Evaluating Motion Artifact Removal in fNIRS: A Comprehensive Guide to Metrics and Methodologies

This article provides a systematic framework for evaluating motion artifact (MA) correction techniques in functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).

Evaluating Motion Artifact Removal in fNIRS: A Comprehensive Guide to Metrics and Methodologies

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for evaluating motion artifact (MA) correction techniques in functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Aimed at researchers and professionals, it synthesizes current knowledge on MA characteristics, categorizes hardware and algorithmic removal strategies, and details key performance metrics for quantitative comparison. The content guides the selection of appropriate evaluation protocols, from foundational concepts to advanced validation, emphasizing robust and physiologically plausible assessment to enhance data quality in neuroscientific and clinical fNIRS applications.

Understanding Motion Artifacts: Origins, Types, and Impact on fNIRS Signal Quality

In functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), the accurate interpretation of neurovascular data is fundamentally challenged by motion artifacts—extraneous signals that corrupt the true hemodynamic response. These artifacts originate from two primary sources: physical optode decoupling, which causes direct measurement disruption, and motion-induced systemic physiological noise, which introduces biologically-based confounding signals [1]. Understanding this distinction is critical for selecting appropriate correction strategies, as methods effective for one artifact type may perform poorly for the other. This guide systematically compares motion artifact correction techniques, providing experimental data and protocols to inform method selection for research and clinical applications.

Classification and Mechanisms of Motion Artifacts

Motion artifacts in fNIRS signals manifest in distinct morphological patterns, each with characteristic origins and properties. The table below categorizes the primary artifact types and their underlying mechanisms.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Motion Artifacts in fNIRS

| Artifact Type | Primary Cause | Key Characteristics | Impact on Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spikes (Type A) | Sudden optode-skin decoupling from head jerks, speech | High amplitude, high frequency, short duration (≤1s) [2] | Sharp, transient signal deviation >50 SD from mean [2] |

| Peaks (Type B) | Sustained moderate movement | Moderate amplitude, medium duration (1-5s) [2] | Protracted deviation ~100 SD from mean [2] |

| Baseline Shifts | Slow optode displacement | Low frequency, long duration (5-30s) [2] | Signal drift ~300 SD from mean; slow recovery [2] |

| Low-Frequency Variations | Motion-induced systemic physiology (BP, HR changes) | Very slow oscillations (<0.1Hz) correlated with hemodynamic response [3] [4] | Mimics true hemodynamic response; task-synchronized [3] |

| Slow Baseline Shifts (Type D) | Major postural changes or prolonged decoupling | Very long duration (>30s), extreme amplitude [2] | Severe baseline disruption ~500 SD from mean [2] |

Anatomical and Regional Vulnerability

The susceptibility to motion artifacts varies significantly across scalp regions. Research combining computer vision with fNIRS has demonstrated that:

- The occipital and pre-occipital regions are particularly vulnerable to upward and downward head movements [5]

- Temporal regions show heightened sensitivity to lateral movements (bend left, bend right, left, and right movements) [5]

- Frontal regions are susceptible to artifacts from facial movements, including eyebrow raising and jaw motion during speech [3] [6]

This regional variability underscores the importance of considering both movement type and scalp location when designing experiments and implementing correction protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Motion Correction Techniques

Software-Based Correction Algorithms

Multiple algorithmic approaches have been developed to address motion artifacts in fNIRS data. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of predominant methods based on comparative studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Software-Based Motion Correction Techniques

| Correction Method | Underlying Principle | Best For Artifact Type | Efficacy (Real Cognitive Data) | Efficacy (Pediatric Data) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelet Filtering [3] | Multi-scale decomposition & thresholding | Spikes, baseline shifts [6] | 93% reduction in artifact area [3] | Superior outcomes [2] | Computationally intensive [7] |

| Moving Average [2] | Local smoothing | Spikes, gentle slopes | Not specifically reported | Superior outcomes [2] | May oversmooth valid signal |

| Spline Interpolation [3] [6] | Piecewise polynomial fitting | Spikes, baseline shifts [7] | Effective but less than wavelet [3] | Moderate outcomes [2] | Requires accurate artifact identification [7] |

| PCA-Based Methods [3] | Component separation & rejection | Global physiological noise [8] | Less effective for task-correlated artifacts [3] | Moderate outcomes [2] | Risk of cerebral signal removal |

| CBSI [3] | HbO/HbR anti-correlation | Low-frequency artifacts | Effective for specific artifact types [3] | Less effective [2] | Assumes specific HbO/HbR relationship |

| Kalman Filtering [3] | Recursive estimation | Slowly varying artifacts | Less effective than wavelet [3] | Not top performer [2] | Complex parameter tuning |

| tCCA-GLM [1] | Multimodal correlation | Systemic physiological noise | +45% correlation, -55% RMSE [1] | Not assessed | Requires multiple auxiliary signals |

Hardware-Based and Hybrid Approaches

Hardware-based solutions incorporate additional sensors to directly measure motion for subsequent regression:

- Accelerometer-Based Methods: Includes Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) and Accelerometer-Based Motion Artifact Removal (ABAMAR) [6]

- Short-Separation Channels: Placed ~8mm from sources to preferentially capture superficial signals for regression from standard channels [8] [1]

- Computer Vision Approaches: Using deep neural networks like SynergyNet to compute head orientation from video recordings [5]

Recent hybrid approaches combine multiple modalities. The BLISSA2RD framework integrates fNIRS with accelerometers and short-separation measurements using blind source separation, effectively addressing both direct optode decoupling and motion-induced physiological artifacts [1].

Emerging Learning-Based Techniques

Machine and deep learning methods represent the frontier of motion artifact correction:

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): U-net architectures demonstrate superior HRF reconstruction compared to wavelet and autoregressive methods [9]

- Denoising Autoencoders (DAE): Trained on synthetic data generated with autoregressive models, showing effective artifact removal on experimental data [9]

- Fully Connected Neural Networks: Simplified residual architectures (sResFCNN) combined with traditional filtering [9]

- Traditional Classifiers: SVM, KNN, and Linear Discriminant Analysis used to identify artifact-contaminated segments [9]

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Ground-Truth Movement Characterization

A rigorous protocol for validating motion correction techniques involves controlled head movements with simultaneous video recording:

- Participant Preparation: 15 participants (age 22.27±2.62 years) with whole-head fNIRS montage [5]

- Movement Protocol: Controlled head movements along three rotational axes (vertical, frontal, sagittal) at varying speeds (fast, slow) and types (half, full, repeated rotation) [5]

- Video Recording & Computer Vision: Frame-by-frame analysis using SynergyNet deep neural network to compute head orientation angles [5]

- Data Correlation: Maximal movement amplitude and speed extracted from orientation data correlated with spikes and baseline shifts in fNIRS signals [5]

- Data Availability: Dataset and analytical scripts available at: https://gitlab.com/a.bizzego/computer-vision-fnirs [5]

Semi-Simulated Data Validation

For evaluating correction performance with known ground truth:

- Resting-State Basis: Use real resting-state fNIRS data containing natural physiological noise [3]

- HRF Addition: Add simulated hemodynamic response functions to resting data at known time points [3]

- Performance Metrics: Calculate Mean-Squared Error (MSE) and Pearson's Correlation Coefficient between simulated and recovered HRF [3]

- Motion Contamination: Introduce real motion artifacts from purposefully moved participants or artificial artifact models [3]

Performance Evaluation Metrics

Standardized metrics enable objective comparison of correction efficacy:

- Signal Quality Metrics: ΔSignal-to-Noise Ratio (ΔSNR), Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) [9] [8]

- Time-Domain Accuracy: Correlation (Corr), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) with known HRF [1]

- Statistical Significance: F-Score, p-value of recovered HRF [1]

- Classification Impact: Vigilance detection accuracy with/without correction [9]

