Motion Sensitivity in MRI Pulse Sequences: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

This article provides a systematic comparison of motion sensitivity across various MRI pulse sequences, a critical consideration for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical research.

Motion Sensitivity in MRI Pulse Sequences: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of motion sensitivity across various MRI pulse sequences, a critical consideration for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical research. It explores the fundamental physical principles behind motion artifacts, details advanced methodological corrections like navigator echoes and prospective motion correction, and offers a practical troubleshooting guide for optimizing protocols. The content further synthesizes validation strategies and comparative performance metrics across sequences such as T2*-GRE, EPI, ZTE, and SSFP, providing an evidence-based framework for selecting the most motion-robust techniques in sensitive imaging scenarios.

The Physics of Motion Artifacts: Why MRI is Sensitive and How Artifacts Manifest

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a powerful non-invasive imaging modality, but its data acquisition process is inherently slow, making it highly sensitive to patient motion. Unlike photographic imaging, where motion causes localized blurring, motion in MRI can corrupt the entire image because data are acquired sequentially in the spatial frequency domain (k-space), not directly in image space [1] [2]. The appearance of motion artifacts is a complex interplay between the type and timing of patient movement and the specific k-space sampling strategy employed by the pulse sequence [1]. Understanding these fundamental k-space principles is crucial for selecting appropriate imaging sequences, developing effective motion correction strategies, and accurately interpreting clinical and research images.

This review examines how motion corrupts MR image formation through the lens of k-space physics, providing a comparative analysis of motion sensitivity across different pulse sequences. We synthesize experimental data and theoretical frameworks to offer researchers and imaging scientists a foundation for optimizing acquisition protocols in motion-prone scenarios, particularly in populations such as pediatric, elderly, or neurologically impaired patients where motion control is challenging.

K-Space Fundamentals and Motion Physics

The Relationship Between K-Space and Image Quality

In MRI, spatial encoding is achieved through the sequential acquisition of data in k-space, the spatial frequency domain of the image. Each sample in k-space contains information about the spatial frequencies that compose the entire image; consequently, inconsistencies in k-space data affect the whole image rather than localized regions [1] [2]. The center of k-space (low spatial frequencies) determines overall image contrast and signal-to-noise ratio, while the periphery (high spatial frequencies) defines edge detail and resolution. This global nature of k-space encoding explains why motion during MRI acquisition can have such devastating effects on image quality compared to other imaging modalities.

Physical Mechanisms of Motion Artifacts

Motion during MRI acquisition causes inconsistencies in the k-space data, violating the fundamental assumption of a stationary object during Fourier reconstruction. The specific manifestation of artifacts depends on both the nature of the motion (translation, rotation, periodic, sudden) and the k-space trajectory used for acquisition [1].

- Translational motion produces a linear phase shift in k-space [2].

- Object rotation causes a corresponding rotation of the k-space data [2].

- Periodic motion (e.g., respiration, cardiac pulsation) results in coherent ghosting artifacts where the moving structure is replicated at regular intervals across the image [1].

- Sudden, non-periodic movements cause more complex signal modulations that lead to incoherent ghosting and general image degradation [1].

The timing of motion relative to k-space acquisition is critical. Movements occurring near the k-space center (low frequencies) tend to cause ghosting artifacts, while motions toward the k-space periphery (high frequencies) typically produce blurring and edge degradation [3].

K-Space Trajectories and Motion Sensitivity

The k-space sampling trajectory fundamentally determines how motion artifacts manifest in the final image. The most common trajectories used in clinical and research MRI are Cartesian and radial sampling, each with distinct motion sensitivity profiles.

Cartesian Sampling and Ghosting Artifacts

Cartesian sampling acquires k-space data along rectilinear grid lines, typically proceeding line-by-line in the phase-encoding direction. This approach allows computationally efficient reconstruction using the Fast Fourier Transform but creates specific vulnerabilities to motion [1]. With Cartesian sampling, motion causes inconsistencies between different phase-encoding lines, resulting in ghosting artifacts that appear as replicated structures along the phase-encoding direction [2]. The appearance of these ghosts depends on motion characteristics: periodic motion produces coherent, discrete ghosts, while random motion creates more diffuse, incoherent ghosting throughout the image [1].

Radial Sampling and Motion Robustness

Radial sampling (e.g., stack-of-stars) acquires k-space data along projections passing through the k-space center at different angles. This approach offers inherent motion robustness through two key mechanisms: oversampling of the k-space center and incoherent artifact distribution [4] [2]. Since each radial view passes through the center of k-space, motion effects are distributed throughout the image as noise-like artifacts or blurring rather than structured ghosting [2]. This generally makes radial sampling more tolerant to motion compared to Cartesian trajectories, though at the potential cost of more complex reconstruction requirements [4].

Table: Comparative Characteristics of K-Space Trajectories Regarding Motion Sensitivity

| Feature | Cartesian Sampling | Radial Sampling (e.g., Stack-of-Stars) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Motion Artifact | Structured ghosting along phase-encoding direction | Diffuse blurring or streaking artifacts |

| Motion Artifact Appearance | Discrete replicas of moving structures | Noise-like artifacts distributed throughout image |

| Central K-Space Sampling | Once per TR period | Every single projection |

| Inconsistency Impact | Affects specific phase-encoding lines | Distributed across all projections |

| Reconstruction Method | Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) | Filtered back-projection or iterative methods |

| Computational Efficiency | High | Moderate to high |

Comparative Analysis of Pulse Sequence Motion Resilience

Experimental studies directly comparing different pulse sequences provide valuable insights into their relative motion robustness and diagnostic performance in clinical scenarios.

Cartesian MPRAGE vs. Radial Stack-of-Stars Sequence

A prospective, two-center observational study directly compared the standard magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence with a motion-resistant radial stack-of-stars (SOS) echo-unbalanced T1 relaxation-enhanced steady-state (SOS echo-uT1RESS) sequence in brain tumor imaging [4]. The study enrolled 34 adult patients with known brain tumors and evaluated both sequences for overall image quality, lesion conspicuity, and image artifacts using a 4-point Likert scale assessed by three blinded fellowship-trained neuroradiologists [4].

Table: Quantitative Comparison of MPRAGE and SOS echo-uT1RESS in Brain Tumor Imaging

| Performance Metric | MPRAGE | SOS echo-uT1RESS | Statistical Significance | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) | 29.4 ± 21.4 | 28.2 ± 16.5 | p = 0.80 | r = 0.03 |

| Tumor-to-Brain Contrast | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | p < 0.001 | r = 0.81 |

| Lesion Conspicuity | Reference | Significantly improved | p < 0.001 | r = 0.51 |

| Overall Image Quality | Comparable | Comparable | Not significant | - |

| Image Artifacts | Comparable | Comparable | Not significant | - |

| Diagnostic Performance | Reference | Significantly improved | p < 0.001 | r = 0.53 |

| Scan Time | 4 minutes 52 seconds | 6 minutes 51 seconds | - | - |

The SOS echo-uT1RESS sequence demonstrated a 1.8-fold improvement in tumor-to-brain contrast while maintaining comparable overall image quality and artifact levels [4]. This sequence was particularly effective for visualizing small metastases, attributable to its motion-resistant stack-of-stars acquisition and inherent dark-blood effect that suppresses background tissue signal while preserving gadolinium-enhancing lesion visibility [4].

Zero Echo Time (ZTE) Sequence for Motion-Resistant Osseous Imaging

Zero Echo Time (ZTE) sequences represent another approach to motion resilience by virtually eliminating the delay between excitation and signal readout. A recent study evaluated ZTE MRI for assessing osseous and cartilage changes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint, demonstrating its superior performance for bony abnormality detection compared to conventional proton density with fat suppression (PD-FS) sequences [5]. For osseous changes, ZTE achieved sensitivity of 91.5-92.3% and accuracy of 92.2-93.8% across readers, outperforming PD-FS (sensitivity: 85.9-87.2%, accuracy: 86.1-88.6%) [5]. This enhanced performance for bony structures, combined with ZTE's inherent motion tolerance due to extremely short echo times, makes it valuable for musculoskeletal and other motion-prone applications.

