Decoding Brain Anatomy from Neural Spike Trains: A New Frontier in Neural Coding and Biomedical Research

This article synthesizes recent breakthroughs demonstrating that individual neurons embed robust signatures of their anatomical location within their spike trains—a fundamental and generalizable dimension of the neural code.

Decoding Brain Anatomy from Neural Spike Trains: A New Frontier in Neural Coding and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article synthesizes recent breakthroughs demonstrating that individual neurons embed robust signatures of their anatomical location within their spike trains—a fundamental and generalizable dimension of the neural code. We explore how machine learning models can successfully predict a neuron's anatomical origin across diverse brain regions based solely on spiking activity, a discovery with profound implications for interpreting large-scale neural recordings. The content delves into the foundational principles of this anatomical embedding, examines cutting-edge methodologies for its decoding, and addresses key challenges in data analysis and optimization. For researchers and drug development professionals, we further compare validation strategies and discuss how this paradigm shift enhances our understanding of brain organization, offering novel avenues for diagnosing circuit-level pathologies and developing targeted neurotherapeutics.

The Anatomical Blueprint in Spike Trains: Foundational Principles and Discoveries

Core Concept and Definition

Anatomical embedding refers to the phenomenon where the precise anatomical location of a neuron within the brain is reliably encoded within the temporal patterns of its own spiking activity. This represents a previously overlooked dimension of the neural code, where information about a neuron's physical position is multiplexed with its representations of external stimuli and internal states [1] [2] [3].

Traditional understanding of neural coding has focused primarily on how spike trains represent sensory information, motor commands, or cognitive states. The revolutionary finding that neurons also embed "self-information" about their own anatomical identity fundamentally expands our conceptual framework for understanding neural computation. This anatomical signature persists across different behavioral states and stimulus conditions, suggesting it represents a fundamental property of neural circuit organization rather than a transient functional adaptation [1].

The discovery was enabled by sophisticated machine learning approaches applied to large-scale neural recording datasets, which revealed that spike train patterns contain sufficient information to reliably predict a neuron's anatomical origin across multiple spatial scales—from broad brain regions to specific substructures [1] [3].

Key Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Findings

Decoding Performance Across Anatomical Scales

Table 1: Anatomical Decoding Accuracy from Spike Train Patterns [1] [3]

| Anatomical Level | Specific Structures | Decoding Performance | Key Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Brain Regions | Hippocampus, Midbrain, Thalamus, Visual Cortices | High reliability | Interspike interval distributions |

| Hippocampal Structures | CA1, CA3, Dentate Gyrus, Prosubiculum, Subiculum | Robust separation | Specific ISI patterns and stimulus responses |

| Thalamic Structures | Dorsal Lateral Geniculate, Lateral Posterior Nucleus, Ventral Medial Geniculate | Robust separation | Temporal spiking patterns |

| Visual Cortical Structures | Primary vs. Secondary Areas | Reliable distinction | Laminar position and response properties |

| Individual Secondary Visual Areas | Anterolateral, Anteromedial, Lateral, Posteromedial | Limited separation | Population-level statistics rather than single-neuron signatures |

Generalizability and Robustness Findings

Table 2: Properties of Anatomical Embedding Across Experimental Conditions [1] [3]

| Property | Experimental Demonstration | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Stimulus Generalization | Decoding successful across drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, and spontaneous activity | Anatomical signature is state-independent and stimulus-invariant |

| Cross-Animal Generalization | Classifiers trained on one animal successfully predict anatomy in withheld animals | Conservation of coding principles across individuals |

| Cross-Laboratory Generalization | Models generalize across datasets from different research laboratories | Fundamental biological principle rather than methodological artifact |

| Temporal Features | Anatomical information enriched in specific interspike intervals | Temporal patterning critical for anatomical identity |

| Traditional Metric Limitations | Firing rate alone insufficient for reliable anatomical discrimination | Need for sophisticated pattern analysis of spike timing |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Protocol

The foundational evidence for anatomical embedding comes from rigorous analysis of publicly available large-scale datasets, primarily from the Allen Institute Brain Observatory and Functional Connectivity datasets [1] [3].

Recording Specifications:

- Technology: High-density silicon probes (Neuropixels)

- Subjects: N=58 awake, behaving mice (Brain Observatory: N=32; Functional Connectivity: N=26)

- Stimulus Conditions: Drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, spontaneous activity during blank screen presentations

- Data Type: Timestamps of individual spikes from well-isolated single units

Quality Control Pipeline:

- Spike Sorting: Performed at Allen Institute using standardized pipelines

- Unit Filtering: Application of objective quality metrics including:

- ISI violations thresholding

- Presence ratio requirements

- Amplitude cutoff criteria

- Anatomical Localization: Registration to standardized reference atlases

- Stimulus Alignment: Precise temporal alignment of spike data with stimulus presentations

Machine Learning Classification Framework

The core methodology for detecting anatomical embedding employs supervised machine learning in two distinct validation paradigms [1] [3]:

Transductive Approach:

- All neurons from all animals merged before splitting into training/testing sets

- Preserves capacity to learn within-animal features

- Tests absolute decodability of anatomical location

Inductive Approach:

- Model training on all neurons from a set of animals

- Model testing on neurons from entirely withheld animals

- Tests generalizability of anatomical coding principles across individuals

- Requires that successful learning must transfer to novel subjects

Classifier Architecture:

- Primary Model: Multi-layer perceptron (MLP)

- Input Features: Complete representations of single-unit spiking (e.g., interspike interval distributions)

- Comparative Controls: Traditional measures (firing rate alone) tested for baseline performance

- Validation: Rigorous cross-validation with multiple data splits

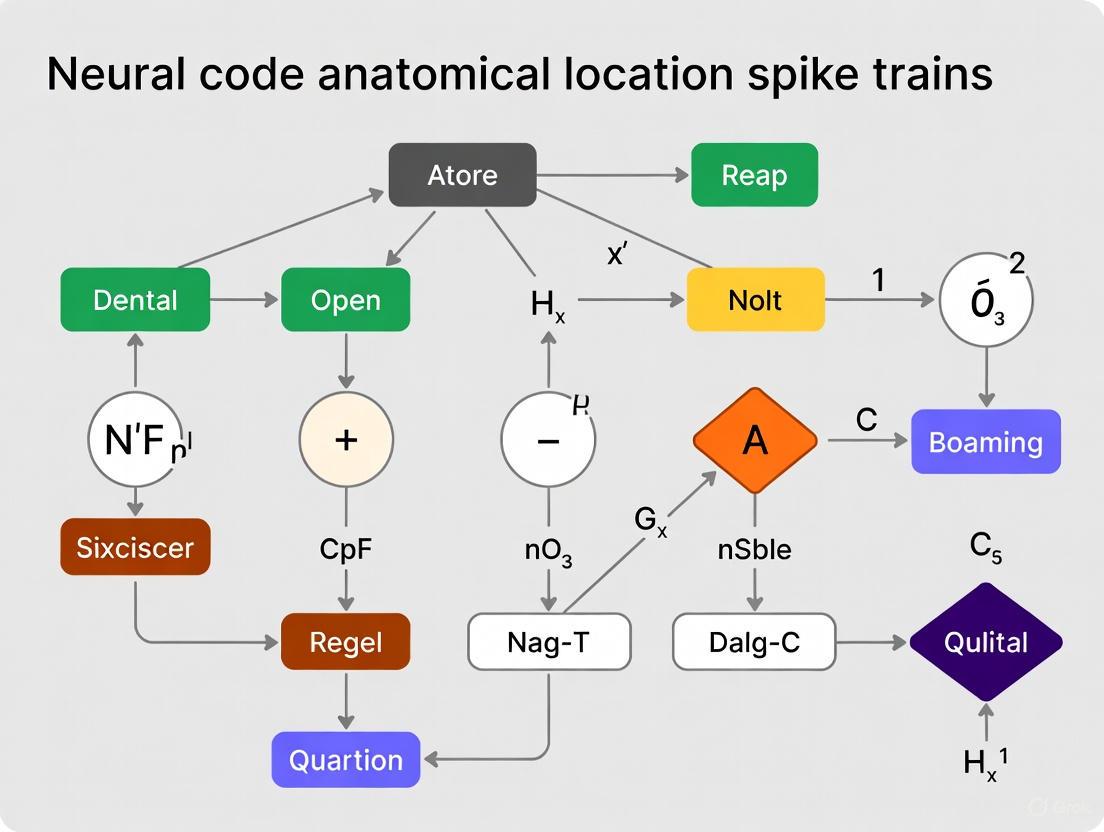

Experimental Workflow for Anatomical Embedding Research

Complementary Research and Theoretical Framework

Network-Level Influences on Spiking Patterns

Recent research demonstrates that the spiking dynamics of individual neurons reflect the structure and function of their underlying neuronal networks. Multifractal analysis of interspike intervals has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for characterizing how network topology shapes individual neuron spiking behavior [4].

