Individual-Specific Brain Signatures: Unlocking Stable Neural Fingerprints for Precision Medicine and Drug Development

This article synthesizes current research on individual-specific brain parcellations and their stability, a frontier in neuroscience with profound implications for precision medicine and pharmaceutical development.

Individual-Specific Brain Signatures: Unlocking Stable Neural Fingerprints for Precision Medicine and Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on individual-specific brain parcellations and their stability, a frontier in neuroscience with profound implications for precision medicine and pharmaceutical development. We explore the foundational shift from group-level to individual-specific brain atlases, detailing advanced methodologies like the multi-session hierarchical Bayesian model (MS-HBM) and leverage-score sampling that capture unique, stable neural fingerprints. The review critically examines key challenges in parcellation reliability and optimization, including the impact of different spatial priors and algorithmic choices. Furthermore, we present a comprehensive validation framework assessing parcellation quality through homogeneity, generalizability, and behavioral prediction accuracy. For researchers and drug development professionals, this work provides a crucial roadmap for leveraging stable brain signatures in de-risking clinical trials, enriching patient stratification, and developing tailored neurotherapeutics.

The Paradigm Shift: From Group-Level Atlases to Individual-Specific Brain Signatures

The human brain exhibits substantial individual variability in morphology, connectivity, and functional organization, making the traditional approach of using group-level brain atlases increasingly limited for precision medicine applications [1]. Individual-specific brain parcellation represents a transformative methodology that moves beyond the "one-size-fits-all" atlas approach to map the unique functional and structural organization of each individual's brain. This paradigm shift addresses the fundamental limitation of group-level atlases, which when registered to individual space using morphological information alone, often overlook inter-subject differences in regional positions and topography, failing to capture individual-specific characteristics [1]. The development of individual-specific parcellations has been catalyzed by advances in neuroimaging and machine learning techniques, enabling researchers to delineate personalized brain maps that more accurately reflect each individual's unique neurobiology.

The importance of individual-specific parcellations extends across both basic neuroscience and clinical applications. In research, they provide a powerful tool for understanding variations in brain functions and behaviors, while in clinical settings, they enable more precise identification of brain abnormalities and personalized treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders [1]. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of brain organization necessitates approaches that can capture reconfigurations of brain networks over time, which static parcellations inevitably average over and obscure [2]. This foundational understanding of individual variability and dynamics forms the basis for developing more accurate and biologically meaningful brain maps that can advance both scientific discovery and clinical application.

Methodological Approaches for Individual-Specific Parcellation

Core Methodological Paradigms

The field of individual-specific parcellation has evolved along two primary methodological paradigms: optimization-based and learning-based approaches. Optimization-based methods directly derive individual parcellations based on predefined assumptions such as intra-parcel signal homogeneity, intra-subject parcel homology, and parcel spatial contiguity [1]. These techniques include clustering algorithms, template matching, graph partitioning, matrix decomposition, and gradient-based methods that operate directly on individual-level neuroimaging data to determine optimal parcel boundaries [1]. In contrast, learning-based methods leverage neural networks and deep learning techniques to automatically learn feature representations of parcels from training data and infer individual parcellations using the trained model [1]. These approaches can capture high-order and nonlinear correlations between individual-specific information and parcel boundaries that might be missed by optimization-based techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Individual-Specific Parcellation Methodologies

| Method Category | Key Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization-Based | Region-growing algorithms [1], Clustering methods [3], Template matching [1], Graph partitioning [1] | Directly derived from individual data; No training data required; Interpretable assumptions | May not capture complex nonlinear patterns; Computationally intensive for large datasets |

| Learning-Based | Deep neural networks [1] [4], Bayesian models [4] | Can learn complex feature representations; Potentially better generalization; Faster inference once trained | Require extensive training data; Model interpretability challenges; Potential biases in training data |

Data Modalities for Individual Parcellation

Multiple neuroimaging modalities can drive individual-specific parcellation, each offering unique insights into brain organization:

- Resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI): The most widely used modality for individualization studies, rsfMRI captures spontaneous brain activity that reflects the brain's intrinsic functional organization [1]. The fluctuating signals during rest provide rich information about functional networks that can delineate parcel boundaries.

- Task-based fMRI (tfMRI): Incorporating task activation patterns can constrain parcellation to align with functionally specialized regions [1] [4]. For instance, integrating task fMRI into parcellation models has been shown to significantly reduce functional inhomogeneity within parcels [4].

- Diffusion MRI (dMRI): This modality maps white matter connectivity patterns, providing structural constraints for parcellation that complement functional information [1].

- Structural MRI (sMRI): Morphological features such as cortical thickness and curvature can inform parcellation, particularly when integrated with functional data [1].

Recent advances have demonstrated the superiority of multimodal approaches that combine these data sources to generate more comprehensive and biologically plausible parcellations. For example, the integration of task fMRI constraints has been shown to produce finer parcel boundaries and higher functional homogeneity compared to unimodal approaches [4].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Individual-Specific Parcellation Using Resting-State fMRI

This protocol outlines the standardized procedure for generating individual-specific parcellations using resting-state fMRI data, adapted from established methods in the field [1] [2] [5].

Data Acquisition Parameters

- Imaging Parameters: Acquire T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequences with the following recommended parameters: TR=2.2s, TE=27ms, flip angle=90°, voxel size=4mm³ isotropic, 36 slices [2]. Adjust parameters based on scanner capabilities while minimizing TR.

- Scan Duration: Collect a minimum of 30 minutes of resting-state data across multiple sessions to ensure sufficient signal-to-noise ratio and reliability [2]. Longer acquisitions (e.g., 5 hours total across multiple sessions) significantly improve parcellation quality and reproducibility [2].

- Subject Instructions: Instruct participants to maintain eye fixation on a central crosshair, remain awake, and let their minds wander without engaging in systematic thought.

- Physiological Monitoring: Implement eye-tracking to detect periods of prolonged eye closure indicating potential sleep, and record cardiac and respiratory signals for noise correction [2].

Preprocessing Pipeline

- Initial Steps: Remove initial volumes (typically 5) to allow for magnetic field stabilization [2]. Perform slice timing correction and head motion correction using rigid-body alignment.

- Nuissance Regression: Regress out signals from white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and global signal to reduce non-neural physiological influences [5]. Include 24 motion parameters (6 rigid-body, their derivatives, and squares) as regressors.

- Spatial Normalization: Normalize functional images to standard space (e.g., MNI) using high-resolution T1-weighted structural images and nonlinear registration. Resample to 3×3×3 mm³ voxel size for consistency [5].

- Quality Control: Exclude participants with excessive head motion (>3mm translation or >3° rotation) or poor signal-to-noise ratio. Implement frame-wise displacement thresholding to censor high-motion volumes.

Parcellation Generation

For optimization-based approaches:

- Feature Extraction: Compute similarity matrices between voxels or vertices based on temporal correlation of resting-state time series.

- Clustering: Apply spatial clustering algorithms (e.g., region-growing, k-means, spectral clustering) with spatial constraints to generate parcels.

- Parameter Tuning: Optimize resolution parameters to achieve desired parcel granularity (typically 100-1000 parcels).

For learning-based approaches:

- Model Training: Train deep learning models on reference datasets with extensive individual imaging data.

- Inference: Apply trained models to new individual data to generate personalized parcellations.

- Post-processing: Apply minimal post-processing to ensure spatial continuity of parcels.