Advanced Motion Correction Methodologies

Physics-Based Modeling and Deep Learning Approaches

Traditional motion correction techniques have included prospective methods (such as navigator echoes and external tracking systems) and retrospective methods (such as post-processing algorithms) [1]. Recently, hybrid approaches combining physics-based modeling with deep learning have shown significant promise. MIT researchers have developed a deep learning model that computationally constructs motion-free images from motion-corrupted data without altering the scanning procedure [6]. This method enforces data consistency between the reconstructed image and the actual acquired measurements, avoiding the creation of physically inaccurate "hallucinations" that could lead to misdiagnosis [6]. Such approaches are particularly valuable for populations prone to motion, including children and patients with neurological disorders causing involuntary movement.

K-Space Motion Modeling for Data Augmentation

A sophisticated k-space motion model has been developed to generate realistic motion artifacts from artifact-free MRI data for deep learning frameworks [3]. This approach models patient movement as a sequence of rigid 3D affine transforms, resamples artifact-free volumes according to a "demeaned" movement model, and combines these in k-space to create motion-corrupted training data [3]. By augmenting training datasets with these physically realistic artifacts, convolutional neural networks can be trained to perform more reliably on real-world motion-affected data, with segmentation models that generalize better and provide uncertainty measures reflective of artifact presence [3].

Experimental Protocols for Motion Sensitivity Assessment

Quantitative Motion Artifact Characterization

Robust assessment of sequence motion sensitivity requires standardized experimental protocols. Quantitative analysis typically includes region-of-interest (ROI) measurements of signal intensity in enhancing lesions, normal white matter, and background air to calculate objective metrics [4]. The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) is calculated as CNR = (SItumor - SIWM) / SDair, where SItumor and SIWM are signal intensities in tumor and white matter, respectively, and SDair is the standard deviation of background air signal [4]. Weber contrast (also referred to as tumor-to-brain contrast) provides a complementary metric calculated as (SItumor - SIWM) / SI_WM, offering a measure of lesion visibility independent of background noise [4].

Qualitative Image Assessment Framework

Qualitative assessment by expert readers provides essential clinical context to quantitative metrics. Standardized protocols typically employ Likert scales (commonly 4-point or 5-point) evaluated by multiple blinded readers to assess parameters including [4] [5]:

- Overall image quality: Diagnostic acceptability and general image clarity

- Lesion conspicuity: Visibility and demarcation of pathological findings

- Image artifacts: Presence and severity of motion-related and other artifacts

- Anatomical detail: Clarity of specific structural features relevant to diagnostic tasks

Inter-reader reliability should be assessed using statistical measures such as Cohen's kappa, with values interpreted according to established guidelines (e.g., <0.20 slight agreement; 0.21-0.40 fair; 0.41-0.60 moderate; 0.61-0.80 substantial; 0.81-1.00 almost perfect) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Solutions for MRI Motion Artifact Investigation

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 3T MRI Systems | High-field platforms providing signal-to-noise ratio necessary for advanced sequence development | Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra systems used in SOS echo-uT1RESS validation [4] |

| Radial k-Space Trajectories | Motion-robust acquisition schemes that distribute artifacts incoherently | Stack-of-stars sampling with golden view angle rotation [4] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Hybrid physics-AI models for motion correction and artifact reduction | Data-consistent rigid motion correction combining physical models with convolutional neural networks [6] |

| Synthetic MRI Phantoms | Digital and physical phantoms for controlled motion artifact simulation | Modified Shepp-Logan phantom with added grid structures for motion simulation [1] |

| Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents | Enhancement of lesion visibility for quantitative contrast assessment | Gadobutrol (Gadavist) at 0.1 mmol/kg dosage [4] |

| K-Space Motion Models | Generation of realistic motion artifacts for algorithm training and validation | Sequence of demeaned rigid 3D affine transforms combined in k-space [3] |

| Parallel Imaging Algorithms | Acceleration techniques requiring specialized artifact mitigation | SENSE (SENSitivity Encoding) and GRAPPA (GeneRalized Autocalibrating Partially Parallel Acquisitions) [7] [8] |

Motion artifacts remain a significant challenge in MRI, but understanding their origins in k-space physics enables more effective mitigation strategies. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that k-space trajectory selection profoundly impacts motion sensitivity, with radial approaches like stack-of-stars sampling offering inherent robustness through incoherent artifact distribution. Advanced reconstruction methods combining physical models with deep learning show promise for next-generation motion correction without protocol modifications. As MRI continues to expand into challenging populations and applications, these motion-resistant strategies will play an increasingly vital role in maintaining diagnostic image quality and quantitative accuracy across diverse clinical and research scenarios.

Motion artefacts are a significant challenge in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), arising when the object being imaged moves during the data acquisition process. These artefacts manifest primarily as blurring, ghosting, and signal loss, which can degrade image quality and compromise diagnostic accuracy [9] [1]. Understanding and classifying these artefacts is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies, particularly when comparing the motion sensitivity of different MRI pulse sequences. The appearance and severity of these artefacts are influenced by a complex interaction between the type of motion, the specific pulse sequence used, and the k-space sampling strategy [1]. This guide provides a systematic classification of motion artefacts and an objective comparison of how different pulse sequences perform in their presence, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to research in the field.

Fundamental Physics and Classification of Motion Artefacts

The primary source of motion artefacts in MRI lies in the discrepancy between the assumption of a stationary object during image acquisition and the reality of patient or physiological movement. Spatial encoding in MRI is a sequential process that occurs in Fourier space (k-space), and any motion during this encoding leads to inconsistencies in the acquired data [1].

K-Space and the Impact of Motion

K-space represents the spatial frequency spectrum of the imaged object. During a Cartesian acquisition, k-space is filled line by line, with each line representing a specific phase encoding step. Motion during this process violates the fundamental assumption of a static object, leading to data inconsistencies that manifest as artefacts after Fourier transformation [1]. The effect of motion depends critically on its timing relative to the k-space acquisition order. Slow, continuous motion (e.g., muscle relaxation) may cause simple blurring, while periodic motion (e.g., respiration, cardiac pulsation) typically results in coherent ghosting artefacts. Sudden, abrupt motion can cause severe ghosting and signal loss [1].

A Triad of Artefacts: Blurring, Ghosting, and Signal Loss

Motion-induced artefacts in MRI can be categorized into three principal types, each with distinct appearances and underlying causes.

Blurring: This artefact presents as a loss of sharpness in image details and edges, making structures appear out of focus. It is intuitively similar to the blurring observed in photography when the subject moves during exposure [1]. Blurring occurs when there is continuous, non-periodic motion throughout the k-space acquisition, effectively smearing the spatial information.

Ghosting: Ghosting appears as replicated, semi-transparent images of a moving structure displaced along the phase-encoding direction in the final image [9] [10]. These "ghosts" can be coherent (sharp replicas) or incoherent (smeared stripes), depending on the periodicity of the motion. Coherent ghosting results from periodic motion synchronized with the sequence repetition, such as cardiac pulsation, while incoherent ghosting arises from non-periodic movements [1]. The American College of Radiology (ACR) has a standardized metric for quantifying this artefact, termed "Percent Signal Ghosting" [10].

Signal Loss: This artefact involves a localized reduction or complete absence of signal from moving tissues. It is primarily caused by spin dephasing within a voxel or the movement of excited spins out of the imaging slice between excitation and readout [1] [11]. Signal loss is particularly problematic in gradient-echo sequences and in imaging scenarios involving turbulent flow or rapid, complex motion.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, causes, and common manifestations of these three primary motion artefacts.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Primary MRI Motion Artefacts

| Artefact Type | Visual Manifestation | Primary Cause | Common Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blurring | Loss of sharpness, smeared edges [1] | Continuous, non-periodic motion during acquisition [1] | Patient drifting, slow muscular relaxation [1] |

| Ghosting | Replicated images of moving structure along phase-encoding direction [9] [1] | Periodic or abrupt motion causing k-space inconsistency [9] [1] | Respiration, cardiac pulsation, swallowing [9] [11] |

| Signal Loss | Localized signal reduction or void [1] | Spin dephasing or movement of spins out of imaging slice [1] [11] | Turbulent blood flow, abdominal peristalsis [1] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between different types of patient motion and the resulting primary artefacts.

Diagram 1: Relationship between motion types and resulting artefacts.

