Global Signal Regression in fMRI: A Comprehensive Guide to Motion Artifact Reduction for Robust Brain Research

Global Signal Regression (GSR) remains one of the most contentious preprocessing steps in resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), presenting researchers with a critical dilemma.

Global Signal Regression in fMRI: A Comprehensive Guide to Motion Artifact Reduction for Robust Brain Research

Abstract

Global Signal Regression (GSR) remains one of the most contentious preprocessing steps in resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), presenting researchers with a critical dilemma. This article provides a definitive guide for scientists and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of GSR for motion artifact reduction. We explore the fundamental debate surrounding the neural versus non-neural origins of the global signal and establish the direct link between head motion and systematic artifacts in functional connectivity. The guide details practical implementation methodologies, including integration with complementary denoising techniques like ICA-FIX and motion censoring. We address common troubleshooting scenarios, such as interpreting negative correlations and handling divergent results, while presenting rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing evidence from large-scale datasets like the Human Connectome Project and ABCD Study, this resource empowers researchers to make informed, context-dependent decisions about GSR application to enhance the validity and reproducibility of their neuroimaging findings.

The GSR Debate: Unraveling the Neural and Non-Neal Origins of the Global Signal

In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the global signal (GS) is defined as the average blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal across the entire brain at each time point [1]. Its interpretation, however, remains a subject of ongoing debate within the neuroscience community. The GS is not a unitary phenomenon but rather a composite of multiple underlying processes, both neural and non-neural, which presents a fundamental challenge for its use in preprocessing pipelines.

The core controversy surrounding global signal regression (GSR) stems from this dual nature: while it effectively removes certain artifacts, it may also eliminate biologically meaningful neural fluctuations. This document delineates the precise components of the global signal, evaluates the effects of regressing it out, and provides detailed protocols for researchers, particularly those focused on motion artifact reduction.

Composition of the Global Signal

The global signal is a confluence of several physiological and neural sources. Understanding its composition is critical for interpreting the consequences of its regression.

Table: Constituent Components of the Global Signal

| Component Type | Specific Source | Contribution to GS | Primary Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Physiological | Respiration (Respiration Volume Per Time - RVT) | Significant fraction; shows strong spatial consistency with GS topography [1] | Simultaneous EEG-fMRI & respiratory recording [2] [1] |

| Cardiac Pulsation | Present, but weaker spatial relationship with GS compared to respiration [1] | Simultaneous EEG-fMRI & cardiac recording [2] | |

| Non-Neural Artifacts | Head Motion | Major source, especially with large movements [3] | Motion parameter estimation; "JumpCor" method development [3] |

| Scanner-related Fluctuations | Confounding variance | Preprocessing control techniques [4] | |

| Neural Activity | Arousal & Vigilance States | Linked to GS dynamics [1] | Studies of anesthetic-induced unconsciousness [5] |

| Spontaneous Neural Fluctuations | Preserved component within specific frequency ranges (e.g., alpha, beta) [2] | Simultaneous EEG-fMRI; GSR preserves EEG-derived connectivity [2] |

Key Quantitative Findings on Signal Origins

Recent studies have quantitatively assessed the contribution of various sources to the global signal:

- Physiological vs. Neural Sources: One study using simultaneous EEG-fMRI concluded that systemic physiological fluctuations account for a significantly larger fraction of global signal variability compared to electrophysiological fluctuations [2].

- Spatial Overlap with Respiration: Research with the Human Connectome Project data (N=770) demonstrated a strong spatial consistency between the GS and respiration (RVT) topography, with notable regional specificity. The overlap was particularly strong in the limbic, default mode, and salience networks [1].

- Preservation of Neural Signals: Despite the removal of global variance, GSR has been shown to preserve connectivity patterns associated with electrophysiological activity within the alpha and beta frequency ranges [2].

Effects and Controversies of Global Signal Regression

The application of GSR has distinct, and sometimes contradictory, effects on fMRI data analysis, influencing the interpretation of functional connectivity and its relationship to behavior.

Impact on Functional Connectivity and Motion Artifacts

GSR is a powerful technique for mitigating certain confounds in functional connectivity analysis.

- Motion Artifact Reduction: GSR significantly reduces artifactual connectivity arising from head motion [3]. This is particularly valuable in studies involving populations prone to movement, such as infants or clinical patients.

- Physiological Noise Removal: It effectively diminishes connectivity patterns related to physiological signals like heart rate and breathing fluctuations [2].

- Anesthetic-Specific Effects: The impact of GSR is not uniform. Research on anesthesia showed that GSR differentially affects brain activity patterns during propofol- and sevoflurane-induced unconsciousness. Sevoflurane-induced connectivity changes were particularly sensitive to GSR [5].

Controversial Aspects and Considerations

The use of GSR is not without significant controversy, primarily concerning the removal of potentially meaningful neural information.

- Removal of Neural Signal: The primary debate hinges on whether GSR removes neurally relevant information alongside noise. Some argue it can alter local and long-range correlations and potentially limit the assessment of connectivity patterns [5].

- Behavioral Relevance: The global signal itself has functional and cognitive relevance. Its topography has been linked to behavioral variables, including cognitive performance and psychiatric problems [1]. Regressing it out may therefore remove these behaviorally relevant signals.

- Dependence on Analysis Goals: The utility of GSR may depend on the specific research question. For studies focusing on network-specific correlates of behavior or disease, GSR might be beneficial. For investigations into global brain-body integration or arousal, it might be detrimental.

Table: Comparative Effects of Preprocessing with and without GSR

| Analysis Metric | Effect of GSR | Implication for Motion Artifact Research |

|---|---|---|

| Motion-Related Artifacts | Reduces artifactual connectivity from head motion, respiration, and cardiac cycles [2] [3]. | Primary benefit: Directly targets key non-neural noise sources. |

| Temporal Variability | Decreases similarly between states regardless of GSR in some anesthesia studies [5]. | Suggests some temporal dynamics are robust to GSR. |

| Network Topology | Minimally affects changes under propofol but significantly diminished sevoflurane-related network alterations [5]. | Effect is context-dependent (e.g., on anesthetic agent). |

| Structure-Function Coupling | Varies with the pairwise statistic used for FC; precision-based statistics show strong coupling [6]. | GSR's effect interacts with other methodological choices. |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Validating Neural Preservation Post-GSR using Simultaneous EEG-fMRI

This protocol is designed to quantify the neural component retained after GSR, a critical validation step.

1. Data Acquisition:

- Acquire simultaneous EEG-fMRI data during resting state.

- Concurrently record cardiac and breathing signals [2].

2. fMRI Preprocessing (Two Parallel Paths):

- Path A: Standard preprocessing (realignment, normalization, smoothing).

- Path B: Standard preprocessing + Global Signal Regression.

3. Global Signal Calculation:

- For Path A, extract the GS as the mean signal across the whole brain mask [1].

4. Functional Connectivity Analysis:

- For both paths, calculate resting-state functional connectivity matrices.

- Derive EEG-based functional connectivity in alpha/beta bands from the cleaned EEG data.

5. Correlation Analysis:

- Correlate the fMRI-FC matrices from both paths with the EEG-FC matrix.

- Interpretation: A significant positive correlation between GSR-fMRI-FC and EEG-FC indicates preservation of neurally relevant connectivity [2].

Protocol 2: Assessing GSR Efficacy for Motion Artifact Reduction

This protocol leverages a comparative approach to evaluate GSR against other denoising methods.

1. Data Preparation:

- Utilize a dataset including participants with occasional large head motions (e.g., >1 mm frame-to-frame displacement) [3].

- Preprocess data with standard realignment.

2. Multiple Denoising Pipelines:

- Process the data through several parallel pipelines:

- Pipeline 1: Standard preprocessing only (baseline).

- Pipeline 2: Standard + Motion Parameter Regression (6-24 regressors).

- Pipeline 3: Standard + Global Signal Regression.

- Pipeline 4: Standard + JumpCor (for large motions) [3].

- Pipeline 5: Combined approaches (e.g., GSR + Motion Regression).

3. Artifact Quantification:

- For each pipeline, calculate QC-FC correlations—the correlation between subject-wise mean motion and edge-wise functional connectivity [4].