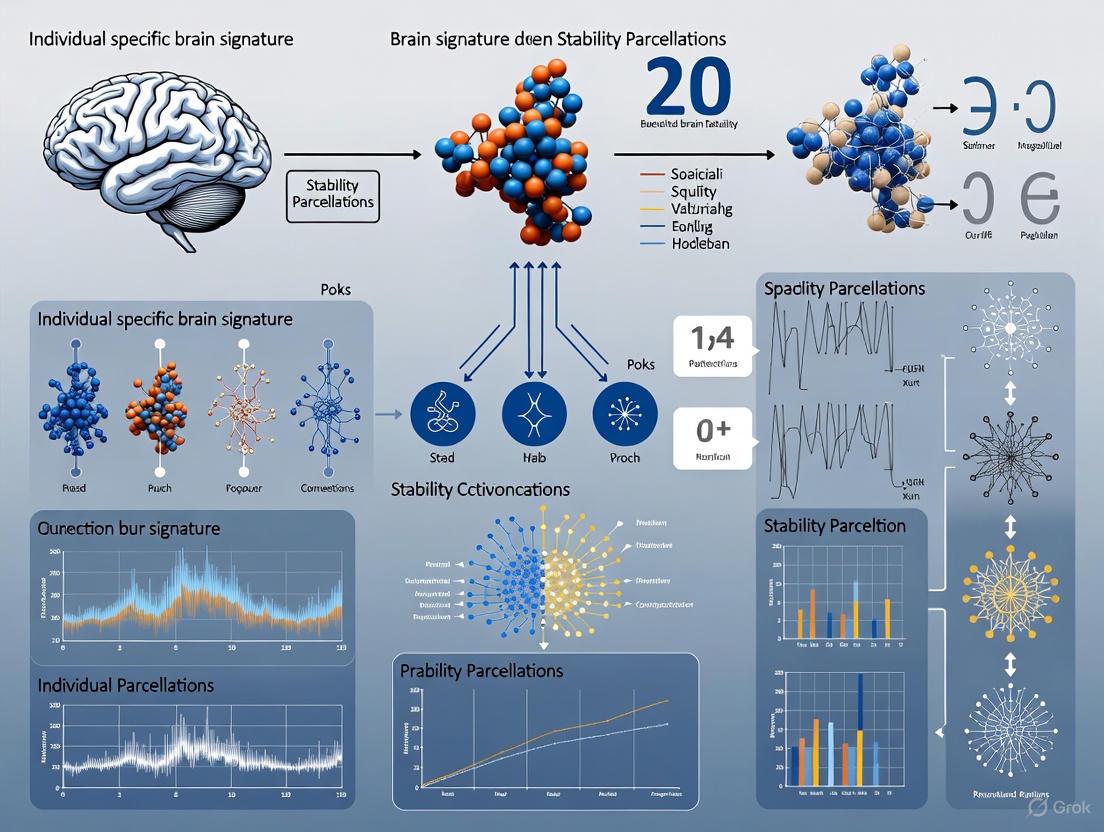

Diagram 1: Workflow for generating individual-specific parcellations from rsfMRI data

Protocol 2: Dynamic State Parcellation Analysis

This protocol addresses the critical limitation of static parcellations by capturing the dynamic reconfigurations of brain networks over time [2].

Dynamic State Identification

- Time Window Selection: Divide continuous resting-state data into short, sliding windows (e.g., 3 minutes duration with 50% overlap) to capture transient network states [2].

- State Clustering: For seed regions of interest, apply cluster analysis to group time windows with highly similar connectivity patterns into discrete "states" [2].

- Stability Mapping: Generate average within-state parcellations (stability maps) by aggregating sliding-window parcellations for each identified dynamic state [2].

Validation of Dynamic States

- Reproducibility Assessment: Split data into independent test and retest sets (e.g., 2.5 hours each) to evaluate spatial reproducibility of dynamic states [2].

- Fingerprinting Analysis: Assess subject specificity by matching state maps generated from the same subjects within a group, with accuracy >70% indicating good individual discriminability [2].

- State Repertoire Characterization: Quantify the richness of dynamic states across different brain regions, with heteromodal cortices typically exhibiting more diverse state repertoires than unimodal regions [2].

Validation and Evaluation Frameworks

Comprehensive Validation Metrics

Robust validation is essential for establishing the reliability and utility of individual-specific parcellations. The field has developed multiple complementary validation approaches:

Table 2: Validation Metrics for Individual-Specific Parcellations

| Validation Dimension | Specific Metrics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-subject Reliability | Test-retest spatial correlation [2], Dice coefficient between sessions | Values >0.9 indicate excellent reproducibility; >0.7 considered acceptable [2] |

| Parcel Quality | Intra-parcel homogeneity [1], Inter-parcel heterogeneity [1], Silhouette coefficient [3] | Higher values indicate more functionally coherent parcels |

| Individual Identification | Fingerprinting accuracy [2] | Ability to match parcellations from the same individual (>70% accuracy indicates good discriminability) [2] |

| Behavioral Relevance | Prediction of cognitive performance [1] [4], Correlation with clinical measures [1] | Higher predictive accuracy indicates greater behavioral relevance |

| Clinical Utility | Agreement with electrocortical stimulation [1], Surgical guidance accuracy [1] | Direct clinical validation for neurosurgical applications |

Benchmarking Against Ground Truth

While definitive ground truth for in vivo human brain parcellation remains challenging to establish, several approaches provide reasonable proxies:

- Task Activation Boundaries: Evaluate alignment between parcel boundaries and transitions in task activation patterns [4] [3]. Parcellations constrained by task fMRI show significantly reduced functional inhomogeneity within parcels [4].

- Myeloarchitecture: Assess correspondence with transitions in cortical myelination patterns from quantitative MRI [3].

- Cytoarchitecture: Compare with histological maps where available, though this requires cross-modal alignment [3].

- Electrical Stimulation Mapping: For neurosurgical applications, validate against functional boundaries identified through direct cortical stimulation [1].

Applications in Neuroscience and Clinical Research

Basic Neuroscience Applications

Individual-specific parcellations have revealed fundamental principles of brain organization that were obscured by group-level approaches:

- Understanding Brain Variability: Individual parcellations have been instrumental in interpreting structural and functional variability of the brain and understanding individual-specific brain characteristics such as age, sex, cognitive behaviors, development and aging, and genetic and environmental factors [1].

- Developmental Trajectories: Fine-grained areal-level individualized parcellations have enabled mapping of developmental trajectories from childhood to adolescence, revealing that higher-order transmodal networks exhibit higher variability in developmental trajectories [4].

- Brain Dynamics: Dynamic parcellation approaches have demonstrated that static functional parcellations incorrectly average well-defined and distinct dynamic states of brain organization, calling for a reconsideration of methods based on static parcellations [2].

Clinical and Translational Applications

The clinical utility of individual-specific parcellations spans multiple domains:

- Neuromodulation Therapy: For repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), subject-specific parcellations enable precise targeting and reveal that functional changes occur differently in network nodes versus boundaries following stimulation [5].

- Neurosurgical Planning: In brain tumor and epilepsy surgery, individual parcellations help identify individual-specific functional boundaries to maximize resection while preserving critical functions [1].

- Biomarker Identification: Individual parcellations play a crucial role in identifying biomarkers for various neurological and psychiatric disorders, offering improved sensitivity for detecting pathological alterations in brain organization [1].

- Aging and Neurodegeneration: Individual-specific neural signatures show stability throughout adulthood while also capturing subtle age-related reorganization, potentially aiding in differentiating normal cognitive decline from neurodegenerative processes [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Resources for Individual-Specific Parcellation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Purpose and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Midnight Scan Club (MSC) [2], Human Connectome Project (HCP) [3], Lifespan HCP [4], Cam-CAN [6] | Provide high-quality, extensive individual imaging data for method development and validation |

| Standardized Atlases | Neuroparc repository [7], AAL atlas [6], Harvard-Oxford Atlas [6], Craddock atlas [6] | Offer standardized reference parcellations for comparison and multi-atlas analysis |

| Software Tools | FSL [7], AFNI [7], FreeSurfer, DPARSF [5], NeuroImaging Analysis Kit [2] | Provide comprehensive preprocessing, analysis, and visualization capabilities |

| Validation Metrics | Dice coefficient [7], Adjusted Mutual Information [7], Intra-parcel homogeneity [1], Fingerprinting accuracy [2] | Quantify different aspects of parcellation quality and reliability |

| Multimodal Data | Task fMRI batteries [4], Diffusion MRI [1], Structural MRI [1], MEG [6] | Enable multimodal parcellation approaches and cross-modal validation |

The field of individual-specific brain parcellation continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions for future development. There is a growing need for integrated platforms that encompass standardized datasets, methodological implementations, and validation frameworks to accelerate progress and improve reproducibility [1]. The development of generalizable learning frameworks that can leverage large-scale datasets while adapting to individual-specific features represents another critical frontier [1]. Additionally, the integration of multimodal and multiscale data, from microstructural features to whole-brain dynamics, promises more biologically comprehensive and clinically useful parcellations [1].

