fMRI vs. EEG vs. fNIRS: A Neuroimaging Modality Guide for Cognitive Research and Drug Development

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) for researchers and professionals in neurocognition and drug development.

fMRI vs. EEG vs. fNIRS: A Neuroimaging Modality Guide for Cognitive Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) for researchers and professionals in neurocognition and drug development. It covers the foundational principles, spatial-temporal resolution, and physiological basis of each technique. The article details methodological applications across clinical and cognitive domains, explores troubleshooting and data optimization strategies, and offers a direct comparative analysis to guide modality selection. By synthesizing current evidence and multimodal trends, this resource aims to inform robust study design, enhance data interpretation, and accelerate translational research in neuroscience.

Core Principles and Technical Foundations of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

Modern neuroimaging relies on measuring signals that act as proxies for neuronal activity. The three primary signals are the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electrical potentials from electroencephalography (EEG), and hemodynamic signals from functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). The BOLD signal, a cornerstone of fMRI, is an indirect reflection of neuronal activity that measures changes in blood oxygenation [1]. It is primarily determined by the change in paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin, which results from the combination of changes in oxygen metabolism, cerebral blood flow, and cerebral blood volume [1] [2]. EEG, in contrast, directly measures the brain's electric fields through voltage potentials recorded on the scalp, reflecting the macroscopic activity of the brain surface [3] [4]. fNIRS occupies a middle ground, measuring hemodynamic changes by quantifying oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations using near-infrared light [5] [6]. Understanding the physiological origins, temporal and spatial characteristics, and relationships between these signals is fundamental to interpreting neuroimaging data and selecting the appropriate modality for specific research questions in cognitive neuroscience and drug development.

Physiological Origins and Mechanisms

The BOLD Signal in fMRI

The BOLD signal detected in fMRI reflects complex physiological processes coupled to underlying neuronal activity. It originates from changes in the magnetic properties of blood based on its oxygenation level. Deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) is paramagnetic, meaning it is attracted to an external magnetic field, while oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic and repelled from an applied magnetic field [6]. This difference creates magnetic field inhomogeneities that affect the MRI signal, with higher deoxyhemoglobin concentrations leading to signal reduction [2]. The classic positive BOLD response observed during functional activation represents a decrease in deoxyhemoglobin, indicating an overoxygenation of the active brain region [2]. This hyperoxygenation results from a localized increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) that exceeds the oxygen demands of the tissue, delivering oxygenated blood in surplus [2].

Neurovascular coupling is the active process linking neuronal activity to orchestrated increases in local blood flow [2]. This response begins rapidly (within ~500 ms of stimulus onset) but peaks 3-5 seconds later due to the physical limitations of vascular dilation and blood flow changes [2]. The BOLD signal is therefore an indirect and delayed measure of neuronal activity, influenced by multiple physiological variables including the efficiency of the hemodynamic response and unique properties of the neural circuit being studied [6]. Key temporal features of the BOLD response include the initial dip, the main positive response, and the post-stimulus undershoot, each reflecting different aspects of the underlying neurovascular and metabolic dynamics [1].

Electrical Potentials in EEG

Electroencephalography measures electrical potentials generated by the summed postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex [4]. When these neurons fire synchronously, their electrical fields summate enough to be detectable through the skull and scalp by electrodes. These signals offer a direct measurement of neural electrical activity with millisecond temporal resolution, allowing for real-time tracking of brain dynamics [3]. The EEG signal represents a macroscopic measure of the brain's surface electrical activity, capturing inherent and periodic electrical impulses generated by clusters of brain cells [3].

The electrical signals recorded by EEG are characterized by their complexity, susceptibility to noise, nonlinearity, and significant variation across individuals based on factors such as age, psychology, and testing environment [3]. Unlike hemodynamic methods, EEG provides a direct window into neural processing but with limited spatial resolution due to the blurring effect of the skull and scalp on electrical field propagation. The signal pattern obtained represents the spontaneous biological potential of the brain, which has been shown to reflect the macroscopic activity of the brain surface [3].

Hemodynamic Signals in fNIRS

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy measures hemodynamic changes associated with neural activity by exploiting the differential absorption properties of biological chromophores, primarily oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) [5] [6]. fNIRS relies on the relative transparency of biological tissues to near-infrared light (650-950 nm wavelengths) and the fact that HbO and HbR absorb this light differently [5]. By emitting light at specific wavelengths and measuring the intensity of light that reaches detectors placed on the scalp, fNIRS can quantify changes in hemoglobin concentrations in the cortical tissue beneath [7].

The hemodynamic response measured by fNIRS shares a common physiological origin with the BOLD signal, as both are governed by neurovascular coupling [8]. During neuronal activation, increased metabolic demands trigger changes in cerebral blood flow, volume, and oxygen consumption, altering the relative concentrations of HbO and HbR [5]. Typically, activation produces an increase in HbO and a decrease in HbR, similar to the oxygenation changes underlying the BOLD signal [7]. The fNIRS signal is contaminated by various physiological noises, including cardiac pulsation, respiratory cycles, and low-frequency Mayer waves, which must be accounted for in signal processing [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Neuroimaging Signals

| Property | BOLD (fMRI) | Electrical Potentials (EEG) | Hemodynamics (fNIRS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is Measured | Changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentration via magnetic susceptibility | Scalp voltage potentials from postsynaptic neuronal activity | Changes in HbO and HbR concentrations via light absorption |

| Physiological Basis | Neurovascular coupling; blood oxygenation | Direct neuronal electrical activity | Neurovascular coupling; blood volume and oxygenation |

| Primary Source | Hemodynamic response to neural activity | Synchronous firing of pyramidal neurons | Hemodynamic response to neural activity |

| Key Contributors | Cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, oxygen metabolism | Ion channel activity, synaptic transmission | Cerebral blood flow, blood volume, oxygen metabolism |

| Typical Temporal Resolution | 1-3 seconds | Milliseconds | 0.1-1 second |

| Typical Spatial Resolution | 1-3 mm (excellent) | 1-2 cm (poor) | 1-3 cm (moderate) |

| Depth Sensitivity | Whole brain | Cortical surface | Superficial cortex (1-3 cm) |

Measurement Principles and Methodologies

fMRI and BOLD Signal Acquisition

Functional MRI utilizing the BOLD contrast requires a high-field magnet (typically 1.5-7 Tesla) to create a strong static magnetic field [6]. When hydrogen protons in the brain are exposed to this field, they align with it. Application of radiofrequency pulses at specific frequencies displaces these protons, and as they return to equilibrium, they emit detectable signals [6]. The T2* relaxation rate, sensitive to local magnetic field inhomogeneities caused by deoxyhemoglobin, provides the contrast mechanism for detecting brain activation [2]. Active regions exhibit decreased deoxyhemoglobin, reduced magnetic field distortion, longer T2* relaxation, and higher signal intensity [6].

Experimental paradigms for fMRI typically involve block designs or event-related designs, with the BOLD response modeled using a hemodynamic response function (HRF) that captures its characteristic delay and shape [1]. The canonical HRF is often modeled as a linear combination of two Gamma functions to characterize the positive response and subsequent undershoot [5]. Advanced physiological models incorporate additional parameters to account for variations in response timing, dispersion, and baseline across different brain regions and subjects [1] [5].

EEG Signal Acquisition and Processing

EEG acquisition involves placing multiple electrodes (typically 16-256) on the scalp according to standardized systems like the 10-20 system [3]. These electrodes measure voltage fluctuations between recording sites and a reference electrode. Modern EEG systems can be categorized as invasive (with electrodes implanted directly into the brain) or non-invasive (with electrodes placed on the scalp surface), with non-invasive approaches being most common in human research [3]. Portable EEG systems have gained popularity recently, offering greater flexibility albeit sometimes with reduced signal quality compared to research-grade systems [3].

EEG signal processing follows a well-established pipeline [3] [9]:

- Preprocessing: Application of filters (high-pass to remove DC components, low-pass to remove high-frequency noise), artifact correction (especially for ocular movements), and often segmentation of data into epochs time-locked to events of interest.

- Feature Extraction: Transformation of signals into informative features using time-domain analysis (mean, standard deviation, entropy), frequency-domain analysis (Fourier transform, wavelets), or synchrony measures (coherence, correlation) between channels.