Signaling Pathways and Artifact Origins

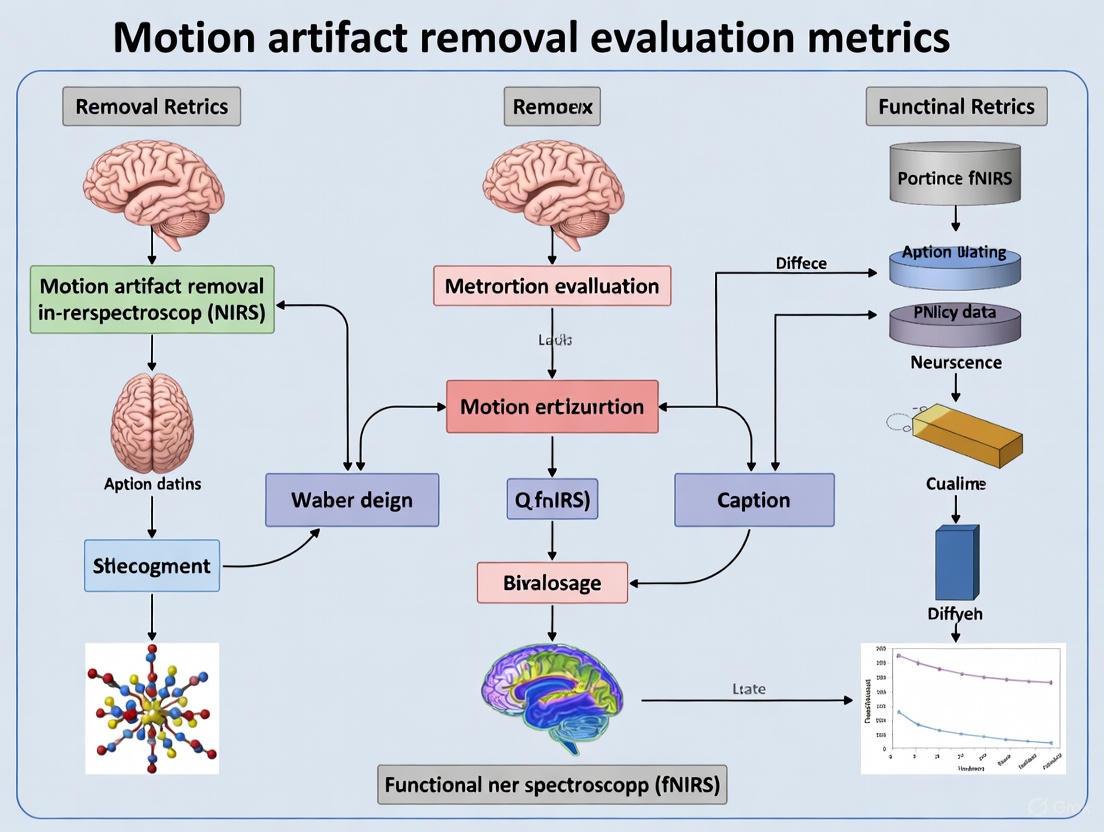

The diagram below illustrates the pathways through which motion generates artifacts in fNIRS signals, highlighting the distinction between direct optode decoupling and systemic physiological noise.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Motion Artifact Investigation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | Homer2/Homer3 [2] [7] | Comprehensive fNIRS processing with multiple MA correction algorithms |

| Analysis Toolboxes | fNIRSDAT (MATLAB-based) [2] | General Linear Model regression for individual and group-level analysis |

| Computer Vision Tools | SynergyNet deep neural network [5] | Frame-by-frame head orientation computation from video recordings |

| Auxiliary Sensors | Accelerometers, 3D motion capture, IMU [6] | Direct measurement of head motion for regression-based correction |

| Specialized Optodes | Short-separation channels (8-10mm) [8] [1] | Superficial signal regression to remove scalp contributions |

| Data Resources | Computer-vision fNIRS dataset [5] | Ground-truth movement data for algorithm validation |

| Performance Metrics | ΔSNR, CNR, F-Score, tCCA-GLM [9] [1] | Objective quantification of correction efficacy |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that motion artifact correction in fNIRS requires careful method selection based on artifact type, experimental population, and research objectives. Key recommendations emerge:

- For pediatric populations with high motion, moving average and wavelet methods yield superior outcomes [2]

- For task-correlated low-frequency artifacts, wavelet filtering demonstrates particular efficacy [3]

- When multiple artifact types are present, hybrid approaches combining spline interpolation with wavelet filtering may be optimal [7]

- For systemic physiological noise contamination, advanced regression techniques like tCCA-GLM with short-separation channels provide significant improvement [1]

- Emerging learning-based methods show promise for automated, data-driven correction but require further validation [9]

The field continues to evolve toward integrated solutions that address both direct optode decoupling and motion-induced physiological noise, with multimodal approaches leveraging auxiliary sensors and advanced computational methods showing particular promise for robust artifact correction in real-world research scenarios.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) has emerged as a preferred neuroimaging technique for studies requiring high ecological validity, allowing participants greater freedom of movement compared to traditional neuroimaging methods [5]. Despite its relative robustness against motion artifacts (MAs), fNIRS remains challenged by signal contamination from movement-induced disturbances that can compromise data integrity and interpretation [5] [10]. Effective management of these artifacts requires a fundamental understanding of their characteristic morphologies—categorized primarily as spikes, baseline shifts, and low-frequency oscillations [3]. Accurate characterization of these morphological subtypes provides the essential foundation for selecting appropriate correction algorithms and evaluating their efficacy, which is particularly crucial for advancing fNIRS applications in real-time neurofeedback and brain-computer interfaces [11].

The significance of motion artifact management extends across diverse fNIRS applications, from cognitive neuroscience and clinical neurology to motor rehabilitation and studies involving subject movements [9]. Artifacts induced by head movements, facial muscle activity, or jaw movements introduce noise that can obscure true hemodynamic responses, ultimately reducing the statistical power of studies and potentially leading to erroneous conclusions [3] [9]. This comparison guide systematically characterizes the primary motion artifact morphologies in fNIRS signals, provides experimental methodologies for their investigation, and evaluates the performance of leading correction approaches, with the broader aim of establishing a standardized framework for motion artifact removal evaluation metrics in fNIRS research.

Motion Artifact Morphologies: Characteristics and Origins

Motion artifacts in fNIRS signals manifest in distinct morphological patterns, each with unique characteristics and underlying physiological mechanisms. The classification into three primary categories—spikes, baseline shifts, and low-frequency variations—provides a framework for understanding artifact impact and selecting appropriate correction strategies [3].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Motion Artifact Morphologies

| Morphology Type | Frequency Content | Amplitude Profile | Primary Causes | Detection Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spikes | High-frequency | High-amplitude, transient | Sudden head movements, quick optode displacement [3] | Low (easily detectable) |

| Baseline Shifts | Moderate-frequency | Sustained signal level change | Sustained head positioning, pressure changes at optode-skin interface [12] | Moderate |

| Low-Frequency Variations | Low-frequency | Slow drifts | Jaw movements, facial expressions, talking/eating [3] [12] | High (resemble hemodynamic response) |

The regional susceptibility of fNIRS signals to motion artifacts varies significantly across the head. Recent research utilizing computer vision to characterize ground-truth movement information has demonstrated that repeated as well as upward and downward head movements particularly compromise fNIRS signal quality in the occipital and pre-occipital regions [5]. In contrast, temporal regions show greatest susceptibility to bend left, bend right, left, and right movements [5]. These findings underscore the importance of considering both movement type and scalp location when evaluating motion artifact morphologies in fNIRS studies.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Artifact Investigation

Controlled Movement Paradigms

Systematic investigation of motion artifact morphologies requires carefully designed experimental protocols that induce specific, controlled head movements. Bizzego et al. (2025) implemented a comprehensive approach where participants performed controlled head movements along three main rotational axes: vertical, frontal, and sagittal [5]. Movements were further categorized by speed (fast vs. slow) and type (half, full, or repeated rotation) to comprehensively characterize the association between specific movement parameters and resulting artifact morphologies [5].