Key Findings from Network Analysis:

- Multifractal profiles of ISI sequences are sensitive to network connection densities and architectural features

- These spiking signatures remain relatively consistent across varying stimulus conditions

- The methodology can differentiate between networks optimized for different computational tasks

- Multifractal analysis proves robust in partial observation scenarios where only a subset of neurons is monitored

Specialized Population Codes in Projection Pathways

Research in posterior parietal cortex reveals that neurons projecting to common target areas form specialized population codes with structured correlation patterns that enhance information transmission. These projection-specific populations exhibit [5]:

- Elevated pairwise activity correlations within common projection groups

- Network structures containing both information-limiting and information-enhancing motifs

- Correlation structures that emerge specifically during correct behavioral choices

- Enhanced population-level information about choice variables beyond what individual neurons contribute

Theoretical Foundation: Neural Self-Information Theory

The anatomical embedding phenomenon aligns with the broader "Neural Self-Information Theory," which proposes that neural coding operates on a self-information principle where variability in interspike intervals carries discrete information [6]. This framework suggests:

- Higher-probability ISIs reflecting balanced excitation-inhibition convey minimal information

- Lower-probability ISIs representing rare-occurrence surprisals carry the most information

- This variability-based code is intrinsic to neurons themselves, requiring no external reference point

- Temporally coordinated ISI surprisals across cell populations can generate robust real-time assembly codes

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools [1] [3] [4]

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Solution | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Recording Technology | Neuropixels high-density probes | Large-scale simultaneous recording from hundreds of neurons across multiple brain regions |

| Data Sources | Allen Institute Brain Observatory Dataset | Standardized, publicly available neural recording data with anatomical localization |

| Data Sources | Allen Institute Functional Connectivity Dataset | Complementary dataset with distinct stimulus conditions for validation |

| Computational Framework | Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) classifiers | Decoding anatomical location from spike train patterns |

| Analysis Methods | Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis | Characterizing higher-order statistics of ISI dynamics in relation to network structure |

| Theoretical Models | Vine Copula statistical models | Quantifying multivariate dependencies in neural population data with unidentified outputs |

| Quality Metrics | ISI violation thresholds, presence ratio, amplitude cutoff | Objective filtering of well-isolated single units for analysis |

Conceptual Framework of Anatomical Embedding

Implications and Future Research Directions

The discovery of anatomical embedding in neural spike trains represents a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize information processing in the brain. This phenomenon has broad implications for:

Neurodevelopmental Processes: Anatomical signatures may provide crucial guidance mechanisms during circuit formation and refinement, potentially serving as self-identifying markers that help establish proper connectivity patterns during development [1] [3].

Multimodal Integration: The reliable encoding of anatomical origin could facilitate the parsing of inputs from different sensory modalities by providing intrinsic metadata about information sources, potentially resolving binding problems in complex sensory processing [1].

Large-Scale Neural Recording Interpretation: As neurotechnologies increasingly enable simultaneous monitoring of thousands of neurons across distributed networks, anatomical embedding provides a framework for interpreting these complex datasets and potentially inferring connectivity relationships from spiking patterns alone [1] [4].

Clinical Applications: The principles of anatomical embedding could revolutionize electrode localization in clinical recording settings, providing computational approximations of anatomical position that complement traditional imaging methods, particularly for implanted arrays where precise localization remains challenging [1] [2].

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the developmental timeline of anatomical signature emergence, investigating their conservation across species, exploring their potential plasticity in response to experience or injury, and developing more sophisticated decoding algorithms that can extract finer-grained anatomical information from spike train patterns.

A groundbreaking study demonstrates that machine learning (ML) models can accurately predict the anatomical location of individual neurons based solely on their spiking activity. This finding provides compelling evidence that brain structure is robustly embedded within the neural code, a principle that generalizes across different animals and experimental conditions [1]. The discovery introduces a novel, activity-based method for estimating electrode localization in vivo and challenges traditional paradigms by revealing that anatomical information is multiplexed with external stimulus encoding in spike trains.

Quantitative Evidence: Decoding Performance

The following tables summarize the quantitative results from key experiments that decoded anatomical location from neuronal spike trains.

Table 1: Anatomical Decoding Performance Across Spatial Scales

| Brain Region / Structure | Spatial Scale | Decoding Performance & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Brain Regions [1] | Macro (Hippocampus, Midbrain, Thalamus, Visual Cortices) | Machine learning models reliably decoded anatomical location from spike patterns. Performance was consistent across diverse stimulus conditions (drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, spontaneous activity). |

| Hippocampal Structures [1] | Meso (CA1, CA3, Dentate Gyrus, etc.) | Anatomical structures within the hippocampus were "robustly separable" based on their spike patterns. |

| Thalamic Structures [1] | Meso (dLGN, LP, VPM, etc.) | Anatomical structures within the thalamus were "robustly separable" based on their spike patterns. |

| Visual Cortical Structures [1] | Meso (Primary vs. Secondary) | Location was robustly decoded at the level of layers and primary versus secondary areas. The model did not robustly separate individual secondary structures. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Metrics from the Primary Study

| Experimental Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Dataset | Brain Observatory & Functional Connectivity from the Allen Institute [1] |

| Subjects | N=58 awake, behaving mice [1] |

| Neurons Recorded | Thousands of neurons, recorded with high-density Neuropixels probes [1] |

| Stimulus Conditions | Drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, and spontaneous activity during blank screen presentations [1] |

| Key ML Model | Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) [1] |

| Critical Feature | Interspike Interval (ISI) distribution [1] |

| Generalization | Anatomical signatures generalized across animals and different research laboratories [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The core evidence for this finding comes from a rigorous experimental and computational pipeline.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

This protocol is based on the methods from the primary study [1].

- Step 1: Animal Preparation and Recording. Conduct high-density electrophysiological recordings from awake, behaving mice using Neuropixels probes. Ensure recordings span multiple brain regions, including the hippocampus, thalamus, midbrain, and visual cortices.

- Step 2: Stimulus Presentation. Expose subjects to diverse visual stimuli to sample a wide range of neural states. The essential stimuli include:

- Drifting Gratings: Standardized, repetitive visual stimuli.

- Naturalistic Movies: Complex, dynamic visual stimuli.

- Spontaneous Activity: Recordings during a blank screen to capture baseline, non-driven activity.

- Step 3: Spike Sorting and Quality Control. Process raw data to isolate single units (individual neurons). Apply strict quality metrics to include only well-isolated units:

- ISI Violations: Filter out units with refractory period violations.

- Presence Ratio: Ensure the neuron was active throughout the recording.

- Amplitude Cutoff: Filter based on spike amplitude stability.

- Step 4: Anatomical Localization. Assign each recorded neuron to its anatomical location using established atlases, defining both large-scale regions and fine-grained structures.

