fNIRS vs EEG for Prefrontal Cortex Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Scientists and Clinicians

This article provides a definitive comparison of functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) and Electroencephalography (EEG) for studying the prefrontal cortex (PFC), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

fNIRS vs EEG for Prefrontal Cortex Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Scientists and Clinicians

Abstract

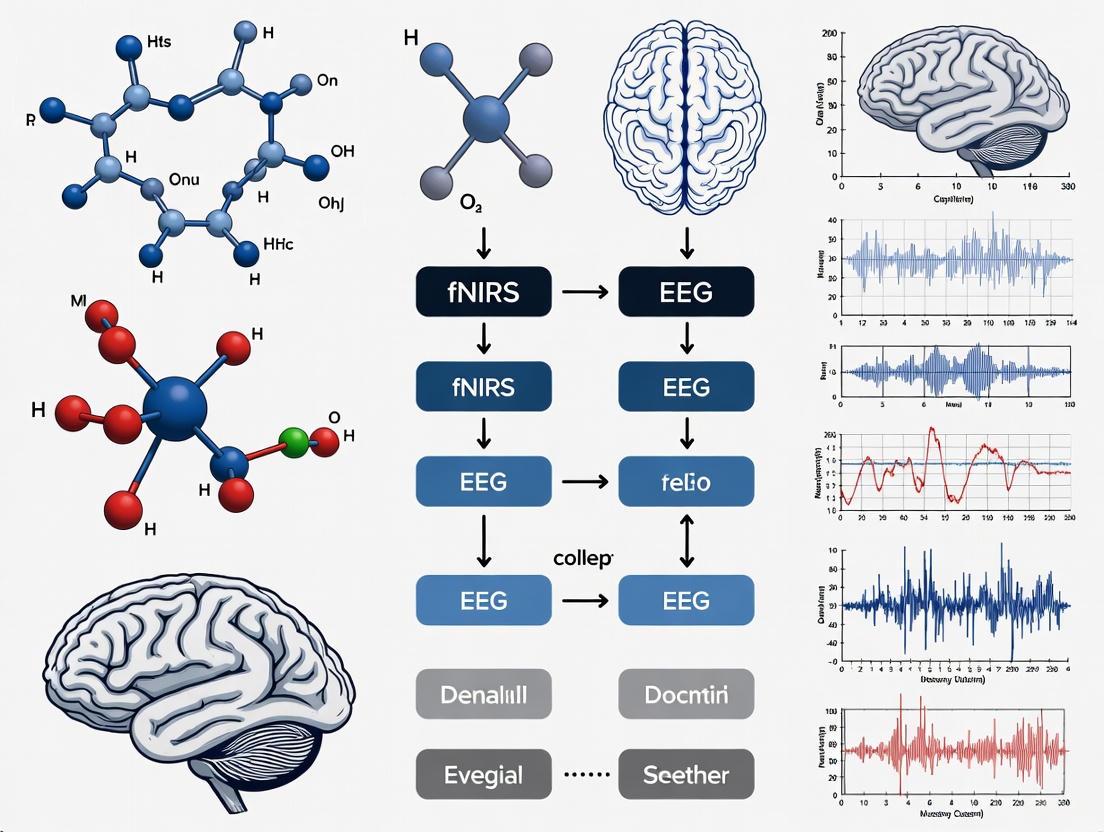

This article provides a definitive comparison of functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) and Electroencephalography (EEG) for studying the prefrontal cortex (PFC), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the fundamental principles, with EEG measuring neuronal electrical activity and fNIRS monitoring hemodynamic responses. The scope covers methodological considerations for experimental design, troubleshooting for common technical challenges, and a rigorous validation of the complementary strengths of each modality. Crucially, the article highlights the emerging power of integrated fNIRS-EEG systems, which offer a more complete picture of PFC function by combining millisecond electrical dynamics with localized hemodynamic changes. This guide aims to empower scientists in selecting the optimal tool—or combination—for their specific PFC research or clinical application.

Understanding the Core Principles: What fNIRS and EEG Measure in the Prefrontal Cortex

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive measurement method for brain activity that has become a cornerstone of cognitive neuroscience research due to its exceptional temporal resolution and hypersensitivity to dynamic changes in neural signaling [1]. The technique captures postsynaptic potentials generated when neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, which generate electric fields when sufficient neurons activate synchronously [1]. From a neurophysiological perspective, EEG provides a macroscopic readout of synchronous activity in large neural populations, offering researchers a direct window into the brain's millisecond-scale operational dynamics [2]. This unparalleled temporal resolution makes EEG particularly valuable for investigating fast cognitive processes such as attention, perception, and executive function, especially when compared to other neuroimaging modalities like functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).

The fundamental advantage of EEG lies in its ability to track neural events on the same timescale at which they occur, capturing brain dynamics that are often obscured by the slower hemodynamic responses measured by techniques like fNIRS and fMRI. While EEG signals have relatively poor spatial resolution due to passage through the skull, this limitation is offset by its millisecond temporal precision, low equipment cost, and widespread clinical applicability [1]. These characteristics have established EEG as an indispensable tool for both basic neuroscience research and clinical neurology applications, particularly when investigating the rapid neural computations underlying prefrontal cortex functions.

Fundamental Principles of EEG Analysis

EEG signals can be categorized into three distinct types based on their temporal characteristics and relationship to neural events. Time-invariant EEG describes signals where the brain's functional state remains relatively unchanged during recording, such as during resting-state measurements without specific psychological activities [1]. Accurate event-related EEG refers to neural responses induced by stimuli with precisely known onset times, allowing researchers to time-lock EEG responses to external events [1]. Random event-related EEG encompasses brain activity triggered by events with unpredictable timing, such as epileptic seizures or other spontaneous neural phenomena [1]. Understanding these classifications is essential for selecting appropriate analytical methods aligned with research objectives.

Core Analytical Approaches

Power Spectrum Analysis: This method quantifies energy changes across different frequency components in EEG signals, revealing state-dependent neural oscillations [1]. Common implementation approaches include Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), Welch method, and autoregressive modeling, each with distinct advantages for resolving specific spectral features.

Time-Frequency Analysis: By examining how spectral power changes over time, this approach captures the dynamic nature of neural oscillations during cognitive tasks, bridging the gap between pure spectral and temporal analyses.

Connectivity Analysis: This increasingly important method examines functional relationships between different brain regions by measuring synchronization patterns in neural activity, providing insights into network dynamics [3]. Techniques range from simple pairwise coherence measurements to sophisticated multivariate approaches like Granger causality.

Source Localization: Advanced computational techniques that estimate the intracranial origins of scalp-recorded EEG signals, addressing EEG's inherent limitations in spatial resolution.

Machine Learning Applications: Modern pattern recognition algorithms applied to EEG data for classifying cognitive states, detecting abnormalities, and predicting behavioral outcomes.

Table 1: EEG Frequency Bands and Their Functional Correlates

| Band | Frequency Range | Primary Functional Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Delta | 0.5-4 Hz | Deep sleep, pathological states |

| Theta | 4-8 Hz | Drowsiness, meditation, memory encoding |

| Alpha | 8-13 Hz | Relaxed wakefulness, inhibitory control |

| Beta | 13-30 Hz | Active thinking, focus, problem solving |

| Gamma | >30 Hz | Information integration, cognitive binding |

Comparative Methodological Framework: EEG vs. fNIRS

When investigating prefrontal cortex function, researchers must carefully consider the relative strengths and limitations of EEG and fNIRS. The two modalities capture fundamentally different aspects of neural activity: EEG directly measures electrical potentials from synchronized neuronal firing, while fNIRS indirectly assesses brain activity through neurovascular coupling by measuring changes in hemoglobin concentration [4].

Temporal and Spatial Resolution Characteristics

EEG provides millisecond temporal resolution, enabling the capture of neural dynamics at the speed of cognition itself. This allows researchers to track the rapid sequence of information processing stages within the prefrontal cortex during executive function tasks. However, EEG suffers from relatively poor spatial resolution due to the blurring effects of the skull and scalp, making precise localization of PFC subregional activity challenging [1].