The standardization of parcellation schemes through initiatives like Neuroparc, which consolidates 46 different brain atlases into a single, curated, open-source library with standardized metadata, represents a crucial step toward improving reproducibility and comparability across studies [7]. However, as the field moves toward individual-specific approaches, standardization efforts must evolve to accommodate personalized frameworks while maintaining the ability to compare findings across individuals and studies.

In conclusion, individual-specific parcellation methods represent a fundamental advancement beyond the one-size-fits-all brain atlas approach, offering unprecedented opportunities for understanding individual differences in brain organization and enabling truly personalized clinical applications in neurology and psychiatry. As these methods continue to mature and become more accessible, they hold the potential to transform both basic neuroscience and clinical practice by acknowledging and leveraging the unique organization of each individual brain.

Application Notes: Principles and Quantitative Foundations of Precision Neurodiversity

The paradigm of precision neurodiversity represents a fundamental shift in neuroscience, moving from pathological deficit models to frameworks that view neurological differences as natural, adaptive variations in human brain architecture [8]. This approach is grounded in the discovery that individual-specific brain network signatures, or "neural fingerprints," are stable over time and can reliably predict a wide array of cognitive, behavioral, and sensory phenomena [8]. The following application notes outline the core principles and quantitative foundations for researching and applying this perspective.

Core Principles of Individual-Specific Brain Architecture

- Personalized Brain Networks (PBN): An individual's unique pattern of whole-brain connectivity, characterized at the single-subject level using connectomics methods, constitutes their PBN. This architecture is a more meaningful predictor of cognitive function than group-level diagnostic categories [8].

- Dimensional Frameworks: Dimensional models are replacing categorical diagnoses, as they better capture the continuous nature of cognitive and neural variations. These models are more effective for identifying therapeutic targets across neurodevelopmental conditions [8].

- Stable Neural Fingerprints: High-resolution functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) has enabled the identification of unique brain connectivity patterns that remain stable across tasks and throughout the adult lifespan (ages 18–87), providing age-resilient biomarkers of intrinsic brain organization [8] [9].

Quantitative Signatures of Neurodiverse Conditions

Research utilizing leverage-score feature selection and other advanced computational methods has identified distinct, quantifiable neural signatures associated with various neurodevelopmental trajectories. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Brain Architecture Signatures in Neurodiversity Research

| Condition / Study Focus | Neural Signature | Measurement Approach | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD Subtypes [8] | Delayed Brain Growth (DBG-ADHD) vs. Prenatal Brain Growth (PBG-ADHD) | Structural MRI from >123,000 scans; Normative brain charts | Identification of distinct neurobiological subgroups with significant network-level functional differences not detectable by conventional criteria. |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [10] | Atypical whole-brain network integration | Resting-state fMRI parcellation; between-network connectivity stability | Reduced stability in network connectivity; weaker functional subnetwork differentiation in cerebellum, subcortex, and hippocampus. |

| General Addiction [11] | Increased activity in striatum & supplementary motor area; Decreased activity in anterior cingulate cortex & ventromedial prefrontal cortex | Coordinate-based meta-analysis of ReHo and ALFF/ fALFF from 46 studies | Shared neural activity alterations across substance use and behavioral addictions, mapping onto dopaminergic and other neurotransmitter systems. |

| Age-Resilient Brain Signatures [9] | Stable functional connectivity features across adulthood (18-87 years) | Leverage-score sampling of functional connectomes across multiple brain parcellations (AAL, HOA, Craddock) | A small subset of connectivity features captures individual-specific patterns, with ~50% overlap between consecutive age groups. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Identifying Individual-Specific Brain Signatures Using Leverage-Score Sampling

Objective: To extract a stable, individual-specific neural signature from functional connectome data that is resilient to age-related changes [9].

Materials:

- High-quality T2*-weighted blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) images acquired via fMRI.

- Computational infrastructure (e.g., the AFNI software package, Freesurfer, Cam-CAN data processing pipeline).

- Predefined brain atlases for parcellation (e.g., AAL (116 regions), Harvard Oxford (HOA, 115 regions), Craddock (840 regions)).

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Acquire resting-state or task-based fMRI data. Preprocess using a standard pipeline including realignment, co-registration to a T1-weighted anatomical image, spatial normalization, and smoothing [9].

- Parcellation and Connectome Construction: For each subject, parcellate the preprocessed fMRI time-series data (

T ∈ ℝv × t) for a chosen atlas to create a region-wise time-series matrix (R ∈ ℝr × t). Compute the Pearson Correlation matrix (C ∈ [-1, 1]r × r) to generate the Functional Connectome (FC) [9]. - Data Structuring for Group Analysis: Vectorize each subject's FC matrix by extracting its upper triangular part. Stack these vectors to form a population-level matrix

Mof dimensions[m × n], wheremis the number of FC features andnis the number of subjects [9]. - Leverage Score Calculation: For the matrix

M, compute an orthonormal basisUspanning its columns. The statistical leverage score for thei-th row (feature) is calculated asl_i = ||U_i||², whereU_iis thei-th row ofU[9]. - Feature Selection: Sort all leverage scores in descending order. Retain the top

kfeatures with the highest scores. These features represent the most influential connections for capturing individual-specific signatures within the population [9]. - Validation: Validate signature stability by assessing the overlap of top features across different age cohorts and different brain parcellation schemes [9].

Protocol for Functional Parcellation of the Neurodiverse Brain

Objective: To generate a whole-brain map of functional networks specific to a neurodiverse population (e.g., ASD) and compare it with a typically developing (TD) map [10].

Materials:

- 3T MRI scanner with optimized imaging sequences (e.g., GE Signa HDxt 3.0 T).

- 8-channel receive-only head coil.

- Software for preprocessing (e.g., AFNI) and parcellation.

Procedure:

- Participant Selection & Matching: Recruit neurodiverse (e.g., ASD) and TD control groups. Tightly match groups on critical variables including temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR), in-scanner motion (e.g., mean Framewise Displacement < 0.2 mm/TR), age, and full-scale IQ [10].

- fMRI Data Acquisition: Acquire high-quality resting-state fMRI data. Example parameters: TR = 3500 ms, TE = 27 ms, flip angle = 90°, 42 slices, 1.7 × 1.7 × 3.0 mm voxel size, 140 volumes over ~8 minutes. Acquire a high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image for registration [10].

- Data Preprocessing & Denoising: Preprocess data to remove artifacts. Steps include discarding initial TRs, despiking, slice-time correction, motion realignment, and spatial blurring. Denoise using a method like ANATICOR, regressing out nuisance signals from head motion, white matter, ventricles, cardiac, and respiratory cycles [10].

- Parcellation Generation: Use a robust parcellation routine that incorporates internal consistency. This involves iteratively performing clustering on random halves of the data and retaining only network distinctions that are reproducible across iterations [10].

- Comparison & Analysis: Compare the resulting neurodiverse and TD parcellation maps on key metrics:

- Network Stability: Assess the consistency of whole-brain connectivity patterns within identified functional networks.

- Subnetwork Differentiation: Evaluate the distinctness of functional subnetworks in regions like the cerebellum and subcortex.

- Cortico-Subcortical Integration: Analyze the strength of functional connectivity between subcortical structures (e.g., hippocampus) and the neocortex [10].

