Statistical Validation of Single-Subject Brain Connectivity: Methods, Challenges, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the statistical validation of brain connectivity measures at the single-subject level, a critical requirement for personalized diagnostics and treatment monitoring in clinical neuroscience...

Statistical Validation of Single-Subject Brain Connectivity: Methods, Challenges, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the statistical validation of brain connectivity measures at the single-subject level, a critical requirement for personalized diagnostics and treatment monitoring in clinical neuroscience and drug development. We explore the foundational shift from group-level to subject-specific analysis, detailing advanced methodological approaches including surrogate data analysis, bootstrap validation, and change point detection. The content addresses key challenges such as reliability, motion artifacts, and analytical choices, while presenting rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of connectivity measures. This guide equips researchers and drug development professionals with the necessary tools to implement robust, statistically validated single-subject connectivity analysis in both research and clinical settings.

The Paradigm Shift to Single-Subject Analysis in Connectomics

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Sparse or Uninterpretable Single-Subject Connectivity Patterns

Problem: The connectivity pattern for an individual subject appears overly sparse, random, or does not reflect expected neurophysiological organization. Cause: This often results from applying group-level statistical thresholds (e.g., a fixed edge density) to single-subject data, which fails to account for the individual's unique signal-to-noise ratio and may retain spurious connections or remove genuine weak connections [1]. Solution: Implement a subject-specific statistical validation for the connectivity estimator.

- Generate a Null Distribution: Use a phase-shuffling procedure to create multiple surrogate datasets from the individual's original time series, disrupting temporal relationships to model the null case of no connectivity [1].

- Establish Subject-Specific Threshold: For each potential connection (edge), calculate the corresponding connectivity value from each surrogate dataset. Determine a statistical threshold (e.g., 95th percentile) from this null distribution.

- Validate Actual Connections: Compare the individual's actual connectivity values against this subject-specific threshold. Retain only connections that are statistically significant [1].

- Correct for Multiple Comparisons: Apply a correction method like the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to control for false positives across the many connections tested [1].

Issue 2: Choosing a Threshold for Single-Subject Adjacency Matrices

Problem: Inconsistent results when converting continuous connectivity values into a binary adjacency matrix (representing presence/absence of a connection). Cause: Relying on arbitrary fixed thresholds or group-level edge densities, which can dramatically alter the network's topology and are not tailored to individual data quality [1]. Solution: Avoid arbitrary thresholds. Prefer the statistical validation method described above. If a fixed edge density must be used for comparison purposes, ensure it is justified and report it alongside results from the statistical validation approach. Benchmarking studies suggest that precision-based and covariance-based pairwise statistics may provide more robust results for individual subjects [2].

Issue 3: Selecting a Pairwise Interaction Statistic

Problem: The choice from hundreds of available pairwise statistics leads to substantial variation in the resulting functional connectivity matrix's organization [2]. Cause: Different statistics are sensitive to different types of underlying neurophysiological relationships (e.g., linear vs. nonlinear, direct vs. indirect) [2]. Solution: Tailor the statistic to your specific research question and the presumed neurophysiological mechanism.

- For individual fingerprinting (identifying a subject based on their connectome), measures like covariance, precision, and distance have shown high capacity to differentiate individuals [2].

- For maximizing structure-function coupling (the link to white matter tracts), precision and stochastic interaction statistics perform well [2].

- The conventional Pearson's correlation (covariance) remains a reasonable default for many applications and shows good alignment with structural connectivity [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I just use the same statistical thresholds for single-subject studies that I use for group-level analysis? Group-level thresholds average out individual variability and data quality differences. Applying them to a single subject can result in networks that are not representative of that individual's true brain organization, as they may include connections that are not statistically significant for that subject or remove genuine connections that are weaker [1] [3]. Subject-specific statistical validation is required to make valid inferences about an individual [3].

Q2: What are the key methodological differences between inter-individual and intra-individual correlation analyses? The table below summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | Inter-Individual Correlation | Intra-Individual Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | A single data point from each of many individuals. | Multiple repeated scans from a single individual over time [4]. |

| Primary Inference | On population-level traits and variability (e.g., genetics, general aging effects). | On within-subject dynamics and states (e.g., slow-varying functional patterns, aging within an individual) [4]. |

| Driving Factors | Stable, trait-like factors (genetics, life experience) and long-term influences like aging. | State-like effects (momentary mental state) and intra-individual aging processes [4]. |

| Typical Use Case | Identifying general organizational principles of the brain across a population. | Tracking changes within a patient over the course of therapy or disease progression. |

Q3: How does the choice of connectivity metric affect the functional connectivity network I see? The choice of pairwise statistic (e.g., Pearson correlation, partial correlation, mutual information) qualitatively and quantitatively changes the resulting network. Different metrics will identify different sets of network hubs, show varying relationships with physical distance and structural connectivity, and have different capacities for individual fingerprinting and predicting behavior [2]. There is no single "best" metric; it must be chosen based on the research question.

Q4: My Graphviz diagram isn't showing formatted text. The labels appear as raw HTML.

This is typically caused by using an outdated Graphviz engine. HTML-like labels with formatting tags (like <B>, <I>) are only supported in versions after 14 October 2011 [5] [6]. Ensure you have an up-to-date installation. Some web-based Graphviz tools may also not support these features [7].

Q5: How can I create a node in Graphviz with a bolded title or other rich text formatting?

You must use HTML-like labels and the shape=plain or shape=none attribute. Record-based shapes do not support HTML formatting [5] [6]. The following DOT code creates a node with a bold title:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Statistical Validation of Single-Subject Connectivity using Shuffling

Purpose: To derive a statistically validated adjacency matrix of functional connectivity for an individual subject. Methodology:

- Estimate Functional Connectivity: Calculate the full, continuous connectivity matrix for the single subject using your chosen estimator (e.g., Partial Directed Coherence - PDC - for directed connectivity) [1].

- Generate Surrogate Data: Create a large number (e.g., 1000) of surrogate datasets from the subject's original time series using a phase-shuffling procedure. This preserves the power spectrum but disrupts any true temporal correlations, creating a null model [1].

- Estimate Null Distribution: Recalculate the connectivity matrix for each of the surrogate datasets.

- Determine Threshold: For each pairwise connection, determine a critical threshold (e.g., the 95th percentile) from its corresponding null distribution.

- Apply Threshold and Correct: Threshold the subject's original connectivity matrix against these critical values. Apply a multiple comparisons correction (e.g., False Discovery Rate - FDR) to the resulting p-values [1].

- Form Adjacency Matrix: The statistically validated, binary adjacency matrix consists of all connections that survived the significance threshold and multiple comparisons correction.

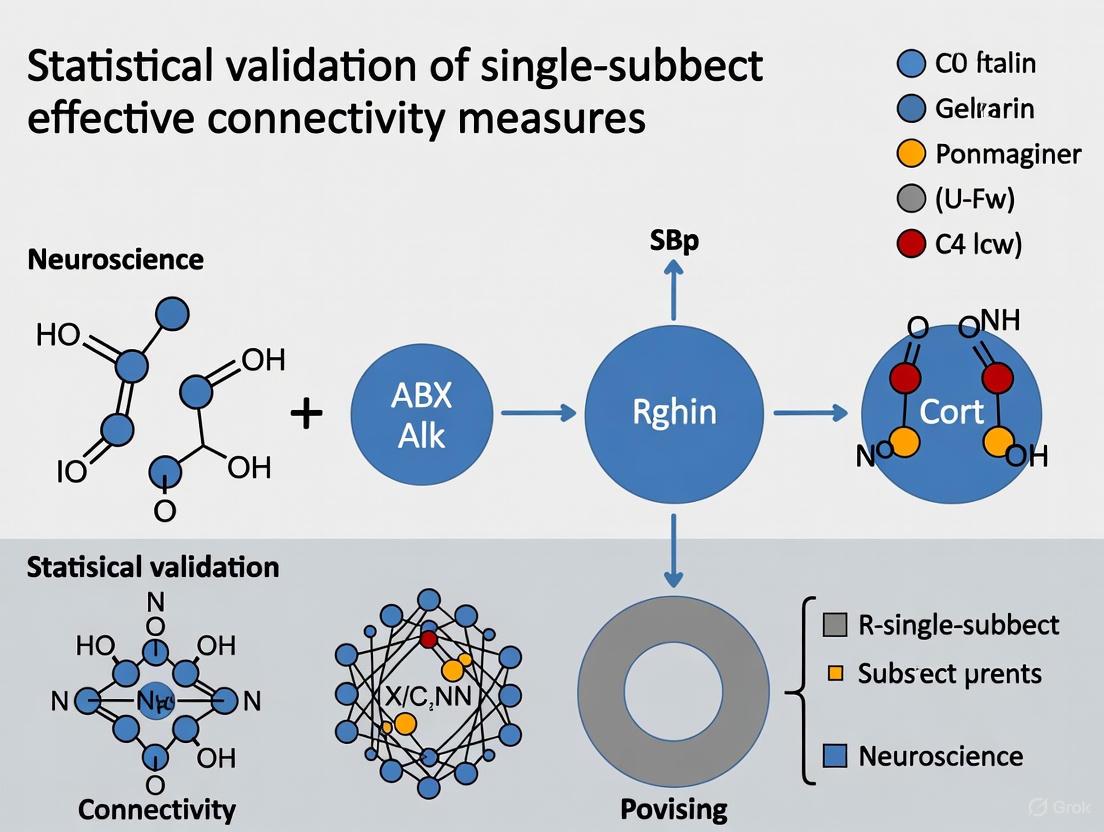

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Protocol 2: Intra-Individual Correlation Analysis for Longitudinal Single-Subject Studies

Purpose: To quantify the correlation structure of brain measures (functional or structural) within a single individual over time [4]. Methodology:

- Data Collection: Acquire repeated neuroimaging scans (e.g., fMRI for functional data, structural MRI for volume) from a single individual across multiple sessions over an extended period (e.g., months or years) [4].

- Feature Extraction: For each session, extract a feature vector representing the brain measure of interest (e.g., Regional Homogeneity (ReHo) values across brain regions, or Gray Matter Volume (GMV) for a set of anatomical parcels) [4].

- Calculate Correlation Matrix: Compute a correlation matrix (e.g., using Pearson's correlation) where each element represents the correlation of a specific brain measure between two regions across all the individual's scanning sessions.

- Analysis: The resulting intra-individual correlation matrix reflects how different brain regions co-vary within that person over time. This can be compared to inter-individual correlation matrices or used to track changes related to learning, therapy, or disease progression within the subject [4].

The following diagram illustrates the data flow for this protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key analytical "reagents" – computational tools and frameworks – essential for single-subject connectivity research.

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Phase Shuffling Algorithm | A computational procedure to generate surrogate data that destroys temporal correlations while preserving signal properties, essential for creating a subject-specific null model for statistical testing [1]. |

| Multiple Comparison Correction (FDR) | A statistical framework (False Discovery Rate) applied after multiple univariate tests to control the probability of false positives when validating thousands of connections in a network [1]. |

| pyspi Library | A Python library that provides a standardized implementation of 239 pairwise interaction statistics, enabling researchers to benchmark and select the optimal metric for their specific question [2]. |

| Longitudinal Single-Subject Datasets | Unique datasets comprising many repeated scans of a single individual over time, which serve as a critical resource for developing and validating intra-individual correlation methods [4]. |

| Graph Theory Indices | Mathematical measures (e.g., small-worldness, centrality) borrowed from network science to quantify the topographical properties of an individual's connectivity network [1]. |

Defining Single-Subject Functional Connectivity Fingerprints

What is a functional connectivity fingerprint?

A functional connectivity fingerprint is a unique, reproducible pattern of functional connections within an individual's brain that can be used to identify that person from a larger population. It is derived from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data by calculating the correlation between the timecourses of different brain regions, creating a connectome that is intrinsic and stable for each individual [8].

What is the core thesis regarding their statistical validation?

The core thesis is that while functional connectivity fingerprints are robust and reliable for identifying individuals, their statistical validation must be carefully addressed, as the same distinctive neural signatures used for identification are not necessarily directly predictive of individual behavioural or cognitive traits. This necessitates specific methodological and statistical considerations for single-subject analyses [9].

Key Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Fingerprint Identification

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for establishing a functional connectivity fingerprint.

Detailed Methodology: [8]

- Data Acquisition: Collect fMRI data from multiple subjects across several scanning sessions. The Human Connectome Project (HCP) protocol, used in foundational studies, involves scanning each subject over two days, including both rest sessions and task sessions (e.g., working memory, motor, language).

- Preprocessing: Perform standard fMRI preprocessing steps (motion correction, distortion correction, coregistration, normalization) using software like fMRIPrep [10].

- Brain Parcellation: Define nodes using a functional brain atlas (e.g., a 268-node atlas derived from a healthy population).

- Connectivity Matrix Construction: For each subject and session, calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between the timecourses of every pair of nodes. This results a symmetrical 268x268 connectivity matrix representing the strength of each connection (edge).

- Identification Algorithm:

- Designate one set of scans as the "target" and another as the "database."

- Iteratively, select one individual's connectivity matrix from the target set and compare it against every matrix in the database.

- Similarity is defined as the Pearson correlation between the vectors of all edge values.

- The database matrix with the highest correlation to the target is considered a match.

- Validation: Success rate is measured as the percentage of correctly identified subjects. Statistical significance is assessed using non-parametric permutation testing (e.g., 1,000 iterations) to confirm that accuracy exceeds chance levels [8].

Protocol for Behavioural Prediction

The following diagram contrasts the workflows for fingerprinting and behavioural prediction, highlighting their distinct features.

Detailed Methodology (Connectome-based Predictive Modeling, CPM): [9]

- Data Collection: Acquire resting-state fMRI data and behavioural measures (e.g., fluid intelligence scores) for a cohort of subjects.

- Feature Selection: Identify edges in the functional connectome that are significantly correlated (at a defined p-value threshold, e.g., p < 0.01) with the behavioural measure of interest. This creates a "positive" network (edges positively correlated with behaviour) and a "negative" network (edges negatively correlated).

- Model Training: For each subject, calculate a summary score by summing the strength of all edges in the positive network and subtracting the sum of the strength of all edges in the negative network. Use a cross-validated model (e.g., linear regression) to relate this summary score to the actual behavioural measure.

