Neurovascular Coupling in fMRI and fNIRS: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of neurovascular coupling (NVC) as the fundamental physiological principle underlying functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).

Neurovascular Coupling in fMRI and fNIRS: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of neurovascular coupling (NVC) as the fundamental physiological principle underlying functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the cellular mechanisms of NVC, compares the methodological applications and signal origins of fMRI and fNIRS, discusses troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data interpretation, and validates findings through multi-modal integration. The review also examines the critical role of NVC dysfunction in neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular diseases, highlighting its potential as a biomarker for diagnosis and therapeutic intervention in clinical trials and preclinical research.

The Biological Basis of Neurovascular Coupling: From Cellular Mechanisms to Functional Imaging Signals

Defining Neurovascular Coupling and the Neurovascular Unit (NVU)

Neurovascular coupling (NVC) is the fundamental physiological mechanism that links transient neural activity to corresponding, localized changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) [1] [2]. This process, also termed functional hyperemia, ensures that activated brain regions receive an immediate and precise supply of oxygen and glucose to meet elevated metabolic demands [2]. The brain, despite accounting for only about 2% of total body weight, consumes approximately 20% of the body's total energy, yet possesses minimal energy reserves, making this tight coupling critical for normal function [3] [4]. The concept was first articulated by Roy and Sherrington in 1890, forming the Roy-Sherrington principle which states that the brain possesses an intrinsic mechanism to vary its vascular supply locally in correspondence with local variations of functional activity [2].

The functional complex that executes this process is the neurovascular unit (NVU). The NVU is an integrated system comprising neurons, astrocytes, and vascular cells (including endothelial cells, pericytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells), which work in concert to regulate cerebral blood flow [5] [6] [2]. The formal concept of the NVU was introduced by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in 2001, highlighting the interconnected relationship between brain cells and blood vessels that was previously underappreciated [7] [6]. The NVC process orchestrated by the NVU forms the physiological basis for functional neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), which measure hemodynamic changes as proxies for neural activity [1] [2].

Anatomical Composition of the Neurovascular Unit

The NVU is a multi-cellular structure that facilitates communication between neural tissue and the cerebral vasculature. Its components exist along a three-dimensional network of pial and penetrating arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins [5]. The radial composition of the capillary NVU, where the strongest blood-brain barrier properties are manifest, includes:

- Endothelial Cells: A continuous monolayer of specialized endothelial cells lines the brain's blood vessels, forming a physical barrier through circumferentially interconnected transmembrane tight junction proteins (e.g., claudins, occludin) [5]. These cells exhibit unique properties compared to peripheral endothelial cells, including suppressed transcytosis and polarized expression of various transporters, which together create a highly selective interface between blood and brain [5].

- Basement Membrane: A non-cellular, compact lattice meshwork composed of proteins including collagens, laminins, nidogens, perlecan, and agrin [5]. This membrane stabilizes the blood-brain barrier, anchors cells, facilitates signal transduction, and is dynamically maintained by bidirectional signaling with other NVU components [5].

- Mural Cells: This category includes pericytes on capillaries and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) on arterioles. Capillaries in the central nervous system have the highest pericyte coverage in the body (pericyte to endothelial cell ratio of approximately 1:4) [5]. Pericytes are embedded between the endothelial tube and astrocyte endfeet and play critical roles in BBB establishment, vascular development, and regulation of capillary blood flow [5]. VSMCs control vessel diameter through contraction and relaxation.

- Astrocytes: These glial cells project endfeet processes that completely ensheathe the vascular components, while their fine processes contact neuronal synapses [5]. This unique positioning allows astrocytes to transmit signals from neurons to the vasculature [5].

- Microglia: The brain's resident immune cells are also present within the NVU interface and contribute to neuroimmune responses [5].

- Neurons: Various neuronal subtypes, including pyramidal neurons and interneurons, initiate the NVC response through the release of neurotransmitters and vasoactive substances [3].

Table 1: Cellular Components of the Neurovascular Unit

| Cell Type | Primary Location | Key Functions in NVU |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells | Lumen of blood vessels | Form the physical barrier; regulate transport; release signaling molecules [5]. |

| Pericytes | Capillary wall (embedded in basement membrane) | Regulate capillary diameter; contribute to BBB integrity; produce extracellular matrix [5]. |

| Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells | Arteriole wall | Control arteriolar diameter; responsible for bulk blood flow regulation [1]. |

| Astrocytes | Parenchyma, with endfeet on vessels | Transmit signals from neurons to vasculature; release vasoactive substances [5]. |

| Neurons | Parenchyma | Initiate NVC via neurotransmitter release; different subtypes contribute specific vasoactive signals [3]. |

| Microglia | Parenchyma | Neuroimmune surveillance; can influence vascular function and integrity [5]. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Neurovascular Coupling

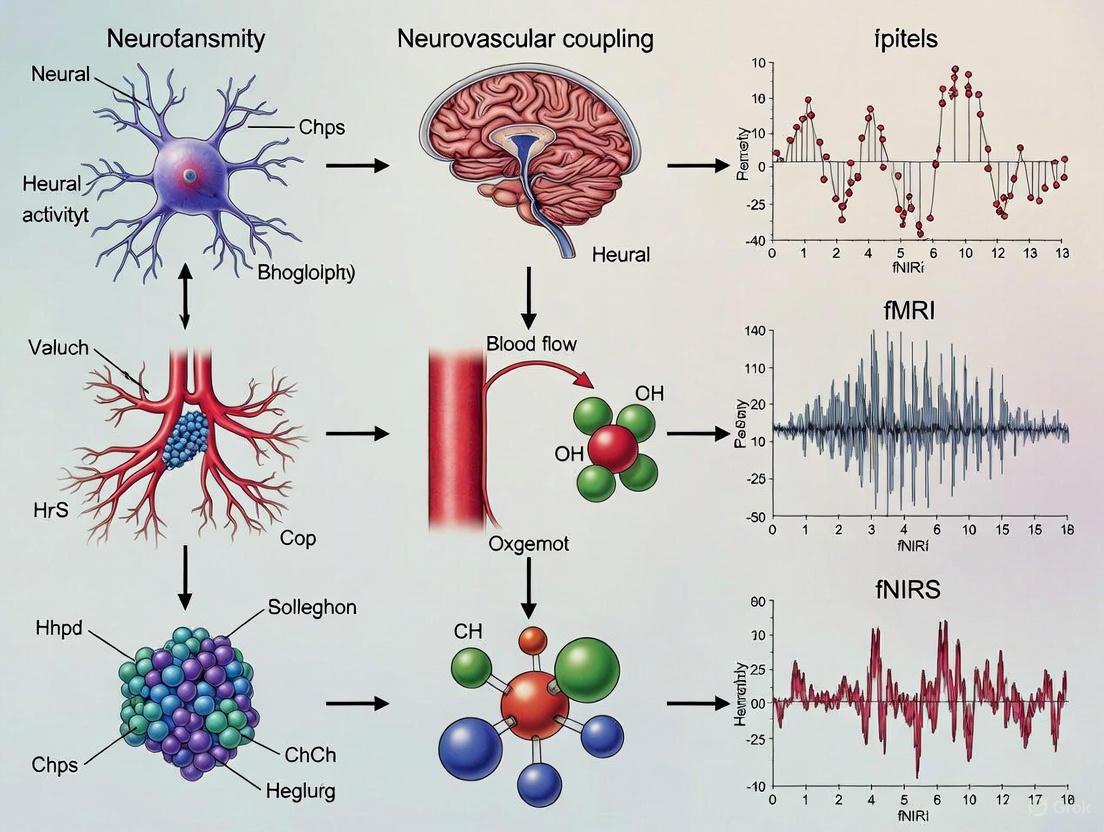

NVC is mediated by complex cellular signaling pathways that are initiated by synaptic activity and culminate in vascular dilation. The process involves a coordinated sequence of events across different NVU components, as illustrated in the following diagram:

NVC signaling involves multiple parallel pathways that are temporally coordinated [3] [4]:

Neuronal Signaling: Neurons directly influence blood vessels through the release of vasoactive substances. Glutamate-mediated activation of neurons leads to the release of potent vasodilators including nitric oxide (NO) from nitrergic interneurons and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from pyramidal neurons [1] [4]. Quantitative modeling of optogenetics data in mice has revealed that different neuronal sub-populations contribute to distinct temporal phases of the vascular response: the first rapid dilation is caused by NO-interneurons, the main sustained dilation during longer stimuli is caused by pyramidal neurons, and the post-stimulus undershoot is regulated by NPY-interneurons [3].