- Feature Selection: Optional step to identify the most relevant features using techniques like principal component analysis or genetic algorithms.

- Classification/Analysis: Application of statistical methods or machine learning classifiers to identify patterns related to cognitive states or experimental conditions.

fNIRS Signal Acquisition and Processing

fNIRS systems emit near-infrared light at specific wavelengths (typically 760 and 850 nm) through sources placed on the scalp and measure the intensity of light that reaches detectors at known distances (usually 3 cm) [5] [7]. The differential absorption at these wavelengths allows for calculation of changes in HbO and HbR concentrations using the modified Beer-Lambert law [5]. Systems can be continuous wave (measuring light intensity), frequency domain (measuring amplitude decay and phase shift), or time-resolved (measuring temporal point spread function), with continuous wave systems being most common due to their lower cost and complexity [5].

fNIRS processing typically involves [5] [7]:

- Conversion of raw intensity to optical density and then to hemoglobin concentration changes.

- Quality control using metrics like signal-to-noise ratio and scalp coupling index to identify and remove poor-quality channels.

- Filtering to remove physiological noise (cardiac, respiratory) and drift, often using bandpass filters (e.g., 0.02-0.08 Hz for resting-state studies).

- Artifact correction for motion and systemic physiological effects using methods like principal component analysis or targeted regression.

- Hemodynamic response modeling using general linear models with canonical response functions, sometimes with adaptive filtering techniques to account for inter-subject variations.

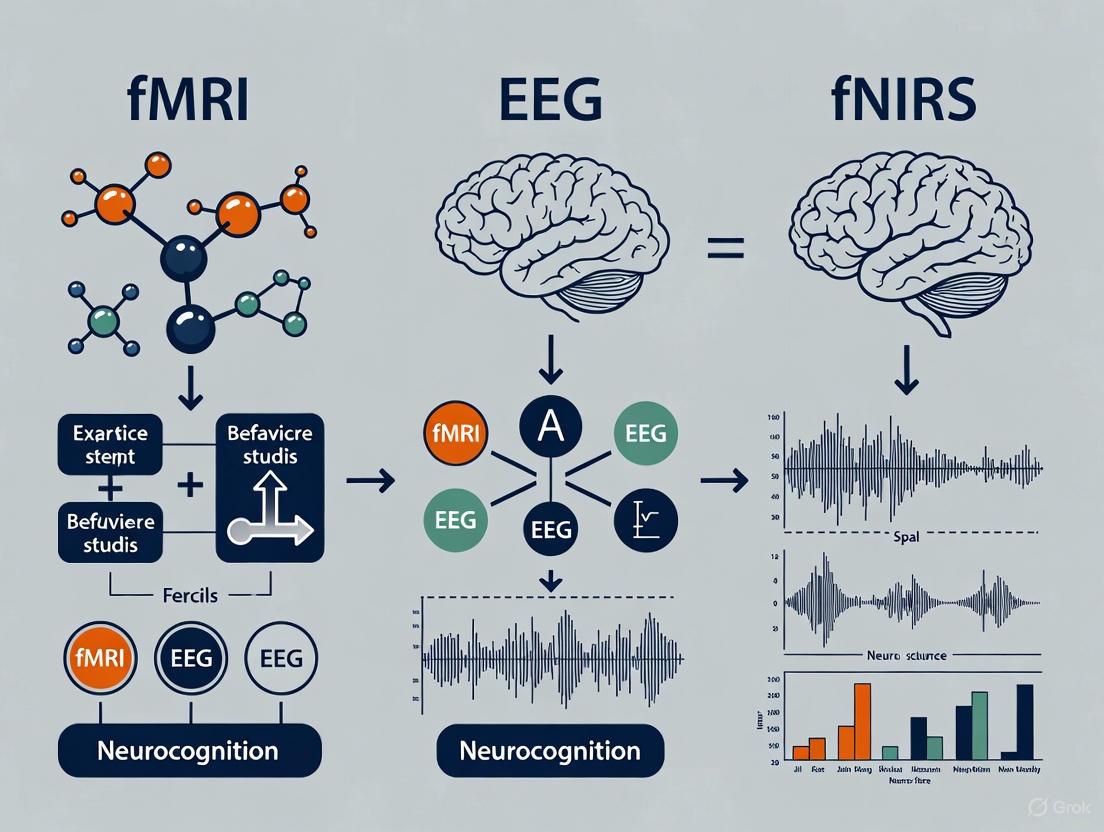

Figure 1: Signaling Pathways from Neuronal Activity to Measurable Signals. Solid lines represent hemodynamic pathways with slower temporal response; dashed line represents direct electrical measurement with millisecond resolution.

Comparative Analysis of Signals

Spatial and Temporal Characteristics

The three neuroimaging signals exhibit complementary strengths and limitations in their spatial and temporal characteristics. EEG provides excellent temporal resolution in the millisecond range, allowing precise tracking of neural dynamics as they unfold [3] [4]. However, its spatial resolution is limited (approximately 1-2 cm) due to the blurring effect of the skull and scalp on electrical field propagation [6]. In contrast, fMRI offers high spatial resolution (1-3 mm) and whole-brain coverage, enabling detailed localization of brain activity [6] [7]. This comes at the cost of poor temporal resolution (1-3 seconds) due to the slow nature of the hemodynamic response [2]. fNIRS occupies an intermediate position with moderate spatial resolution (1-3 cm) and better temporal resolution (0.1-1 second) than fMRI, but is limited to measuring superficial cortical regions [5] [7].

The BOLD signal's spatial specificity is influenced by the vascular architecture, with larger veins potentially draining blood from active areas and creating spatial mislocalization [2]. Recent high-resolution fMRI techniques have improved localization by focusing on the initial dip or capillary-level signals [1]. fNIRS signals originate from the cortical surface, with penetration depth limited to approximately 1-3 cm, restricting measurement to superficial cortex [7]. EEG sources can be localized to deeper structures using inverse modeling techniques, though with considerable uncertainty [3].

Relationship Between Signals

The relationship between electrical and hemodynamic signals is governed by neurovascular coupling—the process that links neuronal activity to subsequent changes in blood flow and oxygenation [2] [8]. Studies combining EEG and fMRI have demonstrated a correlation between electrical activity features (such as band power) and the BOLD signal, though this relationship varies across brain regions and frequency bands [8]. Similarly, simultaneous fNIRS-EEG studies show that hemodynamic changes generally follow electrical activity with a characteristic delay of several seconds [8].

The correspondence between fNIRS and fMRI signals has been systematically investigated. Research indicates that the fMRI BOLD signal shows the highest temporal correlation with fNIRS-measured deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR), as both are sensitive to deoxyhemoglobin concentrations [7]. However, some studies report similar correlations with oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) or total hemoglobin (HbT) [7]. A multimodal assessment of spatial correspondence found that all fNIRS chromophores (HbO, HbR, HbT) could identify motor-related activation clusters in fMRI data, with no statistically significant differences in spatial correspondence between them [7].

Table 2: Practical Comparison for Research Applications

| Characteristic | fMRI/BOLD | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 1-3 mm (High) | 1-2 cm (Low) | 1-3 cm (Moderate) |

| Temporal Resolution | 1-3 s (Slow) | <10 ms (Very Fast) | 0.1-1 s (Moderate) |

| Depth Penetration | Whole brain | Cortical, some deep sources | Superficial cortex (1-3 cm) |

| Portability | No (Scanner environment) | Yes (Portable systems available) | Yes (Highly portable) |

| Tolerance to Motion | Low (Requires head stabilization) | Moderate (Sensitive to muscle artifacts) | High (Tolerates some movement) |

| Physiological Noise Sources | Cardiac, respiratory, low-frequency drift | Ocular, muscle, cardiac, line noise | Cardiac, respiratory, Mayer waves, skin blood flow |

| Best Applications | Localization of function, connectivity mapping | Temporal dynamics of processing, event-related potentials, brain-computer interfaces | Ecological validity, clinical populations, long-term monitoring |

| Key Limitations | Expensive, scanner environment, low temporal resolution | Poor spatial resolution, sensitive to artifacts | Limited depth penetration, lower spatial resolution than fMRI |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Multimodal fMRI-fNIRS Motor Task Study

A representative experimental protocol for assessing spatial correspondence between fMRI and fNIRS hemodynamic responses involves asynchronous recording during motor tasks [7]:

Participants: 9 healthy volunteers with no neurological history (mean age 28.5 ± 3.3; 2 female).

