Optimizing Motion Censoring Thresholds for Volumetric Analysis: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Motion artifacts present a significant challenge to the validity of volumetric analysis in neuroimaging and drug development.

Optimizing Motion Censoring Thresholds for Volumetric Analysis: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Motion artifacts present a significant challenge to the validity of volumetric analysis in neuroimaging and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on implementing and optimizing motion censoring thresholds. Drawing on recent 2025 studies, we explore the foundational principles of motion censoring, detail methodological approaches for application across diverse populations (from fetuses to adults), address key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present validation frameworks for comparing techniques. The synthesis of current evidence underscores that combining nuisance regression with strategic volume censoring significantly mitigates motion-related bias, enhances prediction accuracy for neurobiological features, and improves the reliability of brain-behavior associations, thereby strengthening the conclusions of preclinical and clinical studies.

Understanding Motion Censoring: Why It's Foundational for Reliable Volumetric Data

The Critical Impact of Motion Artifacts on Functional Connectivity and Volumetric Measures

Functional connectivity (FC), typically measured as the temporal correlation between blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) time series from different brain regions, provides crucial insights into the brain's intrinsic functional organization [1]. However, FC is a statistical construct rather than a direct physical measurement, making it highly susceptible to contamination by various noise sources, with head motion representing one of the most significant and pervasive confounds [2] [3]. Motion artifacts can introduce systematic biases in FC estimates, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions in both basic research and clinical applications, including drug development studies where accurate biomarkers are essential [2] [4]. Even small movements can cause spurious correlations or anti-correlations between brain regions that do not reflect true neural synchronization [3]. In volumetric analysis, motion can distort anatomical measurements and compromise the accuracy of cross-sectional and longitudinal study designs. This application note examines the impact of motion on functional connectivity and volumetric measures, provides evidence-based protocols for mitigation, and offers practical solutions for researchers aiming to improve data quality in neuroimaging studies.

The Impact of Motion on Functional Connectivity Metrics

Empirical Evidence of Motion Artifacts

Head motion systematically alters multiple properties of functional connectivity networks, affecting both individual-level analyses and group comparisons. Recent evidence demonstrates that motion reduces the temporal Signal-to-Noise Ratio (tSNR) of resting-state fMRI data, with one study reporting 45% reductions in tSNR during large head movements compared to stationary conditions [5]. This reduction in data quality directly impacts the spatial definition of major resting-state networks (RSNs), including the default mode, visual, and central executive networks, which appear less defined in data affected by motion [5].

Perhaps more critically, motion introduces artifactual correlations between head movement and FC measures that persist even after applying standard nuisance regression techniques. In fetal imaging, where motion is particularly challenging to control, FC profiles significantly predicted average framewise displacement (FD) even after nuisance regression (r = 0.09 ± 0.08; p < 10-3), indicating lingering motion effects on whole-brain connectivity patterns [2]. This confounding relationship is particularly problematic for case-control studies, where groups may systematically differ in their motion characteristics, potentially introducing spurious group differences [2] [4].

Differential Impact Across Functional Connectivity Methods

The susceptibility of FC measures to motion artifacts varies considerably depending on the choice of pairwise interaction statistic used to compute connectivity. A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluating 239 different pairwise statistics revealed substantial variation in how motion affects different FC metrics [1]. While conventional Pearson's correlation (a covariance-based statistic) remains widely used, other approaches demonstrate different sensitivity profiles to motion artifacts:

- Precision-based statistics (e.g., partial correlation) show strong correspondence with structural connectivity and may be less susceptible to certain motion-related confounds [1]

- Distance-based measures, which quantify dissimilarity between time series, exhibit different artifact propagation patterns compared to correlation-based methods [1]

- Spectral and information-theoretic measures capture distinct aspects of functional coupling, with varying sensitivity to motion-induced signal changes [1]

This differential sensitivity highlights the importance of selecting FC metrics that are robust to motion artifacts for specific research applications, particularly in populations prone to higher motion.

Motion Mitigation Strategies and Censoring Thresholds

Volume Censoring (Scrubbing)

Volume censoring, or "scrubbing," involves identifying and removing individual volumes affected by excessive motion from fMRI time series analysis. This technique has proven highly effective across diverse populations, from fetuses to adults [2] [6]. The implementation requires calculating framewise displacement (FD) for each volume, which quantifies head movement between consecutive time points.

Table 1: Comparison of Censoring Thresholds Across Populations

| Population | Recommended FD Threshold | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetuses | 1.5 mm | Improved prediction of neurobiological features (GA, sex); accuracy: 55.2 ± 2.9% with censoring vs. 44.6 ± 3.6% without | [2] |

| First-grade children | 0.3 mm | Retained 83% of participants while meeting rigorous quality standards; effective when combined with ICA denoising | [6] |

| Multi-site adult studies | 0.2-0.4 mm | Commonly used thresholds; balance between data quality and retention of volumes | [3] |

The selection of an appropriate censoring threshold involves balancing data quality with the retention of sufficient temporal data for reliable FC estimation. Overly stringent thresholds may exclude excessive data, while lenient thresholds permit motion artifacts to contaminate results.

Integrated Denoising Pipelines

No single denoising method universally excels across all datasets and research questions [7]. Instead, integrated pipelines combining multiple approaches demonstrate superior efficacy:

- Nuisance regression of motion parameters (typically 6-24 regressors including derivatives and squares) [2]

- Volume censoring at population-appropriate FD thresholds [2] [6]

- ICA-based denoising (e.g., ICA-FIX) to remove motion-related components [7] [6]

- Global Signal Regression (GSR) remains controversial but can reduce motion-related artifacts [7]

- Physiological noise correction using RETROICOR for cardiac and respiratory signals [8]

Pipelines combining ICA-FIX and GSR appear to offer a reasonable trade-off between motion reduction and behavioral prediction performance across multiple datasets [7]. For multi-echo fMRI data, RETROICOR effectively reduces physiological noise, with both individual-echo and composite approaches showing similar efficacy [8].

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC)

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) utilizes real-time head tracking to update imaging sequences during acquisition, fundamentally addressing motion at the source rather than through post-processing. PMC has been shown to:

- Increase tSNR by 20% during intentional large head movements compared to uncorrected acquisitions [5]

- Improve the spatial definition of major RSNs affected by motion [5]

- Generate temporal correlation matrices under motion conditions more comparable to those obtained during stationary acquisitions [5]

This approach is particularly valuable in populations where substantial motion is unavoidable, such as pediatric patients or certain clinical populations.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Mitigation

Protocol 1: Volume Censoring with Integrated Denoising

Table 2: Step-by-Step Volume Censoring Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Motion Parameter Calculation | Extract 6 rigid-body motion parameters (3 translation, 3 rotation) from realignment. Convert rotational parameters from radians to millimeters using head radius approximation. | Implement with FSL MCFLIRT, AFNI 3dvolreg, or Bioimage Suite (fetal-specific) [2] [3] |

| 2. Framewise Displacement (FD) Computation | Compute FD as the sum of absolute values of differentiated motion parameters. | FD = |ΔX| + |ΔY| + |ΔZ| + |Δpitch| + |Δyaw| + |Δroll| [2] |

| 3. Threshold Determination | Select appropriate FD threshold based on population and research goals. | Common thresholds: 0.2-0.4mm (adults), 0.3mm (children), 1.5mm (fetuses) [2] [6] [3] |

| 4. Censoring Implementation | Flag volumes exceeding FD threshold, plus one preceding volume. | Implement using AFNI 3dTproject, fslmotionoutliers, or custom scripts [3] |

| 5. Nuisance Regression | Regress out motion parameters, tissue signals, and other confounds from non-censored volumes. | Include 24-36 motion regressors (Volterra expansion), WM/CSF signals, derivatives [2] |

| 6. Complementary Denoising | Apply ICA-based denoising (ICA-FIX) to remove residual motion artifacts. | Particularly effective in high-motion pediatric populations [6] |

Protocol 2: Multi-Echo fMRI with Physiological Noise Correction

For researchers utilizing multi-echo fMRI sequences, the following protocol enhances motion robustness:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire multi-echo fMRI data with 3+ echo times (e.g., TE = 17.00, 34.64, 52.28 ms) [8]

- Physiological Monitoring: Record cardiac and respiratory signals simultaneously with fMRI acquisition

- RETROICOR Application: Apply RETROICOR to model and remove physiological noise - either to individual echoes before combination or to composite data after combination [8]

- Echo Combination: Optimally combine echoes using T2* weighting

- Quality Assessment: Verify improvement using tSNR, signal fluctuation sensitivity (SFS), and variance of residuals [8]

This approach demonstrates particular benefit in moderately accelerated acquisitions (multiband factors 4-6) with optimized flip angles (45°) [8].