Table 2: Experimental Movement Categorization for Motion Artifact Characterization

| Movement Axis | Movement Types | Speed Variations | Data Collection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical | Nodding (upward/downward) | Fast vs. slow | Computer vision (SynergyNet DNN) [5] |

| Frontal | Bend left, bend right | Fast vs. slow | Video recording with frame-by-frame analysis [5] |

| Sagittal | Left, right rotations | Fast vs. slow | Head orientation angle computation [5] |

| Combined | Half, full, repeated rotations | Varied | fNIRS signal correlation with movement metrics [5] |

Computer Vision Integration

A groundbreaking methodological advancement in motion artifact research involves the integration of computer vision techniques with fNIRS data collection. Experimental sessions are video recorded and analyzed frame-by-frame using deep neural networks such as SynergyNet to compute precise head orientation angles [5]. This approach enables researchers to extract maximal movement amplitude and speed from head orientation data while simultaneously identifying spikes and baseline shifts in the fNIRS signals [5]. The correlation of ground-truth movement data with artifact characteristics provides unprecedented insights into the specific movement parameters that generate different artifact morphologies.

Cognitive Task-Induced Artifacts

Beyond controlled movements, realistic cognitive tasks can induce motion artifacts that present particular challenges for identification and correction. Di Lorenzo et al. (2014) investigated artifacts caused by participants' jaw movements during vocal responses in a cognitive linguistic paradigm [3]. This approach revealed a particularly problematic artifact morphology characterized by low-frequency, low-amplitude disturbances that are temporally correlated with the evoked cerebral response [3]. Unlike easily identifiable spike artifacts, these task-correlated low-frequency variations closely resemble normal hemodynamic signals, making them exceptionally difficult to distinguish from true neural activity without sophisticated correction approaches.

Motion Artifact Correction Approaches: Performance Comparison

Multiple algorithmic approaches have been developed to address the challenge of motion artifacts in fNIRS data, with varying efficacy across different artifact morphologies.

Traditional Correction Methods

Traditional motion correction techniques include both hardware-based and algorithmic solutions. Hardware-based approaches often utilize accelerometers, with methods such as accelerometer-based motion artifact removal (ABAMAR) and active noise cancellation (ANC) showing promise for real-time applications [6]. Algorithm-based solutions include spline interpolation, wavelet filtering, principal component analysis (PCA), Kalman filtering, and correlation-based signal improvement (CBSI) [3].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Motion Artifact Correction Techniques

| Correction Method | Best For Artifact Type | Advantages | Limitations | Recovery Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelet Filtering | Spikes, baseline shifts [3] | No pre-identification needed, powerful for high-frequency noise [12] | Computationally expensive, modifies entire time series [12] | 93% artifact reduction in cognitive tasks [3] |

| Spline Interpolation | Spikes, identifiable artifacts [12] | Corrects only contaminated segments, simple and fast [12] | Requires reliable artifact identification, leaves high-frequency noise [12] | Dependent on accurate motion detection [12] |

| Spline + Wavelet Combined | Mixed artifact types [13] | Comprehensive approach for complex artifact profiles | Computational intensity | Best overall performance in infant data, saves nearly all corrupted trials [13] |

| tPCA | Spikes with clear identification [12] | Effective for targeted removal | Performance relies on optimal identification [12] | Varies with motion contamination degree [12] |

| CBSI | Low-frequency variations [3] | Correlation-based approach | May not address spike artifacts | Moderate performance on task-correlated artifacts [3] |

Emerging Learning-Based Approaches

Recent advances in motion artifact correction have incorporated machine learning and deep learning methodologies. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) based on U-net architectures have demonstrated promising results in reconstructing hemodynamic responses while reducing motion artifacts, producing lower mean squared error (MSE) and variance in HRF estimates compared to traditional methods [9]. Denoising auto-encoder (DAE) models, trained on synthetic fNIRS datasets generated through auto-regressive models, have also shown effectiveness in eliminating motion artifacts while preserving signal integrity [9]. These learning-based approaches represent the next frontier in motion artifact management, potentially offering more adaptive and comprehensive correction across diverse artifact morphologies.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for fNIRS Motion Artifact Research

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Motion Artifact Investigation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Motion Artifact Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition & Analysis Platforms | Homer2/Homer3 [12] | Standardized fNIRS data processing with multiple built-in motion correction algorithms |

| Computer Vision Tools | SynergyNet Deep Neural Network [5] | Frame-by-frame video analysis for ground-truth head movement quantification |

| Motion Detection Sensors | Accelerometers [6], 3D motion capture systems [10] | Supplementary movement data collection for artifact identification and correction |

| Algorithmic Toolboxes | Wavelet Filtering工具箱 [3], Spline Interpolation tools [12] | Implementation of specific correction techniques for different artifact morphologies |

| Performance Evaluation Metrics | ΔSignal-to-Noise Ratio (ΔSNR) [9], Mean Squared Error (MSE) [9] | Quantitative assessment of motion correction efficacy |

| Experimental Paradigms | Controlled head movement protocols [5], Cognitive tasks with vocalization [3] | Systematic artifact induction for methodology validation |

The systematic characterization of motion artifact morphologies—spikes, baseline shifts, and low-frequency oscillations—provides an essential foundation for advancing fNIRS signal processing and analysis. Through controlled experimental protocols and emerging computer vision techniques, researchers can now precisely correlate specific movement parameters with resultant artifact profiles, enabling more targeted correction approaches. Performance comparisons of correction algorithms reveal that while traditional methods like wavelet filtering and spline interpolation remain effective for many artifact types, combined approaches and emerging learning-based methods show particular promise for complex artifact profiles. As fNIRS continues to expand into real-time applications and challenging populations, comprehensive understanding of motion artifact morphologies and their correction will remain crucial for ensuring data integrity and advancing neuroimaging research.

The Physiological and Non-Physiological Origins of Motion Artifacts in fNIRS

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) has emerged as a pivotal neuroimaging technique due to its non-invasive nature, portability, and relatively high tolerance to participant movement. However, this tolerance is paradoxically paired with a significant vulnerability: motion artifacts (MAs) that can severely compromise data quality. These artifacts represent a complex interplay between physiological processes and non-physiological physical disturbances. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these origins is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental prerequisite for selecting appropriate correction algorithms and ensuring the validity of experimental outcomes. This guide systematically compares the performance of prevalent MA correction techniques, providing a structured framework for their evaluation within the broader context of fNIRS methodology.

The Dual Nature of Motion Artifacts

Motion artifacts in fNIRS signals originate from two primary domains: non-physiological physical displacements and physiological processes that are unrelated to neural activity. Disentangling these origins is critical for developing and applying effective correction strategies.

Non-Physiological Origins

The predominant source of MAs is the physical decoupling of optodes from the scalp. Any movement that changes the orientation or distance between the optical fibers and the scalp can alter the impedance, generating noise in the measured signal [6] [14]. The manifestations of these physical disturbances are diverse and can be categorized as follows:

- Spikes: Rapid, high-amplitude deflections occur when optodes move quickly and return to their original position [14].

- Baseline Shifts: Irrevocable changes in the baseline signal intensity happen when the optode settles into a new, stable position on the scalp after movement [3] [15].

- Slow Drifts: Gradual signal changes result from slow, continuous optode movement [14].

The specific head movements leading to these artifacts have been characterized using computer vision techniques, which identify movements along rotational axes—vertical, frontal, and sagittal—as primary culprits. Notably, repeated movements, as well as upward and downward motions, particularly compromise signal quality [5].

Physiological Origins

Beyond physical displacement, fNIRS signals are contaminated by physiological noise originating from systemic physiology in the scalp. These non-neural cerebral and extracerebral signals constitute a significant challenge, particularly in resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) analyses [16]. The key physiological confounds include:

- Cardiac Activity: Pulsatile blood flow creates oscillations typically around 1 to 1.2 Hz [16].

- Respiratory Cycles: Breathing patterns introduce lower frequency noise in the 0.3 to 0.6 Hz range [16].

- Blood Pressure Oscillations: Mayer waves, occurring at approximately 0.1 Hz, represent another source of low-frequency physiological noise [16].

This physiological noise induces temporal autocorrelation and increases spatial covariance between channels across the brain, violating the statistical assumptions of many connectivity models and potentially leading to spurious correlations [16].