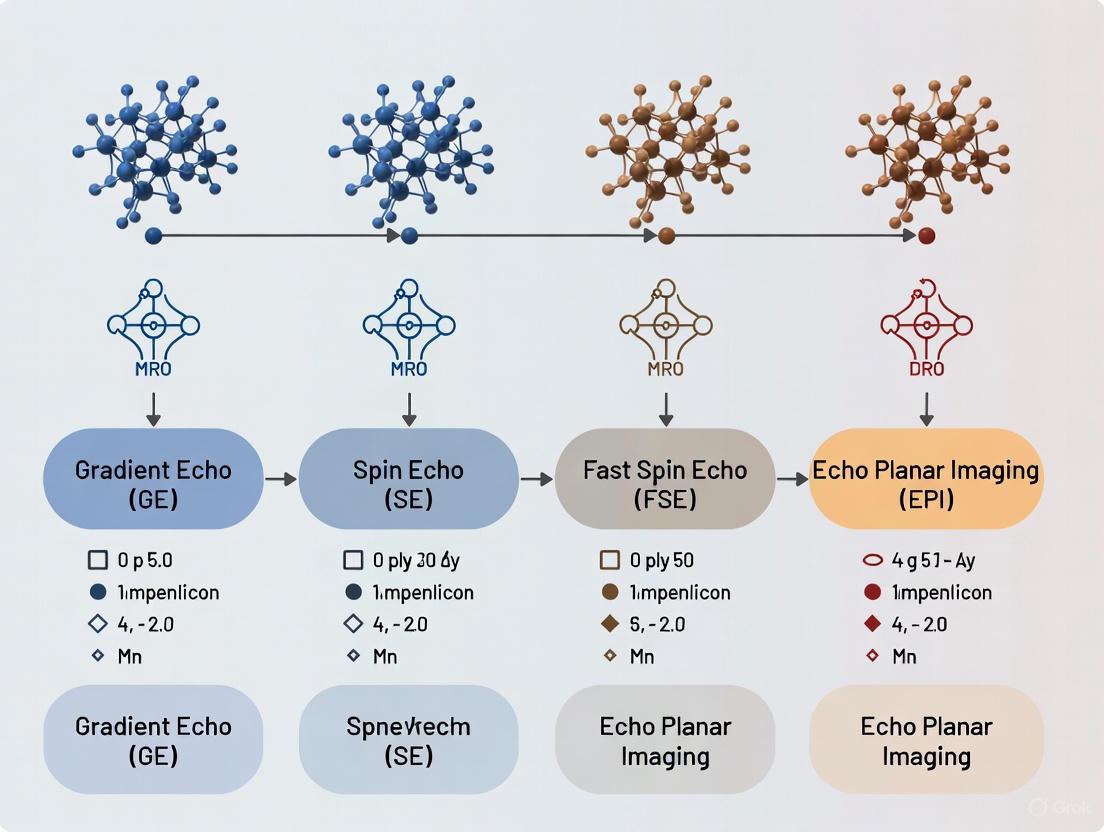

Motion Sensitivity Comparison Across Pulse Sequences

The sensitivity of an MRI examination to motion is heavily dependent on the choice of pulse sequence. Sequences vary in their acquisition speed, k-space trajectory, and inherent contrast mechanisms, leading to significant differences in their vulnerability to and manifestation of motion artefacts.

The table below provides a comparative overview of common MRI pulse sequences, focusing on their relative motion sensitivity and the typical artefacts they produce.

Table 2: Motion Sensitivity and Typical Artefacts Across MRI Pulse Sequences

| Pulse Sequence | Relative Acquisition Speed | Primary Motion Artefacts | Inherent Motion Robustness | Key Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Spin Echo (CSE) | Slow | Significant ghosting and blurring [1] | Low | Standard T1 and T2 weighting; highly sensitive to motion [12] |

| Fast/Turbo Spin Echo (FSE/TSE) | Moderate | Ghosting (especially with interleaved acquisition) [1] | Moderate | Faster than CSE; but interleaving can increase ghosting from slow motion [1] |

| Single-Shot FSE (e.g., SSFSE, HASTE) | Very Fast | Minimal ghosting, some blurring [13] | High | Abdominal imaging, uncooperative patients; acquires all k-space lines in one TR [13] |

| Gradient Echo (GRE) | Fast to Moderate | Signal loss, severe ghosting [9] | Low | Dynamic contrast-enhanced, abdominal, cardiac; sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneity [9] |

| Echo-Planar Imaging (EPI) | Very Fast | N/2 ghosting, geometric distortion [9] | Moderate (for speed) | fMRI, DWI; very fast but prone to specific ghosting and susceptibility artefacts [9] [14] |

| Radial (e.g., BLADE, PROPELLER) | Moderate | Reduced ghosting, streaking artefacts possible [9] [15] | High | Motion-prone environments; oversamples k-space center, blurring instead of ghosting [9] [15] |

Experimental Data from Sequence Comparisons

Quantitative studies provide evidence for the performance differences outlined above. A study comparing sequences for cervical spinal cord imaging found that Short-Tau Inversion-Recovery Fast Spin-Echo (STIR-FSE) demonstrated a significantly higher contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) for demyelinating lesions compared to both Conventional Spin-Echo (CSE) and standard FSE [16]. Furthermore, STIR-FSE images revealed a significantly higher number of lesions in patients with multiple sclerosis, with additional lesions identified in 9 out of 30 patients [16]. This indicates that sequence choice not only affects artefact burden but also directly impacts diagnostic sensitivity.

In abdominal imaging, where respiratory motion is a major concern, radial k-space sampling techniques (e.g., "stack-of-stars" with golden-angle profiling) have been shown to provide higher motion robustness and greater protocol flexibility compared to conventional Cartesian sampling [15]. These techniques achieve this by continuously sampling the center of k-space, which contains the most important image contrast information, making them less susceptible to producing discrete ghost artefacts from motion [9] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Artefact Assessment

Robust experimental design is essential for objectively evaluating motion sensitivity and the efficacy of correction algorithms. The following protocols outline standardized methodologies for such assessments.

Simulation-Based Evaluation of Susceptibility and Motion

Computational simulation offers a ground-truth approach for quantitative evaluation. The POSSUM (Physics-Oriented Simulated Scanner) MR simulator, combined with a diffusion-weighted imaging framework, can generate realistic datasets with known motion and artefact parameters [14].

Protocol: Simulating Dynamic Susceptibility Artefacts

- Input Generation: Create a digital object from a brain segmentation of high-resolution T1- and T2-weighted structural images [14].

- Motion and Field Modelling: Define motion parameters (e.g., translation, rotation) and a map of magnetic field inhomogeneities (B0 fieldmap) to simulate the susceptibility-induced off-resonance field [14].

- Data Synthesis: Use the simulator to solve Bloch's and Maxwell's equations, generating complex k-space data for a specified pulse sequence (e.g., Spin-Echo EPI). The simulator outputs the distorted DW-MR data and a ground-truth displacement field mapping the geometric distortions [14].

- Correction and Validation: Apply the correction method under evaluation (e.g., fieldmap-based, reverse phase-encode). Quantify performance by comparing the method's estimated displacement field against the simulator's ground truth, measuring the ability to correct geometry and recover signal in compressed regions [14].

Phantom-Based Quantification of Ghosting

The American College of Radiology (ACR) provides a standardized phantom test for quality control, which includes a metric for quantifying ghosting artefacts [10].

Protocol: ACR Percent Signal Ghosting Measurement

- Phantom Imaging: Acquire images of the large ACR MRI phantom using the sequence and parameters to be assessed.

- Region of Interest (ROI) Analysis: Measure the mean pixel intensity in five predefined ROIs [10]:

- S: A large central area within the phantom.

- T, B, L, R: Four regions placed in the air outside the phantom, located at the top, bottom, left, and right edges of the image.

- Calculation: Compute the Percent Signal Ghosting (G) using the formula: G = | (T + B) - (L + R) | / (2 × S) [10]. A result of less than 0.025–0.03 (2.5–3%) is typically considered acceptable, though specific thresholds may vary [10].

