In-Scanner Head Motion and Executive Function: Unraveling the Link for Robust Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Drug Development

This article synthesizes current research on the critical, often confounding, relationship between executive function and in-scanner head motion.

In-Scanner Head Motion and Executive Function: Unraveling the Link for Robust Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the critical, often confounding, relationship between executive function and in-scanner head motion. It establishes head motion as a systematic source of bias in neuroimaging data, particularly for populations where executive function is a primary outcome or trait of interest. We explore foundational evidence linking motion to neural efficiency, methodological frameworks for its quantification and mitigation, and advanced techniques for validating brain-behavior associations against spurious motion-related effects. Finally, we discuss the implications of these findings for developing reliable neuroimaging biomarkers in clinical neuroscience and drug development, providing researchers and professionals with a comprehensive guide to optimizing study design and data interpretation.

The Inextricable Link: How Executive Function Traits Govern In-Scanner Head Motion

Executive functions (EFs) represent a suite of top-down mental processes essential for goal-directed behavior, planning, and adapting to novel challenges. This whitepaper delineates the three core EFs—inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility—as established by cognitive neuroscience literature [1] [2]. Furthermore, it examines the critical, yet often overlooked, relationship between deficits in these executive components and in-scanner head motion during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This relationship poses a significant methodological challenge for neuroimaging research, potentially leading to the systematic exclusion of participants with lower executive functioning and biasing samples in studies of aging and clinical populations [3] [4]. We synthesize current research, present quantitative data on EF development and its correlation with motion, detail experimental protocols for assessment, and provide visual workflows to guide researchers and drug development professionals in addressing this confound.

Executive functions are higher-order cognitive control processes that regulate thoughts and actions to facilitate the achievement of chosen goals [5]. They are crucial for mental and physical health, success in academic and professional settings, and overall quality of life [1] [2]. These skills are primarily subserved by neural networks involving the prefrontal cortex, although they are not exclusively localized to this region and involve complex cortical and subcortical circuits [6] [5].

The "core" executive functions, as identified by factor-analytic studies, are Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Cognitive Flexibility [1] [2]. From these foundational components, more complex, higher-order EFs such as reasoning, problem-solving, and planning are built [2]. Understanding the individual trajectory and neurobiological basis of each core component is vital for researching cognitive decline, developing cognitive enhancers, and interpreting neuroimaging data accurately.

The Core Components of Executive Function

Inhibitory Control

Inhibitory control involves the ability to consciously control one's attention, behavior, thoughts, and/or emotions to override a strong internal predisposition or external lure [2]. It enables individuals to resist temptations, suppress impulsive actions, and selectively focus attention by inhibiting distracting information [1] [2].

- Function: This skill is essential for self-regulation, enabling behavioral change and conscious choice instead of automatic, habitual responses. It allows for delayed gratification and is critical for resisting premature responding in experimental settings [2].

- Neuroanatomy: The prefrontal cortex, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex, plays a key role, alongside subcortical structures like the subthalamic nucleus [5].

- Assessment: Common paradigms include the Stroop test, where participants must name the color of a word while inhibiting the prepotent response to read the word itself [1], and Go/No-Go tasks, which require responding to frequent stimuli and withholding responses to infrequent ones.

Working Memory

Working memory is a system for temporarily holding and manipulating information necessary for complex cognitive tasks like learning, reasoning, and comprehension [1] [2]. It is not merely a passive store but an active "workspace" for mental operations.

- Function: It allows for the integration of new information with existing knowledge over time, enabling the updating of mental models and guiding future behavior based on recent experiences [1].

- Neuroanatomy: The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is heavily implicated, interacting with parietal and temporal lobes [5].

- Assessment: It is often measured using n-back tasks, where individuals indicate when a current stimulus matches one presented n steps earlier, or digit span tasks that require recalling sequences of numbers in forward or reverse order.

Cognitive Flexibility

Cognitive flexibility, also termed set-shifting or mental flexibility, is the ability to adapt thinking and behavior in response to changing goals, rules, or environmental stimuli [1] [2]. It underlies creativity and the capacity to see issues from multiple perspectives.

- Function: This EF is engaged during multitasking, when solving problems with ineffective initial strategies, and when using empathy to consider another person's viewpoint [1].

- Neuroanatomy: Cognitive flexibility relies on a network involving the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex [5].

- Assessment: The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) is a classic measure, where participants must discover changing sorting rules. Task-switching paradigms also assess the cost in speed and accuracy when shifting between different mental sets.

Table 1: Developmental Trajectory of Core Executive Functions

| Executive Function | Onset & Development | Peak Performance | Decline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Memory | Develops through childhood and adolescence [5] | Early 30s [1] | Begins post-35, continues into older age [1] |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Develops from age 3; some theories suggest maturation up to ~age 29 [1] | Young Adulthood | Not specified in search results, but generally declines with age |

| Inhibitory Control | Begins in infancy [1] [5] | Not specified | Begins in the 60s [1] |

The Link Between Executive Function and In-Scanner Head Motion

A growing body of evidence indicates that individual differences in executive functioning are systematically related to the amount of head motion exhibited during fMRI scans. This association presents a significant confound for neuroimaging studies, particularly in aging and clinical populations.

Empirical Evidence of the Association

Research by Hausman et al. (2022) directly investigated this link in a sample of 282 healthy older adults (aged 65-88) [3] [4]. The study used the number of "invalid scans" flagged as motion outliers as the primary metric for in-scanner head motion.

- Findings: Spearman's Rank-Order correlations revealed that a higher number of invalid scans was significantly associated with poorer behavioral performance on standardized tasks measuring inhibition and cognitive flexibility [3] [4].

- Specificity: The association was domain-specific. Head motion was not significantly related to performance on tasks of working memory, verbal memory, or processing speed, highlighting the particular vulnerability of inhibition and flexibility in this context [3].

- Age as a Covariate: The study also confirmed that head motion increases with older age, compounding the problem in aging research [3].

This phenomenon is not limited to older adults. A large-scale study in children and adolescents also found that subject age was highly correlated with head motion, and that motion had a pervasive, degrading effect on multiple types of functional connectivity analyses [7].

Implications for Neuroimaging Research and Drug Development

The association between EF and head motion has profound implications:

- Sampling Bias: The standard practice of excluding participants with excessive motion from fMRI analyses may systematically remove older adults or clinical patients with lower executive functioning [3] [4]. This biases samples towards healthier, higher-functioning individuals, potentially leading to underestimations of neural dysfunction and compromised generalizability of findings.

- Confounded Results: In studies of neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration, age-related changes in brain connectivity can be confounded by age-related changes in motion, as both are intertwined [7]. Failing to control for motion can lead to spurious conclusions about brain-behavior relationships.

- Clinical Trials: In drug development, if a cognitive enhancer improves executive function, a reduction in head motion could be a secondary, behavioral outcome. Conversely, if motion is not accounted for, it can artifactually influence fMRI-based biomarkers, making it difficult to discern true drug effects on neural circuitry from motion-related artifacts.

Table 2: Association Between Head Motion and Cognitive Performance in Older Adults (Hausman et al., 2022)

| Cognitive Domain | Association with Head Motion | Statistical Significance | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | Significant negative correlation | p < .05 | Poorer inhibition linked to more motion [3] |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Significant negative correlation | p < .05 | Poorer flexibility linked to more motion [3] |

| Working Memory | No significant correlation | p > .05 | Motion not related to working memory [3] |

| Processing Speed | No significant correlation | p > .05 | Motion not related to processing speed [3] |

| Verbal Memory | No significant correlation | p > .05 | Motion not related to verbal memory [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing the EF-Motion Link

To rigorously investigate the relationship between executive function and in-scanner head motion, researchers can employ the following methodological framework, drawing from the cited studies.

Participant Recruitment and Screening

- Sample: Recruit a sample that captures a wide range of executive functioning, such as healthy older adults (e.g., 65+ years) [3].

