Motion Correction Algorithms in Biomedical Imaging: A Performance Comparison Across Modalities and Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of motion correction algorithms, addressing a critical challenge in biomedical imaging and drug development.

Motion Correction Algorithms in Biomedical Imaging: A Performance Comparison Across Modalities and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of motion correction algorithms, addressing a critical challenge in biomedical imaging and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of motion artifacts and their impact on quantitative analysis, examines the diverse methodologies from deep learning to model-based approaches, and discusses optimization strategies for real-world applications. By presenting a cross-modality performance analysis and validation frameworks, this review serves as a strategic guide for researchers and professionals selecting and implementing motion correction techniques to enhance data quality, improve diagnostic accuracy, and accelerate model-informed drug development.

Understanding Motion Artifacts: Origins, Impact, and Fundamental Correction Principles

The Critical Challenge of Motion in Quantitative Imaging

Motion artifacts represent one of the most significant and universal challenges in quantitative imaging, compromising data integrity across modalities from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and computed tomography (CT) to functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). In clinical and research settings, even sub-millimeter movements can introduce artifacts that mimic or obscure true physiological signals, ultimately leading to misdiagnosis, reduced statistical power in research studies, and compromised drug development pipelines. The fundamental goal of motion correction is to maximize sensitivity to true biological signals while minimizing false activations or measurements related to movement, a balance that requires sophisticated algorithmic approaches [1]. As quantitative imaging increasingly serves as a biomarker for therapeutic response in clinical trials, the ability to accurately correct for motion has become paramount for ensuring measurement reliability and reproducibility across single and multi-site studies [2] [3].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of motion correction techniques across multiple imaging modalities, presenting experimental data on their performance characteristics and offering detailed methodologies for implementation. By objectively evaluating the strengths and limitations of current approaches, we aim to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate motion correction strategies for their specific quantitative imaging applications.

Motion Correction Algorithms: A Cross-Modality Comparison

Retrospective Correction in Functional MRI

In fMRI, motion correction typically involves estimating rigid body movement parameters and applying transformations to realign a time series of brain images. Current approaches iteratively maximize similarity measures between each time point and a reference image, producing six parameters (x, y, and z translations and rotations) for realignment. Commonly used tools include AIR, AFNI 3dvolreg, FSL mcflirt, and SPM realign tools [1].

A critical consideration in fMRI is whether to include motion parameters as covariates of no interest in the general linear model (GLM). Research has demonstrated that for rapid event-related designs, including motion covariates generally increases GLM sensitivity, with little difference whether motion correction is actually applied to the data. Conversely, for block designs, motion covariate inclusion can have a deleterious impact on sensitivity when even moderate correlation exists between motion and experimental design [1].

Table 1: Comparison of fMRI Motion Correction Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Best Application | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Motion Correction | Analysis without motion correction | Low-motion paradigms | High risk of artifactual activations with task-correlated motion |

| Motion Correction Alone (MC) | Estimation and realignment of data | General purpose use | Reduces motion artifacts but leaves residual variance |

| MC + Motion Covariates (MC+COV) | Realignment with motion parameters in GLM | Event-related designs | Increases sensitivity for event-related data; minimal benefit for block designs |

| Non-MC + Covariates (NONMC+COV) | Motion parameters in GLM without realignment | Specific event-related applications | Similar efficacy to MC+COV for event-related designs |

Prospective Motion Correction in Anatomical MRI

Prospective motion correction (PMC) represents a fundamentally different approach that actively monitors head position and adjusts imaging parameters in real-time during acquisition. Unlike retrospective methods that operate on already-corrupted data, PMC aims to prevent motion artifacts from occurring initially. Marker-based PMC systems typically use optical tracking of markers rigidly attached to a subject's head, updating gradient directions, RF pulses, and receiver phase accordingly [4].

The effectiveness of PMC depends heavily on marker fixation method. Comparative studies have evaluated different fixation approaches:

- Mouth guard fixation: Provides stable attachment but may cause patient discomfort

- Nose bridge fixation: Better patient tolerance but potentially less stability

Quantitative evaluation demonstrates that mouth guard fixation achieves better PMC performance compared to nose bridge approaches, highlighting the importance of hardware configuration in motion correction efficacy [4].

Motion Correction in Coronary CT Angiography

In cardiac CT, motion correction must address specific challenges related to heart motion throughout the cardiac cycle. First-generation motion correction algorithms like SnapShot Freeze (SSF1) track and compensate for coronary artery motion using data from three adjacent phases, significantly improving image quality in patients with high heart rates. However, SSF1 only addresses coronary structures, leaving other cardiac motion artifacts uncorrected [5].

The second-generation SSF2 algorithm extends correction to the entire heart, providing more comprehensive motion artifact reduction. A recent retrospective study of 151 patients demonstrated SSF2's superiority: the algorithm significantly improved image quality scores (median = 3.67 for SSF2 vs. 3.0 for SSF1 and standard reconstruction, p < 0.001) and enhanced diagnostic performance for both stenosis assessment and CT fractional flow reserve (CT-FFR) calculations [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of CT Motion Correction Algorithms

| Metric | Standard Reconstruction | SSF1 Algorithm | SSF2 Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Quality Score (median) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.67* |

| Correlation with invasive FFR | r = 0.552 | r = 0.593 | r = 0.652* |

| AUC for Ischemic Lesion Diagnosis (per-lesion) | 0.742 | 0.795 | 0.887* |

| AUC for Ischemic Lesion Diagnosis (per-patient) | 0.768 | 0.812 | 0.901* |

*Statistically significant improvement over other methods (p < 0.001)

Motion Artifact Correction in fNIRS

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy faces unique motion challenges, particularly in pediatric populations where data typically contains more artifacts than adult studies. Research comparing six prevalent motion correction techniques with child participants (ages 6-12) performing language tasks has revealed differential effectiveness across artifact types [6].

Motion artifacts in fNIRS are categorized into four distinct types:

- Type A: Sudden spikes (>50 SD from mean within 1 second)

- Type B: Peaks (100 SD from mean, 1-5 seconds duration)

- Type C: Gentle slopes (300 SD from mean, 5-30 seconds duration)

- Type D: Slow baseline shifts (>500 SD from mean, >30 seconds duration)

Evaluation of correction methods using five predefined metrics identified that moving average and wavelet methods yielded the best outcomes for pediatric fNIRS data, though optimal approach selection depends on the specific artifact types prevalent in the dataset [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Framework for Prospective Motion Correction Evaluation

Establishing a robust framework for evaluating PMC performance requires addressing the challenge of variable intrinsic motion patterns between acquisitions. One developed methodology uses recorded motion trajectories from human subjects replayed in phantom experiments to enable controlled comparisons [4].

Experimental Protocol:

- Motion Tracking: Record head motion trajectories from human subjects during T1-weighted MRI scans using optical marker-based tracking

- Phantom Replay: Reproduce identical motion patterns in phantom experiments by modulating imaging parameters according to in-vivo recordings

- Image Quality Assessment: Quantify motion-induced degradation using:

- Average Edge Strength (AES): Measures image blurring at edges

- Haralick Texture Entropy (CoEnt): Captures diffuse artifacts and texture changes using gray level co-occurrence matrix analysis

Statistical Analysis: Incorporate motion pattern variability as a covariate in models comparing correction techniques to account for intrinsic differences in motion severity and pattern between scans [4].

Deep Learning Approaches for MRI Motion Correction

Emerging deep learning techniques offer promising alternatives to traditional motion correction algorithms. One recently developed approach uses a deep network to reduce the joint image-motion parameter search to a search over rigid motion parameters alone [7].

Methodology:

- Network Training: Train reconstruction network using simulated motion-corrupted k-space data with known motion parameters

- Network Architecture: Design network that produces reconstruction from two inputs: corrupted k-space data and motion parameters

- Test-Time Estimation: Estimate unknown motion parameters by minimizing data consistency loss between motion parameters, network-based reconstruction, and acquired measurements

Experimental Validation: Intra-slice motion correction experiments on simulated and realistic 2D fast spin echo brain MRI demonstrate high reconstruction fidelity while maintaining explicit data consistency optimization [7].

Comparative Evaluation of fNIRS Correction Techniques

A systematic comparison of fNIRS motion correction methods evaluated six prevalent techniques on data from children (ages 6-12) performing a language task [6].