The workflow for a comprehensive motion artefact experiment, from setup to data analysis, is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for motion artefact assessment experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details key methodological "reagents" – essential techniques, algorithms, and hardware – used in the study and mitigation of MRI motion artefacts.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Motion Artefact Investigation

| Research Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Application in Motion Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| POSSUM Simulator | Software Tool | Generates realistic MRI data with a known ground truth by solving physical equations [14] | Gold-standard validation for correction algorithms; isolates motion/susceptibility effects from other confounds [14] |

| Respiratory Gating/Triggering | Hardware/Software | Controls data acquisition based on respiratory cycle, e.g., using bellows or navigator echoes [9] [15] | Reduces respiratory ghosting in abdominal/chest imaging; enables free-breathing studies with predictable motion [9] [15] |

| Radial/Propeller k-Space | Pulse Sequence | Samples k-space in a radial or blade-like pattern, oversampling the center [9] [15] | Mitigates ghosting by transforming discrete ghosts into diffuse blurring; basis for advanced motion-robust sequences [9] [15] |

| Parallel Imaging (SENSE, GRAPPA) | Acceleration | Reduces acquisition time by undersampling k-space using coil sensitivity maps [13] | Shortens scan time to reduce motion occurrence; can be combined with other techniques like compressed sensing [9] [13] |

| Deep Learning (Generative Models) | Algorithm | AI-driven detection and correction of motion artefacts in image or k-space domain [17] | Post-processing correction; shows promise for improving image quality but faces challenges in generalizability [17] |

| Navigator Echoes | Pulse Sequence | Measures the position of an organ boundary (e.g., the diaphragm) in real-time during acquisition [9] | Provides data for prospective or retrospective motion correction without external hardware [9] |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pulse sequences employ distinct k-space sampling trajectories, each with unique characteristics that determine their vulnerability to specific artifacts. The spin warp (Cartesian) technique, echo planar imaging (EPI), and radial trajectories represent three fundamental approaches with differing resilience to common MRI challenges including off-resonance effects, motion, and hardware imperfections [18] [19]. Understanding these intrinsic vulnerabilities is crucial for selecting appropriate sequences in both clinical and research settings, particularly for applications requiring high temporal resolution or encountering significant magnetic field inhomogeneities [20].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three trajectory classes, focusing on their performance characteristics, artifact susceptibility, and optimal application domains. We synthesize experimental data from recent studies to deliver evidence-based recommendations for researchers and drug development professionals working with advanced MRI methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Key Performance Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of intrinsic sequence vulnerabilities

| Performance Metric | Spin Warp (Cartesian) | Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) | Radial Trajectories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-resonance sensitivity | Low (spatial shifts only) [19] | High (severe distortion & signal loss) [19] [21] | Medium (blurring artifacts) [19] |

| Motion artifact resilience | Low (ghosting along phase-encode) [22] | Low to Medium (severe ghosting) [22] | High (streaking artifacts, central k-space oversampling) [23] [21] |

| Temporal resolution potential | Low to Medium | Very High (single-shot acquisition) [20] | Medium to High [20] |

| Susceptibility artifact resilience | Low | Low [21] | High [21] |

| Typical acceleration compatibility | SENSE, GRAPPA [20] | SENSE, GRAPPA, Multi-band [20] [24] | Parallel imaging, compressed sensing [20] |

| Common reconstruction method | Direct FFT [23] | FFT with correction [19] | Gridding or Polar FT [23] |

Table 2: Experimental geometric distortion measurements near metal implants (adapted from Kim et al. 2022)

| Sequence Type | Specific Sequence | Distortion Near Clip (mm) | Artifact Length (mm) | Image Quality Score (1-4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spin Warp | RESOLVE DWI | Moderate | Moderate | 2.8 |

| EPI | SS-EPI DWI | Severe | Large | 1.9 |

| Radial | TGSE-BLADE DWI | Minimal | Smallest | 3.5 |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Data

Phantom and In Vivo Validation of Distortion Artifacts

Recent experimental studies provide quantitative validation of the intrinsic vulnerabilities summarized above. Kim et al. (2022) conducted a systematic comparison using a phantom with an embedded aneurysm clip and in vivo measurements in both healthy volunteers and post-neurosurgical patients [21]. Their methodology involved:

- Phantom design: A cylindrical container filled with agarose gel with a centrally embedded titanium aneurysm clip

- Participant cohort: 17 healthy volunteers and 20 patients with cerebral aneurysm clips

- Scan parameters: All sequences performed on 3T scanners (Siemens Skyra or Prisma) with comparable resolution and diffusion weighting

- Quantitative analysis: Measurement of geometric distortion at air-tissue interfaces (temporal tip, frontal sinus, cerebellum near mastoid) and near metallic implants

- Qualitative assessment: Expert radiologist scoring of geometric distortion, susceptibility artifacts, and overall image quality using a 4-point Likert scale

The results demonstrated significantly reduced distortion in radial TGSE-BLADE DWI compared to both readout-segmented spin warp (RESOLVE) and single-shot EPI sequences, particularly near susceptibility interfaces (P < 0.001) [21].

Motion Artifact Characterization Protocol

The motion resilience of radial sequences has been quantitatively evaluated through:

- Volunteer studies: Scanning healthy subjects instructed to perform deliberate head motion during acquisition

- Quantitative metrics: Displacement measurements between reference T2-weighted images and DWIs, signal variation analysis in uniform tissue regions

- PSF analysis: Evaluation of how undersampling artifacts manifest differently across trajectories [23]

These experiments consistently demonstrate that radial sampling concentrates undersampling artifacts as background noise rather than structured ghosts, with preserved central resolution making it particularly suitable for focused region-of-interest imaging [23].

Visualization of K-Space Properties and Artifact Mechanisms

This diagram illustrates how fundamental k-space sampling properties dictate characteristic artifact patterns for each trajectory class. The relationship between acquisition strategy and resulting artifacts demonstrates why each sequence exhibits distinct vulnerability profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for trajectory studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Imaging | SENSE, GRAPPA [20] | Acceleration by exploiting multi-channel arrays | Clinical acceleration rates typically 4×; higher factors increase noise [20] |

| Reconstruction Frameworks | Gadgetron, ICE [20] [23] | Open-source platforms for advanced reconstruction | GPU acceleration crucial for non-Cartesian real-time applications [20] |

| Non-Cartesian Reconstruction | Gridding, Polar Fourier Transform [23] | Direct reconstruction of radial data | PFT preserves central resolution but has longer computation time [23] |

| Motion Correction | Prospective motion correction, navigators [22] | Rigid-body motion detection and compensation | Optical tracking provides high temporal resolution for prospective correction [22] |

| Multi-band Excitation | CMRR MB-EPI sequences [24] | Simultaneous multi-slice acceleration | Reduces scan time but increases g-factor noise penalty [24] |

| Field Monitoring | Field camera systems [25] | Monitoring gradient field imperfections | Essential for high-resolution non-Cartesian imaging [25] |

Discussion and Clinical Translation

The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that sequence selection involves inherent trade-offs between different types of vulnerability. No single trajectory excels across all performance metrics, necessitating careful matching of sequence properties to specific application requirements [20] [21].

For neuroimaging applications requiring minimal distortion near susceptibility interfaces (e.g., postoperative imaging, brainstem studies), radial techniques like TGSE-BLADE provide superior performance despite potentially longer reconstruction times [21]. When maximum temporal resolution is paramount (e.g., fMRI, dynamic contrast studies), EPI remains the preferred choice despite its vulnerability to off-resonance artifacts [20] [26]. Conventional spin warp sequences offer the advantage of robust, straightforward reconstruction with predictable artifact patterns, making them suitable for standard anatomical imaging when motion can be controlled [19].

Future directions in trajectory development focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different sampling patterns. The tilted hexagonal sampling (T-Hex) method, for instance, provides flexible k-space segmentation that can be combined with either spiral or EPI readouts to optimize timing parameters for specific contrast and resolution requirements [25]. Similarly, advanced reconstruction techniques including compressed sensing and deep learning are increasingly being applied to mitigate the intrinsic vulnerabilities of each trajectory type [27].

For drug development professionals utilizing MRI as a biomarker, this comparative analysis supports informed sequence selection based on the specific tissue targets and potential confounding factors in their experimental models. The tabulated performance metrics provide a practical reference for protocol optimization in preclinical and clinical trial settings.

In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), patient motion presents a dual challenge. The first component is the physical movement of the object within the imaging coordinate system. The second, more complex component is the alteration of the main magnetic field (B0) induced by this motion. Even minor head pose changes can cause substantial and spatially complex B0 field changes in the brain. For rotations and translations of approximately 5° and 5 mm at 7 Tesla, the subject-induced field component alone generates a resonance frequency shift over the brain with a standard deviation of about 10 Hz [28]. These field changes lead to image-corrupting phase errors, particularly problematic in multi-shot T2*-weighted acquisitions and advanced techniques like chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI, where signal effects are often only a few percent of the water signal [28] [29].

The complexity arises because motion-induced B0 changes have multiple sources. The total field (TF) experienced by spins in the brain changes with head pose due to: (1) the external field (EF) from the main magnet and shim coils, and (2) the subject's field (SF) from the subject's own inhomogeneous magnetization, which includes contributions from both the head and the stationary torso [28]. Understanding these sources is crucial for developing effective correction strategies, as motion-related artifacts can severely impact diagnostic quality and confound research findings, even mimicking pathological changes such as cortical atrophy [30].