- Validation: Test the model on held-out subjects to evaluate the correlation between predicted and measured behavioural scores.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Low Identification Accuracy or Unreliable Fingerprints

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low identification accuracy between sessions. | Insufficient fMRI data quantity (scan duration). | Increase scanning time. Reliability improves proportionally to 1/sqrt(n). Aim for at least 25 minutes of BOLD data for reliable single-subject metrics [11]. |

| High motion artifacts or other noise contamination. | Rigorous denoising. Use tools like fMRIPrep with recommended flags (e.g., --low-mem). Perform quality control (QC) to check the distribution of functional connectivity values; it should be centered and similar across subjects. Strong global correlation can indicate noise [12] [10]. |

|

| Sub-optimal network or parcellation choice. | Focus on discriminative networks. The Frontoparietal (FPN) and Medial Frontal/Default Mode (DMN) networks are most distinctive. Use a combination of these higher-order association networks for analysis [8]. |

Problems in Single-Subject vs. Group Comparisons

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No significant findings in a single patient vs. controls, even in lesioned areas. | Lack of statistical power due to single-case design. | Use subject-specific models. For patient studies, consider that the standard single-subject vs. group test may be underpowered. Techniques like Dynamic Connectivity Regression (DCR) that model change points within a single subject can be more informative [13]. |

| Unexpected, high global connectivity in a single subject. | Incomplete removal of artifacts (e.g., motion, scanner noise). | Re-inspect denoising. This pattern is a hallmark of noise. Re-run preprocessing and denoising steps. Ensure the patient's FC histogram after denoising is qualitatively similar to that of controls [12]. |

Discrepancy Between Fingerprinting and Behavioural Prediction

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Highly discriminatory edges fail to predict behaviour. | This is an expected finding. | Do not assume overlap. The neural systems supporting identification and behavioural prediction are highly distinct. Select features specific to your analysis goal: use the most discriminatory edges for fingerprinting and behaviour-correlated edges for prediction [9]. |

Essential Research Reagents & Tools

Table: Key Resources for Single-Subject Connectivity Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep [10] | Software Pipeline | Robust and standardized preprocessing of fMRI data, reducing inter-study variability and improving reproducibility. |

| CONN Functional Connectivity Toolbox [12] | Software Toolbox | A comprehensive MATLAB/SPM-based toolbox for functional connectivity analysis, including seed-based, ROI-based, and ICA methods. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Datasets [8] [14] | Data Resource | High-quality, multi-session fMRI datasets from healthy adults, essential for method development and validation. |

| 268-Node Functional Atlas [8] | Brain Parcellation | A pre-defined atlas of 268 brain nodes, enabling standardized construction of whole-brain connectivity matrices. |

| Graphical Lasso (glasso) [13] | Algorithm | Estimates sparse precision matrices (inverse covariance), crucial for handling high-dimensional data when constructing connectivity graphs. |

| Dynamic Connectivity Regression (DCR) [13] | Algorithm | A data-driven method for detecting change points in functional connectivity within a single subject's time series. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How much scanning time is needed to obtain a reliable single-subject connectivity fingerprint?

Reliability increases with imaging time, proportional to 1/sqrt(n). Dramatic improvements are seen with up to 25 minutes of data, with smaller gains beyond that. For high-fidelity fingerprints, studies often use 30-60 minutes of data across multiple sessions [11].

Q2: Can I use a pre-skull-stripped T1w image with fMRIPrep? It is not recommended. fMRIPrep is designed for raw, defaced T1w images. Using pre-processed images can lead to unexpected downstream consequences due to unknown preprocessing steps [10].

Q3: My fMRIPrep run is hanging or crashing. What should I check?

This is often a memory issue. First, try using the --low-mem flag. Second, ensure your system has sufficient RAM allocated (≥8GB per subject is recommended). On Linux, a Python bug can cause processes to be killed when memory is low; allocating more memory resolves this [10].

Q4: Are the same functional connections that identify an individual also predictive of their cognitive abilities, like fluid intelligence? Not directly. While early studies suggested an overlap, systematic analyses reveal that discriminatory and predictive connections are largely distinct on the level of single edges, network interactions, and topographical distribution. The frontoparietal network is involved in both, but the specific edges are different [9].

Q5: How do I handle the statistical analysis of single-subject data, given its unique challenges? Different statistical methods (e.g., C-statistic, two-standard deviation band method) can yield different interpretations of the same single-subject data. The choice of method is critical, and the overlap in graphed data is a key predictor of disagreement between tests. The analytical approach must be selected a priori and justified [15].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How much resting-state fMRI data is required to obtain reliable functional connectivity measurements in a single subject?

A primary challenge in single-subject research is determining the minimum scanning time needed for reliable functional connectivity (FC) measurements. Insufficient data leads to poor reproducibility, while excessive scanning is impractical.

- Evidence-Based Guideline: Studies have quantitatively demonstrated that reliability improves proportionally to

1 / sqrt(n), wherenis the imaging time [11]. - Recommendations:

- ~25 minutes of BOLD imaging time is required before individual connections can reliably discriminate a subject from a control group [11] [16].

- Dramatic improvements in reliability are seen with up to 25 minutes of data, with smaller incremental gains for additional time [11].

- Functional connectivity "fingerprints" for an individual and a population begin to diverge at approximately 15 minutes of imaging time [11].

Table 1: Impact of BOLD Imaging Time on Single-Subject FC Reliability

| Imaging Time | Reliability and Capability |

|---|---|

| ~15 minutes | Individual's functional connectivity "fingerprint" begins to diverge from the population average [11]. |

| ~25 minutes | Individual connections can reliably discriminate a subject from a healthy control group [11] [16]. |

| >25 minutes | Continued, though smaller, improvements in reliability; high reliability even at 4 hours [11]. |

FAQ 2: What statistical methods can improve the reliability and interpretability of single-subject connectivity measures?

The choice of pairwise interaction statistic fundamentally impacts the resulting FC matrix and its properties. While Pearson’s correlation is the default, numerous other methods can be optimized for specific research goals [2].

- Key Insight: A 2025 benchmarking study of 239 pairwise statistics found substantial quantitative and qualitative variation across FC methods [2]. No single method is best for all applications.

- Method Recommendations:

- Precision/Inverse Covariance: Attempts to model and remove common network influences to emphasize direct relationships. It shows strong correspondence with structural connectivity and is closely aligned with multiple biological similarity networks [2].

- Covariance-based statistics: Display expected inverse relationships with physical distance and positive relationships with structural connectivity, making them a robust default choice [2].

- Supervised Classifiers (e.g., Multi-Layer Perceptron): Can be trained to estimate resting-state network topography in individuals, providing consistent results across subjects [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Pairwise Statistics for Functional Connectivity Mapping

| Method Family | Key Mechanism | Strengths and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Covariance (e.g., Pearson's) | Measures zero-lag linear coactivation. | Robust default; good structure-function coupling; widely used and understood [2]. |

| Precision/Inverse Covariance | Models and removes shared network influence to estimate direct relationships. | High structure-function coupling; strong alignment with biological similarity networks; identifies prominent hubs in transmodal regions [2]. |

| Information Theoretic | Captures non-linear and complex dependencies. | Sensitive to underlying information flow mechanisms beyond linear correlation [2]. |

| Spectral | Analyzes interactions in the frequency domain. | Shows mild-to-moderate correlation with many other measures, offering a different perspective [2]. |

FAQ 3: How can we differentiate intra-individual from inter-individual sources of variability in connectivity studies?

A significant challenge is attributing observed correlation patterns to state-like, intra-individual factors versus stable, trait-like, inter-individual differences. Confounding these factors reduces interpretability.

- Experimental Approach: Leverage unique longitudinal datasets with repeated scans from the same individuals over extended periods (e.g., over 15 years) [4].

- Methodology:

- Calculate intra-individual correlations by computing correlation matrices within each participant and then averaging these matrices across participants. This minimizes individual differences and highlights variability due to aging or state-like effects [4].

- Calculate inter-individual correlations at each time point and average these matrices across ages. This focuses on trait-like variability while controlling for factors like age [4].

- Key Findings: Studies using this approach have shown that intra-individual correlations in functional measures like regional homogeneity (ReHo) are primarily driven by state-like variability, while correlations in structural measures like gray matter volume are more influenced by aging [4].

Experimental Protocol: Longitudinal Intra-Individual Correlation Analysis

Objective: To dissect the contributions of intra-individual (state-like) and inter-individual (trait-like) factors to brain connectivity patterns.

Materials:

- Dataset: Longitudinal neuroimaging data (e.g., structural MRI and resting-state fMRI) from a cohort or a single individual scanned repeatedly over many years [4].

- Software: Standard neuroimaging processing tools (e.g., FSL, SPM) for image preprocessing, normalization, and feature extraction (e.g., Regional Homogeneity (ReHo), Gray Matter Volume (GMV)) [4].

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: For each scan session, preprocess T1-weighted and resting-state fMRI data. This includes motion correction, normalization to a standard space (e.g., MNI), and calculation of relevant metrics (GMV from structural images, ReHo or time-series from functional images) [4].

- Intra-Individual Correlation Matrix Calculation:

- For each participant with multiple longitudinal scans, extract a feature vector (e.g., GMV values across brain regions or average ReHo within networks) for each session.

- Calculate a correlation matrix (e.g., between-region GMV correlations) using all sessions from that single participant.

- Repeat for all participants.

- Average these individual correlation matrices across all participants to create a final intra-individual correlation matrix [4].

- Inter-Individual Correlation Matrix Calculation:

- At each available time point (age), extract the feature vectors for all participants.

- Calculate a correlation matrix (e.g., between-region GMV correlations) using data from all participants at that specific age.

- Repeat for all time points.

- Average these cross-sectional correlation matrices across all ages to create a final inter-individual correlation matrix [4].

- Comparison and Validation: Compare the intra- and inter-individual correlation matrices against a reference, such as resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) derived from traditional fMRI. This helps validate the patterns and interpret their biological meaning [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Single-Subject Connectivity Research

| Item / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Datasets | Datasets containing repeated scans of the same individual(s) over long time spans (years). | Essential for disentangling intra-individual (state) from inter-individual (trait) variability in connectivity [4]. |

| High Temporal Resolution BOLD fMRI | Functional MRI data acquired over extended, continuous periods (≥15-25 minutes). | Fundamental for achieving reliable single-subject connectivity measurements and individual "fingerprinting" [11] [16]. |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) Classifier | A supervised artificial neural network trained to associate BOLD correlation maps with specific RSN identities. | Provides reliable mapping of resting-state network topography in individual subjects, consistent across individuals [17]. |

| Wavelet Transform Feature Extraction | A mathematical tool applied to voxel-based morphology (VBM) volumes to extract voxel-wise feature vectors. | Enables the construction of individual white matter structural covariance connectivity maps from T1-weighted anatomical MRI [18]. |

| PySPI Package | A software library containing a large collection of pairwise statistical measures for estimating functional connectivity. | Allows researchers to benchmark and select from 239 pairwise statistics to optimize FC mapping for their specific neurophysiological question [2]. |

| Structured Brain Atlases | Predefined parcellations of the brain into distinct regions or networks (e.g., Schaefer atlas, Yeo RSNs). | Provides a standardized framework for defining network nodes, ensuring consistency and comparability across studies [2] [18]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions when Analyzing High-Order Interactions

| Problem Area | Specific Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Validation | High false positive rates in single-subject HOI significance testing [19] [20] | Spurious connectivity from finite data size, acquisition noise, or non-independent statistical tests [19] [20] | Implement surrogate data analysis to test significance against uncoupled signals, and bootstrap to generate confidence intervals for individual estimates [19]. |

| Data Analysis & Power | Inability to detect significant HOIs; lack of statistical power [21] | Low signal-to-noise ratio; insufficient data points; small activation areas [21] | Apply advanced statistical frameworks like LISA, which uses non-linear spatial filtering to enhance power while preserving spatial precision and controlling FDR [21]. |

| Method Selection & Interpretation | HOI measures do not outperform traditional pairwise methods [22] | Global HOI indicators may not capture localized effects; inappropriate parcellation [22] | Focus on local HOI indicators (e.g., violating triangles, homological scaffolds) for task decoding and individual identification, as they often show greater improvement over pairwise methods than global indicators [22]. |

| Result Reporting & Replicability | Findings are difficult to interpret or replicate [23] [24] | Incomplete reporting of methodological details; use of non-reproducible, GUI-based workflows for visualization [23] [24] | Adopt code-based visualization tools (e.g., in R or Python) for replicable figures. Report all details: ROIs, statistical thresholds, normalization methods, and software parameters [23] [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why should I use high-order interaction measures instead of well-established pairwise connectivity?

Pairwise functional connectivity, while foundational, is inherently limited to detecting relationships between two brain regions. There is mounting evidence that complex systems like the brain contain high-order, synergistic subsystems where information is shared collectively among three or more regions and cannot be reduced to pairwise correlations [19] [22]. These HOIs are proposed to be fundamental to the brain's complexity and functional integration [19].

Key Advantages of HOIs:

- Capture Synergy: HOIs can identify synergistic information—where the joint state of multiple variables provides more information than the sum of their parts—which is missed by pairwise analyses [19].

- Improved Performance: Studies show that HOI approaches can significantly enhance the ability to decode cognitive tasks, improve the identification of individuals based on their brain activity (brain fingerprinting), and strengthen the association between brain activity and behavior compared to pairwise methods [22].

- Reveal Hidden Structures: HOIs can unveil a "shadow structure" of brain coordination that remains hidden when using traditional pairwise graph models [19].

FAQ 2: What are the core methodological steps for a single-subject HOI analysis with statistical validation?

A robust single-subject methodology for HOI involves specific steps for estimation and statistical validation [19].

Experimental Protocol: Single-Subject HOI Analysis

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Acquire resting-state or task-based fMRI time series. Standard pre-processing steps (slice-time correction, motion realignment, normalization, etc.) should be applied. It is critical to specify all preprocessing parameters and software used for reproducibility [23].

- Network Construction: Define a set of Q brain regions of interest (ROIs) using an anatomical or functional atlas. Extract the average time series from each ROI.

- Calculate Connectivity Measures:

- Pairwise Connectivity: Compute pairwise functional connectivity (e.g., using Mutual Information or correlation) between all pairs of ROIs [19].

- High-Order Connectivity: Compute a high-order interaction measure, such as O-information, to quantify whether a group of regions interacts redundantly or synergistically [19].

- Statistical Validation (Surrogate & Bootstrap Analysis):

- Surrogate Data Analysis: Generate multiple surrogate time series that mimic the individual properties (e.g., power spectrum) of the original signals but are otherwise uncoupled. Recompute the connectivity measures on these surrogate datasets to create a null distribution. The original connectivity value is considered significant if it exceeds a pre-defined percentile (e.g., 95th) of this null distribution [19].

- Bootstrap Analysis: Generate multiple bootstrap resamples of the original time series to estimate the sampling distribution of your connectivity metrics. Use this to construct confidence intervals for the individual estimates, allowing for comparison across different experimental conditions [19].

FAQ 3: How can I avoid non-independence and inflation of effect sizes in my analysis?

Non-independence, or "double-dipping," occurs when data used to select a region of interest (ROI) are then used again to perform a statistical test within that same ROI, leading to inflated effect sizes [20].

Solution: Independent Functional Localizer Use a leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) cross-validation procedure for group studies [20].

- Iteratively leave one subject out of the initial group-level analysis that defines the ROIs.

- Apply the ROIs defined by the rest of the group to the left-out subject's data to extract effect sizes (e.g., beta weights).

- Repeat for every subject. This ensures that the ROI definition is independent of the data on which the statistical test is performed, eliminating effect size inflation [20].

FAQ 4: My HOI analysis didn't yield better results than pairwise analysis. What might be wrong?

This is a known scenario. Research indicates that the advantage of HOIs can be spatially specific [22].

Potential Issues and Fixes:

- Global vs. Local Indicators: You might be relying solely on global, whole-brain HOI indicators. Instead, focus on local HOI indicators, such as:

- Violating Triangles: Triangles in the network where the triple interaction is stronger than expected from the pairwise edges, indicating a genuine higher-order dependency [22].

- Homological Scaffold: A weighted graph that highlights the importance of edges in forming mesoscopic topological structures (like cycles) within the higher-order co-fluctuation landscape [22].

- Check Your Parcellation: The choice of brain atlas and the number of regions can significantly impact the detection of HOIs. Experiment with different parcellation schemes.

FAQ 5: What are the essential reagents and tools for conducting HOI research?

Research Reagent Solutions for HOI Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| fMRI Data | The primary input; typically resting-state or task-based BOLD time series from a sufficient number of subjects to ensure power [22]. |

| Brain Parcellation Atlas | A predefined map dividing the brain into regions of interest (ROIs) from which time series are extracted (e.g., HCP's 119-region cortical & subcortical atlas) [22]. |

| Information Theory Metrics | Mathematical tools, such as O-information, used to quantify the redundancy or synergy between multiple time series, defining the HOIs [19]. |

| Topological Data Analysis (TDA) | A computational framework that studies the shape of data. It can be used to reconstruct instantaneous HOI structures from fMRI time series [22]. |

| Surrogate & Bootstrap Algorithms | Computational methods for generating null models (surrogates) and confidence intervals (bootstrap) to statistically validate HOI measures on a single-subject level [19]. |

| Code-Based Visualization Tools | Programmatic tools (e.g., in R or Python) for generating reproducible and publication-ready visualizations of complex HOI results, crucial for clear communication [24]. |

| Statistical Inference Software | Software packages or custom code implementing advanced statistical methods like LISA for improved power and controlled false discovery rates in activation mapping [21]. |

Statistical vs. Arbitrary Thresholding in Network Construction

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Unreliable Single-Subject Network Maps

Problem: Functional connectivity maps for a single subject change dramatically with different arbitrary thresholds, making the results unreliable for clinical decision-making.

Solution:

- Step 1: Assess the threshold-dependence of your reliability measures using Receiver Operating Characteristic-Reliability (ROC-r) or Rombouts overlap (RR) analysis [25].

- Step 2: Generate reliability plots that show how your chosen reliability metric varies across different threshold levels for the specific subject [25].

- Step 3: Use these data-driven plots to identify and select the optimal threshold that maximizes reliability for that individual subject, rather than applying a fixed threshold across all subjects [25].

Guide 2: Resolving Spurious Connections in Structural Connectomes

Problem: Probabilistic tractography produces structural networks that appear almost fully connected, containing many false-positive connections that are biologically implausible [26].

Solution:

- Step 1: Apply consistency-based thresholding, which retains only connections with weights that show high consistency across subjects, as these are less likely to be spurious [26].

- Step 2: Alternatively, use proportional-thresholding (consensus-thresholding) to retain only connections present in a set proportion of subjects [26].

- Step 3: Implement more stringent thresholding (higher sparsity levels of 70-90%) as this has been shown to remove more spurious connections while preserving biologically meaningful connectivity information [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I use the same fixed threshold for all my single-subject analyses?

Using fixed thresholds in single-subject fMRI analyses is problematic because reliability measures vary dramatically with threshold, and this variation depends strongly on the individual tested. Group-level reliability is a poor predictor of single-subject behavior, so thresholds must be optimized on a case-by-case basis for robust individual-level activation maps [25].

FAQ 2: What is the fundamental difference between arbitrary and statistically validated thresholds?

Arbitrary thresholding methods (like fixing edge density or using uniform thresholds) do not account for the intrinsic statistical significance of the connectivity estimator, potentially retaining connections that occurred by chance. Statistical validation uses procedures like phase shuffling to create null case distributions, retaining only connections statistically different from this null case, thus providing a principled approach to discarding spurious links [1].

FAQ 3: How does threshold choice affect detection of biologically meaningful effects?

More stringent thresholding methods (retaining only 30% of connections vs. 68.7%) have been shown to yield stronger associations with demographic variables like age, indicating they may be more accurate in identifying true white matter connections. The connections discarded by appropriate thresholding show significantly smaller age-associations than those retained [26].

FAQ 4: What are the trade-offs between false positives and false negatives in clinical thresholding?

In clinical contexts like presurgical planning, false negatives (reporting an area as not active when it is) have more profound consequences than false positives, as they could lead to resection of eloquent cortex. Therefore, thresholding methods should provide a good balance between both error types rather than perfectly controlling for only one [27].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Thresholding Methods and Their Effects on Network Properties

| Thresholding Method | Key Principle | Typical Density/Level | Effect on Biological Sensitivity | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency Thresholding | Retains connections with high inter-subject consistency [26] | 30% connection retention [26] | Stronger age-associations (0.140 ≤ |β| ≤ 0.409) [26] | Large sample sizes; population studies |

| Proportional Thresholding | Retains connections present in set proportion of subjects [26] | 68.7% connection retention [26] | Weaker age-associations (0.070 ≤ |β| ≤ 0.406) [26] | Multi-subject studies; comparative analysis |

| Statistical Validation (Shuffling) | Uses null case distribution via phase shuffling [1] | p < 0.05 with FDR correction [1] | Discards spurious links; reveals true topography [1] | Single-subject analysis; clinical applications |

| Fixed Edge Density | Fixes number of edges across networks [1] | Varies by study [1] | May retain spurious connections [1] | Network topology comparison |

Table 2: Thresholding Impact on Single-Subject fMRI Reliability Metrics

| Reliability Measure | Definition | Threshold Dependence | Optimal Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rombouts Overlap (RR) | Ratio of voxels active in both replications to average active in each [25] | High variation (0.0-0.7) across thresholds [25] | Simple, empirical reliability assessment |

| ROC-reliability (ROC-r) | Area under curve of true vs. false positive rates [25] | Varies dramatically with threshold [25] | Data-driven threshold optimization |

| Jaccard Overlap (RJ) | Proportion of active voxels in either replication that are active in both [25] | Similar threshold dependence as RR [25] | Conservative reliability assessment |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Statistical Validation of Functional Connectivity Using Shuffling Procedure

Purpose: To extract adjacency matrices from functional connectivity patterns using statistical validation rather than arbitrary thresholding [1].

Materials: Multivariate time series data (EEG, MEG, or fMRI), computing environment with MVAR modeling capability.

Procedure:

- Estimate functional connectivity using a multivariate estimator like Partial Directed Coherence (PDC) [1].

- Generate surrogate data sets by shuffling the phases of original traces to disrupt temporal relations while preserving individual signal properties [1].

- Iterate the connectivity estimation multiple times on different surrogate data sets to construct the empirical null case distribution of the connectivity estimator [1].

- Extract threshold values for each node pair, direction, and frequency sample by applying a percentile (e.g., 95th) to the null distribution [1].

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction to account for multiple comparisons [1].

- Construct the final adjacency matrix where edges exist only if they are statistically different from the null case distribution [1].

Protocol 2: Consistency Thresholding for Structural Connectomes

Purpose: To remove spurious connections from structural networks derived from diffusion MRI and probabilistic tractography [26].

Materials: Diffusion MRI data from multiple subjects, probabilistic tractography pipeline, brain parcellation atlas.

Procedure:

- Construct individual 85×85 node whole-brain structural networks for all subjects using probabilistic tractography [26].

- Apply alternative network weightings (streamline count, fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, or NODDI metrics) [26].

- Calculate consistency of connection weights across subjects [26].

- Retain only connections with the highest inter-subject consistency, implementing various levels of network sparsity (e.g., 30%, 70%) [26].

- Compare network measures (mean edge weight, characteristic path length, efficiency, clustering coefficient) against external variables like age to validate biological sensitivity [26].

Methodological Visualizations

Statistical vs. Arbitrary Thresholding Workflow

Single-Subject Threshold Optimization Process

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for Connectivity Research

| Research Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Tractography | Estimates structural connectivity from diffusion MRI data [26] | Structural connectome construction |

| Partial Directed Coherence (PDC) | Multivariate spectral measure of directed influence between signals [1] | Functional connectivity estimation |

| Phase Shuffling Procedure | Generates surrogate data for null distribution construction [1] | Statistical validation of connections |

| Gamma-Gaussian Mixture Modeling | Models T-value distributions in statistical parametric maps [27] | Adaptive thresholding for single-subject fMRI |

| Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging (NODDI) | Advanced microstructural modeling beyond diffusion tensor [26] | Alternative network weighting |

| ROC-Reliability (ROC-r) Analysis | Assesses threshold-dependence of classification reliability [25] | Single-subject threshold optimization |

Advanced Statistical Frameworks for Individual Connectivity Assessment

Surrogate Data Analysis for Testing Significance of Connections

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't I use a baseline of zero to test the significance of my connectivity estimates? Factors such as background noise and sample size-dependent biases often make it inappropriate to treat zero as a baseline level of connectivity. Surrogate data generated by destroying the covariance structure of your original data provide a more accurate baseline for statistical testing, helping you determine if observed connectivity reflects genuine interactions [28] [19].

2. What is the main advantage of using surrogate data analysis for single-subject research? In clinical or personalized neuroscience, the goal is often to draw conclusions from an individual's brain signals to optimize treatment plans. Surrogate data analysis allows for statistical validation of connectivity metrics (both pairwise and high-order) on a single-subject level, which is essential for reliable assessment of an individual's underlying condition [19].

3. My connectivity values are positive. Does this mean they are statistically significant? Not necessarily. Spurious connectivity patterns can arise from finite data size effects, acquisition errors, or other factors even when no true coupling exists between signals. Statistical testing with surrogate data is required to confirm that your estimates are significantly greater than those expected by chance [19] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Common Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-significant results | The estimated connectivity is not stronger than the baseline level of chance correlations present in the data. | Generate a null distribution using a large number of surrogate datasets (e.g., 1000). Your true connectivity is significant if it exceeds a pre-defined percentile (e.g., 95th) of this null distribution [28]. |

| High computational demand | Generating a large number of surrogate datasets for robust statistical testing can be computationally intensive. | Reduce the data dimensionality first, use a subset of epochs for an initial test, or leverage high-performance computing resources if available. The mne_connectivity Python library is optimized for such analyses [28]. |

| Difficulty interpreting high-order interactions | High-order interactions (HOIs) describe complex, synergistic information shared among three or more network nodes, which is conceptually different from standard pairwise connectivity. | Refer to multivariate information theory measures like O-information (OI) to quantify whether a system is redundancy- or synergy-dominated. Surrogate and bootstrap analyses can then statistically validate these HOIs [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Connectivity with Surrogates

The following methodology details how to assess whether connectivity estimates are significantly greater than a baseline level of chance, using a workflow implemented in the mne_connectivity Python library [28].

1. Load and Preprocess the Data

- Begin by loading your raw neural data (e.g., MEG, EEG, or fMRI data).

- Apply standard pre-processing steps such as filtering to a frequency band of interest (e.g., 1-35 Hz) and epoching the data around the events of interest.

- To reduce computational time, you may opt to resample the data to a lower sampling rate and use only a subset of the available epochs [28].

2. Compute Original Connectivity

- Calculate the functional connectivity from your preprocessed, original data. For spectral connectivity, you can use functions like

spectral_connectivity_epochs. - This step provides you with the "true" connectivity matrix that you want to test for significance [28].

3. Generate Surrogate Data

- Create surrogate datasets from your original epoched data using the

make_surrogate_data()function. - This function works by shuffling the data independently across channels and epochs, which destroys the temporal relationships between signals while preserving the individual time-series properties [28].

- It is common to generate a large number of surrogate datasets (e.g., 1000) to build a reliable null distribution.

4. Compute Surrogate Connectivity

- For each surrogate dataset you generated, compute the connectivity estimate using the same method and parameters as in Step 2.

- This will give you a distribution of connectivity values that represent the "baseline" or "chance" level of connectivity expected from data with no genuine coupling [28].

5. Perform Statistical Testing

- Compare your original connectivity estimate from Step 2 against the null distribution of surrogate connectivity estimates from Step 4.

- A typical approach is to use a one-tailed test. Your true connectivity is considered statistically significant if it is greater than the 95th percentile (for α = 0.05) of the surrogate distribution [28].

Summary of Key Parameters

| Step | Key Parameter | Example / Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Preprocessing | Filter Range | 1-35 Hz |

| Resampling Rate | 100 Hz (to reduce compute) | |

| Number of Epochs | 30 (subset to speed up) | |

| 2. Original Connectivity | Method | spectral_connectivity_epochs |

| 3. Surrogate Data | Number of Surrogates | 1000 (for a robust null) |

| Method | make_surrogate_data() (channel shuffling) |

|

| 5. Significance Testing | Alpha (α) | 0.05 |

| Percentile Threshold | 95th |

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| MNE-Connectivity Library | A Python library specifically designed for estimating and statistically testing connectivity in neural data. It provides functions for generating surrogate data and multiple connectivity metrics [28]. |

| Surrogate Data (via channel shuffling) | The core "reagent" for creating a null hypothesis. It destroys true inter-channel coupling while preserving the internal structure of individual signals, allowing for the creation of a baseline connectivity distribution [28] [19]. |

| Mutual Information (MI) | A measure from information theory used to investigate pairwise functional connectivity by quantifying the information shared between two brain regions or signals [19]. |

| O-Information (OI) | A multivariate information measure used to investigate high-order interactions (HOIs). It evaluates whether a system of three or more variables is dominated by redundant or synergistic information sharing [19]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling | A statistical technique used to generate confidence intervals for individual estimates of connectivity metrics, allowing for the assessment of their variability and the comparison across different experimental conditions [19]. |

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for performing surrogate data analysis to test the significance of connectivity estimates.

Significance Testing Logic

This diagram visualizes the decision-making process for determining statistical significance by comparing the original connectivity value to the surrogate-based null distribution.

Bootstrap Methods for Constructing Confidence Intervals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core principle behind bootstrapping for confidence intervals? Bootstrapping is a statistical procedure that resamples a single dataset with replacement to create many simulated samples. You calculate your statistic of interest on each resample, and the distribution of these bootstrap estimates is used to infer the variability and construct confidence intervals for the true population parameter. This method allows you to estimate the sampling distribution of a statistic empirically without relying on strong theoretical assumptions [30] [31].

2. Why is bootstrapping particularly useful in single-subject neuroimaging research? In single-subject functional connectivity studies, researchers often cannot collect large amounts of data from one individual due to practical constraints like scanner time and participant burden. Bootstrapping allows for robust statistical inference from the limited data available from a single subject. It is used to determine the reliability of connectivity measures, validate significant functional connections, and control for false positives without needing a large group of participants [19] [11] [32].

3. My bootstrap confidence intervals seem very wide. What could be the cause? Wide confidence intervals generally indicate high variability in your bootstrap estimates. In the context of single-subject connectivity, this can be caused by:

- Insufficient original data: The time series may be too short to capture a stable estimate of the connectivity pattern [11].

- High inherent variability: The brain's functional connectivity itself may be highly dynamic. Methods like Dynamic Connectivity Regression (DCR) can be used in such cases to detect change points before bootstrapping within stable periods [13] [33].

- Outliers or artifacts: Spikes or motion artifacts in the fMRI time series can severely impact the stability of bootstrap estimates and lead to false positives [33] [32].

4. How do I choose the number of bootstrap resamples (e.g., 1,000 vs. 10,000)? While more resamples generally lead to more stable results, there are diminishing returns. Evidence suggests that numbers of samples greater than 100 lead to negligible improvements in the estimation of standard errors [31]. For many applications, 1,000 to 10,000 resamples are sufficient. The original developer of the method suggested that even 50 resamples can provide fairly good standard error estimates. The choice can depend on the complexity of the statistic and the need for precision [31].

5. Can I use bootstrapping to compare connectivity measures across different experimental conditions in a single subject? Yes. By performing bootstrap analysis separately for data from each condition (e.g., rest vs. task), you can generate condition-specific confidence intervals for connectivity strengths. If the confidence intervals do not overlap, it suggests a statistically significant difference between conditions for that individual [19]. This approach is fundamental for personalized treatment planning and tracking changes within a subject over time [19] [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Test-Retest Reliability in Single-Subject Connectivity Fingerprints

Issue: The functional connectivity "fingerprint" of a single subject is not reproducible across multiple scanning sessions.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient imaging time | Check if reliability metrics (e.g., Dice coefficient, ICC) improve when more data points are aggregated. | Aggregate data across runs. One study found that 25 minutes of BOLD imaging time was required before individual connections could reliably discriminate an individual from a control group [11]. |

| High within-subject physiological variability | Examine correlations with daily factors (sleep, heart rate, stress). | Collect physiological and lifestyle data (e.g., via wearables). Account for this covariance in your models, as daily factors have been shown to affect functional connectivity [34]. |

| True dynamic connectivity | Use change point detection algorithms (e.g., DCR) to test for underlying non-stationarity. | If change points are found, perform bootstrap analysis on the stable segments between change points rather than on the entire time series [13] [33]. |

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Reliability:

- Data Acquisition: Collect a large number of repeated scans from a single subject across multiple sessions [11].

- Connectivity Matrix Calculation: For each scan, calculate a functional connectivity matrix (e.g., using correlation between region time series).

- Bootstrap Resampling: For a given amount of aggregated data (e.g., 5 min, 10 min, 25 min), repeatedly resample the scans with replacement and calculate the average connectivity matrix for each resample.

- Reproducibility Metric: Calculate the mean difference in correlation values between two independent bootstrap estimates. Plot this difference against the amount of imaging time used [11].

Problem: Bootstrap Intervals Indicate High False Positive Edges in Graphs

Issue: The bootstrap procedure for functional connectivity graphs yields many edges (connections) that are likely false positives.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Violation of sparsity assumption | The graphical lasso (glasso) may be mis-specified if the true precision matrix is not sparse. | Implement a double bootstrap procedure. First, use bootstrapping to identify change points. Then, within a stable partition, use a second bootstrap to perform inference on the edges of the graph, only retaining edges that appear in a high percentage (e.g., 95%) of bootstrap graphs [33]. |

| Contaminated data values | Inspect the fMRI time series for spikes or large motion artifacts. | Preprocess data to remove artifacts. The glasso technique can be severely impacted by a few contaminated values, increasing false positives [33]. |

| Inadequate similarity measures | Test different similarity measures (e.g., Jensen-Shannon divergence vs. Kullback-Leibler divergence). | In morphological network studies, Jensen-Shannon divergence demonstrated better reliability than Kullback-Leibler divergence. Test different measures for your specific data [35]. |

Experimental Protocol for False Positive Control:

- Bootstrap GLM Analysis: For a single subject's fMRI task data, generate a large number (e.g., 1000) of bootstrap resamples of the time series.

- Activation Mapping: Perform a standard General Linear Model (GLM) analysis on each bootstrap resample to create an activation map.

- Consensus Map: Create a final activation map that only includes voxels that appeared as active in a high proportion (e.g., >95%) of the bootstrap maps. This method has been shown to achieve 93% accuracy in detecting true active voxels without the need for spatial smoothing [32].

Problem: Unstable Estimates with High-Dimensional Data (e.g., many brain regions)

Issue: When the number of brain regions (variables) is large relative to the number of time points, bootstrap estimates of connectivity matrices become unstable.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The "p > n" problem | Check if the number of ROIs (p) is greater than the number of time points (n). | Use regularized regression techniques. Methods like the graphical lasso (glasso), which estimates a sparse inverse covariance matrix, are essential for high-dimensional bootstrap inference in connectivity research [13] [33]. |

| Poor choice of parcellation atlas | Test the stability of results across different parcellation schemes. | Use a higher-resolution brain atlas. Studies on morphological networks found that higher-resolution atlases led to more stable and reliable network measures [35]. |

| Insufficient sample size for stability | Perform a sample size-varying stability analysis. | Ensure an adequate number of participants if building a reference model. One study found that morphological similarity networks required a sample size of over ~70 participants to achieve stability [35]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material / Tool | Function in Bootstrap Analysis for Connectivity |

|---|---|

| Graphical Lasso (glasso) | A regularization technique that estimates a sparse inverse covariance (precision) matrix. It is crucial for constructing stable functional connectivity networks when the number of brain regions is large [13] [33]. |

| Dynamic Connectivity Regression (DCR) | A data-driven algorithm to detect unknown change points in a time series of functional connectivity. It allows for bootstrap analysis to be performed on statistically stationary segments, improving validity [13] [33]. |

| Surrogate Data | Artificially generated time series that mimic the individual properties (e.g., power spectrum) of the original data but are otherwise uncoupled. Used to create a null distribution for testing the significance of pairwise connectivity measures [19]. |

| High-Resolution Brain Parcellation | A fine-grained atlas dividing the brain into many distinct regions of interest (ROIs). Using a higher-resolution atlas (e.g., with 200+ regions) has been shown to improve the test-retest reliability of derived network measures [35]. |

| Fisher z-Transform | A mathematical transformation applied to correlation coefficients (e.g., from functional connectivity matrices) to make their distribution approximately normal, which is beneficial for subsequent statistical testing and bootstrap inference [11]. |

Experimental Workflow & Signaling Pathways

Bootstrap Workflow for Single-Subject Connectivity Confidence Intervals

Workflow for Single-Subject Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

Signaling Pathway for Statistical Validation

Pathway for Statistical Validation of Connectivity

Dynamic Connectivity Regression for Change Point Detection

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inability to Detect Significant Change Points in Dynamic Functional Connectivity

Problem: When analyzing an individual subject's fMRI time series, your dynamic connectivity regression model fails to detect statistically significant change points, even when visual inspection suggests connectivity states are changing.

Underlying Cause: This commonly occurs when the statistical test used for change-point detection does not properly account for the temporal dependence in fMRI time series data. Traditional tests designed for independent and identically distributed (IID) data may have low power with autocorrelated neuroimaging data [36].

Solutions:

- Implement Random Matrix Theory (RMT) Approach: Use the largest eigenvalues of covariance matrices calculated from regions of interest (ROIs) to detect change points. Calculate the covariance matrix for each time point using a sliding window approach, then compute the maximum eigenvalue for each matrix. Test for significant changes in these eigenvalues across time using RMT-based inference, which is specifically designed for high-dimensional time series data [36].

- Apply Fused Lasso Regression: Use fused lasso to detect the number and position of rapid connectivity changes by minimizing the residual sum of squares with L1 penalty on the differences between consecutive connectivity states. This method automatically identifies change points without pre-specifying their number [37].

- Validate with Surrogate Data: Generate surrogate time series that preserve individual properties of the original series but are otherwise uncoupled. Compare your change-point detection results against these surrogates to assess significance [19].

Implementation Steps for RMT Method:

- Partition voxels into mutually exclusive neuroanatomical ROIs

- For each subject, extract multivariate time series data from d ROIs across T time points

- Calculate sample covariance matrices using a sliding window approach

- Compute the largest eigenvalue for each covariance matrix across time

- Apply RMT-based inference to detect significant changes in eigenvalue sequences

- Use bootstrap validation to generate confidence intervals for detected change points [19] [36]

Issue 2: Low Reliability of Single-Subject Connectivity Measures

Problem: Your single-subject dynamic connectivity estimates show poor test-retest reliability across scanning sessions, making them unsuitable for clinical decision-making or tracking treatment response.

Underlying Cause: Low signal-to-noise ratio in fMRI data, head motion effects, physiological noise, and scanner instabilities can all contribute to unreliable connectivity estimates at the individual level [38] [39].

Solutions:

- Integrate Intra-Run Variability (IRV) Weighting: Calculate IRV by analyzing each task block separately within a run, then use this information to weight standard GLM activation maps. This approach significantly improves reliability by identifying the most constant and relevant neuronal activity [40].

- Implement GLMsingle Toolbox: Use this automated toolbox to improve single-trial response estimates through three key optimizations: deriving voxel-specific hemodynamic response functions (HRFs) from a library of candidates, incorporating noise regressors from unrelated voxels via cross-validation, and applying ridge regression with voxel-wise regularization to stabilize estimates for closely spaced trials [39].

- Apply Dice Coefficient and ICC Metrics: Quantify reliability using the Dice coefficient for spatial overlap of active regions and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for both location and relative scale of activity across sessions [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Subject Reliability Improvement Methods

| Method | Key Mechanism | Reported Improvement | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRV Weighting | Weighting based on block-by-block variability | Significant reliability improvement (p=0.007) [40] | Moderate |

| GLMsingle | Integrated HRF optimization, denoising, and regularization | Substantial improvement in test-retest reliability across visual cortex [39] | High |

| Custom HRF + Cross-validation | Voxel-specific HRF identification and noise modeling | Improved response estimates in auditory and visual domains [39] | High |

Issue 3: Poor Classification Accuracy Using Dynamic Connectivity Features

Problem: When using dynamic connectivity features from individual subjects for classification tasks (e.g., patient vs. control), you achieve unsatisfactory accuracy rates despite theoretically sound features.

Underlying Cause: This may result from using suboptimal change-point detection methods that fail to capture meaningful connectivity states, or from using static connectivity features that ignore important temporal dynamics [41] [37].

Solutions:

- Adopt Change-Point Based Dynamic Effective Connectivity: Use fused lasso to detect change points, then estimate effective connectivity networks within each state phase using conditional Granger causality. This approach has achieved 86.24% classification accuracy in Alzheimer's disease vs. healthy controls [37].

- Implement Machine Learning Connectivity Change Quantification: Use a binary classifier applied to random snapshots of connectivity within defined time intervals, with cross-validation performance serving as a continuous measure of connectivity change magnitude. This approach has achieved 90.3% ROC-AUC for epilepsy surgery outcome prediction [42].

- Apply Metabolic Connectivity-Based Classification: For PET data, determine connectivity patterns for different classes using Pearson's correlation between uptake values in atlas-based segmented brain regions, then classify individuals by congruence of their uptake pattern with fitted connectivity patterns [41].

Workflow for Machine Learning Approach:

- Represent network states using random snapshots of connectivity within defined time intervals

- Apply binary classifier to distinguish between two network states

- Use cross-validation generalization performance as a measure of connectivity change

- Iteratively add nodes to network until connectivity change magnitude decreases

- Compare resulting network with ground truth (e.g., surgical resection) [42]

Dynamic Connectivity Change-Point Detection Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What statistical validation framework is most appropriate for single-subject dynamic connectivity measures?

The V3 (Verification, Analytical Validation, and Clinical Validation) framework provides a comprehensive approach for validating digital measures, adapted for neuroimaging contexts [43] [44]:

- Verification: Ensure digital technologies accurately capture and store raw fMRI data, addressing sensor performance in variable environments [43]

- Analytical Validation: Assess precision and accuracy of algorithms that transform raw data into connectivity metrics, validating change-point detection methods against ground truth simulations [43]

- Clinical Validation: Confirm that dynamic connectivity measures accurately reflect biological states relevant to the specific context of use [43]

For single-subject analyses specifically, implement surrogate data analysis to assess whether dynamics of interacting nodes are significantly coupled, and use bootstrap techniques to generate confidence intervals for comparing individual estimates across experimental conditions [19].

Q2: How can I determine the optimal number and placement of change points in dynamic connectivity without overfitting?

The fused lasso regression approach automatically determines both the number and position of change points by minimizing the residual sum of squares with L1 penalty on differences between consecutive states [37]. This method:

- Does not require pre-specifying the number of change points

- Handles rapid connectivity changes effectively

- Has demonstrated better classification performance than sliding window techniques

- Is computationally efficient for individual subject analysis

Complement this with cross-validation using machine learning classifiers to quantify connectivity change magnitude between states, using generalization performance as an objective measure of change significance [42].

Q3: What are the key advantages of dynamic effective connectivity over static functional connectivity for single-subject classification?

Table 2: Static vs. Dynamic Connectivity Comparison

| Feature | Static Functional Connectivity | Dynamic Effective Connectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Information | Assumes stationarity throughout scan | Captures time-varying properties |

| Directionality | Undirected correlations | Directed, causal influences |

| Change Detection | Cannot identify state transitions | Identifies specific change points |

| Classification Performance | Lower accuracy in disease classification | 86.24% accuracy in AD classification [37] |

| Biological Interpretation | Limited to correlation | Closer to real brain mechanism [37] |

Q4: How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio for single-trial response estimation in condition-rich fMRI designs?

The GLMsingle toolbox integrates three evidence-based techniques [39]:

- Voxel-specific HRF identification: Iteratively fit GLMs using different HRFs from a library and select the best-fitting function for each voxel

- Cross-validated noise regressors: Derive noise regressors from voxels unrelated to the experiment using PCA, adding components until cross-validated variance explained is maximized

- Voxel-wise regularization: Apply fractional ridge regression with custom regularization parameters for each voxel to improve stability of estimates for closely spaced trials

This combined approach has demonstrated substantial improvements in test-retest reliability across visual cortex in multiple large-scale datasets [39].

Single-Subject Connectivity Validation Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Dynamic Connectivity Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| GLMsingle Toolbox | Improves single-trial fMRI response estimates through integrated optimizations | MATLAB/Python toolbox; integrates HRF fitting, GLMdenoise, and ridge regression [39] |

| Random Matrix Theory Framework | Detects change points in functional connectivity using eigenvalue dynamics | Implement maximum eigenvalue sequence analysis with RMT inference [36] |

| Fused Lasso Regression | Detects number and position of connectivity change points without pre-specification | Apply L1 penalty on differences between consecutive states to identify breakpoints [37] |

| Surrogate Data Analysis | Assesses significance of connectivity measures by comparing to null models | Generate time series with preserved individual properties but nullified couplings [19] |

| Bootstrap Validation | Generates confidence intervals for single-subject connectivity estimates | Resample with replacement to create empirical distribution of connectivity measures [19] |

| Machine Learning Classifier | Quantifies connectivity change magnitude between network states | Use cross-validation performance of binary classifier as continuous change measure [42] |

| V3 Validation Framework | Comprehensive framework for verifying and validating digital measures | Structured approach covering verification, analytical validation, and clinical validation [43] [44] |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary functional difference between O-information and pairwise functional connectivity? Pairwise functional connectivity networks only capture dyadic (two-variable) interactions. In contrast, the O-information quantifies the balance between higher-order synergistic and redundant interactions within a system of three or more variables. It can reveal complex synergistic subsystems that are entirely invisible to standard pairwise network analyses [45].

My O-information calculation returns a negative value. What does this mean for my system? A negative O-information value indicates that the system is synergy-dominated. This means that the joint observation of multiple variables provides more information about the system's state than what is available from any subset of them individually. This is often associated with complex, integrative computations [45].

What does a positive O-information value signify? A positive O-information value signifies a redundancy-dominated system. In this regime, information is shared or copied across many elements, making the state of one variable highly predictive of the states of others. This can promote robustness and functional stability [45].

How much imaging time is required for reliable single-subject connectivity estimates? Research shows that reliability improves proportionally to