Head Motion in fMRI: Impacts on Functional Connectivity and Strategies for Robust Biomarker Development

Head motion is a pervasive and systematic source of artifact in functional MRI that confounds estimates of functional connectivity, threatening the validity of neuroimaging biomarkers, especially in clinical and developmental...

Head Motion in fMRI: Impacts on Functional Connectivity and Strategies for Robust Biomarker Development

Abstract

Head motion is a pervasive and systematic source of artifact in functional MRI that confounds estimates of functional connectivity, threatening the validity of neuroimaging biomarkers, especially in clinical and developmental populations. This article synthesizes current evidence on how motion induces spurious, distance-dependent changes in connectivity, inflating short-range and diminishing long-range connections. We review established and emerging denoising methodologies, including confound regression, censoring, and novel omnibus models, evaluating their performance in mitigating these artifacts. A critical focus is on motion's confounding role in studies of aging, psychiatric disorders, and cognition, and the resulting selection bias from excluding high-motion participants. Finally, we provide a framework for validating motion correction pipelines and discuss the implications for developing reliable biomarkers in neuroscience research and drug development.

The Fundamental Problem: How Head Motion Systematically Biases Functional Connectivity

Within the context of research on the impact of head motion on functional connectivity estimates, characterizing the resulting artifacts is a critical first step. Head motion is a dominant source of artifact in functional MRI (fMRI) signals, profoundly impacting measures of intrinsic functional connectivity [1]. Its systematic effects can mimic or obscure genuine neuronal effects, posing a significant threat to the validity of brain-wide association studies [2] [3]. This is particularly problematic when studying populations prone to greater movement, such as children, older adults, or individuals with certain neurological or psychiatric disorders, as spurious group differences can be easily mistaken for neuronal effects [2] [3]. This technical guide details the types and spatial signatures of motion-induced noise to equip researchers with the knowledge to identify and mitigate these confounds.

The Spatial Profiles of Motion-Induced Noise

The influence of head motion on functional connectivity is not random; it exhibits specific, systematic spatial patterns that can be identified and measured.

Systematic Alterations in Network Connectivity

Head motion systematically affects functional coupling in a manner that depends on the spatial distribution of the brain network in question. The table below summarizes the documented effects:

Table 1: Documented Effects of Head Motion on Functional Connectivity Networks

| Brain Network | Effect of Increased Motion | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Default Network | Decreased functional coupling [2] [3] | Distributed regions of association cortex [2] |

| Frontoparietal Control Network | Decreased functional coupling [2] [3] | Distributed regions of association cortex [2] |

| Local/Short-Range Networks | Increased functional coupling [2] [3] | - |

| Motor Network | Increased coupling between left/right motor regions [2] | Sometimes used as a control in studies [2] |

These motion-related effects are spatially systematic, consistently causing decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity [1]. The strength of functional connections tends to be uniformly weaker in participants who move more compared to those who move less [1].

Manifestation in ICA Components

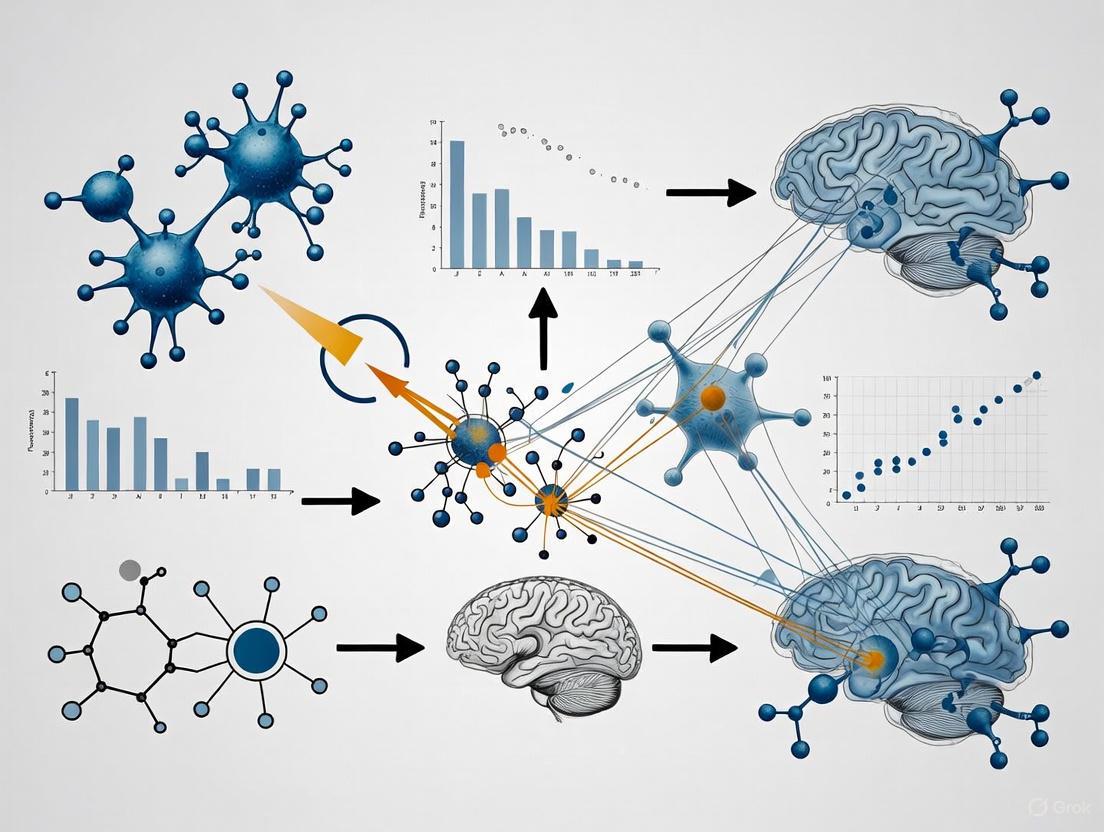

At the single-subject level, spatial Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is a powerful tool for blind source separation, decomposing fMRI data into spatial maps and time courses. A "noise component" (N-IC) characterizes a noise/artefact effect [4]. The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for identifying motion-induced noise components via ICA.

The identification of N-ICs relies on assessing specific spatial and temporal features. Spatially, motion-related artifacts often exhibit specific patterns that differ from neural signals [4].

Quantitative Frameworks for Assessing Motion Impact

Quantifying the extent of motion artifact is essential for ensuring robust findings. Recent large-scale studies provide concrete data on the scale of this problem and methods to assess it.

The Scale of Residual Motion Post-Denoising

Even after standard denoising procedures, a significant amount of variance in the fMRI signal can be attributed to head motion. An analysis of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study data quantified this as follows:

Table 2: Efficacy of Denoising in Reducing Motion-Related Variance

| Processing Stage | Variance Explained by Head Motion | Relative Reduction vs. Minimal Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Processing | 73% [1] | Baseline |

| ABCD-BIDS Denoising | 23% [1] | 69% [1] |

This demonstrates that while modern denoising pipelines are effective, they do not eliminate motion-related variance entirely. The residual motion effect on functional connectivity (FC) is large; the motion-FC effect matrix has a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix, meaning connections are systematically weaker in participants who move more [1].

The SHAMAN Framework for Trait-Specific Motion Impact

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) method was developed to assign a motion impact score to specific trait-FC relationships [1]. It distinguishes whether motion causes overestimation or underestimation of a trait's true effect on functional connectivity. The following diagram outlines the SHAMAN workflow.

Applying SHAMAN to the ABCD dataset revealed that after standard denoising but without aggressive motion censoring, a substantial number of traits were affected by residual motion: 42% (19/45) of traits had significant motion overestimation scores, and 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores [1]. This underscores that motion artifact can bias results in both directions, complicating simple interpretations.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Motion Artifacts

Protocol 1: Quantifying Motion-FC Relationships in Large Cohorts

This methodology, used in a seminal study of 1,000 subjects, provides a framework for establishing the systematic effects of motion [2] [3].