Feature Engineering and Model Training

- Step 1: Feature Extraction. For each neuron, extract representations of its spiking activity. The study found that traditional measures like average firing rate were insufficient for reliable decoding. The most informative feature was the Interspike Interval (ISI) distribution, which provides a more complete representation of spike timing patterns [1].

- Step 2: Model Selection and Training. Employ a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), a class of artificial neural network, as the primary decoding model. Train the model to classify a neuron's anatomical location using its spiking activity features as input.

- Step 3: Cross-Validation and Generalization Testing. Validate model performance using robust cross-validation techniques. Critically, test for generalization by training the model on data from one set of animals and testing it on data from entirely different animals, even those recorded in separate laboratories [1].

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Workflow for Decoding Anatomical Location from Spikes

Classifier Architecture and Information Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Anatomical Decoding Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Electrophysiology Probes | To record spiking activity from hundreds of neurons across multiple brain regions simultaneously. | Neuropixels probes [1] |

| Data Acquisition System | To capture and digitize neural signals with high temporal resolution. | System compatible with high-channel-count probes. |

| Spike Sorting Software | To isolate single-unit activity from raw voltage traces. | Software implementing algorithms for clustering spikes and calculating quality metrics (ISI violations, presence ratio) [1]. |

| Anatomical Reference Atlas | To assign recorded neurons to specific brain regions. | Standardized mouse brain atlas (e.g., Allen Brain Atlas). |

| Machine Learning Framework | To build and train classifiers for decoding anatomical location. | Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) models; frameworks supporting deep learning (e.g., Python PyTorch, TensorFlow) [1]. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | To deliver controlled visual or other sensory stimuli during recording. | Software capable of presenting drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, and blank screens [1]. |

Generalizability Across Animals, Labs, and Stimulus Conditions

Cracking the neural code—the fundamental rule by which information is represented by patterns of action potentials in the brain—represents one of the most significant challenges in neuroscience [6]. This pursuit is fundamentally complicated by the problem of generalizability: can findings about neural coding schemes obtained from one animal species, in one laboratory, under a specific set of stimulus conditions, be reliably applied to other species, experimental setups, or contexts? The neural code must be robust enough to support consistent perception and behavior despite tremendous variability in both neural activity and environmental conditions. This whitepaper examines the key barriers to generalizability and synthesizes emerging evidence and methodologies that promise more universal principles of neural computation, with critical implications for drug development and therapeutic targeting.

A core manifestation of this challenge is what can be termed "The Live Brain's Problem"—how information is dynamically represented by spike patterns in real time across varying conditions [6]. Conversely, "The Dead Brain's Problem" concerns the underlying wiring logic that remains constant. A critical stumbling block is neuronal variability: spikes display immense variability across trials, even in identical resting states, which has traditionally been treated as noise but may be integral to the code itself [6].

Quantitative Evidence: Comparative Studies on Learning and Generalization

Cross-Species Rule Learning and Generalization

Recent research directly comparing nonhuman primates and humans reveals both commonalities and critical divergences in neural coding capabilities. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from a study on abstract rule learning:

Table 1: Comparative Learning Performance in Macaques vs. Humans

| Performance Metric | Rhesus Macaques | Human Participants | Implications for Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | Slow, gradual learning (>10,000 trials to criterion) [7] | Rapid learning | Species-specific learning mechanisms limit direct generalization. |

| Stimulus Generalization | Successfully generalized rules to novel colored stimuli within the same modality [7] | Successfully generalized rules to novel colored stimuli [7] | Core rule-learning capability may generalize across primate species. |

| Cross-Modal Generalization | Failed to generalize rules from color to shape domains [7] | Successfully generalized rules from color to shape [7] | Abstract, flexible representation may be uniquely human, limiting generalization. |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Limited flexibility in rule switching [7] | High flexibility in rule switching [7] | Fundamental differences in executive control circuits. |

Threat Intensity and Fear Generalization Gradients

Research in Pavlovian fear conditioning further illustrates how a single experimental variable—threat intensity—can dramatically alter a fundamental neural process: fear generalization.

Table 2: Impact of Threat Intensity on Fear Generalization in Humans

| Experimental Condition | Low-Intensity US | High-Intensity US | Neural & Behavioral Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditioned Stimulus (US) | Low-intensity electrical shock [8] | High-intensity shock + 98dB noise + looming snake image [8] | Ecological validity; mimics complex, multimodal real-world threats [8]. |

| Acquisition of Conditioned Fear | No significant effect on initial acquisition [8] | No significant effect on initial acquisition [8] | Threat intensity dissociates acquisition from generalization processes. |

| Generalization Gradient | Specific, sharp gradient centered on CS+ [8] | Widespread, flat generalization gradient [8] | High threat intensity induces overgeneralization, a hallmark of trauma-related disorders [8]. |

| Autonomic Arousal (SCR) | Limited generalization to intermediate tones [8] | Widespread generalization to intermediate and novel tones [8] | Direct link between threat intensity and generalization of physiological responses. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Generalizability

This protocol is designed to test the generalizability of abstract rule representations across species and stimulus domains [7].

- Task Design: Three-Alternative Forced-Choice (3AFC). Participants are simultaneously presented with three visual sequences on a touchscreen, each conforming to one of three abstract rules: 'ABA', 'AAB', or 'BAA'.

- Stimuli: On every trial, the "A" and "B" elements are generated from a specified category (e.g., color or shape) but are trial-unique to prevent learning of specific stimulus-response associations, thereby forcing reliance on the abstract rule.

- Training: Participants are assigned one rule as "correct." Selections of the correct sequence yield positive feedback (e.g., green screen, reward); incorrect selections yield negative feedback.

- Generalization Testing:

- Within-Domain: Continued testing with novel stimuli from the trained category (e.g., new colors).

- Cross-Domain: Critical test where the rule structure is maintained, but the stimulus category is changed (e.g., from color to shape). Successful performance indicates robust, flexible rule representation.

- Species Application: Used with both rhesus macaques and humans to enable direct cross-species comparison of learning rate and generalization capability.

Protocol 2: Threat-Sensitive Fear Generalization

This protocol examines how the intensity of an aversive event shapes the breadth of fear generalization, modeling continuum from adaptive fear to overgeneralization seen in anxiety disorders [8].

- Participants: Healthy volunteers in between-subjects design (Low-Intensity vs. High-Intensity US groups).

- US Calibration:

- Low-Intensity Group: Electrical shock is calibrated to a subjective level of "very low" to "low" intensity.

- High-Intensity Group: Shock is calibrated to "high-intensity" and augmented with a simultaneous 98dB burst of white noise and a looming image of a snake to create a multimodal, ecologically valid threat [8].

- Fear Conditioning Phase:

- Discriminative fear conditioning where one tone (CS+) is paired with the US, and another tone (CS-) is unpaired.

- Generalization Test Phase:

- Conducted after a 5-minute break.

- Presents a range of novel tones that span a frequency continuum between and beyond the CS- and CS+.

- The primary dependent measure is Skin Conductance Response (SCR), an index of autonomic arousal, to these generalization stimuli.

- Data Analysis: Generalization gradients are plotted for each group, showing how fear responses change as the test stimulus becomes less similar to the original CS+.

Conceptual and Computational Frameworks

Neural Self-Information Theory: Rethinking Variability

Challenging the traditional noise-centric view, the Neural Self-Information Theory proposes that the variability in the time durations between spikes (Inter-Spike Intervals, or ISIs) is not noise but the core carrier of information [6].

- The Core Principle: Each ISI carries an amount of "self-information" inversely related to its probability of occurrence. High-probability, common ISIs reflect a balanced ground state and convey minimal information. Low-probability, rare ISIs (e.g., extremely short or long silences) constitute "surprisals" and carry the most information [6].

