Spatial and Temporal Resolution in Neuroimaging: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of spatial and temporal resolution in neuroimaging, addressing the critical trade-offs that impact research and drug development.

Spatial and Temporal Resolution in Neuroimaging: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of spatial and temporal resolution in neuroimaging, addressing the critical trade-offs that impact research and drug development. It covers foundational principles of key technologies—including fMRI, EEG, MEG, PET, and emerging tools like spatial transcriptomics. The content delves into methodological applications for studying brain function and drug effects, offers strategies for optimizing study design and cost-effectiveness, and discusses validation frameworks through multi-modal integration and comparative analysis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current evidence to inform robust experimental design and interpretation of neuroimaging data.

The Fundamental Trade-Off: Defining Spatial and Temporal Resolution in Brain Imaging

Spatial resolution represents a fundamental metric in functional neuroimaging, defining the ability to precisely localize neural activity within the brain. This technical guide examines the biological and physical principles governing spatial resolution across major neuroimaging modalities, from the macroscopic scale of clinical imaging to the mesoscopic scale of advanced research techniques. We explore the inherent trade-offs between spatial and temporal resolution, detailing how innovations in hardware, signal processing, and multimodal integration are pushing the boundaries of localization precision. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles is critical for selecting appropriate methodologies, interpreting neural activation maps, and validating biomarkers in both basic research and clinical trials. This review synthesizes current technical capabilities and experimental protocols to provide a framework for optimizing spatial precision in neuroimaging study design.

Spatial resolution in neuroimaging is formally defined as the ability to distinguish between two distinct points or separate functional regions within the brain. This metric determines the smallest detectable feature in an image and is typically measured in millimeters (mm) or, in advanced systems, sub-millimeters. High spatial resolution allows researchers to pinpoint neural activity to specific cortical layers, columns, or nuclei, which is essential for understanding brain organization and developing targeted neurological therapies. Spatial resolution stands in direct trade-off with temporal resolution—the ability to track neural dynamics over time. While some techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) offer millisecond temporal precision, they suffer from limited spatial resolution due to the inverse problem, where infinite source configurations can explain a given scalp potential distribution [1].

The biological basis of spatial resolution lies in the neural substrates being measured. Direct measures of electrophysiological activity, including action potentials and postsynaptic potentials, occur on spatial scales of micrometers and milliseconds. However, non-invasive techniques typically measure surrogate signals. The blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal used in functional MRI (fMRI), for instance, reflects hemodynamic changes coupled to neural activity through neurovascular coupling. This vascular response occurs over larger spatial scales than the underlying neural activity, fundamentally limiting resolution. Advanced techniques targeting cortical layers and columns must overcome these biological constraints through sophisticated modeling and high-field imaging [2] [3].

For drug development professionals, spatial resolution has profound implications. Target engagement studies require precise localization of drug effects, while biomarker validation depends on reproducible activation patterns in specific circuits. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of different imaging modalities ensures appropriate methodology selection for preclinical and clinical trials.

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities

The spatial resolution of a neuroimaging technique is determined by its underlying physical principles, sensor technology, and reconstruction algorithms. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of major modalities:

Table 1: Spatial and Temporal Resolution Characteristics of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Basis of Signal | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | 1-3 mm (3T); <1 mm (7T) [4] | 1-4 seconds [3] | Hemodynamic (BOLD) response | Excellent whole-brain coverage; high spatial resolution | Indirect measure; slow hemodynamic response |

| PET | 3-5 mm (clinical); ~1 mm (NeuroEXPLORER) [5] | Minutes [3] | Radioactive tracer distribution | Molecular specificity; quantitative | Ionizing radiation; poor temporal resolution |

| EEG | 10-20 mm [3] | <1 millisecond [3] | Electrical potentials at scalp | Direct neural measure; excellent temporal resolution | Poor spatial localization; inverse problem |

| MEG | 3-5 mm [2] [3] | <1 millisecond [3] | Magnetic fields from neural currents | Excellent temporal resolution; good spatial resolution | Expensive; signal strength decreases with distance |

| ECoG | 1-10 mm | <1 millisecond | Direct cortical electrical activity | High signal quality; excellent resolution | Invasive (requires craniotomy) |

| OPM-MEG | <5 mm [2] | <1 millisecond [2] | Magnetic fields (new sensor technology) | Flexible sensor placement; high sensitivity | Emerging technology; limited availability |

The progression toward higher spatial resolution involves both technological innovations and methodological refinements. 7 Tesla MRI systems now enable sub-millimeter resolution, allowing investigation of cortical layer function [4]. Next-generation PET systems like the NeuroEXPLORER achieve unprecedented ~1 mm spatial resolution through improved detector design and depth-of-interaction measurement, enhancing quantification of radioligand binding in small brain structures [5].

Table 2: Technical Factors Governing Spatial Resolution by Modality

| Modality | Primary Resolution Determinants | Typical Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Magnetic field strength, gradient performance, reconstruction algorithms, voxel size | Localizing cognitive functions, mapping functional networks, clinical preoperative mapping |

| PET | Detector crystal size, photon detection efficiency, time-of-flight capability, reconstruction methods | Receptor localization, metabolic activity measurement, drug target engagement |

| EEG/MEG | Number and density of sensors, head model accuracy, source reconstruction algorithms | Studying neural dynamics, epilepsy focus localization, sleep studies |

| Advanced MEG | Sensor type (SQUID vs. OPM), distance from scalp, magnetic shielding [2] | Developmental neuroimaging, presurgical mapping, cognitive neuroscience |

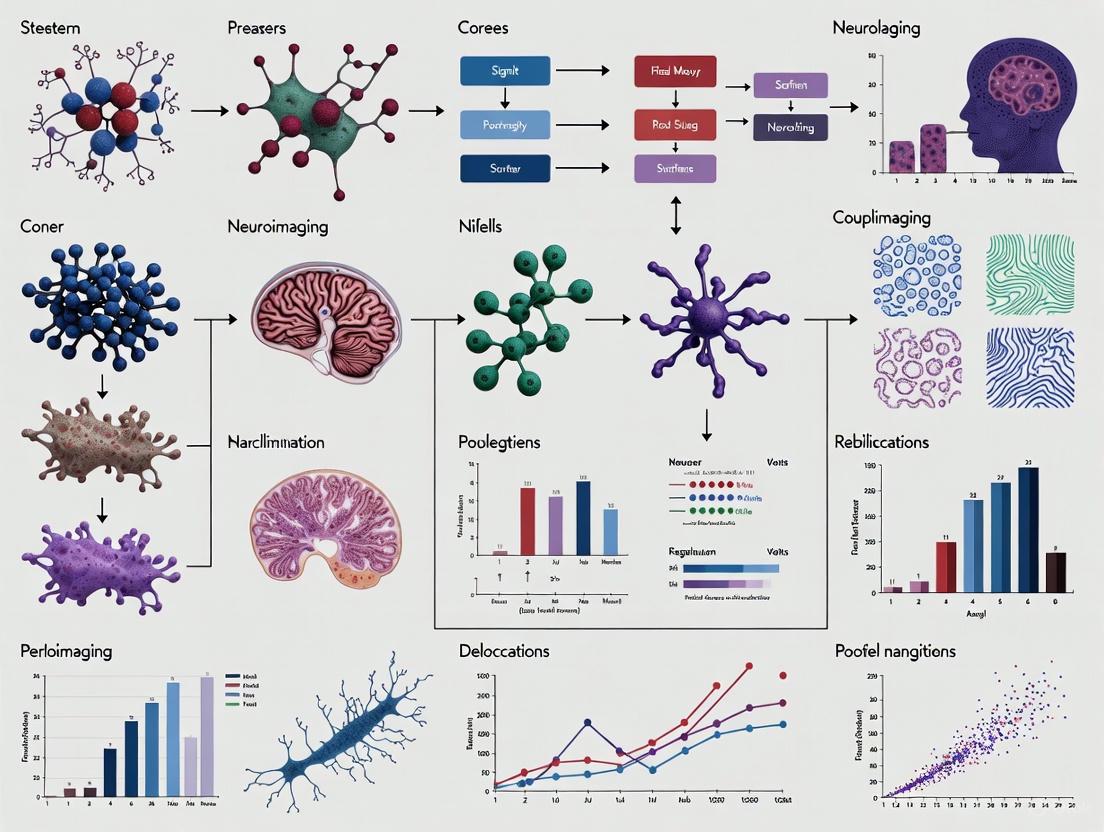

Figure 1: Fundamental factors determining spatial resolution in neuroimaging. The physical principles of each modality create fundamental constraints, while technical implementation determines achievable resolution within those bounds.