Experimental Design:

- Participants: 12 children (8 females, mean age = 9.9 years, SD = 1.75)

- Task: Auditory grammatical judgment with rapid event-related design (60 trials total)

- fNIRS Setup: TechEN-CW6 system with 690 and 830 nm wavelengths, 3 channels sampled at 10 Hz over left inferior frontal gyrus

- Data Processing: Implemented using Homer2 fNIRS processing package and custom MATLAB tools

Correction Methods Compared:

- Wavelet-based correction

- Spline interpolation

- Principal component analysis (PCA)

- Moving average (MA)

- Correlation-based signal improvement (CBSI)

- Combined wavelet and MA approach

Evaluation Metrics: Five predefined metrics assessing artifact reduction and signal preservation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Motion Correction Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Motion Tracking Systems | Real-time head position monitoring | Prospective motion correction in MRI | MR-compatible cameras, marker-based tracking, real-time parameter updates |

| Moiré Phase Tracking Marker | Reference for optical tracking | Prospective motion correction | Rigid attachment to subject, precise motion capture |

| Homer2 Software Package | fNIRS data processing | Optical brain imaging analysis | Modular pipeline for motion correction, artifact detection, and signal processing |

| SnapShot Freeze Algorithms | Cardiac motion correction | Coronary CT angiography | SSF1: coronary-specific correction; SSF2: whole-heart correction |

| FSL mcflirt & SPM Realign | Image realignment | fMRI preprocessing | Rigid-body registration, integration with analysis pipelines |

| Deep Motion Correction Networks | Learning-based reconstruction | MRI motion correction | Data-consistent reconstructions, motion parameter estimation |

| Geometric Phantoms | Controlled validation | Algorithm performance testing | Anatomically realistic shapes, known ground truth geometry |

Implications for Drug Development and Quantitative Biomarkers

The reliability of motion correction has profound implications for drug development, where quantitative imaging often serves as a pharmacodynamic biomarker in clinical trials. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA have established formal processes for qualifying technologies such as fMRI for specific contexts of use in drug development [2]. However, the burden of proof for biomarker qualification is high, requiring characterization of precision and reproducibility across multiple trials.

Motion artifacts directly impact the value of fMRI readouts for assessing CNS drug effects, as these measurements must be both reproducible and modifiable by pharmacological intervention. Inconsistent motion correction can introduce variability that obscures true drug effects or creates false positives. The Quantitative Imaging Network (QIN) specifically addresses these challenges by promoting research and development of quantitative imaging tools with appropriate correction for technical confounds like motion [3].

Effective motion correction is particularly critical for:

- Target engagement studies: Establishing CNS effects of pharmacological treatment

- Dose-response relationships: Guiding dose selection for later trial phases

- Multi-site trials: Ensuring consistency across different scanning sites and protocols

- Longitudinal studies: Maintaining measurement consistency across multiple time points

Motion correction remains a critical challenge in quantitative imaging, with optimal approach selection highly dependent on imaging modality, experimental design, and subject population. Our comparative analysis demonstrates that while substantial progress has been made across all modalities, each technique carries specific strengths and limitations.

Key findings indicate:

- In fMRI, motion covariate inclusion benefits event-related designs but may harm block design analyses

- Prospective motion correction in MRI shows promise but depends on robust marker fixation

- Second-generation CT motion correction algorithms (SSF2) significantly outperform first-generation approaches

- For pediatric fNIRS, moving average and wavelet methods provide optimal artifact reduction

- Emerging deep learning approaches offer new paradigms for data-consistent motion correction

Future developments will likely focus on integrating multiple correction strategies, developing more sophisticated subject-specific approaches, and creating standardized validation frameworks that account for intrinsic motion variability. As quantitative imaging continues to expand its role in clinical trials and therapeutic development, robust motion correction will remain essential for generating reliable, reproducible biomarkers capable of informing clinical decision-making.

In biomedical imaging, patient or subject motion presents a significant challenge that can compromise image quality and diagnostic utility. Motion artifacts manifest differently across modalities, from blurring and ghosting in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to misregistration and quantitative inaccuracies in Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT). Understanding and correcting for these motions is paramount in both clinical and research settings, particularly in drug development where precise image-based biomarkers are essential. Motion can be broadly categorized into rigid body motion, involving simple translation and rotation of a volume, and non-rigid deformation, which includes complex, localized changes in shape [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary motion correction algorithms, detailing their performance, underlying methodologies, and appropriate applications.

Characterizing Motion Types and Artifacts

Rigid Body Motion

Rigid body motion describes the movement of an object where the relative distance between any two points within the object remains unchanged. In the context of head and brain MRI, this is often modeled with six degrees of freedom: translations along the x, y, and z axes, and rotations around these same axes (pitch, roll, yaw) [8] [9]. According to the Fourier shift theorem, such motion induces specific changes in the acquired k-space data: object translation causes a linear phase ramp, while object rotation results in an identical rotation of the k-space data [8]. In images, this typically leads to ghosting artifacts (from periodic motion) or general blurring (from random motion patterns).

Non-Rigid Deformations

Non-rigid deformations involve more complex movements where the object's internal geometry changes. This is common in thoracic and abdominal imaging due to respiratory and cardiac cycles, as well as in soft tissues. These deformations cannot be described by a simple set of global parameters and often require sophisticated models accounting for local displacement fields. The 3D affine motion model, for instance, extends the rigid model to include 12 degrees of freedom, incorporating shearing and scaling in addition to translation and rotation [8]. Artifacts from non-rigid motion are often more diffuse and challenging to correct, leading to regional distortions and inaccurate quantitation.

Comparative Analysis of Motion Correction Algorithms

The performance of motion correction algorithms varies significantly based on the imaging modality, the type of motion, and the specific clinical or research question. The table below provides a structured comparison of several advanced methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Motion Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Imaging Modality | Correction Type | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNet+JE [9] | 3D MRI (MPRAGE) | Hybrid Deep Learning & Joint Estimation | No significant quality difference vs. JE; Median runtime reduction: 2.00-4.05x vs. JE. | Combines robustness of physics-based JE with speed of deep learning; less susceptible to data distribution shifts. |

| SnapShot Freeze 2 (SSF2) [5] | Coronary CT Angiography (CCTA) | Prospective Motion Correction | Overall quality score: 3.67 (vs. 3.0 for STD/SSF1); Best correlation with invasive FFR (r=0.652). | Whole-heart motion correction; improves diagnostic accuracy for stenosis and CT-FFR calculations. |

| Elastic Motion Correction with Deblurring (EMCD) [10] | Oncologic PET/CT (FDG/DOTATATE) | Data-Driven Motion Correction | Lesion SUVmax: ~10.75 (vs. 9.00 for UG); CNR: ~9.0 (vs. 7.89 for UG and 6.31 for BG-OG). | Utilizes all PET counts, improving quantitation (SUVmax, CNR) and lesion detectability without increasing noise. |

| Joint Estimation (JE) [9] | 3D MRI (MPRAGE) | Retrospective Motion Correction | Benchmark for image correction quality; used as a reference for evaluating UNet+JE. | Physics-based model; does not require specialized hardware or pulse sequences. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for 3D MRI Motion Correction (UNet+JE vs. JE)

A study evaluating the UNet+JE and JE algorithms utilized T1-weighted 3D MPRAGE scans from healthy participants with both simulated (n=40) and in vivo (n=10) motion corruption [9].

- Data Simulation: Motion corruption was introduced by applying random, piecewise-constant rigid-body motion trajectories to the k-space data of motion-free scans. The motion states, defined by six parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations), were prescribed over segments of the sampling pattern ("shots").

- Algorithm Workflow: The JE method solves a large-scale optimization problem, alternating between estimating the motion-corrected image and the motion trajectory that minimizes data consistency errors between the acquired motion-corrupted k-space and the motion-model-corrected projected data [9]. The UNet+JE hybrid approach integrates a neural network (UNetmag) within the JE framework to provide an initial, rapidly improved image, which accelerates the convergence of the subsequent JE process.

- Performance Evaluation: Image quality was compared using quantitative metrics like Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) and Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE). Computational runtime was also a key metric.

Protocol for CCTA Motion Correction (SSF2 vs. SSF1)

A retrospective study involved 151 patients who underwent CCTA and invasive coronary angiography (ICA) or FFR within three months [5].

- Image Reconstruction: CCTA images for each patient were processed in three ways: standard iterative reconstruction (STD), with the first-generation motion correction algorithm SSF1, and with the second-generation SSF2.

