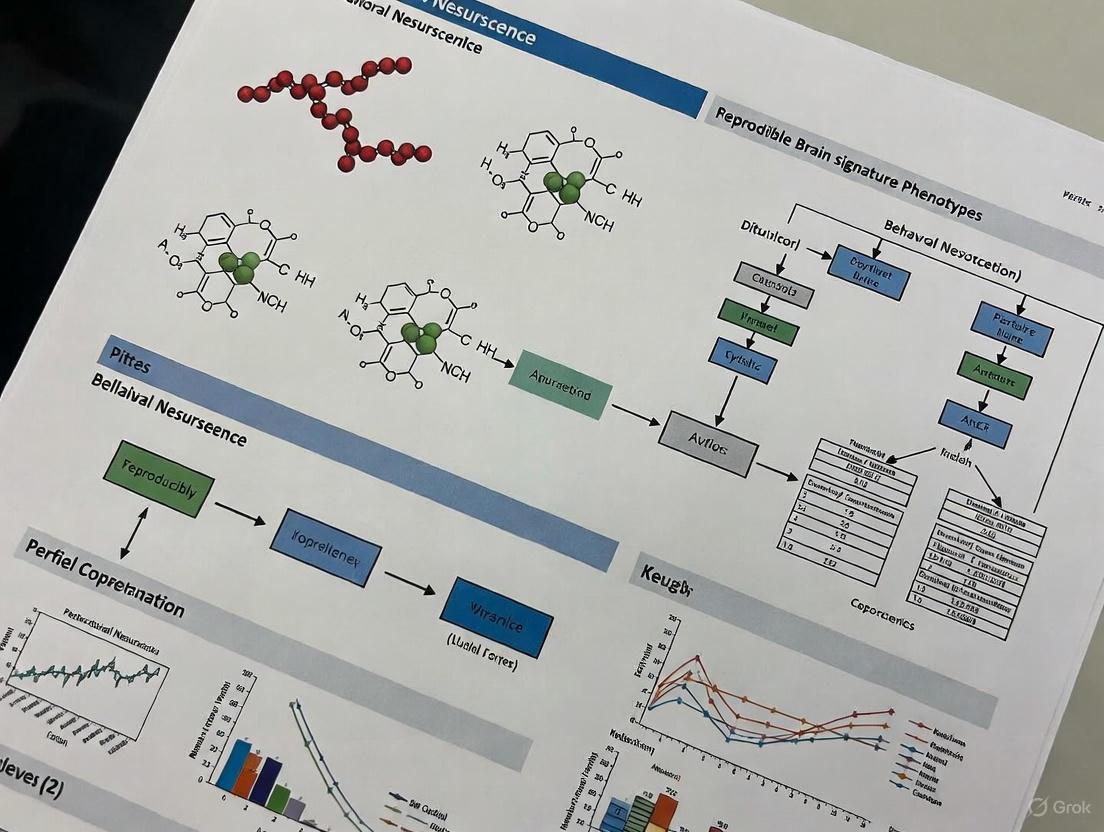

Overcoming the Pitfalls in Reproducible Brain-Phenotype Signatures: A Roadmap for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for establishing reproducible brain-phenotype signatures, a critical challenge in neuroscience and neuropharmacology.

Overcoming the Pitfalls in Reproducible Brain-Phenotype Signatures: A Roadmap for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for establishing reproducible brain-phenotype signatures, a critical challenge in neuroscience and neuropharmacology. We explore the foundational obstacles—from sample size limitations and phenotypic harmonization to data quality and access—that have plagued brain-wide association studies (BWAS). The piece details methodological advances in data processing, harmonization, and predictive modeling that enhance reproducibility. It further offers troubleshooting strategies for common technical and analytical pitfalls and outlines rigorous validation and comparative frameworks to ensure generalizability. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes the latest evidence and best practices to foster robust, clinically translatable neuroscience.

Why Brain-Phenotype Associations Fail: Unpacking the Foundational Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the "sample size crisis" in Brain-Wide Association Studies (BWAS)? The sample size crisis refers to the widespread failure of BWAS to produce reproducible findings because typical study samples are too small. These studies aim to link individual differences in brain structure or function to complex cognitive or mental health traits, but the true effects are much smaller than previously assumed. Consequently, small-scale studies are statistically underpowered, leading to inflated effect sizes and replication failures [1] [2].

2. Why do BWAS require such large sample sizes compared to other neuroimaging studies? BWAS investigates correlations between common, subtle variations in the brain and complex behaviors. These brain-behavior associations are inherently small. Research shows the median univariate effect size (|r|) in a large, rigorously denoised sample is approximately 0.01 [1]. Detecting such minuscule effects reliably requires very large samples to overcome sampling variability, whereas classical brain mapping studies (e.g., identifying the region activated by a specific task) often have larger effects and can succeed with smaller samples [1] [2].

3. My lab can't collect thousands of participants. Is BWAS research impossible for us? Not necessarily, but it requires a shift in strategy. The most straightforward approach is to leverage large, publicly available datasets like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, the UK Biobank (UKB), or the Human Connectome Project (HCP) [1] [2]. Alternatively, focus on forming large consortia to aggregate data across multiple labs [3] [2]. If collecting new data is essential, our guide on optimizing scan time versus sample size below can help maximize the value of your resources.

4. How does scan duration interact with sample size in fMRI-based BWAS? There is a trade-off between the number of participants (sample size) and the amount of data collected per participant (scan time). Initially, for scans of ≤20 minutes, total scan duration (sample size × scan time per participant) is a key determinant of prediction accuracy, making sample size and scan time somewhat interchangeable [4]. However, sample size is ultimately more critical. Once scan time reaches a certain point (e.g., beyond 20-30 minutes), increasing the sample size yields greater improvements in prediction accuracy than further increasing scan time [4].

5. What is a realistic expectation for prediction accuracy in BWAS? Even with large samples, prediction accuracy for complex cognitive and mental health phenotypes is often modest. Analyses show that increasing the sample size from 1,000 to 1 million participants can lead to a 3- to 9-fold improvement in performance. However, the extrapolated accuracy remains worryingly low for many traits, suggesting a fundamental limit to the predictive information contained in current brain imaging data for these phenotypes [5].

Quantitative Data at a Glance

Table 1: Observed Effect Sizes and Replicability in BWAS (from Marek et al., 2022) [1]

| Metric | Typical Small Study (n=25) | Large-Scale Study (n~3,900) | Key Finding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | r | effect size | Often reported > 0.2 | ~0.01 | Extreme effect size inflation in small samples. | ||

| Top 1% of | r | effects | Highly inflated | > 0.06 | Largest reproducible effect was | r | = 0.16. |

| 99% Confidence Interval | ± 0.52 | Narrowed substantially | Small samples can produce opposite conclusions. | ||||

| Replication Rate | Very Low | Begins to improve in the thousands | Thousands of participants are needed for reproducibility. |

Table 2: Prediction Performance as a Function of Sample Size (from Schulz et al., 2023) [5]

| Sample Size | Prediction Performance (Relative Gain) | Implication for Study Design |

|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | Baseline | This is a modern minimum for meaningful prediction attempts. |

| 10,000 | Improves by several fold | Similar to major current datasets (e.g., ABCD, UKB substudies). |

| 100,000 | Continued improvement | Necessary for robustly detecting finer-grained effects. |

| 1,000,000 | 3- to 9-fold gain over n=1,000 | Performance reserves exist but accuracy for some phenotypes may remain low. |

Table 3: Cost-Effective Scan Time for fMRI BWAS (from Lydon-Staley et al., 2025) [4] This table summarizes the trade-off between scan time and sample size for a fixed budget, considering overhead costs like recruitment.

| Scenario | Recommended Minimum Scan Time | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| General Resting-State fMRI | At least 30 minutes | This was, on average, the most cost-effective duration, yielding ~22% savings over 10-min scans. |

| Task-based fMRI | Can be shorter than for resting-state | The structured evoked activity can sometimes lead to higher efficiency. |

| Subcortical-to-Whole-Brain BWAS | Longer than for resting-state | May require more data to achieve stable connectivity estimates. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust BWAS

Protocol 1: Designing a New BWAS with Optimized Resources

This protocol helps balance participant recruitment and scan duration when resources are limited.

