Systematic Bias from Motion in Developmental Neuroimaging: Sources, Solutions, and Implications for Research Validity

Motion artifacts introduce systematic bias into developmental neuroimaging data, threatening the validity of brain-behavior associations, particularly in pediatric and clinical populations.

Systematic Bias from Motion in Developmental Neuroimaging: Sources, Solutions, and Implications for Research Validity

Abstract

Motion artifacts introduce systematic bias into developmental neuroimaging data, threatening the validity of brain-behavior associations, particularly in pediatric and clinical populations. This article synthesizes current evidence to explore the origins and consequences of this bias, evaluates methodological approaches for artifact correction and data quality control, provides strategies for optimizing acquisition and processing pipelines, and introduces frameworks for validating findings against motion-related confounds. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource aims to equip the field with practical knowledge to mitigate motion-induced bias, thereby enhancing the reliability of neurodevelopmental discoveries and their translation into clinical applications.

Unmasking the Problem: How Motion Creates Systematic Bias in Neurodevelopmental Data

In neurodevelopmental research, the prevailing assumption that larger sample sizes inherently mitigate noise represents a critical methodological pitfall. Motion artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) do not constitute random noise but instead introduce systematic bias that correlates powerfully with key variables of interest such as age, clinical status, and cognitive ability. This technical analysis demonstrates how motion artifacts persist and even amplify in large-scale studies, threatening the validity of developmental findings. Through examination of artifact mechanisms, empirical evidence from major cohorts, and analysis of mitigation strategies, we establish that motion-related variance behaves as structured noise that conventional averaging cannot eliminate. The implications demand a fundamental shift in approach for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals utilizing neuroimaging biomarkers.

Motion artifacts have emerged as a preeminent challenge for developmental neuroimaging, fundamentally distinct from random noise due to their structured pattern and non-random distribution across populations [1]. The critical insight revolutionizing the field is that in-scanner motion frequently correlates with central variables of interest—including age, clinical status, cognitive ability, and symptom severity—thereby introducing systematic bias rather than random error [1] [2]. This confounding relationship creates a methodological perfect storm where motion artifacts masquerade as neural effects, potentially invalidating conclusions from even the largest-scale studies.

The problem is particularly acute in developmental neuroscience and psychiatric drug development, where participant populations (children, older adults, clinical cohorts) systematically exhibit greater motion than healthy young adult controls [2]. As sample sizes expand to thousands of participants in initiatives like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, the assumption that motion artifacts would "average out" has proven dangerously incorrect [3]. Contrary to this expectation, motion introduces directional biases that persist and potentially amplify in large datasets, creating spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks [1] [3].

Empirical Evidence: Motion Artifacts in Large-Scale Studies

Evidence from Major Neuroimaging Cohorts

Recent findings from the ABCD Study challenge the foundational assumption that larger sample sizes counteract noisy images. A manual quality assessment of 10,295 structural MRI scans revealed that 55% were of suboptimal quality, with 2% deemed unusable [3]. Crucially, incorporating these scans introduced systematic bias rather than random error: lower-quality scans consistently underestimated cortical thickness and overestimated cortical surface area [3].

In one analysis, when only the 4,600 highest-quality scans were included, significant group differences in cortical volume for children with aggressive behaviors appeared in three brain regions [3]. When moderate-quality scans were added, this number jumped to 21 regions, and when all scans were pooled, 43 regions showed significant differences [3]. This inflation of effect sizes with decreasing data quality demonstrates how motion artifacts create spurious findings that larger samples amplify rather than mitigate.

Motion as a Confound in Developmental Trajectories

The relationship between motion and age creates particularly problematic confounding in developmental research. Motion follows a U-shaped trajectory across the lifespan, with high motion in young children decreasing to low values in late teens through the 30s, followed by a gradual rise in later decades [2]. This pattern directly conflates with developmental changes in brain structure and function.

Table 1: Age-Related Motion Patterns in Neurodevelopment

| Age Group | Mean Framewise Displacement (FD) | Developmental Period | Impact on Connectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Childhood | ~0.50 mm [4] | Rapid synaptic pruning | Inflated short-distance connections [5] |

| Adolescence | ~0.09 mm [4] | Network specialization | Diminished long-distance connections [5] |

| Adulthood | ~0.05 mm [4] | Network stability | More accurate connectivity patterns [5] |

Longitudinal studies confirm that head motion decreases significantly as children age, with one study of children ages 9-14 showing a significant age effect on framewise displacement during both diffusion (p < .001) and resting-state functional MRI (p < .001) [4]. This motion-age relationship systematically biases estimates of connectivity change during development, particularly inflating distance-dependent effects [5].

Mechanisms: How Motion Artifacts Create Systematic Bias

Physics of Motion Artifacts in MRI

The manifestation of motion artifacts in MRI stems from fundamental physical principles of image acquisition. Unlike photography, MRI data collection occurs in Fourier space (k-space), where each sample contains global information about the image [6]. Motion during acquisition creates inconsistencies between different portions of k-space data, violating the core assumption of stationary objects during reconstruction [6] [7].

The specific appearance of motion artifacts depends on both the nature of movement and the k-space sampling strategy:

- Cartesian sampling: Produces ghosting artifacts in the phase-encoding direction [6] [7]

- Radial sampling: Results primarily in image blurring [6] [7]

- Periodic motion: Creates coherent ghosting with replicas corresponding to motion frequency [6]

- Random motion: Generates incoherent ghosting appearing as stripes [6]

These artifacts produce spatially structured noise that correlates with subject factors rather than distributing randomly across populations.

Impact on Functional Connectivity Measures

In functional connectivity MRI (fc-MRI), motion artifacts introduce distance-dependent biases that systematically alter network properties. Higher motion causes spurious decreases in long-distance correlations and increases in short-distance connectivity [1] [4]. This pattern directly mimics—and potentially creates—the appearance of developmental changes, where brain maturation is characterized by strengthening long-range connections and weakening short-range connections [5].

The temporal properties of motion artifacts further complicate their removal. Motion produces both immediate signal drops following movement events and longer-duration artifacts (up to 8-10 seconds) that may result from motion-related changes in CO₂ from yawning or deep breathing [1]. These effects introduce nonlinear relationships that rigid-body correction models cannot fully capture [1].