- SSF1 Methodology: SSF1 tracks and compensates for coronary artery motion using data from three adjacent phases in the same cardiac cycle. It characterizes the motion path to estimate vessel position at a target phase [5].

- SSF2 Methodology: SSF2 extends the motion correction range to encompass the entire heart, providing a more comprehensive correction that improves lumen segmentation [5].

- Performance Evaluation: Image quality was scored by blinded readers. Diagnostic performance for detecting obstructive stenosis (≥50% in left main artery or ≥70% in other vessels) and ischemic lesions (FFR ≤0.8) was assessed against ICA/FFR as a reference. The correlation and consistency between CT-FFR values derived from each method and the invasive FFR were calculated.

Protocol for Oncologic PET/CT Motion Correction (EMCD vs. OG)

A prospective study enrolled 78 adults undergoing standard-of-care FDG or DOTATATE PET/CT [10].

- Image Reconstruction: For each subject, four types of images were reconstructed:

- Ungated (UG): Standard reconstruction without motion correction.

- Belt-Gating Optimal Gate (BG-OG): Reconstruction using only a fraction (typically 33-50%) of PET data corresponding to a specific respiratory phase.

- BG-EMCD: Elastic motion correction using the respiratory signal from a belt.

- DDG-EMCD: Elastic motion correction using a data-driven gating signal extracted from the PET raw data itself.

- EMCD Methodology: Unlike OG, which discards a substantial portion of acquired counts, EMCD utilizes 100% of the PET data. It estimates and corrects for respiratory motion by elastically deforming the image volume, effectively "deblurring" the image without the noise penalty associated with data rejection [10].

- Performance Evaluation: Tracer-avid lesions in the lower chest/upper abdomen were segmented. Quantitative metrics including maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) were extracted. Two blinded readers independently assessed overall image quality and lesion count.

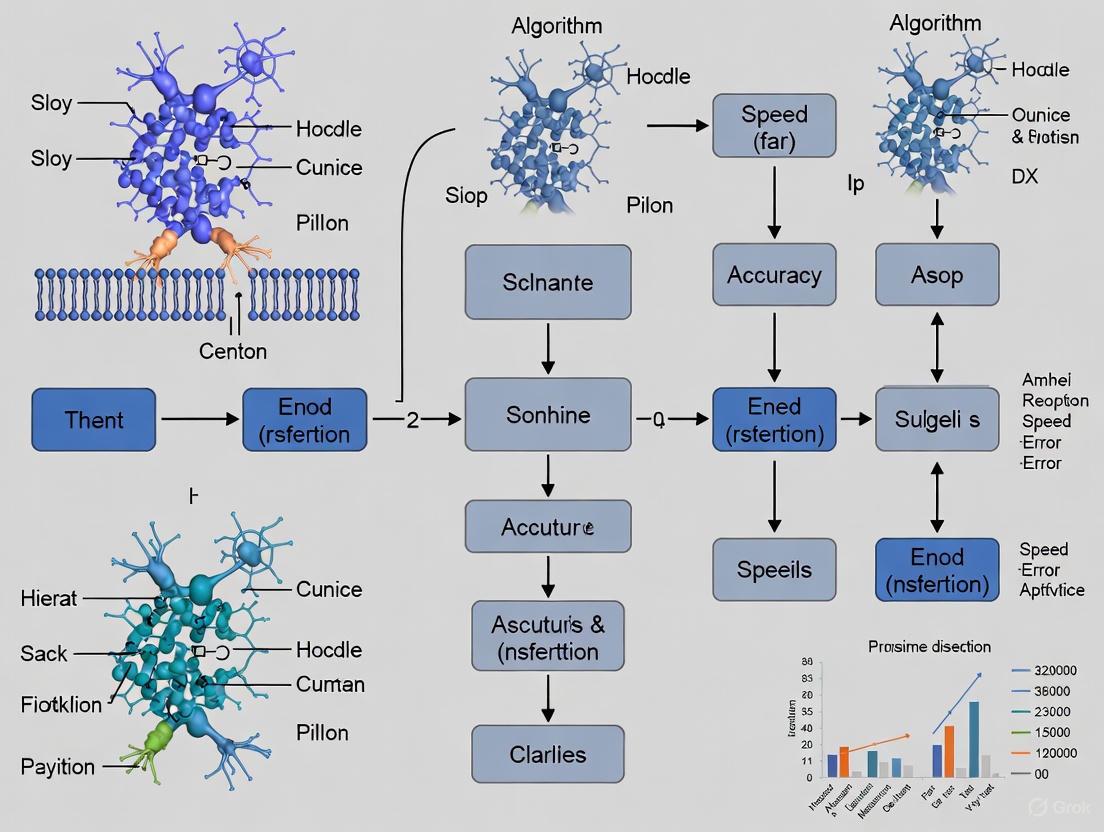

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Motion Correction Decision Workflow

Hybrid Deep Learning and Joint Estimation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Motion Correction Research

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application | Relevance in Motion Correction Research |

|---|---|---|

| andi-datasets Python Package [11] | Generation of simulated single-particle trajectories. | Provides ground truth data for developing and benchmarking methods that detect changes in dynamic behavior, such as diffusion coefficient or motion mode. |

| PyMoCo_v2 [9] | Publicly available source code for 3D hybrid DL-JE algorithm. | Enables replication and extension of the UNet+JE method for 3D MRI motion correction; a key tool for algorithmic development. |

| Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) Model [11] | Simulation of particle trajectories with tunable anomalous diffusion. | Serves as a model to generate realistic biological motion data with controlled parameters for objective method evaluation. |

| Data Consistency Cost Function [9] | Core component of Joint Estimation (JE) algorithms. | A physical model that measures discrepancy between acquired and motion-corrected projected data; drives the optimization in model-based correction. |

| Elastic Motion Correction with Deblurring (EMCD) [10] | Advanced reconstruction for respiratory motion in PET. | A state-of-the-art tool for correcting non-rigid motion in oncologic PET, improving quantitative accuracy and lesion detection. |

Motion artifacts represent a significant challenge in medical imaging, directly compromising the quantitative data essential for research and clinical decision-making. The performance of motion correction algorithms is therefore not merely a technical metric but a fundamental determinant of data fidelity. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary motion correction techniques, framing their performance within a broader thesis on algorithm evaluation. It objectively assesses their impact on quantitative measurements of metabolic activity, blood flow, and tissue micro-architecture across multiple imaging modalities, including Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Computed Tomography (CT), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). The analysis is supported by experimental data from recent phantom and human studies, with methodologies and outcomes structured for direct comparison.

Comparative Performance of Motion Correction Algorithms

The following tables synthesize quantitative data from recent studies, enabling a direct comparison of how different motion correction methods affect key analytical measurements.

Table 1: Impact of Motion Correction on Metabolic PET Quantification (Brain Imaging)

| Metric / Parameter | No Motion Correction (NMC) | Post-Reconstruction Registration (PRR) | Frame-Based MC (UMT Frame) | Event-by-Event MC (UMT EBE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Quality (Visual) | Noticeable blurring [12] | Mitigated motion blurring [12] | Mitigated motion blurring [12] | Most distinct gyri/sulci depiction [12] |

| TAC Smoothness (Residual SD) | Largest deviation [12] | Large deviations from intraframe motion [12] | Large deviations from intraframe motion [12] | Smoothest TAC; lowest residual SD [12] |

| Quantitative SUV Accuracy (Relative Error) | Not quantified in study | Not quantified in study | SUV~mean~: -2.5% ± 1.7%; SUV~SD~: -8.6% ± 4.7% [13] | SUV~mean~: 0.3% ± 0.8%; SUV~SD~: 1.1% ± 2.5% [13] |

| Motion Estimation Accuracy (MME) | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | 4.8 ± 1.0 mm [13] | 1.3 ± 0.2 mm [13] |

Table 2: Performance in Cardiothoracic and Vascular Imaging

| Metric / Parameter | Standard Reconstruction (STD) | First-Gen MC (SSF1) | Second-Gen MC (SSF2) | Data-Driven Gating + RRA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Quality Score (Median) | 3.0 [5] | 3.0 [5] | 3.67 [5] | 3.90 ± 0.86 [14] |

| CT-FFR vs. Invasive FFR Correlation (r) | Not reported | 0.795 [5] | 0.887 [5] | Not Applicable |

| Lesion SUV~max~ Change (Δ%) | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | +3.9% (p < 0.001) [14] |

| Lesion Volume Change (Δ%) | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | -18.4% (p < 0.001) [14] |

| T1/T2 Map Reconstruction Time | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | 2.5 hours (Reference) [15] |

| Deep Learning MC Reconstruction Time | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | 24 seconds [15] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and critical assessment, this section outlines the core methodologies from the studies cited in the comparative tables.

