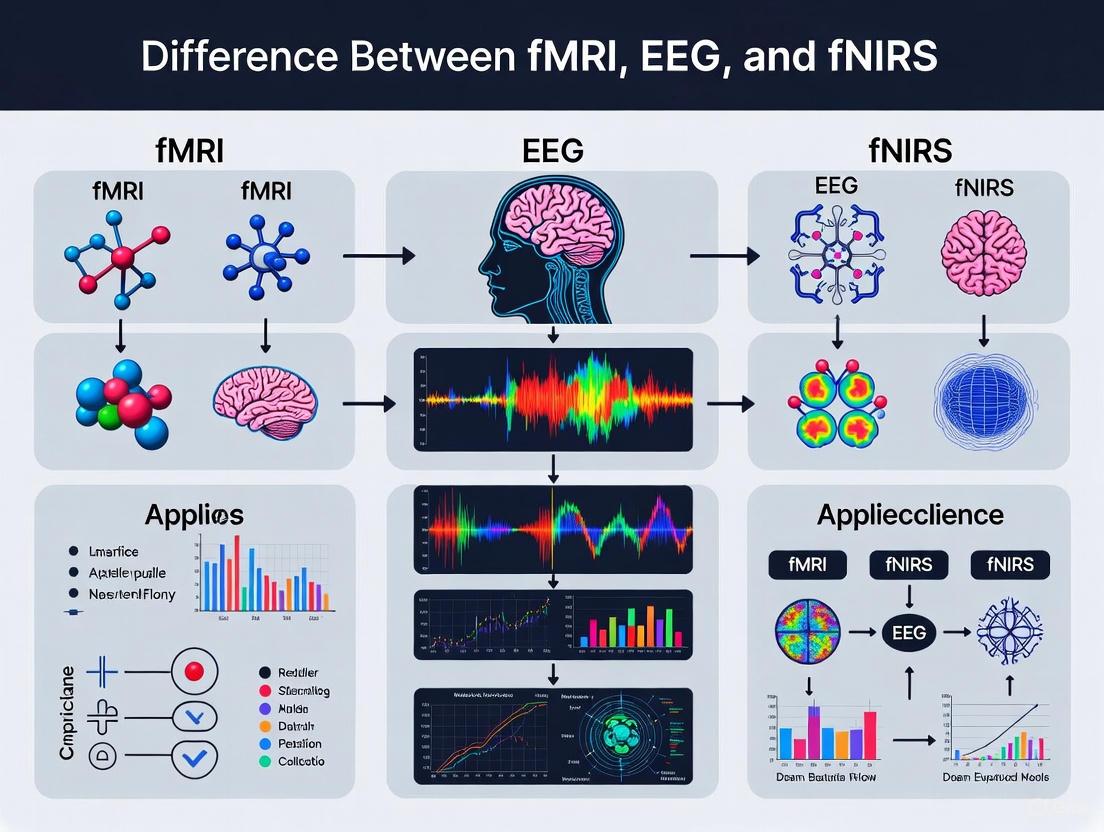

fMRI vs. EEG vs. fNIRS: A Comprehensive Guide to Neuroimaging Modalities for Research and Clinical Applications

This article provides a detailed comparison of three foundational neuroimaging techniques—functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

fMRI vs. EEG vs. fNIRS: A Comprehensive Guide to Neuroimaging Modalities for Research and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of three foundational neuroimaging techniques—functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles, strengths, and limitations of each modality, covering their specific methodological applications from basic research to clinical trials. The content further addresses practical challenges in implementation and data fusion, and offers guidance on modality selection and validation through multimodal approaches. By synthesizing current research and future directions, this guide serves as a strategic resource for optimizing neuroimaging strategies in both biomedical and clinical research contexts.

Understanding the Core Principles: How fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS Measure Brain Activity

The quest to visualize and quantify brain function relies on two distinct classes of physiological signals: the fast electrophysiological currents generated by neural firing and the slower hemodynamic responses that support metabolic demand. Electrophysiological signals represent the direct, instantaneous electrical activity of neurons, primarily measured by techniques like electroencephalography (EEG). In contrast, hemodynamic signals reflect the indirect, blood-borne metabolic consequences of neural activity, typically measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). This fundamental biophysical distinction governs every aspect of neuroimaging, from temporal resolution and spatial specificity to the appropriate experimental design and analytical approach. Understanding the origin, relationship, and practical implications of these signals is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals selecting the optimal tools for probing brain function in health and disease.

The connection between these signals is governed by neurovascular coupling, the biological process that links local neural activity to subsequent changes in cerebral blood flow. When a brain region becomes active, a complex cascade of events leads to an increased delivery of oxygenated blood to that area, typically peaking 2 to 6 seconds after the neural event. This hemodynamic response is the primary source of contrast for both fMRI and fNIRS. While electrophysiological methods capture the neural activity itself with millisecond precision, hemodynamic methods provide a delayed, spatially mapped metabolic portrait of that activity. The integration of these complementary views—either through simultaneous multi-modal acquisition or through informed interpretation of single-modality data—offers a more comprehensive understanding of brain dynamics than either could provide alone.

Core Biophysical Principles

The Electrophysiological Signal

Electrophysiological signals originate from the synchronized firing of populations of neurons, specifically the postsynaptic potentials in cortical pyramidal cells. When these neurons fire in synchrony, the summed electrical currents create a potential large enough to be detected through the skull and scalp by sensitive electrodes. EEG measures these voltage fluctuations, which typically range from 10 to 100 microvolts. The electrical properties of biological tissues, including the skull and scalp, act as a low-pass filter, smearing and attenuating the signal, which fundamentally limits the spatial resolution of EEG.

The electrophysiological signal is characterized by its oscillatory nature, with different frequency bands correlating with distinct brain states. These rhythms are categorized into bands including delta (0.5-4 Hz), theta (4-7 Hz), alpha (8-12 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), and gamma (>30 Hz). Each rhythm is associated with different cognitive or behavioral states; for example, the posterior dominant alpha rhythm is characteristic of a relaxed, awake state with eyes closed and is attenuated by eye opening or mental effort. The key advantage of electrophysiological signals is their exquisite temporal resolution, which is on the order of milliseconds, allowing for the direct observation of neural processing in real-time.

The Hemodynamic Signal

The hemodynamic signal is an indirect metabolic correlate of neural activity, rooted in the brain's intricate vascular system. The primary physiological phenomenon is the hemodynamic response: when a neural population becomes active, its metabolic demands for oxygen and glucose increase. This triggers a complex neurovascular coupling process, leading to a localized increase in cerebral blood flow that actually overcompensates for the oxygen demand. The result is a localized change in the relative concentrations of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR).

This hemodynamic response has a characteristic time course, beginning approximately 1-2 seconds after neural activity, peaking at 4-6 seconds, and then undershooting before returning to baseline. Different neuroimaging techniques capture this signal in distinct ways:

- fMRI measures the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast, which relies on the different magnetic properties of HbO and HbR. Deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic and creates distortions in the local magnetic field, while oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic. The BOLD signal thus primarily reflects changes in deoxygenated hemoglobin.

- fNIRS uses near-infrared light to measure changes in the absorption spectra of HbO and HbR directly, providing separate concentration measurements for both molecules.

The fundamental principle governing blood flow during this response is described by Ohm's law of fluid flow: Flow = Pressure / Resistance. The increased blood flow to active regions is achieved through a reduction in vascular resistance, primarily via the dilation of arterioles. While the hemodynamic response provides excellent spatial localization of brain activity, its temporal resolution is limited by the sluggishness of the vascular response, which unfolds over several seconds.

