Optimizing Feature Selection with Leverage Score Sampling: Advanced Strategies for High-Dimensional Biomedical Data

This article explores the integration of leverage score sampling with established feature selection paradigms to address critical challenges in high-dimensional biomedical data analysis, particularly in pharmaceutical drug discovery.

Optimizing Feature Selection with Leverage Score Sampling: Advanced Strategies for High-Dimensional Biomedical Data

Abstract

This article explores the integration of leverage score sampling with established feature selection paradigms to address critical challenges in high-dimensional biomedical data analysis, particularly in pharmaceutical drug discovery. We examine foundational concepts, methodological applications for genetic and clinical datasets, optimization strategies to enhance stability and efficiency, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from filter, wrapper, embedded, and hybrid FS techniques, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for improving model accuracy, computational efficiency, and interpretability in complex biological data analysis.

Foundations of Feature Selection and the Emergence of Leverage Score Sampling

The Critical Role of Feature Selection in High-Dimensional Biomedical Data

In the realm of biomedical research, technological advancements have led to the generation of massive datasets where the number of features (p) often dramatically exceeds the number of samples (n). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), for instance, can contain up to a million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with only a few thousand samples [1]. This "curse of dimensionality" presents significant challenges for building accurate predictive models for disease risk prediction [1]. Feature selection addresses this problem by identifying and extracting only the most "informative" features while removing noisy, irrelevant, and redundant features [1].

Effective feature selection is not merely a preprocessing step; it is a critical component that increases learning efficiency, improves predictive accuracy, reduces model complexity, and enhances the interpretability of learned results [1]. In biomedical contexts, the features incorporated into predictive models following selection are typically assumed to be associated with loci that are mechanistically or functionally related to underlying disease etiology, thereby potentially illuminating biological processes [1].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Q1: My machine learning model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen validation data. What might be causing this overfitting?

A1: Overfitting in high-dimensional biomedical data typically occurs when the model learns noise and random fluctuations instead of true underlying patterns. To address this:

- Implement robust feature selection: Use methods that effectively remove irrelevant and redundant features. Dimensionality reduction through feature selection helps prevent models from overfitting to noise in the training data [1].

- Apply cross-validation: Perform feature selection within each cross-validation fold rather than on the entire dataset before splitting to avoid data leakage [1].

- Increase sample size: When possible, utilize sampling methods like leverage score sampling to select representative subsets that maintain statistical properties of the full dataset [2].

Q2: How can I handle highly correlated features in my genomic dataset?

A2: Highly correlated features (e.g., SNPs in linkage disequilibrium) are common in biomedical data and can degrade model performance:

- Account for redundancy: Feature selection techniques should ideally select one representative feature from each correlated cluster. For genetic data, this might mean selecting the SNP with the highest association signal to represent an entire linkage disequilibrium block [1].

- Use multivariate methods: Unlike univariate filter techniques that evaluate features independently, employ methods that consider interactions between features to properly handle correlated predictors [1].

- Consider ensemble approaches: Implement ensemble feature selection strategies that integrate multiple selection techniques to identify stable features despite correlations [3].

Q3: What should I do when my feature selection method fails to identify biologically relevant features?

A3: When selected features lack biological plausibility:

- Reevaluate selection criteria: Traditional methods like univariate filtering may miss features that are only relevant through interactions. Implement methods that detect epistatic effects [1].

- Incorporate domain knowledge: Use biologically-informed selection constraints or weighted scoring that prioritizes features with known biological significance.

- Try model-free screening: Methods like weighted leverage score screening perform effectively without pre-specified models and can identify relevant features under various underlying relationships [2].

Q4: How can I improve computational efficiency when working with extremely high-dimensional data?

A4: Computational challenges are common with high-dimensional biomedical data:

- Implement efficient screening: Use scalable one-pass algorithms like weighted leverage screening for initial dimension reduction before applying more computationally intensive methods [2].

- Utilize nature-inspired algorithms: Methods like the Bacterial Foraging-Shuffled Frog Leaping Algorithm (BF-SFLA) balance global and local optimization efficiently [4].

- Leverage ensemble methods: Scalable ensemble feature selection strategies have demonstrated the ability to reduce feature sets by over 50% while maintaining or improving classification performance [3].

Method Selection Guidance

Q5: How do I choose between filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection methods?

A5: The choice depends on your specific constraints and goals:

- Filter methods: Use when computational efficiency is paramount and you need scalability for ultra-high-dimensional data. These are independent of learning algorithms but may miss feature interactions [1].

- Wrapper methods: Choose when model performance is the primary concern and you have sufficient computational resources. These evaluate feature subsets using the actual learning algorithm but are computationally intensive [4].

- Embedded methods: Implement when you want a balance between filter and wrapper approaches. These perform feature selection as part of the model training process [1].

Q6: When should I use leverage score sampling versus traditional feature selection methods?

A6: Leverage score sampling is particularly advantageous when:

- Working with massively high-dimensional data where traditional methods fail computationally [2].

- You need theoretical guarantees on performance approximation [2].

- Dealing with model-free settings where the relationship between predictors and response is complex or unknown [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different feature selection approaches based on empirical studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

| Method | Accuracy Improvement | Feature Reduction | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble FS [3] | Maintained or increased F1 scores by up to 10% | Over 50% decrease in certain subsets | High | Multi-biometric healthcare data, clinical applications |

| BF-SFLA [4] | Improved classification accuracy | Significant feature subset identification | Fast calculation speed | High-dimensional biomedical data with weak correlations |

| Weighted Leverage Screening [2] | Consistent inclusion of true predictors | Effective dimensionality reduction | Highly computationally efficient | Model-free settings, general index models |

| Marginal Correlation Ranking [1] | Limited with epistasis | Basic filtering | High | Preliminary screening with nearly independent features |

| Wrapper Methods (IGA, IPSO) [4] | Good accuracy | Effective subset identification | Computationally intensive | When accuracy is prioritized over speed |

Table 2: Data Type Considerations for Feature Selection

| Data Type | Key Challenges | Recommended Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| SNP Genotype Data [1] | Linkage disequilibrium, epistasis, small effect sizes | Multivariate methods, interaction-aware selection |

| Medical Imaging Data [3] | High dimensionality, spatial correlations | Ensemble selection, domain-informed constraints |

| Multi-biometric Data [3] | Heterogeneous sources, different scales | Integrated ensemble approaches, modality-specific selection |

| Clinical and Omics Data | Mixed data types, missing values | Adaptive methods, imputation-integrated selection |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Weighted Leverage Score Screening Protocol

Weighted leverage score screening provides a model-free approach for high-dimensional data [2]:

Step 1: Data Preparation

- Standardize the design matrix X to have zero mean and unit variance for each feature.

- Ensure the response variable Y is appropriately formatted for the analysis.

Step 2: Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)

- Compute the rank-d singular value decomposition of X: X ≈ UΛV^T

- Where U ∈ ℝ^(n×d) and V ∈ ℝ^(p×d) are column orthonormal matrices, and Λ ∈ ℝ^(d×d) is a diagonal matrix.

Step 3: Leverage Score Calculation

- Compute left leverage scores as ||U(i)||²₂ for each row i

- Compute right leverage scores as ||V(j)||²₂ for each column j

Step 4: Weighted Leverage Score Computation

- Integrate both left and right leverage scores to compute weighted leverage scores for each predictor.

- The specific weighting scheme depends on the data structure and research question.

Step 5: Feature Screening

- Rank features based on their weighted leverage scores.

- Select the top k features, where k is determined by a BIC-type criterion or domain knowledge.

Step 6: Model Building and Validation

- Build the final model using only selected features.

- Validate using cross-validation or external datasets.

Ensemble Feature Selection Protocol for Healthcare Data

This protocol implements the waterfall selection strategy for multi-biometric healthcare data [3]:

Step 1: Tree-Based Feature Ranking

- Apply tree-based algorithms (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) to rank features by importance.