Protocol 1: Multi-Tracer Human Brain PET on Ultra-High Performance System

This protocol evaluated motion correction methods for quantifying metabolic and receptor binding parameters.

- Imaging System: Ultra-high performance brain PET system (NeuroEXPLORER) [12].

- Tracers & Subjects: Scans were performed with three tracers:

18F-FE-PE2I(dopamine transporters, n=2),11C-PHNO(dopamine D2/D3 receptors, n=2), and18F-SynVesT-1(SV2A, n=2) [12]. - Motion Tracking: A markerless motion tracking system (United Healthcare UMT) collected motion data at 30 Hz throughout all scans [12].

- Data Reconstruction: List-mode data were reconstructed using Motion-compensation OSEM List-mode Algorithm for Resolution-recovery reconstruction (MOLAR) with 0.8-mm voxels [12].

- Compared Methods:

- NMC: No motion correction.

- PRR: Post-reconstruction registration using FLIRT.

- UMT Frame MC: Frame-based correction using average patient position from UMT data.

- UMT EBE MC: Event-by-event correction using UMT data. Both UMT methods corrected for attenuation mismatch [12].

- Quantitative Analysis: Time-activity curves (TACs) were derived from the AAL template. The standard deviation of the residuals around fitted TACs was computed to measure noise and instability introduced by motion [12].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced Motion Correction in Pediatric PET

This protocol assessed a learning-based method to improve motion estimation in low-count scenarios, crucial for pediatric imaging and dose reduction.

- Imaging System: GE Discovery MI Gen 2 PET/CT scanner [13].

- Data Acquisition: 18F-FDG brain PET in pediatric patients (<21 years old), including a scripted head movement period. List-mode data were down-sampled to simulate 1/9 of the injected dose [13].

- Motion Correction Framework:

- List-mode data were reconstructed into 0.5s frames with 55k (reduced-count) and 500k (full-count) events.

- A patch-based Artificial Neural Network (ANN) was trained to enhance the quality of the reduced-count 55k-event frames.

- Rigid image registration was performed using the reduced-count frames, the ANN-enhanced frames, and the full-count frames to derive three sets of motion vectors [13].

- Outcome Measures:

- Motion Estimation Accuracy: Mean Mesh Error (MME) compared to the full-count reference.

- Image Quality: Normalized Mean Square Error (NMSE) of final reconstructed images.

- Quantitative Accuracy: Relative error in standardized uptake values (SUVs) across 8 brain ROIs [13].

Protocol 3: Motion Correction for CT Fractional Flow Reserve (CT-FFR)

This study validated motion correction algorithms for improving the diagnostic accuracy of coronary CT angiography and derived CT-FFR.

- Study Population: 151 patients who underwent CCTA and invasive coronary angiography/FFR within 3 months [5].

- Image Processing: CCTA images were reconstructed using an iterative technique and then processed with two motion correction algorithms: first-generation (SSF1) and second-generation (SSF2) SnapShot Freeze [5].

- Analysis:

- Image Quality: Scored by radiologists on a 5-point scale.

- Stenosis Assessment: Obstructive stenosis was defined based on diameter stenosis (DS).

- CT-FFR Calculation: Performed on standard, SSF1-, and SSF2-corrected images [5].

- Reference Standard: Invasive FFR ≤ 0.8 or ≥ 90% diameter stenosis was considered an ischemic lesion [5].

Protocol 4: Data-Driven Gating for Lung Cancer PET/CT

This protocol used phantom and patient studies to validate a data-driven gating (DDG) method with a Reconstruct, Register, and Average (RRA) motion correction algorithm.

- Phantom Validation: A motion platform moved a phantom containing spheres (10-28 mm) with varying amplitudes (2-4 cm) and durations (3-5 s). Metrics included SUV~max~, SUV~mean~, volume, and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) relative to a static ground truth [14].

- Patient Study: 30 lung cancer patients with 76 lung lesions (<3 cm) were prospectively enrolled [14].

- Comparison: Ungated PET images were compared to RRA motion-corrected PET images.

- Outcome Measures:

- Visual Quality: Scored by two radiologists on a 5-point scale.

- Quantitative Metrics: SUV~max~, SUV~mean~, SUV~peak~, metabolic volume, and CNR of the lung lesions [14].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflows and conceptual hierarchies derived from the analyzed studies.

Data-Driven Motion Correction Workflow

Motion Correction Algorithm Performance Hierarchy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for Motion Correction Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| 18F-FE-PE2I | PET radiopharmaceutical for imaging dopamine transporters in the brain. [12] | Used in multi-tracer human study on NeuroEXPLORER. [12] |

| 11C-PHNO | PET radiopharmaceutical for imaging dopamine D2/D3 receptors. [12] | Used in multi-tracer human study on NeuroEXPLORER. [12] |

| 18F-SynVesT-1 | PET radiopharmaceutical for imaging synaptic density (SV2A protein). [12] | Used in multi-tracer human study on NeuroEXPLORER. [12] |

| 18F-FDG | PET radiopharmaceutical for measuring glucose metabolism. [13] | Used in pediatric brain PET study for machine learning motion correction. [13] |

| SnapShot Freeze 2 (SSF2) | A second-generation, whole-heart motion correction algorithm for CCTA. [5] | Improved image quality and CT-FFR diagnostic accuracy. [5] |

| MOLAR | Motion-compensation OSEM List-mode Algorithm for Resolution-recovery reconstruction. [12] | Used for reconstruction on the NeuroEXPLORER system. [12] |

| alignedSENSE | A data-driven motion correction algorithm based on the SENSE model for MRI. [16] | Combined with DISORDER trajectory for motion correction in ultra-low-field MRI. [16] |

This guide provides an objective comparison of three fundamental motion correction paradigms used in medical imaging: sinogram-based, image-based, and data-driven approaches. It is designed to assist researchers and scientists in selecting appropriate methodologies for mitigating motion artifacts to ensure data integrity in clinical and research applications.

Motion artifacts present a significant challenge across various medical imaging modalities, including Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and Positron Emission Tomography (PET). These artifacts can degrade image quality, reduce diagnostic value, and lead to inaccurate quantification. This guide systematically compares three core motion correction paradigms—sinogram-based, image-based, and data-driven approaches—by outlining their underlying principles, providing experimental protocols, and presenting quantitative performance data from seminal studies. The objective is to furnish professionals with the necessary information to evaluate and implement these algorithms effectively within their own research and development workflows.

◥ Comparative Analysis of Correction Paradigms

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the three motion correction paradigms.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Motion Correction Paradigms

| Paradigm | Core Principle | Typical Modalities | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinogram-Based | Corrects or models motion directly in the raw projection data (sinogram) before image reconstruction. | CT, HR-pQCT [17], PET [18] | Addresses the root cause of artifacts; can be highly accurate for rigid motion [17] [18]. | Requires access to raw projection data; motion model may oversimplify complex in-vivo motion [17]. |

| Image-Based | Corrects for motion after image reconstruction by registering and aligning individual image volumes. | fMRI [19], MRI [20], PET | Widely available in software tools (SPM, FSL, AFNI); does not require raw data [19]. | Cannot correct for through-plane motion in 2D sequences or data inconsistencies from spin history effects [20] [19]. |

| Data-Driven | Extracts motion information directly from the acquired imaging data itself without external hardware. | PET [21] [22], NIRS [23] | No additional hardware needed; integrates seamlessly into clinical workflows; enables event-by-event correction [21] [22]. | Performance depends on data statistics and count rates; may miss very slow drifts [21]. |

◥ Sinogram-Based Motion Correction

Sinogram-based approaches operate on the raw projection data acquired by the scanner. A prominent application is the correction of rigid motion in High-Resolution peripheral Quantitative CT (HR-pQCT).

▍ Experimental Protocol: ESWGAN-GP for HR-pQCT

The following workflow was designed to correct for rigid motion artifacts such as cortical bone streaking and trabecular smearing [17].