- Interpretation: A successful denoising pipeline will show a weaker QC-FC correlation, indicating reduced motion-related artifact in connectivity matrices.

4. Data Quality Metrics:

- Apply quantitative metrics agnostic to QC-FC, such as those evaluating the signal-to-noise ratio in known low-motion periods [4].

- Final Recommendation: Choose the pipeline that optimizes these quality metrics for the specific dataset.

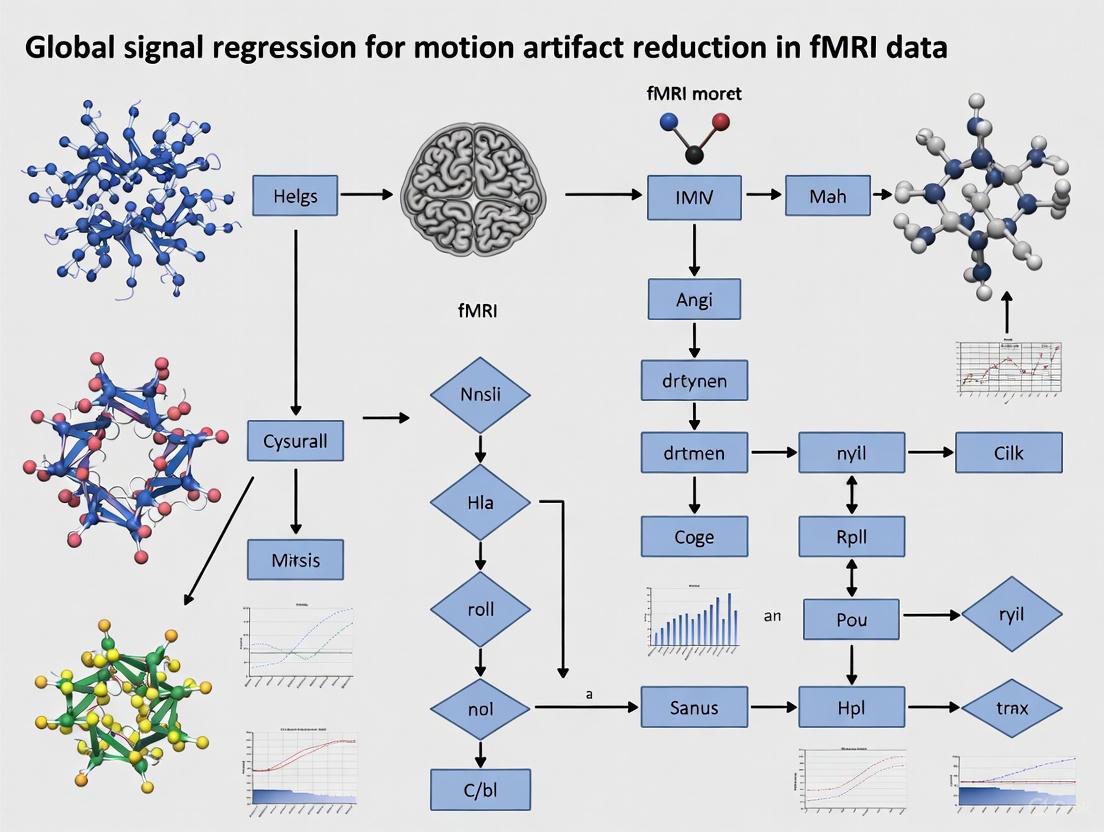

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Global Signal Composition and GSR Effects

Experimental Protocol for GSR Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for GSR Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous EEG-fMRI System | Records electrophysiological (EEG) and hemodynamic (fMRI) data concurrently to validate neural signals. | Quantifying neural information preserved after GSR [2]. |

| Physiological Monitoring (Respiratory Belt, Pulse Oximeter) | Records respiration (RVT) and cardiac (HR) signals for physiological noise modeling. | Mapping spatial contribution of physiology to GS [1]. |

| fMRIPrep | Robust, standardized pipeline for fMRI data preprocessing. | Ensuring reproducible preprocessing before GSR application [5]. |

| PySPI Package | Computes 239 pairwise interaction statistics for functional connectivity. | Benchmarking GSR's effect across different FC metrics [6]. |

| JumpCor Algorithm | Models signal baseline changes after large head "jumps" to reduce motion artifacts. | Correcting residual motion artifacts in conjunction with/or as an alternative to GSR [3]. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data | Publicly available, high-quality multimodal neuroimaging dataset. | Methodological benchmarking and testing hypotheses in large samples (N=770) [1] [6]. |

| CANONICC Correlation Analysis | Multivariate method to find shared patterns between brain topography and behavior. | Investigating overlap in GS-behavior and respiration-behavior relationships [1]. |

Head motion presents a fundamental methodological challenge for functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, particularly in the investigation of functional connectivity. Even sub-millimeter movements introduce systematic artifacts that can alter the interpretation of blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal correlations [7]. As in-scanner motion frequently correlates with key variables of interest such as age, clinical status, cognitive ability, and symptom severity, it introduces a pervasive confound that can bias study conclusions [7] [8]. The resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) paradigm is especially vulnerable to these artifacts because the spontaneous BOLD fluctuations of interest are remarkably small—typically just a few percent or less—making them susceptible to contamination by minute head movements [8]. Understanding the nature of these motion-induced artifacts, their spatial and temporal characteristics, and methods for their mitigation is therefore essential for generating valid and reproducible neuroimaging findings, particularly within the context of evaluating global signal regression as a potential corrective approach.

Characteristics and Mechanisms of Motion Artifacts

Spatial and Temporal Properties of Motion Artifacts

Head motion during fMRI acquisition produces complex spatiotemporal artifacts that manifest non-uniformly across the brain. The biomechanical constraints of the neck create a characteristic spatial pattern where motion is minimal near the atlas vertebrae (where the skull attaches to the neck) and increases with distance from this pivot point [7]. This results in anterior frontal and orbitofrontal regions exhibiting greater susceptibility to motion artifacts compared to posterior areas [7] [8]. Motion artifacts display distinctive temporal properties, with large movements producing immediate signal drops that scale with motion magnitude, maximal in the volume acquired immediately after movement [7]. Additionally, longer-duration artifacts persisting for 8-10 seconds can occur idiosyncratically, potentially due to motion-related changes in CO₂ from yawning or deep breathing [7].

Table 1: Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on fMRI Data |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Distribution | Increasing motion with distance from neck pivot point; frontal regions most affected | Regional bias in artifact distribution; distance-dependent connectivity changes |

| Temporal Signature | Immediate signal drop after movement; potential longer-duration (8-10s) artifacts | Non-linear, time-varying signal changes that complicate correction |

| Frequency Content | Non-band-limited, contaminating both low and high frequencies | Ineffective removal by standard band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) |

| Spin History Effects | Out-of-plane movements cause variations in longitudinal magnetization recovery | Altered signal intensity due to partial volume effects at tissue boundaries |

Impact on Functional Connectivity Metrics

Motion artifacts systematically distort functional connectivity measures in distinctive patterns that can mimic or mask genuine neurobiological phenomena. A consistent finding across studies is that motion inflates short-range connectivity while weakening long-range connectivity [9] [8]. This distance-dependent effect arises because motions cause signal changes that are more similar in adjacent voxels than in distant ones. Additionally, characteristic orientation dependencies have been observed, with increased lateral connectivity at the expense of connectivity in the inferior-superior and anterior-posterior directions [8]. These systematic distortions are particularly problematic in case-control studies where clinical populations (e.g., children, elderly individuals, or patients with neurological disorders) often exhibit different motion profiles than healthy control groups, potentially creating spurious group differences or masking genuine effects [7] [8].

Figure 1: Motion Artifact Impact Pathway. Head motion induces multiple signal artifacts that systematically bias connectivity measures, potentially leading to erroneous group differences in fMRI studies.