- Use out-of-bag error estimates for robust importance calculation.

Step 2: Greedy Backward Feature Elimination

- Start with the full feature set.

- Iteratively remove the least important feature based on model performance.

- Use cross-validation to assess performance at each step.

Step 3: Subset Generation and Merging

- Generate multiple feature subsets through the elimination process.

- Combine subsets using a specific merging strategy to produce a single set of clinically relevant features.

Step 4: Validation with Multiple Classifiers

- Test the selected feature set with different classifiers (SVM, Random Forest).

- Evaluate using metrics relevant to clinical applications (F1 score, AUC, accuracy).

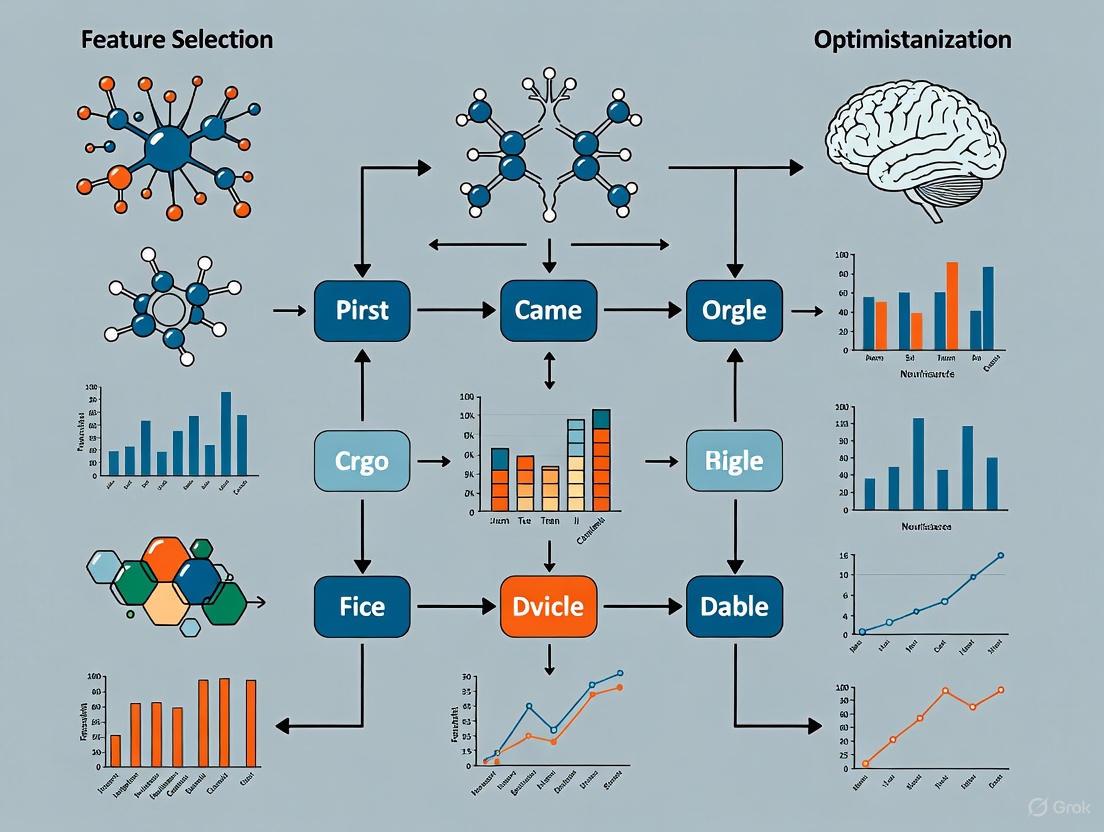

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

General Machine Learning Workflow with Feature Selection

Nature-Inspired Feature Selection Algorithm

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Weighted Leverage Score Algorithm [2] | Model-free variable screening | High-dimensional settings with complex relationships |

| Ensemble Feature Selection Framework [3] | Integrated feature ranking and selection | Multi-biometric healthcare data analysis |

| BF-SFLA Implementation [4] | Nature-inspired feature optimization | High-dimensional biomedical data with weak correlations |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [2] | Matrix decomposition for leverage calculation | Dimensionality reduction and structure discovery |

| BIC-type Criterion [2] | Determining number of features to select | Model selection with complexity penalty |

| Cross-Validation Framework [1] | Performance estimation and model validation | Preventing overfitting in high-dimensional settings |

| Tree-Based Algorithms [3] | Feature importance ranking | Initial feature screening in ensemble methods |

Feature selection is a critical preprocessing step in machine learning, aimed at identifying the most relevant features from a dataset to improve model performance, reduce overfitting, and enhance interpretability [5] [6]. This is particularly vital in high-dimensional domains, such as medical research and drug development, where the "curse of dimensionality" can severely degrade model generalization [7] [8]. For researchers focusing on advanced techniques like leverage score sampling, a firm grasp of the feature selection taxonomy is indispensable for optimizing computational efficiency and analytical robustness [9] [10].

This guide provides a structured overview of the main feature selection categories—Filter, Wrapper, Embedded, and Hybrid methods—presented in a troubleshooting format to help you diagnose and resolve common issues in your experiments.

FAQ: Core Concepts of Feature Selection

What is the fundamental difference between Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded methods?

The distinction lies in how the feature selection process interacts with the learning algorithm and the criteria used to evaluate feature usefulness.

- Filter Methods assess features based on their intrinsic, statistical properties (e.g., correlation with the target variable) without involving any machine learning model [5] [11]. They are model-agnostic.

- Wrapper Methods use the performance of a specific predictive model (e.g., its accuracy) as the objective function to evaluate and select feature subsets. They "wrap" themselves around a model [5] [11].

- Embedded Methods perform feature selection as an integral part of the model training process itself. The learning algorithm has its own built-in mechanism for feature selection [5] [11] [12].

- Hybrid Methods combine a Filter and a Wrapper approach. Typically, a Filter method is first used to reduce the search space, and a Wrapper method is then applied to find the optimal subset from the reduced feature set [12].

When should I prefer a Filter method over a Wrapper method?

Your choice should be guided by your project's constraints regarding computational resources, dataset size, and the need for interpretability.

- Use Filter methods when: Working with very high-dimensional data (e.g., thousands of features), computational efficiency is a priority, or you need a fast, model-agnostic baseline [5]. They are excellent for an initial feature screening.

- Use Wrapper methods when: You have a smaller dataset, computational cost is less of a concern, and your primary goal is to maximize the predictive performance for a specific model, even at the risk of higher computational load and overfitting [5].

How do Embedded methods integrate feature selection into the learning process?

Embedded methods leverage the properties of the learning algorithm to select features during model training. A prime example is L1 (LASSO) regularization [11]. In linear models, L1 regularization adds a penalty term to the cost function equal to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients. This penalty forces the model to shrink the coefficients of less important features to zero, effectively performing feature selection as the model is trained [11]. Tree-based models, like Random Forest, are another example, as they provide feature importance scores based on how much a feature decreases impurity across all trees [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: My feature selection is computationally expensive and does not scale.

- Possible Cause: Using a wrapper method (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination) with a complex model and a large feature set.

- Solution:

- Initial Filter: Apply a fast filter method (e.g., correlation, mutual information) to reduce the feature space drastically before employing a wrapper or embedded method [12].

- Taxonomic Pre-grouping: For specialized data like trajectories, use a taxonomy-based approach to group features (e.g., into geometric and kinematic categories) before selection. This reduces the combinatorial search space [9].

- Switch Method: Consider using embedded methods like Lasso or tree-based models, which can be more efficient than wrappers while still being model-specific [5] [11].

Problem: After feature selection, my model performance is poor or unstable.