Astrocytic Signaling: Astrocytes transmit signals from synapses to blood vessels primarily through calcium (Ca²⁺) signaling [2]. Increased Ca²⁺ in astrocytes triggers the release of various vasoactive substances including potassium ions (K⁺) through large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BK) channels and inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channels on astrocytic endfeet, as well as metabolites of arachidonic acid such as prostaglandins and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) [1] [2]. The vasomotor effect of astrocytic signaling is bidirectional, with moderate Ca²⁺ increases inducing vasodilation and larger increases potentially causing vasoconstriction [2].

Vascular Response: The released vasoactive molecules act on smooth muscle cells of arterioles and pericytes of capillaries to induce relaxation and vessel dilation [1]. This dilation starts locally and back-propagates through endothelial cell signaling via gap junctions along the vascular tree to reach larger arteries, coordinating a regional hemodynamic response [1] [5]. While traditionally thought to be primarily controlled by arteriolar smooth muscle cells, recent evidence suggests that capillary pericytes may also participate in vasodilation during brain activation, potentially acting even faster than smooth muscle cells [1].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

In Vivo Human Assessment Techniques

Non-invasive neuroimaging techniques form the cornerstone of human NVC research, leveraging the coupling between neural activity and hemodynamics to infer brain function.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): The most widely used technique, fMRI typically measures the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal [1] [2]. The BOLD signal reflects changes in the ratio of oxygenated to deoxygenated hemoglobin following neural activity-induced changes in CBF and oxygen metabolism [1]. The typical hemodynamic response function (HRF) to a brief stimulus consists of a slight initial dip (debated), a main peak at approximately 3-6 seconds, and a post-stimulus undershoot before returning to baseline [3] [2]. Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) is another fMRI technique that directly quantifies CBF by magnetically labeling arterial blood water as an endogenous tracer, though it has lower temporal resolution than BOLD [1].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS): This optical neuroimaging technique measures relative changes in cerebral oxygenation by detecting light attenuation at different wavelengths as it passes through brain tissue [8]. fNIRS provides measures of oxyhemoglobin (O₂Hb), deoxyhemoglobin (HHb), and total hemoglobin (tHb), with tHb serving as a proxy for cerebral blood volume [8]. While fNIRS has poorer spatial resolution and cannot access deep brain structures compared to fMRI, it offers higher temporal resolution (can reach 1 ms), is more portable, and less susceptible to movement artifacts [1] [8].

A representative experimental protocol for assessing NVC using fNIRS is outlined below, adapted from research on sport-related concussion in retired athletes [8]:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for fNIRS-based NVC Assessment

| Protocol Phase | Duration | Procedure | Measured Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Recording | 5 minutes | Participant sits quietly, eyes open, breathing normally, no communication. | Baseline O₂Hb, HHb, and tHb concentrations. |

| NVC Task (Where's Wally) | 5 cycles (5 minutes total) | Each cycle: 20s eyes closed, 40s eyes open searching for "Wally" in an image. If found early, advance to next image. | Task-induced changes in O₂Hb, HHb, and tHb. Calculation of HbDiff (O₂Hb - HHb) to assess oxygen extraction. |

| Data Analysis | - | Compare hemodynamic response patterns between groups (e.g., patients vs. controls). | Amplitude, timing, and morphology of hemodynamic responses. |

Multimodal Imaging and Computational Modeling

Advanced research approaches combine multiple techniques to gain a more comprehensive understanding of NVC:

Multimodal Integration: Simultaneous measurement of electrophysiological (e.g., local field potentials - LFP) and hemodynamic signals provides direct insight into neurovascular relationships [3] [4]. For example, simultaneous LFP and fMRI measurements in primates have demonstrated that the BOLD signal correlates more closely with synaptic activity (LFPs) than with spiking output [4] [2].

Computational Modeling: Quantitative mathematical models integrate data from multiple species and experimental modalities to create unified frameworks of NVC [3]. A recent comprehensive model combines mechanistic understanding of cellular signaling pathways (from optogenetics in mice) with Windkessel models of blood flow dynamics and the biophysics of the BOLD signal [3] [4]. Such models can predict the contributions of specific neuronal sub-populations to different phases of the hemodynamic response and facilitate the translation of insights from animal studies to human applications [3].

Quantitative Parameters and Hemodynamic Response

The hemodynamic response measured by fMRI and fNIRS follows characteristic temporal dynamics and can be quantified using specific parameters. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics derived from NVC research:

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters in Neurovascular Coupling Research

| Parameter | Typical Values / Characteristics | Biological Significance | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) Timing | Peak: 3-6 s post-stimulus; Duration: 15-20 s [3] | Reflects speed and duration of CBF response to neural activity. | BOLD-fMRI, fNIRS |

| CBF Increase During Activation | 20-40% above baseline [1] | Magnitude of functional hyperemia; indicates vascular reactivity. | ASL, Laser Doppler/Speckle Flowmetry |

| Baseline CBF | Accepts ~20% of cardiac output [3] [9] | Reflects resting state metabolic support. | ASL, PET |

| BOLD Signal Change | Typically 0.5-5% at 3T [2] | Indirect measure of the balance between CBF and CMRO₂. | BOLD-fMRI |

| Cell-Specific Response Contributions | NO-interneurons: rapid dilation; Pyramidal neurons: sustained dilation; NPY-interneurons: post-stimulus undershoot [3] | Links specific neural elements to vascular response phases. | Optogenetics with microscopy (animal models) |

| Spatial Specificity | Vascular response localized to activated cortical columns [1] | Precision of metabolic supply to active neural tissue. | High-resolution fMRI, optical imaging |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neurovascular Coupling Studies

| Reagent / Material | Category | Primary Function in NVC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Optogenetic Constructs (e.g., Channelrhodopsin) | Genetic Tool | Selective activation of specific neuronal sub-populations (e.g., pyramidal cells, NO- or NPY-interneurons) to dissect their contribution to hemodynamic responses [3]. |

| Vasoactive Compound Inhibitors (e.g., L-NAME for NOS, COX inhibitors) | Pharmacological Agent | Selective blockade of specific signaling pathways (e.g., NO synthesis, prostaglandin production) to determine their role in functional hyperemia [1] [2]. |

| Calcium Indicators (e.g., GCaMP) | Imaging Probe | Monitoring intracellular Ca²⁺ dynamics in astrocytes and neurons during neural activation, a key signaling event in NVC [2]. |

| Human-derived Brain Cells (HBMVEC, HBVP, HA, HM, HO, HN) | Cell Culture Model | Creating physiologically relevant in vitro human NVU models for drug screening and disease modeling, overcoming species-specific limitations [10]. |

| Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) MRI Sequences | Imaging Sequence | Non-invasive quantification of cerebral blood flow (CBF) changes during neural activation, providing a direct hemodynamic metric [1] [9]. |

| fNIRS Systems (e.g., multi-channel systems) | Imaging Hardware | Portable, high temporal resolution monitoring of cortical oxygenation changes (O₂Hb, HHb) during cognitive or sensory tasks [8]. |

Clinical Implications and Pathophysiological Significance

NVC dysfunction, often termed neurovascular uncoupling, is implicated in a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders, making it a significant focus for therapeutic development.

Neurodegenerative Diseases: In Alzheimer's disease, impaired functional hyperemia has been detected both in animal models and humans, often before the appearance of amyloid plaques [1] [7]. Multiple mechanisms contribute, including amyloid-β-induced endothelial dysfunction, pericyte loss, and oxidative stress, which disrupt the NVU's ability to match blood flow to neural demand [7] [2]. Similar NVC alterations occur in Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease [7].

Cerebrovascular Disorders: Hypertension, small vessel disease, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy can damage arterioles and capillaries, altering the adaptive response of the cerebral microvasculature [1] [7]. After ischemic stroke, NVC impairments can occur remotely from the infarction site due to transhemispheric diaschisis [1].

Psychiatric Disorders: Recent research in major depressive disorder has identified NVC decoupling as a potential neuropathological mechanism [9]. Multimodal MRI studies in drug-naïve MDD patients have revealed reduced spatial correlation between neuronal activity (ALFF) and cerebral blood flow, with distinct patterns based on disease severity and sex [9].

Traumatic Brain Injury: Sport-related concussions and repeated mild traumatic brain injuries can lead to long-term NVC alterations, as evidenced by reduced cerebral hemodynamic responses in retired athletes with a history of multiple head injuries [8]. These changes potentially reflect underlying endothelial dysfunction and impaired cerebrovascular reactivity [8].

Therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving or restoring NVC function include interventions that improve endothelial function, reduce oxidative stress (e.g., inhibition of NADPH oxidases), increase nitric oxide bioavailability, and potentially target specific signaling pathways within the NVU [1] [2]. The development of sophisticated human-derived NVU models is expected to accelerate the discovery of such therapies by providing more physiologically relevant platforms for drug screening and disease modeling [10].

The neurovascular unit (NVU) is an integrated system comprising neurons, astrocytes, and vascular cells that coordinates cerebral blood flow (CBF) with neuronal activity, a process known as neurovascular coupling (NVC) [2]. This physiological mechanism ensures the precise and rapid delivery of oxygen and nutrients to active brain regions, forming the fundamental basis for functional neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI and fNIRS [11] [12]. The cellular players within the NVU—neurons, astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and pericytes—orchestrate complex signaling pathways to achieve this tight regulation. Understanding their distinct roles, interactions, and the experimental methods used to study them is crucial for interpreting neuroimaging data and developing therapies for neurological diseases where NVC is impaired [11] [13].

Table: Core Cellular Components of the Neurovascular Unit

| Cell Type | Primary Location | Key Functions in NVC | Major Vasoactive Signals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurons | Brain parenchyma | Initiate vasodilation via neurotransmitter release; pyramidal neurons act as "neurogenic hubs" [11]. | Glutamate, Nitric Oxide (NO), Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), ATP [11] [2] |

| Astrocytes | Interposed between synapses and vasculature | Connect synaptic activity to vascular response; release vasoactive factors via Ca²⁺ signaling [11] [14]. | Potassium (K⁺), Prostaglandins (PGE₂), Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids (EETs), Glutamate [13] [2] |

| Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) | Arterioles and arteries | Regulate large-scale, rapid changes in blood flow by contracting/relaxing to change arteriolar diameter [13] [15]. | Respond to NO, PGE₂, EETs, K⁺; cyclic GMP-mediated relaxation [13] |

| Pericytes | Capillaries (ensheathing, midcapillary, postcapillary subtypes) [15] | Control slower, local capillary tone and flow; involved in initial capillary dilation; maintain BBB [13] [15] [16]. | Respond to glutamate, NO, PGE₂ (via EP4 receptors), Angiotensin II; contract via ATP (P2X7 receptors) [13] [15] |

Neurons: Initiators of Hemodynamic Signals

Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Neurons, particularly excitatory pyramidal cells, serve as the primary initiators of NVC, functioning as "neurogenic hubs" [11]. Upon activation, these neurons release neurotransmitters and vasoactive mediators that trigger vasodilation. A key pathway involves glutamate, which acts on both astrocytes and neurons. Crucially, neuronal activity leads to calcium influx, activating neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) in specific interneurons, resulting in the production of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator [11] [13]. A systematic review concluded that nNOS blockade causes the most substantial reduction in neurovascular response, averaging 64% across studies [13]. Furthermore, pyramidal neurons have been identified as a major cellular source of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which induces vasodilation by acting on EP2 and EP4 receptors on vascular cells [11]. Inhibitory GABAergic interneurons also contribute by modulating the output of pyramidal cells, with some studies showing they can regulate blood flow via NO release [11].

Key Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Studying neuronal contributions to NVC often involves controlled stimulation and targeted inhibition of specific pathways.

- Whisker Stimulation in Rodents: A classic in vivo model where mechanical deflection of the whiskers activates neurons in the barrel cortex. The ensuing changes in local field potential (LFP) and CBF (measured via laser Doppler or laser speckle flowmetry) are recorded [11].

- Optogenetics: Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) is expressed in specific neuronal populations (e.g., pyramidal neurons). Light pulses are delivered via an optical fiber to selectively activate these neurons, allowing researchers to dissect their specific contribution to the hemodynamic response without confounding sensory inputs [11].

- Pharmacological Blockade: The role of specific mediators is tested by applying inhibitors. For example, the nonspecific NOS inhibitor L-NAME or the specific nNOS inhibitor S-Methyl-L-thiocitrulline (SMTC) is used to quantify the contribution of NO to the hyperemic response [13].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Neuronal NVC Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| L-NAME | Non-selective Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) inhibitor | Broadly blocks NO production to assess its overall role in NVC [13]. |

| S-Methyl-L-thiocitrulline (SMTC) | Selective neuronal NOS (nNOS) inhibitor | Specifically targets neuronal NO pathways, isolating their contribution [13]. |

| NS-398 | Selective COX-2 inhibitor | Blocks prostaglandin synthesis, used to probe the PGE2 pathway [11]. |

| Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) | Light-gated cation channel for optogenetics | Enables precise, millisecond-timescale activation of specific neuronal populations to evoke NVC responses [11]. |

| Local Field Potential (LFP) Recording | Measures summed synaptic activity from neuronal populations | Serves as a direct electrophysiological correlate of neural activity to compare with hemodynamic changes [11] [14]. |

Astrocytes: Bridges between Synapses and Vasculature

Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Astrocytes, with their endfeet ensheathing cerebral blood vessels, are ideally positioned to relay signals from synapses to the vasculature [11]. The traditional view involves glutamate from synaptic activity activating metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR5) on astrocytes, triggering intracellular calcium (Ca²⁺) waves. This Ca²⁺ increase leads to the production and release of several vasoactive agents [11] [2]. These include:

- Potassium (K⁺): Efflux through BK channels on astrocytic endfeet into the perivascular space, leading to VSMC hyperpolarization and dilation [2].

- Arachidonic Acid Metabolites: Phospholipase D2 (PLD2)-mediated production of arachidonic acid, which is metabolized by cyclooxygenase-1 (COX1) to the vasodilator PGE2, and by cytochrome P450 enzymes to epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) [13].

- Glutamate: Astrocytes can also release glutamate, which may act directly on vessels [11].

However, the role of astrocytic Ca²⁺ is debated. Some studies suggest it is necessary for capillary dilation via pericytes but not for arteriolar dilation, and the relevance of mGluR5 in the adult brain has been questioned [13].

Key Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Astrocytic function is probed by inhibiting their metabolism and manipulating key signaling molecules.

- In Vivo Calcium Imaging: Genetically encoded calcium indicators (e.g., GCaMP) are expressed in astrocytes. Two-photon microscopy is then used to visualize stimulus-evoked Ca²⁺ dynamics in astrocytic endfeet in vivo in relation to vessel diameter changes [12].

- Metabolic Inhibition with Fluorocitrate: Fluorocitrate is a reversible inhibitor of the astrocyte-specific Krebs cycle enzyme aconitase. Local administration selectively impairs astrocyte metabolism, allowing researchers to assess its impact on NVC by comparing blood flow responses (e.g., SCBF) before and after application while monitoring neural activity (LFP) [14].

- Genetic Knockout Models: Mice lacking inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 2 (IP3R2-KO) have impaired astrocytic Ca²⁺ signaling. These models are used to study the necessity of astrocytic Ca²⁺ waves in functional hyperemia [13].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Astrocytic NVC Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorocitrate | Inhibits astrocyte-specific aconitase | Used to reversibly impair astrocyte metabolism and assess its role in NVC without directly blocking neurons [14]. |

| IP3R2-Knockout Mice | Lacks primary Ca²⁺ release mechanism in astrocytes | Genetic model to study the necessity of astrocytic Ca²⁺ signaling in functional hyperemia [13]. |

| mGluR5 Antagonists (e.g., MTEP) | Blocks metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 | Tests the traditional glutamate-induced Ca²⁺ signaling pathway in astrocytes, though its role in adults is limited [13]. |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | High-resolution deep-tissue imaging | Allows real-time visualization of Ca²⁺ dynamics in astrocytic endfeet and simultaneous measurement of capillary/arteriole diameter in vivo [12]. |

Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Pericytes: Effectors of Blood Flow

Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

VSMCs and pericytes are the contractile cells that directly regulate vessel diameter. VSMCs surround arterioles and control large-scale, rapid changes in blood flow, while pericytes, embedded in the capillary basement membrane, control local capillary tone and flow heterogeneity [13] [15]. They respond to vasoactive signals from neurons and astrocytes by relaxing, thereby dilating the vessel.

- Nitric Oxide (NO): NO diffuses into VSMCs and activates soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), producing cyclic GMP (cGMP), which leads to relaxation. In pericytes, NO may act indirectly by inhibiting the vasoconstrictor 20-HETE [13].

- Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2): PGE2 binds to Gₛ-coupled EP4 receptors on pericytes and VSMCs, increasing intracellular cAMP and promoting relaxation [13].

- Potassium (K⁺): Elevated external K⁺ (5-20 mM) leads to VSMC and pericyte hyperpolarization by activating inward-rectifier K⁺ (Kir) channels, closing voltage-gated calcium channels, and causing relaxation [2].