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Motion Correction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools / Methods | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Motion Estimation | FSL MCFLIRT, AFNI 3dvolreg, Bioimage Suite fetalmotioncorrection | Calculate rigid-body head motion parameters from fMRI time series [2] [3] |

| Quality Metrics | Framewise Displacement (FD), DVARS, tSNR | Quantify data quality and identify motion-corrupted volumes [2] [3] |

| Censoring Tools | AFNI 3dTproject, fslmotionoutliers | Implement volume censoring based on motion thresholds [2] [3] |

| Denoising Algorithms | ICA-AROMA, FIX, RETROICOR | Remove motion and physiological artifacts using data-driven approaches [7] [8] |

| Prospective Correction | MR-compatible optical tracking (PMC) | Real-time motion correction during image acquisition [5] |

| Physiological Monitoring | Pulse oximeter, respiratory belt | Record cardiac and respiratory signals for noise modeling [8] |

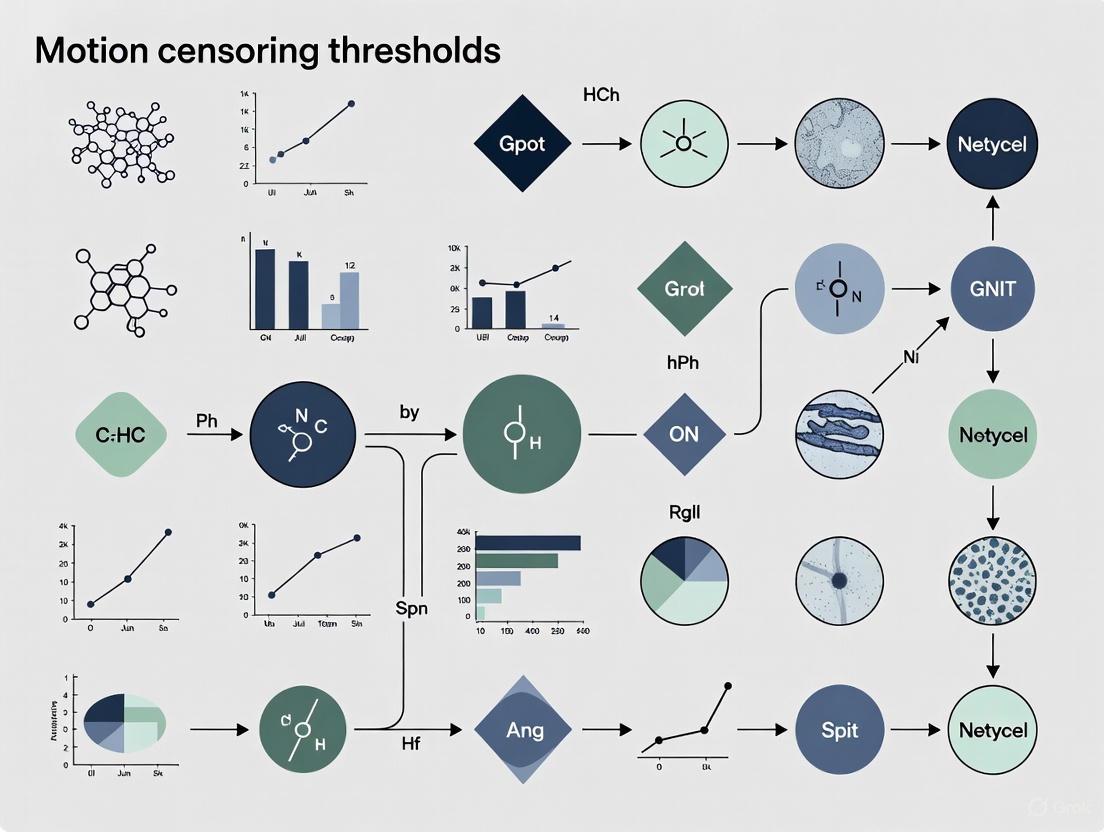

Workflow Visualization

Motion artifacts represent a critical challenge in functional connectivity research, with demonstrated effects on data quality, network identification, and brain-behavior correlations. Effective mitigation requires integrated approaches combining prospective correction when feasible, rigorous volume censoring at appropriate thresholds, and complementary denoising methods. The optimal motion correction strategy depends on the specific population, acquisition parameters, and research questions. For volumetric analysis in thesis research and drug development studies, implementing standardized motion mitigation protocols is essential for generating reliable, reproducible results. Future directions include refining population-specific censoring thresholds, developing more robust FC metrics less susceptible to motion artifacts, and integrating real-time quality control measures into acquisition protocols.

Subject motion remains a significant challenge in neuroimaging, particularly in studies requiring high data fidelity for volumetric and functional connectivity analysis. While nuisance regression of motion parameters has been widely adopted as a standard motion correction technique, evidence demonstrates that this approach alone is insufficient for fully mitigating motion-induced artifacts. This Application Note delineates the inherent limitations of basic nuisance regression and establishes the imperative for incorporating volume censoring (also known as "scrubbing") as an essential supplementary step in preprocessing pipelines for both functional and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The recommendations are framed within the context of establishing motion censoring thresholds for volumetric analysis research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with validated protocols to enhance data quality and analytical robustness.

The Fundamental Limitations of Nuisance Regression

Theoretical Shortcomings

Nuisance regression operates by including motion parameters (typically three translational and three rotational, plus their derivatives) as regressors in a general linear model to remove variance associated with head movement from the blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signal. While this technique effectively reduces some motion-related variance, it possesses critical theoretical limitations:

- Incomplete Signal Capture: Nuisance regression assumes a linear relationship between head displacement and BOLD signal changes, yet motion artifacts often manifest through non-linear mechanisms including spin history effects, magnetic field inhomogeneity changes, and interpolation errors during realignment.

- Residual Motion-FC Coupling: Even after aggressive nuisance regression, systematic correlations between head motion and functional connectivity (FC) patterns persist, potentially introducing spurious neurobiological findings [2].

Empirical Evidence of Inefficacy

Recent empirical investigations consistently demonstrate the inadequacy of nuisance regression as a standalone motion correction strategy.

Table 1: Documented Limitations of Nuisance Regression Across Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Documented Effect | Statistical Evidence | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-state fMRI (Fetal) | Persistent association between FC and motion after regression | FC profiles significantly predicted average FD (r = 0.09 ± 0.08; p < 10-3) | [2] |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging | Changes in fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) with motion | Significant decrease in mean FA (P<0.01) and increase in MD (P<0.01) after retrospective correction | [9] |

| Resting-state fMRI (Adult) | Motion-induced functional connectivity changes | Inflated correlation strengths from correlated non-neuronal signals | [3] |

In fetal resting-state fMRI, a particularly challenging motion environment, nuisance regression alone failed to decouple head motion from functional connectivity patterns. The lingering effects were so pronounced that functional connectivity profiles could significantly predict the extent of head motion even after regression, indicating that motion-related variance continued to systematically influence the final analytical outcomes [2]. Similarly, in diffusion tensor imaging, motion induces significant microstructural metric biases that persist after standard correction, potentially confounding group differences in clinical drug trials [9].

Volume Censoring: An Essential Supplement

Theoretical Foundation and Mechanisms

Volume censoring addresses the fundamental limitation of nuisance regression by temporally isolating motion-corrupted data points rather than attempting to statistically model their effects. The technique identifies volumes with excessive motion based on frame-wise displacement (FD) metrics and excludes them from subsequent analysis, preventing disproportionately influential artifacts from contaminating the entire dataset.

The mathematical foundation for censoring relies on calculating the Euclidean norm of motion parameters (enorm). For each time point, the enorm represents the square root of the sum of squares of the differential motion parameters between successive scans. When this value exceeds a predetermined threshold, both the current and preceding time points are typically censored to account for spin history effects [10].

Efficacy and Validation Evidence

The supplementary benefit of volume censoring has been empirically validated across multiple populations and imaging contexts.