The following diagram illustrates the pathways through which various sources lead to motion artifacts in the fNIRS signal.

Motion Artifact Correction Techniques: A Comparative Analysis

Multiple algorithmic approaches have been developed to correct for motion artifacts, each with distinct underlying principles, advantages, and limitations. The following table provides a structured comparison of the most prevalent techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Motion Artifact Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Ideal Artifact Type | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelet Filtering [17] [14] | Decomposes signal using wavelet basis, zeros artifact-related coefficients, then reconstructs. | Spikes, slow drifts [14]. | No MA detection needed; fully automatable; preserves signal integrity [14]. | Performance depends on wavelet basis choice. |

| Spline Interpolation (MARA) [6] [15] | Identifies artifact segments, fits cubic splines to these intervals, and subtracts them. | High-amplitude spikes, baseline shifts [15]. | Significant MSE reduction [15]. | Requires accurate MA detection; multiple user-defined parameters [14]. |

| Correlation-Based Signal Improvement (CBSI) [3] [14] | Assumes HbO and HbR are negatively correlated during neural activity but positively during MAs. | Large spikes, baseline shifts [14]. | Fully automatable; no MA detection needed [14]. | Relies on strong negative correlation assumption; may not hold in pathologies [14]. |

| Targeted PCA (tPCA) [14] [18] | Applies PCA only to pre-detected motion artifact segments to avoid over-correction. | Artifacts identifiable via amplitude/SD thresholds. | Reduces over-correction risk vs. standard PCA [14]. | Complex to use; performance depends on many parameters [14]. |

| Temporal Derivative Distribution Repair (TDDR) [18] | Utilizes the statistical properties of the signal's temporal derivative to identify and correct outliers. | Not specified in reviewed literature. | Superior denoising for brain network analysis [18]. | Not as widely validated as other methods. |

| WCBSI (Combined Method) [14] | Integrates wavelet filtering and CBSI into a sequential correction pipeline. | Mixed and severe artifacts [14]. | Superior performance across multiple metrics; handles diverse artifacts [14]. | Increased computational complexity. |

Performance Evaluation in Experimental Studies

The theoretical strengths and limitations of these algorithms are validated through rigorous experimental testing. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from comparative studies, providing a basis for objective performance assessment.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Correction Algorithms in Experimental Studies

| Study & Population | Task | Top Performing Algorithms | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brigadoi et al. (2014) [17]Adults (Cognitive) | Color-naming task with vocalization | Wavelet Filtering | Reduced artifact area under the curve in 93% of cases. |

| Cooper et al. (2012) [15]Adults (Resting-state) | Resting-state | Spline InterpolationWavelet Analysis | 55% avg. MSE reduction (Spline).39% avg. CNR increase (Wavelet). |

| Ayaz et al. (2021) [2]Children (Language task) | Grammatical judgment task | Moving AverageWavelet | Best outcomes across five predefined metrics. |

| Guan & Li (2024) [18]Simulated & Real FC data) | Brain network analysis | TDDRWavelet Filtering | Superior ROC results; best recovery of original FC and topological patterns. |

| Ernst et al. (2023) [14]Adults (Motor task with induced MAs) | Hand-tapping with head movements | WCBSI (Combined Method) | Exceeded average performance (p < 0.001); 78.8% probability of being best-ranked. |

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Validation

The evaluation of motion correction techniques relies on sophisticated experimental designs that enable comparison against a "ground truth" hemodynamic response. The following methodologies represent best practices in the field.

The Induced-Motion Paradigm

Ernst et al. (2023) established a robust protocol for directly comparing MA correction accuracy [14]:

- Participants: 20 healthy adults.

- Task Design: Participants performed a simple hand-tapping task under three conditions:

- Tapping Only: Provided the "ground truth" hemodynamic response without motion artifacts.

- Tapping with Mild Head Movement: Induced subtle motion artifacts.

- Tapping with Severe Head Movement: Induced pronounced motion artifacts.

- Motion Tracking: Head movements were quantitatively monitored using accelerometers.

- Data Analysis: Corrected signals from conditions 2 and 3 were compared against the "ground truth" from condition 1 using four quantitative metrics: Pearson's correlation coefficient (R), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and change in area under the curve (ΔAUC).

Real Cognitive Data with Task-Correlated Artifacts

Brigadoi et al. (2014) utilized a cognitive paradigm that naturally produced motion artifacts correlated with the hemodynamic response [17] [3]:

- Participants: 18 adult students.

- Task: A color-naming Stroop task requiring vocal responses, which produced jaw movements that generated low-frequency, low-amplitude motion artifacts temporally correlated with the expected hemodynamic response.

- Evaluation: Since the true HRF was unknown, performance was assessed using physiological plausibility metrics of the recovered HRF, including its shape, timing, and the negative correlation between HbO and HbR.

Pediatric Language Task Protocol

A study by Ayaz et al. (2021) focused on the critical challenge of motion correction in pediatric populations [2]:

- Participants: 12 children (ages 6.8-12.6 years).

- Task: An auditory grammatical judgment language task presented using a rapid event-related design.

- Artifact Classification: MAs were categorized into four types (A-D) based on duration and amplitude, from brief spikes (Type A) to slow baseline shifts (Type D).

- Analysis: Efficacy of six correction methods was evaluated using five predefined metrics tailored to pediatric data characteristics.

The workflow for developing and validating motion artifact correction methods typically follows a systematic process, as illustrated below.

Successful fNIRS research requiring motion artifact correction depends on both hardware and software components. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the experimental pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for fNIRS Motion Artifact Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Software Toolboxes | HOMER2, HOMER3 [2] [14] | Provides standardized implementations of major MA correction algorithms (PCA, spline, wavelet, CBSI, etc.) for reproducible analysis. |

| Auxiliary Motion Sensors | Accelerometers, IMUs, Gyroscopes [6] [14] | Offers objective, continuous measurement of head movement dynamics for MA identification and validation of correction methods. |

| Computer Vision Systems | SynergyNet Deep Neural Network [5] | Enables markerless tracking of head orientation and movement through video analysis, providing ground truth movement data. |

| Short-Separation Channels | fNIRS detectors at <1 cm distance [16] | Measures systemic physiological noise from superficial layers, used as a regressor in advanced correction pipelines. |

| Standardized Test Paradigms | Hand-tapping, Grammatical Judgment, Resting-State [17] [2] [14] | Provides reproducible experimental contexts for generating comparable hemodynamic responses and motion artifacts across studies. |

The journey to mitigate motion artifacts in fNIRS is fundamentally about understanding their dual origins—both physiological and non-physiological. The evidence from comparative studies consistently indicates that while multiple correction algorithms exist, wavelet-based methods and their hybrids (like WCBSI) demonstrate superior and reliable performance across diverse experimental conditions and populations [17] [14] [18]. For brain functional connectivity analyses, TDDR also emerges as a particularly powerful option [18]. The selection of an appropriate algorithm must be guided by the specific artifact characteristics, the participant population, and the analytical goals of the study. As fNIRS continues to expand into more real-world applications, the development and rigorous validation of motion correction techniques will remain essential for ensuring the reliability and interpretability of fNIRS-derived biomarkers in both basic research and clinical drug development.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) has emerged as a preferred neuroimaging technique for studies requiring high ecological validity, allowing participants greater freedom of movement compared to traditional neuroimaging methods [5]. Despite this advantage, fNIRS signals are notoriously susceptible to motion artifacts (MAs)—unexpected changes in recorded signals caused by subject movement that severely degrade signal fidelity [19]. These artifacts represent a fundamental challenge for researchers and drug development professionals who require precise hemodynamic measurements for interpreting neural activity, assessing cognitive states, or evaluating pharmaceutical effects on brain function. Motion artifacts can introduce spurious components that mimic neural activity (creating false positives) or obscure actual neural activations (leading to false negatives), both of which compromise the reliability of neuroscientific findings and drug efficacy evaluations [19]. The significant deterioration in measurement quality caused by motion artifacts has become an essential research topic for fNIRS applications, particularly as the technology moves toward more portable and wearable devices used in real-world settings [10] [6].