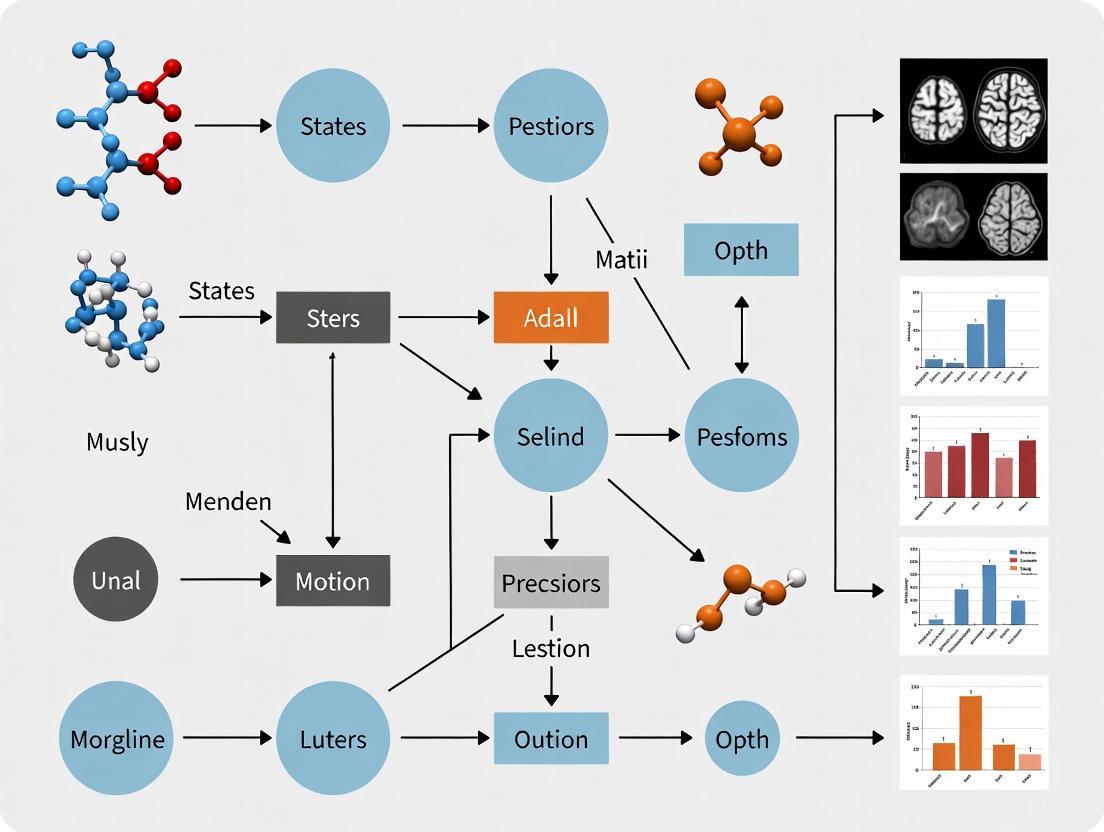

Diagram Title: Motion Artifact Propagation in MRI

Population-Specific Vulnerabilities and Biases

Clinical Populations and Motion as Behavioral Phenotype

The non-random distribution of motion across clinical populations creates systematic exclusion biases that threaten the generalizability of neuroimaging findings. Patients with psychotic disorders exhibit significantly more head movement than healthy controls due to factors including psychomotor agitation, anxiety, paranoia, medication side effects, and difficulty following instructions [8]. This elevated motion may represent a behavioral phenotype rather than mere data quality issue, as patients who struggle to remain still may constitute a distinct neurobiological subtype with more severe symptoms [8].

In ADHD populations, children consistently display greater framewise displacement than controls across ages 9-14 [4]. Crucially, even children in remission from ADHD showed continued elevation in head motion compared to controls, suggesting that motion may represent a persistent trait rather than state marker [4]. This pattern indicates that motion itself may be part of the ADHD phenotype, with important implications for interpreting neuroimaging findings in this population.

Table 2: Motion Patterns Across Clinical Populations

| Population | Motion Level | Primary Contributors | Impact on Data Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosis | Significantly elevated [8] | Psychomotor agitation, disorganization, anxiety [8] | Exclusion of most severe cases creates spectrum bias [8] |

| ADHD | Consistently elevated [4] | Innate hyperactivity, impulsivity [4] | Motion as intrinsic trait rather than artifact [4] |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Elevated [2] | Developmental immaturity, symptom-related restlessness [2] | Altered developmental trajectories [2] |

| Childhood Samples | Age-dependent [2] [4] | Developmental capacity for stillness [2] | Confounding of age and motion effects [5] |

The Missing Not at Random (MNAR) Problem

The practice of excluding high-motion scans introduces a fundamental statistical problem: Missing Not at Random (MNAR) data [8]. When participants with the most severe clinical presentations produce unusable scans due to motion, the resulting dataset systematically underrepresents the most severe end of the illness spectrum. This exclusion biases effect size estimates and limits generalizability to the original target population [8].

For example, if patients with severe, disorganized schizophrenia cannot tolerate the scanner environment, their exclusion will bias hippocampal volume estimates toward larger values, potentially underestimating the true effect size of the disorder on brain structure [8]. This MNAR problem violates the assumptions of most inferential statistical approaches, potentially yielding biased parameter estimates and invalid inferences [8].

Mitigation Strategies and Methodological Recommendations

Acquisition Protocols and Experimental Design

Effective motion mitigation begins during study design and data acquisition. Strategic approaches include:

- Split-session designs: Distributing fMRI acquisition across multiple same-day sessions reduces head motion in children, while inside-scanner breaks benefit adults [9]

- Mock scanner training: Familiarization sessions improve participant comfort and compliance [4] [9]

- Participant preparation: Clear instructions, comfortable positioning, and reinforcement strategies minimize initial motion [8]

- Sequence optimization: Radial k-space sampling produces more tolerable blurring artifacts compared to Cartesian ghosting [6] [7]

These approaches address motion prevention rather than correction, reducing the problem at its source.

Processing and Analysis Techniques

When motion occurs despite prevention efforts, multiple processing strategies can mitigate its impact:

- Robust confound regression: Expanded nuisance regressors including motion parameters and their temporal derivatives [1] [5]

- Motion scrubbing: Identifying and removing high-motion volumes using framewise displacement (FD > 0.5mm) or DVARS thresholds [1] [8]

- ICA-based denoising: Algorithms like ICA-AROMA automatically identify and remove motion-related components [8]

- Volume-based correction: Realigning each volume to a reference using tools like FSL's MCFLIRT or AFNI's 3dvolreg [8]

Critically, each method has limitations. Scrubbing can introduce MNAR biases, ICA may remove neural signals along with noise, and regression assumes linear relationships that may not fully capture motion effects [8].

Diagram Title: Motion Mitigation Pipeline

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Management

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement (FD), DVARS [1] [8] | Quantifies volume-to-volume movement for scrubbing and QC | Varies across implementations; TR-dependent [1] |

| Realignment Tools | FSL's MCFLIRT, AFNI's 3dvolreg [8] | Corrects for between-volume motion via rigid registration | Cannot correct intra-volume motion [8] |

| ICA Denoising | ICA-AROMA, FSL's FIX [8] | Identifies and removes motion-related components | May remove neural signals; computational intensity [8] |

| Quality Metrics | Surface Hole Number (SHN) [3] | Automated quality assessment approximating manual rating | Does not eliminate error as effectively as manual rating [3] |

| Prospective Correction | PACE, Volumetric Navigators [8] | Real-time motion tracking and slice position updating | Hardware limitations; not widely available [8] |

Motion artifacts in MRI represent a fundamental challenge that larger samples amplify rather than mitigate. The systematic nature of motion-induced bias, its correlation with key demographic and clinical variables, and its structured impact on connectivity measures collectively undermine the assumption that motion averages out in large datasets. For developmental researchers and drug development professionals, this necessitates a paradigm shift from considering motion as a nuisance variable to recognizing it as a potentially catastrophic confound that threatens inference validity.

Future directions must include: (1) development of universal motion metrics standardized across acquisition parameters; (2) integration of prospective correction techniques into clinical scanners; (3) adoption of standardized reporting of motion exclusion criteria and quality control procedures; and (4) implementation of sensitivity analyses demonstrating result robustness across quality thresholds. Most critically, the field must abandon the dangerous illusion that larger samples automatically solve the motion problem and instead confront motion artifacts as structured variance that demands sophisticated methodological attention throughout the research pipeline.

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) has become a cornerstone of clinical neuroscience research, offering unparalleled insights into brain morphometry. However, the fidelity of this powerful tool is critically threatened by a pervasive source of systematic bias: in-scanner motion. Even minor, visually imperceptible movement during acquisition can introduce structured noise that systematically distorts key morphometric measures. This technical guide details the specific nature of this bias—a consistent underestimation of cortical thickness and overestimation of cortical surface area—within the critical context of developmental neuroimaging research. Understanding and mitigating this bias is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to identify true neurobiological markers in developmental disorders and treatment effects.

The challenge is particularly acute in studies of children, adolescents, and individuals with neurodevelopmental or movement disorders, who tend to move more during scanning [10] [11]. As large-scale, population-level studies like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study become more common, the field is confronting a sobering realization: larger sample sizes alone do not overcome this systematic bias; they can, in fact, amplify it, leading to both false-positive and false-negative findings [3] [12]. This guide synthesizes recent evidence quantifying this impact, outlines methodologies for its detection and correction, and provides a practical toolkit for enhancing the rigor of structural neuroimaging.