Paradigm: Block design combining motor execution and imagery:

- 17 blocks total (9 Baseline, 4 Motor Action, 4 Motor Imagery)

- Block duration: 30 seconds

- Total run duration: 8 minutes 30 seconds

- During Motor Action blocks: Participants execute bilateral finger tapping sequence

- During Motor Imagery blocks: Participants imagine the same sequence without movement

fMRI Acquisition:

- 3T Siemens Magnetom TimTrio scanner with 12-channel head coil

- High-resolution MPRAGE structural sequence (176 slices, 1×1×1 mm voxels)

- EPI functional sequence (26 slices, 3×3 mm in-plane resolution, TR=1500 ms, TE=30 ms)

fNIRS Acquisition:

- NIRSport2 continuous wave system (16 sources, 15 detectors, 54 channels)

- Wavelengths: 760 nm and 850 nm

- Sampling rate: 5.08 Hz

- Intra-optode distance: 30 mm with 8 short-distance detectors (8 mm) for extracerebral signal regression

Analysis:

- fMRI preprocessing includes slice timing correction, motion correction, spatial smoothing (6 mm FWHM), and normalization to Talairach space.

- fNIRS processing includes quality control (SNR < 15 dB leads to channel pruning), conversion to optical density, motion correction, and bandpass filtering.

- General Linear Model analysis for both modalities with subject-specific regressors.

- ROI definition for primary motor and premotor cortices based on individual activation maps.

- Spatial correspondence assessment through overlap analysis of activation clusters.

Protocol for Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS Structure-Function Study

An investigation of structure-function relationships using simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recordings [8]:

Participants: 18 healthy subjects (28.5 ± 3.7 years) from open dataset.

Experimental Conditions:

- 1-minute resting state sessions

- 30 trials of 10-second left and right hand motor imagery tasks

EEG Acquisition:

- 30 electrodes according to international 10-5 system

- Sampling rate: 1000 Hz (downsampled to 200 Hz)

fNIRS Acquisition:

- 36 channels (14 sources, 16 detectors) with 30 mm inter-optode distance

- Standardized 10-20 system placement

- Sampling rate: 12.5 Hz (downsampled to 10 Hz)

- Wavelengths: 760 nm and 850 nm

Preprocessing:

- EEG: Filtering, artifact removal, source reconstruction using individual head models

- fNIRS: Optical density transformation, quality control (SCI < 0.7 leads to exclusion), bandpass filtering (0.02-0.08 Hz for resting state), motion artifact rejection using GVTD metric, physiological noise removal using PCA

Analysis Framework:

- Structural connectome from ARCHI database projected onto Desikan-Killiany atlas.

- Functional connectivity matrices computed for both EEG and fNIRS.

- Graph Signal Processing approach to quantify structure-function coupling.

- Structural-decoupling index calculation to measure regional (dis)alignment.

- Comparison across modalities, brain states, and intrinsic functional networks.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Multimodal Neuroimaging Studies. Common processing pipeline showing modality-specific steps for fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Field MRI Scanner | Generates BOLD contrast images through strong magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses | 3T Siemens Magnetom TimTrio with 12-channel head coil [7] |

| Continuous Wave fNIRS System | Measures hemodynamic changes via near-infrared light absorption | NIRSport2 (NIRx) with 760/850 nm wavelengths, 5.08 Hz sampling [7] |

| High-Density EEG System | Records electrical potentials from scalp with high temporal resolution | 30-electrode setup following 10-5 system, 1000 Hz sampling [8] |

| Structural Imaging Sequence | Provides high-resolution anatomical reference for functional data localization | MPRAGE sequence: 1×1×1 mm voxels, 176 slices [7] |

| Canonical Hemodynamic Response Function | Models expected BOLD/fNIRS response shape for statistical analysis | Two Gamma functions with 6 parameters (response/undershoot delays, dispersions, scaling, baseline) [5] |

| General Linear Model (GLM) Framework | Statistical framework for identifying task-related activation | Includes experimental paradigm, motion parameters, physiological noise regressors [5] [7] |

| Graph Signal Processing Tools | Analyzes structure-function relationships through network neuroscience approaches | Structural-decoupling index for quantifying regional coupling [8] |

| Short-Distance Detectors | Regresses superficial physiological noise in fNIRS signals | 8 mm separation optodes for measuring extracerebral signals [7] |

Understanding the physiological origins and characteristics of BOLD signals, electrical potentials, and hemodynamic responses is crucial for designing robust neuroimaging studies and accurately interpreting brain function. Each signal provides unique insights into brain activity with complementary strengths and limitations. The BOLD signal offers excellent spatial resolution but poor temporal characteristics, electrical potentials provide millisecond temporal resolution but limited spatial localization, and fNIRS hemodynamic signals balance portability and ecological validity with moderate spatiotemporal resolution. Multimodal approaches that combine these signals are increasingly valuable for advancing our understanding of brain function in both basic research and clinical applications. By leveraging their complementary strengths and accounting for their distinct physiological origins, researchers can develop more comprehensive models of brain function relevant to cognitive neuroscience and drug development.

Spatial resolution stands as a defining parameter in non-invasive neuroimaging, fundamentally shaping the scientific questions researchers can investigate and the clinical applications they can develop. The quest for higher spatial resolution drives technological innovation while simultaneously presenting unique methodological challenges that vary significantly across imaging modalities. In the context of comparing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), understanding spatial resolution extends beyond simple voxel size or electrode density to encompass the complex interplay between physiological signal origins, technological constraints, and analytical approaches. Each modality captures distinct facets of neural activity through different biophysical mechanisms, resulting in characteristic spatial resolution profiles that make them uniquely suited for specific research paradigms and clinical applications. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of spatial resolution across these three prominent neuroimaging techniques, examining how each modality bridges the gap from whole-brain mapping to precise cortical surface localization, with particular emphasis on their implications for neurocognitive research and drug development.

Fundamental Spatial Resolution Characteristics by Modality

The spatial resolution of neuroimaging techniques varies by orders of magnitude, directly influencing the scale of neural phenomena that can be reliably investigated. Table 1 provides a quantitative comparison of the core spatial resolution characteristics across fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS.

Table 1: Spatial Resolution Characteristics of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Parameter | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Spatial Resolution | 1-3 mm (7T); 3-3.5 mm (3T) [10] [11] | 5-9 mm (cortical source imaging) [12] | 1-3 cm [13] |

| Whole-Brain Coverage | Yes (standard) | Yes (with high-density systems) | Limited (superficial cortical regions) [13] |

| Penetration Depth | Full brain (cortical and subcortical) | Cortical, with volume conduction | Superficial cortex (2-3 cm) [13] [14] |

| Spatial Specificity to Neural Activity | High with high-resolution fMRI [11] | Moderate (limited by volume conduction) | Moderate (confounded by superficial hemodynamics) [13] |

| Primary Spatial Constraint | Signal-to-noise ratio, physiological noise [11] | Skull conductivity, inverse problem | Light scattering, absorption properties [14] |

The fundamental differences in spatial resolution stem from the distinct biophysical principles each modality exploits. fMRI measures blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals, reflecting hemodynamic changes coupled to neural activity through neurovascular coupling [11]. EEG captures post-synaptic electrical potentials generated by synchronized pyramidal neurons [15], while fNIRS employs near-infrared light to measure concentration changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in superficial cortical vessels [13] [14].

Technical Foundations of Spatial Resolution

fMRI: From Standard to High-Resolution Imaging

The spatial resolution of fMRI has dramatically improved with technological advances, particularly through the development of ultra-high field systems (7T and above). While "standard" fMRI resolution at 3T is typically defined as ~3-3.5 mm isotropic voxels, high-field systems enable "high resolution" (1-2 mm isotropic) and "ultra-high resolution" (better than 1 mm) imaging [10]. These advances are driven primarily by increased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) at higher field strengths [10].