Functional Parcellation Workflow for Neurodiverse Brains

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Brain Signature Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Tools / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Population Neuroimaging Datasets | Provide large-scale, high-quality data for normative modeling and subgroup discovery. | UK Biobank [8], Cambridge Center for Aging and Neuroscience (Cam-CAN) [9], Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) [10] |

| Brain Atlases (Parcellations) | Provide a standardized set of brain regions (nodes) for network analysis. Choice of atlas impacts functional interpretation. | Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL), Harvard Oxford Atlas (HOA), Craddock Atlas [9] |

| Gene Expression Atlas | Enables spatial correlation between neural findings and molecular systems (e.g., receptor distributions). | Allen Human Brain Atlas [12] [11] |

| Analysis & Preprocessing Software | Data cleaning, normalization, denoising, and statistical analysis of neuroimaging data. | AFNI [10], Freesurfer [12] [10], SPM12 [9] |

| Computational Modeling Algorithms | Identify individual-specific signatures, generate virtual brain models, and perform subgroup analyses. | Leverage-score feature selection [9], Conditional Variational Autoencoders (for connectome generation) [8], Multi-level mixed models [12] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Correlates

Meta-analyses of resting-state brain activity have identified consistent alterations in specific brain regions across addictive disorders. These neural patterns recapitulate the spatial distribution of key neurotransmitter systems, providing a molecular correlate for the observed functional signatures [11].

Neural Activity Patterns and Molecular Systems

The increasing prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases in an aging global population underscores the critical need for reliable biomarkers that can accurately distinguish normal aging from pathological neurodegeneration [9]. This challenge, termed the "Stability Conundrum," refers to the fundamental difficulty in identifying neural features that remain stable throughout the adult lifespan while capturing individual-specific brain architecture. Individual-specific brain signature stability parcellations represent a transformative approach in neuroscience, aiming to establish a baseline of neural features that are relatively unaffected by the aging process [9]. Such biomarkers hold tremendous potential for predicting functional outcomes, enhancing our understanding of age-related brain changes, and ultimately aiding in the development of targeted therapeutic interventions for neurodegenerative conditions [13]. The identification of age-resilient neural fingerprints provides a crucial reference point against which disease-related deviations can be measured, offering unprecedented opportunities for early detection and intervention in age-related cognitive decline.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Defining Neural Fingerprints in Aging Research

The concept of "neural fingerprints" or "brain signatures" refers to unique, individual-specific patterns of brain organization that can be reliably identified through neuroimaging techniques. In the context of aging research, two complementary approaches have emerged: age-resilient signatures that remain stable across the lifespan, and predictive aging trajectories that capture patterns of change [9] [13]. The relationship between chronological age, biological brain age, and resilience can be conceptualized through several key constructs detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Concepts in Brain Aging and Neural Signature Research

| Concept | Definition | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Chronological Age | The amount of time elapsed from birth | Standard reference metric for age measurement [13] |

| Biological Brain Age | Assessment of brain age based on physiological state determined through neuroimaging | Reflects accumulated cellular damage and aging processes [13] |

| Predicted Age Difference (PAD) | Discrepancy between predicted brain age and chronological age | Indicator of deviation from healthy aging trajectory; linked to cognitive impairment risk [13] |

| Age-Resilient Signatures | Neural features relatively stable across aging process | Baseline for distinguishing normal aging from pathological neurodegeneration [9] |

| Individual Aging Trajectory | Personalized approach to explain variations in aging between individuals | Enables tailored strategies for promoting healthy aging based on unique characteristics [13] |

| Cognitive Frailty | Simultaneous presence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment without definite dementia diagnosis | Identifies intermediate, potentially reversible stage between normal and accelerated aging [13] |

Neurobiological Basis of Signature Stability

The stability of individual-specific neural signatures appears to be supported by distinct but overlapping functional connectivity patterns that exhibit varying degrees of resilience to aging effects [9]. Research by Jiang et al. (2022) revealed that while cognitive decline and aging affect all network connections, specific networks, such as the dorsal attention network, show unique relationships with cognitive performance independent of age [9]. This insight is crucial for differentiating between cognitive decline due to normal aging and neurodegenerative processes. Furthermore, individual-specific parcellation topography has been demonstrated to be behaviorally relevant, motivating significant interest in estimating individual-specific parcellations that capture both inter-subject and intra-subject variability [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Leverage-Score Sampling for Signature Identification

The identification of age-resilient neural signatures requires sophisticated analytical approaches capable of handling high-dimensional neuroimaging data. The leverage-score sampling methodology has emerged as a powerful technique for this purpose [9]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing this approach:

Protocol 1: Leverage-Score Sampling for Age-Resilient Feature Selection

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Utilize preprocessed functional MRI data that has undergone artifact and noise removal, realignment, co-registration, spatial normalization, and smoothing [9].

- Parcellate the cleaned fMRI time-series matrix T ∈ ℝv × t (where v and t denote the number of voxels and time points) into region-wise time-series matrices R ∈ ℝr × t for chosen brain atlases (r represents the number of regions) [9].

- Compute Pearson Correlation matrices C ∈ [−1, 1]r × r to create Functional Connectomes (FCs), where each entry represents correlation strength between brain regions.

- Vectorize each subject's FC matrix by extracting its upper triangle and stack these vectors to form population-level matrices for each task (e.g., Mrest, Msmt, Mmovie) [9].

Feature Selection via Leverage Scores

- For cohort-specific matrices of shape [m × n] (where m is the number of FC features and n is the number of subjects), compute leverage scores to identify high-influence FC features.

- Let U denote an orthonormal matrix spanning the columns of data matrix M. The leverage scores for the i-th row of M are defined as: li = ||Ui||², where Ui represents the i-th row of U [9].

- Sort the leverage scores in descending order and retain only the top k features, which represent the most informative individual-specific signatures [9].

- Map these selected features (edges of functional connectomes) back to their corresponding brain regions for anatomical interpretation.

Validation and Cross-Testing

- Validate the consistency of identified features across diverse age cohorts (e.g., 18-87 years) and multiple brain parcellations (e.g., Craddock, AAL, HOA) [9].

- Assess stability by examining the overlap of features between consecutive age groups and across different anatomical parcellations.

- Evaluate generalizability to out-of-sample resting-state fMRI and task-fMRI data from the same individuals [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

Figure 1: Workflow for Identifying Age-Resilient Neural Signatures Using Leverage-Score Sampling

Multi-Session Hierarchical Bayesian Model (MS-HBM) for Individual-Specific Parcellations

For estimating high-quality individual-specific parcellations that account for both inter-subject and intra-subject variability, the Multi-Session Hierarchical Bayesian Model (MS-HBM) has demonstrated superior performance [14]. The following protocol describes the implementation of this approach:

Protocol 2: MS-HBM for Individual-Specific Areal-Level Parcellations

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire multi-session resting-state fMRI data using appropriate parameters (e.g., 2mm isotropic resolution, TR=0.72s for HCP-style protocols) [14].

- Preprocess structural and functional data including surface-based registration to standard space (e.g., fs_LR32k surface) [14].

- For HCP data, apply the HCP minimal preprocessing pipeline including distortion correction, motion correction, and surface registration [14].

Model Estimation and Variants

- Extend the network-level MS-HBM to estimate individual-specific areal-level parcellations with spatial localization priors [14].

- Implement three distinct MS-HBM variants to account for lack of consensus on spatial contiguity:

- Contiguous MS-HBM (cMS-HBM): Enforces strict spatial contiguity

- Distributed MS-HBM (dMS-HBM): Allows spatially localized parcels with multiple disconnected components

- Gradient-Infused MS-HBM (gMS-HBM): Incorporates gradient information [14]

- Estimate model parameters using variational Bayesian inference, distinguishing between inter-subject and intra-subject functional connectivity variability.

Validation and Generalization Testing

- Evaluate intra-subject reproducibility and inter-subject similarity across multiple datasets (e.g., HCP and MSC datasets) [14].

- Test generalizability to out-of-sample rs-fMRI and task-fMRI data from the same participants.

- Assess behavioral prediction performance using resting-state functional connectivity derived from MS-HBM parcellations compared to alternative approaches [14].

Data Analysis and Quantitative Findings

Key Findings on Signature Stability and Aging Trajectories

Research on age-resilient neural signatures has yielded several crucial quantitative findings that advance our understanding of brain aging. The application of leverage-score sampling to functional connectome data has revealed that a small subset of features consistently captures individual-specific patterns, with significant overlap (~50%) between consecutive age groups and across different brain atlases [9]. This stability of neural signatures throughout adulthood and their consistency across various anatomical parcellations provides new perspectives on brain aging, highlighting both the preservation of individual brain architecture and subtle age-related reorganization [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Findings on Age-Resilient Neural Signatures and Predictive Aging

| Finding | Measurement Approach | Result | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Stability Across Age | Overlap of top leverage score features between consecutive age groups | ~50% overlap [9] | Demonstrates substantial core of stable individual-specific neural features across lifespan |

| Cross-Atlas Consistency | Feature consistency across Craddock, AAL, and HOA brain atlases | Significant consistency [9] | Supports robustness of identified signatures beyond specific parcellation choices |

| MS-HBM Generalization Performance | Generalization to out-of-sample rs-fMRI and task-fMRI | Individual-specific MS-HBM parcellations using 10min of data generalized better than other approaches using 150min of data [14] | Enables efficient individual-specific parcellation with limited data |

| Behavioral Prediction Improvement | Behavioral prediction performance from resting-state functional connectivity | RSFC from MS-HBM parcellations achieved best behavioral prediction performance [14] | Individual-specific features capture behaviorally meaningful information beyond group-level parcellations |

| Spatial Contiguity Effects | Resting-state homogeneity and task activation uniformity | Strictly contiguous MS-HBM exhibited best resting-state homogeneity and most uniform within-parcel task activation [14] | Informs appropriate spatial constraints for different research applications |

In studies examining predictive brain aging, the Predicted Age Difference (PAD) has emerged as a crucial metric, with research demonstrating that a larger PAD indicates higher risk of age-related diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions [13]. Furthermore, individual-specific parcellation approaches like MS-HBM have shown that resting-state functional connectivity derived from these parcellations achieves the best behavioral prediction performance compared to alternative approaches, highlighting the behavioral relevance of individual-specific features [14].

Comparative Analysis of Parcellation Approaches

Research has demonstrated substantial differences in performance between various parcellation approaches. Individual-specific MS-HBM parcellations estimated using only 10 minutes of data generalized better to out-of-sample data than other approaches using 150 minutes of data from the same individuals [14]. Among MS-HBM variants, the strictly contiguous MS-HBM exhibited the best resting-state homogeneity and most uniform within-parcel task activation, while the gradient-infused MS-HBM showed numerically better (though not statistically significant) behavioral prediction performance [14]. These findings suggest that different variants may be optimal for different research applications, with cMS-HBM preferable for localization studies and gMS-HBM for behavioral prediction.

Application Notes for Research and Drug Development

Implementation of neural signature stability research requires specific computational tools and data resources. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit for investigating age-resilient neural fingerprints.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Signature Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type/Format | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CamCAN Dataset | Population-scale neuroimaging dataset | Provides diverse age cohort (18-88 years) for cross-sectional aging studies [9] | Validation of age-resilient signatures across adult lifespan |

| HCP S1200 Release | Large-scale neuroimaging dataset (n=1094) | Enables individual-specific parcellation estimation and validation in young adults [14] | Training models for individual-specific parcellations |

| MS-HBM Software | GitHub repository (CBIG) | Estimates individual-specific areal-level parcellations accounting for inter- and intra-subject variability [14] | Creating individual-specific brain parcellations from resting-state fMRI |

| Leverage-Score Sampling Algorithm | Custom computational algorithm | Identifies most informative features for individual differentiation from high-dimensional connectome data [9] | Feature selection for stable neural signature identification |

| Craddock, AAL, HOA Atlases | Brain parcellation templates | Provide anatomical frameworks for consistent region definition across studies [9] | Standardized brain partitioning for cross-study comparisons |

| Between-Subject Whole-Brain Machine Learning | Multivariate analysis approach | Identifies distributed neural signatures predictive of cognitive states across individuals [15] | Cross-task prediction of attention states and cognitive processes |

Implementation in Clinical Trials and Drug Development

The application of age-resilient neural signatures in pharmaceutical research offers promising approaches for subject stratification, treatment response monitoring, and novel endpoint development:

Subject Stratification: Individual-specific neural signatures and predicted age difference metrics can identify homogeneous patient subgroups for targeted interventions, potentially reducing clinical trial variability and enhancing sensitivity to detect treatment effects [13].

Treatment Response Monitoring: Changes in individual aging trajectories in response to therapeutic interventions can serve as sensitive markers of treatment efficacy, potentially detecting beneficial effects before clinical manifestation [13].

Novel Endpoint Development: The stability metrics of neural signatures over time may provide quantitative endpoints for assessing interventions aimed at promoting brain health and resilience in neurodegenerative conditions [9].

Target Identification: Genes associated with accelerated and delayed aging trajectories (e.g., APOE4, DNM1, SYN1, mTOR) represent promising targets for therapeutic development aimed at modifying brain aging processes [13].

Visualizing Brain Aging Trajectories and Signature Stability

The relationship between chronological aging, individual variability, and neural signature stability can be visualized through the following conceptual diagram:

Figure 2: Brain Aging Trajectories and Signature Stability Concepts

This visualization illustrates how a core set of stable neural signatures persists across different aging trajectories, providing a reference framework for identifying pathological deviations. The diagram shows three potential aging pathways (normal, accelerated, and resilient) all sharing a common core of stable neural features while exhibiting distinct patterns of change in other neural characteristics.

The identification of age-resilient neural fingerprints represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience research, providing a stable reference framework against which individual variations in brain aging can be measured. The methodologies outlined in this document—particularly leverage-score sampling for feature selection and hierarchical Bayesian models for individual-specific parcellation—provide robust approaches for capturing these stable neural signatures. The consistency of these signatures across diverse age cohorts and multiple brain atlases underscores their potential as reliable biomarkers for distinguishing normal aging from pathological neurodegeneration [9]. As research in this field advances, the integration of individual-specific parcellations with genetic, molecular, and behavioral data will further enhance our understanding of brain aging mechanisms and accelerate the development of targeted interventions for age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases.

Inter-Subject vs. Intra-Subject Variability in Functional Connectivity

Conceptual Foundation and Neurobiological Significance

In the pursuit of individual-specific brain signature stability parcellations, the precise characterization of inter-subject variability (differences between individuals) and intra-subject variability (differences within the same individual across time or sessions) is paramount. These two dimensions of variability are not merely noise, but represent fundamental characteristics of brain organization with direct implications for personalized biomarkers and drug development [16] [17].

Inter-subject variability reflects stable, trait-like differences in functional brain organization that uniquely identify individuals. Research demonstrates that functional connectivity (FC) profiles can serve as a "fingerprint" that identifies individuals from a large group with high accuracy (up to 93% between resting-state scans) [16]. This individual uniqueness is behaviorally relevant, with recent studies showing that individual-specific parcellation topography correlates with behavioral measures and may provide superior behavioral prediction compared to group-level parcellations [14].

Intra-subject variability encompasses changes within an individual across different scanning sessions, which may arise from technical factors, dynamic brain states, mood, arousal, or cognitive changes [16]. The sensory-motor cortex exemplifies this dissociation, exhibiting low inter-subject variability but high intra-subject variability [14]. Understanding this balance is crucial for differentiating state versus trait effects in pharmacotherapy studies.

The variability signal-to-noise ratio (vSNR) quantifies the usefulness of functional mapping technologies for individual differences research, defined as the ratio of inter-subject to intra-subject variability [18]. This metric is particularly valuable for assessing whether a functional mapping technique captures meaningful individual differences beyond measurement noise.