Quantifying Head Motion

Framewise Displacement and Related Metrics

In-scanner motion is typically quantified using parameters derived from volume-based realignment procedures. The most common approach involves rigid-body alignment of each volume to a reference image, producing six realignment parameters (RPs)—three translations (x, y, z) and three rotations (pitch, yaw, roll) [7]. These parameters are frequently summarized as Framewise Displacement (FD), which computes the relative displacement of each volume compared to the previous one [7] [10]. Different methods exist for calculating FD, with the formulation by Jenkinson et al. (implemented in FSL) demonstrating superior alignment with voxel-specific displacement measures [7]. It is important to note that FD measures are limited by the temporal resolution of the acquisition sequence and cannot effectively capture within-volume motion, which becomes particularly relevant with modern multiband sequences featuring very short repetition times [7].

Table 2: Motion Quantification Metrics in fMRI

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Realignment Parameters (RPs) | 3 translations + 3 rotations from rigid-body registration | Direct measure of volume-to-volume movement | Does not capture non-linear/spin history effects |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Derivative of RPs; summarizes overall movement between volumes | Comprehensive scalar metric of volume-to-volume motion | Varies with TR; difficult to compare across sequences |

| DVARS | Root mean square of voxel-wise signal differences between volumes | Measures overall BOLD signal change potentially due to motion | Sensitive to both motion and true neural signal changes |

| Voxel-Specific FD | Displacement computed directly from image header for each voxel | Accounts for spatial variation in motion effects | Computationally intensive; rarely used in practice |

Motion Correction Methodologies

Retrospective Correction Approaches

Retrospective correction methods applied during data preprocessing represent the primary defense against motion artifacts in fMRI research. These approaches include:

Regression-based methods: Nuisance regressors derived from realignment parameters are included in general linear models to account for motion-related variance. Expanded models incorporating temporal derivatives and quadratic terms of realignment parameters better capture delayed and non-linear motion effects [7] [9]. The addition of these expanded terms has been shown to diminish motion-induced artifacts more effectively than basic realignment parameter regression alone [9].

Volume censoring (scrubbing): Identifies and removes individual volumes exceeding specific motion thresholds (typically FD > 0.2-0.5 mm) [10] [9]. This approach directly targets large, transient motion artifacts but reduces temporal degrees of freedom and can introduce discontinuities in the time series [9].

Tissue-based nuisance regression: Incorporates signals from regions not expected to contain BOLD fluctuations of neuronal origin, specifically white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [9]. Two primary approaches exist: the mean signal method (averaging across all voxels in tissue masks) and aCompCor (using principal components analysis to extract multiple noise components from these regions) [9]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that aCompCor more effectively attenuates motion artifacts and enhances connectivity specificity compared to mean signal regression [9].

Physiological noise correction: Methods like RETROICOR utilize external measurements of cardiac and respiratory cycles to model and remove physiological fluctuations [11]. In multi-echo fMRI, RETROICOR can be applied to individual echoes or composite data, with both approaches showing significant noise reduction, particularly in moderately accelerated acquisitions [11].

Global Signal Regression: Controversies and Applications

Global signal regression (GSR)—removing the mean signal across all brain voxels from each timepoint—represents one of the most debated preprocessing techniques in rs-fMRI [12] [13]. As a "catch-all" approach, GSR effectively reduces global artifacts arising from motion and respiration but also removes globally distributed neural information and introduces negative correlations between brain regions [12] [14]. The global signal comprises contributions from multiple sources, with low-frequency drifts, motion, and physiological noise collectively explaining approximately 93% of its variance in minimally processed data [12]. Notably, recent evidence suggests that GSR can strengthen associations between functional connectivity and behavior, with studies reporting 40-47% increases in behavioral variance explained by whole-brain connectivity measures after GSR application [14]. This enhancement appears particularly beneficial for task performance measures compared to self-reported traits [14].

Figure 2: Global Signal Regression Effects. GSR has dual effects—reducing global artifacts while potentially removing neural signal of interest—leading to ongoing controversy in the field.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Correction

Comprehensive Preprocessing Pipeline

Based on current evidence, an optimal motion correction strategy employs a multi-pronged approach combining several methodologies:

Volume realignment: Compute six rigid-body realignment parameters through registration to a reference volume.

Nuisance regression: Include 24 motion regressors (6 basic parameters + temporal derivatives + quadratic terms) [9]. Additionally, implement aCompCor to extract noise components from white matter and CSF masks rather than simple mean signal regression [9].

Global signal consideration: Evaluate results with and without GSR, particularly when investigating brain-behavior relationships [13] [14]. Document both analytical paths for transparency.

Temporal filtering: Apply high-pass filtering (typically >0.008 Hz) to remove slow drifts, with careful consideration of potential motion-smearing effects [10].

Volume censoring: Identify and scrub volumes with FD exceeding 0.2-0.5 mm, depending on acquisition parameters and research questions [10] [9]. Note that scrubbing may provide limited additional benefit when aCompCor has been implemented [9].

Multi-echo acquisition: When available, acquire multi-echo data and implement dedicated processing pipelines (e.g., ME-ICA) to differentiate BOLD from non-BOLD components [11].

Table 3: Protocol Comparison for Motion Artifact Reduction

| Method | Protocol Details | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| aCompCor | Extract 5-10 principal components from WM/CSF masks; include as nuisance regressors | Superior to mean signal regression for motion reduction and specificity | May require careful component selection |

| Extended Motion Regression | 24 regressors (6 RPs + derivatives + quadratics) | Better captures non-linear motion effects than basic regression | High collinearity among regressors |

| GSR + Extended Regression | Global signal removal combined with expanded motion regressors | Effective artifact reduction; enhanced brain-behavior correlations | Introduces negative correlations; removes neural signal |

| Multi-echo ICA | Combine echoes; decompose with ICA; classify BOLD vs. non-BOLD components | Effective physiological noise removal without external recordings | Requires specialized sequences; computationally intensive |

Acquisition Parameter Optimization

Beyond retrospective correction, acquisition parameters significantly influence motion artifact severity. Multiband acceleration factors and flip angles modulate data quality, with moderate acceleration (multiband factors 4-6) and optimized flip angles (∼45°) providing favorable trade-offs between acquisition speed and artifact vulnerability [11]. Additionally, scan duration directly impacts data quality and functional connectivity reliability, with evidence suggesting that longer scans (≥20 minutes) improve phenotypic prediction accuracy in brain-wide association studies [15]. The total scan duration (sample size × scan time per participant) demonstrates a logarithmic relationship with prediction accuracy, indicating interchangeability between sample size and scan time up to a point [15]. Cost-benefit analyses suggest that 30-minute scans are typically most cost-effective, yielding approximately 22% savings compared to 10-minute scans while maintaining prediction performance [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Analytical Tools for Motion Correction Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies volume-to-volume head motion | Use Jenkinson formulation for voxel-specific accuracy; standardize for TR differences |

| aCompCor | Extracts multiple noise components from WM/CSF | Prefer over mean signal regression; optimal number of components (typically 5-10) varies by dataset |

| Global Signal Regression (GSR) | Removes whole-brain mean signal from time series | Apply with and without GSR; particularly beneficial for brain-behavior associations |

| Volume Censoring | Removes high-motion volumes from analysis | Threshold ~0.2-0.5mm FD; may be redundant with aCompCor |

| Multi-echo fMRI | Acquires data at multiple TEs to separate BOLD/non-BOLD | Enables ME-ICA; effective for physiological noise removal |

| RETROICOR | Models physiological noise using external recordings | Requires cardiac/respiratory monitoring; compatible with multi-echo sequences |

Motion artifacts remain a persistent challenge in fMRI research with particular relevance for studies investigating global signal regression. The complex spatiotemporal properties of motion-induced signal changes necessitate multi-faceted correction approaches rather than reliance on any single methodology. While GSR demonstrates efficacy in enhancing brain-behavior associations, its mechanism—whether through improved artifact removal or alternative processes—requires further elucidation. Emerging acquisition techniques including multi-echo fMRI and real-time motion correction hold promise for next-generation artifact mitigation. Regardless of methodological choices, complete reporting of motion quantification metrics and correction procedures is essential for interpretation and replication across studies. As the field moves toward consensus practices, researchers should consider their specific experimental questions and population characteristics when selecting from the available motion correction toolkit, recognizing that different processing approaches likely reveal complementary insights into brain function [13] [6].

In resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) research, the global signal (GS) is operationally defined as the average time course of signal intensity across all voxels in the brain [12]. For years, the prevailing view considered the GS primarily a source of non-neuronal noise dominated by physiological artifacts from motion, respiration, and cardiac activity [16]. Consequently, global signal regression (GSR) became a widely adopted, though contentious, preprocessing step to remove these putative artifacts [13].

However, a paradigm shift is underway. A growing body of evidence from multimodal studies demonstrates that the GS carries fundamental biological significance, with direct links to widespread neural activity and the regulation of arousal levels [17]. This application note synthesizes current evidence and provides practical methodologies for researchers investigating the neural foundations of the global signal, reframing it from a nuisance to a critical component of brain function.

Neural and Physiological Basis of the Global Signal

Key Evidence for the Neural Origins of the Global Signal

Table 1: Key Evidence Supporting the Neural Basis of the Global Signal

| Evidence Type | Key Finding | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Electrophysiology | fMRI-based GS correlates with infraslow (<0.1 Hz) fluctuations in local field potentials and broadband EEG power [17]. | Simultaneous fMRI-electrophysiology in macaques and humans [17] [18]. |

| Focal Inactivation | Inactivation of the cholinergic nucleus basalis of Meynert leads to regionally specific suppression of the GS ipsilaterally [18]. | Pharmacological inactivation in non-human primates [18]. |

| Metabolic Studies | Global signal amplitude is linked to changes in baseline glucose metabolism, reflecting overall energy demand [18]. | Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy [18]. |

| Arousal & Vigilance | GS amplitude fluctuations are correlated with changes in electroencephalographic (EEG) measures of vigilance and arousal [17] [18]. | Simultaneous EEG-fMRI studies in humans [18]. |

Signaling Pathways and Physiological Correlates

The global signal is not a mere epiphenomenon but is integrated within a complex brain-body axis. It is closely coupled with low-frequency oscillations in physiological signals like respiration and heart rate, which themselves exhibit infraslow rhythms [17]. This coupling is believed to be facilitated by infraslow neural activity, which provides a temporal structure that synchronizes bodily and brain-wide neural signals, potentially through phase-based mechanisms [17]. This integrated system plays a psychophysiological role in mediating the level of arousal.

Figure 1: Signaling pathways linking subcortical nuclei, infraslow neural activity, the global signal, and its physiological and cognitive correlates. NBM: Nucleus Basalis of Meynert.

Functional Significance: Arousal and Behavior

The Global Signal as a Mediator of Arousal

Evidence from combined EEG-fMRI studies strongly supports a link between the GS and arousal. The amplitude of the GS fluctuates with EEG-measured changes in vigilance, suggesting it tracks the brain's overall arousal state [17] [18]. This is physiologically plausible given the GS's association with subcortical neuromodulatory systems (e.g., cholinergic, serotoninergic) that are known to regulate cortical excitability and arousal levels on a global scale [17].

Behavioral Relevance and Dynamic Topography

The GS is not uniformly represented across the brain; it exhibits a dynamic topography—a spatially organized pattern of variation that recapitulates well-established large-scale functional networks [18] [19].

Table 2: Summary of GS Topography and Its Behavioral Relevance

| Network/Region in GS Topography | Associated Behavioral and Cognitive Correlates |

|---|---|

| Frontoparietal Control Network | Positive association with positive life outcomes: picture vocabulary, temporal discounting, life satisfaction [18]. |

| Default Mode & Dorsal Attention Networks | Represented in secondary topographical components; anticorrelation pattern [18]. |

| Sensorimotor & Visual Networks | Negative association with positive life outcomes in the primary canonical variate [18]. |

| Overall Positive-Negative Axis | A topographical pattern (high Frontoparietal, low Sensorimotor/Visual) is linked to an axis of positive psychological function and life outcomes versus negative ones like aggressive behavior [18]. |

This topography is behaviorally relevant. Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) of data from the Human Connectome Project revealed that individual differences in GS topography are significantly related to a broad axis of positive and negative life outcomes and psychological function [18] [19]. Furthermore, the utilitarian value of the GS is highlighted by studies showing that GSR can strengthen the association between resting-state functional connectivity and behavioral measures, improving the predictive power of neuroimaging data [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Global Signal Topography and Relating it to Behavior

This protocol outlines the steps to derive individual maps of GS topography and relate them to behavioral phenotypes using a large dataset like the Human Connectome Project (HCP) [18].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Acquire high-temporal-resolution rs-fMRI data (e.g., HCP-style: 4 runs of 15 minutes, multiband acquisition).

- Perform standard preprocessing: motion correction, slice-timing correction, alignment to structural images, and surface-based mapping.

- Optional: Apply nuisance regression (e.g., white matter, cerebrospinal fluid signals) before GS calculation if focusing on "cleaned" neural components.

2. Global Signal Beta Map Calculation:

- For each subject and run, compute the global signal (GS) by averaging the time series across all cortical surface vertices [18].

- For each vertex on the cortical surface, run a linear regression where the vertex's time series is the dependent variable and the whole-brain GS is the independent variable.

- The resulting beta coefficient for the GS at each vertex represents the strength and direction of the GS's expression at that location.

- Average the beta maps across all runs for each subject to create a stable subject-level GS beta map.

3. Dimensionality Reduction and Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA):

- Input all subjects' GS beta maps into a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality and identify major patterns of inter-subject variance [18].

- Compile a matrix of behavioral measures (e.g., cognition, personality, life outcomes) for all subjects. Perform PCA on this behavioral matrix.

- Conduct a CCA between the principal components of the GS topography and the principal components of the behavioral data to identify multivariate relationships between brain and behavior [18].

- Use non-parametric permutation testing to determine the statistical significance of the canonical correlations.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for analyzing global signal topography and its behavioral relevance.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Utilitarian Impact of GSR on Behavior-FC Association

This protocol tests whether GSR strengthens or weakens the relationship between functional connectivity (FC) and behavior, providing a practical framework for deciding on its use [20].

1. Data Processing with and without GSR:

- Process the same rs-fMRI dataset (e.g., from GSP or HCP) through two separate pipelines.

- Pipeline A (No GSR): Includes standard nuisance regression (e.g., motion parameters, white matter, CSF signals).

- Pipeline B (With GSR): Includes all regressors from Pipeline A, plus the global signal.

2. Functional Connectivity and Model Training:

- For both pipelines, compute a whole-brain functional connectivity matrix (e.g., correlation between region of interest time series) for each subject.

- For a set of behavioral measures (e.g., fluid intelligence, personality scores), use a variance component model (or kernel ridge regression) to quantify the total variance in behavior explained by the whole-brain FC [20].

- Train and test predictive models (e.g., kernel ridge regression) using the FC matrices from each pipeline to predict behavioral scores.

3. Comparison and Interpretation:

- Compare the variance explained (from the variance component model) and prediction accuracy (from the regression) between the two pipelines.

- An increase in variance explained and prediction accuracy after GSR suggests that, for the specific dataset and behaviors under study, GSR improves the behavioral signal-to-noise ratio by removing non-neural variance [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Global Signal Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Temporal-Resolution fMRI | Enables better capture of the global signal's dynamics and separation from other noise sources. | HCP-style multiband acquisitions [18]. |

| Surface-Based Processing | Provides a more accurate representation of cortical signals and improves cross-subject alignment for topography studies. | Calculating GS beta maps on cortical vertices [18]. |

| Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) | A multivariate statistical method to discover relationships between two sets of variables (e.g., brain maps and behavior). | Identifying a latent variable linking GS topography to a profile of life outcomes [18]. |

| Variance Component Model | Estimates the aggregate contribution of all FC features to explaining the variance of a behavioral trait. | Quantifying the total FC-behavior association strength with and without GSR [20]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression | A machine learning method for predicting continuous outcomes from high-dimensional features. | Predicting individual behavioral scores from whole-brain FC after different preprocessing steps [20]. |

| Public Datasets (HCP, GSP) | Provide large-sample, high-quality neuroimaging and behavioral data for robust discovery. | Benchmarking GS topography and its behavioral associations in healthy young adults [20] [18]. |

Global Signal Regression (GSR) is a preprocessing technique for functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that involves regressing out the average whole-brain blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal from each voxel's time series [21]. The procedure remains one of the most contentious methodological choices in resting-state fMRI analysis, creating a fundamental divide in the neuroimaging community. This controversy centers on a critical trade-off: GSR effectively removes global artifacts arising from motion and physiological sources, but may simultaneously discard biologically meaningful neural information distributed throughout the brain [2] [22].

