Framewise Displacement and BOLD Signal: A Comprehensive Guide to Artifacts, Impact on Connectivity, and Mitigation Strategies for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex relationship between framewise displacement (FD) and the BOLD signal in fMRI studies.

Framewise Displacement and BOLD Signal: A Comprehensive Guide to Artifacts, Impact on Connectivity, and Mitigation Strategies for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex relationship between framewise displacement (FD) and the BOLD signal in fMRI studies. It explores the foundational mechanisms by which head motion introduces systematic, temporally-lagged artifacts that can persist for over 20 seconds, profoundly affecting functional connectivity metrics. We detail methodological approaches for quantifying these effects, including novel tools for assessing residual lagged structure and trait-specific motion impact scores. The content covers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for mitigating motion-related artifacts across different populations, with particular attention to clinical and developmental cohorts. Finally, we examine validation frameworks and comparative analyses of correction methodologies, addressing implications for drug development and regulatory qualification of fMRI biomarkers. This resource is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to improve the validity and reproducibility of their fMRI findings.

Understanding the Core Problem: How Motion Creates Systematic BOLD Signal Artifacts

Framewise displacement (FD) has emerged as a critical quantitative metric in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research, serving as both a measure of head motion and a proxy for analyzing associated noise in the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal. This technical guide examines FD's mathematical formulation, its evolution into a central biomarker for data quality control, and its complex relationship with spurious functional connectivity. Within the broader context of BOLD signal research, we demonstrate how FD quantification enables researchers to distinguish neural correlates from motion-induced artifacts, thereby addressing one of the most pervasive confounds in modern neuroimaging. Through synthesis of current methodologies and empirical findings, this review provides a comprehensive framework for implementing FD metrics in research and clinical applications, with particular relevance for drug development professionals targeting neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Head motion presents a formidable challenge for resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), introducing systematic artifacts that compromise data integrity and interpretation [1]. Even "micro" head movements as small as 0.1mm can introduce systematic artifactual differences in functional connectivity metrics, potentially leading to spurious findings in brain-wide association studies [2] [1]. These motion-induced artifacts are particularly problematic in clinical populations and developmental studies where head movement may covary with variables of interest.

Framewise displacement has evolved from a simple motion summary statistic to a critical noise proxy that captures complex relationships between physical movement and BOLD signal artifacts. The profound impact of motion on fMRI data quality stems from the fundamental physics of MRI acquisition: head movement during scans disrupts the establishment of magnetic gradients and subsequent readout of the BOLD signal, effects that persist despite spatial realignment and regression of motion estimates [3]. This technical foundation establishes FD as an essential tool for any researcher working with fMRI data, particularly in the context of drug development where distinguishing true neurophysiological effects from motion-related confounds is paramount.

Mathematical Definition and Calculation of Framewise Displacement

Core Formula and Parameters

Framewise displacement quantifies the total head movement between consecutive fMRI volumes by combining translational and rotational realignment parameters (RPs) into a single scalar value. The standard FD formula, as defined by Power et al. (2012), is calculated for each timepoint (i) as follows:

Where:

- ( \Delta xi = x{i-1} - x_i ) (and similarly for (y) and (z))

- (x, y, z) represent translational displacements in millimeters

- (\alpha, \beta, \gamma) represent rotational displacements in radians

- The rotational displacements are typically converted to millimeters by measuring displacement on a sphere of radius 50 mm (default) [4] [5]

Implementation Considerations

Practical implementation of FD calculation requires attention to several technical considerations. The rotation units may be specified in degrees or radians, while translational units are typically millimeters. The critical parameter of brain_radius (often set to 50mm) enables the conversion of rotational displacements to spatial measurements on the surface of a sphere representing typical head size [5]. Advanced implementations may include detrending options using discrete cosine transform (DCT) bases to remove slow drifts from realignment parameters before FD computation [4].

Table 1: Parameters for FD Calculation

| Parameter | Description | Default Values | Alternative Options |

|---|---|---|---|

trans_units |

Translational units | "mm" | "cm", "in" |

rot_units |

Rotational units | "deg" | "rad", "mm", "cm", "in" |

brain_radius |

Radius for rotation conversion | 50 mm | User-defined value |

detrend |

Remove slow drifts | FALSE | TRUE (uses 4 DCT bases) |

cutoff |

Outlier flag threshold | 0.3 mm | Study-dependent values |

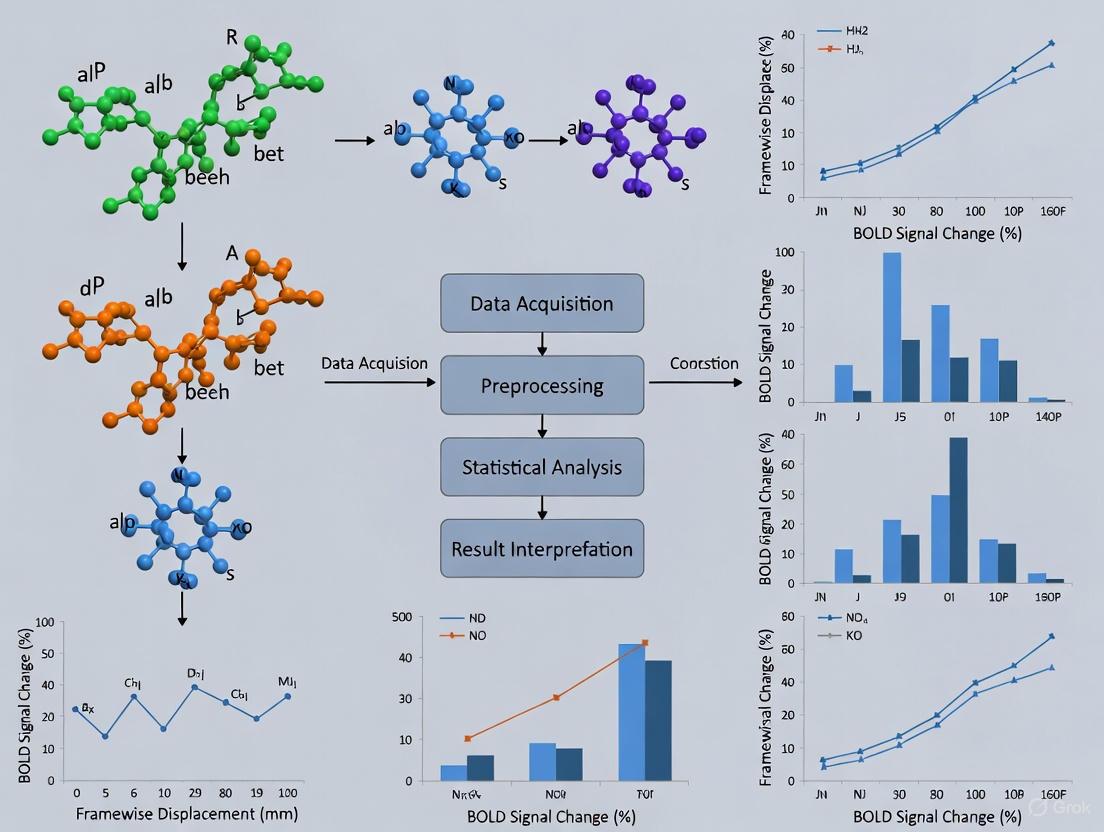

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for deriving FD from realignment parameters:

FD as a Proxy for BOLD Signal Artifacts

Motion-Artifact Relationships in Functional Connectivity

Research has established that FD serves as a powerful proxy measure for understanding motion-induced artifacts in BOLD signals. Power et al. (2012) demonstrated that subject motion produces substantial changes in resting-state functional connectivity MRI timecourses despite spatial registration and motion parameter regression [3]. These changes manifest as systematic correlation structures throughout the brain, with motion decreasing long-distance correlations while increasing short-distance correlations [3].

The relationship between FD and BOLD signal artifacts exhibits temporal persistence that extends far beyond the immediate motion event. Siegel et al. (2017) identified that framewise displacements—both large and very small—were followed by structured, prolonged, and global changes in the BOLD signal that persist for 20-30 seconds following the initial displacement [6] [7]. This lagged BOLD structure varies systematically according to the magnitude of the preceding displacement and independently predicts considerable variance in the global cortical signal (30-40% in some subjects) [7].

Spatial Patterns of Motion Artifacts

The impact of motion on BOLD signals demonstrates regional variation across the brain. Yan et al. (2013) conducted a comprehensive voxel-based examination revealing that positive motion-BOLD relationships were most prominent in primary and supplementary motor areas, particularly in low-motion datasets [1]. Conversely, negative motion-BOLD relationships were most prominent in prefrontal regions and expanded throughout the brain in high-motion datasets [1]. This spatial patterning helps explain why motion artifacts create systematic biases in functional connectivity analyses.

Table 2: Motion-BOLD Signal Relationships Across Brain Regions

| Brain Region | Motion-BOLD Relationship | Conditions of Prominence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary/Supplementary Motor Areas | Positive correlation | Low-motion datasets | Potential neural origins |

| Prefrontal Regions | Negative correlation | All datasets, expands in high motion | Likely motion artifact |

| Long-distance Connections | Decreased correlation | All motion levels | Systematic artifact |

| Short-distance Connections | Increased correlation | All motion levels | Systematic artifact |

The conceptual relationship between motion, FD, and BOLD signal artifacts can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Protocols for FD Validation and Application

Assessing Motion Impact with SHAMAN

Recent methodological advances provide sophisticated approaches for quantifying motion's impact on specific trait-FC relationships. The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) framework, introduced in a 2025 Nature Communications paper, assigns a motion impact score to specific trait-FC relationships [2]. This method capitalizes on the relative stability of traits over time by measuring differences in correlation structure between split high- and low-motion halves of each participant's fMRI timeseries.

The SHAMAN protocol operates on the principle that when trait-FC effects are independent of motion, the difference between high- and low-motion halves will be non-significant because traits are stable over time [2]. A significant difference indicates that state-dependent differences in motion impact the trait's connectivity. The direction of the motion impact score relative to the trait-FC effect distinguishes between motion overestimation (aligned direction) and motion underestimation (opposite direction) of trait-FC effects [2].

Lagged Artifact Analysis Protocol

Siegel et al. (2017) developed a method for quantifying temporally extended noise artifact using a peri-event time histogram approach [6] [7]. This protocol involves:

- Identifying displacement events: Categorizing framewise displacements by magnitude ranges

- Epoch extraction: Extracting BOLD signal epochs following all similar displacement magnitudes

- Cross-epoch averaging: Computing average BOLD changes across all epochs with similar preceding FD values

- Variance explanation: Modeling the cumulative effects of this artifact across entire runs

This method revealed that residual lagged structure following displacements explains substantial variance in global cortical signals and affects mean functional connectivity estimates, even after strict censoring [7]. The protocol is particularly valuable for identifying artifacts that persist despite standard preprocessing pipelines.

Quality Control Procedures in Multi-Site Studies

Birn et al. (2023) outlined comprehensive quality control procedures for resting-state fMRI that incorporate FD metrics at multiple processing stages [8]. Their protocol includes:

- Real-time monitoring: Assessing data quality while the subject is still in the scanner

- Multi-stage assessment: Evaluating quality at multiple processing pipeline stages

- Threshold optimization: Testing different motion censoring thresholds (0.2, 0.4, 1.0 mm)

- Comprehensive metrics: Combining qualitative inspection with quantitative FD measures

This approach emphasizes that QC procedures should monitor not only the original and processed data quality but also the accuracy and consistency of acquisition parameters across sites [8], a critical consideration for multi-site clinical trials in drug development.

Table 3: Essential Tools for FD Calculation and Motion Denoising Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIscrub (R package) | Calculate FD and other motion metrics | FD(X) function with detrending options and outlier flagging [4] [5] |

| SHAMAN Framework | Assign motion impact scores to trait-FC relationships | Distinguishes overestimation vs. underestimation of effects [2] |

| Peri-Event Histogram Tool | Quantify lagged BOLD structure post-displacement | MATLAB script for visualizing displacement-linked artifacts [6] [7] |

| AFNI Processing Suite | Comprehensive fMRI processing with QC integration | 3dvolreg for motion realignment; afni_proc.py for automated processing [8] |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | Default denoising for large datasets (e.g., ABCD Study) | Includes global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion regression [2] |

| Framewise Censoring | Remove motion-contaminated volumes | Exclusion of timepoints exceeding FD threshold (e.g., 0.2mm) [1] [8] |

Current Challenges and Methodological Considerations

Limitations of FD Metrics

Despite its widespread adoption, FD has several methodological limitations as a motion quantification tool. The standard FD formula treats translational and rotational parameters equivalently in the summation, though their actual impact on BOLD signals may differ [4]. Additionally, FD summary statistics may not distinguish between qualitatively different types of subject movement—a subject with one large movement versus a subject with frequent small movements may have similar FD values despite different artifact profiles [3].

Another significant challenge is that residual motion artifacts persist even after aggressive denoising procedures. In the ABCD Study, after denoising with ABCD-BIDS (including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, and motion parameter regression), 23% of signal variance was still explained by head motion [2]. Furthermore, the motion-FC effect matrix showed a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix, indicating that connection strength was systematically weaker in participants who moved more [2].

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

Recent research has focused on developing novel denoising approaches for multiband resting-state functional connectivity fMRI data. Faghiri et al. (2022) proposed new quantitative metrics agnostic to QC-FC correlations for evaluating motion denoising pipelines, addressing limitations of common evaluation assumptions [9]. Their work enables dataset-specific optimization of volume censoring parameters prior to final analysis.

The complex relationship between preprocessing choices and statistical artifacts remains an active research area. A 2025 NeuroImage review highlighted that standard rsfMRI preprocessing—particularly band-pass filters (0.009–0.08 Hz and 0.01–0.10 Hz)—introduce biases that increase correlation estimates between independent time series [10]. These preprocessing-induced distortions can lead to inflated statistical significance and increased false positives, complicating the interpretation of motion-corrected data.

Framewise displacement has evolved from a simple summary statistic to a critical noise proxy that enables researchers to quantify and mitigate one of the most significant confounds in fMRI research. Its mathematical formulation provides a practical tool for data quality assessment, while its relationship with lagged BOLD signal artifacts reveals the complex interplay between head motion and neuroimaging metrics. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorous implementation of FD metrics—within appropriate methodological frameworks that account for its limitations—remains essential for distinguishing true neurophysiological effects from motion-induced artifacts. As fMRI continues to advance as a tool for understanding brain function and evaluating therapeutic interventions, framewise displacement will maintain its crucial role in ensuring the validity and reproducibility of functional connectivity findings.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research is fundamentally predicated on the ability to separate neuronal-related blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals from noise. However, residual noise remains problematic—particularly for functional connectivity analyses where findings can be spuriously influenced by noise sources that covary with individual differences [6] [7]. Among these nuisance factors, head motion represents a particularly formidable challenge, with recent evidence demonstrating that even "micro" head movements as small as 0.1mm can introduce systematic artifactual differences in fMRI metrics [1]. The relationship between framewise displacement (FD)—an index of frame-to-frame head movement derived from image realignment estimates—and the subsequent BOLD response represents a critical area of investigation for improving the validity of fMRI findings.

This technical guide examines the characteristic 20-30 second lagged BOLD responses that follow framewise displacements, a consistent spatiotemporal signature of motion artifacts observed across multiple datasets and studies [6] [7]. Beyond merely documenting this phenomenon, we explore its underlying mechanisms, quantitative properties, and implications for functional connectivity research. Understanding this structured residual noise is essential both for assessing how such noise might influence conclusions and for developing more effective cleanup methods, particularly in studies where motion may covary with variables of interest such as clinical status, age, or other individual differences [6] [1].

Core Phenomenon: The Lagged BOLD Signature

Characteristic Temporal Pattern

Research has consistently revealed that framewise displacements are followed by structured, prolonged changes in the global cortical BOLD signal that persist for extended epochs of 20-30 seconds following the initial displacement [6] [7]. This lagged BOLD structure demonstrates a clear dose-response relationship with the magnitude of the preceding displacement, with larger displacements predicting more pronounced signal changes [7]. The persistence of this response across tens of seconds indicates that motion effects are not transient phenomena but rather represent extended perturbations of the BOLD signal.

Notably, this characteristic pattern remains robust across datasets and is observable within many individuals' data. The consistency of this finding across independent datasets collected with different parameters (e.g., TR = 813 ms vs. TR = 720 ms) suggests this represents a fundamental property of the relationship between motion and the BOLD signal rather than a methodology-specific artifact [6]. This residual lagged structure persists despite the application of numerous common preprocessing methods, including some state-of-the-art practices [7].

Quantitative Impact on BOLD Variance

The practical significance of this motion-related artifact becomes evident when examining its quantitative impact on signal variance:

Table 1: Variance Explained by Lagged BOLD Structure Following Framewise Displacements

| Metric | Impact | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Global Cortical Signal | 30-40% variance explained in some subjects | Independently predicted considerable variance [6] [7] |

| Functional Connectivity Estimates | Varied as function of preceding displacements | Effects persisted even after strict censoring [6] |

| Spatial Distribution | Widespread cortical effects | Prominent in global cortical (gray matter) signal [6] |

This substantial explanatory power demonstrates that motion-related artifacts are not merely statistical nuisances but rather represent major sources of signal variance that can potentially dominate the BOLD timecourse in certain individuals [6] [7].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Core Assessment Method: Peri-Event Time Histogram Construction

The primary method for identifying lagged BOLD structure involves a construction similar to a peri-event time histogram that assesses whether common structure exists in BOLD epochs immediately following similar instances of nuisance signals [6] [7]. The experimental workflow for this analytical approach can be visualized as follows:

The specific methodological steps include:

Framewise Displacement Calculation: Compute FD from the three translation and three rotation parameters obtained during image realignment [1].

Event Categorization: Identify all instances of framewise displacements within specific magnitude ranges, including both large movements and those falling within typical data inclusion thresholds (e.g., FD < 0.2mm) [6] [7].

Epoch Extraction: Extract the mean cortical BOLD signal for a 20-30 second window following each displacement event [7].

Temporal Alignment and Averaging: Align all epochs by their displacement onset and average across events within the same magnitude range to reveal consistent patterns [6].

This approach effectively extends the logic of standard preprocessing, wherein any systematic relationship between the BOLD signal and nuisance signals of no interest is considered noise that should be removed [6] [7].

Dataset Specifications

Table 2: Representative Dataset Parameters for Lagged Artifact Research

| Parameter | IU Dataset | Human Connectome Project (HCP) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 51 participants (after quality exclusion) | Publicly available dataset [6] |

| Diagnostic Groups | Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and neurotypical controls | Not specified in context |

| TR | 813 ms | 720 ms |

| Session Design | Two ~16-minute resting state scans per session | Standard HCP protocol |

| Motion Constraints | No a priori exclusion for most participants | Standard HQC quality control |

The consistency of findings across these independent datasets with slightly different acquisition parameters strengthens the evidence for this being a fundamental property of the BOLD signal rather than a dataset-specific artifact [6].

Respiratory Contributions

Exploratory analyses of physiological traces available for subset of scans suggest the involvement of respiratory processes as one likely mechanism underlying displacement-linked structure [6] [7]. Several lines of evidence support this connection:

- Similar Lagged Patterns: Parallel analyses reveal similar patterns of residual lagged BOLD structure following respiratory fluctuations [7]

- Covariance with Motion: Respiratory and framewise displacement traces themselves are related, suggesting FD may partially index physiological noise [6]

- Physiological Plausibility: Respiration produces structured noise at both short timescales (chest movements modulating magnetic field) and longer lags (vasodilatory effects of arterial CO2 changes) [6]

Respiratory effects can modulate the BOLD signal through multiple pathways, including changes in arterial CO2 concentration that trigger vasodilation and consequent alterations in cerebral blood flow and volume [6] [11]. These CO2-mediated effects operate through well-established physiological pathways that influence neurovascular coupling.

Neurovascular Coupling and BOLD Origins

To understand motion-related artifacts, it is essential to recognize that the BOLD signal is an indirect reflection of neuronal activity, primarily determined by changes in paramagnetic deoxygenated hemoglobin resulting from combinations of changes in oxygen metabolism, cerebral blood flow, and volume [12]. The classical BOLD response to stimulus begins within approximately 500 ms and peaks 3-5 seconds after stimulus onset, with more complex dynamics for prolonged stimuli [11].

The relationship between framewise displacement and the BOLD signal can be conceptualized through the following physiological pathways:

The vascular origin of these artifacts is further supported by evidence that a significant component of the spatiotemporally structured BOLD signal reflects vascular anatomy rather than neuronal activity [13]. This vascular structure accounts for approximately 30% of the signal variance on average, representing a profound impact on fMRI data [13].

Implications for Functional Connectivity

Effects on Connectivity Metrics

The lagged BOLD structure following framewise displacements has demonstrable consequences for functional connectivity estimates:

- Systematic Bias: Mean functional connectivity estimates vary as a function of displacements occurring many seconds in the past, even after strict censoring procedures [6] [7]

- Distance-Dependent Effects: Motion artifacts lead to distance-dependent biases in inferred signal correlations, typically inflating short-range connectivity while weakening long-range connectivity [1] [14]

- Spurious Group Differences: When motion covaries with individual differences of interest (e.g., clinical status, age), residual motion artifacts can produce spurious findings of group differences [6] [1]

These effects pose particular challenges for studies comparing groups with inherently different motion characteristics, such as children vs. adults, clinical populations vs. controls, or studies of developmental and pathological processes [1].

Mitigation Strategies and Efficacy

Table 3: Motion Artifact Mitigation Strategies and Efficacy Against Lagged Structure

| Method | Approach | Effect on Lagged Structure | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Signal Regression | Regression of global BOLD signal | Largely attenuates artifactual structure [6] [7] | Potential removal of neural signal, controversy in field |

| aCompCor | PCA-based noise estimation from WM/CSF | More effective than mean signal regression [14] | Enhanced specificity of functional connectivity |

| Structured Matrix Completion | Low-rank matrix completion to recover censored data | Reduces motion effects in connectivity matrices [15] [16] | Computational complexity, memory demands |

| Censoring ("Scrubbing") | Removal of high-motion volumes | Limited efficacy alone for lagged structure [6] | Data loss, temporal discontinuity |

| Higher-Order Motion Regression | Expanded motion parameter models | Diminishes but does not eliminate artifacts [1] | Residual artifact remains regardless of model order |

Current evidence suggests that combining multiple approaches (e.g., modeling with expanded motion parameters together with censoring) brings about the greatest reduction in motion-induced artifact [1]. However, residual relationships between motion and functional connectivity metrics often remain, underscoring the need to include motion as a covariate in group-level analyses [1].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methodological Solutions

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Lagged Artifact Investigation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Index of frame-to-frame head movement | Available in all fMRI datasets; serves as primary nuisance signal [6] [7] |

| Peri-Event Histogram Script | MATLAB-based tool for visualizing lagged structure | Quality assessment; generalizable to any nuisance signal [6] [7] |

| Physiological Recordings | Respiratory belt, pulse oximeter measurements | Direct assessment of physiological contributions to artifacts [6] |

| aCompCor | PCA-based noise estimation from white matter and CSF | Enhanced motion artifact reduction compared to mean signal regression [14] |

| Structured Low-Rank Matrix Completion | Advanced matrix completion for censored data | Motion compensation with slice-time correction [15] |

| Global Signal Regression | Removal of global BOLD signal | Effective attenuation of lagged motion-related structure [6] [7] |

This methodological toolkit enables researchers to both identify the characteristic lagged artifacts in their own data and implement strategies to mitigate their impact on functional connectivity findings.

The characteristic 20-30 second lagged BOLD responses following framewise displacements represent a fundamental spatiotemporal signature of motion artifacts in fMRI data. This consistent pattern, observable across diverse datasets and persisting despite common preprocessing approaches, independently explains substantial variance in the global cortical signal and systematically influences functional connectivity estimates. The physiological basis of these artifacts appears to involve both direct physical effects of head movement and more complex physiological processes, particularly respiration and consequent CO2-mediated vascular effects.

For researchers, particularly those investigating individual differences where motion may covary with variables of interest, these findings highlight the critical importance of both assessing data for these characteristic artifacts and implementing appropriate mitigation strategies. The available evidence supports the use of specialized quality assessment tools, combined preprocessing approaches, and appropriate statistical controls at the group level to minimize the potential for spurious conclusions resulting from this structured residual noise. Future methodological developments that more specifically target these lagged relationships may further enhance our ability to separate motion-related artifacts from neural signals of interest in fMRI research.

Analyses of functional connectivity MRI (fcMRI) are predicated on the idea that signals of interest reflecting neural connectivity can be accurately separated from non-neural noise [6]. Subject motion is a well-established source of such noise, fundamentally disrupting the magnetic gradients essential for BOLD signal acquisition [3]. Despite standard countermeasures like spatial realignment and regression of motion parameters, systematic artifacts persist in the data. This paper examines a central and spurious phenomenon: the tendency of subject motion to artificially decrease long-distance correlations while simultaneously increasing short-distance correlations in functional connectivity networks [3]. This effect represents a form of colored noise that can obscure genuine patterns of brain organization and create spurious group differences in individual difference studies [6] [3]. Understanding this artifact is particularly critical when studying populations prone to greater movement, such as pediatric or clinical cohorts, where motion can systematically covary with the variables of interest [3]. Framing this within broader research on framewise displacement and the BOLD signal, we explore the nature of this artifact, its quantitative properties, the methodologies for its identification, and potential mitigation strategies.

Core Artifact: Characterization and Quantitative Data

The motion-induced artifact manifests as a structured change in correlation patterns across the brain. The underlying mechanism involves a complex interplay between physical head displacement and its prolonged, lagged effects on the BOLD signal.

Systematic Alteration of Correlation Patterns

The primary finding is that subject motion introduces a systematic bias in functional connectivity maps. The analysis of multiple cohorts has consistently shown that even after standard preprocessing, including spatial registration and regression of motion estimates, the inclusion of motion-contaminated data leads to two key effects:

- Weakening of long-distance correlations: Connections between widely separated brain regions, particularly those spanning different hemispheres or lobes, show spuriously reduced correlation strength [3].

- Strengthening of short-distance correlations: Connections between geographically proximate brain regions exhibit artificially inflated correlation coefficients [3].

This pattern is not random but is directly linked to the amplitude and timing of head movements.

Quantitative Profile of the Artifact

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from foundational studies that documented the systematic effects of motion on functional connectivity:

Table 1: Quantitative Findings on Motion-Related Artifacts in fcMRI

| Metric | Description | Value / Magnitude | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FD Threshold for Lagged Structure | Structurally altered BOLD signals were observed following framewise displacements of all magnitudes, including very small movements within typical inclusion standards. | Observable from very small FD (>0.1 mm) | [6] |

| Duration of Lagged BOLD Effect | The prolonged, structured change in global BOLD signal following a framewise displacement. | 20–30 seconds | [6] [7] |

| Variance Explained in Global Signal | The variance in the global cortical BOLD signal independently predicted by the modeled lagged structure following displacements. | 30–40% (in some subjects) | [6] [7] |

| Effect on Correlation Strength | Motion increases short-distance correlations and decreases long-distance correlations, altering the apparent network topology. | Systematic and significant changes | [3] [17] |

| Reduction in RMS Motion from Censoring | Reduction in root mean square (RMS) motion after applying framewise censoring ("scrubbing") to data. | Example: Cohort 1: 0.51 mm to 0.41 mm | [3] |

These quantitative effects demonstrate that the artifact is substantial, prolonged, and not adequately addressed by standard preprocessing pipelines.

Relationship to Framewise Displacement and Broader BOLD Signal Research

Framewise displacement (FD) serves as a practical index for investigating this artifact. FD is derived from image realignment parameters and represents the frame-to-frame head movement [6]. Its utility stems from two factors:

- Universal Availability: Unlike physiological recordings (e.g., respiratory belts), FD can be calculated for any fMRI dataset [6].

- Multifactorial Nature: FD traces likely reflect numerous noise sources beyond pure head motion, including physiological noise like respiration, especially in high-temporal-resolution multiband fMRI data [6] [7].

Research reveals a temporally-lagged relationship between FD and the BOLD signal. Using a peri-event time histogram approach, studies show that a framewise displacement—even a small one—is followed by a structured, global change in the BOLD signal that persists for tens of seconds [6] [7]. This lagged structure independently predicts a significant portion of variance in the global signal and causes mean functional connectivity estimates to vary as a function of displacements occurring many seconds in the past [7]. Furthermore, respiratory fluctuations co-vary with FD and produce similar patterns of lagged BOLD structure, implicating respiration as one likely physiological mechanism underlying this artifact [6] [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To systematically study and mitigate this artifact, researchers have developed specific protocols for quantification and quality control.

Protocol 1: Quantifying Lagged BOLD Structure Following Nuisance Signals

This protocol, designed to reveal residual temporally-extended noise, uses an approach analogous to a peri-event time histogram [6] [7].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Data Input: Begin with preprocessed BOLD data and a concurrent nuisance regressor time series, most commonly the framewise displacement (FD) trace [6] [7].

- Epoch Identification: Identify every time point in the scan where the nuisance signal (FD) occurs. This can include all events or can be restricted to events within specific magnitude ranges [6].

- Epoch Segmentation: For each identified event, extract an epoch of the global mean BOLD signal (or signals from specific regions) spanning a time window from several seconds before to 20-30 seconds after the event [6] [7].

- Epoch Sorting & Binning: Sort all the extracted epochs into bins based on the magnitude of the nuisance signal that initiated them (e.g., small, medium, and large FD ranges) [6].

- Averaging & Analysis: Average the BOLD epochs within each magnitude bin. The resulting average time series reveals any systematic, lagged BOLD structure that follows the nuisance signal. The consistency of this pattern across datasets allows for creating a model of the artifact that can be applied to new data [6] [7].

Protocol 2: Framewise Censoring for Motion Artifact Mitigation

This protocol describes a "scrubbing" method to reduce motion-related effects by removing severely motion-contaminated frames from the analysis [3].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Parameter Calculation: From the volume realignment parameters, compute two frame-wise indices of data quality:

- Thresholding & Flagging: Flag individual frames as suspect based on these indices. A common approach is to flag any frame where FD exceeds a threshold (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mm) [3]. More nuanced approaches can also flag frames where DVARS exceeds a threshold.

- Temporal Padding: To account for the temporally smeared effect of motion, it is also recommended to flag one or more frames immediately preceding and following the identified bad frame [3].

- Analysis with Censored Data: Perform the functional connectivity analysis (e.g., correlation calculation between regions) using only the frames that were not flagged. This excludes the most severely contaminated data points from the correlation estimates [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials, tools, and methodological solutions essential for research in this domain.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Motion Artifacts in fcMRI

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | A scalar index derived from realignment parameters, quantifying volume-to-volume head movement. | Serves as a primary, universally available nuisance regressor and event trigger for quantifying motion-related artifact [6] [3]. |

| Global Signal Regression (GSR) | A preprocessing step that removes the mean signal across the entire brain from each voxel's time series. | Shown to largely attenuate the observed lagged structure following displacements in both the BOLD signal and functional connectivity, though its use remains debated [6] [7]. |

| Framewise Censoring ("Scrubbing") | The process of removing (censoring) individual time points from analysis based on FD and DVARS thresholds. | A direct method to mitigate the influence of high-motion frames, leading to reduced short-distance and increased long-distance correlations [3]. |

| Physiological Recordings | Concurrent acquisition of respiratory and cardiac cycles during fMRI scans using a belt and pulse oximeter. | Allows for direct modeling of physiological noise (e.g., RETROICOR) and investigation of its relationship with FD and BOLD artifacts [6]. |

| Peri-Event Time Histogram Method | An analysis technique that aligns and averages BOLD signal epochs following instances of a nuisance signal. | A core tool for visualizing and quantifying the magnitude and duration of residual lagged BOLD structure associated with motion or other noise sources [6] [7]. |

| High-Temporal-Resolution fMRI | Acquisition sequences (e.g., multiband) with TRs below 1 second. | Provides better sampling of noise dynamics and can make FD traces more sensitive to physiological fluctuations, aiding in artifact characterization [6]. |

Discussion and Synthesis

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that subject motion introduces a spurious spatial structure in functional connectivity matrices, characterized by artificially inflated short-distance correlations and diminished long-distance correlations. This artifact is not fully countered by standard volume realignment and motion regression techniques [3]. The artifact's roots extend beyond simple head displacement to include complex, lagged physiological processes, with respiration being a key candidate [6] [7]. The persistence of this structured noise for 20-30 seconds after even minor movements means it can profoundly influence connectivity estimates, especially in studies where groups differ in average motion levels.

Mitigation strategies exist on a spectrum. Framewise censoring directly removes contaminated data, effectively reducing the artifact and "strengthening" long-distance connections that were previously suppressed [3]. Global signal regression also attenuates the artifact but remains controversial due to concerns about introducing other biases [6] [7]. The choice of method depends on the research question and the severity of the motion contamination. Ultimately, these findings highlight the necessity for rigorous motion control and quality assessment in all fcMRI studies and suggest a need to critically revisit previous work where motion may not have been adequately controlled, potentially leading to spurious conclusions [3].

Framewise displacement (FD), an index of frame-to-frame head movement derived from image realignment, is a critical source of artifact in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [1]. Even micromovements as small as 0.1mm can introduce systematic, artifactual differences in resting-state fMRI (R-fMRI) metrics between individuals and groups [1]. However, the impact of these movements is not uniform across the brain; it exhibits distinct regional patterns. Understanding this regional vulnerability—whereby the relationship between motion and the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal varies significantly across different brain areas—is essential for developing targeted noise correction methods and avoiding spurious findings in functional connectomics [1]. This guide synthesizes current research to detail the topography, mechanisms, and methodological implications of these variable motion-BOLD relationships, framing them within the broader context of fMRI research aimed at disentangling neural signals from motion-induced artifact.

Regional Patterns of Motion-BOLD Relationships

Topography of Positive and Negative Correlations

The relationship between head motion and the BOLD signal is spatially heterogeneous. Research has consistently identified two primary types of motion-BOLD relationships, which are regionally specific and can be differentially affected by the overall degree of head motion in a dataset.

Table 1: Regional Vulnerability to Motion-BOLD Relationships

| Brain Region | Motion-BOLD Relationship | Context/Dataset Characteristics | Proposed Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary & Supplementary Motor Areas | Positive Correlation [1] | Most prominent in low-motion datasets [1] | Potential reflection of neural origins related to movement planning or execution [1] |

| Prefrontal Regions | Negative Correlation [1] | Most prominent in low-motion datasets [1] | Likely artifactual origin [1] |

| Widespread Cortical Areas | Negative Correlation [1] | Expands throughout the brain in high-motion datasets (e.g., children) [1] | Artifactual, potentially linked to motion-induced spin history effects and magnetic field inhomogeneities [1] |

| Default Mode & Frontoparietal Networks | Altered Fractal Dynamics (Lower Hurst exponent during movie-watching) [18] | Naturalistic viewing conditions (movie) vs. rest [18] | Distinct neural processing demands in higher-order associative networks [18] |

| Visual, Somatomotor, Dorsal Attention Networks | Altered Fractal Dynamics (Higher Hurst exponent during movie-watching) [18] | Naturalistic viewing conditions (movie) vs. rest [18] | Stimulus-driven neural processing [18] |

These regional relationships are not merely transient. Framewise displacements can induce structured, global changes in the BOLD signal that persist for tens of seconds (20-30 seconds) after the initial movement [6] [7]. This lagged artifact can explain a substantial portion of variance in the global cortical signal—as much as 30-40% in some subjects—and can systematically influence functional connectivity estimates, even after strict censoring of high-motion volumes [6] [7].

Underlying Mechanisms and Contributing Factors

The observed regional vulnerability arises from a confluence of factors, which can be conceptualized as a network of interacting causes and consequences.

The diagram above illustrates the primary mechanisms. Negative motion-BOLD relationships are largely considered artifactual, stemming from technical factors like spin history effects, partial voluming, and magnetic field inhomogeneities introduced by movement [1]. Furthermore, motion is often correlated with respiration, which itself can produce widespread, lagged changes in the BOLD signal due to CO2-related vasodilation, complicating the disentanglement of motion and physiological noise [6] [7]. In contrast, positive relationships observed in motor areas may, at least partially, reflect genuine neural activity associated with the generation of head motion itself [1].

Methodological Protocols for Investigation and Mitigation

Experimental Approach for Quantifying Lagged Artifacts

A powerful method for identifying residual, motion-related structure in the BOLD signal involves constructing a peri-event histogram around instances of framewise displacement.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Motion-BOLD Research

| Research Tool / Metric | Function/Description | Relevance to Motion-BOLD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Summarizes frame-to-frame head movement from volume realignment [1]. | Primary regressor of interest for quantifying subject motion [1] [6]. |

| Peri-Event Time Histogram | Averages BOLD signal epochs following similar-magnitude FD events [6] [7]. | Core tool for visualizing and quantifying temporally-lagged motion artifacts [6] [7]. |

| Global Signal Regression (GSR) | Nuisance regression technique that removes the global mean BOLD signal [1] [6]. | Effectively attenuates lagged motion artifact and related functional connectivity distortions [1] [6] [7]. |

| scrubbing | Removal or regression of motion-contaminated volumes (e.g., FD > 0.2 mm) [1]. | Reduces artifact from high-motion time points; best used in combination with regression [1]. |

| FIX (FMRIB's ICA-based Xnoiseifier) | Classifies and removes noise components from fMRI data via independent component analysis [19]. | Advanced denoising to mitigate motion and other artifacts after standard preprocessing [19]. |

| High-Order Motion Regression (e.g., 24-param) | Models cumulative effects of motion on spin history beyond basic realignment [1]. | Reduces residual motion artifact, though some structure may remain [1]. |

The experimental workflow for this analysis is systematic. First, preprocessing is performed, which may include various levels of motion correction (e.g., volume realignment, tissue-based nuisance regression, ICA-based denoising like FIX). Second, the Framewise Displacement (FD) time series is calculated for the entire scan. Third, BOLD signal epochs are extracted from the preprocessed data. These epochs span a window (e.g., from -5 to +30 seconds) surrounding every time point where the FD falls within a specific, pre-defined range (e.g., 0.1-0.2 mm, 0.2-0.3 mm, etc.). Finally, the residual lagged structure is quantified by averaging all BOLD epochs within each FD range, revealing the systematic, time-locked signal change that follows head movements of a given magnitude [6] [7].

Mitigation Strategies and Efficacy

No single method completely eliminates motion artifacts, necessitating a multi-pronged approach. The following strategies are commonly employed, with varying efficacy:

- Modeling-Based Regression: Regressing out the 6 realignment parameters (and their derivatives) is standard but inadequate for removing micromovement effects. Higher-order models (e.g., 24- or 36-parameter models) that account for the spin excitation history show improved performance, though residual artifact often persists [1].

- scrubbing: Removing volumes with FD exceeding a threshold (e.g., > 0.2 mm), along with adjacent volumes, is effective at reducing artifact, particularly negative motion-BOLD correlations [1]. However, it can lead to significant data loss and complicates frequency-based analyses.

- Global Signal Regression (GSR): GSR is notably effective at attenuating lagged motion artifact and reducing spurious motion-related differences in functional connectivity [1] [6] [7]. Its use, however, remains debated due to potential introduction of other statistical biases.

- Combined Approaches: The most effective strategy is a combination of scrubbing and high-order motion parameter regression within a single integrated model [1]. Furthermore, including a summary measure of individual motion (e.g., mean FD) as a nuisance covariate in group-level analyses is essential to account for residual variance shared by motion and the variables of interest [1].

The relationship between framewise displacement and the BOLD signal is fundamentally non-uniform, exhibiting distinct regional vulnerability. Positive correlations in motor areas and negative correlations in prefrontal and other association regions underscore the complex interplay between neural and artifactual sources of variance. The discovery of prolonged, lagged artifact further highlights that motion's influence extends far beyond the moment of movement itself, posing a significant threat to the validity of functional connectivity and individual differences research. A comprehensive understanding of these regional and temporal patterns, combined with rigorous mitigation protocols that extend beyond standard preprocessing, is paramount for advancing the precision and reliability of fMRI-based biomarkers in basic and clinical neuroscience.

Framewise displacement (FD), a common metric for head motion in fMRI studies, exhibits a complex and temporally extended relationship with the BOLD signal that can confound functional connectivity findings. A growing body of evidence indicates that respiration serves as a primary physiological mechanism underlying this relationship, with respiratory fluctuations contributing to both head motion and BOLD signal changes through multiple pathways. This technical review synthesizes current research on respiration as a key confound, detailing the physiological basis, methodological approaches for quantification, and preprocessing strategies for mitigation. We present quantitative data demonstrating the substantial variance explained by respiration-linked artifacts and provide practical guidance for researchers investigating the relationship between FD and BOLD signal changes.

In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research, framewise displacement (FD) has traditionally been treated as an indicator of head motion, with the assumption that its relationship with the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal primarily reflects physical movement artifacts. However, emerging evidence challenges this simplistic view, revealing that FD traces capture not only head motion but also physiological noise sources, particularly respiratory fluctuations [6]. This recognition fundamentally shifts our understanding of the relationship between FD and BOLD signal changes.

Respiration influences the BOLD signal through multiple mechanisms operating at different temporal scales. At shorter time scales, chest movements during breathing modulate the magnetic field, while at longer lags, vasodilatory effects of changes in arterial CO2 concentration significantly modulate cerebral blood flow and volume, thereby affecting the BOLD signal [6]. These respiratory effects frequently persist in data despite standard preprocessing, particularly in datasets lacking physiological recordings, and can covary with individual differences of interest, potentially producing spurious findings in group comparisons [6] [20].

The broader thesis framing this review posits that accurate interpretation of the relationship between FD and BOLD signal changes requires recognizing FD as a multifactorial index that reflects both head motion and physiological processes, with respiration serving as a key linking mechanism. This perspective necessitates more nuanced preprocessing approaches and analytical frameworks for distinguishing true neural signals from physiologically-confounded variance in fMRI data.

Physiological Basis of Respiratory Influence on BOLD Signals

Central Respiratory Control and Brainstem Mechanisms

Respiratory control is maintained by a distributed network of neural centers throughout the central nervous system. The fundamental respiratory pattern is generated primarily in the medulla oblongata, which contains the dorsal respiratory group (DRG) and ventral respiratory column (VRC) [21]. These centers integrate afferent signals from peripheral chemoreceptors and modulate respiratory motor neurons. Pontine centers, including the pneumotaxic and apneustic centers within the pontine respiratory group (PRG), provide fine-tuning influences over medullary centers to produce normal smooth inspirations and expirations [21].

Suprapontine structures, including limbic areas, diencephalon, striatum, and cortex, play essential roles in modulating the brainstem's respiratory drive [21]. This hierarchical organization means that respiratory control integrates automatic brainstem mechanisms with voluntary cortical influences, creating multiple pathways through which respiratory fluctuations can correlate with neural activity patterns of interest in fMRI studies.

Chemical Control of Respiration and Vascular Effects

Chemical regulation of respiration represents a primary pathway through which breathing affects the BOLD signal. Central chemoreceptors in the brainstem continuously monitor pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2), and oxygen (pO2) in the blood [21]. When CO2 levels rise (hypercapnia), the resulting decrease in pH stimulates ventilation to remove excess gas. Cerebral blood flow is highly sensitive to arterial CO2 levels, with hypercapnia causing significant vasodilation and increased flow [21] [22].

The relationship between CO2 and cerebral vasculature creates a direct mechanism through which respiratory fluctuations influence the BOLD signal. Natural variations in breathing depth and rate produce oscillations in arterial CO2 that subsequently modulate cerebral blood flow and volume, creating widespread hemodynamic fluctuations across the brain that correlate with respiration but are independent of neural activity [6] [23]. These effects are particularly problematic for fMRI because they occur at similar temporal frequencies to neural activation patterns and can manifest as spurious functional connectivity.

Mechanical and Magnetic Field Effects

Beyond chemical pathways, respiration also influences the BOLD signal through physical mechanisms. Chest movements during breathing cause magnetic field modulations that can be detected in fMRI data, particularly with multiband, high temporal-resolution sequences [6] [24]. Respiratory-induced body movements can also produce small head displacements that are captured in FD metrics, creating a correlation between respiratory traces and FD timecourses [6].

The integration of these multiple pathways—chemical, vascular, and mechanical—establishes respiration as a significant confound in interpreting the relationship between FD and BOLD signal changes. The following diagram illustrates these interconnected pathways:

Methodological Approaches for Quantifying Respiratory Effects

Lagged Covariance Analysis Using Peri-Stimulus Time Histograms

Several innovative methods have been developed to quantify the temporally extended relationship between FD, respiration, and BOLD signals. One powerful approach uses a construction similar to a peri-event time histogram to assess whether common structure exists in BOLD epochs following similar instances of a nuisance signal (e.g., framewise displacements within a specific range) [6].

This method involves several key steps. First, all framewise displacements within a particular magnitude range are identified across the fMRI timecourse. Next, BOLD signal epochs following these displacements are extracted and aligned. Finally, covariance across these aligned epochs is computed to identify systematic patterns of lagged BOLD changes associated with the preceding displacements [6]. This approach can reveal structured, prolonged changes in the BOLD signal that extend for 20-30 seconds following even very small displacements and depend systematically on the magnitude of the preceding displacement [6].

Data-Driven Respiratory Signal Reconstruction

When respiratory recordings are unavailable—a common scenario in existing fMRI datasets—computational techniques can reconstruct respiratory variation signals directly from fMRI data. One such method uses multivariate pattern analysis to estimate continuous low-frequency respiration volume (RV) fluctuations from fMRI data alone [23].

The reconstruction approach typically involves several processing stages. First, the fMRI data undergoes standard preprocessing, including motion correction and spatial normalization. Next, spatial components most strongly associated with respiratory patterns are identified, often through principal component analysis (PCA) or independent component analysis (ICA) of noise regions of interest [23] [20]. These components are then integrated into a continuous respiratory variation signal that can be used for noise modeling in subsequent analyses. Validation studies demonstrate that predicted RV signals can account for similar patterns of temporal variation in resting-state fMRI data compared to measured RV fluctuations [23].

Multi-Echo Acquisition and RETROICOR Methods

For studies collecting dedicated physiological data, the RETROICOR (Retrospective Image Correction) method provides a robust approach for modeling and removing cardiac and respiratory noise from fMRI data [24]. This method uses concurrently recorded cardiac and respiratory signals to create phase-locked noise models that are regressed out of the fMRI time series [24].