- Constrictor Signals: ATP can induce pericyte contraction via P2X7 receptors, and high concentrations of PGE2 can cause vasoconstriction via EP1 receptors [13] [15].

Pericytes are heterogeneous; ensheathing pericytes at the arteriole-capillary junction express high levels of α-smooth muscle actin and are primarily responsible for regulating microvascular blood flow, while mid-capillary pericytes control local capillary tone [15].

Key Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Investigating contractile cells involves isolating their responses and visualizing their dynamics.

- Two-Photon Microscopy of Pericyte Ca²⁺ and Diameter: This technique is used in awake, head-fixed mice to image Ca²⁺ fluctuations in pericytes and simultaneously measure the diameter of associated capillaries in response to sensory stimulation or pharmacological application [11] [15].

- Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging (LSCI): A wide-field optical technique that provides high spatiotemporal resolution maps of CBF changes. It is often used in conjunction with stimulation (e.g., whisker, forepaw) to visualize the cortical hemodynamic response and assess the impact of manipulating VSMCs or pericytes [12].

- Isolated Vessel Myography: Parenchymal arterioles are surgically removed and maintained in a bath. Their diameter changes in response to vasoactive drugs (e.g., PGE2, NO donors) applied directly to the bath are measured, allowing for controlled study of VSMC pharmacology [13].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Contractile Cells

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| ODQ | Inhibitor of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) | Blocks the NO-cGMP signaling pathway in VSMCs to test its specific role in vasodilation [13]. |

| HET0016 | Selective inhibitor of 20-HETE synthesis | Used to probe the role of the vasoconstrictor 20-HETE in capillary perfusion and its interaction with NO signaling in pericytes [13]. |

| L-NAME | Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) inhibitor | Reduces endogenous NO production, leading to impaired vasodilation and used to study NO's role in NVC [13]. |

| PF-04418948 | Selective EP2 receptor antagonist | Pharmacologically blocks the PGE2 EP2 receptor to investigate its role in pericyte-mediated capillary dilation [13]. |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | High-resolution deep-tissue imaging | Enables direct in vivo observation of pericyte Ca²⁺ signals and contractile dynamics alongside capillary diameter changes [15]. |

Integrated Experimental Workflow for NVC Investigation

A comprehensive investigation of NVC in animal models typically integrates multiple techniques to correlate neural activity with hemodynamic responses and pinpoint cellular mechanisms.

Table: Quantitative Data on Key NVC Signaling Pathways

| Signaling Pathway | Primary Mediator | Cellular Source | Vascular Target | Reported Impact on CBF Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitric Oxide (NO) | nNOS-derived NO | nNOS Interneurons [11] | VSMCs, Pericytes [13] | ~64% reduction with nNOS blockade [13] |

| Prostaglandins | PGE2 | Pyramidal Neurons, Astrocytes [11] | Pericyte EP4 Receptors [13] | Significant component; EP4 blockade inhibits dilation [13] |

| Potassium (K⁺) | K⁺ (5-20 mM) | Astrocytic Endfeet (BK/Kir channels) [2] | VSMCs, Pericytes [2] | Key mechanism for astrocyte-mediated vasodilation [2] |

| EETs | Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids | Astrocytes (CYP450) [13] | Capillary Pericytes [13] | Contributes to capillary-level NVC [13] |

| Astrocytic Ca²⁺ | Ca²⁺ waves | Astrocytes [11] | Various downstream effectors | Necessary for capillary but not arteriolar dilation in some studies [13] |

Neurovascular coupling (NVC) is the fundamental biological process that ensures a rapid and precise increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) to regions of heightened neural activity, a mechanism also known as functional hyperemia [17] [11]. The brain's impressive energy demands, coupled with its very limited energy reserves, make this dynamic regulation of blood supply critically important for sustaining normal neural function [17]. The coordinated interaction of vasoactive signaling molecules—primarily glutamate, nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandins (PGs), and potassium (K+)—ensures that active neurons receive adequate oxygen and nutrients [1] [11]. This process is orchestrated by the neurovascular unit (NVU), a complex network comprising neurons, astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and pericytes [11].

Understanding these signaling pathways is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for interpreting functional neuroimaging data. Techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) rely on hemodynamic signals that are ultimately governed by these molecular players [1] [18]. Furthermore, the failure of NVC is increasingly recognized as an early event in various cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, making these pathways promising targets for therapeutic intervention [17] [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the roles, interactions, and experimental investigation of these key vasoactive signals.

Detailed Mechanisms of Key Vasoactive Signals

Glutamate: The Primary Initiator

As the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, glutamate serves as the canonical trigger for the NVC response [17]. Its actions are mediated through two distinct receptor classes located on different cell types:

- Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors (iGluRs) on Neurons: The activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAr) on postsynaptic neurons is a central pathway. Glutamate binding and subsequent Ca²⁺ influx through NMDAr lead to the activation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and the production of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator [17]. The enzyme nNOS is strategically anchored to the synaptic membrane via a supramolecular complex with NMDAr and the scaffold protein PSD-95, ensuring rapid and localized NO production in response to glutamate release [17].

- Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors (mGluRs) on Astrocytes: Glutamate also activates G-protein coupled mGluRs on astrocytes, initiating a calcium signaling cascade within these glial cells. This results in the synthesis and release of various vasoactive metabolites, including epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and prostaglandins (PGs), which act on adjacent arterioles [1] [11].

Table 1: Glutamate Receptors in Neurovascular Coupling

| Receptor Type | Primary Location | Signaling Pathway | Key Vasoactive Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMDA Receptor (iGluR) | Postsynaptic Neurons | Ca²⁺ influx → nNOS activation | Nitric Oxide (NO) |

| Metabotropic Receptor (mGluR) | Astrocytes | G-protein → Ca²⁺ release → PLA₂/COX activation | Prostaglandins, EETs |

Nitric Oxide (NO): The Gaseous Messenger

Nitric oxide is a ubiquitous, gaseous signaling molecule recognized as a key player in NVC, essential for the full development of the neurovascular response [17]. Its synthesis, bioavailability, and signaling are tightly regulated through multiple pathways.

- Synthesis via NOS Enzymes: The classical pathway for •NO production is the enzymatic conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline by a family of nitric oxide synthases (NOS), requiring oxygen and several cofactors (NADPH, FAD, FMN, heme, BH₄) [17] [19]. Three major isoforms exist:

- Neuronal NOS (nNOS): Constitutively expressed in neurons and activated by Ca²⁺-calmodulin following NMDAr activation [17].

- Endothelial NOS (eNOS): Constitutively expressed in endothelial cells, activated by shear stress or Ca²⁺-calmodulin, and critically involved in vascular homeostasis [17] [20].

- Inducible NOS (iNOS): Expressed in glial cells (e.g., astrocytes, microglia) primarily under inflammatory conditions; its activity is Ca²⁺-independent and produces •NO for prolonged periods [17].

- The Nitrate-Nitrite-NO Pathway: This NOS-independent pathway provides an important backup system for •NO generation, particularly under hypoxic conditions when NOS activity is limited by low O₂. Inorganic nitrate (NO₃⁻) from the diet is reduced to nitrite (NO₂⁻) by commensal bacteria or mammalian enzymes, which is then further reduced to •NO by various heme-containing proteins [17].

- Signaling and Bioavailability: The primary vasodilatory mechanism of •NO involves the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) in vascular smooth muscle cells, leading to increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and subsequent vasodilation [17] [19]. The bioavailability of •NO is critically threatened by oxidative stress, as •NO rapidly reacts with superoxide anion (O₂•⁻) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), a cytotoxic molecule that can uncouple NOS enzymes, further exacerbating oxidative damage [17].

Prostaglandins and Other Eicosanoids

Prostaglandins (PGs), vasoactive lipids derived from arachidonic acid, constitute another major signaling pathway in NVC. Their synthesis is initiated when neural activity triggers an increase in intracellular Ca²⁺ in astrocytes, activating the enzyme phospholipase A₂ (PLA₂). PLA₂ releases arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, which is then metabolized by cyclooxygenase (COX), particularly the COX-2 isoform, to produce prostaglandin H₂ (PGH₂), the precursor for various prostanoids, including the vasodilator PGE₂ [1] [11]. A recent multidisciplinary study identified PGE₂ as the principal prostaglandin in NVC, with pyramidal neurons being a major cellular source, and its vasodilatory effects are mediated primarily through the EP2 and EP4 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells [11]. It is important to note that astrocytes can also produce vasoconstrictive arachidonic acid metabolites, suggesting a complex, finely-tuned regulation of vascular tone [1].