- Implications for Generalizability:

- This coding scheme is intrinsic to individual neurons, reducing the dependency on external reference points set by an observer, which may enhance its robustness across conditions.

- It provides a unified framework for understanding how temporally coordinated ISI "surprisals" across a population of neurons can give rise to robust real-time cell-assembly codes [6].

Predictive Processing and Neural Generative Coding

The Neural Generative Coding (NGC) framework offers a brain-inspired model for how neural systems learn generative models of their environment, based on the theory of predictive processing [9].

- Core Mechanism: Neurons form a hierarchy where neurons at one level predict the activity of neurons at another level. Synaptic weights are adjusted locally based on the mismatch (prediction error) between a neuron's expectations and the observed signals from connected neurons [9].

- Contrast with Backpropagation: Unlike standard backpropagation, which requires non-local, backward transmission of error signals, NGC relies on local computation, making it more biologically plausible and potentially more robust [9].

- Generalizability Advantage: Models trained under the NGC framework have been shown to not only perform well on their primary task (e.g., pattern generation) but also to generalize better to tasks they were not directly trained on, such as classification and pattern completion [9].

Experimental Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Workflow for Cross-Species Rule Learning Study

The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow used to assess abstract rule learning and generalization in macaques and humans, highlighting the points of comparison.

Cross-Species Rule Learning Workflow

Predictive Processing in Neural Generative Coding

This diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the Neural Generative Coding (NGC) framework, where local computation and prediction errors drive learning.

NGC Predictive Processing Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Neural Coding and Generalization Studies

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Example Use Case | Considerations for Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass Medical Instruments Stimulator | Delivers precise electrical stimulation as an aversive Unconditioned Stimulus (US) [8]. | Pavlovian fear conditioning in humans [8]. | Subjective pain tolerance and skin impedance vary; requires per-subject calibration [8]. |

| Trial-Unique Visual Stimuli | Visual elements (colors, shapes) generated for a single trial to prevent specific stimulus learning [7]. | Abstract rule learning tasks (e.g., 3AFC) [7]. | Ensures measurement of abstract rule generalization, not memory for specific items. |

| Multimodal Aversive US | Combined shock, loud noise (~98dB), and looming images to create high-intensity threat [8]. | Modeling high-intensity threat for fear generalization studies [8]. | Increases ecological validity and ethical intensity ceiling compared to shock alone [8]. |

| Touchscreen 3AFC Apparatus | Presents visual choices and records behavioral responses in non-human primates [7]. | Cross-species cognitive testing [7]. | Allows for identical or highly similar task structures across species, facilitating direct comparison. |

| Skin Conductance Response (SCR) Apparatus | Measures autonomic arousal via changes in skin conductivity [8]. | Quantifying fear responses during conditioning and generalization tests [8]. | Provides an objective, continuous physiological measure that is comparable across labs and subjects. |

Foundational to understanding the brain is the question of what information is carried in a neuron's spiking activity. The concept of a neural code has emerged wherein neuronal spiking is determined by inputs, including stimuli, and noise [1] [3]. While it is widely understood that neurons encode diverse information about external stimuli and internal states, whether individual neurons also embed information about their own anatomical location within their spike patterns remained largely unexplored until recently [1] [3].

Historically, the null hypothesis has been that the impact of anatomy on a neuron's activity is either nonexistent or unremarkable, supported by observations that neurons' outputs primarily reflect their inputs along with noise [3]. However, new research employing machine learning approaches and high-density neural recordings has begun to challenge this view, revealing that information about brain regions and fine-grained structures can be reliably decoded from spike train patterns alone [1] [3]. This discovery reveals a generalizable dimension of the neural code where anatomical information is multiplexed with the encoding of external stimuli and internal states, providing new insights into the relationship between brain structure and function [1].

Theoretical Frameworks of Neural Coding

Fundamental Coding Schemes

Neural coding refers to the relationship between a stimulus and its respective neuronal responses, and the signalling relationships among networks of neurons in an ensemble [10]. Action potentials, which act as the primary carrier of information in biological neural networks, are generally uniform regardless of the type of stimulus or the specific type of neuron [10]. The study of neural coding involves measuring and characterizing how stimulus attributes are represented by neuron action potentials or spikes [10].

Two primary coding schemes have been hypothesized in neuroscience:

Rate Coding: This traditional coding scheme assumes that most information about the stimulus is contained in the firing rate of the neuron. As the intensity of a stimulus increases, the frequency or rate of action potentials increases [10]. Rate coding is inefficient but highly robust with respect to interspike interval 'noise' [10].

Temporal Coding: When precise spike timing or high-frequency firing-rate fluctuations are found to carry information, the neural code is often identified as a temporal code [10]. A number of studies have found that the temporal resolution of the neural code is on a millisecond time scale, indicating that precise spike timing is a significant element in neural coding [10].

Spatial Coding and Population Coding

Spatial coding can be contrasted with temporal coding in that a spatial code relies on the identity of a neural element to convey information—for example, two stimuli evoke responses in different subsets of cells [11]. Population coding, where all neurons in a population contribute to the code for a given stimulus, would be one example of spatial coding [11]. This might take the form of a population vector constructed by the weighted average firing rates across neurons that would specify the identity of a stimulus [11].

The success of neuroimaging methods like fMRI places constraints on the nature of the neural code, suggesting that for fMRI to recover neural similarity spaces given its limitations, the neural code must be smooth at the voxel and functional level such that similar stimuli engender similar internal representations [12]. This success is consistent with proposed neural coding schemes such as population coding in cases where neurons with similar tunings spatially cluster [12].

Experimental Evidence: Decoding Anatomical Location from Spike Trains

Research Design and Datasets

Recent research has employed a supervised machine learning approach to analyze publicly available datasets of high-density, multi-region, single-unit recordings in awake and behaving mice [1] [3]. To evaluate whether individual neurons embed reliable information about their structural localization in their spike trains, researchers utilized datasets from the Allen Institute, specifically the Brain Observatory and Functional Connectivity datasets [1] [3]. These datasets comprise tens of thousands of neurons recorded with high-density silicon probes (Neuropixels) in a total of N=58 mice (BO N=32, FC N=26) [1].

The analysis included recordings during various stimulus conditions, including drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, and spontaneous activity during blank screen presentations [1] [3]. Studies involved only the timestamps of individual spikes from well-isolated units, filtered according to objective quality metrics such as ISI violations, presence ratio, and amplitude cutoff [1]. Neurons were classified at multiple anatomical levels:

- Large-scale brain regions: Hippocampus, midbrain, thalamus, and visual cortices

- Hippocampal structures: CA1, CA3, dentate gyrus, prosubiculum, and subiculum

- Thalamic structures: Ethmoid nucleus, dorsal lateral geniculate, lateral posterior nucleus, and others

- Visual cortical structures: Primary, anterolateral, anteromedial, lateral, posteromedial, rostrolateral [1]

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for decoding anatomical location from neural spike trains.

Key Findings and Quantitative Results

The research demonstrated that machine learning models, specifically multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), can predict a neuron's anatomical location across multiple brain regions and structures based solely on its spiking activity [1] [3]. This anatomical signature generalizes across animals and even across different research laboratories, suggesting a fundamental principle of neural organization [1].

Examination of trained classifiers revealed that anatomical information is enriched in specific interspike intervals as well as responses to stimuli [1]. Traditional measures of neuronal activity (e.g., firing rate) alone were unable to reliably distinguish anatomical location, but more complete representations of single unit spiking (e.g., interspike interval distribution) enabled successful decoding [1].