Motion Artifact Origins and Characteristics

Motion artifacts in fNIRS signals originate from diverse physiological movements that disrupt the optimal coupling between optical sensors (optodes) and the scalp. The primary mechanism involves imperfect contact between optodes and the scalp, manifesting as displacement, non-orthogonal contact, and oscillation of the optodes [10] [6]. Research has systematically categorized movement sources based on their physiological origins:

Head movements: Including nodding, shaking, tilting, and rotational movements along three main axes (vertical, frontal, sagittal) introduce distinct artifact patterns [5] [10]. Recent research using computer vision to characterize motion artifacts has revealed that repeated movements as well as upward and downward movements particularly compromise fNIRS signal quality [5].

Facial muscle movements: Actions including raising eyebrows, frowning, and other facial expressions create localized artifacts, especially in frontal lobe measurements [10] [6].

Jaw movements: Talking, eating, and drinking produce two different types of motion artifacts that correlate with temporalis muscle activity and can be particularly challenging as they often coincide with cognitive tasks [10] [3].

Body movements: Movements of upper and lower limbs degrade fNIRS signals either by causing secondary head movements or through the inertia of the fNIRS device itself [10] [6]. This is especially problematic in mobile paradigms such as gait studies or rehabilitation exercises.

Types and Temporal Properties of Motion Artifacts

Motion artifacts manifest in fNIRS signals with distinct temporal characteristics that determine their impact on signal quality and the appropriate correction strategies:

High-frequency spikes: Sudden, brief disruptions appearing as sharp peaks in the fNIRS signal, typically resulting from rapid head movements or impacts [9] [3]. These are often easily detectable but can saturate signal processing systems.

Baseline shifts: Sustained deviations from the baseline signal caused by slow head rotations or changes in optode positioning that alter the coupling between optodes and scalp [3] [20]. These are particularly problematic as they can mimic low-frequency hemodynamic responses.

Low-frequency variations: Slower oscillations that blend with physiological signals, making them particularly challenging to distinguish from genuine hemodynamic responses [3]. These often occur during sustained movements or postural adjustments.

Table 1: Classification of Motion Artifact Types in fNIRS Signals

| Artifact Type | Temporal Characteristics | Common Causes | Detection Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Frequency Spikes | Short duration (0.5-2s), high amplitude | Rapid head shaking, sudden movements | Low (easily distinguishable) |

| Baseline Shifts | Sustained deviation, slow return to baseline | Head repositioning, slow rotation | Moderate |

| Low-Frequency Variations | Slow oscillations (>5s duration) | Sustained movements, postural changes | High (mimics hemodynamic response) |

Quantitative Impact of Motion Artifacts on SNR

Direct Effects on Signal Quality Metrics

The degradation of Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) due to motion artifacts has been quantitatively established through multiple controlled studies. Motion artifacts reduce the SNR of fNIRS signals by introducing high-amplitude noise components that overwhelm the true hemodynamic signal of interest [10] [6]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that the amplitude of motion artifacts can exceed the true hemodynamic response by an order of magnitude, drastically reducing the detectability of neural activation patterns [3] [21]. In cognitive experiments, the presence of motion artifacts has been shown to ameliorate classification accuracy, directly impacting the reliability of brain-computer interface applications and cognitive state classification [10]. Research on vigilance level detection during walking versus seated conditions revealed that motion artifacts significantly reduced detection accuracy, underscoring the critical importance of effective artifact management for mobile paradigms [9].

Regional Vulnerability to Motion Artifacts

The impact of motion artifacts on SNR is not uniform across the cortex. Different brain regions show variable susceptibility to motion artifacts based on their anatomical location and the types of movements most likely to affect them. Computer vision studies combining ground-truth movement data with fNIRS signals have revealed that:

- The occipital and pre-occipital regions are particularly susceptible to motion artifacts following upward or downward head movements [5].

- Temporal regions are most affected by lateral movements (bend left, bend right, left, and right movements) [5].

- Frontal regions show vulnerability to facial movements and jaw motions, creating particular challenges for studies of higher cognition and emotional processing [3].

This regional variability necessitates customized artifact correction approaches based on the brain region being studied and the experimental paradigm.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Motion Artifacts on fNIRS Signal Quality

| Impact Metric | Without MAs | With MAs | Degradation | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Accuracy | 70-85% | 45-60% | 25-40% reduction | Vigilance detection during walking [9] |

| Contrast-to-Noise Ratio | 100% (baseline) | 40-60% | 40-60% reduction | Cognitive task with speech [3] |

| HRF Amplitude Estimation | Accurate | Overestimated by 2-3x | 200-300% error | Simulated data with added MAs [21] |

| Functional Connectivity | Stable patterns | Altered correlation | False positive/negative connections | Resting-state networks [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Motion Artifact Impact

Controlled Movement Paradigms

To systematically quantify the impact of motion artifacts on SNR, researchers have developed controlled experimental protocols that induce specific, reproducible movements:

Standardized head movements: Participants perform controlled head movements along three rotational axes (pitch, yaw, roll) at varying speeds (slow, fast) and movement types (half, full, repeated rotations) while fNIRS data is collected [5]. These movements are typically guided by visual cues to ensure consistency across participants.

Task-embedded movements: Incorporating movements naturally occurring during cognitive tasks, such as jaw movements during speech in color-naming tasks [3]. This approach captures artifacts that are temporally correlated with the hemodynamic response, representing a particularly challenging scenario for correction algorithms.

Whole-body movements: Having participants perform walking, reaching, or other gross motor activities while wearing fNIRS systems, especially relevant for rehabilitation research and mobile brain imaging [9].

Signal Quality Assessment Methodologies

The quantitative evaluation of motion artifact impact employs several well-established methodological approaches:

Semi-simulated data: Adding simulated hemodynamic responses to real resting-state fNIRS data containing actual motion artifacts, creating a ground truth for evaluating artifact impact and correction efficacy [3] [21]. This approach allows precise calculation of metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Pearson's Correlation Coefficient between known and recovered signals.

Computer vision integration: Using video recordings analyzed frame-by-frame with deep neural networks (e.g., SynergyNet) to compute head orientation angles, providing objective ground-truth movement data synchronized with fNIRS acquisition [5]. This enables precise correlation between specific movement parameters (amplitude, speed) and artifact characteristics.

Artefact induction and recovery: Purposely asking participants to perform specific movements during designated periods to create motion artifacts, then evaluating how these artifacts impact the recovery of known functional responses [3].

Experimental Setup and Hardware Solutions

Computer Vision Systems: Video recording equipment with deep neural network analysis (e.g., SynergyNet) for extracting ground-truth head movement parameters including orientation angles, movement amplitude, and velocity [5]. These systems provide objective movement quantification without physical contact with participants.

Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs): Wearable accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers that provide complementary motion data for adaptive filtering approaches such as Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) and Accelerometer-Based Motion Artifact Removal (ABAMAR) [10] [6]. These are particularly valuable for capturing high-frequency movement data.

Collodion-Fixed Optical Fibers: Specialized optode-scalp coupling methods using prism-based optical fibers fixed with collodion to improve adhesion and reduce motion-induced decoupling [10] [6]. This hardware solution addresses the root cause of motion artifacts but requires more expertise to implement.

Polarization-Based Systems: fNIRS systems using linearly polarized light sources with orthogonally polarized analyzers to distinguish between motion artifacts and true hemodynamic signals based on their polarization properties [10].

Software and Analytical Tools

Wavelet Analysis Toolboxes: Software implementations of wavelet filtering algorithms that effectively isolate motion artifacts in the wavelet domain by identifying and thresholding outlier coefficients [3] [19]. These are particularly effective for spike artifacts and low-frequency oscillations.

Spline Interpolation Algorithms: Tools for motion artifact reduction (e.g., MARA) that identify corrupted segments and reconstruct them using spline interpolation, especially effective for baseline shifts [19] [20].