The global signal represents low-frequency global fluctuations ranging from 0.001 to 0.1 Hz, derived from averaging BOLD signals across the entire brain or specific masks [21]. Proponents argue that GSR effectively mitigates confounding signals from head motion, respiration, and cardiac cycles [22], while opponents highlight that it introduces negative correlations whose neural meaning remains ambiguous and may remove meaningful neural signals associated with arousal and vigilance [1] [21]. This application note examines this central controversy through current evidence, provides experimental protocols for implementation, and offers guidance for researchers navigating this methodological challenge.

Quantitative Evidence: Weighing the Benefits and Consequences

Documented Benefits of GSR in Functional Connectivity Research

Table 1: Established Benefits of Global Signal Regression

| Benefit Category | Specific Effect | Quantitative Evidence | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artifact Reduction | Reduces motion-related signal changes | Significant reduction in motion artifacts, especially with occasional large movements (>1mm) | Infant fMRI with large motion [3] |

| Removes respiratory-related global fluctuations | Strong spatial consistency between GS and respiration topography (ICC = 0.4481) | HCP data (N=770) [1] | |

| Enhanced Behavioral Association | Improves RSFC-behavior associations | 47% average increase in behavioral variance explained across 23 measures | GSP dataset [22] |

| Improves behavioral prediction accuracy | 64% improvement in prediction accuracy in GSP dataset; 12% in HCP dataset | Kernel regression analysis [22] | |

| Connectivity Specificity | Preserves neural connectivity patterns | Reduced artifactual connectivity from heart rate/breathing while preserving EEG-derived connectivity in alpha/beta bands | Simultaneous EEG-fMRI [2] |

Potential Costs and Methodological Consequences of GSR

Table 2: Documented Limitations and Controversies of GSR

| Limitation Category | Specific Effect | Quantitative Evidence | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Information Loss | Removes globally distributed neural information | Considerable fraction of GS variations associated with physiological sources, but neural component preserved after GSR | Simultaneous EEG-fMRI [2] |

| Methodological Artifacts | Introduces negative correlations | Alters local and long-range correlations; limits assessment of connectivity patterns | Anesthesia studies [21] |

| State/Group Bias | Differentially affects brain states | Anesthetic-specific effects: alters propofol connections but broadly reduces sevoflurane connectivity differences | General anesthesia fMRI [21] |

| Interpretation Challenges | Complex relationship with behavior | Respiration-GS relationship correlates with psychiatric problems; GS topography with cognitive performance | HCP behavioral analysis [1] |

Experimental Protocols for GSR Implementation

Standard GSR Protocol for Resting-State fMRI

Table 3: Step-by-Step GSR Implementation Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Technical Specifications | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Preprocessing | Perform standard preprocessing pipeline | Slice-time correction, motion realignment, normalization, spatial smoothing (6mm FWHM), band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1Hz) | Standardizes data before GSR application [21] |

| 2. Global Signal Extraction | Calculate mean global signal | Average BOLD time series across whole brain, gray matter mask, or cortical mask | Creates reference signal for regression [22] |

| 3. Regression Modeling | Implement general linear model | Y = Xβ + ε, where X includes global signal plus nuisance regressors (motion parameters, WM, CSF signals) | Mathematically removes global variance [3] |

| 4. Residual Extraction | Save residual time series | Yresidual = Y - Xβglobal | Creates cleaned BOLD signal for subsequent analysis |

| 5. Quality Assessment | Verify artifact reduction | Check QC-FC correlations; compare with non-GSR processed data | Validates effectiveness of denoising [4] |

JumpCor Protocol for Large Motion Artifact Correction

For studies with populations prone to large, occasional movements (e.g., infants, clinical populations), the JumpCor technique provides an alternative motion correction approach that can be used alongside or instead of GSR [3]:

- Motion Parameter Calculation: Compute frame-to-frame displacement using Euclidean norm of temporal differences in six realignment parameters.

- Jump Identification: Identify large motion jumps exceeding a defined threshold (typically 1mm).

- Regressor Generation: Create binary regressors for each segment between large jumps (value=1 during segment, 0 outside).

- Model Implementation: Include JumpCor regressors as nuisance variables in GLM alongside other regressors.

- Segment Censoring: Remove one-time-point segments between movements from analysis.

This approach specifically addresses large, infrequent motions common in developmental and neuropsychiatric populations where traditional GSR may be insufficient [3].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: GSR Controversy Decision Pathway

Diagram 2: GSR Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for GSR Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Application Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Software | AFNI [3] | Comprehensive fMRI analysis | JumpCor implementation for large motion correction |

| fMRIPrep [21] | Automated preprocessing pipeline | Standardized preprocessing before GSR | |

| Nilearn [21] | Python-based fMRI analysis | GSR implementation and connectivity analysis | |

| Physiological Monitoring | Respiratory Belt [1] | Records respiration volume per time (RVT) | Quantifies respiratory contribution to GS |

| Cardiac Pulse Oximeter [21] | Records heart rate and oxygenation | Captures cardiac-related global fluctuations | |

| Simultaneous EEG-fMRI [2] | Direct neural activity correlation | Validates neural preservation after GSR | |

| Quality Assessment | QC-FC Correlation Tools [4] | Motion artifact quantification | Evaluates denoising effectiveness |

| ColorBrewer [23] [24] | Accessible visualization palettes | Creates color-blind friendly connectivity maps | |

| Frame-to-Frame Displacement Metrics [3] | Motion quantification | Identifies large jumps for JumpCor |

The controversy surrounding Global Signal Regression fundamentally reflects the complexity of interpreting fMRI signals, which inherently contain mixed neural and non-neural contributions. Current evidence suggests that GSR's utility is context-dependent: it appears particularly beneficial for enhancing behavior-FC relationships in healthy populations [22], while potentially introducing biases in cross-group comparisons or states of altered consciousness [21].

For researchers navigating this methodological challenge, the following evidence-based recommendations emerge:

- Implement both pipelines (with and without GSR) for critical analyses, particularly when studying clinical populations or states of altered consciousness [21].

- Supplement GSR with physiological monitoring (respiration, cardiac) to quantify and account for specific artifact contributions [1].

- Consider population-specific approaches - JumpCor for developmental populations with large motions [3], and careful comparative analysis for anesthetic studies [21].

- Prioritize research question - GSR appears most justified for behavioral correlation studies in healthy adults, while non-GSR approaches may be preferable for arousal or vigilance studies [2] [1].

The field continues to evolve with emerging evidence that physiological signals like respiration may have functional relevance beyond mere artifact [1]. This suggests that future approaches may need to move beyond simple removal versus retention dichotomies toward more sophisticated decomposition methods that distinguish different components of the global signal based on their neural versus physiological origins and functional significance.

In resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), the global signal (GS) is operationally defined as the spatial average of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) time courses across all brain voxels [16]. One of the most contentious preprocessing steps in rs-fMRI analysis is global signal regression (GSR), a technique intended to remove global noise but one that also introduces spurious negative correlations and potentially removes biologically relevant information [12] [20].

Central to the controversy surrounding GSR is its complex and special relationship with the default mode network (DMN), a large-scale brain network most active during rest and involved in internally-directed thought. Evidence suggests that rather than being purely a nuisance, the GS is strongly correlated with DMN activity, raising critical questions about the consequences of its removal for understanding brain function and connectivity [16] [25]. This Application Note explores this relationship, provides quantitative characterizations, and details experimental protocols for investigators.

Biological and Metabolic Basis of the GS-DMN Link

The strong association between the GS and the DMN is not merely a statistical artifact but is underpinned by shared neurobiological and metabolic substrates.

Neural and Metabolic Correlates: The DMN exhibits high levels of baseline glucose metabolism, and the BOLD signal fluctuations that characterize it are driven by metabolic demands. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) studies show that local glucose consumption in key DMN nodes, such as the medial frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and angular gyrus, is positively associated with the strength of functional connectivity within the DMN [25]. This provides a direct metabolic link to the synchronized BOLD fluctuations that constitute the GS.

Physiological and Non-Neural Contributions: The GS is a "catch-all" signal composed of multiple components. These include low-frequency drifts, motion-related artifacts, cardio-respiratory signals, and spin-history effects [12] [26]. One study found that after removing a full complement of nuisance regressors (low-frequency, motion, physiological, and white matter/CSF signals), only about 7% of the variance in the minimally processed global signal remained [12]. This residual component is hypothesized to be strongly related to neural activity, particularly that of the DMN.

The diagram below illustrates the composition of the Global Signal and its primary association with the DMN.

Quantitative Characterization of the GS-DMN Relationship

The relationship between the GS and the DMN has been quantitatively demonstrated through multiple experimental approaches. The table below summarizes key findings from the literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of the GS-DMN Relationship

| Experimental Finding | Quantitative Measure | Methodology | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong GS-DMN Temporal Correlation | GS is "strongly correlated" with DMN component time courses [16]. | Seed-based correlation & ICA of rs-fMRI data. | GS contains significant information about the brain's dominant resting-state network. |

| Shared Metabolic Variance | Local glucose consumption in DMN nodes associated with DMN functional connectivity [25]. | Simultaneous FDG-PET and rs-fMRI. | The GS-DMN link is supported by underlying metabolic activity. |

| GSR-Induced Anticorrelations | GSR introduces spurious negative correlations, centering the connectivity distribution on zero [16] [20]. | Comparison of correlation distributions before and after GSR. | GSR mathematically distorts native connectivity, especially creating DMN anticorrelations with task-positive networks. |

| GSR Strengthens Brain-Behavior Links | Behavioral variance explained by whole-brain RSFC increased by ~40-47% after GSR [20]. | Variance component modeling & kernel ridge regression in large datasets (HCP, GSP). | Removing the GS can improve the detection of behaviorally-relevant neural signals. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Core Analysis of GS-DMN Correlation

This protocol outlines the fundamental steps for quantifying the spatial and temporal relationship between the Global Signal and the Default Mode Network.

I. Materials and Data Acquisition

- Participants: Cohort of 20-30 cognitively normal adult participants is sufficient for an initial investigation [16].

- MRI Acquisition: Acquire T1-weighted anatomical images and 5-10 minutes of rs-fMRI data on a 3T scanner. Standard rs-fMRI parameters: TR=2000-3000 ms, TE=30 ms, voxel size=3-4 mm isotropic, 150-300 volumes [16] [25].

- Software: AFNI, FSL, SPM, or equivalent for analysis; MATLAB or Python for scripting.

II. Preprocessing Pipeline

- Basic Preprocessing: Perform slice-timing correction, realignment for motion correction, and co-registration of functional and anatomical images.

- Normalization: Spatially normalize functional data to a standard template (e.g., MNI).

- GS Calculation: Compute the global signal as the mean time series from all voxels within a whole-brain mask. Voxel time courses can be normalized as percent signal change from the mean [26].

- DMN Time Course Extraction:

- Method A (Seed-Based): Define a spherical seed region (e.g., 10mm radius) in a key DMN node like the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). Extract the mean time series from this seed.

- Method B (ICA): Perform group-independent component analysis (ICA) to identify the DMN component. For each subject, extract the mean time course from the DMN spatial map.

III. Core Analysis Steps

- Temporal Correlation: Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between the entire GS time course and the entire DMN time course for each subject. A group-level one-sample t-test can be used to confirm the correlation is significantly greater than zero.

- Satial Overlap: Regress the GS time course against the whole-brain fMRI data to create a "GS beta-map." Similarly, create a DMN functional connectivity map (via seed-based correlation or ICA). Visually and quantitatively (e.g., using Dice coefficient) assess the spatial overlap, particularly in core DMN hubs (PCC, medial prefrontal cortex, angular gyri).

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Global Signal Regression

This protocol describes how to evaluate the effects of GSR on DMN connectivity and network topography.

I. Data and Preprocessing

- Follow Protocol 1, steps I and II for data acquisition and basic preprocessing.

II. GSR Implementation

- Include the GS time course (calculated in Protocol 1, step II.3) as an additional nuisance regressor in a general linear model (GLM) alongside other confounds (e.g., 6 motion parameters, mean white matter, and CSF signals). Regress this entire set of confounds out of each voxel's time course [20] [27].

III. Post-GSR Analysis

- DMN Connectivity with and without GSR:

- Generate seed-based DMN connectivity maps for the same PCC seed, both with and without GSR.

- Compare: Observe the introduction of negative correlations (anticorrelations) between the DMN and "task-positive" networks (e.g., dorsal attention network) after GSR.

- Quantify Distributional Shift:

- For each subject, compute a whole-brain, voxel-wise functional connectivity matrix.

- Plot the distribution of all correlation coefficients (Fisher z-transformed) from the matrix. The distribution after GSR will be centered around zero, whereas the distribution without GSR will be centered on a positive value [16] [20].

The workflow for investigating the GS-DMN relationship and the impact of GSR is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AFNI (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages) | A comprehensive software suite for MRI data analysis, including registration, regression, and visualization. | Motion parameter estimation (3dvolreg), global signal calculation, and general linear model analysis [16] [26]. |

| FSL (FMRIB Software Library) | A comprehensive library of MRI analysis tools, including MELODIC for Independent Component Analysis (ICA). | Used for ICA-based denoising (FIX) and for identifying the DMN via group-ICA [20] [28]. |

| SPM (Statistical Parametric Mapping) | A software package for the statistical analysis of brain imaging data sequences. | Model specification and estimation for mass-univariate analysis; co-registration and normalization. |

| Multi-Echo fMRI Sequence | An acquisition sequence that collects data at multiple echo times (TEs), allowing better separation of BOLD from non-BOLD signals. | Used to isolate neural-related bias in motion parameters and to improve denoising via ME-ICA [26] [28]. |

| Physiological Monitoring Equipment (Pulse oximeter, respiratory belt) | Devices to record cardiac and respiratory cycles during scanning. | Used to create RETROICOR or RVHRCOR regressors to model and remove physiological noise from the BOLD signal [16] [12]. |

| High-Level Scripting Language (MATLAB, Python) | Environments for custom analysis scripting, data visualization, and statistical testing. | Implementing custom pipelines, calculating correlation metrics, and generating figures. |

Application Notes and Decision Framework

The decision to use GSR is not binary but should be guided by the research question and data quality.

When GSR May Be Beneficial: GSR is highly effective at removing global artifacts from motion and respiration. Its use is supported when the research goal is to strengthen associations between resting-state functional connectivity and behavioral measures, as it has been shown to increase explained behavioral variance by 40-47% in large cohorts [20]. It is also crucial when studying traits strongly correlated with motion (e.g., ADHD), where residual motion artifact can cause spurious brain-behavior associations [29].

When to Avoid or Be Cautious with GSR: If the primary research question involves the absolute level of functional connectivity, the neurobiology of anticorrelated networks, or the properties of the global signal itself (e.g., in studies of arousal or vigilance), GSR should be avoided. Its use can also distort group differences if the global signal itself is a feature that differs between populations [12] [20].

A Pragmatic Approach: Given the controversies, it is considered a best practice to analyze data with and without GSR and report the convergent and divergent findings. This approach provides a more comprehensive picture of the results and their robustness to different preprocessing choices [27].

Implementing GSR: Best Practices for Effective Motion Artifact Reduction

Global Signal Regression (GSR) remains one of the most contentious preprocessing steps in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) analysis. While controversial, GSR is recognized for its potent ability to mitigate motion-related artifacts and improve the spatial specificity of functional connectivity maps [30] [31]. This protocol frames GSR within the specific context of motion artifact reduction research, providing researchers with a balanced perspective on its applications and limitations. The ongoing debate stems from evidence that the global signal contains both neural and non-neural components, making the decision to apply GSR highly dependent on specific research questions and data characteristics [12] [32].

Recent systematic evaluations of fMRI data-processing pipelines reveal that appropriate pipeline selection, including the judicious use of GSR, can significantly enhance the reliability of functional connectomics [33]. Furthermore, studies incorporating simultaneous electrophysiological recordings demonstrate that GSR effectively reduces connectivity patterns related to physiological signals while preserving those associated with neural activity [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for integrating GSR into preprocessing workflows, with particular emphasis on motion artifact reduction for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundation: The Nature of the Global Signal

What is the Global Signal?

The global signal (GS) is computed as the average time course across all voxels within the brain [12]. This seemingly simple measure reflects a complex combination of neural activity and various noise sources. The signal represents a "catch-all" component that captures fluctuations shared across most brain voxels, with contributions from multiple sources:

- Neural activity: Widespread cortical firing and baseline shifts in vigilance [32]

- Physiological noise: Cardiorespiratory cycles, blood pressure variations, and respiratory volume changes [12] [2]

- Motion artifacts: Head movement during scanning causing displacement and spin history effects [30]

- Scanner drift: Low-frequency scanner instabilities and thermal fluctuations [12]

The proportional contribution of each source varies across datasets, individuals, and scanning conditions, making the interpretation of the global signal context-dependent.

The GSR Controversy: Key Arguments

Table 1: Arguments for and Against Global Signal Regression

| Support for GSR | Key Concerns |

|---|---|

| Reduces motion-related artifacts and distance-dependent correlations [30] | Introduces artificial anti-correlations between networks [32] |

| Improves spatial specificity of functional connectivity maps [31] | May remove biologically relevant neural signals [12] [32] |

| Enhances detection of group differences in high-motion populations [34] | Can distort correlation patterns and inter-individual differences [32] |

| Preserves neural components of connectivity while reducing physiological noise [2] | Mathematical constraints force negative mean correlation [32] |

Decision Framework: When to Apply GSR

Evidence-Based Application Guidelines

Table 2: GSR Recommendation Guidelines Based on Research Context

| Research Scenario | GSR Recommendation | Rationale | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies of high-motion populations (children, clinical, elderly) | Recommended | Effectively reduces motion-related artifacts | [34] [30] |

| Investigations of anti-correlated networks | Use with caution; validate without GSR | May artificially enhance anti-correlations | [32] [31] |

| Anesthesia studies (propofol vs. sevoflurane) | Anesthetic-specific considerations | Differential effects on connectivity patterns | [5] |

| Biomarker discovery with individual differences | Generally not recommended | May distort inter-individual variability | [33] [32] |

| Multiecho fMRI datasets | Potential alternative approaches available | ME-ICA may reduce need for GSR | [35] |

GSR Decision Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points for integrating GSR into a preprocessing pipeline:

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized GSR Implementation Protocol

Materials and Reagents:

- Preprocessed fMRI data (minimally preprocessed with motion correction and spatial normalization)

- Computing environment with statistical software (Python, R, MATLAB)

- Gray matter, white matter, and CSF masks (if using compartment-based regression)

- Physiological recordings if available (cardiac, respiratory)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Begin with minimally preprocessed fMRI data that has undergone standard steps: slice timing correction, motion realignment, and spatial normalization to standard space [36].

- Ensure data is in appropriate space (volume-based or surface-based) depending on analysis preferences. Surface-based methods may offer advantages for cortical data [36].

Global Signal Calculation

Nuisance Regression

- Construct a nuisance regressor matrix including:

- Global signal (mean time course)

- 6-24 motion parameters (and their derivatives)

- White matter and CSF signals (mean time courses from respective masks)

- Physiological regressors if available (cardiac, respiratory)

- Apply linear regression to remove variance associated with nuisance regressors from each gray matter voxel's time series [30].

- Construct a nuisance regressor matrix including:

Post-Regression Processing

- Apply temporal filtering (typically 0.008-0.09 Hz bandpass) to remove high-frequency noise and low-frequency drift.

- Perform connectivity analysis on residuals from the regression step.

Quality Control

- Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD) and DVARS to quantify motion.

- Verify that motion-FC relationships have been reduced, particularly distance-dependent correlations [30].

- Check for excessive negative correlations that may indicate GSR artifacts.

Alternative Methods for Global Noise Removal

When GSR is inappropriate for the research context, consider these alternative approaches:

ANATICOR (Regional White Matter Regression): Regresses out regional white matter signals from nearby gray matter voxels, providing localized noise correction without global signal removal [32].

CompCor (Component-Based Noise Correction): Uses principal components analysis (PCA) to identify noise components from white matter and CSF compartments, regressing out the top components instead of the global signal [32].

Multi-Echo ICA (ME-ICA): Leverages multi-echo fMRI data to differentiate BOLD from non-BOLD components, effectively removing motion-related artifacts without requiring GSR [35].

Group-Level Covariate Regression: Includes mean connectivity (GCOR) as a covariate in group-level analysis rather than regressing the global signal at the subject level [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for GSR Implementation and Validation

| Research Tool | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies head motion between volumes | Power et al. (2012) method [30] |

| DVARS | Measures rate of change in BOLD signal | Power et al. (2012) framework [30] |

| Portrait Divergence (PDiv) | Quantifies dissimilarity in network topology | Used in pipeline evaluation [33] |

| CIFTI Grayordinates | Combined surface-volume coordinate system | HCP minimal preprocessing pipelines [36] |

| fMRIPrep | Automated preprocessing pipeline | Esteban et al. (2019) [5] |

| Connectome Workbench | Visualization of surface-based data | HCP data visualization [36] |

Interpretation & Analytical Considerations

Validating GSR Effects

When GSR is applied, several validation steps are recommended:

Assess Motion Connectivity Relationships

- Calculate correlation between motion metrics (FD) and functional connectivity measures.

- Successful GSR application should reduce distance-dependent correlations, where motion disproportionately affects connections between nearby regions [30].

Compare With and Without GSR

Evaluate Network Topology Reliability

- Use test-retest datasets to assess whether GSR improves reliability of network topology measures.

- Optimal pipelines should minimize spurious test-retest discrepancies while preserving biological signals [33].

Domain-Specific Considerations

Anesthesia Studies: GSR has differential effects depending on anesthetic type. Propofol-induced connectivity changes are relatively preserved after GSR, while sevoflurane-induced changes are significantly attenuated [5]. Always consider anesthetic mechanism when interpreting GSR-processed data.

Clinical Populations: In high-motion populations (e.g., children, neurodegenerative disorders), GSR may improve data quality but can also remove disease-relevant signals. Consider disorder-specific literature when deciding on GSR application [34].

Pharmacological fMRI: GSR may remove global drug effects that are of scientific interest. For pharmacological challenges, carefully consider whether global signal changes represent confounds or meaningful biological responses.

Integrating GSR into fMRI preprocessing requires careful consideration of research goals, population characteristics, and analytical priorities. While GSR remains controversial, evidence supports its value for motion artifact reduction in specific contexts, particularly for high-motion populations and studies focusing on group-level effects rather than individual differences. The most robust approach involves running parallel analyses with and without GSR and validating key findings using complementary methods. As the field moves toward consensus, researchers should transparently report preprocessing choices and their potential impact on results, enabling more accurate interpretation and replication of functional connectivity findings.

In resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), the pursuit of clean neural signals free from motion and physiological artifacts remains a central methodological challenge. Global Signal Regression (GSR) is a potent yet contentious preprocessing technique that effectively reduces global artifacts stemming from motion and respiration by regressing out the whole-brain average signal from each voxel's time series [20]. Its efficacy, however, comes with significant trade-offs, including the introduction of negative correlations and the potential removal of neurally relevant global information [20] [37]. Conversely, ICA-FIX is a sophisticated automated classifier that identifies and removes noise components from independent component analysis (ICA) decompositions of fMRI data, offering a powerful data-driven alternative [38]. Individually, each method has distinct strengths and weaknesses; however, emerging evidence suggests that their strategic combination can yield superior denoising performance. This protocol details a synergistic approach that integrates GSR with ICA-FIX and physiological monitoring, creating a robust pipeline that maximizes artifact removal while preserving behavioral and neural signals of interest, thereby enhancing the reliability of functional connectivity findings for clinical and cognitive neuroscience applications [20] [39] [38].