- Subject Population & Grouping: A large sample of healthy controls is selected. Subjects are binned into groups (e.g., 10 groups) representing a continuum from least to most head motion. Groups should be balanced for age and sex where possible to isolate the effect of motion [2].

- Data Acquisition: Data should be acquired on matched MRI scanners using identical sequences. A resting-state fMRI protocol with parameters such as TR=3000 ms, TE=30 ms, and 3×3×3 mm voxels is typical. Head motion is restrained using foam padding and head clamps [2].

- Preprocessing: Standard preprocessing includes discarding initial volumes, slice-time correction, motion correction via rigid body registration, atlas registration, spatial smoothing (e.g., 6-mm FWHM), and temporal band-pass filtering (e.g., below 0.08 Hz) to remove high-frequency noise [2].

- Motion and FC Quantification: Head motion is quantified using mean displacement (frame-to-frame). Functional connectivity is calculated using correlation between regional time courses. Group difference maps are constructed to illustrate how functional connectivity varies between high-motion and low-motion groups [2].

Protocol 2: Simulated Motion and Validation of Correction Algorithms

This approach, also used in SPECT imaging, involves simulating motion to study its impact and test correction methods [5].

- Subject Data: Start with projection datasets from subjects with no motion and normal scan findings [5].

- Motion Simulation: Artificially introduce motion into the raw projection data. Simulations should include:

- Artifact Assessment: Reconstruct the images with simulated motion. Quantify the resulting artifactual perfusion defects using a validated quantitative scoring system (e.g., a 20-segment, 5-point scoring system) [5].

- Correction Validation: Apply the motion-correction algorithm to the simulated data. The efficacy of correction is measured by the significant improvement or normalization of the artificially induced defects [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Motion Artifact Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Relevance to Motion Research |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Motion Tracking System | Tracks head position in real-time using a marker attached to the subject. | Enables prospective motion correction (PMC) and quantitative assessment of head motion trajectories [6]. |

| Moiré Phase Tracking Marker | A specific type of MR-compatible optical marker. | Used with in-bore camera systems for high-precision head motion tracking [6]. |

| Marker Fixations (Mouth Guard, Nose Bridge) | Devices to rigidly attach the optical marker to the subject's head. | Critical for robust PMC; fixation type (e.g., mouth guard vs. nose bridge) impacts correction performance due to skin slippage [6]. |

| Foam Head Pads & Head Clamps | Physical restraints to limit head movement inside the coil. | Standard issue to minimize subject motion during scanning [2]. |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | A scalar quantity summarizing frame-to-frame head movement. | The primary metric for quantifying the degree of head motion in a scan; used for censoring (scrubbing) [1]. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A blind source separation algorithm (e.g., as implemented in FSL, GIFT). | Decomposes fMRI data to allow for identification and removal of motion-related noise components (N-ICs) [4]. |

| Motion Impact Score (SHAMAN) | A statistical software method for quantifying trait-specific motion confounds. | Determines if a specific trait-FC relationship is spuriously influenced by motion, indicating over- or underestimation [1]. |

Functional connectivity MRI (fcMRI) has become a cornerstone technique for exploring the functional architecture of the brain, widely applied to study differences across the lifespan, clinical diagnoses, and individual traits [2]. However, a significant confounding factor in fcMRI research is in-scanner head motion, which introduces systematic bias into connectivity estimates that is not completely removed by standard denoising algorithms [2] [1]. This artifact is particularly problematic because head motion varies considerably among individuals within the same population and is often correlated with traits of interest; for instance, children move more than adults, older adults more than younger adults, and patient populations often move more than controls [2]. The resulting distance-dependent effect—where motion artifact systematically inflates short-range functional connectivity while diminishing long-range connectivity—can produce difference maps that could be mistaken for genuine neuronal effects [2] [1]. This technical review examines the mechanisms, evidence, and methodological implications of this distance-dependent effect within the broader context of head motion impact on functional connectivity research.

Quantitative Evidence of Distance-Dependent Effects

Empirical studies across large datasets consistently demonstrate that head motion has systematic, spatially-specific effects on fcMRI network measures. The core finding is an inverse relationship between motion and connection length.

Table 1: Observed Effects of Head Motion on Functional Connectivity Measures

| Network Measure | Direction of Change with Motion | Effect Size Characteristics | Primary Brain Networks Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Range Connectivity | Decrease [ [2] [1] | Strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ ≈ -0.58) with average FC [1] | Default Network, Frontoparietal Control Network [2] |

| Short-Range Connectivity | Increase [2] | Local functional coupling elevated | Local/Regional Circuits [2] |

| Interhemispheric Homotopic Connectivity | Variable | Increase in motor regions [2] | Motor Network [2] |

Analysis of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (n = 7,270) reveals that after standard denoising, the motion-FC effect matrix shows a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix, indicating that connections stronger in low-motion participants are precisely those most diminished in high-motion participants [1]. This effect persists even after rigorous motion censoring at framewise displacement (FD) < 0.2 mm (Spearman ρ = -0.51) [1].

The decrease in FC due to head motion is often larger than trait-related FC changes, potentially obscuring or mimicking genuine effects [1]. Group comparisons show that differences in motion levels alone can yield FC difference maps resembling neuronal effects, with motion-associated decreases particularly prominent in default and frontoparietal control networks—networks characterized by coupling among distributed association cortex regions [2].

Methodological Protocols for Motion Effect Characterization

Experimental Design and Data Acquisition

Characterizing motion effects requires carefully controlled datasets. Key protocols include:

- Participant Selection: Large samples (n > 1000) of healthy young adults minimize confounding clinical factors while capturing natural motion variability [2]. The ABCD Study leverages n = 11,874 children aged 9-10 for developmental motion analysis [1].

- MRI Acquisition Parameters: Data should be collected on matched scanners using identical sequences. Standard parameters include: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 85°, 3×3×3 mm voxels, 47 slices aligned to AC-PC plane [2]. Multi-echo T1-weighted structural images support registration [2].

- Motion Restriction: Foam pillows and extendable padded head clamps minimize movement while earplugs attenuate scanner noise [2].

- Resting-State Protocol: Two BOLD runs of 124 volumes each after discarding first 4 volumes for T1-equilibration, with instructions to rest with eyes open while staying still [2].

Functional MRI Data Preprocessing

Standard preprocessing pipelines include:

- Motion Correction: Rigid body translation and rotation from each volume to the first volume using algorithms like FSL's MCFLIRT [2].

- Spatial Processing: Slice-time correction, atlas registration to MNI space via affine and non-linear transforms, resampling to 2-mm isotropic voxels, spatial smoothing (6-mm FWHM Gaussian kernel) [2].

- Temporal Filtering: Band-pass filtering retaining frequencies below 0.08 Hz to remove constant offsets and linear trends [2].

- Nuisance Regression: Removing spurious variance via regression of motion parameters, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid signals [2].

Motion Quantification Approaches

- Framewise Displacement (FD): Summarizes volume-to-volume head displacement by combining translational and rotational movement [1].