Table 1: Spatial Resolution of Anatomical Decoding Across Neural Structures

| Anatomical Level | Structures Identified | Decoding Performance | Key Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-scale Regions | Hippocampus, Midbrain, Thalamus, Visual Cortex | High accuracy | Interspike interval distributions, response patterns to stimuli |

| Hippocampal Structures | CA1, CA3, Dentate Gyrus, Prosubiculum, Subiculum | Robustly separable | Spike timing patterns, distinct computational rules |

| Thalamic Structures | Dorsal Lateral Geniculate, Lateral Posterior Nucleus, others | Robustly separable | Specialized response properties |

| Visual Cortical Structures | Primary vs. Secondary Areas | Reliable separation | Layered organization, response characteristics |

| Individual Secondary Visual Areas | Anterolateral, Anteromedial, Posteromedial | Limited separation | Population-level statistical differences |

The spatial resolution of anatomical embedding varies significantly across different brain areas. Within the visual isocortex, anatomical embedding is robust at the level of layers and primary versus secondary areas but does not robustly separate individual secondary structures [1]. In contrast, structures within the hippocampus and thalamus are robustly separable based on their spike patterns [1].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Neural Recording and Data Processing

The experimental protocol for investigating anatomical encoding in spike trains requires specific methodologies:

Animal Preparation and Recording: Recordings are conducted from awake, behaving mice using high-density silicon probes (Neuropixels) to ensure natural neural activity patterns [1] [3]. Multiple brain regions must be recorded simultaneously or in a standardized fashion to enable comparative analysis.

Stimulus Presentation: Animals are presented with diverse stimulus conditions including:

- Drifting gratings: Standard visual stimuli to activate visual pathways

- Naturalistic movies: Complex ecological stimuli engaging multiple processing streams

- Spontaneous activity: Recordings during blank screen presentations to isolate internal processing [1]

Spike Sorting and Quality Control: Raw data undergo spike sorting to identify well-isolated single units [1]. Units are filtered according to objective quality metrics:

- ISI violations: To ensure proper isolation of single units

- Presence ratio: To confirm consistent recording throughout sessions

- Amplitude cutoff: To exclude poorly isolated units [1]

Feature Extraction: For each neuron, multiple features are extracted from spike trains:

- Interspike interval distributions: Comprehensive histograms of timing between spikes

- Firing rate statistics: Mean, variance, and other moment-based features

- Stimulus response profiles: Patterns of activation across different stimulus conditions [1]

Machine Learning Classification

The core analytical protocol involves supervised machine learning:

Data Partitioning: Two approaches are used to test generalizability:

- Transductive approach: All neurons from all animals merged before splitting into training and testing sets

- Inductive approach: Model training on all neurons from a set of animals, with testing on neurons from entirely withheld animals [1]

Classifier Training: Multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) are trained to predict anatomical location from spike train features [1]. These neural networks learn complex, non-linear relationships between spike timing patterns and anatomical labels.

Model Interpretation: Analysis of trained models to identify which features (specific interspike intervals, response characteristics) are most informative for anatomical discrimination [1].

Diagram 2: Machine learning framework for anatomical location decoding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Neural Coding Studies

| Research Tool | Specification/Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density silicon probes | Simultaneous recording from thousands of neurons across multiple brain regions with precise spatial localization [1] [3] |

| Allen Institute Datasets | Brain Observatory, Functional Connectivity | Standardized, large-scale neural recording data from awake, behaving mice with anatomical localization [1] |

| Spike Sorting Algorithms | Software tools (Kilosort, IronClust, etc.) | Identification of single-unit activity from raw electrical signals, crucial for isolating individual neurons [1] |

| Multi-layer Perceptrons (MLPs) | Deep learning architecture | Classification of anatomical location from complex spike train features, learning non-linear relationships [1] |

| Interspike Interval (ISI) Metrics | Quantitative analysis | Fundamental feature for distinguishing anatomical origin, captures temporal coding properties [1] |

| Quality Control Metrics | ISI violations, presence ratio, amplitude cutoff | Objective criteria for including only well-isolated, consistently recorded units in analysis [1] |

Implications and Future Directions

Theoretical Implications for Neural Coding

The discovery that anatomical information is embedded in spike trains has profound implications for our understanding of the neural code. This finding suggests that the brain employs a multiplexed coding scheme where information about a neuron's own identity and location is embedded alongside information about external stimuli and internal states [1]. This anatomical embedding may facilitate:

- Neurodevelopmental processes: Providing guidance for circuit formation and refinement [1] [3]

- Multimodal integration: Helping downstream structures interpret the source and reliability of incoming information [1]

- Efficient wiring: Optimizing connection patterns based on developmental rules [1]

The research also demonstrates that different brain regions implement distinct computational rules reflected in their characteristic spiking patterns [1]. This regional specialization goes beyond broad functional differences to encompass fundamental differences in how information is processed and transmitted.

Applications and Technological Potential

This research has immediate practical applications for neuroscience research:

- In vivo electrode localization: Computational approximations of anatomy can support the localization of recording electrodes during experiments, complementing traditional histological methods [1]

- Large-scale neural recording interpretation: Provides a framework for interpreting the organization of neural activity in high-density recordings [1]

- Brain-machine interfaces: Could enhance decoding algorithms by incorporating anatomical priors into signal interpretation

The BRAIN Initiative has identified the analysis of circuits of interacting neurons as particularly rich in opportunity, with potential for revolutionary advances [13]. Understanding how anatomical information is embedded in neural activity contributes directly to this goal of producing a dynamic picture of the functioning brain [13].

Future Research Directions

Future research in this area will likely focus on:

- Cellular and molecular mechanisms: Identifying the biological bases for anatomically distinct spiking patterns

- Developmental trajectories: Understanding how anatomical signatures emerge during brain development

- Cross-species conservation: Investigating whether similar anatomical coding principles exist across species

- Functional significance: Determining how anatomical information in spike trains contributes to neural computation

As expressed in the BRAIN 2025 vision, we can expect to "discover new forms of neural coding as exciting as the discovery of place cells, and new forms of neural dynamics that underlie neural computations" [13]. The discovery of anatomical embedding in spike trains represents a significant step toward this goal, revealing a previously unrecognized dimension of the neural code that bridges the gap between brain structure and function.

Interspike intervals (ISIs), the temporal gaps between consecutive action potentials, serve as fundamental carriers of information in the nervous system. The neural code utilizes multiple representational strategies, including which specific neural channels are activated ("place" codes), their level of activation (rate codes), and temporal patterns of spikes (interspike interval codes) [14]. ISI coding represents a distinct form of information representation where the time-varying distribution of interspike intervals can represent parameters of the statistical context of stimuli [15]. This temporal coding scheme enables neurons to convey information beyond what is possible through firing rates alone, embedding critical details about stimulus qualities, anatomical location, and behavioral context directly into spike timing patterns.

The significance of ISI analysis extends to its ability to resolve ambiguities introduced by adaptive processes in neural systems. For many sensory systems, the mapping between stimulus input and spiking output depends on statistical properties of the stimulus [15]. ISI distributions provide a mechanism to decode information about stimulus variance and resolve these potential ambiguities, demonstrating their crucial role in maintaining robust information transmission under varying environmental conditions.

Core Principles of ISI-Based Information Encoding

Temporal Coding Through Interspike Intervals

Interspike interval coding operates through precise temporal relationships between spikes, independent of which specific neurons generate the activity. In the auditory system, for instance, pitch perception is mediated by temporal correlations between spikes across many fibers, where population-interval distributions reflect the correlation structure of the stimulus after cochlear filtering [14]. This form of coding is remarkably robust—even when information about the identities of particular fibers and their tunings is discarded, the resulting sensory representation remains highly accurate [14].

Stimulus coding through ISI statistics can occur through two primary mechanisms: extrinsically-impressed response patterns driven by stimulus-driven structure, and activation of intrinsic response patterns such as stimulus-specific impulse response shapes [14]. This dual mechanism allows for both faithful representation of external stimuli and generation of context-dependent internal representations.