The implementation of high-resolution fMRI presents significant technical challenges, including limited SNR, increased sensitivity to motion and distortion, and the need to maintain temporal resolution and whole-brain coverage [11]. Parallel imaging techniques with multi-channel radio frequency coils help mitigate these constraints by reducing acquisition times, with acceleration factors of R=4 readily achievable at 7T [10]. High-resolution fMRI begins to reveal the vascular and metabolic heterogeneity of the cortex, as relevant features (pial and intracortical vessels, cortical layers) become distinct at finer spatial scales [11]. This increased resolution necessitates more sophisticated BOLD models that incorporate additional compartments to account for laminar differences in neurovascular coupling and vascular architecture [11].

EEG: Source Imaging and the Inverse Problem

The spatial resolution of scalp EEG is substantially improved through cortical source imaging, which solves the inverse problem of estimating intracranial source activity from scalp potentials [12]. The accuracy of EEG source localization depends on multiple factors including sensor density, source localization algorithms, forward head models, and noise levels [12]. Validation studies comparing EEG source locations with fMRI activations in the primary visual cortex demonstrate mean localization errors of approximately 7 mm, sufficient to discriminate cortical activation changes corresponding to less than 3° visual field changes [12].

The spatial resolution of EEG is fundamentally constrained by the blurring effect of the skull and other tissues, which act as a volume conductor that spatially smears the intrinsically high-resolution neural electrical activity [15]. High-density EEG systems (128-256 channels) combined with realistic head models derived from structural MRI significantly improve spatial accuracy, but the technique remains limited in its ability to resolve deeply located sources or precisely distinguish adjacent neural populations with similar activation timecourses.

fNIRS: Physiological and Technical Constraints

fNIRS spatial resolution is primarily limited by light scattering in biological tissues, which causes measured signals to represent spatially blurred hemodynamic changes. The typical spatial resolution of 1-3 cm is sufficient to distinguish broad functional areas but inadequate for mapping columnar or laminar organization [13]. Depth sensitivity represents another major constraint, with near-infrared light penetration typically limited to the superficial cortex (2-3 cm depth), making fNIRS unsuitable for investigating subcortical structures [13] [14].

The spatial sampling of fNIRS is determined by the arrangement of sources and detectors on the scalp, with optimal separation typically around 3 cm to balance sensitivity to cerebral versus extracerebral signals [14]. Short-separation detectors (8 mm source-detector distance) are increasingly employed to measure and regress out superficial hemodynamic contributions, improving specificity to cerebral signals [14]. The modified Beer-Lambert law provides the fundamental principle for converting light attenuation measurements into hemoglobin concentration changes, though this approach yields relative rather than absolute quantification in continuous-wave systems [14].

Methodological Approaches for Enhanced Spatial Localization

Cortical Surface-Based Analysis of fMRI Data

Surface-based analysis represents a powerful approach for enhancing the functional specificity of fMRI data by leveraging anatomical constraints. This method involves interpolating fMRI data onto computational models of the cortical surface derived from high-resolution structural MRI [16]. The geodesic Voronoï diagram approach automatically defines interpolation kernels around each vertex of the cortical surface, following the highly convoluted anatomy of the cortex while avoiding mixing signals across sulci [16]. This method demonstrates greater robustness to anatomical/functional misregistration and position of vertices within the gray matter compared to spherical interpolation approaches [16].

Surface-based analysis provides several advantages for neuroimaging: (1) increased detection sensitivity by constraining analysis to cortical gray matter; (2) facilitation of intersubject alignment using cortical folding patterns; (3) enabling direct comparison with MEG/EEG source reconstruction performed on the same surface [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for high-resolution fMRI studies investigating laminar-specific processes or conducting multimodal integration with electrophysiological techniques.

Experimental Protocol: Cortical Surface-Based fMRI Analysis

Application Context: This protocol is designed for researchers seeking to implement cortical surface-based analysis of fMRI data to enhance spatial localization and facilitate multimodal integration, particularly with EEG/MEG.

Required Materials and Software:

- High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical MRI (1 mm isotropic)

- fMRI EPI volumes (standard resolution: 3-3.5 mm isotropic; high-resolution: 1-2 mm isotropic)

- Cortical surface extraction software (FreeSurfer, BrainVISA)

- fMRI processing pipeline (SPM, FSL, AFNI)

- Multimodal integration tools (Brainstorm, MNE-Python) [8] [16]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Anatomical Data Processing:

- Segment T1-weighted MRI to identify gray/white matter boundary

- Reconstruct cortical surface models (mid-thickness, pial, white surfaces)

- Apply surface inflation and spherical registration for intersubject alignment

fMRI Preprocessing:

- Perform standard volume-based preprocessing (motion correction, distortion correction, temporal filtering)

- Co-register functional volumes to anatomical data using boundary-based registration

Surface Interpolation:

- Define interpolation kernels using geodesic Voronoï diagrams around each surface vertex

- Project fMRI data (raw timeseries or statistical maps) onto surface vertices

- Verify interpolation quality and check for residual anatomical/functional misregistration

Surface-Based Analysis:

- Perform statistical analysis on surface-mapped data

- Apply surface-based spatial smoothing (typically 5-10 mm FWHM)

- Implement multiple comparison correction using random field theory or permutation testing

Multimodal Integration (Optional):

- Co-register EEG sensor positions to anatomical MRI

- Use same surface for EEG source reconstruction and fMRI visualization

- Compare spatial patterns of activation across modalities [16]

Validation and Quality Control:

- Compare surface-based results with standard volume-based analysis

- Verify that activation clusters respect sulcal boundaries

- Check for systematic biases in surface reconstruction across subjects

- Assess robustness to anatomical/functional misregistration [16]

Multimodal Integration for Enhanced Spatial Resolution

Complementary Strength Paradigms

Integrating multiple neuroimaging modalities leverages their complementary spatial and temporal resolution characteristics to overcome individual limitations. The combination of fMRI and fNIRS capitalizes on fMRI's high spatial resolution and whole-brain coverage with fNIRS's superior temporal resolution, portability, and lower motion sensitivity [13]. Similarly, simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording exploits EEG's millisecond temporal resolution for capturing neural dynamics alongside fNIRS's better spatial resolution and robustness to electrical noise [15].

Three primary methodological approaches exist for multimodal integration:

- EEG-informed fNIRS analysis: Using EEG-derived features to constrain or interpret fNIRS signals

- fNIRS-informed EEG analysis: Incorporating hemodynamic information to guide EEG source reconstruction

- Parallel fNIRS-EEG analyses: Analyzing datasets separately then combining results at the group level [15]

The theoretical foundation for EEG-fNIRS integration rests on neurovascular coupling - the physiological relationship between neural electrical activity and subsequent hemodynamic responses [15]. This coupling enables built-in validation of identified activity through simultaneous measurement of both processes, though with important considerations for their differential temporal and spatial characteristics.

Spatial Alignment and Co-registration Methods

Accurate spatial alignment between modalities is essential for meaningful multimodal integration. This typically involves:

- Coregistering EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes by spatially aligning them to an anatomical MRI template using digitized positions relative to known scalp landmarks [8]

- Mapping all functional data (EEG source reconstructions, fNIRS channels, fMRI activations) to a common coordinate system (e.g., Desikan-Killiany atlas) [8]

- Employing graph signal processing tools to analyze structure-function relationships across modalities within the same anatomical framework [8]

The Voronoï-based interpolation method previously described provides an optimal approach for projecting volumetric fMRI data to the cortical surface, creating a common spatial support for comparing fMRI results with EEG/MEG source reconstructions [16].

Visualization of Multimodal Integration Framework

Spatial Integration Framework for Multimodal Neuroimaging

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for High-Resolution Neuroimaging Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI Analysis Packages | SPM, FSL, AFNI, FreeSurfer | Preprocessing, statistical analysis, and cortical surface reconstruction of fMRI data |

| EEG Source Imaging Tools | Brainstorm, MNE-Python, FieldTrip | EEG forward modeling, source reconstruction, and connectivity analysis |

| fNIRS Processing Software | HOMER3, NIRS Toolbox, AtlasViewer | Optical data processing, hemoglobin calculation, and visualization on brain models [14] |

| Multimodal Integration Platforms | Brainstorm, SPM, AFNI | Co-registration of multimodal data and integrated analysis |

| High-Density EEG Systems | 128-256 channel EEG caps with active electrodes | High spatial sampling for improved source localization accuracy [12] |

| fNIRS Hardware Configurations | Continuous-wave (CW), frequency-domain (FD), time-domain (TD) systems | Measurement of hemodynamic responses with varying depth sensitivity and quantification capabilities [14] |

| Ultra-High Field MRI Scanners | 7T, 9.4T, and higher field systems | Enhanced SNR and spatial resolution for submillimeter fMRI [10] [11] |

| Head Model Resources | ICBM, Colin27, MNI templates | Standardized anatomical references for source reconstruction and spatial normalization |

Implications for Neurocognitive Research and Drug Development

The spatial resolution characteristics of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS have profound implications for their application in neurocognitive research and pharmaceutical development. In basic cognitive neuroscience, the choice of modality involves careful trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and experimental flexibility. fMRI provides unparalleled spatial specificity for mapping cognitive processes across distributed brain networks, while high-density EEG offers millisecond temporal resolution for tracking rapid neural dynamics. fNIRS occupies a unique niche with its balance of reasonable spatial sampling, good temporal resolution, and tolerance for movement, making it suitable for ecologically valid paradigms and special populations [13] [15].

In drug development, these modalities serve complementary roles in establishing target engagement, pharmacodynamic biomarkers, and mechanistic insights. fMRI provides detailed spatial information on drug effects across brain circuits, particularly valuable for compounds targeting specific neuroanatomical systems. EEG offers sensitive measures of neuronal population activity with temporal precision suited for capturing acute drug effects on neural oscillations and event-related potentials. fNIRS shows growing promise for clinical trials due to its practicality for repeated measurements, patient tolerance, and ability to monitor cortical responses during functional tasks in more naturalistic settings [15].

The emerging approach of multimodal integration holds particular promise for advancing both basic neuroscience and therapeutic development. By combining spatial precision from fMRI with temporal precision from EEG, researchers can achieve more comprehensive characterization of neural processes disrupted in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Similarly, combining fNIRS with EEG provides a portable platform for assessing both electrical and hemodynamic aspects of brain function in clinical populations and real-world environments [15] [8]. These integrated approaches potentially offer more sensitive biomarkers for tracking disease progression and treatment response, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for brain disorders.

Temporal resolution refers to the precision with which a neuroimaging technique can measure the timing of neural events. In cognitive neuroscience research, capturing the rapid dynamics of brain activity is essential for understanding how neural processes unfold in real time during task performance. The core challenge lies in balancing the capture of fast electrical events with the slower metabolic changes that accompany neural activity. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) approach this challenge differently, each with distinct advantages and limitations stemming from their fundamental operating principles [17] [18] [19].

These techniques measure different physiological phenomena: EEG directly detects electrical activity from neuronal firing, while fMRI and fNIRS measure hemodynamic responses (changes in blood flow and oxygenation) that are indirectly linked to neural activity through neurovascular coupling. This fundamental difference explains their vastly different temporal resolution characteristics, which in turn determines their suitability for various research questions in neurocognition and drug development [20].

Core Principles and Measurement Techniques

Electroencephalography (EEG): Capturing Electrical Potentials

EEG measures electrical activity generated by the synchronized firing of neuronal populations directly from the scalp surface. This technique captures voltage fluctuations resulting from ionic current flows within neurons, providing a direct window into the brain's electrical signaling with millisecond temporal resolution [19] [20]. This exceptional temporal sensitivity allows researchers to track neural events almost as they occur, making EEG ideal for studying rapid cognitive processes such as attention, perception, and decision-making. However, the electrical signals measured by EEG are distorted as they pass through the skull and scalp, resulting in limited spatial resolution on the order of centimeters [19] [21].

The quantitative analysis of EEG data typically involves examining power spectral density across different frequency bands: delta (0.5-4 Hz), theta (4-7 Hz), alpha (8-12 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), and gamma (30-150 Hz) [20]. These frequency-specific patterns provide valuable biomarkers for cognitive states and neurological conditions. In stroke recovery research, parameters like the Power Ratio Index (ratio of slow-wave to fast-wave activity) and Brain Symmetry Index have emerged as prognostic markers for motor recovery [20].

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): Tracking Blood Flow Changes

fMRI measures brain activity indirectly through the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast, which exploits different magnetic properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin [17]. When neurons become active, local blood flow increases disproportionately to oxygen consumption, leading to a decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin that serves as the basis for the BOLD signal. This hemodynamic response unfolds over several seconds, peaking typically 4-6 seconds after neural activity onset [17].

The BOLD response provides excellent spatial resolution (millimeters) and whole-brain coverage, including deep subcortical structures [17] [19]. However, this comes at the cost of poor temporal resolution (1-5 seconds) due to the slow nature of hemodynamic processes [19] [21]. This temporal lag means fMRI cannot capture rapid neural dynamics directly, though its high spatial precision makes it invaluable for localizing function and identifying networks. The technique requires expensive equipment, confines participants to a scanner environment, and is highly sensitive to motion artifacts [17].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS): Monitoring Hemodynamic Responses Optically

fNIRS operates on similar physiological principles as fMRI, measuring changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations in the brain [17] [18]. However, instead of magnetic properties, fNIRS utilizes the different absorption characteristics of hemoglobin to near-infrared light (650-1000 nm) [17]. When near-infrared light is projected through the scalp and skull, the intensity of diffusely refracted light provides information about relative hemoglobin concentration changes [18].

fNIRS occupies a middle ground temporally, with better temporal resolution than fMRI (typically 0.01-0.1 seconds or 10-100 Hz) but worse than EEG [18] [19]. This improved temporal sampling allows better characterization of the hemodynamic response function and greater tolerance for movement artifacts compared to fMRI [17] [22]. The spatial resolution of fNIRS is limited to superficial cortical regions (∼1-3 cm depth) due to rapid light scattering in biological tissue [18] [22]. Unlike fMRI, fNIRS does not provide structural anatomical information and requires co-registration with other imaging modalities for precise localization [17].

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Parameter | EEG | fNIRS | fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Milliseconds (0.001-0.005 s) [19] [21] | 10-100 Hz (0.01-0.1 s) [18] [19] | 1-5 seconds [19] [21] |

| Spatial Resolution | Centimeters (limited below cortical surface) [19] [21] | Millimeters (limited to cortical surface) [18] [21] | Millimeters (not limited to cortical areas) [19] [21] |

| Depth Penetration | Cortical surface | 1-3 cm (cortical regions only) [18] [22] | Whole brain including deep structures [17] |

| Measured Signal | Electrical activity from synchronized neuronal firing [20] | Hemodynamic response (HbO/HbR concentration changes) [17] [18] | Hemodynamic response (BOLD signal) [17] |

| Primary Strength | Excellent temporal resolution for tracking rapid neural dynamics [19] [20] | Good balance between temporal resolution and portability [17] [22] | Excellent spatial resolution and whole-brain coverage [17] [19] |

Quantitative Comparison of Temporal Resolution

The temporal characteristics of neuroimaging modalities directly determine the types of neural phenomena they can effectively capture. EEG's millisecond precision enables researchers to track the precise timing of cognitive processes, such as the sequence of neural events during visual perception or motor planning [20]. This fine temporal grain is essential for studying event-related potentials (ERPs) that unfold within hundreds of milliseconds after stimulus presentation.

In contrast, fMRI's temporal resolution of 1-5 seconds is sufficient to track general changes in brain activity across tasks but cannot resolve rapid neural sequences [19] [21]. The sluggish BOLD response integrates neural activity over time, making it difficult to determine whether activated areas are engaged simultaneously or sequentially. This limitation is particularly problematic for studying complex cognitive processes that involve rapidly switching between neural networks.

fNIRS offers an intermediate temporal solution with sampling rates typically between 10-100 Hz (0.01-0.1 seconds) [18] [19]. While still tracking the relatively slow hemodynamic response, this improved temporal sampling allows better characterization of the hemodynamic response function onset and shape compared to fMRI. The higher sampling rate also provides greater robustness to physiological noise and motion artifacts [22].