- Motion Impact Score (SHAMAN): A novel method applying Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks to quantify trait-specific motion effects on FC, distinguishing between overestimation and underestimation of trait-FC relationships [1].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway through which head motion introduces distance-dependent artifacts in functional connectivity estimates:

Diagram 1: Motion Artifact Propagation Pathway

The experimental workflow for detecting and quantifying motion-related artifacts in large datasets follows a systematic pipeline:

Diagram 2: Motion Artifact Detection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Methodological Components for Motion-Related FC Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Role | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | Comprehensive denoising algorithm incorporating multiple artifact removal techniques | Global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion timeseries regression, despiking/interpolation [1] |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies volume-to-volume head movement | Summarizes translational and rotational displacement; used for censoring threshold determination [1] |

| SHAMAN Methodology | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact on FC | Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks; distinguishes overestimation vs. underestimation [1] |

| Motion Censoring (Scrubbing) | Removes high-motion volumes from analysis | Exclusion of frames exceeding FD threshold (e.g., 0.2 mm); balances artifact reduction with data retention [1] |

| Alternative FC Metrics | Reduces motion sensitivity compared to Pearson correlation | Partial correlation, coherence, information theory-based measures offer different motion sensitivity profiles [7] |

| HCP & ABCD Datasets | Large-scale reference datasets for motion artifact characterization | Human Connectome Project (HCP), Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study provide normative motion data [1] [7] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The distance-dependent effect of head motion on functional connectivity represents a fundamental methodological challenge with substantive implications for interpretation of neuroimaging findings. The systematic inflation of short-range connections and diminution of long-range connections creates a distinct spatial signature that can mimic or obscure genuine neurobiological effects, particularly in studies comparing groups with inherent motion differences (e.g., children vs. adults, patients vs. controls) [2] [1].

The SHAMAN framework represents a significant methodological advance by enabling researchers to assign a motion impact score to specific trait-FC relationships, distinguishing between situations where motion causes overestimation versus underestimation of effects [1]. Application to the ABCD dataset revealed that even after standard denoising, 42% of traits exhibited significant motion overestimation scores and 38% had significant underestimation scores [1].

Choice of functional connectivity metric significantly influences motion sensitivity. Studies comparing eight different FC measures report that full correlation has relatively high residual distance-dependent relationship with motion compared to partial correlation, coherence, and information theory-based measures [7]. However, this disadvantage may be offset by higher test-retest reliability and fingerprinting accuracy, creating a trade-off that researchers must consider based on study-specific priorities [7].

Future methodological development should focus on integrated approaches that combine optimized denoising pipelines with trait-specific motion impact assessments. The convergence of large-scale datasets like ABCD and HCP with machine learning approaches offers promising avenues for developing more robust motion correction strategies that preserve neural signals while effectively removing motion-related artifacts [1].

In-scanner head motion represents a significant and pervasive confound in neuroimaging, systematically biasing estimates of functional and structural connectivity. This artifact is not random; it exhibits strong correlations with participant characteristics such as age, clinical status, and cognitive traits, potentially leading to spurious findings in brain-behavior association studies. For researchers investigating neurological or psychiatric disorders, failure to adequately account for motion can result in false positive results where observed group differences reflect motion artifact rather than genuine neurobiological phenomena [1]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms through which motion introduces bias, details its specific correlations with subject traits, and provides evidence-based methodologies for its detection and mitigation within the broader context of connectivity research.

The Systematic Nature of Motion Artifact

Head motion is the largest source of artifact in functional and structural MRI signals, introducing non-random, systematic bias that persists despite standard denoising algorithms [1]. The impact of motion on resting-state functional connectivity MRI (rs-fcMRI) is particularly pronounced because the timing of underlying neural processes is unknown, making it difficult to distinguish neural signal from artifact [1] [8].

Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

Motion artifacts demonstrate consistent spatial patterns in functional connectivity data. Analyses of large datasets, including the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, reveal that head motion decreases long-distance connectivity while increasing short-range connectivity [1]. This pattern is most notable in default mode network regions [1]. The motion-FC effect matrix shows a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix, indicating that participants who moved more consistently showed weaker connection strengths across functional connections [1].

In diffusion MRI for structural connectivity, motion introduces length-dependent biases. Increased head motion is associated with reduced structural connectivity estimates for high-consistency network edges (both short- and long-range), while inflating estimates for low-consistency edges that are primarily shorter-range [9]. This occurs because motion can promote spurious streamline propagation in low-fractional anisotropy regions while causing premature streamline termination in high-FA regions [9].

Table 1: Characteristics of Motion Artifacts in Functional and Structural Connectivity

| Feature | Impact on Functional Connectivity | Impact on Structural Connectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Pattern | Decreased long-distance connectivity; Increased short-range connectivity [1] | Reduced connectivity for high-consistency edges; Inflated connectivity for low-consistency edges [9] |

| Network Effects | Most pronounced in default mode network [1] | Biases both local and global network topology [9] |

| Effect Size | Larger than trait-FC effect sizes of interest [1] | Significant enough to confound developmental inferences [9] |

| Persistence | Remains after denoising and motion censoring [1] [8] | Persists after quality assurance and retrospective correction [9] |

Motion Correlations with Demographic and Clinical Variables

Age and Motion

Substantial evidence demonstrates a strong correlation between age and in-scanner head motion, creating a critical confound in developmental neuroimaging studies. Younger participants consistently exhibit greater head motion than older participants, which can create the false appearance of developmental changes in connectivity [9]. This relationship is so pronounced that studies specifically must match age across high-motion and low-motion groups to avoid confounding [8]. In one study of 348 adolescents, researchers created age- and gender-matched high-motion and low-motion subsamples to isolate motion effects from developmental effects [8].

Clinical Status and Motion

Numerous clinical populations characterized by behavioral regulation difficulties show elevated motion during scanning. Research has specifically identified that "study participants with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism have higher in-scanner head motion than neurotypical participants" [1]. This association creates a systematic bias where clinical groups appear to have altered connectivity patterns that may actually reflect motion artifacts rather than neuropathology [1]. For example, early studies concluding that autism decreases long-distance FC may have actually detected confounding from increased head motion in autistic participants [1].

Table 2: Populations with Systematic Motion Correlations and Associated Risks

| Population | Motion Relationship | Potential for Spurious Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Children & Adolescents | Significantly higher motion than adults [8] [9] | False developmental trends; Exaggerated age effects [9] |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | Elevated motion compared to neurotypical controls [1] | Artificial reduction in long-distance connectivity [1] |

| ADHD | Elevated motion compared to neurotypical controls [1] | Misattributed functional connectivity patterns [1] |

| Psychiatric Disorders | Generally elevated motion (multiple disorders) [1] | False positive group differences in network architecture [1] |

Quantifying Motion and Its Impact

Motion Quantification Metrics

Framewise displacement (FD) provides a scalar value in millimeters of how much a participant moves from one volume to the next [10]. Mean FD values allow classification of scans as high-motion or low-motion, with thresholds typically set at 0.10-0.20 mm [10]. The DVARS metric quantifies the rate of change of BOLD signal across the entire brain at each frame [8]. Both metrics are routinely calculated during quality assessment of fMRI data.

The SHAMAN Framework for Trait-Specific Motion Impact

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) framework represents a novel approach for assigning a motion impact score to specific trait-FC relationships [1]. Unlike generic motion quantification, SHAMAN distinguishes between motion causing overestimation or underestimation of specific trait-FC effects by capitalizing on the observation that traits are stable over the timescale of an MRI scan while motion varies from second to second [1].

The method works by measuring differences in correlation structure between split high- and low-motion halves of each participant's fMRI timeseries. When trait-FC effects are independent of motion, the difference between halves will be non-significant. A significant difference indicates that state-dependent motion impacts the trait's connectivity. A motion impact score aligned with the trait-FC effect direction indicates overestimation, while an opposite score indicates underestimation [1].

Application of SHAMAN to 45 traits from n=7,270 participants in the ABCD Study revealed that after standard denoising without motion censoring, 42% (19/45) of traits had significant motion overestimation scores and 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores [1].

Mitigation Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Pre-Scan Motion Reduction Protocols

Implementing a mock scan protocol prior to actual scanning significantly reduces head motion in pediatric participants [10]. This approach involves placing participants in an environment designed to mimic the real scanning environment, desensitizing them, and training them to limit movement. When combined with in-scan methods like weighted blankets and incentive systems, mock scanning enables acquisition of low-motion fMRI data even during extended 60-minute scan protocols in children ages 7-17 [10].