- Possible Cause: The selected feature subset is overfitted to your training data, or you have selected a method inappropriate for your data size.

- Solution:

- Re-evaluate Method Choice: Refer to the performance table below. For example, one study found Lasso to underperform significantly compared to variance-based filter methods on certain tasks [14].

- Cross-Validation: Ensure you perform feature selection within each fold of the cross-validation loop, not before it. Doing it beforehand causes information leakage from the validation set into the training process, leading to over-optimistic performance and poor generalization.

- Benchmark: For some models and data types, like ecological metabarcoding data, tree ensemble models (e.g., Random Forest) without explicit feature selection can be surprisingly robust. It's worth benchmarking a "no selection" baseline [13].

Problem: I cannot explain why certain features were selected.

- Possible Cause: Many powerful wrapper and embedded methods are "black boxes" in terms of selection rationale.

- Solution:

- Use Interpretable Methods: Start with filter methods, as they provide clear, statistical reasons for feature importance (e.g., a high correlation coefficient) [5].

- Adopt a Structured Taxonomy: Implement a taxonomy-based framework. By pre-categorizing features (e.g., speed, acceleration, curvature), you can understand which type of features the model deems important, adding a layer of interpretability [9].

- Leverage Rough Set Theory: In domains with vague or imprecise data (common in medicine), Rough Feature Selection (RFS) methods use concepts like approximation to provide mathematical interpretability for selected features [7].

Experimental Performance & Data

The following table summarizes the relative performance of different feature selection methods based on an empirical benchmark using R-squared values across varying data sizes [14].

Table 1: Performance of Feature Selection Methods Across Data Sizes

| Method Category | Specific Method | Relative R-squared Performance | Sensitivity to Data Size | Performance Fluctuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter | Variance (Var) |

Best | Medium | Low |

| Mutual Information | Medium | Low | High | |

| Wrapper | Stepwise | High | High | High |

| Forward | Medium | High | High | |

| Backward | Medium | Medium | Medium | |

| Simulated Annealing | Medium | Low | Low | |

| Embedded | Tree-based | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Lasso | Worst | Low | - |

Workflow & Method Selection Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for feature selection, incorporating best practices from the troubleshooting guide.

This diagram provides a logical map of the three main feature selection categories and their core characteristics to aid in method selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Feature Selection Research

| Tool / Technique | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| L1 (LASSO) Regularization | An embedded method that performs feature selection by driving the coefficients of irrelevant features to zero during model training [11]. | Identifying the most critical gene expressions from high-dimensional microarray data for cancer classification [8]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | A wrapper method that recursively removes the least important features and re-builds the model until the optimal subset is found [13]. | Enhancing the performance of Random Forest models on ecological metabarcoding datasets by iteratively removing redundant taxa [13]. |

| Random Forest / Tree-based | Provides built-in feature importance scores (embedded) based on metrics like Gini impurity or mean decrease in accuracy [13]. | Serving as a robust benchmark model that often performs well on high-dimensional biological data even without explicit feature selection [13]. |

| Rough Set Theory (RFS) | A filter method that handles vagueness and uncertainty by selecting features that preserve the approximation power of a concept in a dataset [7]. | Feature selection in medical diagnosis where data can be incomplete or imprecise, requiring mathematical interpretability [7]. |

| Leverage Score Sampling | A statistical technique to identify the most influential data points (rows) in a matrix, which can be adapted for feature (column) sampling and reduction [10]. | Pre-processing for large-scale regression problems to reduce computational cost while preserving the representativeness of the feature space [10]. |

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between correlation and mutual information in feature selection?

A1: Correlation measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables. Mutual information (MI) is a more general measure that quantifies the amount of information obtained about one random variable by observing another, capturing any kind of statistical dependency, including non-linear relationships [15] [16]. In practice, correlation is a special case of mutual information when the relationship is linear. For feature selection, MI can identify useful features that correlation might miss.

Q2: My model is overfitting despite having high cross-validation scores on my training feature set. Could redundant features be the cause?

A2: Yes. Redundant features, which are highly correlated or share the same information with other features, are a primary cause of overfitting [17]. They can lead to issues like multicollinearity in linear models and make the model learn spurious patterns in the training data that do not generalize. Using mutual information for feature selection can help identify and eliminate these redundancies.

Q3: When should I prefer filter methods over wrapper methods for feature selection?

A3: Filter methods, which include mutual information and correlation-based selection, are ideal for your initial data exploration and when working with high-dimensional datasets where computational efficiency is crucial [18] [17]. They are fast, model-agnostic, and resistant to overfitting. Wrapper methods should be used when you have a specific model in mind and computational resources allow for a more precise, albeit slower, search for the optimal feature subset [17].

Q4: How can I validate that my feature selection process is not discarding important features that work well together?

A4: This is a key limitation of filter methods that evaluate features individually [18]. To validate your selection:

- Use Wrapper Methods: Apply Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or sequential feature selection. These methods evaluate feature subsets and can capture feature interactions [18] [17].

- Compare Model Performance: Train your final model on the feature subset selected by the filter method and compare its performance on a hold-out test set against a model trained on the full feature set or a subset from a wrapper method. A significant drop in performance may indicate that important interactive features were discarded.

Q5: What does a mutual information value of zero mean?

A5: A mutual information value of I(X;Y) = 0 indicates that the two random variables, X and Y, are statistically independent [15]. This means knowing the value of X provides no information about the value of Y, and vice versa. Their joint distribution is simply the product of their individual distributions.

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Problem: Poor Model Performance After Feature Selection

Symptoms:

- Decreased accuracy, precision, or recall on the test set.

- Model fails to converge or converges too slowly.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Insufficient Informative Features: The feature selection process may have been too aggressive, removing not only noise but also weakly predictive features. | Relax the selection threshold. For MI, lower the score threshold for keeping a feature. Re-introduce features and monitor validation performance. |

| 2 | Removed Interactive Features: The selection method (especially univariate filters) discarded features that are only predictive in combination with others [18]. | Use a multivariate feature selection method like RFE or tree-based embedded methods that can account for feature interactions [18] [17]. |

| 3 | Data-Model Incompatibility: The selected features are not compatible with the model's assumptions (e.g., using non-linear features for a linear model). | Align the feature selection method with the model. For linear models, correlation might be sufficient. For tree-based models or neural networks, use mutual information. |

### Problem: Inconsistent Feature Selection Results

Symptoms:

- The set of selected features varies significantly between different random splits of the dataset.

- Small changes in the data lead to large changes in the selected features.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | High Variance in Data: The dataset may be too small or have high inherent noise, making statistical estimates like MI unstable. | Use resampling methods (e.g., bootstrap) to perform feature selection on multiple data samples. Select features that are consistently chosen across iterations. |

| 2 | Poorly Chosen Threshold: The threshold for selecting features (e.g., top k) may be arbitrary and sensitive to data fluctuations. | Use cross-validated feature selection (e.g., RFECV) [18] to automatically determine the optimal number of features. Validate the stability on a held-out dataset. |

## Experimental Protocols & Quantitative Data

### Protocol 1: Measuring Feature-Target Associations with Filter Methods

This protocol details how to calculate correlation and mutual information for feature selection.

1. Objective: To quantify the linear and non-linear dependency between each feature and the target variable.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Software: Python with

scikit-learn,scipy,numpy,pandas. - Dataset: Your preprocessed feature matrix (

X) and target vector (y).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Preprocessing. Ensure all features are numerical. Encode categorical variables and handle missing values appropriately.

- Step 2: Correlation Calculation. For linear relationships, calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between each feature and the target.

- Step 3: Mutual Information Calculation. For non-linear relationships, calculate the mutual information score for each feature.

- Step 4: Feature Selection. Rank features based on their correlation and MI scores. Select the top

kfeatures from each list or use a threshold.