- Exclusion Criteria: Screen for standard fMRI contraindications (e.g., metal implants), major psychiatric illness, history of significant head injury, and formal diagnosis of neurological disease or mild cognitive impairment. Tools like the Uniform Data Set (UDS) of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) can be used to screen for cognitive impairment [3].

Cognitive Assessment Protocol

A comprehensive neuropsychological battery should be administered to assess the three core EFs.

- Inhibitory Control:

- Working Memory:

- Digit Span Backward: A subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Participants repeat sequences of numbers in reverse order. The longest correctly recalled sequence is the score.

- Cognitive Flexibility:

- Trail Making Test (TMT) Part B: Participants connect numbers and letters in an alternating sequence (1-A-2-B-3-C...). The time to completion is the primary measure, with longer times indicating poorer flexibility [3].

fMRI Data Acquisition and Motion Quantification

- Acquisition: Acquire structural (e.g., T1-weighted MPRAGE) and resting-state or task-based fMRI data on a 3T scanner. For resting-state, instruct participants to keep their eyes open, fixate on a crosshair, and remain still [3] [7].

- Motion Tracking: Use prospective motion correction methods if available. During acquisition, use foam pads to stabilize the head and monitor motion in real-time [3] [7].

- Motion Quantification: Calculate mean relative volume-to-volume displacement as the primary motion metric. This summarizes total translation and rotation across all three axes between consecutive volumes [7]. Flag scans with excessive motion (e.g., framewise displacement >0.9 mm) as "invalid" for subsequent scrubbing [3].

Statistical Analysis

- Correlational Analysis: Use non-parametric tests like Spearman's Rank-Order correlation to assess the relationship between the motion metric (e.g., number of invalid scans) and performance on each EF task [3].

- Regression Modeling: Employ regression models to examine the effect of age on connectivity metrics (e.g., functional connectivity within the default mode network) with and without motion as a covariate, demonstrating its confounding influence [7].

Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for EF and Motion Research

| Tool Name / Concept | Function / Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Stroop Test | A behavioral paradigm assessing inhibitory control and interference control [1] [2]. | Gold-standard task for measuring the inhibition component of EF in relation to motion. |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) Part B | A pen-and-paper neuropsychological test measuring cognitive flexibility and set-shifting [3]. | Used to correlate cognitive flexibility performance with in-scanner motion metrics. |

| Mean Relative Displacement | A quantitative metric from fMRI data processing summarizing volume-to-volume head motion [7]. | Primary dependent variable for quantifying in-scanner motion and its correlation with EF scores. |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | A specific calculation of volume-to-volume head motion; scans with FD >0.9 mm are often "scrubbed" [3]. | Used to define "invalid scans" and create a motion outlier count for each participant. |

| Prospective Motion Correction | Real-time tracking and adjustment of the scanner's field of view to compensate for head motion [3]. | A technical solution to acquire cleaner data and reduce the exclusion of "high-mover" participants. |

| Mock Scanner Session | A practice session in a decommissioned MRI scanner with acoustic noise and motion feedback [7]. | An acclimatization procedure to reduce anxiety and minimize head motion during the actual scan. |

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

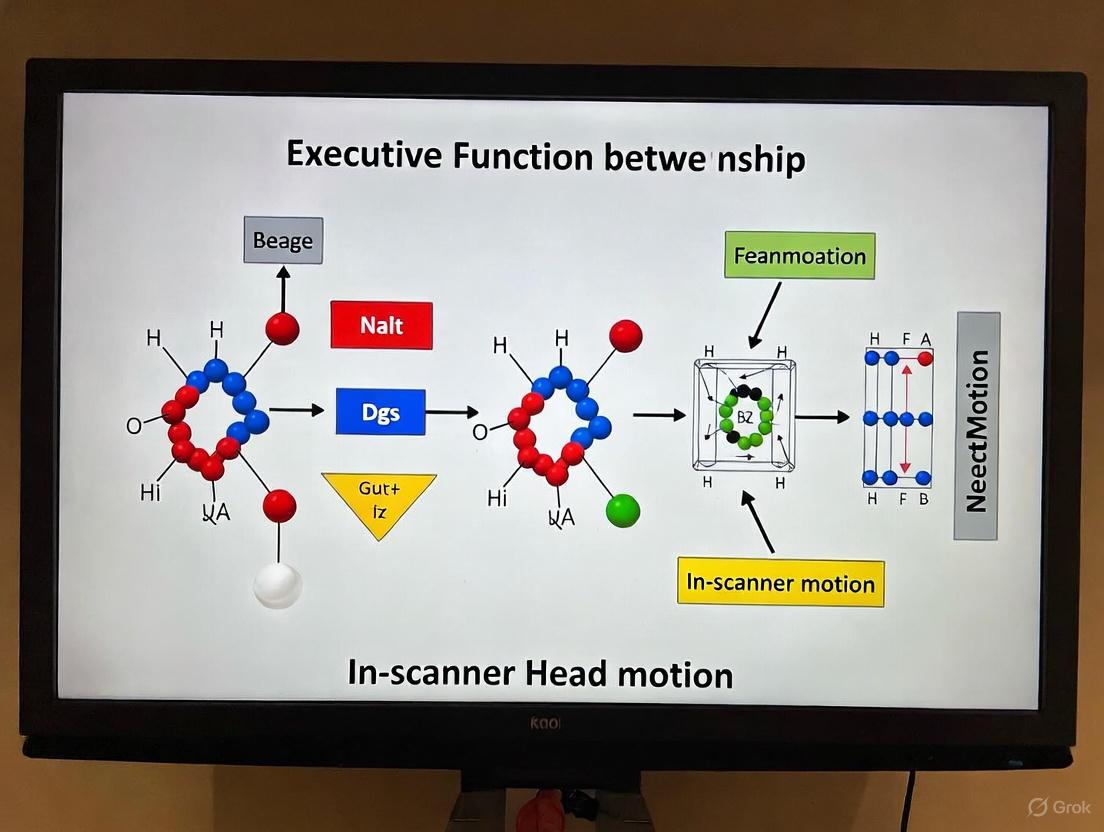

Diagram 1: EF Deficits Lead to Research Bias

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow

The core components of executive function—inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility—are distinct yet interrelated processes with unique developmental trajectories and neural substrates. Critically, deficits in specific EFs, namely inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility, are associated with increased head motion during fMRI scans in older adults. This relationship introduces a substantial methodological confound, threatening the validity and generalizability of neuroimaging findings in cognitive neuroscience and clinical drug trials. Future research must prioritize the development and implementation of advanced motion correction techniques and rigorous statistical control for motion to prevent the systematic exclusion of informative participants and to ensure accurate characterization of brain function across the lifespan and in clinical populations.

A growing body of evidence indicates that executive function (EF) deficits serve as a significant predictor of increased motion across diverse populations, presenting substantial methodological and clinical implications. This whitepaper synthesizes findings from aging, neurodevelopmental, and psychiatric research to demonstrate that EF capacities—particularly inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory—systematically relate to motion behaviors in experimental settings. The relationship between EF and motion not only poses critical challenges for neuroimaging research but also offers valuable insights into transdiagnostic cognitive profiles and potential intervention targets. This review integrates quantitative evidence, details experimental methodologies, and provides practical resources to advance research on the EF-motion relationship.

Executive functions (EFs) represent a collection of interrelated cognitive control processes including working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility that collectively enable goal-directed behavior and self-regulation [8]. A compelling body of research suggests that individual differences in EF capacity may manifest not only in cognitive tasks but also in motor behaviors, particularly the ability to maintain stillness during experimental procedures such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The relationship between EF and motion presents both a methodological challenge and a phenomenon of substantive interest. From a methodological perspective, head motion during fMRI scans introduces significant artifacts that can compromise data quality and validity [3]. From a clinical perspective, the EF-motion relationship may reflect shared neurobiological substrates and serve as a behavioral marker of cognitive control deficits across neurological and psychiatric conditions.