Quantitative Technical Comparison

The biophysical differences between electrophysiological and hemodynamic signals manifest in distinct performance characteristics for the neuroimaging techniques that measure them. The table below provides a direct, quantitative comparison of these core properties.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities Based on Signal Origin

| Feature | EEG (Electrophysiological) | fMRI (Hemodynamic) | fNIRS (Hemodynamic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Electrical potentials from synchronized neuronal firing [1] | Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast [2] [3] | Changes in oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentration [2] [4] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeters) [2] [1] | High (millimeters) [2] | Moderate (centimeters) [2] [1] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (milliseconds) [2] [1] | Low (seconds) [2] | Low (seconds) [2] [1] |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface [1] | Whole brain [5] | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm) [4] [1] |

| Primary Signal Source | Postsynaptic potentials in cortical pyramidal cells [1] | Changes in deoxygenated hemoglobin due to blood flow [3] | Absorption changes in HbO and HbR in micro-vessels [4] |

| Typical Setup Time | Moderate to long (can be 10+ minutes with gel) [2] | Long (preparation and calibration) [3] | Short (under a minute) [2] |

| Tolerance to Movement | Low - highly susceptible to artifacts [1] | Very low - requires complete stillness [3] | Moderate - relatively robust to movement [3] [1] |

This comparison highlights the inherent trade-offs in neuroimaging. EEG's millisecond temporal resolution is ideal for tracking the rapid dynamics of brain communication but provides a blurry spatial picture. Conversely, fMRI can localize activity to small, specific brain structures but cannot track the rapid sequence of neural events. fNIRS occupies a middle ground, offering better spatial resolution than EEG and greater portability and motion tolerance than fMRI, though it cannot image deep brain structures.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Simultaneous fNIRS and ERP during a Stroop Task

This protocol is designed to capture both the hemodynamic and electrophysiological correlates of cognitive conflict and control.

- Objective: To investigate the relationship between hemodynamic responses in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and event-related potentials (ERPs) during the Chinese-character color-word Stroop task [6].

- Experimental Design:

- Task: A modified Stroop task with three conditions: congruent, incongruent, and neutral stimuli. Subjects are required to name the color of the presented character while ignoring its semantic meaning.

- Design: Event-related or block design.

- Measurements:

- fNIRS: Continuous-wave fNIRS is used to monitor relative changes in oxy- (HbO), deoxy- (HbR), and total hemoglobin concentration in the PFC.

- ERP: EEG is recorded simultaneously to characterize electrophysiological components, specifically P450, N500, and P600.

- Procedure:

- Set up the EEG cap and fNIRS optodes on the participant's scalp, ensuring proper placement over the PFC according to the international 10-20 system.

- Synchronize the fNIRS and EEG acquisition systems using a shared trigger or clock signal.

- Conduct a baseline recording with the participant at rest.

- Present the Stroop task stimuli in a randomized order. Each trial involves a brief presentation of a character, followed by an inter-trial interval.

- Record the participant's behavioral responses (accuracy and reaction time).

- Conclude with another resting-state recording.

- Data Analysis:

- fNIRS Data: Preprocess the optical data to convert raw light intensity changes into hemoglobin concentration changes using the modified Beer-Lambert law. Analyze the amplitude and timing of HbO and HbR responses for each stimulus condition.

- ERP Data: Preprocess the EEG data (filtering, artifact removal, epoching). Average the epochs time-locked to the stimulus onset to extract the ERP components (P450, N500, P600).

- Correlation Analysis: Perform statistical correlation analysis between the hemodynamic parameters (e.g., HbO amplitude) and the electrophysiological parameters (e.g., P600 amplitude) across the different conditions and subjects.

This protocol revealed that the P600 ERP component correlated significantly with hemodynamic parameters in the PFC, suggesting a link between this late positive potential and the conflict-solving function of the PFC. It also found that deoxy-Hb concentration showed higher sensitivity to the Stroop task than other hemodynamic signals [6].

Protocol 2: fNIRS of Brain Activation during a Balance Task

This protocol leverages the portability of fNIRS to study brain function during whole-body movement, a scenario where fMRI is impractical.

- Objective: To measure brain activation in vestibular and motor cortices during an active balancing task using fNIRS [4].

- Experimental Design:

- Task: A video game-based balance task (Nintendo Wii Fit skiing game) requiring the participant to shift their center of mass to control an avatar on a screen.

- Conditions: Beginner and advanced difficulty levels, with standing rest periods before and after each trial.

- Control Task (subset of participants): Watch the video game while standing still to control for visual stimulation.

- Procedure:

- Fit the participant with a 32-channel fNIRS head cap, ensuring optodes cover regions of interest (frontal, motor, sensory, and temporal cortices).

- Register the 3D position of the fNIRS probe on the participant's head for anatomical co-registration.

- Have the participant stand on the balance board.

- Begin with a 30-second standing rest period.

- Start the skiing game; the task duration is self-paced (~40-60 seconds).

- Follow with a 30-second post-task standing rest.

- Repeat for multiple trials at different difficulty levels.

- Data Analysis:

- Process fNIRS data to obtain HbO and HbR time courses.

- Use a general linear model (GLM) to compare the hemodynamic response during the active task period to the rest periods.

- Statistically compare activation between different difficulty levels and across brain regions.

This study successfully identified activation in the superior temporal gyrus, a region implicated in vestibular function, which was modulated by the difficulty of the balance task. This demonstrates fNIRS's unique capability to image cortical activity during whole-body movement [4].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core signaling pathways and experimental workflows for hemodynamic and electrophysiological neuroimaging.

Hemodynamic Neurovascular Coupling Pathway

This diagram outlines the Neurovascular Coupling Pathway from a neural event to the measurable hemodynamic signal. The process begins with a neural event leading to increased neural activity and glutamate release. This triggers signaling processes in astrocytes, which ultimately cause arteriole dilation. This dilation reduces vascular resistance, leading to a large increase in cerebral blood flow. The change in blood flow and volume alters the local concentration of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin, which is the final common path detected by both fMRI (as the BOLD signal) and fNIRS (as an optical absorption change).

Electrophysiological Signal Generation and Measurement

This diagram illustrates the Electrophysiological Signal Pathway measured by EEG. The process is initiated by a stimulus, leading to the synchronized firing of large populations of neurons, particularly cortical pyramidal cells. The primary signal source is the summation of postsynaptic potentials from these cells. These individual currents summate to create a combined electrical field strong enough to propagate through the biological tissues. This signal undergoes significant distortion and attenuation as it volume conducts through the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp. The final result is a weak electrical potential in the microvolt range that is detected by electrodes on the scalp.

Multimodal Experimental Workflow

This Multimodal Experimental Workflow diagram shows how hemodynamic and electrophysiological data are acquired and integrated. A participant performs a task, generating brain activity. This single neural event gives rise to two parallel physiological processes: a fast electrophysiological signal measured by EEG/MEG with millisecond resolution, and a slow hemodynamic signal, mediated by neurovascular coupling, which peaks 4-6 seconds later and is measured by fMRI/fNIRS. The signals from both modalities are synchronized during acquisition and then combined during joint analysis to provide a spatiotemporally rich account of brain function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and solutions used in experiments leveraging hemodynamic and electrophysiological signals, with a focus on their specific functions in the research context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Neuroimaging Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Relevant Modality |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Electrodes (Ag/AgCl) | Sensors placed on the scalp to detect electrical potentials. High-quality electrodes ensure stable impedance and low-noise recording. | EEG [7] |

| Electrode Gel/Grounding Solution | Electrolyte gel or solution applied to electrodes to facilitate electrical conduction between the scalp and the electrode, reducing impedance. | EEG [2] |

| fNIRS Optodes | Fiber optic components comprising light sources (emitters) and detectors placed on the scalp to deliver near-infrared light and measure its attenuation after passing through brain tissue. | fNIRS [4] |

| fNIRS Head Cap | A flexible cap (often plastic/Velcro) that holds fNIRS optodes in a precise geometric arrangement on the scalp, often based on the international 10-20 system. | fNIRS [4] |

| 3D Digitizer (e.g., Polhemus FastSCAN) | A magnetic or optical stylus system used to record the precise 3D locations of EEG electrodes or fNIRS optodes on the participant's head. This is critical for anatomical co-registration of the data with brain atlases or individual MRI scans. | EEG, fNIRS [4] |

| Synchronization Trigger Box | Hardware device that generates a TTL pulse or other shared signal to synchronize the timing of stimulus presentation, task events, and data acquisition across multiple recording systems (e.g., fNIRS and EEG). | Multimodal (EEG+fNIRS) [1] |

| Anatomical Atlas Software (e.g., AtlasViewer) | Software solutions that use digitized probe positions and standard brain atlases (or individual MRIs) to estimate the underlying brain regions measured by each fNIRS channel or EEG electrode. | fNIRS, EEG [3] |

The distinction between hemodynamic and electrophysiological signals is not merely technical but fundamental to interpreting brain function. Hemodynamic methods like fMRI and fNIRS provide a high-spatial-resolution, indirect map of the brain's metabolic landscape, ideal for pinpointing where cognitive processes occur. Electrophysiological methods like EEG offer a high-temporal-resolution, direct measurement of the brain's electrical storm, essential for understanding when and how these processes unfold. The choice between them—or the decision to integrate them multimodally—is therefore dictated by the research question itself.

For the neuroscientist, this means that studies of sustained brain states, localization of function, or investigations involving movement are well-served by hemodynamic tools. In contrast, research into rapid perceptual processes, neural oscillations, or real-time brain-computer interfaces demands the temporal fidelity of EEG. For the drug development professional, these principles inform the selection of biomarkers for clinical trials; hemodynamic signals may better reflect sustained changes in brain metabolism or network connectivity, while electrophysiological signals can offer immediate feedback on a drug's impact on neural excitability and transmission. As neuroimaging evolves, the most powerful insights will continue to come from studies that strategically exploit the complementary nature of these two foundational windows into the working brain.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) has established itself as a cornerstone of modern cognitive neuroscience, providing a non-invasive window into human brain function. At the heart of most fMRI research lies the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast, an indirect measure of neural activity that has revolutionized our ability to map brain function with high spatial precision. The BOLD signal originates from the intricate physiological coupling between neuronal activity, metabolic demand, and subsequent hemodynamic changes in cerebral blood flow, volume, and oxygenation [8]. When a brain region becomes active, a cascade of vascular events leads to an influx of oxygenated blood that exceeds the local metabolic demand, resulting in a measurable change in the ratio of oxygenated to deoxygenated hemoglobin [9]. This neurovascular coupling forms the fundamental basis of BOLD contrast imaging.

Within the landscape of functional neuroimaging, fMRI exists alongside other prominent modalities, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Electroencephalography (EEG) measures the electrical activity generated by synchronized firing of neuronal populations with millisecond temporal resolution, but with limited spatial accuracy due to the dispersion of electrical signals through the skull and scalp [10] [11]. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) shares fMRI's foundation in hemodynamic response measurement but utilizes near-infrared light to detect changes in hemoglobin concentrations, offering a portable alternative with trade-offs in penetration depth and spatial resolution [3] [9]. Understanding the BOLD signal's mechanisms, advances, and limitations is therefore essential for contextualizing its role within the multimodal toolkit of modern neuroscience and drug development research.

The Core Biophysics of the BOLD Signal

Physiological Origins and the Hemodynamic Response

The BOLD signal is an indirect measure of neural activity that relies on the tight coupling between neuronal activation and subsequent vascular changes. The underlying physiology can be summarized as follows: during increased neural activity, there is a rise in metabolic demand for oxygen and glucose. This triggers a complex signaling cascade involving astrocytes and vascular cells, leading to a pronounced increase in local cerebral blood flow (CBF) and volume (CBV) that overshoots the actual oxygen consumption [8] [9]. The result is a localized decrease in the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin (dHb), the paramagnetic component of blood that creates magnetic field inhomogeneities.

The BOLD signal fundamentally arises from the different magnetic properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin. Oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic (slightly repelled by a magnetic field), while deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic (attracted to a magnetic field) [9]. This paramagnetism causes deoxyhemoglobin to act as an endogenous contrast agent that distorts the surrounding magnetic field, accelerating the dephasing of hydrogen proton spins and reducing the MRI signal intensity. During neural activation, the surplus of oxygenated blood reduces the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin, leading to a more homogeneous local magnetic field, slower spin dephasing, and consequently an increase in the measured T2*-weighted MRI signal [8] [9]. This signal change is relatively small, typically ranging from 0.5% to 5% at common field strengths (1.5T-3T), but is consistently detectable with appropriate experimental designs.

From Magnetic Susceptibility to Signal Acquisition

The transition from physiological changes to measurable MRI signal involves sophisticated biophysical processes. The magnetic susceptibility difference between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood creates microscopic magnetic field gradients around blood vessels. These gradients cause intravoxel dephasing, where hydrogen protons in water molecules precess at different frequencies depending on their spatial position relative to blood vessels. The net signal detected in fMRI experiments represents the integrated effect of countless such spin dephasing events across the imaging voxel [12].

The complex nature of the BOLD signal presents both opportunities and challenges for high-resolution mapping. The signal exhibits differential sensitivity across the vascular hierarchy, with substantial contributions from larger draining veins that may be displaced from the actual site of neural activity. This vascular bias has driven the development of high-field systems and advanced acquisition techniques to better localize the parenchymal response originating from the capillary bed [8]. Furthermore, the BOLD signal represents a composite measure influenced by multiple physiological variables including cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume (CBV), and the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption (CMRO2). Disentangling these contributions requires complementary techniques such as arterial spin labeling (for CBF) or vascular space occupancy (for CBV), which provide additional constraints for interpreting the BOLD response [8].

Diagram Title: BOLD Signal Physiological Cascade

Technical Advances in High-Resolution Spatial Mapping

Pushing the Spatial Boundaries of fMRI

High-resolution fMRI represents a significant advancement beyond conventional neuroimaging, enabling the discrimination of brain activity at the scale of cortical layers and columns. While standard human fMRI typically employs voxel sizes of 3×3×3 mm³, high-resolution protocols now achieve submillimeter resolutions (often 0.5-0.8 mm isotropic), with animal studies pushing further to 50-500 μm ranges [8]. This enhanced spatial precision reveals anatomical features previously obscured in conventional fMRI, including distinct vascular compartments (arteries, veins, and capillaries) and the layered organization of the cerebral cortex [8].

The transition to high-resolution fMRI carries profound implications for BOLD signal interpretation and modeling. At conventional resolutions, the contributions of various vascular components and cortical layers are averaged within each voxel, permitting relatively simple hemodynamic models. In contrast, high-resolution data exposes the intrinsic heterogeneity of these elements, necessitating more sophisticated, multi-compartment models that explicitly represent laminar differences in neurovascular coupling, metabolism, and hemodynamic response properties [8]. These advanced models must account for the differential sensitivity of BOLD signals across cortical depths and their relationship to specific neural computations, such as feedforward versus feedback processing that are segregated across cortical layers [8].

Methodological Innovations and Challenges

The pursuit of higher spatial resolution in fMRI involves navigating significant technical trade-offs and leveraging technological innovations. Key challenges include the limited signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at small voxel sizes, increased sensitivity to physiological noise and subject motion, and the need to maintain reasonable temporal resolution and brain coverage [8]. The development of ultra-high field scanners (7T and beyond) for human research has been instrumental in addressing these limitations, providing both increased intrinsic SNR and enhanced BOLD contrast-to-noise ratio [8].

Advanced acquisition and reconstruction techniques further enable high-resolution mapping. Simultaneous multi-slice acquisitions accelerate data collection, while specialized RF coils improve spatial encoding efficiency. Additionally, the move toward high-resolution has prompted renewed interest in the complex-valued nature of the MRI signal, particularly the phase component that is typically discarded in conventional analyses. Numerical simulations suggest that the phase signal exhibits distinctive spatial variation patterns at high resolutions that may provide complementary information to the standard magnitude signal [12]. However, practical utilization of phase data remains challenging due to issues such as phase wrapping and the complex relationship between phase variations and underlying vascular architecture [12].