Biological and Physical Foundations

The ultimate limit of spatial resolution in neuroimaging is governed by both the biological processes being measured and the physical principles of the detection technology. At the biological level, the neuron represents the fundamental functional unit, with typical cell body diameters of 10-30 micrometers. However, non-invasive techniques rarely measure individual neuron activity directly, instead detecting population signals that impose fundamental limits on spatial precision.

For hemodynamic-based techniques like fMRI, the spatial specificity is constrained by the vascular architecture of the brain. The BOLD signal primarily reflects changes in deoxygenated hemoglobin in venous vessels, with the spatial extent of the hemodynamic response typically spanning several millimeters. Advanced high-field MRI (7T and above) can discriminate signals across different cortical layers by exploiting variations in vascular density and structure at this mesoscopic scale. Recent studies at 7T have successfully differentiated activity in the line of Gennari in the primary visual cortex, a layer-specific structure high in both iron and myelin content [4].

The Biot-Savart law of electromagnetism fundamentally governs MEG and EEG spatial resolution. This physical principle states that magnetic field strength decreases with the square of the distance from the current source. Consequently, MEG systems achieve superior spatial resolution to EEG because magnetic fields are less distorted by intervening tissues than electrical signals. The development of on-scalp magnetometers (OPM-MEG) dramatically improves spatial resolution by reducing the sensor-to-cortex distance to approximately 5 mm compared to 50 mm in conventional SQUID-MEG systems [2]. This proximity enhances signal strength and source localization precision.

For molecular imaging with PET, spatial resolution is primarily limited by physical factors including positron range (the distance a positron travels before annihilation) and non-collinearity of the annihilation photons. The NeuroEXPLORER scanner addresses these limitations through specialized detector design featuring 3.6 mm depth-of-interaction resolution and 236 ps time-of-flight resolution, enabling unprecedented ~1 mm spatial resolution for brain imaging [5].

Methodologies for High-Resolution Imaging

Ultra-High Field MRI Protocols

Achieving sub-millimeter spatial resolution with fMRI requires specialized acquisition and processing protocols. A representative high-resolution study at 7T employed the following methodology [4]:

- Imaging Parameters: Acquired T2*-weighted data with spatial resolution of 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.4 mm³ using a 7T scanner with a 64-channel head-neck coil.

- Motion Correction: Implemented combined correction for motion and B0 field changes using volumetric navigators to improve test-retest reliability.

- Quantitative Mapping: Derived R2* (effective transverse relaxation rate) and magnetic susceptibility (χ) maps from multi-echo data to infer iron and myelin distributions across cortical depths.

- Orientation Analysis: Accounted for significant effects of cortical orientation relative to the main magnetic field (B0), particularly for susceptibility quantification.

This protocol demonstrated that distinguishing different cortical depth regions based on R2* or χ contrast remains feasible up to isotropic 0.5 mm resolution, enabling layer-specific functional imaging.

Advanced MEG Source Imaging

OPM-MEG represents a significant advancement in electromagnetic source imaging. A controlled comparison study utilized this experimental design [2]:

- Sensor Configuration: Compared conventional SQUID-MEG sensors (~50 mm from scalp) with OPM-MEG sensors positioned directly on the scalp surface (~5 mm distance).

- Experimental Paradigm: Employed visual stimulation with two protocols: (1) flash stimuli (FS) consisting of 80 ms white flashes, and (2) pattern reversal (PR) with black-and-white checkerboard reversals at 500 ms intervals.

- Source Reconstruction: Used individual structural MRI to create subject-specific head models for precise source localization.

- Validation Metrics: Quantified spatio-temporal accuracy by comparing measured visually evoked fields (VEFs) to established characteristic brain signatures.

Results demonstrated OPM-MEG's superior signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution, confirming its enhanced capability for tracking cortical dynamics and identifying biomarkers for neurological disorders.

Multimodal Integration

Deep learning approaches now enable fusion of complementary imaging data. A transformer-based encoding model integrated MEG and fMRI through this workflow [6]:

- Stimulus Representation: Combined three feature streams: 768-dimensional GPT-2 embeddings, 44-dimensional phoneme features, and 40-dimensional mel-spectrograms.

- Architecture: Employed a transformer encoder with causal sliding window attention to model temporal dependencies in neural responses.

- Source Estimation: Projected transformer outputs to a cortical source space with 8,196 locations, then morphed to individual subjects using anatomical constraints.

- Forward Modeling: Generated MEG and fMRI predictions via biophysical forward models, ensuring consistency between modalities.

This approach demonstrated improved spatial and temporal fidelity compared to single-modality methods or traditional minimum-norm estimation, particularly for naturalistic stimulus paradigms like narrative story comprehension.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for high-resolution neuroimaging. The pathway shows common steps across modalities, with specialized procedures for different techniques and enhancement strategies for maximizing spatial resolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for High-Resolution Neuroimaging

| Reagent/Equipment | Technical Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 7T MRI Scanner with 64+ Channel Coil | Provides high signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution for sub-millimeter imaging | Cortical layer fMRI, microstructural mapping, high-resolution connectivity |

| OPM-MEG Sensors | On-scalp magnetometers measuring femtotesla-range magnetic fields with minimal sensor-to-cortex distance | High-resolution source imaging in naturalistic paradigms, pediatric neuroimaging |

| NeuroEXPLORER PET System | Dedicated brain PET with 495 mm axial FOV, 3.6 mm DOI resolution for ~1 mm spatial resolution | Quantitative molecular imaging, receptor mapping, pharmacokinetic studies |

| Cortical Surface Analysis Software | Reconstruction of cortical surfaces from structural MRI for anatomically constrained source modeling | Surface-based analysis, cortical depth sampling, cross-subject alignment |

| Multi-Echo T2* MRI Sequence | Quantification of R2* relaxation parameters sensitive to iron and myelin content | Tissue characterization, cortical depth analysis, biomarker development |

| Biomagnetic Shielding | Magnetically shielded rooms (MSRs) reducing environmental noise for sensitive magnetic field measurements | MEG studies requiring femtotesla sensitivity, urban environments |

| Depth-of-Interaction PET Detectors | Crystal-photodetector arrays measuring interaction position along gamma ray path | Improved spatial resolution uniformity, reduced parallax error in PET |

| Transformer-Based Encoding Models | Deep learning architectures integrating multimodal neuroimaging data with naturalistic stimuli | Multimodal fusion, naturalistic neuroscience, stimulus-feature mapping |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The progressive improvement in spatial resolution directly impacts both basic neuroscience and pharmaceutical development. For target validation, the ability to localize drug effects to specific circuits or even cortical layers strengthens mechanistic hypotheses. The emergence of quantitative MRI biomarkers sensitive to myelin, iron, and cellular density at sub-millimeter resolution provides new endpoints for clinical trials in neurodegenerative diseases [7].

In pharmacology, high-resolution PET enables precise quantification of target engagement for drugs acting on specific neurotransmitter systems. The NeuroEXPLORER system demonstrates negligible quantitative bias across a wide activity range (1-558 MBq), supporting reliable kinetic modeling even with low injected doses [5]. This precision is crucial for dose-finding studies and confirming brain penetration.

For clinical applications, improved spatial resolution enhances presurgical mapping, with OPM-MEG providing superior localization of epileptic foci and eloquent cortex [2]. In drug development, these applications can improve patient stratification by identifying circuit-specific biomarkers of treatment response.

The integration of multiple imaging modalities through computational approaches represents the future of high-resolution neuroimaging. As demonstrated by MEG-fMRI fusion models, combining millisecond temporal resolution with millimeter spatial resolution provides a more complete picture of brain dynamics, enabling researchers to track the rapid propagation of neural activity through precisely localized circuits [6].