4. Data Analysis: Structure your results in a table for clear comparison.

Table 1: Example Feature-Target Association Scores for a Synthetic Dataset

| Feature Name | Correlation Coefficient (with target) | Mutual Information Score (with target) | Selected (Corr > 0.3) | Selected (MI > 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| feature_1 | -0.35 | 0.12 | Yes | Yes |

| feature_3 | 0.28 | 0.09 | No | Yes |

| feature_5 | -0.58 | 0.21 | Yes | Yes |

| feature_8 | 0.10 | 0.06 | No | Yes |

| feature_11 | 0.35 | 0.15 | Yes | Yes |

| feature_15 | -0.48 | 0.18 | Yes | Yes |

Note: The specific thresholds (0.3 for correlation, 0.05 for MI) are examples and should be tuned for your specific dataset [18].

### Protocol 2: Wrapper Method for Robust Feature Selection using RFE

This protocol uses a wrapper method to find an optimal feature subset by training a model repeatedly.

1. Objective: To select a feature subset that maximizes model performance and accounts for feature interactions.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Software: Python with

scikit-learn. - Model: A base estimator (e.g.,

RandomForestClassifier,LogisticRegression).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Initialize the RFE object. Specify the model and the number of features to select.

- Step 2: Fit the Selector. Fit the RFE selector to your data.

- Step 3: Get Selected Features. Extract the mask or names of the selected features.

- Step 4 (Recommended): Use RFE with Cross-Validation. To find the optimal number of features automatically, use

RFECV.

## Workflow Visualization

Below is a workflow diagram that outlines the logical decision process for choosing and applying feature selection methods within a research project.

## Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and their functions for implementing information-theoretic feature selection.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Feature Selection Research

| Tool / Library | Function in Research | Key Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

scikit-learn (sklearn) |

Provides a unified API for filter, wrapper, and embedded methods [18] [17]. | Calculating mutual information (mutual_info_classif), performing RFE (RFE), and accessing feature importance from models. |

SciPy (scipy) |

Offers statistical functions for calculating correlation coefficients and other dependency measures. | Computing Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlation coefficients for initial feature screening. |

| statsmodels | Provides comprehensive statistical models and tests, including advanced diagnostics. | Calculating Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to detect multicollinearity among features in an unsupervised manner [17]. |

| D3.js (d3-color) | A library for color manipulation in visualizations, ensuring accessibility and clarity [19]. | Creating custom charts and diagrams for presenting feature selection results, with compliant color contrast. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are leverage scores and what is their statistical interpretation? Leverage scores are quantitative measures that assess the influence of individual data points within a dataset. For a data matrix, the leverage score of a row indicates how much that particular data point deviates from the others. Formally, if you have a design matrix X from a linear regression model, the leverage score for the i-th data point is the i-th diagonal element of the "hat matrix" H = X(X'X)⁻¹X', denoted as hᵢᵢ [10]. Statistically, points with high leverage scores are more "exceptional," meaning you can find a vector that has a large inner product with that data point relative to its average inner product with all other rows [20]. These points have the potential to disproportionately influence the model's fit.

Why is leverage score sampling preferred over uniform sampling for large-scale problems? Uniform sampling selects data points with equal probability, which can miss influential points in skewed datasets and lead to inaccurate model approximations. Leverage score sampling is an importance sampling method that preferentially selects more influential data points [20] [21]. This results in a more representative subsample, ensuring that the resulting approximation is provably close to the full-data solution, which is crucial for reliability in scientific and drug development applications [22].

How do I compute leverage scores for a given data matrix X? You can compute the exact leverage scores via the following steps [10] [20]:

- Compute an orthogonal basis U for the column space of X. For example, this can be done via a QR decomposition.

- For each row i in the matrix, its leverage score τᵢ is the squared ℓ₂-norm of the i-th row of U: τᵢ = ||uᵢ||₂². For a full-rank matrix X with d columns, the sum of all leverage scores equals d. While exact computation can be computationally expensive (O(nd²)), there are efficient algorithms to approximate them [22].

What are the common thresholds for identifying high-leverage points? A commonly used rule-of-thumb threshold is 2k/n, where k is the number of predictors (features) and n is the total sample size [10]. Points with leverage scores greater than this threshold are often considered to have high leverage. However, this is a general guideline. In the context of sampling for approximation, points are typically selected with probabilities proportional to their leverage scores, not just by a deterministic threshold [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Computational Cost of Exact Leverage Score Calculation

- Symptoms: Calculation is too slow for datasets with a very large number of rows (n) and columns (d), as the complexity is O(nd²) [22].

- Solution: Use approximate leverage scores.

- Methodology: Randomized algorithms can efficiently compute approximations of the leverage scores in O(nd log(d) + poly(d)) time, which is significantly faster for n ≫ d [22].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Use random projection matrices (e.g., Johnson-Lindenstrauss transforms) to project the rows of the orthogonal basis U into a lower-dimensional space.

- Compute the norms of the projected rows to obtain the approximate scores.

- Verification: Theoretical guarantees ensure that with high probability, the approximate scores are within a multiplicative factor of the exact scores, which is sufficient for producing a high-quality subsample [22].

Problem: Sampling Algorithm Yields Poor Model Performance

- Symptoms: The model trained on the subsampled data generalizes poorly or provides an inaccurate approximation of the full-data solution.

- Solution: Ensure correct sampling probabilities and rescaled weights.

- Methodology: The standard approach is Bernoulli sampling, where each row i is assigned a probability pᵢ = min(1, c ⋅ τᵢ) for an oversampling parameter c ≥ 1 [20].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Calculate or approximate the leverage score τᵢ for each row.

- For each row, sample it independently with probability pᵢ.

- If a row is sampled, include it in the subsampled data matrix X̃ and target vector ỹ (if applicable) as xᵢ/√pᵢ and yᵢ/√pᵢ. This rescaling is critical as it makes the subsampled problem an unbiased estimator of the full-data problem [20].

- Verification: Check the spectral properties (e.g., singular values) of the subsampled matrix. Theory guarantees that if c = O(d log d / ε²), the solution to the subsampled least-squares problem will satisfy the relative error bound in Eq. (1.1) with high probability [20].

Problem: Handling Data with Temporal Dependencies

- Symptoms: Standard leverage score sampling performs poorly on time-series data because it ignores temporal dependencies.

- Solution: Use model-specific leverage scores, such as those defined for the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model.

- Methodology: The Leverage Score Sampling (LSS) method for VAR models defines scores based on the dependence structure to select influential past observations [21].

- Experimental Protocol:

- For a K-dimensional VAR(p) model, form the predictor vector xt = (y'{t-1}, ..., y'{t-p})'.

- The leverage score for time t is defined as l{tt} = x't (X'X)⁻¹ xt, where X is the matrix of all x_t.

- Sample time points with probability proportional to these scores for online parameter estimation.

- Verification: The LSS method provides a theoretical guarantee of improved estimation efficiency for the model parameter matrix compared to naive sampling [21].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Active Linear Regression via Leverage Score Sampling

This protocol is designed to solve min‖Ax - b‖₂ while observing as few entries of b as possible, which is common in experimental design [20].

- Input: Data matrix A ∈ ℝ^{n×d} (n ≫ d), query access to target vector b ∈ ℝ^n, error parameter ε.

- Compute Leverage Scores: Calculate the leverage score τᵢ for each row aᵢ of A using an orthogonal basis for its column space.

- Determine Sampling Probabilities: Set pᵢ = min(1, c ⋅ τᵢ), where c = O(d log d + d/ε).

- Sample and Rescale: Construct à and b̃ by including each row with probability pᵢ. For each selected row i, add aᵢ/√pᵢ and bᵢ/√pᵢ to à and b̃, respectively.

- Solve Subproblem: Compute x̃ = argmin‖Ãx - b̃‖₂.