- Motion Simulation: A motion simulation model applies random in-plane rotations to the 2D object, introducing alterations to the sinogram. The motion-corrupted sinogram is then reconstructed using the Simultaneous Iterative Reconstruction Technique (SIRT) to generate a motion-artifacted image [17].

- Dataset Creation: This process creates a paired dataset consisting of the motion-corrupted image and the original motion-free ground truth image, suitable for supervised learning [17].

- Network Training: An Edge-enhanced Self-attention Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (ESWGAN-GP) is trained on the paired dataset.

- Generator: A U-Net architecture incorporates Sobel-kernel-based convolutional layers in its skip connections to enhance and preserve bone microstructure edges.

- Self-Attention: Both generator and discriminator use self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range spatial dependencies.

- Loss Functions: The model employs a composite loss function, including adversarial loss, a VGG-based perceptual loss to reconstruct fine micro-structures, and pixel-wise/total variation loss [17].

- Validation: Performance is quantitatively evaluated on both simulated (source) and real-world (target) datasets using Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), and Visual Information Fidelity (VIF) metrics [17].

▍ Performance Data

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of the ESWGAN-GP Model on HR-pQCT Data

| Dataset | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Structural Similarity (SSIM) | Visual Information Fidelity (VIF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated (Source) | 26.78 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| Real-World (Target) | 29.31 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for the sinogram-based ESWGAN-GP correction method.

Diagram 1: Sinogram-based ESWGAN-GP motion correction workflow.

◥ Data-Driven Motion Correction

Data-driven methods extract motion information solely from the acquired data. In brain PET, these approaches are crucial for correcting head motion that degrades image resolution and quantitative accuracy.

▍ Experimental Protocol: Centroid of Distribution (COD) in PET

This protocol details a data-driven method for detecting and correcting rigid head motion in list-mode PET data [21].

- Data Acquisition: A dynamic PET scan is acquired in list-mode format, where each detected event is recorded with its time stamp and line-of-response (LOR) coordinates.

- Motion Detection - COD Trace Generation:

- The central coordinates (Xi, Yi, Zi) of each event's LOR are calculated.

- These coordinates are averaged over short time intervals (e.g., 1 second) to generate raw COD traces for lateral (CX), anterior-posterior (CY), and superior-inferior (CZ) directions [21].

- Motion Detection - Time Point Identification:

- The COD direction with the highest variance after injection is selected for motion detection, denoted C(t).

- A median filter is applied to C(t) to create a smoothed trace M(t).

- The forward difference D(t) = M(t + Δt) - M(t) is calculated. Time points (t~i~) where D(t) exceeds a user-defined threshold are flagged as motion events.

- Additional motion time points can be added manually via visual assessment to capture slower drifts [21].

- Motion-Compensated Reconstruction:

- The list of motion time points divides the acquisition into motion-free frames (MFFs).

- Each MFF is reconstructed without attenuation correction and rigidly registered to a reference frame.

- The resulting transformation matrices are applied to perform a final motion-compensated reconstruction of the entire dataset [21].

▍ Performance Data

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Data-Driven Motion Correction on PET SUV

| Motion Correction Method | ¹⁸F-FDG SUV Difference vs. HMT | ¹¹C-UCB-J SUV Difference vs. HMT |

|---|---|---|

| No Motion Correction (NMC) | -15.7% ± 12.2% | -20.5% ± 15.8% |

| Frame-Based Image Registration (FIR) | -4.7% ± 6.9% | -6.2% ± 11.0% |

| Data-Driven COD Method | 1.0% ± 3.2% | 3.7% ± 5.4% |

HMT: Hardware-based Motion Tracking (Gold Standard). Data presented as mean ± SD [21].

◥ Image-Based Motion Correction

Image-based correction is one of the most common strategies, particularly in fMRI and MRI, where it is applied to reconstructed image volumes.

▍ Experimental Protocol: Prospective Motion Correction (PROMO) in MRI

The PROMO framework prospectively corrects for motion during the MRI scan itself, preventing artifacts from occurring [20].

- Navigator Acquisition: Three orthogonal, low flip-angle, thick-slice, single-shot spiral acquisitions (SP-Navs) are played out during the intrinsic longitudinal recovery time (e.g., T1 recovery) of the main pulse sequence. These are acquired in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes [20].

- Real-Time Processing: Each SP-Nav is immediately reconstructed into a low-resolution image.

- Motion Tracking: The reconstructed SP-Nav images are fed as input to an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) algorithm. The EKF performs recursive state estimation to track the 3D rigid-body motion of the head in real-time [20].

- Prospective Correction: The estimated motion parameters are fed back to the scanner's pulse sequence in real-time. The coordinate system for all subsequent RF pulses and gradient fields is updated to remain fixed relative to the patient's head, effectively negating the motion [20].

The diagram below illustrates this real-time feedback loop.

Diagram 2: Prospective motion correction (PROMO) real-time feedback loop in MRI.

▍ Performance Data

A comparative study of image-based motion correction tools in fMRI evaluated packages including AFNI, AIR, BrainVoyager, FSL, and SPM2. The study used both phantom data with known motion and human fMRI data.

- Motion Estimation Accuracy: In phantom studies, AFNI and SPM2 yielded the most accurate motion estimation parameters [19].

- Computational Efficiency: AFNI was found to be the fastest package among those tested [19].

- Impact on Activation Detection: In human data, all packages provided significant benefits, with motion correction improving the magnitude of detected activations by up to 20% and the cluster size by up to 100%. However, no single software package produced dramatically better activation results than the others, indicating that the choice of tool may be less critical than the decision to apply motion correction in the first place [19].

◥ The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists key software tools and algorithms essential for implementing the motion correction paradigms discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Motion Correction

| Tool / Algorithm Name | Paradigm | Primary Modality | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESWGAN-GP [17] | Sinogram-Based | HR-pQCT/CT | A deep learning network for correcting rigid motion artifacts; uses edge-enhancement and self-attention to preserve bone micro-structures. |

| Centroid of Distribution (COD) [21] | Data-Driven | PET | A data-driven algorithm that detects head motion from changes in the center of distribution of PET list-mode events, enabling event-by-event correction. |

| PROMO (SP-Nav/EKF) [20] | Image-Based / Prospective | MRI | An image-based framework using spiral navigators and an Extended Kalman Filter for real-time prospective motion correction in high-resolution 3D MRI. |

| AFNI [19] | Image-Based | fMRI | A software suite offering fast and accurate volume registration for motion correction of BOLD fMRI time series data. |

| SPM2 [19] | Image-Based | fMRI | A widely used software package for processing brain imaging data, including robust motion correction algorithms for fMRI. |

| FSL [19] | Image-Based | fMRI | FMRIB's Software Library containing tools for fMRI analysis, such as the MCFLIRT tool for rigid-body motion correction. |

Algorithmic Approaches: From Deep Learning to Model-Based Correction Methods

This guide provides an objective comparison of three deep learning architectures—ESWGAN-GP, 3D-ResNet, and Self-Attention Mechanisms—for motion correction in medical imaging, a critical step for ensuring data quality in drug development and clinical research.

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of the featured architectures across different medical imaging applications.

| Architecture | Application & Task | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Performance | Inference Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESWGAN-GP (Edge-enhanced Self-attention WGAN-GP) | HR-pQCT Bone Imaging; Motion artifact correction [17] [24] | Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM)Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)Visual Information Fidelity (VIF) | SSIM: 0.81 (Simulated), 0.87 (Real-world) [24]SNR: 26.78 (Simulated), 29.31 (Real-world) [24] | Information missing |

| 3D-ResNet with Positional Encodings | 13N-ammonia PET-MPI; Frame-by-frame motion correction [25] | Lin’s Concordance CorrelationBland-Altman Limits of Agreement (MBF) | MBF Concordance: 0.9938 [25]Agreement: -0.28 to 0.21 [mL/g/min] (Mean diff: -0.03) [25] | <1 second per study [25] |

| 3D-ResNet | 18F-flurpiridaz PET-MPI; Frame-by-frame motion correction [26] | Area Under the Curve (AUC) for CAD detectionBland-Altman Limits of Agreement (MBF) | AUC for Stress MBF: 0.897 [26]Agreement: ± 0.24 mL/g/min (Mean diff: 0.00) [26] | Significantly faster than manual [26] |

| Self-Attention Model | fMRI; Slice-to-volume registration [27] | Euclidean Distance (Target Registration Error)Registration Speed | Euclidean Distance: 0.93 mm [27]Registration Speed: 0.096 s [27] | 0.096 seconds (vs. 1.17s for conventional) [27] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ESWGAN-GP for HR-pQCT Motion Correction

The ESWGAN-GP framework was designed to correct rigid-motion artifacts like cortical bone streaking and trabecular smearing in high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) [17] [24].

- Data Preparation: A motion simulation model was first used to create paired datasets. This model applied random in-plane rotations to the 2D object being imaged, introducing alterations in the sinogram data. These corrupted sinograms were then reconstructed using the Simultaneous Iterative Reconstruction Technique (SIRT) to generate motion-corrupted images, with the original images serving as the ground truth [24].

- Network Architecture: The model uses a U-Net shaped generator within a Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) backbone for stable training. Key enhancements include [17] [24]:

- Sobel-kernel-based CNN (SCNN): Integrated into skip connections to enhance and preserve trabecular bone edges.

- Self-attention mechanisms: Incorporated in both generator and discriminator to capture long-range spatial dependencies across the image.

- Loss Functions: The model employs a combination of adversarial loss from the WGAN-GP, a VGG-based perceptual loss to reconstruct fine micro-structural features, and for one variant (ESWGAN-GPv1), pixel-wise L1 loss and Total Variation (TV) loss for smoother outputs [17] [24].

3D-ResNet for PET Motion Correction

This architecture addresses frame-by-frame motion in dynamic positron emission tomography (PET) studies, such as those for myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) with 18F-flurpiridaz or 13N-ammonia [26] [25].

- Data and Ground Truth: The models were trained on multi-site clinical trial data. For each patient study, an experienced operator performed manual frame-by-frame motion correction, and the resulting motion vectors were used as the ground truth [26] [25].

- Network Architecture and Training: The core of the model is a 3D ResNet-based architecture that takes 3D PET volumes as input and outputs motion vectors (tx, ty, tz) representing the translation needed for correction [26] [25].

- Positional Embeddings: In the version for 13N-ammonia, positional encodings were added to provide the model with contextual information about the temporal order of the frames [25].

- Training and Validation: The network was trained to minimize the error between its predicted motion vectors and the ground-truth vectors from manual correction. Robustness was enhanced through data augmentation using simulated motion vectors, and performance was validated via external cross-validation across different clinical sites [26] [25].

Self-Attention for fMRI Slice-to-Volume Registration

This model performs retrospective, slice-level motion correction for functional MRI (fMRI) by registering 2D slices to a 3D reference volume [27].

- Data and Simulation: The model was trained on the publicly available Healthy Brain Network (HBN) dataset. To simulate motion, a wide range of rigid transformations were applied to reference volumes. Slices were then sampled according to a standard acquisition protocol to generate a large dataset of 3D volume-2D slice pairs for training and evaluation [27].

- Network Architecture: The model uses independent encoders for the 2D slice and the 3D reference volume. The core innovation is a self-attention mechanism that assigns a pixel-wise score to each slice. This allows the model to weight the relevance of different slices and focus on the most reliable features for registration, thereby enhancing robustness against input uncertainty and variation [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key computational tools and data components essential for developing motion correction algorithms in this field.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| WGAN-GP (Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty) | Stable training of generative models for tasks like image-to-image translation and artifact correction [17] [24]. | Used as the backbone for ESWGAN-GP; replaces discriminator with a critic, uses Wasserstein distance and gradient penalty for stability [17]. |

| Sobel-Kernel-based CNN (SCNN) | Edge enhancement and preservation in generated images [17] [24]. | Integrated into the U-Net skip connections of the ESWGAN-GP generator to preserve trabecular bone edges [17]. |

| VGG-based Perceptual Loss | Improves reconstruction of high-level, perceptually relevant features and micro-structures [17] [24]. | Used in ESWGAN-GP to complement adversarial and pixel-wise losses [17]. |

| 3D ResNet Architecture | Spatiotemporal feature extraction from 3D volumetric data (e.g., dynamic PET) [26] [25]. | Core network for mapping 3D PET volumes to rigid motion vectors [26]. |

| Positional Encodings/Embeddings | Provides model with contextual information about temporal or spatial order [25]. | Added to 3D-ResNet to inform the model about the frame sequence in dynamic PET [25]. |

| Self-Attention Mechanism | Captures long-range dependencies and spatial relationships in data [17] [27]. | Used in ESWGAN-GP for global features and in fMRI SVR for scoring slice relevance [17] [27]. |

| Paired Dataset (Motion-Corrupted & Ground Truth) | Essential for supervised training of motion correction networks [17] [24]. | Created via sinogram simulation for HR-pQCT [17]; from manual expert correction for PET [26]. |

Workflow and Architecture Diagrams

ESWGAN-GP for Motion Correction

3D-ResNet for PET Motion Correction

Self-Attention for Slice-to-Volume Registration

Generative Adversarial Networks for Motion Artifact Reduction and Image Synthesis

Motion artifacts represent a prevalent source of image degradation in medical imaging, particularly in modalities requiring longer acquisition times such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET). These artifacts arise from both voluntary and involuntary patient movement during scanning, manifesting as blurring, ghosting, or streaking in reconstructed images. In MRI, motion alters the static magnetic field, induces susceptibility artifacts, affects spin history leading to signal loss, and causes inconsistencies in k-space sampling that violate Nyquist criteria [28]. The clinical impact is substantial, with an estimated 15-20% of neuroimaging exams requiring repeat acquisitions, potentially incurring additional annual costs exceeding $300,000 per scanner [28].

Motion correction strategies are broadly classified into two categories: prospective and retrospective methods. Prospective motion correction occurs during image acquisition through techniques like external optical tracking systems, physiologic gating, or sequence-embedded navigators [28]. While effective, these approaches often require hardware modifications, rigid coupling of sensors to anatomy, or increased sequence complexity, limiting their clinical applicability. In contrast, retrospective motion correction operates on already-acquired data without requiring additional hardware, using computational approaches to mitigate artifacts [28]. Recent advances in deep learning, particularly generative adversarial networks (GANs), have revolutionized retrospective correction by learning direct mappings between corrupted and clean images, often yielding improved perceptual quality and reduced reconstruction time compared to conventional iterative algorithms.

Performance Comparison of Motion Correction Algorithms

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Modalities

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Motion Correction Algorithms in Medical Imaging

| Imaging Modality | Correction Method | Network Architecture | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head MRI (T2-weighted) | CGAN | Generator: Autoencoder with Residual blocks & SE; Discriminator: Sequential CNN | SSIM: 0.9+, PSNR: >29 dB | [29] |

| Fetal MRI | GAN with Autoencoder | Generator: Autoencoder with Residual blocks & SE; Discriminator: Sequential CNN | SSIM: 93.7%, PSNR: 33.5 dB | [30] |

| Brain PET (NeuroEXPLORER) | Event-by-event motion correction | MOLAR reconstruction with UMT tracking | Lowest residual SD in TACs | [12] |

| mGRE MRI | LEARN-IMG, LEARN-BIO | Convolutional Neural Networks | Significant artifact reduction, detail preservation | [31] |

| Lung Cancer PET/CT | Data-driven gating with RRA | N/A | SUVmax: +3.9%, Volume: -18.4% | [14] |

| Cone-beam CT | DLME with TriForceNet | Sequential Hybrid Transformer-CNN | Superior to unsupervised and supervised benchmarks | [32] |

Comparative Effectiveness Across Correction Approaches

The quantitative data reveals distinct performance patterns across motion correction approaches. For GAN-based methods applied to MRI, structural similarity index (SSIM) values consistently exceed 0.9, with peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) reaching 33.5 dB in fetal MRI applications [29] [30]. These metrics indicate excellent preservation of structural information and noise reduction capabilities. In PET imaging, event-by-event motion correction using external tracking systems demonstrates superior performance compared to frame-based methods, effectively addressing intraframe motion and achieving the lowest standard deviation in time-activity curves [12]. Data-driven gating approaches in lung cancer PET/CT show substantial improvements in quantification accuracy, with lesion volume reduction of 18.4% and increased standardized uptake values [14].