Quantitative Comparison of Motion Sensitivity Across MRI Pulse Sequences

Different MRI pulse sequences exhibit varying sensitivity to motion and B0 field fluctuations. The following table summarizes experimental performance data for several sequence types in the context of motion corruption.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of MRI Sequences Under Motion Conditions

| Sequence Type | Key Motion Mitigation Feature | Reported Performance Metric | Quantitative Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial MultiVane XD (MVXD) [31] | PROPELLER-based radial sampling with parallel imaging | Urethral visibility score (1-5 scale) | Significantly higher (4.09 ± 0.15) vs. SSFSE (2.95 ± 0.22); P < 0.0001 [31] | Prostate MRI simulation, 3T, n=22 patients |

| Cartesian Single-Shot Fast Spin-Echo (SSFSE) [31] | Rapid single-shot acquisition | Urethral visibility score (1-5 scale) | 2.95 ± 0.22 [31] | Prostate MRI simulation, 3T, n=22 patients |

| Stack-of-Stars echo-uT1RESS [4] | 3D radial (SOS) k-space trajectory | Tumor-to-brain contrast | 1.8-fold improvement vs. MPRAGE (0.7 ± 0.4 vs. 0.4 ± 0.3; p < 0.001) [4] | Brain tumor imaging, 3T, n=34 patients |

| MPRAGE (Cartesian) [4] | Standard Cartesian sampling | Tumor-to-brain contrast | 0.4 ± 0.3 [4] | Brain tumor imaging, 3T, n=34 patients |

| Standard Cartesian T2*-weighted [28] | Multi-shot acquisition for high resolution | B0 change from 5°/5mm motion | Standard deviation of ~10 Hz in resonance frequency over the brain at 7T [28] | B0 field mapping, 7T, n=5 volunteers |

The data reveal a clear performance trend favoring non-Cartesian k-space trajectories. Radial sampling techniques (MultiVane XD and Stack-of-Stars) demonstrate superior motion robustness and improved visualization of anatomical structures compared to their Cartesian counterparts. The MVXD sequence maintained high image quality despite generating more artifacts, as these artifacts tended to appear in the periphery without obscuring the region of interest [31]. The SOS echo-uT1RESS sequence achieved significantly better lesion conspicuity for brain tumors while maintaining comparable overall image quality, making it a promising motion-robust alternative for diagnostic imaging [4].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Motion and B0 Field Effects

Protocol 1: B0 Field Change Quantification During Head Motion

This protocol, adapted from a 7 Tesla study, systematically measures how head motion alters the B0 field [28].

- Subject Preparation: Participants are instructed to move their head to various poses (right, left, up, down) and remain still during subsequent scanning.

- Field Map Acquisition: B0 field data are acquired at each pose using a 2D multi-echo gradient-echo (GRE) sequence with five echoes (spaced by 1.2 ms) and 2 mm isotropic resolution.

- Field Calculation: Field maps are calculated based on the unwrapped phase difference between echoes. A first-order navigator echo along the read-out direction is acquired for each shot to correct for dynamic frequency changes from scanner instability or respiration.

- Pose Determination: Head poses are determined via rigid-body co-registration of the GRE magnitude images, returning 6-parameter rotation and translation information.

- Data Processing: Frequency data are detrended based on the average frequency in a central brain region to reduce scanner field drift. The total field (TF) is separated into external (EF) and subject-derived (SF) components using a spherical phantom and subject-specific susceptibility models.

Protocol 2: Paired Motion-Corrupted and Motion-Free Data Acquisition

This protocol, utilized by the MR-ART dataset, enables direct evaluation of motion artifacts by acquiring matched data from the same participants [30].

- Participant Instruction: For the standard scan (STAND), participants are instructed not to move. For motion-corrupted scans (HM1, HM2), participants perform head nods (tilting down and up along the sagittal plane) when cued.

- Motion Level Control: Different artifact levels are created by varying cue frequency—5 times for low motion (HM1) and 10 times for high motion (HM2) evenly spaced during acquisition.

- Image Acquisition: T1-weighted 3D MPRAGE anatomical images are acquired with isotropic 1 mm³ resolution (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 3 ms) on a 3T scanner.

- Quality Assessment: Images are rated by expert neuroradiologists on a 3-point scale (1=clinically good, 2=medium, 3=bad quality) and processed through MRIQC for standardized image quality metrics (IQMs) like signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and entropy focus criterion (EFC).

Protocol 3: Motion Artifact Reproduction for PMC Validation

This method enables precise reproduction of motion artifacts corrected by Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) systems for validation purposes [32].

- Motion Tracking: An MR-compatible optical tracking system (e.g., Metria Innovation) records head position in six degrees of freedom (6 DoF) at up to 85 fps during a PMC-enabled scan.

- Data Logging: All tracking data are logged to a file during the initial patient scan.

- Artifact Reproduction: The logged motion data (with motion direction reversed) are fed back to the scanner during a subsequent experiment on a stationary volunteer or phantom.

- System Operation: A dedicated software library (e.g., libXPACE) uses the position data to dynamically update the scanning coordinate system, replicating the original relative motion between the scanning volume and the object without requiring patient motion.

Visualization of Motion Impact and Correction Workflows

Diagram 1: Motion-Induced B0 Changes and Correction Pathways

Diagram 2: Motion Sensitivity Comparison of k-Space Sampling Strategies

Table 2: Key Resources for Motion and B0 Field Change Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion-Corrupted Datasets | MR-ART Dataset [30] | Provides paired motion-free and motion-corrupted T1w brain scans from the same participants for algorithm validation. | 148 healthy adults; STAND, HM1, HM2 scans with expert artefact scores. |

| Motion Tracking Systems | Optical Motion Tracking [32] | Provides real-time 6 DoF head pose data for prospective motion correction (PMC). | MR-compatible camera system (e.g., Metria Innovation) tracking encoded markers at up to 85 fps. |

| Field Monitoring Hardware | Magnetic Field Probes [28] | Measures B0 field dynamics outside the head during motion to inform field modeling. | Array of field probes placed around the head for dynamic B0 field measurement. |

| Motion Correction Software | Prospective Correction Library (libXPACE) [32] | Software interface for real-time coordinate system updates in MRI sequences. | Integrates with tracking data to adjust gradients and RF pulses during sequence execution. |

| Image Quality Metrics | MRIQC [30] | Automated extraction of objective image quality metrics for artifact quantification. | Calculates SNR, EFC, CJV; provides standardized reports for quality control. |

| Unified Correction Frameworks | AI-Based Motion Correction [33] | Deep learning framework for correcting motion artifacts across multi-modal MRI. | Transformer model predicting motion degradation scores; Mixture of Experts for final correction. |

The interplay between head motion and induced B0 field changes represents a complex challenge that demands integrated solutions. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that pulse sequences with inherent motion robustness, particularly those employing radial k-space trajectories like MultiVane XD and Stack-of-Stars, provide significantly improved image quality in the presence of motion compared to conventional Cartesian sequences [31] [4]. However, even with optimized sequences, residual B0 field changes at high field strengths can remain problematic for quantitative techniques [28] [29].

Future progress will likely come from combined approaches that leverage motion-robust acquisition, real-time field monitoring, and advanced post-processing using deep learning [33]. The availability of high-quality, paired datasets like MR-ART will be crucial for validating these emerging methods [30]. For researchers and clinicians, selecting the appropriate motion mitigation strategy requires careful consideration of the clinical question, patient population, and available technical resources, with the understanding that effectively addressing the dual challenge of motion and B0 field changes is essential for achieving diagnostic image quality and robust research outcomes.

The Impact of Magnetic Field Strength on Motion Sensitivity

Motion sensitivity remains a significant challenge in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), impacting diagnostic quality and quantitative analysis. The strength of the main static magnetic field (B₀) is a fundamental parameter influencing every aspect of the MR signal chain, from signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) to artifact manifestation. This guide provides an objective comparison of motion sensitivity across different MRI field strengths, synthesizing current research to inform scanner selection and protocol optimization for researchers and development professionals. Understanding these relationships is crucial for advancing motion-robust imaging techniques across neuroimaging, musculoskeletal applications, and drug development studies where motion confounds can compromise data integrity.

