Statistical Validation of Pairwise and High-Order Brain Connectivity: Methods, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the statistical validation of brain functional connectivity.

Statistical Validation of Pairwise and High-Order Brain Connectivity: Methods, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the statistical validation of brain functional connectivity. It covers the foundational shift from traditional pairwise analysis to high-order interaction models that capture complex, synergistic brain dynamics. The content details rigorous methodological frameworks, including surrogate data and bootstrap analyses for single-subject significance testing, essential for clinical applications. It addresses common pitfalls in connectivity analysis and offers optimization strategies to enhance robustness. Furthermore, the article explores the translation of these validated connectivity biomarkers into drug development pipelines, discussing their growing role in pharmacodynamic assessments and clinical trials for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

From Pairwise Links to High-Order Networks: Uncovering the Brain's Complex Dialogue

The Fundamental Limitation of Pairwise Connectivity

Functional connectivity (FC) mapping has become a fundamental tool in network neuroscience for investigating the brain's functional organization. Traditional models predominantly represent brain activity as a network of pairwise interactions between brain regions, typically using measures like Pearson's correlation or partial correlation [1] [2]. While these approaches have revealed fundamental insights into brain organization, they operate under a limiting constraint: the assumption that all interactions between brain regions can be decomposed into dyadic relationships [1] [3]. This perspective inherently neglects the possibility of higher-order interactions (HOIs) that simultaneously involve three or more brain regions [1] [3].

Mounting theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that the brain's complex functional architecture cannot be fully captured by pairwise statistics alone. Higher-order interactions appear to be fundamental components of complexity and functional integration in brain networks, potentially linked to emergent mental phenomena and consciousness [3]. At both micro- and macro-scales, studies indicate that significant information may be detectable only in joint probability distributions and not in pairwise marginals, meaning pairwise approaches may fail to identify crucial higher-order behaviors [1].

This application note examines the fundamental limitations of pairwise connectivity approaches and demonstrates how emerging higher-order methodologies provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding brain function in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Theoretical Limitations of Pairwise Approaches

The Incomplete Picture of Brain Dynamics

Pairwise connectivity models suffer from several theoretical shortcomings that limit their ability to fully characterize brain dynamics:

Simplified Representation: By reducing complex multivariate interactions to a set of dyadic connections, pairwise approaches potentially miss collective dynamics that emerge only when three or more regions interact simultaneously [1] [3].

Synergy Blindness: Information-theoretic research reveals two distinct modes of information sharing: redundancy and synergy. Synergistic information occurs when the joint state of three or more variables is necessary to resolve uncertainty arising from statistical interactions that exist collectively but not in separately considered subsystems [3]. Pairwise measures are inherently limited in detecting these synergistic relationships.

Network Context Neglect: Approaches like Pearson correlation do not account for the broader network context in which pairwise connections occur. While partial correlation methods attempt to address this by removing shared influences, they can be overly conservative and may eliminate meaningful higher-order dependencies [4] [2].

Empirical Evidence of Limitations

Comparative studies demonstrate concrete scenarios where pairwise methods fall short:

Consciousness Detection: Research differentiating patients in different states of consciousness found that higher-order dependencies reconstructed from fMRI data encoded meaningful biomarkers that pairwise methods failed to detect [1].

Task Performance Prediction: Higher-order approaches have demonstrated significantly stronger associations between brain activity and behavior compared to traditional pairwise methods [1].

Sensitivity to Intervention Effects: In clinical applications, investigating brain connectivity developments at a high-order level has proven essential to fully capture the complexity and modalities of recovery following treatment [3].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Connectivity Approaches

| Analysis Domain | Pairwise Methods Performance | Higher-Order Methods Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Decoding | Moderate dynamic differentiation between tasks | Greatly enhanced dynamic task decoding [1] | HOIs improve characterization of dynamic group dependencies in rest and tasks |

| Individual Identification | Limited fingerprinting capability | Improved functional brain fingerprinting based on local topological structures [1] | HOIs provide more distinctive individual signatures |

| Brain-Behavior Association | Moderate associations | Significantly stronger associations with behavior [1] | HOIs capture more behaviorally-relevant neural signatures |

| Clinical Differentiation | Limited ability to differentiate patient states | Effective differentiation of states of consciousness [1] | HOIs encode meaningful clinical biomarkers |

Higher-Order Connectivity Frameworks

Topological Data Analysis Approach

One innovative method for capturing higher-order interactions leverages topological data analysis to reveal instantaneous higher-order patterns in fMRI data [1]. This approach involves four key steps:

Signal Standardization: Original fMRI signals are z-scored to normalize the data [1].

Higher-Order Time Series Computation: All possible k-order time series are computed as element-wise products of k+1 z-scored time series, representing instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitude of associated (k+1)-node interactions [1].

Simplicial Complex Encoding: Instantaneous k-order time series are encoded into weighted simplicial complexes at each timepoint [1].

Topological Indicator Extraction: Computational topology tools analyze simplicial complex weights to extract global and local indicators of higher-order organization [1].

This framework generates several key metrics beyond pairwise correlation:

Hyper-coherence: Quantifies the fraction of higher-order triplets that co-fluctuate more than expected from corresponding pairwise co-fluctuations [1].

Violating Triangles: Identify higher-order coherent co-fluctuations that cannot be described in terms of pairwise connections [1].

Homological Scaffold: Assesses edge relevance toward mesoscopic topological structures within the higher-order co-fluctuation landscape [1].

Information-Theoretic Framework

Multivariate information theory provides another framework for capturing HOIs through measures like O-information (OI), which evaluates whether a system is dominated by redundancy or synergy [3]. This approach distinguishes between:

Redundancy: Group interactions explainable by communication of subgroups of variables, representing information replicated across system elements [3].

Synergy: Information that emerges only from the joint interaction of three or more variables, reflecting the brain's ability to generate new information by combining anatomically distinct areas [3].

Table 2: Information-Theoretic Measures for Brain Connectivity

| Measure | Formula | Interpretation | Interaction Type Captured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Information (Pairwise) | I(Si;Sj) = H(Si) - H(Si∣Sj) | Information shared between two variables | Pairwise interactions only |

| O-Information | O(X) = TC(X) - DTC(X) | Overall evaluation of redundancy vs. synergy dominance | Higher-order interactions |

| Redundancy | Not directly computed; inferred when O(X) > 0 | Information replicated across system elements | Duplicative interactions |

| Synergy | Not directly computed; inferred when O(X) < 0 | Novel information from joint interactions | Emergent, integrative interactions |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol: Topological Analysis of Higher-Order fMRI Connectivity

Purpose: To detect and quantify higher-order interactions in resting-state or task-based fMRI data that are missed by pairwise correlation methods.

Materials:

- fMRI data (preprocessed and denoised)

- Brain parcellation atlas (e.g., Schaefer 100x7, HCP 119-region)

- Computational tools: Python with NumPy, SciPy, Topological data analysis libraries

- High-performance computing resources (for large-scale simplicial complex computation)

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Extract time series from N brain regions according to your chosen atlas

- Apply quality control and remove artifacts

- Standardize each regional time series using z-scoring: z(t) = (x(t) - μ)/σ

Compute k-Order Time Series:

- For each timepoint t, compute all possible simplex weights:

- For edges (1-simplices): w{ij}(t) = zi(t) × z_j(t)

- For triangles (2-simplices): w{ijk}(t) = zi(t) × zj(t) × zk(t)

- For higher-order simplices (as needed)

- Apply sign remapping based on parity of contributing signals

- For each timepoint t, compute all possible simplex weights:

Construct Weighted Simplicial Complexes:

- At each timepoint t, construct a simplicial complex K_t

- Assign weights to each simplex based on computed k-order time series values

Extract Topological Indicators:

- Compute hyper-coherence: fraction of "violating triangles" where triangle weight exceeds constituent edge weights

- Identify and record all violating triangles Δv

- Calculate homological scaffolds to assess edge importance in mesoscopic structures

- Analyze contributions to topological complexity from coherent vs. decoherent signals

Statistical Analysis:

- Compare higher-order indicators across experimental conditions or groups

- Assess relationship between higher-order features and behavioral measures

- Evaluate individual identification capacity using higher-order fingerprints

Validation:

- Benchmark against traditional pairwise methods (correlation, partial correlation)

- Test retest reliability in longitudinal data

- Verify biological plausibility through structure-function coupling analysis

Protocol: Single-Subject Statistical Validation of High-Order Interactions

Purpose: To statistically validate subject-specific pairwise and high-order connectivity patterns using surrogate and bootstrap analyses.

Materials:

- Single-subject multivariate fMRI time series

- Surrogate data generation algorithms (e.g., IAAFT, phase randomization)

- Bootstrap resampling implementation

- Information-theoretic computation tools

Procedure:

Connectivity Estimation:

- Compute pairwise connectivity using Mutual Information (MI) for all region pairs

- Compute high-order connectivity using O-information (OI) for all region triplets (or higher combinations)

Surrogate Data Analysis:

- Generate multiple surrogate datasets (typically 100-1000) that preserve individual signal properties but remove coupling

- Compute MI and OI for each surrogate dataset

- Construct null distributions for both pairwise and high-order measures

- Determine significance thresholds (e.g., 95th percentile of null distribution)

Bootstrap Validation:

- Generate bootstrap samples by resampling original time series with replacement

- Compute confidence intervals for MI and OI estimates

- Assess stability and reliability of connectivity patterns

Single-Subject Inference:

- Identify statistically significant pairwise and high-order connections for the individual

- Compare connectivity patterns across different conditions (e.g., pre-/post-treatment)

- Calculate significance rate as proportion of connections exceeding surrogate thresholds

Validation Metrics:

- False positive rate assessment using null data

- Effect size quantification for significant connections

- Intra-subject reliability across bootstrap samples

Table 3: Essential Resources for Higher-Order Connectivity Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Data | HCP 1200 Subject Release [1] | Gold-standard public dataset for method development | Includes resting-state and task fMRI; extensive phenotypic data |

| Brain Parcellations | Schaefer 100x7, HCP 119-region [1] [2] | Define regions of interest for time series extraction | Choice affects sensitivity to detect HOIs; multiple resolutions recommended |

| Pairwise Statistics | PySPI package (239 statistics) [2] | Comprehensive benchmarking against pairwise methods | Includes covariance, precision, spectral, information-theoretic families |

| Topological Analysis | Simplicial complex algorithms [1] | Detect and quantify higher-order interactions | Computationally intensive; requires HPC resources for full brain |

| Information-Theoretic Measures | O-information, Mutual Information [3] | Quantify redundancy and synergy in multivariate systems | Sensitive to data length; requires adequate statistical power |

| Statistical Validation | Surrogate data methods, Bootstrap resampling [3] | Establish significance of connectivity patterns | Critical for single-subject analysis; controls for multiple comparisons |

| Computational Frameworks | Python (NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn) | Implement analysis pipelines | Open-source ecosystem facilitates reproducibility |

Implications for Drug Development and Clinical Applications

The shift from pairwise to higher-order connectivity analysis has significant implications for pharmaceutical research and clinical applications:

Improved Biomarker Sensitivity: Higher-order interactions may provide more sensitive biomarkers for tracking treatment response, particularly for neuropsychiatric disorders and neurological conditions [3]. The enhanced individual fingerprinting capacity of HOIs enables more precise monitoring of intervention effects.

Target Engagement Assessment: HOI analysis could provide novel metrics for assessing how pharmacological agents engage distributed brain networks rather than isolated regions, potentially revealing mechanisms that transcend single neurotransmitter systems.

Personalized Treatment Approaches: Single-subject statistical validation of both pairwise and high-order connectivity enables subject-specific investigation of network pathology and recovery patterns, supporting personalized treatment planning [3].

Clinical Trial Optimization: The enhanced brain-behavior relationships demonstrated by higher-order approaches may improve patient stratification and endpoint selection in clinical trials, potentially reducing required sample sizes.

Future methodological developments should focus on optimizing the balance between computational complexity and biological interpretability, particularly for large-scale clinical studies where practical constraints remain significant.

Conceptual Framework and Quantitative Definitions

In the analysis of multivariate brain connectivity, higher-order interactions (HOIs) describe statistical dependencies that cannot be explained by pairwise relationships alone. These interactions are qualitatively categorized into two fundamental modes: redundancy and synergy [5] [3].

- Redundancy refers to information that is duplicated across multiple variables. This common information can be learned by observing any single variable or proper subset of variables within the system [5]. It represents a failure to reduce uncertainty by measuring additional components.

- Synergy constitutes information that is exclusively present in the joint state of three or more variables. It cannot be accessed by observing any proper subset and is only revealed when all components are considered together [5] [3]. Synergy is a marker of emergent information and is mathematically irreducible.

The O-information (Ω), a key metric from multivariate information theory, provides a scalar value to quantify the net balance between these two modes within a system [3]. A negative O-information indicates a system dominated by synergy, whereas a positive value signifies a redundancy-dominated system [3].

Table 1: Core Information-Theoretic Measures for HOIs

| Measure | Formula | Interpretation | Application in Brain Connectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Correlation (TC) | ( TC(\mathbf{X}) = \left[\sum{i=1}^{N} H(Xi)\right] - H(\mathbf{X}) ) | Quantifies the total shared information or collective constraints in the system; reduces to mutual information for two variables [5]. | Measures overall integration and deviation from statistical independence among brain regions [5]. |

| Dual Total Correlation (DTC) | ( DTC(\mathbf{X}) = H(\mathbf{X}) - \sum{i=1}^{N} H(Xi \mid \mathbf{X}^{-i}) ) | Quantifies the total information shared by two or more variables; captures the complex, multipartite dependencies in a system [5]. | Popular for identifying genuine HOIs; sensitive to shared information that is distributed across multiple nodes [5]. |

| O-Information (Ω) | ( \Omega(\mathbf{X}) = TC(\mathbf{X}) - DTC(\mathbf{X}) ) | A metric of the overall informational character of the system. Ω < 0 indicates synergy-dominance; Ω > 0 indicates redundancy-dominance [3]. | Used to characterize whether a brain network or subsystem operates in a synergistic or redundant mode [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for HOI Analysis in fMRI

The following protocol outlines a robust methodology for the statistical validation of higher-order functional connectivity on a single-subject basis, leveraging resting-state fMRI (rest-fMRI) data [3].

Protocol: Statistically Validated Single-Subject HOI Analysis

I. Objective To identify and validate significant pairwise and higher-order functional connectivity patterns from an individual's multivariate fMRI recordings, enabling subject-specific investigations across different physiopathological states [3].

II. Materials and Reagents

- Data Acquisition: Resting-state fMRI BOLD signal time series [3].

- Software/Packages: Tools for linear parametric regression modeling, surrogate data generation, and bootstrap resampling [3].

- Computational Environment: A high-performance computing cluster is recommended for processing-intensive steps like surrogate and bootstrap analyses [3].

III. Procedure

Data Preprocessing and Parcellation

- Acquire rest-fMRI data and preprocess using a standard pipeline (e.g., motion correction, normalization, denoising with ICA-AROMA and CompCor) [6].

- Apply a brain atlas to parcellate the data into Q regions of interest (ROIs), resulting in a set of random variables ( S = {S1, …, SQ} ) [3] [1].

- Extract the mean BOLD time series for each ROI. For subsequent static connectivity analysis, temporal correlations are disregarded, focusing only on zero-lag effects [3].

Connectivity Estimation

- Pairwise Connectivity: For all pairs of ROIs ( (Si, Sj) ), compute the Mutual Information (MI), ( I(Si; Sj) ), to quantify dyadic statistical dependencies [3].

- High-Order Connectivity: For groups of N ROIs (where ( N = 3, ..., Q )), compute the O-information ( \Omega ) to assess the net redundant or synergistic informational character of the subsystem [3].

Statistical Validation via Surrogate Data (for MI)

- Objective: Test the null hypothesis that two observed ROI time series are independent [3].

- Method: Generate an ensemble of surrogate time series (e.g., Iterative Amplitude Adjusted Fourier Transform - IAAFT). These surrogates preserve the individual linear properties (e.g., power spectrum) of the original signals but destroy any nonlinear or phase-based coupling between them [3].

- Significance Testing: Calculate the MI for each surrogate pair. The MI value from the original data is considered statistically significant if it exceeds the ( (1-\alpha) )-percentile (e.g., 95th for α=0.05) of the surrogate MI distribution [3].

Statistical Validation via Bootstrap (for O-Information)

- Objective: Establish confidence intervals for HOI estimates and enable cross-condition comparisons at the individual level [3].

- Method: Apply a bootstrap resampling technique. Generate a large number of bootstrap samples (e.g., 1000+ ) by randomly resampling the original multivariate time series with replacement [3].

- Confidence Intervals & Comparison: Calculate the O-information for each bootstrap sample. Use the distribution of these values to construct confidence intervals (e.g., 95% CI). For comparing two conditions (e.g., pre- vs. post-treatment), the difference in O-information is deemed significant if the confidence intervals do not overlap or if the bootstrap-derived p-value is below the significance threshold [3].

IV. Expected Results and Analysis

- This approach yields a statistical map of an individual's significant pairwise (MI) and higher-order (Ω) connections [3].

- It allows for the robust identification of "shadow structures"—synergistic subsystems that are missed by standard pairwise functional connectivity analyses but are crucial for capturing the full statistical structure of the brain network [3].

- The method has demonstrated clinical relevance, showing subject-specific changes in high-order connectivity associated with treatment, such as in a pediatric patient with hepatic encephalopathy following liver vascular shunt correction [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit for HOI Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Category | Item / Metric | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Framework | Multivariate Information Theory [5] [3] | Provides the mathematical foundation for defining and disentangling redundancy and synergy using concepts from Shannon entropy. |

| Core Metrics | O-Information (Ω) [3] | Serves as the key scalar metric to determine if a system or subsystem is redundancy-dominated (Ω > 0) or synergy-dominated (Ω < 0). |

| Statistical Validation | Surrogate Data Analysis [3] | Used to test the significance of pairwise connectivity metrics (e.g., MI) by creating null models that preserve individual signal properties but destroy inter-dependencies. |

| Bootstrap Resampling [3] | Used to generate confidence intervals for higher-order metrics like O-information, enabling robust single-subject analysis and cross-condition comparison. | |

| Data Modality | Resting-state fMRI (rest-fMRI) [3] [6] | A common neuroimaging technique used to investigate the intrinsic, higher-order functional architecture (connectome) of the brain. |

| Complementary Framework | Topological Data Analysis (TDA) [5] [1] | An alternative approach that identifies higher-order structures based on the topology of the data manifold (e.g., cavities, cycles). Correlated with synergistic information [5]. |

Advanced Applications and Topological Approaches

Moving beyond purely information-theoretic measures, topological data analysis (TDA) offers a powerful, complementary framework for identifying HOIs. This approach characterizes the shape of data, revealing structures like cycles and cavities in the data manifold that signify complex interactions [5] [1].

Table 3: Topological Descriptors of Higher-Order Interactions

| Topological Indicator | Description | Relation to Information Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Violating Triangles (Δv) [1] | Triplets of brain regions where the strength of the three-way co-fluctuation is greater than what is expected from the underlying pairwise connections. | Indicative of irreducible synergistic interactions that cannot be explained by pairwise edges alone [1]. |

| Homological Scaffold [1] | A weighted graph that highlights the importance of certain edges in forming mesoscopic topological structures (e.g., 1-dimensional cycles) within the brain's functional architecture. | Identifies connections that are fundamental to the global integration of information, often associated with synergistic dynamics [1]. |

| 3-Dimensional Cavities [5] | Persistent voids or "bubbles" in the constructed topological space of neural activity (e.g., shapes like spheres or hollow toroids). | Strongly correlated with the presence of intrinsic, higher-order synergistic information [5]. |

| Hyper-coherence [1] | A global indicator quantifying the fraction of higher-order triplets that are "violating," i.e., where synergistic co-fluctuation dominates. | A direct topological measure of the prevalence of synergy across the whole brain network [1]. |

Advanced research demonstrates that these topological HOIs provide significant advantages. They enhance the decoding of cognitive tasks from brain activity, improve the individual identification of functional brain fingerprints, and strengthen the association between observed brain dynamics and behavior beyond the capabilities of traditional pairwise connectivity models [1].

The study of brain connectivity has evolved from representing the brain as a network of pairwise interactions to models that capture the simultaneous interplay among multiple brain regions. This progression addresses the limitation that pairwise functional connectivity (FC), which defines edges as statistical dependencies between two time series, inherently assumes that all neural interactions are dyadic [1]. In reality, mounting evidence suggests that higher-order interactions (HOIs)—relationships that involve three or more nodes simultaneously—exert profound qualitative shifts in neural dynamics and are crucial for a complete characterization of the brain's complex spatiotemporal dynamics [1]. This document details the application of two information-theoretic measures—Mutual Information and O-information—for the analysis of pairwise and higher-order brain connectivity, providing validated protocols for their use in neuroscientific research and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Comparison of Connectivity Measures

The following table summarizes key properties of different families of connectivity measures, highlighting the comparative advantages of information-theoretic approaches.

Table 1: Benchmarking Properties of Functional Connectivity Measures

| Family of Measures | Representative Examples | Sensitivity to HOIs | Structure-Function Coupling (R²) | Individual Fingerprinting Capacity | Primary Neurophysiological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariance | Pearson's Correlation | Low | Moderate (~0.1-0.2) [2] | High [2] | Linear, zero-lag synchrony |

| Precision | Partial Correlation | Medium | High (~0.25) [2] | High [2] | Direct interactions, accounting for common network influences |

| Information-Theoretic | Mutual Information | High (nonlinear) [7] | Moderate [2] | High [2] [8] | Linear and nonlinear statistical dependencies |

| Higher-Order Information | O-information | Very High (explicit) [1] | Under investigation | High [1] | Synergistic and redundant information between groups of regions |

Table 2: Performance in Practical Applications

| Application Domain | Best-Performing Measure(s) | Reported Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Classification | Multiband Morlet Mutual Information FC (MMMIFC) [8] | 90.77% accuracy (AD vs HC), 90.38% accuracy (FTD vs HC) [8] | Identified frequency-specific biomarkers: theta-band disruption in AD, delta-band reduction in FTD [8] |

| Task Decoding | Local Higher-Order Indicators (e.g., violating triangles) [1] | Outperformed traditional BOLD and edge-time series in dynamic task identification [1] | Enables finer temporal resolution of cognitive state transitions |

| Individual Identification | Precision-based statistics, Higher-order approaches [2] [1] | Improved fingerprinting of unimodal and transmodal functional subsystems [1] | Strengthens association between brain activity and behavior [1] |

| Structure-Function Coupling | Precision, Stochastic Interaction, Imaginary Coherence [2] | R² up to 0.25 [2] | Optimized by statistics that partial out shared influences |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pairwise Functional Connectivity Analysis Using Mutual Information

Aim: To quantify nonlinear statistical dependencies between pairs of brain regions from neuroimaging time series.

Materials and Reagents:

- Preprocessed fMRI or EEG time series from a standardized atlas (e.g., Schaefer 100x7)

- Computational environment (Python with PySPI package, FSL, MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Extract and preprocess regional time series. For fMRI, this includes slice-timing correction, motion realignment, normalization, and band-pass filtering. For EEG, source reconstruction and artifact removal are essential.

- Probability Distribution Estimation: For each pair of time series (X) and (Y), estimate their joint probability distribution (p(X,Y)) and marginal distributions (p(X)) and (p(Y)). This can be achieved using histogram-based methods, kernel density estimation, or (k)-nearest neighbors approaches.

- Mutual Information Calculation: Compute the Mutual Information (MI) using the formula: (I(X;Y) = \sum{x \in X} \sum{y \in Y} p(x,y) \log \frac{p(x,y)}{p(x)p(y)}) This quantifies the reduction in uncertainty about (X) when (Y) is known, and vice versa.

- Network Construction: Populate an (N \times N) connectivity matrix (M), where (M{ij} = I(Xi; X_j)) for all region pairs. This matrix represents the pairwise MI-based functional network.

- Validation and Analysis: Benchmark the resulting network against known neurobiological features, such as its correlation with structural connectivity [2] or its capability for individual subject identification [2] [8].

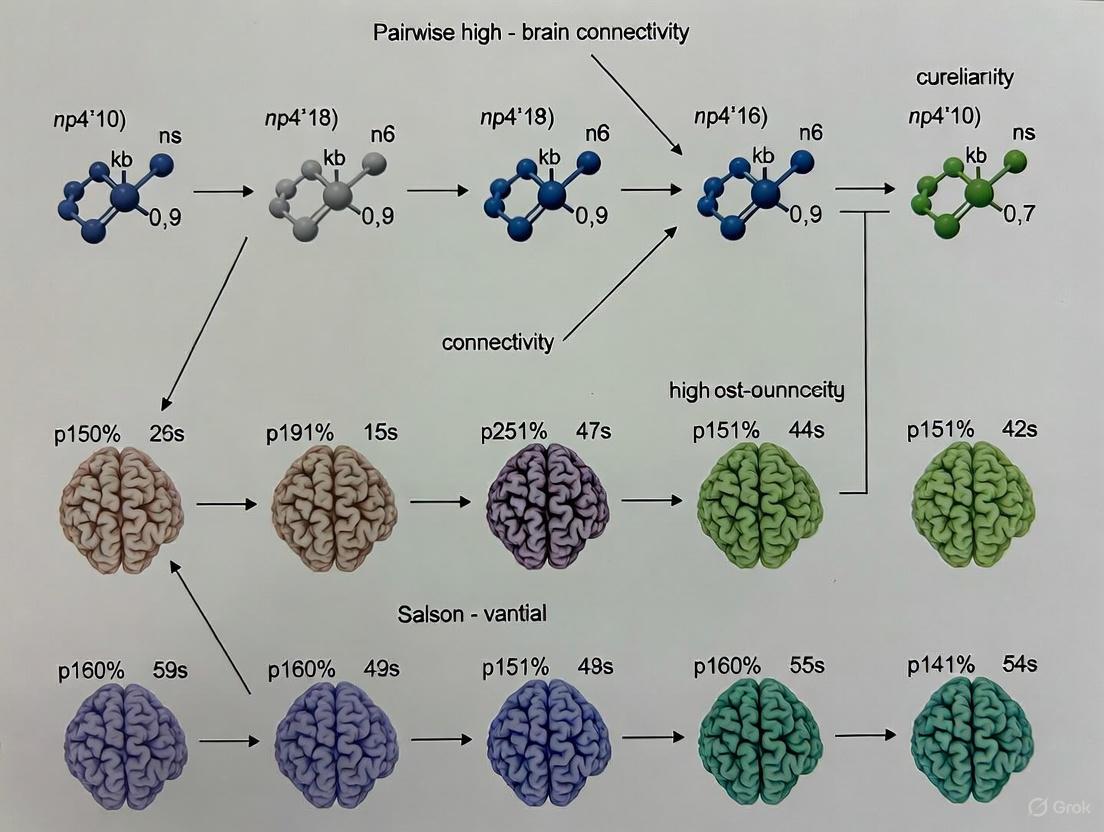

Figure 1: Workflow for pairwise mutual information analysis.

Protocol 2: Higher-Order Connectivity Analysis Using O-Information

Aim: To characterize higher-order interactions and distinguish between synergistic and redundant information in groups of three or more brain regions.

Aim: To characterize higher-order interactions and distinguish between synergistic and redundant information in groups of three or more brain regions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Preprocessed neuroimaging time series (as in Protocol 1)

- Specialized software for higher-order analysis (e.g.,

hoilibrary in Python, custom scripts for topological analysis [1])

Procedure:

- Signal Standardization: Z-score all regional time series to ensure comparability [1].

- Define Variable Sets: Select a target brain region (Xi) and a set of other regions (\mathbf{X} = {X{j}, X_{k}, ...}) with which its potential HOIs will be analyzed.

- Compute Multi-Information: Calculate the total correlation or multi-information for the set ({Xi, \mathbf{X}}), which captures the total shared information among all variables: (I({Xi, \mathbf{X}}) = \sum p({Xi, \mathbf{X}}) \log \frac{p({Xi, \mathbf{X}})}{\prod p(x)}).

- Calculate O-Information: The O-information (\Omega({X_i, \mathbf{X}})) is computed as the difference between the total correlation of the entire set and the sum of the total correlations of all subsets of size (n-1). A positive (\Omega) indicates a system dominated by redundancy, while a negative (\Omega) indicates a system dominated by synergy [1].

- Hypergraph Construction: Represent the results as a hypergraph where hyper-edges connect groups of regions (e.g., triplets, quadruplets) that exhibit significant synergistic or redundant interactions.

- Topological Analysis: Use computational topology tools to analyze the weighted simplicial complex and extract local higher-order indicators, such as "violating triangles" that represent coherent co-fluctuations not explainable by pairwise connections [1].

Figure 2: Workflow for O-information analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PySPI Package [2] | Software Library | Implements 239 pairwise interaction statistics, including mutual information | Large-scale benchmarking of FC methods; standardized calculation of information-theoretic measures |

| HOI Library | Software Library | Specialized for estimating O-information and other higher-order measures | Analysis of synergistic and redundant information in multivariate neural data |

| Human Connectome Project Data [2] [1] | Reference Dataset | Provides high-quality, multimodal neuroimaging data from healthy adults | Method validation; normative baselines; individual differences research |

| Schaefer Parcellation [2] | Brain Atlas | Defines functionally coherent cortical regions of interest | Standardized node definition for reproducible network construction |

| Allen Human Brain Atlas [2] | Reference Data | Provides correlated gene expression maps | Validation of FC findings against transcriptomic data |

| Tensor Decomposition Algorithms [9] | Computational Method | Identifies multilinear patterns and change points in high-order datasets | Dynamic connectivity analysis; capturing transient higher-order states |

Integrated Analysis Workflow

The following diagram integrates pairwise and higher-order approaches into a comprehensive analysis pipeline for validating brain connectivity.

Figure 3: Integrated validation pipeline for multi-scale connectivity.

The Critical Need for Single-Subject Analysis in Personalized Medicine

Personalized medicine aims to move beyond population-wide averages to deliver diagnoses and treatments tailored to the individual patient. A significant statistical challenge in this endeavor is the reliable interpretation of massive omics datasets, such as those from transcriptomics or neuroimaging, from a single subject. Traditional cohort-based statistical methods are often inapplicable or underpowered for single-subject studies (SSS), creating a critical methodological gap [10]. This document outlines the application notes and protocols for conducting robust single-subject analyses, framed within advanced research on statistical validation of pairwise and high-order brain connectivity. We provide detailed methodologies, data presentation standards, and visualization tools to empower researchers in this field.

Background and Rationale

In both transcriptomics and functional brain connectivity, the standard approach for identifying significant signals (e.g., Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) or functional connections) relies on having multiple replicates per condition to estimate variance and compute statistical significance. However, in a clinical setting, obtaining multiple replicates from a single patient is often prohibitively expensive, ethically challenging, or simply impractical [10] [11].

The core challenge is that statistical artefacts and biases can be easily confounded with authentic biological signals when analyzing a dataset from one individual [10]. Furthermore, in neuroimaging, traditional models that represent brain function as a network of pairwise interactions are limited in their ability to capture the complex, synergistic dynamics of the human brain [3] [1]. High-order interactions (HOIs), which involve three or more brain regions simultaneously, are increasingly recognized as crucial for a complete understanding of brain function and its relation to behavior and disease [1] [12]. The move towards personalized neuroscience therefore requires methods that can derive meaningful insights from individual brain recordings by analyzing descriptive indexes of physio-pathological states through statistics that prioritize subject-specific differences [3].

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for single-subject analysis methods as validated in benchmark studies.

Table 1: Performance of Single-Subject DEG Methods in Transcriptomics [11]

| Method Name | Median ROC-AUC (Yeast) | Median ROC-AUC (MCF7) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ss-NOIseq | > 90% | > 75% | Designed for single-subject analysis without replicates. |

| ss-DEGseq | > 90% | > 75% | Adapts a cohort method for single-subject use. |

| ss-Ensemble | > 90% | > 75% | Combines multiple methods; most robust across conditions. |

| ss-edgeR | Variable | Variable | Performance highly dependent on the proportion of true DEGs. |

| ss-DESeq | Variable | Variable | Performance highly dependent on the proportion of true DEGs. |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Connectivity Measures in Neuroimaging [1] [2]

| Connectivity Measure Type | Task Decoding Capacity | Individual Identification | Association with Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise (e.g., Pearson Correlation) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| High-Order (e.g., Violating Triangles) | Greatly Improved | Improved | Significantly Strengthened |

| Precision/Inverse Covariance | N/A | High | High [2] |

| Spectral Measures | N/A | Moderate | Moderate [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Subject Transcriptomic Analysis via an "All-against-One" Framework

This protocol is designed for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from two RNA-Seq samples (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) from a single patient without replicates [10] [11].

1. Prerequisite Data: Two condition-specific transcriptomes from a single subject (e.g., Subject_X_Condition_A.txt, Subject_X_Condition_B.txt).

2. Software and Environment Setup:

- Computing Environment: R programming language (v3.4.0 or later).

- Required R Packages:

referenceNof1(for constructing unbiased reference standards), and packages for ss-DEG methods (e.g.,NOISeq,DESeq2,edgeR) [10] [11].

3. Reference Standard (RS) Construction: To avoid analytical bias, do not use the same method for RS creation and discovery.

- Obtain an isogenic dataset (biological replicates from a matched background) relevant to your study context [11].

- Apply multiple, distinct DEG analytical methods (e.g., NOISeq, edgeR, DESeq) to the isogenic replicate dataset to identify a consensus set of DEGs. This consensus becomes your RS [10] [11].

- Optimize the RS by applying fold-change (FC) thresholds and expression-level cutoffs to increase concordance between methods [10].

4. Single-Subject DEG Prediction:

- Apply one or more ss-DEG methods (e.g., ss-NOIseq, ss-Ensemble) to the two samples from your single subject.

- The output is a list of predicted DEGs for that subject.

5. Validation against Reference Standard:

- Compare the predicted DEGs from Step 4 against the RS from Step 3.

- Calculate performance metrics such as Receiver-Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves and Precision-Recall plots to evaluate the accuracy of the ss-DEG method [11].

6. Recommendation: For the most robust results, use an ensemble learner approach that integrates predictions from multiple ss-DEG methods to resolve conflicting signals and improve stability [10] [11].

Protocol 2: Single-Subject High-Order Brain Connectivity Analysis

This protocol details the statistical validation of high-order functional connectivity in an individual's brain using fMRI data, enabling subject-specific investigation and treatment planning [3].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Data: Resting-state or task-based fMRI time series from a single subject.

- Preprocessing: Standardize the fMRI signals from N brain regions using z-scoring [1].

2. Constructing Functional Connectivity Networks:

- Calculate all possible pairwise interactions between brain regions. Common measures include Mutual Information (MI) or Pearson's correlation coefficient [3] [2].

- Calculate High-Order Interactions (HOIs). One method involves computing k-order time series as the element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series, which are then re-standardized. This represents the instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitude of (k+1)-node interactions (e.g., triangles) [1].

3. Statistical Validation of Connectivity Measures:

- For Pairwise Connections (MI): Use surrogate data analysis.

- Generate surrogate time series that mimic the individual properties (e.g., power spectrum) of the original signals but are otherwise uncoupled.

- Compute the MI for the original paired signals and for a large number of surrogate pairs.

- The MI value is considered statistically significant if it exceeds the 95th percentile of the surrogate distribution [3].

- For High-Order Interactions (O-Information): Use bootstrap analysis.

- Generate multiple bootstrap-resampled versions of the original multivariate time series.

- Compute the O-information (or other HOI metric) for each resampled dataset.

- Construct confidence intervals from the bootstrap distribution.

- An HOI is significant if its confidence interval does not cross zero. Differences in HOI between experimental conditions can also be assessed this way [3].

4. Feature Extraction and Interpretation:

- Extract significant pairwise and high-order features that have passed the above statistical tests.

- These subject-specific fingerprints can be used for:

- Task Decoding: Identifying which cognitive task a subject is performing based on brain activity patterns [1].

- Individual Identification: Uniquely identifying an individual based on their functional connectome [1] [2].

- Clinical Correlation: Associating connectivity patterns with individual behavioral measures or treatment outcomes [3] [1].

Visualization of Workflows

Single-Subject Transcriptomics Analysis

High-Order Brain Connectivity Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Single-Subject Analysis in Personalized Medicine

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

referenceNof1 R Package |

Provides a robust framework for constructing method-agnostic reference standards to evaluate single-subject analyses, minimizing statistical artefact biases. | Transcriptomics [10] |

| Isogenic Biological Replicates | Publicly available datasets (e.g., Yeast BY4741 strain, MCF7 cell line) used as a ground truth for developing and validating single-subject reference standards. | Transcriptomics [11] |

| Surrogate Data Algorithms | Algorithms (e.g., Iterative Amplitude-Adjusted Fourier Transform) that generate null model time series to test the significance of pairwise functional connections. | Neuroimaging [3] |

| Bootstrap Resampling Methods | Statistical technique to estimate the sampling distribution of a statistic (e.g., O-Information) by resampling the data with replacement, used to derive confidence intervals for HOIs. | Neuroimaging [3] |

| Topological Data Analysis (TDA) | A set of computational tools (e.g., Persistent Homology) that can infer and analyze the higher-order interaction structures from neuroimaging time series data. | Neuroimaging [1] [12] |

| SPI (Statistical Pairwise Interactions) Library | A comprehensive library (e.g., pyspi) containing 239+ pairwise statistics for benchmarking and optimizing functional connectivity mapping. |

Neuroimaging [2] |

Linking Network Topology to Brain Function and Criticality

Understanding how brain functions arise from neuronal architecture is a central question in neuroscience. The Critical Brain Hypothesis (CBH) proposes that brain networks operate near a phase transition, a state supporting optimal computational performance, efficient memory usage, and high dynamic range for health and function [13]. Mounting evidence suggests that the brain's particular hierarchical modular topology—characterized by groups of nodes segregated into modules, which are in turn nested within larger modules—plays a crucial role in achieving and sustaining this critical state [13] [1]. Furthermore, traditional models based on pairwise interactions are increasingly seen as limited, with higher-order interactions (HOIs) providing a more complete picture of brain dynamics [1]. This Application Note details the quantitative evidence and provides standardized protocols for investigating the link between network topology, criticality, and brain function within the context of statistical validation of pairwise and high-order brain connectivity research.

Quantitative Data on Topology, Criticality, and Higher-Order Interactions

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from computational and empirical studies, highlighting how specific topological features influence brain dynamics and the added value of higher-order analysis.

Table 1: Influence of Intramodular Topology on Critical Dynamics in Hierarchical Modular Networks [13]

| Network Topology Type | Robustness in Sustaining Criticality | Typical Dynamical Regime | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse Erdős-Rényi (ER) | High | Critical/Quasicritical | Random pairwise connection probability (ε = 0.01) |

| Sparse Regular (K-Neighbor, KN) | High | Critical/Quasicritical | Fixed degree (K = 40) for all neurons |

| Fully Connected (FC) | Low | Tends toward Supercritical | All-to-all intramodular connectivity |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Connectivity Methods in fMRI Analysis [1]

| Analysis Method | Task Decoding (Element-Centric Similarity) | Individual Identification | Association with Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Pairwise (Edge) Signals | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Higher-Order (Triangle) Signals | Greatly Improved | Improved | Significantly Stronger |

| Homological Scaffold Signals | Improved | Improved | Stronger |

Table 3: Key Statistical Measures for Comparing Quantitative Data Across Conditions [14] [15]

| Statistical Measure | Category | Description | Interpretation in Connectivity Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean / Median | Measure of Center | Average / Central value in a sorted dataset | Compares the typical level of connectivity strength or activity between groups. |

| Standard Deviation | Measure of Variability | Average deviation of data points from the mean | Indicates the variability or consistency of connectivity values within a single group or condition. |

| Interquartile Range (IQR) | Measure of Variability | Range between the 25th and 75th percentiles (Q3 - Q1) | Describes the spread of the central portion of the data, reducing the influence of outliers. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Simulating Criticality in Hierarchical Modular Networks

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing and simulating hierarchical modular neuronal networks to study their critical dynamics [13].

1. Network Construction:

- Objective: Generate a network with a nested modular structure.

- Procedure for ER and KN Networks:

- Initialization: Start with a single module of N neurons at hierarchical level H=0.

- Recursive Division: For each level from H=1 to Hmax:

- Randomly split every existing module into two new modules of equal size.

- Rewire Intermodular Connections: For each connection linking neurons in different modules, replace it with a new connection within the same module as the presynaptic neuron with a high probability (e.g., R=0.9). This reinforces intramodular density.

- Procedure for FC Networks:

- Initialization: Start by partitioning N neurons into multiple, smaller, fully connected modules.

- Recursive Clustering: At each higher hierarchical level, cluster existing modules into pairs of larger modules.

- Establish Intermodular Links: For each pair of modules being connected, create links between their neurons with a level-dependent probability (e.g., using parameters α=1 and p=1/4) to maintain a constant number of cross-level connections.

2. Neuron Model and Dynamics:

- Model: Use a network of discrete-time stochastic Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neurons.

- Membrane Potential Update: The subthreshold membrane potential ( Vi[t] ) of neuron *i* at time *t* evolves as: ( Vi[t+1] = μVi[t] + Ii[t] + \frac{1}{N}\sum{j=1}^{N}W{ij}[t]Sj[t] ) where *μ* is the leakage constant, ( Ii ) is external input, ( W{ij} ) is the adaptive synaptic weight, and ( Sj ) is the spike state of neuron j (1 for spike, 0 otherwise) [13].

- Spiking: A spike is emitted when ( Vi[t] ) exceeds a fixed threshold ( V{th} ). The potential is then reset to ( V_{reset} ).

3. Homeostatic Adaptation:

- Objective: Implement a biological mechanism to self-organize towards criticality.

- Mechanism: Use dynamic neuronal gains or dynamic synapses (e.g., LHG dynamics). These parameters increase when network activity is low and decrease when activity is high, creating a negative feedback loop that stabilizes activity near a critical point [13].

4. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Avalanche Definition: Record spike trains and define avalanches as sequences of continuous activity bounded by silent periods.

- Criticality Signatures: Calculate the distributions of avalanche sizes and durations. A power-law distribution is a key signature of criticality. Further, analyze the scaling relationship between average avalanche size and duration [13].

Protocol 2: Assessing Brain Network Resistance with TMS-EEG

This protocol uses Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation combined with Electroencephalography (TMS-EEG) to empirically probe network dynamics and its resistance to change in humans [16].

1. Experimental Design:

- Objective: Measure changes in brain network reactivity during offline processing following a behavioral task.

- Participants: Recruit subjects according to study design (e.g., healthy controls vs. patient populations).

- Conditions: Include at least two sessions: a baseline resting-state measurement and a post-task measurement.

2. Setup Preparation:

- TMS: Use a TMS apparatus with a MRI-guided neuromavigation system to ensure precise and consistent targeting of a specific brain region (e.g., primary motor cortex).

- EEG: Apply a high-density EEG cap (e.g., 64 channels). Impedances should be kept below 5 kΩ to ensure high-quality signal acquisition.

- Artifact Control: Employ a TMS-compatible system and use techniques to minimize the large electromagnetic artifact induced by the TMS pulse on the EEG recording.

3. Data Collection:

- Stimulation Protocol: At each session, apply a series of TMS pulses (e.g., 100-200 pulses) to the target region during resting state. The inter-stimulus interval should be jittered to prevent anticipatory effects.

- EEG Recording: Continuously record EEG data before, during, and after each TMS pulse. Sampling rate should be sufficiently high (e.g., ≥ 5 kHz) to capture the initial TMS-evoked potential (TEP) and the subsequent spread of activity.

4. Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Filter the data (e.g., 1-100 Hz bandpass, 50/60 Hz notch). Automatically or manually reject trials with large artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity).

- TMS-Evoked Potential (TEP): Average the EEG signals time-locked to the TMS pulses to extract the characteristic TEP components, which reflect the local and network-level response to the perturbation.

- Network Metrics: Calculate the global mean field power (GMFP) or similar indices from the TEP as a measure of the overall network activation in response to the stimulus. A change in the amplitude or duration of this response (e.g., post-task) indicates a change in the network's resistance or excitability [16].

Protocol 3: Inferring Higher-Order Interactions from fMRI Data

This protocol details a topological method to uncover HOIs from fMRI time series, moving beyond pairwise correlation [1].

1. Data Preprocessing:

- Starting Data: Use preprocessed fMRI BOLD time series from N brain regions.

- Standardization: Z-score each regional time series to have zero mean and unit variance.

2. Constructing k-Order Time Series:

- Calculation: For each timepoint, compute all possible k-order time series as the element-wise product of (k+1) z-scored time series. For example, a 2-order (triangle) time series for regions {i, j, k} is: ( TS{ijk}[t] = zi[t] \cdot zj[t] \cdot zk[t] ).

- Standardization and Signing: Z-score these new k-order time series. Then, assign a sign at each timepoint: positive if all (k+1) original time series were concordant (all positive or all negative), and negative otherwise. This highlights fully coherent group interactions.

3. Building Simplicial Complexes:

- Encoding: At each timepoint t, encode the brain's activity into a mathematical object called a weighted simplicial complex.

- Weights: Nodes (0-simplices) represent regions. Edges (1-simplices) represent pairwise interactions, weighted by the traditional co-fluctuation value. Triangles (2-simplices) represent triple interactions, weighted by the signed 2-order time series value calculated in the previous step.

4. Extracting Higher-Order Indicators:

- Global Indicator (Hyper-coherence): Identify "violating triangles"—triangles whose weight (strength of triple interaction) is greater than the weights of its three constituent edges. The fraction of such triangles quantifies global hyper-coherence.

- Local Indicators:

- Violating Triangles List: Record the identity and weight of each violating triangle. These are triplets of regions whose coordinated activity cannot be explained by pairwise relationships alone.

- Homological Scaffold: Construct a weighted graph that highlights the edges most critical to forming mesoscopic topological structures (like cycles) within the simplicial complex, assessing their importance in the overall higher-order landscape [1].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Hierarchical Modular Network Construction and Criticality

HM Network Criticality: This diagram illustrates the recursive algorithm for building hierarchical modular networks and the homeostatic mechanism that regulates neuronal activity to maintain a critical state.

Higher-Order fMRI Analysis Pipeline

HOI Analysis Pipeline: This workflow outlines the key steps for inferring higher-order interactions from fMRI data, from raw signals to higher-order topological indicators.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Tools for Connectivity and Criticality Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic LIF Neuron Model | Computational unit for simulating spiking network dynamics. | Includes membrane potential, leakage, spiking threshold, and reset; can be extended with adaptation [13]. |

| Homeostatic Plasticity Rules | A biologically-plausible mechanism to self-organize and maintain network criticality. | Dynamic neuronal gains (N parameters) or dynamic synapses like LHG (O(N²) parameters) [13]. |

| Hierarchical Network Generators | Algorithms to create computational models with nested modular architecture. | Erdős-Rényi (ER), K-Neighbor (KN), and Fully Connected (FC) generative algorithms [13]. |

| TMS-EEG System | Non-invasive tool for causal perturbation and measurement of whole-brain network dynamics. | Combines a TMS apparatus with a high-density, TMS-compatible EEG system for evoking and recording brain activity [16]. |

| Simplicial Complex Analysis | Mathematical framework for representing and analyzing higher-order interactions. | Encodes nodes, edges, triangles, etc., into a single object for topological interrogation [1]. |

| Topological Data Analysis (TDA) Libraries | Software for extracting features from inferred higher-order structures. | Used to compute indicators like hyper-coherence and homological scaffolds from simplicial complexes [1]. |

A Practical Framework for Validating Connectivity on a Single-Subject Basis

In brain connectivity research, distinguishing genuine neural interactions from spurious correlations caused by noise, finite data samples, or signal properties is a fundamental challenge. Statistical validation is therefore not merely a supplementary step but a cornerstone for ensuring the biological validity and reproducibility of findings. Within the context of pairwise and high-order brain connectivity research, two computer-intensive statistical methods have become indispensable: surrogate data analysis and bootstrap analysis [17] [3].

Surrogate data analysis is primarily used for hypothesis testing, creating synthetic data that preserve specific linear properties of the original data (e.g., power spectrum, autocorrelation) but destroy the nonlinear or dependency structures under investigation. By comparing connectivity metrics from original and surrogate data, researchers can test the null hypothesis that their results are explainable by a linear process [18] [19]. Conversely, bootstrap analysis is a resampling technique for estimating the sampling distribution of a statistic, such as a connectivity metric. It allows researchers to construct confidence intervals and assess the stability and reliability of their estimates without making strict distributional assumptions [3] [20].

This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these core validation techniques, framed within the rigorous demands of modern pairwise and high-order brain connectivity research.

Surrogate Data Analysis

Conceptual Foundation and Applications

Surrogate data methods test the null hypothesis that an observed time series is generated by a specific linear process. The core principle involves generating multiple surrogate datasets that mimic the original data's linear characteristics but are otherwise random. If a connectivity metric (e.g., synchronization likelihood, mutual information) computed from the original data is significantly different from the distribution of that metric computed from the surrogates, the null hypothesis can be rejected, providing evidence for genuine, non-random connectivity [18] [21].

This technique is crucial in brain connectivity for:

- Testing for Non-Random Connectivity: Determining whether observed functional connections exceed chance levels [21].

- Validating Nonlinear Dynamics: Assessing whether brain signals exhibit significant nonlinearity, justifying the use of nonlinear analysis methods [18].

- Establishing Statistical Thresholds: Defining significance thresholds for connectivity matrices in network analysis, thereby controlling for false positives [18] [21].

Quantitative Comparison of Surrogate Generation Algorithms

Table 1: Key Algorithms for Generating Surrogate Data

| Algorithm Name | Core Principle | Properties Preserved | Properties Randomized | Primary Use Case in Connectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Randomization | Applies a Fourier transform, randomizes the phase spectrum, and performs an inverse transform [18]. | Power spectrum (and thus autocorrelation) [18] [19]. | All temporal phase relationships, destroying nonlinear dependencies [18]. | General-purpose test for nonlinearity and non-random connectivity in stationary signals [18]. |

| Autoregressive Randomization (ARR) | Fits a linear autoregressive (AR) model to the data and generates new data by driving the AR model with random noise [19]. | Autocorrelation function and the covariance structure of multivariate data [19]. | The precise temporal sequence and any higher-order moments not captured by the AR model. | Testing for nonlinearity in multivariate signals while preserving linear temporal dependencies [19]. |

| Static Null (Gaussian) | Generates random data from a multivariate Gaussian distribution with a covariance matrix equal to that of the original data [19]. | Covariance structure between signals [19]. | All temporal dynamics and non-Gaussian properties. | Testing whether observed connectivity is explainable by static, linear correlations only [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Connectivity Significance with Phase Randomization

This protocol details the steps for validating pairwise or high-order connectivity metrics using phase-randomized surrogates.

Objective: To determine if the observed functional connectivity value between two or more neural signals is statistically significant against the null hypothesis of a linear correlation structure.

Materials and Reagents:

- Preprocessed neural time-series data (e.g., EEG, MEG, fMRI BOLD).

- Computing environment with programming capabilities (e.g., MATLAB, Python, R).

- Software for connectivity metric calculation (e.g., Mutual Information, Synchronization Likelihood, O-Information for high-order interactions [3]).

Procedure:

- Compute Original Metric: Calculate the functional connectivity metric of interest (e.g., mutual information for pairwise, O-information for high-order) on the original multivariate neural dataset [3].

- Generate Surrogates: For each original time series, generate a large number (N) of phase-randomized surrogate time series [18] [21].

- Technical Note: For signals with a strong dominant frequency (e.g., alpha rhythm in EEG), ensure the segment length comprises an integer number of periods of this frequency to avoid artificial non-linearity detection [18].

- Compute Null Distribution: Calculate the same connectivity metric for each of the N surrogate datasets, creating a null distribution of connectivity values under the linear hypothesis.

- Statistical Testing: Compare the original connectivity value to the null distribution.

- For a one-tailed test (e.g., testing for connectivity greater than chance), the p-value is estimated as the proportion of surrogate-derived metrics that are greater than or equal to the original metric.

- A standard significance threshold is p < 0.05. Correct for multiple comparisons if testing many connections (e.g., using False Discovery Rate) [21].

Figure 1: Workflow for surrogate data analysis to test connectivity significance. The process tests whether the original connectivity metric is significantly different from what is expected by a linear process.

Bootstrap Analysis

Conceptual Foundation and Applications

Bootstrap analysis is a resampling method used to assess the reliability and precision of estimated parameters. By drawing multiple random samples (with replacement) from the original data, it approximates the sampling distribution of a statistic. This is particularly valuable in brain connectivity research, where the underlying distribution of many connectivity metrics is unknown or non-normal [20].

In the context of pairwise and high-order connectivity, bootstrap methods are instrumental for:

- Constructing Confidence Intervals (CIs): Providing a range of plausible values for a connectivity metric, such as the strength of a functional connection [3] [20].

- Assessing Stability in Single-Subject Analyses: Enabling robust statistical inferences at the individual level, which is crucial for personalized medicine and clinical applications [3].

- Comparing Conditions: Testing whether connectivity changes between two experimental conditions (e.g., rest vs. task) are statistically significant [22].

Quantitative Comparison of Bootstrap Methods

Table 2: Key Bootstrap Methods for Connectivity Research

| Bootstrap Method | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Considerations for Connectivity Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile Bootstrap | The confidence interval is directly taken from the percentiles (e.g., 2.5th and 97.5th) of the bootstrap distribution [20]. | Simple and intuitive to implement. | Can be biased if the bootstrap distribution is not centered on the original statistic [20]. |

| Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) | Adjusts the percentiles used for the CI to account for both bias and skewness in the bootstrap distribution [22] [20]. | More accurate confidence intervals for skewed statistics and small sample sizes; highly recommended for practice [22]. | Computationally more intensive than the percentile method. |

| Case Resampling | Entire experimental units (e.g., all time series from a single subject's scan) are resampled with replacement. | Preserves the inherent dependency structure within a subject's data. | Ideal for group-level analysis where each subject is an independent unit. |

| Paired Bootstrap | For paired data (e.g., baseline vs. variant under identical seeds), the deltas (differences) are resampled [22]. | Reduces variance by exploiting the positive correlation between paired measurements, increasing sensitivity to detect small changes [22]. | Essential for comparing connectivity across conditions within the same subject or under identical computational seeds. |

Experimental Protocol: Paired Bootstrap for Comparing Connectivity Across Conditions

This protocol uses a paired, BCa bootstrap to evaluate if a change in brain connectivity between two conditions is statistically significant at the single-subject or group level.

Objective: To test whether the difference in a functional connectivity metric between Condition A and Condition B is statistically significant, using a paired design to control for variability.

Materials and Reagents:

- Neural data from the same subject(s) under two different conditions (e.g., rest and task).

- Computational resources for multiple connectivity estimations.

Procedure:

- Calculate Per-Unit Deltas: For each independent experimental unit (e.g., a subject or a random seed), calculate the delta (Δ) as the connectivity metric in Condition B minus the connectivity metric in Condition A. This creates a vector of observed deltas [22].

- Generate Bootstrap Samples: Generate a large number (e.g., 1000-2000) of bootstrap samples by resampling the vector of deltas with replacement. Each sample must be the same size as the original vector.

- Compute Bootstrap Distribution: For each bootstrap sample, calculate the mean delta. This creates the bootstrap distribution of the mean difference.

- Construct BCa Confidence Interval: Calculate the BCa confidence interval (e.g., 95%) from this bootstrap distribution [22] [20].

- Hypothesis Testing: If the 95% BCa confidence interval for the mean delta does not include zero, you can reject the null hypothesis and conclude a significant difference in connectivity between the two conditions [22].

Figure 2: Workflow for a paired bootstrap analysis to compare connectivity across two conditions. This method is more powerful for detecting small changes by leveraging paired measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Data "Reagents" for Connectivity Validation

| Item Name | Function / Definition | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Preprocessed fMRI/EEG Time Series | The cleaned, artifact-free neural signal from regions of interest (ROIs). The fundamental input data. | Preprocessing (filtering, artifact rejection) is critical, as poor data quality severely biases connectivity estimates and their validation [17]. |

| Connectivity Metric Algorithms | Software implementations for calculating metrics like Mutual Information (pairwise) or O-Information (high-order) [3]. | The choice of metric (pairwise vs. high-order) dictates the complexity of interactions that can be detected. High-order metrics can reveal synergistic structures missed by pairwise approaches [3] [1]. |

| Phase Randomization Script | Code to perform Fourier transform, phase randomization, and inverse transform. | A core "reagent" for generating surrogate data. Must be carefully implemented to handle signal borders and dominant rhythms [18]. |

| BCa Bootstrap Routine | A computational function that performs the Bias-Corrected and Accelerated bootstrap procedure. | A more robust alternative to simple percentile methods for constructing confidence intervals, especially with skewed statistics [22] [20]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Parallel computing environment. | Both surrogate and bootstrap analyses are computationally intensive, requiring 1000s of iterations. HPC drastically reduces computation time. |

| Statistical Parcellation Atlas | A predefined map of brain regions (e.g., with 100-500 regions) [23]. | Provides the nodes for the connectivity network. Higher-order parcellations allow for the investigation of finer-grained, specialized subnetworks [23]. |

Step-by-Step Guide to Assessing Pairwise Connectivity Significance

In contemporary neuroscience, particularly within the framework of the BRAIN Initiative's vision to generate a dynamic picture of brain function, the statistical validation of brain connectivity metrics is essential [24]. This is especially true for personalized neuroscience, where the goal is to derive meaningful insights from individual brain signal recordings to inform subject-specific interventions and treatment planning [3]. Analyzing the descriptive indexes of physio-pathological states requires statistical methods that prioritize individual differences across varying experimental conditions.

Functional connectivity networks, which model the brain as a complex system by investigating inter-relationships between pairs of brain regions, have long been a valuable tool [3]. However, the usefulness of standard pairwise connectivity measures is limited because they can miss high-order dependencies and are susceptible to spurious connections from finite data size, acquisition errors, or structural misunderstandings [3]. Therefore, moving from simple observation of a connectivity value to establishing its statistical significance and accuracy is a critical step for a reliable assessment of an individual's underlying condition, helping to prevent biased clinical decisions. This guide provides a detailed protocol for assessing the significance of pairwise connectivity, forming a foundational element of a broader thesis on the statistical validation of pairwise and high-order brain connectivity.

Core Statistical Methodologies

The rationale for this approach involves using surrogate data to test the significance of putative connections and bootstrap resampling to quantify the accuracy of the connectivity estimates and compare them across conditions [3].

Surrogate Data Analysis for Significance Testing

Purpose: To test the null hypothesis that two observed brain signals are independent. This procedure generates simulated data sets that preserve key individual properties of the original signals (e.g., linear autocorrelation) but are otherwise uncoupled [3] [25].

Theoretical Basis: The method creates a null distribution for the mutual information (MI) value under the assumption of independence. Suppose you compute the MI, denoted as ( I_{orig} ), for the original pair of signals. The surrogate testing procedure is as follows:

- Generate Multiple Surrogate Pairs: Create ( N_s ) (e.g., 1,000) independent pairs of surrogate time series from the original pair of signals.

- Compute Null Distribution: Calculate the MI, ( I{surr}^{(i)} ), for each of the ( Ns ) surrogate pairs.

- Determine Significance: Compare the original MI value, ( I{orig} ), to the distribution of ( I{surr} ).

A one-tailed test is typically used to identify a connectivity value significantly greater than expected by chance. The ( p )-value can be approximated as: [ p = \frac{\text{number of times } I{surr}^{(i)} \geq I{orig}}{N_s} ] A connection is deemed statistically significant if the ( p )-value is below a predefined threshold (e.g., ( p < 0.05 ), corrected for multiple comparisons).

Bootstrap Analysis for Estimating Confidence Intervals

Purpose: To assess the accuracy and stability of the estimated pairwise connectivity measure (e.g., MI) and to enable comparisons of connectivity strength across different experimental conditions (e.g., pre- vs. post-treatment) on a single-subject level [3].

Theoretical Basis: The bootstrap technique involves drawing multiple random samples (with replacement) from the original data to create a sampling distribution for the statistic of interest [3] [25].

- Generate Bootstrap Samples: Create ( N_b ) (e.g., 1,000) new data sets by randomly resampling, with replacement, the time points from the original multivariate dataset.

- Compute Bootstrap Distribution: For each bootstrap sample, re-calculate the pairwise MI, ( I_{boot}^{(i)} ), for the connection in question.

- Construct Confidence Intervals: The distribution of ( I_{boot} ) values forms an empirical sampling distribution. A ( 100(1-\alpha)\% ) confidence interval (e.g., 95% CI) can be derived using the percentile method: the interval is defined by the ( \alpha/2 ) and ( 1-\alpha/2 ) quantiles of the bootstrap distribution.

The resulting confidence intervals allow researchers to determine the reliability of individual estimates and to assess whether a change in connectivity between two states is statistically significant (e.g., if the confidence intervals do not overlap).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surrogate Data Testing for Significant Pairwise Links

This protocol details the steps to identify which pairwise connections in a single subject's functional connectivity network are statistically significant.

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing. Begin with preprocessed resting-state fMRI (or other neuroimaging) time series data for ( N ) brain regions. Let ( X ) and ( Y ) be the ( T )-length time series (where ( T ) is the number of time points) for two specific regions of interest.

- Step 2: Calculate Observed Mutual Information. Compute the mutual information ( I(X; Y) ) for the original data, denoted as ( I_{orig} ).

- Step 3: Generate Surrogate Data. Create ( Ns = 1000 ) surrogate pairs ( (X^*i, Y^*_i) ). A common and robust method is the Iterative Amplitude Adjusted Fourier Transform (IAAFT) algorithm, which preserves the power spectrum and amplitude distribution of the original signals while breaking any nonlinear coupling.

- Step 4: Compute Surrogate Mutual Information. For each surrogate pair ( (X^_i, Y^i) ), calculate the mutual information, ( I{surr}^{(i)} ).

- Step 5: Formulate Statistical Test. Construct the null distribution from the ( Ns ) values of ( I{surr} ).

- Step 6: Correct for Multiple Comparisons. Since you are testing connections between many possible pairs of regions, apply a multiple comparisons correction (e.g., False Discovery Rate, FDR) to the resulting ( p )-values across all tested pairs.

- Step 7: Identify Significant Network. Retain only those pairwise connections with an FDR-corrected ( p )-value < 0.05. This constitutes the statistically significant pairwise functional network for the individual.

Protocol 2: Bootstrap Confidence Intervals for Cross-Condition Comparison

This protocol assesses the reliability of a connectivity estimate and tests for significant changes in connectivity between two conditions (e.g., rest vs. task, pre- vs. post-treatment) within a single subject.

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Organize the preprocessed time series data for the two conditions (Condition A and Condition B) separately. For each condition, you will have a ( T \times N ) matrix of time series.

- Step 2: Select Connection of Interest. Identify the specific pairwise connection (e.g., between Region P and Region Q) to be analyzed.

- Step 3: Bootstrap Sampling for Each Condition.

- For Condition A, generate ( Nb = 1000 ) bootstrap samples by randomly selecting ( T ) time points from the Condition A data, with replacement.

- For each bootstrap sample ( j ), compute the MI between Region P and Q, ( I{A}^{(j)} ).

- Repeat this process for Condition B to obtain ( Nb ) values of ( I{B}^{(j)} ).

- Step 4: Construct Confidence Intervals. For the distributions of ( I{A} ) and ( I{B} ), calculate the 95% confidence intervals using the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles.

- Step 5: Compare Conditions. A conservative approach to determine a significant change is to check for non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals between Condition A and Condition B. For a more direct test, one can compute the bootstrap distribution for the difference ( I{A} - I{B} ) and check if its 95% confidence interval excludes zero.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for Connectivity Validation

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Preprocessed rsfMRI Data | Foundation for all analyses; cleaned and standardized BOLD time series. | Data should be preprocessed (motion correction, normalization, etc.) from a reliable source or pipeline [23]. |

| Mutual Information Algorithm | Core metric for quantifying pairwise, nonlinear functional connectivity. | Can be estimated using linear (parametric) or nonlinear (nonparametric) methods; parametric models are often preferred for neuroimaging data [3]. |

| IAAFT Surrogate Algorithm | Generates phase-randomized surrogate data that preserve linear autocorrelations. | Crucial for creating a valid null distribution; available in toolboxes like 'TISEAN' or as custom scripts in Python/R [3] [25]. |