Quantitative Efficacy of Denoising Strategies

The performance of various denoising pipelines can be evaluated using multiple benchmarks, including the residual relationship between motion and functional connectivity, data loss, and test-retest reliability. The table below synthesizes key findings from empirical comparisons.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Common fMRI Denoising Pipelines

| Denoising Pipeline | Residual Motion Artifact | Data Loss / Degrees of Freedom | Test-Retest Reliability | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSR | Effectively reduces global motion artifacts; introduces distance-dependent correlations with motion [39]. | Low data loss [39]. | Improves behavioral prediction accuracy (e.g., +40% in HCP) [20]. | Potent removal of global artifacts; strengthens brain-behavior associations [20] [38]. | Introduces negative correlations; may remove neural signal [20]. |

| ICA-FIX/ICA-AROMA | Excellent motion control, outperforming simple linear regression [39] [38]. | Moderate data loss (aggressive vs. non-aggressive variants) [39] [38]. | High network reproducibility and functional connectivity fingerprinting [38]. | Automatic, data-driven removal of motion-related components [38]. | Requires high-quality data; may not remove all global physiological noise [38]. |

| WM/CSF Regression | Limited efficacy; simple regression is insufficient for full motion removal [39]. | Low data loss [39]. | Moderate | Simple implementation; low cost in data retention [38]. | Ineffective for global signal artifacts; cannot account for regional-specific noise [38]. |

| aCompCor | Effective primarily in low-motion data [39]. | Low data loss [39]. | Associated with higher age-related fcMRI differences [38]. | Accounts for regional physiological noise variations [38]. | Performance varies with noise ROI definition; less effective for strong motion [39]. |

| Volume Censoring (Scrubbing) | Superior minimization of motion artifacts [39]. | High data loss, often leading to exclusion of high-motion subjects [39]. | High for retained data | Powerful for removing transient, high-motion artifacts [39]. | Significant reduction in temporal degrees of freedom; can bias sample by excluding high-motion individuals [39]. |

Furthermore, the combination of GSR with other techniques shows quantifiable benefits:

Table 2: Quantitative Benefits of Combining GSR with Other Denoising Methods

| Combined Approach | Dataset | Key Quantitative Benefit | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSR after ICA-FIX | Human Connectome Project (HCP) | Behavioral variance explained by whole-brain RSFC increased by an average of 40% across 58 measures [20]. | GSR provides unique denoising benefits beyond a sophisticated ICA-based method. |

| GSR with other pipelines | Multi-dataset evaluation | The addition of GSR improved the performance of nearly all pipelines on most benchmarks for motion control [39]. | GSR acts as a powerful complement to a wide range of denoising strategies. |

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Denoising

Protocol 1: Sequential ICA-FIX and GSR for Enhanced Behavioral Correlation

This protocol is designed to maximize the association between functional connectivity and behavioral measures, as validated in large-scale datasets [20].

Applicability: This workflow is ideal for studies focusing on individual differences in cognition, personality, or emotion, where strengthening the brain-behavior relationship is a primary goal.

dot Code for Diagram: "Workflow for Sequential ICA-FIX and GSR Processing"

Detailed Methodology:

Data Acquisition & Standard Preprocessing:

- Acquire rs-fMRI data. The Human Connectome Project (HCP) protocol (3T Skyra scanner, multiband sequence, TR=720ms, 2.0mm isotropic voxels) serves as a high-quality reference [20].

- Perform standard preprocessing steps including slice-time correction, motion realignment to generate 6 rigid-body parameters, and spatial normalization to a standard template (e.g., MNI152).

ICA-FIX Denoising:

- Temporal Filtering: Apply high-pass filtering (e.g., cutoff >200s) to the preprocessed data.

- Spatial ICA: Decompose the filtered data using a group-level or single-subject ICA. A common dimensionality of 25-100 components is typical.

- Automatic Classification: Process the derived components using the FIX classifier (trained on your specific dataset or a generic classifier) to label components as "signal" or "noise".

- Component Removal: Regress out the time courses of all noise-classified components from the preprocessed data. This yields a "FIX-cleaned" dataset [20] [38].

Global Signal Regression (GSR):

- Signal Extraction: From the FIX-cleaned data, compute the global signal (GS) as the average time series across all gray matter voxels or the entire brain mask.

- Nuisance Regression: Perform a multiple regression where the BOLD signal of each voxel is regressed against the GS alongside other nuisance regressors. These typically include:

Post-Processing & Connectivity Analysis:

- Apply temporal band-pass filtering (e.g., 0.01-0.1 Hz) to the residual time series to focus on low-frequency fluctuations.

- Compute final functional connectivity matrices (e.g., Pearson correlation between region time series) for subsequent behavioral analysis.

Protocol 2: Integrating Physiological Monitoring with Data-Driven Denoising

This protocol leverages externally recorded physiological signals to guide and validate data-driven denoising, offering the highest level of artifact control for studies where physiological confounds are a primary concern [40] [38].

Applicability: Critical for studies of aging, clinical populations, or any investigation where cardiac and respiratory rhythms may systematically differ between groups and confound neural inferences.

dot Code for Diagram: "Integration of Physiological Monitoring in Denoising"

Detailed Methodology:

Simultaneous Data Acquisition:

- fMRI: Acquire rs-fMRI data. A high temporal resolution (short TR, e.g., < 1s) is strongly recommended to prevent aliasing of cardiac and respiratory signals [38].

- Physiological Monitoring: Record the following synchronously with the fMRI data:

- Cardiac Signal: Using a pulse oximeter placed on a finger.

- Respiratory Signal: Using a respiratory effort belt around the abdomen/thorax.

- Head Motion Parameters: Derived from volume realignment.

Model-Based Physiological Noise Correction:

- Following initial preprocessing (steps 1-2 from Protocol 1), use the recorded physiological traces to generate noise regressors.

- RETROICOR: Apply the RETROICOR method to model phase-locked physiological fluctuations using a second-order Fourier series relative to the cardiac and respiratory cycles [37].

- RVHRCOR: Model variations in heart rate and respiration volume per time (RVT) as additional regressors to account for non-phase-locked effects [37].

- Regress these model-based physiological noise regressors from the data.

Data-Driven Denoising Suite:

Validation of Denoising Efficacy:

- Power Spectral Analysis: Compare the frequency power spectra of the BOLD signal before and after denoising. Successful pipelines show reduced power at cardiac (~1 Hz) and respiratory (~0.3 Hz) frequencies, while preserving power in the ultra-low frequency band (<0.1 Hz) [38].

- Motion-FC Correlation: Calculate the correlation between subject-wise mean frame-wise displacement (FD) and the resulting functional connectivity matrices. An effective pipeline minimizes this relationship [39].

Table 3: Key Software, Data, and Analytical Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICA-FIX | Software Tool | Automated classifier for identifying and removing noise components from ICA decompositions. | Core component for data-driven denoising in Protocol 1 [20] [38]. |

| ICA-AROMA | Software Tool | Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts; identifies noise components based on spatial and temporal features without needing a trained classifier. | A key alternative to FIX, especially useful in Protocol 2 for its robustness [39] [38]. |

| FSL | Software Suite | FMRIB Software Library; contains MELODIC for ICA and FIX for training classifiers, among many other preprocessing tools. | Provides the computational environment for running ICA-FIX and general fMRI analysis [39]. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data | Reference Dataset | A large-scale, high-quality neuroimaging dataset with rs-fMRI, behavioral, and physiological data. | Serves as a gold-standard benchmark for developing and testing denoising pipelines [20] [40]. |

| RETROICOR & RVHRCOR | Algorithm | Model-based methods for removing cardiac and respiratory noise from fMRI data using recorded physiological signals. | Critical for the model-based correction step in Protocol 2 [37]. |

| CONN Toolbox | Software Tool | A cross-platform MATLAB/Octave toolbox for functional connectivity analysis, includes aCompCor and other denoising methods. | Useful for implementing and comparing alternative denoising pipelines [38]. |