Table 1: Computational Complexity Comparison for Different Matrix Operations

| Operation | Full Data Complexity | Sampled Data Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Leverage Score Calculation | O(nd²) [22] | O(nd log(d) + poly(d)) (approximate) [22] |

| Solve Least-Squares | O(nd²) | O(sd²), where s is the sample size |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Leverage Score Sampling Experiments

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value / Rule | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oversampling Parameter | c | O(d log d + d/ε) | Controls the size of the subsample [20] |

| Sample Size | s | O(d log d + d/ε) | Expected number of selected rows |

| High-Leverage Threshold | - | 2k/n [10] | Rule of thumb for identifying influential points |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Leverage Score Sampling for Linear Regression

Relationship Between Data Points, Leverage, and Sampling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Leverage Score Research

| Tool / Algorithm | Function | Key Reference / Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|

| QR Decomposition | Computes an orthogonal basis for the column space of X, used for exact leverage score calculation. | Standard linear algebra library (e.g., LAPACK). |

| Randomized Projections | Efficiently approximates leverage scores for very large datasets to avoid O(nd²) cost. | [22] |

| Bernoulli Sampling | The core independent sampling algorithm where each row is selected based on its probability pᵢ. | [20] |

| Pivotal Sampling | A non-independent sampling method that promotes spatial coverage, can improve sample efficiency. | [20] |

| Wolfe-Atwood Algorithm | An underlying algorithm for solving the Minimum Volume Covering Ellipsoid (MVCE) problem, used in conjunction with leverage score sampling. | [22] |

Addressing the Curse of Dimensionality in Genomics and Clinical Datasets

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the "Curse of Dimensionality" and why is it a critical problem in genomics?

The "Curse of Dimensionality" refers to a set of phenomena that occur when analyzing data in high-dimensional spaces (where the number of features P is much larger than the number of samples N, or P >> N). In genomics, this is critical because technologies like whole genome sequencing can generate millions of features (e.g., genomic variants, gene expression levels) for only hundreds or thousands of patient samples [23] [24] [25]. This creates fundamental challenges for analysis:

- Data Sparsity: Points move far apart in high dimensions, making local neighborhoods sparse and density estimation difficult [24].

- Distance Concentration: The distances between all pairs of points become similar, hampering clustering and nearest-neighbor algorithms [24].

- Model Overfitting: The risk of finding spurious patterns increases dramatically, leading to models that fail to generalize to new data [23] [26].

FAQ 2: How does high-dimensional data impact the real-world performance of AI models in clinical settings? High-dimensional data often leads to unpredictable AI model performance after deployment, despite promising results during development [23]. For example, Watson for Oncology was trained on high-dimensional patient data but with small sample sizes (e.g., 106 cases for ovarian cancer). This created "dataset blind spots" – regions of feature space without training samples – leading to incorrect treatment recommendations when encountering these blind spots in real clinical practice [23]. The expanding blind spots with increasing dimensions make accurate performance estimation during development extremely challenging.

FAQ 3: What are the primary strategies to overcome the curse of dimensionality in genomic datasets? Two primary strategies are feature selection and dimension reduction:

- Feature Selection: Identifies and retains the most relevant features, discarding irrelevant or redundant ones. This directly reduces dimensionality and is a focus of ongoing research with hybrid AI methods [26].

- Dimension Reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) project data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving key patterns and variability [27].

- Specialized Algorithms: Using algorithms robust to high dimensions, such as Random Forests, which have a reduced risk of overfitting in

P >> Nsituations [25].

FAQ 4: What are leverage scores and how can they help in feature selection? Leverage scores offer a geometric approach to data valuation. For a dataset represented as a matrix, the leverage score of a data point quantifies its structural influence – essentially, how much it extends the span of the dataset and contributes to its effective dimensionality [28]. Points with high leverage scores often lie in unique directions in feature space. When used for sampling, they help select a subset of data points that best represent the overall data structure, improving sampling efficiency for downstream tasks like model training [28].

FAQ 5: My model has high accuracy on the training set but fails on new data. Could the curse of dimensionality be the cause? Yes, this is a classic symptom of overfitting, which the curse of dimensionality greatly exacerbates [23]. When the number of features is very large relative to the number of samples, models can memorize noise and spurious correlations in the training data rather than learning the true underlying patterns. This results in poor generalization. Mitigation strategies include employing robust feature selection, using simpler models, increasing sample size if possible, and applying rigorous validation techniques like nested cross-validation [23] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization After Deployment Symptoms: High performance on training/validation data but significant performance drop on new, real-world data. Solutions:

- Audit Training Data Coverage: Analyze your high-dimensional training data for "blind spots." Use visualization techniques like PCA to check if new data falls outside the coverage of your training set [23].

- Implement Robust Feature Selection: Apply feature selection methods to reduce dimensionality and focus on the most informative variables. Refer to the Experimental Protocols section for methodologies [26].

- Re-evaluate Sample Size: The complexity of a problem should be matched by an adequate sample size. If adding new samples is not feasible, consider simplifying the model or the problem formulation itself [23].

Problem: Computational Bottlenecks with High-Dimensional Data Symptoms: Models take impractically long to train, or algorithms run out of memory. Solutions:

- Utilize Scalable Algorithms: Employ algorithms specifically designed for high-dimensional data. For example, VariantSpark is a Random Forest implementation that can scale to millions of genomic features [25].

- Leverage Dimensionality Reduction: Use PCA or similar techniques as a pre-processing step to reduce the number of features input into your model [27].

- Apply Leverage Score Sampling: Before training a complex model, use leverage scores to select a representative subset of the data, reducing computational load while preserving information [28].

Problem: Unstable or Meaningless Results from Clustering Symptoms: Clusters do not reflect known biology, change drastically with small perturbations in the data, or all points appear equally distant. Solutions:

- Verify the "Distance Concentration" Effect: This is a known property of high-dimensional data where pairwise distances become similar [24]. Confirm this by examining the distance distribution.

- Reduce Dimensionality Before Clustering: Perform clustering in a lower-dimensional space (e.g., on the first several principal components) rather than on the raw, high-dimensional data [27].

- Use Domain Knowledge to Validate: Ensure that any resulting clusters can be biologically interpreted and are not just artifacts of the algorithm.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hybrid Feature Selection for High-Dimensional Classification

This protocol is adapted from recent research on optimizing classification for high-dimensional data using hybrid feature selection (FS) frameworks [26].

Objective: To identify the most relevant feature subset from a high-dimensional dataset to improve classification accuracy and model generalizability.

Methodology Overview:

- Input: High-dimensional dataset (e.g., gene expression, genomic variants).

- Feature Selection:

- Apply one or more hybrid FS algorithms (e.g., TMGWO, ISSA, BBPSO) to evaluate feature importance.

- These algorithms combine metaheuristic optimization (like Grey Wolf Optimization or Particle Swarm Optimization) with local search or mutation strategies to effectively explore the vast feature space.

- Classification:

- Train multiple classifiers (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, KNN) on the selected feature subset.

- Compare their performance against models trained on the full feature set.

Key Steps:

- Data Preparation: Clean data, handle missing values, and normalize if necessary.

- Apply Feature Selection Algorithm:

- If using TMGWO (Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization): Utilize the two-phase mutation strategy to balance exploration and exploitation in the search for the optimal feature subset [26].

- If using BBPSO (Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization): Employ the velocity-free PSO mechanism to efficiently traverse the binary feature space [26].

- Evaluate Feature Subset: Use a predefined criterion (e.g., classification accuracy with a simple classifier) to evaluate the quality of the selected feature subset.

- Train Final Model: Using the selected features, train a chosen classifier on the training set.

- Validation: Assess model performance on a held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall.

Expected Outcomes: The hybrid FS approach is expected to yield a compact set of features, leading to a model with higher accuracy and better generalization compared to using all features [26].