Potassium Ions

The regulated efflux of potassium ions (K⁺) from neurons and astrocytes is a key mechanism for mediating vasodilation. During neural activity, a local increase in extracellular K⁺ concentration can hyperpolarize vascular smooth muscle cells by activating inward-rectifier potassium (KIR) channels and sodium-potassium ATPase (Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase) pumps [1]. This hyperpolarization leads to the closure of voltage-gated calcium channels, reducing intracellular Ca²⁺ and promoting vasodilation. Astrocytes contribute significantly to this process; their endfeet, which enwrap cerebral blood vessels, are enriched with BKCa (large-conductance Ca²⁺-activated K⁺) channels. Astrocytic Ca²⁺ elevations can activate these channels, resulting in a targeted release of K⁺ into the perivascular space to modulate arteriolar diameter [1].

Integrated Signaling Pathways

The vasoactive signals described above do not operate in isolation but form an integrated, hierarchical network to ensure a robust and spatially precise hemodynamic response. The following diagram illustrates the primary cellular pathways and their interactions.

Figure 1. Integrated cellular pathways of vasoactive signaling in neurovascular coupling. Glutamate release from neurons acts on both neuronal NMDA receptors and astrocytic metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), initiating parallel signaling cascades that converge to cause vasodilation. Key: NO (Nitric Oxide), PGE₂ (Prostaglandin E₂), K⁺ (Potassium Ions).

The process begins with glutamatergic synaptic activity [17]. The canonical pathway involves the activation of neuronal NMDAr, Ca²⁺ influx, and nNOS-derived NO production, which is considered a major contributor to the rapid vasodilation [11]. In parallel, glutamate activation of astrocytic mGluRs elevates intracellular Ca²⁺ in astrocytes, leading to the production of PGE2 and the efflux of K⁺ from their endfeet [1] [11]. While the neuronal pathway is associated with the large and rapid component of vasodilation, the astrocytic pathway may be involved in slower, more sustained regulation of blood flow [1]. These signals collectively act on vascular smooth muscle cells to induce hyperpolarization and relaxation, thereby increasing local blood flow to match the metabolic demand of the active neurons.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Vasoactive Signaling Modulation on Hemodynamic Responses

| Intervention / Condition | Experimental Model | Key Measured Outcome | Reported Effect | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nNOS Inhibition | In vivo (Multiple animal studies) | Neurovascular Response (CBF) | Average reduction of 64% (across 11 studies) | [11] |

| NOS/COX/Epoxygenase Inhibition | Young C57BL/6 mice | Gait Coordination (Duty Cycle) | Significant decrease; altered footfall patterns | [21] |

| History of mTBI | Retired rugby players (Human, fNIRS) | Oxyhemoglobin (O₂Hb) in Left MFG | Reduced response: -0.015 ± 0.258 μM vs -0.160 ± 0.311 μM in controls | [8] |

| Cognitive-Motor Dual-Task | Healthy humans (EEG-fNIRS) | Neurovascular Coupling (NVC) Strength | Decreased NVC in theta, alpha, and beta EEG rhythms | [18] |

| Functional-Pharmacological Coupling (MPH) | Humans with ADHD | Sustained Attention Performance | Improved performance when MPH coupled with cognitive task | [22] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

A rigorous investigation of vasoactive signaling requires a toolkit of specific pharmacological agents, genetic models, and advanced imaging techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Investigating Vasoactive Signaling

| Category / Target | Example Reagents / Tools | Primary Function / Mechanism | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO Signaling | L-NAME (NOS inhibitor) | Non-selective inhibitor of NOS enzymes; reduces •NO production. | Used to establish causal role of NO; mimics NVC aspects of aging [21]. |

| 7-NI (7-Nitroindazole) | Relatively selective inhibitor of nNOS. | Used to dissect neuronal vs. endothelial NO contributions [17]. | |

| Prostaglandin Signaling | Indomethacin | Non-selective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor. | Blocks prostaglandin synthesis; used to assess their contribution to NVC [21]. |

| Glutamate Receptors | MK-801 | Non-competitive NMDAr antagonist. | Blocks initial trigger for neuronal NO pathway [17]. |

| Potassium Channels | BaCl₂ (Barium Chloride) | Inhibitor of inward-rectifier K⁺ (KIR) channels. | Used to investigate K⁺-mediated vasodilation [1]. |

| Experimental Models | Genetic Knockout Mice (e.g., nNOS⁻/⁻, eNOS⁻/⁻) | Models with specific gene deletions. | Allows for dissection of specific isoform functions in NVC [17] [11]. |

| Imaging & Measurement | Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging | Measures cortical blood flow changes in vivo. | High spatial and temporal resolution for monitoring CBF [1]. |

| fNIRS / fMRI / EEG | Non-invasive human neuroimaging. | Assesses integrated NVC response and its impairment in pathology [8] [18]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Pharmacological Dissection of NVC

The following workflow, derived from classic and contemporary studies, outlines a standard approach for isolating the contribution of different vasoactive pathways in an animal model [21].

Figure 2. Experimental workflow for pharmacological dissection of NVC pathways. This protocol allows for the quantitative assessment of the contribution of specific vasoactive pathways (NO, prostaglandins, EETs) to the overall functional hyperemia response.

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: In an anesthetized or awake, head-fixed animal model (e.g., mouse), a functional hyperemia response is elicited using a controlled stimulus (e.g., whisker stimulation, forepaw stimulation, or visual stimulus). The resulting change in local CBF is measured using a high-resolution technique such as laser Doppler flowmetry or laser speckle contrast imaging [1] [21].

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Animals are systemically (e.g., intraperitoneal injection) or locally (e.g., topically on the cortex) administered with one or more pathway-specific inhibitors.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: After a suitable period for drug action, the exact same functional stimulus is applied, and the CBF response is measured again.

- Data Analysis: The post-inhibition CBF response is quantitatively compared to the baseline response. The percentage reduction in the response amplitude (e.g., peak CBF change) directly indicates the relative contribution of the inhibited pathway to the total NVC response. This method has shown that nNOS inhibition can reduce the response by an average of 64% [11].

Implications for Functional Neuroimaging and Disease

The vasoactive signaling pathways detailed above form the biological foundation for non-invasive neuroimaging techniques like fMRI and fNIRS [1] [18]. The blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal in fMRI is an indirect measure of neural activity that is heavily influenced by the neurovascular response and the resulting changes in blood flow, blood volume, and oxygen metabolism [17] [1]. Therefore, any pathology or pharmacological manipulation that alters the efficacy of glutamate, NO, prostaglandin, or potassium signaling can directly impact the BOLD signal, potentially confounding its interpretation as a pure index of neural activity [17] [21] [22].

Dysregulation of NVC is a hallmark of numerous neurological conditions. In Alzheimer's disease, amyloid-β peptides can disrupt NVC, potentially by inducing oxidative stress that scavenges NO and promotes peroxynitrite formation, leading to endothelial and neuronal dysfunction [17] [1]. In cerebral small vessel disease and hypertension, chronic oxidative stress and inflammation impair NO bioavailability, leading to neurovascular uncoupling [1] [11]. Even mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), as seen in retired athletes, can lead to long-term impairments in hemodynamic responses, as evidenced by blunted O₂Hb measured with fNIRS [8]. Furthermore, experimental induction of neurovascular uncoupling in mice leads to measurable deficits in complex motor behaviors like gait coordination, establishing a direct cause-and-effect relationship between NVC failure and functional impairment [21].

Emerging therapeutic strategies focus on rescuing NO bioavailability through dietary interventions (e.g., nitrate and polyphenols) or physical exercise, which may help mitigate NVC dysfunction in neuropathological conditions [17]. Moreover, the novel concept of "functional-pharmacological coupling" proposes that administering a drug alongside a behavioral task that activates the drug's target brain circuits can enhance drug delivery and efficacy by leveraging activity-dependent increases in local cerebral blood flow [22]. This approach highlights the potential for harnessing our understanding of NVC for improved pharmacotherapy.

The Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) is a fundamental physiological concept that describes the tightly regulated temporal relationship between local neural activity and subsequent changes in cerebral blood flow. This relationship forms the cornerstone of non-invasive brain imaging techniques, most notably functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), which rely on blood flow changes as a proxy for neural activity [23] [24]. In healthy adults, an increase in neuronal firing triggers a complex cascade of events leading to a localized influx of oxygenated blood, a process known as functional hyperemia [25]. This response is not merely a metabolic support function; emerging evidence suggests it may play an active role in modulating neural circuitry and information processing [25]. Understanding the precise shape, timing, and determinants of the HRF is therefore critical for accurate interpretation of neuroimaging data across basic research and clinical applications, including drug development [26].