Anatomical Embedding in Spike Trains

Recent research reveals that individual neurons embed reliable information about their anatomical location within their spiking activity. Machine learning models can predict a neuron's anatomical location across multiple brain regions and structures based solely on its spiking patterns [1]. This anatomical embedding persists across various stimulus conditions, including drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, and spontaneous activity, and generalizes across animals and different research laboratories [1].

The information about anatomical origin is enriched in specific interspike intervals as well as responses to stimuli [1]. This suggests a fundamental principle of neural organization where anatomical information is multiplexed with the encoding of external stimuli and internal states, providing a generalizable dimension of the neural code that has broad implications for neurodevelopment, multimodal integration, and the interpretation of large-scale neuronal recordings.

Quantitative Characterization of ISI Information Carrying Capacity

Information-Theoretic Measures of ISI Coding

The information-carrying capacity of interspike intervals can be quantified using information-theoretic approaches that determine stimulus-related information content in spike trains [14]. Neurons in the primary visual cortex (V1) transmit between 5 and 30 bits of information per second in response to rapidly varying, pseudorandom stimuli, with an efficiency of approximately 25% [16].

The Kullback-Leibler divergence (DKL) provides a statistical measure to quantify differences between probability distributions of ISIs generated under different stimulus conditions [15]. This measure is related to mutual information and quantifies the intrinsic classification difficulty for distinguishing between different stimulus statistics based on ISI distributions. A one-bit increase in DKL corresponds to a twofold decrease in error probability, establishing the fundamental limits on decoding performance based on ISI statistics [15].

Table 1: Information-Theoretic Measures of ISI Coding Capacity

| Measure | Typical Values | Experimental Context | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Rate | 5-30 bits/sec | Primate V1 neurons to varying stimuli [16] | Raw data transmission capacity |

| Transmission Efficiency | ~25% | Primate V1 neurons [16] | Proportion of theoretical maximum achieved |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence | Variable based on stimulus differences | Fly H1 visual neuron [15] | Quantifies discriminability between stimulus conditions |

ISI Variability and Firing Patterns

The coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the standard deviation of ISIs divided by the mean ISI, provides a key metric for characterizing firing regularity. Small CV values close to 0 indicate regular firing, whereas values close to or greater than 1 indicate irregular firing [17]. Head direction (HD) cells in the rat anterodorsal thalamus demonstrate highly variable ISIs with a mean CV of 0.681 when the animal's head direction is maintained within ±6° of the cell's preferred firing direction [17].

This irregularity persists across different directional tuning positions, with similar CV values observed at head directions ±24° away from the preferred direction [17]. The consistency of this variability across recording sessions suggests that the degree of variability in cell spiking represents a characteristic property for each cell type, potentially reflecting specific computational functions or circuit positions.

Table 2: Interspike Interval Variability Across Neural Systems

| Neuron Type/Brain Region | Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Experimental Conditions | Implications for Coding Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head Direction Cells (ADN) | 0.681 (mean) | Rat foraging, head within ±6° of PFD [17] | Irregular firing at fine timescales |

| Visual Cortical Neurons | 0.5-1.0 [17] | Constant stimulus conditions | Predominantly irregular firing |

| Primate V1 Neurons | Class-dependent | m-sequence stimuli [16] | Subset-specific regularity |

Experimental Methodologies for ISI Analysis

Spike Train Recording and Preprocessing

Modern ISI analysis begins with high-density recordings from large populations of neurons using advanced electrophysiological techniques. The Allen Institute Brain Observatory and Functional Connectivity datasets exemplify this approach, comprising tens of thousands of neurons recorded with high-density silicon probes (Neuropixels) in awake, behaving mice [1]. Critical preprocessing steps include spike sorting to isolate single units and application of quality filters based on metrics such as ISI violations, presence ratio, and amplitude cutoff to ensure data integrity [1].

For quantitative analysis, spike times are recorded with high temporal precision—often to the nearest 0.1 msec for cortical neurons [16]—and assigned to precise time bins corresponding to stimulus frames or behavioral measurements. This high temporal resolution is essential for capturing the fine-scale temporal patterns that carry information in ISI distributions.

Receptive Field Mapping Through Reverse Correlation

Reverse correlation techniques, including spike-triggered averaging, enable detailed mapping of neuronal spatiotemporal receptive fields [16]. This process involves cross-correlating evoked spike trains with structured stimuli such as m-sequences to derive the average stimulus preceding each spike [16]. The resulting receptive field maps represent spatial snapshots sequential in time, depicting the average change in contrast in stimulus pixels that significantly modulated neuronal response.

For non-linear systems such as V1 neurons, these maps represent the linear functions that best fit the full response, providing insight into the feature selectivity of the neuron while acknowledging the limitations of linear approximations for complex neural processing [16].

Information Theory and Machine Learning Approaches

Information-theoretic analysis of spike trains involves dividing spike trains into time bins that may contain zero, one, or multiple spikes [16]. The possible spike counts in each bin constitute "letters" in the neuron's response alphabet, with sequences of these letters forming "words" that characterize the neural response [16]. The information transmitted by the neuron is calculated as signal entropy minus noise entropy, where signal entropy derives from the total set of words spoken during the response and noise entropy derives from words spoken at specific times averaged across the response duration.

Machine learning approaches, particularly multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), can decode anatomical location from more complete representations of single unit spiking, including interspike interval distributions [1]. These models demonstrate that anatomical signatures generalize across animals and research laboratories, suggesting conserved computational rules for anatomical origin embedded in spike timing patterns.

Research Reagent Solutions for ISI Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Interspike Interval Analysis

| Tool/Technique | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density extracellular recording from hundreds of neurons simultaneously | Large-scale recordings in awake, behaving mice [1] |

| M-sequence Stimuli | Pseudorandom binary sequences for efficient receptive field mapping | Primate V1 receptive field characterization [16] |

| Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) | Statistical modeling of spike train dependencies | Connectivity inference from spike cross-correlations [18] |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence | Quantifying differences between ISI probability distributions | Measuring discriminability between stimulus statistics [15] |

| Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) | Decoding anatomical information from spike patterns | Predicting neuronal anatomical location [1] |

Signaling Pathways in ISI-Based Information Processing

The neural circuitry underlying ISI-based information processing involves specialized architectures for temporal pattern analysis. In the auditory system, neural timing nets and coincidence arrays analyze population-interval representations to extract perceptual qualities such as pitch [14]. These circuits process temporal correlations between spikes distributed across entire neural ensembles rather than local activations of specific neuronal subsets.

Within cortical and thalamic circuits, specific ISI patterns emerge from the interplay of synaptic properties, dendritic integration, and network dynamics. Synaptic mechanisms such as depression and facilitation can selectively increase or decrease the importance of particular spikes in shaping postsynaptic responses [16], creating biophysical machinery for real-time decoding of neuronal signals based on ISI duration. These mechanisms enable different classes of ISIs to convey distinct messages about visual stimuli, with spikes preceded by very short intervals (<3 msec) conveying information most efficiently and contributing disproportionately to overall receptive-field properties [16].

Interspike intervals serve as fundamental information carriers in the nervous system, conveying rich representations of sensory stimuli, anatomical location, and behavioral context through precise temporal patterning. The integration of quantitative ISI analysis with information theory and machine learning approaches continues to reveal new dimensions of the neural code, with broad implications for understanding neural computation, neurodevelopment, and information processing in health and disease.

Future research directions include elucidating the molecular and cellular mechanisms that establish and maintain anatomical signatures in spike trains, developing more efficient decoding algorithms for real-time analysis of large-scale neural recordings, and exploring the potential for targeted therapeutic interventions that modulate temporal coding patterns in neurological disorders.