This technical review synthesizes evidence from multiple domains to establish EF as a predictor of motion, with particular focus on aging, neurodevelopmental, and psychiatric populations. We provide a comprehensive analysis of experimental protocols, quantitative findings, and methodological considerations to guide future research and clinical application.

Theoretical Framework and Neurobiological Basis

Executive Function Components and Motion Regulation

Executive functions facilitate motion control through multiple cognitive mechanisms. Inhibitory control enables the suppression of automatic movements and postural adjustments. Working memory maintains task instructions (e.g., "remain still") actively in mind. Cognitive flexibility allows rapid shifting between micro-adjustments and stillness maintenance. Attentional processes continuously monitor body position and correct deviations [8].

The relationship between EF and motion is conceptually bidirectional at a theoretical level, though empirical evidence specifically testing this directional relationship is limited. Reduced EF may lead to increased motion through poor implementation of verbal instructions, inconsistent self-monitoring, and diminished impulse control. Conversely, motion may impact EF measurement by introducing artifacts in neuroimaging data and disrupting cognitive task performance.

Shared Neural Substrates

The neural circuitry supporting EF overlaps significantly with networks involved in motion control. The prefrontal cortex, particularly the dorsolateral and ventrolateral regions, coordinates cognitive control processes that regulate both thought and action [8]. These frontal regions project to subcortical structures including the basal ganglia and cerebellum, which integrate cognitive commands with motor execution. This shared neuroanatomy provides a basis for the observed correlations between EF performance and motion control.

Figure 1: Shared Neural Circuitry for Executive Function and Motion Control. The prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate support executive processes that regulate motion control through connections with motor regions. Disruption in these networks may manifest in both EF deficits and increased motion.

Empirical Evidence Across Populations

Aging Populations

In healthy older adults, EF capabilities systematically predict motion during neuroimaging. A study of 282 healthy older adults (aged 65-88 years) found that greater in-scanner head motion was significantly associated with poorer performance on specific EF tasks: inhibition (β = -0.18, p < 0.01) and cognitive flexibility (β = -0.16, p < 0.05) [3]. This relationship persisted after controlling for age, which was also correlated with motion. Notably, head motion was not significantly associated with working memory, verbal memory, or processing speed, suggesting specificity to certain EF domains.

Beyond direct motion prediction, EF measures in older adults predict mobility outcomes with functional significance. A 12-month randomized controlled exercise trial with 179 community-dwelling older adults found that baseline performance on the flanker task (β = 0.15-0.17) and Wisconsin Card Sort Test (β = 0.11-0.16) consistently predicted mobility outcomes at 12-month follow-up, including timed up-and-go performance and stair climbing speed [9]. These findings demonstrate the real-world implications of EF for motor control in aging.

Table 1: Executive Function as Predictor of Motion and Mobility in Aging Populations

| Study | Sample | EF Measures | Motion/Mobility Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | 282 healthy older adults (65-88 years) | Inhibition, cognitive flexibility, working memory | In-scanner head motion (number of invalid scans) | Greater head motion associated with poorer inhibition (β=-0.18) and cognitive flexibility (β=-0.16) |

| [9] | 179 community-dwelling older adults | Flanker task, Wisconsin Card Sort Test, task switching | Timed up-and-go, stair climbing speed | Baseline EF predicted 12-month mobility (flanker β=0.15-0.17; WCST β=0.11-0.16) |

| [10] | 778 older adults (Mage=71.42) | Inhibition, updating, shifting | Class membership (lower EF/unidimensional structure) | Identified EF class with poorer performance showed more unidimensional structure |

Neurodevelopmental Populations

EF deficits represent a transdiagnostic feature of neurodevelopmental conditions (NDCs) according to a comprehensive meta-analysis of 180 studies [11]. Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show significant EF impairments compared to typically developing peers, with moderate effect sizes across conditions (g = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.49-0.63). These EF challenges directly impact functional abilities, including motion control.

A study comparing children with ASD (n=47), ADHD (n=34), and typical development (n=30) found that children with more severe EF profiles exhibited greater daily impairment and higher parental stress [12]. While not directly measuring motion, these findings suggest that EF deficits in neurodevelopmental conditions manifest in behavioral regulation difficulties that likely extend to motion control.

Table 2: Executive Function Profiles in Neurodevelopmental Conditions

| Condition | Overall EF Effect Size | Most Impaired Domains | Functional Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | g = 0.63 [11] | Attention, response inhibition, planning, working memory [11] | Disruptive behavior, social impairment [12] |

| ASD | g = 0.61 [11] | Set-switching, cognitive flexibility [11] | Social interaction difficulties, repetitive behaviors [12] |

| Comorbid NDCs | g = 0.72 [11] | Cross-domain impairments | Increased functional impairment [12] |

| Tic Disorders | g = 0.35 [11] | Mild across domains | Lesser functional impact |

Psychiatric Populations

In depressive disorders, EF performance demonstrates predictive validity for treatment response and functional outcomes. A study with 95 inpatients with depression found that reaction time on working memory tasks significantly predicted symptom reduction after treatment (β = -0.24, p < 0.05), indicating that EF capacities may influence clinical course [13]. Patients with depression exhibited significant impairments across all EF domains compared to healthy controls except for accuracy of inhibition control.

Longitudinal research with a community sample of Norwegian children (n=874) followed from age 6 to 14 revealed bidirectional relationships between EF and psychopathology. Reduced EF predicted increased symptoms of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder two years later (B = 0.83, 95% CI [0.37, 1.3]), even when adjusting for previous symptom changes [14]. Conversely, increased psychopathology predicted subsequent reductions in EF (B = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.02]), suggesting a transactional relationship.

Parkinson's Disease

Parkinson's disease provides a compelling model for EF-motion relationships due to its combined motor and cognitive features. A machine learning study with 103 geriatric Parkinson's inpatients found that walking features—particularly step time variability, double limb support time variability, and gait speed under dual-task conditions—predicted EF performance as measured by the Trail-Making Test (Δ-TMT) [15]. This relationship was most pronounced during cognitively demanding walking conditions, highlighting the role of EF in motor control under challenge.

Methodological Considerations

Assessing Executive Function

EF assessment typically employs either performance-based measures or informant ratings, each with distinct strengths. Performance-based measures include direct cognitive tasks such as the Flanker task (inhibitory control), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (mental set shifting), N-back (working memory), and Trail-Making Test (cognitive flexibility) [9] [13]. Informant measures such as the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) provide ecological validity by capturing everyday EF manifestations [11].

Meta-analytic evidence indicates that informant-based measures typically yield larger effect sizes (g = 1.49) than performance-based measures (g = 0.51) when comparing clinical populations to controls, possibly because they capture real-world functional limitations [11]. However, the choice of measure should align with research objectives—performance measures for specific cognitive mechanisms versus informant reports for functional impact.

Measuring Motion

Motion quantification varies by context and methodology. In neuroimaging research, motion is typically quantified using framewise displacement (FD), which calculates head position changes between consecutive volumes [3]. Scans exceeding predetermined thresholds (e.g., FD > 0.9mm) are flagged as invalid, with the number of invalid scans serving as a motion metric.

In mobility research with clinical populations, motion assessment includes instrumented measures (e.g., inertial measurement units quantifying step time variability, double limb support time) [15] and functional performance measures (e.g., timed up-and-go, stair climbing) [9]. The convergence across measurement approaches strengthens confidence in the EF-motion relationship.

Figure 2: Assessment Approaches for Executive Function and Motion. Multiple methodological approaches capture EF (performance-based tasks and informant reports) and motion (neuroimaging metrics, motor performance, and clinical observation), with different assessment pairings naturally aligned.

Analytical Approaches

Advanced analytical methods enable more precise characterization of EF-motion relationships. Machine learning approaches such as support vector regression have successfully predicted EF performance from walking features in Parkinson's disease [15]. Person-centered approaches like factor mixture modeling identify subgroups with distinct EF profiles [10], while random forest analysis determines the relative importance of multiple predictors in classifying these subgroups.

Longitudinal designs with cross-lagged panel models permit examination of bidirectional relationships between EF and motion-related outcomes [14]. These approaches adjust for time-invariant confounders and reveal temporal precedence, strengthening causal inference.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods for EF-Motion Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) | Quantifies spatio-temporal walking features | Step time variability, double limb support time in Parkinson's disease [15] |

| fMRI-Compatible Motion Tracking | Real-time head motion quantification during scanning | Framewise displacement calculation; identification of motion outliers [3] |

| EF Task Batteries | Assess specific executive components | Flanker task (inhibition), Wisconsin Card Sort (set-shifting), N-back (working memory) [9] |

| Informant Report Measures | Captures real-world EF manifestations | Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) for ecological validity [11] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Predictive modeling of EF-motion relationships | Support vector regression for predicting EF from walking features [15] |

| Data Imputation Methods | Handles missing motion or EF data | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) for incomplete datasets [15] |

Implications and Future Directions

Methodological Implications

The systematic relationship between EF and motion has profound implications for neuroimaging research. Exclusion of participants with excessive motion may inadvertently bias samples against individuals with lower EF, potentially skewing results and limiting generalizability [3]. This is particularly problematic in studies of aging and clinical populations where EF deficits are more prevalent.

Future research should implement prospective motion correction techniques [3] and statistical approaches that account for motion-related variance without excluding informative participants. Measuring and reporting EF capacity in neuroimaging studies would enhance interpretation of motion-related data quality issues.

Clinical Implications

EF assessment may serve as a screening tool for identifying individuals likely to exhibit challenging motion during diagnostic procedures. Pre-scan EF evaluation could trigger implementation of enhanced motion-reduction protocols for vulnerable individuals, potentially improving diagnostic accuracy.

The EF-motion relationship also suggests potential intervention targets. EF training protocols might indirectly improve motion control, enhancing compliance with medical procedures and functional mobility. Conversely, physical activity interventions that improve motor control may yield EF benefits through shared neural mechanisms [9].

Transdiagnostic Perspectives

EF deficits represent a transdiagnostic feature across neurological, neurodevelopmental, and psychiatric conditions [11]. The consistent relationship between EF and motion across these diverse populations suggests a general cognitive-biological mechanism whereby cognitive control capacities manifest in motor regulation. This transdiagnostic perspective encourages research跨越 traditional diagnostic boundaries to identify shared mechanisms and interventions.

Future research should examine whether specific EF components show differential relationships with motion across disorders, potentially informing targeted interventions. Longitudinal designs tracking EF and motion across development would illuminate their dynamic interplay and causal precedence.

Executive function capacities systematically predict motion across aging, neurodevelopmental, and psychiatric populations. This relationship reflects shared neural substrates and has important methodological implications for research and clinical practice. Specifically, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory emerge as key predictors of motion control during experimental procedures and functional mobility in daily life.

Understanding the EF-motion relationship enables improved research design, clinical assessment, and intervention development. Integrating EF assessment into motion-prone contexts and developing compensatory strategies for individuals with EF deficits represents a promising approach for enhancing research participation, diagnostic accuracy, and functional outcomes across diverse populations.

The Neural Efficiency Hypothesis (NEH) posits that individuals with higher cognitive ability utilize neural resources more economically, exhibiting lower and more focused brain activation when performing cognitive tasks compared to those with lower ability [16]. This article explores a critical extension of this principle: the manifestation of an efficient cognitive state as enhanced physical stability, specifically reduced in-scanner head motion during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). We examine the converging evidence that establishes in-scanner motion not merely as a technical confound but as a behavioral biomarker of executive function, thereby bridging the domains of neurocognitive efficiency and motor control. For researchers in drug development, this relationship provides a compelling non-behavioral endpoint for assessing the efficacy of cognitive enhancers and neurotherapeutics.

Core Principles of the Neural Efficiency Hypothesis

The foundational concept of neural efficiency was first introduced by Haier et al. (1988), who observed a negative correlation between intelligence test scores and cerebral glucose metabolic rates during cognitive task performance, as measured by Positron Emission Tomography (PET) [16]. This suggested that smarter brains work more efficiently, consuming less energy to achieve the same or better cognitive outcomes.

Subsequent research has refined this hypothesis, identifying several key moderating variables:

- Task Complexity: The inverse relationship between brain activation and intelligence is most consistent for tasks of low to moderate difficulty. When confronted with highly complex tasks, more intelligent individuals may actually show increased activation, reflecting a greater mobilization of cognitive resources to meet elevated demands [16] [17].

- Task Type and Domain Expertise: Neural efficiency is particularly evident for tasks that are novel or draw upon an individual's domain of expertise. For instance, expert athletes demonstrate more efficient brain activation patterns when imagining or performing skills from their own sport compared to novices [18] [19].

- Sex Differences: The brain regions demonstrating neural efficiency can vary by sex, with females often showing more efficient patterns on verbal tasks and males on spatial tasks, highlighting the influence of task-content interaction [16].

Table 1: Key Moderating Variables of the Neural Efficiency Hypothesis

| Moderating Variable | Impact on Neural Efficiency | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Task Complexity | Determines the direction of the intelligence-activation relationship | Negative correlation for easy tasks; can reverse to positive for very difficult tasks [16] [17]. |

| Domain Expertise | Enhances efficiency within the domain of expertise | Experts show lower, more focused activation in task-relevant networks [18] [19]. |

| Sex | Interacts with task content to influence efficient brain areas | Females show greater efficiency on verbal tasks; males on figural tasks [16]. |

| Brain Area | Efficiency is not uniform across the brain | Prefrontal and parietal regions often show the most pronounced efficiency effects [20]. |

The Executive Function-Head Motion Link: A Biomarker of Neural Efficiency

The connection between superior cognitive control and physical stillness provides a tangible, measurable outcome of an efficient neural system. A growing body of research indicates that in-scanner head motion is systematically related to cognitive performance, particularly in domains of executive function.

Empirical Evidence

- A study of 282 healthy older adults found that a higher number of motion-corrupted fMRI scans was significantly correlated with poorer performance on tasks of inhibition and cognitive flexibility [3] [4]. This suggests that the same cognitive control processes needed to suppress distracting impulses and shift mental sets are also required to suppress the impulse to move.

- This relationship is not limited to older adults. Research across the lifespan has shown that motion is a stable, trait-like characteristic, and that individuals with greater motion exhibit reduced functional connectivity in distributed brain networks like the default mode network, which is crucial for higher cognitive function [7].

- Critically, head motion confounds fMRI data by increasing short-distance correlations while decreasing long-distance correlations, a pattern that is the inverse of the mature, efficient brain network organization seen in high-performing individuals [7].

Theoretical Synthesis

The confluence of these findings supports a model wherein:

- Efficient Executive Function relies on the precise, coordinated operation of large-scale brain networks, particularly the fronto-parietal control network.

- Network Integrity in these same systems is essential for the top-down cognitive control required to remain still during lengthy scanning procedures. This includes sustained attention, impulse inhibition, and compliance with task instructions.

- Physical Stability as an Outward Manifestation: Therefore, reduced head motion is not merely the absence of movement but a positive indicator of the underlying integrity and efficiency of the executive control systems. An individual who can maintain physical stillness is likely demonstrating successful top-down inhibitory control, a core component of neural efficiency.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from seminal studies investigating neural efficiency and the head motion-executive function link.

Table 2: Key Studies on Neural Efficiency and Moderating Factors

| Study | Method | Key Finding | Quantitative Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haier et al. (1988) [16] | PET (Glucose Metabolism) | Negative correlation between intelligence and brain metabolism. | r = -0.48 to -0.84 (for different brain areas) |

| Doppelmayr et al. (2005) [16] [17] | EEG | Neural efficiency observed only for easy tasks; more intelligent individuals increased activation for difficult tasks. | Significant interaction (p < .05) between IQ and task difficulty on EEG bandpower. |

| Dunst et al. (2014) [17] | fMRI | Brain activation differences were only found for tasks with the same sample-based difficulty, not person-specific difficulty. | Significant activation differences (p < .05) only in sample-based difficulty condition. |

| Li & Smith (2021) [16] | fMRI (Athletes) | Athletes showed lower activation in sensory and motor cortex with less energy expenditure. | Lower BOLD signal and better performance (speed/accuracy) in experts. |

Table 3: Studies Linking Head Motion to Executive Function

| Study | Sample | Cognitive Domain | Correlation with Head Motion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hausman et al. (2022) [3] [4] | 282 healthy older adults | Inhibition & Cognitive Flexibility | Spearman's ρ: Significant negative correlation (p < .05) |

| Hausman et al. (2022) [3] | 282 healthy older adults | Working Memory & Processing Speed | Spearman's ρ: Non-significant correlation |

| Van Dijk et al. (2012, cited in Satterthwaite et al.) [7] | 456 youths (8-23 yrs) | Fluid Intelligence | Significant negative correlation with motion |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ground this synthesis in practical methodology, we outline the protocols from two pivotal studies.

Protocol 1: Investigating Neural Efficiency with Tailored Task Difficulty (fMRI)

This protocol is based on the work of Dunst et al. (2014) [17].

- Objective: To disentangle the effects of person-specific versus sample-based task difficulty on the neural efficiency phenomenon.

- Participants: 58 individuals divided into lower (n=28) and higher (n=30) intelligence groups.

- Task: Numerical inductive reasoning tasks (a strong indicator of fluid intelligence) were used. The key innovation was the use of Rasch-calibrated items, which allowed for the presentation of tasks with varying sample-based difficulty but equivalent person-specific difficulty.

- Lower Intelligence Group: Received sample-based easy and medium difficulty tasks.

- Higher Intelligence Group: Received sample-based medium and difficult tasks.

- Imaging Parameters:

- Technique: Functional MRI (fMRI).

- Analysis: Contrasted brain activation between groups for tasks with the same sample-based difficulty (the medium task) versus tasks with the same person-specific difficulty.

- Key Outcome Measures:

- Behavioral: Accuracy and reaction time on the reasoning tasks.

- Neurophysiological: BOLD signal change in fronto-parietal regions (inferior frontal gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal lobule).

- Conclusion: Performance and brain activation differences were found only when groups worked on tasks of the same sample-based difficulty, indicating that neural efficiency reflects an ability-dependent adaptation to task demands, not intelligence per se [17].

Protocol 2: Linking Head Motion and Executive Function in Older Adults (fMRI)

This protocol is based on Hausman et al. (2022) [3] [4].

- Objective: To assess the association between in-scanner head motion and cognitive performance in healthy older adults.

- Participants: 282 adults aged 65-88, screened for neurological and psychiatric conditions.

- Cognitive Assessment: A battery of tests was administered outside the scanner:

- Inhibition: Measured by the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Color-Word Interference Test.

- Cognitive Flexibility/Set-Shifting: Also measured with the D-KEFS.

- Processing Speed & Verbal Memory: Assessed for domain specificity.

- Imaging Acquisition and Motion Quantification:

- fMRI Parameters: Resting-state BOLD fMRI (124 volumes, TR/TE=3000/32 ms).

- Motion Management: Foam padding for stabilization. Prospective motion correction and retrospective analysis (e.g., FSL's MCFLIRT).

- Primary Motion Metric: The number of "invalid scans" flagged as motion outliers based on framewise displacement (e.g., FD > 0.9 mm).

- Statistical Analysis: Spearman's Rank-Order correlations between the number of invalid scans and scores on each cognitive test, controlling for age.

- Conclusion: A higher number of invalid scans was significantly associated with poorer inhibition and cognitive flexibility, confirming that head motion is a behavioral marker of lower executive control [3].

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this article.

Diagram 1: The Neural Efficiency-Head Motion Relationship

Diagram 2: Experimental fNIRS Protocol for Neural Efficiency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key methodologies and their applications in studying neural efficiency and its physical manifestations.

Table 4: Essential Methodologies for Neural Efficiency and Motion Research

| Method / Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Measures brain activity via the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal. | Gold standard for localizing task-evoked brain activity and testing NEH; also quantifies in-scanner head motion [17] [7]. |

| Functional NIRS (fNIRS) | Optical imaging technique measuring cortical hemodynamics (HbO2, HHb). | Field-deployable method for assessing prefrontal cortex workload and neural efficiency in ecological settings (e.g., flight simulators) [21]. |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | A quantitative metric derived from fMRI data, summarizing volume-to-volume head displacement. | Primary objective measure for identifying motion-corrupted scans ("scrubbing") and correlating motion magnitude with cognitive traits [3] [7]. |

| Rasch-Calibrated Cognitive Tasks | Psychometric tasks where item difficulty is calibrated on a continuous scale relative to participant ability. | Allows for precise matching of task difficulty across individuals with different intelligence levels, critical for isolating neural efficiency effects [17]. |

| Event-Related Desynchronisation (ERD) in Upper Alpha Band | An EEG metric reflecting a decrease in alpha power during cognitive activity. | A robust neurophysiological correlate of neural efficiency, indicating more focused cortical activation in brighter individuals [19]. |

This case study examines the interplay between physical activity (PA), executive function (EF), and in-scanner head motion in older adults. Evidence indicates that regular PA enhances EF and promotes neural efficiency, allowing for superior cognitive performance with less brain activation. Critically, this neural efficiency is associated with reduced in-scanner head motion, a key methodological confound in neuroimaging research. Our synthesis demonstrates that PA interventions yield significant improvements in inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, while fMRI data reveal that active older adults require less prefrontal activation to perform cognitive tasks. This has profound implications for designing cognitive assessments and interpreting neuroimaging data in aging populations, particularly in clinical trials for cognitive-enhancing therapeutics.

Executive functions are high-level cognitive processes essential for goal-directed behavior, comprising three core components: inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility [22]. These functions undergo a gradual decline in later adulthood, impacting autonomy and quality of life [22]. This decline is associated with an increased risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, presenting a significant challenge for an aging global population [23].

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become a gold standard for investigating the neural correlates of EF, offering superior spatial resolution for localizing brain activity [23]. However, a critical methodological challenge confounds this research: in-scanner head motion. Head motion has a pervasive, confounding effect on functional connectivity measures, artificially diminishing long-range connections while increasing local coupling [7]. This is particularly problematic in neurodevelopmental and aging studies, as the ability to remain still is often related to age [7]. The motion-related pattern of connectivity is, notably, the inverse of the genuine age-related changes, meaning uncontrolled motion can severely bias estimates of neurodevelopmental trajectories and cognitive decline [7].

This case study posits that physical activity is a key modulator at the intersection of EF enhancement and motion artifact reduction. We explore the evidence that PA not only improves cognitive performance but also optimizes neural function in a way that may mitigate a major source of noise in brain imaging research.

The Impact of Physical Activity on Executive Function: Quantitative Evidence

A growing body of research demonstrates that physical activity is an effective, non-pharmacological strategy for preserving and enhancing executive functions in the elderly. The benefits are observed across both acute and long-term interventions.

Long-Term Training Effects

A systematic review of studies from 2019-2025 confirms that PA positively affects all core components of EF in adults over 60. The magnitude of benefit, however, depends on the intervention's duration [22].