Protocol 2: Leverage Score Sampling for Data Valuation and Subset Selection

This protocol uses geometric data valuation to select an influential subset of data points [28].

Objective: To compute the importance of each datapoint in a dataset and select a representative subset for efficient downstream modeling.

Methodology Overview:

- Input: Data matrix

X(e.g.,nsamples xdfeatures after an initial feature selection step). - Compute Leverage Scores: Calculate the statistical leverage score for each datapoint.

- Normalize Scores: Convert scores to a probability distribution.

- Sample Subset: Sample a subset of datapoints based on these probabilities.

Key Steps:

- Standardize the Data Matrix: Ensure the data is standardized (mean-centered and scaled).

- Compute Leverage Scores:

- Calculate the hat matrix:

H = X(X^T X)^{-1} X^T. - The leverage score for the

i-th datapoint is thei-th diagonal element ofH:l_i = H[i,i][28].

- Calculate the hat matrix:

- Handle Singularity with Ridge Leverage:

- If

X^T Xis near-singular (common in high dimensions), use ridge leverage scores:l_i(λ) = x_i^T (X^T X + λI)^{-1} x_i, whereλis a regularization parameter [28].

- If

- Normalize Scores:

π_i = l_i / Σ_j l_jto create a probability distribution over the datapoints [28]. - Sample a Subset: Sample a subset

Sof datapoints where each pointiis included with probability proportional toπ_i.

Expected Outcomes: This method provides a geometrically-inspired value for each datapoint. Training a model on the sampled subset S is theoretically guaranteed to produce results close to the model trained on the full dataset, offering significant computational savings [28].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Properties and Analytical Impacts of High-Dimensional Data

This table summarizes how the inherent properties of high-dimensional data create challenges for statistical and machine learning analysis [24].

| Property | Description | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Points are far apart | The average distance between points increases with dimensions; data becomes sparse. | Clusters that exist in low dimensions can disappear; density-based methods fail [24]. |

| Points are on the periphery | Data points move away from the center and concentrate near the boundaries of the space. | Accurate parameter estimation (e.g., for distribution fitting) becomes difficult [24]. |

| All pairs of points are equally distant | Pairwise distances between points become very similar (distance concentration). | Clustering and nearest-neighbor algorithms become ineffective and unstable [24]. |

| Spurious accuracy | A predictive model can achieve near-perfect accuracy on training data by memorizing noise. | Leads to severe overfitting and models that fail to generalize to new data [24]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Selection (FS) Methods for High-Dimensional Data

This table compares several hybrid FS methods discussed in recent literature, highlighting their mechanisms and reported performance [26].

| Method (Acronym) | Full Name & Key Mechanism | Key Advantage | Reported Accuracy (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMGWO | Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization. Uses a two-phase mutation to balance global and local search. | Enhanced exploration/exploitation balance; high accuracy with few features [26]. | 96% (Wisconsin Breast Cancer, SVM classifier) [26]. |

| ISSA | Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm. Incorporates adaptive inertia weights and elite salps. | Improved convergence accuracy through adaptive mechanisms [26]. | Performance comparable to other top methods [26]. |

| BBPSO | Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization. A velocity-free PSO variant for binary feature spaces. | Simplicity and improved computational performance [26]. | Effective discriminative feature selection [26]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Leverage Score Sampling Workflow

Feature Selection Strategy Decision

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| VariantSpark | A scalable Random Forest library built on Apache Spark, designed specifically for high-dimensional genomic data (millions of features) [25]. |

| Hybrid FS Algorithms (TMGWO, ISSA, BBPSO) | Metaheuristic optimization algorithms used to identify the most relevant feature subsets from high-dimensional data [26]. |

| Leverage Score Computations | A linear algebra-based method (often using ridge regularization) to value datapoints by their geometric influence in the feature space [28]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A classic dimension reduction technique that projects data into a lower-dimensional space defined by orthogonal principal components [27]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) Data | The raw input from technologies like Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore, generating the high-dimensional features (e.g., genomic variants, expression counts) that are the subject of analysis [29] [30]. |

The Maximum Relevance Minimum Redundancy Principle in Biomedical Contexts

Core mRMR Concept and Biomedical Workflow

The Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) principle is a feature selection algorithm designed to identify a subset of features that are maximally correlated with a target classification variable (maximum relevance) while being minimally correlated with each other (minimum redundancy) [31]. This method addresses a critical challenge in biomedical data analysis: high-dimensional datasets often contain numerous relevant but redundant features that can impair model performance and interpretability [32].

The fundamental mRMR objective function can be implemented through either:

- Mutual Information Difference (MID): Φ = D - R

- Mutual Information Quotient (MIQ): Φ = D/R

where D represents relevance and R represents redundancy [32]. For continuous features, relevance is typically calculated using the F-statistic, while redundancy is quantified using Pearson correlation. For discrete features, mutual information is used for both measures [32].

The biomedical application workflow follows a systematic process as shown below:

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard mRMR Implementation for Gene Expression Data

Purpose: Identify discriminative genes for disease classification from microarray data [31] [32].

Protocol Steps:

- Data Preparation: Format gene expression data as G×N matrix (G genes, N samples) with associated class labels (e.g., disease/healthy)

- Relevance Calculation: For each gene gⱼ, compute relevance using F-statistic:

- Between-class variance: ∑ₖnₖ(ḡⱼ,(ₖ) - ḡⱼ)²/(K-1)

- Within-class variance: ∑ₖ∑ₗ(gⱼ,𝑙,(ₖ) - ḡⱼ,(ₖ))²/(N-K)

- F(gⱼ,c) = Between-class variance / Within-class variance [32]

- Redundancy Calculation: Compute pairwise Pearson correlation between all genes

- Feature Ranking: Apply incremental search to optimize Φ(D,R) = D - R

- Subset Selection: Select top-k features based on mRMR scores

Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-10 folds) to assess classification accuracy with selected features [33].

Temporal mRMR for Longitudinal Studies

Purpose: Handle multivariate temporal data (e.g., time-series gene expression) without data flattening [32].

Protocol Steps:

- Temporal Relevance: Compute F-statistic at each time point, then aggregate via arithmetic mean: F(gⱼ,c) = (1/T) ∑ₜF(gⱼᵗ,c) [32]

- Temporal Redundancy: Apply Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) to quantify similarity between temporal patterns

- Feature Selection: Use standard mRMR selection with temporal relevance and redundancy measures

Advantage: Preserves temporal information that would be lost in data flattening approaches [32].

mRMR for Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Stress Detection

Purpose: Select optimal HRV features for stress classification [34].

Protocol Steps:

- HRV Feature Extraction: Calculate time-domain, frequency-domain, and non-linear HRV features

- Non-linear Redundancy: Replace Pearson correlation with non-linear dependency measures

- Feature Selection: Apply mRMR with extended redundancy measures

- Classifier Training: Use selected features with SVM or Random Forest classifiers

Performance: Extended mRMR methods demonstrate superior performance for stress detection compared to traditional feature selection [34].

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Results

mRMR Performance Across Biomedical Domains

Table 1: mRMR Performance Metrics in Different Biomedical Applications

| Application Domain | Dataset Characteristics | Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Gene Expression [32] | 3 viral challenge studies, multivariate temporal data | Improved accuracy in 34/54 experiments, others outperformed in ≤4 experiments | Superior to standard flattening approaches |

| Multi-omics Data Integration [33] | 15 cancer datasets from TCGA, various omics types | High AUC with few features, outperformed t-test and reliefF | Computational efficiency with strong predictive performance |

| HRV Stress Classification [34] | 3 public HRV datasets, stress detection | Enhanced classification accuracy with non-linear redundancy | Captures complex feature relationships |

| Lung Cancer Diagnosis [35] | Microarray gene expression data | 92.37% accuracy with hybrid mRMR-RSA approach | Improved feature selection for cancer classification |

| Ransomware Detection in IIoT [36] | API call logs, system behavior | Low false-positive rates, reduced computational complexity | Effective noisy behavior filtering |

mRMR vs. Other Feature Selection Methods

Table 2: Benchmark Comparison of Feature Selection Methods for Multi-omics Data [33]

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Average AUC | Features Selected | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | mRMR | High | Small subset (10-100) | Medium |

| RF-VI (Permutation Importance) | High | Small subset | Low | |

| t-test | Medium | Varies | Low | |

| reliefF | Low (for small nvar) | Varies | Low | |

| Embedded Methods | Lasso | High | ~190 features | Medium |

| Wrapper Methods | Recursive Feature Elimination | Medium | ~4801 features | High |

| Genetic Algorithm | Low | ~2755 features | Very High |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: How should I handle extremely high-dimensional data where mRMR computation becomes infeasible?

Issue: Computational complexity increases exponentially with feature count, making mRMR impractical for datasets with >50,000 features.

Solutions:

- Apply pre-filtering using simple univariate methods (e.g., t-test, variance threshold) to reduce feature space to 1,000-5,000 top features before mRMR [33]

- Implement incremental mRMR that processes features in batches

- Use approximate mutual information estimation methods to reduce computation time

- For genomic data, perform preselection based on biological knowledge (e.g., pathway analysis)

Validation: Compare results with and without pre-filtering to ensure biological relevance is maintained [32].

FAQ 2: What should I do when mRMR selects features with apparently low individual relevance?

Issue: mRMR may select features that have moderate individual relevance but provide unique information not captured by other features.

Solutions:

- This is often correct behavior - mRMR intentionally selects features that provide complementary information

- Verify by examining pairwise correlations between selected features - they should be low

- Check model performance with selected features versus top individually relevant features

- Use domain knowledge to validate biological plausibility of selected feature combinations

Example: In gene expression studies, mRMR might select genes from different pathways that collectively provide better discrimination than top individually relevant genes from the same pathway [32].

FAQ 3: How can I adapt mRMR for temporal or longitudinal biomedical data?

Issue: Standard mRMR requires flattening temporal data, losing important time-dependent information.

Solutions:

- Implement Temporal mRMR (TMRMR) that computes relevance across time points and uses Dynamic Time Warping for redundancy assessment [32]

- Use arithmetic mean aggregation of F-statistics across time points for relevance calculation

- Consider shape-based similarity measures (DTW) rather than point-wise correlations for redundancy

- For irregular time sampling, apply interpolation or Gaussian process regression before feature selection

Performance: TMRMR shows significant improvement over flattened approaches in viral challenge studies [32].

FAQ 4: Why does my mRMR implementation yield different results with the same data?

Issue: Inconsistent results may arise from implementation variations or stochastic components.

Solutions:

- Verify mutual information estimation method - use consistent discretization strategies for continuous data

- Check handling of tied scores in the incremental selection process

- Ensure proper normalization of features before redundancy calculation

- For stochastic implementations, set fixed random seeds and average over multiple runs

- Compare with established implementations (e.g., Peng Lab mRMR) as benchmark

Validation: Use public datasets with known biological ground truth for method validation [33].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for mRMR Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Python mRMR Implementation | Core feature selection algorithm | Use pymrmr package or scikit-learn compatible implementations |

| Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) | Temporal redundancy measurement | dtw-python package for temporal mRMR [32] |

| Mutual Information Estimators | Relevance/redundancy quantification | Non-parametric estimators for continuous data using scikit-learn |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Method validation | 5-10 fold stratified cross-validation for robust performance assessment [33] |

| Bioconductor Packages | Genomics data pre-processing | For microarray and RNA-seq data normalization before mRMR |

| Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT) | Automated model selection | Optimizes classifier choice with mRMR features [37] |

Advanced mRMR Workflow for Multi-Omics Integration

The integration of mRMR with multi-omics data requires specialized workflows to handle diverse data types and structures:

Key Findings: Research indicates that whether features are selected by data type separately or from all data types concurrently does not considerably affect predictive performance, though concurrent selection may require more computation time for some methods [33]. The mRMR method consistently delivers strong predictive performance in multi-omics settings, particularly when considering only a few selected features [33].

Methodological Implementation and Domain-Specific Applications

Algorithmic Frameworks for Leverage Score Sampling in High-Dimensional Spaces

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary benefit of using leverage score sampling in high-dimensional feature selection? Leverage score sampling helps perform approximate computations for large matrices, enabling faithful approximations with a complexity adapted to the problem at hand. In high-dimensional spaces, it mitigates the "curse of dimensionality"—where data points become too distant for algorithms to identify patterns—by effectively reducing the feature space and improving the computational efficiency and generalization of models [26] [38] [39].

Q2: My model is overfitting despite using leverage scores. What could be wrong? Overfitting can persist if the selected features are still redundant or if the sampling process does not adequately capture the data structure. To address this:

- Verify Feature Relevance: Ensure the leverage score algorithm is coupled with a mechanism to handle feature redundancy. Using a multi-objective approach that simultaneously minimizes selected features and classification error can help [40].

- Check Sampling Adequacy: The leverage score sampling method must be both fast and accurate. Inaccurate scores can lead to a suboptimal feature subset. Consider using modern algorithms designed for positive definite matrices defined by a kernel [38].

- Combine with Regularization: Embedded feature selection methods, such as LASSO (L1) regression, can be used alongside sampling to penalize irrelevant features and further reduce overfitting [39].

Q3: How do I choose between filter, wrapper, and embedded methods for feature selection in my leverage score pipeline? The choice depends on your project's balance between computational cost and performance needs. The table below summarizes the core characteristics:

| Method | Core Mechanism | Pros | Cons | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Selects features based on statistical properties (e.g., correlation with target) [39]. | Fast, model-agnostic, efficient for removing irrelevant features and lowering redundancy [41] [39]. | Ignores feature interactions and model performance [39]. | Preprocessing and initial data screening [39]. |

| Wrapper Methods | Uses a specific model to evaluate feature subsets, adding/removing features iteratively [39]. | Considers feature interactions, can lead to high-performing feature sets [39]. | Computationally expensive, risk of overfitting to the model [26] [39]. | Smaller datasets or when computational resources are sufficient [39]. |

| Embedded Methods | Performs feature selection as an integral part of the model training process [39]. | Computationally efficient, considers model performance, less prone to overfitting (e.g., via regularization) [41] [39]. | Tied to a specific learning algorithm [39]. | Most practical applications; balances efficiency and performance [39]. |

For high-dimensional data, a common strategy is to use a hybrid approach, such as a filter method for initial feature reduction followed by a more refined wrapper or embedded method [26] [41].

Q4: What are the latest advanced algorithms for high-dimensional feature selection? Researchers are developing sophisticated hybrid and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms. The following table compares some recent advanced frameworks:

| Algorithm Name | Type | Key Innovation | Reported Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiobjective Differential Evolution [40] | Evolutionary / Embedded | Integrates feature weights & redundancy indices, uses adaptive grid for solution diversity. | Significantly outperforms other multi-objective feature selection approaches [40]. |

| TMGWO (Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization) [26] | Hybrid / Wrapper | Incorporates a two-phase mutation strategy to balance exploration and exploitation. | Achieved superior feature selection and classification accuracy (e.g., 96% on Breast Cancer dataset) [26]. |

| BBPSOACJ (Binary Black PSO) [26] | Hybrid / Wrapper | Uses adaptive chaotic jump strategy to help stalled particles escape local optima. | Better discriminative feature selection and classification performance than prior methods [26]. |

| CHPSODE (Chaotic PSO & Differential Evolution) [26] | Hybrid / Wrapper | Balances exploration and exploitation using chaotic PSO and differential evolution. | A reliable and effective metaheuristic for finding realistic solutions [26]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow or Inefficient Leverage Score Sampling

- Symptoms: The sampling process takes an excessively long time, making the overall pipeline impractical for large datasets.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inefficient leverage score computation for very large kernel matrices.

- Solution: Investigate and implement novel algorithms specifically designed for "Fast Leverage Score Sampling" on positive definite matrices, which claim to be among the most efficient and accurate methods available [38].

- Cause 2: The overall feature selection algorithm lacks focus on computational efficiency.

- Solution: Integrate leverage sampling with modern, efficient frameworks. For instance, hybrid AI-driven feature selection frameworks are designed to reduce training time and model complexity [26]. Using an embedded method like LASSO regression can also streamline the process by performing selection during training [39].

- Cause 1: Inefficient leverage score computation for very large kernel matrices.

Problem: Poor Classification Performance After Feature Selection

- Symptoms: After applying leverage score sampling and feature selection, your model's accuracy, precision, or recall is significantly lower than expected.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: The feature selection process is too aggressive, removing informative features along with redundant ones.

- Solution: Adopt a multi-objective algorithm that explicitly optimizes for both a small feature subset and a low classification error rate. This balances feature reduction with model performance [40].

- Cause 2: The selected features have high redundancy.

- Solution: Use algorithms that incorporate a redundancy index or feature correlation weight matrix. For example, some methods use a Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) to model influence relationships and compute correlation weights between features, proactively filtering redundant features [40].

- Cause 3: The model is not validated with the correct metrics during the selection phase.

- Cause 1: The feature selection process is too aggressive, removing informative features along with redundant ones.

Problem: Algorithm Converges to a Suboptimal Feature Subset

- Symptoms: The feature selection algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum, consistently returning the same, non-ideal set of features.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Lack of diversity in the search process of population-based algorithms (e.g., PSO, DE).

- Solution: Implement an adaptive grid mechanism in the objective space. This identifies densely populated regions of solutions and refines them by replacing redundant features, thereby maintaining diversity and preventing premature convergence [40].

- Cause 2: Poor initialization of the feature population.

- Solution: Utilize a sophisticated initialization strategy that divides the population into subpopulations based on feature importance and redundancy. This enhances initial diversity and uniformity, setting a better foundation for the search [40].

- Cause 1: Lack of diversity in the search process of population-based algorithms (e.g., PSO, DE).

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

1. Protocol for Benchmarking Feature Selection Algorithms

This protocol outlines how to compare the performance of different feature selection methods, including those using leverage score sampling.

- Objective: To evaluate and compare the performance of various feature selection algorithms on standardized datasets using multiple metrics.

- Datasets: Utilize publicly available benchmark datasets with varying difficulty and dimensionality (e.g., from the UCI Machine Learning Repository). Common examples include Wisconsin Breast Cancer, Sonar, and Diffused Thyroid Cancer datasets [26] [40].

- Algorithms to Compare:

- Your Leverage Score-Based Method

- Baselines: Standard Filter (e.g., Pearson's Correlation), Wrapper (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination), and Embedded (e.g., Random Forest Importance) methods [39].

- State-of-the-Art: Recent advanced algorithms like TMGWO, BBPSO, or Multiobjective Differential Evolution [26] [40].

- Evaluation Metrics: Track the following for each algorithm:

- Classification Accuracy/Error Rate

- Precision and Recall

- Number of Selected Features

- Computational Time

- Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Clean data, handle missing values, and normalize features.

- Feature Selection: Apply each algorithm to the training set only to avoid data leakage.

- Model Training & Validation: Train a chosen classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on the selected features using k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 10-fold) [26].

- Testing: Evaluate the final model on a held-out test set.

- Analysis: Compare the results of all algorithms across the collected metrics.

2. Workflow for a Hybrid AI-Driven Feature Selection Framework

This workflow describes the high-level steps used in modern, high-performing frameworks as cited in the literature [26].

Hybrid Feature Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in developing and testing algorithms for leverage score sampling and feature selection.

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-Learn (Sklearn) | A core Python library providing implementations for filter methods (e.g., Pearson's correlation, Chi-square), wrapper methods (e.g., RFE), and embedded methods (e.g., LASSO) [39]. | Used for building baseline models, preprocessing data, and accessing standard feature selection tools. |

| UCI Machine Learning Repository | A collection of databases, domain theories, and data generators widely used in machine learning research for empirical analysis of algorithms [26] [40]. | Serves as the source of standardized benchmark datasets (e.g., Wisconsin Breast Cancer) to ensure fair comparison. |

| Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) | A technique to balance imbalanced datasets by generating synthetic samples for the minority class [26]. | Applied during data preprocessing before feature selection to prevent bias against minority classes. |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation | A resampling procedure used to evaluate models by partitioning the data into 'k' subsets, using k-1 for training and 1 for validation, and repeating the process k times [26]. | Crucial for reliably estimating the performance of a model trained on a selected feature subset without overfitting. |

| Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) | A class of algorithms that optimize for multiple conflicting objectives simultaneously, such as minimizing feature count and classification error [40]. | Forms the backbone of advanced feature selection frameworks like Multiobjective Differential Evolution [40]. |

| Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) | A methodology for modeling complex systems and computing correlation weights between features and the target label [40]. | Used within a feature selection algorithm to intelligently assess feature importance and inter-feature relationships [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary motivation for combining leverage scores with mutual information and correlation filters?

Combining these techniques aims to create a more robust feature selection pipeline for high-dimensional biological data. Leverage scores help identify influential data points, mutual information effectively captures non-linear relationships between features and the target, and correlation filters eliminate redundant linear relationships. This multi-stage approach mitigates the limitations of any single method, enhancing the stability and performance of models used in critical applications like drug discovery [42].

Q2: During implementation, I encounter high computational costs. How can this be optimized?

The two-stage framework inherently addresses this. The first stage uses fast, model-agnostic filter methods (like mutual information and correlation) for a preliminary feature reduction. This drastically reduces the dimensionality of the data before applying more computationally intensive techniques, thus lowering the overall time complexity for the subsequent search for an optimal feature subset [42].

Q3: My final model is overfitting, despite using feature selection. What might be going wrong?

Overfitting can occur if the feature selection process itself is too tightly tuned to a specific model or dataset. To mitigate this:

- Ensure you are using cross-validation during the feature selection process, not just during model training [43].

- Avoid over-optimizing the number of features to select based on a single performance metric. Consider stability analysis.

- Leverage embedded methods like LASSO or tree-based importance that include regularization to penalize complexity [18] [5].

Q4: How do I handle highly correlated features that all seem important?

Correlation filters and mutual information can identify these redundant features. The standard practice is to:

- Calculate the correlation matrix or mutual information between features.

- Identify groups of highly correlated features.

- Within each group, retain the feature with the highest correlation or mutual information with the target variable and discard the others to reduce multicollinearity without significant information loss [18] [44].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Feature Selection Results Across Different Datasets

- Symptoms: The selected feature subset varies greatly when the model is applied to different data splits or similar datasets.

- Possible Causes: The initial filter method may be unstable or sensitive to outliers in high-dimensional space.

- Solutions:

- Implement a Robust First Stage: Use ensemble-based methods like Random Forest for initial feature elimination. The variable importance measures from Random Forest are more stable due to the inherent randomness and use of multiple decision trees, making them less susceptible to outliers [42].

- Apply Stability Selection: Run the entire feature selection pipeline multiple times with different data subsamples and select features that are consistently chosen across runs.

Problem: Poor Model Performance Despite High Scores from Filter Methods

- Symptoms: Features score highly on individual statistical tests (e.g., high mutual information), but the final model's predictive accuracy is low.

- Possible Causes: Filter methods evaluate features independently and may miss complex interactions between features that are informative to the model when combined [5] [43].

- Solutions: