Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps and Consensus Signatures: A New Paradigm for Robust Biomarker and Drug Target Discovery

This article explores the transformative potential of spatial overlap frequency maps and consensus signature methodologies in biomedical research and drug development.

Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps and Consensus Signatures: A New Paradigm for Robust Biomarker and Drug Target Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of spatial overlap frequency maps and consensus signature methodologies in biomedical research and drug development. We provide a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists, covering the foundational principles of these data-driven techniques for identifying robust spatial biomarkers. The content details methodological workflows for generating consensus signatures from multiple discovery sets, discusses common pitfalls and optimization strategies to enhance reproducibility, and presents rigorous validation frameworks for comparing model performance and spatial extent. By synthesizing insights from neuroscience, oncology, and computational biology, this resource equips professionals with the knowledge to leverage these approaches for uncovering reliable disease signatures and therapeutic targets, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery pipeline.

Defining Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps and Consensus Signatures: From Basic Concepts to Foundational Principles

Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps (SOFMs) represent a advanced methodology in computational neuroscience and bioinformatics for identifying robust brain-behavior relationships. This approach marks a significant evolution from traditional, theory-driven Region of Interest (ROI) analyses toward fully data-driven exploratory frameworks. Where classic ROIs rely on a priori anatomical or functional hypotheses that may miss complex or distributed neural patterns, SOFMs computationally derive "statistical regions of interest" (sROIs) by aggregating spatial associations across numerous bootstrap-style iterations in large datasets [1]. The core output is a spatial map where the value at each location (voxel) reflects its frequency of selection as significantly associated with a behavioral or cognitive outcome across many discovery subsets. This frequency serves as a direct metric of the region's consensus and replicability, forming the basis for a "consensus signature mask" used in subsequent validation [1]. This whitepaper details the core principles, methodological protocols, and applications of SOFMs, framing them within the broader thesis of consensus signature research for drug development and biomarker discovery.

Core Methodology and Experimental Protocols

The generation and validation of a consensus brain signature via SOFMs follow a rigorous, multi-stage pipeline. The following workflow delineates the primary stages from data preparation to final model validation.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The foundation of a robust SOFM lies in high-quality, standardized input data. The following protocol is adapted from large-scale validation studies [1].

- Imaging Cohorts: The method requires a large, well-characterized discovery dataset. For example, a discovery set might comprise 578 participants from the UC Davis Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Longitudinal Diversity Cohort and 831 participants from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Phase 3 (ADNI 3) [1]. A separate, independent cohort (e.g., 348 participants from UCD and 435 from ADNI 1) must be held back for validation.

- Image Processing:

- Brain Extraction: Utilize convolutional neural net recognition of the intracranial cavity followed by meticulous human quality control [1].

- Registration: Perform affine and B-spline registration of the intracranial cavity image to a standard structural template [1].

- Tissue Segmentation: Execute native-space tissue segmentation into gray matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. For studies focused on GM thickness, this is the primary variable of interest [1].

- Behavioral/Cognitive Metrics: Obtain precise measures of the outcome of interest. Examples include episodic memory composites from neuropsychological batteries (e.g., Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales) or informant-based measures of everyday function (e.g., Everyday Cognition scales) [1].

Discovery Phase: Constructing the Spatial Overlap Frequency Map

The discovery phase is an iterative process designed to avoid the pitfalls of inflated associations and poor reproducibility common in smaller, single-discovery sets [1].

- Random Subset Selection: Randomly select a large number of subsets (e.g., 40 subsets) of a specified size (e.g., n=400) from the full discovery cohort. This resampling process is crucial for assessing stability [1].

- Voxel-Wise Association Analysis: For each subset, perform a mass-univariate analysis. At each voxel, compute the association between the imaging variable (e.g., GM thickness) and the behavioral outcome (e.g., memory score) using an appropriate statistical model (e.g., linear regression) [1].

- Feature Selection (Binary Mask Creation): For each analysis, create a binary map identifying "significant" voxels. This is typically done by applying a statistical threshold (p-value) to the association maps. This step converts a continuous statistical map into a discrete spatial selection [1].

- Aggregation and Frequency Calculation: Spatially sum all the binary masks generated from the iterative subsets. The value at each voxel in the resulting SOFM is its frequency of selection—the number of times it was deemed statistically significant across all discovery subsets. This map visualizes the consensus and reliability of brain-behavior associations [1].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Discovery Phase in a Representative SOFM Study

| Parameter | Description | Exemplar Value from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Cohort Size | Total number of participants in the initial discovery pool. | ~1,400 participants (combined from multiple cohorts) [1] |

| Random Subset Size (n) | Number of participants in each bootstrap-style sample. | 400 [1] |

| Number of Iterations (k) | Number of randomly selected discovery subsets analyzed. | 40 [1] |

| Primary Imaging Phenotype | The neuroimaging measure used in the association analysis. | Regional Gray Matter Thickness [1] |

| Statistical Threshold | The criterion for selecting significant voxels in each iteration. | p-value < 0.05 (voxel-wise) [1] |

Defining the Consensus Signature Mask

The SOFM is a continuous map. To create a usable biomarker, it must be thresholded to create a definitive consensus signature mask. High-frequency regions are those that consistently demonstrate an association with the outcome, regardless of the specific sample composition.

- Threshold Selection: Apply a frequency threshold to the SOFM. For example, only voxels that were significant in more than 70% of the discovery subsets might be retained. This threshold can be optimized based on the desired balance between selectivity and sensitivity.

- Mask Creation: The resulting set of high-frequency voxels is defined as the "consensus signature mask." This mask represents the aggregated, data-driven sROIs most robustly associated with the behavioral domain [1].

Validation Phase: Testing Model Robustness

The final, critical step is to test the consensus signature in completely independent data, demonstrating that it is not a feature of a specific dataset.

- Signature Score Calculation: In the independent validation cohort, extract the average imaging value (e.g., mean GM thickness) from all voxels within the consensus signature mask for each participant. This creates a single, composite "signature score" [1].

- Model Fit Replicability: Test the association between the signature score and the behavioral outcome in the validation cohort. High replicability is demonstrated by a strong, significant association, confirming the signature's predictive power [1].

- Performance Comparison: Compare the explanatory power of the signature model against competing theory-based models (e.g., models based on predefined ROIs from anatomical atlases). A robust SOFM-derived signature should outperform these alternative models in predicting the outcome of interest in validation data [1].

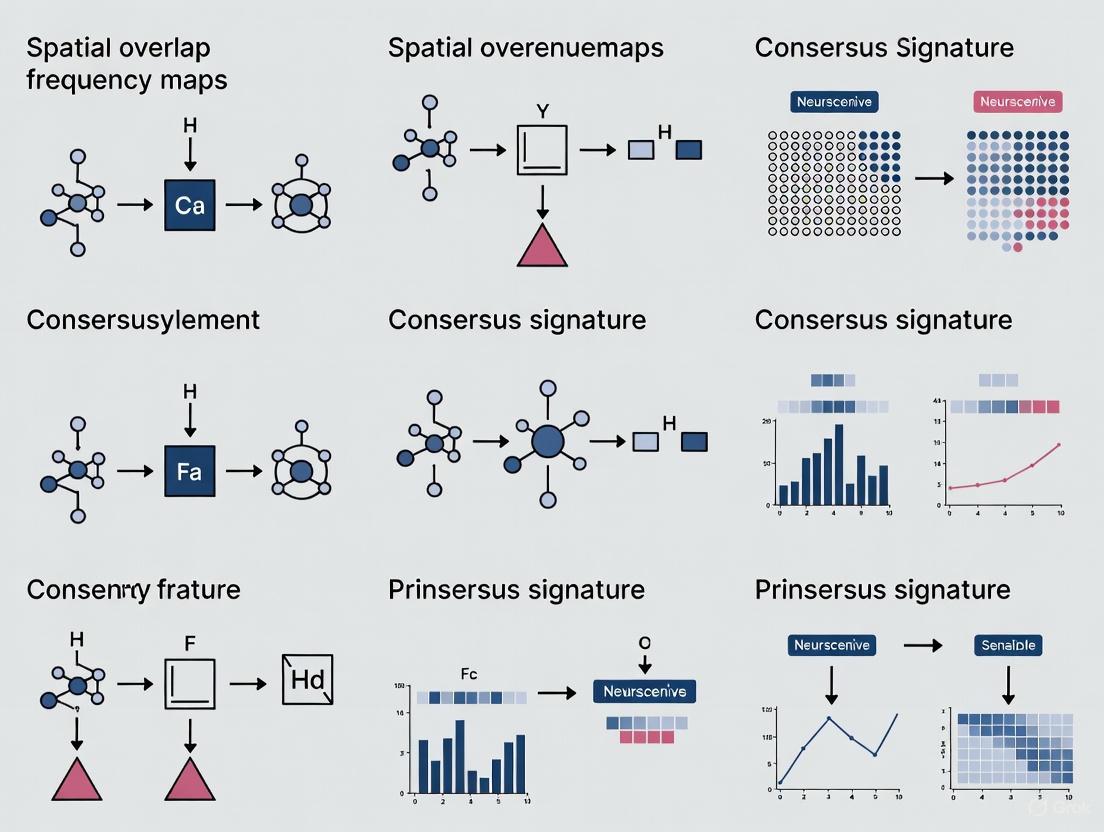

The analytical workflow from the frequency map to a validated model is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the SOFM methodology requires a suite of analytical tools and data resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for SOFM Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in SOFM Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| T1-Weighted MRI Data | Imaging Data | Primary source data for quantifying structural brain features like gray matter thickness. Essential input for the association analysis [1]. |

| Standardized Cognitive Batteries | Behavioral Data | Provides the robust behavioral outcome measures (e.g., memory, executive function) to which brain features are associated. Examples: SENAS, ADAS-Cog [1]. |

| Structural MRI Processing Pipeline | Software Tool | In-house or publicly available pipelines (e.g., based on FSL, FreeSurfer, SPM) for automated steps: brain extraction, tissue segmentation, and spatial registration [1]. |

| High-Performance Computing Cluster | Hardware/Infrastructure | Enables the computationally intensive iterative process of voxel-wise analysis across hundreds of subjects and dozens of random subsets [1]. |

| Voxel-Wise Regression Algorithm | Computational Method | The core statistical engine used in each discovery subset to compute brain-behavior associations at every voxel. Often implemented with mass-univariate models [1]. |

Applications and Strategic Advantages in Drug Development

The SOFM framework offers tangible strategic advantages for the pharmaceutical industry, particularly in the quest for objective, biologically grounded biomarkers.

- Biomarker Development for Clinical Trials: SOFMs can identify robust neuroanatomical signatures for patient stratification, target engagement, and efficacy monitoring in neurological and psychiatric disorders. A validated GM thickness signature for episodic memory could serve as a surrogate endpoint in early-stage Alzheimer's disease trials, potentially reducing trial duration and cost.

- De-risking Target Selection: By providing a more complete accounting of the brain substrates underlying a clinical syndrome, SOFMs can help validate novel drug targets. The consensus nature of the signature increases confidence that a targeted pathway is centrally involved in the disease biology [1].

- Cross-Domain Signature Comparison: The method can be extended to multiple behavioral domains (e.g., memory, everyday function) within the same dataset. This allows researchers to discern and compare brain substrates, revealing shared and unique neural architectures, which can inform drug repurposing and combination therapies [1].

Technical Specifications and Visualization Standards

Effective implementation and communication of SOFM results require adherence to technical and accessibility standards.

- Color Contrast for Accessibility: When creating visualizations of SOFMs and consensus masks, it is critical to ensure sufficient color contrast. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) require a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text or graphical objects [2] [3]. The color palette provided for the diagrams in this document adheres to these principles.

- Spatial Awareness in Visualization: Tools like Spaco, a spatially aware colorization method, can enhance the interpretation of complex spatial data. Spaco uses a "Degree of Interlacement" metric to model topology between categories and optimizes color assignments to maximize perceptual distinction between spatially adjacent features, which is highly relevant for displaying SOFMs on brain surfaces [4].

In the field of high-dimensional biological data analysis, a Consensus Signature (ConSig) refers to a robust molecular signature derived through the aggregation of multiple individual models or data sources. The primary goal of this approach is to overcome the limitations of single, unstable biomarkers by identifying a core set of features that are consistently associated with a biological state or clinical outcome across different methodologies, datasets, or analytical techniques [5]. The concept has emerged as a powerful solution to the pervasive challenge of limited reproducibility in omics-based research, where molecular signatures developed from gene expression profiles often show minimal overlap when applied to similar clinical questions [5] [6]. This lack of concordance can stem from technical variations in platforms, differences in biological samples, or statistical instabilities due to the high dimensionality of omics data combined with small sample sizes [5]. By integrating signals from multiple sources, consensus signatures aim to distill the most biologically relevant and technically reproducible features, thereby enhancing both interpretability and predictive stability.

The fundamental premise of consensus signatures aligns with the broader thesis of spatial overlap frequency maps in biological systems, where coordinated patterns emerge from the integration of multiple information streams. Just as neurons in the visual cortex with similar orientation and spatial frequency tuning exhibit stronger connectivity and form overlapping functional ensembles [7], molecular features that consistently co-occur across multiple analytical frameworks likely represent core components of biological mechanisms. This parallel extends to the concept of population receptive fields in visual neuroscience, where the spatial tuning of neuronal populations reflects the integration of multiple stimulus features [8]. In molecular biology, consensus signatures similarly represent integrated patterns that transcend the noise and variability inherent in individual measurements.

The Critical Need for Consensus Approaches in Biomarker Discovery

The discovery of molecular signatures from omics data holds tremendous promise for personalized medicine, with potential applications in disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection [6]. However, this promise has been hampered by significant challenges in reproducibility and clinical translation. Many reported molecular signatures suffer from limited reproducibility in independent datasets, insufficient sensitivity or specificity for clinical use, and poor generalizability across patient populations [6]. These difficulties can be attributed to several factors:

- Low signal-to-noise ratios inherent in omics datasets

- Batch effects and technical variations in sample processing

- Molecular heterogeneity between samples and within populations

- High dimensionality of data with small sample sizes [6]

These issues are exacerbated by improper study design, inconsistent experimental techniques, and flawed data analysis methodologies [6]. When comparing different gene signatures for related clinical questions, researchers often observe only minimal overlap, making biological interpretation challenging [5]. Network-based consensus signatures address these limitations by functionally mapping seemingly different gene signatures onto protein interaction networks, revealing common upstream regulators and biologically coherent pathways [5].

Table 1: Challenges in Traditional Molecular Signature Discovery

| Challenge | Impact | Consensus Approach Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Limited reproducibility | Poor performance on independent datasets | Aggregation across multiple models and datasets |

| Technical variability | Batch effects and platform differences | Identification of consistent core features |

| Biological heterogeneity | Inconsistent performance across populations | Focus on biologically fundamental pathways |

| High dimensionality | Overfitting and unstable feature selection | Dimensionality reduction through frequency-based selection |

Evaluation across different datasets demonstrates that signatures derived from consensus approaches show much higher stability than signatures learned from all probesets on a microarray, while maintaining comparable predictive performance [5]. Furthermore, these consensus signatures are clearly interpretable in terms of enriched pathways, disease-associated genes, and known drug targets, facilitating biological validation and clinical adoption [5].

Methodological Frameworks for Consensus Signature Development

General Workflow for Consensus Signature Construction

The development of robust consensus signatures follows a systematic process that integrates multiple analytical approaches and validation strategies. The BioDiscML framework exemplifies this approach by generating multiple machine learning models with different signatures and then applying visualization tools like BioDiscViz to identify consensus features through a combination of filters [9]. This process typically involves four key stages:

- Defining the scientific and clinical context for the molecular signature

- Procuring appropriate data from multiple sources or through multiple methodologies

- Performing feature selection and model building across multiple algorithms

- Evaluating the molecular signature on independent datasets [6]

Within this framework, researchers can employ various strategies to generate the initial set of signatures for consensus building. BioDiscML utilizes automatic machine learning to identify biomarker signatures while avoiding overfitting through multiple evaluation strategies, including cross-validation, bootstrapping, and repeated holdout [9]. The tool generates numerous models with different signatures, and despite equivalent performances, often observes inconsistent overlaps between signatures [9]. This observation highlights the fundamental rationale for consensus approaches – different algorithmic approaches may identify different but equally predictive feature sets, with consensus features representing the most robust biomarkers.

Network-Based Consensus Development

An alternative approach to consensus signature development involves mapping seemingly different gene signatures onto protein interaction networks to identify common upstream regulators [5]. This method leverages the biological knowledge embedded in interaction networks to functionally integrate diverse signatures, revealing consensus elements that might not be apparent through direct comparison of gene lists. The resulting network-based consensus signatures serve as prior knowledge for predictive biomarker discovery, yielding signatures with enhanced stability and interpretability [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Consensus Signature Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Aggregation | Combines features from multiple ML models; uses frequency-based selection | Automates discovery; handles high-dimensional data well | May miss biologically relevant but less frequent features |

| Network-Based Integration | Maps signatures to protein interaction networks; identifies upstream regulators | Enhances biological interpretability; reveals functional modules | Dependent on completeness of network knowledge |

| Multifactorial Design | Based on known biological processes; combines surrogate markers | Strong theoretical foundation; clinically relevant | Requires extensive prior biological knowledge |

Multifactorial Consensus Signature Design

A distinct approach to consensus signature development involves the construction of multifactorial signatures based on known biological processes required for a specific cellular function. For example, in triple-negative breast cancer, a consensus signature (ConSig) was designed to predict response to anthracycline-based chemotherapy by incorporating measures of each step required for anthracycline-induced cytotoxicity [10]. This approach included:

- Drug penetration measured by HIF1α or SHARP1 signature

- Nuclear topoisomerase IIα protein location measured by LAPTM4B mRNA

- Increased topoIIα mRNA expression beyond proliferation-related expression

- Apoptosis induction measured by Minimal Gene signature or YWHAZ mRNA

- Immune activation measured by STAT1 signature [10]

The term "Consensus Signature" in this context reflects the concept that each selected component acts as a surrogate marker for different steps in a biological process, working synergistically to provide an overall measure of the function of interest [10]. This methodology differs from data-driven approaches as it incorporates prior biological knowledge into signature design, potentially enhancing clinical relevance and interpretability.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Workflow for Machine Learning-Based Consensus Development

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing consensus signatures using machine learning approaches:

Implementation Protocol for BioDiscML-Based Consensus Signatures

Objective: To identify a robust consensus signature from omics data using automated machine learning and visualization tools.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- BioDiscML software platform

- BioDiscViz visualization tool

- Omics dataset in appropriate format (e.g., gene expression data)

- R statistical environment with required packages (shiny, ggplot2, ComplexHeatmap, FactoExtra, Rtsne, UMAP, UpsetR)

Experimental Procedure:

Data Preparation and Input

- Format input data according to BioDiscML requirements

- Ensure appropriate metadata annotation for sample characteristics

- For genomic data, use HUGO symbols or Entrez IDs for gene identifiers [11]

Model Generation with BioDiscML

- Run BioDiscML with multiple feature selection and classification algorithms

- Apply cross-validation, bootstrapping, and repeated holdout strategies to avoid overfitting [9]

- Generate multiple models with different signature sets

Consensus Identification with BioDiscViz

- Import BioDiscML outputs into BioDiscViz

- Use the "Attribute Distribution" section to visualize frequently used features across classifiers

- Apply filters based on performance metrics (e.g., Matthew's Correlation Coefficient > 0.76, standard deviation of MCC ≤ 0.15) [9]

- Generate consensus signatures from features frequently called by high-performing classifiers

Visualization and Validation

- Create Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots to assess class separation

- Generate t-SNE and UMAP visualizations to evaluate signature performance [9]

- Construct heatmaps using ComplexHeatmap package to visualize expression patterns

- Use UpsetR plots to visualize intersections between features in different classifiers [9]

Performance Evaluation

- Assess consensus signature using Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC)

- Calculate accuracy and area under curve (AUC) metrics

- Compare performance against individual models and previously published signatures

In a demonstration using a colon cancer dataset containing gene expression from 40 tumor and 22 normal colon tissue samples, the consensus signature approach identified features that provided better separation between classes in PCA plots compared to the best single model identified by BioDiscML [9]. The resulting consensus signature contained 3 genes overlapping with the best model signature and 7 newly added genes [9].

Protocol for Network-Based Consensus Signatures

Objective: To construct a consensus signature by mapping seemingly different gene signatures onto protein interaction networks.

Materials:

- Multiple gene signatures for the same clinical question

- Protein-protein interaction network database

- Gene ontology and pathway annotation resources

- Network analysis software (e.g., Cytoscape with appropriate plugins)

Experimental Procedure:

Signature Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect multiple published gene signatures for the clinical condition of interest

- Map gene identifiers to a common nomenclature system

- Identify overlapping and unique genes across signatures

Network Mapping and Analysis

- Map all genes from collected signatures onto a protein interaction network

- Identify common upstream regulators of signature genes

- Determine network proximity between genes from different signatures

Consensus Signature Extraction

- Extract genes that serve as hubs or bottleneck nodes in the integrated network

- Identify functionally coherent modules enriched for signature genes

- Select consensus elements based on network topology and functional annotation

Validation and Evaluation

- Evaluate the predictive performance of network-derived consensus signature

- Compare stability across datasets with original signatures

- Assess biological interpretability through pathway enrichment analysis

Evaluation on different datasets shows that signatures derived from network-based consensus approaches reveal much higher stability than signatures learned from all probesets on a microarray, while maintaining comparable predictive performance [5].

Visualization and Analytical Tools for Consensus Signature Research

The development and interpretation of consensus signatures requires specialized visualization tools to handle the complexity of multi-model analysis and feature aggregation. BioDiscViz represents a dedicated solution for visualizing results from BioDiscML, providing summaries, tables, and graphics including PCA plots, UMAP, t-SNE, heatmaps, and boxplots for the best model and correlated features [9]. This tool specifically provides visual support to extract a consensus signature from BioDiscML models using a combination of filters [9].

The interface of BioDiscViz is divided into several key sections:

- Short Signature: Represents results from the best model of BioDiscML

- Long Signature: Displays correlated features

- Attribute Distribution: Visualizes the most frequently used features by different classifiers

- Consensus Signatures: Provides representation of signatures called by the majority of classifiers based on user-defined parameters [9]

For network-based consensus approaches, tools like Cytoscape enable the visualization of protein interaction networks and the identification of key regulatory nodes that connect multiple signatures [5]. These visualizations help researchers identify biologically plausible consensus elements that might not emerge from purely statistical approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Consensus Signature Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| BioDiscML Platform | Automated machine learning for biomarker signature identification | Identifies multiple model signatures for consensus building [9] |

| BioDiscViz Tool | Visual interactive analysis of ML results and consensus extraction | Generates PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, heatmaps for signature visualization [9] |

| Protein Interaction Networks | Network-based consensus signature development | Maps seemingly different signatures to identify common upstream regulators [5] |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Public repository for omics data procurement | Source of validation datasets for consensus signature evaluation [6] |

| ComplexHeatmap Package | Creation of publication-quality heatmaps | Visualizes expression patterns of consensus signatures [9] |

Case Studies and Applications

Consensus Signature for Anthracycline Response Prediction in Breast Cancer

A compelling application of the consensus signature approach appears in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where researchers developed a multifactorial ConSig to predict response to neoadjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy [10]. The signature was constructed based on five biological processes required for anthracycline function:

- Drug penetration measured by HIF1α or SHARP1 signature

- Nuclear topoIIα protein location measured by LAPTM4B mRNA

- Increased topoIIα mRNA expression measured directly

- Apoptosis induction measured by Minimal Gene signature or YWHAZ mRNA

- Immune activation measured by STAT1 signature [10]

The most powerful predictors were ConSig1 (STAT1 + topoIIα mRNA + LAPTM4B) and ConSig2 (STAT1 + topoIIα mRNA + HIF1α) [10]. ConSig1 demonstrated high negative predictive value (85%) and a high odds ratio for no pathological complete response (3.18), outperforming ConSig2 in validation sets for anthracycline specificity [10]. This approach highlights how consensus signatures built on biological rationale rather than purely statistical correlation can yield clinically useful predictors.

Machine Learning Consensus Signature for Colon Cancer

In a demonstration of the BioDiscML/BioDiscViz pipeline, researchers applied consensus signature methodology to a colon cancer dataset containing gene expression in 40 tumor and 22 normal colon tissue samples [9]. The study identified the top 10 signatures from classifiers that surpassed an MCC threshold of 0.76 with a standard deviation of MCC no greater than 0.15 [9]. The quality of selection was assessed using heatmaps and PCA, which showed better separation between classes than the best model identified by BioDiscML alone [9].

The consensus signature contained 3 genes overlapping with the best model signature and 7 newly added genes [9]. When BioDiscML was run a second time using the full consensus signature without feature selection, the resulting model achieved an MCC of 0.791 (STD 0.032), which was slightly better than the best initial model (MCC 0.776, STD 0.037) [9]. This demonstrates how consensus approaches can not only identify robust signatures but also potentially improve predictive performance.

The following diagram illustrates the biological rationale behind multifactorial consensus signatures:

The consensus signature concept represents a paradigm shift in biomarker discovery, moving from single, unstable signatures to robust, aggregated biomarkers that transcend the limitations of individual approaches. By combining multiple models, data sources, or biological perspectives, consensus approaches address the critical challenges of reproducibility and biological interpretability that have plagued omics-based biomarker research [5] [6]. The methodology aligns with the broader thesis of spatial overlap frequency maps, where coordinated patterns emerge from the integration of multiple information streams, creating functional ensembles that are more than the sum of their parts [7].

As the field advances, consensus signature approaches will likely play an increasingly important role in translational research and clinical applications. These methodologies offer a path toward more reliable, interpretable, and clinically actionable biomarkers that can truly realize the promise of personalized medicine. With further refinement and validation, consensus signatures may become standard tools for drug development, patient stratification, and treatment selection across diverse disease areas.

Spatial overlap frequency maps represent a transformative approach in biomedical science, enabling researchers to quantify the spatial co-patterning of diverse biological features across complex tissues like the human brain. This methodology is pivotal for moving beyond simple correlative observations to establishing consensus signatures that reveal fundamental organizational principles. By mapping multiple data layers—from genetic expression and cellular morphology to microbial presence and neurochemical gradients—onto a common spatial framework, scientists can decode the complex interplay between tissue microstructure, function, and disease pathology. This technical guide examines the cutting-edge application of these spatial mapping techniques across two frontiers: understanding brain-behavior relationships and characterizing the tumor microenvironment of brain cancers, providing detailed methodologies for researchers pursuing integrative spatial analyses.

Brain-Behavior Associations: Mapping the Neurobiological Correlates of Cognition

Experimental Protocol for Large-Scale Vertex-Wise Meta-Analysis

The establishment of robust brain-behavior maps requires a standardized, high-throughput pipeline for processing neuroimaging data and cognitive assessments across multiple cohorts. The following protocol, adapted from recent large-scale studies, details the essential methodology [12].

Participant Cohorts and Cognitive Phenotyping:

- Cohort Selection: Utilize large, population-based cohorts with neuroimaging and cognitive data. A recent study integrated data from UK Biobank (UKB, N=36,744), Generation Scotland (GenScot, N=1,013), and Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (LBC1936), creating a meta-analytic N > 38,000 [12].

- General Cognitive Function (g): Administer a comprehensive cognitive test battery covering multiple domains (e.g., reasoning, memory, processing speed). Calculate

gas the first unrotated principal component or a latent factor from all cognitive tests to represent domain-general cognitive ability [12]. - Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: Exclude participants with neurological conditions (e.g., dementia, Parkinson's disease, stroke, multiple sclerosis, brain cancer/injury) that might confound brain-cognition relationships [12].

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Processing:

- MRI Acquisition: Perform T1-weighted structural MRI using standardized protocols across sites (e.g., UKB: 3T Siemens Skyra scanner) [12].

- Cortical Surface Reconstruction: Process T1-weighted images through automated pipelines (e.g., FreeSurfer) to extract vertex-wise measures of cortical morphology:

- Cortical Volume

- Surface Area

- Cortical Thickness

- Curvature

- Sulcal Depth [12]

- Quality Control: Implement rigorous QC (e.g., FreeSurfer's

qcaching) with exclusion of datasets failing processing steps [12].

Spatial Statistical Analysis and Meta-Analysis:

- Vertex-Wise Analysis: At each of approximately 298,790 cortical vertices, regress each morphometry measure against

g, adjusting for age and sex [12]. - Cross-Cohort Meta-Analysis: Apply fixed-effects meta-analysis to combine vertex-wise effect sizes (β) and p-values across all cohorts for each morphometry measure [12].

- Spatial Correlation Analysis: Register meta-analysis results and 33 neurobiological maps to a common cortical surface template (fsaverage). Calculate spatial correlations between g-morphometry maps and neurobiological maps at both whole-cortex and regional (Desikan-Killiany atlas) levels [12].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from g-Morphometry Spatial Analysis

| Morphometry Measure | β Range Across Cortex | Strongest Association Regions | Cross-Cohort Spatial Correlation (mean r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Volume | -0.12 to 0.17 | Frontoparietal Network | 0.57 (SD=0.18) |

| Surface Area | -0.10 to 0.15 | Prefrontal and Temporal | 0.59 (SD=0.16) |

| Cortical Thickness | -0.09 to 0.13 | Anterior Cingulate | 0.55 (SD=0.17) |

| Curvature | -0.08 to 0.11 | Insular and Parietal | 0.54 (SD=0.19) |

| Sulcal Depth | -0.11 to 0.12 | Frontal and Temporal Sulci | 0.56 (SD=0.17) |

Neurobiological Profiling and Multidimensional Cortical Organization

Beyond establishing brain-behavior maps, the critical next step involves decoding their neurobiological significance through spatial concordance analysis with fundamental cortical properties [12].

Neurobiological Data Integration:

- Data Compilation: Assemble open-source cortical maps of 33 neurobiological properties from multiple modalities:

- Neurotransmitter Receptors: Densities of serotonin, dopamine, GABA, glutamate, etc.

- Gene Expression: Transcriptomic profiles from the Allen Human Brain Atlas

- Metabolic Profiles: Glucose metabolism and aerobic glycolysis rates

- Microstructural Properties: Cytoarchitectural similarity, myelin mapping, cortical hierarchy [12]

- Spatial Registration: All maps must be registered to the same common cortical space (e.g., fsaverage 164k) for direct quantitative comparison [12].

Multidimensional Cortical Analysis:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the 33 neurobiological maps to identify major dimensions of cortical organization [12].

- Spatial Concordance Testing: Calculate spatial correlations between g-morphometry association maps and both individual neurobiological maps and the derived principal components [12].

- Spin-Test Validation: Use spatial permutation testing (spin tests) to assess statistical significance of spatial correlations while accounting for spatial autocorrelation [12].

Table 2: Principal Components of Cortical Organization and Their g-Morphometry Correlations

| Principal Component | Variance Explained | Key Neurobiological Features | Spatial Correlation with g-Volume (⎸r⎸) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 38.2% | Neurotransmitter receptor densities, Gene expression | 0.55 (p_spin < 0.05) |

| PC2 | 15.7% | Metabolic profiles, Functional connectivity | 0.42 (p_spin < 0.05) |

| PC3 | 7.4% | Cytoarchitectural similarity, Myelination | 0.33 (p_spin < 0.05) |

| PC4 | 4.8% | Evolutionary expansion, Cortical hierarchy | 0.22 (p_spin < 0.05) |

Brain-Behavior Mapping Workflow

Tumor Microenvironment Mapping: Microbial Signals in Brain Tumors

Experimental Protocol for Detecting Intratumoral Microbial Elements

The investigation of microbial components within brain tumors requires a multi-modal approach to overcome challenges of low biomass and potential contamination. This protocol details the rigorous methodology for spatial mapping of bacterial elements in glioma and brain metastases [13].

Study Design and Sample Collection:

- Cohort Design: Prospective, multi-institutional study design with 243 tissue samples from 221 patients (168 tumor: 113 glioma, 55 brain metastases; 75 non-cancerous controls) [13].

- Sample Types: Collect tumor tissues, normal adjacent tissues (NAT), and non-cancerous brain tissues. When sufficient material is available, analyze tumor samples using at least two methodological categories (visualization, sequencing, culturomics) [13].

- Sample Processing: Implement stringent pre-analytical processing protocols to minimize exogenous contamination, including dedicated workspace, negative controls, and reagent validation [13].

Spatial Detection of Bacterial Elements:

- RNAScope FISH: Perform fluorescence in situ hybridization using validated 16S rRNA pan-bacterial probes with negative control probe. Conduct z-stack imaging to determine intracellular localization. Co-stain with cell-type markers (GFAP for glioma, pan-cytokeratin for brain metastases) [13].

- Immunohistochemistry: Perform LPS (lipopolysaccharide) staining on consecutive tissue sections to those used for 16S rRNA FISH to detect bacterial membrane components [13].

- Image Analysis: Use high-resolution spatial imaging and confocal microscopy to characterize bacterial signal size, morphology, and distribution patterns (intact bacteria ~2μm vs. punctate patterns) [13].

Molecular and Bioinformatic Characterization:

- 16S rRNA Sequencing: Implement custom 16S sequencing workflows with strict negative controls and contamination-aware bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., Decontam) [13].

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Apply low-biomass-optimized metagenomic sequencing protocols with orthogonal validation [13].

- Spatial Molecular Profiling: Perform digital spatial profiling (DSP) and spatial transcriptomics to correlate bacterial signals with host immune and metabolic responses [13].

- Culturomics: Attempt bacterial culture using multiple media and conditions, though standard methods may not yield readily cultivable microbiota from brain tumors [13].

Table 3: Detection Frequency of Bacterial Elements Across Brain Tumor Types

| Detection Method | Glioma (n=15) | Brain Metastases (n=15) | Non-Cancerous Controls | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA FISH | 11/15 (73.3%) | 9/15 (60%) | Not detected | Intracellular localization; varied morphology |

| LPS IHC | 13/15 (86.7%) | 9/15 (60%) | Not reported | Concordant with 16S in 22/30 samples |

| 16S Sequencing | Signal detected | Signal detected | Signal absent | Taxonomic associations identified |

| Bacterial Culture | Not cultivable | Not cultivable | Not applicable | Suggests non-viable or fastidious bacteria |

Spatial Correlation Analysis and Functional Implications

The functional significance of intratumoral bacterial elements emerges through their spatial relationships with host tumor microenvironment components [13].

Spatial Correlation Mapping:

- Regional Analysis: Divide tumor sections into regions of interest (ROIs) and quantify bacterial 16S signals alongside molecular markers [13].

- Neighborhood Analysis: Apply spatial neighborhood analysis to characterize cellular communities containing bacterial signals [13].

- Single-Cell Correlation: Perform high-resolution spatial imaging to correlate bacterial signals with specific cell types (tumor cells, immune cells, stromal cells) [13].

Multi-Omic Integration:

- Immunoprofilng: Integrate bacterial signal data with immune cell infiltration patterns (T cells, macrophages, microglia) [13].

- Metabolic Profiling: Correlate bacterial signals with metabolic pathway activities through spatial transcriptomics and metabolomics [13].

- Antimicrobial Signatures: Analyze expression of antimicrobial response genes in regions with high bacterial signals [13].

Cross-Microbiome Integration:

- Oral and Gut Microbiome Comparison: Compare intratumoral bacterial sequences with matched oral and gut microbiota from the same patients to identify potential origins [13].

- Bioinformatic Pipeline: Use stringent sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis to establish connections between intratumoral and distant microbial communities [13].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Brain Tumor Microenvironment Mapping

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Detection | RNAScope 16S rRNA pan-bacterial probes, LPS antibodies | Detection of bacterial RNA and membrane components | Intracellular localization requires z-stack imaging; consecutive sections for correlation |

| Cell Type Markers | GFAP (glioma), Pan-cytokeratin (metastases), Iba1 (microglia), CD45 (immune cells) | Cell-type specific localization of bacterial signals | Multiplexing enables cellular context determination |

| Sequencing Tools | Custom 16S sequencing panels, Metagenomic sequencing kits | Taxonomic characterization of low-biomass samples | Contamination-aware bioinformatics essential |

| Spatial Profiling | Digital Spatial Profiling (DSP) panels, Spatial transcriptomics kits | Correlation of bacterial signals with host gene expression | Preserve spatial information while extracting nucleic acids |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Decontam, Phyloseq, METAGENassist, Spatial analysis packages | Analysis of low-biomass microbiome data, Spatial correlation | Rigorous negative control inclusion and statistical correction |

Tumor Microbe Mapping Pipeline

Integrated Analytical Framework for Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps

The convergence of brain-behavior mapping and tumor microenvironment analysis reveals powerful consensus principles for spatial biology research. Both applications demonstrate that meaningful biological insights emerge from quantifying the spatial co-patterning of multiple data layers registered to a common coordinate system.

Consensus Signatures in Spatial Analysis:

- Multi-Modal Registration: Successful spatial mapping requires precise registration of diverse data types (imaging, molecular, microbial) to a common spatial framework [13] [12].

- Dimensionality Reduction: High-dimensional spatial data benefits from decomposition into major organizational components that capture conserved biological axes [12].

- Cross-Validation: Spatial findings require validation through multiple orthogonal methods (e.g., FISH plus IHC plus sequencing) to establish robustness [13].

- Functional Interpretation: Spatial correlations gain biological meaning when connected to functional pathways (immunometabolic programs, cognitive processes) through integrated analysis [13] [12].

This integrated framework demonstrates that spatial overlap frequency maps provide a powerful mathematical foundation for identifying consensus signatures that transcend individual studies or methodologies, ultimately revealing fundamental principles of brain organization and pathology.

Overcoming the Limitations of Predefined Atlas Regions and Single-Discovery Sets

In the field of spatial biology, research has been fundamentally constrained by two persistent methodological limitations: the use of predefined atlas regions and reliance on single-discovery datasets. Predefined anatomical parcellations often fail to capture biologically meaningful boundaries that emerge from molecular data, potentially obscuring critical patterns of cellular organization and interaction. Simultaneously, single-study datasets suffer from limited statistical power, cohort-specific biases, and an inability to identify rare cell types or consistent spatial patterns across diverse populations. These constraints are particularly problematic in the context of spatial overlap frequency maps consensus signature research, which aims to identify robust, spatially conserved biological signals across multiple studies and conditions.

Recent technological advances in spatial transcriptomics and computational integration methods now provide pathways to overcome these limitations. This technical guide outlines validated methodologies for creating comprehensive spatial atlas frameworks that transcend traditional anatomical boundaries and synthesize information across multiple discovery sets, enabling the identification of consensus biological signatures with greater statistical confidence and biological relevance.

Integrative Computational Frameworks

Machine Learning-Driven Atlas Construction

The creation of spatially-resolved tissue atlases no longer needs to be constrained by classical anatomical boundaries. Machine learning approaches now enable the identification of molecularly defined regions based on intrinsic gene expression patterns rather than predetermined anatomical coordinates.

Reference-Based Integration Pipelines: The Brain Cell Atlas demonstrates the power of using machine learning algorithms to harmonize cell type annotations across multiple datasets. By employing seven well-established reference-based machine learning methods plus a hierarchical annotation workflow (scAnnot), this approach achieved a 98% average accuracy in cell type prediction across integrated datasets [14]. The scAnnot workflow utilizes a Variational Autoencoder model from scANVI (single-cell Annotation using Variational Inference) to train models at different resolutions, applying them in a hierarchical structure to achieve multi-granularity cell type annotation [14].

Spatial Mapping Validation: In developing a spatial single-cell atlas of the human lung, researchers applied three complementary spatial transcriptomics approaches - HybISS, SCRINSHOT, and Visium - to overcome the limitations of any single technology [15]. This multi-modal validation confirmed cell type localizations and revealed consistent anatomical and regional gene expression variability across 35 identified cell types [15].

Consensus Signature Identification Through Cross-Study Integration

The integration of atlas-level single-cell data presents unprecedented opportunities to reveal rare cell types and cellular heterogeneity across regions and conditions. The Brain Cell Atlas exemplifies this approach by assembling single-cell data from 70 human and 103 mouse studies, encompassing over 26.3 million cells or nuclei from both healthy and diseased tissues across major developmental stages and brain regions [14].

Table 1: Cross-Study Integration Metrics from the Brain Cell Atlas

| Integration Parameter | Human Data | Mouse Data |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Studies Integrated | 70 | 103 |

| Total Cells/Nuclei | 11.3 million | 15 million |

| Sample Count | 6,577 samples | 25,710 samples |

| Major Brain Regions Covered | 14 main regions, 30 subregions | Comprehensive coverage |

| Technology Platform | 94.8% using 10x Chromium | Multiple platforms |

| Developmental Span | 6 gestational weeks to >80 years | Multiple stages |

This massive integration enabled the identification of putative neural progenitor cells in adult hippocampus and a distinct subpopulation of PCDH9-high microglia, demonstrating how rare cell populations can be discovered through cross-study consensus [14]. The resource further elucidated gene regulatory differences of these microglia between hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, revealing region-specific functionalities through consensus mapping [14].

Methodological Protocols for Spatial Consensus Mapping

Experimental Workflows for Multi-Scale Spatial Data Generation

Implementing robust spatial consensus mapping requires standardized experimental workflows that maintain data quality while enabling cross-study comparisons. The following workflow has been validated in large-scale spatial atlas projects:

Tissue Processing and Quality Control Protocol:

- Collect tissue samples targeting discrete anatomical regions congruent with previously described cell locations in scRNA-seq datasets [15].

- Subject samples to mRNA quality controls to reject samples with low or diffuse RNA signal [15].

- Process high-quality samples from different locations with complementary spatially-resolved transcriptomic (SRT) technologies [15].

- For HybISS: Generate a probe panel based on previously published scRNA-seq data using Spapros to detect most cell types and states [15].

- For SCRINSHOT: Employ a pre-validated gene panel of major cell type markers and genes showing intra-cluster gene expression variation for detecting particular cell states [15].

- Include untargeted SRT method (e.g., Visium) on serial sections to validate probe panels and method performance [15].

Multi-Technology Integration Validation: Visual cross-validation of serial tissue sections processed with all three methods demonstrates consistent marker gene expression patterns and confirms performance of targeted methods [15].

Computational Pipeline for Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps

The creation of spatial overlap frequency maps consensus signatures requires specialized computational approaches that can handle multi-scale, multi-study data while preserving spatial context.

Meta-Analytic Vertex-Wise Association Protocol: For analyzing associations between general cognitive functioning (g) and cortical morphometry, a large-scale vertex-wise analysis was conducted across 3 cohorts with 5 morphometry measures (volume, surface area, thickness, curvature, and sulcal depth) with a meta-analytic N = 38,379 [12]. This approach:

- Calculated associations between general cognitive functioning (g) and 5 measures of vertex-wise morphometry across multiple cohorts [12]

- Registered all data to a common brain space (fsaverage 164k space) for cross-cohort comparability [12]

- Tested spatial concordance between g-morphometry associations and 33 neurobiological cortical profiles [12]

- Identified four principal components explaining 66.1% of variance across 33 neurobiological maps [12]

- Reported spatial correlations between these fundamental brain organization dimensions and g-morphometry cortical profiles [12]

Spatial Correlation and Consensus Identification: This protocol goes beyond cortex-level spatial correlations to include regional-level spatial correlations using established anatomical atlases (e.g., Desikan-Killiany atlas with 34 left/right paired cortical regions), providing nuanced information about relative strengths of spatial correlations in different regions and homogeneity of co-patterning across regions [12].

Table 2: Spatial Analysis Metrics from Large-Scale Brain Mapping

| Analysis Dimension | Scale/Resolution | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Morphometry Measures | 5 measures: volume, surface area, thickness, curvature, sulcal depth | β range = -0.12 to 0.17 across morphometry measures |

| Cross-Cohort Agreement | 3 cohorts: UKB, GenScot, LBC1936 | Mean spatial correlation r = 0.57, SD = 0.18 |

| Cortical Coverage | 298,790 cortical vertices | Comprehensive vertex-wise analysis |

| Neurobiological Profiles | 33 profiles from multiple modalities | Four major dimensions explaining 66.1% of variance |

| Spatial Correlation with g | Cortex-wide and within-region | p_spin < 0.05 |r| range = 0.22 to 0.55 |

Analytical Framework for Consensus Signature Extraction

Spatial Overlap Frequency Mapping Algorithm

The core innovation in overcoming predefined atlas limitations lies in the spatial overlap frequency mapping approach, which identifies regions of consistent biological significance across multiple studies and conditions.

Multi-Dimensional Spatial Correlation Analysis: This methodology tests how brain regions associated with a specific phenotype (e.g., general cognitive function) are spatially correlated with the patterning of multiple neurobiological properties across the human cerebral cortex [12]. The protocol involves:

- Assembling open-source brain maps and deriving novel ones registered to the same common brain space as meta-analytic results [12]

- Quantitatively testing spatial concordance between phenotype-morphometry associations and cortical profiles of neurobiological properties [12]

- Identifying principal components that explain majority of variance across multiple neurobiological maps [12]

- Testing associations between these fundamental brain organization dimensions and phenotype-morphometry cortical profiles [12]

Hierarchical Cell Type Annotation and Rare Population Identification

The scAnnot hierarchical cell annotation workflow represents a significant advancement for achieving multi-granularity cell type annotation across integrated datasets. This approach:

- Uses a Variational Autoencoder model from scANVI (single-cell ANnotation using Variational Inference) [14]

- Trains machine learning models at different resolutions (granularities) [14]

- Applies these models in a hierarchical structure [14]

- Selects 200 feature genes for each cell type-trained machine learning model with different hyperparameters [14]

- Predicts the harmonized latent space of the cells for cell type label inference [14]

This hierarchical classification approach can further identify subpopulations at second-level annotation with finer granularity, enabling discovery of rare cell populations like putative neural progenitor cells in adult hippocampus and PCDH9-high microglia subpopulations [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Consensus Mapping

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| HybISS | Highly-multiplexed imaging-based spatial transcriptomics with cellular resolution | Targeted detection of majority of cell types in tissue topography [15] |

| SCRINSHOT | Highly-sensitive spatial transcriptomics for limited cell types and states | Detection of cell states by variations in gene expression levels [15] |

| Visium | Untargeted method of mRNA detection with lower spatial resolution | Validation of cell types and regional gene expression patterns [15] |

| Spapros | Probe panel generation for targeted spatial transcriptomics | Creating gene panels based on previously published scRNA-seq data [15] |

| scAnnot | Hierarchical cell annotation workflow based on Variational Autoencoder model | Multi-granularity cell type annotation across integrated datasets [14] |

| Urban Institute R Theme (urbnthemes) | R package for standardized data visualization | Creating publication-ready graphics that meet style guidelines [16] |

| Stereoscope Method | Deconvolution of cell type composition from spatial data | Analyzing Visium-processed serial sections for cell type composition [15] |

Validation and Application in Disease Contexts

The utility of spatial consensus mapping is particularly evident in disease contexts, where it can reveal previously unknown imbalances in cellular compositions. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the topographic atlas approach enabled precise description of characteristic regional cellular responses upon experimental perturbations and during disease progression, defining previously unknown imbalances of epithelial cell type compositions in COPD lungs [15].

The application of these methods to diseased samples demonstrates how the healthy atlas can define aberrant disease-associated cellular neighborhoods affected by immune cell composition and tissue remodeling [15]. This approach has revealed both cellular and neighborhood changes in samples from stage-II COPD patients, uncovering distinct cellular niches at early stages of disease progression [15].

For the brain, these integrative approaches provide a compendium of cortex-wide and within-region spatial correlations among general and specific facets of brain cortical organization and higher order cognitive functioning, serving as a framework for analyzing other aspects of behavior-brain MRI associations [12].

The Critical Link Between Consensus Signatures and Causal Target Identification

The identification of robust molecular signatures represents a pivotal challenge in modern bioinformatics and drug discovery. Traditional approaches have predominantly relied on correlative models, matching gene identities between experimental signatures to infer functional relationships. However, these methods often fail to capture the underlying biological causality, limiting their predictive power and clinical utility. The emergence of consensus signatures—integrated molecular profiles derived from multiple data sources or methodologies—provides a powerful framework for addressing this limitation. When analyzed through advanced causal inference algorithms, these consensus signatures enable researchers to move beyond mere association and toward genuine causal target identification. This paradigm shift is particularly relevant in the context of spatial overlap frequency maps, where consensus signatures can reveal how molecular interactions are organized and regulated within specific cellular and tissue contexts. This technical guide explores the methodological foundation, experimental validation, and practical application of consensus signatures for causal target discovery, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for advancing their investigative workflows.

Theoretical Foundation: Consensus Signatures and Causal Inference

The Concept of Consensus in Molecular Signatures

A consensus signature represents a harmonized molecular profile derived through the integration of multiple distinct but complementary data sources or analytical approaches. Unlike single-method signatures that may capture only partial biological truth, consensus signatures aggregate signals across platforms, experiments, or methodologies to create a more robust and reliable representation of underlying biology. The fundamental strength of this approach lies in its ability to amplify consistent signals while dampening technique-specific noise or bias. In practical terms, consensus signatures can be generated through various computational strategies, including:

- Meta-analysis integration: Combining results from multiple independent studies investigating similar biological conditions

- Multi-omics fusion: Integrating data across genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic platforms

- Methodological consensus: Aggregating results obtained through different analytical pipelines or algorithms applied to the same underlying dataset

The application of consensus signatures is particularly powerful in the context of spatial biology, where spatial overlap frequency maps provide a physical framework for understanding how molecular interactions are organized within tissue architecture. These maps allow researchers to identify co-localization patterns between gene products, signaling molecules, and cellular structures, creating a spatial context for interpreting consensus signatures [7] [8].

Causal Structure Learning in Genomics

Causal structure learning represents a paradigm shift from traditional associative analyses toward understanding directional relationships within biological systems. Where conventional methods identify correlations between molecular features, causal learning aims to reconstruct the directional networks that underlie these associations. The mathematical foundation for this approach relies on Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), which represent causal relationships between variables while prohibiting cyclic connections that would create logical paradoxes [17].

In a DAG, variables (such as gene expression levels) are represented as vertices, and causal relationships are represented as directed edges between these vertices. The key Markov property of DAGs enables factorization of the joint probability distribution into conditional distributions of each variable given its causal parents:

fΣ(X1,...,Xp) = ∏ i=1 p f(Xi | Xpai)

This factorization is fundamental to causal inference because it allows researchers to distinguish direct causal effects from indirect associations mediated through other variables. For genomic applications, causal structure learning faces the challenge of Markov equivalence, where multiple different DAGs can represent the same set of conditional independence relationships. This limitation is addressed through the construction of Completed Partially Directed Acyclic Graphs (CPDAGs), which represent the Markov equivalence class of DAGs consistent with the observed data [17].

Methodological Framework: Integrating Consensus Signatures with Causal Discovery

Functional Representation of Gene Signatures (FRoGS)

The Functional Representation of Gene Signatures (FRoGS) approach addresses a critical limitation in traditional gene signature analysis: the treatment of genes as discrete identifiers rather than functional units. Inspired by word-embedding technologies in natural language processing (such as word2vec), FRoGS projects gene signatures onto a high-dimensional functional space where proximity reflects biological similarity rather than simple identity matching [18].

The FRoGS methodology involves:

Training functional embeddings: A deep learning model is trained to map individual human genes into coordinates that encode their biological functions based on Gene Ontology (GO) annotations and empirical expression profiles from resources like ARCHS4.

Signature aggregation: Vectors associated with individual gene members are aggregated into a single vector representing the entire gene set signature.

Similarity computation: A Siamese neural network model computes similarity between signature vectors representing different perturbations (e.g., compound treatment and genetic modulation).

This approach demonstrates significantly enhanced sensitivity in detecting weak pathway signals compared to traditional identity-based methods. In simulation studies, FRoGS maintained superior performance across a range of signal strengths (parameterized by λ, the number of pathway genes), particularly under conditions of weak signal (λ = 5) where traditional methods like Fisher's exact test showed limited sensitivity [18].

Causal Structure Learning for Prognostic Signatures

The integration of causal structure learning with consensus signature analysis enables the identification of prognostic gene signatures with direct implications for therapeutic development. The methodological workflow involves several distinct phases [17]:

Table 1: Key Stages in Causal Structure Learning for Prognostic Signatures

| Stage | Description | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Graph Construction | Begin with a completely connected graph where all genes are interconnected | Undirected graph skeleton |

| Edge Thinning | Iteratively remove edges by testing conditional independences | Skeleton with reduced edges |

| V-structure Identification | Detect causal motifs where two genes point to a common descendant | Partially directed graph |

| CPDAG Construction | Represent Markov equivalence class of DAGs | Completed PDAG |

| Module Definition | Define gene-specific modules containing each gene and its regulators | Causal modules |

| Survival Integration | Correlate modules with survival times using Cox models | Prognostic gene rankings |

This approach was successfully applied to clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), identifying significant gene modules in the ETS and Notch families, along with genes ARID1A and SMARCA4, which were subsequently validated in independent studies [17].

Experimental Workflow for Causal Target Identification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for combining consensus signatures with causal target identification:

Integrated Workflow for Causal Target Identification

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Comparative Performance of Signature Analysis Methods

Rigorous evaluation of method performance is essential for selecting appropriate analytical strategies. The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of different gene signature analysis methods based on simulation studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Gene Signature Analysis Methods Under Varying Signal Strengths

| Method | Core Principle | Weak Signal (λ=5) | Medium Signal (λ=10) | Strong Signal (λ=15) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRoGS | Functional embedding | -log(p) = 85.2 | -log(p) = 142.7 | -log(p) = 178.9 | [18] |

| OPA2Vec | Ontology-based embedding | -log(p) = 72.4 | -log(p) = 125.3 | -log(p) = 162.1 | [18] |

| Gene2vec | Co-expression embedding | -log(p) = 68.9 | -log(p) = 118.7 | -log(p) = 155.4 | [18] |

| clusDCA | Network embedding | -log(p) = 65.3 | -log(p) = 112.5 | -log(p) = 148.9 | [18] |

| Fisher's Exact Test | Identity-based overlap | -log(p) = 42.1 | -log(p) = 98.7 | -log(p) = 145.2 | [18] |

Performance was measured by the ability to distinguish foreground gene signature pairs (simulating co-targeting perturbations) from foreground-background pairs. Higher -log(p) values indicate better performance. Results are averaged across 200 simulations for 460 human Reactome pathways [18].

Application-Specific Performance Metrics

In applied contexts, different performance metrics become relevant depending on the specific research goals:

Table 3: Application-Specific Performance Metrics for Causal Signature Methods

| Application Context | Key Performance Indicators | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Target Prediction | Area under precision-recall curve (AUPRC) | FRoGS: 0.42 vs. Baseline: 0.31 | [18] |

| Survival Prognostication | Hazard ratio significance | 32% increase in significant prognostic genes | [17] |

| Pathway Signal Detection | Sensitivity at 5% FDR | 68% vs. 42% for identity-based methods | [18] |

| Spatial Co-localization | Population receptive field modulation | Significant pRF size changes post-adaptation (p<0.01) | [8] |

The application of FRoGS to the Broad Institute's L1000 dataset demonstrated substantial improvement in compound-target prediction accuracy compared to identity-based models. When integrated with additional pharmacological activity data sources, FRoGS significantly increased the number of high-quality compound-target predictions, many of which were supported by subsequent experimental validation [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for FRoGS Implementation

The Functional Representation of Gene Signatures approach requires careful implementation to ensure reproducible results:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Collect gene expression profiles from perturbation experiments (e.g., LINCS L1000 dataset)

- Obtain functional annotations from Gene Ontology and pathway databases

- Normalize expression data using robust multi-array average (RMA) or similar methods

- Handle missing data through appropriate imputation techniques

Model Training and Validation

- Initialize neural network with appropriate architecture (typically 3-5 hidden layers)

- Train model to optimize functional similarity preservation

- Validate embedding quality through t-SNE visualization and functional enrichment analysis

- Assess robustness through cross-validation and bootstrap resampling

Signature Comparison and Application

- Aggregate gene vectors into signature representations using appropriate pooling operations

- Compute signature similarities using cosine similarity or related metrics

- Apply to target prediction through Siamese network architecture

- Validate predictions against known compound-target pairs and experimental data

This protocol has been successfully applied to drug target prediction, significantly outperforming models based solely on gene identities [18].

Protocol for Causal Structure Learning

The implementation of causal structure learning for prognostic signature identification follows a rigorous statistical framework:

Initial Graph Construction

- Begin with a completely connected graph encompassing all genes of interest

- Represent genes as vertices and potential regulatory relationships as edges

Conditional Independence Testing

- Iteratively test conditional independences using Gaussian conditional dependence tests

- Remove edges where conditional independence is established

- Control false discovery rates through multiple testing correction

Causal Directionality Determination

- Identify v-structures (i → k ← j) where i and j are not connected

- Propagate orientation constraints to determine additional edge directions

- Represent uncertainty in direction through CPDAG construction

Survival Integration

- Construct gene-specific modules containing each gene and its causal parents

- Fit Cox proportional hazards models for each module

- Estimate effect sizes while adjusting for causal structure

- Rank genes based on minimum effect size across equivalent structures

This approach has been successfully applied to kidney cancer data, identifying novel prognostic genes while confirming established findings [17].

Successful implementation of consensus signature analysis for causal target identification requires leveraging specialized research resources and reagents:

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Consensus Signature and Causal Target Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Databases | LINCS L1000, NCBI GEO, ArrayExpress | Provide perturbation response data for signature generation | Publicly available repositories [6] [18] |

| Functional Annotation Resources | Gene Ontology, Reactome, KEGG | Enable functional embedding of gene signatures | Publicly available knowledgebases [18] |

| Causal Inference Software | PC Algorithm, IDA, CausalMGM | Implement causal structure learning from observational data | Open-source implementations [17] |

| Spatial Mapping Tools | Population Receptive Field (pRF) mapping | Characterize spatial organization of molecular interactions | Custom MATLAB/Python implementations [8] |

| Validation Platforms | CRISPR screening, compound profiling | Experimentally validate computational predictions | Available through core facilities or commercial providers |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Networks

The application of consensus signatures and causal inference methods has revealed several key signaling pathways with importance for therapeutic development:

Key Causal Pathways Identified Through Consensus Signatures

The integration of consensus signatures with causal inference frameworks represents a transformative approach to target identification in biomedical research. By moving beyond correlative associations to establish causal relationships, these methods enable more accurate prediction of therapeutic targets and prognostic biomarkers. The functional embedding approach exemplified by FRoGS addresses fundamental limitations of traditional identity-based signature comparisons, while causal structure learning provides a principled framework for distinguishing direct effects from indirect associations.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on several key areas:

- Multi-modal integration: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and spatial data within unified causal frameworks

- Temporal dynamics: Incorporating time-series data to establish temporal precedence in causal relationships

- Single-cell resolution: Applying causal inference methods to single-cell data to resolve cellular heterogeneity

- Clinical translation: Streamlining workflows for clinical application in personalized medicine and therapeutic development

As these methodologies continue to mature, they hold exceptional promise for accelerating the discovery of causal disease mechanisms and effective therapeutic interventions across diverse pathological conditions.

Building Consensus: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Generating and Applying Spatial Signatures

The emergence of spatial transcriptomics (ST) has revolutionized biological research by enabling high-throughput quantification of gene expression within the intact spatial context of tissues. However, a single two-dimensional (2D) ST slice captures only a fragment of the complete tissue architecture, limiting comprehensive analysis of biological systems. To overcome this limitation, researchers must integrate multiple spatial transcriptomics datasets collected across different technological platforms, biological conditions, or serial tissue sections. This integration process faces significant challenges due to tissue heterogeneity, technical variability across platforms, spatial warping, and differences in experimental protocols. The alignment and integration of these diverse datasets are crucial for robust statistical power and for capturing a holistic view of cellular organization, interactions, and spatial gene expression gradients that cannot be observed in isolated 2D slices [19].

Within the context of spatial overlap frequency maps consensus signature research, data preparation takes on additional importance. This methodology involves computing data-driven signatures of behavioral outcomes or disease states that are robust across validation cohorts. The approach identifies "statistical regions of interest" (sROIs) or brain "signature regions" most associated with specific outcomes through exploratory feature selection. To be a robust brain measure, a signature requires rigorous validation of model performance across diverse cohorts, demonstrating both model fit replicability and spatial extent consistency across multiple datasets beyond the discovery set. This validation is essential for producing reliable and useful phenotypic measures for modeling substrates of behavioral domains or disease progression [1].

Methodological Frameworks for Data Alignment and Integration

Categories of Computational Approaches

The computational challenge of aligning and integrating multiple spatial transcriptomics datasets has prompted the development of numerous sophisticated tools. Based on their underlying methodologies, these approaches can be broadly categorized into three groups: statistical mapping, image processing and registration, and graph-based methods [19].

Statistical mapping approaches often employ Bayesian inference, cluster-aware methods, or optimal transport to align spatial datasets. For instance, PASTE (Probability Alignment of Spatial Transcriptomics Experiments) applies optimal transport to align different slices, while PRECAST employs a cluster-aware method for spatial clustering and profiling. These methods generally work well for homogeneous datasets with similar structures [19].

Image processing and registration methods leverage computer vision techniques for alignment. STIM (Spatial Transcriptomics Imaging Framework), built on scalable ImgLib2 and BigDataViewer frameworks, enables interactive visualization, 3D rendering, and automatic registration of spatial sequencing data. STalign performs landmark-free alignment for cell-type identification and 3D mapping, while STUtility offers landmark-based alignment for spatial clustering and profiling [19] [20].