Table 1: Technical Considerations in High-Resolution fMRI

| Parameter | Conventional fMRI | High-Resolution fMRI | Implications for BOLD Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Voxel Size | 3×3×3 mm³ | 0.5-1.0 mm isotropic (human); 50-500 μm (animals) | Reduced partial volume effects; reveals vascular architecture [8] |

| Spatial Localization | Lumps multiple cortical layers/columns | Distinguishes layers/columns | Enables layer-specific neurovascular coupling studies [8] |

| Vascular Contributions | Mixed arterial, capillary, venous signals | Can separate vascular compartments | Improves localization to parenchymal activity [8] |

| Modeling Complexity | Simple hemodynamic models | Multi-compartment models required | Incorporates laminar differences in metabolism/hemodynamics [8] |

| Phase Signal Utility | Typically discarded | Potential spatial information source | May provide complementary vascular information [12] |

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities

Fundamental Differences in Signal Origin and Properties

Understanding the BOLD signal's role in neuroscience requires contextualization within the broader landscape of neuroimaging technologies. fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS each capture distinct facets of brain activity through different biophysical mechanisms with complementary strengths and limitations. The BOLD signal underlying fMRI provides an indirect measure of neural activity mediated by neurovascular coupling, with a characteristic temporal delay of 2-6 seconds following neural events [10] [3]. In contrast, EEG directly measures postsynaptic electrical potentials with millisecond temporal resolution, enabling real-time tracking of neural dynamics but with limited spatial precision due to the blurring effect of the skull and scalp [10] [11]. fNIRS shares fMRI's foundation in hemodynamic response measurement but utilizes optical techniques to detect changes in hemoglobin concentrations, creating a middle ground with better portability than fMRI but more restricted depth penetration [3] [9].

The spatial and temporal resolution profiles of these modalities reflect their underlying physical principles. fMRI offers the highest spatial resolution (millimeter range) and whole-brain coverage, making it ideal for mapping distributed neural networks and localized functional specialization [9]. EEG provides unparalleled temporal resolution (milliseconds) essential for tracking rapid neural dynamics but suffers from limited spatial accuracy (centimeters) and poor sensitivity to subcortical structures [10] [11]. fNIRS occupies an intermediate position with spatial resolution superior to EEG but inferior to fMRI, and temporal characteristics that are slower than EEG but potentially faster than fMRI depending on acquisition parameters [3] [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities

| Characteristic | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Measured | BOLD contrast (deoxyhemoglobin) [9] | Electrical potentials on scalp [10] | Hemoglobin concentration changes [3] |

| Spatial Resolution | ~1-3 mm (high-resolution: <1 mm) [8] | ~1-2 cm [11] | ~1-3 cm [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | ~1-3 seconds [10] | ~1-100 milliseconds [11] | ~0.1-1 second [3] |

| Depth Penetration | Whole brain [9] | Primarily cortical surface [11] | Superficial cortex (1-2 cm) [11] |

| Portability | Low (fixed scanner) [10] | High (wearable systems) [11] | High (wearable systems) [3] |

| Key Strength | Spatial resolution, whole-brain coverage [9] | Temporal resolution, direct neural measure [11] | Portability, motion tolerance [3] |

| Primary Limitation | Indirect measure, scanner environment [9] | Poor spatial localization [10] | Limited depth penetration [3] |

Practical Considerations for Research and Clinical Applications

The practical implementation of each neuroimaging modality involves significant differences in cost, accessibility, and operational constraints. fMRI systems represent the highest capital investment ($1,000+ per scan) and require dedicated physical infrastructure, specialized personnel, and compatible response equipment [10] [2]. The scanner environment imposes substantial constraints on experimental design, including restrictions on participant movement, contraindications for metal implants, challenges with claustrophobia, and interference from acoustic scanner noise [9]. These factors limit the ecological validity of many fMRI paradigms and exclude certain participant populations.

EEG and fNIRS offer more accessible alternatives with lower operational costs and greater flexibility in experimental settings. EEG systems are relatively affordable and portable, enabling studies in naturalistic environments and with populations difficult to scan in MRI (e.g., infants, patients with implants) [10] [11]. fNIRS shares these advantages while providing better spatial localization than EEG and higher tolerance for movement artifacts [3]. However, both EEG and fNIRS face limitations in imaging deep brain structures and require careful consideration of source localization challenges. For drug development research, these practical considerations significantly influence modality selection based on target population, mechanism of action, and required spatial and temporal precision for detecting intervention effects.

Multimodal Integration: Converging Evidence from Complementary Techniques

Simultaneous Acquisition and Correlative Approaches

The complementary strengths of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS have motivated substantial interest in multimodal integration strategies that combine information from multiple imaging techniques. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI recording represents the most established multimodal approach, capitalizing on fMRI's spatial precision and EEG's temporal resolution to study brain dynamics across complementary timescales [13] [14]. This integration has demonstrated reproducible correlations between resting-state functional connectivity measured with both modalities, with crossmodal correlations of approximately r ≈ 0.3 consistently observed across different scanner field strengths (1.5T to 7T) and EEG electrode densities [14]. These correlations are strongest in the EEG beta frequency band and are particularly evident in homotopic connections between brain hemispheres and within intrinsic connectivity networks [14].

The technical challenges of multimodal integration are substantial, particularly for simultaneous acquisitions. In simultaneous EEG-fMRI, the MRI environment generates significant artifacts in EEG recordings, including gradient-induced and ballistocardiographic artifacts that require sophisticated preprocessing pipelines for removal [13]. Quantitative assessments reveal that despite optimized artifact correction, simultaneous recording conditions can produce subtle but significant changes in both EEG fast Fourier transform (FFT) amplitudes and fMRI temporal signal-to-noise ratio (TSNR) compared to separate acquisitions [13]. These findings highlight the importance of quality control measures when implementing multimodal designs, particularly for research questions focusing on brain regions or frequency bands most susceptible to acquisition artifacts.

Applications in Basic Research and Clinical Translation

Multimodal neuroimaging approaches have yielded significant insights into both basic brain function and clinical disorders. The combination of fMRI with EEG has been particularly valuable for elucidating the relationship between electrophysiological phenomena and their hemodynamic correlates, improving our understanding of fundamental neurovascular coupling mechanisms [13] [14]. In clinical populations, integrated fNIRS-EEG has emerged as a promising tool for monitoring motor recovery after stroke, leveraging the complementary information provided by electrical and hemodynamic signals to characterize cortical reorganization processes [15]. Quantitative EEG parameters such as the power ratio index (PRI) and brain symmetry index (BSI) show correlation with functional motor outcomes, providing potential prognostic biomarkers that may guide rehabilitation strategies [15].

For drug development, multimodal approaches offer enhanced capability for detecting and characterizing neurophysiological effects of pharmacological interventions. The combination of techniques sensitive to different aspects of brain function can provide a more comprehensive assessment of drug mechanisms, target engagement, and treatment response. fMRI's whole-brain coverage and spatial precision complements EEG's sensitivity to neurophysiological dynamics and fNIRS's practicality for longitudinal monitoring in more naturalistic settings. This integrated perspective is particularly valuable for complex disorders where pathophysiology spans multiple spatial and temporal scales, such as epilepsy, neurodegenerative diseases, and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Diagram Title: Multimodal Neuroimaging Research Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Protocol Design for High-Resolution fMRI Studies

Implementing high-resolution fMRI requires careful consideration of multiple methodological factors to balance spatial resolution, signal quality, and experimental feasibility. Key parameters include magnetic field strength, pulse sequence selection, voxel size, and coverage. Ultra-high field systems (≥7T) are increasingly preferred for high-resolution studies due to their enhanced BOLD sensitivity and intrinsic SNR advantages [8]. Sequence selection typically involves T2*-weighted gradient-echo EPI or partial k-space acquisitions that optimize BOLD contrast while minimizing distortion and signal dropout in regions with magnetic susceptibility variations.

Protocol optimization must address the inherent trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and brain coverage. Reduced voxel sizes diminish SNR, potentially necessitating increased repetition times (TR) or additional signal averaging to maintain detection power. These adjustments consequently extend scan durations and increase vulnerability to physiological noise and motion artifacts [8]. Strategic compromises often include limiting high-resolution acquisition to specific regions of interest rather than whole-brain coverage, or employing multi-band acceleration techniques to preserve temporal resolution. For pharmacological fMRI studies, these considerations are particularly important as drug effects may manifest as subtle BOLD signal changes requiring adequate statistical power for detection.