Table 2: Efficacy of Volume Censoring for Enhancing Data Quality

| Population | Censoring Benefit | Quantitative Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal | Enhanced neurobiological feature prediction | Gestational age/sex prediction accuracy: 55.2 ± 2.9% (with censoring) vs. 44.6 ± 3.6% (without) | [2] |

| Fetal | Reduction of motion-FC coupling | Significant attenuation of association between FD and whole-brain FC patterns | [2] |

| Adult | Mitigation of motion-induced connectivity artifacts | Reduction of erroneously inflated correlation strengths between regions | [3] |

In fetal imaging, incorporating volume censoring at an optimal threshold substantially improved the capacity to predict neurobiological features such as gestational age and biological sex from resting-state data. This enhancement demonstrates that censoring not only reduces noise but also improves the signal-to-noise ratio for biologically relevant features, a critical consideration for longitudinal drug development studies tracking developmental changes or treatment effects [2].

Quantitative Evidence and Threshold Determination

Comparative Performance of Censoring Thresholds

Determining appropriate censoring thresholds is paramount for optimizing the balance between data retention and artifact removal. Systematic evaluation of different FD thresholds provides evidence-based guidance for threshold selection.

Table 3: Impact of Motion Censoring Thresholds on Data Quality

| Censoring Threshold | Effect on Data Quality | Recommended Context | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 mm | Most aggressive censoring; maximal artifact removal | Studies requiring highest data purity; stable populations | [3] |

| 0.3 mm | Standard threshold balancing quality and data retention | General adult population studies | [10] |

| 0.4 mm | Less aggressive censoring; greater data retention | Pediatric or clinical populations with expected motion | [3] |

| 1.0 mm | Minimal censoring; substantial artifact retention | Preliminary analyses or data quality assessment | [3] |

| 1.5 mm | Optimal threshold for fetal rs-fMRI | Fetal imaging; challenging motion environments | [2] |

The selection of an appropriate censoring threshold involves careful consideration of research objectives, subject population, and analytical sensitivity. For standard adult populations, a threshold of 0.3 mm provides an effective balance, while more lenient thresholds (e.g., 0.4 mm) may be appropriate for pediatric or clinical populations where data retention is prioritized [3]. In exceptionally challenging environments such as fetal imaging, higher thresholds (e.g., 1.5 mm) have demonstrated optimal performance for preserving neurobiological signal while mitigating motion artifacts [2].

Integration with Outlier Detection

Beyond frame-wise displacement metrics, complementary outlier detection strengthens motion censoring protocols. The fraction of outliers per volume provides an additional criterion for identifying corrupted time points that may not be captured by motion parameters alone. A typical threshold censors volumes where more than 5-10% of voxels are classified as outliers, though this should be adjusted for studies with limited field-of-view [10].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Comprehensive Motion Correction Protocol for Resting-State fMRI

This integrated protocol combines nuisance regression with volume censoring for optimal motion correction in resting-state fMRI studies.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- AFNI processing environment (3dVolReg, 3dTproject) [3]

- T1-weighted structural images

- T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) resting-state data

- Template space (e.g., ICBM 152 non-linear atlas)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing

- Remove initial 4 volumes to ensure magnetization steady-state

- Apply slice-timing correction (3dTshift)

- Perform rigid-body realignment to first volume (3dVolReg)

Motion Parameter Calculation

- Extract 6 rigid-body motion parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations)

- Compute frame-wise displacement (FD) as the Euclidean norm of differential motion parameters

- Identify outlier fractions using 3dToutcount

Integrated Nuisance Regression

- Regress out the following nuisance covariates:

- 6 motion parameters and their derivatives (12 regressors)

- Average signals from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

- Global mean signal (context-dependent)

- Temporal derivatives of physiological signals

- Include band-pass filtering (typically 0.01-0.1 Hz) within regression model

- Regress out the following nuisance covariates:

Volume Censoring Implementation

- Apply predetermined FD threshold (default: 0.3 mm)

- Censor both time points where FD exceeds threshold AND preceding time point

- Apply additional censoring based on outlier fraction (typical threshold: 5%)

- Document proportion of censored volumes for quality control

Quality Control Assessment

- Visual inspection of preprocessed data and censoring locations

- Quantify temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR)

- Verify functional connectivity patterns in known networks

- Exclude datasets with excessive censoring (>30-50% volumes, study-dependent)

Protocol for Diffusion Tensor Imaging with Prospective Motion Correction

For DTI studies, where motion effects are particularly detrimental to microstructural metrics, incorporating prospective motion correction with volumetric navigators provides enhanced protection.

Materials:

- MRI system with volumetric navigator capability

- Diffusion-weighted sequence with integrated navigators

- Phantom for validation (initial setup)

Procedure:

- Sequence Implementation

- Integrate 3D-EPI navigators with contrast independent of b-value

- Set motion thresholds for prospective reacquisition

Data Acquisition

- Acquire volumetric navigators frequently throughout scan

- Update slice position and orientation in real-time based on motion tracking

- Trigger volume reacquisition if motion exceeds preset thresholds

Post-Processing

- Apply retrospective motion correction to residual motion effects

- Perform eddy-current correction

- Calculate diffusion tensors and derived metrics (FA, MD)

Validation

- Compare histogram distributions of FA and MD values with and without prospective correction

- Verify recovery of motion-induced shifts in anisotropy metrics [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for Implementation of Advanced Motion Correction

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFNI 3dTproject | Nuisance regression with integrated censoring | Resting-state fMRI processing | https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/ |

| AFNI 3dVolReg | Head motion parameter estimation | Motion quantification across modalities | https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/ |

| BioImage Suite | Fetal motion correction | Specialized processing for fetal fMRI | https://bioimagesuite.github.io/ |

| FSL FDT | Diffusion tensor processing | DTI analysis with eddy-current correction | https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/ |

| XPACE Software Library | Prospective motion correction | Real-time motion compensation during acquisition | [11] |

| Volumetric Navigators | Prospective motion correction in DTI | Real-time motion detection and correction | [9] |

The limitations of nuisance regression as a standalone motion correction strategy are both theoretical and empirically demonstrated. Volume censoring represents an essential supplementary technique that directly addresses the persistent coupling between head motion and functional connectivity patterns that survives conventional regression approaches. Implementation of integrated protocols combining both methods, with appropriate threshold determination specific to research populations and questions, significantly enhances the validity and biological specificity of neuroimaging findings. For researchers in both academic and drug development contexts, adopting these advanced motion correction strategies is imperative for ensuring the reliability of volumetric and functional connectivity analyses in studies investigating therapeutic effects or biomarker discovery.

Head motion remains a significant impediment to high-quality functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) analysis, particularly in resting-state functional connectivity (rs-fMRI) studies. Motion-induced artifacts systematically alter correlations in fMRI data, creating spurious but structured patterns that can compromise research validity [12] [13]. These artifacts are especially problematic when studying pediatric, clinical, or elderly populations who may move more frequently during scanning [14] [12]. Volume censoring has emerged as a powerful retrospective correction technique to mitigate these effects by identifying and statistically excluding motion-contaminated volumes from analysis [14] [15]. This approach, when combined with appropriate preprocessing, enables researchers to retain valuable datasets that would otherwise be excluded due to motion, thereby preventing gaps in our understanding of neurodevelopment and clinical populations [14].

Defining Framewise Displacement (FD)

Calculation and Metric Definition

Framewise Displacement (FD) is a scalar quantity that quantifies volume-to-volume head movement by summarizing the six realignment parameters (RPs) derived from image registration [12] [16]. The standard FD formula, as defined by Power et al. (2012), calculates the sum of absolute values of the derivatives of these RPs [16]:

FD Formula:

FD = |Δxᵢ| + |Δyᵢ| + |Δzᵢ| + |Δαᵢ| + |Δβᵢ| + |Δγᵢ|

Where:

Δxᵢ, Δyᵢ, Δzᵢrepresent translational changes (in mm)Δαᵢ, Δβᵢ, Δγᵢrepresent rotational changes- Index

idenotes the timepoint [16]

Rotational parameters are typically converted from degrees to millimeters by calculating displacement on the surface of a sphere with a specified radius, often 50 mm or the radius of an average brain [17] [16]. This conversion allows consistent units across translational and rotational components.

Practical Implementation

In practice, FD is computed from an N×6 matrix of realignment parameters, where N represents the number of timepoints (volumes) and the six columns correspond to the three translational and three rotational parameters [16]. Multiple software packages (e.g., CONN, AFNI, FSL, fMRIscrub in R) provide implementations for calculating FD, though researchers should note that subtle differences in implementation (such as the radius used for rotational conversion) exist across platforms [17] [16]. Transparent reporting of the exact FD calculation method is essential for reproducibility and cross-study comparisons [17].

Volume Censoring (Scrubbing) Principles

Conceptual Foundation

Volume censoring, often called "scrubbing," is a motion correction strategy that identifies and excludes individual volumes (frames) contaminated by excessive head motion [15] [18]. Unlike continuous nuisance regression approaches, censoring discretely removes the influence of high-motion volumes from statistical analyses [15]. This technique is particularly valuable because motion-induced signal changes are often complex, variable waveforms that can persist for more than 10 seconds after visible movement ceases [13]. These signal changes are frequently shared across nearly all brain voxels and may not be adequately removed by standard regression techniques alone [13].

The theoretical rationale for censoring stems from the observation that motion artifacts have differential impacts depending on their timing and magnitude. Even subjects with similar summary motion statistics can exhibit qualitatively different artifact patterns depending on whether motion was sudden and infrequent versus continuous and moderate [12]. Censoring specifically targets volumes acquired during and immediately after movements, when spin history effects and magnetic gradient disruptions most severely compromise BOLD signal integrity [12] [13].

Integration with Analysis Pipelines

Volume censoring can be implemented through several technical approaches. A common method uses "scan-nulling regressors" or "one-hot encoding" within the General Linear Model (GLM) framework, where each censored volume receives a dedicated dummy regressor, effectively removing its influence on parameter estimates [15]. Alternatively, some pipelines physically remove contaminated volumes before analysis, though this approach requires careful handling of temporal dependencies [14]. When censoring is applied, additional processing steps such as temporal filtering must be adjusted accordingly, as standard filtering approaches would be invalidated by the discontinuities introduced by censoring [14].

Quantitative Thresholds for Volume Censoring

FD Threshold Recommendations

Selection of an appropriate FD censoring threshold represents a critical balance between removing motion artifacts and retaining sufficient data for analysis. Research supports different thresholds depending on the population and research context.

Table 1: Recommended FD Censoring Thresholds Across Populations

| Population | Recommended FD Threshold | Retention Rate | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-grade children (age 6-8) | 0.3 mm | 83% of participants | Combined with ICA denoising; enabled rigorous quality standards [14] |

| General adult populations | 0.2-0.5 mm | Varies by motion | 0.5 mm shows marked correlation changes; significant changes begin at 0.15-0.2 mm [13] |

| Fetal populations | 1.5 mm | N/A | Improved neurobiological feature prediction (e.g., gestational age, sex) [2] |

| Multi-dataset evaluation | Multiple thresholds (e.g., 0.2, 0.4, 1.0 mm) | Dependent on threshold stringency | Modest data loss (1-2%) often provides benefits comparable to other techniques [15] [3] |

Threshold Selection Considerations

The optimal censoring threshold depends on multiple factors, including research objectives, participant population, and acquisition parameters. Stricter thresholds (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) remove more motion-related artifact but result in greater data loss, potentially excluding more participants from analysis [18] [3]. For studies specifically targeting high-motion populations, such as young children or clinical groups, slightly more lenient thresholds (e.g., FD < 0.3-0.4 mm) may be preferable to maintain statistical power while still effectively controlling motion effects [14]. Evaluation of multiple thresholds is recommended to determine the optimal balance for a specific dataset [3].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol for FD Calculation and Volume Censoring

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Realignment

- Acquire T1-weighted structural and BOLD functional images using standard sequences [14] [3]

- Perform rigid body realignment of functional images to correct for head motion [12] [3]

- Extract six realignment parameters (3 translational, 3 rotational) for each volume [16]

Step 2: FD Calculation

- Compute volume-to-volume differences for each realignment parameter [16]

- Convert rotational parameters from degrees to millimeters using a spherical model with appropriate radius (typically 50 mm) [17] [16]

- Sum absolute values of all six differential parameters to obtain FD for each volume [16]

- Export FD values for quality assessment and censoring decisions [19]

Step 3: Censoring Threshold Application

- Select appropriate FD threshold based on population and research goals (refer to Table 1) [14] [2] [13]

- Identify volumes exceeding threshold for censoring [15]

- Optionally, also censor one volume before and after high-motion volumes to account for spin history effects [3] [13]

Step 4: Integration with Analysis Pipeline

- Implement censoring using nuisance regressors in GLM (one regressor per censored volume) [15]

- Alternatively, remove censored volumes before analysis with appropriate adjustment of temporal structure [14]

- Adjust subsequent processing steps (e.g., avoid temporal filtering after censoring) [14]

- Combine with complementary denoising approaches such as ICA-based cleanup [14] [18]

Step 5: Quality Control and Validation

- Calculate data retention rates and exclude subjects with insufficient remaining data [14]

- Verify efficacy by examining correlations between head motion and functional connectivity metrics [14] [18]

- Ensure minimal relationship between motion and outcome measures after censoring [14] [13]

Validation Methodologies

Robust validation of censoring efficacy involves multiple quality control benchmarks. Primary validation metrics include: (1) examining residual relationships between head motion and functional connectivity after denoising; (2) assessing distance-dependent effects of motion on connectivity; (3) evaluating test-retest reliability of connectivity estimates; and (4) analyzing group differences between high- and low-motion subjects [18]. Successful implementation should substantially reduce or eliminate correlations between subject motion and functional connectivity measures, particularly for long-distance connections [14] [12] [13]. Additional validation can demonstrate improved prediction of neurobiological features (e.g., gestational age, sex) when appropriate censoring is applied [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Analytical Tools for FD Calculation and Volume Censoring

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIscrub (R package) | FD calculation and censoring | Direct FD computation from realignment parameters; includes outlier detection [16] |

| AFNI | Comprehensive preprocessing | Includes 3dTproject for censoring; afni_proc.py provides automated pipelines [3] [19] |

| FSL | Image registration and realignment | MCFLIRT for motion correction; can extract realignment parameters for FD calculation [19] |

| CONN | Functional connectivity toolbox | Implements FD calculation using bounding box approach; integrates with SPM [17] |

| ICA-AROMA | Automatic ICA-based denoising | Alternative or complementary approach to censoring; effective for motion removal [18] |

| Bramila Tools | MATLAB-based utilities | Includes bramila_framewiseDisplacement for FD calculation [19] |

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Volume Censoring Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process for calculating Framewise Displacement (FD) and implementing volume censoring in fMRI preprocessing pipelines.

Frame-wise Displacement and volume censoring constitute essential components of modern fMRI processing pipelines, particularly for studies involving populations prone to in-scanner movement. The systematic application of empirically validated FD thresholds enables researchers to mitigate motion-induced artifacts while maximizing data retention. Implementation requires careful consideration of population-specific factors and integration with complementary denoising approaches. When appropriately applied, these methods enhance the validity and reproducibility of functional connectivity findings across diverse research contexts, from developmental neuroscience to clinical neuroimaging studies.

Application Note: The Impact and Mitigation of Motion in Volumetric Analysis

In volumetric analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), "motion" encompasses a broad spectrum of artifacts, from high-amplitude, easily detectable head movements to subtle, systematic biases that persist in data even after standard correction procedures. In resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), these motion artifacts can significantly corrupt the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) time series and distort estimates of functional connectivity (FC), ultimately leading to biased scientific conclusions [20] [2] [3]. This application note details the effects of motion and provides a validated protocol for mitigating its impact through volume censoring, a technique critical for ensuring the reliability of volumetric analysis in research, particularly in challenging populations like fetuses and young children.

Quantitative Evidence: The Necessity of Censoring

The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies on the effects of motion and the efficacy of volume censoring in fetal rs-fMRI.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Motion Effects and Censoring Efficacy in Fetal rs-fMRI

| Metric | Finding without/with Censoring | Interpretation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion-FC Association | FC profiles predicted avg. FD (r = 0.09 ± 0.08; p < 10⁻³) after nuisance regression alone. | Nuisance regression is insufficient to remove motion's lingering effects on whole-brain functional connectivity patterns. | [20] |

| Neurobiological Prediction Accuracy | Gestational Age & Sex Prediction:44.6 ± 3.6% (No Censoring) vs. 55.2 ± 2.9% (1.5 mm FD threshold). | Censoring improves the signal-to-noise ratio, enhancing the data's ability to reveal true neurobiological features. | [20] [2] |

| Recommended Censoring Threshold | 1.5 mm Frame-wise Displacement (FD) for fetal data. | An optimal threshold for this population, balancing noise removal and data retention. | [2] |

| Comparative Threshold (Children) | 0.3 mm FD for first-grade children. | Highlights that censoring thresholds must be tailored to the specific population and their characteristic motion. | [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Volume Censoring for Fetal rs-fMRI

This protocol is adapted from Kim et al. (2025) and is designed to be integrated into a standard fetal rs-fMRI preprocessing pipeline [20] [2].

I. Materials and Data Acquisition

- Subjects: 120 fetal rs-fMRI scans from 104 healthy fetuses (structurally normal brains confirmed via ultrasound).

- MRI Scanner: 1.5 Tesla GE scanner with an 8-channel receiver coil.

- sMRI Acquisition: T2-weighted single-shot fast spin-echo sequence.

- rs-fMRI Acquisition: Echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence; TR = 3000 ms, TE = 60 ms; ~144 volumes (~7 minutes) per scan.

II. Preprocessing Steps (Pre-Censoring)

- Image Re-orientation: Standardize image orientation.

- Within-Volume Realignment: Correct for slice-wise misalignment.

- De-spiking: Replace outlier volumes with smoothed values (e.g., using

3dDespikefrom AFNI). - Bias-Field Correction: Correct for B1-field inhomogeneities.

- Slice Time Correction: Account for acquisition time differences between slices.

- Motion Correction: Perform rigid-body co-registration of all volumes to a reference volume (e.g., the volume with the lowest outlier fraction). Output: 6 rigid-body motion parameters (3 translational, 3 rotational).

- Conversion of Rotational Parameters: Convert rotational parameters (pitch, yaw, roll) from radians to millimeters using the estimated radius of the individual fetal brain.

- Co-registration & Spatial Smoothing: Align fMRI to T2 anatomical; apply spatial smoothing (FWHM = 4.5 mm).

III. Motion Parameter Calculation and Volume Censoring

Compute Frame-wise Displacement (FD): Calculate the FD for each time point. FD is the Euclidean norm of the first differences of the 6 motion parameters [10].

FD = Σ |ΔTranslationalParameters| + Σ |ΔRotationalParametersinmm|

Set Censoring Threshold: For fetal data, a threshold of FD > 1.5 mm is recommended based on empirical evidence [20] [2].

Generate Censoring Regressors: Identify all time points (volumes) where FD exceeds the 1.5 mm threshold. In AFNI, using

-regress_censor_motion 1.5would censor both the suprathreshold time point and the one following it [10].Incorporate into Nuisance Regression: Include the censoring regressors (indicating which volumes to exclude) in a general linear model (GLM) that also regresses out other nuisance signals. A standard set of 12 nuisance regressors is often used: the 6 motion parameters and their first-order derivatives [2].

IV. Quality Control and Data Retention

- Assess Data Retention: After censoring, evaluate the number of remaining volumes per scan. There is no universally agreed-upon minimum percentage of volumes to retain, but this should be part of a pre-study plan. The goal is to balance data quality with the avoidance of biasing group results by excluding too many subjects [6] [10].

- Visual and Quantitative QC: Use qualitative (e.g., visual inspection of FC maps) and quantitative metrics (e.g., temporal signal-to-noise ratio) to finalize data inclusion [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Tools for Fetal rs-fMRI Motion Correction

| Tool / "Reagent" | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFNI | Software Suite | Data processing and analysis (e.g., 3dDespike, 3dvolreg, 3dTproject). |

Used for de-spiking, motion correction, and nuisance regression including censoring [2] [3] [10]. |

| Bioimage Suite | Software Suite | Fetal-specific image analysis tools. | Provides fetalmotioncorrection function for motion correction in fetal data [2]. |

| FSL | Software Suite | Brain extraction, tissue segmentation, and image registration. | Used for co-registration of fMRI to anatomical scans [2]. |

| Frame-wise Displacement (FD) | Metric | Quantifies volume-to-volume head motion. | Serves as the primary criterion for volume censoring [20] [2] [6]. |

| Nuisance Regressors | Model Component | Statistically removes non-neuronal signals from BOLD data. | Typically includes motion parameters, derivatives, and signals from white matter and CSF [2] [3]. |

| RS-FetMRI Pipeline | Standardized Pipeline | Semi-automatic preprocessing for fetal rs-fMRI. | Promotes reproducibility and standardizes the application of techniques like censoring [2]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for processing fetal rs-fMRI data, highlighting the decision points for volume censoring.

Implementing Censoring: Methodological Strategies for Diverse Research Applications

In-scanner head motion remains the most significant source of artifact in functional MRI (fMRI), introducing systematic biases that profoundly impact functional connectivity (FC) measures [21]. Even after application of standard denoising algorithms, associations between head motion and FC patterns persist, potentially leading to spurious brain-behavior associations in volumetric analysis [21] [2]. This technical challenge is particularly acute when studying populations with inherently higher motion, such as children, psychiatric populations, and fetuses [21] [2] [6].

Motion censoring (also termed "volume censoring" or "scrubbing") has emerged as a critical post-processing technique to mitigate these lingering effects. The procedure involves identifying and excluding individual fMRI volumes (timepoints) that exceed predetermined motion thresholds from subsequent analysis [2] [6]. This guide provides a standardized, step-by-step protocol for integrating motion censoring into two prominent preprocessing pipelines: ABCD-BIDS for adolescent brain data and RS-FetMRI for fetal imaging, within the broader context of establishing validated motion censoring thresholds for volumetric research.

Quantitative Foundations: Evaluating Censoring Efficacy

Empirical Evidence of Censoring Impact

Table 1: Documented Effects of Motion and Censoring Across Populations

| Study Population | Pipeline | Key Finding on Motion Impact | Censoring Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents (n=7,270) [21] | ABCD-BIDS | 42% (19/45) of traits showed significant motion overestimation post-denoising. | FD < 0.2 mm reduced overestimation to 2% (1/45) of traits. |

| Fetuses (n=120 scans) [2] [20] | Custom Fetal Pipeline | FC profiles predicted motion (r=0.09 ± 0.08; p<10⁻³) after nuisance regression. | Censoring (1.5 mm threshold) improved neurobiological feature prediction (Accuracy: 55.2% vs. 44.6%). |

| First-Grade Children (n=108) [6] | ICA-based Denoising | Significant motion-artifact correlations pre-censoring. | FD < 0.3 mm enabled usable data retention for 83% of participants. |

Framewise Displacement Threshold Selection Guide

Table 2: Operational Guidelines for Censoring Thresholds

| Censoring Threshold (FD) | Use Case & Rationale | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 mm | Maximum Rigor: Recommended for trait-FC studies where motion-correlated biases are a primary concern [21]. | Maximizes data exclusion; may bias sample by excluding high-motion subjects [21]. |

| 0.3 mm | Balanced Approach: Effective for pediatric cohorts with moderate-high motion, balancing rigor and subject retention [6]. | Retains more subjects/data while still mitigating major artifacts [6]. |

| 0.5 - 1.5 mm | Fetal Imaging & High-Motion Contexts: Necessary for unconstrained motion environments (e.g., fetal fMRI) [2]. | Retains sufficient data volumes for analysis in challenging acquisition scenarios. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Protocol 1: Integrating Censoring into the ABCD-BIDS Pipeline

The ABCD-BIDS pipeline is a standardized processing workflow for the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study dataset, which includes global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion parameter regression, and despiking [21] [22]. The following steps detail the integration of motion censoring into this framework.

Step 1: Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD)

- Input: The 6 rigid-body head motion parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) derived from volume realignment.

- Method: Compute FD for each timepoint (volume)

tusing the formula:FD(t) = |ΔX| + |ΔY| + |ΔZ| + |Δα| + |Δβ| + |Δγ|whereΔrepresents the derivative (difference) of the motion parameter between timepointtandt-1. Rotational displacements must be converted from radians to millimeters by assuming a typical head radius (e.g., 50 mm) [21] [2]. - Output: A single-column text file (

fd.txt) containing the FD timeseries.

Step 2: Generate Censoring Mask

- Input: The

fd.txtfile from Step 1 and a chosen FD threshold (see Table 2). - Method:

- Identify all timepoints

twhereFD(t) > threshold. - Additionally, flag one timepoint before and two timepoints after each high-motion volume to account for spin-history effects [21].

- Create a binary censoring mask (e.g.,

censoring_mask.1D), where0indicates a censored volume and1indicates a retained volume.

- Identify all timepoints

- Output: Censoring mask file.

Step 3: Apply Censoring in Connectivity Analysis

- Input: Preprocessed BOLD timeseries, censoring mask, and parcellation atlas.

- Method:

- Extract average BOLD signal from each brain region defined by the atlas for each timepoint.

- Retain only the timepoints marked

1in the censoring mask. - Compute the Pearson correlation matrix from the censored BOLD timeseries to derive the final functional connectivity matrix.

- Output: Denoised, motion-censored functional connectivity matrix.

Core Protocol 2: Motion Censoring for Fetal rs-fMRI (RS-FetMRI Pipeline)

Fetal fMRI presents unique challenges due to extreme and unpredictable motion. The RS-FetMRI pipeline is a semi-automated, standardized preprocessing pipeline developed for this purpose [2].

Step 1: Robust Motion Estimation and FD Calculation

- Input: Fetal rs-fMRI volumes undergoing slice-to-volume reconstruction and motion correction.

- Method:

- Fetal motion is corrected using tools like

fetalmotioncorrectionfrom Bioimage Suite, which performs rigid-body co-registration to a reference volume [2]. - Calculate FD from the derived motion parameters as in Protocol 1, Step 1. Due to the nature of fetal motion, careful review of motion parameter plots is recommended.

- Fetal motion is corrected using tools like

- Output: FD timeseries for the fetal scan.

Step 2: Optimized Volume Censoring

- Input: FD timeseries.

- Method:

- Apply a higher, fetal-appropriate FD threshold (e.g., 1.5 mm) to account for greater inherent motion [2].

- Generate the censoring mask, flagging high-motion volumes and their neighbors.

- A critical additional step: Ensure that a sufficient number of consecutive uncensored volumes remain to allow for reliable correlation estimation. If excessive censoring occurs, consider adjusting the threshold or the scan duration.

- Output: Censoring mask tailored for fetal connectivity analysis.

Step 3: Censoring-Aware Functional Connectivity

- Input: Motion-corrected and sliced BOLD data, censoring mask.

- Method:

- Only retained volumes are used to compute the correlation matrix.

- Given the potential for high data loss, report the number of volumes used in the final analysis for each subject as a key quality metric.

- Validate the pipeline by testing its ability to predict neurobiological features like gestational age, where improved prediction accuracy indicates successful noise reduction [2].

- Output: Motion-mitigated fetal functional connectome.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: Generalized Motion Censoring Workflow

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Pipeline Implementation

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Censoring Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| ABCD-BIDS Community Collection (ABCC) [22] | Data Repository | Provides standardized, BIDS-formatted ABCD Study data, including raw inputs and derivatives, essential for reproducible processing. |

| RS-FetMRI Pipeline [2] | Preprocessing Pipeline | A semi-automated, standardized pipeline for fetal rs-fMRI preprocessing, including motion correction. |

| fMRIPrep [23] | Preprocessing Pipeline | A robust, "glass-box" fMRI preprocessing pipeline that performs minimal preprocessing (motion correction, normalization, etc.), generating quality reports. |

| Bioimage Suite [2] | Software Tool | Used within the RS-FetMRI pipeline for fetal motion correction and estimation of motion parameters. |

| AFNI (3dToutcount, 3dDespike) [2] | Software Tool | Provides utilities for identifying outlier volumes and despiking, often used in conjunction with censoring. |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) [21] [2] | Quantitative Metric | The scalar summary of head motion between consecutive volumes, serving as the primary criterion for volume censoring. |

| Censoring Mask [21] [6] | Data Product | A binary regressor file indicating which volumes to include (1) or censor (0) in final analysis. |

Framewise Displacement (FD) censoring, or "scrubbing," is a critical preprocessing technique in functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) analysis to mitigate the confounding effects of head motion. The method involves identifying and statistically excluding individual fMRI volumes that exceed a specific motion threshold. This process is vital for reducing motion-induced artifacts that can compromise the integrity of functional connectivity and activation maps. However, the field lacks a universal standard for the FD threshold, leading to the application of varied cut-offs across studies. This review synthesizes the rationale and empirical evidence behind commonly used FD censoring cut-offs, such as 0.2 mm, 0.5 mm, and 1.5 mm, providing a structured guide for researchers to make informed decisions tailored to their specific study designs and populations.

Common FD Censoring Cut-offs and Their Rationale

The choice of an FD threshold involves a delicate trade-off between data quality and data retention. Stricter thresholds (lower FD values) remove more motion-contaminated data but result in greater data loss, which can exclude participants from analysis. The following table summarizes the prevalent cut-offs found in the literature and their justifications.

Table 1: Common FD Censoring Cut-offs and Their Applications

| FD Threshold | Rationale and Empirical Support | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 mm | Considered a stringent threshold. Micromotion greater than 0.2 mm can systematically bias estimates of resting-state functional connectivity [24]. This threshold is used to ensure high sensitivity to head motion and data quality. | Studies prioritizing data purity over sample size; investigations in populations with typically low motion [24]. |

| 0.3 mm | An intermediate threshold often deployed in challenging cohorts. One study on first-grade children used this threshold, which allowed them to retain 83% of participants while meeting rigorous data quality standards [14]. | Pediatric populations or other groups where higher motion is anticipated, aiming to balance quality and data retention [14]. |

| 0.5 mm | A common and lenient threshold. Research has shown that prediction models for head motion yielded similar accuracy with a lenient threshold of 0.5 mm compared to a stricter 0.2 mm threshold [24]. This suggests it can be sufficient for certain analyses. | Large-scale studies or those where participant retention is a primary concern; may be used as an initial, less conservative filtering step. |

The Impact of Threshold Choice on Analysis

The selection of a censoring threshold can directly influence study outcomes. Stricter censoring (e.g., FD = 0.2 mm) does not always guarantee superior results. One evaluation found that while frame censoring with modest data loss (1-2%) could improve outcomes, no single approach consistently outperformed others across all datasets and tasks [15]. The optimal strategy depends on the specific dataset and the outcome metric of interest, such as group-level t-statistics or single-subject reliability [15].

Experimental Protocols for FD Censoring

Implementing FD censoring requires integration into a broader preprocessing pipeline. The following workflow details a protocol adapted from studies that successfully managed high-motion data [15] [14].

The diagram below outlines the key decision points in a typical FD censoring protocol.

Detailed Protocol Steps

Step 1: Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD)

FD quantifies the relative head movement from one volume to the next. It is computed as the sum of the absolute derivatives of the six rigid-body realignment parameters (three translations and three rotations). Rotational displacements are typically converted from degrees to millimeters by assuming a brain radius of 50 mm [15].

Step 2: Select an Appropriate Threshold

Choose an FD threshold based on your study's requirements (refer to Table 1). For a balanced approach in a general population, a threshold of 0.2 mm to 0.3 mm is often effective. For studies with high-motion participants, a threshold of 0.5 mm may be necessary to retain a viable sample size [24] [14].

Step 3: Identify and Handle Bad Volumes

- Identify volumes where the FD value exceeds the selected threshold.

- Handle bad volumes using one of two primary methods:

- Nuisance Regressors in GLM: Incorporate "scan-nulling" regressors (one-hot encoding) for each bad volume into the general linear model (GLM). This method statistically excludes the contaminated volumes without altering the data's temporal structure [15].

- Censoring and Concatenation: Remove the identified bad volumes entirely and concatenate the remaining clean segments. Note that this approach invalidates subsequent temporal filtering, so filtering must be performed before censoring or avoided [14].

Step 4: Integrate with Denoising

After censoring, employ additional denoising techniques to remove residual artifacts. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) based denoising (e.g., with FSL's ICA-AROMA or a trained classifier) is highly effective for this purpose and can reduce the need for separate nuisance regression of motion parameters and physiological signals [14].

Step 5: Proceed to Final Analysis

Once the data has been censored and denoised, it is suitable for final analyses, such as functional connectivity mapping or task-based activation analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key software and data resources essential for implementing FD censoring protocols.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Solutions for FD Censoring Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| FIRMM Software | Framewise Integrated Real-time MRI Monitoring. Tracks head motion in real-time during scan acquisition [14]. | Allows researchers to collect sufficient low-motion data by extending scans until a target of clean frames is met, crucial for high-motion cohorts. |

| FSL (FMRIB Software Library) | A comprehensive library of MRI analysis tools. Includes utilities for calculating FD and performing ICA. | Used for data preprocessing, motion parameter extraction, and implementing ICA-based denoising (e.g., with FSL's MELODIC). |

| ICA-AROMA | An ICA-based tool for Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts. Automatically identifies and removes motion-related components from fMRI data. | A key denoising step applied after initial censoring to remove residual motion artifacts not captured by the FD threshold. |

| High-Quality Multiband fMRI Sequences | Pulse sequences (e.g., CMRR multiband EPI) that allow for accelerated data acquisition [14]. | Enables shorter TRs, which increases the number of data points and can improve the robustness of analyses after censoring. |

| OpenNeuro Datasets | A public repository of neuroimaging data [15]. | Provides accessible data for developing and benchmarking new motion correction pipelines across diverse tasks and populations. |

The selection of an FD censoring cut-off is a foundational step in fMRI preprocessing that directly impacts data quality, sample size, and the validity of scientific inferences. While this review outlines evidence-based guidance for common thresholds (0.2 mm, 0.3 mm, and 0.5 mm), the optimal choice is context-dependent. Researchers must weigh factors such as participant population, target analysis, and the trade-off between data cleanliness and retention. Emerging best practices suggest that combining a thoughtfully chosen FD threshold with advanced denoising techniques like ICA provides a robust defense against motion artifacts, enabling the inclusion of more diverse and representative populations in neuroimaging research.

Motion artifacts represent a significant confound in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), potentially distorting measured brain signals and introducing spurious findings in functional connectivity (FC) analyses. While motion affects neuroimaging across all populations, the nature and extent of the problem, along with optimal mitigation strategies, vary considerably between fetal, pediatric, and adult subjects. Nuisance regression of motion parameters, while effective in reducing the association between motion and blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) time series, has proven insufficient for eliminating motion's lingering effects on large-scale functional connectivity. Volume censoring, the process of identifying and excluding high-motion volumes from analysis, has emerged as a critical supplementary technique. This protocol outlines population-specific strategies for implementing motion censoring, providing a structured framework for researchers to enhance the validity and biological accuracy of their neurodevelopmental and clinical findings.

Population-Specific Censoring Protocols

Fetal Neuroimaging Protocol

Background: Acquiring high-quality fetal resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) is particularly challenging due to completely unpredictable and unconstrained fetal head motion. Establishing robust censoring protocols is therefore critical to avoid motion-related bias in studies of the developing brain.

Recommended Censoring Threshold: A systematic evaluation demonstrated that a framewise displacement (FD) threshold of 1.5 mm optimizes the trade-off between data retention and noise reduction in fetal data [20] [2]. At this threshold, censoring significantly improves the ability of rs-fMRI data to predict neurobiological features.

Key Evidence and Outcomes: The efficacy of the fetal censoring protocol is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Efficacy of Volume Censoring in Fetal rs-fMRI

| Metric | Performance without Censoring | Performance with 1.5 mm FD Censoring | Significance and Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion-FC Association | FC profiles significantly predicted average FD (r = 0.09 ± 0.08; p < 10⁻³) after nuisance regression alone [20] | Not explicitly reported for this specific metric post-censoring | Indicates that nuisance regression alone is insufficient to eliminate motion effects on functional connectivity [20] |

| Neurobiological Feature Prediction | Accuracy = 44.6 ± 3.6% [2] | Accuracy = 55.2 ± 2.9% [2] | Censoring enhanced prediction accuracy for gestational age and biological sex, confirming improved signal-to-noise ratio [2] |

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the integrated preprocessing and censoring pipeline for fetal rs-fMRI data:

Pediatric Neuroimaging Protocol

Background: Scanning pediatric populations, especially first-grade children, presents a unique challenge due to their naturally high levels of movement. A combination of acquisition strategies and rigorous post-processing is required to salvage usable data.

Recommended Censoring Threshold: For first-grade children (ages 6-8), a stringent FD threshold of 0.3 mm has been validated as highly effective [6]. This threshold, combined with Independent Component Analysis (ICA)-based denoising, allowed 83% of participants to be retained while meeting rigorous quality standards [6].

Acquisition Protocol for Low-Motion Data: Achieving low-motion data in children requires proactive acquisition strategies. A 60-minute scan protocol incorporating a mock scanner session, a weighted blanket, and an in-scan incentive system proved highly effective [25]. This approach resulted in a significantly lower proportion of high-motion scans (>0.2 mm FD) compared to a control group (4.2% vs. 33.9%) [25].

Experimental Workflow: The pediatric protocol involves both acquisition and processing innovations, as shown below:

Adult Neuroimaging Protocol

Background: While adults typically exhibit better compliance and lower motion, censoring remains a necessary step for mitigating subtle yet impactful motion artifacts on functional connectivity measures.

Recommended Censoring Thresholds: A comparison of multiple censoring thresholds (0.2 mm, 0.4 mm, and 1.0 mm) is recommended for adult data as part of a comprehensive quality control procedure [3]. The optimal threshold may vary depending on the specific research question and dataset characteristics. The general principle, established in adult studies and applied to other populations, is that nuisance regression alone is insufficient, and combining it with volume censoring is essential for reducing motion-related confounds in functional connectivity analysis [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Source/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal Motion Correction | Corrects for rigid body motion of the fetal head in utero. Critical for initial motion parameter estimation. | Bioimage Suite (fetalmotioncorrection) [2] |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | A scalar quantity quantifying volume-to-volume head motion. The primary metric for censoring decisions. | Calculated from motion regressors (e.g., via AFNI) [2] [3] |

| Nuisance Regressors | Model sources of noise (e.g., head motion, physiological signals) for regression from the BOLD signal. | Typically 6, 12, 24, or 36 motion parameters [2] |

| Volume Censoring Scripts | Implements the identification and removal of high-motion volumes based on FD threshold. | AFNI [3] |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Data-driven method for identifying and removing noise components, often used after censoring. | ICA-based denoising [6] |

| Mock Scanner | A replica MRI environment used to acclimatize and train pediatric participants, reducing in-scanner motion. | Custom-built systems [25] |

The systematic application of motion censoring, tailored to the unique challenges of specific populations, is no longer an optional optimization but a necessary component of rigorous fMRI research. As evidenced, nuisance regression alone fails to fully dissociate head motion from functional connectivity metrics. The integration of a 1.5 mm FD censoring threshold in fetal imaging, a 0.3 mm threshold in pediatric cohorts, and a comparative threshold approach (0.2-1.0 mm) in adult studies provides a validated framework for enhancing the biological validity of findings. By adopting these standardized protocols and utilizing the outlined toolkit, researchers can significantly mitigate motion-related bias, thereby increasing the reliability and interpretability of neurodevelopmental and clinical neuroimaging results.

In fetal resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), the unpredictable and unconstrained motion of the fetal head presents a significant challenge, potentially confounding measured brain signals and limiting the reliability of functional connectivity (FC) measures [2]. While nuisance regression of motion parameters has been widely used, it often fails to eliminate the persistent association between head motion and large-scale brain FC [2] [26]. This case study, framed within broader thesis research on motion censoring thresholds, demonstrates how volume censoring—the identification and removal of high-motion frames—significantly improves the prediction of neurobiological features such as gestational age (GA) and biological sex from fetal rs-fMRI data.

Background and Significance

The Critical Challenge of Motion in Fetal fMRI

Fetal rs-fMRI has emerged as a powerful tool for non-invasive investigation of early brain development in utero [2] [27]. However, its potential is hampered by fetal head motion, which introduces artifacts that can systematically bias functional connectivity measures [2] [27]. Unlike ex utero populations, there are no means to physically restrict fetal head movement during scans, making sophisticated post-processing techniques essential for data salvage and reliability [2] [14].

Limitations of Conventional Motion Correction

Nuisance regression, where the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal is regressed onto translational and rotational head motion parameters, has been effectively used in adult populations to reduce motion influence [2]. However, studies across age groups have revealed that associations between head motion and FC persist even after regression [2] [26]. In fetal populations, this limitation is particularly pronounced, as nuisance regression alone proves insufficient for eliminating motion's impact on whole-brain FC patterns [2].

Experimental Findings: Efficacy of Volume Censoring

Quantitative Improvements in Neurobiological Prediction

The implementation of volume censoring in fetal rs-fMRI preprocessing demonstrates measurable improvements in predicting key neurobiological features. The following table summarizes the core quantitative findings from the cited research:

Table 1: Efficacy of Volume Censoring for Neurobiological Feature Prediction in Fetal rs-fMRI

| Predictive Metric | Performance Without Censoring | Performance With Censoring (1.5 mm FD threshold) | Significance and Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age & Sex Prediction Accuracy | 44.6 ± 3.6% [2] | 55.2 ± 2.9% [2] | Significant improvement in classification accuracy demonstrating enhanced biological signal recovery |

| Motion-FC Association After Nuisance Regression | FC profiles significantly predicted average FD (r = 0.09 ± 0.08; p < 10⁻³) [2] | Not explicitly quantified | Demonstrates lingering motion effects after regression alone, justifying need for censoring |

| Sex Differences in FC Development | Network-level sexual dimorphism observed in fetal brain networks [28] | NA | Provides biological context for sex prediction studies, confirming sexual dimorphism emerges during gestation |

Impact on Functional Connectivity Measures

Volume censoring operates by removing high-motion volumes identified using framewise displacement (FD) thresholds, thereby reducing the introduction of spurious variance into BOLD signals [2] [27]. This process enhances the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of resting-state data, which directly improves the fidelity of functional connectivity maps [2]. The optimal FD threshold identified for fetal data (1.5 mm) represents a balance between removing motion-corrupted data and retaining sufficient volumes for meaningful functional connectivity analysis [2].

Experimental Protocols

Data Acquisition Parameters

The following protocol summarizes the acquisition parameters from the foundational studies cited in this case study:

Table 2: MRI Acquisition Parameters for Fetal rs-fMRI Studies

| Parameter | Study 1: Volume Censoring Effects [2] | Study 2: Sex Differences [28] | Study 3: Motion Corruption Measurement [27] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanner & Coil | 1.5T GE MRI scanner with 8-channel receiver coil [2] | Not specified | 1.5T Philips scanner with SENSE cardiac 5-element coil [27] |

| fMRI Sequence | Echo planar imaging [2] | Resting-state fMRI [28] | BOLD imaging [27] |

| TR/TE | 3000/60 ms [2] | Not specified | 3000/50 ms [27] |

| Voxel Size | 2.58 × 2.58 × 3 mm [2] | Not specified | 1.74 × 1.74 × 3 mm [27] |

| Volumes | 144 volumes (~7 minutes) [2] | Not specified | 96 volumes [27] |

| Subjects | 120 scans from 104 healthy fetuses [2] | 118 fetuses (70 male, 48 female) [28] | 70 fetuses (GA: 19-39 weeks) [27] |

| GA Range | Not specified | 25.9-39.6 weeks [28] | 19 weeks 5 days - 39 weeks 2 days [27] |

Preprocessing Workflow with Volume Censoring

The preprocessing pipeline incorporates multiple steps to address fetal-specific challenges:

- Volume Censoring Implementation: Identify and remove volumes with framewise displacement (FD) exceeding predetermined thresholds (e.g., 1.5 mm) [2].

- Motion Correction: Perform within-volume realignment and volume-to-volume motion correction using rigid body transformation [2].

- Nuisance Regression: Regress BOLD signal onto motion parameters (typically 12-36 regressors), signals from white matter and ventricles, and other physiological confounds [2].

- Spatial Processing: Co-register fMRI to anatomical T2 images, normalize to standardized fetal template space, and apply spatial smoothing [2] [29].

Functional Connectivity and Predictive Analysis

- Network Identification: Apply community detection algorithms (e.g., Infomap) to identify distinct fetal neural networks [28].

- Feature Extraction: Compute functional connectivity matrices between brain regions of interest.

- Machine Learning Application: Utilize algorithms to predict either motion parameters (for quality control) or neurobiological features (GA, sex) from connectivity profiles [2].

- Validation: Employ cross-validation and statistical testing to confirm prediction significance.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Fetal rs-fMRI with Volume Censoring

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Processing Software | AFNI [2], Bioimage Suite [2], FSL [27], SPM [29] | Core processing, motion correction, statistical analysis |

| Fetal-Specific Tools | RS-FetMRI Pipeline [2], fetalmotioncorrection (Bioimage Suite) [2] | Specialized algorithms for fetal motion correction and preprocessing |

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement (FD) [2], FIRMM (real-time monitoring) [14] | Quantify head motion, identify volumes for censoring |

| Denoising Approaches | ICA-AROMA [14], CompCor [30], Global Signal Regression [27] | Remove motion and physiological artifacts beyond simple regression |

| Template Resources | Age-matched fetal templates [29], Mean-age templates [29] | Spatial normalization for developing brains |

| Quality Metrics | QC-FC correlation [27], Temporal SNR [14], Prediction accuracy [2] | Validate pipeline efficacy and data quality |

Conceptual Framework

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between motion corruption, the censoring process, and the ultimate improvement in neurobiological prediction:

Discussion and Research Applications

Implications for Developmental Neuroscience

The improved prediction of gestational age and biological sex using censored data reflects the recovery of meaningful neurobiological signal previously obscured by motion artifacts [2]. This advancement enables more precise investigation of early brain development, including the emergence of sexual dimorphism in functional brain systems during gestation [28]. For researchers studying typical and atypical neurodevelopment, these methods provide enhanced capability to detect subtle alterations in functional connectivity resulting from prenatal exposures or genetic factors [29].

Application in Pharmaceutical Development

For drug development professionals, these refined analytical approaches offer potential applications in:

- Safety Pharmacology: More sensitive detection of functional neurodevelopmental changes following prenatal drug exposure.

- Biomarker Development: Identification of functional connectivity signatures as potential biomarkers for neurodevelopmental disorders.

- Clinical Trial Design: Improved methods for assessing central nervous system effects of prenatal therapeutics.

This case study demonstrates that volume censoring, when combined with nuisance regression, significantly improves the fidelity of fetal rs-fMRI data by reducing motion-related artifacts. The consequent enhancement in predicting gestational age and biological sex confirms the critical importance of appropriate motion censoring thresholds in volumetric analysis research. These protocols provide researchers with validated methods for extracting more reliable neurobiological information from challenging fetal fMRI data, advancing our capacity to study the earliest origins of brain development and dysfunction.

In both modern neuroimaging and drug discovery, censoring—the practice of handling data that is only partially observed or lies beyond a detection threshold—plays a critical role in ensuring accurate and reproducible results. In Brain-Wide Association Studies (BWAS), this manifests as thresholding of statistical maps, where subthreshold data is often omitted, while in drug discovery, it appears as censored experimental labels in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and incomplete reporting of adverse events in clinical trials. Traditional approaches that ignore or naively impute censored values can introduce significant bias, undermine statistical power, and lead to flawed scientific interpretations and decision-making. This article details advanced protocols for properly handling censored data in these fields, leveraging Bayesian methods and transparent reporting practices to enhance the reliability of volumetric analysis and pharmaceutical development pipelines.

Censoring in Brain-Wide Association Studies (BWAS)

The Challenge of Opaque Thresholding

In neuroimaging, particularly in volumetric analyses and BWAS, standard practice has involved opaque thresholding, where only voxels surpassing a strict statistical threshold are displayed, and all subthreshold data is hidden [31]. This approach is rooted in historical localization-focused neuroscience but is misaligned with the modern understanding of the brain as a distributed, interconnected system.

Key limitations of opaque thresholding include [31]:

- Unrealistic Biology: It creates an artificial ON/OFF picture of brain activity, inconsistent with the continuous, graded nature of neural signals.

- Loss of Context: It removes information about the spatial extent of effects and their network contexts, hindering comprehensive interpretation.

- Interpretation Bias: It hypersensitizes results to arbitrary threshold choices and undermines cross-study reproducibility and meta-analyses.