- Budget Calculation: Determine your total budget. Subtract the fixed overhead costs per participant (recruitment, screening, clinician time) [4]. The remainder determines how you can trade off between the number of participants (N) and scan time per participant (T).

- Feasibility Space: Calculate multiple feasible (N, T) pairs within your budget.

- Optimization: Use the established principle that prediction accuracy increases with the logarithm of the total scan duration (N × T) [4].

- Decision Rule: While sample size and scan time are initially interchangeable, always prioritize a larger sample size. However, do not reduce scan time below 20-30 minutes, as this is empirically cost-inefficient and leads to poor data quality [4]. Overshooting the optimal scan time is cheaper than undershooting it.

Protocol 2: Conducting a Power Analysis for BWAS

Traditional power analysis is challenging because true effect sizes are small and poorly characterized. Use this practical approach.

- Use Realistic Effect Sizes: Do not rely on inflated effects from small-scale literature. Use tools like the BrainEffeX web app to explore realistic, empirically derived effect sizes from large datasets for analyses similar to yours [6].

- Define Your Target: Determine the smallest effect size of practical interest (SESOI). For complex behaviors, even correlations of r = 0.1 - 0.3 may be meaningful [3].

- Calculate Sample Size: Use standard power calculation software (e.g., G*Power [7]) with the empirically derived effect size, a power of at least 0.8, and an alpha of 0.05. Be prepared for the required N to be in the thousands.

- Leverage Large Public Datasets: For a pilot study or initial discovery, always consider using an existing large-scale dataset like UK Biobank or ABCD to obtain stable, reproducible effect estimates before collecting new data [1] [5].

Protocol 3: Mitigating Bias in Brain-Phenotype Models

Models can fail for individuals who defy stereotypical profiles associated with a phenotype, such as certain sociodemographic or clinical covariates [8].

- Test for Structured Failure: After building a predictive model, don't just look at overall accuracy. Analyze if misclassification is random or systematic. Reliable, phenotype-specific model failure indicates potential bias [8].

- Interrogate the Phenotype: Critically assess if your behavioral or clinical measure is a pure reflection of the intended construct, or if it is confounded by sociodemographic, cultural, or clinical factors [8].

- Report Transparently: Clearly report effect sizes and confidence intervals for all analyses, regardless of statistical significance. This provides a more accurate picture of the association strength for future meta-science and power analyses [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Resources for reproducible BWAS

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to BWAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCD, UK Biobank, HCP | Data Repository | Provides large-scale, open-access neuroimaging and behavioral data. | Enables high-powered discovery and replication without new data collection [1] [5]. |

| BrainEffeX | Web Application | Interactive explorer for empirically derived fMRI effect sizes from large datasets. | Informs realistic power calculations and study planning [6]. |

| G*Power / OpenEpi | Software Tool | Performs prospective statistical power analyses for various study designs. | Calculates necessary sample size given an effect size estimate, power, and alpha [7]. |

| Optimal Scan Time Calculator | Online Calculator | Models the trade-off between fMRI scan time and sample size for prediction accuracy. | Helps optimize study design for cost-effectiveness [4]. |

| Regularized Linear Models | Analysis Method | Machine learning technique (e.g., kernel ridge regression) for phenotype prediction. | A robust and highly competitive approach for building predictive models from high-dimensional brain data [4] [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Navigating Bifactor Model Harmonization

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when harmonizing disparate psychiatric assessments using bifactor models and provides step-by-step solutions.

1. Problem: Poor Model Fit After Harmonization

- Symptoms: The bifactor model shows unacceptable fit indices (e.g., CFI < 0.90, RMSEA > 0.08) when applied to harmonized items from different instruments.

- Impact: Results are unreliable and may not be valid for cross-study comparisons, undermining the entire harmonization effort.

- Diagnostic Checks:

- Confirm that item content is semantically equivalent across instruments.

- Check factor loadings; weak loadings (< 0.3) on the general or specific factors indicate poor item performance.

- Test for instrument-specific measurement non-invariance.

- Solutions:

- Quick Fix: Re-specify the model by removing items with consistently low factor loadings.

- Standard Resolution: Use a phenotypic reference panel—a supplemental sample with complete data on all items from all instruments—to improve model linking [9].

- Root Cause Fix: Implement a Bi-Factor Integration Model (BFIM) that explicitly models a general factor across all studies and orthogonal specific factors that capture cohort-specific variances [9].

2. Problem: Specific Factors Lack Reliability

- Symptoms: The specific factors (e.g., internalizing, externalizing) in the bifactor model show low reliability indices (e.g., H-index < 0.7, Factor Determinacy < 0.8) despite a reliable p-factor.

- Impact: Specific dimensions of psychopathology cannot be interpreted meaningfully, limiting the clinical utility of the model.

- Diagnostic Checks:

- Calculate model-based reliability indices (OmegaH, ECV) for each specific factor.

- Check if the specific factors predict relevant external criteria (e.g., symptom impact on daily life).

- Solutions:

- Quick Fix: Focus analysis and interpretation only on the general p-factor, which typically demonstrates higher and more consistent reliability [10] [11].

- Standard Resolution: Test different established bifactor model configurations from the literature to find one with acceptable reliability for your specific data and harmonization goal [11].

- Root Cause Fix: Acknowledge that harmonized specific factors may have inherently limited reliability. Use them only in conjunction with other validating evidence and clearly communicate this limitation in research findings.

3. Problem: Low Authenticity of Harmonized Factor Scores

- Symptoms: Factor scores derived from the harmonized (limited item pool) model show low correlation (> 0.5 Z-score difference) with scores from the original full-item models.

- Impact: The harmonized measure does not adequately represent the original construct, leading to misinterpretation of results.

- Diagnostic Checks:

- Calculate the correlation between factor scores from the harmonized and original models.

- Determine the percentage of participants for whom the factor score difference exceeds 0.5 Z-scores.

- Solutions:

- Quick Fix: Use the harmonized models only for the general p-factor, which typically shows high authenticity (correlations > 0.89 with original models) [10].

- Standard Resolution: Be transparent about authenticity limitations, especially for specific factors, and perform sensitivity analyses to quantify its impact on your main conclusions.

- Root Cause Fix: Select a harmonization model that has demonstrated high authenticity in previous studies, even if it requires using a larger set of common items.

4. Problem: Failure of Measurement Invariance Across Instruments

- Symptoms: The bifactor model structure or parameters differ significantly between the original instruments being harmonized.

- Impact: Observed score differences may reflect methodological artifacts rather than true psychological differences, making combined analysis invalid.

- Diagnostic Checks:

- Conduct multi-group confirmatory factor analysis to test for configural, metric, and scalar invariance.

- Look for significant differences in model fit when factor loadings and item thresholds are constrained to be equal across groups.

- Solutions:

- Quick Fix: Report the lack of invariance as a significant limitation of the harmonized measure.

- Standard Resolution: Use a harmonization model that has been previously validated for instrument invariance. Research suggests that only about 40% of bifactor model configurations (5 out of 12 in one study) demonstrate instrument invariance [10].

- Root Cause Fix: Implement a moderated non-linear factor analysis (MNLFA) that allows item parameters to vary systematically by instrument, thereby formally modeling the measurement differences rather than assuming they don't exist [9].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is phenotype harmonization and why is it particularly challenging in psychiatric research? Phenotype harmonization is the process of combining data from different assessment instruments to measure the same underlying construct, which is essential for large-scale consortium research [10]. It is particularly challenging in psychiatry because most constructs (e.g., depression, aggression) are latent traits measured indirectly through questionnaires with varying items, response scales, and cultural interpretations. Different questionnaires often tap into different aspects of a behavioral phenotype, and simply creating sum scores of available items ignores these systematic measurement differences, introducing heterogeneity and reducing power in subsequent analyses [9].

Q2: What are the key advantages of using bifactor models for harmonization? Bifactor models provide a sophisticated approach to harmonization by simultaneously modeling a general psychopathology factor (p-factor) that is common to all items and specific factors that capture additional variance from subsets of items [10] [9]. Key advantages include:

- Separating general psychopathology from specific dimensions (e.g., internalizing, externalizing)

- Accounting for measurement error in the phenotype score

- Allowing items from different instruments to contribute differentially to the underlying trait

- Providing a common metric for the phenotype across different studies and instruments [9]

Q3: Our team is harmonizing CBCL and GOASSESS data. How many bifactor model configurations should we consider? Your team should be aware that there are at least 11 published bifactor models for the CBCL alone, ranging from 39 to 116 items [11]. When harmonizing CBCL with GOASSESS, empirical evidence suggests that only about 5 out of 12 model configurations demonstrated both acceptable model fit and instrument invariance [10]. Systematic evaluation of these existing models is recommended rather than developing a new model from scratch.

Q4: What is a "phenotypic reference panel" and when is it necessary for harmonization? A phenotypic reference panel is a supplemental sample of participants who have completed all items from all instruments being harmonized [9]. This panel is particularly necessary when the primary studies have completely non-overlapping items (e.g., Study A uses Instrument X, Study B uses Instrument Y). The reference panel provides the necessary linking information to place scores from all participants on a common metric. Simulations have shown that such a panel is crucial for realizing power gains in subsequent genetic association analyses [9].

Q5: How reproducible are brain-behavior associations in harmonized studies, and what sample sizes are needed? Reproducible brain-wide association studies (BWAS) require much larger samples than previously thought. While the median neuroimaging study has about 25 participants, BWAS typically show very small effect sizes (median |r| = 0.01), with the top 1% of associations reaching only |r| = 0.06 [1]. At small sample sizes (n = 25), confidence intervals for these associations are extremely wide (r ± 0.52), leading to both false positives and false negatives. Reproducibility begins to improve significantly only when sample sizes reach the thousands [1].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Bifactor Models in CBCL-GOASSESS Harmonization [10]

| Model Performance Indicator | P-Factor | Internalizing Factor | Externalizing Factor | Attention Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Score Correlation (Harmonized vs. Original) | > 0.89 | 0.12 - 0.81 | 0.31 - 0.72 | 0.45 - 0.68 |

| Participants with >0.5 Z-score Difference | 6.3% | 18.5% - 50.9% | 15.2% - 41.7% | 12.8% - 29.4% |

| Typical Reliability (H-index) | Acceptable in most models | Variable | Variable | Acceptable in most models |

| Prediction of Symptom Impact | Consistent across models | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Consistent across models |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotype Harmonization Studies [10] [9] [12]

| Research Reagent | Function in Harmonization | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bi-Factor Integration Model (BFIM) | Provides a single common phenotype score while accounting for study-specific variability | Models a general factor across all studies and orthogonal specific factors for cohort-specific variance [9] |

| Phenotypic Reference Panel | Enables linking of different instruments by providing complete data on all items | Supplemental sample that completes all questionnaires from all contributing studies [9] |

| Measurement Invariance Testing | Determines if the measurement model is equivalent across instruments or groups | Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis testing configural, metric, and scalar invariance [10] |

| Authenticity Analysis | Quantifies how well harmonized scores approximate original instrument scores | Correlation and difference scores between harmonized and full-item model factor scores [10] |

Methodological Workflows

Harmonization Workflow with Quality Checkpoints

Bifactor Model Structure for Instrument Harmonization

FAQs: Foundational Knowledge

Q1: What is technical variability in neuroimaging, and why is it a problem for reproducibility? Technical variability refers to non-biological differences in brain imaging data introduced by factors like scanner manufacturer, model, software version, imaging site, and data processing methods. Because MRI intensities are acquired in arbitrary units, differences between scanning parameters can often be larger than the biological differences of interest [13]. This variability acts as a significant confound, potentially leading to spurious associations and replication failures in brain-wide association studies (BWAS) [1].

Q2: How does sample size interact with technical variability? Brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals to produce reproducible results because true brain-behaviour associations are typically much smaller than previously assumed (median |r| ≈ 0.01) [1]. Small sample sizes are highly vulnerable to technical confounds and sampling variability, with one study demonstrating that at a sample size of n=25, the 99% confidence interval for univariate associations was r ± 0.52, meaning two independent samples could reach opposite conclusions about the same brain-behaviour association purely by chance [1].

Q3: What are the main sources of technical variability in functional connectomics? A systematic evaluation of 768 fMRI data-processing pipelines revealed that choices in brain parcellation, connectivity definition, and global signal regression create vast differences in network reconstruction [14]. The majority of pipelines failed at least one criterion for reliable network topology, demonstrating that inappropriate pipeline selection can produce systematically misleading results [14].

FAQs: Troubleshooting Technical Variability

Q1: How can I identify suboptimal perfusion MRI (DSC-MRI) data in my experiments? Practical guidance suggests evaluating these key metrics [15]:

- Check contrast agent timing and administration: Ensure proper preload dose (approximately 5-6 minutes before DSC sequence) and bolus injection rate (typically 3-5 mL/s)

- Assess signal quality: Calculate voxel-wise contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR); values less than 4 produce highly unreliable results and can falsely overestimate rCBV

- Verify arterial input function: Visually inspect the DSC signal profile in arterial regions

- Inspect for susceptibility artifacts: Look for signal dropouts in regions near air-tissue interfaces

Q2: What methods can remove technical variability after standard intensity normalization? RAVEL (Removal of Artificial Voxel Effect by Linear regression) is a specialized tool designed to remove residual technical variability after intensity normalization. Inspired by batch effect correction methods in genomics, RAVEL decomposes voxel intensities into biological and unwanted variation components, using control regions (typically cerebrospinal fluid) where intensities are unassociated with disease status [13]. In studies of Alzheimer's disease, RAVEL-corrected intensities showed marked improvement in distinguishing between MCI subjects and healthy controls using mean hippocampal intensity (AUC=67%) compared to intensity normalization alone [13].

Q3: How should I choose a functional connectivity processing pipeline to minimize variability? Based on a systematic evaluation of 768 pipelines, these criteria help identify optimal pipelines [14]:

- Minimize motion confounds and spurious test-retest discrepancies in network topology

- Maintain sensitivity to inter-subject differences and experimental effects

- Demonstrate reliability across different datasets and time intervals (minutes, weeks, months)

- Show generalizability across different acquisition parameters and preprocessing methods

Experimental Protocols for Managing Technical Variability

Protocol 1: RAVEL Implementation for Structural MRI

Purpose: Remove residual technical variability from intensity-normalized T1-weighted images [13]

Materials:

- T1-weighted MRI scans registered to common template

- Control region mask (cerebrospinal fluid)

- Computing environment with singular value decomposition (SVD) capability

Methodology:

- Perform standard intensity normalization (histogram matching or White Stripe)

- Extract voxel intensities from control region (CSF) across all subjects

- Perform singular value decomposition (SVD) of control voxels to estimate unwanted variation factors

- Estimate unwanted factors using linear regression for every brain voxel

- Use residuals from regression as RAVEL-corrected intensities

- Validate using biological positive controls (e.g., hippocampal intensity in AD vs. controls)

Protocol 2: Functional Connectivity Pipeline Validation

Purpose: Identify optimal fMRI processing pipelines that minimize technical variability while preserving biological signal [14]

Materials:

- Resting-state fMRI data with test-retest sessions

- Multiple parcellation schemes (anatomical, functional, multimodal)

- Connectivity metrics (Pearson correlation, mutual information)

- Network filtering approaches (density-based, weight-based, data-driven)

- Portrait divergence (PDiv) measure for network topology comparison

Methodology:

- Preprocessing: Apply standardized denoising (e.g., anatomical CompCor or FIX-ICA)

- Node Definition: Test multiple parcellation types (anatomical, functional, multimodal) and resolutions (100, 200, 300-400 nodes)

- Edge Definition: Calculate functional connectivity using Pearson correlation and mutual information

- Network Filtering: Apply multiple edge retention strategies (fixed density, minimum weight, data-driven)

- Evaluation: Assess each pipeline using multiple criteria:

- Test-retest reliability of network topology

- Sensitivity to individual differences

- Sensitivity to experimental manipulations

- Resistance to motion confounds

- Validation: Verify performance across independent datasets with different acquisition parameters

Table 1: Pipeline Evaluation Criteria for Functional Connectomics

| Criterion | Optimal Performance Characteristic | Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Test-Retest Reliability | Minimal portrait divergence (PDiv) between repeated scans | PDiv < threshold across short (minutes) and long-term (months) intervals |

| Individual Differences Sensitivity | Significant association with behavioral phenotypes | Correlation with cognitive measures or clinical status |

| Experimental Effect Detection | Significant topology changes with experimental manipulation | PDiv between pre/post intervention states |

| Motion Resistance | Low correlation between network metrics and motion parameters | Non-significant correlation with framewise displacement |

| Generalizability | Consistent performance across datasets | Similar reliability in independent cohorts (e.g., HCP, UK Biobank) |

Protocol 3: Quality Assurance for DSC-MRI Perfusion Imaging

Purpose: Identify and troubleshoot suboptimal DSC-MRI data for cerebral blood volume mapping [15]

Materials:

- DSC-MRI sequences (GRE-EPI recommended)

- Gadolinium-based contrast agent with power injector

- Leakage correction software (e.g., delta R2*-based model)

- Signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise calculation tools

Methodology:

- Acquisition Protocol:

- Use gradient-echo EPI sequence with TE ≈ 30ms, TR ≈ 1250ms

- Administer preload contrast dose 5-6 minutes before DSC sequence

- Inject bolus at 3-5 mL/s approximately 60 seconds into acquisition

- Collect 30-50 baseline timepoints before bolus arrival

Quality Assessment:

- Calculate voxel-wise SNR and temporal SNR across the brain

- Compute contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of concentration-time curves

- Flag datasets with CNR < 4 for careful interpretation

- Visually inspect arterial input function (AIF) signal profile

- Verify whole-brain DSC signal time-course characteristics

Post-processing:

- Apply leakage correction for T1 and T2* effects

- Use standardized normalization to white matter reference regions

- Generate relative CBV maps using established algorithms

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common DSC-MRI Issues

| Issue | Indicators | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast Agent Timing | AIF peak misaligned, poor bolus shape | Verify injection timing, use power injector, train staff |

| Low Signal Quality | Low CNR (<4), noisy timecourses | Check coil function, optimize parameters, ensure adequate dose |

| Leakage Effects | rCBV underestimation in enhancing lesions | Apply mathematical leakage correction, use preload dose |

| Susceptibility Artifacts | Signal dropouts near sinuses/ear canals | Adjust positioning, use shimming, consider SE-EPI sequences |

| Inadequate Baseline | Insufficient pre-bolus timepoints | Ensure 30-50 baseline volumes, adjust bolus timing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Managing Technical Variability

| Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| RAVEL Algorithm [13] | Removes residual technical variability after intensity normalization | Multi-site structural MRI studies, disease classification |

| Portrait Divergence (PDiv) [14] | Measures dissimilarity between network topologies across all scales | Pipeline optimization, test-retest reliability assessment |

| Control Regions (CSF) [13] | Provides reference tissue free from biological signal of interest | Estimating unwanted variation factors in RAVEL |

| Consensus DSC-MRI Protocol [15] | Standardized acquisition for perfusion imaging | Multi-site tumor imaging, treatment response monitoring |

| Multiple Parcellation Schemes [14] | Different brain region definitions for network construction | Functional connectomics, individual differences research |

| Standardized Processing Pipelines [16] | Reproducible data processing across datasets | Large-scale consortium studies, open data resources |

| Quality Metrics (SNR, CNR, tSNR) [15] | Quantifies technical data quality | Data quality control, exclusion criteria definition |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Impact

Q1: What is the "motion conundrum" in neuroimaging research? The motion conundrum describes the critical challenge where in-scanner head motion creates data quality artifacts that can be misinterpreted as genuine biological signals. This is particularly problematic in resting-state fMRI (rs‐fMRI) where excluding participants for excessive motion (a standard quality control procedure) can systematically bias the sample, as motion is related to a broad spectrum of participant characteristics such as age, clinical conditions, and demographic factors [17]. Researchers must therefore balance the need for high data quality against the risk of introducing systematic bias through the exclusion of data.

Q2: How can artifacts be mistaken for true brain signatures? Artifacts can mimic or obscure genuine neural activity because they introduce uncontrolled variability into the data [18]. For example:

- Eye blink and movement artifacts produce high-amplitude deflections in frontal electrodes, with spectral power in the delta and theta bands, which can be confused with cognitive processes [18] [19].

- Muscle artifacts generate high-frequency noise that overlaps with the beta and gamma bands, potentially masking signals related to motor activity or cognition [18] [19].

- Cardiac artifacts create rhythmic waveforms that may be mistaken for genuine neural oscillations [18]. This overlap in spectral and temporal characteristics means that without proper correction, analyses may report artifact-driven findings as novel neural phenomena [17] [18].

Q3: Why does this conundrum pose a special threat to reproducible phenotyping? Reproducible brain phenotyping relies on stable, generalizable neural signatures. Motion-related artifacts and the subsequent data exclusion practices threaten this in two key ways:

- Biased Samples: List-wise deletion of participants with high motion creates a sample that is no longer representative of the intended population. Since motion correlates with traits like age, clinical status, and executive functioning, the analyzed sample may systematically differ from the original cohort, leading to biased estimates of brain-behavior relationships [17].

- Inconsistent Signatures: The same phenotype defined in different labs may be based on differently biased samples if QC thresholds are not harmonized. Furthermore, artifacts that vary across sessions or individuals can alter the derived neural signature, reducing its reliability and cross-study validity [17] [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Identifying Common Artifacts

Table 1: Common Physiological and Technical Artifacts

| Artifact Type | Origin | Key Characteristics in Data | Potential Misinterpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Blink/Movement [18] [19] | Corneo-retinal potential from eye movement | High-amplitude, slow deflections; most prominent in frontal electrodes; spectral power in delta/theta bands. | Slow cortical potentials, cognitive processes like attention. |

| Muscle (EMG) [18] [19] | Contraction of head, jaw, or neck muscles | High-frequency, broadband noise; spectral power in beta/gamma ranges. | Enhanced high-frequency oscillatory activity, cognitive or motor signals. |

| Cardiac (ECG/Pulse) [18] [19] | Electrical activity of the heart or pulse-induced movement | Rhythmic, spike-like waveforms recurring at heart rate; often visible in central/temporal electrodes near arteries. | Epileptiform activity, rhythmic neural oscillations. |

| Head Motion [17] [20] | Participant movement in the scanner | Large, non-linear signal shifts; spin-history effects; can affect the entire brain volume. | Altered functional connectivity, group differences correlated with motion-prone populations (e.g., children, clinical groups). |

| Electrode Pop [18] [19] | Sudden change in electrode-skin impedance | Abrupt, high-amplitude transients often isolated to a single channel. | Epileptic spike, a neural response to a stimulus. |

| Line Noise [18] [19] | Electromagnetic interference from AC power | Persistent 50/60 Hz oscillation across all channels. | Pathological high-frequency oscillation. |

Step-by-Step QC and Mitigation Protocol

The following workflow provides a structured approach to managing data quality, from study planning to processing, to minimize the impact of motion and other artifacts.

Phase 1: QC During Study Planning [20]

- Define QC Measures: Identify a priori regions of interest (ROIs) and determine which QC measures (e.g., temporal-signal-to-noise ratio - TSNR) will best support your study's goals.

- Standardize Protocols: Develop clear, written instructions for participants to minimize head motion and for experimenters to ensure consistent procedures across all scanning sessions.

Phase 2: QC During Data Acquisition [20]

- Real-Time Monitoring: Visually inspect incoming data for obvious artifacts, gross head motion, and ensure consistent field of view across scans.

- Behavioral Logs: Meticulously record participant behavior, feedback, and any unexpected events during the scan. This contextual information is crucial for later interpretation.

Phase 3: QC Soon After Acquisition [20]

- Compute Intrinsic Metrics: Calculate basic, intrinsic quality metrics such as Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and TSNR for the entire brain and for your specific ROIs.

- Initial Inspection: Check for accurate functional-to-anatomical alignment and look for obvious spatial and temporal artifacts before proceeding to full analysis.

Phase 4: QC During Data Processing [17] [18] [20]

- Artifact Removal: Employ techniques like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to separate and remove artifact components from EEG data. For fMRI, censoring (scrubbing) of high-motion volumes can be effective, though it may introduce missing data [17] [18].

- Account for Missing Data: When data exclusion is necessary, avoid simple list-wise deletion. Instead, use statistical techniques like multiple imputation to formally account for the missing data and reduce bias, as exclusions are often not random [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Methods for Robust Brain Phenotyping

| Tool/Method | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Imputation [17] | Statistical technique to handle missing data resulting from the exclusion of poor-quality scans, reducing bias. | Preferable to list-wise deletion when data is missing not-at-random (e.g., related to participant traits). |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [18] | A blind source separation method used to isolate and remove artifact components (e.g., eye, muscle) from EEG and fMRI data. | Effective for separating physiological artifacts from neural signals but requires careful component classification. |

| Path Signature Methods [21] | A feature extraction technique for time-series data (e.g., EEG) that is invariant to translation and time reparametrization. | Provides robust features against inter-user variability and noise, useful for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications. |

| Computational Phenotyping Framework [22] | A systematic pipeline for defining and validating disease phenotypes by integrating multiple data sources (EHR, questionnaires, registries). | Enhances reproducibility and generalizability by using multi-layered validation against incidence patterns, risk factors, and genetic correlations. |

| Temporal-Signal-to-Noise Ratio (TSNR) [20] | A key intrinsic QC metric for fMRI that measures the stability of the signal over time. | Lower TSNR in specific ROIs can indicate excessive noise or artifact contamination, flagging potential problems for hypothesis testing. |

Advanced Methodologies & Data Presentation

Quantitative Framework for Motion Bias Assessment

The following table summarizes findings from an investigation into how quality control decisions can systematically bias sample composition in a large-scale study, demonstrating the motion conundrum empirically.

Table 3: Participant Characteristics Associated with Exclusion Due to Motion in the ABCD Study [17]

| Participant Characteristic Category | Specific Example Variables | Impact on Exclusion Odds |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | Lower socioeconomic status, specific race/ethnicity categories | Increased odds of exclusion |

| Health & Physiological Metrics | Higher body mass index (BMI) | Increased odds of exclusion |

| Behavioral & Cognitive Metrics | Lower executive functioning, higher psychopathology | Increased odds of exclusion |

| Environmental & Neighborhood Factors | Area Deprivation Index (ADI), Child Opportunity Index (COI) | Increased odds of exclusion |

Experimental Protocol for Assessing QC-Related Bias:

- Cohort: Utilize a large-scale, deeply phenotyped dataset like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study [17].

- Procedure: Apply a range of realistic QC procedures (e.g., varying motion scrubbing thresholds) to the neuroimaging data to generate different inclusion/exclusion conditions.

- Analysis: For each condition, use statistical models (e.g., logistic regression) to test whether the odds of a participant's exclusion are significantly predicted by a wide array of their baseline characteristics, such as demographic, behavioral, and health-related variables [17].

- Outcome: The demonstration that exclusion is systematically related to participant traits confirms that list-wise deletion introduces bias, arguing for the use of missing data handling techniques in functional connectivity analyses [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Data Sharing Barriers

Problem: A researcher cannot share the underlying data for a manuscript that has been accepted for publication because the process is too time-consuming.

- Possible Cause: The researcher lacks the dedicated time required to curate, annotate, and format the data for public consumption.

- Solution: Integrate data curation tasks into the research team's workflow from the project's outset. Utilize data management plans to predefine formats and metadata schemas, distributing preparation time across the project lifecycle [23].

Problem: A research team is uncertain if they have the legal rights to share their collected data.

- Possible Cause: Unclear data ownership policies within the institution or collaboration, or the use of data subject to third-party licensing agreements.

- Solution: Consult with your institution's legal or technology transfer office before data collection begins. Draft data sharing agreements that explicitly outline rights and responsibilities for all consortium members at the start of a project [23].

Problem: A team lacks the technical knowledge to deposit data into a public repository.

- Possible Cause: Insufficient institutional support or training for data sharing practices.

- Solution: Request tailored training programs from your institution's library or research infrastructure group. Utilize online resources and protocols from established data repositories which often provide step-by-step submission guides [23].

Problem: A researcher believes there is no incentive or cultural support within their team to share data.

- Possible Cause: A perceived lack of professional reward for data sharing and a research culture that does not prioritize open science.

- Solution: Advocate for institutional recognition of data sharing as a valuable scholarly contribution. Cite journal and funder mandates on data sharing to build a case. Start by sharing data within a controlled-access framework if full openness is a concern [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Reproducibility in Brain Phenotype Research

Problem: A brain-wide association study (BWAS) fails to replicate in an independent sample.

- Possible Cause: The study is statistically underpowered due to a small sample size. BWAS effects are typically much smaller (e.g., median |r| ~ 0.01) than previously assumed, requiring thousands of individuals for reproducible results [1].

- Solution: Prioritize large sample sizes, ideally in the thousands. Collaborate with consortia to access larger datasets. Use multivariate methods, which can offer more robust effects than univariate approaches [1].

Problem: A discovered brain signature performs well in the discovery cohort but poorly in a validation cohort.

- Possible Cause: Inflated effect sizes due to sampling variability and model overfitting to the specific discovery sample.

- Solution: Implement a rigorous validation pipeline. Derive consensus signatures using multiple, randomly selected discovery subsets from your data. Validate the final model's fit and explanatory power in completely separate, held-out cohorts [25].

Problem: The brain signature derived from one cognitive domain (e.g., neuropsychological test) does not generalize to another related domain (e.g., everyday memory).

- Possible Cause: The brain substrates for the two domains may not be identical, even if they are strongly shared.

- Solution: Develop and validate separate, data-driven signatures for each specific behavioral domain of interest. Do not assume that a signature for one cognitive measure will perfectly map to another, even if they are conceptually related [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ: What are the most common barriers researchers face when trying to share their data?

Survey data from health and life sciences researchers identifies several prevalent barriers [23]:

- Lack of time to prepare data (reported "usually" or "always" by 34% of researchers).

- Process complexity and the perception that sharing is "too complicated."

- Large dataset management challenges ("too many data files," "difficulty sharing large datasets").

- Unclear rights to share the data (affected 27% of respondents).

- Inadequate infrastructure and technical support (noted by 15%).

- Lack of knowledge on how to share data effectively.

- Absence of cultural incentives ("my team doesn't do it").

FAQ: Why is sample size so critical for reproducible brain-wide association studies?

Brain-behavior associations are often very weak. In large-scale studies, the median correlation between a brain feature and a behavioral phenotype is around |r| = 0.01 [1]. With typical small sample sizes (e.g., n=25), confidence intervals for these correlations are enormous (r ± 0.52), leading to effect size inflation and high replication failure rates. Only with samples in the thousands do these associations begin to stabilize and become reproducible [1].

FAQ: How can we balance ethical data sharing with the needs of open science?

This requires a "balance between ethical and responsible data sharing and open science practices" [24]. Strategies include:

- Using controlled-access repositories where data access is granted to qualified researchers under specific terms.

- Implementing robust de-identification protocols to protect participant privacy.

- Employing data use agreements to ensure responsible reuse.

- Making other research components, like code and analysis workflows, openly available to enhance reproducibility, even when the raw data itself must be protected [24].

FAQ: What is a "brain signature," and how is it different from a standard brain-behavior correlation?

A brain signature is a data-driven, multivariate set of brain regions (e.g., based on gray matter thickness) that, in combination, are most strongly associated with a specific behavioral outcome [25]. Unlike a standard univariate correlation that might link a single brain region to a behavior, a signature uses a statistical model to identify a pattern of regions that collectively account for more variance in the behavior, offering a more complete picture of the brain substrates involved.

FAQ: Our research is innovative, but we fear it will be difficult to get funded through traditional grant channels. Is this a known problem?

Yes. The current peer-review system for grants has been criticized for potentially stifling innovation. There are documented cases where research that later won the Nobel Prize was initially denied funding [26]. Reviewers, who are often competitors of the applicant, may be risk-averse and favor incremental projects with extensive preliminary data over truly novel, exploratory work [26]. This can slow the progress of transformative science.

Data Tables

Table 1: Prevalence of Perceived Data Sharing Barriers Among Researchers

| Barrier | Prevalence ("Usually" or "Always") | Mean Score (0-3 scale) |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of time to prepare data | 34% | 1.19 (Self) / 1.42 (Others) |

| Not having the rights to share data | 27% | Information Missing |

| Process is too complicated | Information Missing | High (Ranked 2nd) |

| Insufficient technical support | 15% | Information Missing |

| Team culture doesn't support it | Information Missing | High (Ranked 2nd for "Others") |

| Managing too many data files | Information Missing | High (Ranked 3rd) |

| Lack of knowledge on how to share | Information Missing | High (Ranked in Top 8) |

Source: Adapted from a survey of 143 Health and Life Sciences researchers [23]. Mean scores are from survey parts where statements were framed personally (Self) and about colleagues (Others).

Table 2: Brain-Wide Association Study (BWAS) Replicability and Sample Size

| Sample Size (n) | Median Effect Size (|r|) | Replication Outlook | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25 (Median of many studies) | Information Missing | Very Low - High sampling variability (99% CI: r ± 0.52) leads to opposite conclusions in different samples. | Studies at this size are statistically underpowered and prone to effect size inflation [1]. |

| n = 3,928 (Large, denoised sample) | 0.01 | Improving - Strongest replicable effects are still small (~|r|=0.16). | Multivariate methods and functional MRI data tend to yield more robust effects than univariate/structural MRI [1]. |

| n = 50,000 (Consortium-level) | Information Missing | High - Associations stabilize and replication rates significantly improve. | Very large samples are necessary to reliably detect the small effects that characterize most brain-behavior relationships [1]. |

Source: Synthesized from analyses of large datasets (ABCD, HCP, UK Biobank) involving up to 50,000 individuals [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating a Robust Brain Signature Phenotype

Aim: To develop and validate a data-driven brain signature for a cognitive domain (e.g., episodic memory) that demonstrates replicability across independent cohorts.

Materials:

- Imaging Data: T1-weighted structural MRI scans from discovery and validation cohorts.

- Behavioral Data: Standardized cognitive test scores for the domain of interest (e.g., memory composite).

- Software: Image processing pipelines (e.g., for gray matter thickness), statistical computing software (e.g., R, Python).

Methodology:

- Discovery Phase:

- Data Processing: Process T1 images to extract whole-brain gray matter thickness maps for each subject in the discovery cohort(s) [25].

- Subset Sampling: Randomly select multiple subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of n=400) from the full discovery cohort to mitigate sampling bias [25].

- Voxel-Wise Regression: In each subset, perform a voxel-wise regression between gray matter thickness at every brain point and the behavioral outcome [25].

- Consensus Mask Creation: Generate spatial overlap frequency maps from all subsets. Define the final "consensus" signature mask by selecting brain regions that are consistently (at a high frequency) associated with the behavior [25].

- Validation Phase:

- Signature Application: Apply the consensus signature mask from the discovery phase to the held-out validation cohort. Calculate a single summary value for each subject in the validation set based on their gray matter thickness within the signature regions [25].

- Model Fit Replicability: Test the association between the signature summary value and the behavioral outcome in the validation cohort. Evaluate the consistency of model fit and its explanatory power (e.g., R²) compared to the discovery phase [25].

- Comparison with Other Models: Compare the signature model's performance against theory-based or lesion-driven models to demonstrate its superior explanatory power [25].

Workflow Diagram: Brain Signature Validation Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Large-Scale Neuroimaging Consortia (e.g., UK Biobank, ADNI, ABCD) | Provides the large sample sizes (n > 10,000) necessary for adequately powered, reproducible Brain-Wide Association Studies (BWAS) [1]. |

| Validated Brain Signatures | Serves as a robust, data-driven phenotypic measure that can be applied across studies to reliably investigate brain substrates of behavior [25]. |

| Data Use Agreements (DUA) | Enables secure and ethical sharing of sensitive human data, balancing open science goals with participant privacy and legal constraints [24]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) & Cloud Resources | Facilitates the computationally intensive processing of large MRI datasets and the running of complex, voxel-wise statistical models [27]. |

| Structured Data Management Plan | Outlines data collection, formatting, and sharing protocols from a project's start, mitigating the time barrier to data sharing later on [23]. |

Building Robust Signatures: Methodological Advances and Practical Applications

Implementing Reproducible Processing Pipelines with C-PAC, FreeSurfer, and DataLad

A technical support guide for overcoming computational pitfalls in neuroimaging research

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers building reproducible processing pipelines with C-PAC, FreeSurfer, and DataLad. These solutions address critical bottlenecks in computational neuroscience and drug development research where reproducible brain signatures are essential.

Troubleshooting Guides

FreeSurfer License Configuration Errors

Problem: Pipeline fails with "FreeSurfer license file not found" error, even when the --fs-license-file path is correct [28].

Diagnosis: The error often occurs within containerized environments (Docker/Singularity) where the license file path inside the container differs from the host path [28].

Solution:

- Set Environment Variable: Export

FS_LICENSEenvironment variable to point to the license file in the container's filesystem - Copy License File: Manually copy the license file to the expected container location (e.g.,

/opt/freesurfer/license.txt) during container execution - Docker Flag Verification: When using

fmriprep-docker, ensure the--fs-license-fileflag properly mounts the license file into the container

Verification Command:

C-PAC and FreeSurfer Pipeline Hanging

Problem: End-to-end surface pipeline with ABCD post-processing stalls during timeseries warp-to-template, particularly when running recon-all and ABCD surface post-processing in the same pipeline [29].

Diagnosis: Resource conflicts between FreeSurfer's recon-all and subsequent ABCD-HCP surface processing stages.

Solutions:

- Preferred Workaround: Run FreeSurfer

recon-allfirst, then ingress its outputs into C-PAC rather than running both simultaneously [29] - Alternative Approach: Cancel the stalled pipeline and restart with warm restart (preserving the Nipype working directory) [29]

- Planned Resolution: Future C-PAC versions will remove integrated

recon-all, requiring FreeSurfer outputs as input for surface analysis configurations [29]

C-PAC BIDS Validator Missing Error

Problem: Pipeline crashes with "bids-validator: command not found" when running C-PAC with input BIDS directory without --skip_bids_validator flag [29].

Solutions:

- Immediate Fix: Add

--skip_bids_validatorflag to your run command (validate BIDS data separately before processing) [29] - Alternative Approach: Use a data configuration file instead of direct BIDS directory input [29]

- Configuration Note: This affects C-PAC versions where bids-validator is missing from the container image [29]

Memory Allocation Failures in C-PAC

Problem: Pipeline crashes with memory errors, particularly when resampling scans to higher resolutions [29].

Diagnosis: Functional images, templates, and resampled outputs are all loaded into memory simultaneously, exceeding available RAM [29].

Memory Estimation Formula:

Example: 100MB uncompressed scan resampled from 3mm to 1mm (27× voxel increase) requires ~2.7GB plus system overhead [29].

Solutions:

- Increase available RAM or reduce parallel subject processing

- Process fewer subjects simultaneously (multiply estimate by number of concurrent subjects) [29]

- Adjust resampling parameters to less memory-intensive methods

DataLad Dataset Nesting Permissions

Problem: DataLad operations fail with permission errors when creating or accessing nested subdatasets [30].

Diagnosis: Python package permission conflicts or incorrect PATH configuration for virtual environments [30].

Solutions:

- Avoid using

sudofor Python package installation [30] - Use

--userflag to install virtualenvwrapper for single-user access [30] - Manually set PATH if

virtualenvwrapper.shisn't found:export PATH="/home/<USER>/.local/bin:$PATH"[30] - For persistent issues, add environment variables to shell configuration file (

~/.bashrc) [30]

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I handle version compatibility between FreeSurfer 8.0.0 and existing pipelines?

FreeSurfer 8.0.0 represents a major release with significant changes including use of SynthSeg, SynthStrip, and SynthMorph deep learning algorithms. While processing time decreases substantially (~2h vs ~8h), note that [31]:

- GPU is not required despite DL modules

- Longitudinal processing has caveats (volumetric segmentation not fully longitudinal)

- Set

FS_ALLOW_DEEP=1environment variable for version 8.0.0-beta - Known issues include csvprint utility failing on systems without Python2

What are the recommended C-PAC commands for different processing scenarios?

Table: Essential C-PAC Run Commands

| Scenario | Command | Key Flags |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration Testing | cpac run <DATA_DIR> <OUTPUT_DIR> test_config |

Generates template pipeline and data configs |

| Single Subject Processing | cpac run <DATA_DIR> <OUTPUT_DIR> participant |

--data_config_file, --pipeline_file |

| Group Level Analysis | cpac run <DATA_DIR> <OUTPUT_DIR> group |

--group_file, --data_config_file |

| Sample Data Test | cpac run cpac_sample_data output participant |

--data_config_file, --pipeline_file |

How can I inspect C-PAC crash files for debugging?

- C-PAC ≥1.8.0: Crash files are plain text—view with any text editor [29]

- C-PAC ≤1.7.2: Use

cpac crash /path/to/crash-file.pklzor enter container and usenipypecli crash crash-file.pklz[29]

What are the key differences in anatomical atlas paths between Neuroparc v0 and v1?

Several atlas paths changed in Neuroparc v1.0 (July 2020). Pipelines based on C-PAC 1.6.2a or older require configuration updates [29]:

Table: Neuroparc Atlas Path Changes

| Neuroparc v0 | Neuroparc v1 |

|---|---|

aal_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

AAL_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

brodmann_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

Brodmann_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

desikan_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

Desikan_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

schaefer2018-200-node_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

Schaefer200_space-MNI152NLin6_res-1x1x1.nii.gz |

How does fMRIPrep 25.0.0 improve pre-computed derivative handling?

fMRIPrep 25.0.0 (March 2025) substantially improves support for pre-computed derivatives with the recommended command [32]:

Multiple derivatives can be specified (e.g., anat=PRECOMPUTED_ANATOMICAL_DIR func=PRECOMPUTED_FUNCTIONAL_DIR), with last-found files taking precedence [32].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Multi-Software Validation for Skull-Stripping

Purpose: Assess analytical flexibility by comparing brain extraction results across multiple tools [33].

Methodology:

- Dataset: Use standardized test dataset (ds005072 from OpenNeuro) [33]

- Tools: Apply at least two distinct skull-stripping tools (e.g., AFNI, FSL, SPM)

- Evaluation: Quantitative comparison of extracted brain volumes and spatial overlap

- Implementation: Containerize each tool to ensure version consistency [33]

Interpretation: Measure result variability attributable to tool selection rather than biological factors [33].

Protocol 2: Numerical Stability Assessment

Purpose: Evaluate pipeline robustness to computational environment variations [33].

Methodology:

- Operation Selection: Focus on mathematically complex operations (e.g., FreeSurfer skull-stripping) [33]

- Environment Variation: Execute identical pipeline across different OS, compiler versions, and libraries

- Output Comparison: Quantify floating-point differences in resulting files

- Pertubation Modeling: Systematically introduce numerical variations to assess stability [33]

Significance: Determines whether environmental differences meaningfully impact analytical results [33].

Workflow Diagrams

Troubleshooting Logic for Pipeline Failures

DataLad Dataset Nesting Structure

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Category | Specific Implementation | Function in Reproducible Research |

|---|---|---|

| Containerization | Docker, Singularity | Environment consistency across computational platforms [33] |

| Workflow Engines | Nipype, Nextflow | Organize and re-execute analytical computation sequences [33] |

| Data Management | DataLad, Git-annex | Version control and provenance tracking for large datasets [34] |

| Pipeline Platforms | C-PAC, fMRIPrep | Standardized preprocessing with reduced configuration burden [33] |

| Provenance Tracking | BIDS-URIs, DatasetLinks | Machine-readable tracking of data transformations [32] |

| Numerical Stability | Verificarlo, Precise | Assess impact of floating-point variations on results [33] |

In the quest to identify reproducible brain signatures of psychiatric conditions, a significant obstacle arises from the use of different assessment instruments across research datasets. Data harmonization—the process of integrating data from distinct measurement tools—is essential for advancing reproducible psychiatric research [10]. The bifactor model has emerged as a powerful statistical framework for this purpose, as it can parse psychopathology into a general factor (often called the p-factor) that captures shared variance across all symptoms, and specific factors that represent unique variances of symptom clusters [35]. This technical support guide provides practical solutions for implementing bifactor models to create harmonized psychiatric phenotypes, directly addressing key methodological challenges in reproducible brain signature research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of using bifactor models for data harmonization?

Bifactor models provide a principled approach to harmonizing different psychopathology instruments by separating what is general from what is specific in mental health problems. This separation allows researchers to:

- Extract a transdiagnostic p-factor that represents shared liability to psychopathology across different instruments [35]

- Obtain specific factors (e.g., internalizing, externalizing) that capture unique variance beyond the general factor [10]

- Account for measurement differences between instruments while isolating substantive constructs of interest

- Enable more precise mapping of brain-behavior relationships by distinguishing shared from unique psychopathological dimensions

Q2: How do I select appropriate indicators for a harmonized bifactor model?

Indicator selection requires careful consideration of both theoretical and empirical factors:

- Perform semantic matching: Identify items from different instruments that measure similar constructs based on content [10]

- Balance comprehensiveness and parsimony: Models with 39-116 items have been successfully implemented, suggesting flexibility in indicator selection [35]

- Ensure content coverage: Select items that adequately represent both the general factor and the specific domains of interest

- Test multiple configurations: Empirical evidence suggests that different bifactor models using varying items often yield highly correlated p-factors (r = 0.88-0.99), providing some flexibility in indicator selection [35]

Q3: What are the key reliability indices I should report for my bifactor model?

When evaluating and reporting bifactor models, several reliability indices are essential:

Table: Key Reliability Indices for Bifactor Models

| Index Name | Purpose | Acceptable Threshold | Common Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Determinacy | Assesses how well factor scores represent the latent construct | >0.90 for precise individual scores | Generally acceptable for p-factors, internalizing, externalizing, and somatic factors [35] |

| H Index | Measures how well a factor is defined by its indicators | >0.70 considered acceptable | Typically adequate for p-factors but variable for specific factors [35] |

| Omega Hierarchical (ωH) | Proportion of total score variance attributable to the general factor | >0.70 suggests strong general factor | Varies by model specification and instrument |

| Omega Subscale (ωS) | Proportion of subscale score variance attributable to specific factor after accounting for general factor | No universal threshold; higher values indicate more reliable specific factors | Often lower than ωH, indicating specific factors may capture less reliable variance |

Q4: How can I assess whether my harmonized model is successful?

Successful harmonization requires evidence from multiple assessment strategies:

- Model fit indices: Acceptable global model fit (e.g., CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08) [10]

- Measurement invariance: Test whether the factor structure holds across different instruments, demographics, and clinical characteristics [35]

- Authenticity assessment: Calculate correlations between factor scores from harmonized (limited item) models and original (full item) models [10]

- Criterion validity: Examine whether factors predict relevant external variables (e.g., daily life functioning, treatment response)

Q5: What are the most common specific factors that demonstrate adequate reliability?

Research using the Child Behavior Checklist has identified several specific factors that consistently show adequate reliability in bifactor models:

Table: Reliability Patterns of Specific Factors in Bifactor Models

| Specific Factor | Reliability Profile | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Internalizing | Generally acceptable reliability in most models [35] | Captures distress-based disorders (anxiety, depression) |

| Externalizing | Generally acceptable reliability in most models [35] | Captures behavioral regulation problems (ADHD, conduct problems) |

| Somatic | Generally acceptable reliability in most models [35] | Reflects physical complaints without clear medical cause |

| Attention | Consistently predicts symptom impact in daily life [35] | Particularly relevant for ADHD and cognitive dysfunction |

| Thought Problems | Variable reliability across studies | May relate to psychotic-like experiences |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Factor Determinacy for Specific Factors

Symptoms:

- Specific factor scores correlate weakly with theoretical constructs they purport to measure

- Low H indices for specific factors (<0.70)

- Specific factors fail to predict relevant external criteria

Solutions:

- Review indicator selection: Ensure adequate number of strong indicators for each specific factor

- Check factor intercorrelations: If specific factors are highly correlated, consider whether a different model structure might be more appropriate

- Assess instrument limitations: Some instruments may not provide adequate coverage of specific domains—consider supplementing with additional measures

- Report transparency: Clearly communicate limitations of specific factors with low determinacy and interpret findings cautiously

Problem: Measurement Non-Invariance Across Instruments

Symptoms:

- Significant deterioration in model fit when constraining factor loadings across instruments

- Different factor structures emerge for different assessment tools

- Meaningful differences in factor scores attributable to instrument rather than underlying construct

Solutions:

- Test for partial invariance: Identify which specific items show non-invariance and consider whether they can be excluded without compromising content validity [10]

- Use alignment optimization: Modern methods can estimate approximate invariance even when exact invariance doesn't hold

- Apply instrument correction: Include method factors to account for systematic variance associated with particular instruments

- Report differential functioning: Clearly document any instrument-related differences and consider them in interpretation

Problem: Low Authenticity Between Harmonized and Original Models

Symptoms:

- Low correlations (<0.70) between factor scores from harmonized models and original full-item models

- Large differences (>0.5 z-score) in factor scores between harmonized and original models for substantial portions of participants (e.g., >20%)

Solutions:

- Optimize item selection: Focus on items with strongest loadings in original models when creating harmonized versions [10]

- Assess impact strategically: Research shows p-factors typically show high authenticity (>0.89), while specific factors show more variable authenticity (0.12-0.81)—prioritize accordingly based on research questions [10]

- Consider sample-specific calibration: When possible, collect supplemental data to establish crosswalk between harmonized and original scores

- Acknowledge limitations: Be transparent about the trade-offs between harmonization breadth and measurement precision

Problem: Inconsistent Associations with External Validators

Symptoms:

- Bifactor dimensions fail to predict expected external criteria (e.g., neurocognitive performance, real-world functioning)

- Discrepant patterns of association across studies or samples

Solutions:

- Verify reliability first: Ensure factors have adequate reliability before interpreting validity coefficients

- Consider hierarchical specificity: Recognize that only some specific factors (particularly attention) consistently predict daily life impact beyond the p-factor [35]

- Use appropriate statistical controls: When examining specific factors, always control for the general factor to isolate unique variance

- Test multiple external validators: Include a range of criteria to comprehensively assess construct validity

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bifactor Model Specification and Testing

Purpose: To establish an appropriate bifactor model for data harmonization

Workflow:

Procedural Details:

- Item harmonization: Identify semantically similar items across instruments through expert consensus and literature review [10]

- Model specification: Define a general factor (all items load) and specific factors (theoretically coherent item subsets)

- Model estimation: Use robust estimation methods appropriate for ordinal data (e.g., WLSMV or MLR estimators)

- Fit assessment: Evaluate multiple indices: CFI (>0.90), TLI (>0.90), RMSEA (<0.08), SRMR (<0.08)

- Reliability calculation: Compute factor determinacy, H index, omega hierarchical, and omega subscale

- Invariance testing: Test configural, metric, and scalar invariance across instruments and demographic groups

- Validation: Examine associations with relevant external variables (e.g., functional impairment, treatment response)

Protocol 2: Authenticity Assessment of Harmonized Measures

Purpose: To evaluate how well harmonized models reproduce results from original full-item models

Procedural Details:

- Estimate original models: Fit established bifactor models using complete item sets for each instrument

- Estimate harmonized models: Fit bifactor models using only the harmonized item subset

- Calculate factor scores: Extract factor scores from both original and harmonized models

- Assess correlation: Compute correlations between factor scores from original and harmonized models

- Compute difference scores: Calculate absolute differences between original and harmonized factor scores

- Flag cases with differences >0.5 z-score for further inspection [10]

- Interpret impact: Consider whether observed differences meaningfully affect substantive conclusions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Methodological Tools for Bifactor Harmonization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Mplus, R (lavaan package), OpenMx | Model estimation and fit assessment |

| Reliability Calculators | Omega, Factor Determinacy scripts | Quantifying measurement precision |

| Invariance Testing Protocols | SEM Tools R package, Mplus MODEL TEST | Establishing measurement equivalence |

| Data Harmonization Platforms | Reproducible Brain Charts (RBC) initiative | Cross-study data integration infrastructure [10] [35] |

| Psychopathology Instruments | Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), GOASSESS | Source instruments for symptom assessment [10] |

Advanced Applications in Reproducible Brain Research

Implementing robust bifactor models for psychiatric phenotyping creates crucial foundations for reproducible brain signature research. By establishing harmonized phenotypes with known reliability and validity, researchers can more effectively:

- Identify neural correlates of general versus specific psychopathology dimensions

- Distinguish shared from unique brain-behavior relationships

- Enhance reproducibility by creating standardized phenotypic measures across studies

- Facilitate large-scale consortia efforts by enabling data integration across different assessment protocols

The methodologies outlined in this guide provide essential tools for overcoming the phenotypic harmonization challenges that often undermine reproducibility in neuropsychiatric research [36].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges in reproducible brain-signature phenotype research, providing practical solutions grounded in recent methodological advances.

General Predictive Modeling

Q: Why does my predictive model perform well in cross-validation but fail on a separate, held-out dataset?

A: This is a classic sign of overfitting, where a model learns patterns specific to your training sample that do not generalize. A study of 250 neuroimaging papers found that performance on a true holdout ("lockbox") dataset was, on average, 13% less accurate than performance estimated through cross-validation alone [37].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement a Strict Lockbox Method: From the outset, partition your data into a training set and a completely held-out test set. The test set should be touched only once for the final model evaluation [37].

- Increase Sample Size: Brain-wide association studies (BWAS) require large samples to produce reproducible effects. Models trained on small samples (e.g., n=25) are highly susceptible to effect size inflation and failure to replicate. Samples in the thousands are often necessary for robust results [1].

- Simplify Your Model: Use regularization techniques (e.g., Lasso, Ridge) or feature selection to enforce model parsimony and reduce complexity [37].

Q: What is the difference between a correlation and a true prediction in the context of brain-behavior research?

A: Many studies loosely use "predicts" as a synonym for "correlates with." However, a true prediction uses a model trained on one dataset to generate outcomes in a novel, independent dataset. Correlation models often overfit the data and fail to generalize. Using cross-validation is a key methodological step that transforms a correlational finding into a generalizable predictive model [38].

Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling (CPM)

Q: My CPM model has low predictive power. What are potential sources of this issue and how can I address them?

A: Low predictive power can stem from several sources, including the choice of functional connectivity features, prediction algorithms, and data quality.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Compare Connectivity Measures: While Pearson's correlation is the most common metric, consider testing other features like accordance (for in-phase synchronization) and discordance (for out-of-phase anti-correlation). These may capture different, behaviorally relevant neural signals [39].

- Try Different Algorithms: The standard linear regression in CPM can be compared against other methods like Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression. Evidence suggests PLS regression can sometimes offer a numerical improvement in prediction accuracy, particularly for resting-state data [39].

- Validate Externally: Always test your model on at least one completely independent dataset. Internal validation (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) is necessary but not sufficient to prove that a model generalizes across different populations and scanning sites [39].

Q: What are the detailed steps for implementing a Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling (CPM) protocol?

A: The CPM protocol is a data-driven method for building predictive models of brain-behavior relationships from connectivity data. The workflow involves the following key steps [38]:

Table: CPM Protocol Steps

| Step | Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Feature Selection | Identify brain connections (edges) that are significantly correlated with the behavioral measure of interest across subjects in the training set. | Use a univariate correlation threshold (e.g., p < 0.01) to select positively and negatively correlated edges. [38] [39] |