In contrast, fNIRS offers better spatial resolution for cortical mapping but has significantly slower temporal resolution (typically 0.1-1 second) due to its dependence on the hemodynamic response, which evolves over several seconds following neural activation [4]. This fundamental trade-off between temporal and spatial resolution often dictates the choice of instrumentation based on specific research questions.

Practical Implementation Considerations

fNIRS demonstrates superior tolerance for movement artifacts compared to EEG, making it more suitable for studying naturalistic behaviors and real-world occupational settings [4]. This advantage has led to growing fNIRS applications in ecologically valid environments such as piloting aircraft, operating transportation systems, and performing office work [4]. EEG remains more susceptible to movement artifacts but provides broader brain coverage beyond cortical regions accessible to fNIRS.

Table 2: Direct Comparison of EEG and fNIRS for Prefrontal Cortex Studies

| Parameter | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond | Seconds |

| Spatial Resolution | ~1-2 cm | ~1 cm |

| Depth Sensitivity | Whole brain | Superficial cortex (2-3 cm) |

| Portability | High | High |

| Motion Tolerance | Low to moderate | High |

| Environmental Robustness | Sensitive to electrical interference | Less sensitive to interference |

| Direct vs. Indirect Measure | Direct neural electrical activity | Indirect hemodynamic response |

| Cost | Low to moderate | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol for Investigating Executive Function

The Stroop test represents a well-established protocol for examining prefrontal cortex function using both EEG and fNIRS. In a comparative study of elite retired boxers and healthy controls, researchers employed a multimodal approach combining both techniques [5]. The protocol involved:

Resting-state measurements: EEG recordings during eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions to establish baseline neural oscillatory patterns, with specific focus on alpha frequency spectral power (µV²) [5].

Task activation: fNIRS recordings from the prefrontal cortex during presentation of Stroop test stimuli in block design format, measuring hemodynamic responses during congruent and incongruent task conditions [5].

Data analysis: Comparison of alpha frequency power between groups and analysis of PFC activation patterns during cognitive task performance.

This protocol revealed that while no significant differences existed in resting-state alpha frequency between groups, boxers showed significantly lower activation over right dorsomedial PFC during congruent tasks and left dorsomedial PFC during incongruent tasks, suggesting long-term alterations in prefrontal processing efficiency [5].

Advanced Decoding Approaches

Modern EEG analysis has progressed beyond traditional spectral methods to include sophisticated decoding techniques that can extract detailed information about perceptual representations. Recent research has demonstrated that multivariate pattern analysis of scalp EEG can successfully decode visual color processing with remarkable precision [2]. The experimental protocol for such investigations includes:

This decoding approach has shown that color information follows a parametric coding space in neural representations, with prominent contributions from posterior electrodes contralateral to the visual stimulus [2]. The success of such fine-grained decoding demonstrates EEG's often-underestimated capacity to track detailed perceptual representations, bypassing potential confounds associated with spatial attention and eye movements that complicate interpretation of visual-spatial feature decoding.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EEG-fNIRS Prefrontal Cortex Studies

| Item | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-density EEG System | Neural electrical potential acquisition | 64-128 channels, impedance monitoring, compatible with fNIRS integration |

| fNIRS Hyperscanning Setup | Hemodynamic response measurement | 8-16 source-detector pairs over PFC, 650-1000 nm wavelength |

| Stroop Task Stimulus Set | Prefrontal cortex activation | Congruent/incongruent color-word pairs, block design presentation |

| Advanced Signal Processing Suite | Data preprocessing and analysis | EEGLAB/FieldTrip compatibility, artifact removal algorithms |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis Toolkit | Multivariate pattern classification | MATLAB/Python implementation, cross-validation protocols |

| Source Localization Software | Spatial mapping of neural sources | sLORETA, minimum norm estimation, individual MRI coregistration |

Integrated Research Applications

Tracking Neural Connectivity Patterns

EEG connectivity analysis has proven particularly valuable for investigating network-level disturbances in neurological and psychiatric conditions. Research on Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) exemplifies this approach, where EEG coherence measures have revealed a complex pattern of mixed over- and under-connectivity that underpins the core symptoms of the disorder [3]. Sophisticated multivariate connectivity analyses, including Granger causality and sLORETA source coherence, have provided more detailed and accurate information about network abnormalities than traditional pairwise measurements [3].

These advanced analytical approaches have demonstrated that ASD involves frontal hypercoherence combined with anterior-to-posterior hypocoherence, suggesting disrupted long-range connectivity alongside locally overconnected neural assemblies [3]. Such findings highlight how EEG connectivity measures can reveal network-level pathologies that might be obscured in other neuroimaging modalities.

Occupational Neuroscience Applications

The combination of EEG and fNIRS has found increasing application in occupational neuroscience, where researchers aim to understand brain function in real-world work environments. fNIRS particularly excels in these settings due to its robustness to movement artifacts and greater practicality for monitoring brain activity during naturalistic behaviors [4]. Studies have consistently shown increased oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) concentration and enhanced functional connectivity in the prefrontal cortex under conditions of high occupational workload [4].

EEG complements these findings by providing millisecond-temporal resolution data on neural dynamics during workload fluctuations, capturing transient cognitive events that might be missed by the slower hemodynamic response measured by fNIRS. Together, these modalities provide a more complete picture of how the prefrontal cortex manages cognitive demands during complex real-world tasks.

EEG remains an indispensable tool for capturing the millisecond-scale dynamics of prefrontal cortex function, providing unparalleled temporal resolution that complements the spatial strengths of other neuroimaging modalities like fNIRS. While each technique has distinct advantages—with EEG excelling in temporal precision and fNIRS in movement tolerance and spatial localization—their integration offers a particularly powerful approach for understanding the neural basis of cognition. Future methodological advances in multivariate pattern analysis, source localization, and multimodal integration will further enhance EEG's capacity to illuminate the rapid neural computations underlying executive function, both in healthy populations and clinical disorders. For researchers investigating the dynamic operations of the prefrontal cortex, EEG continues to provide a critical electrophysiological lens through which to observe the brain's millisecond-scale dynamics.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) has emerged as a pivotal neuroimaging technology that tracks cerebral blood oxygenation changes to investigate brain function. Within the context of prefrontal cortex studies, fNIRS occupies a unique position between the high temporal resolution of electroencephalography (EEG) and the high spatial resolution of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). As a hemodynamic monitoring technique, fNIRS measures changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations in the blood, providing an indirect marker of neural activity through the mechanism of neurovascular coupling [6] [7]. This physiological coupling forms the fundamental basis of fNIRS methodology, wherein localized neural firing triggers increased cerebral blood flow to deliver oxygen and nutrients, thus altering the relative concentrations of hemoglobin species in the active brain regions [7].

The technological foundation of fNIRS was established in 1977 when Jöbsis first demonstrated the ability to noninvasively assess brain oxygenation using near-infrared light [8] [7]. Over the subsequent decades, fNIRS has evolved into an established neuroimaging modality with particular relevance for investigating the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—a brain region critically involved in higher-order cognition, emotional processing, and executive function [9] [10]. The PFC's accessibility at the brain's surface makes it ideally suited for fNIRS investigation, as the technique typically penetrates to a depth of 1-2.5 cm beneath the scalp [6]. When compared to EEG, which measures electrical activity from pyramidal neurons with millisecond temporal resolution but limited spatial accuracy, fNIRS offers superior spatial localization for cortical mapping while maintaining greater tolerance to movement artifacts [6] [7]. This complementary relationship has motivated growing interest in combined fNIRS-EEG approaches that simultaneously capture both the electrical and hemodynamic dimensions of neural processing in the PFC [6] [7].

Technical Foundation: The Biophysical Principles of fNIRS

The Neurovascular Coupling Link

The physiological foundation of fNIRS rests on the well-established principle of neurovascular coupling, the mechanism by which neural activity triggers localized hemodynamic responses. When neurons become active, they require increased energy delivery in the form of glucose and oxygen. This metabolic demand triggers an increase in cerebral blood flow that overshoots the actual oxygen consumption needs, resulting in a characteristic hemodynamic response pattern: a rapid increase in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) accompanied by a smaller decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the activated brain region [7]. This blood oxygenation change typically peaks 2-6 seconds after neural activation, creating the temporal signature that fNIRS captures [6]. The neurovascular coupling forms the theoretical bridge between the direct electrical activity measured by EEG and the indirect hemodynamic response measured by fNIRS, enabling researchers to draw inferences about neural processing from observed blood oxygenation changes [7].

Optical Properties of Biological Tissues

fNIRS leverages the unique optical window in the near-infrared spectrum (approximately 600-1000 nm) where biological tissues exhibit relatively low absorption, allowing light to penetrate several centimeters through the scalp and skull to reach the cerebral cortex. Within this window, the primary absorbers in brain tissue are hemoglobin molecules, with oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) displaying distinct absorption spectra [7]. fNIRS systems typically employ two or more wavelengths within this near-infrared range (commonly around 695 nm and 830 nm) to differentially quantify HbO and HbR concentration changes [11]. The differential absorption at these specific wavelengths enables the separation of HbO and HbR concentration changes using the Modified Beer-Lambert Law, which forms the mathematical foundation for converting detected light intensity changes into meaningful physiological information about brain activity [8] [7].

From Light Attenuation to Hemodynamic Changes

The Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL) provides the mathematical framework for converting measured light attenuation changes into hemodynamic concentration values. The MBLL relates the change in light attenuation (ΔA) to changes in chromophore concentrations through the equation: ΔA = ∑ (εi · Δci · DPF · L) + G, where εi is the extinction coefficient of the i-th chromophore (HbO or HbR), Δci is its concentration change, DPF is the differential pathlength factor accounting for increased photon pathlength due to scattering, L is the source-detector separation distance, and G represents measurement geometry factors [8]. By measuring attenuation changes at multiple wavelengths and solving the resulting system of equations, fNIRS calculates relative concentration changes for both HbO and HbR. The typical source-detector separation of 3 cm in fNIRS systems represents a balance between sufficient light penetration depth to reach the cerebral cortex and maintaining adequate signal strength [11]. This biophysical foundation enables fNIRS to provide a noninvasive window into the hemodynamic correlates of neural activity in the prefrontal cortex and other superficial cortical regions.

Table 1: Key Biophysical Parameters in fNIRS

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Physiological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelengths | 695 nm, 830 nm [11] | Optimal separation of HbO and HbR absorption spectra |

| Source-Detector Separation | 3 cm [11] | Balances cortical penetration depth with signal strength |

| Hemodynamic Response Delay | 2-6 seconds [6] | Temporal delay due to neurovascular coupling |

| Penetration Depth | 1-2.5 cm [6] | Reaches superficial cortical layers including PFC |

| Sampling Rate | 10 Hz [11] to >100 Hz | Temporal resolution for capturing hemodynamic dynamics |

fNIRS vs EEG: A Comparative Technical Analysis

Fundamental Measurement Differences

fNIRS and EEG capture fundamentally different aspects of brain activity through distinct biophysical mechanisms. fNIRS measures hemodynamic responses by detecting changes in near-infrared light attenuation related to blood oxygenation, providing an indirect metabolic correlate of neural activity. In contrast, EEG measures electrical potentials generated by synchronized postsynaptic activity of cortical pyramidal neurons, offering a direct view of neural electrophysiology [6] [7]. This fundamental difference in measurement target creates complementary strengths and limitations: EEG provides exceptional temporal resolution on the millisecond scale, ideal for capturing rapid neural dynamics, while fNIRS offers superior spatial resolution for localizing cortical activity, particularly in prefrontal regions [6]. The temporal characteristics of these modalities differ significantly, with fNIRS capturing the relatively slow hemodynamic response (seconds) compared to EEG's immediate electrical signatures (milliseconds) of neural events [7].

Practical Implementation Considerations

In practical research settings, fNIRS and EEG present different implementation challenges and advantages. fNIRS demonstrates significantly greater tolerance to movement artifacts compared to EEG, making it more suitable for studies involving naturalistic movements, pediatric populations, or real-world scenarios such as classroom settings, sports performance, or driving simulations [6]. EEG systems are typically more sensitive to electromagnetic interference and require careful electrode preparation including conductive gels or pastes, while fNIRS requires minimal skin preparation beyond ensuring proper optode contact [6]. From a portability standpoint, both modalities now offer wearable, wireless systems, though fNIRS systems generally come at a higher cost, particularly for high-density configurations [6]. For prefrontal cortex studies specifically, fNIRS provides more straightforward localization of dorsal and ventral PFC subregions, while EEG offers comprehensive whole-scalp coverage but with limited ability to distinguish closely spaced PFC subregions due to the blurring effect of the skull and scalp on electrical signals [6] [9].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: fNIRS vs EEG for Prefrontal Cortex Studies

| Characteristic | fNIRS | EEG |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Origin | Hemodynamic response (blood oxygenation) [6] | Electrical activity of pyramidal neurons [6] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (seconds) [6] | High (milliseconds) [6] |

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate (better than EEG) [6] | Low (centimeter-level) [6] |

| Depth Sensitivity | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm) [6] | Cortical surface [6] |

| Movement Tolerance | High [6] | Low - susceptible to movement artifacts [6] |

| Portability | High - wearable systems available [6] [10] | High - lightweight wireless systems [6] |

| Best Suited PFC Applications | Sustained cognitive states, workload assessment, emotional processing [6] | Rapid cognitive tasks, ERPs, brain-computer interfaces [6] |

Integrated fNIRS-EEG Approaches

The complementary nature of fNIRS and EEG has motivated growing interest in multimodal integration approaches that simultaneously capture both hemodynamic and electrophysiological aspects of prefrontal cortex function [7]. Integrated fNIRS-EEG systems provide a more comprehensive picture of brain activity by measuring both the direct electrical neural dynamics (via EEG) and the subsequent metabolic hemodynamic response (via fNIRS) [6] [7]. This multimodal approach offers built-in validation through the neurovascular coupling relationship and enables investigation of complex questions about how electrical and hemodynamic brain responses interrelate in different cognitive states and clinical conditions [7]. Technical implementation of concurrent fNIRS-EEG requires careful consideration of sensor placement compatibility, with both systems often using the international 10-20 system for positioning [6]. Hardware integration can be achieved through synchronized triggering or integrated commercial systems, while data fusion techniques include joint Independent Component Analysis (jICA), canonical correlation analysis (CCA), and machine learning approaches that combine feature sets from both modalities [6] [7]. For prefrontal cortex studies specifically, this integrated approach can reveal both the rapid electrical dynamics of cognitive control processes and the sustained hemodynamic patterns associated with emotional regulation or working memory load in the PFC [9] [10].

Experimental Methodology: fNIRS Protocol Implementation

fNIRS Instrumentation and Setup

Modern fNIRS systems, particularly continuous-wave (CW) systems that dominate research applications, consist of optodes (sources and detectors) arranged in specific arrays over the prefrontal cortex [8] [7]. Sources typically employ lasers or LEDs that emit near-infrared light at specific wavelengths (commonly 695 nm and 830 nm), while detectors measure the intensity of light that has traveled through the brain tissue [11] [7]. The experimental setup begins with proper optode placement according to the international 10-20 system, ensuring consistent positioning across participants and sessions [8]. For prefrontal cortex studies, optodes are typically arranged to cover key PFC subregions including the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), frontopolar cortex (FPC), and Brodmann Area 8 (BA8) [11]. Recent advancements include the development of wearable, wireless fNIRS systems that enable naturalistic data collection in real-world environments, with some platforms incorporating augmented reality guidance for reproducible device placement without technical assistance [10]. Proper setup requires ensuring good optode-scalp contact while minimizing pressure, verifying signal quality through real-time monitoring of detected light intensity, and establishing a stable baseline recording before task administration [8].

Paradigm Design Considerations

Effective fNIRS experimental paradigms must account for the hemodynamic response function's temporal characteristics, typically employing block designs, event-related designs, or resting-state protocols [8]. Block designs present stimuli of the same condition grouped together in extended periods (typically 20-30 seconds), allowing the hemodynamic response to reach a steady state and providing robust detection power at the expense of temporal precision [11]. Event-related designs present brief, isolated stimuli with variable inter-stimulus intervals (typically >10-15 seconds) to allow the hemodynamic response to return to baseline, enabling analysis of individual trial responses but with reduced statistical power [8]. Resting-state paradigms record spontaneous brain activity in the absence of structured tasks, typically for 5-10 minutes, to investigate functional connectivity between PFC regions and other brain networks [10]. For all paradigms, careful consideration must be given to the number and duration of trials/blocks, with longer recording durations generally improving signal-to-noise ratio and reliability, particularly for individual-level analyses [10]. Additionally, task instructions should be standardized, practice sessions should be provided to minimize learning effects, and potential confounding factors such as systemic physiology (heart rate, blood pressure, respiration) should be monitored or controlled [8].