Quantifying the Systematic Bias

The impact of motion on sMRI is not random error but a directionally consistent bias that mimics specific neuroanatomical patterns. Evidence from large-scale studies demonstrates that this bias systematically alters measurements in ways that can be misinterpreted as genuine neurodevelopmental effects.

Evidence from Major Studies

Table 1: Key Studies Quantifying Motion-Related Bias in sMRI

| Study | Sample | Key Finding on Cortical Thickness | Key Finding on Cortical Surface Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCD Study (Roffman et al.) [3] | >10,000 scans; children aged 9-10 | Lower-quality scans consistently underestimate cortical thickness. | Lower-quality scans consistently overestimate cortical surface area. |

| ABCD Preprint (Roffman et al.) [12] | 11,263 T1 scans from ABCD Study | Linear association between poorer quality and reduced thickness across much of the cortex. | Increased surface area in lateral/superior regions; mixed effects elsewhere. |

| Healthy Brain Network [11] | 388 participants; ages 5-21 | Image quality significantly impacts cortical thickness in ~23.4% of brain areas investigated. | Image quality significantly impacts cortical surface area in ~23.4% of brain areas investigated. |

| PMC Study [13] | 127 children, adolescents, and young adults | Trend-level decrease in cortical thickness with greater motion. | N/A (Focused on cortical volume and curvature) |

Incorporating lower-quality scans dramatically inflates effect sizes in group analyses. One analysis of the ABCD data found that when comparing cortical volume in children with versus without aggressive behaviors, the number of significant brain regions jumped from 3 to 43 as lower-quality scans were added to the analysis [3]. This demonstrates how motion bias can create the illusion of widespread, statistically significant findings.

Effect Sizes and Anatomical Specificity

The bias introduced by motion is not uniform across the brain and can be substantial in magnitude.

Table 2: Effect Sizes of Motion on Structural Measures

| Metric | Direction of Bias | Effect Size (Cohen's d) | Anatomical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Thickness | Systematic Underestimation | 0.14 – 2.84 [12] | Effects are anatomically heterogeneous [13]. |

| Cortical Surface Area | Systematic Overestimation | 0.14 – 2.84 [12] | Overestimation is prominent in lateral/superior regions [12]. |

| Cortical Gray Matter Volume | Decrease | Significant relationships found [13] | A product of thickness and area; bias direction can vary. |

| Cortical Curvature | Increase | Significant relationships found [13] | Increased mean curvature with greater motion. |

The biomechanical reasons for this specific directional bias are rooted in how motion corrupts the image data. Motion causes blurring at the tissue boundaries, which complicates the accurate identification of the gray matter/white matter border (impacting thickness) and the pial surface (impacting surface area) [13] [11]. The result is an output that can appear biologically plausible, making the bias particularly insidious.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Motion Bias

Rigorous assessment of motion bias relies on a combination of experimental design and quality control methodologies. The following protocols are considered best practice in the field.

Protocol 1: Using fMRI as a Proxy for sMRI Motion

Objective: To obtain a continuous, quantitative estimate of subject motion during a scanning session to correlate with structural MRI measures, even in the absence of visible sMRI artifacts [13].

Workflow:

- Image Acquisition: Acquire a T1-weighted structural scan followed by two (or more) resting-state fMRI scans during the same session.

- Motion Quantification (fMRI): Process the fMRI data through a standard realignment algorithm (e.g., in SPM or FSL) to generate framewise displacement (FD) timeseries for each subject.

- Summary Metric: Calculate the mean FD across the entire fMRI scan. This serves as a reliable, continuous proxy for the subject's tendency to move during the scanning session, including during the prior structural scan [13] [11].

- Morphological Analysis: Process the T1-weighted structural scans using automated pipelines (e.g., FreeSurfer, CIVET) to extract cortical thickness, surface area, and volume.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform whole-brain or region-of-interest regression analyses, modeling the morphometric measures (e.g., cortical thickness) as a function of the mean FD metric, while controlling for covariates like age, sex, and site.

Protocol 2: Manual Quality Control (MQC) and Group Comparison

Objective: To categorize scans based on visual quality and quantify the morphometric differences between quality groups in a large dataset [3] [12].

Workflow:

- Visual Inspection: A trained rater, blinded to subject information, views each T1 volume and assigns a quality rating based on a predefined scale (e.g., 1=minimal edits needed, 2=moderate edits, 3=substantial edits, 4=unusable) [12].

- Group Formation: Form groups based on MQC ratings. For example, a "High-Quality" group (rating 1) and a "Lower-Quality" group (ratings 2-4).

- Automated Processing: Process all scans through an automated pipeline like FreeSurfer to obtain morphometric measures.

- Group Analysis: Compare morphometric outputs (cortical thickness, surface area) between the High-Quality and Lower-Quality groups to quantify the systematic bias introduced by motion.

Protocol 3: Retrospective Deep Learning-Based Motion Correction

Objective: To correct for motion artifacts in structural MRI images after acquisition using a convolutional neural network (CNN) [14].

Workflow:

- Model Training:

- Gather a dataset of motion-free, high-quality T1-weighted images.

- Artificially corrupt these clean images by simulating motion artifacts in the Fourier domain (K-space) to create paired training data (corrupted vs. clean).

- Train a 3D CNN to learn the mapping from the motion-corrupted image to the clean image.

- Application and Validation:

- Apply the trained CNN to real motion-affected scans to generate corrected images.

- Validate the correction using image quality metrics like Peak Signal-to-Noise-Ratio (PSNR) and by demonstrating improved cortical surface reconstructions [14].

- Statistically compare morphometric measures (e.g., cortical thickness) derived from original and corrected images to show a reduction in motion-related bias.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Quantifying and Correcting Motion Bias. This diagram outlines the three primary methodological approaches for assessing the impact of motion on cortical measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully navigating the challenge of motion bias requires a suite of methodological tools and quality control metrics.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Motion Bias Research

| Tool/Solution | Function | Relevance to Motion Bias |

|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer [10] | Automated surface-based and volume-based stream processing of T1 MRI. | The primary source of morphometric measures (thickness, area). Its outputs are the target of the bias. |

| CIVET Pipeline [13] | Automated MRI analysis pipeline for cortical segmentation and thickness. | Provides an alternative processing platform to validate that motion biases are not pipeline-specific. |

| Surface Hole Number (SHN) [3] [12] | An automated QC metric estimating imperfections in cortical reconstruction. | A robust, automated proxy for manual QC. Effectively differentiates lower-quality scans to "stress-test" findings. |

| CAT12 Toolbox [11] | Computational Anatomy Toolbox for SPM; provides image quality metrics. | Offers an independent, automated aggregate "grade" for a structural scan, correlating with human rating and morphometry. |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) [13] [11] | A quantitative measure of head motion derived from fMRI realignment parameters. | Serves as a continuous assay for a subject's motion propensity during the scanning session. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [14] | Deep learning model for retrospective motion artifact correction. | Learns to map motion-corrupted T1 images to their clean counterparts, improving downstream surface reconstruction. |

The systematic underestimation of cortical thickness and overestimation of surface area due to in-scanner motion is a critical, empirically validated source of bias in developmental neuroimaging. This bias is systematic, not random, leading to effect size inflation and potentially spurious findings that can misdirect research and drug development efforts. Mitigating this threat requires a proactive, multi-pronged strategy: implementing rigorous manual or automated quality control (with metrics like Surface Hole Number), incorporating motion as a covariate in statistical models, and exploring advanced retrospective correction techniques. For the field to produce reliable and replicable results, especially in large-scale studies of developmental populations, acknowledging and correcting for this systematic bias must become a non-negotiable standard in the analysis pipeline.