Comparative studies show formal mock scan protocols dramatically reduce high-motion scans. At a threshold of 0.10 mm mean FFD, 71.4% of scans from an informal mock scan group were classified as high-motion, compared to only 32.3% from the formal mock scan group [10]. This difference was statistically significant (Pearson Chi-square = 21.76, P < 0.001), demonstrating the efficacy of structured preparation protocols [10].

Post-Hoc Processing and Denoising Methods

Multiple denoising approaches have been developed to mitigate motion artifacts in post-processing. The ABCD-BIDS pipeline, which includes global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter timeseries regression, achieves a 69% relative reduction in motion-related signal variance compared to minimal processing alone [1]. However, even after this comprehensive denoising, 23% of signal variance remains explained by head motion [1].

Motion censoring (or "scrubbing") involves excluding high-motion fMRI frames from analysis. This approach significantly reduces spurious findings, but creates tension between removing motion-contaminated volumes and retaining sufficient data, particularly for individuals with high motion who may exhibit important variance in traits of interest [1]. Censoring at framewise displacement < 0.2 mm reduces significant motion overestimation from 42% to 2% of traits, though it does not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores [1].

Table 3: Efficacy of Motion Mitigation Strategies Across Studies

| Mitigation Strategy | Protocol Details | Efficacy & Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Scanner Training | Environment mimicking real scanner; Desensitization training; Typically 20-40 minutes [10] | Reduces high-motion scans (>0.10mm FFD) from 71.4% to 32.3%; Effective in children with ASD [10] |

| ABCD-BIDS Denoising | Global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, motion parameter regression [1] | 69% relative reduction in motion-related variance; 23% variance remains [1] |

| Motion Censoring (FD < 0.2mm) | Exclusion of high-motion frames from analysis [1] | Reduces motion overestimation from 42% to 2% of traits; Does not address underestimation [1] |

| FIRMM (Real-time Monitoring) | Real-time head motion analysis; Scan until sufficient low-motion data acquired [10] | Effective for resting-state; Limited utility for task-based fMRI with fixed timing [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for Motion Confound Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies head motion between consecutive volumes | Primary metric for motion censoring; Thresholds typically 0.1-0.2mm [10] |

| SHAMAN Framework | Assigns trait-specific motion impact scores | Distinguishes overestimation vs. underestimation; Requires split-half analysis [1] |

| Mock Scanner Environment | Acclimates participants to scanning environment | Reduces motion in pediatric and clinical populations; Critical for long protocols [10] |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | Comprehensive denoising pipeline | Open-source standardized processing; Includes multiple regression approaches [1] |

| FIRMM Software | Real-time motion monitoring during acquisition | Enables scanning until sufficient low-motion data acquired; Limited for task fMRI [10] |

| Motion Censoring (Scrubbing) | Removes high-motion frames from analysis | Powerful for reducing false positives; Risk of biasing sample distribution [1] |

In-scanner head motion remains a critical confound in neuroimaging research, exhibiting systematic correlations with age, clinical status, and cognitive traits that threaten the validity of brain-behavior associations. The spatial, temporal, and spectral characteristics of motion artifacts introduce non-random bias that persists despite sophisticated denoising approaches. Researchers must implement comprehensive mitigation strategies spanning pre-scan preparation, in-scan monitoring, and post-hoc processing while quantitatively evaluating trait-specific motion impacts using frameworks like SHAMAN. As the field moves toward larger datasets and more diverse populations, acknowledging and addressing motion as a confound rather than mere noise is essential for generating valid neurobiological insights.

Within the field of functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (fcMRI), head motion is recognized not as a mere nuisance, but as a significant confounding variable that can systematically bias estimates of brain network organization [11]. The persistence of motion artifacts, even after standard preprocessing, poses a particular threat to the validity of studies investigating individual differences, such as those related to clinical status, aging, or genetics [2] [3]. This technical guide provides a quantitative synthesis of the effect sizes associated with head motion on functional connectivity measures and contrasts them with effects attributed to neurobiological traits. Furthermore, it details rigorous experimental protocols and analytical toolkits essential for mitigating motion-related bias, thereby bolstering the reliability of neuroimaging findings in basic research and drug development.

Quantitative Data Synthesis: Motion vs. Trait Effects

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from the literature, comparing the effect sizes of head motion on functional connectivity with those of representative neurobiological traits.

Table 1: Effect Sizes of Head Motion on Functional Connectivity Metrics

| Functional Connectivity Metric | Reported Effect Size / Correlation | Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Network Connectivity | Decreased coupling with higher motion | Healthy Adults (n=1000) | [2] [3] |

| Frontoparietal Control Network | Decreased coupling with higher motion | Healthy Adults (n=1000) | [2] [3] |

| Local/Short-Range Connectivity | Increased coupling with higher motion | Healthy Adults (n=1000) | [2] [3] |

| Inter-hemispheric Motor Connectivity | Increased coupling with higher motion | Healthy Adults (n=1000) | [2] [3] |

| Whole-Brain Functional Connectivity | FC profiles significantly predict motion (r = 0.09 ± 0.08; p < 10⁻³) after regression | Human Fetuses (n=120 scans) | [12] |

| Sensory & Default Mode Networks | Significant affectation by head motion; direction of effect varied across brain | Newborns (n=575) | [13] |

Table 2: Effect Sizes of Representative Neurobiological Traits on Functional Connectivity

| Neurobiological Trait | Reported Effect Size / Correlation | Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autistic Traits (AQ) - Social Reward | Attenuated preference for biological motion with higher AQ scores | Neurotypical Adults (n=105) | [14] |

| Autistic Traits (AQ) - Attention Switching | Robust association with biological motion naturalness perception | Neurotypical Adults | [15] |

| Gestational Age at Scan | Improved prediction from FC data after motion censoring (Accuracy: 55.2% with vs. 44.6% without censoring) | Human Fetuses (n=120 scans) | [12] |

| Biological Sex | Improved prediction from FC data after motion censoring | Human Fetuses (n=120 scans) | [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Impact Quantification

Large-Sample Group Comparison Protocol

This protocol, derived from Van Dijk et al. (2012), is designed to systematically quantify motion effects across a large cohort [2] [3].

- Subject Selection & Grouping: Acquire a large sample of healthy control subjects (e.g., n > 1000). Characterize the distribution of head motion, typically summarized as Mean Frame-Wise Displacement (Mean FD). Divide the sample into deciles or similar groups based on Mean FD, from the least (Group 1) to the most (Group 10) motile subjects. Ensure age is evenly distributed across groups; sex distribution may require statistical control.

- MRI Acquisition: Data should be collected on matched scanners using identical sequences. A typical resting-state fMRI protocol uses a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with parameters: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 85°, and isotropic voxels (e.g., 3mm³). Two resting-state runs of ~124 volumes each are acquired while participants fixate on a cross, with head motion restrained using foam padding and cushions.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Basic Preprocessing: Discard initial volumes for T1 equilibration. Perform slice-timing correction and rigid-body realignment of all volumes to a reference volume to generate 6 head motion parameters (3 translation, 3 rotation).

- Spatial Processing: Register functional data to a standard template space. Apply spatial smoothing (e.g., 6mm FWHM Gaussian kernel).

- Temporal Filtering: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 0.008-0.08 Hz) to retain low-frequency fluctuations.

- Functional Connectivity Analysis: Extract mean BOLD time series from pre-defined regions of interest (ROIs) encompassing major functional networks (e.g., Default Mode, Frontoparietal, Motor). Compute pairwise correlation coefficients between all ROIs, then apply Fisher's z-transformation to improve normality.