Comparative Analysis of Field Strengths and Motion Characteristics

Technical Performance Metrics Across Field Strengths

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of MRI Field Strengths and Motion Sensitivity

| Field Strength Category | Typical SNR Profile | Primary Motion Artifacts | Susceptibility Artifact Severity | Typical Spatial Resolution | Key Advantages for Motion Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Field (<0.5 T) | Low inherent SNR [34] | Blurring, ghosting [35] | Significantly reduced [34] | Lower (clinical protocols) | Portable/bedside use [34] [36]; Reduced metallic implant artifacts [34] |

| Mid-Field (1.5 T) | Moderate SNR | Ghosting, phase encoding artifacts | Moderate | Standard clinical (1-2mm) | Established motion correction protocols; Balanced performance |

| High-Field (3.0 T) | High SNR [34] | pronounced ghosting, physiological noise | Pronounced [34] | High (sub-millimeter possible) | Faster acquisitions reducing motion window; Advanced acceleration techniques |

| Ultra-High Field (7 T+) | Very high SNR [37] | Severe physiological noise, flow artifacts | Severe [37] | Ultra-high (sub-millimeter to micron) [37] | Temporal resolution trade-off for spatial precision; Enhanced susceptibility-weighted contrast |

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in Motion-Prone Scenarios

| Field Strength | Motion Detection Accuracy | Portability & Point-of-Care Application | Susceptibility Artifact Reduction | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Field (0.064 T) | N/A | Full portability demonstrated [36]; Bedside ICH detection with 80.4% sensitivity, 96.6% specificity [36] | Significant reduction near metallic hardware [34] | Portable MRI for intracerebral hemorrhage evaluation [36] |

| 1.5 T | N/A | Limited (fixed installations) | Moderate | Current clinical reference standard |

| 3.0 T | N/A | Limited (fixed installations) | Higher than 1.5T | High-resolution clinical and research applications |

| 7 T | Enables micro-motion detection | Not portable | Most severe | Precision neuroimaging with enhanced spatial resolution [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Sensitivity Assessment

Radial Spoke Energy Method for Motion Detection

The radial spoke energy technique provides a self-navigated approach for motion detection without external hardware or sequence modifications, particularly effective in 3D radial imaging [35].

Experimental Protocol:

- Pulse Sequence: 3D radial acquisition with golden-angle or spiral phyllotaxis sampling [35]

- Data Collection: Acquire N radial spokes across M receiver coils, storing raw k-space data

- Spoke Energy Calculation: Compute energy for each spoke (i) and coil (j): Eij = ∑k|kij[k]|² where k represents discrete frequency components [35]

- Temporal Analysis: Apply sliding window summation to improve robustness of motion detection

- Multi-coil Integration: Use second principal component analysis (2ndPCA) to combine motion-sensitive signals across coils [35]

- Motion Quantification: Monitor energy fluctuations across successive spokes; significant variations indicate motion-induced anatomical shifts relative to coil sensitivities [35]

Validation Approach: Correlate spoke energy fluctuations with known motion patterns in ankle, knee, and head imaging, comparing to external tracking systems where available [35].

Low-Field Portable MRI for Clinical Motion Scenarios

This protocol evaluates the Hyperfine Swoop portable MRI (0.064 T) in intensive care settings where patient motion is common [36].

Experimental Protocol:

- Scanner Setup: Deploy portable 0.064 T MRI system at hospital bedside [36]

- Subject Population: Include critically ill patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or acute ischemic stroke (AIS) alongside healthy controls [36]

- Imaging Protocol: Implement T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences (mean exam time: 17:51 minutes) [36]

- Safety Monitoring: Maintain all intravenous lines and ICU monitoring equipment during scanning [36]

- Image Analysis: Two board-certified neuroradiologists evaluate ICH detection, localization accuracy, and volume quantification [36]

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) against conventional imaging reference standards [36]

High-Field Precision Imaging with Motion Compensation

This protocol utilizes 7T MRI for motion-sensitive quantitative imaging, leveraging high SNR for motion-resolved reconstructions [37].

Experimental Protocol:

- Scanner Setup: 7T Terra Siemens with 32-channel head coil [37]

- Session Design: Three imaging sessions per participant with multi-modal acquisitions [37]

- Structural Imaging: MP2RAGE (0.5 mm isovoxels) for cortical morphology; diffusion MRI (b-values 0, 300, 700, 2000 s/mm²) for connectomes [37]

- Functional Imaging: Multi-echo fMRI (1.9 mm isovoxels) during resting-state and task paradigms [37]

- Motion Management: Implement prospective motion correction and quantitative motion metrics [37]

- Data Analysis: Extract cortical gradients and connectomes to characterize motion-related variations in network organization [37]

Visualization of Motion Detection Methodology

Figure 1: Radial Spoke Energy Motion Detection Workflow. This self-navigated method detects motion through k-space energy variations without external hardware [35].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Sensitivity Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Field Strength Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Sequences | 3D radial sampling with golden-angle [35] | Motion-robust k-space trajectory; Enables retrospective correction | Effective across field strengths; Particularly valuable at high-field where motion artifacts are pronounced |

| Motion Detection Algorithms | Spoke energy analysis [35], FIDnav [35] | Self-navigated motion sensing without sequence modification | Computational efficiency enables real-time application across platforms |

| Portable MRI Systems | Hyperfine Swoop (0.064 T) [36] | Bedside imaging in motion-prone clinical settings; Enables studies previously impossible with fixed scanners | Unique to low-field due to reduced infrastructure requirements [34] |

| Multi-channel Coil Arrays | 32-channel head coils (7T) [37] | Enhanced parallel imaging for accelerated acquisitions; Reduced motion window through faster scanning | Critical for high-field systems to leverage intrinsic SNR advantages |

| Quantitative MRI Phantoms | Motion simulation devices | Controlled motion validation across field strengths | Essential for standardized performance comparisons |

| Advanced Reconstruction Frameworks | AI-based denoising, compressed sensing [34] | SNR enhancement and motion artifact suppression | Particularly impactful for low-field to address inherent SNR limitations [34] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The relationship between magnetic field strength and motion sensitivity presents a complex trade-off space for researchers. Low-field systems (≤0.5 T) offer inherent advantages through portability and reduced susceptibility artifacts, enabling novel applications in point-of-care settings where motion is unavoidable [34] [36]. Conversely, high-field systems (≥3 T) provide superior SNR and spatial resolution but require more sophisticated motion compensation techniques to realize their potential [37].

Emerging approaches like spoke energy motion detection demonstrate that computational methods can effectively address motion sensitivity across field strengths [35]. The integration of artificial intelligence with multi-modal data fusion further promises to extract motion-robust information from compromised datasets [38]. Future research directions should focus on quantifying motion tolerance thresholds across field strengths, developing standardized motion phantoms, and establishing cross-platform correction algorithms that maintain consistency in longitudinal studies.

For drug development professionals, these insights are particularly relevant when designing multi-site trials incorporating MRI biomarkers. Scanner selection should align with motion risk profiles of the participant population, with low-field portable options offering advantages for critically ill subjects, while high-field systems remain preferable for cooperative participants where microscopic resolution is paramount.

Advanced Motion Correction Methodologies: From Navigators to Novel Sequences

Motion artifacts remain a significant challenge in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly in advanced applications requiring high spatial resolution. Navigator-based techniques have emerged as powerful tools for measuring and correcting motion-induced artifacts and field fluctuations. This guide objectively compares the performance of volumetric Echo-Planar Imaging (EPI) navigators and field monitoring systems within the broader context of motion sensitivity across MRI pulse sequences. As the demand for higher field strengths and resolution grows, so does the vulnerability of MRI to both head motion and dynamic B0 field changes, necessitating sophisticated correction approaches that can operate concurrently with imaging sequences [39] [40].

Volumetric EPI Phase Navigators

Volumetric EPI phase navigators (PN) represent an advanced method for measuring head motion and B0 field changes simultaneously. This technique incorporates a rapidly acquired, highly accelerated volumetric EPI navigator immediately after excitation but before the primary T2*-weighted gradient echo (GRE) imaging data acquisition. This strategic timing ensures the navigator does not extend the scan duration while providing crucial field monitoring capabilities [39].

The implementation described uses a 3D GRE sequence with an integrated EPI navigator acquired at a shorter echo time than the primary imaging data. Through parallel imaging acceleration factors (R = Ry · Rz) in phase-encoding directions, temporal resolution of 0.54 seconds can be achieved with 4 mm isotropic spatial resolution. This design provides motion estimation accuracy better than 0.2° for rotation and 0.1 mm for translation, while B0 measurement errors typically range between -1.8 and 1.5 Hz at 7T [39].