Table 2: Temporal Resolution Implications for Experimental Design

| Aspect | EEG | fNIRS | fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Study Types | Sensory processing, rapid cognitive tasks, sleep studies, epilepsy monitoring [20] | Naturalistic tasks, developmental studies, clinical populations, movement-based paradigms [17] [18] | Localization studies, network connectivity, deep brain structures, anatomical correlation [17] [19] |

| Temporal Constraints | Can resolve events separated by <100 ms | Can resolve events separated by 1-2 seconds | Requires 4-6 seconds between events for BOLD response |

| Neurovascular Coupling | Does not measure hemodynamic response | Directly measures hemodynamic response with better temporal sampling than fMRI | Measures hemodynamic response with delay of 4-6 seconds |

| Artifact Sensitivity | Sensitive to ocular, muscle, and electrical artifacts [19] | Moderately sensitive to motion artifacts [22] | Highly sensitive to motion artifacts [17] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multimodal fNIRS-EEG for Motor Tasks

A sophisticated approach to leveraging the complementary strengths of different temporal resolutions involves simultaneous multimodal recordings. A 2023 study published in Scientific Reports demonstrated this through simultaneous fNIRS-EEG recordings during motor execution, observation, and imagery tasks [23].

Experimental Setup: Participants were fitted with a 24-channel continuous-wave fNIRS system (Hitachi ETG-4100) embedded within a 128-electrode EEG cap (Electrical Geodesic, Inc.) [23]. The fNIRS system measured changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentration at two wavelengths (695 nm and 830 nm) with a sampling rate of 10 Hz. EEG data was collected simultaneously with millisecond temporal resolution. Optodes were positioned over sensorimotor and parietal cortices to target the Action Observation Network [23].

Task Design: The experiment included three conditions: (i) Motor Execution - participants grasped and moved a cup with their right hand; (ii) Motor Observation - participants observed an experimenter performing the same action; (iii) Motor Imagery - participants mentally rehearsed the action without physical movement [23]. Each condition was triggered by audio cues with randomized trial sequences.

Data Fusion and Analysis: Researchers employed structured sparse multiset Canonical Correlation Analysis (ssmCCA) to fuse fNIRS and EEG data, identifying brain regions consistently detected by both modalities [23]. This multimodal approach revealed activation in the left inferior parietal lobe, superior marginal gyrus, and post-central gyrus across all three conditions - findings that were not fully apparent in unimodal analyses.

Protocol 2: fNIRS for Postural Change Studies

fNIRS's tolerance to motion artifacts makes it particularly suitable for studying brain dynamics during physical movement. A systematic review published in Physiology & Behavior in 2024 detailed methodologies for investigating cerebral hemodynamics during postural changes [22].

Experimental Design: Studies typically involve participants changing position from supine or sitting to standing while fNIRS monitors cerebral oxygenation changes in parallel with continuous blood pressure monitoring [22]. This design allows researchers to investigate cerebral autoregulation - the brain's ability to maintain stable blood flow despite blood pressure fluctuations.

fNIRS Configuration: Most studies used continuous-wave fNIRS systems with source-detector distances of 3-4 cm, providing penetration depth of approximately 2-3 cm into the cerebral cortex [22]. Measurements focused on prefrontal and motor cortices, analyzing HbO and HbR concentration changes relative to baseline.

Data Interpretation: The review found that 58% of studies reported a positive correlation between brain oxygenation changes and blood pressure changes following postural changes, while 39% found no correlation [22]. These variable findings highlight the complexity of neurovascular coupling and the importance of standardized protocols for comparing results across studies.

Technical Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The fundamental relationship between neural activity and its measurable manifestations follows a predictable temporal sequence. The diagram below illustrates the complete signaling pathway from initial neural firing to the detectable signals measured by each neuroimaging technique:

The experimental workflow for designing studies that account for these temporal characteristics follows a structured process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Implementing temporally-sensitive neuroimaging research requires specific technical equipment and analytical tools. The following table details essential solutions for researchers designing experiments focused on temporal dynamics:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Temporal Neuroimaging

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Systems | Hitachi ETG-4100 [23], NIRSIT [24], Kernel Flow [19] | Measures hemodynamic responses with better temporal sampling than fMRI; suitable for naturalistic tasks and movement paradigms [17] [24] |

| EEG Systems | High-density 128-channel EEG [23], Quantitative EEG (qEEG) platforms [20] | Captures millisecond electrical activity; enables analysis of event-related potentials and neural oscillations [19] [20] |

| Multimodal Integration Tools | Structured sparse multiset CCA (ssmCCA) [23], Integrated fNIRS-EEG source localization [20] | Fuses data from multiple modalities to leverage complementary temporal and spatial resolution [20] [23] |

| Temporal Analysis Software | Brain Symmetry Index calculators [20], Hemodynamic response function modeling tools [17] | Quantifies temporal characteristics of neural signals; identifies abnormalities in neural timing and coordination [17] [20] |

| Experimental Paradigms | Motor execution/observation/imagery tasks [23], Postural change protocols [22] | Creates controlled conditions for studying temporal dynamics of specific cognitive and motor processes [22] [23] |

Temporal resolution represents a fundamental consideration in selecting neuroimaging modalities for neurocognitive research and drug development. EEG provides unparalleled millisecond precision for tracking rapid neural dynamics but offers limited spatial resolution. fMRI delivers detailed spatial mapping of brain activity but suffers from poor temporal resolution due to the slow hemodynamic response. fNIRS occupies a middle ground with better temporal sampling than fMRI while maintaining good tolerance for movement and naturalistic environments.

The future of temporal resolution in neuroimaging lies in multimodal approaches that simultaneously leverage the complementary strengths of different techniques. By combining EEG's millisecond precision with fNIRS's hemodynamic monitoring or fMRI's spatial resolution, researchers can overcome the limitations of individual modalities. These integrated approaches, supported by advanced data fusion algorithms, will continue to advance our understanding of brain dynamics across temporal scales from milliseconds to seconds - ultimately enhancing both basic cognitive neuroscience and applied clinical research.

This technical guide provides a detailed comparison of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) across the critical dimensions of portability, cost, and operational complexity. These specifications are pivotal for selecting the appropriate neuroimaging tool in neurocognitive research and drug development.

The table below synthesizes the core technical specifications for fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS to facilitate direct comparison.

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications for fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

| Specification | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portability & Tolerance to Motion | Non-portable; requires strict head immobilization in a scanner [13] [25]. | High portability; lightweight, wearable wireless systems available [26] [27]. Tolerant to some motion, but susceptible to artifacts from muscle and eye movement [27]. | High portability; wearable, wireless formats ideal for real-world settings [25] [27]. Highly tolerant to subject movement [27]. |

| Spatial Resolution | High (millimeter-level); whole-brain coverage, including subcortical structures [13]. | Low (centimeter-level); limited by skull conductivity and signal dispersion [26] [27]. | Moderate; better than EEG but confined to the cortical surface (up to ~2-2.5 cm depth) [13] [25] [27]. |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (seconds); constrained by the slow hemodynamic response (0.33-2 Hz) [13]. | Very High (milliseconds); ideal for tracking fast neural dynamics [26] [27]. | Low (seconds); also limited by the hemodynamic response [13] [27]. |

| Operational Complexity & Key Hardware | Very High; requires a shielded room, superconducting magnet, high-performance gradients, and dedicated RF coils. Needs specialist operation [28]. | Moderate; requires electrode application (gel or dry), amplifiers, and a data acquisition system. Setup is straightforward [27]. | Moderate; requires optode placement on the scalp with minimal skin preparation. Systems are generally user-friendly [27]. |

| Approximate Cost | Very High (millions of USD); includes high purchase price, installation, and maintenance. | Low to Moderate; generally lower cost, with consumer-grade devices becoming very affordable [27]. | Moderate; generally higher than EEG, especially for high-density systems [27]. |

Core Operational Principles and Experimental Workflows

Fundamental Operational Principles

Each technique measures a distinct physiological correlate of brain activity, which dictates its specifications and applications.

- fMRI: Measures changes in blood oxygenation (BOLD signal) related to neural activity [13] [28]. This requires a powerful magnet to detect subtle magnetic property changes in blood.

- EEG: Measures the electrical potential generated by the synchronized firing of populations of cortical neurons [26] [27].

- fNIRS: Uses near-infrared light to measure changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations in the superficial cortex, providing an indirect measure of neural activity via neurovascular coupling [13] [25].

The diagram below illustrates the core operational principles and the physiological signals each modality captures.

Figure 1: Signal pathways for EEG, fNIRS, and fMRI.