- Quantification of Motion Effects: Calculate functional connectivity metrics for each network (e.g., mean within-network correlation). Correlate these metrics with continuous measures of head motion (e.g., Mean FD) across the entire sample. Alternatively, compute group difference maps (e.g., Group 1 vs. Group 10) to visualize networks most susceptible to motion artifacts.

Censoring (Scrubbing) Efficacy Protocol

This protocol, validated in neonates, fetuses, and adults, assesses the utility of volume censoring for mitigating motion effects [13] [12].

- Data Foundation: Start with preprocessed data that has undergone realignment and nuisance regression (including 6 motion parameters and their derivatives, and optionally, physiological signals).

- Frame-Wise Displacement (FD) Calculation: Compute FD for every volume in the time series. FD is the sum of the absolute derivatives of the 3 translational and 3 rotational motion parameters. Rotational displacements are converted from radians to millimeters by assuming a brain radius (e.g., 50 mm for adults, or a fetal-specific estimate).

- Censoring Threshold Application: Identify and flag volumes where FD exceeds a predefined threshold. Common thresholds in adult literature are 0.2-0.5 mm [13]. Fetal and neonatal studies may use higher thresholds (e.g., 1.5 mm) due to greater inherent motion [12].

- Data Exclusion: Remove all flagged high-motion volumes from the time series analysis. Interpolating across large censored segments is not recommended; instead, analyses are performed on the retained "clean" data.

- Efficacy Benchmarking:

- Motion-FC Correlation: Correlate subject-level mean FD with whole-brain FC matrices after preprocessing with and without censoring. Effective censoring should reduce this correlation to near zero.

- Neurobiological Prediction: Use machine learning models to predict neurobiological traits (e.g., gestational age, sex) from FC data. Improved prediction accuracy with censored data indicates enhanced signal-to-noise ratio.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway through which head motion introduces artifact into functional connectivity estimates and the primary intervention points for mitigation strategies.

Diagram: Pathway of Motion Artifact and Mitigation in fcMRI. This workflow outlines how physical head motion introduces non-biological signal changes that propagate through data processing, ultimately biasing connectivity estimates. Key mitigation strategies (green) intervene at critical points to restore validity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Motion Mitigation Research

| Item / Software Tool | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Motion Research |

|---|---|---|

| Frame-Wise Displacement (FD) | A scalar summary metric of volume-to-volume head motion. | Primary quantitative measure for motion magnitude; used to define censoring thresholds and correlate with FC outcomes [13] [11]. |

| Nuisance Regressors (6-36 parameters) | Time series of head position (translation, rotation) and their temporal derivatives, squares, and lagged values. | Model widespread motion effects via regression, removing variance associated with motion parameters from BOLD signal [2] [12]. |

| Volume Censoring (Scrubbing) | The process of identifying and excluding high-motion volumes (based on FD) from analysis. | Targets focal, high-motion artifacts that nuisance regression fails to fully remove, crucial for reducing motion-FC correlations [13] [12]. |

| ANTHROPOMETRIC BRAIN RADIUS | A assumed radius (e.g., 50 mm) to convert rotational parameters from radians to millimeters. | Essential for FD calculation, ensuring rotational and translational motions are combined on a consistent scale. Values may vary for pediatric populations. |

| High-Quality T1-Weighted Anatomical | High-resolution structural scan (e.g., MP-RAGE). | Serves as registration target for functional data, improving cross-subject alignment and reducing misregistration artifacts exacerbated by motion. |

| Software (e.g., AFNI, FSL, BioImage Suite) | Suites for neuroimaging data preprocessing and analysis. | Implement standard pipelines for realignment, regression, censoring, and connectivity analysis [13] [12]. |

| eXtensible Connectivity Pipeline (XCP) | A dedicated software pipeline for fcMRI confound regression and denoising. | Implements validated, high-performance denoising strategies that combine multiple model features to target motion artifacts [16]. |

The quantitative evidence is unequivocal: head motion induces systematic and spatially complex artifacts in functional connectivity, with effect sizes substantial enough to mimic or obscure genuine neurobiological effects [2] [3] [11]. The persistence of motion-FC correlations after standard nuisance regression underscores the necessity of advanced mitigation strategies, with volume censoring emerging as a particularly effective tool [13] [12]. For the research and drug development community, rigorous motion correction is no longer optional but fundamental to data integrity. Adopting standardized protocols that combine nuisance regression with stringent censoring, benchmarking efficacy via motion-FC correlations and neurobiological prediction accuracy, and transparently reporting motion metrics are critical steps toward generating reliable, reproducible, and interpretable functional connectivity findings.

Motion Correction Arsenal: From Confound Regression to Censoring and Real-Time Monitoring

In resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the correlation between blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) time courses from different brain regions serves as a fundamental metric for estimating functional connectivity (FC) [17]. However, the reliability and robustness of these measurements are critically dependent on minimizing the influence of confounding noise, with in-scanner head motion representing the most significant source of artifact [1] [13]. Even sub-millimeter head movements—as small as 0.1 mm—can systematically bias both within- and between-group effects during fMRI analysis [18]. This problem is particularly acute in studies of populations with naturally higher motion characteristics, such as children, older adults, or patients with neurological or psychiatric disorders, where motion can spuriously influence trait-FC relationships and lead to false positive results [1].

The confounding effects of motion on functional connectivity are spatially systematic, often causing decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity, most notably within the default mode network [1]. In large-scale brain-wide association studies (BWAS) involving thousands of participants, such as the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, the need for rigorous motion correction is paramount, as residual motion artifacts can persist even after extensive denoising pipelines [1]. The challenge is further compounded in dynamic functional connectivity (DFC) studies, where temporal fluctuations in correlation estimates may reflect nuisance effects rather than genuine neural dynamics [17]. Within this context, nuisance regression emerges as an essential preprocessing step to mitigate these artifacts and ensure the validity of functional connectivity findings.

Core Nuisance Regression Methodologies

Motion Parameter Regression

Volume realignment, which aligns reconstructed volumes by calculating motion parameters based on a solid-body model of the head and brain, represents the initial step in addressing head motion [18]. Following this realignment, the calculated motion parameters can be incorporated as regressors in general linear model (GLM) analyses to statistically remove motion-related artifacts from the BOLD signal [18]. Two primary parameter sets are commonly used:

- 6-Parameter Model: Includes three translation (x, y, z) and three rotation (pitch, roll, yaw) parameters derived from volume realignment [18].

- Friston 24-Parameter Model: Expands on the basic model by including the 6 motion parameters from both the current and preceding volumes, plus each of these values squared [18].

Framewise displacement (FD) and DVARS are complementary measures used to identify volumes contaminated by excessive motion. FD is computed from derivatives of the six rigid-body realignment parameters and provides a single index of head displacement, while DVARS represents the root mean squared change in BOLD signal from volume to volume [18]. These metrics facilitate the implementation of censoring (or "scrubbing") techniques, where volumes exceeding predetermined thresholds (typically FD > 0.2-0.5 mm) are excluded from analysis [18] [1]. It is important to note that scrubbing disrupts the temporal structure of data, precluding frequency-based analyses but remaining effective for seed-based correlation approaches [18].

Global Signal Regression

Global signal regression (GSR) involves removing the global mean signal—computed as the average signal across all voxels within the brain for each time point—from the BOLD time series via linear regression [18] [19]. The global signal is assumed to reflect a combination of resting-state fluctuations, physiological noise, and other non-neural signals [18]. Despite ongoing controversy in the field, GSR has been shown to facilitate the detection of localized neuronal signals and improve the specificity of functional connectivity analysis [18].

The computation of the global signal varies across studies, with some calculating it after minimal preprocessing (image registration, slice-timing correction, spatial smoothing) and others deriving it after removing additional nuisance regressors [19]. Normalization approaches also differ, with some studies employing per-voxel percent signal change calculations and others using grand-mean scaling across all voxels and time points [19]. The effect of GSR on connectivity measures is complex, with evidence suggesting it can increase the detection of system-specific correlations and enhance anatomical specificity, though it may also introduce artificial negative correlations [19].