The pursuit of objective biomarkers in developmental neuroscience is fundamentally challenged by systematic biases, with motion artifacts representing a particularly pervasive source of error. While motion affects neuroimaging data universally, its impact disproportionately affects already vulnerable populations, including children and psychiatric patients, thereby distorting our understanding of brain development and pathology. This disproportionality arises not from biological inevitability but from a complex interplay of technical limitations, methodological oversights, and socio-structural barriers that converge upon these groups. Within the context of a broader thesis on systematic bias from motion in developmental neuroimaging, this technical guide examines how pre-existing vulnerabilities are amplified by research methodologies, creating a feedback loop that further marginalizes these populations. The consequences extend beyond scientific inconvenience to affect the validity, reliability, and generalizability of neurodevelopmental findings, ultimately perpetuating inequities in both knowledge generation and clinical translation [15] [16].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms through which motion-related biases disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, supported by quantitative data and experimental evidence. It further presents detailed methodologies for bias mitigation and a forward-looking framework for developing more equitable neuroimaging research practices targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of neurodevelopment and psychiatric disorders.

The Disproportionate Impact of Motion on Vulnerable Populations

Quantitative Evidence of Disparities

Table 1: Documented Disparities in Neuroimaging Study Populations

| Domain of Disparity | Reported Finding | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Reporting | Only 10% of neuroimaging studies report race; 4% report ethnicity [17]. | Systematic Review of 408 MRI Studies (2010-2020) |

| Sample Representation | Predominantly White participants (86%) in a pre-clinical Alzheimer's trial of ~6,000 individuals [17]. | Raman et al. |

| Workforce Diversity | Lack of diversity in neuroscience workforce leads to unacknowledged bias in scientific agendas [16]. | Firat et al. |

| Device Exclusion | EEG, fNIRS, skin conductance, and eye-tracking tools systematically exclude participants based on phenotypic differences (e.g., hair structure, skin pigmentation) [15]. | Webb et al. |

Mechanistic Pathways of Disproportionate Impact

The disproportionate effect of motion on children and psychiatric patients operates through several interconnected pathways, creating a bias propagation pipeline [18].

Physiological and Developmental Factors

Children, particularly young children and those with neurodevelopmental or psychiatric conditions, exhibit age-typical and condition-related motor restlessness. The capacity for volitional motion suppression during extended scanning sessions is a developmental achievement that hinges on prefrontal cortex maturation, which continues into early adulthood. Psychiatric populations, including those with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Tourette's Syndrome, or anxiety disorders, may experience involuntary movements, tics, or heightened psychomotor agitation that directly conflict with data acquisition requirements. Furthermore, the MRI environment itself—a loud, confined, and novel space—can induce anxiety and stress, particularly in children with a history of trauma or those with conditions like autism spectrum disorder. This stress can potentiate threat hypervigilance and increase motion, thereby confounding neural activity patterns related to the experimental task with those related to stress and anxiety [16].

Socio-Structural and Economic Factors

Vulnerable populations often face logistical and economic barriers that compound their physiological predisposition to motion-related artifacts. Longitudinal studies, crucial for developmental neuroscience, show higher attrition rates among marginalized groups due to time-intensive protocols, transportation difficulties, and greater family responsibilities [15]. For example, the Generation R Study in the Netherlands became less diverse in terms of ethnicity and educational level with each wave despite concerted retention efforts [15]. This attrition bias means that studies progressing over time may systematically lose the very participants who are most susceptible to motion, thereby producing increasingly non-representative data. Furthermore, individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may have less access to financial and digital resources, which can prevent initial participation and familiarity with research settings, potentially increasing anxiety and motion during their first and only scan session [15] [19].

Technological and Methodological Exclusion

A critical yet often overlooked pathway is the inherent design bias in neuroscientific tools. Electrophysiological devices like EEG were often not designed to handle human phenotypic variability. Participants with coarse, curly, or thick hair types (e.g., Afro-textured hair) or protective styles (e.g., braids, dreadlocks) have been systematically excluded from EEG studies due to difficulties in achieving adequate electrode-scalp contact and insufficient signal quality [15] [16]. This exclusion is not merely a recruitment failure but a fundamental bias in technological design. Similarly, the physical design of MRI head coils can restrict natural hairstyles, and sew-in hair extensions with metal tracks can prevent entry into the scanner bore altogether [16]. This technological exclusion means that entire groups are erased from datasets from the outset, and those who do participate may do so under suboptimal or stressful conditions that increase motion.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating and Mitigating Bias

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Framework

The Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) framework actively involves the population of interest in the research process to counter biases.

- Objective: To establish equitable researcher-community partnerships that enhance recruitment, retention, and protocol appropriateness for underrepresented groups, thereby reducing situational factors that lead to increased motion.

- Procedure:

- Establish a Community Advisory Board (CAB): Recruit a diverse group of community members, including parents and youth from the target population, to collaborate throughout the research process [16].

- Conduct Positionality Mapping: Researchers explicitly document their own social positions (e.g., race, gender, institutional affiliation) and reflect on how these positions may influence research questions, hypothesis formation, and interactions with participants [16].

- Co-Design Study Protocols: The CAB provides feedback on all aspects of the study, including the consent process, assessment tools, and the MRI experience. This can involve creating child-friendly scanner mock-up training sessions to reduce anxiety and practicing remaining still in a simulated environment [16].

- Iterative Review and Dissemination: The CAB reviews findings and helps disseminate results back to the community in accessible formats.

- Rationale: This approach builds trust, improves cultural competence, and directly addresses logistical and emotional barriers that contribute to motion in scanner environments, leading to more robust and generalizable data collection [16].

Quantitative Bias Analysis (QBA) for Motion Artifact

Quantitative Bias Analysis (QBA) provides a set of methodological techniques to quantitatively estimate the potential magnitude and direction of systematic error, such as selection bias introduced by motion-related exclusion.

- Objective: To move beyond qualitative discussion of motion as a limitation and instead model how motion-induced selection bias might have influenced the observed study results.

- Procedure (Probabilistic Bias Analysis):

- Define the Bias Structure: Using a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), depict the relationships between motion, participant vulnerability factors, inclusion in the final analysis, and the outcome of interest [20] [21].

- Specify Bias Parameters: Estimate the probability of exclusion from the final analysis due to motion for different groups (e.g., children with ADHD vs. typically developing controls). These parameters can be informed by internal study data or external validation studies [22] [20].

- Model the Uncertainty: Assign probability distributions (e.g., beta distributions) to the bias parameters to account for uncertainty in their values [20].

- Perform Probabilistic Adjustment: Run a large number of Monte Carlo simulations (e.g., 10,000). In each simulation, draw a value for each bias parameter from its specified distribution and use these values to probabilistically correct the original data.

- Summarize Results: The output is a distribution of bias-adjusted estimates. Report the median adjusted estimate and a 95% simulation interval, which quantifies the uncertainty in the results after accounting for the systematic bias [20].

- Rationale: QBA transforms the discussion of motion bias from a speculative limitation into a quantifiable uncertainty, providing a more realistic interpretation of study findings and highlighting the potential for biased inference [22] [20] [21].

Protocol for Mitigating Motion in Pediatric & Psychiatric Populations

A practical, multi-faceted protocol can proactively reduce motion artifacts during data acquisition.

- Objective: To minimize the occurrence and impact of head motion during MRI scans in challenging populations.

- Procedure:

- Pre-Scan Preparation:

- Scanner Mock-Up Training: Conduct extensive behavioral training using a mock scanner. Have participants practice the scan protocol while listening to recorded scanner noises. Provide real-time feedback on head motion [16].

- Social Story Videos: Create visual guides featuring participants from diverse backgrounds successfully completing a scan to reduce anxiety and set expectations.

- In-Scan Strategies:

- Positive Reinforcement: Implement a reward system (e.g., points, small prizes) for successful still periods. Use a real-time motion-tracking system with a display that provides visual feedback to the participant (e.g., a "game" where staying still keeps a character on screen).

- Comfort Optimization: Use comfortable, pediatric-sized padding and cushions to minimize involuntary motion. Ensure the room is at a comfortable temperature.

- Shortened Paradigms: Break long scanning sessions into shorter, manageable blocks with breaks in between.

- Post-Scan Analysis:

- Proactive Data Exclusion: Apply stringent, pre-registered motion-correction algorithms (e.g., ICA-AROMA, SCRUBBING).

- Motion as a Covariate: In statistical models, include quantitative motion estimates as a nuisance variable to control for its residual effects.

- Pre-Scan Preparation:

- Rationale: A comprehensive approach that addresses anxiety, provides motivation, and maximizes physical comfort can significantly increase the yield of usable data from vulnerable participants, reducing the need for exclusion and mitigating selection bias [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Equitable and Rigorous Neuroimaging Research

| Tool or Resource | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) | Advises on all research stages, improves cultural competence, builds trust, and enhances participant comfort to reduce motion-inducing anxiety. | Composed of community members, parents, and youth; used for protocol co-design and feedback on dissemination [16]. |

| Quantitative Bias Analysis (QBA) | Quantifies the impact of systematic errors (e.g., selection bias from motion-related exclusion) on study results, moving beyond speculative discussion. | Methods range from simple to probabilistic analysis; requires specification of bias parameters [22] [20] [21]. |

| Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) | A visual tool to identify and communicate potential sources of confounding and selection bias in the study design. | Used to map relationships between vulnerability, motion, exclusion, and outcomes, clarifying the bias structure for QBA [20]. |

| Scanner Mock-Up System | A simulated MRI scanner environment for behavioral training; acclimates participants to the scanning experience, reducing anxiety and motion. | Includes a mock scanner bore and playback of scanner sounds; allows for practice with feedback [16]. |

| Real-Time Motion Tracking | Software that provides immediate feedback on participant head motion during the scan, allowing for correction and coaching. | Can be integrated with visual feedback games for children to incentivize staying still [16]. |

| Openly Shared Bias Analysis Code | Pre-written scripts (e.g., in R, Python, or SAS) to facilitate the implementation of QBA methods, lowering the barrier to adoption. | Resources are available from organizations like the International Society for Environmental Epidemiology (ISEE) QBA SIG [21]. |

The disproportionate impact of motion artifacts on children and psychiatric patients in developmental neuroimaging is not a mere technical obstacle but a profound methodological and ethical challenge that threatens the validity of the field's findings. As this guide has detailed, the issue is rooted in a self-reinforcing cycle where physiological predispositions, structural barriers, and technologically exclusionary designs converge to systematically marginalize vulnerable populations. This ultimately results in biased datasets, ungeneralizable models, and clinical tools that may perform poorly for the very groups they are intended to serve.

Breaking this cycle requires a fundamental shift from passive observation to active intervention. The experimental protocols and tools outlined—ranging from Community-Based Participatory Research and rigorous Quantitative Bias Analysis to practical motion-mitigation strategies—provide a roadmap for this transition. The future of equitable developmental neuroscience depends on the widespread adoption of such practices. This includes diversifying research teams, mandating demographic reporting, and investing in the development of inclusive technologies that accommodate natural human variation [15] [17] [16]. By reconceptualizing motion not as a nuisance variable but as a manifestation of systemic bias, researchers can build a more rigorous, reproducible, and just science of brain development.

In clinical research, particularly in developmental neuroimaging, head motion during data acquisition has emerged as a critical source of systematic bias rather than mere random noise. This motion systematically excludes specific patient phenotypes from study populations, creating a Missing Not at Random (MNAR) problem that fundamentally compromises the validity and generalizability of research findings. In neuroimaging studies of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, patients exhibit significantly more head movement during scanning compared to healthy controls [8]. This increased motion is not random but is intrinsically linked to core symptoms of these conditions, including psychomotor agitation, disorganized behavior, anxiety, or medication side effects such as akathisia [8]. When researchers exclude data from participants with excessive motion—a standard quality control practice—they systematically remove the most severely affected individuals from their samples. This introduces substantial bias by shifting the study population toward the less severe end of the clinical spectrum, potentially obscuring crucial brain-behavior relationships and producing misleading conclusions about the neurobiological underpinnings of psychiatric illness.

The MNAR Problem: Theoretical Framework and Clinical Implications

Defining Missing Not at Random (MNAR) in Clinical Contexts

In statistical terms, MNAR refers to situations where the probability of data being missing is directly related to the actual values of the missing data themselves. In the context of clinical neuroimaging, this occurs because patients with more severe symptoms are more likely to produce unusable scans due to motion artifacts [8]. This creates a fundamental violation of the assumptions underlying most standard statistical approaches, including t-tests and ANOVA, which assume that any missing data are ignorable (missing due to random reasons) [8]. When data are MNAR, these analyses yield biased parameter estimates and invalid inferences in hypothesis testing, potentially leading to false conclusions about disease mechanisms and treatment effects.

Evidence from electronic monitoring studies in bipolar disorder further confirms the MNAR phenomenon in clinical research. One study found that missing data were lowest for participants in depressive episodes, intermediate for those with subsyndromal symptoms, and highest for euthymic participants [23]. Furthermore, when participants' clinical status changed during the study (e.g., transitioning from euthymia to depression), missing data for self-rating scales increased significantly [23]. This pattern demonstrates that missingness is directly tied to clinical state rather than occurring randomly.

Motion as a Behavioral Phenotype in Psychosis Spectrum Disorders

Rather than being mere noise that corrupts data, head movements during scanning may carry important information about the study population. Patients who struggle to remain still for an MRI could represent a distinct behavioral or neurobiological subtype of psychosis [8]. For instance, marked restlessness or inability to comply with scanner instructions may be a proxy for high levels of psychomotor agitation, anxiety, or disorganization [8]. Similarly, severe paranoia might make it challenging for patients to tolerate the confined, noisy scanner environment, leading to increased movements. These symptoms typically indicate a more severe or acute presentation, meaning that excluding scans from these subjects necessarily biases the study population toward milder cases and limits the generalizability of findings to the full clinical population [8].

Table 1: Clinical Correlates of In-Scanner Motion in Psychosis Spectrum Disorders

| Clinical Feature | Relationship to Motion | Impact on Data Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Psychomotor Agitation | Directly increases movement | High exclusion risk for agitated patients |

| Disorganized Behavior | Reduces ability to follow instructions | Systematic exclusion of disorganized subtype |

| Paranoia | Increases discomfort in scanner environment | Exclusion of patients with reality distortion |

| Medication Side Effects | Akathisia can cause restlessness | Exclusion of patients with treatment complications |

| Poor Insight | Reduces compliance with instructions | Exclusion of patients lacking illness awareness |

Quantitative Evidence of Motion-Induced Bias in Large-Scale Studies

Systematic Bias in Major Neuroimaging Datasets

The assumption that larger sample sizes automatically counteract the effects of noisy data has been challenged by recent findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, which revealed that poor image quality introduces systematic bias into large-scale neuroimaging analyses [3]. When researchers manually assessed the quality of over 10,000 sMRI scans from the ABCD Study, they found more than half (55%) were of suboptimal quality, even after standard automated quality-control steps [3]. Critically, incorporating these lower-quality scans introduced systematic bias rather than random noise.

The study demonstrated that lower-quality scans consistently underestimate cortical thickness and overestimate cortical surface area, with these errors growing as scan quality decreases [3]. In one analysis, when examining cortical volume differences between children with or without aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors, the number of significant brain regions inflated dramatically as lower-quality scans were added: from 3 regions in the highest-quality scans (n=4,600) to 21 regions when moderate-quality scans were included, and to 43 regions when all scans were pooled [3]. This demonstrates how motion artifacts can create false positive findings or inflate effect sizes in large datasets.

Table 2: Impact of Scan Quality on Statistical Results in the ABCD Study

| Sample Composition | Number of Significant Brain Regions | Effect Size Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Highest-quality scans only (n=4,600) | 3 regions | Baseline effect sizes |

| Including moderate-quality scans | 21 regions | Effect sizes more than doubled in some regions |

| All scans pooled | 43 regions | Further inflation of effect sizes |

Statistical Consequences of Motion Exclusion

The exclusion of high-motion scans has direct statistical consequences for research findings. In a hypothetical example described in the literature, if the full schizophrenia population has smaller hippocampal volumes than healthy controls by a specific value, excluding high-motion scans (which disproportionately come from patients with more severe illness) would bias the estimated average hippocampal volume toward a larger value [8]. This leads to an underestimation of the true effect in the study and potentially masks genuine neurobiological differences associated with the disorder.