Representative Experimental Protocol: A Multimodal fNIRS-EEG Study

Combining modalities like fNIRS and EEG leverages their complementary strengths. The following is a generalized protocol for a simultaneous fNIRS-EEG experiment, such as one investigating a motor imagery task [8] [29].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Integrated fNIRS-EEG Cap | A helmet or cap with pre-defined openings and holders to co-register EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes, ensuring precise spatial alignment [26]. |

| fNIRS System | Emits near-infrared light and detects returning light to calculate HbO and HbR concentration changes [13] [25]. |

| EEG System | Amplifies and records electrical potentials from the scalp via electrodes [26] [27]. |

| Synchronization Hardware/Software | A shared clock or trigger system (e.g., TTL pulses) to temporally align fNIRS and EEG data streams with millisecond precision [26] [29]. |

| Task Presentation Software | Presents visual or auditory cues to the participant to elicit specific brain states (e.g., rest vs. motor imagery) [25]. |

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation & Setup: Fit the participant with the integrated fNIRS-EEG cap according to the international 10-20 system for positioning. For EEG, ensure good electrode-scalp contact using electrolyte gel or with dry electrodes. For fNIRS, ensure optodes have firm but comfortable contact with the scalp [26] [27].

- Hardware Synchronization: Initiate both the fNIRS and EEG systems and establish a synchronization protocol (e.g., via a shared trigger from the task presentation computer) to ensure temporal alignment of the acquired data [26] [29].

- Data Acquisition:

- Record a baseline period (e.g., 1-minute resting state) [8].

- Present the task paradigm. For a motor imagery task, this involves cueing the participant to imagine moving their left or right hand without actual movement for a set period (e.g., 10 seconds), interspersed with rest periods [8].

- Acquire data simultaneously from both fNIRS and EEG throughout the session.

- Data Preprocessing:

- EEG: Apply filters (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz), remove artifacts (e.g., ocular, muscle), and re-reference the data [8].

- fNIRS: Convert raw light intensity to optical density, then to HbO and HbR concentrations. Apply bandpass filtering (e.g., 0.01-0.1 Hz) to remove physiological noise (heart rate, respiration) and motion artifacts [8].

- Data Fusion & Analysis: Employ analysis techniques such as:

- General Linear Model (GLM): Model the brain response to the task conditions for each modality separately [25].

- Data-Driven Fusion: Use methods like joint Independent Component Analysis (jICA) or canonical correlation analysis (CCA) to identify coupled patterns of electrical and hemodynamic activity [29].

The workflow for this type of experiment is summarized below.

Figure 2: fNIRS-EEG experimental workflow.

Interpretation Guidelines and Strategic Selection

Matching the Tool to the Research Question

The choice of neuroimaging modality should be driven by the specific requirements of the research question.

- Choose EEG when the primary interest is in the timing of neural processes with millisecond precision. It is ideal for studying event-related potentials (ERPs), rapid cognitive processes, and for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) where speed is critical [27].

- Choose fNIRS when the research requires localization of cortical activity in naturalistic or mobile settings. Its tolerance to motion makes it suitable for studies involving social interaction, rehabilitation exercises, or child development [13] [25] [27].

- Choose fMRI when the highest possible spatial resolution and whole-brain coverage are non-negotiable. It is indispensable for mapping deep brain structures and establishing detailed functional networks in highly controlled environments [13] [28].

- Choose a Multimodal Approach (e.g., fNIRS-EEG) when a comprehensive picture of brain activity is needed, combining excellent temporal resolution with good spatial localization for cortical processes. This is highly valuable for advanced BCI and investigating neurovascular coupling [26] [29].

Operational and Cost Considerations

Strategic decision-making must also account for practical constraints.

- fMRI entails the highest operational complexity and cost, limiting its use for large-scale studies or longitudinal monitoring outside dedicated facilities.

- EEG and fNIRS offer lower barriers to entry in terms of cost and operational demands. Their portability enables longitudinal studies, fieldwork, and clinical bedside monitoring, which is challenging with fMRI [27].

- Integration Challenges: While combining EEG and fNIRS is powerful, it introduces challenges such as hardware compatibility, avoiding sensor interference on the scalp, and developing complex data fusion pipelines [26] [29].

Inherent Strengths and Limitations of Each Modality

Understanding the intricate functions of the human brain requires multimodal neuroimaging approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of individual techniques. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) represent three cornerstone modalities in contemporary neuroscience research, each with distinct technical principles and performance characteristics [13] [15]. These differences translate into specific advantages and limitations that determine their suitability for various research scenarios, particularly in drug development and clinical neuroscience applications. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these modalities, detailing their inherent strengths and limitations to inform experimental design and methodology selection in neurocognition research.

Technical Specifications and Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Core technical characteristics of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

| Parameter | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 1-3 mm (high) [13] | ~Centimeters (low) [15] [30] | 1-3 cm (moderate) [13] |

| Temporal Resolution | 0.33-2 Hz (slow) [13] | Millisecond-scale (very high) [15] | Up to 10+ Hz (moderate) [31] |

| Penetration Depth | Whole brain (high) [13] | Cortical surfaces (high) [15] | Superficial cortex (2-3 cm) (limited) [13] [17] |

| Portability | No (stationary) [13] [17] | Yes (high) [15] [17] | Yes (high) [13] [17] |

| Measurement Basis | BOLD signal (HbR) [13] [17] | Electrical potentials [15] | HbO and HbR concentrations [13] [15] |

| Key Measured Signal | Hemodynamic (indirect) [13] | Neuroelectrical (direct) [15] | Hemodynamic (indirect) [13] |

Table 2: Practical considerations for research implementation

| Consideration | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Very high [17] | Low [15] [17] | Moderate [17] |

| Setup Time | Lengthy [17] | Moderate [17] | Quick [17] |

| Subject Tolerance | Low (claustrophobia, noise) [13] [17] | High [17] | High [13] [17] |

| Motion Artifact Sensitivity | Very high [13] [17] | High [15] | Moderate [13] [15] |

| Population Suitability | Limited (metal implants, obesity) [17] | Broad (all populations) [17] | Broad (including infants) [13] [17] |

| Naturalistic Paradigm Suitability | Very low [13] | Moderate [15] | High [13] [31] |

Detailed Strengths and Limitations

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

Strengths:

- High Spatial Resolution: fMRI provides unparalleled spatial resolution (1-3 mm) for localizing neural activity across the entire brain, including deep subcortical structures such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus [13]. This whole-brain coverage enables comprehensive investigation of network interactions [13].

- Established Gold Standard: As a well-validated technique, fMRI serves as the reference modality for hemodynamic measurement, with extensive standardized protocols and analytical pipelines [17].

Limitations:

- Poor Temporal Resolution: The hemodynamic response measured by fMRI lags behind neural activity by 4-6 seconds, with a typical sampling rate of 0.33-2 Hz, making it unsuitable for capturing rapid neural dynamics [13].

- Restricted Experimental Environment: The requirement for subjects to remain motionless within the scanner confines research to highly controlled laboratory settings, limiting ecological validity [13] [17].

- Exclusion Criteria and Participant Burden: The strong magnetic field excludes participants with metal implants, and the loud, confined environment can cause discomfort, making it challenging for certain populations (e.g., children, claustrophobic individuals) [17].

Electroencephalography (EEG)

Strengths:

- Excellent Temporal Resolution: EEG captures neuroelectrical activity directly with millisecond precision, enabling the study of fast neural oscillations, event-related potentials, and real-time brain dynamics [15] [20].

- High Portability and Cost-Effectiveness: Modern EEG systems are lightweight, portable, and relatively affordable, facilitating research in diverse settings including clinical environments and naturalistic contexts [15] [17].

- Broad Population Applicability: With no exclusion criteria related to metal implants and better tolerance by participants, EEG can be used with virtually any population, including infants and patients with medical devices [17].

Limitations:

- Poor Spatial Resolution: The blurring effect of the skull and scalp on electrical signals results in spatial resolution on the centimeter scale, making precise source localization challenging without advanced inverse modeling techniques [15] [30].