Physiological Signal Regression

Physiological noise originating from cardiac and respiratory cycles represents another significant confound in fMRI data. Several strategies have been developed to address these artifacts:

Anatomical CompCor (aCompCor) identifies noise regions-of-interest (ROIs) in areas unlikely to be modulated by neural activity, primarily white matter (WM) and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) [18]. Principal component analysis (PCA) is applied to the time series data from these noise ROIs, and the significant components are included as covariates in a GLM to estimate and remove physiological noise [18]. This approach offers advantages over simple mean WM/CSF signal regression by better accounting for voxel-specific phase differences in physiological noise.

Temporal CompCor (tCompCor) operates on a similar principle but identifies noise ROIs based on temporal characteristics rather than anatomy, specifically selecting voxels with high temporal standard deviation that are likely dominated by physiological noise [18].

RETROICOR represents another physiological noise correction approach that uses external measurements of cardiac and respiratory activity to create regressors that model these periodic physiological processes [20]. Implementation considerations include whether to apply RETROICOR before or after motion correction, with some evidence supporting its application before motion correction to maintain accurate slice timing information [20].

Quantitative Comparisons of Nuisance Regression Efficacy

Table 1: Impact of Different Denoising Strategies on Motion-Related Variance

| Denoising Approach | Variance Explained by Motion | Key Findings | Reference/Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Processing (motion correction only) | 73% of signal variance | Motion is the dominant source of artifact without comprehensive denoising | [1] |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline (GSR, respiratory filtering, motion regression, despiking) | 23% of signal variance (69% relative reduction) | Significant improvement but substantial residual motion influence remains | [1] |

| Motion Censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) + Denoising | Reduced significant overestimation from 42% to 2% of traits | Highly effective against motion overestimation but less impact on underestimation | [1] |

| JumpCor (for large, infrequent motions) | Significant reduction in motion artifacts | Particularly effective for infant data with occasional large movements | [21] |

Table 2: Comparison of Nuisance Regression Method Strengths and Limitations

| Method | Primary Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Parameter Regression | General head motion artifacts | Directly addresses motion confounds; multiple parameter options (6, 24) | Cannot completely remove systematic motion effects on FC [13] |

| Global Signal Regression | Whole-brain signal fluctuations | Improves detection of localized signals; enhances specificity | Controversial; may introduce artificial negative correlations [18] [19] |

| aCompCor | Physiological noise from WM/CSF | Accounts for voxel-specific phase differences; data-driven | Requires accurate tissue segmentation |

| tCompCor | Physiological noise (temporal features) | No tissue segmentation needed; data-driven | May capture neural signal in high-variance voxels |

| Volume Censoring (Scrubbing) | High-motion time points | Effectively removes severely contaminated data | Reduces data length; disrupts temporal structure [18] |

| JumpCor | Occasional large movements | Preserves data in high-motion subjects (e.g., infants) | Segment-dependent baselines may complicate interpretation [21] |

Advanced Considerations and Integrated Methodologies

Dynamic Functional Connectivity and Nuisance Regression

In dynamic functional connectivity (DFC) studies, where sliding window correlations reveal temporal fluctuations in brain connectivity, nuisance regression faces additional challenges. Research shows that DFC estimates can be significantly correlated with temporal fluctuations in the magnitude (norm) of various nuisance regressors, even when correlations between the nuisance and seed time courses are relatively small [17]. Importantly, standard nuisance regression applied to the entire scan does not necessarily eliminate the relationship between DFC estimates and nuisance norms [17]. This persistence occurs because nuisance regression affects the signal space, altering the relationship between time courses in ways that may not uniformly benefit DFC estimates.

Theoretical bounds on the difference between DFC estimates obtained before and after nuisance regression reveal fundamental limitations in the efficacy of standard approaches for dynamic analyses [17]. Specifically, the difference in sliding window correlations before and after regression depends on the norms of the nuisance regressors and their relationship to the seed time courses within each window [17]. This understanding has led to investigations of window-specific nuisance regression, where regression is performed separately within each sliding window, though this approach introduces its own complexities and may not fully resolve the issues [17].

Motion Impact Assessment in Large-Scale Studies

The development of trait-specific motion impact scores, such as the Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN), represents an advance in quantifying residual motion effects on specific trait-FC relationships [1]. SHAMAN capitalizes on the relative stability of traits over time by measuring differences in correlation structure between split high- and low-motion halves of each participant's fMRI timeseries [1]. This method can distinguish between motion causing overestimation or underestimation of trait-FC effects and assigns statistical significance to these motion impacts [1].

Application of this approach to the ABCD Study revealed that after standard denoising without motion censoring, 42% (19/45) of traits had significant motion overestimation scores and 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores [1]. Censoring at FD < 0.2 mm reduced significant overestimation to 2% (1/45) of traits but did not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores, highlighting the complex relationship between censoring and different types of motion bias [1].

Special Considerations for Pediatric and Special Populations

In neonatal and infant populations, head motion presents unique challenges due to more frequent and larger movements during nonsedated sleep [21] [13]. Studies with 1-month-old infants have reported occasional large head motions of 1-24 mm (median 3.0 mm) separated by relatively quiet periods, which conventional exclusion criteria would improperly eliminate from analysis [21]. In these populations, censoring of high-motion volumes using framewise displacement significantly reduces the confounding effects of head motion on functional connectivity estimates [13].

The JumpCor technique has been developed specifically to address the pattern of infrequent large motions observed in infant data [21]. This approach identifies large jumps where volume-to-volume displacement exceeds a defined threshold (typically 1 mm) and generates regressors for every segment between these large jumps [21]. These segment regressors are then included as additional nuisance terms in the GLM, effectively modeling separate baselines for each stable segment between major movements [21].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Integrated Nuisance Regression Pipeline

A comprehensive nuisance regression protocol typically incorporates multiple strategies in sequence. The following workflow represents a robust approach for resting-state fMRI data:

- Volume Realignment: Perform rigid-body motion correction using 6-parameter model [18].

- Motion Parameter Calculation: Compute framewise displacement (FD) and DVARS for quality assessment and censoring decisions [18].

- Tissue Segmentation: Generate accurate white matter and cerebrospinal fluid masks [18] [22].

- Noise Component Extraction: Calculate principal components from WM and CSF masks for aCompCor [18].

- Global Signal Calculation: Compute whole-brain mean signal time course [18] [19].

- Integrated Regression: Perform a single regression step incorporating motion parameters, aCompCor components, global signal, and other relevant nuisances [20].

- Temporal Filtering: Apply band-pass filter (typically 0.008-0.1 Hz) to remove slow drifts and high-frequency noise [18].

- Volume Censoring: Remove volumes with FD exceeding threshold (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mm) from analysis [18] [1].

Figure 1: Comprehensive Nuisance Regression Workflow

Table 3: Essential Tools for Nuisance Regression in Functional Connectivity Research

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep [22] | Automated preprocessing pipeline | Generates standardized preprocessed data and confound regressors; provides anatomical and functional derivatives |

| AFNI [21] [13] | MRI data analysis and visualization | Implements volume realignment, censoring, and various regression techniques |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline [1] | Standardized denoising for large datasets | Incorporates GSR, respiratory filtering, motion regression, and despiking |

| CompCor Implementation [18] | Physiological noise component extraction | Identifies noise components from WM/CSF regions via PCA |

| SHAMAN Framework [1] | Trait-specific motion impact scoring | Quantifies residual motion effects on specific trait-FC relationships |

| JumpCor Algorithm [21] | Segment-based baseline correction | Addresses infrequent large motions in special populations |

| FD/DVARS Calculators [18] | Motion metric computation | Quantifies framewise displacement and BOLD signal change for censoring |

Nuisance regression strategies for addressing motion parameters, global signal, and physiological artifacts remain essential yet imperfect tools in functional connectivity research. The persistent influence of head motion on FC estimates, even after extensive denoising, underscores the need for continued methodological refinement [1] [17]. No single approach provides a complete solution, with each method introducing different trade-offs between artifact removal and signal preservation.