The problem is particularly pronounced in studies comparing clinical populations to healthy controls, as the exclusion rates are typically asymmetrical between groups. One analysis found that controlling for motion artifacts reduced the number of significant findings in brain-wide association studies by over 50%, with the largest reductions occurring in brain regions previously associated with motion [3].

Methodological Approaches: From Motion Correction to Phenotyping

Motion Mitigation Strategies in MRI Research

Several strategies have been developed to manage head motion during MRI scans, ranging from preventive approaches to technical corrections:

- Preventive Methods: Providing clear instructions during patient preparation, using physical restraints (foam padding), practice mock scan sessions, reward incentives, and displaying media content during scan breaks [8].

- Prospective Motion Correction: Real-time tracking and correction during scanning by updating slice acquisition coordinates based on detected movement [8].

- Real-time Monitoring: Systems that monitor head motion frame-by-frame and can pause scanning or extend acquisition until sufficient low-motion data are collected [8].

- Retrospective Correction: Algorithms applied after data acquisition, including volume realignment tools like FSL's MCFLIRT and AFNI's 3dvolreg [8].

Despite these innovations, real-time motion correction tools are not yet in widespread use due to complexity and hardware limitations, meaning most studies still rely heavily on retrospective correction methods [8].

Analytical Approaches for Motion-Affected Data

For data already affected by motion, researchers have developed multiple analytical strategies to mitigate bias:

- Motion Scrubbing: Removing volumes with motion beyond a specific threshold (e.g., framewise displacement >0.5mm) from fMRI time series [8]. When too many volumes are scrubbed (typically >20%), the entire participant may be excluded.

- Covariate Adjustment: Including motion parameters (mean framewise displacement, number of removed frames) as covariates in group-level statistical models [8].

- Denoising Techniques: Using Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to identify noise components associated with motion and regress them out of the data without discarding entire volumes [8]. Tools include FSL's ICA-Based X-noiseifier (FIX) and ICA-AROMA.

- Data Imputation: Experimental machine learning-based predictive models to impute missing timepoints due to large motion in fMRI data [8].

A systematic comparison of 14 retrospective motion correction pipelines found that those combining various strategies of signal regression and volume scrubbing reduced the fraction of connectivity edges contaminated by motion to <1%, compared to significant residual bias when using only simple rigid body motion correction [8].

Advanced Motion Phenotyping Frameworks

Beyond treating motion as a confounder, researchers are developing frameworks to quantify motion as a behavioral phenotype itself. The Motion Sensing Superpixels (MOSES) computational framework represents one such approach, measuring and characterizing biological motion with a superpixel "mesh" formulation [24]. This method enables systematic quantification of complex motion phenotypes in time-lapse imaging data, capturing both single-cell and collective migration patterns without requiring precise cell segmentation [24].

MOSES differs fundamentally from traditional Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) approaches by enabling continuous tracking of cellular motion and extraction of rich feature sets that can be used to create distinctive motion "signatures" for different biological conditions [24]. This approach has been applied to study boundary formation dynamics between different epithelial cell types, revealing how complex cellular dynamics relate to pathological processes [24].

Diagram 1: MNAR Data Exclusion Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Management and Phenotyping

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Motion Correction Software | FSL's MCFLIRT, AFNI's 3dvolreg, ICA-AROMA | Retrospective motion correction for fMRI data |

| Motion Metrics | Framewise Displacement (FD), DVARS | Quantifying head motion for scrubbing thresholds |

| Motion Phenotyping Tools | MOSES (Motion Sensing Superpixels) | Quantitative analysis of cellular motion patterns |

| Quality Control Metrics | Surface Hole Number (SHN) | Automated quality assessment approximating manual ratings |

| Experimental Assays | Co-culture boundary formation assays | Study cell population dynamics and motion phenotypes |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Phenotyping

The MOSES framework employs a specific methodology for motion phenotyping that can be adapted to various research contexts:

- Cell Culture and Preparation: Three epithelial cell lines (EPC2, CP-A, OE33) are cultured in pairwise combinations to model tissue boundaries [24].

- Fluorescent Labeling: Different cell populations are labeled with lipophilic membrane dyes (e.g., red and green fluorescent markers) to enable tracking [24].

- Co-culture Setup: Cells are separated by a removable divider (500µm width) in a 24-well plate, which is removed after 12 hours to allow migration [24].

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Live cell imaging over extended periods (up to 6 days) captures motion dynamics [24].

- MOSES Analysis: Application of the superpixel mesh formulation to extract motion features without requiring precise cell segmentation [24].

- Phenotype Classification: Unsupervised analysis of motion signatures to identify distinct motion phenotypes across experimental conditions [24].

Diagram 2: Motion as Phenotype vs. Exclusion

Addressing the MNAR problem in clinical research requires a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize and handle motion-related data. Rather than treating motion solely as a confounder to be eliminated, researchers should recognize it as a meaningful behavioral phenotype that provides insights into clinical status and symptom severity. Moving forward, the field must adopt more sophisticated approaches that maximize data retention through advanced correction methods while simultaneously analyzing motion patterns as clinically relevant variables. This dual approach—combining technical improvements in motion correction with analytical frameworks that incorporate motion as a behavioral measure—will enhance the validity, reproducibility, and clinical relevance of neuroimaging research across developmental and psychiatric disorders.

Large-scale neuroimaging datasets, such as the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, have been transformative for developmental neuroscience, offering unprecedented statistical power to detect subtle brain-behavior relationships. However, this power is predicated on data quality. A critical and pervasive challenge is in-scanner head motion, a systematic source of artifact that is not random noise. In developmental populations and individuals with certain behavioral traits, motion is more prevalent, creating a systematic bias that can inflate effect sizes and produce spurious findings. This case study examines how motion artifact led to inflated effect sizes within the ABCD Study, the methodologies used to uncover this bias, and the subsequent framework developed to quantify and mitigate its impact, a crucial consideration for both basic research and clinical drug development.

Quantitative Evidence of Motion-Induced Bias

Analyses of the ABCD dataset have provided concrete, quantitative evidence demonstrating how motion artifacts systematically bias structural and functional imaging measures.

Structural MRI (sMRI) Findings

A manual quality assessment of over 10,000 sMRI scans from the ABCD Study revealed that more than half (55%) were of suboptimal quality, even after passing standard automated quality control. This systematic data quality issue led to predictable biases in cortical measurements [3].

Table 1: Impact of Scan Quality on Cortical Measurements and Group Differences in ABCD sMRI Data

| Scan Quality Inclusion | Impact on Cortical Measurements | Number of Significant Brain Regions Showing Group Differences (Aggressive Behavior) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Scans Only (n=4,600) | Reference standard | 3 | Baseline effect |

| Including Moderate-Quality Scans | Consistent underestimation of cortical thickness; overestimation of cortical surface area [3] | 21 | Effect size in some regions more than doubled [3] |

| Including All Scans (n>10,000) | Introduction of systematic error growing as quality decreases [3] | 43 | Catapulted number of significant findings, indicating spurious associations [3] |

Functional MRI (fMRI) Findings

In resting-state fMRI, head motion introduces a spatially systematic signature, decreasing long-distance connectivity and increasing short-range connectivity [25]. Even after rigorous denoising, residual motion artifact significantly confounds trait-FC relationships.

Table 2: Trait-Specific Motion Impact on Functional Connectivity (FC) in ABCD fMRI Data

| Analysis Condition | Percentage of Traits with Significant Motion Overestimation | Percentage of Traits with Significant Motion Underestimation | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| After Standard Denoising (ABCD-BIDS) | 42% (19/45 traits) [25] | 38% (17/45 traits) [25] | Motion artifact remains a major confound even after standard processing |

| After Motion Censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) | Reduced to 2% (1/45 traits) [25] | No reduction (17/45 traits remained significant) [25] | Censoring mitigates overestimation but is ineffective for/ may worsen underestimation |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Motion Artifact

Manual Quality Control of sMRI

- Objective: To evaluate the assumption that large sample sizes inherently overcome the noise introduced by poor-quality scans [3].

- Method: A team manually rated 10,295 sMRI scans from 9- and 10-year-olds in the ABCD Study using a 4-point scale (1 = minimal correction needed, 4 = unusable). This manual rating served as the gold standard against which automated metrics were compared [3].

- Analysis: Researchers examined how the inclusion of scans with different quality ratings (1-4) affected standard sMRI measures (cortical thickness, surface area) and the effect sizes in brain-behavior analyses (e.g., comparing children with/without aggressive behaviors) [3].

The SHAMAN Framework for fMRI

- Objective: To devise a trait-specific "motion impact score" to determine if specific brain-behavior relationships are confounded by residual motion [25].

- Method: Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) capitalizes on the stability of traits over time. For each participant, the fMRI timeseries is split into high-motion and low-motion halves. SHAMAN measures the difference in the correlation structure between these halves [25].

- Analysis:

- A significant difference between the halves indicates that motion impacts the trait-FC effect.

- A motion impact score aligned with the trait-FC effect direction indicates overestimation.

- A score opposite to the trait-FC effect indicates underestimation.

- Permutation testing yields a p-value for the motion impact score, distinguishing significant from non-significant motion confounding [25].

Evaluating Automated Quality Metrics

- Objective: To identify a practical, automated alternative to labor-intensive manual quality control for large datasets [3].

- Method: The performance of automated quality-control metrics was compared against manual ratings. The metric known as Surface Hole Number (SHN), which estimates imperfections in cortical reconstruction, was found to best approximate manual quality ratings [3].

- Application: While not as effective as manual control, using SHN as a covariate or to "stress-test" results by analyzing how effect sizes change as low-quality scans are added/removed was proposed as a feasible best practice [3].

Motion Artifact Workflow and Impact

The following diagram illustrates the procedural pathway through which head motion introduces systematic bias into neuroimaging data analysis, leading to inflated effect sizes and spurious findings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing rigorous motion correction requires a suite of methodological "reagents." The table below details essential tools and approaches for mitigating motion bias, as identified in research on the ABCD Study.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods for Motion Mitigation in Neuroimaging

| Tool/Solution Category | Specific Example | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Automated QC Metrics | Surface Hole Number (SHN) [3] | An automated proxy for image quality that estimates imperfections in cortical surface reconstruction; used to flag potentially problematic scans without manual inspection. |

| Motion Censoring | Framewise Displacement (FD) thresholding (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) [25] | Post-hoc removal of individual fMRI volumes with excessive motion. Effective at reducing motion overestimation but can introduce bias by disproportionately excluding data from certain populations [25]. |

| Trait-Specific Motion Quantification | SHAMAN Framework [25] | A statistical method that assigns a specific "motion impact score" to a given brain-behavior association, distinguishing between overestimation and underestimation. |

| Inclusive Analysis Methods | Motion-Ordering & Bagging [26] | Statistical techniques that retain high-motion participants in analyses, improving sample representation and reproducibility of effect sizes, particularly for minoritized youth [26]. |

| Denoising Algorithms | ICA-AROMA, FIX [8] | ICA-based algorithms that automatically identify and remove motion-related components from fMRI data without censoring entire volumes. |

| Effect Size Benchmarking | BrainEffeX Web App [27] | A resource providing "typical" effect sizes from large datasets, allowing researchers to compare their findings against benchmarks to identify potentially inflated results. |

The investigation into motion-inflated effect sizes within the ABCD Study yields critical lessons for developmental neuroimaging and the application of large datasets in clinical neuroscience. Key takeaways include:

- Motion is a Systematic Bias, Not Random Noise: It introduces predictable, spatially structured artifacts that can inflate or deflate effect sizes, leading to both false positives and false negatives [3] [25].

- Quality Trumps Quantity: Simply increasing sample size without rigorous quality control can compound errors and produce specious, overly optimistic findings [3].

- Standard Pipelines Are Insufficient: The default preprocessing and QC pipelines of large, publicly available datasets may not adequately remove motion artifact, requiring additional vigilance from researchers [3] [25].

- Equity Implications: Standard exclusion practices for high-motion data can disproportionately affect clinically severe or minoritized populations, biasing samples and limiting generalizability [26] [8].

To ensure robust and reproducible results, researchers should adopt a multi-pronged strategy: employ trait-specific motion impact analyses like SHAMAN; use automated metrics like SHN to stress-test the robustness of findings; consider inclusive methods like motion-ordering to maintain representative samples; and benchmark observed effect sizes against realistic expectations from resources like BrainEffeX. For drug development professionals relying on neuroimaging biomarkers, a critical appraisal of motion correction methodologies is essential to de-risk decisions based on potentially confounded data.

Correcting the Signal: A Methodological Toolkit for Motion Artifact Mitigation

In-scanner head motion represents a fundamental confound in developmental neuroimaging, introducing systematic bias that impedes our understanding of neurodevelopmental mechanisms [28]. This technical challenge is particularly acute in pediatric populations, where increased head motion can lead to severe noise and artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, inflating correlations between adjacent brain areas and decreasing correlations between spatially distant territories [28]. The ramifications extend beyond technical inconvenience to potentially skew scientific findings, as motion artifacts have been shown to create spurious brain-behavior associations that can masquerade as neural effects [2] [25]. This whitepaper examines three core acquisition-based strategies—mock scanner training, real-time motion correction, and pediatric-friendly protocols—that collectively address this challenge at the data collection stage, before systematic biases become embedded in research datasets.

The problem is especially pronounced in large-scale neuroimaging initiatives. Recent analyses of major datasets like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study reveal that more than half of structural MRI scans may be of suboptimal quality, even after standard automated quality-control steps [3]. Incorporating these scans introduces systematic bias, consistently underestimating cortical thickness and overestimating cortical surface area in analyses [3]. For functional MRI (fMRI), the situation is equally concerning, as head motion introduces spatially systematic artifacts that decrease long-distance connectivity while increasing short-range connectivity, particularly affecting default mode network measurements [25]. Given that motion tendencies follow a U-shaped trajectory across development—with high motion in young children decreasing through adolescence and rising again in later adulthood—failure to address these acquisition challenges disproportionately affects studies of developmental populations [2].

Mock Scanner Training: Principles and Implementation

Mock scanner training involves placing participants in an environment designed to mimic the actual MRI scanning environment, with the dual purpose of desensitizing them to the unusual surroundings and training them to limit movement. This approach capitalizes on behavioral preparation and systematic desensitization to reduce anxiety and increase compliance, particularly crucial for children who may find the scanning environment intimidating. By familiarizing participants with scanner noises, confined spaces, and the requirement to remain still, mock training addresses both the psychological and physiological aspects of motion control.

Efficacy and Empirical Support

Recent research demonstrates that even brief mock scanner sessions yield substantial benefits for data quality. A growth curve study with 123 Chinese children and adolescents found that a single 5.5-minute training session in an MRI mock scanner effectively suppressed head motion during subsequent actual scanning [28] [29]. The study revealed that younger children (aged 6-9 years) derived the greatest benefit from such training, suggesting that mock scanning should be particularly prioritized for early childhood studies [28]. Another investigation examining longer scanning protocols found that mock scanner training, when combined with complementary in-scanner methods like weighted blankets and an incentive system, enabled the acquisition of low-motion fMRI data from pediatric participants (age 7-17) undergoing a 60-minute scan protocol [30]. This finding is significant because shortened scan protocols—a common approach to minimizing motion—reduce the reliability of functional connectivity measures, creating a tension between data quantity and quality [30].

The quantitative benefits of mock scanner training are substantial across multiple metrics, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Efficacy Metrics of Mock Scanner Training

| Metric | Without Mock Training | With Mock Training | Improvement | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scans with mean FFD >0.10 mm | 71.4% | 32.3% | 54.8% reduction | [30] |

| Scans with mean FFD >0.15 mm | 50.0% | 9.38% | 81.2% reduction | [30] |

| Scans with mean FFD >0.20 mm | 33.9% | 4.17% | 87.7% reduction | [30] |

| Optimal training duration | - | 5.5 minutes | - | [28] |

| Maximum benefit age group | - | 6-9 years | - | [28] |

FFD = Frame-to-frame displacement

Implementation Protocol

Successful implementation of a mock scanner protocol involves multiple components that collectively prepare the child for the actual scanning environment:

Environment Replication: The mock scanner should closely mimic the actual MRI environment, including bore size, lighting, and acoustic properties. Playing audio recordings of MRI sequence sounds throughout the session helps desensitize participants to the unusual noises they will encounter [31].

Behavioral Training: Participants practice lying still with verbal feedback provided about head position. This often incorporates a visual feedback system where children can see real-time metrics of their head movement and learn to control it [30].

Habituation Sessions: Multiple brief sessions may be more effective than a single extended session, particularly for children with anxiety or neurodevelopmental disorders.

Positive Reinforcement: An incentive system that rewards successful stillness helps motivate participation and compliance. This can include token economies or small rewards for meeting motion thresholds [30].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a comprehensive mock scanning protocol that integrates these elements:

Mock Scanner Implementation Workflow

Real-Time Motion Monitoring and Correction

Real-time motion monitoring represents a technological approach to the motion challenge, providing immediate feedback to researchers and technicians during data acquisition. Unlike mock scanning, which is preventive, real-time monitoring is an active acquisition strategy that enables adaptive scanning protocols based on participant performance.

FIRMM and Real-Time Monitoring Efficacy

Framewise Integrated Real-Time MRI Monitoring (FIRMM) software exemplifies this approach by calculating and displaying head motion metrics (specifically framewise displacement, FD) to the MRI technician in real time during fMRI scans [31]. This enables technicians to extend scanning periods when participants are exhibiting low motion and potentially conclude scanning once sufficient high-quality data has been acquired, optimizing scanning efficiency. The software has demonstrated particular value in infant neuroimaging, where motion is especially prevalent and challenging to control.

In a comparative study of infant scanning with (n = 407) and without (n = 295) FIRMM, researchers found that adding real-time motion monitoring to state-of-the-art infant scanning protocols significantly increased the amount of usable fMRI data (defined as FD ≤ 0.2 mm) acquired per infant [31]. This advantage persisted across diverse infant populations, including both preterm and term-born infants, indicating its robustness across developmental stages. The real-time feedback enables a more dynamic approach to data acquisition than fixed-duration protocols, potentially reducing the need for repeated scanning sessions or excessive data collection to compensate for motion-contaminated frames.

Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of real-time motion monitoring requires both technical infrastructure and procedural adaptations:

Software Integration: FIRMM or comparable systems must be integrated with the MRI scanner's data output, typically requiring specific software installations and compatibility checks.

Technician Training: MRI technicians must be trained to interpret real-time motion metrics and make informed decisions about scan continuation based on both motion data and protocol requirements.

Protocol Adaptation: Scanning protocols may need adjustment to accommodate the flexible scanning durations enabled by real-time monitoring, particularly for task-based fMRI where complete paradigm administration remains important.

Complementary Techniques: Real-time monitoring is most effective when combined with other motion mitigation strategies. For example, one study demonstrated successful implementation of FIRMM alongside natural sleep protocols in infants, using feed-and-swaddle techniques and vacuum-based immobilizers [31].

Pediatric-Friendly Scanning Protocols

Pediatric-friendly scanning protocols encompass a range of adaptations to the MRI environment and procedures that acknowledge the unique needs and characteristics of developing populations. These strategies focus on creating a supportive, minimally stressful environment that naturally facilitates reduced motion.

Core Protocol Components

Several evidence-based components comprise effective pediatric-friendly scanning protocols:

Natural Sleep Protocols: For infants and young children, scanning during natural sleep represents one of the most effective motion reduction strategies. The "feed and swaddle" approach involves modifying feeding schedules to ensure feeding 30-45 minutes before scanning, followed by snug swaddling in pre-warmed sheets [31]. This approach is often complemented by vacuum immobilizers (e.g., MedVac Bag) that gently secure the infant's position when air is evacuated [31].

Acoustic Adaptations: Playing audio recordings of MRI sequence sounds throughout the scan session can help infants stay asleep by minimizing disruptive changes in ambient noise [31]. Additionally, appropriate ear protection that is comfortable for extended wear is essential.

Environmental Comfort: Pre-warming blankets, minimizing transitions between environments, and creating a calm, dimly lit scanning suite can reduce anxiety and promote stillness.

Age-Appropriate Engagement: For older children who remain awake during scanning, age-appropriate explanations, engaging visual stimuli, and breaks when needed can improve compliance. Some protocols incorporate movie viewing during scans to maintain engagement and reduce motion [30].

Specialized Populations

Pediatric-friendly protocols require particular adaptation for special populations, including children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research indicates that while age is the strongest determinant of head motion across all pediatric populations, children with neurodevelopmental disorders may not display the typical pattern of decreasing motion with age seen in neurotypical children [2]. This highlights the need for persistent motion mitigation strategies throughout childhood for these populations. Studies have demonstrated that with comprehensive protocols incorporating mock scanning and in-scanner adaptations, even children with ASD can successfully complete extended scanning protocols with low motion [30].

Successful implementation of acquisition-based motion mitigation strategies requires specific materials and resources. The following table catalogues essential components of an effective motion mitigation toolkit for developmental neuroimaging research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Mitigation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mock Scanner Systems | Mock scanner with audio recording of sequence sounds | Familiarizes participants with MRI environment; enables practice with stillness | [28] [29] [30] |

| Real-Time Monitoring Software | FIRMM (Framewise Integrated Real-Time MRI Monitoring) | Provides real-time head motion metrics to guide acquisition length | [31] |

| Immobilization Devices | MedVac Vacuum Splint Infant Immobilizer; weighted blankets | Gently secures position without distress; provides proprioceptive input | [31] [30] |

| Visual Feedback Systems | Real-time head motion display for participants | Enables children to visualize and control their head movement | [30] |

| Acoustic Adaptation Tools | MRI sequence sound recordings; appropriate ear protection | Maintains sleep state by minimizing disruptive noise changes | [31] |

| Environmental Comfort Items | Pre-warmed blankets; dimmable lighting; calming visuals | Reduces anxiety and promotes relaxation during scanning | [31] [30] |

Integration and Best Practices

The most effective approach to mitigating motion artifacts in developmental neuroimaging involves integrating multiple strategies rather than relying on a single solution. The following diagram illustrates how these strategies can be combined throughout the research timeline:

Integrated Motion Mitigation Timeline

Synthesized Best Practices

Based on current evidence, the following integrated practices represent the state of the art in acquisition-based motion mitigation:

Implement Brief Mock Scanner Training: A single 5.5-minute mock scanner session provides substantial motion reduction, particularly for children aged 6-9 years [28]. This should be standard practice in pediatric neuroimaging studies.

Leverage Real-Time Monitoring for Scanning Efficiency: FIRMM software should be incorporated to guide acquisition length based on motion metrics, particularly for resting-state fMRI [31]. This approach reduces the need for oversampling while ensuring adequate high-quality data.

Adapt Protocols to Developmental Stage: Infant protocols should prioritize natural sleep with feed-and-swaddle approaches, while protocols for older children should incorporate engagement strategies and clear, age-appropriate instructions [31] [30].

Employ Complementary Immobilization: Weighted blankets and vacuum immobilizers provide gentle physical reminders to remain still without causing distress [30].

Assess Motion Impact Post-Hoc: For studies examining traits associated with motion (e.g., psychiatric conditions), methods like SHAMAN should be employed to calculate motion impact scores for specific trait-FC relationships, distinguishing between overestimation and underestimation effects [25].