Table 1: Effects of Physical Activity Intervention Duration on Executive Function

| Intervention Duration | Effects on Core Executive Functions | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | Positively affects one or two components of EFs. | Benefits are limited and may not be comprehensive. |

| Medium- to Long-Term | Produces significant benefits for all components (working memory, inhibition, cognitive flexibility). | Leads to broader and more robust cognitive improvements. |

| Combined Interventions | PA combined with cognitive stimulation shows a greater impact than PA alone. | Suggests synergistic effects of multimodal interventions for maximizing cognitive health. |

Acute Exercise Bout Effects

The cognitive benefits of PA are not exclusive to long-term training. A 2024 study investigated the effects of a single 20-minute bout of moderate-intensity cycling in 48 healthy older adults [24].

Table 2: Cognitive Outcomes Following a 20-Minute Acute Exercise Bout

| Cognitive Test | Domain Tested | Key Result | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective Go/No-Go (AGN) | Inhibitory Control | The exercise group made significantly fewer commission errors on the positive valence condition post-exercise. | p = 0.004 |

| Spatial Working Memory (SWM) | Working Memory & Strategy | The exercise group showed significantly better performance post-exercise for total error and strategy use. | p = 0.027; p = 0.002 |

| Simple Reaction Time (SRT) | Processing Speed | No significant interaction of Group x Session was found. | Not Significant |

| Backward Counting | Working Memory & Attention | No significant interaction of Group x Session was found. | Not Significant |

The findings from this acute study indicate that inhibitory control and working memory are particularly sensitive to improvement even after a short bout of exercise, while other processes like simple processing speed may be less affected [24]. This selective improvement underscores the specific influence of PA on prefrontal cortex-mediated functions.

Neural Correlates of Physical Activity: The fMRI Evidence

Functional neuroimaging provides a window into the neural mechanisms underpinning the cognitive benefits of PA. A 2025 cross-sectional fMRI study compared brain activation in physically active (≥3000 MET-min/week) and inactive (<3000 MET-min/week) younger and older adults during EF tasks [23] [25].

Experimental Protocol and Cognitive Assessment

- Participants: 41 Chinese adults (21 young, 20 older).

- Physical Activity Measurement: International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF), with participants classified as active or inactive based on a threshold of 3000 MET-min/week [23].

- fMRI Tasks:

- Flanker Task: Measured inhibitory control by requiring participants to respond to a central arrow while ignoring flanking distractors.

- N-back Task: Assessed working memory by requiring participants to indicate when a current stimulus matched one presented "n" steps back.

- Switching Task: Evaluated cognitive flexibility by requiring participants to shift between different task rules.

- Analysis: Brain activation patterns were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) [23].

Key Findings on Brain Activation

The study yielded two critical insights:

- Behavioral Performance: Physically active older adults showed significantly better accuracy and faster reaction times on the Flanker task than their inactive peers [23].

- Neural Efficiency: In young adults, those who were inactive exhibited greater activation in prefrontal regions during executive tasks. No significant differences in brain activation were found for these tasks in older adults, suggesting that active older adults require less brain activation to perform EF tasks at a high level [23]. This pattern is indicative of enhanced neural efficiency in the active group.

Furthermore, correlation analyses revealed that in active older adults, better performance on cognitive flexibility was positively correlated with activation in the right dorsolateral frontal gyrus (Brodmann Area 32) [23]. This suggests that even within a high-performing group, the ability to recruit specific prefrontal regions efficiently is linked to superior cognitive outcomes.

The Critical Confound: In-Scanner Head Motion

The integrity of the fMRI findings discussed above is highly dependent on controlling for head motion. Van Dijk et al. first demonstrated that in-scanner head motion substantially impacts measurements of resting-state functional connectivity [7].

The Motion Artifact Problem

- Impact on Data: Increased head motion is associated with artificially diminished long-range connectivity and inflated local, short-range connectivity [7].

- Confounding with Age: Subject age is highly correlated with the ability to remain still during scanning. Younger children and older adults typically exhibit more motion [7].

- Inverse Pattern: The motion artifact (decreased long-range/increased short-range connectivity) is the inverse of genuine neurodevelopmental findings (increased long-range/decreased short-range connectivity with maturation). This means motion can create a false impression of age-related neural changes [7].

- Pervasive Effects: This confound affects not only seed-based connectivity but also graphical measures of network modularity, independent component analysis (ICA), and measures of low-frequency fluctuation amplitude (ALFF/fALFF) [7].

Methodological Protocols for Motion Mitigation

The following workflow outlines standard procedures to minimize and account for head motion in fMRI studies, which is critical for obtaining reliable data from older adult populations.

Synthesis: Physical Activity, Neural Efficiency, and Motion Reduction

The relationship between physical activity, enhanced executive function, reduced brain activation, and in-scanner motion can be synthesized into a coherent model. This model posits that PA induces neural efficiency, which facilitates both improved cognitive performance and greater physical stability during demanding tasks.

An Integrated Model

The following diagram illustrates the proposed mechanistic links, showing how physical activity leads to more reliable neuroimaging data and better cognitive outcomes.

Interpreting the Link

The model suggests that the neural efficiency fostered by physical activity [23] manifests not only as less "effortful" brain activation for cognitive tasks but also as superior motor control and stability. This directly translates to a reduction in the head motion confound. Consequently, studies involving physically active older adults are likely to yield cleaner fMRI data, leading to more accurate interpretations of brain function and the true effects of therapeutic interventions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

To replicate and advance research in this field, scientists require a specific set of validated tools and protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

| Item or Tool | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-SF) | A validated self-report tool to categorize participants into active and inactive groups based on MET-min/week thresholds [23]. |

| CANTAB Research Suite | A computerized neurocognitive battery providing well-validated, sensitive tasks for assessing EF (e.g., SWM, AGN) [24]. |

| Eriksen Flanker Task | A classic inhibitory control task administered during fMRI to measure the ability to suppress irrelevant stimuli [23]. |

| N-back Task | A working memory paradigm used in fMRI to assess the ability to temporarily store and manipulate information [23]. |

| Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) | A leading software package for the analysis of brain imaging data sequences, used to localize significant task-related activation [23]. |

| Mock MRI Scanner | A decommissioned scanner used to acclimate participants to the MRI environment, thereby reducing anxiety and motion [7]. |

| MoTrack Motion Tracking System | Provides real-time feedback on head movement during mock and actual scanning sessions, helping to train participants to remain still [7]. |

This case study establishes that regular physical activity in older adults is associated with a triple benefit: enhanced executive function, increased neural efficiency, and a reduction in the critical methodological confound of in-scanner head motion.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings have significant implications:

- Patient Stratification: Clinical trials for cognitive-enhancing drugs should consider physical activity levels as a key stratification variable. Failing to do so may introduce noise, masking a drug's true efficacy or creating false positives.

- Lifestyle Intervention as an Adjunct: Non-pharmacological interventions like structured PA could be explored as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy to boost overall treatment effects on cognitive health.

- Data Integrity: Proactive steps to minimize head motion, such as those outlined in the experimental workflow, are non-negotiable for obtaining high-quality, interpretable neuroimaging data in aging populations.

Future longitudinal research that combines PA interventions with repeated fMRI and rigorous motion tracking is needed to definitively establish causality and further elucidate the underlying neural mechanisms.

In-scanner head motion represents one of the most significant methodological challenges in functional neuroimaging, systematically introducing artifactual correlations that can be misinterpreted as neurophysiologically plausible brain-behavior relationships. This technical guide examines the mechanisms through which head motion generates these spurious associations, with particular emphasis on the complicated relationship between motion and executive function. As functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies increasingly focus on populations with naturally higher movement tendencies—including children, older adults, and individuals with psychiatric or neurological conditions—understanding these artifacts becomes methodologically essential. The systematic exclusion of "high-movers" may inadvertently bias samples by removing participants with lower executive functioning, potentially obscuring genuine neurobehavioral relationships [3] [4]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on motion artifacts, provides detailed methodological guidance for their identification and mitigation, and frames these issues within the broader context of executive function research.

Motion Artifacts in fMRI: Mechanisms and Manifestations

Fundamental Mechanisms of Motion-Induced Artifacts

Head motion during fMRI acquisition introduces artifacts through multiple physical mechanisms that fundamentally disrupt the spin history assumptions underlying MRI physics. Even after spatial realignment procedures, motion creates spin-history effects and partial volume effects that alter signal intensity in affected voxels [26] [27]. These disruptions occur because rigid body transformation corrects for spatial displacement but cannot compensate for the intensity changes resulting from physical disruption of magnetic field gradients during motion events [27]. The resulting artifacts manifest as systematic changes in the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal that correlate with movement parameters, creating spurious but structured patterns in functional connectivity data.

Resting-state fMRI proves particularly vulnerable to motion artifacts because the timing of underlying neural processes is unknown, making it difficult to distinguish motion-related signal changes from neurally-driven fluctuations [26]. Van Dijk et al. first characterized the distinctive spatial pattern of motion artifacts: increased short-distance connectivity coupled with decreased long-distance connectivity [7] [27]. This pattern emerges because motion affects neighboring voxels similarly while disrupting the temporal coupling between distant brain regions. Notably, these artifact patterns directly oppose the established neurodevelopmental trajectory of increasing long-range and decreasing short-range connectivity with brain maturation, creating particular confounding in developmental studies [7].

Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

The spatial signature of motion artifacts demonstrates remarkable consistency across studies and populations. Analysis of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study dataset (n = 7,270) revealed a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) between the motion-FC effect matrix and the average functional connectivity matrix, indicating that participants who moved more showed systematically weaker connection strengths across all functional connections [26]. This pattern persisted even after rigorous denoising and motion censoring at framewise displacement (FD) < 0.2 mm (Spearman ρ = -0.51) [26].

Temporally, motion artifacts exhibit properties that make them particularly difficult to distinguish from neural signals. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI studies demonstrate that even minor head motion (< 0.2 mm) induces low-frequency EEG fluctuations (< 20 Hz) that strongly correlate with motion parameters [28]. After convolution with the hemodynamic response function, these motion-contaminated EEG signals produce spurious but neurophysiologically plausible EEG-BOLD correlations that closely match true neural effects [28]. This parallel contamination across modalities underscores the pervasive nature of motion artifacts and their potential to generate apparently convergent evidence across measurement techniques.

Table 1: Spatial Patterns of Motion Artifacts in Functional Connectivity

| Connection Type | Effect of Motion | Potential Misinterpretation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-distance connections | Decreased connectivity | "Underconnectivity" in clinical populations | [7] [27] |

| Short-distance connections | Increased connectivity | Local hyperconnectivity | [7] [27] |

| Default mode network | Decreased connectivity | Network disruption in disorders | [7] |

| Frontoparietal network | Decreased connectivity | Executive dysfunction | [7] |

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of motion-induced artifacts in neuroimaging. Head motion creates artifacts through multiple pathways that ultimately generate spurious brain-behavior correlations.

The Executive Function Connection: A Complicating Relationship

Executive Function as Predictor of In-Scanner Motion

Executive functions—particularly inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and impulse control—strongly predict an individual's ability to remain still during scanning sessions. Research across diverse populations consistently demonstrates that poorer performance on executive function tasks associates with greater in-scanner motion. In healthy older adults (n=282), higher motion (quantified as the number of "invalid scans" flagged as motion outliers) significantly correlated with poorer performance on specific executive tasks: inhibition (Spearman's rho = -0.19, p < 0.01) and cognitive flexibility (Spearman's rho = -0.16, p < 0.01) [3] [4]. This relationship persisted after controlling for age, suggesting that executive decline specifically relates to motion rather than general age-related factors.

Similar patterns emerge in developmental and clinical populations. Children with conditions characterized by executive dysfunction (e.g., ADHD, autism spectrum disorder) consistently exhibit higher in-scanner motion than neurotypical peers [26] [29]. This association creates a systematic confounding wherein populations with executive function deficits become both the focus of study and more likely to exhibit motion artifacts that mimic their expected neural profiles. The very cognitive processes researchers aim to study thus become entangled with methodological artifacts.

Consequences of Systematic Exclusion

The standard practice of excluding high-motion participants introduces systematic sampling bias in studies examining executive function. Removing individuals with excessive motion disproportionately excludes those with lower executive abilities, potentially skewing sample characteristics and limiting generalizability [3]. In aging research, this practice may systematically eliminate older adults with executive decline—precisely the individuals of greatest interest—creating artificially "supernormal" samples that misrepresent population-level neurocognitive trajectories [3] [4].

Table 2: Executive Functions Associated with In-Scanner Motion

| Executive Domain | Specific Tasks | Strength of Association | Population Studied | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | Stroop, Flanker tasks | Spearman's rho = -0.19, p < 0.01 | Older adults | [3] |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Task switching, set-shifting | Spearman's rho = -0.16, p < 0.01 | Older adults | [3] |

| Impulse Control | Stop-signal task | Moderate association (p < 0.05) | Children and adolescents | [7] |

| Working Memory | n-back tasks | Not significantly associated | Older adults | [3] |

Quantitative Evidence: Magnitude of Motion Effects

Effect Sizes in Large-Scale Studies

Large-scale analyses demonstrate that motion effects can exceed the magnitude of genuine trait-FC relationships. In the ABCD Study sample (n=7,270), after standard denoising with ABCD-BIDS preprocessing, 42% (19/45) of behavioral traits showed significant motion overestimation scores (p < 0.05), while 38% (17/45) showed significant underestimation scores [26]. The largest motion-FC effect sizes for individual connections surpassed trait-FC effect sizes, indicating that motion-related variance can dominate true neurobehavioral relationships [26].

Even after extensive denoising procedures, motion explains substantial variance in fMRI signals. After minimal processing (motion correction only), head motion explained 73% of signal variance in the ABCD dataset. Following comprehensive denoising with ABCD-BIDS (including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion timeseries regression, and despiking), motion still explained 23% of signal variance—a 69% relative reduction but substantial absolute remaining influence [26].

Impact on Trait-FC Inferences

The SHAMAN (Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks) method, which quantifies trait-specific motion impact, reveals how motion artifacts distort specific brain-behavior relationships. Motion censoring at FD < 0.2 mm reduced significant overestimation from 42% to 2% of traits but did not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores [26]. This differential impact demonstrates that motion can both inflate and obscure true effects depending on the specific trait-FC relationship, complicating simple mitigation strategies.

Diagram 2: The confounding relationship between executive function and motion artifacts. Poor executive function predicts higher motion, which can lead to both systematic exclusion bias and spurious neurobehavioral associations.

Methodological Approaches: From Detection to Correction

Motion Quantification and Censoring

Framewise displacement (FD) remains the standard metric for quantifying volume-to-volume head motion, calculated as the sum of absolute translational and rotational displacements [7] [27]. Motion censoring (or "scrubbing") involves removing high-motion volumes exceeding predetermined FD thresholds, typically ranging from 0.2-0.5 mm depending on study requirements [26] [29]. Power et al. proposed complementary metrics including DVARS (rate of change of BOLD signal) and quality indices based on normative data [27].

While censoring reduces motion artifacts, it introduces new methodological challenges. Overly aggressive censoring (FD < 0.1 mm) may discard excessive data, particularly from populations with naturally higher motion, while lenient thresholds (FD > 0.3 mm) retain substantial motion contamination [26]. In the ABCD dataset, censoring at FD < 0.2 mm effectively addressed motion overestimation but did not reduce underestimation artifacts, indicating threshold-dependent efficacy [26].

Advanced Statistical Control Methods

SHAMAN Framework

The SHAMAN (Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks) method quantifies trait-specific motion impact by leveraging the temporal stability of traits versus the moment-to-moment variability of motion [26]. This approach:

- Splits each participant's timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on median FD

- Computes trait-FC correlations separately for each half

- Tests for significant differences between halves using permutation testing

- Classifies effects as motion overestimation (impact score aligned with trait-FC direction) or underestimation (opposite direction) [26]

SHAMAN operates on one or more rs-fMRI scans per participant and can incorporate covariates, providing a flexible framework for motion impact assessment specific to each brain-behavior relationship.

Surrogate Data and Statistical Correction

For data exhibiting temporal dependencies, surrogate data procedures effectively control for spurious correlations arising from power-law dynamics in both neural and behavioral measures [30]. This approach:

- Characterizes the temporal structure (α-exponent) of both neural and behavioral timeseries

- Generates surrogate data preserving the temporal structure but without true correlation

- Computes empirical significance values against the surrogate distribution [30]

This method correctly tests for presence of correlation while controlling for the effect of power-law dynamics, preventing spurious conclusions about brain-behavior relationships [30].

Table 3: Motion Mitigation Methods and Their Limitations

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Effectiveness | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denoising algorithms | ABCD-BIDS, global signal regression, motion parameter regression | Reduces motion-related variance by ~69% | Residual motion (23% variance) remains | [26] |

| Motion censoring | Framewise displacement thresholding (FD < 0.2-0.5 mm) | Reduces overestimation from 42% to 2% of traits | Does not address underestimation artifacts | [26] |

| Statistical controls | SHAMAN, surrogate data procedures | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact | Computationally intensive | [26] [30] |

| Prospective correction | MoTrack feedback, padding restraints | Modest reduction in motion | Cannot eliminate involuntary movements | [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Motion-Robust Research

Protocol 1: SHAMAN Implementation

The SHAMAN framework provides a standardized approach for assessing motion impact in brain-behavior studies:

Preprocessing Requirements:

- BOLD data processed through standard pipelines (e.g., ABCD-BIDS)

- Framewise displacement calculated for all volumes

- Exclusion of participants with >50% high-motion volumes (FD > 0.2 mm)

Implementation Steps:

- For each participant, split BOLD timeseries at median FD into high-motion and low-motion halves

- Compute functional connectivity matrices for each half using standard correlation methods

- Calculate trait-FC correlations for each half separately using robust regression

- Compute motion impact score as the difference between high-motion and low-motion trait-FC correlations

- Perform permutation testing (recommended 10,000 permutations) to assess significance

- Classify significant results as overestimation or underestimation based on alignment with trait-FC effect direction [26]

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Significant positive impact score indicates motion inflates trait-FC effect

- Significant negative impact score indicates motion obscures trait-FC effect

- Non-significant impact suggests trait-FC relationship robust to motion

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Motion Control in Executive Function Studies

For studies specifically examining executive function, enhanced motion control is methodologically essential:

Participant Screening and Preparation:

- Assess baseline executive function (inhibition, cognitive flexibility) before scanning

- Implement mock scanner training with real-time motion feedback

- Use foam padding and restraints to minimize head movement [7]

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- Multi-echo sequences to improve motion correction [26]

- Shorter TR (e.g., 0.7s) to increase temporal resolution

- Include field maps for improved distortion correction

Analysis Pipeline:

- Apply integrated denoising (e.g., ABCD-BIDS) including:

- Motion parameter regression (24 parameters)

- Global signal regression

- Respiratory filtering

- Spectral filtering (0.008-0.1 Hz)

- Despiking and interpolation of high-motion frames [26]

- Implement moderate censoring (FD < 0.2 mm)

- Apply SHAMAN to quantify motion impact specifically for executive function-FC relationships

- Include motion × executive function interactions in group-level models

- Conduct sensitivity analyses with varying motion thresholds

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion-Robust Neuroimaging

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement (FD), DVARS, RMS | Quantifies volume-to-volume head movement | FD threshold selection depends on population and TR |

| Denoising Packages | ABCD-BIDS, fMRIPrep, CONN | Implements comprehensive artifact removal | Pipeline choice affects residual motion patterns |

| Statistical Control | SHAMAN, ComBat, GLM with motion interactions | Controls for motion effects in group analyses | SHAMAN provides trait-specific impact scores |

| Prospective Correction | MoTrack, MRI-compatible eye tracking | Provides real-time motion feedback | Requires additional equipment and setup |

| Quality Assessment | MRIQC, visual inspection | Identifies motion-contaminated datasets | Establishes data quality thresholds |

| Experimental Control | Mock scanner training, padding restraints | Minimizes motion during acquisition | Particularly important for pediatric/clinical populations |

Head motion introduces spurious but neurophysiologically plausible brain-behavior correlations through multiple mechanistic pathways, presenting a fundamental methodological challenge in functional neuroimaging. The complicated relationship between executive function and in-scanner motion creates particular confounding, as the very populations of interest for executive function research often exhibit systematically higher motion. Contemporary approaches such as the SHAMAN framework provide powerful tools for quantifying and addressing these artifacts, moving beyond generic motion control to trait-specific impact assessment. As neuroimaging continues to advance our understanding of brain-behavior relationships, rigorous attention to motion artifacts remains essential for generating valid, reproducible findings—particularly in research examining executive processes across development, aging, and clinical populations.

Quantifying the Signal from the Noise: Advanced Methodologies for Motion Tracking and Artifact Reduction

In-scanner head motion is a paramount confound in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research, systematically biasing estimates of functional connectivity (FC) and threatening the validity of brain-behavior associations [27] [31] [26]. This is especially critical for studies investigating executive function, a set of higher-order cognitive processes including inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility [25]. Populations with developing or impaired executive function, such as children, older adults, or individuals with psychiatric disorders, often exhibit higher rates of in-scanner motion [32] [26]. This covariation can generate spurious correlations, leading researchers to conclude that executive function is related to specific neural patterns when the findings are, in fact, driven by motion artifact [26]. For instance, motion artifact systematically decreases long-distance FC and increases short-range FC [27] [33] [26], a pattern that could be misinterpreted as a neurobiological correlate of executive dysfunction. Consequently, rigorous quantification and mitigation of motion artifacts using framewise displacement (FD) and DVARS are not merely procedural steps but foundational to producing reproducible research on the neural basis of executive function.

Defining the Gold-Standard Motion Metrics

Framewise Displacement (FD) and DVARS are complementary metrics that provide a quantitative frame-by-frame index of head motion. They are derived from the realignment parameters generated during fMRI preprocessing when all volumes are aligned to a reference volume [34].

Framewise Displacement (FD)

FD expresses the instantaneous head-motion from one volume to the next. It is calculated as the sum of the absolute values of the derivatives of the six rigid-body realignment parameters [34]. The rotational displacements are converted from degrees to millimeters by calculating the displacement on the surface of a sphere of radius 50 mm, approximating the average distance from the cerebral cortex to the center of the head [34].

Mathematical Definition: The formula for FD at timepoint ( t ) is: [ \text{FD}t = |\Delta d{x,t}| + |\Delta d{y,t}| + |\Delta d{z,t}| + |\Delta \alphat| + |\Delta \betat| + |\Delta \gammat| ] where ( \Delta d{x,t}, \Delta d{y,t}, \Delta d{z,t} ) are the translational displacements (in mm), and ( \Delta \alphat, \Delta \betat, \Delta \gamma_t ) are the rotational displacements (converted to mm) [34].

DVARS

DVARS indexes the rate of change of the BOLD signal across the entire brain at each frame. The name is an acronym for the temporal Derivative of timecourses, Variance over Root Squared [34]. It is a measure of the overall change in signal intensity from one volume to the next.

Mathematical Definition: DVARS is calculated after motion correction as: [ \text{DVARS}t = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sumi \left[x{i,t} - x{i,t-1}\right]^2} ] where ( N ) is the number of voxels in the brain, and ( x_{i,t} ) is the BOLD signal at voxel ( i ) and timepoint ( t ) [34]. Intensities are often scaled, and the units are typically expressed as percentage BOLD change (( \%\Delta\text{BOLD} )).

Table 1: Core Definitions and Properties of FD and DVARS