The emerging consensus supports integrated pipelines that combine multiple regression strategies with appropriate censoring thresholds tailored to specific research questions and population characteristics [18] [1] [13]. Furthermore, the development of trait-specific motion impact assessments represents a promising direction for quantifying and communicating residual confounding in brain-behavior association studies [1]. As the field advances, increased transparency in reporting preprocessing choices and their potential impacts on functional connectivity estimates will be crucial for interpreting and replicating findings across the research landscape.

The Role and Trade-offs of Censoring ('Scrubbing') High-Motion Volumes

In-scanner head motion presents a formidable methodological challenge in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), particularly for studies of functional connectivity (FC). Motion artifacts have the potential to introduce systematic bias and produce spurious findings, especially when comparing groups that inherently differ in their motion characteristics, such as children versus adults or clinical populations versus healthy controls [11] [23]. Among the numerous strategies developed to mitigate these effects, censoring, or "scrubbing," has emerged as a widely used technique. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the role, methodological implementation, and critical trade-offs associated with the practice of scrubbing high-motion volumes in fMRI data analysis. Framed within broader research on motion's impact on FC estimates, this guide details experimental protocols, summarizes quantitative performance data, and outlines a practical toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of fMRI preprocessing.

The Problem of Head Motion in fMRI

Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

Head motion systematically corrupts the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal in a non-random manner. Its effects are spatially heterogeneous; motion is typically minimal near the atlas vertebrae and increases with distance from this point, with frontal cortex often showing the greatest displacement due to the biomechanics of "nodding" movements [11]. This results in a distance-dependent bias on functional connectivity metrics, artificially inflating short-range correlations and attenuating long-range connections [23] [1]. This specific pattern poses a grave threat to the validity of network-level analyses, particularly affecting key networks like the default mode network (DMN) which involves long-range connections between medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate regions [23].

Temporally, motion artifacts manifest as both circumscribed, high-amplitude signal changes immediately following a movement event and longer-duration signal fluctuations that may persist for 8-10 seconds [11]. These nonlinear signal alterations arise from complex physical interactions including spin excitation history effects, interpolation artifacts during image reconstruction, and magnetic field interactions [11] [24]. Critically, because certain subject populations (e.g., children, elderly individuals, and those with neuropsychiatric conditions such as ADHD) tend to move more during scans, motion artifacts can introduce systematic confounds that are deeply entangled with the very effects researchers seek to discover [11] [23] [1].

Quantifying Head Motion

The first step in any scrubbing protocol is the quantification of in-scanner head motion. This is typically achieved through volume-based realignment procedures that generate several key metrics:

- Realignment Parameters (RPs): Six parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) describing the rigid-body transformation needed to align each volume to a reference volume [11].

- Framewise Displacement (FD): A scalar index that summarizes the volume-to-volume displacement by combining the derivatives of the six realignment parameters [11] [25]. Different implementations exist (e.g., Power vs. Jenkinson formulations), with the Jenkinson variant from FSL better aligning with voxel-specific displacement measures [11].

- DVARS: Measures the root mean square of the voxel-wise differentiated signal between consecutive volumes, capturing the rate of change of BOLD signal across the entire brain [26].

It is crucial to note that FD measures derived from volume-based realignment have limitations. They possess temporal resolution equivalent to the repetition time (TR) and thus cannot effectively capture within-volume motion. Furthermore, realignment estimates themselves may be inaccurate in images substantially corrupted by motion [11]. These limitations have motivated the development of more sophisticated motion quantification approaches, including slice-based motion parameters and data-driven measures [26] [24].

Scrubbing Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Motion-Based Scrubbing

The conventional scrubbing approach identifies and removes volumes affected by excessive motion based on directly measured head motion parameters.

Table 1: Standard Motion-Based Scrubbing Protocol

| Step | Description | Key Parameters & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Motion Estimation | Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD) and DVARS from realigned functional data. | FD threshold typically ranges from 0.2-0.5 mm; multiple implementations exist (Power, Jenkinson) [25] [1]. |

| 2. Threshold Selection | Define motion thresholds for identifying corrupted volumes. | Stringent thresholds (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) reduce false positives but increase data loss; optimal threshold may be study-dependent [1]. |

| 3. Volume Censoring | Generate a temporal mask to exclude identified volumes from analysis. | Often includes one preceding and two subsequent volumes to account for spin-history effects [27]. |

| 4. Data Analysis | Perform functional connectivity or task analysis using censored data. | General Linear Model (GLM) estimation omits censored volumes; can use interpolation or model discontinuous data [27]. |

The experimental validation of this protocol demonstrated that motion censoring in task fMRI data decreases variance in parameter estimates within- and across-subjects, reduces residual error in GLM estimation, and increases the magnitude of statistical effects [27]. These benefits were consistent across different subject cohorts (children, adolescents, and adults) and outperformed various motion regression techniques [27].

Data-Driven Scrubbing Approaches

Recent methodological advances have introduced data-driven scrubbing techniques that identify artifactual volumes based on patterns within the BOLD signal itself, rather than relying solely on motion estimates.

Projection Scrubbing is a novel, statistically-principled method that operates within an outlier detection framework. It employs strategic dimension reduction techniques, including Independent Component Analysis (ICA), to isolate artifactual variation in the data [26]. The method flags a volume as an outlier when its projection onto an artifactual component exceeds a certain statistical threshold (e.g., median absolute deviation). This approach specifically targets volumes that display abnormal signal patterns, potentially capturing motion-related artifacts that traditional FD thresholds might miss while avoiding unnecessary censoring of high-motion but usable data [26].

DVARS-based scrubbing identifies corrupted volumes based on the global signal change between consecutive time points. This measure captures abrupt signal changes that may result from motion or other sources of artifact. A key advantage is that DVARS can be calculated directly from the processed fMRI timeseries without requiring additional motion parameters [26].

Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of scrubbing methods based on empirical evaluations:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Scrubbing Methods

| Method | Residual Motion Artifact | Test-Retest Reliability | Fingerprinting Accuracy | Data Retention | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Scrubbing (FD) | Moderate to High [7] | High [7] | High [7] | Low [26] | Directly targets high-motion volumes; well-established. |

| Projection Scrubbing | Low [26] | Moderate [26] | Moderate to High [26] | High [26] | Detects various artifact types; avoids unnecessary censoring. |

| DVARS | Low to Moderate [26] | Moderate [26] | Moderate [26] | High [26] | Computationally simple; requires no motion parameters. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for implementing these different scrubbing methodologies:

The Critical Trade-offs: Data Retention versus Noise Reduction

The Fundamental Tension in Scrubbing

The central challenge in implementing scrubbing procedures lies in balancing two competing objectives: removing enough data to eliminate motion artifacts while retaining enough data to preserve statistical power and avoid biasing sample composition. Overly aggressive censoring (e.g., using very low FD thresholds) can result in the exclusion of a substantial portion of the dataset and potentially the systematic removal of participants from specific populations who move more, such as children or individuals with certain clinical conditions [26] [1]. This introduces a selection bias that threatens the external validity of study findings. Conversely, overly lenient censoring fails to adequately remove motion artifacts, resulting in residual spatial correlations between motion and functional connectivity that can produce both false positive and false negative results [1].