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the HRF, framing it within the broader context of neurovascular coupling research. It details the biological mechanisms, methodological considerations for measurement, and critical sources of variability that researchers and drug development professionals must account for in their experimental design and data analysis.

Core Neurovascular Coupling Mechanisms

The HRF is the observable output of neurovascular coupling (NVC), the biological process orchestrated by the neurovascular unit (NVU). The NVU is an integrated entity comprising neurons, astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and pericytes [13] [27]. Signaling within this unit ensures that active brain regions receive a rapid and precise supply of energy substrates.

Molecular Signaling Pathways

The communication between neurons, glia, and vasculature involves several overlapping and redundant molecular pathways, which are summarized in the diagram below.

- Nitric Oxide (NO) Pathway: Neuronal depolarization leads to calcium influx, activating neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). The produced NO is a potent vasodilator. It exerts its effects on vascular smooth muscle cells by raising cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels. Evidence suggests that in capillary pericytes, NO may act indirectly by inhibiting the production of the vasoconstrictor 20-HETE [13].

- Arachidonic Acid Metabolites: Glutamate-mediated activation of astrocytic metabotropic receptors triggers calcium increases, leading to the production of arachidonic acid (AA). AA is metabolized into vasoactive agents, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), which act on the prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 (EP4) on pericytes and VSMCs to induce vasodilation [13] [23].

- Purinergic and Other Signals: Neuronal activity also leads to the release of adenosine, which acts as a vasodilator, particularly when neuronal ATP is low [23]. Potassium ions and other vasoactive molecules also contribute to this complex, redundant signaling system [13].

The result of these pathways is the relaxation of VSMCs and capillary pericytes, leading to vasodilation and a pronounced increase in local cerebral blood flow that substantially exceeds the immediate metabolic oxygen demand [23]. This oversupply is the physiological basis for the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast used in fMRI [25] [23].

Quantitative Profiling of the HRF

The canonical HRF is a stereotypical waveform characterized by several key parameters that can be quantified. These metrics are essential for modeling and interpreting BOLD and fNIRS signals.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters of the Hemodynamic Response Function

| Parameter | Typical Value (fMRI/BOLD) | Description | Physiological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset (Latency) | 1-2 seconds | Delay between neural impulse and the start of the HRF. | Speed of neurovascular signaling. |

| Time-to-Peak (TTP) | 5-6 seconds | Time taken for the HRF to reach its maximum amplitude. | Efficacy of the vasodilatory response. |

| Full-Width at Half-Maximum (FWHM) | 4-5 seconds | Width of the HRF at half of its peak amplitude. | Duration of the hemodynamic response. |

| Response Height (RH) | 0.5-2% BOLD change | Peak amplitude of the HRF. | Strength of the blood flow response. |

| Undershoot | ~10% of peak | A negative dip following the main response. | Post-stimulus vasoconstriction or metabolic processes. |

These parameters are not fixed. A 2025 study analyzing high-resolution fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project found significant variability in HRF amplitude and latency across different brain regions and tasks, while TTP and FWHM were relatively more consistent [28]. This variability must be modeled for accurate analysis.

Mathematical Modeling of the HRF

In practice, the HRF is often modeled mathematically to serve as a regressor in statistical models like the General Linear Model (GLM). The most common model uses a combination of two Gamma functions to capture the positive response and the subsequent undershoot [29]:

HRF(t) = A * ( (t^(α₁-1) * β₁^α₁ * exp(-β₁*t)) / Γ(α₁) - c * (t^(α₂-1) * β₂^α₂ * exp(-β₂*t)) / Γ(α₂) )

Where:

Ais a scaling factor for amplitude.α₁, β₁control the delay and dispersion of the positive response.α₂, β₂control the delay and dispersion of the undershoot.cis a scaling factor for the undershoot ratio.Γis the Gamma function.

This model typically involves six free parameters that can be estimated from data to account for inter-regional and inter-subject variability [29]. More flexible approaches, such as using Fourier basis sets or sine series expansions, are also employed to capture even greater shape variability without assuming a rigid canonical form [28].

Methodological Approaches for HRF Investigation

Different neuroimaging modalities provide unique windows into the HRF, each with advantages and limitations.

Primary Imaging Modalities

Table 2: Key Modalities for Measuring the Hemodynamic Response

| Modality | Measured Signal | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Advantages & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) | High (mm) | Moderate (1-2 s) | Gold standard for whole-brain mapping; excellent spatial resolution [26]. |

| fNIRS | Concentration changes in Oxy-Hb and Deoxy-Hb | Low (cm) | High (~0.1 s) | Portable, tolerant of movement; ideal for naturalistic settings, bedside monitoring, and BCI [29] [30]. |

| Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) fMRI | Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) | High (mm) | Low (several s) | Provides quantitative CBF measurement, not just a relative signal like BOLD [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for HRF Assessment

Robust experimentation requires carefully designed protocols. Below is a generalized workflow for an HRF study, integrating elements from both fMRI and fNIRS approaches.

Detailed Methodological Notes:

- Stimulus Paradigms: For precise HRF estimation, event-related designs with brief, isolated stimuli are often preferred over block designs. The duration and intensity of the stimulus should be carefully controlled [28].

- fNIRS Pre-processing: Raw fNIRS signals require specific pre-processing to remove physiological noise. This often involves wavelet transform techniques to isolate the task-evoked signal from cardiac pulsation, respiratory signals, and low-frequency Mayer waves [29] [31].

- HRF Estimation in GLM: The General Linear Model framework is used to estimate the HRF's contribution to the measured signal. The model is formulated as:

Y = X * β + εwhereYis the measured BOLD or fNIRS signal,Xis the design matrix containing the convolved HRF model,βis the vector of unknown weights (estimating activation strength), andεis the error term [29] [31]. Model fit can be improved by adding time and dispersion derivatives to the canonical HRF to account for slight timing and shape variations [24]. - Deconvolution Methods: When the precise timing of neural events is unknown (e.g., in resting-state fMRI), blind deconvolution techniques can be employed. These methods, such as the data-driven

rsHRFtoolbox or stochastic Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM), solve the inverse problem to estimate both the neural activity and the HRF shape directly from the fMRI time series [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for HRF Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Canonical HRF Model | A fixed, standardized model of the hemodynamic response. | Serves as the default regressor in GLM for task-based fMRI/fNIRS analysis [29]. |

| General Linear Model (GLM) | A statistical framework for estimating the contribution of the HRF to the measured signal. | Used to compute statistical parametric maps of brain activation [29] [31]. |

| NIRS-SPM Toolbox | A public statistical toolbox for fNIRS data analysis. | Provides a validated pipeline for fNIRS data preprocessing and GLM-based activation mapping [29]. |

| Finite Impulse Response (FIR) Basis Set | A flexible set of basis functions that does not assume a fixed HRF shape. | Used to estimate the shape of the HRF in a data-driven manner with minimal assumptions [28]. |

| Pharmacological Agents (e.g., NOS inhibitors) | Used to probe specific neurovascular coupling pathways. | Administered in animal models to isolate the contribution of nitric oxide to the HRF [13]. |

| Wavelet Transform Toolboxes | Algorithms for decomposing signals into time-frequency space. | Applied to fNIRS data to isolate and remove physiological noise (cardiac, respiratory) [29] [31]. |

| Simplex/Nelder-Mead Algorithm | A nonlinear optimization algorithm for parameter estimation. | Used to find the optimal parameters (e.g., delays, dispersions) for a flexible HRF model in fNIRS [29]. |

Critical Considerations and Clinical Relevance

Acknowledging and accounting for HRF variability is paramount for robust research and clinical application.

The HRF is not a one-size-fits-all function. Its shape varies significantly due to:

- Regional Differences: HRF shape differs across brain regions, likely due to local variations in vascular density and neurovascular architecture [28] [24]. For example, the HRF in the visual cortex has been shown to be parametrically different from that in the motor cortex [28].

- Inter-Subject Variability: Substantial differences in HRF shape exist between individuals, sometimes exceeding regional differences within a single subject [29] [24]. Time-to-peak can vary by up to several seconds across individuals [28].

- Developmental and Aging Factors: The HRF matures postnatally. In infants, neural activation can evoke a negative BOLD response, indicating an immature NVU where blood flow does not properly match metabolic demand. This response invertes to the canonical positive shape as astrocytes and the vascular network mature [27]. Aging can also alter HRF properties [28].

- Pathological Alterations: Diseases that affect the neurovascular unit profoundly disrupt the HRF. In Alzheimer's Disease, neurovascular uncoupling is a prominent early feature, driven by amyloid-β pathology and astrocyte dysfunction [13] [27]. Similar disruptions are observed in stroke and other neurodegenerative conditions [27].