Notably, GAN-based methods outperform traditional approaches like BM3D, RED-Net, and non-local means filtering across multiple evaluation metrics [30]. The integration of hybrid architectures, such as sequential transformer-CNN designs in cone-beam CT, further extends performance gains by leveraging both local pattern recognition and global dependency modeling [32]. This consistent outperformance highlights the transformative potential of deep learning approaches, particularly GANs, in motion artifact reduction across diverse imaging modalities and anatomical regions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

GAN Architecture Design and Implementation

Table 2: Key Architectural Components in GAN-based Motion Correction

| Component | Variants | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generator | U-Net, Autoencoder with Residual blocks, Encoder-Decoder | Transforms motion-corrupted input to corrected output | Fetal MRI [30], Head MRI [29] |

| Discriminator | Sequential CNN, PatchGAN | Distinguishes between corrected and motion-free images | Head MRI [29], PET/MRI synthesis [33] |

| Loss Functions | WGAN, L1, Perceptual, Combined losses | Guides network training through multiple constraints | Fetal MRI (WGAN + L1 + perceptual) [30] |

| Conditional Input | cGAN, bi-c-GAN | Incorporates additional data to guide generation | Multi-contrast MRI [33] |

| Training Framework | Supervised, Unsupervised, Cycle-consistent | Determines data requirements and training approach | CBCT (unsupervised) [32] |

Dataset Preparation and Training Protocols

Experimental protocols for GAN-based motion correction consistently emphasize rigorous dataset preparation. For head MRI applications, datasets typically comprise thousands of image pairs (5,500 in one study) with simulated motion artifacts generated through Fourier transform modifications of k-space data [29]. These simulations incorporate both translational and rotational motions, with artifacts aligned to phase-encoding directions. Training-validation-test splits generally follow 90%-5%-5% distributions, with pixel value normalization to (0,1) or (0,255) ranges [29].

In fetal MRI implementations, networks are trained on synthetic motion artifacts created through random k-space modifications, with validation on real motion-affected clinical images [30]. This approach addresses the challenge of obtaining paired motion-corrupted and motion-free clinical data. For multi-modal applications like PET/MRI synthesis, bi-task architectures with shared latent representations enable synergistic learning from complementary data sources [33]. Training typically employs combined loss functions incorporating adversarial, structural (SSIM), and intensity (L1/L2) components to balance perceptual quality with quantitative accuracy [30] [33].

Advanced implementations incorporate specialized training strategies. The sequential hybrid transformer-CNN (SeqHTC) in TriForceNet for cone-beam CT combines local feature extraction with global relationship modeling [32]. Multi-resolution heatmap learning and auxiliary segmentation heads further enhance landmark detection accuracy, enabling precise motion parameter estimation without external markers or motion-free references [32].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for GAN-based motion artifact reduction, showing the iterative process from data preparation to model evaluation.

GAN Architectures for Motion Correction

Core Architectural Components and Variations

Generative adversarial networks for motion artifact reduction typically employ encoder-decoder architectures with specialized components tailored to medical imaging challenges. The generator commonly utilizes U-Net or autoencoder structures with skip connections to preserve fine anatomical details [29] [30]. Advanced implementations incorporate residual blocks with squeeze-and-excitation (SE) modules to enhance feature representation and gradient flow [30]. The discriminator typically employs convolutional neural networks, with PatchGAN architectures providing localized discrimination to preserve high-frequency details [29].

Conditional GANs (cGANs) represent a significant advancement, enabling controlled generation through additional input channels. In motion correction, cGANs utilize motion-corrupted images as inputs with motion-free images as targets, learning the specific transformation between these states [29]. For multi-modal applications, bi-c-GAN architectures process complementary inputs like ultra-low-dose PET and T1-weighted MRI to synthesize high-quality PET images, leveraging shared latent representations between tasks [33]. This approach demonstrates the capability of GANs to integrate heterogeneous data sources for enhanced artifact reduction.

Loss Function Design and Optimization

Loss function design critically influences GAN performance in medical applications. Standard approaches combine multiple loss components: adversarial loss (Wasserstein GAN or standard GAN) for realistic output generation; pixel-wise loss (L1 or L2) for intensity fidelity; and perceptual loss for structural preservation [30]. The adversarial component encourages output distributions matching motion-free images, while pixel-wise constraints maintain quantitative accuracy essential for diagnostic applications.

In fetal MRI implementations, weighted combinations of WGAN, L1, and perceptual losses have demonstrated superior performance compared to single-loss alternatives [30]. For multi-modal synthesis, combined losses incorporating mean absolute error, structural similarity, and bias terms effectively balance intensity accuracy with structural preservation [33]. These sophisticated loss functions enable GANs to overcome limitations of conventional approaches, which often produce overly smooth outputs lacking visual authenticity [29].

Diagram 2: GAN architecture for motion artifact reduction showing the adversarial training process between generator and discriminator networks.

Critical Datasets and Software Frameworks

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for GAN-based Motion Correction Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application Context | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | XCAT, CQ500, VSD full body | CBCT motion correction [32] | Provide standardized evaluation benchmarks |

| Simulation Tools | K-space modification, Fourier transform | MRI motion artifact simulation [29] | Generate training data with controlled artifacts |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Network implementation [29] [30] | Enable model development and training |

| Evaluation Metrics | SSIM, PSNR, NRMSE, CNR | Quantitative performance assessment [29] [30] | Provide objective comparison of correction efficacy |

| Motion Tracking Systems | United Healthcare Motion Tracking (UMT) | PET motion correction [12] | Provide ground truth motion data |

Successful implementation of GAN-based motion correction requires careful consideration of computational resources and implementation details. Training typically demands GPU acceleration, with memory requirements scaling with image resolution and batch size. For high-resolution applications, specialized approaches like Diffusion-4K with Scale Consistent Variational Auto-Encoders and wavelet-based latent fine-tuning enable efficient 4K image processing [34]. Data preprocessing pipelines must accommodate domain-specific requirements, including k-space manipulation for MRI [29] [30], sinogram processing for CT [32], and list-mode event handling for PET [12].

Hyperparameter optimization remains challenging, with learning rates, batch sizes, and network depth requiring careful tuning for specific applications. Benchmark studies indicate that GAN-based frameworks like Pix2Pix can outperform diffusion models and flow matching techniques in terms of structural fidelity, image quality, and computational efficiency for certain medical image translation tasks [35]. However, architectural choices must balance computational complexity with performance, particularly for clinical deployment where inference speed may be critical.

Future Directions and Research Challenges

Despite significant advances, GAN-based motion correction faces several persistent challenges. Limited generalizability across scanner platforms, imaging protocols, and patient populations remains a concern [28]. Many approaches rely on paired training data (motion-corrupted and motion-free images from the same subject), which is difficult to obtain in clinical practice [28] [32]. There is also risk of introducing visually plausible but anatomically inaccurate features through over-aggressive correction [28].

Future research directions focus on addressing these limitations through improved data augmentation, unsupervised learning techniques, and domain adaptation methods. For cone-beam CT, unsupervised approaches like Dynamic Landmark Motion Estimation (DLME) eliminate the need for motion-free references by leveraging anatomical landmarks and geometric constraints [32]. In MRI, continued development of comprehensive public datasets and standardized reporting protocols for artifact levels will facilitate more rigorous benchmarking [28]. Architectural innovations, particularly the integration of transformer components with convolutional networks, show promise for capturing long-range dependencies relevant to complex motion patterns [32].

As generative models continue evolving, their application to motion artifact reduction will likely expand beyond simple artifact removal to include integrated acquisition-reconstruction frameworks capable of jointly optimizing data collection and image formation. These advances hold potential to substantially enhance diagnostic accuracy, reduce healthcare costs, and improve patient experience by minimizing repeated scans.

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is an essential imaging tool for patient positioning verification in radiotherapy and for guidance during interventional procedures [36] [37]. However, a significant challenge in acquiring high-quality CBCT images is the degradation caused by physiological motion from breathing, bowel activity, or patient movement [36]. These motion artifacts manifest as blurs or streaks in reconstructed images, compromising diagnostic accuracy and treatment precision [32]. Conventional motion mitigation strategies, such as gating techniques, often assume periodic motion and are consequently restricted to regular respiratory patterns, failing to address irregular, a-periodic motion [36]. This limitation has driven the development of advanced, gate-less reconstruction frameworks capable of correcting for both periodic and non-periodic motion without relying on surrogate signals or extended acquisitions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The CBCT-MOTUS Framework: Core Protocol

The CBCT-MOTUS framework operates on a joint reconstruction principle, simultaneously estimating both the underlying image and the motion-fields. The methodology can be broken down into several key stages [36]:

- Initialization: The process begins with a motion-corrupted image volume, reconstructed from acquired projections without any motion compensation. This initial volume serves as the reference image ( x_0 ).

- Signal Model: The acquired projection data are modeled as line integrals. The relationship between the reference image, the motion-fields, and the measured projections is formalized as: ( yt = At x0[Dt(r)] ) where ( yt ) is the integral signal at time ( t ), ( At ) is the system matrix, ( x0 ) is the reference image, and ( Dt ) is the motion-field that deforms ( x_0 ) to match the object's state at time ( t ) [36].

- Alternating Optimization: The framework iteratively alternates between two steps until convergence:

- Motion Estimation: Motion-fields are estimated directly in the projection space by comparing the acquired projections with simulated projections generated from the motion-deformed reference image. This model-based approach ensures consistency with the raw measurement data.

- Image Correction: The estimated motion-fields are used to compensate for the motion in the image volume, producing an updated, motion-corrected reference image.

- Motion Model Parameterization: To render the high-dimensional motion estimation problem tractable, CBCT-MOTUS incorporates several a priori assumptions:

- B-spline Compression: Motion-fields are compressed using B-spline parameterization, drastically reducing the number of parameters to be estimated [36].

- Low-Rank Model: The spatio-temporal correlation of motion is exploited using a low-rank motion model [36].

- Spatial Regularization: Smoothness of the motion-fields is enforced to include physiological knowledge [36].

This protocol has been validated on in silico datasets, physical phantoms, and clinical in vivo acquisitions, demonstrating its capability to correct for non-rigid motion with a high temporal resolution of 182 ms per projection [36] [38].

Comparator Algorithm Protocols

CAVAREC with Automated Bone Removal (C+Z)

CAVAREC is an iterative motion-compensated reconstruction algorithm designed for clinical CBCT data. Its experimental protocol is as follows [37]:

- Motion Estimation: The algorithm estimates the motion of each projection image relative to a sparse reference image. This reference image is created from the motion-corrupted initial reconstruction by applying a windowing function to focus the motion compensation on high-intensity structures like contrast-enhanced vessels.

- Bone Removal Integration: The proprietary deep-learning algorithm ZIBOS performs automated bone segmentation and removal. By eliminating high-contrast bones from the initial reconstruction, the subsequent windowing in CAVAREC primarily leaves vessels, thereby focusing the motion compensation more effectively on the vasculature of interest [37].

- Validation: A two-center study evaluated this approach on 48 clinical liver CBCTs, using both quantitative vessel sharpness measurements and qualitative reader studies by interventional radiologists for assessment [37].

Dynamic Landmark Motion Estimation (DLME)

DLME is an unsupervised method that relies on anatomical landmark detection rather than external markers or motion-free references [32]:

- Landmark Detection: The core of this method is TriForceNet, a deep learning framework for detecting anatomical landmarks in 2D projection images. It integrates a sequential hybrid transformer-CNN (SeqHTC) encoder, multiresolution heatmap learning, and a multitask learning strategy with an auxiliary segmentation head.

- Motion Estimation: The DLME algorithm uses the geometric relationships between landmarks across different projection views to estimate motion parameters. It incorporates constraints to mitigate high-frequency noise from landmark detection errors and to ensure physically plausible motion trajectories [32].

- Validation: Experiments were conducted on the numerical XCAT phantom, the clinical CQ500 dataset, and the VSD full body dataset, comparing its performance against both unsupervised and supervised motion artifact reduction methods [32].

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from evaluations of the discussed motion correction algorithms.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Motion Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Temporal Resolution | Key Quantitative Outcome | Validation Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBCT-MOTUS [36] | 182 ms/projection | Improved image features, reduction of motion artifacts, and deblurring of organ interfaces. | In silico, phantom, clinical in vivo |

| CAVAREC [37] | Not specified | Vessel sharpness: 0.287 (±0.04), a significant improvement (P=0.02) over uncorrected images (0.281±0.04). | 48 clinical liver CBCTs |

| CAVAREC + ZIBOS (C+Z) [37] | Not specified | Vessel sharpness: 0.284 (±0.04), not significantly different from CAVAREC alone (P>0.05). | 48 clinical liver CBCTs |

| DLME (with TriForceNet) [32] | Not specified | Outperformed traditional unsupervised motion compensation techniques and surpassed supervised, image-based motion artifact reduction methods. | XCAT, CQ500, VSD full body |

Qualitative Clinical Evaluation

In the clinical reader study for CAVAREC, both the algorithm alone and combined with bone removal (C+Z) demonstrated significant qualitative improvements over uncorrected images [37]:

- Overall Image Quality: Scored on a 0-100 scale, both CAVAREC and C+Z significantly improved the mean score from 45 (±14) for uncorrected images to 53 (CAVAREC: ±16; C+Z: ±17), with P < 0.001 [37].

- Specific Image Features: On a scale of -50 to +50 relative to uncorrected images, readers showed a mean preference of +4.3 to +9.5 for CAVAREC and C+Z across parameters like large vessels, small vessels, vessel sharpness, and streak artifacts (P < 0.001). Improvement for tumor blush was not statistically significant [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools in CBCT Motion Correction

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| B-spline Parameterization | Compresses the high-dimensional motion-field data, reducing the number of parameters to be estimated in model-based frameworks like CBCT-MOTUS [36]. |

| Low-Rank Motion Model | Exploits the inherent spatio-temporal correlations in physiological motion, providing a compact representation for efficient computation [36]. |

| Spatial Regularizer | Enforces smoothness in the estimated motion-fields, incorporating a priori knowledge that physical motion is typically continuous and non-abrupt [36]. |

| Deep Learning Landmark Detector (TriForceNet) | Accurately identifies anatomical landmarks in 2D projection images, providing the essential input for unsupervised motion estimation methods like DLME [32]. |

| Sequential Hybrid Transformer-CNN (SeqHTC) | An encoder architecture that combines the local feature extraction power of CNNs with the global context understanding of transformers, improving landmark detection accuracy [32]. |

| Sparse Reference Image | Used in algorithms like CAVAREC; a windowed version of the initial reconstruction that highlights high-contrast structures to guide the motion estimation process [37]. |

| Automated Bone Segmentation (ZIBOS) | A deep-learning-based tool to remove bone structures from reconstructions, potentially focusing motion correction algorithms on soft-tissue vasculature [37]. |

Workflow and Algorithmic Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative workflow of the CBCT-MOTUS framework.

The diagram below maps the taxonomic relationships between different algorithmic approaches to the motion correction problem in CBCT, highlighting the position of CBCT-MOTUS.

The comparative analysis of gate-less motion correction frameworks reveals distinct advantages and potential applications for each approach. CBCT-MOTUS represents a principled, model-based approach that achieves high temporal resolution and effectively handles both periodic and irregular, non-rigid motion without external surrogates [36]. Its strength lies in its direct physical model and data consistency, providing a transparent and understandable correction process. The CAVAREC algorithm, particularly in a clinical interventional setting, demonstrates significant and reliable improvement in image quality for hepatic vasculature visualization, with the added finding that automated bone removal does not degrade this performance [37]. This integration can be streamlined into clinical workflows. The DLME method offers a powerful alternative by leveraging advanced deep learning for landmark detection, eliminating the need for paired motion-free data and avoiding the marker-based methods' logistical hurdles [32].

In conclusion, the evolution of motion correction in CBCT is advancing toward more flexible, gate-less frameworks that can cope with the complexities of physiological motion. CBCT-MOTUS, with its foundation in low-rank motion models and model-based reconstruction, establishes a strong benchmark for performance, particularly in applications requiring high temporal fidelity and correction of a-periodic motion. The ongoing integration of deep learning components, as seen in landmark detection and bone removal, promises to further enhance the robustness and clinical applicability of these technologies, ultimately improving the precision of radiotherapy and interventional oncology procedures.

This guide provides an objective comparison of traditional signal processing techniques—Wavelet Transform, Principal Component Analysis, and Correlation-Based Methods—framed within research on motion correction algorithms. The performance data and methodologies summarized are crucial for researchers and scientists selecting appropriate techniques for medical imaging and signal processing applications.

Experimental Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize quantitative performance data for the featured techniques from controlled experiments.

Table 1: Performance in Lightning Stroke Classification on Transmission Lines [39]

| Technique | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Classification Accuracy with ANN | Key Metric Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|