Quantitative Evidence of Trade-offs

Empirical research has quantified these trade-offs. In the large-scale Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, even after comprehensive denoising (ABCD-BIDS pipeline), residual motion artifacts persisted, with the motion-FC effect matrix showing a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix [1]. This indicates that participants who moved more exhibited systematically weaker long-range connections. Implementing censoring at FD < 0.2 mm reduced the number of traits with significant motion overestimation scores from 42% (19/45) to just 2% (1/45) of examined traits [1]. However, this same stringent censoring threshold did not reduce the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores [1], highlighting the complex relationship between censoring and different types of bias.

Data-driven scrubbing methods like projection scrubbing have demonstrated the ability to dramatically increase data retention while maintaining or improving data quality. These approaches censor significantly fewer volumes and consequently exclude far fewer entire participants from analysis compared to conventional motion scrubbing [26]. This has major implications for statistical power in population neuroscience studies, particularly for investigations of motion-correlated traits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of scrubbing procedures requires familiarity with both software tools and quantitative metrics. The following table details essential components of the scrubbing toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Scrubbing Implementation

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Metric | Quantifies volume-to-volume head motion. | Multiple calculation methods (Power vs. Jenkinson); threshold selection critical (0.2-0.5mm common) [11] [25]. |

| DVARS | Metric | Measures rate of BOLD signal change across brain. | Useful complement to FD; can detect artifacts not captured by motion parameters [26]. |

| fMRIPrep | Software | Robust preprocessing pipeline for fMRI data. | Standardizes preprocessing including motion correction; generates quality metrics and visual reports [28]. |

| SLOMOCO | Software | Implements slice-wise motion correction. | Addresses intravolume motion; can be combined with scrubbing [24]. |

| FIRMM | Software | Real-time motion monitoring. | Enables prospective quality control during scanning sessions [29]. |

| SHAMAN | Analytical Method | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact. | Helps determine if trait-FC relationships are confounded by motion [1]. |

Scrubbing represents a crucial defense against motion-induced artifacts in fMRI research, but its implementation requires careful consideration of fundamental trade-offs between noise reduction and data retention. The evidence indicates that while conventional motion-based scrubbing effectively reduces certain types of bias, it can introduce sample composition biases by disproportionately excluding data from high-motion participants. Emerging data-driven approaches like projection scrubbing offer promising alternatives that better balance these competing concerns. Future methodological developments will likely focus on improving the specificity of artifact detection, perhaps through the integration of multi-echo fMRI sequences, more sophisticated physiological noise modeling, and machine learning approaches that can better distinguish neural signal from complex motion-related artifacts. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal scrubbing strategy must be guided by the specific research question, participant population, and the particular vulnerability of the functional connectivity measures of interest to motion-related bias. As large-scale neuroimaging studies continue to grow in scope and importance, refining these methods to maximize both validity and inclusivity remains a critical frontier in the field.

Head motion presents a significant threat to the validity of functional connectivity estimates in neuroimaging research. Even small movements can induce spurious signal fluctuations that systematically bias findings, particularly in studies involving populations prone to greater motion such as children, elderly individuals, or those with neurological disorders [30] [11]. These motion-induced artifacts can create a systematic confound that correlates with variables of interest, potentially leading to false conclusions about brain development, clinical status, or treatment effects [11]. The problem is particularly acute in resting-state functional connectivity studies where no task model exists to guide the separation of signal from noise.

Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) have emerged as powerful data-driven approaches for mitigating these artifacts. Unlike simple motion regression or scrubbing techniques, these multivariate decomposition methods can identify and isolate complex, structured noise patterns that persist after standard preprocessing [31] [32]. ICA separates mixed signals into statistically independent components, effectively acting as a "cocktail party" solution that can distinguish neural signals from various noise sources [31]. PCA operates on a similar principle but separates signals based on orthogonal variance, making it particularly effective for capturing dominant noise patterns. When properly implemented, these techniques can significantly improve the sensitivity and specificity of functional connectivity measures, thereby enhancing the reliability of neuroscientific findings in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Theoretical Foundations of ICA and PCA for Artifact Removal

Core Mathematical Principles

Independent Component Analysis operates on the principle of blind source separation, aiming to decompose a multivariate signal into statistically independent non-Gaussian components. The fundamental model assumes that observed fMRI data ( X ) can be expressed as a linear mixture of independent sources ( S ) through a mixing matrix ( A ), such that ( X = AS ). The goal is to find a separating matrix ( W ) that approximates the independent sources as ( \hat{S} = WX ). Algorithms like Infomax maximize the mutual information between inputs and outputs, while other approaches minimize Gaussianity through measures of kurtosis or negentropy [33].

Principal Component Analysis employs an orthogonal transformation to convert potentially correlated observed signals into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components. This transformation is defined such that the first principal component accounts for the largest possible variance in the data, with each succeeding component accounting for the highest remaining variance under the constraint of orthogonality to preceding components. PCA can be computed through eigenvalue decomposition of the data covariance matrix or via singular value decomposition (SVD) of the data matrix itself.

Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Artefactual Components

The effective application of ICA and PCA for artifact removal relies on recognizing the distinctive spatial and temporal signatures of motion-related components. Motion artifacts typically exhibit specific spatial patterns including:

- Edge effects with high values at brain boundaries where tissue-air interfaces create susceptibility artifacts [11]

- Ventricle and vascular dominance in components representing cardiac and respiratory pulsations [34]

- Global brain coverage indicative of bulk head movement [30]

Temporal characteristics of artifactual components include:

- High-frequency spikes corresponding to sudden head movements [35]

- Correlation with motion parameters derived from realignment data [32]

- Spectral properties dominated by physiological frequencies (cardiac, respiratory) or their aliased versions [36]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ICA and PCA for Artifact Removal

| Characteristic | Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Separation | Statistical independence | Orthogonal variance |

| Component Statistics | Non-Gaussian, independent | Uncorrelated, Gaussian |

| Spatial Patterns | Can be overlapping or focal | Global, distributed patterns |

| Temporal Structure | Preserves autocorrelation | White noise characteristics |

| Computational Load | Higher | Lower |

| Effect on Signal | Targets specific noise components | Removes dominant variance |

ICA-Based Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

ICA Denoising in Presurgical Planning

The application of ICA denoising in preoperative fMRI for glioma patients demonstrates its clinical utility and methodological robustness. In a comprehensive study involving 35 functional runs across 12 consecutive glioma patients, ICA denoising significantly outperformed standard motion correction approaches [31]. The experimental protocol involved acquiring both motor and language task-based fMRI data on a 3T Siemens Verio scanner with tight head immobilization. Data processing compared four distinct approaches: (1) realignment alone, (2) motion scrubbing, (3) ICA denoising, and (4) combined ICA denoising with motion scrubbing.

The implementation utilized FSL's MELODIC ICA tool followed by manual component classification through visual inspection by an experienced operator [31]. The critical step involved identifying nuisance components based on spatial and temporal characteristics, which were then regressed out using the fsl_regfilt command. Results demonstrated that ICA denoising reduced false-positives in 63% of studies compared to realignment alone, revealed new expected activation areas (previous false-negatives) in 34.4% of cases, and rescued 65% of studies previously deemed nondiagnostic [31]. This approach proved particularly valuable in clinical contexts where accurate localization of eloquent cortex is essential for surgical planning.

Automated ICA Component Classification with ICA-AROMA

The ICA-based Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts (ICA-AROMA) protocol represents a significant advancement in automated component classification. This method uses a robust set of four theoretically motivated features to distinguish motion-related components from neural signals without requiring classifier retraining for different datasets [32]. The algorithm evaluates each independent component based on its high-frequency content, correlation with motion parameters, edge fraction, and CSF fraction.

The experimental workflow for ICA-AROMA implementation involves:

- Standard preprocessing including motion correction, spatial smoothing, and high-pass filtering

- ICA decomposition using standard algorithms (e.g., Infomax ICA)

- Feature extraction for each component based on the four classification criteria

- Component classification using a pre-trained classifier

- Data reconstruction after removing components classified as motion artifacts