- Physiological Confounds: Non-neural factors like blood composition (hematocrit), caffeine/alcohol intake, and cardiorespiratory cycles can modulate the HRF shape and confound neuroimaging results [24].

Ignoring HRFv, particularly in resting-state functional connectivity studies, can lead to severe confounds. Apparent correlations or group differences in connectivity can be driven by vascular differences rather than true neural synchrony [24]. For instance, one study noted that HRF differences between women and men led to a 15.4% median error in functional connectivity estimates in a group-level comparison [24].

Application in Drug Development

fMRI and fNIRS have growing roles in the drug development pipeline, where the HRF serves as a critical link between molecular intervention and systems-level brain function.

- Target Engagement and Pharmacodynamics: An fMRI signal can provide indirect evidence of target engagement if a biologically plausible link exists between the drug's molecular target and the resulting hemodynamic change [26]. For example, a drug targeting the NO signaling pathway should manifest as an altered HRF in response to a cognitive task.

- Dose-Response Relationships: fMRI can be used in Phase I trials to establish dose-response and exposure-response relationships, guiding dose selection for later-phase trials [26].

- Biomarker Qualification: While no fMRI biomarker has yet been fully qualified by regulatory agencies like the FDA or EMA, consortia are actively seeking qualification for specific contexts of use, such as stratifying patients with autism spectrum disorder [26].

The Hemodynamic Response Function is more than a mere link between neural activity and blood flow; it is a dynamic and variable reflection of a complex biological process. A deep understanding of its underlying mechanisms, sources of variability, and appropriate measurement methodologies is essential for any researcher or professional using fMRI or fNIRS. As the field moves towards precision mental health and individualized biomarkers, the ability to account for individual HRF signatures—through dense sampling [30], advanced deconvolution [24], and personalized modeling [28]—will be crucial for developing accurate diagnostics and effective, personalized therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Neurovascular Coupling as the Foundation for fMRI and fNIRS Signals

Neurovascular coupling (NVC) describes the fundamental physiological process whereby neuronal activity triggers localized changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF), a mechanism critical for interpreting functional neuroimaging signals [2]. First articulated by Roy and Sherrington in 1890 as the "intrinsic regulation of local CBF," this relationship ensures that active brain regions receive adequate oxygen and nutrients to meet metabolic demands [2]. The neurovascular unit (NVU)—an integrated system comprising neurons, astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and pericytes—orchestrates this precise coordination [13] [2]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), two cornerstone non-invasive neuroimaging technologies, rely entirely on measuring hemodynamic changes consequent to NVC. The fMRI signal primarily reflects the Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast, arising from local changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentration [1] [2]. fNIRS directly measures relative concentration changes of oxyhemoglobin (O2Hb) and deoxyhemoglobin (HHb) in the cortical microvasculature [32] [33]. Understanding NVC is therefore not merely academic but essential for accurately interpreting the neural significance of data acquired with these widespread modalities.

Molecular Mechanisms of Neurovascular Coupling

The signaling pathways of NVC involve a complex, interacting cascade of vasoactive molecules released by neurons and astrocytes in response to synaptic activity.

Key Signaling Pathways and Vasoactive Agents

Upon neuronal activation, neurotransmitters like glutamate are released, initiating a multi-pathway response. Nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator, is synthesized in neurons by neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) following calcium influx. NO raises cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), leading to relaxation and vasodilation [13]. Arachidonic acid metabolites constitute another major pathway. Phospholipase D2 (PLD2) initiates arachidonic acid synthesis, which is subsequently metabolized by cyclooxygenase-1 (COX1) into the vasodilatory prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 acts on the EP4 receptor, a Gs-linked G-protein-coupled receptor on capillary pericytes and VSMCs, increasing intracellular cAMP and causing vasodilation [13]. Potassium ions (K+) also play a crucial role; they are released into the perivascular space through large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BK) channels on astrocytic endfeet, which envelop arterioles. Moderate perivascular K+ concentration (5–20 mM) induces hyperpolarization and dilation of VSMCs [2]. Furthermore, astrocytic calcium signaling is pivotal. Increases in astrocytic Ca2+ can trigger the release of vasoactive agents, with moderate increases promoting dilation and larger spikes potentially causing constriction [2]. These pathways exhibit regional heterogeneity and work in concert, as inhibiting any single pathway does not completely abolish the hemodynamic response [13].

Figure 1: Key Cellular Signaling Pathways in Neurovascular Coupling. The diagram illustrates the major vasodilatory pathways initiated by neuronal activity, involving neurons and astrocytes acting on vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes. NO: Nitric Oxide; nNOS: neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase; sGC: soluble Guanylate Cyclase; cGMP: cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate; BK: Large-conductance Calcium-activated Potassium channel; PGE2: Prostaglandin E2; EETs: Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids; AA: Arachidonic Acid; COX1: Cyclooxygenase-1.

The Hemodynamic Response Function

The net effect of these molecular pathways is the hemodynamic response function (HRF), the characteristic temporal pattern of blood flow and oxygenation changes measured by fMRI and fNIRS. Following neuronal activation, a tightly coordinated sequence occurs: a localized increase in cerebral blood flow manifests after approximately a 2-second delay, peaks around 4-6 seconds post-stimulus, and is followed by a slow return to baseline, sometimes accompanied by a post-stimulus undershoot [32] [2]. This hemodynamic response is characterized by a local increase in O2Hb and a decrease in HHb due to an overcompensatory delivery of oxygenated blood [32] [8]. The BOLD signal in fMRI is sensitive to the resulting decrease in the concentration of paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin [13] [2]. It is crucial to recognize that the HRF is an indirect and delayed measure of neural activity, reflecting a complex integration of synaptic input and local processing more closely than direct neuronal spiking output [2].

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

Empirical studies robustly demonstrate the intensity-dependent nature of neurovascular responses and the validity of combining electrophysiological and hemodynamic measurements.

Intensity-Dependent Amplitude Changes

Research using integrated EEG-fNIRS paradigms has quantitatively linked electrophysiological activity to hemodynamic changes. One study presenting auditory tones of varying intensities (70.9 dB to 94.5 dB) found that increases in tone intensity led to graded enhancements in EEG event-related potential (ERP) components (N1, P2, and N1-P2 peak-to-peak amplitude) [32]. Concurrently, fNIRS measurements showed amplitude increases in O2Hb and decreases in HHb in the auditory and prefrontal cortices [32]. Spearman correlation analysis specifically identified a relationship between the left auditory cortex and N1 amplitude, and the right dorsolateral cortex with P2 amplitude, particularly for HHb concentrations. These findings provide direct evidence for neurovascular coupling by demonstrating a systematic relationship between the amplitude of electrical and hemodynamic responses to sensory stimulation [32].

Table 1: Summary of Intensity-Dependent Neurovascular Responses to Auditory Stimulation

| Experimental Parameter | EEG/ERP Findings | fNIRS Findings | Correlation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Intensity | Increased N1, P2, and N1-P2 peak-to-peak amplitude [32] | Increased O2Hb; Decreased HHb in auditory & prefrontal cortices [32] | Significant Spearman correlations between ERP amplitudes (N1, P2) and hemodynamic concentrations [32] |

| Stimulus Paradigm | Three-tone (77.9, 84.5, 89.5 dB) and five-tone intensities (70.9-94.5 dB) [32] | Hemodynamic changes observed in auditory and prefrontal cortices [32] | Left auditory cortex with N1 amplitude; Right dorsolateral cortex with P2 amplitude [32] |

fNIRS in Cognitive and Clinical Paradigms

fNIRS studies of cognitive-motor interference (CMI) further illuminate NVC in complex tasks. A study involving single and dual cognitive-motor tasks found that the extra cognitive load in the dual-task condition led to decreased neurovascular coupling between fNIRS and EEG signals across theta, alpha, and beta rhythms [18]. This suggests that divided attention can impair the efficiency of the neurovascular response. Clinically, NVC is often impaired; a study of retired rugby players with a history of concussion demonstrated a blunted hemodynamic response during a "Where's Wally" visual search task compared to controls. The control group showed a greater relative increase in O2Hb, while the mTBI group exhibited a reduced O2Hb response and a greater rate of oxygen extraction, indicating altered cerebral metabolic demands following injury [8].

Table 2: Neurovascular Coupling Findings in Cognitive and Clinical Studies

| Study Paradigm | Population | Key NVC Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive-Motor Interference (CMI) [18] | 16 healthy young adults | Decreased EEG-fNIRS coupling in dual-task vs. single-task in theta, alpha, and beta rhythms [18] |

| Sport-Related Concussion (mTBI) [8] | 21 retired rugby players vs. 23 controls | Reduced O2Hb increase in left middle frontal gyrus in mTBI group; Indicated altered metabolic demand [8] |

| Sleep Inertia [34] | 21 healthy adults | Dynamic, time-varying coupling between EEG alpha/vigilance and fMRI BOLD in thalamus/ACC post-awakening [34] |

Methodologies for Investigating Neurovascular Coupling

Experimental Protocols and Designs

Investigating NVC requires carefully designed protocols that can elicit and measure coupled neural and vascular activity.

Auditory Intensity Paradigm: A classic protocol for testing NVC involves presenting participants with tones of different intensities. One experiment used three-tone intensities (77.9 dB, 84.5 dB, and 89.5 dB), each lasting 500 ms and randomly presented 54 times. A second experiment used five intensities (70.9 dB to 94.5 dB) presented in trains of 8 tones. Throughout stimulation, EEG records ERPs (N1, P2), while fNIRS measures hemodynamic changes in the auditory, visual, and prefrontal cortices. This design directly tests the amplitude dependence of both signals and their correlation [32].

Cognitive-Motor Dual-Task Paradigm: To study NVC under cognitive load, experiments can be designed with single motor, single cognitive, and cognitive-motor dual tasks. For example, a grip force tracking task (motor) and a number detection task (cognitive) can be performed separately and concurrently. During these tasks, EEG and fNIRS are recorded simultaneously. The extracted task-related components from both modalities are then analyzed for their correlation to quantify NVC strength, which typically decreases under dual-task conditions [18].

The "Where's Wally" NVC Test: This visual cognitive task is a validated measure of NVC, useful for clinical populations. Participants sit quietly for a 5-minute baseline, then complete five cycles of a task. Each cycle consists of 20 seconds with eyes closed followed by 40 seconds of visually searching for the character "Wally" in a complex image. The fNIRS system, placed over the prefrontal cortex, monitors changes in O2Hb and HHb throughout. This protocol effectively evokes a measurable hemodynamic response related to visual search and attention [8].

Figure 2: Generalized Workflow for Neurovascular Coupling Experiments. The flowchart outlines the common steps in a NVC investigation, from baseline recording and stimulus presentation to concurrent multi-modal signal acquisition and final analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for NVC Research

| Item/Tool | Primary Function in NVC Research |

|---|---|

| fNIRS System (e.g., multi-channel systems like OctaMon) | Non-invasive, silent measurement of relative O2Hb and HHb concentration changes in the cerebral cortex [32] [8]. |

| EEG System (MR-compatible for simultaneous fMRI) | High-temporal-resolution recording of electrical brain activity (ERPs, spectral power) for correlation with hemodynamics [32] [34]. |

| fMRI Scanner | Mapping brain activation via the BOLD signal, an indirect measure of neural activity based on NVC [1] [2]. |

| Pharmacological Agents (e.g., NOS inhibitors, COX inhibitors) | Selective blockade of specific vasoactive pathways (e.g., NO, PGE2) to dissect their contribution to the hemodynamic response [13]. |

| Task-Related Software | Presentation of controlled sensory, motor, or cognitive stimuli (e.g., auditory tones, "Where's Wally" task) to evoke calibrated neural activity [32] [8]. |

| Computational Models (e.g., Balloon model, Dynamic Causal Modeling) | Biophysical models that link neuronal activity to BOLD/fNIRS signals, allowing inference of neural processes from hemodynamic data [1] [35]. |

Neurovascular coupling is the indispensable biological link that allows researchers to infer brain function from hemodynamic signals measured by fMRI and fNIRS. The process is governed by a sophisticated interplay of cellular and molecular mechanisms within the neurovascular unit, resulting in a characteristic hemodynamic response. Quantitative evidence firmly establishes a correlation between the amplitude of electrophysiological events and subsequent vascular changes. Methodologies combining EEG with fNIRS or fMRI are powerful tools for probing this relationship in both healthy and diseased states. A deep understanding of NVC principles is therefore paramount for the correct design, analysis, and interpretation of functional neuroimaging studies across basic neuroscience and clinical drug development.

Methodological Approaches: Applying fMRI and fNIRS to Measure NVC in Basic and Clinical Research

The Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal, the primary contrast mechanism for functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), provides an indirect window into brain function by detecting hemodynamic changes coupled to neural activity. This technical guide details the physiological origin of the BOLD signal within the framework of neurovascular coupling (NVC), the functional hyperemia that links neuronal firing to localized blood flow and oxygenation changes. We summarize key biophysical parameters, present standardized experimental methodologies for its investigation, and visualize core signaling pathways. The document also places BOLD fMRI in the context of multimodal brain research, particularly in conjunction with functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), and provides a practical toolkit of research reagents and solutions. This resource is intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking a current and in-depth understanding of BOLD fMRI fundamentals and applications.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized cognitive neuroscience and clinical brain mapping since its inception in the early 1990s [36]. The vast majority of fMRI studies rely on the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast, a non-invasive measure that allows for the visualization of brain activity by inferring regional neural activity from associated changes in blood oxygenation [37] [38]. The BOLD signal is fundamentally an indirect metric, arising from a complex physiological process known as neurovascular coupling (NVC). NVC describes the mechanism by which neural activity triggers a cascade of events leading to a precisely regulated increase in local cerebral blood flow (CBF), which in turn alters the concentration of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin [7] [39].

Understanding the precise origin and nature of the BOLD signal is critical for its accurate interpretation. While traditionally viewed as a correlate of local excitatory neural activity, recent evidence challenges and refines this perspective, suggesting a more dominant role for specific cell types and revealing that signal decreases are tightly linked to active suppression of spiking activity [37] [40] [38]. Furthermore, the BOLD signal is not a pure measure of neural activity but is influenced by a multitude of physiological factors, including age, cardiorespiratory function, and the integrity of the vascular system [41].

This guide provides an in-depth examination of the BOLD signal. It begins by elucidating its physiological basis, summarizes key quantitative parameters in structured tables, details experimental protocols for its study, and presents visualizations of core pathways. Finally, it explores the synergy between BOLD fMRI and other modalities like fNIRS within the broader context of neurovascular research.

Physiological Basis and Origin of the BOLD Signal

The BOLD signal is a complex, indirect reflection of neural activity, governed by the principles of neurovascular coupling. The following diagram outlines the primary pathway from neural activity to the measured fMRI signal.

Figure 1: The Neurovascular Coupling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the primary sequence of events from neural activity to the measurable BOLD fMRI signal. Key processes include neurovascular coupling, the hemodynamic response, and the resulting change in MR image contrast.

The Hemodynamic Response and BOLD Contrast

The process begins with local neural activity, encompassing both excitatory and inhibitory processes. This activity triggers neurovascular coupling, a process mediated by neurons, astrocytes, and vascular cells, leading to vasodilation and a marked increase in local cerebral blood flow (CBF) [7]. This increase in flow is typically greater than the local oxygen consumption, resulting in a net increase in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and a relative decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the venous capillaries and draining venules [42].

Deoxyhemoglobin is paramagnetic and acts as an intrinsic contrast agent, distorting the local magnetic field and leading to a faster decay of the MR signal (reduced T2* relaxation time). The reduction in deoxyhemoglobin concentration during neural activity thus reduces this distortion, leading to a longer T2 and a stronger MR signal in T2-weighted images—the positive BOLD signal [42] [43].

Cellular Origins of the BOLD Signal

A longstanding assumption was that the BOLD signal primarily reflected input and processing from excitatory neurons. However, a paradigm-shifting model-driven meta-analysis suggests a more complex picture, concluding that inhibitory interneurons drive over 75% of the neurovascular response across studies, while the contribution from excitatory cells may be less than 20% [40]. This indicates that the BOLD signal is heavily weighted toward the activity of local inhibitory circuits.

Furthermore, the relationship between neuronal firing and BOLD signal direction is highly specific. A tight link has been demonstrated in the human association cortex: single neurons in a region showing BOLD activation selectively increase their spiking rate to a preferred stimulus (e.g., faces). Conversely, in an adjacent region showing BOLD deactivation to the same stimulus, the majority of face-selective neurons (over 95%) showed a significant decrease in spike rate, with about a third showing genuine suppression below baseline activity [37] [38]. This evidence strongly indicates that negative BOLD responses can be a direct correlate of active suppression of neural spiking.

Key Parameters and Quantitative Data

The BOLD signal and its underlying physiology can be characterized by several key parameters. The table below summarizes the core parameters of the BOLD response itself, while the subsequent table outlines key metrics related to cerebral metabolism that are often derived or used in conjunction with BOLD fMRI.