Quantitative Patterns and Spatial Distribution

The spatial distribution of inter-subject and intra-subject variability across the brain follows a consistent hierarchical pattern that reflects functional specialization.

Table 1: Regional Patterns of Functional Connectivity Variability

| Brain Region/Network | Inter-Subject Variability | Intra-Subject Variability | Functional Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontoparietal Control Network | High [17] [19] | Moderate-High [14] | Higher-order cognitive functions |

| Default Mode Network | High [17] [19] | Moderate-High [14] | Self-referential thought, mind-wandering |

| Salience Network | High [19] | Moderate | Stimulus detection, attention |

| Sensorimotor Networks | Low [17] [19] | High [14] | Basic sensory and motor processing |

| Visual Networks | Low [17] | Moderate | Visual perception |

This heterogeneous distribution is not random but follows a systematic gradient from unimodal to heteromodal regions. Higher-order associative networks (frontoparietal, default mode) exhibit greater inter-subject variability, suggesting these regions may support more individualized functional specialization [17]. In contrast, primary sensorimotor regions show lower inter-subject variability but can display higher intra-subject variability, reflecting their state-dependent processing characteristics [14].

In the context of major depression, individual differences in functional connectivity account for approximately 45% of the explained variance, while common connectivity shared across all individuals accounts for about 50%, and group differences related to diagnosis represent only a small fraction (0.3-1.2%) [19]. This striking finding underscores the critical importance of accounting for individual differences in clinical neuroscience and drug development.

Experimental Protocols for Variability Assessment

Protocol 1: Variability Signal-to-Noise Ratio (vSNR) Calculation

Purpose: To quantify the reliability of functional mapping technologies for individual differences research by comparing inter-subject and intra-subject variability [18].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Collect multiple resting-state fMRI sessions (minimum 2, ideally 4-5) for each subject in the cohort over a defined period (e.g., weeks to months).

- Parcellation Generation: For each subject and each fMRI session, generate a functional parcellation map using a chosen algorithm (e.g., MS-HBM).

- Intra-subject Variability Calculation:

- Apply binary matching between all possible pairs of scans from the same subject (for 5 scans: 10 combinations).

- Calculate variability at each cortical vertex by counting the fraction of cluster labels that do not match across comparisons.

- Average the variability maps across all within-subject comparisons.

- Inter-subject Variability Calculation:

- Randomly select one session each from multiple different subjects.

- Quantify variability similarly by counting non-identical cluster labels across subjects.

- Repeat this permutation multiple times and average the resulting variability maps.

- vSNR Computation: Calculate the variability signal-to-noise ratio using the formula:

vSNR = Inter-subject Variability / Intra-subject Variability [18]

Higher vSNR values indicate the functional mapping technique better captures true individual differences relative to measurement noise.

Protocol 2: Multi-Session Hierarchical Bayesian Model (MS-HBM) for Individual-Specific Parcellations

Purpose: To estimate high-quality individual-specific areal-level parcellations that account for both inter-subject and intra-subject variability [14].

Procedure:

- Data Requirements: Acquire multi-session resting-state fMRI data (minimum 10 minutes per session, multiple sessions preferred).

- Model Initialization: Initialize with a group-level parcellation as a prior (e.g., Yeo-17 network parcellation).

- Variability Modeling:

- Implement the hierarchical Bayesian framework to separately model inter-subject and intra-subject functional connectivity variability.

- Incorporate spatial constraints based on the desired parcel characteristics (strictly contiguous vs. allowing disconnected components).

- Parameter Estimation: Use variational Bayesian inference to estimate individual-specific parcellations that maximize the posterior probability given the observed fMRI data.

- Validation: Assess parcellation quality using:

- Resting-state homogeneity (higher indicates better functional coherence)

- Task activation uniformity (higher indicates better functional specificity)

- Generalization to out-of-sample resting-state and task-fMRI data

The MS-HBM approach has demonstrated that individual-specific parcellations estimated using just 10 minutes of data can generalize better than other approaches using 150 minutes of data, highlighting its efficiency for capturing meaningful individual differences [14].

Protocol 3: Functional Connectivity Fingerprinting

Purpose: To assess the stability and uniqueness of individual functional connectivity profiles across different cognitive states [16].

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Acquire fMRI data during multiple task conditions (e.g., working memory, emotion processing, motor tasks) and resting-state across separate sessions.

- Connectivity Matrix Construction: For each subject and session, compute whole-brain functional connectivity matrices using a predefined atlas (e.g., 268-node functional atlas).

- Identification Analysis:

- Select one session as the "target" and another as the "database" (always from different days to minimize session-specific confounds).

- For each target matrix, compare it with all database matrices using Pearson correlation of edge values.

- Assign the identity as the database subject with the highest correlation coefficient.

- Accuracy Calculation: Compute identification accuracy as the proportion of correctly matched identities across all subjects.

- Cross-State Analysis: Repeat the identification procedure for all pairs of cognitive states (rest-rest, rest-task, task-task) to assess the stability of individual fingerprints across different brain states.

This protocol typically yields high identification accuracy between resting-state scans (∼93%) with lower but significant accuracy across task states (54-87%), demonstrating both the stability and state-modulation of individual connectivity patterns [16].

Visualization of Methodological Frameworks

Diagram 1: Experimental Framework for Variability Assessment (Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: vSNR Calculation Methodology (Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Session Hierarchical Bayesian Model (MS-HBM) | Computational Model | Estimates individual-specific parcellations accounting for both inter- and intra-subject variability [14] | Individual-specific areal-level parcellation; Behavioral prediction |

| Variability Signal-to-Noise Ratio (vSNR) | Analytical Metric | Quantifies reliability of functional mapping for individual differences research [18] | Protocol optimization; Measurement validation |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data | Reference Dataset | Provides high-quality multi-modal neuroimaging data for model development and validation [14] [16] | Method benchmarking; Normative comparisons |

| 268-Node Functional Atlas | Parcellation Template | Standardized whole-brain partitioning for connectivity matrix construction [16] | Functional connectivity fingerprinting; Cross-study comparisons |

| Morel Histological Atlas | Anatomical Reference | Provides prior guidance for thalamic parcellation in iterative frameworks [20] | Subcortical parcellation; Structure-function validation |

| Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) | Transcriptomic Database | Enables correlation of functional variability with gene expression patterns [17] | Multimodal integration; Molecular mechanisms of variability |

Implications for Drug Development and Personalized Medicine

The distinction between inter-subject and intra-subject variability has profound implications for pharmaceutical research and development. In major depression studies, individual differences account for approximately 45% of functional connectivity variance, while diagnosis-related group differences represent only 0.3-1.2% of explained variance [19]. This suggests that targeting patient subgroups based on individual connectivity profiles may be more productive than focusing on broad diagnostic categories.

Connectome stability emerges as a particularly promising biomarker for therapeutic monitoring. Individuals with more stable task-based functional connectivity patterns perform better on attention and working memory tasks [21]. Pharmacotherapies that enhance connectome stability may therefore improve cognitive outcomes in neuropsychiatric disorders. Furthermore, the high vSNR of individual-specific parcellations enables more sensitive measurement of treatment effects in clinical trials by reducing measurement noise [14] [18].

The frontoparietal control and default mode networks, which show high inter-subject variability [17] [19], may represent optimal targets for personalized interventions. These networks are rich in synapse-related genes and glutamatergic pathways [17], suggesting potential molecular targets for drugs aimed at modulating individual-specific network dynamics. By accounting for both inter-subject and intra-subject variability in functional connectivity, researchers can develop more effective, personalized therapeutic strategies with improved clinical outcomes.

Brain parcellation—the process of dividing the brain into distinct functional regions—is a fundamental step in analyzing neuroimaging data. However, the quest for a single "ground truth" parcellation is fundamentally misguided, as the optimal partitioning of brain tissue depends critically on the specific scientific or clinical question being investigated [22]. The teleological approach to brain parcellation recognizes this inherent context-dependency, arguing that parcellations should be evaluated based on their effectiveness for particular applications rather than against some idealized universal standard [22]. This perspective is particularly relevant for research on individual-specific brain signatures, where understanding the stability and uniqueness of neural architecture is paramount for both basic neuroscience and drug development [1] [6].

The limitations of a one-size-fits-all approach become evident when considering that different parcellation schemes can produce meaningfully different results when examining individual differences in functional connectivity [23]. For instance, the association between functional connectivity and factors such as age, environmental experience, and cognitive ability can vary significantly based on parcellation choice, directly impacting scientific interpretation [23]. Furthermore, static group-level parcellations may incorrectly average well-defined and distinct dynamic states of brain organization, potentially obscuring functionally relevant information [24]. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting and validating brain parcellations based on research objectives, with particular emphasis on studies investigating the stability of individual-specific brain signatures across the lifespan and in clinical contexts.

Evaluation Frameworks: Matching Metrics to Applications

Taxonomy of Evaluation Criteria

A teleological approach requires application-specific evaluation criteria. The table below summarizes key validation metrics and their relevance to different research contexts.

Table 1: Evaluation Metrics for Brain Parcellation Schemes

| Evaluation Metric | Description | Relevant Research Context | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-Parcel Homogeneity [22] | Measures similarity of time series or connectivity profiles of voxels within the same parcel. | General purpose; fundamental data fidelity assessment. | Higher values indicate more functionally coherent parcels; can be quantified with Pearson correlation. |

| Inter-Parcel Separation [22] | Assesses dissimilarity between voxels in different parcels compared to those within the same parcel. | Network differentiation studies; functional segregation analysis. | Sharp transitions indicate clear functional boundaries between networks. |

| Test-Retest Reliability [24] [1] | Quantifies reproducibility of parcellations across different scanning sessions for the same individual. | Individual-specific signature identification; longitudinal studies. | Spatial correlation >0.9 indicates high reproducibility for dynamic state parcellations [24]. |

| Fingerprinting Accuracy [24] [6] | Ability to correctly identify individuals from their functional connectivity patterns across sessions. | Precision medicine; biomarker development. | Accuracy >70% demonstrates high subject specificity [24]. |

| Task-Activation Alignment [22] [25] | Measures how well parcel boundaries align with task-evoked fMRI activation patterns. | Task-based fMRI studies; cognitive neuroscience. | Strong alignment increases functional validity for task-based investigations. |

| Cross-Parcellation Consistency [23] [6] | Examines stability of findings across different parcellation schemes. | Validation of individual differences; robust biomarker identification. | ~50% feature overlap across atlases suggests stable individual signatures [6]. |

Application-Specific Validation Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Parcellations for Individual Difference Studies

Application Context: Investigating how functional connectivity correlates with age, cognitive ability, clinical status, or treatment response.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Acquire resting-state fMRI data from a well-characterized cohort with appropriate phenotypic measures. Preprocess using standardized pipelines (e.g., SPM12, FSL, AFNI) with motion correction [6].

- Parcellation Application: Extract time series from multiple parcellation schemes (minimum of 3 recommended), including at least one fine-grained (≥200 parcels) and one coarse-grained (≤100 parcels) atlas [23] [6].

- Connectivity Calculation: Compute functional connectomes using Pearson correlation between regional time series [6].

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct association analyses between connectivity features and variables of interest separately for each parcellation.

- Consistency Assessment: Compare effect sizes and statistical significance across parcellation schemes. Report the percentage of findings robust across multiple parcellations.

Interpretation: Findings that are consistent across parcellation schemes are more reliable and generalizable. Significant discrepancies indicate parcellation-sensitive effects that require careful interpretation [23].

Protocol 2: Establishing Individual-Specific Signature Stability

Application Context: Identifying neural fingerprints that remain stable within individuals across time or cognitive states.

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Acquire multiple fMRI scans per individual (resting-state and/or task-based) from datasets like Cam-CAN or HCP [6] [25].

- Feature Selection: Apply leverage score sampling or similar dimensionality reduction techniques to identify high-influence functional connectivity features [6].

- Stability Calculation: Compute intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) for feature stability within individuals across sessions.

- Cross-Atlas Validation: Repeat analysis across multiple anatomical and functional parcellations (e.g., AAL, HOA, Craddock) [6].

- Discriminability Testing: Use machine learning classifiers to test whether connectivity patterns can accurately identify individuals across sessions.

Interpretation: Features demonstrating high ICC (>0.7) and high discriminative accuracy (>90%) across multiple parcellations represent robust individual-specific signatures [6].

Methodological Approaches: From Group-Level to Individual-Specific Parcellations

Classification of Parcellation Methods

Individual brain parcellation methods can be broadly categorized into optimization-based and learning-based approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Table 2: Methodological Approaches to Individual Brain Parcellation

| Method Category | Key Principles | Representative Algorithms | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization-Based [1] | Directly derives parcels based on predefined assumptions (e.g., homogeneity, spatial contiguity) applied to individual data. | Region-growing [1], clustering (K-means, hierarchical) [25], graph partitioning [1]. | No training data required; conceptually transparent; flexible to individual patterns. | Computationally intensive; may not capture high-order nonlinear patterns. |

| Learning-Based [1] | Uses trained models to infer individual parcellations, learning feature representations from data. | Deep learning models [1], convolutional neural networks [1]. | Captures complex patterns; fast application once trained; can integrate multimodal data. | Requires large training datasets; model generalizability concerns. |

| Two-Level Groupwise [25] | Applies clustering algorithms to subject-level parcellations or group-average connectivity matrices. | Ward-2, K-Means-2, N-Cuts-2 [25]. | Balances individual and group features; improves group-level consistency. | May obscure individual-specific features. |

Workflow for Individual-Specific Parcellation

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for generating and validating individual-specific parcellations, integrating both optimization-based and learning-based approaches:

Individual Brain Parcellation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Brain Parcellation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools / Datasets | Function and Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | FreeSurfer, BrainSuite, BrainVISA [26] | Automated cortical parcellation and morphometric analysis. | Freely available; extensive documentation. |

| Parcellation Algorithms | Ward's clustering, K-means, Normalized Cuts [25] | Data-driven parcellation using different clustering approaches. | Implementations in scikit-learn, in-house tools [25]. |

| Reference Atlases | Desikan-Killiany, Destrieux, AAL, HOA, Craddock [6] [25] | Anatomical and functional reference parcellations for comparison. | Publicly available; often included in software packages. |

| Validation Tools | Homogeneity/separation metrics, fingerprinting algorithms [22] | Quantitative evaluation of parcellation quality. | Custom implementations; growing standardization. |

| Datasets | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [25], Cam-CAN [6] | High-quality neuroimaging data for method development and testing. | Publicly available with data use agreements. |

Advanced Applications: From Basic Research to Clinical Translation

Clinical and Research Applications Diagram

Research and Clinical Applications

Clinical Translation Protocols

Protocol 3: Parcellation for Biomarker Discovery in Clinical Trials

Application Context: Identifying connectivity-based biomarkers for patient stratification, treatment target engagement, or treatment response prediction in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Procedure:

- Cohort Selection: Recruit well-phenotyped patient and control groups with sufficient sample size for biomarker discovery.

- Individualized Parcellation: Generate individual-specific parcellations using optimization- or learning-based methods [1].

- Feature Extraction: Compute connectivity matrices and extract features with high discriminant potential between groups.

- Cross-Site Validation: Test biomarker generalizability across different scanners and acquisition protocols.

- Clinical Correlation: Associate connectivity features with clinical measures and treatment outcomes.

Interpretation: Individualized parcellations may reveal patient-specific network alterations that group-level atlases miss, potentially offering more precise biomarkers [1].

Protocol 4: Parcellation for Neuromodulation Treatment Planning

Application Context: Optimizing target identification for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or deep brain stimulation (DBS).