- Vulnerability to Artifacts: EEG signals are highly susceptible to contamination from muscle activity, eye movements, and other physiological sources, requiring sophisticated preprocessing and artifact removal methods [15].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Strengths:

- Optimal Balance for Ecological Applications: fNIRS offers a favorable trade-off between spatial resolution (1-3 cm) and temporal resolution (typically ~10 Hz), along with robustness to motion artifacts, making it ideal for studying brain function in real-world contexts and during movement [13] [31] [17].

- Portability and Participant Flexibility: fNIRS systems are increasingly portable and wireless, allowing measurements at bedside, in homes, or during rehabilitation exercises [13] [31]. The silent operation prevents auditory interference with tasks [17].

- Comprehensive Hemodynamic Measurement: Unlike fMRI which primarily measures the BOLD signal (related to deoxygenated hemoglobin), fNIRS quantifies both oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated (HbR) hemoglobin concentration changes, providing a more complete picture of hemodynamic activity [31] [17].

Limitations:

- Superficial Measurement Depth: Near-infrared light penetration is limited to approximately 2-3 cm, restricting measurement to the cortical surface and preventing assessment of subcortical structures [13] [17].

- Lower Spatial Resolution Than fMRI: While offering better spatial resolution than EEG, fNIRS cannot match the precise localization capabilities of fMRI [13] [17].

- Sensitivity to Extracerebral Contamination: fNIRS signals can be confounded by systemic physiological noise from scalp blood flow, requiring careful signal processing to isolate brain-specific activity [13] [31].

Multimodal Integration Approaches

Integrating multiple neuroimaging modalities leverages their complementary strengths to overcome individual limitations. The synergy between fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS enables more comprehensive investigation of brain function through advanced data fusion techniques.

Figure 1: Signaling pathways and multimodal integration of EEG, fNIRS, and fMRI. The diagram illustrates how different modalities capture distinct aspects of neural activity and how their integration enables comprehensive brain mapping.

Methodological Frameworks for Integration

Synchronous Data Acquisition: Simultaneous recording of multiple modalities during experimental tasks requires careful technical coordination to minimize interference. For EEG-fMRI integration, specialized equipment resistant to electromagnetic interference is essential [13]. Similarly, combined EEG-fNIRS systems leverage their compatibility to capture complementary electrical and hemodynamic information concurrently [15] [32].

Asynchronous Data Integration: Data collected separately can be combined through spatial co-registration and analytical fusion techniques. This approach is particularly valuable when technical constraints prevent simultaneous acquisition, such as combining high-resolution fMRI with portable fNIRS for longitudinal monitoring [13].

Joint Source Reconstruction: Advanced computational algorithms utilize the spatial precision of hemodynamic modalities (fMRI or fNIRS) to constrain the inverse problem in EEG source localization. This approach significantly enhances the spatiotemporal resolution of neural activity mapping beyond what any single modality can achieve [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Multimodal fNIRS-EEG in Motor Recovery Assessment

This protocol exemplifies a multimodal approach for assessing post-stroke motor function recovery, combining the temporal precision of EEG with the hemodynamic monitoring capabilities of fNIRS [20].

Participant Preparation and Setup:

- EEG Cap Placement: Apply a 30-electrode cap according to the international 10-5 system, ensuring impedance levels below 5 kΩ for optimal signal quality [8].

- fNIRS Optode Configuration: Position fNIRS sources and detectors to cover motor cortical areas (primary motor cortex, supplementary motor area) with an inter-optode distance of 30 mm to ensure adequate penetration depth [20] [8].

- 3D Digitization: Record the precise positions of EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes relative to cranial landmarks (nasion, inion, preauricular points) for accurate spatial coregistration [8].

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- EEG: Sample at 1000 Hz with a bandpass filter of 0.1-100 Hz [8].

- fNIRS: Use wavelengths of 760 nm and 850 nm, sampling at 12.5 Hz [8].

- Task Paradigm: Implement a block design with alternating rest (30s) and motor execution/imagery (30s) epochs, repeated for 10 cycles [20].

Data Processing Pipeline:

- EEG Processing:

- Apply bandpass filtering (0.5-45 Hz) and notch filtering (60 Hz)

- Remove ocular and muscular artifacts using independent component analysis (ICA)

- Compute quantitative EEG (qEEG) parameters: Power Spectral Density (PSD), Brain Symmetry Index (BSI), and Phase Synchrony Index [20]

fNIRS Processing:

Multimodal Integration:

- Extract task-related hemodynamic responses from fNIRS and event-related synchronization/desynchronization from EEG

- Perform correlation analysis between EEG power bands and fNIRS hemoglobin concentrations to assess neurovascular coupling [20]

Protocol for fNIRS-fMRI Validation Studies

This protocol describes methodology for validating fNIRS measurements against the gold standard of fMRI, particularly for localizing activation in specific regions of interest [13] [17].

Experimental Design:

- Task Selection: Implement block-design motor tasks (e.g., finger tapping) or cognitive paradigms known to reliably activate target regions (e.g., supplementary motor area) [17].

- Simultaneous Acquisition: Collect fMRI and fNIRS data concurrently during task performance, ensuring fNIRS optodes are MRI-compatible and properly positioned within the scanner environment [13].

- Motion Minimization: Implement strict head restraint procedures to minimize movement artifacts in both modalities [13].

Data Analysis and Correlation:

- fMRI Processing: Preprocess BOLD data (motion correction, spatial normalization, smoothing) and generate statistical parametric maps of activation [13].

- fNIRS Analysis: Process hemodynamic signals and reconstruct cortical activation maps using anatomical co-registration [13].

- Spatial Correspondence Assessment: Quantify the spatial overlap between fMRI and fNIRS activation foci using dice coefficients or correlation metrics [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential materials and solutions for multimodal neuroimaging research

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MRI-Compatible EEG System | Records neural electrical activity within MRI scanner environment. | Essential for simultaneous EEG-fMRI; requires specialized electrodes and amplification systems resistant to electromagnetic interference [13]. |

| MRI-Compatible fNIRS System | Measures hemodynamic responses during fMRI acquisition. | Utilizes fiber-optic cables and non-magnetic components; enables direct correlation of fNIRS and BOLD signals [13]. |

| Conductive EEG Gel | Ensures optimal electrical conductivity between scalp and electrodes. | Reduces impedance for high-quality signal acquisition; choice between wet or saline-based gels depends on recording duration [20]. |

| fNIRS Optode Holders | Secures optical sources and detectors in precise configurations on scalp. | Customizable arrangements target specific cortical regions; compatible with EEG caps for multimodal studies [31] [8]. |

| 3D Digitizer | Records precise spatial coordinates of EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes. | Critical for accurate anatomical co-registration; enables mapping measurements to standard brain atlas spaces [8]. |

| Structural MRI Scan | Provides individual anatomical reference for source localization. | T1-weighted images facilitate precise mapping of functional data to brain anatomy; essential for EEG and fNIRS source reconstruction [30] [8]. |

Figure 2: Experimental design decision workflow for modality selection. This diagram provides a logical framework for choosing the most appropriate neuroimaging modality based on specific research requirements.

fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS each offer unique capabilities for investigating brain function, with inherent trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, portability, and practical implementation. fMRI remains unparalleled for precise spatial localization of deep brain activity, while EEG excels at capturing millisecond-scale neural dynamics. fNIRS provides an optimal balance for studying cortical function in naturalistic environments. The future of neurocognitive research lies in multimodal approaches that strategically combine these techniques to overcome their individual limitations, ultimately providing more comprehensive insights into brain function in health and disease. For drug development professionals, understanding these complementary strengths enables more informed decisions when designing studies to evaluate neurotherapeutic efficacy across different temporal and spatial scales of brain activity.

Selecting the Right Tool: Application-Based Methodology in Research and Clinics

Ideal Use Cases for Each Modality in Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience

Cognitive and clinical neuroscience relies on a suite of non-invasive neuroimaging techniques to decipher the relationship between brain function, cognition, and behavior. No single modality perfectly captures the brain's intricate dynamics; each offers a unique lens with specific strengths and limitations. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) are three pivotal technologies that form the backbone of modern brain research [33] [34] [35]. Understanding their ideal use cases is paramount for designing robust experiments, interpreting findings accurately, and advancing both fundamental knowledge and clinical applications. This guide provides a technical comparison of these modalities, detailing their core principles, optimal applications, and experimental protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Technical Specifications and Core Principles

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities