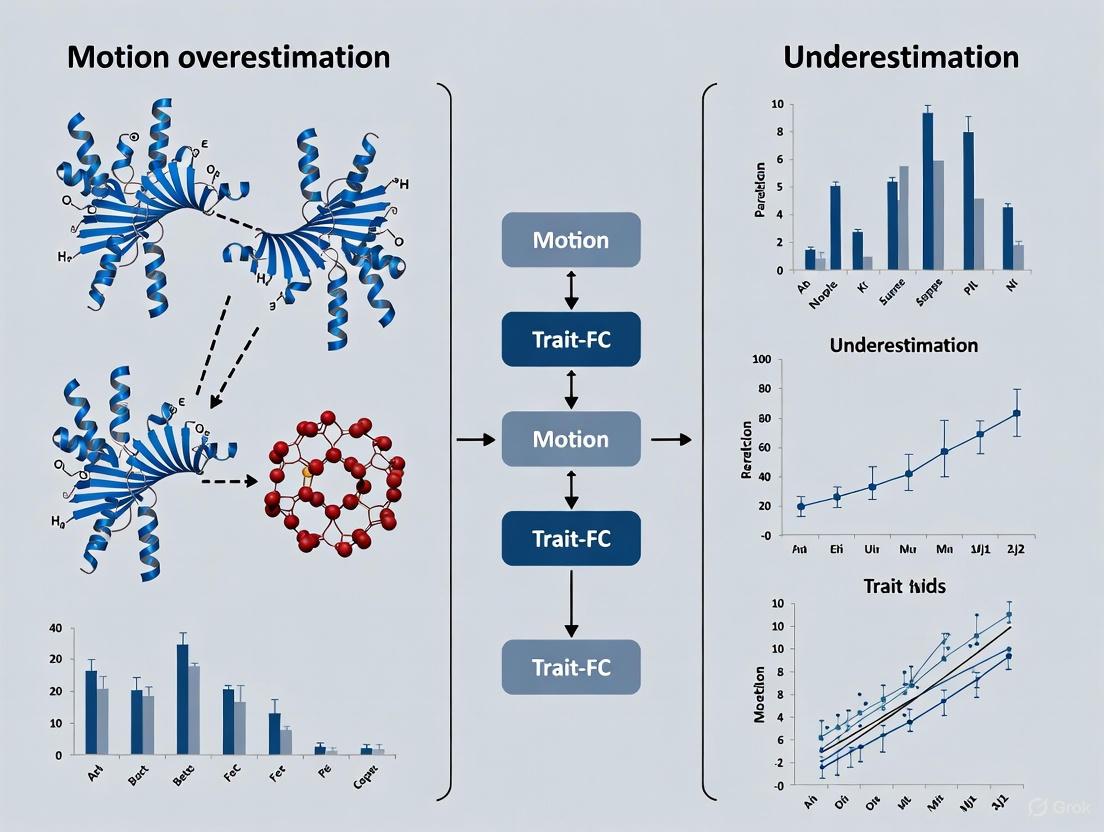

Motion Artifact in fMRI: Distinguishing Overestimation from Underestimation in Trait-FC Effects

In-scanner head motion is a pervasive source of artifact in resting-state functional MRI that can systematically bias trait-functional connectivity (trait-FC) associations, leading to both spurious discoveries and masked true effects.

Motion Artifact in fMRI: Distinguishing Overestimation from Underestimation in Trait-FC Effects

Abstract

In-scanner head motion is a pervasive source of artifact in resting-state functional MRI that can systematically bias trait-functional connectivity (trait-FC) associations, leading to both spurious discoveries and masked true effects. This article synthesizes current research to explore a critical distinction: how residual motion can cause either overestimation or underestimation of true trait-FC relationships. We examine the mechanisms behind these directional biases, with a focus on populations where motion is correlated with the trait of interest, such as in ADHD and autism. The content covers methodological advances for detecting and quantifying motion impact, including the novel SHAMAN framework, and evaluates the efficacy of denoising and censoring strategies. For researchers and clinical trial professionals, we provide actionable guidance on optimizing preprocessing pipelines to mitigate these biases, thereby enhancing the validity of brain-wide association studies and accelerating the development of robust neuroimaging biomarkers.

The Dual Threat: How Motion Artifact Biases Trait-FC Findings

Defining Motion Overestimation and Underestimation in Trait-FC Contexts

In-scanner head motion represents the most substantial source of systematic bias in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, introducing artifacts that persist despite extensive denoising algorithms [1]. This challenge is particularly acute for researchers investigating traits inherently associated with greater movement, such as psychiatric disorders, where failure to account for residual motion artifacts can lead to both false positive and false negative findings [1]. The distinction between motion-induced overestimation and underestimation of trait-functional connectivity (trait-FC) relationships represents a critical methodological frontier in neuroimaging. Without precise tools to quantify these directional biases, investigators risk reporting spurious brain-behavior associations or missing genuine neurobiological relationships obscured by motion-related artifacts [1].

The development of the Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) framework provides researchers with a standardized approach to assign motion impact scores to specific trait-FC relationships, distinguishing between effects where motion causes inflation (overestimation) versus suppression (underestimation) of true effect sizes [1]. This comparative guide evaluates SHAMAN against existing motion correction approaches using data from large-scale studies including the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based recommendations for optimizing trait-FC study designs and analytical pipelines [1].

Motion Impact Mechanisms: Defining Overestimation and Underestimation

Conceptual Framework

Within trait-FC research, motion overestimation occurs when head motion artifact systematically inflates or exaggerates the apparent relationship between a trait and functional connectivity, creating false positive findings [1]. Conversely, motion underestimation arises when motion artifact suppresses or obscures genuine trait-FC relationships, leading to false negative conclusions [1]. The directional nature of these motion impacts stems from the complex interaction between motion-correlated traits and the systematic biases motion introduces to FC metrics [1].

Motion Artifact Effects on Functional Connectivity

Head motion systematically alters resting-state FC patterns in spatially consistent ways, primarily characterized by decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity, with particularly pronounced effects within the default mode network [1]. These motion-induced FC changes create a fundamental confound in trait studies because they correlate with many behavioral and clinical traits of interest [1]. The resulting motion-FC effect matrix demonstrates a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix, meaning participants who move more consistently show weaker connection strengths across brain networks compared to those who move less [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Motion Artifact Effects on Functional Connectivity

| Effect Type | Primary Manifestation | Network Impact | Correlation with Average FC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Motion Effect | Decreased connection strength in high-motion participants | Reduced long-distance connectivity | Strong negative correlation (ρ = -0.58) |

| Spatial Pattern | Distance-dependent correlations | Increased short-range connectivity | Persistent after censoring (ρ = -0.51) |

| Network Specificity | Default mode network vulnerability | Systematic spatial bias | Consistent across denoising approaches |

The SHAMAN Framework: Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Core Principles and Workflow

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) capitalizes on a fundamental physiological observation: traits (e.g., cognitive abilities, clinical symptoms) remain stable over the timescale of an MRI scan, while head motion represents a state that varies second-to-second [1]. This temporal dissociation enables SHAMAN to quantify motion impact by measuring differences in correlation structure between split high-motion and low-motion halves of each participant's fMRI timeseries [1].

The SHAMAN workflow implements the following methodological sequence:

Timeseries Segmentation: For each participant, the resting-state fMRI timeseries is divided into high-motion and low-motion halves based on framewise displacement (FD) metrics.

Connectivity Calculation: Separate FC matrices are computed for the high-motion and low-motion segments.

Trait-FC Effect Comparison: The relationship between trait measures and FC is quantified separately for each motion segment.

Impact Score Computation: Motion impact scores are derived from systematic differences between trait-FC effects in high-motion versus low-motion segments.

Directional Classification: Significant impact scores aligned with the trait-FC effect direction indicate motion overestimation; scores opposite the trait-FC effect indicate motion underestimation.

Statistical Validation: Permutation testing and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections generate significance values for motion impact scores.

Diagram 1: SHAMAN Motion Impact Assessment Workflow

Key Methodological Advantages

SHAMAN provides several critical advantages over previous motion quantification approaches. Unlike methods that require repeated resting-state scans on different days, SHAMAN operates effectively with single scanning sessions [1]. The framework incorporates adaptability for covariate modeling and generates directionally specific impact scores that distinguish between overestimation and underestimation effects [1]. Additionally, SHAMAN establishes statistical thresholds for acceptable versus unacceptable levels of trait-specific motion impact, moving beyond simple motion-FC correlation measures to provide actionable guidance for specific trait-FC relationships under investigation [1].

Comparative Performance: SHAMAN Versus Alternative Motion Correction Approaches

Experimental Design and Dataset

The comparative performance evaluation of motion correction methodologies utilized data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, comprising 11,874 children ages 9-10 years with extensive resting-state fMRI and behavioral data [1]. For primary analyses, n = 7,270 participants with sufficient data quality were included [1]. Researchers assessed 45 diverse traits spanning demographic, biophysical, and behavioral domains to evaluate the prevalence of motion overestimation and underestimation across different motion correction approaches [1].

The experimental protocol compared SHAMAN-derived motion impact scores across three processing conditions:

Standard Denoising Only: Application of ABCD-BIDS preprocessing (global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, motion parameter regression) without motion censoring.

Moderate Censoring: Standard denoising plus censoring of frames with framewise displacement (FD) < 0.2 mm.

Stringent Censoring: Standard denoising plus more aggressive frame removal (FD < 0.1 mm).

Table 2: Motion Impact Prevalence Across Processing Pipelines (n=45 Traits)

| Processing Pipeline | Traits with Significant Overestimation | Traits with Significant Underestimation | Total Traits with Motion Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Denoising Only | 42% (19/45) | 38% (17/45) | 80% (36/45) |

| FD < 0.2 mm Censoring | 2% (1/45) | 38% (17/45) | 40% (18/45) |

| FD < 0.1 mm Censoring | Supplementary analysis required | Supplementary analysis required | Supplementary analysis required |

Performance Findings

The comparative analysis revealed crucial differential effects of motion correction strategies on overestimation versus underestimation. After standard denoising without motion censoring, motion significantly impacted the majority (80%) of trait-FC relationships, with nearly equal distribution between overestimation (42%) and underestimation (38%) effects [1].

Implementing motion censoring at FD < 0.2 mm dramatically reduced significant overestimation to just 2% of traits, demonstrating exceptional efficacy against false positive inflation [1]. However, this same censoring threshold produced no reduction in significant underestimation, which remained at 38% of traits [1]. This asymmetric effect highlights a critical limitation of conventional motion censoring: while effectively controlling false positives, it fails to address motion-induced suppression of genuine trait-FC relationships, potentially exacerbating false negative rates in studies of motion-correlated traits.

Comparison with Alternative Methods

SHAMAN addresses several limitations present in previous motion impact assessment approaches. Unlike distance-dependent correlation analysis, SHAMAN provides trait-specific impact scores rather than global motion-FC similarity metrics [1]. Compared to matched-group designs, SHAMAN operates within participants, eliminating between-group matching challenges [1]. Relative to Siegel et al.'s original method, SHAMAN eliminates the requirement for repeated scanning sessions and incorporates directional impact classification [1].

Diagram 2: Motion Impact Pathways and Intervention Effects

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAMAN Framework | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact | Post-processing analysis | Directional impact scores (over/underestimation), Single-session application |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | Comprehensive denoising | fMRI preprocessing | Global signal regression, Respiratory filtering, Motion parameter regression |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies head motion between volumes | Motion quantification | Composite metric (rotation + translation), Censoring threshold specification |

| Motion Censoring | Removes high-motion frames | Data quality control | Reduces overestimation bias, Framewise exclusion |

| ABCD Dataset | Large-scale developmental neuroimaging | Data source | n=11,874 participants, 45+ traits, Multi-site standardization |

The distinction between motion overestimation and underestimation represents a fundamental advancement in understanding how head motion artifacts influence trait-FC research. The SHAMAN framework provides researchers with a critical tool for quantifying these directional impacts, addressing a significant limitation of conventional motion correction approaches that treat all motion effects as uniform [1].

The empirical evidence demonstrates that standard denoising alone fails to eliminate motion impact for most traits (80%), with nearly equal distribution between overestimation and underestimation effects [1]. While motion censoring at conventional thresholds (FD < 0.2 mm) effectively controls false positives by reducing overestimation to minimal levels (2%), it leaves false negative rates unchanged, failing to address underestimation bias [1]. This finding has profound implications for trait-FC study design, particularly for investigations of clinical populations with inherently higher motion, where underestimation may systematically suppress detection of genuine neurobiological relationships.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings recommend a tiered analytical approach: (1) implementation of rigorous denoising pipelines, (2) application of appropriate motion censoring to control false positives, and (3) routine application of SHAMAN or similar frameworks to quantify residual underestimation bias in traits of interest. This comprehensive strategy moves the field beyond binary motion "correction" toward precise characterization of how motion impacts specific trait-FC relationships, enabling more accurate interpretation of neurobehavioral associations and more targeted therapeutic development.

A fundamental challenge in neuroscience is the contamination of neural signals by motion artifacts. These artifacts systematically bias research findings by either mimicking genuine brain activity, leading to false positive results (overestimation), or obscuring true neural signals, leading to false negative results (underestimation). This guide examines the sources and impacts of these artifacts across major neuroimaging and neuromodulation techniques, comparing the performance of different correction strategies.

Motion artifacts introduce systematic errors that can compromise the validity of neuroimaging and neuromodulation studies. In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), even small, involuntary head movements on the order of millimeters can cause substantial signal changes, altering measured functional connectivity between brain regions. Similarly, in techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), motion can generate electrical signals or hemodynamic responses that closely resemble neurobiological activity. The central problem is twofold: motion can create spurious signals that mimic true neural effects, or it can mask and suppress genuine neural signals, with overestimation and underestimation biases presenting distinct methodological challenges.

The severity of this problem is particularly pronounced when studying clinical populations or traits naturally associated with increased movement, such as psychiatric disorders, neurodevelopmental conditions, or pediatric populations. Understanding the mechanisms, biases, and state-of-the-art correction methods is therefore essential for generating reliable neuroscientific findings and advancing drug development research.

Experimental Evidence of Mimicry and Masking

Evidence from Transcranial Focused Ultrasound

Research on low-intensity transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation (tFUS) has revealed that mechanical artifacts can precisely mimic biologically evoked responses. In experimental models, researchers observed a strong, stereotyped local field potential response time-locked to sonication onset and offset that closely resembled sensory-evoked potentials.

Table 1: Motion Artifact Characteristics in Transcranial Focused Ultrasound

| Experimental Condition | Artifact Characteristics | Neural Mimicry Evidence | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthetized Rat Hippocampus | Stereotyped LFP response time-locked to sonication | Resembled sensory-evoked potentials | Same waveform persisted in euthanized animals, confirming non-biological origin |

| Silicon Microelectrodes | Artifact scaled with acoustic intensity | Most pronounced under continuous-wave sonication | Electrode movement generated artifactual LFP signals |

Critically, the same waveform was observed in euthanized animals, confirming a non-biological, artifact-driven origin [2]. These findings underscore the risk of misinterpreting motion-related artifacts as genuine neural responses, particularly in techniques involving mechanical energy transmission.

Evidence from Functional MRI

In-scanner head motion introduces systematic bias to resting-state fMRI functional connectivity that isn't completely removed by standard denoising algorithms. Research using the Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) method has quantified how motion impacts specific trait-FC relationships.

Table 2: Motion Impact on Brain-Behavior Associations in fMRI (n=7,270 participants)

| Analysis Condition | Traits with Significant Overestimation | Traits with Significant Underestimation | Effect on Trait-FC Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| After Standard Denoising (No Censoring) | 42% (19/45 traits) | 38% (17/45 traits) | Widespread inflation and suppression of effects |

| After Censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) | 2% (1/45 traits) | 38% (17/45 traits) | Reduced overestimation but persistent underestimation |

After standard denoising without motion censoring, 42% of traits showed significant motion overestimation scores while 38% showed significant underestimation scores. Censoring at framewise displacement < 0.2 mm reduced significant overestimation to just 2% of traits but did not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores [1] [3] [4]. This demonstrates that standard motion correction approaches may reduce one type of bias while perpetuating another.

Methodological Protocols for Motion Impact Assessment

The SHAMAN Framework for fMRI

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) methodology was developed to assign a motion impact score to specific trait-functional connectivity relationships. This approach distinguishes between motion causing overestimation or underestimation of trait-FC effects through several key steps:

Data Acquisition: Utilizing large-scale datasets like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study with up to 20 minutes of rs-fMRI data on 11,874 children ages 9-10 years.

Denoising Application: Implementing standard denoising algorithms (e.g., ABCD-BIDS) including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter timeseries regression.

Split-Half Analysis: Capitalizing on the observation that traits are stable over the timescale of an MRI scan while motion varies second-to-second. The method measures differences in correlation structure between split high- and low-motion halves of each participant's fMRI timeseries.

Impact Scoring: A direction (positive or negative) of the motion impact score aligned with the trait-FC effect indicates motion causing overestimation, while a score opposite the trait-FC effect indicates motion causing underestimation.

Statistical Validation: Permutation of the timeseries and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections yields a motion impact score with p-value distinguishing significant from non-significant motion impacts [1].

Motion-Net for EEG Artifact Removal

For mobile EEG applications, the Motion-Net deep learning framework provides a subject-specific approach to motion artifact removal:

Experimental Design: Subjects perform controlled movements while EEG and accelerometer data are synchronously recorded.

Data Preprocessing: Cutting data according to experiment triggers, resampling, synchronization testing by comparing motion artifact amplitude peak locations in EEG and accelerometer signals, and baseline correction.

Feature Extraction: Incorporating visibility graph features that provide structural information about EEG signals, enhancing model performance with smaller datasets.

Model Architecture: Implementing a U-Net-based convolutional neural network trained separately for each subject using real EEG recordings with ground-truth references.

Performance Validation: Achieving an average motion artifact reduction percentage of 86% ±4.13, SNR improvement of 20 ±4.47 dB, and Mean Absolute Error of 0.20 ±0.16 across experimental setups [5].

Comparative Analysis of Motion Artifact Challenges Across Techniques

Different neuroimaging modalities face distinct motion artifact challenges and require specialized correction approaches.

Table 3: Motion Artifact Profiles Across Neuroimaging Modalities

| Technique | Primary Motion Artifact Mechanisms | Mimicry Risks | Masking Risks | Optimal Correction Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Head movement alters magnetic field uniformity; causes spin history effects | Spurious functional connectivity; false brain-behavior correlations | Underestimation of long-distance connectivity | SHAMAN; stringent censoring (FD < 0.2 mm); combination pipelines |

| EEG | Electrode movement, cable motion, muscle artifacts | Mimics epileptic spikes, evoked potentials | Obscures genuine brain oscillations | Motion-Net; visibility graph features; subject-specific approaches |

| fNIRS | Head movement disrupts optode-scalp coupling | Creates hemodynamic-like responses | Reduces signal-to-noise ratio | Computer vision tracking; movement categorization by axis/speed |

| Simultaneous EEG-fMRI | Conductive path movement in static magnetic field | Creates spurious EEG-fMRI correlations | Obscures true neurovascular coupling | Reference layer artifact subtraction; motion parameter regression |

Each technique shows varying susceptibility to different motion types. For example, in fNIRS, upward and downward movements particularly compromise signal quality in occipital regions, while temporal regions are most affected by lateral movements [6]. In simultaneous EEG-fMRI, head shaking produces more challenging artifacts compared to head nodding due to non-rigid body movement of the skull and skin [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for Motion Artifact Management

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAMAN Framework | Quantifies motion overestimation/underestimation | Resting-state fMRI | Trait-specific impact scores; distinguishes direction of bias |

| Motion-Net | Deep learning artifact removal | Mobile EEG | Subject-specific approach; 86% artifact reduction |

| Visibility Graph Features | Extracts structural signal properties | EEG preprocessing | Enhances model accuracy with smaller datasets |

| Computer Vision Tracking | Quantifies head movement parameters | fNIRS studies | Provides ground-truth movement data for validation |

| Reference Layer Systems | Measures motion artifacts directly | EEG-fMRI environments | Electrically isolated reference signals |

| Framewise Displacement | Quantifies head movement between volumes | fMRI quality control | Standardized metric for censoring decisions |

| ICA-AROMA | Identifies motion-related components | fMRI preprocessing | Automatic removal of motion artifacts |

Visualization of Motion Artifact Pathways and Methodologies

Motion Artifact Generation in Neuroimaging

SHAMAN Analytical Workflow

Motion artifacts present a complex challenge in neuroscience research, with the potential to both mimic and mask genuine neural signals. The evidence demonstrates that different correction strategies carry trade-offs between reducing overestimation versus underestimation biases. While stringent motion censoring effectively reduces false positive findings, it may perpetuate false negatives and limit generalizability by systematically excluding participants with higher motion. Emerging techniques like SHAMAN for fMRI and Motion-Net for EEG represent significant advances in quantifying and addressing these biases. For researchers in neuroscience and drug development, implementing multimodal motion assessment, applying trait-specific impact analyses, and transparently reporting motion management strategies are essential for producing valid, reproducible findings.

Functional connectivity (FC) research, particularly in resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), has become a cornerstone for investigating brain organization in neurodevelopmental conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, head motion during scanning introduces systematic bias that can create spurious brain-behavior associations, potentially compromising findings in these clinically relevant populations. This methodological challenge is particularly acute when studying traits inherently correlated with motion, such as symptoms of ADHD and autism [1].

The motion-trait conundrum represents a critical methodological challenge: individuals with ADHD and autism often exhibit greater in-scanner head motion [1], meaning that the very populations of interest are those most likely to produce data contaminated by motion artifacts. Even with standard denoising algorithms, residual motion artifact persists and can systematically alter observed trait-FC relationships. Research indicates that motion artifacts can cause both overestimation and underestimation of true trait-FC effects, potentially leading to false positive and false negative results in brain-wide association studies (BWAS) [1].

Understanding and addressing this confound is essential for advancing robust, reproducible research on neurodevelopmental conditions. This guide compares current approaches for detecting and mitigating motion-related artifacts, with particular emphasis on populations at risk for motion-correlated traits.

Quantitative Comparison of Motion Artifact Impact

Prevalence of Motion Impact on Behavioral Traits

Table 1: Impact of Residual Head Motion on Trait-FC Relationships in the ABCD Study (n=7,270)

| Analysis Condition | Traits with Significant Motion Overestimation | Traits with Significant Motion Underestimation | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| After standard denoising (ABCD-BIDS) | 42% (19/45 traits) | 38% (17/45 traits) | Majority of traits showed significant motion impact despite denoising |

| After censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) | 2% (1/45 traits) | 38% (17/45 traits) | Censoring reduced overestimation but did not address underestimation |

Data derived from SHAMAN methodology application to the ABCD Study dataset, assessing 45 behavioral traits [1].

Cognitive Profiles in ADHD and Autism

Table 2: Cognitive Profiles on Wechsler Intelligence Tests (WAIS-IV/WISC-V) in Autism and ADHD

| Cognitive Domain | Autism Profile | ADHD Profile | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Comprehension | Typical performance (~100) | Age-expected levels | Relative strength in autism |

| Perceptual Reasoning | Typical performance (~100) | Age-expected levels | Relative strength in autism |

| Working Memory | Slightly reduced (~90) | Slightly reduced (~95) | Area of difficulty for both conditions |

| Processing Speed | Significantly reduced (~85) | Age-expected levels | Distinctive weakness in autism |

| Full-Scale IQ | Within typical range | Within typical range | Profiles not sufficient for diagnosis |

Meta-analysis of over 1,800 neurodivergent participants from 18 data sources; standardized scores shown where average population performance = 100 [8].

Experimental Protocols for Motion Impact Assessment

The SHAMAN Framework: Split-Half Analysis of Motion-Associated Networks

The Split-Half Analysis of Motion-Associated Networks (SHAMAN) methodology was developed specifically to quantify trait-specific motion artifact in functional connectivity studies [1]. This approach addresses key limitations of previous methods by operating on one or more rs-fMRI scans per participant and accommodating covariates in statistical models.

Experimental Workflow:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Collect resting-state fMRI data with associated framewise displacement (FD) calculations. Apply standard denoising pipelines (e.g., ABCD-BIDS processing including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter timeseries regression) [1].

Split-Half Partitioning: For each participant, separate the fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on framewise displacement values.

Trait-FC Effect Calculation: Compute correlation structures between the trait of interest and functional connectivity measures separately for each motion half.

Motion Impact Score Calculation: Compare the difference in trait-FC correlation structure between high-motion and low-motion halves. The significance of this difference is assessed through permutation testing of the timeseries and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections.

Directional Interpretation:

- A motion overestimation score is assigned when the direction of the motion impact score aligns with the direction of the trait-FC effect.

- A motion underestimation score is assigned when the motion impact score direction opposes the trait-FC effect.

Validation: Apply censoring at various FD thresholds (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) to evaluate reduction in motion impact scores.

Figure 1: SHAMAN Experimental Workflow for Quantifying Motion Impact

Comparative Diagnostic Assessment for ADHD and Autism

Accurate differential diagnosis is essential for disentangling the motion-trait conundrum, particularly given the high co-occurrence of ADHD and autism [9]. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive assessment approach:

Clinical Assessment Protocol:

Multi-Method Data Collection:

- Parental Interviews: Structured diagnostic interviews (e.g., Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised) focusing on early developmental history and current symptoms.

- Rating Scales: Standardized behavior checklists for both autism (e.g., Social Communication Questionnaire) and ADHD (e.g., Conners' Rating Scales) symptoms.

- Behavioral Observations: Direct observation using standardized protocols (e.g., Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) across different contexts.

- Cognitive Testing: Comprehensive neuropsychological assessment including Wechsler Intelligence Scales to identify cognitive profiles [8].

Subtype Differentiation: Specifically assess for ADHD presentations (predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, or combined) within autistic individuals [9].

Longitudinal Follow-up: Implement ongoing assessment across development, as symptoms may change presentation over time, particularly from childhood to adolescence [9].

Molecular Pathways and Research Models

Signaling Pathways in Neurodevelopmental Conditions

Research using animal models has identified several molecular pathways relevant to ADHD and autism pathophysiology. The diagram below illustrates key pathways implicated in these conditions, particularly focusing on synaptic function.

Figure 2: Molecular Pathways in ADHD and Autism Pathophysiology

Key Pathway Insights:

Dopamine Dysregulation in ADHD: DAT knockout (DAT-KO) mouse models demonstrate a five-fold increase in extracellular dopamine concentration, reduced dopamine release, and approximately 50% downregulation of postsynaptic D1 and D2 receptors in the striatum [10]. These alterations lead to hyperlocomotion, deficits in attention, and poor learning and memory - core features relevant to ADHD.

Synaptic Dysfunction in Autism: SH3RF3 deficiency disrupts the formation of a molecular complex between BRSK1/SAD-B kinase and the ASD-associated active zone protein RIM1, leading to reduced RIM1 phosphorylation. This perturbation substantially reduces synaptic vesicle density and readily releasable pool size, coupled with delayed synaptic vesicle replenishment kinetics. These deficits ultimately impair excitatory synaptic transmission in the prefrontal cortex and disturb excitatory-inhibitory (E/I) balance [11].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Motion-Trait Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denoising Algorithms | ABCD-BIDS pipeline, FIX, Global Signal Regression | Removes motion-related variance from fMRI data | Residual motion artifact persists; may not eliminate trait-specific motion effects |

| Motion Censoring Methods | Framewise displacement (FD) thresholding (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) | Excludes high-motion fMRI frames from analysis | Reduces overestimation but may not address underestimation; can bias sample distribution |

| Motion Impact Quantification | SHAMAN framework | Assigns motion impact scores to specific trait-FC relationships | Distinguishes between overestimation and underestimation effects; adaptable to covariates |

| Animal Models | DAT-KO mice, SH3RF3-KO mice, Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR) | Studies molecular mechanisms and tests interventions | Recapitulate specific behavioral features but may not model full complexity of human disorders |

| Stem Cell Models | iPSC-derived neurons, 3D organoids, assembloids | Studies human-specific features of neurodevelopment | Captures patient-specific genetics; useful for personalized therapeutic screening |

| Behavioral Assessments | Open field test, Marble burying, Social interaction tests | Quantifies behavioral phenotypes in animal models | Provides face validity for neurodevelopmental condition features |

The motion-trait conundrum presents a significant methodological challenge for researchers studying ADHD, autism, and other neurodevelopmental conditions. Current evidence suggests that standard denoising approaches substantially reduce but do not eliminate motion-related artifacts in functional connectivity analyses. The development of specialized methods like the SHAMAN framework represents important progress in quantifying and addressing trait-specific motion impacts.

For populations at risk of motion-correlated traits, particularly individuals with ADHD and autism, researchers must implement comprehensive strategies that include robust motion quantification, careful diagnostic characterization, and appropriate analytical corrections. Future research should continue to refine these methodological approaches to ensure that observed brain-behavior relationships reflect genuine neurobiological mechanisms rather than motion-related artifacts, ultimately advancing our understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions and supporting the development of more effective interventions.

The Spatiotemporal Signature of Motion on Functional Connectivity

Functional connectivity (FC), measured as the temporal synchronization of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal fluctuations across different brain regions, has become a fundamental tool for exploring brain network organization [12]. However, the spatiotemporal signature of in-scanner head motion introduces systematic biases that can profoundly alter FC estimates and lead to spurious scientific conclusions [1] [13]. This confound is particularly problematic in studies investigating traits associated with motion, such as psychiatric disorders, developmental conditions, and aging, where motion systematically correlates with the variables of interest [1] [13]. Understanding the dual nature of motion artifacts—capable of both overestimating and underestimating trait-FC relationships—has become essential for proper interpretation of functional connectivity findings.

The spatial signature of motion artifacts exhibits consistent patterns: motion typically decreases long-distance connectivity while increasing short-range connectivity, most notably in default mode and frontoparietal control networks [1] [14]. Temporally, motion induces both immediate, large-amplitude signal changes and longer-duration artifacts that may persist for 8-10 seconds [13]. These spatiotemporal characteristics vary across individuals and populations, making motion correction particularly challenging in clinical and developmental populations where motion is often elevated [1]. This review systematically examines the spatiotemporal signature of motion on FC, compares methodological approaches for quantifying and mitigating these artifacts, and provides practical guidance for researchers investigating trait-FC relationships.

Motion Overestimation vs. Underestimation in Trait-FC Effects

The Dual Nature of Motion Artifacts

Head motion systematically biases trait-FC relationships in two distinct directions: overestimation and underestimation of true effects [1]. The direction of bias depends on the alignment between motion-FC effects and trait-FC effects. When the spatial pattern of motion-related FC changes aligns with the trait-FC effect direction, motion causes overestimation; when these patterns oppose each other, motion causes underestimation of the true relationship [1]. This distinction is critical because these two types of bias require different mitigation strategies, and standard denoising approaches may reduce one type while potentially exacerbating the other.

Recent large-scale studies reveal how prevalent both types of bias are in practice. In an analysis of 45 traits from n=7,270 participants in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, 42% (19/45) of traits exhibited significant motion overestimation scores while 38% (17/45) showed significant underestimation scores after standard denoising [1]. This nearly equal distribution highlights that motion artifacts are not unidirectional and cannot be addressed with a one-size-fits-all approach.

The SHAMAN Method for Quantifying Motion Impact

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) method was developed to quantitatively distinguish between motion overestimation and underestimation effects on specific trait-FC relationships [1]. SHAMAN capitalizes on the fundamental observation that traits (e.g., cognitive abilities, clinical diagnoses) are stable over the timescale of an MRI scan, whereas motion is a state that varies from second to second [1].

The method operates by:

- Splitting each participant's fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves

- Measuring differences in correlation structure between these halves

- Comparing the direction of motion impact scores with the direction of trait-FC effects

- Using permutation testing and non-parametric combining to generate statistically significant motion impact scores [1]

A motion impact score aligned with the trait-FC effect direction indicates overestimation, while a score opposite to the trait-FC effect indicates underestimation [1]. This methodological innovation provides researchers with a specific tool to evaluate whether their trait-of-interest is vulnerable to motion-related bias.

Table 1: SHAMAN Motion Impact Score Interpretation

| Motion Impact Score | Relationship to Trait-FC Effect | Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive and significant | Aligned with trait-FC effect | Motion causes overestimation | Apply stricter motion censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) |

| Negative and significant | Opposite to trait-FC effect | Motion causes underestimation | Avoid aggressive censoring that may exacerbate bias |

| Not significant | No systematic relationship | Minimal motion impact | Standard processing sufficient |

Differential Effectiveness of Mitigation Strategies

The SHAMAN method reveals that standard motion correction approaches differentially address overestimation versus underestimation biases. In the ABCD study, motion censoring at framewise displacement (FD) < 0.2 mm dramatically reduced significant overestimation from 42% to just 2% of traits [1]. However, this same censoring threshold did not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores [1]. This finding has profound implications for analytical choices—while aggressive censoring may effectively control false positives from motion overestimation, it does not resolve underestimation biases and may even exacerbate them by selectively removing data from high-motion individuals who often represent important clinical populations.

Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

Spatial Signatures of Motion in FC

The spatial distribution of motion artifacts in functional connectivity follows systematic patterns that reflect both the biomechanics of head movement and the physics of MRI signal acquisition:

Distance-dependent effects: Motion produces characteristic decreases in long-distance connectivity and increases in short-range connectivity [1] [14]. This pattern emerges because motion artifacts introduce spatially correlated signal changes that diminish with distance from the movement source.

Network-specific vulnerability: The default mode network (DMN) and frontoparietal control networks show particularly pronounced motion-related decreases in functional coupling [14]. These networks, characterized by distributed regions of association cortex, appear most vulnerable to motion-induced signal loss.

Regional susceptibility: Motion is biomechanically constrained by the neck, resulting in minimal movement near the atlas vertebrae (where the skull attaches) and increasing motion with distance from this anchor point [13]. Frontal cortex shows particularly high motion susceptibility, likely due to the prevalence of y-axis rotation (nodding movement) [13].

Apparent connectivity increases: While motion typically decreases most connections, it can spuriously increase certain network measures, including local functional coupling and connectivity between homotopic motor regions [14]. These artifactual "increases" can be particularly misleading when interpreting group differences.

Table 2: Spatial Patterns of Motion Artifacts in Functional Connectivity

| Spatial Pattern | Affected Brain Networks/Regions | Direction of Effect | Potential Misinterpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-dependent correlation | Long-distance connections | Decreased connectivity | Misinterpreting motion-related reduction as neuronal decoupling |

| Short-range overestimation | Local, neighboring regions | Increased connectivity | False positive local hyperconnectivity |

| Default network vulnerability | DMN, frontoparietal networks | Marked decrease | Mistaking motion artifact for DMN dysfunction in clinical populations |

| Motor network changes | Bilateral motor regions | Increased interhemispheric coupling | Using motor connectivity as reference despite motion susceptibility |

Temporal Signatures of Motion in FC

The temporal characteristics of motion artifacts manifest across multiple timescales and present distinct challenges for FC analysis:

Immediate signal disruptions: Motion produces large-amplitude, temporally circumscribed signal changes that are maximal at the volume acquired immediately after an observed movement [13]. These abrupt signal changes scale with motion magnitude and represent the most easily identifiable motion artifacts.

Prolonged signal alterations: In addition to immediate disruptions, motion can induce longer-duration artifacts lasting 8-10 seconds [13]. The origin of these prolonged artifacts remains incompletely understood but may involve motion-related changes in CO2 from yawning or deep breathing, or slow equilibration of signal disruptions following large movements [13].

Spin-history effects: Nonlinear persistence of motion artifacts can occur due to spin excitation history effects that continue for some time after movement cessation [13]. These effects create complex temporal dependencies that simple regression approaches may not fully capture.

Frequency-specific contamination: While traditional band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) targets the frequency range of neural BOLD fluctuations, motion artifacts contaminate this frequency band and cannot be effectively removed by standard filtering alone [13].

Methodological Comparisons for Motion Mitigation

FC Estimation Methods and Motion Sensitivity

The choice of functional connectivity metric significantly influences sensitivity to motion artifacts. Different FC measures exhibit varying resilience to motion contamination:

Table 3: Motion Sensitivity Across Functional Connectivity Measures

| FC Method | Sensitivity to Motion | Test-Retest Reliability | Fingerprinting Accuracy | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full correlation | High residual distance-dependent motion relationship | High | High | Studies with low-motion participants where reliability is prioritized |

| Partial correlation | Low sensitivity to motion artifact | Intermediate | Low | Motion-prone populations when system identifiability is key |

| Coherence-based measures | Low sensitivity | Variable | Variable | Supplemental analysis to confirm correlation-based findings |

| Information theory measures | Low sensitivity | Variable | Variable | Exploring non-linear connectivity resistant to motion |

A systematic evaluation of eight FC measures revealed that full correlation maintains high test-retest reliability and fingerprinting accuracy but shows relatively high residual distance-dependent relationships with motion, even after rigorous mitigation [15]. Partial correlation offers the best of both worlds with low motion sensitivity and intermediate system identifiability, though with lower test-retest reliability and fingerprinting accuracy [15]. Importantly, certain networks—particularly the default mode and retrosplenial temporal sub-networks—show high motion correlation across all FC methods, indicating their particular vulnerability [15].

Motion Mitigation Pipelines and Performance

Various preprocessing strategies have been developed to address motion artifacts, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

Global Signal Regression (GSR): This controversial approach effectively reduces distance-dependent motion artifacts but may introduce artificial negative correlations and remove neural signals of interest [13]. The decision to use GSR involves trade-offs between motion mitigation and signal preservation.

Motion Censoring ("Scrubbing"): Removing high-motion volumes (typically FD > 0.2-0.5 mm) reduces motion-related artifacts but can introduce biases by disproportionately excluding data from high-motion participants, who often represent clinically interesting populations [1] [13]. Censoring effectively addresses overestimation biases but shows limited efficacy for underestimation biases [1].

Physiological Noise Modeling: Incorporating cardiac and respiratory measures can address physiological sources of motion artifact [12] [1]. The ABCD-BIDS pipeline, which includes respiratory filtering, reduces motion-related variance by approximately 69% compared to minimal processing alone [1].

Multi-echo Sequences: Advanced acquisition techniques using multiple echo times can help distinguish motion-related from neural signals but require specialized sequences not universally available [1].

Diagram 1: Spatiotemporal pathways of motion artifacts leading to overestimation and underestimation biases in trait-FC research. Motion induces distinct temporal artifacts that manifest as specific spatial patterns in functional connectivity, ultimately producing systematic biases that can either exaggerate or mask true trait-FC relationships.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Impact Assessment

SHAMAN Implementation Protocol

The SHAMAN methodology provides a standardized approach for quantifying motion impact on specific trait-FC relationships:

Data Requirements: One or more resting-state fMRI scans per participant with framewise displacement (FD) calculations for each volume. Trait measures should be stable over the scanning timeframe.

Timeseries Splitting: For each participant, split the preprocessed BOLD timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on median FD split within subject.

FC Calculation: Compute separate functional connectivity matrices for high-motion and low-motion halves using the preferred FC metric (e.g., full correlation, partial correlation).

Motion Impact Score Calculation:

- Compute the difference in FC between high-motion and low-motion halves for each connection

- Calculate the spatial correlation between this motion-FC difference and the trait-FC effect

- Use permutation testing (typically 1,000-10,000 permutations) to establish statistical significance

- Apply non-parametric combining across connections to generate overall motion impact scores

Bias Direction Determination:

- Positive significant scores = motion overestimation of trait-FC effect

- Negative significant scores = motion underestimation of trait-FC effect

Validation: Repeat analysis with different motion censoring thresholds to assess robustness of findings [1].

Motion-Robust FC Analysis Protocol

For researchers studying traits potentially correlated with motion, the following comprehensive protocol is recommended:

Data Acquisition:

- Collect physiological recordings (cardiac, respiration) concurrently with fMRI

- Use multi-echo sequences if available

- Implement real-time motion monitoring and feedback

Preprocessing:

- Apply volume-based realignment, generating FD estimates

- Incorporate physiological noise models (e.g., RETROICOR, HRV/RRV)

- Implement aggressive motion censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) for initial analysis

- Compare with minimal censoring (FD < 0.5 mm) to assess robustness

FC Estimation:

- Calculate multiple FC metrics (full correlation, partial correlation)

- Compare results across metrics to identify motion-resistant findings

- For clinical group comparisons, include matched-motion subgroups

Motion Impact Assessment:

- Apply SHAMAN to traits of interest

- Report motion impact scores and significance values

- Acknowledge limitations for traits with significant motion impact

Reporting:

- Document mean FD and exclusion rates for all groups

- Report correlation between motion and trait measures

- Present results with and without motion censoring

- Acknowledge motion impact when interpreting findings

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Motion-Robust FC Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement (FD), DVARS | Quantifies volume-to-volume head movement | Use standardized FD calculation (Jenkinson et al.) for cross-study comparisons |

| Denoising Pipelines | ABCD-BIDS, fMRIPrep, HCP Pipelines | Standardized preprocessing for motion mitigation | ABCD-BIDS includes respiratory filtering and motion regression |

| Motion Impact Assessment | SHAMAN, Distance-Dependent Correlation | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact | SHAMAN distinguishes overestimation vs. underestimation |

| Physiological Monitoring | Cardiac pulse, Respiration belt, CO2 monitoring | Captures physiological sources of motion | Essential for modeling cardiopulmonary artifacts |

| Real-Time Motion Control | FIRMM, FIDUCIAL | Provides immediate motion feedback during scanning | Reduces data loss by alerting to excessive motion |

| FC Metric Suites | Full/partial correlation, Coherence, Mutual information | Multiple connectivity measures with varying motion sensitivity | Using multiple metrics strengthens motion-resistant findings |

| Multivariate Pattern Analysis | MVPA, Pattern classification | Detects subvoxel patterns resistant to motion | Can reveal information not apparent in univariate analyses |

The spatiotemporal signature of motion on functional connectivity represents a fundamental methodological challenge that transcends conventional nuisance regression approaches. The systematic patterns of motion artifacts—with distinct spatial distributions across brain networks and temporal profiles across timescales—can produce both overestimation and underestimation biases in trait-FC relationships. The development of specialized methods like SHAMAN provides researchers with tools to quantify these specific biases, while comparative analyses of FC metrics offer guidance for selecting motion-resistant connectivity measures.

Future advances will require continued refinement of dynamic motion correction methods, improved integration of physiological monitoring, and development of study designs that minimize motion confounds through engaging paradigms. Most importantly, researchers must acknowledge and address motion artifacts as a core analytical consideration rather than a peripheral preprocessing step. By implementing comprehensive motion assessment protocols and transparently reporting motion impact, the field can enhance the validity and reproducibility of functional connectivity research across diverse populations and clinical conditions.

In-scanner head motion is now recognized as a major methodological challenge for studies of functional connectivity (FC), not merely as random noise but as a systematic confound that can produce both spurious positive (overestimation) and negative (underestimation) biases in trait-FC relationships [13] [1]. This confound is particularly problematic because in-scanner motion is frequently correlated with traits of interest such as age, clinical status, cognitive ability, and symptom severity [13]. For example, individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism often exhibit higher in-scanner head motion than neurotypical participants, creating a systematic bias that can generate false positive or negative findings if not adequately addressed [1]. Understanding and mitigating these motion-induced biases is especially crucial for researchers and drug development professionals employing brain-wide association studies (BWAS) to identify meaningful brain-behavior relationships, as motion artifacts can substantially alter inference in studies of lifespan development, individual differences, and clinical populations [13] [1].

The spatial and temporal characteristics of motion artifacts are well-documented. Motion typically decreases long-distance connectivity while increasing short-range connectivity, most notably in the default mode network [1]. These effects occur because motion causes signal decrements across the entire brain parenchyma simultaneous with large signal increases at brain boundaries due to partial volume effects [13]. The temporal signature includes both brief, large-amplitude signal changes immediately following movement and longer-duration artifacts potentially lasting 8-10 seconds, which may result from motion-related physiological changes or interactions between motion direction and image phase encoding [13].

Quantitative Comparison of Denoising Strategies and Their Efficacy

Performance Benchmarks for Confound Regression Strategies

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Major Denoising Approaches for Motion Artifact Reduction

| Denoising Method | Residual Motion-FC Relationship | Distance-Dependence Artifacts | Network Identifiability | Data Retention | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Signal Regression (GSR) | Minimal | Introduces distance-dependent artifacts | Moderate | High | Can introduce negative correlations; controversial biological interpretation [16] |

| Motion Censoring ("Scrubbing") | Significantly reduced | Mitigates distance-dependence | High | Lower (data loss) | Reduces usable data; potential exclusion of high-motion participants [1] [17] |

| Motion Parameter Regression | Moderate reduction | Limited effect on distance-dependence | Moderate | High | Ineffective for nonlinear motion effects; incomplete artifact removal [13] [17] |

| Low-Pass Filtering | Partial reduction | Variable impact | Moderate | High | May remove neural signals along with artifacts [13] |

| Combined GSR + Censoring | Minimal | Mitigates distance-dependence | High | Moderate | Optimal balance for many applications [18] |

Trait-Specific Motion Impact Across Methods

Table 2: Motion Impact on Specific Traits After Different Denoising Approaches (ABCD Study, n=7,270)

| Trait Category | Significant Motion Overestimation (Minimal Processing) | Significant Motion Underestimation (Minimal Processing) | Motion Overestimation (FD < 0.2 mm Censoring) | Motion Underestimation (FD < 0.2 mm Censoring) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive/Educational | 42% (19/45 traits) | 38% (17/45 traits) | 2% (1/45 traits) | No reduction |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | High susceptibility | High susceptibility | Substantially reduced | Persistent |

| Physical Metrics | Moderate susceptibility | Moderate susceptibility | Minimal | Persistent |

| Demographic Factors | Variable | Variable | Minimal | Variable |

Recent research using the Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) method has quantified how motion specifically impacts trait-FC relationships. In the large-scale Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, after standard denoising without motion censoring, 42% of examined traits showed significant motion overestimation scores, while 38% showed significant underestimation scores [1]. After stringent motion censoring at framewise displacement (FD) < 0.2 mm, significant overestimation was reduced to just 2% of traits, but the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores was not decreased [1]. This demonstrates the complex and persistent nature of motion artifacts, where different denoising strategies may mitigate one type of bias while potentially exacerbating another.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Impact Assessment