Quality Assurance and Data Processing

Robquality control and specialized processing pipelines are essential components of high-resolution fMRI methodology. Quality assessment should monitor temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR), physiological noise contamination, and subject motion throughout the acquisition [13]. For studies targeting cortical layer-specific activation, additional considerations include accounting for vascular effects from surface vessels, which can be addressed through surface regression techniques or vascular space occupancy (VASO) methods that enhance microvascular specificity [8].

Advanced preprocessing and analysis strategies further support high-resolution applications. Anatomical co-registration requires increased precision, often employing surface-based alignment techniques that better accommodate cortical folding patterns. Statistical analyses must address the multiple comparisons problem arising from the larger number of voxels while maintaining sensitivity to detect potentially focal activations. For laminar fMRI, specialized modeling approaches incorporate cortical depth-dependent hemodynamic response functions and account for the point spread function of the BOLD signal across layers [8]. These methodological refinements enable more accurate interpretation of high-resolution findings and their relationship to underlying neural computation architecture.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced fMRI

| Material/Technique | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-High Field Scanners (7T+) | Increases BOLD sensitivity and SNR for smaller voxels [8] | High-resolution and laminar fMRI studies [8] |

| Multi-Channel RF Coils | Enhances spatial encoding and parallel imaging capabilities [8] | Accelerated high-resolution acquisitions [8] |

| Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) | Provides quantitative CBF measurement alongside BOLD [8] | Disambiguating CBF and CMRO₂ contributions to BOLD [8] |

| Vascular Space Occupancy (VASO) | Measures CBV changes with better microvascular specificity [8] | Reducing venous contributions in high-resolution fMRI [8] |

| Multi-Band Sequences | Accelerates data acquisition through simultaneous multi-slice imaging [13] | Maintaining temporal resolution at high spatial resolution [13] |

| Cardiorespiratory Monitoring | Records physiological data for noise modeling [13] | Mitigating physiological noise in high-resolution data [13] |

| EEG-fMRI Compatible Systems | Enables simultaneous electrophysiological and hemodynamic recording [13] | Multimodal studies of neurovascular coupling [13] |

The BOLD signal remains a powerful tool for mapping human brain function, with ongoing technical advances continually expanding its spatial resolution and interpretative fidelity. High-resolution fMRI represents the cutting edge of these developments, pushing toward the scale of cortical columns and layers to reveal the fine-grained functional architecture of the brain. Nevertheless, the BOLD signal remains an indirect measure of neural activity with complex physiological underpinnings that must be carefully considered in experimental design and interpretation.

The future of fMRI and its role within the neuroimaging landscape will likely be shaped by several converging trends. Continued development of ultra-high field systems, sophisticated acquisition sequences, and advanced modeling approaches will further enhance spatial resolution and specificity. Simultaneously, the strategic integration of fMRI with complementary modalities like EEG and fNIRS will provide increasingly comprehensive characterizations of brain function across spatial and temporal domains. For researchers and drug development professionals, this multimodal perspective offers a powerful framework for investigating brain function in health and disease, leveraging the unique strengths of each technique while mitigating their individual limitations. As these technologies evolve, they promise to deepen our understanding of the human brain and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

In the multimodal landscape of modern neuroimaging, Electroencephalography (EEG) occupies a unique and crucial niche by providing direct measurement of neural electrical activity with unmatched temporal precision. While functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) excels at spatial localization of brain activity and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) offers a balance of portability and hemodynamic measurement, EEG captures the brain's rapid electrical dynamics on a millisecond scale [2] [3] [16]. This technical deep dive explores the biophysical foundations, methodological approaches, and research applications of EEG, with particular focus on its role in complementing other neuroimaging modalities within a comprehensive brain investigation framework.

EEG's fundamental advantage lies in its direct measurement of the brain's electrical signals, unlike the indirect hemodynamic responses measured by fMRI and fNIRS [16]. Where fMRI tracks blood oxygenation changes with high spatial resolution but limited temporal resolution (seconds), and fNIRS measures cortical hemodynamics with better portability but similar temporal constraints, EEG captures neural events as they unfold in real-time [17] [2] [3]. This temporal precision makes EEG uniquely suited for investigating rapid cognitive processes, sensory perception, and the dynamic interplay of brain networks [18] [16].

Neural Basis of EEG Signals

Biophysical Foundations

The electrical potentials measured by EEG originate primarily from the summed postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal cells in the cerebral cortex [18]. These excitable cells function with intrinsic electrical properties, and their coordinated activity generates detectable magnetic and electrical fields [18]. When neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, they cause ion channels to open or close, resulting in voltage changes that last in the extracellular space for up to 200 milliseconds [18].

Unlike action potentials, which are too brief and asynchronous to be detected at the scalp, postsynaptic potentials involve slower changes in membrane permeability that occur synchronously across large populations of similarly oriented pyramidal cells [18]. The pyramidal cells' perpendicular orientation to the cortical surface creates a consistent dipole arrangement that allows their electrical fields to summate rather than cancel out, producing potentials strong enough to be detected through the intervening tissues of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp [18] [16].

Signal Characteristics and Measurement

EEG records the algebraic sum of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials from millions of cortical neurons [18]. The electrical signal measured at the scalp represents the difference in electrical potential between two sites (typically termed "active" and "reference") over time [18]. These potential differences are extremely small, measured in microvolts (μV), requiring substantial amplification for analysis [18].

The placement of electrodes follows standardized systems such as the International 10-20 system, which ensures consistent positioning across subjects and studies [18] [16]. Modern high-density EEG systems can utilize 64, 128, or more electrodes distributed across the scalp, improving spatial sampling though still limited by the fundamental physics of electrical field dispersion through volume conduction [2] [18].

Methodological Framework for EEG Research

Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) Methodology

Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) represent a cornerstone of EEG experimental methodology, enabling researchers to extract neural responses time-locked to specific sensory, cognitive, or motor events [18]. Unlike continuous EEG recording, which reflects ongoing brain activity mixed with various neural processes, ERPs isolate the brain's response to discrete stimuli through signal averaging [18].

The ERP methodology involves repeated presentation of a stimulus while continuously recording EEG, then segmenting the EEG into epochs time-locked to stimulus onset [18]. Averaging these epochs across many trials preserves the consistent, stimulus-related neural activity while canceling out random, non-task-related brain activity and noise [18]. The resulting waveform reveals characteristic components (positive and negative peaks) that reflect specific stages of information processing [18].

Key ERP Components in Cognitive Research

ERP components are typically labeled according to their polarity (P for positive, N for negative) and their approximate latency in milliseconds [18]. These components reflect distinct stages of neural processing, from basic sensory perception to higher-order cognitive operations:

Early Components (P100, N100, P200): Generally linked with basic, low-level perception and considered largely automatic in nature [18]. These components are reliably elicited whenever a perceptual stimulus is presented and reflect initial sensory processing in modality-specific cortical areas.

N400 Component: Discovered by Kutas and Hillyard (1980), the N400 is a negativity peaking around 400 ms post-stimulus that is strongly associated with semantic processing [18]. It has been extensively studied in language research, showing sensitivity to semantic incongruity, word frequency, and contextual integration [18].

P300 Component: A positive deflection occurring approximately 300 ms after stimulus onset, the P300 is associated with attention allocation and context updating in working memory [18]. This component is often utilized in cognitive assessment and brain-computer interface applications.

Table 1: Characteristic ERP Components in Cognitive Neuroscience Research

| Component | Latency (ms) | Polarity | Functional Correlation | Primary Neural Generators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P100 | 80-120 | Positive | Early visual processing | Occipital cortex |

| N100 | 80-120 | Negative | Auditory/visual attention | Temporal/occipital cortex |

| P200 | 150-250 | Positive | Feature detection | Sensory-specific cortices |

| N200 | 200-350 | Negative | Conflict monitoring | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| P300 | 250-500 | Positive | Context updating | Temporoparietal junction |

| N400 | 300-500 | Negative | Semantic processing | Temporal lobes |

| Late Positive Potential (LPP) | 500-800 | Positive | Emotional processing | Parieto-occipital regions |

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities

Technical Specifications Across fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

Each major neuroimaging technology offers distinct advantages and limitations based on their underlying physiological signals and measurement principles. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for selecting the appropriate methodology for specific research questions and for effectively integrating multiple modalities.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities

| Parameter | EEG | fMRI | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond level [2] [18] | Seconds (0.33-2 Hz) [17] [2] | Seconds (hemodynamic response) [17] [16] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeters) [2] [16] | High (millimeters) [17] [2] | Moderate (centimeters) [17] [2] |

| Depth Penetration | Cortical surface [16] | Whole brain [17] | Superficial cortex (1-2 cm) [17] [2] |

| Measured Signal | Electrical potentials [18] | Blood oxygenation (BOLD) [17] | Hemoglobin concentration [17] |

| Portability | High [16] | None [17] [3] | High [17] [3] |

| Environment | Flexible [16] | Restricted [17] | Naturalistic [17] [3] |

| Participant Motion | Sensitive [16] | Highly sensitive [17] | Tolerant [3] [16] |

Complementary Strength in Multimodal Integration

The combination of EEG with fMRI and fNIRS leverages their complementary strengths to overcome individual limitations [17] [19]. Multimodal approaches can simultaneously capture the when (EEG), where (fMRI), and how (integrating temporal and spatial information) of neural processes [19].

EEG and fNIRS integration is particularly promising for naturalistic studies, as both modalities offer some degree of portability and motion tolerance [20] [16]. This combination provides concurrent measures of electrical neural activity and hemodynamic responses, enabling researchers to investigate neurovascular coupling in real-world settings [20] [16]. Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach for semantic decoding during mental imagery tasks [20].

Similarly, simultaneous EEG-fMRI recording, though technically challenging due to electromagnetic interference, provides unparalleled spatiotemporal characterization of brain activity [19]. The trimodal integration of EEG, fMRI, and optical imaging (EROS) represents the cutting edge of multimodal neuroimaging, offering proof-of-concept evidence for comprehensive brain function investigation [19].

Experimental Implementation and Protocols

Standardized Experimental Paradigm

A typical EEG experiment follows a structured protocol to ensure reproducibility and valid interpretation of results. The standard setup includes:

Participant Preparation: Proper scalp preparation including cleaning and application of conductive gel or saline solution to ensure low impedance at electrode-skin interfaces [16]. Electrode placement according to the International 10-20 system or high-density configurations [18].

Stimulus Presentation: Controlled presentation of visual, auditory, or somatosensory stimuli using precision timing software to ensure accurate time-locking of neural responses [18]. Stimulus duration and inter-stimulus intervals are optimized for the specific ERP components of interest.

Data Acquisition: Continuous EEG recording with appropriate sampling rates (typically 250-1000 Hz or higher) to capture neural dynamics without aliasing [18]. Simultaneous recording of behavioral responses (reaction time, accuracy) when applicable.

Task Design: Implementation of specific cognitive tasks targeting particular neural processes. For language studies, this might include semantic categorization, syntactic violation detection, or phonological processing tasks [18].

Data Processing Pipeline

Raw EEG data undergoes extensive processing to extract meaningful neural signals:

Preprocessing: Filtering (typically 0.1-30 Hz for ERPs), artifact removal (ocular, cardiac, muscular), and bad channel rejection [18].

Epoch Extraction: Segmentation of continuous data into time windows surrounding stimulus events (e.g., -200 to 800 ms relative to stimulus onset) [18].

Baseline Correction: Removal of DC offsets by subtracting the mean amplitude of the pre-stimulus period from the entire epoch [18].

Averaging: Trial averaging within conditions to enhance signal-to-noise ratio and reveal consistent stimulus-related activity [18].

Component Analysis: Identification and quantification of specific ERP components through peak analysis, mean amplitude measurements, or latency analysis [18].

Table 3: Essential Research Equipment for EEG Studies

| Equipment | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Amplifier | High-input impedance, 24-bit resolution, >100 dB common-mode rejection | Signal amplification and digitization while minimizing noise and interference |

| Active Electrodes | Integrated impedance conversion, silver/silver-chloride (Ag/AgCl) composition | Superior signal quality with reduced motion artifacts and environmental noise |

| Recording Cap | Electrode placement following 10-20 system, stretchable fabric | Standardized electrode positioning across subjects and studies |

| Conductive Gel | Electrolyte-chloride based, low impedance | Ensures stable electrical connection between scalp and electrodes |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Millisecond precision timing, synchronization capabilities | Precise control and timing of experimental paradigms |

| Electrode Impedance Checker | Real-time impedance monitoring | Ensures signal quality through proper electrode-skin contact |

| Electromyography (EMG) Sensors | Surface electrodes with bipolar configuration | Monitoring and subsequent removal of muscle artifacts |

| Electrooculography (EOG) Electrodes | Placement near ocular muscles | Detection and removal of eye movement and blink artifacts |

| Faraday Cage | Electrically shielded enclosure | Minimization of environmental electromagnetic interference |

| Data Analysis Suite | Digital filtering, ICA, time-frequency analysis | Comprehensive processing and statistical analysis of neural signals |

Applications and Research Implications

EEG's millisecond temporal precision makes it indispensable for investigating the rapid dynamics of cognitive processes, particularly in language research, attention studies, and clinical applications [18]. The N400 component, for instance, has been instrumental in understanding how the brain processes semantic information and integrates meaning across words, sentences, and discourse contexts [18].

In clinical neuroscience, EEG and ERPs provide sensitive measures of neural dysfunction in various disorders, including schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, and attention-deficit disorders [18]. The non-invasive nature and relatively low cost of EEG also make it suitable for large-scale studies, longitudinal monitoring, and bedside assessments in clinical populations [16].

Emerging applications in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) leverage EEG's real-time capabilities to create direct communication pathways between the brain and external devices [20]. These systems have shown promise for assistive technologies, neurorehabilitation, and augmentative communication, particularly for individuals with severe motor disabilities [20].

EEG remains an essential tool in the neuroimaging arsenal, providing unparalleled access to the brain's millisecond-scale electrical dynamics. While limited in spatial resolution compared to fMRI and fNIRS, its exceptional temporal resolution, relatively low cost, and flexibility make it ideally suited for investigating the rapid neural processes underlying cognition, perception, and action. The future of EEG lies in its integration with complementary neuroimaging modalities, enabling researchers to simultaneously capture both the when and where of brain activity, and ultimately leading to more comprehensive models of brain function in health and disease.

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a portable, non-invasive neuroimaging technology that uses low levels of non-ionizing light to record changes in cerebral blood flow in the brain through optical sensors placed on the scalp [4]. As an optical brain monitoring technique, fNIRS measures cortical hemodynamic responses—specifically, changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR)—that occur in response to neural activity [21]. This measurement is based on the mechanism of neurovascular coupling, where neural activation triggers a hemodynamic response that delivers oxygenated blood to active brain regions [22].

The fundamental principle behind fNIRS is that near-infrared light (650-900nm) can penetrate biological tissues, including the skull, and is absorbed by chromophores in the brain, primarily hemoglobin [4]. By measuring changes in light absorption at different wavelengths, fNIRS can quantify relative changes in HbO and HbR concentrations, providing an indirect measure of neural activity [22]. The technique is particularly valuable for studying the outer layers of the cortex, typically reaching depths of approximately 1-2.5 centimeters beneath the scalp [2] [21].

Technical Foundation and Signal Generation

Physical Principles of Light-Tissue Interaction

fNIRS leverages the relative transparency of biological tissues to near-infrared light and the differential absorption properties of hemoglobin species. Within the 650-900nm range, light can penetrate several centimeters through tissue, allowing measurement of cortical brain activity [4]. Biological tissue is highly scattering; on average, light in this region travels approximately 1/10 mm before scattering [4].

The core physical principle involves the modified Beer-Lambert law, which relates the attenuation of light to the concentration of absorbing compounds in a highly scattering medium like brain tissue [4] [22]. When light enters at a source position on the fNIRS head cap, it diffuses throughout the tissue, reaching down to approximately the outer 5-8mm of the brain cortex based on previous modeling studies [4]. This light is then collected as it exits the head beneath discrete detectors that carry light back to photon detectors on the fNIRS instrument [4].

Neurovascular Coupling and Hemodynamic Response

The fNIRS signal is fundamentally tied to the brain's hemodynamic response through neurovascular coupling. When a brain region becomes active, a complex cascade of processes leads to increased energy demands. All processes of neural signaling require energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), produced principally by mitochondria from glycolytic oxygenation of glucose [23].

During neural activation:

- Increased neural firing elevates the local cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) [23]

- Transient oxygen consumption causes a brief build-up of deoxygenated hemoglobin [23]

- Vasodilatory response occurs within 1-2 seconds, increasing local cerebral blood flow [23]

- Oversupply of oxygenated blood results in a net increase in HbO and decrease in HbR [23] [22]

This hemodynamic response unfolds over several seconds, creating the characteristic fNIRS signal pattern of increased HbO and decreased HbR concentrations in active brain regions [22].

Figure 1: Neurovascular Coupling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the cascade from neural activity to the measurable fNIRS signal through metabolic and vascular responses.

Comparative Analysis with fMRI and EEG

Technical Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of fNIRS against two other major non-invasive neuroimaging techniques: functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and Electroencephalography (EEG).

| Feature | fNIRS | fMRI | EEG |

|---|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Hemodynamic response (HbO/HbR) [2] [21] | Blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal [23] [24] | Electrical activity from cortical neurons [25] [21] |

| Signal Source | Changes in oxygenated/deoxygenated hemoglobin [21] | Changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentration [23] | Postsynaptic potentials in cortical neurons [25] [21] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (seconds) [2] [21] | Low (seconds) [23] [2] | High (milliseconds) [2] [21] |

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate (centimeter-level) [2] [21] | High (millimeter-level) [2] | Low (centimeter-level) [2] [21] |

| Depth of Measurement | Outer cortex (~1-2.5 cm) [4] [21] | Whole brain [23] [24] | Cortical surface [25] [21] |

| Portability | High [2] [21] | Low [2] | High [2] [21] |

| Motion Tolerance | Moderate to High [2] [21] | Low [23] | Low [2] [21] |

| Setup Complexity | Moderate [21] | High [23] | Moderate [21] |

| Cost | Moderate [2] | High [2] | Low to Moderate [2] [21] |

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

fNIRS Advantages: fNIRS offers a unique balance of portability, moderate spatial resolution, and reasonable motion tolerance, making it suitable for naturalistic study designs [2] [21]. Unlike fMRI, which requires a supine position in a confined scanner, fNIRS uses flexible fiber optic cables that allow neuroimaging experiments during standing, walking, or other ecological behaviors [4]. Compared to EEG, fNIRS provides superior spatial localization of cortical activity and is less susceptible to electrical artifacts from muscle movement or environmental noise [21].

fNIRS Limitations: The technique is limited to measuring cortical surfaces and cannot access subcortical structures [4] [21]. Its temporal resolution is constrained by the slow hemodynamic response (seconds) compared to the millisecond resolution of EEG [2] [21]. Spatial resolution remains inferior to fMRI, and the signal can be contaminated by physiological artifacts from scalp blood flow [22].

fMRI Advantages: fMRI provides whole-brain coverage with high spatial resolution, making it ideal for mapping distributed brain networks [23] [24]. The BOLD signal is well-validated and standardized across research centers.

EEG Advantages: EEG captures neural activity directly with millisecond temporal resolution, ideal for studying rapid cognitive processes, event-related potentials, and oscillatory brain dynamics [25] [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative fNIRS Experimental Protocol

A representative fNIRS study investigating vestibular function during balance tasks illustrates key methodological considerations [4]. This study used a 32-channel continuous wave fNIRS instrument with two wavelengths (690nm and 830nm) to record blood flow changes in frontal, motor, sensory, and temporal cortices during active balancing while playing a video game simulating downhill skiing [4].

Participants and Setup:

- Nine right-handed volunteers with no balance or mobility disorders [4]

- fNIRS head cap constructed from plastic materials and Velcro with 32 source-detector combinations at 3.2cm spacing [4]

- Prior to recording, the fNIRS probe position was registered on each subject's head using a 3D stylus for inter-subject data registration and image reconstruction [4]

Task Design:

- Participants stood on an instrumented balance board controlling a ski avatar in a video game [4]

- Experimental design included 30-second standing rest periods before and after each task trial [4]

- Task difficulty was manipulated (beginner vs. advanced levels) with timing self-paced by participants [4]

- Each subject performed 6 trials at beginner level and 8 trials at advanced level [4]

Control Condition:

- In three subjects, an additional control task was performed where the subject watched the video game but stood still [4]

- This controlled for visual stimulus effects unrelated to the balance task itself [4]

Figure 2: fNIRS Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in a representative fNIRS study investigating balance control.

Signal Processing and Data Analysis

fNIRS data processing typically involves multiple stages to extract meaningful hemodynamic responses from raw optical signals [26] [22]. The dynamic nature of the fNIRS signal incorporates several physiological components that must be accounted for during analysis:

Preprocessing Steps:

- Conversion of light attenuation to concentration changes using the modified Beer-Lambert law [4] [22]

- Motion artifact correction to address signal contamination from participant movement [22]

- Filtering to remove physiological noise (cardiac pulsation ~1Hz, respiration ~0.3Hz, Mayer waves ~0.1Hz) [26]

- Baseline correction to account for signal drift [22]

Hemodynamic Response Modeling: Advanced fNIRS analysis incorporates dynamic models that account for arterial pulsations, frequency drifts, reflected waves, the hemodynamic response function (HRF), Mayer waves, respiratory waves, and other very low-frequency components [26]. These models help validate signal processing algorithms and improve the interpretation of fNIRS data in both resting-state and task-based paradigms [26].

Statistical Analysis: Similar to fMRI, fNIRS data are often analyzed using general linear models (GLM) to test hypotheses about condition-specific differences in brain activation [23] [22]. Statistical parametric maps can be generated to localize significant hemodynamic responses to experimental tasks.

Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

Essential Materials for fNIRS Research

The table below details key equipment and materials required for conducting fNIRS research, based on methodologies from cited studies.

| Item | Function | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Instrument | Measures light attenuation and computes hemoglobin concentrations | 32-channel continuous wave system (e.g., CW6 Real-time system; TechEn Inc) [4] |

| Light Sources | Emits near-infrared light into tissue | Laser diodes or LEDs at multiple wavelengths (690nm, 830nm) [4] |

| Detectors | Captures light that has traveled through tissue | Photomultiplier tubes or avalanche photodiodes [4] |

| Optodes | Interface between instrument and scalp | Source and detector fibers placed on scalp with 3-5cm spacing [4] |

| Head Cap | Holds optodes in stable positions on scalp | Plastic materials with Velcro adjustments [4] |

| Registration System | Maps optode locations to brain anatomy | 3D digitizer (e.g., FastSCAN stylus; Polhemus) [4] |

| Calibration Materials | Verifies system performance before data collection | Phantom with known optical properties [4] |

Applications in Research and Clinical Contexts

Research Applications

fNIRS has been applied across diverse research domains leveraging its unique combination of portability and hemodynamic monitoring capabilities:

Motor Control and Balance Research: The representative study discussed previously demonstrates fNIRS application for measuring cortical activation during dynamic balance tasks, revealing activation of the superior temporal gyrus modulated by task difficulty [4].

Psychiatric Research: fNIRS shows growing relevance in psychiatry as a potential tool for monitoring neurofunctional changes related to treatment [22]. Studies have applied fNIRS to monitor treatment response across various psychiatric disorders including depression, schizophrenia, and ADHD [22].

Addiction Research: fNIRS serves as an elective tool to assess real-time neural activity with high ecological validity in addiction research, studying both substance and behavioral dependence [27].

Cognitive Neuroscience: fNIRS is widely used to study higher-order cognitive processes including attention, emotion regulation, and executive functions, particularly benefiting from its tolerance for some movement during measurements [21].

Clinical Applications

Surgical Planning: While less established than fMRI for surgical mapping, fNIRS has potential for identifying eloquent cortical areas to be preserved during neurosurgical procedures [24].

Neurorehabilitation: fNIRS shows promise for monitoring brain reorganization during recovery from stroke or brain injury, and for guiding rehabilitation protocols [4].

Treatment Monitoring: In psychiatric practice, fNIRS has been investigated for monitoring response to pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and neuromodulatory treatments [22].

Future Directions and Methodological Advancements

The future evolution of fNIRS technology and applications focuses on several key areas:

Methodological Standardization: Current research shows significant variability in fNIRS methodologies, with only 44.7% of studies reporting motion correction procedures and 53.2% not reporting activation direction [22]. Future work needs standardized protocols for design and reporting to enhance reproducibility [22].

High-Density Systems: Technological advances are increasing channel counts, with over half of recent studies using high-density (>32-channel) systems to improve spatial resolution and coverage [22].

Multimodal Integration: Combining fNIRS with EEG provides complementary information by capturing both hemodynamic and electrical neural activity simultaneously [21]. Integrated systems require careful synchronization and artifact management but deliver richer datasets [21].

Analytical Advancements: More sophisticated signal processing algorithms and dynamic models of brain hemodynamics continue to improve the accuracy and interpretability of fNIRS signals [26].

Clinical Translation: Efforts are underway to establish fNIRS as a validated biomarker for disease states and treatment response across neurological and psychiatric conditions [22].

Understanding the strengths and limitations of non-invasive neuroimaging technologies is crucial for designing robust neuroscience research and developing effective clinical applications. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) represent three prominent techniques that enable researchers to investigate brain function through different physiological windows. Each method captures distinct neural correlates with varying spatiotemporal resolutions, portability, and practical implementation requirements. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these modalities, framing their core principles within contemporary neuroscience research and drug development contexts. By synthesizing their fundamental measurement mechanisms, inherent technical constraints, and experimental considerations, this review aims to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select appropriate neuroimaging tools for specific investigative questions and clinical applications, particularly as multimodal approaches continue to advance the field [17] [28].

Physiological Origins of Measured Signals

Neuroimaging techniques capture brain activity through different physiological processes. fMRI measures neural activity indirectly via the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal, which reflects changes in blood oxygenation, flow, and volume associated with neuronal firing [17]. This hemodynamic response typically lags 4-6 seconds behind neural activity, with a sampling rate generally ranging from 0.33 to 2 Hz [17]. The BOLD effect originates from neurovascular coupling, where localized neural activity triggers increased cerebral blood flow that exceeds oxygen consumption, resulting in decreased deoxygenated hemoglobin in venous blood [17].

In contrast, EEG directly measures electrical potentials generated by synchronized postsynaptic activity of cortical pyramidal neurons [29]. These electrical signals are conducted through various tissues including cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp, where they are detected by electrodes placed on the scalp surface [29]. EEG provides exceptional temporal resolution at the millisecond level, enabling real-time tracking of neural dynamics [20] [29].

fNIRS operates on a similar hemodynamic principle as fMRI but uses near-infrared light (650-950 nm) to measure changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations in cortical surface vasculature [17] [30]. The technique leverages the "optical window" where biological tissues have relatively low absorption, allowing light to penetrate several centimeters to reach the cerebral cortex [30]. fNIRS signals are typically sampled at rates around 10 Hz, bridging the temporal gap between fMRI and EEG [31] [32].

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of core technical specifications across fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS.

| Feature | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Measurement Principle | Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) effect via magnetic susceptibility changes [17] | Electrical potentials from synchronized neuronal activity [29] | Hemodynamic responses via near-infrared light absorption [17] [30] |

| Primary Signal Source | Deoxygenated hemoglobin in venous blood [17] | Post-synaptic potentials of cortical pyramidal neurons [29] | Concentration changes of HbO and HbR in cortical vasculature [17] [30] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (0.33-2 Hz, limited by hemodynamic response latency of 4-6s) [17] | Very High (millisecond precision) [20] [29] | Moderate (seconds-level, typically ~11 Hz sampling) [31] [32] |

| Spatial Resolution | Very High (millimeter-level) [17] | Low (centimeter-level) [20] | Moderate (1-3 cm, superior to EEG) [17] [29] |

| Depth Penetration | Whole brain (cortical and subcortical) [17] | Cortical surface [29] | Superficial cortex (1-2.5 cm depth) [30] [29] |

| Direct vs. Indirect Neural Measure | Indirect (hemodynamic response) [17] | Direct (electrical activity) [29] | Indirect (hemodynamic response) [17] |

| Portability | Very Low (immobile scanner) [17] | High (wearable systems available) [33] [29] | High (portable/wearable formats) [17] [29] |

| Tolerance to Motion Artifacts | Low (highly sensitive to movement) [17] | Moderate (susceptible to movement, especially head/neck muscles) [33] [31] | High (relatively robust to movement) [29] [31] |

| Typical Experimental Environment | Controlled laboratory with magnetic shielding [17] | Controlled lab to semi-naturalistic settings [33] | Laboratory to fully naturalistic environments [17] [33] |

Inherent Limitations and Methodological Constraints

Technical and Physiological Limitations

Each neuroimaging modality presents distinct limitations that researchers must consider during experimental design. fMRI provides unparalleled spatial resolution for deep brain structures but suffers from several constraints including high cost, immobility, sensitivity to motion artifacts, and requirement for participants to remain motionless within the scanner environment [17]. These limitations impede studies involving naturalistic behaviors, children, or individuals with motor impairments [17]. Furthermore, the temporal resolution of fMRI is fundamentally constrained by the hemodynamic response latency [17].

EEG's primary limitations include low spatial resolution (approximately 2 cm) due to signal dispersion through skull and scalp tissues, and high susceptibility to various artifacts including ocular activity, head and neck muscle movements, and environmental noise [20] [33]. While advanced source localization techniques can improve spatial precision, EEG remains predominantly sensitive to synchronous activity of aligned pyramidal neurons in cortical surface regions [29].

fNIRS is confined to monitoring superficial cortical regions due to limited penetration depth of near-infrared light, making it unsuitable for investigating subcortical structures [17] [30]. Its spatial resolution (typically 1-3 centimeters) is lower than fMRI, restricting precise localization of brain activity [17]. Extracerebral factors such as scalp blood flow and hair can confound fNIRS measurements, while systemic physiological changes (cardiac, respiratory, blood pressure) can introduce signal contaminants that mimic neural activation patterns [33].

Practical Implementation Challenges

Practical considerations significantly influence modality selection. fMRI systems entail substantial capital investment, maintenance costs, and specialized facilities with magnetic shielding, limiting accessibility for many research institutions [17]. Participant exclusion criteria are more extensive for fMRI, including metal implants, certain medical devices, claustrophobia, and body size restrictions [17].

EEG setup complexity varies by system type, with traditional research-grade systems requiring electrode gel application and scalp preparation to ensure impedance reduction [29]. While dry electrode and wireless systems have improved usability, signal quality considerations often necessitate traditional wet electrode setups for high-quality data acquisition [33].

fNIRS systems generally involve moderate setup complexity with optode placement requiring minimal skin contact compared to EEG [29]. However, dark hair, pigmented skin, or optode movement can challenge signal quality [33]. The technology's relative novelty means standardized analysis pipelines and protocols are less established than for fMRI or EEG [30] [33].

Table 2: Methodological constraints and practical limitations across neuroimaging modalities.

| Constraint Type | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Burden | Very High (expensive equipment, maintenance, facilities) [17] | Generally Lower [29] | Generally Higher (especially high-density systems) [29] |

| Participant Exclusions | Extensive (metal implants, pacemakers, cochlear implants, claustrophobia) [17] [30] | Minimal (skin conditions) [30] | Minimal (primarily scalp conditions) [30] |