognitive Engagement

The superior ecological validity of VR-based assessments represents their core theoretical advantage. Ecological validity refers to the degree to which test conditions replicate real-world settings and the extent to which findings can be generalized to everyday life [21]. Traditional paper-and-pencil tests are typically administered in quiet, distraction-free environments, which contrasts sharply with the multisensory, dynamic nature of real-world cognitive challenges [21]. VR bridges this gap by creating immersive simulations that preserve experimental control while mimicking environmental complexity.

Key theoretical mechanisms through which VR enhances cognitive assessment include:

- Multi-sensory Integration: VR engages visual, auditory, and sometimes haptic sensory channels simultaneously, creating a more realistic cognitive load that mirrors daily challenges [7].

- Dynamic Environment Interaction: Unlike static traditional tests, VR environments are interactive and evolve based on user decisions, requiring continuous updating of mental representations and strategic planning [7].

- Contextualized Cognitive Demands: VR embeds cognitive tasks within meaningful scenarios (e.g., virtual cooking, navigation, shopping), making assessments more representative of real-world functioning [21].

- Enhanced Patient Engagement: The immersive nature of VR increases motivation and engagement, potentially leading to more accurate performance measures by reducing test fatigue and increasing compliance [7] [22].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway from traditional assessment limitations to VR solutions and their resulting benefits in neurocognitive evaluation:

Comparative Sensitivity: VR Versus Traditional Neuropsychological Measures

A growing body of research demonstrates that VR-based assessments often show superior sensitivity compared to traditional neuropsychological tests in detecting subtle cognitive impairments, particularly in executive functions, spatial memory, and complex attention.

Sensitivity in Detecting Residual Cognitive Deficits

VR environments have proven particularly effective in identifying lingering cognitive abnormalities in populations where traditional tests may indicate full recovery. A study on sport-related concussions found that VR-based assessment detected residual cognitive impairments in clinically asymptomatic athletes who had normal results on conventional tests [23].

Table 1: Sensitivity and Specificity of VR-Based Assessment for Detecting Residual Cognitive Abnormalities Following Concussion

| Cognitive Domain | VR Assessment Module | Sensitivity | Specificity | Effect Size (Cohen's d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Navigation | Virtual navigation tasks | 95.8% | 91.4% | 1.89 |

| Whole Body Reaction | Motor response in VR | 95.2% | 89.1% | 1.50 |

| Combined VR Modules | Multiple domains | 95.8% | 96.1% | 3.59 |

The significantly high sensitivity and specificity values, particularly the remarkable effect size for combined VR modules (d=3.59), demonstrate VR's enhanced capability to detect subtle cognitive abnormalities that traditional assessments might miss [23].

Predictive Power for Age-Related Cognitive Decline

Comparative studies have examined the relative predictive power of VR tasks versus traditional measures for identifying age-related cognitive changes. One study directly compared immersive VR tasks with traditional executive function measures like the Stroop test and Trail Making Test (TMT) [24].

Table 2: Comparison of Predictive Power for Age-Related Cognitive Decline: VR vs. Traditional Measures

| Assessment Method | Specific Task/Measure | Contribution to Explained Variance in Age | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Tasks | Parking simulator levels completed | Significant primary contributor | p < 0.001 |

| Objects placed in seating arrangement | Significant primary contributor | p < 0.001 | |

| Items located in chemistry lab | Significant contributor | p < 0.01 | |

| Traditional Measures | Stroop Color-Word Test | Lesser contributor | Not specified |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | Lesser contributor | Not specified |

The VR measures were found to be stronger contributors than existing traditional neuropsychological tasks in predicting age-related cognitive decline, highlighting their enhanced sensitivity to cognitive changes associated with aging [24].

Experimental Evidence and Methodological Protocols

VR Cognitive Training in Older Adults

A cluster randomized controlled trial examined the effects of immersive leisure-based VR cognitive training in community-dwelling older adults, employing rigorous methodology to compare VR interventions with active control conditions [25].

Table 3: Experimental Protocol: VR Cognitive Training for Community-Dwelling Older Adults

| Methodological Component | VR Group Protocol | Control Group Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Cluster randomized controlled trial |

| Participants | 137 community-dwelling older adults (≥60 years), MMSE ≥21 | Same participant characteristics |

| Intervention | Fully immersive VR gardening activities (planting, fertilizing, harvesting) using HTC VIVE PRO | Well-arranged leisure activities without cognitive focus |

| Session Duration & Frequency | 60 minutes daily, 2 days per week, for 8 weeks | Identical duration and frequency |

| Cognitive Challenges | Seven difficulty levels targeting attention, processing speed, memory, spatial relations, executive function | No focused cognitive challenges |

| Primary Outcomes | MoCA, WMS-Digit Span Sequencing (DSS), Timed Up and Go (TUG) | Identical measures |

| Key Findings | Significant improvements in MoCA (p<0.001), WMS-DSS (p=0.015), and TUG (p=0.008) compared to control | Lesser improvements on outcome measures |

The experimental protocol ensured comparable intervention intensity between groups while isolating the effect of the VR cognitive training component. The significant improvements in global cognition, working memory, and physical function demonstrate VR's effectiveness when compared to an active control group, addressing methodological limitations of earlier studies that used passive control groups [25].

Meta-Analytic Evidence for Mild Cognitive Impairment

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 30 randomized controlled trials evaluated the effects of VR-based interventions on cognitive function in adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), providing robust evidence across multiple studies [26].

Table 4: Effects of VR-Based Interventions on Cognitive Function in MCI: Meta-Analysis Results

| Cognitive Domain | Assessment Tool | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | Statistical Significance | Certainty of Evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Cognition | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | 0.82 | p = 0.003 | Moderate |

| Global Cognition | Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | 0.83 | p = 0.0001 | Low |

| Attention | Digit Span Backward (DSB) | 0.61 | p = 0.003 | Low |

| Attention | Digit Span Forward (DSF) | 0.89 | p = 0.002 | Low |

| Quality of Life | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) | 0.22 | p = 0.049 | Moderate |

The meta-analysis revealed that optimal cognitive outcomes were associated with specific VR parameters: semi-immersive systems, session durations of ≤60 minutes, intervention frequencies exceeding twice per week, and participant groups with lower male proportion (≤40%) [26]. These findings provide guidance for researchers designing VR-based cognitive interventions.

The following workflow diagram illustrates a typical experimental protocol for VR-based cognitive assessment, highlighting the integration of traditional and VR methodologies:

Implementing VR-based cognitive assessment requires specific hardware, software, and methodological resources. The following table details key components of a VR research toolkit and their functions in cognitive assessment protocols.

Table 5: Essential Research Toolkit for VR-Based Cognitive Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function in Research | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMD) | Provides fully immersive VR experience | HTC VIVE PRO [25]; Oculus Rift | Consumer-grade vs. clinical-grade systems; resolution and field of view |

| VR Authoring Software | Enables creation of custom virtual environments | Unity 3D; Unreal Engine | Programming expertise required; asset libraries available |

| 360-Degree Video Capture | Records real-world environments for VR | Medical training simulations [27] | Special 360-degree camera equipment needed |

| Integrated VR Treadmills | Allows natural locomotion in VR | Motekforce Link treadmill [28] | Enables walking-based cognitive assessment |

| Physiological Monitoring | Records concurrent physiological data | EEG systems [29]; heart rate monitors | Synchronization with VR events crucial |

| Traditional Assessment Tools | Provides baseline and validation measures | MoCA [25] [26]; Digit Span [25] [26]; Trail Making Test [24] | Essential for establishing convergent validity |

| Data Analysis Platforms | Processes behavioral metrics from VR | Custom MATLAB/Python scripts; commercial analytics | Automated performance scoring advantageous |

VR technology represents a paradigm shift in neurocognitive assessment by successfully mimicking real-life cognitive demands through immersive, ecologically valid environments. The experimental evidence demonstrates that VR-based assessments frequently show superior sensitivity compared to traditional measures, particularly for detecting subtle cognitive impairments, predicting age-related decline, and evaluating complex cognitive domains like executive function and spatial memory. The theoretical strength of VR lies in its ability to engage multiple cognitive processes simultaneously within realistic contexts while maintaining experimental control. As research methodologies continue to refine VR protocols and address current limitations regarding standardization and accessibility, VR is poised to become an increasingly essential tool in cognitive neuroscience research and clinical neuropsychological practice.

A core challenge in neuropsychology and drug development is the ecological validity gap: the limited ability of traditional cognitive assessments to predict a patient's real-world functioning. Conventional pen-and-paper neuropsychological tests, while standardized and reliable, are administered in controlled clinical settings that poorly simulate the cognitive demands of daily life [21]. This creates a significant disconnect between clinical scores and actual functional capacity, complicating therapeutic development and clinical decision-making.

Virtual Reality (VR) emerges as a transformative solution by enabling verisimilitude—designing assessments where cognitive demands mirror those in naturalistic environments [4]. By immersing patients in simulated real-world scenarios, VR-based tools can capture a more dynamic and functionally relevant picture of cognitive health, thereby creating a more powerful predictive link between assessment results and real-world outcomes.

Comparative Analysis: VR vs. Traditional Neuropsychological Tests

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies directly comparing VR-based cognitive assessments with traditional tools.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of VR and Traditional Cognitive Assessments

| Study & Assessment Tool | Study Population | Key Correlation with Traditional Tests | Association with Real-World Function (ADL) | Discriminatory Power (e.g., AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAVIR [30] | 70 patients with mood/psychosis disorders & 70 HC | Moderate correlation with global neuropsychological test scores (rₛ = 0.60, p<0.001) | Weak-moderate association with ADL process skills (r = 0.40, p<0.01); superior to traditional tests | Sensitive to impairment; differentiated employment status |

| CAVIRE-2 [4] | 280 multi-ethnic older adults | Moderate concurrent validity with MoCA | Based on verisimilitude paradigm (simulated ADLs) | AUC=0.88 for distinguishing cognitive status |

| VEGS [31] | 156 young adults, healthy older adults, & clinical older adults | Highly correlated with CVLT-II on all variables | Assesses memory in realistic, distracting environments | N/A |

| SLOF (Rating Scale) [32] | 198 adults with schizophrenia | N/A (itself a functional rating scale) | Superior predictor of performance-based ability measures | N/A |

HC: Healthy Controls; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; AUC: Area Under the Curve; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; CVLT-II: California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition; SLOF: Specific Levels of Functioning Scale.

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality (CAVIR)

The CAVIR test was designed to assess daily-life cognitive skills within an immersive virtual reality kitchen scenario [30].

- Objective: To investigate the validity and sensitivity of CAVIR and its association with Activities of Daily Living (ADL) in patients with mood or psychosis spectrum disorders.

- Participants: 70 symptomatically stable patients and 70 healthy controls.

- Procedure:

- Participants completed the CAVIR assessment, which involves performing a series of goal-directed tasks in a virtual kitchen.

- They also underwent a battery of standard neuropsychological tests.

- Clinical symptoms, functional capacity, and subjective cognition were rated.

- Patients' real-world ADL ability was evaluated using the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS), an observational assessment of performance in everyday tasks.

- Outcome Measures: The primary analyses focused on correlations between global CAVIR performance, global neuropsychological test scores, and AMPS scores.

Protocol: Virtual Environment Grocery Store (VEGS) vs. CVLT-II

This study compared a VR-based memory test with a traditional list-learning test [31].

- Objective: To compare episodic memory performance on the VEGS and the CVLT-II across young adults, healthy older adults, and older adults with a neurocognitive diagnosis.

- Participants: 156 participants (53 young adults, 85 healthy older adults, 18 clinical older adults).

- Procedure:

- Participants were administered the CVLT-II, a standard verbal list-learning test.

- They also completed the VEGS, a VR-based task where they navigate a virtual grocery store and are asked to memorize items to purchase amidst everyday auditory and visual distractors.

- The Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System Color-Word Interference Test (D-KEFS CWIT) was administered to assess executive function.

- Outcome Measures: Correlations between VEGS and CVLT-II scores, comparison of recall scores between the two tests, and analysis of their relationship with executive function measures.

Protocol: Validation of CAVIRE-2 as a Cognitive Screening Tool

This study validated a fully immersive, automated VR system for comprehensive cognitive assessment [4].

- Objective: To validate the CAVIRE-2 software as a tool to distinguish between cognitively healthy and impaired older adults in a primary care setting.

- Participants: 280 multi-ethnic Asian adults aged 55-84 recruited from a primary care clinic.

- Procedure:

- Participants completed the CAVIRE-2 assessment, which consists of 13 scenarios simulating Basic and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (BADL and IADL) in local community settings.

- Performance was automatically scored based on a matrix of accuracy and completion time across the six cognitive domains.

- All participants were independently assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

- Outcome Measures: Concurrent validity (correlation with MoCA), test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and discriminative ability (AUC) to identify cognitive impairment.

Logical Workflow: From Assessment to Functional Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway through which VR-based assessments create a more robust predictive model for real-world functioning compared to traditional methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers seeking to implement or develop VR-based functional assessments, the following toolkit details essential components and their functions derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Functional Assessment

| Toolkit Component | Function & Rationale | Exemplar Tools from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Hardware | Provides a controlled yet ecologically valid sensory environment for assessment. | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) for full immersion [21] [4] |

| Software/VR Platform | Generates standardized, interactive scenarios simulating real-world cognitive demands. | CAVIR (kitchen scenario) [30]; VEGS (grocery store) [31]; CAVIRE-2 (community & residential settings) [4] |

| Performance Metrics Algorithm | Automates scoring to reduce administrator bias and enhance objectivity; captures multi-dimensional data. | CAVIRE-2's matrix of scores and completion time [4]; Error type and latency profiles [33] |

| Traditional Neuropsychological Battery | Serves as a criterion for establishing convergent validity of the novel VR tool. | MoCA [4]; CVLT-II [31]; MCCB, UPSA-B [32] |

| Real-World Function Criterion | Provides a benchmark for validating the ecological and predictive validity of the VR assessment. | Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) [30]; Specific Levels of Functioning (SLOF) scale [32] |

The evidence demonstrates a clear paradigm shift in cognitive assessment. VR-based tools like CAVIR, VEGS, and CAVIRE-2 consistently show moderate to strong correlations with traditional tests, proving they measure core cognitive constructs. More importantly, they establish a superior predictive link to real-world functioning by leveraging immersive, ecologically valid environments. For researchers and drug developers, this enhanced functional prediction is critical. It enables more sensitive detection of cognitive changes in clinical trials and provides more meaningful endpoints that truly reflect a treatment's potential impact on a patient's daily life.

VR in Action: Methodological Approaches and Applications in Cognitive Assessment

In the context of comparing Virtual Reality (VR) with traditional neuropsychological tests, a critical technical distinction lies in the level of immersion offered by different systems. The choice between immersive and non-immersive VR is not merely one of hardware preference but fundamentally influences the ecological validity, user engagement, and, consequently, the sensitivity of cognitive assessments [34] [4]. Immersive systems typically use Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) to fully surround the user in a digital environment, whereas non-immersive systems rely on standard monitors, providing a window into a virtual world [35]. This guide objectively compares these systems based on hardware, software, and experimental data, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for selecting appropriate technologies for sensitive neuropsychological research.

Hardware and System Architecture

The core difference between immersive and non-immersive VR systems stems from their fundamental hardware architecture, which directly dictates the user's level of sensory engagement and the system's application potential.

Table 1: Core Hardware Comparison

| Feature | Immersive VR (HMD-Based) | Non-Immersive VR (Desktop-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Display | Head-Mounted Display (HMD) with stereoscopic lenses [36] [35] | Standard monitor, television, or smartphone screen [35] |

| Tracking Systems | Advanced inside-out tracking with multiple cameras; head, hand, and controller tracking with 6 degrees of freedom (6DoF) [36] [37] | Limited to traditional input; no positional tracking of the user's head [35] |

| User Input | Advanced motion controllers, data gloves, and vision-based hand tracking [36] [35] | Traditional peripherals (mouse, keyboard, gamepad) [35] |

| Level of Immersion | High to very high; designed to shut out the physical world and create a strong sense of "presence" [34] [35] | Low; user remains fully aware of their physical surroundings [35] |

| Example Hardware | Meta Quest 3, Sony PlayStation VR2, Apple Vision Pro, HTC Vive Pro 2 [38] [39] [40] | Standard PC or laptop setup without a headset [35] |

The Immersion Spectrum and Associated Technologies

VR systems exist on a spectrum of immersion, largely defined by hardware. Fully Immersive VR represents the highest level, where HMDs completely occupy the user's visual and auditory fields to create a compelling sense of "presence" – the psychological feeling of being in the virtual environment [36] [35]. Key enabling technologies include high-resolution displays (often exceeding 4K per eye), high refresh rates (90Hz or higher) to prevent motion sickness, and pancake lenses that allow for slimmer headset designs [36] [37]. Non-Immersive VR, in contrast, provides a windowed experience on a standard screen, with interaction mediated by traditional peripherals [35]. A middle ground, Semi-Immersive VR, often uses large projection systems or multiple monitors to dominate the user's field of view without completely isolating them, commonly found in flight simulators [35].

Experimental Protocols and Empirical Findings

The structural differences between immersive and non-immersive VR systems lead to measurable variations in user experience and cognitive outcomes, which are critical for research design.

Key Comparative Experimental Protocols

Controlled studies often expose participants to the same virtual environment via different hardware systems to isolate the effect of immersion.

- Museum Environment Study: A 2025 controlled study involved 87 college students randomly assigned to either an HMD (immersive) or a non-immersive (desktop) version of the same virtual museum—a digital twin of the "L'altro Renaissance" exhibition. The objective was to measure the effects on spatial learning, aesthetic appreciation, and behavioral intention [34].

- Protocol: After the virtual exploration, participants completed questionnaires assessing their sense of immersion, the pleasantness of the experience, and their willingness to repeat a similar museum experience. This protocol directly links the hardware interface to psychological and behavioral outcomes [34].

- Cognitive Assessment Validation (CAVIRE-2): A separate study validated a fully immersive VR system (CAVIRE-2) as a tool for assessing six cognitive domains in older adults (aged 55-84) in a primary care setting. Participants completed both the VR assessment and the traditional Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [4].

- Protocol: The CAVIRE-2 software presented participants with 13 scenarios in virtual environments simulating basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL and IADL). Performance was automatically scored based on a matrix of accuracy and completion time, providing a multi-domain cognitive profile with high ecological validity [4].

Empirical data consistently shows that the level of immersion significantly impacts user experience and can influence cognitive measures.

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Data from Key Studies

| Study Focus | Immersive VR (HMD) Findings | Non-Immersive VR (Desktop) Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Museum Experience | Produced a greater sense of immersion, was rated as more pleasant, and led to a higher intention to repeat the experience [34]. | Was perceived as less immersive and less pleasant compared to the HMD condition [34]. |

| Spatial Navigation & Learning | Mixed results: Some studies show enhanced engagement but sometimes poorer spatial recall when physical movement is restricted, potentially due to a lack of idiothetic cues [34]. | Can sometimes lead to better spatial recall (e.g., map drawing) and causes less motion sickness and lower cognitive workload [34]. |

| Cognitive Assessment | Shows high sensitivity and ecological validity. CAVIRE-2 demonstrated an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.88 for discriminating cognitive status, with 88.9% sensitivity and 70.5% specificity [4]. | Not typically used for comprehensive, automated cognitive assessments in the same ecological manner as systems like CAVIRE-2 [4]. |

| Educational Learning | Enhances engagement and long-term retention by cultivating longer visual attention and fostering a higher sense of immersion [34]. | Provides a viable and often more accessible option, though with lower engagement and long-term retention potential [34]. |

A systematic review of Extended Reality (XR) for neurocognitive assessment further supports these findings, concluding that VR-based tools ( predominantly HMD) are more sensitive, ecologically valid, and engaging compared to traditional assessment tools [41] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing experiments comparing VR systems, the following "reagents" or core components are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for VR System Comparison

| Item | Function in Research | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | The primary hardware for delivering the fully immersive VR condition. Creates stereoscopic 3D visuals and tracks head movement [36] [35]. | Key specs include per-eye resolution, field of view (FOV), refresh rate, and tracking capabilities (e.g., inside-out). Comfort for extended sessions is critical [38] [37]. |

| VR Motion Controllers | Enable natural interaction within the immersive virtual environment. Provide input and often include haptic feedback [36] [39]. | Evaluate tracking accuracy, ergonomics, and battery life. Consider systems that also support vision-based hand tracking for more natural input [38] [37]. |

| High-Performance PC/Console | Required to run high-fidelity VR experiences, either by rendering content for PC-connected headsets or for developing complex virtual environments [39] [40]. | A powerful GPU and CPU are necessary. For standalone HMDs, the onboard processor is key (e.g., Snapdragon XR2 Gen 2) [38] [39]. |

| Standard Desktop Computer | The hardware platform for the non-immersive VR condition. Runs the virtual environment on a standard monitor [35]. | Should have sufficient graphics capability to run the 3D environment smoothly to ensure performance differences are not due to lag or low frame rates. |

| Identical Virtual Environment Software | The core experimental stimulus. To ensure a valid comparison, the virtual environment (VE) must be functionally identical across immersive and non-immersive conditions [34]. | The software platform must support deployment to both HMD and desktop formats without altering the core logic or visual fidelity of the tasks. |

| Validated Questionnaires | Measure psychological constructs affected by immersion, such as sense of presence, user engagement, simulator sickness, and usability [34]. | Use standardized scales (e.g., Igroup Presence Questionnaire, Simulator Sickness Questionnaire) to allow for comparison with existing literature. |

The decision between immersive and non-immersive VR systems is a fundamental one that directly impacts the ecological validity, user engagement, and sensitivity of neuropsychological research. Immersive HMD-based systems consistently demonstrate a superior capacity to elicit a sense of presence and show great promise as highly sensitive tools for ecological cognitive assessment, as evidenced by their growing use in clinical validation studies [4] [7]. Non-immersive systems, while less sensorially engaging, offer greater accessibility, reduced risk of simulator sickness, and can be perfectly adequate for certain cognitive tasks [34] [35]. The choice is not which system is universally better, but which is most appropriate for the specific research question, target population, and experimental constraints. As the technology continues to evolve, this hardware-level comparison will remain a cornerstone of rigorous experimental design in VR-based cognitive science and drug development.

Virtual reality (VR) is reshaping neuropsychological assessment by introducing dynamic, ecologically valid tools for evaluating core cognitive domains. This guide provides a comparative analysis of VR-based and traditional methods for assessing memory, attention, and executive functions, synthesizing current research data to inform researcher and practitioner selection.

Comparative Performance Data Across Cognitive Domains

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies directly comparing VR and traditional neuropsychological assessments.

| Cognitive Domain | Assessment Tool | Key Comparative Findings | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Memory | Digit Span Task (DST) | Similar performance between PC and VR versions [42]. | Study with 66 healthy adults [42]. |

| Visuospatial Working Memory | Corsi Block Task (CBT) | PC version enabled better performance (e.g., longer sequence recall) than VR version [42]. | Study with 66 healthy adults [42]. |

| Processing Speed / Psychomotor | Deary-Liewald Reaction Time Task (DLRTT) | Significantly faster reaction times (RT) on PC than in VR [42]. | Study with 66 healthy adults [42]. |

| Processing Speed | Beat Saber VR Training | Significant increase in processing speed (p=.035) and reduced errors (p<.001) post-VR training [43]. | RCT with 100 TBI patients [43]. |

| Global Cognition & Daily Function | Cognition Assessment in VR (CAVIR) | Moderate correlation with standard neuropsychological tests (r𝑠=0.60, p<.001). Moderate association with daily living (r=0.40, p<.01), outperforming traditional tests [30]. | Study with 70 patients & 70 controls [30]. |

| Reaction Time | Novel VR vs. Computerized RT | RTs were significantly longer in VR (p<.001). Moderate-to-strong correlations between platforms (r≥0.642) confirm validity [44]. | Study with 48 participants [44]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Understanding the methodology behind key studies is crucial for evaluating their findings.

Protocol: Comparative Validity of VR Working Memory and Psychomotor Assessments

- Objective: To investigate the convergent validity, user experience, and usability of VR-based versus PC-based assessments of short-term memory, working memory, and psychomotor skills [42].

- Design: Within-subjects comparative study.

- Participants: 66 adults (aged 18-45) [42].

- Intervention & Comparison:

- VR Assessments: Administered using an HTC Vive Pro Eye headset. Participants performed immersive versions of the Digit Span Task (DST), Corsi Block Task (CBT), and Deary-Liewald Reaction Time Task (DLRTT) using hand controllers for naturalistic interaction [42].

- PC Assessments: Identical cognitive tasks were hosted on the PsyToolkit platform. Participants responded using standard computer interfaces (e.g., keyboard, mouse) [42].

- Outcome Measures: Primary outcomes were performance scores on cognitive tasks. Secondary measures included user experience and system usability ratings, and the influence of demographic and IT skills [42].

Protocol: VR Cognitive Training for Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of a commercial VR game on sustained attention (primary outcome), processing speed, and working memory (secondary outcomes) after TBI [43].

- Design: Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) with 1:1 allocation.

- Participants: 100 individuals aged 18-65 with complicated mild-to-severe TBI [43].

- Intervention: The VR training group played Beat Saber for 30 minutes per day, 5 days a week, for 5 weeks. This rhythm game requires sustained attention and rapid motor responses [43].

- Control: The active control group received information about everyday activities that might impact cognition [43].

- Outcome Measures: The primary outcome was sustained attention measured by the Conners' Continuous Performance Test (CPT-3). Secondary outcomes included processing speed (CPT-3 Hit Reaction Time), working memory (WAIS-IV digit span), and self-report measures of executive function and quality of life [43].

Protocol: Ecological Validity of a VR Kitchen Task

- Objective: To validate the novel Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality (CAVIR) test and investigate its association with neuropsychological performance and real-world activities of daily living (ADL) [30].

- Design: Cross-sectional study.

- Participants: 70 symptomatically stable patients with mood or psychosis spectrum disorders and 70 healthy controls [30].

- Intervention: All participants completed the CAVIR test, which involves performing daily-life cognitive tasks within an immersive virtual reality kitchen scenario [30].

- Comparison: Participants also completed a standard battery of neuropsychological tests. In patients, ADL ability was evaluated using the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) [30].

- Outcome Measures: The primary outcomes were the correlation between global CAVIR performance and global neuropsychological test scores, and the correlation between CAVIR performance and AMPS scores in patients [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions for researchers designing VR neuropsychological assessment studies.

| Tool / Solution | Primary Function in Research | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Presents immersive, 3D environments; blocks external distractions. | HTC Vive Pro Eye (with eye-tracking) used for DST, CBT, and DLRTT assessments [42]. |

| Game-Engine Software | Platform for developing and running controlled, interactive VR assessment scenarios. | Unity 2019.3 used to build ergonomic VR neuropsychological tests [42]. |

| Hand Motion Controllers | Enables naturalistic, embodied interaction with the virtual environment, replacing keyboard/mouse. | SteamVR controllers used to manipulate virtual objects in CBT and DLRTT [42]. |

| Traditional Neuropsychological Batteries | Provides the standardized, gold-standard metric for establishing convergent validity of new VR tools. | WAIS-IV Digit Span, Corsi Block, and CPT-3 used as benchmarks for VR task performance [43] [30] [42]. |

| Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scales | Provides an ecologically valid criterion to test if VR assessments better predict real-world function. | Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) used to validate CAVIR [30]. |

| User Experience & Usability Questionnaires | Quantifies participant acceptance, comfort, and perceived usability of the VR assessment system. | Higher ratings for VR vs. PC assessments on usability and experience metrics [42]. |

VR Assessment Workflow and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for developing and validating a VR-based neuropsychological assessment, leading to its key comparative advantages.

Interpretation of Key Findings

- Ecological Validity is a Key Advantage: The strong point of VR assessment is not necessarily replicating traditional test scores, but in its enhanced ecological validity. The CAVIR test's correlation with daily living skills, where traditional tests showed none, demonstrates VR's unique capacity to predict real-world functioning [30].

- Longer Reaction Times in VR are Informative: While VR reaction times are often slower, this likely reflects the increased cognitive load of more complex, lifelike tasks rather than poor test quality. These measures may be more representative of real-world performance [44].

- VR Mitigates Technological Bias: A significant finding is that performance on traditional PC tests was influenced by age and computing experience, whereas VR performance was largely independent of these factors. This suggests VR could offer a fairer assessment for populations with low digital literacy [42].

- Platform Selection is Goal-Dependent: For isolating specific cognitive processes in a controlled setting, traditional tests remain excellent. For predicting a patient's ability to function in daily life, VR assessments show distinct promise [30] [42].

This case study provides a comparative analysis of the Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality (CAVIR) tool against traditional neuropsychological tests. With growing interest in ecologically valid cognitive assessments, immersive technologies like virtual reality (VR) offer promising alternatives to conventional paper-and-pencil methods. We examine experimental data from the CAVIR validation study, detailing its methodology, performance metrics, and comparative advantages in assessing functional cognitive domains relevant to primary care settings. The findings demonstrate CAVIR's enhanced sensitivity in evaluating daily-life cognitive skills and its stronger correlation with real-world functional outcomes, positioning it as a valuable tool for comprehensive cognitive assessment in mood and psychosis spectrum disorders.

The assessment of neurocognitive functions is pivotal for diagnosing and managing various psychiatric and neurological conditions. Traditional neuropsychological tests, while well-established, often face criticism for their limited ecological validity, as they may not adequately reflect cognitive challenges encountered in daily life [7]. The growing demand for more realistic assessment tools has catalyzed the exploration of immersive technologies, particularly within the broader research on VR and traditional neuropsychological test sensitivity [7].

Extended Reality (XR) technologies, encompassing virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR), have emerged as transformative tools. They create interactive, simulated environments that can closely mimic real-world scenarios, thereby offering a potentially more accurate measure of a person's functional cognitive abilities [41] [7]. A 2025 systematic review on XR for neurocognitive assessment identified 28 relevant studies, the majority of which (n=26) utilized VR-based tools, highlighting the academic and clinical interest in this domain [41] [7].

The CAVIR (Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality) test represents a significant innovation in this field. It is designed as an immersive virtual kitchen scenario to assess daily-life cognitive skills in patients with mood or psychosis spectrum disorders [45]. This case study will objectively compare CAVIR's performance against traditional alternatives, presenting supporting experimental data within the context of primary care.

Methodology: CAVIR Experiment Protocol

Participant Recruitment and Characteristics

The validation study for the CAVIR test employed a case-control design to establish its sensitivity and validity [45].

- Sample Size: The study enrolled a total of 140 participants.

- Clinical Group: 70 symptomatically stable patients with diagnosed mood or psychosis spectrum disorders.

- Control Group: 70 healthy controls matched for relevant demographics.

- Key Inclusion/Exclusion: Patients were required to be symptomatically stable. A noted limitation was the presence of concomitant medication in the clinical group [45].

Assessment Tools and Procedures

Each participant underwent a multi-modal assessment battery to allow for comparative analysis between CAVIR, traditional tests, and functional outcomes.

- CAVIR Test: Participants completed the Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality, which involves performing a series of tasks in an immersive virtual kitchen environment. The test is designed to evaluate cognitive skills as they would be applied in daily life [45].

- Traditional Neuropsychological Tests: A battery of standard neuropsychological tests was administered to all participants to establish convergent validity [45].

- Functional and Clinical Measures:

- Activities of Daily Living (ADL): The Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) was used to objectively evaluate patients' ADL ability, specifically measuring the process skills required for task completion [45].

- Clinical Symptoms: Interviewer-rated scales were used to assess clinical symptom severity.

- Functional Capacity: Performance-based measures were used to evaluate functional capacity.

- Subjective Cognition: Participants' self-reported cognitive perceptions were recorded [45].

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses focused on establishing the validity and utility of the CAVIR test through several key methods [45]:

- Correlational Analysis: Spearman's correlation was used to examine the relationship between global CAVIR performance, global neuropsychological test scores, and ADL process ability.

- Group Comparisons: The sensitivity of CAVIR to cognitive impairments was tested by comparing performance between the patient and control groups.

- Covariate Adjustment: Key analyses, such as the association with ADL ability, were repeated after adjusting for sex and age to ensure robustness of findings.

Results and Comparative Performance Data

Correlation with Traditional Neuropsychological Tests

The CAVIR test demonstrated a statistically significant and moderate positive correlation with traditional neuropsychological test batteries.

Table 1: Correlation between CAVIR and Traditional Neuropsychological Tests

| Assessment Comparison | Correlation Coefficient (rs) | P-value | Sample Size (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global CAVIR performance vs. Global neuropsychological test scores | 0.60 | < 0.001 | 138 |

This correlation of rs(138) = 0.60, p < 0.001 indicates that CAVIR performance shares a meaningful relationship with cognitive abilities measured by traditional tools, thereby supporting its construct validity [45]. However, the strength of the correlation also confirms that CAVIR captures distinct aspects of cognition not fully measured by traditional means.

Predictive Validity for Real-World Functioning

A key finding was CAVIR's superior ability to predict real-world functional outcomes compared to other assessment methods.

Table 2: Association with Activities of Daily Living (ADL) in Patients

| Assessment Method | Correlation with ADL Process Ability (r) | P-value | Statistical Significance after Adjusting for Sex & Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAVIR (Global Performance) | 0.40 | < 0.01 | Yes (p ≤ 0.03) |

| Traditional Neuropsychological Tests | Not Reported | ≥ 0.09 | Not Applicable |

| Interviewer-based Functional Capacity | Not Reported | ≥ 0.09 | Not Applicable |

| Subjective Cognition | Not Reported | ≥ 0.09 | Not Applicable |

The data reveal that CAVIR performance showed a weak-to-moderate significant association with ADL process skills (r(45) = 0.40, p < 0.01), which remained significant after controlling for sex and age. In stark contrast, traditional neuropsychological performance, interviewer-rated functional capacity, and subjective cognition measures showed no significant association with ADL ability (ps ≥ 0.09) [45]. This underscores CAVIR's enhanced ecological validity.

Sensitivity and Discriminative Validity

The CAVIR test proved highly effective in differentiating between patient and control groups, confirming its sensitivity to cognitive impairments associated with psychiatric disorders [45]. Furthermore, the test was able to differentiate between patients who were capable of regular employment and those who were not, highlighting its practical relevance for assessing functional outcomes like workforce participation [45].

Comparative Analysis: VR vs. Traditional Assessment

The findings from the CAVIR study align with broader research on VR's role in clinical assessment. The table below summarizes key comparative characteristics based on the current literature.

Table 3: Characteristics of VR-Based vs. Traditional Neurocognitive Assessment

| Characteristic | VR-Based Assessment (e.g., CAVIR) | Traditional Neuropsychological Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Validity | High - Mimics real-world environments (e.g., kitchen) [45] [7] | Low - Abstract, decontextualized paper-and-pencil tasks [7] |

| Sensitivity to ADL | Significant association with daily-life skills [45] | Often no significant association found [45] |

| Patient Engagement | High - Reported as more immersive and engaging [41] [7] | Variable - Can be repetitive and lack engagement [7] |

| Data Collection | Automated, objective metrics (response times, errors) [7] | Often relies on clinician timing and scoring [7] |

| Primary Advantage | Assesses "shows how" in realistic contexts; better predicts real-world function. | Standardized, extensive normative data; efficient for core cognitive domains. |

| Key Challenge | Cost, technical requirements, need for standardized protocols [41] [7] | Limited ecological validity and predictive power for daily function [45] [7] |

This comparison is supported by a separate systematic review which concluded that XR technologies are "more sensitive, ecologically valid, and engaging compared to traditional assessment tools" [41] [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for VR Cognitive Assessment

Implementing a VR-based assessment like CAVIR requires a specific set of technological and methodological components.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Cognitive Assessment

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example from CAVIR Study |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Hardware | Head-Mounted Display (HMD) and controllers to create a sense of presence and enable interaction. | A specific VR headset and controllers were used for the kitchen scenario [45]. |

| VR Assessment Software | The programmed environment and task logic defining the cognitive assessment scenario. | "Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality (CAVIR)" software with a virtual kitchen [45]. |

| Traditional Test Battery | Standardized neuropsychological tests used for validation and correlation analysis. | A battery of standard tests was administered to all participants [45]. |

| Functional Outcome Measure | An objective tool to measure real-world performance, crucial for establishing ecological validity. | "Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS)" [45]. |

| Data Recording & Analysis Platform | Software to automatically record performance metrics (time, errors, paths) and analyze results. | Automated data collection is a key advantage of XR [7]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The experimental data from the CAVIR study provides compelling evidence for the utility of VR-based assessments in primary care and specialist settings. The moderate correlation with traditional tests ensures that CAVIR measures established cognitive constructs, while its superior link to ADL performance demonstrates a critical advancement over existing tools [45]. This aligns with the broader thesis that VR assessments offer enhanced sensitivity to the cognitive challenges that impact patients' daily lives.

The feasibility of integrating VR into structured assessment protocols has been demonstrated not only in clinical psychology but also in medical education, where VR-based stations have been successfully incorporated into Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) [46]. However, challenges remain, including the initial high costs, need for technical support, and the current lack of standardized protocols across different VR assessment tools [41] [7]. Future research should focus on developing these standards, validating VR assessments in diverse patient populations and primary care settings, and further exploring their cost-effectiveness in long-term health management.

Novel VR Protocols for mTBI, Alzheimer's, and MCI Populations

Virtual Reality (VR) is emerging as a transformative tool in neurocognitive assessment, offering enhanced ecological validity and sensitivity for detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer's disease, and mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). This guide compares the performance of novel VR-based protocols against traditional neuropsychological tests, synthesizing current experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals. Evidence indicates VR assessments demonstrate superior sensitivity in identifying subtle cognitive-motor integration deficits and functional impairments often missed by conventional paper-and-pencil tests, though results vary by clinical population and protocol design.

Traditional neuropsychological assessments like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) have long been standard tools for detecting cognitive impairment. However, these paper-and-pencil tests lack ecological validity as they fail to replicate real-world situations where patients ultimately live and function [11]. Studies indicate these conventional tools explain only 5-21% of variance in patients' daily functioning, risking poor dementia prognosis [11]. The limitations of traditional assessments have accelerated the development of VR-based paradigms that create immersive, ecologically valid environments for detecting subtle neurological deficits.

VR technology offers several distinct advantages for neurocognitive assessment: (1) creation of controlled yet complex environments that mimic real-world challenges; (2) precise measurement of behavioral metrics including response latency, movement trajectory, and hesitation; (3) standardized administration across diverse populations and settings; and (4) enhanced patient engagement through immersive experiences [7]. These capabilities position VR as a powerful methodology for early detection of neurological conditions in both clinical and research settings.

Comparative Performance Data: VR vs. Traditional Assessments

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Conditions

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of VR Assessments vs. Traditional Tools

| Condition | VR Assessment | Traditional Tool | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI | VR Stroop Test | MoCA | 96.7% (hesitation latency) | 92.9% (hesitation latency) | 0.967 | [47] |

| MCI | VR Stroop Test | MoCA | 97.9% (3D trajectory) | 94.6% (3D trajectory) | 0.981 | [47] |

| MCI | Various VR tests | Paper-pencil tests | 89% (pooled) | 91% (pooled) | 0.95 | [48] |

| mTBI | Eye-Tracking/VR | Clinical criteria | Not significant | Not significant | N/A | [49] |

| mTBI | Virtual Tunnel Paradigm | BOT-2 balance test | Significant deficits detected | Not significant | N/A | [50] |

Correlation Between VR and Traditional Executive Function Measures

Table 2: Concurrent Validity of VR Assessments for Executive Function