Hybrid Correction Frameworks: Combined approaches that integrate multiple correction strategies (e.g., spline interpolation for severe artifacts, wavelet methods for slight oscillations) to address different artifact types within a unified processing pipeline [20].

Deep Learning Architectures: Denoising Autoencoder (DAE) models and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) specifically designed for motion artifact removal, offering assumption-free correction without extensive parameter tuning [9] [21].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Artifact Management

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Solutions | Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Capture independent movement data for adaptive filtering | Medium |

| Computer Vision Systems | Provide ground-truth movement metrics without physical contact | High | |

| Collodion-Fixed Fibers | Improve optode-scalp coupling to prevent artifacts | High | |

| Algorithmic Solutions | Wavelet Filtering | Remove spike artifacts and oscillations in time-frequency domain | Low-Medium |

| Spline Interpolation | Correct baseline shifts and severe artifacts | Medium | |

| Temporal Derivative Distribution Repair (TDDR) | Online artifact removal using robust statistical estimation | Low | |

| Evaluation Metrics | ΔSNR (Change in SNR) | Quantify noise suppression after correction | Low |

| Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) | Evaluate functional contrast preservation | Low | |

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Assess fidelity of recovered hemodynamic response | Low |

Implications for Motion Artifact Correction Algorithm Development

The systematic quantification of motion artifact impact on SNR provides critical guidance for developing and validating correction algorithms. Research demonstrates that correction is always preferable to rejection; even simple artifact correction methods outperform the practice of discarding contaminated trials, which reduces statistical power and introduces selection bias [3]. However, the efficacy of correction algorithms varies significantly based on artifact characteristics:

Wavelet-based methods have shown particular effectiveness, reducing the area under the curve where artifacts are present in 93% of cases for certain artifact types [3]. More recent evaluations identify Temporal Derivative Distribution Repair (TDDR) and wavelet filtering as the most effective methods for functional connectivity analysis [19].

Hybrid approaches that combine multiple correction strategies (e.g., spline interpolation for baseline shifts with wavelet methods for oscillations) demonstrate superior performance compared to individual methods alone, addressing the diverse nature of motion artifacts [20].

Deep learning methods represent a promising emerging approach, with Denoising Autoencoder (DAE) architectures demonstrating competitive performance while minimizing the need for expert parameter tuning [9] [21].

The development of standardized evaluation metrics incorporating both noise suppression (ΔSNR, artifact power attenuation) and signal distortion (percent root difference, correlation coefficients) is essential for objective comparison of correction methods across different research contexts [10] [9]. This quantitative framework enables researchers to select the most appropriate artifact management strategy based on their specific experimental paradigm, participant population, and research objectives.

In functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) research, motion artifacts (MAs) represent a significant source of signal contamination that can severely compromise data integrity and lead to spurious scientific conclusions [6] [3]. These artifacts arise from imperfect contact between optodes and the scalp during participant movement, resulting in signal components that can mimic or obscure genuine hemodynamic responses [6] [5]. The evaluation of motion artifact removal techniques consequently hinges on two competing objectives: effectively suppressing noise while faithfully preserving the underlying physiological signal of interest [6] [3]. This fundamental trade-off between noise suppression and signal preservation forms the critical framework for assessing methodological performance in fNIRS research, particularly in drug development studies where accurate hemodynamic measurement is paramount.

Motion artifacts manifest in diverse forms, including high-frequency spikes, baseline shifts, and low-frequency variations, each presenting distinct challenges for correction algorithms [3] [22]. These artifacts can be temporally correlated with the hemodynamic response function (HRF), making simple filtering approaches insufficient [3]. The pursuit of optimal motion correction therefore requires sophisticated evaluation metrics that quantitatively assess both noise reduction and signal integrity across varied experimental conditions.

Core Evaluation Metrics Framework

The assessment of motion artifact correction techniques employs distinct metric categories targeting noise suppression and signal preservation objectives. The following table summarizes the key evaluation metrics employed in fNIRS research:

Table 1: Core Evaluation Metrics for Motion Artifact Correction Techniques

| Evaluation Goal | Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noise Suppression | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Ratio of signal power to noise power | Higher values indicate better noise suppression |

| Pearson's Correlation Coefficient (R) | Linear correlation between corrected signals and reference | Values closer to 1 indicate better noise removal | |

| Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) | Ratio of hemodynamic response amplitude to background noise | Higher values indicate improved functional sensitivity | |

| Within-Subject Standard Deviation | Variability of repeated measurements in the same subject | Lower values indicate better reliability | |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) of ROC | Ability to distinguish true activations from false positives | Higher values indicate better detection specificity | |

| Signal Preservation | Mean-Squared Error (MSE) | Average squared difference between estimated and true HRF | Lower values indicate better preservation of signal shape |

| Pearson's Correlation with True HRF | Linear relationship between recovered and simulated HRF | Values closer to 1 indicate faithful signal reconstruction |

These metrics enable researchers to quantitatively compare the performance of different correction techniques and select the most appropriate method for their specific research context [6] [3]. The noise suppression metrics primarily evaluate the effectiveness of artifact removal, while the signal preservation metrics assess how faithfully the underlying hemodynamic response is maintained after processing [6].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Semisynthetic Simulation with Experimental Data

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) simulation approach provides a robust framework for evaluating metric performance under controlled conditions [23]:

Background Signal Acquisition: Collect real fNIRS data during resting state or breath-hold tasks to capture authentic physiological noise characteristics [23]

Synthetic HRF Addition: Add known, simulated "brain" responses at varying amplitudes to the background signals, creating a ground truth for validation [23] [3]

Algorithm Application: Apply multiple motion correction techniques to the semisynthetic data

Performance Quantification: Calculate sensitivity and specificity by comparing detected activations with known added responses [23]

ROC Curve Generation: Plot true positive rates against false positive rates across varying detection thresholds

AUC Calculation: Compute the area under the ROC curve as a comprehensive performance metric [23]

This methodology enables direct comparison of correction techniques with perfect knowledge of the true hemodynamic response, allowing precise quantification of both noise suppression and signal preservation capabilities [23] [3].

Real Functional Data with Physiological Plausibility Assessment

When the true HRF is unknown, as with real task data, researchers employ physiologically plausible HRF parameters for validation [3]:

Data Collection: Acquire fNIRS data during cognitive or motor tasks known to produce specific artifacts (e.g., speaking tasks that generate jaw movement artifacts) [3]

Motion Correction: Apply multiple artifact removal algorithms to the contaminated data

HRF Parameter Extraction: Derive key parameters from the recovered hemodynamic response, including time-to-peak, response amplitude, and full-width at half-maximum [3]

Plausibility Assessment: Evaluate whether the extracted parameters fall within physiologically reasonable ranges established by prior literature

Spatial Specificity Evaluation: Assess whether activation patterns conform to neuroanatomical expectations [24]

This approach provides practical validation of correction techniques under real-world conditions where motion artifacts may be correlated with the task paradigm itself [3].

Performance Comparison of Correction Techniques

Empirical comparisons of motion artifact correction methods reveal performance variations across different evaluation metrics. The following table synthesizes findings from multiple experimental studies:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Motion Artifact Correction Techniques

| Correction Method | Noise Suppression Performance | Signal Preservation Performance | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelet Filtering | Highest performance for spike and low-frequency artifacts [3] | Preserves HRF shape effectively (93% artifact reduction) [3] | General purpose, various artifact types |

| Spline Interpolation | Effective for baseline shifts [22] | Best improvement in Mean-Squared Error [3] | Slow head movements causing baseline shifts |

| Moving Average | Good overall noise reduction [2] | Moderate signal preservation | Pediatric populations [2] |

| tPCA | Effective for specific artifact segments [25] | Good HRF recovery for motion spikes | Isolated motion artifacts in children [2] |

| CBSI | Removes large spikes effectively [22] | Assumes perfect negative HbO/HbR correlation | Scenarios with strong anti-correlation |

| Short-Separation Channels + GLM | Superior noise suppression (best AUC in ROC) [23] | Maintains physiological accuracy | When hardware supports short-separation measurements |

| Hybrid Methods | Combined strengths of multiple approaches [22] | Balanced performance across metrics | Complex artifacts with different characteristics |

The comparative evidence indicates that wavelet-based methods generally provide the most effective balance between noise suppression and signal preservation for typical artifact types [3]. However, method performance is context-dependent, with certain techniques excelling in specific scenarios, such as spline interpolation for baseline shifts or moving average approaches for pediatric data [22] [2].

Research Reagent Solutions: Experimental Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for fNIRS Motion Artifact Investigation

| Research Tool | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Separation Channels | Measures superficial layer contamination | 0.5-1.0 cm source-detector distance; requires specialized hardware [23] [24] |

| Accelerometers/IMU | Provides independent motion measurement | Synchronization with fNIRS data crucial; placement on head optimal [6] |

| Computer Vision Systems | Quantifies head movement without physical contact | Deep neural networks (e.g., SynergyNet) for head orientation [5] |

| Auxiliary Physiological Monitors | Records cardiac, respiratory, blood pressure signals | Helps distinguish motion artifacts from physiological noise [8] |

| Semisynthetic Data Algorithms | Generates validation datasets with known ground truth | Combines experimental noise with simulated hemodynamic responses [23] [3] |

| Specialized Optical Fibers | Improves optode-scalp coupling | Collodion-fixed fibers minimize motion-induced decoupling [6] |

Methodological Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between evaluation goals, metrics, and correction approaches in fNIRS motion artifact research:

Decision Framework for fNIRS Motion Correction

The systematic evaluation of motion artifact correction techniques in fNIRS research requires careful consideration of both noise suppression and signal preservation metrics. Evidence from comparative studies indicates that wavelet-based filtering generally provides superior performance for common artifact types, while spline interpolation excels specifically for baseline shifts [3] [22]. The emerging approach of incorporating short-separation channels within a general linear model framework demonstrates particularly promising results for comprehensive noise suppression [23] [8].

Researchers should select evaluation metrics that align with their specific research objectives, giving consideration to the nature of expected artifacts, participant population characteristics, and the critical balance between false positives and false negatives in their experimental context. The implementation of standardized evaluation protocols, particularly semisynthetic simulations with ground truth validation, enables direct comparison between methodological approaches and facilitates the selection of optimal correction strategies for specific research scenarios in both basic neuroscience and applied drug development studies.

A Taxonomy of Motion Artifact Removal Techniques: From Hardware to Algorithms

Motion artifacts (MAs) represent a significant challenge in functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) research, often compromising data quality and interpretation. These artifacts arise from imperfect contact between optodes and the scalp due to movement-induced displacement, non-orthogonal contact, or oscillation of the optodes [6]. As fNIRS expands into studies involving naturalistic behaviors, pediatric populations, and clinical cohorts with involuntary movements, effective MA management becomes increasingly critical for data integrity. Hardware-based solutions offer a proactive approach to this problem by providing direct measurement of motion dynamics, enabling more targeted and physiologically informed artifact correction compared to purely algorithmic methods [6] [25].

The fundamental advantage of hardware approaches lies in their ability to capture independent, time-synchronized information about the source of artifacts—whether from head movements, facial muscle activity, jaw movements, or body displacements [6] [5]. This review systematically compares three principal hardware-based solutions: accelerometer-based systems, inertial measurement units (IMUs), and short-separation channels (SSCs). We evaluate their operational principles, implementation requirements, correction efficacy, and suitability for different research scenarios, providing experimental data and performance metrics to guide researchers in selecting appropriate solutions for their specific fNIRS applications.

Comparative Analysis of Hardware Solutions

Table 1: Overview of Hardware-Based Motion Artifact Correction Methods

| Method | Primary Components | Measured Parameters | Implementation Complexity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer | Single- or multi-axis accelerometer | Linear acceleration | Low to moderate | Cost-effective; well-established signal processing pipelines [6] |

| IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) | Accelerometer, gyroscope, (magnetometer) | Linear acceleration, angular velocity, orientation | Moderate to high | Comprehensive movement capture; rich kinematic data [6] |

| Short-Separation Channels | Additional fNIRS optodes at short distances (~8-15mm) | Superficial hemodynamic fluctuations | Moderate | Direct measurement of systemic artifacts; no additional hardware synchronization [25] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Hardware-Based Correction Methods

| Method | Artifact Types Addressed | Compatibility with Real-Time Processing | Evidence of Efficacy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer | Head movements, gross body movements [6] | Yes (multiple methods support real-time application) [6] | Improved signal-to-noise ratio; validated in multiple studies [6] | Limited to detecting acceleration forces only [6] |

| IMU | Head rotations, displacements, complex movement patterns [6] [5] | Yes (with sufficient processing capacity) [6] | Superior for characterizing movement along multiple axes [5] | Higher cost; more complex data integration [6] |

| Short-Separation Channels | Systemic physiological noise, superficial scalp blood flow changes [25] | Limited (primarily used in offline analysis) | Effective for separating cerebral from extracerebral signals [25] | Limited effectiveness for abrupt, high-amplitude motion artifacts [25] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accelerometer-Based Approaches

Accelerometer-based methods employ miniature sensors attached to the fNIRS headgear to record head movement dynamics simultaneously with hemodynamic measurements. The fundamental principle involves using acceleration signals as reference inputs for adaptive filtering techniques that distinguish motion-induced artifacts from neural activity-related hemodynamic changes [6].

Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) implements a recursive least-squares adaptive filter that continuously adjusts its parameters to minimize the difference between the measured fNIRS signal and a reference signal derived from the accelerometer [6]. The algorithm models the measured fNIRS signal (z(n)) as a combination of the true hemodynamic signal and motion-induced noise correlated with accelerometer readings.

Accelerometer-Based Motion Artifact Removal (ABAMAR) employs a two-stage process where motion-contaminated segments are first identified via threshold-based detection on accelerometer data, followed by correction using interpolation or model-based approaches [6]. The correction phase typically involves piecewise cubic spline interpolation or autoregressive modeling to reconstruct the signal within artifact periods.

Experimental Protocol Validation: In validation studies, participants perform controlled head movements (rotations, nods, tilts) at varying speeds and amplitudes while simultaneous fNIRS and accelerometer data are collected [5]. Performance metrics include signal-to-noise ratio improvement, correlation with ground-truth hemodynamic responses, and reduction in false activation rates [6] [5].

IMU-Based Solutions

Inertial Measurement Units integrate multiple sensors—typically a triaxial accelerometer, triaxial gyroscope, and sometimes a magnetometer—providing comprehensive kinematic data including linear acceleration, angular velocity, and orientation relative to the Earth's magnetic field [6]. This multi-modal capture enables more sophisticated movement characterization compared to accelerometer-only systems.

Implementation Framework: IMUs are typically secured to the fNIRS headgear at strategic locations, often on the forehead or temporal regions. The gyroscope component is particularly valuable for detecting rotational movements that may produce minimal linear acceleration but significant optode displacement [6]. Data from all sensors are time-synchronized with fNIRS measurements and often fused using Kalman filtering to create a unified movement reference signal [6].

Blind Source Separation with IMU Reference (BLISSA2RD) represents an advanced approach combining hardware and algorithmic methods. This technique uses IMU data to inform blind source separation algorithms, particularly independent component analysis (ICA), facilitating more accurate identification and removal of motion-related components from fNIRS signals [6].

Experimental Validation: Controlled studies have participants perform specific head movements categorized by axis (vertical, frontal, sagittal), speed (fast, slow), and type (half, full, repeated rotations) while head orientation is simultaneously tracked using computer vision systems for ground-truth comparison [5]. Research demonstrates that occipital and pre-occipital regions are particularly susceptible to upwards or downwards movements, while temporal regions are most affected by lateral bending movements [5].

Short-Separation Channels

Short-separation channels employ additional source-detector pairs placed at minimal distances (typically 8-15mm) compared to standard channels (25-35mm). The fundamental principle is that these short-distance channels primarily detect hemodynamic changes in superficial layers (scalp, skull) rather than cerebral cortex, providing a reference for systemic physiological noise and motion artifacts affecting the scalp circulation [25].

Implementation Configuration: SSCs are integrated directly into the fNIRS cap design, interspersed with conventional channels. Optimal placement varies by brain region studied, with typical configurations including 1-2 SSCs per region of interest. The shallow photon path of SSCs makes them particularly sensitive to motion-induced hemodynamic changes in extracerebral tissues [25].

Signal Processing Approaches: SSC signals are used as regressors in general linear models (GLM) to remove shared variance with standard channels, or in adaptive filtering configurations. More advanced implementations employ SSC data in component-based methods (e.g., principal component analysis) to identify and remove motion-related signal components [25].

Validation Methodology: Efficacy is typically demonstrated by comparing activation maps with and without SSC regression, measuring reductions in false positive activations, and assessing the specificity of retained neural signals using tasks with well-established hemodynamic response profiles [25].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Hardware Correction Workflow

Signal Pathways Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Hardware-Based Motion Artifact Research

| Item | Specification | Research Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triaxial Accelerometer | Range: ±8g, Sensitivity: 8-16g, Sampling: ≥50Hz [26] | Measures linear acceleration in three dimensions | Head movement detection, artifact reference signal [6] |

| IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) | 6-axis (accelerometer + gyroscope) or 9-axis (plus magnetometer), Sampling: ≥52Hz [26] [6] | Comprehensive movement capture (acceleration, rotation, orientation) | Complex motion characterization, multi-parameter artifact correction [6] [5] |

| fNIRS System with Auxiliary Inputs | Analog/digital ports for external sensor synchronization, customizable sampling rates | Integration of motion sensor data with hemodynamic measurements | Hardware-based artifact correction implementations [6] |

| Short-Separation Optodes | Source-detector distance: 8-15mm, compatible with standard fNIRS systems | Isolation of superficial hemodynamic fluctuations | Systemic noise regression, scalp blood flow monitoring [25] |

| Motion Capture System | Video-based tracking with computer vision algorithms (e.g., SynergyNet DNN) [5] | Ground-truth movement validation | Method validation, movement parameter quantification [5] |

| Custom Headgear | Secure mounting solutions for sensors and optodes | Stabilization of equipment during movement studies | Motion artifact research in naturalistic settings [5] |

Hardware-based solutions for motion artifact management in fNIRS offer distinct advantages for researchers requiring high data quality in movement-rich environments. Accelerometers provide a cost-effective solution for general motion detection, while IMUs deliver comprehensive kinematic data for complex movement patterns. Short-separation channels address the specific challenge of superficial physiological noise often confounded with motion artifacts.

The selection of appropriate hardware solutions depends on multiple factors including research population, experimental paradigm, and analysis requirements. For pediatric studies or clinical populations with frequent movement, IMU-based systems provide the most robust movement characterization. For studies focusing on hemodynamic specificity, short-separation channels offer unique advantages in disentangling cerebral and extracerebral signals. Combining multiple hardware approaches often yields superior results compared to any single method.

Future research directions should include standardized validation protocols for hardware solutions, improved real-time processing capabilities, and development of integrated systems that seamlessly combine multiple hardware approaches. As fNIRS continues to expand into naturalistic research paradigms, hardware-based motion artifact management will play an increasingly vital role in ensuring data quality and physiological validity.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) has emerged as a vital neuroimaging tool, particularly for populations such as infants and children, due to its portability and relative tolerance to movement [2] [27]. However, the signals it acquires are highly susceptible to motion artifacts (MAs), which are among the most significant sources of noise and can severely compromise data quality [2] [6]. These artifacts arise from relative movement between optical sensors (optodes) and the scalp, leading to signal contaminants that can obscure the underlying hemodynamic responses associated with neural activity [15]. The challenge is especially pronounced in pediatric and developmental studies, where participants are naturally more active and data collection times are often limited [2] [27].

To address this problem, numerous software-based algorithmic correction methods have been developed, allowing researchers to salvage otherwise unusable data segments. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three fundamental approaches: Spline Interpolation, Moving Average (MA), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The objective is to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of these techniques' performance, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform their analytical choices in motion artifact correction.

Spline Interpolation

The spline interpolation method identifies segments of data contaminated by motion artifacts and models these artifactual periods using a cubic spline. This modeled artifact is then subtracted from the original signal to recover the true physiological data [15] [22]. The process relies on accurate artifact detection, often based on analyzing the moving standard deviation of the signal and setting thresholds for peak identification [22]. Its primary strength lies in effectively correcting baseline shifts and slower, sustained artifacts [22].

Moving Average (MA)

The Moving Average method functions as a high-pass filter, primarily aimed at removing slow drifts from the fNIRS signal [2] [22]. It operates by calculating the average of data points within a sliding window and subtracting this trend from the signal. While effective for slow drifts, it is not typically classified as a dedicated motion correction method like wavelet filtering but is often used in combination with other techniques to improve overall performance [2].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a multivariate technique that decomposes multi-channel fNIRS data into a set of orthogonal components ordered by the amount of variance they explain [14]. Since motion artifacts often have large amplitudes, they are likely to be captured in the first few principal components. Correction is achieved by removing these components before reconstructing the signal [15] [14]. A significant advancement is Targeted PCA (tPCA), which applies the PCA filter exclusively to segments pre-identified as containing motion artifacts, thereby reducing the risk of over-correction and preserving more of the physiological signal [27] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for a motion artifact correction process that incorporates these methods.

Performance Comparison in Experimental Settings

Direct comparisons of these techniques across various populations and task paradigms reveal context-dependent performance.

Comparative Performance Table

Table 1: Comparative performance of Spline, Moving Average, and PCA correction methods across key studies.

| Correction Method | Study Population | Task Paradigm | Key Performance Findings | Cited Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spline Interpolation | Adult stroke patients [15] | Resting-state | Produced the largest average reduction in Mean-Squared Error (MSE) (55%). | Requires accurate MA detection; many user-defined parameters [22] [14]. |

| Spline Interpolation | Young children (3-4 years) [27] | Visual working memory | Retained a high number of trials; performed robustly across metrics. | Consistently outperformed by tPCA in head-to-head comparison [27]. |

| Moving Average (MA) | Children (6-12 years) [2] | Language acquisition | Yielded one of the best outcomes according to five predefined metrics. | Serves more as a filter for slow drifts than a dedicated MA corrector [22]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Adult stroke patients [15] | Resting-state | Significantly reduced MSE and increased Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR). | Can over-correct the signal, removing physiological data [14]. |

| Targeted PCA (tPCA) | Young children (3-4 years) [27] | Visual working memory | An effective technique; consistently outperformed spline interpolation. | Performance depends on multiple user-set parameters for MA detection [14]. |

- Study with Children (Ages 6-12): A direct comparison of six techniques applied to data from a language acquisition task found that Moving Average (MA) and Wavelet methods yielded the best outcomes. In this specific pediatric context, these methods outperformed Spline Interpolation, PCA, and other approaches [2].

- Study with Young Children (Ages 3-4): Research on a visual working memory paradigm concluded that tPCA was the most effective technique for correcting motion artifacts, consistently outperforming Spline interpolation and other methods. Both tPCA and Spline were noted for retaining a high number of trials, which is critical in studies with limited data [27].

- Study with Adult Patients: A systematic comparison using data from stroke patients found that Spline interpolation produced the largest reduction in mean-squared error (MSE), while Wavelet analysis produced the greatest increase in contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR). Both methods, along with PCA, performed significantly better than no correction or trial rejection [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the data in the comparison table, this section outlines the methodologies of two pivotal studies.

Protocol 1: fNIRS during Language Task in Children

- Objective: To compare the efficacy of six motion artifact correction techniques (including Spline, MA, and PCA) on fNIRS data from children [2].

- Participants: Twelve children (eight females, age range: 6.8 to 12.6 years) [2].

- Task: An auditory grammatical judgment language task based on the Test of Early Grammatical Impairment. Children listened to sentences and judged whether they were correct or contained mistakes, pressing a button to respond. The task was a rapid event-related design with 60 trials and a total duration of approximately 7.6 minutes [2].