Data Processing Pipeline

The fNIRS data processing pipeline transforms raw light intensity measurements into meaningful hemodynamic responses through a series of computational steps. Initial processing typically includes converting raw light intensity to optical density, then applying the Modified Beer-Lambert Law to calculate concentration changes in HbO and HbR [8]. Quality control measures identify and exclude channels with poor signal quality based on signal-to-noise ratio metrics [8]. Motion artifact correction represents a critical step, with methods ranging from simple spike removal and wavelet-based correction to more sophisticated approaches using accelerometer data or correlation-based signal improvement [8]. Bandpass filtering (typically 0.01-0.2 Hz) removes physiological noise from cardiac pulsation (∼1 Hz), respiration (0.2-0.3 Hz), and very low-frequency drift [8]. For statistical analysis, the general linear model (GLM) approach is commonly employed, modeling the expected hemodynamic response to experimental conditions while incorporating regressors for confounding factors [11] [8]. More advanced processing may include superficial layer regression to reduce scalp hemodynamic contributions, independent component analysis (ICA) for separating neural from non-neural signals, and functional connectivity analysis to investigate interactions between PFC regions [8] [7].

Applications in Prefrontal Cortex Research

Cognitive Neuroscience and Mental Health

fNIRS has become an invaluable tool for investigating prefrontal cortex function across various cognitive domains and mental health conditions. In cognitive neuroscience, fNIRS reliably detects PFC activation during executive function tasks such as working memory (N-back tasks), cognitive control (Flanker and Go/No-Go tasks), and problem-solving [10]. The portability and motion tolerance of fNIRS make it particularly suitable for studying naturalistic cognitive processes that cannot be easily investigated in constrained laboratory environments [6] [10]. In mental health research, fNIRS has demonstrated clinical utility for identifying PFC dysfunction in various psychiatric disorders. For depression, fNIRS studies have revealed characteristic patterns of prefrontal hypoactivation during cognitive and emotional tasks, with potential as objective biomarkers for diagnostic assessment and treatment monitoring [9]. For Parkinson's disease, fNIRS has shown promise in early detection, with one study achieving 85% accuracy in differentiating patients from healthy controls using support vector machine classification of PFC activation patterns [11]. These clinical applications benefit from fNIRS's ability to capture individualized functional patterns through dense-sampling approaches, moving beyond group-level comparisons to precision mental health assessment [10].

Educational Neuroscience and Neurodevelopment

The application of fNIRS in educational neuroscience capitalizes on its advantages for naturalistic settings, enabling investigation of PFC function during authentic learning activities. fNIRS studies have examined prefrontal hemodynamic responses during various educational tasks, including video lectures, virtual laboratories, and problem-solving activities [12]. These investigations have revealed characteristic patterns of PFC activation associated with different learning stages and cognitive demands, such as increased frontal theta and beta activity during quizzes compared to passive lecture viewing [12]. In neurodevelopmental research, fNIRS's tolerance to movement artifacts makes it particularly valuable for studying pediatric populations, where traditional neuroimaging methods face challenges [6]. fNIRS has been successfully employed to investigate the development of prefrontal executive functions throughout childhood and adolescence, revealing characteristic developmental trajectories of PFC specialization and connectivity [8]. The quiet operation and non-confinement of fNIRS systems also facilitate studies of infant and child cognition, including language acquisition, social interaction, and attentional processes, providing insights into typical and atypical neurodevelopment [6] [8].

Pharmaceutical Research and Clinical Trials

In pharmaceutical research and clinical trials, fNIRS offers a practical neuroimaging tool for evaluating drug effects on prefrontal cortex function. The non-invasive nature, relatively low cost, and repeatability of fNIRS measurements make it suitable for longitudinal studies assessing treatment efficacy and dose-response relationships [11] [10]. fNIRS can quantify changes in PFC hemodynamic responses following pharmacological interventions, providing objective biomarkers of target engagement and neural effects [10]. For neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease, fNIRS has been employed to detect characteristic patterns of frontal lobe dysfunction that may serve as endpoints in clinical trials [11]. In antidepressant development, fNIRS measurements of PFC activity during emotional and cognitive tasks can provide quantitative metrics of treatment response beyond subjective symptom reports [9]. The ability to collect dense-sampled fNIRS data through at-home or clinic-based portable systems enables more frequent monitoring of treatment effects than possible with traditional neuroimaging, potentially detecting subtle changes in PFC function that correlate with clinical outcomes [10]. As precision medicine advances, fNIRS may contribute to identifying neurophysiological subtypes within diagnostic categories that show differential treatment responses, ultimately guiding more targeted therapeutic approaches [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential fNIRS Research Materials and Equipment

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Instrument | Measures light attenuation to compute HbO/HbR concentrations | Continuous-wave systems with 2+ wavelengths (695±10 nm, 830±10 nm); sampling rate ≥10 Hz [11] [7] |

| Optodes | Source and detector components for light transmission/reception | Laser diode/LED sources; photodiode/APD detectors; 3 cm source-detector separation [11] |

| Headgear/Cap | Holds optodes in predetermined positions on scalp | Compatible with international 10-20 system; adjustable for head size variability [8] |

| Augmented Reality Placement Guide | Ensures reproducible optode positioning across sessions | Tablet-based systems using camera guidance [10] |

| Data Processing Software | Converts raw signals to hemodynamic measures | Includes motion correction, filtering, GLM analysis capabilities [8] |

| Systemic Physiology Monitors | Records potential confounding physiological signals | Pulse oximeter, respiration belt, blood pressure monitor [8] |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Administers experimental paradigms | Precise timing synchronization with fNIRS acquisition [8] |

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Machine Learning Integration

The integration of machine learning with fNIRS data has significantly advanced the analytical toolkit for prefrontal cortex research. Supervised learning approaches have demonstrated particular utility for classification of clinical conditions based on PFC activation patterns. For instance, support vector machine (SVM) algorithms applied to fNIRS data have achieved 85% accuracy in differentiating Parkinson's disease patients from healthy controls, with the frontopolar cortex identified as the most discriminative region [11]. Other algorithms including k-nearest neighbors (K-NN), random forest (RF), and logistic regression (LR) have also been successfully applied to fNIRS data for various classification tasks [11]. Beyond diagnostic classification, machine learning enables the identification of feature importance through methods like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis, which reveals the relative contribution of specific fNIRS channels to classification models and enhances interpretability [11]. For individual-level prediction in precision medicine applications, dense-sampling approaches combined with machine learning can identify person-specific functional patterns that deviate from group-level averages, potentially enabling more individualized assessment and intervention planning [10]. These advanced analytical approaches transform fNIRS from a purely group-level research tool to a clinically applicable technology for personalized assessment of PFC function.

Connectivity and Network Analysis

Functional connectivity analysis of fNIRS data extends beyond localized activation to investigate interactions between prefrontal regions and other brain areas. Using correlation-based approaches, phase synchronization methods, or graph theory metrics, researchers can characterize the functional networks involving the PFC during various cognitive states and their alterations in clinical conditions [8] [10]. Studies have demonstrated that individualized functional connectivity patterns derived from dense-sampled fNIRS data show high test-retest reliability, supporting their potential as stable biomarkers for precision psychiatry applications [10]. In depression research, connectivity analyses have revealed disrupted prefrontal networks during emotional processing, particularly involving frontopolar and dorsolateral PFC regions [9]. For neurodegenerative disorders, fNIRS connectivity measures can detect early alterations in prefrontal network integrity that may precede overt cognitive symptoms [11]. The combination of functional connectivity analysis with graph theory approaches enables quantification of network properties such as modularity, efficiency, and hub distribution, providing comprehensive characterization of PFC network organization in health and disease [10]. These advanced connectivity analyses benefit from the dense spatial sampling achievable with modern high-density fNIRS systems, which provide sufficient coverage to investigate multiple PFC subregions and their interactions with other cortical areas [10].

fNIRS provides a powerful hemodynamic lens for investigating prefrontal cortex function through its unique ability to track blood oxygenation changes associated with neural activity. Its favorable balance of spatial and temporal resolution, combined with portability, tolerance to movement artifacts, and relatively low cost, positions fNIRS as an indispensable tool between EEG and fMRI in the neuroimaging arsenal [6] [7]. The continuing evolution of fNIRS technology—including wearable systems, high-density arrays, and automated placement guidance—promises to further expand its applications in naturalistic settings and clinical practice [10]. For prefrontal cortex studies specifically, fNIRS offers robust detection of activation patterns during cognitive tasks, emotional processing, and clinical interventions, with growing evidence supporting its utility as a biomarker for various neurological and psychiatric conditions [11] [9] [10].