Spatial resolution remains a central consideration in neuroimaging study design, with technical innovations continuously pushing the boundaries of localization precision. From ultra-high field MRI to on-scalp MEG and next-generation PET, each modality offers distinct advantages for specific research questions. Understanding the biological foundations, technical constraints, and methodological requirements for high-resolution imaging empowers researchers to select optimal approaches for their scientific and clinical objectives. As multimodal integration and computational modeling advance, the field moves closer to non-invasive characterization of neural activity at the mesoscopic scale, promising new insights into brain function and more targeted therapeutic interventions.

In the field of neuroimaging, temporal resolution is a critical technical parameter that refers to the precision with which a measurement tool can track changes in brain activity over time. In essence, it defines the ability to distinguish between two distinct neural events occurring in rapid succession. For cognitive neuroscientists and researchers investigating fast-paced processes like perception, attention, and decision-making, high temporal resolution is indispensable for accurately capturing the brain's dynamic operations. This metric is often measured in milliseconds (ms) for direct neural recording techniques, reflecting the breathtaking speed at which neuronal networks communicate [8] [2].

The importance of temporal resolution cannot be overstated, as it fundamentally determines the kinds of neuroscientific questions a researcher can explore. Techniques with millisecond precision can resolve the sequence of activations across different brain regions during a cognitive task, revealing the flow of information processing. However, a persistent challenge in neuroimaging is the inherent trade-off between temporal and spatial resolution. Methods that excel at pinpointing when neural activity occurs (high temporal resolution) often struggle to precisely identify where in the brain it is happening (spatial resolution), and vice versa. Navigating this trade-off is a central consideration in designing neuroimaging studies [8] [2].

This guide provides an in-depth examination of temporal resolution within the broader context of spatiotemporal dynamics in neuroimaging research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the technical principles, compares leading methodologies, outlines experimental protocols for cutting-edge techniques, and explores how advances in resolution are driving new discoveries in neuroscience and therapeutic development.

Core Principles and Biological Basis

At its core, the quest for high temporal resolution in neuroimaging is a quest to measure neuronal activity as directly and quickly as possible. Neuronal communication, involving action potentials and postsynaptic potentials, occurs on a timescale of milliseconds. Therefore, the ideal measurement would capture these events with millisecond precision. The biological signals that neuroimaging techniques exploit fall into two main categories: neuroelectrical potentials and the hemodynamic response [3] [2].

Direct Measures of Electrical and Magnetic Activity: Techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) belong to this category. EEG measures the electrical potentials generated by synchronized neuronal firing through electrodes placed on the scalp. MEG, conversely, detects the minuscule magnetic fields produced by these same intracellular electrical currents. Since these techniques pick up the electromagnetic signals that are a direct and immediate consequence of neuronal firing, they offer excellent temporal resolution, capable of tracking changes in brain activity in real-time, often with sub-millisecond precision [3] [2].

Indirect Measures via the Hemodynamic Response: Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) is the most prominent technique in this group. It does not measure neural activity directly but instead infers it from changes in local blood flow, blood volume, and blood oxygenation—a complex cascade known as the hemodynamic response. When a brain region becomes active, it triggers a local increase in blood flow that delivers oxygen. The Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal, which is the primary contrast mechanism for fMRI, detects the magnetic differences between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin. While this vascular response is coupled to neural activity, it is inherently slow and sluggish, unfolding over several seconds [3] [9] [2]. This fundamental biological delay is the primary reason why conventional fMRI has a lower temporal resolution compared to EEG and MEG.

Recent research has begun to challenge the classical view of the hemodynamic response. While the peak of the BOLD response still occurs 5-6 seconds after neural activity, studies using fast fMRI acquisition protocols have detected high-frequency content in the signal, suggesting that it may contain information about neural dynamics unfolding at a much faster timescale, potentially as quick as hundreds of milliseconds. This has prompted the development of updated biophysical models to better understand and leverage the temporal information in fMRI [9].

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Techniques

Different neuroimaging modalities offer a wide spectrum of temporal and spatial resolution capabilities, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The choice of technique is therefore dictated by the specific research question, balancing the need to know "when" with the need to know "where."

Table 1: Comparison of Key Neuroimaging Techniques

| Technique | Measure of Neuronal Activity | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Principles and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG (Electroencephalography) | Direct (Neuroelectrical potentials) | Excellent (< 1 ms) [3] | Reasonable/Good (~10 mm) [3] | Measures electrical activity from scalp. Ideal for studying rapid cognitive processes (e.g., ERP studies), sleep stages, and epilepsy [3] [8]. |

| MEG (Magnetoencephalography) | Direct (Neuromagnetic field) | Excellent (< 1 ms) [3] | Good/Excellent (~5 mm) [3] | Measures magnetic fields induced by electrical currents. Combines high temporal resolution with better spatial localization than EEG. Used in pre-surgical brain mapping and cognitive neuroscience [2]. |

| fMRI (functional MRI) | Indirect (Hemodynamic response) | Reasonable (~4-5 s) [3] | Excellent (~2 mm) [3] | Measures BOLD signal. Provides detailed images of brain structure and function. Dominant in systems and cognitive neuroscience for localizing brain functions [3] [8] [9]. |

| PET (Positron Emission Tomography) | Indirect (Hemodynamic response / Metabolism) | Poor (~1-2 min) [3] | Good/Excellent (~4 mm) [3] | Uses radioactive tracers to measure metabolism or blood flow. Invasive due to radiation. Used in oncology and neurodegenerative disease research [3]. |

| SPECT (Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography) | Indirect (Hemodynamic response) | Poor (~5-9 min) [3] | Good (~6 mm) [3] | Similar to PET but uses different tracers and has longer acquisition times. Applied in epilepsy and dementia diagnostics [3]. |

The trade-off is clearly visualized in the following diagram, which maps the spatiotemporal relationship of these core techniques:

Figure 1: The Fundamental Trade-Off in Neuroimaging. Techniques like EEG and MEG offer high temporal resolution but lower spatial resolution, while methods like fMRI and PET provide high spatial resolution at the cost of lower temporal resolution [8] [2].

Beyond the core techniques, new technologies are emerging that push these boundaries. Optically Pumped Magnetometers (OPM-MEGs) are a newer type of MEG sensor that can be positioned directly on the scalp, improving the signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution compared to traditional SQUID-MEGs while retaining millisecond temporal resolution. This enhances the ability to track brain signatures associated with cortical abnormalities [2].

Advancements in High-Temporal-Resolution fMRI

While fMRI is known for its high spatial resolution, significant technological efforts are being made to improve its temporal resolution, thereby narrowing the gap with electrophysiological methods. The drive for fast fMRI is powered by highly accelerated acquisition protocols, such as simultaneous multi-slice imaging, which now allow for whole-brain imaging with sub-second temporal resolution [9].

These advancements are unlocking new neuroscientific applications. High-temporal-resolution fMRI is capable of resolving previously undetectable neural dynamics. For instance, it enables the investigation of mesoscale-level computations within the brain's cortical layers and columns. Different layers of the cerebral cortex often serve distinct input, output, and internal processing functions. Submillimeter fMRI, particularly at ultra-high magnetic field strengths (7 Tesla and above), allows researchers to non-invasively measure these depth-dependent functional responses in humans, providing insights into human laminar organization that were previously only accessible through invasive animal studies [9].

Another major application is in the study of functional connectivity. The brain is a dynamic network, and the strength of connections between regions fluctuates rapidly. Fast fMRI provides a window into these transient connectivity states, offering a more accurate picture of the brain's functional organization than conventional slower scans. However, pushing the limits of fMRI resolution introduces challenges, including increased sensitivity to physiological noise (e.g., from breathing and heart rate) and the need for more sophisticated analytical methods to extract meaningful neural information from the complex data [9].

The following diagram outlines a typical experimental workflow for a high-temporal-resolution fMRI study, for example, one investigating cortical layer-specific activity:

Figure 2: Workflow for a high-spatiotemporal-resolution fMRI experiment. Key advancements depend on ultra-high-field scanners and specialized acquisition protocols, followed by sophisticated analysis to resolve fine-grained brain structures [9].

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Implementing high-temporal-resolution neuroimaging requires meticulous experimental design and a specific set of research tools. Below is a detailed protocol for an experiment using MEG to study fast neural dynamics, along with a toolkit of essential reagents and materials.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: MEG Study of Visually Evoked Fields (VEFs)

This protocol is adapted from research investigating visual processing using both traditional SQUID-MEG and modern OPM-MEG systems [2].

- Participant Selection and Preparation: Recruit healthy participants with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. After providing informed consent, screen participants for any magnetic contaminants (e.g., dental work, implants) that are incompatible with MEG. Instruct participants to remove all metallic objects.

- Stimulus Design:

- Flash Stimulus (FS): Prepare a full-field visual stimulus consisting of short, high-contrast white flashes against a dark background. Set the flash duration to 80 ms.

- Pattern Reversal Stimulus (PR): Create a black-and-white checkerboard pattern. Program the stimulus to reverse the colors of the checks at a frequency of 2 Hz (every 500 ms). These stimuli are standard for probing early visual processing pathways.

- Sensor Setup and Positioning:

- For SQUID-MEG: Position the participant's head within the helmet-style dewar containing the fixed superconducting sensors. Ensure the head is as close as possible to the sensors, though the typical scalp-to-sensor distance is around 50 mm.

- For OPM-MEG: Mount the individual OPM sensors directly onto the participant's scalp using a customized helmet. This allows for a significantly closer scalp-to-sensor distance of approximately 5 mm, enhancing signal quality.

- Data Acquisition:

- Place the participant in a Magnetically Shielded Room (MSR) to attenuate environmental magnetic noise.

- Instruct the participant to fixate on a central point on the screen and present the FS and PR stimuli in a block-design or randomized order.

- Record the continuous neuromagnetic data throughout the stimulus presentation and include baseline periods.

- Simultaneously record an electrooculogram (EOG) and electrocardiogram (ECG) to identify and later remove artifacts from eye blinks and cardiac activity.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Apply signal-space projection (SSP) or similar algorithms to filter out environmental and physiological noise.

- Segment the continuous data into epochs time-locked to the onset of each visual stimulus.

- Perform baseline correction and artifact rejection to remove epochs contaminated by large head movements or other artifacts.

- Source Reconstruction and Analysis:

- Coregister the MEG sensor data with the participant's anatomical MRI scan to create a precise head model.

- Use beamforming algorithms (e.g., Synthetic Aperture Magnetometry - SAM) or minimum-norm estimates (MNE) to reconstruct the neural sources of the observed magnetic fields in the brain.

- Analyze the time course of the evoked responses (VEFs) from visual cortical areas. Key metrics include the peak latency (in ms) and amplitude (in femto-Tesla) of the major components of the response, which reflect the timing and strength of neural synchronization in the visual cortex.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for High-Resolution Neuroimaging Experiments

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Cap | A cap embedded with an array of electrodes (e.g., 64, 128, or 256 channels) that makes consistent contact with the scalp to record electrical activity. The conductive gel used with the cap ensures a low-impedance connection [3]. |

| OPM-MEG Sensors | Miniaturized, wearable magnetometers that measure neuromagnetic fields directly from the scalp surface. They offer superior spatial resolution compared to traditional MEG by allowing a closer sensor-to-brain distance [2]. |

| Ultra-High Field MRI Scanner (7T+) | MRI systems with powerful magnetic fields (7 Tesla, 11.7T) that provide the increased signal-to-noise ratio necessary for acquiring high-spatial-resolution fMRI data, such as for cortical layer-specific imaging [9] [10]. |

| Magnetically Shielded Room (MSR) | A specialized room with layers of mu-metal and aluminum that screens out the Earth's magnetic field and other ambient magnetic noise, creating an environment quiet enough for sensitive MEG measurements [2]. |

| Biocompatible Adhesive Paste | Used to securely attach OPM-MEG sensors or EEG electrodes to the scalp, ensuring stability and reducing motion artifacts during data acquisition [2]. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Software packages (e.g., Presentation, PsychoPy) that allow for the precise, millisecond-accurate delivery of visual, auditory, or somatosensory stimuli during neuroimaging experiments, which is crucial for event-related potential (ERP) and field studies. |

Implications for Drug Development and Neurology

Advances in high-temporal-resolution neuroimaging are progressively translating into valuable tools for pharmaceutical research and clinical neurology. The ability to track brain function with millisecond precision provides objective, quantifiable biomarkers that can revolutionize several stages of drug development.

In early-phase clinical trials, EEG and MEG can serve as sensitive measures of a candidate drug's target engagement and central nervous system (CNS) activity. For instance, by examining how a neuroactive compound modulates specific event-related potentials (ERPs) or neural oscillations, researchers can obtain early proof-of-pharmacological activity, often with smaller sample sizes and at lower costs than large-scale clinical endpoint trials. This can help in making critical go/no-go decisions earlier in the development pipeline.

Furthermore, these techniques are powerful for patient stratification and understanding treatment mechanisms in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Abnormalities in neural timing and connectivity are hallmarks of conditions like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and schizophrenia. MEG, with its high spatiotemporal resolution, has been used to identify distinct neural signatures in conditions like PTSD and ASD [2]. By using these signatures to select homogenous patient groups for trials, the likelihood of detecting a true treatment effect increases significantly.

The emergence of digital brain models and digital twins represents a frontier where neuroimaging data is integral. These are personalized computational models of a patient's brain that can be updated with real-world data over time. High-resolution temporal data from EEG and MEG can be incorporated into these models to simulate disease progression or predict individual responses to therapies, paving the way for truly personalized medicine in neurology [10].

The field of neuroimaging is continuously evolving, with a clear trajectory toward breaking the traditional spatiotemporal resolution trade-off. Future developments will be driven by several key trends:

- Convergence of Technologies: The combination of multiple imaging modalities, such as simultaneously acquiring EEG and fMRI data, allows researchers to leverage the high temporal resolution of EEG with the high spatial resolution of fMRI in a single experiment. Furthermore, the integration of AI and machine learning with neuroimaging is leading to better noise correction, source reconstruction, and pattern detection in high-resolution datasets, accelerating the extraction of biologically meaningful insights [10] [11].

- Hardware Innovation: The ongoing development of more powerful MRI scanners (e.g., 11.7T) and the commercialization of portable, wearable neuroimaging systems like OPM-MEG will make high-quality data more accessible. This expands the scope of research from controlled laboratory settings to more naturalistic environments and enables studies on diverse populations, including children and patients with mobility issues [10] [2].

- Pushing Biophysical Limits: Research will continue to probe the ultimate biological limits of fMRI's spatial and temporal precision. Efforts to better understand the vascular point-spread function and to develop biophysical models that disentangle neuronal signals from vascular confounds will be crucial for interpreting data from submillimeter and fast fMRI studies [9].

In conclusion, temporal resolution is a foundational concept in neuroimaging that dictates our capacity to observe the brain in action. From the millisecond precision of EEG and MEG to the evolving capabilities of fast fMRI, each technique offers a unique window into brain dynamics. For researchers and drug developers, understanding these tools and their ongoing advancements is critical for designing robust experiments, identifying novel biomarkers, and ultimately developing more effective therapies for brain disorders. As technology continues to push the boundaries of what is measurable, our understanding of the dynamic human brain will undoubtedly deepen, revealing the intricate temporal choreography that underpins all thought and behavior.

Non-invasive neuroimaging techniques are foundational to modern cognitive neuroscience, yet each modality remains constrained by a fundamental trade-off between spatial resolution and temporal resolution [6]. No single technology currently captures brain activity at high resolution in both space and time, creating a compelling need for multimodal integration. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provides millimeter-scale spatial maps but reflects a sluggish hemodynamic response that integrates neural activity over seconds, while electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) offer millisecond-scale temporal precision but suffer from poor spatial detail [6] [12]. This technical whitpaper provides a comparative analysis of key neuroimaging technologies, focusing on their complementary strengths and methodologies for integration, framed within the context of advancing spatiotemporal resolution for research and drug development applications.

Bridging these complementary strengths to obtain a unified, high spatiotemporal resolution view of neural source activity is critical for understanding complex processes such as speech comprehension, which recruits multiple subprocesses unfolding on the order of milliseconds across distributed cortical networks [6]. The quest to overcome these limitations has driven innovation in both unimodal technologies and multimodal fusion approaches, creating an evolving toolkit for researchers and pharmaceutical developers seeking to understand brain function and evaluate therapeutic interventions.

Core Neuroimaging Modalities: Technical Specifications and Mechanisms

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

fMRI measures brain activity indirectly through the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast, which identifies regions with significantly different concentrations of oxygenated blood [13]. The high metabolic demand of active brain regions requires an influx of oxygen-rich blood, increasing the intensity of voxels where activity can be observed [13]. Typical analysis convolves detected timescale peaks with a hemodynamic response function and utilizes a general linear model that treats different conditions, motion parameters, and polynomial baselines as regressors to generate a map of significantly activated voxels [13]. This process creates a spatially accurate but temporally sluggish depiction of cortical BOLD fluctuations and, by extension, the underlying neural activity.

Electroencephalography (EEG) and Magnetoencephalography (MEG)

EEG directly detects and records electrical signals associated with neural activity from scalp electrodes [13]. As signals are transduced from neuron to neuron, the postsynaptic potentials that result from neurotransmitter detection create electrical activity which, while individually weak, sums to produce larger voltage potentials measurable on the scalp [13]. With a series of electrodes measured against a reference at rapid sampling rates, EEG generates temporally precise measurements of these voltage differences [13].

MEG operates on a similar physiological principle but measures the magnetic fields induced by postsynaptic currents in spatially aligned neurons [6]. Both techniques offer excellent temporal resolution but face challenges in spatial localization due to the inverse problem, where countless possible source configurations can explain the observed sensor-level data [6] [13].

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Measured Signal | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | 1-3 mm [12] | 1-3 seconds [12] | Hemodynamic (BOLD) response [13] | High spatial localization; Whole-brain coverage [6] | Indirect neural measure; Slow temporal response; Expensive equipment [6] |

| MEG | ~5-10 mm (with source imaging) [6] | <1 millisecond [6] | Magnetic fields from postsynaptic currents [6] | Excellent temporal resolution; Direct neural measure [6] | Expensive equipment; Sensitive to environmental noise [6] |

| EEG | ~10-20 mm (with source imaging) [13] | 1-10 milliseconds [12] | Scalp electrical potentials [13] | Direct neural measure; Low cost; Portable systems available [13] | Poor spatial resolution; Sensitive to artifacts [13] |

| ECoG | 1-10 mm (limited coverage) [6] | Millisecond scale [6] | Direct cortical electrical potentials | High fidelity signal; Excellent spatiotemporal resolution [6] | Invasive (requires surgery); Limited cortical coverage [6] |

The Spatiotemporal Resolution Trade-Off Visualized

The fundamental relationship between spatial and temporal resolution across major neuroimaging modalities can be visualized as follows:

Multimodal Integration Approaches: Overcoming Technical Limitations

fMRI-Constrained EEG Source Imaging

A prominent integration approach uses fMRI activation maps as spatial priors to guide EEG source localization, addressing the mathematically ill-posed "inverse problem" in EEG [13]. Traditional methods employ fMRI-derived BOLD activation maps to construct spatial constraints on the source space in the form of a source covariance matrix, where active sources not present in the fMRI are penalized [13]. However, these "hard" constraint approaches can introduce bias when EEG and fMRI signals mismatch due to neurovascular decoupling or signal detection failure [13].

Advanced implementations now use hierarchical empirical Bayesian models that incorporate fMRI information as "soft" constraints, where the fMRI-active map is modeled as a prior with relative weighting estimated via hyperparameters [13]. A spatiotemporal fMRI-constrained EEG source imaging method further addresses temporal mismatches by calculating optimal subsets of fMRI priors based on particular windows of interest in EEG data, creating time-variant fMRI constraints [13]. This approach utilizes the high temporal resolution of EEG to compute current density mapping of cortical activity, informed by the high spatial resolution of fMRI in a time-variant, spatially selective manner [13].

Deep Learning-Based Fusion Models

Recent transformer-based encoding models represent a paradigm shift in multimodal fusion, simultaneously predicting MEG and fMRI signals for multiple subjects as a function of stimulus features, constrained by the requirement that both modalities originate from the same source estimates in a latent source space [6]. These models incorporate anatomical information and biophysical forward models for MEG and fMRI to estimate source activity that is high-resolution in both time and space [6].

The architecture typically includes:

- Input layers processing multiple stimulus feature streams (word embeddings, phoneme features, mel-spectrograms)

- Transformer encoders to capture dependencies between features and feature-dependent neural response latency

- Source layers projecting outputs to cortical source space

- Modality-specific forward models incorporating subject-specific anatomical information [6]

This approach demonstrates strong generalizability across unseen subjects and modalities, with estimated source activity predicting electrocorticography (ECoG) signals more accurately than models trained directly on ECoG data [6].

Data-Driven Multimodal Fusion

Alternative data-driven approaches include independent component analysis (ICA), linear regression, and hybrid methods that explore insights gained from two or more modalities [12]. These techniques allow researchers to merge EEG and fMRI into a common feature space, generating spatial-temporal independent components that can serve as biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric conditions [12].

Advanced implementations now capture spatially dynamic brain networks that undergo spatial changes via expansion or shrinking over time, in addition to dynamical changes in functional connectivity [12]. Linking these spatially varying fMRI networks with time-varying EEG spectral power (delta, theta, alpha, beta) enables concurrent capture of high spatial and temporal resolutions offered by these complementary imaging modalities [12].

Table 2: Multimodal Fusion Methodologies and Applications

| Fusion Approach | Core Methodology | Key Advantages | Validated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI-Constrained EEG Source Imaging [13] | fMRI BOLD maps as spatial priors for EEG inverse problem | Addresses EEG's ill-posed inverse problem; Improves spatial localization | Visual/motor activation tasks; Central motor system plasticity [13] |

| M/EEG-fMRI Fusion Based on Representational Similarity [14] | Links multivariate response patterns based on representational similarity | Identifies brain responses simultaneously in space and time; Wide cognitive neuroscience applicability | Cognitive neuroscience; Understanding neural dynamics of cognition [14] |

| Transformer-Based Encoding Models [6] | Deep learning architecture predicting MEG and fMRI from stimulus features | Preserves high spatiotemporal resolution; Generalizes across subjects and modalities | Naturalistic speech comprehension; Single-trial neural dynamics [6] |

| Spatially Dynamic Network Analysis [12] | Sliding window spatially constrained ICA coupled with EEG spectral power | Captures network expansion/shrinking over time; Links spatial dynamics with spectral power | Resting state connectivity; Schizophrenia biomarker identification [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Neuroimaging

Protocol: Naturalistic MEG-fMRI Fusion for Speech Comprehension

Objective: To estimate latent cortical source responses with high spatiotemporal resolution during naturalistic speech comprehension using combined MEG and fMRI data [6].

Stimuli and Design:

- Present ≥7 hours of narrative stories as stimuli

- Maintain identical stimuli across MEG and fMRI sessions

- Sample feature vectors (contextual word embeddings, phoneme features, mel-spectrograms) at 50 Hz [6]

Data Acquisition:

- Collect whole-head MEG data during passive listening

- Obtain fMRI data from separate sessions or existing datasets

- Acquire structural MRI for subject-specific source space construction [6]

Source Space Construction:

- Construct subject-specific source spaces according to structural MRI scans

- Use octahedron-based subsampling method (e.g., MNE-Python)

- Model sources as equivalent current dipoles oriented perpendicularly to cortical surface

- Compute source morphing matrices and lead-field matrices incorporating anatomical information [6]

Model Architecture and Training:

- Implement transformer-based encoding model with four encoder layers

- Project transformer outputs to "fsaverage" source space (8,196 sources)

- Apply subject-specific source morphing matrices

- Generate MEG predictions via lead-field forward models

- Train model to simultaneously predict MEG and fMRI from multiple subjects [6]

Validation:

- Compare model performance against single-modality encoding models

- Evaluate spatial and temporal fidelity against minimum-norm estimates in simulations

- Assess generalizability to unseen subjects and modalities

- Validate against electrocorticography (ECoG) data from separate datasets [6]

Protocol: Spatiotemporal fMRI-Constrained EEG Source Imaging

Objective: To achieve high spatiotemporal accuracy in EEG source imaging by employing the most probable fMRI spatial subsets to guide localization in a time-variant fashion [13].

Data Acquisition:

- Conduct simultaneous EEG-fMRI recording or separate sessions with identical tasks

- For fMRI: Employ block or event-related design contrasting task vs. baseline conditions

- For EEG: Use high-density electrode systems (64+ channels) with appropriate referencing

fMRI Data Analysis:

- Preprocess fMRI data (motion correction, normalization, smoothing)

- Apply general linear model (GLM) for statistical analysis

- Generate activation map of statistically significant voxels (p<0.05 threshold)

- Divide activation map into multiple submaps based on clusters or functional regions [13]

EEG Source Imaging:

- Construct lead field matrix based on head model (e.g., BEM or FEM)

- Apply hierarchical empirical Bayesian framework for source estimation

- Model fMRI information as weighted sum of multiple submaps

- Estimate weighting hyperparameters via Expectation Maximization (EM)

- Compute current density mapping using time-variant fMRI constraints [13]

Validation:

- Compare localization accuracy against traditional fMRI-constrained methods

- Assess variation in source estimates across time windows

- Evaluate biological plausibility through comparison with established neuroanatomy [13]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Advanced Neuroimaging Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Modeling Software | MNE-Python, BrainStorm, FieldTrip | Cortical source space construction; Forward model computation; Inverse problem solution | MNE-Python offers octahedron-based source subsampling [6] |

| Multimodal Fusion Platforms | GIFT Toolbox, EEGLAB, SPM | Implementation of ICA, linear regression, and hybrid fusion methods | GIFT toolbox enables spatially constrained ICA [12] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow | Implementation of transformer-based encoding models | Custom architectures for neurogenerative modeling [6] |

| Stimulus Presentation Systems | PsychToolbox, Presentation, E-Prime | Precise timing control for multimodal experiments | Critical for naturalistic paradigms [6] |

| Head Modeling Solutions | Boundary Element Method (BEM), Finite Element Method (FEM) | Construction of biophysically accurate volume conductor models | Essential for EEG/MEG source imaging [13] |

| Neurovascular Modeling Tools | Hemodynamic response function estimators | Modeling BOLD signal from neural activity | Bridges EEG and fMRI temporal scales [12] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The neuroimaging field is rapidly evolving toward greater accessibility and spatiotemporal precision. Portable MRI technologies are now being deployed in previously inaccessible settings including ambulances, bedside care, and participants' homes, potentially revolutionizing data collection from rural, economically disadvantaged, and historically underrepresented populations [15]. These systems vary in field strength (mid-field: 0.1-1 T, low-field: 0.01<0.1 T, ultra-low field: <0.01 T) and offer user-friendly interfaces that maintain sufficient image quality for neuroscience research [15].

Simultaneously, advanced artificial intelligence algorithms are being integrated across the neuroimaging pipeline, from data acquisition and artifact correction to multimodal fusion and pattern classification [6] [12]. The convergence of increased hardware accessibility and sophisticated computational methods promises to transform neuroimaging from a specialized technique to a widely available tool for neuroscience research and therapeutic development.

These technological advances bring important ethical and practical considerations, including the need for appropriate training, safety protocols for non-traditional settings, and governance frameworks for research conducted outside traditional institutions [15]. As the neuroimaging community addresses these challenges, the field moves closer to realizing the ultimate goal of non-invasive whole-brain recording at millimeter and millisecond resolution, potentially transforming our understanding of brain function and disorder.

Understanding the link between neuroelectrical activity and hemodynamic response is a cornerstone of modern neuroscience, with profound implications for both basic research and clinical drug development. This relationship, termed neurovascular coupling, describes the intricate biological process whereby active neurons dynamically regulate local blood flow to meet metabolic demands [16]. The study of this coupling is pivotal for interpreting functional neuroimaging data, as techniques like functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) rely on hemodynamic signals as an indirect proxy for underlying neural events [17] [3]. The fundamental challenge in this domain lies in the inherent spatiotemporal resolution trade-off; while electrophysiological methods like electroencephalography (EEG) capture neural events at millisecond temporal resolution, hemodynamic methods like fMRI provide superior spatial localization but operate on a timescale of seconds [3] [2]. This guide delves into the biological mechanisms, measurement methodologies, and quantitative relationships that bridge this resolution gap, providing a technical foundation for advanced neuroimaging research and therapeutic development.

Core Biological Mechanisms of Neurovascular Coupling

The hemodynamic response is a localized process orchestrated by a coordinated neurovascular unit, comprising neurons, astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and pericytes [16]. Upon neuronal activation, a cascade of signaling events leads to the dilation of arterioles and increased cerebral blood flow, a response finely tuned to deliver oxygen and glucose to active brain regions.

Key Cellular Signaling Pathways

The vasodilation and constriction mechanisms within the neurovascular unit represent a sophisticated cellular control system. The table below summarizes the primary pathways involved.

Table 1: Key Cellular Signaling Pathways in Neurovascular Coupling

| Cellular Actor | Primary Stimulus | Signaling Pathway | Vascular Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes | Neuronal glutamate (via mGluR) | Ca²⁺ influx → Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) → Arachidonic Acid → 20-HETE production [16] | Vasoconstriction |

| Endothelial Cells | Shear stress, neurotransmitters | Nitric Oxide (NO) release → increased cGMP in smooth muscle → decreased Ca²⁺ [16] | Vasodilation |

| Smooth Muscle | Nitric Oxide (NO) | cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activation → decreased intracellular Ca²⁺ [16] | Vasodilation |

| Pericytes | Adrenergic (β2) receptor stimulation | Receptor activation → relaxation [16] | Vasodilation |

| Pericytes | Cholinergic (α2) receptor stimulation | Receptor activation → contraction [16] | Vasoconstriction |

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated interaction between these cellular components during neuronal activation.

Measuring the Link: Neuroimaging Techniques and Their Resolution

The relationship between neural activity and hemodynamics is measured using a suite of neuroimaging technologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations in spatial and temporal resolution.

Table 2: Spatiotemporal Resolution of Key Neuroimaging Modalities

| Technique | What It Measures | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI (BOLD) | Blood oxygenation-level dependent signal [2] | ~4-5 seconds [3] | ~2 mm [3] | Excellent whole-brain coverage | Indirect, slow measure of neural activity |

| EEG | Scalp electrical potentials from synchronized neuronal populations [18] | <1 millisecond [3] | ~10 mm [3] | Direct measure of neural electrical activity | Poor spatial resolution, sensitive to reference |

| MEG | Magnetic fields from intracellular electrical currents [2] | <1 millisecond [3] | ~5 mm [3] | High spatiotemporal resolution | Expensive, requires magnetic shielding |

| fNIRS | Concentration changes in oxygenated/deoxygenated hemoglobin [18] | ~0.1-1 second | ~10-20 mm | Portable, low-cost | Limited to cortical surface |

| PET | Regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) or glucose metabolism [3] | ~1-2 minutes [3] | ~4 mm [3] | Can measure neurochemistry | Invasive (radioactive tracers), poor temporal resolution |

Recent advancements are pushing the boundaries of this trade-off. Magnetoencephalography (MEG), particularly next-generation systems like Optically Pumped Magnetometers (OPM-MEG), offers a promising combination of high temporal resolution (<1 ms) and improved spatial resolution by allowing sensors to be positioned closer to the scalp [19] [2]. This enables more precise spatiotemporal tracking of neural dynamics, such as visually evoked fields [2].

Quantitative Relationships: Correlating Electrical and Hemodynamic Activity

Empirical studies reveal that the relationship between electrical and hemodynamic signals is robust but complex, varying with behavioral state and the specific neural signal measured.

State-Dependent Correlations and Predictive Power

Simultaneous measurements in awake animals show that neurovascular coupling is generally consistent across different behavioral states (e.g., sensory stimulation, volitional whisking, and rest). However, the predictive power of neural activity for subsequent hemodynamic changes is strongly state-dependent [17].

Table 3: Predictive Power of Neural Activity for Hemodynamic Signals Across States

| Behavioral State | Best Neural Predictor | Coefficient of Determination (R²) with CBV | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory Stimulation | Gamma-band LFP power [17] | R² = 0.77 (median) [17] | Strong, reliable coupling; HRF dynamics are stable. |

| Volitional Whisking | Gamma-band LFP power [17] | R² = 0.21 (median) [17] | Weaker prediction, often associated with larger body motion. |

| Resting State | Gamma-band LFP power & MUA [17] | Weak correlations [17] | Large spontaneous CBV fluctuations can have non-neuronal origins. |

A critical finding is that spontaneous hemodynamic fluctuations observed during "rest" are only weakly correlated with local neural activity. Large spontaneous changes in cerebral blood volume (CBV) can be driven by volitional movements and, importantly, persist even when local spiking and glutamatergic inputs are blocked, suggesting a significant contribution from non-neuronal origins [17]. This has direct implications for the interpretation of resting-state fMRI studies.

Stimulus Contrast and Latency in Visual Processing

Research combining EEG and fNIRS during visual stimulation with graded contrasts provides deeper insight into how different aspects of the electrical signal relate to hemodynamics. Stimulus contrast is encoded primarily in the latency of the Visual Evoked Potential (VEP), with lower contrasts resulting in longer latencies, while stimulus identity is more closely tied to the VEP amplitude [18]. This temporal coding mechanism is crucial for distinguishing subtle sensory differences. Notably, the hemodynamic response (as measured by fNIRS) is more strongly correlated with the amplitude of the VEP than with its latency [18]. This underscores that hemodynamic signals predominantly reflect the magnitude of local synaptic activity integrated over time, rather than the precise timing of neural synchronization.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Neurovascular Coupling

To reliably capture the relationship between electrical and hemodynamic activity, rigorous experimental protocols are required. The following workflow details a multimodal approach used in visual processing studies.

Key Protocol Details:

- Stimuli: Full-field windmill checkerboard patterns with contrasts (100%, 10%, 1%) effectively manipulate VEP latency and amplitude [18].

- Block Design: A series of seven 25-second stimulation blocks interspersed with 30-second rest periods allows for robust signal averaging while minimizing habituation [18].

- Simultaneous Recording: Concurrent EEG and fNIRS capture both the fast electrophysiological response and the slower hemodynamic response to the same stimulus train, which is critical for establishing direct correlations [18].

- Data Alignment: Precise timing of stimulus onset relative to both data streams is essential for aligning the brief VEP with the slower hemodynamic response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This section catalogs critical reagents and tools used in neurovascular research, from human neuroimaging to animal models.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Neurovascular Investigations

| Category | Item / Reagent | Primary Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Neuroimaging | EEG System (e.g., Brain Vision) | Records scalp electrical potentials with high temporal resolution [18]. | Use 64+ channels; impedance should be kept below 10 kΩ [18]. |

| fNIRS System (e.g., TechEn CW6) | Measures concentration changes in oxygenated/deoxygenated hemoglobin [18]. | Optode placement over region of interest (e.g., O1, O2, Oz for visual cortex) is critical [18]. | |

| fMRI Scanner | Measures BOLD signal as an indirect marker of neural activity [3]. | High magnetic field strength (3T/7T) improves signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution. | |

| Animal Model Research | Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents (GBCAs) | Shortens T1 relaxation time in MRI, improving vessel and lesion visibility [20] [21]. | Choice between linear/macrocyclic and ionic/non-ionic affects stability and safety profile [20]. |

| Local Field Potential (LFP) / Multi-Unit Activity (MUA) Electrodes | Records extracellular neural activity (spiking and synaptic inputs) directly in the brain [17]. | Allows for direct correlation of specific neural signals (e.g., gamma power) with local hemodynamics [17]. | |

| Pharmacological Agents | Glutamate Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | To probe the role of glutamatergic signaling in triggering neurovascular coupling [16]. | mGluR agonists can trigger astrocyte Ca²⁺ waves and vasoconstriction [16]. |

| Nitric Oxide (NO) Synthase Inhibitors | To test the essential role of the NO pathway in vasodilation [16]. | Can attenuate the hemodynamic response to neural activation. | |

| Experimental Stimuli | E-Prime Software | Presents controlled visual stimuli and records precise timing markers [18]. | Ensures synchronization between stimulus events and recorded neural/hemodynamic data. |

The biological link between hemodynamic response and neuroelectrical activity is a sophisticated, multi-scale process governed by precise cellular and molecular mechanisms within the neurovascular unit. While a robust coupling exists, evidenced by the predictive power of gamma-band activity for blood volume changes during sensation, it is not a simple one-to-one relationship. The fidelity of this coupling is influenced by behavioral state, the specific neural signal measured, and can involve non-neuronal contributions. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these principles is essential. It allows for the critical interpretation of functional neuroimaging data, guides the selection of appropriate techniques to answer specific questions, and provides a mechanistic basis for identifying and testing novel therapeutic targets for neurological and neurovascular diseases. The continued development of high-resolution, multimodal imaging approaches promises to further unravel the complexities of this fundamental biological process.

From Theory to Practice: Applying High-Resolution Neuroimaging in Research and Therapy

In the field of cognitive neuroscience and clinical neurology, the ability to accurately localize brain function and pathology is paramount. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) represent two cornerstone technologies that enable researchers and clinicians to visualize brain activity with complementary strengths. The spatial resolution of a neuroimaging technique—its capacity to precisely distinguish between two separate points in the brain—fundamentally determines the scale of neural phenomena that can be reliably studied. For neuroscientists investigating the functional specialization of cortical columns, drug development professionals validating target engagement of novel therapeutics, or clinicians planning surgical interventions, understanding the capabilities and limitations of each modality is critical. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of how fMRI and PET achieve spatial localization, comparing their fundamental principles, practical implementations, and optimal applications within a broader framework of understanding spatiotemporal resolution trade-offs in neuroimaging research.

Fundamental Principles and Spatial Resolution Limits

The spatial precision of any neuroimaging technique is ultimately constrained by its underlying physical principles and signal generation mechanisms. fMRI and PET measure fundamentally different physiological correlates of brain activity, leading to distinct resolution characteristics.

fMRI: The Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) Effect

Functional MRI does not directly measure neural firing but instead detects changes in blood oxygenation that follow neural activity, a phenomenon known as neurovascular coupling. When a brain region becomes active, a complex physiological response delivers oxygenated blood to that area. The BOLD effect exploits the magnetic differences between oxygenated (diamagnetic) and deoxygenated (paramagnetic) hemoglobin. As neural activity increases, the local concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin rises relative to deoxygenated hemoglobin, leading to a slight increase in the MRI signal in T2*-weighted images [22]. This BOLD signal typically peaks 4-6 seconds after the neural event, providing an indirect and temporally smoothed measure of brain activity.

The spatial specificity of the BOLD signal is influenced by the vascular architecture. The most spatially precise signals originate from the capillary level, where neurovascular coupling is most direct. However, contributions from larger draining veins can displace the observed signal from the actual site of neural activity, potentially reducing spatial accuracy [9]. Technical advances, particularly the use of higher magnetic fields (7T and above) and optimized pulse sequences, have significantly improved fMRI's spatial resolution, now enabling sub-millimeter imaging that can distinguish cortical layers and columns in specialized settings [9].

PET: Radioactive Tracers and Positron Emission

PET imaging relies on the detection of gamma photons produced by positron-emitting radioactive tracers. A biologically relevant molecule (such as glucose, a neurotransmitter analog, or a pharmaceutical compound) is labeled with a radioisotope (e.g., ¹¹C, ¹⁸F, ¹⁵O) and administered to the subject. As the radiotracer accumulates in brain tissue, the radioactive decay emits positrons that travel a short distance before annihilating with electrons, producing two 511 keV gamma photons traveling in nearly opposite directions [23].

The spatial resolution of PET is fundamentally limited by several physical factors:

- Detector Size: The physical size of detector crystals typically represents the dominant limiting factor, with resolution approximately equal to half the crystal width [23].

- Positron Range: The distance a positron travels before annihilation varies by isotope (e.g., 0.54 mm for ¹⁸F vs. 6.14 mm for ⁸²Rb) [23].

- Photon Acollinearity: The slight deviation from 180 degrees in emitted gamma photons introduces Gaussian blurring proportional to detector ring diameter [23].

- Radial Elongation: Non-perpendicular incidence of gamma rays causes penetration into detector rings, creating asymmetric blurring that increases radially [23].

The combined effect of these factors means that clinical PET scanners typically achieve spatial resolutions of 4-5 mm, while specialized small-animal scanners can reach approximately 1 mm [24].

Table 1: Fundamental Physical Limits of Spatial Resolution

| Factor | fMRI | PET |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Signal Source | Hemodynamic response via BOLD effect | Radioactive tracer concentration via positron emission |

| Key Physical Constraints | Vascular architecture, magnetic field strength | Detector size, positron range, photon acollinearity |

| Typical Human Scanner Resolution | 1-3 mm (3T); <1 mm (7T+) [9] | 4-5 mm (clinical); ~1.5 mm (high-resolution research) [24] |

| Theoretical Maximum Resolution | ~0.1 mm (ultra-high field, microvascular) | ~0.5-1.0 mm (fundamental physical limits) [23] |

Quantitative Comparison of Spatial and Temporal Resolution

Understanding the complementary strengths of fMRI and PET requires direct comparison of their resolution characteristics across multiple dimensions. The inherent trade-offs between spatial and temporal resolution, sensitivity, and specificity guide modality selection for specific research or clinical questions.

Table 2: Spatial and Temporal Resolution Characteristics of fMRI and PET

| Characteristic | fMRI | PET |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 1-3 mm (3T); <1 mm (7T+) [9] | 4-5 mm (clinical); 1-2 mm (high-resolution research) [24] |

| Temporal Resolution | 1-3 seconds (limited by hemodynamic response) [22] | 30 seconds to several minutes (limited by tracer kinetics and counting statistics) |

| Spatial Specificity | Can be compromised by large vessel effects [9] | Directly reflects tracer concentration distribution |

| Depth Penetration | Whole-brain coverage | Whole-body capability |

| Quantitative Nature | Relative measure (%-signal change) | Absolute quantification possible (nCi/cc, binding potential) |

The spatial resolution advantage of fMRI enables investigations of mesoscale brain organization, including cortical layers and columns. Recent technological advances have pushed fMRI toward sub-millimeter voxel sizes and sub-second whole-brain imaging, revealing previously undetectable insights into neural responses [9]. In contrast, PET's strength lies not in raw spatial resolution but in its molecular specificity, allowing researchers to target specific neurochemical systems with appropriately designed radiotracers.

The temporal resolution of fMRI, while limited by the sluggish hemodynamic response, is sufficient to track task-related brain activity and spontaneous fluctuations in functional networks. Modern acquisition techniques like multiband imaging have reduced repetition times to 500 ms or less, enabling better characterization of the hemodynamic response shape and detection of higher-frequency dynamics [9]. PET temporal resolution is constrained by the need to accumulate sufficient radioactive counts for statistical precision and the kinetics of the tracer itself, with dynamic imaging typically requiring time frames of 30 seconds to several minutes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

fMRI Experimental Design and Acquisition

A typical fMRI task activation experiment involves presenting visual, auditory, or other stimuli to alternately induce different cognitive states while continuously acquiring MRI volumes. The most common designs include:

- Block Designs: Alternating periods of experimental and control conditions (typically 20-40 seconds each) to maximize detection power [22].

- Event-Related Designs: Brief, jittered presentations of trials with longer inter-stimulus intervals to characterize the hemodynamic response shape and timing [22].

Essential acquisition parameters for fMRI include:

- Magnetic Field Strength: Clinical scanners (1.5T, 3T); research scanners (7T and higher)

- Pulse Sequence: Typically T2*-weighted gradient-echo EPI for its sensitivity to BOLD contrast

- Spatial Resolution: 1.5-3.5 mm isotropic voxels (standard); <1 mm isotropic (high-resolution)

- Repetition Time (TR): 0.5-3.0 seconds (whole-brain coverage)

- Echo Time (TE): Optimized for T2* contrast at specific field strength

Data preprocessing pipelines typically include slice-timing correction, motion realignment, spatial normalization, and spatial smoothing. Statistical analysis often employs general linear models (GLM) to identify voxels whose time series significantly correlate with the experimental design, or data-driven approaches like independent components analysis (ICA) to identify coherent functional networks [22].

Diagram 1: fMRI Signal Pathway from Neural Activity to Activation Maps

PET Tracer Selection and Image Acquisition

PET experimental design begins with careful selection of an appropriate radiotracer matched to the biological target of interest:

- Metabolic Tracers: [¹⁸F]FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) for glucose metabolism

- Amyloid Tracers: [¹¹C]PiB, [¹⁸F]florbetapir, [¹⁸F]flutemetamol for β-amyloid plaques

- Tau Tracers: [¹⁸F]flortaucipir for tau neurofibrillary tangles

- Neurotransmission Tracers: Various ligands for dopamine, serotonin, and other systems

- Receptor Occupancy Tracers: For quantifying drug-target engagement [25] [26]

Essential acquisition parameters for PET include:

- Tracer Administration: Bolus injection or constant infusion (for dynamic imaging)

- Scan Duration: 30-90 minutes depending on tracer kinetics

- Image Reconstruction: Filtered back projection or iterative algorithms (OSEM, MAP)

- Attenuation Correction: Using transmission scan or CT-based methods

- Motion Correction: Frame-by-frame realignment or continuous tracking

Quantitative analysis typically involves extracting time-activity curves from regions of interest defined on co-registered structural MRI, with various kinetic modeling approaches used to derive physiologically meaningful parameters like binding potential (BPₙ𝒹) or metabolic rate [25].

Diagram 2: PET Signal Pathway from Tracer Injection to Parametric Maps

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for High-Resolution Neuroimaging

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI Pulse Sequences | Gradient-echo EPI, Multi-band EPI, VASO, GE-BOLD, SE-BOLD | Optimizing BOLD sensitivity, spatial specificity, and acquisition speed [9] |

| PET Radiotracers | [¹⁸F]FDG (metabolism), [¹¹C]PiB (amyloid), [¹⁸F]flortaucipir (tau), [¹¹C]raclopride (dopamine D2/D3) | Targeting specific molecular pathways and neurochemical systems [25] [26] |

| Analysis Software Platforms | FSL, SPM, FreeSurfer, AFNI, PETSurfer | Image processing, statistical analysis, and visualization [22] [25] |

| Multimodal Integration Tools | SPM, MRICloud, BLAzER methodology | Co-registration of PET with structural MRI and functional maps [25] |

| High-Field Scanners | 3T, 7T, and higher human MRI systems; High-resolution research tomographs (HRRT) for PET | Enabling sub-millimeter spatial resolution for both modalities [9] [24] |

Advanced Applications and Multimodal Integration

The complementary strengths of fMRI and PET have inspired sophisticated multimodal approaches that overcome the limitations of either technique alone. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI-PET imaging, though technically challenging, provides unparalleled access to the relationships between electrophysiology, hemodynamics, and metabolism [27]. Recent methodological advances have enabled researchers to track dynamic changes in glucose uptake using functional PET (fPET) at timescales approaching one minute, revealing tightly coupled temporal progression of global hemodynamics and metabolism during sleep-wake transitions [27].

In clinical neuroscience, PET and fMRI play complementary roles in drug development. fMRI provides sensitive measures of circuit-level engagement, while PET offers direct quantification of target occupancy and pharmacodynamic effects. In neurodegenerative disease research, amyloid and tau PET identify protein pathology, while fMRI reveals associated functional network alterations [26]. The integration of these multimodal data with machine learning approaches has shown promise for improving diagnostic and prognostic accuracy in conditions like Alzheimer's disease [28].

Advanced analytical frameworks now enable direct comparison of whole-brain connectomes derived from fMRI and PET data. Spatially constrained independent component analysis (scICA) using fMRI components as spatial priors can estimate corresponding PET connectomes, revealing both common and modality-specific patterns of network organization [29]. These approaches are particularly valuable for understanding how molecular pathology relates to functional network disruption in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Spatial resolution remains a fundamental consideration in neuroimaging research, with fMRI and PET offering complementary approaches to localizing brain function and pathology. fMRI provides superior spatial resolution and is ideal for mapping neural circuits and functional networks, while PET offers unique molecular specificity for targeting neurochemical systems. Understanding the physical principles, technical requirements, and methodological approaches of each modality enables researchers to select the optimal tool for their specific neuroscientific questions. The continuing advancement of both technologies—with fMRI pushing toward finer spatial scales and PET developing novel tracers and dynamic imaging paradigms—promises to further enhance our ability to precisely localize and quantify brain function in health and disease. The integration of these modalities through sophisticated analytical frameworks represents the future of neuroimaging, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of brain organization across spatial scales and biological domains.