Decoding Tools and Applications: From Machine Learning to Brain-Inspired SNNs

Supervised Machine Learning with Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs)

Supervised machine learning is a foundational paradigm in artificial intelligence where a model learns to map input data to known output labels using a labeled dataset [19] [20]. The core objective is to train a model that can generalize this learned relationship to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data [19]. This approach is broadly divided into classification tasks, which predict discrete categories (e.g., spam detection), and regression tasks, which predict continuous values (e.g., house prices) [19] [20]. The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a fundamental type of deep neural network that is highly versatile and can be applied to both types of supervised learning problems [21] [22]. An MLP consists of multiple layers of perceptrons, enabling it to learn complex, non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs, which makes it a powerful tool for modeling intricate data patterns [21].

Within the context of neural code research, supervised learning with MLPs provides a robust framework for decoding anatomical location from complex neural signals such as spike trains. The ability of MLPs to approximate any continuous function makes them particularly suited for identifying the underlying patterns in neuronal spiking dynamics that are correlated with specific network structures or functional roles [4]. This document will explore the technical foundations of MLPs, detail their application to neural data, and provide a scientific toolkit for researchers in neuroscience and drug development.

Core Components and Working Principles of MLPs

Architectural Components

An MLP is a fully connected, feedforward artificial neural network. Its architecture is structured into several sequential layers [21]:

- Input Layer: This layer serves as the entry point for the feature data. Each neuron in the input layer corresponds to one feature of the input sample. For instance, in an image recognition task, each neuron could represent the pixel intensity of a single pixel.

- Hidden Layers: These are the computational workhorses of the MLP, located between the input and output layers. An MLP can have one or more hidden layers. Each neuron in a hidden layer receives inputs from every neuron in the previous layer, performs a weighted sum, adds a bias, and applies a non-linear activation function. The presence of multiple hidden layers allows the network to learn hierarchical representations of the data.

- Output Layer: The final layer produces the network's prediction. The structure of this layer is determined by the task. For binary classification, it may have a single neuron using a sigmoid function, while for multi-class classification, it typically has multiple neurons (one per class) using a softmax function [21].

The Forward Propagation Process

Forward propagation is the process by which input data is transformed into an output prediction as it passes through the network. The operation of a single neuron can be summarized in two steps [21]:

- Weighted Sum: The neuron calculates a weighted sum of its inputs.

z = ∑(w_i * x_i) + bHere,x_irepresents an input,w_iis its associated weight, andbis the bias term. - Activation Function: The weighted sum

zis passed through a non-linear activation function, such as ReLU (f(z) = max(0, z)), Sigmoid (σ(z) = 1 / (1 + e^{-z})), or Tanh [21]. This non-linearity is crucial for allowing the network to learn complex patterns beyond simple linear relationships.

The Learning Process: Backpropagation and Optimization

Learning in an MLP involves iteratively adjusting the weights and biases to minimize the difference between the predicted output and the true label. This process is encapsulated by the loss function [21]. Common loss functions include Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression and Categorical Cross-Entropy for classification [21].

Backpropagation is the algorithm used to calculate the gradient of the loss function with respect to each weight and bias in the network. It works by applying the chain rule of calculus to propagate the error backward from the output layer to the input layer [21]. Once the gradients are computed, an optimization algorithm such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) or Adam is used to update the parameters. The Adam optimizer, which incorporates momentum and adaptive learning rates, is often preferred for its efficiency and stability [21] [22]. The update rule for a weight w with learning rate η is: w = w - η ⋅ (∂L/∂w) [21].

MLPs in Neural Code and Spike Train Research

Bridging Artificial and Biological Neural Networks

While MLPs are a cornerstone of traditional deep learning, research into Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) offers a more biologically realistic model of neural processing [22]. SNNs simulate the temporal dynamics of individual neurons, representing information through the timing of spikes. This makes them particularly relevant for research aimed at understanding how anatomical location and network topology influence neuronal function, as the spiking dynamics of individual neurons can reflect the structure and computational goals of the underlying network [4]. A key challenge in neuroscience is inferring the functional architecture of neuronal networks from limited observational data, such as the spiking activity of a subset of neurons. The spiking dynamics of individual neurons are not random; they are shaped by the network's connectivity and functional role, exhibiting non-stationary and multifractal characteristics [4].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Neural Network Models in Neuroscience Research

| Feature | Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | Spiking Neural Network (SNN) |

|---|---|---|

| Neuron Model | McCulloch-Pitts (static, rate-based) [22] | Hodgkin-Huxley, Izhikevich, Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (dynamic, spike-based) [4] [22] |

| Information Encoding | Real-valued numbers (activations) | Timing of discrete events (spike trains) [4] |

| Primary Strength | High accuracy, mature tools (e.g., TensorFlow), versatility [21] [22] | High energy efficiency, biological plausibility, temporal coding [22] |

| Relevance to Neural Code | Powerful decoder for classifying spike train patterns | Can model the actual generation and propagation of spike trains [4] |

| Typical Use Case | Classifying neuronal type based on spike rate features | Modeling how network structure influences emergent spiking dynamics [4] |

An Experimental Framework for Decoding Location from Spikes

The following workflow outlines a methodology for using MLPs to analyze spike train data in a research context.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for MLP analysis of spike trains.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Data Collection and Labeling (Ground Truth Establishment): Collect spike train data from neurons using techniques like multi-electrode arrays. The ground truth label, such as the anatomical location (e.g., cortical layer) or functional class of the neuron, must be confirmed through histology or functional calibration [4] [20]. This creates the essential labeled dataset for supervised learning.

Preprocessing and Feature Engineering: Convert raw spike trains into features suitable for an MLP.

- Temporal Binning: Divide the spike timeline into bins and count spikes in each bin to create a rate-based vector.

- Interspike Interval (ISI) Features: Calculate statistics from ISIs, such as mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation. Multifractal analysis of ISI time series can also be performed to characterize long-range memory and higher-order statistical behavior, which is sensitive to network structure [4].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like PCA can be applied to reduce the feature set to the most crucial components, preserving accuracy while increasing computational efficiency [20].

Model Training and Validation:

- Data Splitting: Split the labeled dataset into training (e.g., 80%), validation, and test sets [19].

- Model Configuration: Build an MLP model using a sequential structure. The input layer size matches the number of features, followed by hidden layers with activations like ReLU, and an output layer with softmax (for classification) or linear (for regression) activation [21].

- Compilation and Fitting: Compile the model with an optimizer (e.g., Adam) and a loss function (e.g., sparse categorical cross-entropy). Train the model on the training set, using the validation set to monitor for overfitting [21].

- Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation to assess the model's generalization performance more reliably [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

This section details key resources for implementing MLP-based research in neural coding.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Relevance to Spike Train Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow with Keras [21] | An open-source library for building and training deep learning models. Provides high-level APIs for defining MLP architectures. | The primary framework for implementing, training, and deploying MLP models for classification/regression of neural data. |

| Izhikevich Neuron Model [4] | A computationally efficient spiking neuron model capable of replicating the spiking and bursting behavior of cortical neurons. | Used in simulated spiking neural networks to generate synthetic spike train data for training and validating MLP decoders. |

| Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (MFDFA) [4] | A mathematical tool for characterizing the higher-order statistics and long-range memory of non-stationary, non-Markovian time series. | Extracts complex features from neuronal interspike intervals (ISIs) that are sensitive to the underlying network topology, providing powerful inputs for an MLP. |

| STM32 Microcontrollers / TinyML [22] | Low-power, low-cost microcontroller units (MCUs) enabling frugal AI and on-device inference. | Allows deployment of trained MLP models for real-time, low-power analysis of neural signals at the edge, crucial for implantable devices or portable labs. |

| Adam Optimizer [21] [22] | An extension of stochastic gradient descent that incorporates momentum and adaptive learning rates for faster, more stable convergence. | The optimizer of choice for training MLPs on complex spike train datasets, often requiring less hyperparameter tuning. |

Evaluation Metrics and Model Interpretation

Rigorous evaluation is critical to ensure the model's predictions are biologically meaningful. The choice of metric depends entirely on the supervised learning task.

Table 3: Evaluation Metrics for Supervised Learning Models

| Task | Metric | Formula and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN). Proportion of correct predictions. Can be misleading for imbalanced classes [23] [24]. |

| Precision | TP/(TP+FP). Measures the reliability of positive predictions [23] [24]. | |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP/(TP+FN). Measures the ability to capture all positive instances [23] [24]. | |

| F1-Score | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall). Harmonic mean of precision and recall, useful for imbalanced data [23] [24]. | |

| ROC-AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve. Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes across all thresholds. Closer to 1.0 is better [23] [24]. | |

| Regression | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | (1/N) * ∑⎮yj - ŷj⎮. Average absolute difference between predicted and actual values [23] [24]. |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | √[ (1/N) * ∑(yj - ŷj)² ]. Penalizes larger errors more heavily than MAE [23] [24]. | |

| R-squared (R²) | 1 - [∑(yj - ŷj)² / ∑(y_j - ȳ)²]. Proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables [24]. |

For a model predicting anatomical location from spike trains (a classification task), one would analyze a confusion matrix to see if certain locations are consistently confused, then drill down into precision and recall for each specific location. High performance on these metrics would provide strong evidence that the spiking patterns captured by the MLP are indeed informative of anatomical location.

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Bias-Variance Tradeoff and Regularization

A key challenge in training MLPs is the bias-variance tradeoff. A high-bias model (too simple) may underfit the training data, failing to capture relevant patterns in the spike trains. A high-variance model (too complex) may overfit, memorizing the training data, including its noise, and performing poorly on new data [23]. Techniques to prevent overfitting include L1/L2 regularization (which penalizes large weights in the loss function), Dropout (which randomly disables neurons during training to force robust learning), and using validation-based early stopping during training [21].

The Path Toward Bio-Plausible Learning

While MLPs are powerful, their training via backpropagation is not considered biologically plausible. The field of neuromorphic computing is exploring alternative approaches, such as Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) trained with bio-inspired rules like Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) [22]. SNNs offer the potential for drastically higher energy efficiency, making them suitable for low-power edge-AI applications in neuroprosthetics and portable diagnostic devices [22]. Future research may focus on hybrid models that use MLPs for offline analysis and decoding, while SNNs power the next generation of efficient, adaptive neural implants.

Diagram 2: Relationship between MLPs and Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs).

Spike Train Distance Metrics for Stimulus and Location Discrimination

The neural coding problem—how information is represented and processed by neurons via spike trains—is fundamental to neuroscience [25]. Traditional approaches have focused primarily on how spike trains encode external stimuli or internal behavioral states. However, emerging research reveals that neurons also embed robust signatures of their own anatomical location within their spike patterns [3]. This discovery introduces a new dimension to the neural code, suggesting that anatomical information is multiplexed with stimulus representation in spike train dynamics. The ability to discriminate both stimulus identity and anatomical origin from spike patterns relies heavily on sophisticated distance metrics and analytical frameworks that can quantify similarities and differences between neural firing patterns. These methodologies provide the essential toolkit for probing the relationship between brain structure and function, with significant implications for understanding neurodevelopment, multimodal integration, and the interpretation of large-scale neuronal recordings [3].

Core Spike Train Distance Metrics and Their Mathematical Foundations

Spike train distance metrics quantify the dissimilarity between temporal sequences of action potentials, enabling researchers to determine how neural responses vary under different experimental conditions. These methods form the computational foundation for discriminating both sensory stimuli and anatomical locations from neural activity patterns.

Table 1: Core Spike Train Distance Metrics and Their Properties

| Metric Name | Mathematical Basis | Sensitivity | Time Scale Dependence | Applicable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victor-Purpura Distance [26] [25] [27] | Cost-based transformation (spike insertion, deletion, movement) | Spike timing and rate | Parameter-dependent (time scale parameter q) | Single and multiple neurons |

| Van Rossum Distance [26] [27] | Euclidean distance between exponentially filtered spike trains | Spike timing and rate | Parameter-dependent (filter time constant τ) | Single and multiple neurons |

| ISI-Distance [27] | Normalized difference of instantaneous interspike intervals | Firing rate patterns | Time-scale independent | Multiple spike trains |

| SPIKE-Distance [27] | Weighted spike time differences relative to local firing rate | Spike timing with rate adaptation | Time-scale independent | Multiple spike trains |

| SPIKE-Synchronization [27] | Adaptive coincidence detection of quasi-simultaneous spikes | Synchronization and reliability | Time-scale independent | Multiple spike trains |

| Fisher-Rao Metric [28] | Extended Fisher-Rao distance between smoothed spike trains | Temporal patterns with phase invariance | Smoothing kernel dependent | Single neuron trials |

Time-Scale Dependent Metrics

The Victor-Purpura spike train metric operates on an elegant but computationally intensive principle: it quantifies the minimum cost required to transform one spike train into another through a sequence of elementary operations (spike insertion, deletion, or movement) [29] [25]. A crucial parameter 'q' determines the cost of moving a spike in time, thereby setting the temporal sensitivity of the metric. When q=0, the metric is sensitive only to spike count differences, while larger q values make it increasingly sensitive to precise spike timing. Similarly, the Van Rossum distance converts spike trains into continuous functions by convolving each spike with an exponential or Gaussian filter, then computes the Euclidean distance between the resulting functions [26] [27]. The time constant (τ) of the filter controls the temporal specificity, with smaller values emphasizing precise spike timing and larger values emphasizing firing rate differences.

Time-Scale Independent and Adaptive Metrics

A more recent class of time-scale independent metrics addresses the challenge of analyzing neural data without pre-specifying a relevant time scale. The ISI-Distance calculates a time-resolved dissimilarity profile based on instantaneous differences in interspike intervals, making it particularly sensitive to differences in firing rate patterns [27]. For two spike trains n and m, the instantaneous ISI-ratio is computed as I(t) = |xISI(n)(t) - xISI(m)(t)| / max{xISI(n)(t), xISI(m)(t)}, where xISI(n)(t) represents the current interspike interval for spike train n at time t [27].

The SPIKE-Distance builds upon this approach but adds sensitivity to spike timing by incorporating weighted differences between spike times [27]. It identifies for each time instant the four relevant "corner spikes" (the preceding and following spikes in each train) and computes their distances to the nearest spike in the other train. These values are then weighted by their proximity to the current time instant, resulting in a dissimilarity profile that uniquely combines sensitivity to spike timing with adaptability to local firing rate differences.

Anatomical Location Decoding from Spike Trains

Experimental Evidence for Anatomical Signatures

Groundbreaking research has demonstrated that machine learning models can successfully predict a neuron's anatomical location across multiple brain regions and structures based solely on its spiking activity [3]. Analyzing high-density Neuropixels recordings from thousands of neurons in awake, behaving mice, researchers have shown that anatomical location can be reliably decoded from neuronal activity across various stimulus conditions, including drifting gratings, naturalistic movies, and spontaneous activity. Crucially, these anatomical signatures generalize across animals and even across different research laboratories, suggesting a fundamental principle of neural organization [3].

This anatomical embedding operates at multiple spatial scales. At the large-scale level, the visual isocortex, hippocampus, midbrain, and thalamus can be distinguished. Within the hippocampus, structures including CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus show separable activity patterns, as do various thalamic nuclei [3]. Interestingly, within the visual isocortex, anatomical embedding is robust at the level of layers and primary versus secondary regions but does not robustly separate individual secondary structures [3].

Methodological Framework for Location Discrimination

The standard protocol for anatomical location decoding involves several key stages. First, high-density recordings are obtained using silicon probes (e.g., Neuropixels) from awake, behaving animals exposed to diverse stimuli and spontaneous activity conditions [3]. Well-isolated single units are filtered according to objective quality metrics (ISI violations, presence ratio, amplitude cutoff). Each neuron is assigned to specific anatomical structures based on established atlases.