Future directions in fNIRS research include the development of more sophisticated analytical approaches for modeling complex neurovascular coupling relationships, enhancing individual-level predictive accuracy through dense-sampling and machine learning, and standardizing methodological practices to improve reproducibility [8] [10]. The integration of fNIRS with other modalities, particularly EEG, will continue to provide multidimensional insights into both electrical and hemodynamic aspects of PFC function [6] [7]. As fNIRS technology becomes more accessible and analytical methods more refined, this hemodynamic imaging approach is poised to make significant contributions to basic cognitive neuroscience, clinical assessment, and therapeutic development, ultimately advancing our understanding of the prefrontal cortex's central role in human brain function and dysfunction.

This technical guide provides a direct comparison between functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) and Electroencephalography (EEG) for researching the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC is critically involved in higher-order cognitive functions, and choosing the appropriate neuroimaging tool is paramount for experimental validity and ecological relevance. fNIRS measures hemodynamic responses (blood oxygenation) related to neural activity, offering moderate spatial resolution and high motion tolerance. In contrast, EEG measures the brain's electrical activity directly, providing millisecond-level temporal resolution but with more limited spatial localization [13]. The following sections detail the core technical specifications, experimental protocols, and practical considerations to guide researchers and scientists in selecting the optimal modality for their specific study designs.

Core Technical Comparison: fNIRS vs. EEG

The fundamental difference between these modalities lies in the physiological phenomena they capture. The choice is often a trade-off between capturing the when of brain activity (EEG) versus the where (fNIRS) [13]. For PFC studies, which often involve sustained cognitive tasks, fNIRS provides a robust measure of metabolic effort, while EEG is ideal for capturing rapid neural oscillations and event-related potentials.

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications for fNIRS and EEG

| Specification | EEG (Electroencephalography) | fNIRS (Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy) |

|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Electrical activity from postsynaptic potentials of cortical neurons [13] | Hemodynamic response (changes in oxygenated (HbO) & deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR)) [13] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (milliseconds) [13] | Low (seconds, due to slow hemodynamic response) [13] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeter-level, due to signal dispersion through skull/scalp) [13] | Moderate (better than EEG; can localize to surface cortical areas) [13] |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface [13] | Outer cortex (~1–2.5 cm deep) [13] |

| Portability & Motion Tolerance | High for wireless systems; however, highly susceptible to movement artifacts [13] | High; more tolerant to subject movement, ideal for naturalistic studies [13] |

| Typical PFC Setup Complexity | Moderate; requires electrode gel and scalp prep for high-quality data [13] | Moderate; optode placement requires minimal skin preparation [13] |

| Typical System Cost Range | \$1,000 - \$25,000+ (research-grade) [14] [15] | Generally higher than EEG, especially for high-density systems [13] |

| Market Size & Growth (for context) | ~\$1.52B in 2025, growing at 10.24% CAGR to ~\$3.65B by 2034 [16] | Projected to grow at a CAGR of 3.6% to 12.5%, reaching ~\$175-650M in the forecast period [17] [18] |

Experimental Protocol for a Hybrid fNIRS-EEG Study

Simultaneous fNIRS-EEG recording is a powerful multimodal approach that provides a more comprehensive picture of brain activity by combining the high temporal resolution of EEG with the improved spatial resolution of fNIRS [13]. This is particularly valuable for studying the complex functions of the PFC. The following protocol is adapted from a semantic neural decoding study, a task heavily reliant on PFC function [19].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a simultaneous fNIRS-EEG experiment, from participant preparation to data fusion.

Protocol Steps

- Participant Preparation: Recruit participants according to study criteria (e.g., right-handed, native language speakers for language tasks) [19]. Obtain informed consent.

- Equipment Setup:

- Use a high-density EEG cap with pre-defined openings for fNIRS optodes or an integrated hybrid cap [13].

- Ensure fNIRS optodes and EEG electrodes do not physically interfere. Mount optodes using holders that avoid electrode contact points.

- Sensor Placement: Place both EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes according to the International 10-20 system, with dense coverage over the prefrontal cortex regions of interest [13].

- Signal Quality Check:

- For EEG: Ensure electrode impedances are below 10 kΩ for research-grade data.

- For fNIRS: Verify signal strength and ensure optodes have good contact with the scalp.

- Synchronization: Synchronize the EEG and fNIRS systems using a shared clock or external hardware triggers (e.g., TTL pulses) at the beginning of the recording and for all task events [13].

- Task Execution: Participants perform cognitive tasks. A sample task block for semantic categorization [19] is below.

- Data Acquisition: Record continuous EEG and fNIRS data throughout the task, marking all event onsets (cue presentation, task periods) in both data streams.

- Post-processing: Process EEG and fNIRS data through separate, modality-specific pipelines before integration and fusion analysis [13].

Example Prefrontal Cortex Task

This task is designed to engage the PFC in semantic processing and mental imagery [19].

- Stimuli: Images representing concepts from two semantic categories (e.g., "Animals" and "Tools").

- Procedure:

- Cue Presentation (2s): An image (e.g., a picture of a "cat" or "hammer") is displayed on the screen.

- Mental Task Period (3s): The screen goes blank, and the participant is cued to perform one of four mental tasks internally:

- Silent Naming: Silently name the object in their mind.

- Visual Imagery: Visualize the object in their mind.

- Auditory Imagery: Imagine the sounds the object makes.

- Tactile Imagery: Imagine the feeling of touching the object.

- Rest Period (10-15s): A cross-hair is displayed for a variable inter-trial interval to allow the hemodynamic response to return to baseline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Equipment and Analysis Tools for fNIRS and EEG Research

| Item | Function & Importance in Research |

|---|---|

| fNIRS System | Measures hemodynamic responses. Portable systems (e.g., from NIRx, Artinis) enable real-world PFC studies on cognitive load, gait, and social interaction [18] [20]. |

| EEG System | Measures electrical brain activity. Research-grade systems (e.g., from Brain Products, BioSemi, EMOTIV) are crucial for capturing fast neural dynamics in the PFC during decision-making or error processing [14]. |

| Integrated Caps | Specialized headcaps (e.g., from Wearable Sensing, ANT Neuro) allow co-location of fNIRS optodes and EEG electrodes, facilitating multimodal data collection [13]. |

| Conductive Gel (EEG) | Improves electrical conductivity between scalp and electrodes, essential for high-quality, low-impedance EEG recordings [14] [15]. |

| Abrasive Prep Gel & Skin Cleaning | Used to gently abrade the scalp and remove dead skin cells, significantly reducing impedance for EEG electrodes [14]. |

| Saline Solution (for saline-based EEG) | Used to hydrate saline-based electrodes (e.g., in EMOTIV EPOC X); easier cleanup than gel but may be less stable for long recordings [14] [15]. |

| Data Analysis Software (Modality-Specific) | Software like BrainVision Analyzer (EEG) or Homer2 (fNIRS) is required for pre-processing, artifact removal, and statistical analysis of the raw data [21]. |

| Advanced Analysis Toolboxes (Python/MATLAB) | Toolboxes (e.g., MNE-Python, EEGLAB, FieldTrip, NIRS Brain AnalyzIR) provide customizable pipelines for advanced analysis and data fusion [19] [21]. |

The decision between fNIRS and EEG for prefrontal cortex research is not a matter of which technology is superior, but which is most appropriate for the specific research question. EEG is the unequivocal choice for studies requiring precise timing of neural events, such as investigating the rapid sequence of neural engagement during a reasoning task. Conversely, fNIRS is better suited for studies that require localization of sustained activity in the PFC during tasks like emotional regulation, cognitive workload, or in settings where participant movement is necessary, such as neurorehabilitation or studies with children. The emerging trend of simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording offers a powerful hybrid approach, mitigating the limitations of each standalone method and providing a more holistic view of the brain's electrical and metabolic activity in the prefrontal cortex [19] [13]. As both technologies continue to advance in portability, data analysis sophistication, and accessibility, their value in both basic neuroscience and applied drug development will only increase.

Neurovascular coupling (NVC) describes the fundamental physiological process that ensures a tight temporal and spatial connection between neural activity and subsequent changes in local cerebral blood flow (CBF) [22] [23]. This mechanism delivers oxygen and glucose to activated brain cells, meeting the high energy demands of neural computation, while simultaneously clearing metabolic byproducts [22] [24]. The adult brain constitutes only about 2% of total body weight yet consumes approximately 20% of the body's energy, making this continuous supply of metabolic substrates via CBF critical for normal function [22] [23]. The NVC process is mediated by synaptic activity that triggers the release of various vasoactive molecules from neurons, astrocytes, and vascular cells, ultimately inducing changes in CBF and cerebral blood volume (CBV) by acting on vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes [22] [23].

Understanding NVC is paramount because it forms the physiological basis for several non-invasive functional neuroimaging techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), and positron emission tomography (PET). These techniques rely on the assumption that measured hemodynamic changes are a reliable proxy for underlying neural activity [22] [23]. However, interpreting data from these modalities requires a detailed comprehension of the NVC, as alterations or impairments in this coupling can lead to misinterpretation of brain activation signals. Furthermore, investigating NVC itself provides insights into the pathophysiology of various neuropsychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) [24], Alzheimer's disease [24], and opiate addiction [25], where cerebrovascular regulation may be compromised.

The Complementary Nature of EEG and fNIRS

Electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) are two non-invasive neuroimaging techniques that, when combined, offer a powerful tool for investigating NVC by providing simultaneous measurements of the brain's electrical and hemodynamic activities [26] [27].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of EEG and fNIRS

| Feature | EEG (Electroencephalography) | fNIRS (Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy) |

|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Electrical activity from postsynaptic potentials of cortical neurons [27] | Hemodynamic response (changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin) [27] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (milliseconds) [27] | Low (seconds) [27] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeter-level) [27] | Moderate (superior to EEG, but limited to cortical surface) [28] [27] |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface [27] | Outer cortex (~1–2.5 cm deep) [27] |

| Signal Source | Direct neural synchrony and oscillatory activity [25] | Indirect hemodynamic response via neurovascular coupling [27] |

| Sensitivity to Motion | High – susceptible to movement artifacts [27] | Low – relatively robust to motion [28] [27] |

| Key Strengths | Captures fast neural dynamics (e.g., event-related potentials) [27] | Localized cortical activation, suitable for naturalistic settings [28] [27] |

EEG measures the brain's electrical activity with high temporal resolution, capturing direct neural dynamics on a millisecond scale, which is ideal for analyzing rapid cognitive processes. However, its spatial resolution is limited [27]. In contrast, fNIRS monitors hemodynamic responses by measuring changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations using near-infrared light. It offers better spatial resolution for surface cortical areas like the PFC and is more tolerant to movement artifacts, making it suitable for more naturalistic study environments [28] [27]. The combination of these modalities creates a bimodal approach that overcomes the limitations of each technique used in isolation, allowing researchers to correlate fast electrophysiological events with the slower, localized hemodynamic changes that define NVC [29] [26] [30].

Quantitative Models and Methodological Frameworks for NVC

A Unified Mathematical Model for NVC

Recent scientific efforts have focused on integrating disparate data into a unified quantitative model for NVC. Sten et al. (2023) presented a comprehensive mathematical model that brings together experimental data from mice, monkeys, and humans, preserving mechanistic insights across species [22] [23]. This model connects a mechanistic NVC model for arteriole control with a Windkessel model of blood flow, pressure, volume, and hemoglobin content in arterioles, capillaries, and venules, ultimately providing a complete description of the Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal used in fMRI [22] [23].

Key cell-specific contributions identified through this cross-species modeling include [22] [23]:

- The first rapid dilation in the vascular response is caused by NO-interneurons.

- The main part of the dilation during longer stimuli is caused by pyramidal neurons.

- The post-peak undershoot is caused by NPY-interneurons.

This model successfully predicts independent validation data and represents a significant advancement in understanding the complex, multi-scale physiology of NVC, moving beyond purely statistical interpretations of hemodynamic data [22] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating CMI with EEG-fNIRS

Lin et al. (2023) developed a novel bimodal analysis framework to investigate Cognitive-Motor Interference (CMI), a phenomenon where the simultaneous execution of a motor and cognitive task deteriorates performance in one or both tasks [29].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocol from Lin et al. (2023)

| Protocol Aspect | Detailed Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | 16 healthy young participants [29] |

| Experimental Tasks | Upper limb single motor task, single cognitive task, and cognitive-motor dual task [29] |

| Data Acquisition | Simultaneous recording of EEG and fNIRS signals [29] |

| Signal Analysis | A novel framework to extract task-related components for EEG and fNIRS separately, followed by correlation analysis of these components [29] |

| Key Findings | Decreased neurovascular coupling in the dual task across theta, alpha, and beta EEG rhythms, indicating divided attention due to extra cognitive interference [29] |

| Validation | The proposed framework demonstrated significantly higher within-class similarity and between-class distance compared to canonical channel-averaged methods [29] |

The methodology confirmed that the proposed framework was more effective at characterizing neural patterns than traditional methods, providing new evidence for the mechanism of NVC in CMI [29]. This exemplifies a robust protocol for bimodal investigation of complex cognitive processes.

Workload Classification Using Functional Brain Connectivity and Machine Learning

Another advanced application of concurrent EEG-fNIRS is in the classification of mental workload. One study extracted not only univariate features (like Power Spectral Density from EEG) but also bivariate functional brain connectivity (FBC) features in the time and frequency domains [30]. These were combined with fNIRS-derived HbO and HbR indicators and fed into machine learning classifiers [30].

The workflow and outcomes of this approach can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Workflow for EEG/fNIRS-based Workload Classification. This diagram outlines the processing pipeline from data acquisition to the final classification outcome, highlighting the distinct feature sets extracted from each modality.

This multimodal approach achieved a classification accuracy of 77% for 0-back vs. 2-back tasks and 83% for 0-back vs. 3-back tasks, significantly outperforming methods using a single modality [30]. The study also found that the most discriminative regions for EEG and fNIRS differed: the posterior area (POz electrode) for EEG in the alpha band, and the right frontal region (AF8) for fNIRS [30]. This underscores the complementary nature of the two signals and the value of their integration.

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of NVC

At the microscopic scale, NVC is governed by a complex interplay of cellular signaling between neurons, astrocytes, and blood vessels. The canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF), measured by BOLD-fMRI, consists of two or three phases: a debated initial dip, the main response, and a post-peak undershoot. This qualitative shape and its timing (a peak at 3-6 seconds post-stimulus, lasting 15-20 seconds) are highly conserved across species, suggesting preserved mechanisms [22] [23].

The intricate signaling pathways that underlie this response can be summarized as follows:

Diagram 2: Core Cellular Pathways in Neurovascular Coupling. This diagram illustrates how neuronal activity triggers cell-type-specific signaling pathways, leading to the release of vasoactive messengers and ultimately an increase in local blood flow.

The model by Sten et al. assigns specific temporal roles to different interneurons: the first rapid dilation is mediated by NO-interneurons, the main sustained dilation by pyramidal neurons, and the post-peak undershoot by NPY-interneurons [22] [23]. These detailed mechanistic insights, often derived from animal optogenetics studies, are now being translated and preserved in the quantitative analysis of human data, enabling a more profound understanding of the neurobiology underpinning non-invasive imaging signals [22] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

To conduct rigorous research in this field, scientists rely on a suite of specialized tools and methodologies. The table below details key "research reagent solutions" and other essential components for EEG-fNIRS studies of the prefrontal cortex and NVC.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for EEG-fNIRS Research on NVC

| Tool or Material | Function and Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Multi-channel EEG System | Records electrical brain activity with high temporal resolution; essential for capturing neural oscillations (e.g., theta, alpha, beta) related to cognitive tasks [29] [30]. |

| fNIRS System with HbO/HbR Detection | Measures hemodynamic responses in the PFC via near-infrared light; provides the vascular component for NVC analysis [29] [28] [30]. |

| Synchronization Hardware/Software | Crucial for temporal alignment of EEG and fNIRS data streams, ensuring the correlation of electrical and hemodynamic events is accurate [27]. |

| Cognitive & Motor Task Paradigms | Well-established experimental protocols (e.g., n-back tasks, CMI paradigms) designed to elicit measurable and specific neural and hemodynamic responses in the PFC [29] [30]. |

| Signal Preprocessing Toolboxes | Software packages (e.g., BBCI in MATLAB, EEGLAB) for artifact removal, filtering, and baseline correction of raw EEG and fNIRS signals [30]. |

| Mathematical NVC Models | Quantitative frameworks that integrate multimodal data to simulate and predict the relationship between neural activity and hemodynamic changes [22] [23]. |

| Functional Brain Connectivity (FBC) Metrics | Bivariate analysis methods used to estimate statistical interdependencies between different brain regions from EEG data, revealing network-level interactions [30]. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | Algorithms (e.g., SVM, LDA) used to decode mental states or workload levels from combined EEG-fNIRS feature sets [30]. |

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The study of NVC using bimodal EEG-fNIRS has significant translational potential. Abnormal NVC, or neurovascular decoupling, is increasingly recognized as a potential neuropathological mechanism in various psychiatric and neurological disorders. For instance, a 2025 study on first-episode drug-naïve patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) found reduced whole-brain NVC coupling, with distinct spatial-temporal patterns that varied based on disease severity and sex [24]. Similarly, research on patients with heroin dependency demonstrated desynchronized lower alpha rhythms and decreased hemodynamic connectivity in the PFC, suggesting cerebrovascular injury resulting from chronic opiate intake [25].

A promising frontier is functional-pharmacological coupling, a non-invasive approach that aims to enhance the efficacy and specificity of drug delivery in the brain. This method involves administering a drug, such as Methylphenidate (MPH), concurrently with a behavioral task known to activate the drug's target brain regions (e.g., the prefrontal cortex for cognitive tasks) [31]. The underlying hypothesis is that task-induced increases in local cerebral blood flow will enhance the delivery of the flow-dependent drug to the activated site, thereby improving its therapeutic effect and potentially reducing side effects and required dosage [31]. Preliminary studies in ADHD patients provide support for this concept's feasibility [31].

Future research will likely focus on refining integrated multimodal models, expanding the use of these techniques in naturalistic settings enabled by the portability of fNIRS and EEG, and further exploring the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of NVC monitoring in clinical populations. The continued integration of complementary neuroimaging modalities promises to deepen our understanding of the complex dialogue between neurons and blood vessels in health and disease.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) serves as the central hub for executive functions, including working memory, cognitive control, decision-making, and goal-directed behavior. Studying this region presents unique challenges due to its complex functional topography and intricate connectivity patterns. Within the context of neuroimaging methodologies, electroencephalography (EEG) offers distinct advantages for investigating PFC dynamics, particularly when compared to functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). While fNIRS provides better spatial resolution for surface cortical areas and greater tolerance to movement artifacts, EEG delivers unparalleled temporal resolution in the millisecond range, enabling researchers to capture the rapid neural dynamics that characterize prefrontal information processing [32]. This technical guide examines the ideal use-cases for EEG in PFC research, detailing specific methodologies, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks that leverage EEG's unique capabilities for investigating prefrontal functions.

The fundamental physiological difference between these modalities dictates their optimal application domains. EEG measures the electrical activity generated by synchronized firing of cortical neurons, primarily pyramidal cells, providing a direct window into neuro-electrical dynamics. In contrast, fNIRS monitors cerebral hemodynamic responses by measuring changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin, offering an indirect metabolic marker of neural activity that is delayed by several seconds due to neurovascular coupling [32] [33]. This temporal disparity makes EEG uniquely suited for investigating the rapid neural oscillations and transient event-related potentials (ERPs) that underlie cognitive processes in the PFC, while fNIRS excels in studying sustained cognitive states and localized cortical activation, particularly in naturalistic settings where movement tolerance is required [32] [34].

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of EEG and fNIRS for PFC Studies

| Feature | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond level | Seconds (limited by hemodynamic response) |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited (centimeter-level) | Moderate (better than EEG, limited to cortex) |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface | Outer cortex (~1-2.5 cm deep) |

| Primary Signal Source | Postsynaptic potentials in cortical neurons | Changes in oxygenated/deoxygenated hemoglobin |

| Sensitivity to Motion | High - susceptible to movement artifacts | Low - more tolerant to subject movement |

| Best Use Cases | Fast cognitive tasks, ERP studies, brain-state monitoring | Naturalistic studies, child development, sustained cognitive states |

| Portability | High - lightweight and wireless systems available | High - often used in mobile and wearable formats |

EEG Methodologies for Probing Prefrontal Cortex Function

Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) in Prefrontal Assessment

Event-related potentials (ERPs) represent one of the most powerful EEG methodologies for investigating cognitive processes mediated by the PFC. ERPs are small voltage fluctuations in the EEG that are time-locked to sensory, cognitive, or motor events, providing exquisite temporal resolution for dissecting the rapid neural dynamics of prefrontal information processing [35]. The P300 component, a positive deflection occurring approximately 300 ms after stimulus presentation, has received particular attention as a reliable marker of cognitive function related to attentional resource allocation and working memory updating [35]. Research has demonstrated that both the latency and amplitude of the P300 serve as sensitive indicators of cognitive status, with systematic alterations observed during normal aging and more pronounced changes occurring in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia [35].

The Neurodetector system represents an innovative application of ERP methodology for motor-independent cognitive assessment. This brain-computer interface (BCI) approach utilizes ERPs as a virtual "EEG Switch" that enables cognitive assessment without requiring physical responses, making it particularly valuable for populations with motor impairments [35]. In this paradigm, when a stimulus elicits a recognizable ERP pattern (particularly the P300), the system interprets it as a selection signal, allowing users to perform cognitive tasks without physical movement. Experimental validation with healthy adults has demonstrated that participants can control the EEG Switch significantly above chance level across tasks of varying difficulty, with success rates correlating with task complexity and individual cognitive abilities [35].

Table 2: Key ERP Components for PFC Functional Assessment

| ERP Component | Latency (ms) | Cognitive Correlation | Topographical Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| P300 | 250-500 | Attentional allocation, context updating, working memory | Centroparietal, prefrontal contributions |

| Frontal Negativity | 200-300 | Conflict monitoring, error detection, cognitive control | Mid-frontal |

| Contingent Negative Variation | 500-1000 | Expectancy, preparation, motor planning | Bilateral frontal |

| Error-Related Negativity | 50-150 | Error detection, performance monitoring | Anterior cingulate/frontal midline |

Time-Frequency Analysis of Prefrontal Oscillations

Beyond ERPs, time-frequency analysis of neural oscillations provides a rich framework for investigating PFC function. Distinct frequency bands reflect specific aspects of cognitive processing, with characteristic patterns emerging during different prefrontal-mediated tasks [34]. Frontal-midline theta (4-8 Hz) increases linearly with working memory load, serving as a sensitive indicator of cognitive control demands. Alpha oscillations (8-13 Hz), particularly frontal alpha asymmetry, reliably index emotional valence with 75-85% classification accuracy in affective neuroscience studies [34]. Beta activity (13-30 Hz) maintains current cognitive sets, while gamma oscillations (30-80 Hz) support the binding of distributed neural representations into coherent percepts [34].

Advanced analytical approaches have enabled more precise characterization of these oscillatory patterns. Research using regularized linear discriminant analysis on scalp EEG data has successfully distinguished between mental-rotation tasks and color-perception tasks with 87% decoding accuracy, with dorsal and ventral areas in lateral PFC providing the dominant features that dissociated the two tasks [36]. This finding emphasizes the PFC's functional specificity in processing spatial versus feature-based information and demonstrates the capacity of EEG metrics to decode distinct cognitive states from prefrontal signals.

EEG Microstate Analysis

EEG microstate analysis has emerged as a powerful method for characterizing the neural activity of the whole brain in both spatial and temporal domains, with specific relevance to PFC function. Microstates are transient, spatially stable patterns of brain activity that typically last for 60-120 ms, representing the fundamental building blocks of brain dynamics [37]. Of the four classic microstate topographies (labeled A, B, C, and D), microstate C has been specifically linked to the default mode and executive control networks, primarily involving the bilateral inferior frontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex [37].

Crucial evidence for the causal role of PFC in microstate generation comes from lesion studies. Patients with prefrontal lesions, particularly in the inferior and middle frontal gyrus, show significant abnormalities in the spatial distribution and temporal dynamics of microstate C, including reduced coverage and occurrence, along with altered transition probabilities from other microstate classes [37]. These findings demonstrate a causal link between specific prefrontal regions and microstate C, providing valuable insights into the cortical origins of this dynamic brain network.

Experimental Protocols for Prefrontal EEG Research

Protocol 1: ERP-Based Cognitive Assessment Using the EEG Switch

The Neurodetector protocol implements a motor-independent cognitive assessment system that can be adapted for various PFC research applications [35]:

Equipment Setup:

- EEG recording system with at least 8 channels (Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz, P3, P4, PO7, PO8 recommended)

- Active electrodes with impedance kept below 10 kΩ

- Stimulus presentation monitor

- Comfortable seating in an electrically shielded room

Procedure:

- Participants complete a brief training session to familiarize themselves with the EEG Switch paradigm.

- EEG data are collected during three cognitive tasks of increasing difficulty:

- Simple Attention Task: Participants attend to rare target stimuli amid frequent standard stimuli.

- Working Memory Task: Participants maintain and manipulate information in working memory.

- Executive Function Task: Participants perform complex problem-solving requiring cognitive flexibility.

- For each task, the system presents visual stimuli in a oddball paradigm, with targets occurring with 20% probability.

- Participants use the EEG Switch to make selections by focusing attention on target stimuli.

- EEG is continuously recorded with a sampling rate ≥256 Hz.

Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Bandpass filtering (0.1-30 Hz), artifact removal, epoching (-200 to 800 ms relative to stimulus).

- ERP analysis: Averaging of target versus standard trials, measurement of P300 amplitude and latency.

- Pattern-matching classification: Comparison of single-trial ERPs to template responses using spatial correlation.

- Success rate calculation: Percentage of correct selections via the EEG Switch.

Key Parameters:

- Stimulus duration: 100 ms

- Inter-stimulus interval: 1000-1500 ms (randomized)

- Number of trials: 40-60 per condition

- Performance metric: Task success rate relative to chance level (50%)

Protocol 2: Decoding Spatial and Color Processing in PFC

This protocol enables investigation of dorsal-ventral functional specialization in lateral PFC using multivariate pattern analysis [36]:

Equipment Setup:

- High-density EEG system (64+ channels)

- International 10-10 electrode placement

- Stimulus presentation system

Procedure:

- Participants perform two distinct cognitive tasks in counterbalanced order:

- Mental Rotation Task: Judge whether rotated figures match a target stimulus (spatial processing).

- Color Perception Task: Discriminate subtle color differences (feature processing).

- Each trial begins with a fixation cross (500 ms), followed by stimulus presentation (1500 ms).

- Participants make button-press responses with left/right hands counterbalanced.

- EEG is recorded continuously with sampling rate ≥512 Hz.

Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Filtering (0.5-40 Hz), artifact rejection, epoching (-500 to 1500 ms).

- Feature extraction: Time-frequency decomposition using complex Morlet wavelets.

- Regularized linear discriminant analysis (rLDA) to classify task states.

- Source localization using LORETA or sLORETA to identify PFC subregional contributions.

Key Parameters:

- Trial duration: 2000 ms

- Number of trials: 80 per condition

- Analysis focus: Theta (4-8 Hz) and alpha (8-13 Hz) power in dorsal vs. ventral PFC

- Performance metric: Classification accuracy between task states

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for decoding PFC functional specialization using EEG.

Protocol 3: Microstate Analysis in Prefrontal Lesion Patients

This protocol outlines the investigation of causal PFC contributions to large-scale brain networks using microstate analysis [37]:

Equipment Setup:

- 64-channel EEG system with BioSemi ActiveTwo amplifier or equivalent

- Ag-AgCl pin-type active electrodes mounted on elastic cap

- International 10-10 system placement

Procedure:

- Participants (prefrontal lesion patients and matched controls) are seated comfortably.

- Resting-state EEG is recorded for 10-15 minutes with eyes open.

- Participants fixate on a central cross to minimize eye movements.

- EEG is sampled at 1024 Hz with impedance kept below 20 kΩ.

Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Bandpass filtering (1-30 Hz), downsampling to 256 Hz, artifact removal.

- Microstate analysis:

- Identify global field power peaks.

- Cluster topographic maps into four canonical microstates (A, B, C, D).

- Calculate microstate parameters: duration, occurrence, coverage, transition probabilities.

- Statistical comparison between patient and control groups.

- Correlation of microstate parameters with lesion location and neuropsychological test scores.

Key Parameters:

- Resting-state recording: 10-15 minutes eyes-open

- Microstate classes: A, B, C, D

- Analysis focus: Microstate C parameters (coverage, occurrence, transition probabilities)

- Critical comparison: Prefrontal lesion patients vs. healthy controls

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for PFC EEG Studies

| Item | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System | 64+ channels, active electrodes | Captures detailed spatial patterns of PFC activity |

| ERP Analysis Software | EEGLAB, ERPLAB, BrainVision Analyzer | Preprocessing, artifact removal, ERP quantification |

| Microstate Analysis Toolbox | Microstate EEGLAB plugin | Identifies and analyzes temporal dynamics of brain networks |

| Source Localization Software | sLORETA, BESA, Brainstorm | Estimates cortical generators of scalp-recorded EEG signals |

| Cognitive Task Presentation | Presentation, E-Prime, PsychToolbox | Controls stimulus timing and response collection |

| Pattern Classification Tools | MATLAB with Statistics Toolbox, Python scikit-learn | Implements machine learning for cognitive state decoding |

| fNIRS System (Multimodal) | Compatible with EEG cap, 690-850 nm wavelengths | Provides simultaneous hemodynamic data for multimodal fusion |

Multimodal Integration: EEG with fNIRS for Comprehensive PFC Assessment

The integration of EEG with fNIRS represents a powerful multimodal approach that leverages the complementary strengths of both modalities for comprehensive PFC assessment [33] [38] [39]. This combined methodology enables researchers to capture both the rapid electrophysiological dynamics (via EEG) and the localized hemodynamic responses (via fNIRS) that characterize prefrontal function during cognitive tasks.

Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS studies have demonstrated the value of this integrated approach for investigating cognitive processes. For example, research on intentional memory processing revealed that EEG metrics captured early neural dynamics related to encoding intention (300 ms post-stimulus), while fNIRS reflected more distributed patterns of cognitive engagement during subsequent decision periods [38]. Similarly, studies employing multilayer network analysis have shown that combined EEG-fNIRS approaches outperform unimodal analyses, providing a richer understanding of brain network dynamics during both resting state and task conditions [39].

Figure 2: Multimodal EEG-fNIRS integration workflow for comprehensive PFC assessment.

Practical implementation of simultaneous EEG-fNIRS requires careful consideration of technical factors. Sensor placement compatibility is essential, with both systems often using the international 10-20 system for electrode/optode placement. High-density EEG caps with pre-defined fNIRS-compatible openings or specialized hybrid caps can prevent interference between modalities [32]. Hardware integration may involve synchronized triggering systems or shared clock mechanisms to ensure temporal alignment of data streams. Motion artifacts present particular challenges, necessitating tight but comfortable cap fittings and the application of motion correction algorithms during preprocessing [32] [33].