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment: Acquire high-resolution resting-state fMRI before intervention.

- Network Mapping: Generate individual-specific parcellations to identify target networks (e.g., default mode, salience, control networks) [23].

- Target Identification: Use connectivity profiles to identify optimal stimulation sites based on individual anatomy.

- Outcome Monitoring: Track clinical outcomes and relate to network engagement.

- Iterative Refinement: Adjust targets based on individual response patterns.

Interpretation: Individual parcellations account for variability in functional anatomy, potentially improving neuromodulation efficacy by targeting personalized network nodes [1].

The teleological framework for brain parcellation emphasizes that method selection should be driven by specific research questions and clinical applications rather than the pursuit of a universal optimal solution. For studies focused on individual-specific brain signatures, the evidence strongly supports using multiple parcellation schemes to verify the robustness of findings [23] [6], with a preference for individual-specific parcellation approaches when capturing person-specific features is critical [1] [27]. The growing availability of standardized evaluation metrics [22] [25] and the development of increasingly sophisticated learning-based methods [1] are paving the way for more precise, personalized brain mapping that can advance both basic neuroscience and clinical applications in drug development and personalized medicine. As the field moves forward, the integration of multimodal data and the development of application-specific validation standards will be crucial for realizing the full potential of brain parcellation in precision neuroscience.

Building the Neural Fingerprint: Methodologies for Capturing Stable Individual-Specific Parcellations

Multi-Session Hierarchical Bayesian Models (MS-HBM) represent a significant methodological advancement in computational neuroimaging, specifically designed to estimate individual-specific brain network parcellations from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) data. Traditional group-level brain parcellations, while informative for population-level studies, obscure meaningful individual differences in brain organization by averaging data across subjects [28]. The MS-HBM framework addresses this limitation by explicitly modeling and separating different sources of variability in functional connectivity profiles, thereby enabling the delineation of individual-specific cortical networks with unprecedented precision [28] [29].

This approach is particularly valuable within the context of individual-specific brain signature stability research, as it provides a robust mathematical framework for identifying stable neural fingerprints that persist across time and imaging sessions. By accounting for both inter-subject (between-subject) and intra-subject (within-subject) functional connectivity variability, MS-HBM offers a more nuanced understanding of brain organization than previous methods that potentially conflated these distinct sources of variation [28]. The ability to reliably identify individual-specific network topography has profound implications for both basic neuroscience and clinical applications, including the development of personalized interventions for neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions [30].

MS-HBM Theoretical Framework and Architecture

Core Model Components

The MS-HBM is built upon a hierarchical structure that systematically accounts for different levels of variability in functional connectivity data. The model incorporates several key parameters:

- Group-level connectivity profiles (μlg): Represent the average connectivity pattern for each network

lacross all subjects and sessions [29]. - Inter-subject variability (εl): Quantifies how much each subject-specific connectivity profile (μls) deviates from the group-level profile [29].

- Intra-subject variability (σl): Captures how much session-specific profiles (μls,t) vary around the subject-specific profile [29].

- Inter-region variability (κ): Accounts for variability in connectivity profiles between different regions belonging to the same network [29].

- Spatial priors (V and Θl): Encourage spatially smooth parcellations and incorporate prior knowledge about the likely spatial distribution of networks [29].

The model assumes that the observed functional connectivity profile Xns,t of vertex n for subject s during session t follows a von Mises-Fisher distribution with mean direction μls,t and concentration parameter κ [29]. This probabilistic formulation allows for natural quantification of uncertainty in the parcellation estimates.

Workflow and Algorithmic Implementation

Figure 1: MS-HBM Computational Workflow. The model employs a hierarchical approach to estimate individual-specific parcellations, incorporating multiple levels of variability. Key steps include estimation of group-level priors, inter-subject variability, intra-subject variability, spatial priors, and finally individual-specific network labels. The variational Bayes expectation-maximization (VBEM) algorithm is typically used for parameter estimation [29] [31].

The estimation of MS-HBM parameters typically employs a variational Bayes expectation-maximization (VBEM) algorithm, which iteratively optimizes the model parameters and hidden variables [29]. This approach provides computational efficiency while maintaining theoretical guarantees for convergence. For practical implementation with single-session fMRI data—a common scenario in research settings—the model incorporates a workaround where the single fMRI run is split into two pseudo-sessions, an approach that has been empirically validated to perform well [29].

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Generalizability Across Imaging Modalities

Extensive validation studies have demonstrated the superior performance of MS-HBM compared to alternative parcellation approaches. The method shows excellent generalizability to both new resting-state fMRI data and task-based fMRI data from the same subjects [28]. Remarkably, MS-HBM parcellations estimated from just 10 minutes of rs-fMRI data (a single session) demonstrate comparable generalizability to state-of-the-art methods using 50 minutes of data (five sessions) [28].

Table 1: MS-HBM Generalizability Performance Across Datasets

| Dataset | Subjects | Sessions | Key Finding | Comparison Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSP Test-Retest [28] | 69 | 2 | MS-HBM (10 min) ≈ Other methods (50 min) | Group-level, Other individual parcellations |

| CoRR-HNU [28] | 30 | 10 | High test-retest reliability | ICC for network surface areas |

| HCP S900 [28] | 881 | 2 | Improved behavioral prediction | Connectivity strength-based approaches |

Stability Across Magnetic Field Strengths

Recent research has validated the consistency of individual-specific parcellations across different magnetic field strengths, demonstrating the robustness of these neural fingerprints to technical variations. A 2024 study comparing 3.0T and 5.0T MRI scanners found that individualized cortical functional networks showed high spatial consistency (Dice coefficient significantly higher within subjects than between subjects) and functional connectivity consistency across field strengths [32].

Table 2: Parcellation Consistency Across Magnetic Field Strengths

| Metric | 3.0T vs 5.0T Consistency | Assessment Method | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Consistency | Significantly higher within subjects | Dice coefficient | Individual topography preserved across scanners |

| Functional Connectivity | Highly consistent | Euclidean distance | Functional organization stable |

| Graph Theory Metrics | Positive cross-subject correlations | Network topology measures | Individual network properties maintained |

The stability of these individualized parcellations across different acquisition parameters supports their utility as reliable neural fingerprints for longitudinal studies and multi-site research initiatives [32].

Protocol for MS-HBM Implementation

Parameter Estimation and Model Fitting

Implementation of MS-HBM requires careful estimation of several key parameters:

Inter-region variability estimation: Generate binarized connectivity profiles for equally spaced vertices across the cortical surface (typically 1483 vertices), defined as the top 10% of vertices with strongest functional connectivity to each seed vertex [31].

Group-average parcellation: Derive a population-level network parcellation using averaged binarized connectivity profiles across all participants [31].

Intra-subject variability with limited data: For studies with only one scanning session per subject, split time series data into two halves, treating them as separate sessions [31].

Inter-subject variability estimation: Use resampling methods (e.g., 50 sets of 200 subjects randomly resampled) when computational resources are limited, averaging estimates across resampling iterations [31].

Tuning parameters selection: Optimize parameters such as smoothness prior (c = 40) and group spatial prior (α = 200) based on validation datasets like the Human Connectome Project [31].

Individual-Specific Parcellation Generation

Once group-level parameters are estimated, individual-specific parcellations are generated for each subject's functional connectivity time series data using the VBEM algorithm. The model typically parcellates brain function into 17 networks, representing an optimal solution for capturing correlation structure between cortical regions while enabling comparison with existing literature [31].

Validation and Quality Control

To ensure parcellation quality, researchers should implement the following validation steps:

Functional homogeneity calculation: Compute the average BOLD time series correlation between all pairs of vertices assigned to the same network, with higher values indicating better functional coherence within networks [31].

Test-retest reliability assessment: For subsets of subjects with repeated scans, calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for individual network surface areas and Dice coefficients for whole-brain topographic organization between timepoints [31].