Reconstruction involves several sophisticated steps: EPI ghost correction using blipless reference data, 2D-GRAPPA reconstruction with kernels of 3×2×2, and B0 distortion correction based on field maps generated from dual navigators. The magnitude of combined images uses sum of magnitudes rather than root sum of squares to minimize bias from B1 profiles, while phase images combine through magnitude-weighted averaging after normalization to a reference channel [39].

Field Monitoring Approaches

Field monitoring techniques encompass a spectrum of approaches for tracking dynamic B0 variations. Early methods included one-dimensional navigators and fat navigators that primarily addressed linear field changes, but these proved inadequate for capturing more complex, nonlinear field variations resulting from head motion [39]. More advanced methods like Field Probe monitoring systems utilize NMR field probes positioned around the subject to sample magnetic field variations independently of imaging, enabling real-time shim updates [41].

FID navigators (FIDnavs) represent a particularly efficient approach that measures signal from receiver coils without spatial encoding, enabling extremely rapid acquisition with minimal sequence impact. This method leverages the spatial encoding information inherent in multi-channel coil arrays to characterize spatiotemporal B0 fluctuations through a forward model based on a complex-valued reference image. The technique can model field inhomogeneity coefficients using spherical harmonic functions up to second order, comprising five independent parameters that capture the essential field variations affecting image quality [41].

Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of major navigator-based correction techniques:

Table 1: Performance comparison of navigator-based correction techniques

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Motion Accuracy | B0 Accuracy | Sequence Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric EPI PN | 4 mm isotropic | 0.54 s | <0.2° rotation, <0.1 mm translation | -1.8 to 1.5 Hz error at 7T | No scan time increase |

| FID Navigators | Voxel-wise (via model) | Per-slice (minimal TR increase) | Not specialized | Enables dynamic distortion correction | Minimal TR increase |

| Field Monitoring Probes | Limited by probe count & placement | ~100 ms (hardware dependent) | Not specialized | Direct field measurement | Requires additional hardware |

| Double Volumetric Navigators (DvNavs) | Low-resolution 3D | Per-volume (significant burden) | 3D rigid motion | Spatially-resolved field maps | Substantial acquisition burden |

Correction Efficacy and Artifact Reduction

Volumetric EPI navigators demonstrate particular strength in correcting artifacts in T2*-weighted MRI at high field strengths. The combination of motion estimation and B0 field monitoring enables comprehensive correction that addresses both rigid body motion and the consequent field changes that particularly affect susceptibility-weighted sequences. This dual correction capability is crucial at high fields where susceptibility effects scale with B0 strength [39] [40].

In functional MRI applications, FID navigators have shown significant improvements in temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR). During experiments involving continuous motion (nose touching task), FIDnav-based dynamic distortion correction yielded tSNR gains of 30% in gray matter. Even following image realignment to account for global shifts, residual tSNR improvements of 3% were achieved, demonstrating the value of addressing distortion beyond simple motion correction [41].

Comparative Performance in Challenging Scenarios

When addressing large head motions, prospective motion correction (PMC) utilizing external tracking has demonstrated superior performance compared to retrospective methods (RMC). In Cartesian 3D-encoded MPRAGE sequences, PMC maintains more consistent k-space sampling despite head rotations, reducing Nyquist violations that cannot be fully corrected retrospectively. However, increasing the correction frequency in RMC—applying corrections within echo trains rather than only between them—significantly improves performance, narrowing the gap with prospective approaches [42].

For challenging populations where motion is anticipated, such as pediatric imaging or clinical populations unable to remain still, navigator methods demonstrate particular value. One study implementing a GRAPPA-accelerated EPI sequence with tailored reconstruction successfully produced diagnostic-quality diffusion tensor imaging in 99.8% of 1600 pediatric cases, failing in only 3 subjects despite significant motion challenges [43].

Experimental Protocols

Implementation of Volumetric EPI Phase Navigators

The following workflow details the implementation of volumetric EPI phase navigators for motion and B0 correction:

Table 2: Key parameters for volumetric EPI navigator implementation

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Navigator Type | Volumetric EPI | Simultaneous motion and field monitoring |

| Spatial Resolution | 4 mm isotropic | Balance between accuracy and speed |

| Temporal Resolution | 0.54 s | Capture physiological field variations |

| Acceleration Factor | R = Ry · Rz (2D-GRAPPA) | Enable rapid acquisition |

| Kernel Size | 3×2×2 (readout × PE × PE) | GRAPPA reconstruction |

| B0 Accuracy | -1.8 to 1.5 Hz error range | Precise field monitoring |

The pulse sequence design interleaves two consecutive navigators after slab-selective RF excitation but before GRE imaging data collection. The k-space trajectory for navigators uses controlled 2D-aliasing with phase-encoding positions cycled through k-space by varying initial offsets. A full navigator covering entire k-space is obtained every set of R fast navigators, providing flexibility to select motion-free periods for autocalibration signal (ACS) data [39].

Reconstruction begins with EPI ghost correction using nearest blipless data as reference, followed by global B0-related phase correction for each readout line according to its echo time. Fast navigator images are reconstructed using 2D-GRAPPA, with the GRAPPA kernel applied in accelerated phase-encoding directions. The motion-free period for ACS identification is determined based on phase of blipless data, specifically selecting periods where global B0 frequency variation remains below 2 Hz [39].

FID Navigator Implementation for Dynamic Distortion Correction

FIDnav implementation utilizes a forward model based on a complex-valued multi-channel reference image with matched contrast properties to estimate B0 field changes. The model represents dynamic field variations as a series of low-spatial-order basis functions: ΔB0,n(r) = ΔB0,0(r) + β(r)bn, where r denotes spatial coordinate and n indexes time [41].

The forward model simulating FIDnav signals is expressed as: [ \begin{bmatrix} y{1,n} \ y{2,n} \ \vdots \ y{Nc,n}

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix} S{1,0} \ S{2,0} \ \vdots \ S{Nc,0} \end{bmatrix} \exp(i\gamma\tau{\text{NAV}}\beta bn) ] where (y{j,n}) is the measured FIDnav from coil j at acquisition n, each (S{j,0}) is a vector of complex pixel intensities from the reference image for coil j, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, (\tau{\text{NAV}}) matches the reference echo time to FIDnav sampling, β represents basis functions, and (bn) contains inhomogeneity coefficients at acquisition n [41].

Unknown coefficients are computed using a non-linear algorithm minimizing residual sum-of-squares between forward model predictions and measured FIDnavs: [ \hat{b}n = \arg \min{bn} \| yn - f(b_n) \|^2 ] This approach enables estimation of in-plane spherical harmonic functions up to second order, represented by five inhomogeneity coefficients, without requiring spatial encoding, image reconstruction, or phase unwrapping [41].

Visualization of Technical Relationships

Diagram 1: Relationship between artifact sources, correction approaches, and outcomes in navigator-based MRI

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and solutions for navigator-based MRI

| Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Volumetric EPI Navigator | Simultaneous motion and B0 field monitoring | High-resolution T2*-weighted MRI at high field |

| FID Navigators | Rapid B0 field measurement without spatial encoding | Dynamic distortion correction in EPI time series |

| External Field Probes | Direct magnetic field sampling independent of imaging | Real-time shim correction for high-field systems |

| Optical Motion Tracking | Markerless head pose estimation via surface scanning | Prospective motion correction in structural sequences |

| GRAPPA/Parallel Imaging | Accelerated k-space acquisition and reconstruction | Enable rapid navigator acquisition with minimal overhead |

| Non-uniform FFT (NUFFT) | Reconstruction of non-Cartesian k-space data | Retrospective motion correction with rotated trajectories |

| Blip-Up/Blip-Down Acquisition | Paired EPI with reversed phase encoding | Static field map estimation for distortion correction |

| Free-Water DTI Model | Computational separation of tissue and free-water compartments | Improved specificity in diffusion metrics for neurodegenerative disease |

Volumetric EPI navigators and field monitoring techniques represent complementary approaches addressing the intertwined challenges of head motion and B0 field fluctuations in MRI. Volumetric EPI navigators excel in applications requiring simultaneous high-resolution motion and field monitoring without extending scan time, particularly beneficial for high-field T2*-weighted imaging. Field monitoring methods, including FID navigators and field probes, offer specialized solutions for dynamic distortion correction and real-time shim updates. The optimal choice depends on specific application requirements: volumetric EPI for comprehensive correction in structural imaging, FID navigators for efficient distortion correction in fMRI, and field probes for highest precision B0 control in demanding high-field applications. As MRI continues toward higher fields and resolutions, integrated approaches combining multiple navigator techniques likely represent the future of robust, high-quality neuroimaging.

Subject motion remains a significant challenge in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), often degrading image quality and introducing biases in both clinical and research settings [44] [45]. Motion artifacts can reduce the diagnostic value of clinical scans and increase variance in research data, sometimes necessitating sequence repeats that incur substantial additional costs estimated at approximately $115,000 per scanner annually [44]. Two primary technological paradigms have emerged to address this problem: Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) and Retrospective Motion Correction (RMC). This guide provides an objective comparison of these operational paradigms, focusing on their methodological principles, performance characteristics, and implementation requirements to assist researchers and professionals in selecting appropriate correction strategies for their specific applications.

Operational Paradigms: Core Principles and Workflows

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC)

PMC operates on a real-time prevention principle. It continuously monitors head position during data acquisition and dynamically adjusts the imaging field-of-view (FOV) to remain stationary relative to the patient's head [44] [46]. This approach requires continuous, low-latency estimation of the rigid body position and orientation (pose) throughout the scan.

Motion Tracking Modalities: PMC implementations utilize various tracking approaches:

- Optical tracking systems using cameras (e.g., markerless tracking with structured light or Moiré phase markers) [44] [46]

- MR-based navigator techniques embedded within the pulse sequence [44]

- Radiofrequency (RF) field monitoring [45]

The crucial operational characteristic of PMC is that it modifies the acquisition process itself, updating imaging gradients, RF frequency, and phase to maintain consistent spatial encoding relative to the moving head [46]. Correction can be applied at different frequencies, from before each echo train (Before-ET) to more frequent updates within echo trains (Within-ET), with higher frequencies demonstrating superior artifact reduction [44].

Retrospective Motion Correction (RMC)

RMC functions on a post-acquisition compensation principle. It estimates motion that occurred during the scan and corrects for it during image reconstruction [44] [47]. Unlike PMC, RMC does not modify the acquisition process in real-time.

Motion Estimation Approaches:

- External motion tracking data recorded during acquisition [44]

- Image-based registration techniques [45]

- Navigator-based methods [48]

- Data-driven approaches utilizing information from multiple receiver coils [44]

The core reconstruction process involves adjusting k-space trajectories according to measured motion, followed by reconstruction using non-uniform Fast Fourier Transform (NUFFT) to account for the resulting irregular k-space sampling [44]. RMC preserves the original uncorrected data and operates independently of real-time latency constraints, but cannot address spin-history effects or fully compensate for Nyquist violations caused by rotational motion [44] [45].

Operational Workflow Comparison

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational differences between PMC and RMC workflows:

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison in Neuroanatomical MRI

A direct comparison study evaluated PMC and RMC performance in Cartesian 3D-encoded MPRAGE scans using the same markerless optical tracking system [44] [49]. The study employed quantitative quality assessment using the structural similarity index measure (SSIM) relative to motion-free reference scans.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Motion Correction Techniques

| Correction Method | Correction Frequency | Image Quality (SSIM) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMC | Before each echo train (Before-ET) | Superior to equivalent RMC [44] | Reduces local Nyquist violations; Handles spin-history effects [44] [45] | Requires sequence modification; Dependent on low-latency tracking [44] |

| PMC | Within echo train (Within-ET) | Highest overall [44] | Minimizes intra-echo-train motion artifacts [44] | Highest hardware/sequence demands [44] |

| RMC | Before each echo train | Inferior to PMC [44] | No sequence modification; Preserves original data [44] | Cannot correct spin-history effects; Limited by Nyquist violations [44] [45] |

| RMC | Within echo train | Improved over Before-ET RMC [44] | Higher correction frequency improves performance [44] | Computational reconstruction complexity [44] |

| Hybrid (PMC+RMC) | Within-ET retrospective on Before-ET PMC | Reduced motion artifacts vs. Before-ET PMC alone [44] | Addresses residual intra-echo-train motion [44] | Combined implementation complexity [44] |

Sequence-Specific Performance Considerations

Functional MRI (fMRI): PMC in fMRI reduces false positives and increases sensitivity compared to RMC, particularly with substantial motion [45]. PMC effectively addresses spin-history effects and intra-volume inconsistencies that RMC cannot fully correct [45]. The combination of PMC with dynamic distortion correction provides particularly advantageous performance for fMRI applications [45].

Diffusion-Weighted MRI: PMC maintains diffusion encoding direction coherence during motion by updating the gradient coordinate system in real-time [48]. RMC faces challenges in diffusion imaging due to strong signal and contrast changes between serial image volumes with different diffusion weightings, which limit the effectiveness of image registration methods [48].

High-Resolution Quantitative MRI: PMC significantly improves precision in quantitative maps, with reported 11-25% improvements in coefficient of variation in cortical sub-regions during deliberate head motion [46]. Importantly, PMC does not introduce extraneous artifacts in the absence of motion, making it safe for routine implementation [46].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Phantom and In Vivo Experimental Design

Comprehensive motion correction studies typically employ phantom and in vivo experiments with controlled motion paradigms [44]. The typical methodology includes:

Motion Tracking Implementation:

- Markerless optical tracking using systems like Tracoline TCL3.1 with 3D surface scans via structured light at 30Hz [44]

- Rigid-body transformation computation using iterative closest point algorithms [44]

- Cross-calibration between scanner and tracking system coordinates [44]

- Temporal calibration between tracking and scanner computers [44]

Experimental Conditions:

- Motion-free reference scans for baseline quality assessment [44]

- Controlled motion conditions with deliberate subject movement [44] [46]

- Factorized designs permuting motion/no motion and PMC on/off conditions [46]

- Correction frequency variations (e.g., Before-ET vs. Within-ET) [44]

Quantitative Assessment:

- Structural similarity index measure (SSIM) relative to reference [44]

- Visual artifact assessment by experienced reviewers [44]

- Precision quantification via coefficient of variation in tissue-specific regions [46]

Parallel Imaging Considerations

Studies specifically investigate GRAPPA calibration schemes to isolate motion correction effects:

- Integrated ACS (auto-calibration signal) acquired with motion present

- Pre-scan ACS acquired without intentional motion [44]

- Non-accelerated acquisitions to remove parallel imaging confounds [44]

The performance gap between PMC and RMC persists even with pre-scan ACS without intentional motion and without any GRAPPA acceleration, indicating fundamental advantages of prospective correction beyond parallel imaging interactions [44].

Motion Tracking and Correction Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Motion Correction Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Markerless Optical Tracking (Tracoline TCL3.1) [44] | Hardware | Head motion estimation via 3D surface scanning | 30Hz tracking rate; Structured light; No physical markers required |

| Moiré Phase Marker Systems (KinetiCor) [46] | Hardware | Head motion tracking with passive markers | 80Hz frame rate; sub-50μm precision; Requires mouthpiece mounting |

| retroMoCoBox [44] | Software | RMC implementation package | Adjusts k-space trajectories; GPU-based NUFFT reconstruction |

| FID Navigators [48] | Sequence | Motion detection via k-space center monitoring | Minimal sequence impact; Motion-sensitive DC component |

| mtrk Framework [50] | Software | Vendor-agnostic sequence development | Enables PMC-integrated sequences; Graphical sequence design |

| Pulseq [50] | Software | Open-source sequence prototyping | Standardized sequence representation; Vendor-neutral format |

Implementation Requirements Checklist

PMC Implementation Requires:

- Pulse sequence modification capability [44] [50]

- Real-time tracking data interface [44]

- Low-latency pose estimation (<100ms) [44]

- Geometric and temporal calibration procedures [44]

- Tracking marker mounting solution (e.g., custom mouthpieces) [46]

RMC Implementation Requires:

- Motion trajectory recording during acquisition [44]

- Computation resources for NUFFT reconstruction [44]

- K-space trajectory adjustment algorithms [44]

- Compatibility with reconstruction pipeline [44]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning

Deep learning approaches represent a growing trend in both motion estimation and artifact correction [51] [47]. Neural networks are being applied for:

- Motion artifact reduction in image and frequency domains [51] [47]

- Motion estimation from corrupted data [51]

- Motion-corrected reconstruction [51]