In multi-echo fMRI acquisitions, RETROICOR can be implemented in two primary ways: applying corrections to individual echoes (RTCind) before combining them, or applying correction to the composite multi-echo data (RTCcomp) after combination [24]. Studies comparing these approaches found minimal differences between them, with both methods significantly improving data quality metrics such as temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) and signal fluctuation sensitivity, particularly in moderately accelerated acquisitions [24].

The following table summarizes key methodological approaches for quantifying and addressing respiratory confounds:

Table 1: Methodological Approaches for Respiratory Confound Quantification and Mitigation

| Method | Principle | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged Covariance Analysis [6] | Identifies systematic BOLD patterns following FD events | fMRI data with FD traces | Reveals temporal extent of artifacts; Quantifies variance explained | Does not distinguish physiological sources |

| RV Signal Reconstruction [23] | Derives respiratory signals from fMRI data | fMRI data alone | Enriches existing datasets; Works without physiological recordings | Model-dependent accuracy |

| RETROICOR [24] | Models physiological noise using recorded signals | fMRI + cardiac/respiratory recordings | Direct noise modeling; High efficacy with good quality data | Requires physiological recordings |

| Multi-Echo ICA [24] | Separates BOLD and non-BOLD components using T2* decay | Multi-echo fMRI data | Data-driven; Does not require external recordings | Requires specialized sequences |

| aCompCor [20] | Uses noise ROIs (WM/CSF) for noise estimation | fMRI data alone | Anatomically guided; Widely implemented | May remove neural signal in WM |

Quantitative Evidence of Respiratory Artifacts

Magnitude and Temporal Extent of FD-Linked BOLD Changes

Empirical studies using the lagged covariance approach have quantified the substantial impact of respiration-linked FD fluctuations on the BOLD signal. Research demonstrates that framewise displacements—both large and very small—are followed by structured, prolonged changes in the BOLD signal that persist for tens of seconds (20-30 seconds) following the initial displacement [6].

The magnitude of these signal changes varies systematically according to the initial displacement magnitude, with larger displacements predicting larger subsequent BOLD fluctuations [6]. This lagged BOLD structure is remarkably consistent across datasets and independently predicts considerable variance in the global cortical signal—as much as 30-40% in some subjects—highlighting the potentially massive confounding effect of respiration-linked motion on functional connectivity findings [6].

Functional Connectivity Implications

Critically, mean functional connectivity estimates vary systematically as a function of displacements occurring many seconds in the past, even after strict censoring of high-motion volumes [6]. This finding suggests that standard motion censoring approaches may be insufficient for addressing the temporally extended effects of respiration-linked motion on connectivity metrics.

The spatial distribution of respiratory-related artifacts also poses particular challenges. Respiratory effects manifest as widespread hemodynamic fluctuations across the brain, with particular strength in regions near large vessels and cerebrospinal fluid spaces [22] [20]. This global pattern means that respiratory artifacts can inflate apparent connectivity between distant regions, potentially producing spurious network identifications.

Table 2: Quantitative Measures of Respiratory and FD Impact on BOLD Signals

| Metric | Finding | Temporal Characteristics | Implications for fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained [6] | FD-linked structure explains 30-40% of global signal variance in some subjects | Prolonged effects (20-30 seconds) | Massive potential for false positives in individual differences research |

| Temporal Lag [6] | Maximum BOLD changes occur several seconds after FD events | Peak effects at 5-15 second lag | Standard censoring insufficient; Need extended nuisance modeling |

| Spatial Distribution [6] [20] | Global cortical signal affected; Widespread patterns | Simultaneous effects across networks | Can inflate long-range connectivity; Produce spurious network identification |

| Respiratory-Cardiac Interaction [22] [25] | Respiratory sinus arrhythmia modulates heart-brain coupling | Cyclic patterns at respiratory frequency | Introduces complex physiological interactions beyond simple respiration |

| Age Effects [26] [20] | Older adults show reduced cardiorespiratory-brain coupling | Persistent throughout lifespan | Age-dependent artifact structure requires tailored denoising |

Mitigation Strategies and Denoising Approaches

Global Signal Regression and Tissue-Based Regression

Multiple preprocessing strategies have been developed to mitigate respiratory artifacts in fMRI data. Global signal regression (GSR) has been shown to largely attenuate artifactual structure associated with framewise displacements, both in the BOLD signal and in functional connectivity metrics [6]. However, GSR remains controversial because it may also remove neurally-relevant global signal fluctuations and can alter the interpretability of connectivity matrices by introducing negative correlations [20].

Alternative approaches include regression of signals from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (WM-CSF regression), which assumes these regions primarily contain noise rather than neural signals [20]. While this method avoids some limitations of GSR, evidence suggests that white matter also contains information about brain function, and average signals from WM and CSF may not account for regionally-specific temporal variations of physiological effects [20].

Component-Based Methods (CompCor and ICA-AROMA)

Component-based denoising methods provide more sophisticated approaches for respiratory artifact removal. The CompCor family of methods applies principal component analysis (PCA) on signals from "noise" regions of interest, removing components with the highest variance [20]. Anatomical CompCor (aCompCor) defines noise sources anatomically (within WM and CSF masks), while temporal CompCor (tCompCor) defines noise sources temporally (based on high temporal standard deviation) [20].

ICA-AROMA (Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts) uses independent component analysis to identify noise-related components based on spatial and temporal features, automatically removing those classified as motion or physiological artifacts [20]. Comparative studies have found that ICA-AROMA and GSR remove the most physiological noise but may also remove more low-frequency neural signals, while aCompCor and tCompCor appear better at removing high-frequency physiological signals but preserve more low-frequency power [20].

Multi-Echo Acquisition and Advanced Modeling

Multi-echo fMRI acquisition provides a powerful foundation for sophisticated denoising by acquiring multiple echoes for each image volume with varying T2* weighting [24]. This approach enables data-driven methods like multi-echo ICA (ME-ICA), which differentiates BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series based on their distinct T2* decay characteristics [24].

When combined with RETROICOR for physiological noise correction, multi-echo approaches can significantly improve data quality, particularly in moderately accelerated acquisitions (multiband factors 4 and 6) with optimized flip angles [24]. The integration of acquisition parameter optimization with advanced denoising represents the current state-of-the-art in addressing respiratory and motion-related confounds.

The following workflow diagram illustrates an integrated approach for addressing respiratory confounds:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Investigating Respiratory Confounds

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Recording Equipment (respiratory belt, pulse oximeter) [24] | Capture cardiac and respiratory signals during fMRI | RETROICOR modeling; Physiological noise correction | Synchronization with fMRI volumes; Signal quality verification |

| High-Temporal Resolution fMRI Sequences [6] [20] | Reduce physiological noise aliasing; Improve sampling of physiological signals | Studying dynamic processes; Spectral analysis of physiological noise | Trade-offs with spatial resolution and coverage |

| Multi-echo fMRI Acquisition [24] | Enable T2*-based BOLD/non-BOLD separation | ME-ICA denoising; Improved physiological artifact removal | Specialized sequences; Longer TR possible |

| Lagged Covariance Scripts [6] | Quantify temporally extended FD-BOLD relationships | Quality assessment; Artifact characterization | Customizable for different nuisance regressors |

| Data-Driven Denoising Tools (ICA-AROMA, CompCor) [20] | Remove physiological noise without recorded signals | Processing existing datasets; When physiological data unavailable | Method-specific biases; Parameter optimization needed |

| Respiratory Signal Reconstruction Algorithms [23] | Estimate respiratory traces from fMRI data alone | Enriching datasets lacking physiological recordings | Validation against measured signals when possible |

Respiration represents a critical physiological confound in understanding the relationship between framewise displacement and BOLD signal changes, operating through multiple interconnected pathways including chemical regulation of cerebral vasculature, mechanical effects on magnetic field homogeneity, and direct contributions to head motion metrics. The substantial variance explained by respiration-linked artifacts—up to 30-40% of global signal in some individuals—highlights the potential for spurious findings in functional connectivity research, particularly in studies investigating individual differences where respiratory patterns may covary with variables of interest.

Moving forward, the field requires increased adoption of integrated acquisition and processing approaches that explicitly account for respiratory confounds, including multi-echo sequences, physiological monitoring, and lagged artifact modeling. Researchers should implement rigorous quality assessment procedures to quantify residual respiratory artifacts after preprocessing and exercise appropriate caution when interpreting relationships between FD and BOLD signal changes, particularly in datasets lacking physiological recordings. Through more nuanced recognition and mitigation of respiratory confounds, we can advance toward more accurate characterization of neural processes in fMRI research.

Framewise displacement (FD) has traditionally served as a standard metric for quantifying head motion in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). However, emerging research positions FD as a multifactorial index that captures a complex interplay of physiological, technical, and artifact-related influences on Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal quality. This technical review synthesizes current evidence to argue that FD values reflect not merely subject motion but also intrinsic data quality issues that can confound functional connectivity analyses and brain-behavior associations. We present quantitative frameworks and experimental protocols demonstrating that elevated FD correlates with systematic alterations in functional connectivity, necessitating advanced denoising strategies and interpretation cautions. By reconceptualizing FD as a comprehensive data quality index, researchers can better account for multifactorial sources of variance in BOLD signal research and develop more robust analytical pipelines for neuroscientific and clinical applications.

In fMRI research, framewise displacement quantifies the volume-to-volume movement of a subject's head by summarizing the absolute derivatives of the six realignment parameters (three translations and three rotations) [27]. While originally developed as a motion metric, FD increasingly demonstrates sensitivity to multiple data quality factors beyond simple head movement. The profound impact of motion on fMRI data has been well-established, with even sub-millimeter movements systematically altering functional connectivity patterns [2].

Critically, FD values correlate with a distinct spatial signature of connectivity changes characterized by decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity [2]. This systematic bias poses particular challenges for studies of populations with inherently higher movement, such as children, older adults, and individuals with neurological or psychiatric conditions, potentially generating spurious brain-behavior associations [2]. Understanding FD as a multifactorial index rather than a simple motion metric reframes its utility in BOLD signal research and necessitates more sophisticated interpretation frameworks.

Quantitative Evidence: FD Thresholds and Their Impact on Data Quality

FD Thresholds in Experimental Applications

Research utilizing real-time FD monitoring has established specific thresholds for data quality intervention. In motion feedback studies, FD thresholds are strategically set to trigger visual cues to participants, demonstrating how FD values directly inform data acquisition quality control [27].

Table 1: Experimental FD Thresholds in Motion Feedback Protocols

| FD Threshold (mm) | Feedback Signal | Interpretation & Action |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.2 | White cross | Acceptable motion range |

| 0.2 - < 0.3 | Yellow cross | Cautionary range; moderate motion |

| ≥ 0.3 | Red cross | Excessive motion; need for reduction |

Impact of Residual Motion After Denoising

Even after implementing sophisticated denoising procedures, residual motion artifact continues to significantly impact functional connectivity measures. Analyses of the ABCD Study dataset reveal the persistent effects of motion after standard processing [2].

Table 2: Residual Motion Effects After Denoising in the ABCD Study

| Processing Stage | Variance Explained by Motion | Relative Reduction vs. Minimal Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal processing (motion-correction only) | 73% | Baseline |

| ABCD-BIDS denoising (respiratory filtering, motion timeseries regression, despiking) | 23% | 69% reduction |

| Relationship | Effect Size | Statistical Characterization |

| Correlation between motion-FC effect matrix and average FC matrix | Spearman ρ = -0.58 | Strong negative correlation |

| Motion-FC effect after censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) | Spearman ρ = -0.51 | Persistent strong negative correlation |

The data demonstrate that even after comprehensive denoising, motion continues to explain approximately one-quarter of the signal variance, with higher motion associated with systematically weaker connection strength across all functional connections [2].

Methodological Protocols: From Motion Monitoring to Connectivity Analysis

Real-Time FD Monitoring and Feedback Protocol

The FIRMM (FMRIB's Image Registration and Motion Monitoring) software implementation provides a methodology for real-time motion tracking and feedback during scanning sessions [27]. This protocol demonstrates the direct application of FD metrics for data quality improvement.

Experimental Protocol: Real-Time Motion Feedback with FIRMM

Software Setup: Implement FIRMM software for real-time calculation of realignment parameters and FD estimation during scanning sessions.

Participant Instruction: For the feedback group, provide specific instructions: "You will see a white fixation cross on the screen. The cross will change to yellow and then red depending on how much you are moving. It will go back to white if you become still again."

Visual Feedback Implementation: Program visual feedback using the following FD thresholds:

- White cross: FD < 0.2 mm

- Yellow cross: FD 0.2 mm to < 0.3 mm

- Red cross: FD ≥ 0.3 mm

Between-Run Feedback: After each scanning run, display a Head Motion Report showing performance on a gauge of 0-100% and a graph of motion level over time.

Participant Encouragement: Encourage participants to improve their score on subsequent runs.

Control Group Protocol: For the no-feedback group, provide standard instructions: "During this task, it is important that you hold your body and head very still. Please stay relaxed, stay alert, and keep your eyes open and on the fixation cross."

This protocol achieved a statistically significant reduction in average FD from 0.347 mm to 0.282 mm, with effects most apparent in high-motion events [27].

SHAMAN Protocol for Quantifying Motion Impact on Trait-FC Relationships

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) methodology provides a framework for quantifying trait-specific motion impact on functional connectivity, addressing the multifactorial nature of FD's influence on brain-behavior associations [2].

Experimental Protocol: SHAMAN Motion Impact Assessment

Data Preparation: Process resting-state fMRI data using standard denoising pipelines (e.g., ABCD-BIDS including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter timeseries regression).

Framewise Displacement Calculation: Compute FD for each participant across all resting-state scans.

Timeseries Splitting: For each participant, split the fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on FD values.

Connectivity Calculation: Compute functional connectivity matrices separately for high-motion and low-motion halves.

Trait-FC Effect Estimation: Measure the correlation between trait measures and FC for both halves.

Motion Impact Score Calculation:

- Compute difference in trait-FC effects between high-motion and low-motion halves

- Alignment with trait-FC effect direction indicates motion overestimation

- Opposite direction indicates motion underestimation

Statistical Validation: Use permutation testing and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections to generate significance values for motion impact scores.

Application of this protocol to 45 traits from n=7,270 participants in the ABCD Study revealed that 42% (19/45) of traits had significant motion overestimation scores and 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores after standard denoising without motion censoring [2].

Visualizing the Multifactorial Nature of FD and Its Impact

The following diagram illustrates the extended relationship between FD and multiple data quality factors in BOLD signal research.

The conceptual framework illustrates how FD serves as an integrative index capturing multiple sources of variance, with implications for data interpretation and mitigation strategy implementation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FD and Data Quality Management

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Real-Time Motion Monitoring | FIRMM (FMRIB's Image Registration and Motion Monitoring) software | Provides real-time calculation of realignment parameters and FD estimates during scanning; enables visual feedback to participants [27] |

| Denoising Pipelines | ABCD-BIDS preprocessing | Integrated denoising approach including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion timeseries regression, and despiking [2] |

| Motion Impact Assessment | SHAMAN (Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks) | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact on functional connectivity; distinguishes between overestimation and underestimation effects [2] |

| Advanced Connectivity Modeling | DELMAR (DEep Linear Matrix Approximate Reconstruction) | Deep learning approach for identifying hierarchical brain connectivity networks; incorporates denoising capabilities [28] |

| Data Quality Frameworks | Data Quality Dimensions (Completeness, Accuracy, Consistency, Validity, Uniqueness, Integrity) | Provides comprehensive metrics for assessing overall data quality beyond motion parameters [29] [30] |

Discussion: Implications for BOLD Signal Research and Future Directions