The SHAMAN Methodology for Trait-Specific Motion Quantification

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) represents a novel approach for computing a trait-specific motion impact score that operates on one or more resting-state fMRI scans per participant [1]. The methodology capitalizes on the observation that traits (e.g., weight, intelligence) are stable over the timescale of an MRI scan, whereas motion is a state that varies from second to second [1]. The experimental protocol proceeds as follows:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Acquire resting-state fMRI data using standardized protocols (e.g., 6-20 minutes of resting-state data). Apply minimal preprocessing including motion correction through frame realignment. The ABCD-BIDS default denoising algorithm includes global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and regressing out motion parameter timeseries [1].

Framewise Displacement Calculation: Compute framewise displacement (FD) using the formula derived from Power et al. [13], which summarizes the frame-to-frame changes in the six motion parameters (three translations, three rotations).

Time-Series Splitting: For each participant, split the fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on median FD values.

Trait-FC Effect Calculation: Compute the correlation between the trait and functional connectivity in both the high-motion and low-motion halves.

Motion Impact Score Determination: Calculate the difference in trait-FC effects between the high-motion and low-motion halves. A significant difference indicates that motion impacts the trait-FC relationship.

Directionality Assessment: A motion impact score aligned with the direction of the trait-FC effect indicates motion overestimation (inflated effect). A score opposite the trait-FC effect indicates motion underestimation (deflated effect) [1].

Statistical Significance Testing: Use permutation testing and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections to generate a p-value distinguishing significant from non-significant motion impacts.

Benchmarking Protocol for Denoising Pipelines

Ciric et al. [16] established a systematic protocol for evaluating participant-level denoising pipelines according to four key benchmarks:

Residual Motion-FC Relationship: Quantify the correlation between mean FD and connectivity after denoising, with better pipelines showing smaller correlations.

Distance-Dependence of Motion Effects: Evaluate whether motion artifacts exhibit the characteristic distance-dependent pattern (increased short-range connectivity, decreased long-range connectivity).

Network Identifiability: Assess the ability to recover known functional network modules from the denoised connectome data.

Degrees of Freedom Lost: Account for the statistical cost of each denoising method, as more aggressive approaches may remove meaningful neural variance along with artifacts [16].

This benchmarking approach enables objective comparison of denoising strategies and facilitates selection of appropriate methods for specific research goals.

Visualization of Motion Confounding Mechanisms and Analytical Approaches

The Mechanism of Motion Confounding in Trait-FC Studies

(Diagram 1: Motion as a confounder in trait-FC studies. Motion creates artifacts in FC measures that can either mask or inflate true trait-FC relationships, particularly when genetic factors influence both motion and the trait of interest.)

The SHAMAN Analytical Workflow for Motion Impact Assessment

(Diagram 2: The SHAMAN analytical workflow for quantifying trait-specific motion impact. This method capitalizes on the stability of traits versus the state-dependent nature of motion to identify spurious associations.)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Tools and Methods for Motion Confound Management in Trait-FC Research

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies volume-to-volume head motion | Multiple calculation methods exist (Power vs. Jenkinson); affects threshold selection [13] |

| fMRIPrep | Standardized fMRI preprocessing pipeline | Provides robust, reproducible preprocessing; minimizes manual intervention [19] |

| SHAMAN Analysis | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact | Requires sufficient scan duration for split-half analysis; adaptable to covariates [1] |

| Global Signal Regression (GSR) | Removes global motion-related variance | Controversial due to potential introduction of negative correlations; use judiciously [16] |

| Motion Censoring ("Scrubbing") | Removes high-motion volumes from analysis | Balance between artifact reduction and data retention; FD threshold typically 0.2-0.5mm [1] [17] |

| Low-Pass Filtering of Motion Parameters | Reduces high-frequency respiration contamination | Particularly beneficial in single-band fMRI datasets; improves FD accuracy [18] |

| ANTs/FSL | Image registration and normalization | Critical for accurate spatial alignment; choice affects motion correction efficacy [19] |

| Ciric Benchmarking Framework | Evaluates denoising pipeline performance | Assesses four key benchmarks: residual motion, distance-dependence, network identifiability, and degrees of freedom [16] |

Motion artifact in trait-FC research represents a complex challenge that extends beyond simple noise to include systematic confounding that can either inflate or deflate observed brain-behavior relationships [1]. The most effective approaches combine multiple denoising strategies, typically including global signal regression with selective motion censoring, while acknowledging that no method completely eliminates motion-related bias [16] [18]. The development of trait-specific motion impact assessment tools like SHAMAN represents a significant advance, enabling researchers to quantify and account for motion artifacts in their specific research context [1]. As large-scale brain-wide association studies continue to grow, implementing robust, transparent methods for motion management will be essential for generating valid, reproducible findings in neuroimaging research.

Quantifying the Impact: From SHAMAN to Censoring Strategies

In-scanner head motion represents the largest source of artifact in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data, introducing systematic bias to resting-state functional connectivity (FC) that is not completely removed by standard denoising algorithms [1]. This technical challenge is particularly acute for researchers studying clinical or behavioral traits inherently associated with greater motion, such as psychiatric disorders. Without knowing whether observed trait-FC relationships are impacted by residual motion, researchers risk reporting false positive results that do not reflect genuine neural associations [1]. The problem persists even in large-scale studies like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, where standard denoising with ABCD-BIDS leaves 23% of signal variance explained by head motion—a substantial improvement over minimally processed data (73%), but still problematic for detecting true neurobiological relationships [1].

The SHAMAN (Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks) framework addresses this fundamental methodological challenge by providing researchers with a quantitative tool to assign a motion impact score to specific trait-FC relationships [1]. This framework is particularly valuable because it distinguishes between motion causing overestimation or underestimation of trait-FC effects—a critical distinction for accurate interpretation of brain-behavior associations [1]. In an assessment of 45 traits from n=7,270 participants in the ABCD Study, SHAMAN revealed that after standard denoising without motion censoring, 42% (19/45) of traits had significant motion overestimation scores while 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores [1].

SHAMAN Methodology: Core Principles and Workflow

Theoretical Foundation

SHAMAN capitalizes on a fundamental distinction between traits and motion states: traits (e.g., weight, intelligence) remain stable over the timescale of an MRI scan, whereas motion is a state that varies from second to second [1]. This temporal dissociation enables the framework to detect when state-dependent motion artifacts systematically influence estimates of trait-dependent neural correlations.

The method improves upon earlier approaches by operating effectively with one or more resting-state fMRI scans per participant, accommodating covariates in statistical models, and providing directional information about whether motion artifact inflates or suppresses observed trait-FC relationships [1].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The SHAMAN framework implements a sophisticated analytical pipeline:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Acquire resting-state fMRI data with associated framewise displacement (FD) calculations

- Apply standard denoising procedures (e.g., ABCD-BIDS pipeline including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter timeseries regression)

- Optional: Apply post-hoc motion censoring at various FD thresholds (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm)

Split-Half Analysis Procedure

- Divide each participant's fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on framewise displacement metrics

- Calculate functional connectivity matrices separately for high-motion and low-motion segments

- Compute difference in correlation structure between high-motion and low-motion halves for each participant

Statistical Analysis and Score Calculation

- Measure significance of differences in connectivity between motion states using permutation testing and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections

- Calculate motion impact score with directionality indicating overestimation or underestimation

- Relate motion impact score direction to trait-FC effect direction:

- Alignment indicates motion overestimation of trait-FC effect

- Opposition indicates motion underestimation of trait-FC effect

Table 1: Key Analytical Outputs of the SHAMAN Framework

| Output Metric | Interpretation | Statistical Foundation |

|---|---|---|

| Motion Overestimation Score | Motion artifact inflates observed trait-FC effect | Significant positive association between motion-FC and trait-FC effects |

| Motion Underestimation Score | Motion artifact suppresses observed trait-FC effect | Significant negative association between motion-FC and trait-FC effects |

| Motion Impact p-value | Statistical significance of motion's influence on trait-FC effect | Permutation-based non-parametric testing |

Figure 1: SHAMAN Analytical Workflow - The computational pipeline for calculating motion impact scores from fMRI data, showing key decision points for classifying overestimation versus underestimation effects.

Performance Comparison: SHAMAN Versus Alternative Approaches

Comparative Framework Efficacy

SHAMAN addresses specific limitations of previous methods for quantifying motion artifact in trait-FC research. Traditional approaches include measuring distance-dependent correlations at different motion censoring levels, assessing spatial similarity between trait-FC and motion-FC effects, and comparing trait-FC effects between motion-matched groups [1]. While each method offers insights, they share a fundamental limitation: inability to establish clear thresholds for acceptable versus unacceptable levels of trait-specific motion artifact [1].

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Motion Artifact Assessment Approaches

| Method | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Trait-Specific Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAMAN Framework | Distinguishes over/underestimation; Works with single scan; Accommodates covariates | Computational intensity; Requires sufficient data for split-half analysis | Yes - provides significance testing for trait-specific motion impact |

| Distance-Dependent Correlations | Identifies systematic spatial patterns of motion artifact | Does not establish trait-specific significance; Agnostic to hypothesis | No - general motion effects only |

| Spatial Similarity Analysis | Quantifies overlap between trait-FC and motion-FC maps | Cannot distinguish directionality of bias; No statistical thresholding | No - qualitative assessment only |

| Motion-Matched Group Comparison | Controls for motion differences between groups | Requires large samples; Lacks single-subject applicability; Resource intensive | Partial - group-level inferences only |

Empirical Performance in Large-Sample Applications

Application of SHAMAN to the ABCD Study dataset (n=7,270) after standard denoising with ABCD-BIDS revealed the pervasive nature of motion artifacts in trait-FC research [1]. Without motion censoring, the framework identified significant motion impacts on the majority of traits assessed:

- 42% (19/45) of traits showed significant motion overestimation scores [1]

- 38% (17/45) of traits showed significant motion underestimation scores [1]

- Only 20% (9/45) of traits showed no significant motion impact [1]

The introduction of motion censoring at framewise displacement (FD) < 0.2 mm dramatically reduced significant overestimation to just 2% (1/45) of traits, demonstrating the effectiveness of rigorous motion censoring for controlling false positive inflation [1]. However, this same censoring threshold did not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores, highlighting how different types of motion artifacts require distinct mitigation strategies [1].

Motion Overestimation vs. Underestimation: Differential Impact and Mitigation

Distinct Mechanisms and Consequences

The SHAMAN framework's ability to distinguish between motion overestimation and underestimation addresses a critical gap in neuroimaging methodology. These directional effects represent fundamentally different forms of bias with distinct implications for interpretation:

Motion Overestimation Effects occur when motion artifact systematically inflates observed trait-FC relationships, creating false positive associations that can lead to erroneous conclusions about brain-behavior relationships. This form of bias is particularly problematic for studies of clinical populations who typically exhibit greater motion, potentially creating illusory neural correlates of psychiatric symptoms [1].

Motion Underestimation Effects occur when motion artifact systematically suppresses genuine trait-FC relationships, creating false negative findings that may cause researchers to overlook true neurobiological associations. This form of bias reduces statistical power and may lead to important neural correlates of behavior being missed in analysis [1].

Differential Response to Mitigation Strategies

The effectiveness of motion mitigation strategies differs substantially for overestimation versus underestimation effects:

Motion Censoring Efficacy

- Overestimation: Censoring at FD < 0.2 mm reduced significant overestimation from 42% to 2% of traits [1]

- Underestimation: Same censoring threshold produced no decrease in significant underestimation scores [1]

Denoising Algorithm Performance

- Standard denoising with ABCD-BIDS achieved 69% relative reduction in motion-related signal variance compared to minimal processing alone [1]

- Despite this improvement, residual motion-FC effects remained strongly correlated with average FC matrix (Spearman ρ = -0.58) [1]

- This residual motion effect persisted even after stringent censoring (Spearman ρ = -0.51) [1]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for SHAMAN Framework Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Measures | Function in SHAMAN Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement (FD), DVARS | Quantifies head motion in fMRI timeseries; used for split-half classification |

| Denoising Pipelines | ABCD-BIDS, FSL FIX, Global Signal Regression | Removes motion artifacts from BOLD signal prior to SHAMAN analysis |

| Functional Connectivity Metrics | Pearson correlation, Partial correlation, Spectral coherence | Quantifies functional connectivity between brain regions for trait-FC and motion-FC effects |

| Statistical Frameworks | Permutation testing, Non-parametric combining, Linear mixed models | Provides statistical foundation for motion impact score calculation and significance testing |

| Large-Scale Datasets | ABCD Study, Human Connectome Project, UK Biobank | Validation cohorts for establishing generalizability of motion impact findings |

The SHAMAN framework represents a significant methodological advancement for identifying and quantifying motion-related artifacts in trait-FC research. By providing directional motion impact scores with statistical thresholds, the method enables researchers to distinguish between false positive inflations (overestimation) and genuine relationships suppressed by noise (underestimation).

The empirical demonstration that motion censoring effectively addresses overestimation but not underestimation effects has profound implications for study design and analytical planning in developmental, clinical, and cognitive neuroscience [1]. Researchers investigating motion-correlated traits must implement comprehensive motion mitigation strategies that extend beyond standard denoising and censoring approaches.

Future applications of SHAMAN may include prospective study design optimization, data quality monitoring during acquisition, and refinement of individualized denoising strategies. As the field continues to recognize the nuanced ways in which motion artifacts can distort brain-behavior relationships, frameworks like SHAMAN provide essential tools for ensuring the validity and reproducibility of functional connectivity research.

Implementing Framewise Displacement (FD) and Censoring (Scrubbing)

Framewise Displacement (FD) and censoring (scrubbing) are established techniques for mitigating motion artifacts in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). However, emerging research reveals a critical trade-off: while aggressive motion censoring effectively reduces motion overestimation (false positive trait-FC relationships), it is less effective against motion underestimation (false negative trait-FC relationships) and can significantly impact data retention and reliability. This guide compares FD-based scrubbing with data-driven alternatives, providing experimental data to inform preprocessing decisions in trait-FC effects research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The SHAMAN Framework for Quantifying Motion Impact

Objective: To assign a trait-specific motion impact score that distinguishes between overestimation and underestimation of trait-functional connectivity (trait-FC) effects [20].

- Procedure:

- Data Splitting: For each participant, the resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) timeseries is split into high-motion and low-motion halves based on Framewise Displacement (FD).

- Trait-FC Effect Calculation: The correlation between a trait (e.g., cognitive score) and functional connectivity (FC) is computed separately for each half.

- Impact Score Calculation: A significant difference in the trait-FC correlation between the two halves indicates a motion impact.

- A motion impact score aligned with the trait-FC effect direction indicates motion overestimation (inflating the observed effect).

- A motion impact score opposite the trait-FC effect direction indicates motion underestimation (masking the true effect).

- Statistical Testing: Permutation testing and non-parametric combining across connections yield a significant p-value for the motion impact score [20].