Temporal Dynamics of Motion-Related Signal Changes: From fMRI Artifact Correction to Drug Discovery Applications

This article comprehensively examines the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes, a critical challenge and opportunity in biomedical research.

Temporal Dynamics of Motion-Related Signal Changes: From fMRI Artifact Correction to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively examines the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes, a critical challenge and opportunity in biomedical research. We first establish the foundational principles of temporal signal distortions, exploring their sources in both neuroimaging and molecular pharmacology. The review then details advanced methodological approaches for characterization and correction, including Motion Simulation (MotSim) models and entropy-based analysis of receptor dynamics. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls like interpolation artifacts and provides optimization strategies for data processing. Finally, we present validation frameworks and comparative analyses of correction techniques, highlighting their impact on functional connectivity measures and ligand-receptor interaction studies. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a unified framework for understanding, correcting, and leveraging temporal motion properties across experimental domains.

Understanding Temporal Signal Distortions: Sources and Impact on Data Integrity

Defining Temporal Properties in Motion-Related Signal Changes

Temporal properties of motion-related signal changes represent a critical frontier in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research, particularly for resting-state functional connectivity (rs-fMRI) analysis. Head motion introduces complex, temporally structured artifacts that systematically bias functional connectivity estimates, potentially leading to spurious brain-behavior associations in clinical and research settings. This technical guide synthesizes current methodologies for modeling, quantifying, and correcting these temporal properties, with emphasis on computational approaches that account for the non-linear relationship between head movement and signal changes. We present experimental protocols for simulating motion-related signal changes, evaluate the efficacy of various denoising strategies, and introduce emerging frameworks for assessing residual motion impacts on functional connectivity metrics. The insights provided herein aim to establish rigorous standards for temporal characterization of motion artifacts, enabling more accurate neurobiological inferences in motion-prone populations including children, elderly individuals, and patients with neurological disorders.

In-scanner head motion constitutes one of the most significant sources of noise in resting-state functional MRI, introducing complex temporal artifacts that systematically distort estimates of functional connectivity [1]. The challenge is particularly acute because even sub-millimeter movements can cause significant distortions to functional connectivity metrics, and uncorrected motion-related signals can bias group results when motion differences exist between populations [1]. The temporal properties of these motion-related signal changes are characterized by non-stationary, state-dependent fluctuations that correlate with underlying neural signals of interest, creating particular challenges for disentangling artifact from biology [2].

Traditional approaches to motion correction have assumed a linear relationship between head movement parameters and resultant signal changes, but this assumption fails to account for the complex interplay between motion, magnetic field inhomogeneities, and tissue boundary effects [1]. At curved edges of image contrast where motion in one direction causes a signal increase, the same motion in the opposite direction may not produce a symmetrical decrease. Similarly, in regions with nonlinear intensity gradients, displacements produce asymmetric signal changes depending on direction and magnitude [1]. Understanding these temporal properties is essential for developing effective correction methods.

This technical guide examines the defining temporal properties of motion-related signal changes through the lens of advanced modeling approaches, experimental protocols, and quantitative frameworks. By establishing comprehensive methodologies for characterizing these temporal dynamics, we aim to provide researchers with tools to distinguish motion-related artifacts from genuine neural signals, thereby enhancing the validity of functional connectivity findings across diverse populations and clinical applications.

Computational Models of Motion-Related Signal Changes

Limitations of Traditional Motion Regression

The most common approach for addressing motion artifacts in rs-fMRI involves regressing out the six rigid-body realignment parameters (three translations and three rotations) along with their temporal derivatives [1]. Variants of this approach include time-shifted and squared versions of these parameters [1]. However, these methods fundamentally assume that motion-related signal changes maintain a linear relationship with estimated realignment parameters, an assumption that frequently fails to account for the complex reality of how motion affects the MR signal.

The linearity assumption breaks down in several biologically relevant scenarios. At tissue boundaries with curved contrast edges, motion in one direction may produce signal increases while opposite motion fails to produce comparable decreases. In regions with nonlinear intensity gradients, displacement magnitude and direction produce asymmetric effects. Furthermore, motion can result in sampling different proportions of tissue classes at any given location, producing signal changes that may be positive, negative, or neutral depending on the specific proportions sampled [1]. These non-linear effects necessitate more sophisticated modeling approaches that better capture the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes.

Motion Simulation (MotSim) Framework

The Motion Simulation (MotSim) framework represents a significant advancement in modeling motion-related signal changes by creating a voxel-wise estimate of signal changes induced by head motion during scanning [1]. This approach involves rotating and translating a single acquired echo-planar imaging volume according to the negative of the estimated motion parameters, generating a simulated dataset that models motion-related signal changes present in the original data [1].

The MotSim methodology proceeds through several well-defined stages:

- Volume Selection: A single brain volume (typically after discarding initial transient volumes) is selected as the reference for motion simulation.

- Motion Application: The reference volume is rotated and translated according to the inverse of the estimated motion parameters using interpolation methods (typically linear or 5th-order polynomial).

- Motion Correction: The MotSim dataset undergoes motion correction with rigid body volume registration, creating a MotSimReg dataset that reflects imperfections introduced by interpolation and motion estimation errors.

- Regressor Generation: Nuisance regressors are derived through temporal principal components analysis (PCA) applied to voxel time series from the MotSim datasets.

Table 1: Motion Simulation Model Variants

| Model Name | Description | Number of Regressors | Components Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12Forw | First 12 principal components of MotSim dataset ("forward model") | 12 | Motion-induced signal changes |

| 12Back | First 12 principal components of realigned MotSim dataset ("backward model") | 12 | Residual motion after interpolation and registration |

| 12Both | First 12 principal components of spatially concatenated MotSim and MotSimReg datasets | 12 | Combined forward and backward model components |

| 12mot | Standard approach: 6 motion parameters + derivatives | 12 | Linear motion parameters and temporal derivatives |

| 24Both | First 24 principal components of concatenated MotSim and MotSimReg datasets | 24 | Extended combined model |

The MotSim framework offers significant advantages over traditional motion parameter regression. It accounts for significantly greater fraction of signal variance, results in higher temporal signal-to-noise ratio, and produces functional connectivity estimates that are less correlated with motion compared to the standard realignment parameter approach [1]. This improvement is particularly valuable in populations where motion is prevalent, such as pediatric patients or individuals with neurological disorders.

Probability Density-Based Models of Temporal Anticipation

Recent research has challenged longstanding assumptions about how the brain represents event probability over time, with implications for understanding temporal properties of motion-related signal changes. Whereas traditional models proposed that neural systems compute hazard rates (the probability that an event is imminent given it hasn't yet occurred), emerging evidence suggests the brain employs a computationally simpler representation based on probability density functions (PDFs) [3].

The PDF-based model contrasts with hazard rate models in three fundamental aspects. First, it posits that the brain represents event probability across time in a computationally simpler form than the hazard rate by estimating the PDF directly. Second, in the PDF-based model, uncertainty in elapsed time estimation is modulated by event probability density rather than increasing monotonically with time. Third, the model hypothesizes a direct inverse relationship between event probability and reaction time, where high probability predicts short reaction times and vice versa [3].

This conceptual framework has implications for understanding how motion-related signal changes evolve temporally during task-based fMRI paradigms where temporal anticipation plays a role in both neural processing and motion artifacts.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Characterization

Participant Recruitment and Data Acquisition

Comprehensive characterization of motion-related signal changes requires carefully controlled acquisition protocols. A representative study design involves recruiting healthy adult participants (e.g., N=55 with balanced gender representation) with no history of neurological or psychological disorders [1]. Each participant should provide written informed consent following Institutional Review Board approved protocols.

Table 2: Representative fMRI Acquisition Parameters for Motion Studies

| Parameter | Setting | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Scanner Type | 3T GE MRI scanner (MR750) | Comparable systems from other manufacturers suitable |

| Session Duration | 10 minutes | Longer acquisitions improve signal-to-noise ratio |

| Task Condition | Eyes-open fixation | Yields more reliable results than eyes-closed |

| Sequence | Echo planar imaging (EPI) | Standard BOLD fMRI sequence |

| Repetition Time (TR) | 2.6 s | Balances temporal resolution and spatial coverage |

| Echo Time (TE) | 25 ms | Optimized for BOLD contrast at 3T |

| Flip Angle | 60° | Standard for gradient-echo EPI |

| Field of View | 224mm × 224mm | Complete brain coverage |

| Matrix Size | 64 × 64 | Standard resolution for rs-fMRI |

| Slice Thickness | 3.5 mm | Typical for whole-brain coverage without gaps |

| Number of Slices | 40 | Complete brain coverage in TR=2.6s |

During scanning, participants should be instructed to lie still with eyes fixated on a cross-hair or similar fixation point. The resting condition with eyes open and fixating has been shown to yield slightly more reliable results compared to either eyes closed or eyes open without fixation [1]. Each participant should ideally undergo multiple scanning sessions to assess within-subject reliability of motion effects.

Structural imaging should include T1-weighted images acquired using an MPRAGE sequence with approximately 1mm isotropic resolution for accurate anatomical registration and normalization to standard template space [1].

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) Protocols

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) utilizes MR-compatible optical tracking systems to update gradients and radio-frequency pulses in response to head motion during image acquisition [4]. This approach can significantly improve data quality, particularly in acquisitions affected by large head motion.

To quantitatively assess PMC efficacy, researchers can employ paradigms where subjects are instructed to perform deliberate movements (e.g., crossing legs at will) during alternating blocks with and without PMC enabled [4]. This generates head motion velocities ranging from 4 to 30 mm/s, allowing direct comparison of data quality under identical motion conditions with and without correction.

PMC has been shown to drastically increase the temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) of rs-fMRI data acquired under motion conditions. Studies demonstrate that leg movements without PMC reduce tSNR by approximately 45% compared to sessions without intentional movement, while the same movements with PMC enabled reduce tSNR by only 20% [4]. Additionally, PMC improves the spatial definition of major resting-state networks, including the default mode network, visual network, and central executive networks [4].

Motion Impact Assessment Using SHAMAN Framework

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) framework provides a method for computing trait-specific motion impact scores that quantify how residual head motion affects specific brain-behavior associations [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for traits associated with motion, such as psychiatric disorders where participants may have higher inherent motion levels.

The SHAMAN protocol involves these key steps:

Data Preparation: Process resting-state fMRI data using standard denoising pipelines (e.g., ABCD-BIDS pipeline including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter regression).

Framewise Displacement Calculation: Compute framewise displacement (FD) for each timepoint as a scalar measure of head motion.

Timeseries Splitting: Split each participant's fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on FD thresholds.

Connectivity Calculation: Compute functional connectivity matrices separately for high-motion and low-motion halves.

Trait-FC Effect Estimation: Calculate correlation between trait measures and functional connectivity separately for high-motion and low-motion halves.

Motion Impact Score Computation: Quantify the difference in trait-FC effects between high-motion and low-motion halves, with positive scores indicating motion overestimation and negative scores indicating motion underestimation of trait effects.

Statistical Significance Testing: Use permutation testing and non-parametric combining across pairwise connections to establish significance of motion impact scores.

Application of SHAMAN to large datasets (e.g., n=7,270 participants from the ABCD Study) has revealed that after standard denoising without motion censoring, 42% (19/45) of traits had significant (p < 0.05) motion overestimation scores and 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores [2]. Censoring at FD < 0.2 mm reduced significant overestimation to 2% (1/45) of traits but did not decrease the number of traits with significant motion underestimation scores [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Motion Effects

Temporal Signal-to-Noise Ratio (tSNR) Metrics

Temporal signal-to-noise ratio provides a crucial quantitative measure of data quality in the presence of motion. Studies systematically comparing tSNR across motion conditions consistently demonstrate the disruptive effects of head movement on data quality. Prospective Motion Correction has been shown to significantly mitigate these effects, with PMC-enabled acquisitions maintaining approximately 25% higher tSNR compared to non-PMC acquisitions under identical motion conditions [4].

The quantitative relationship between motion magnitude and tSNr reduction follows a characteristic pattern where increased motion velocity correlates with exponential decay in tSNR. This relationship highlights the non-linear impact of motion on data quality, with even moderate motion (5-10 mm/s) producing substantial reductions in temporal stability.

Motion-Functional Connectivity Effect Sizes

The effect size of motion on functional connectivity can be quantified by regressing each participant's average framewise displacement against their functional connectivity matrices, generating motion-FC effect matrices with units of change in FC per mm FD [2]. These analyses reveal systematic patterns where motion produces decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity, most notably in default mode network regions [2].

Quantitative assessments demonstrate that the motion-FC effect matrix typically shows a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix, indicating that connection strength tends to be weaker in participants who move more [2]. This negative correlation persists even after rigorous motion censoring at FD < 0.2 mm (Spearman ρ = -0.51), demonstrating the persistent nature of motion effects on connectivity measures [2].

Critically, the decrease in FC due to head motion is often larger than the increase or decrease in FC related to traits of interest, highlighting why motion can easily produce spurious brain-behavior associations if not adequately addressed [2].

Efficacy Metrics for Motion Correction Methods

Different motion correction approaches can be quantitatively compared using standardized efficacy metrics:

Table 3: Motion Correction Method Efficacy Comparison

| Method | Variance Explained by Motion | Relative Reduction vs. Minimal Processing | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Processing | 73% | Baseline (motion correction only) | Frame realignment without additional denoising |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | 23% | 69% reduction | Includes GSR, respiratory filtering, motion regression, despiking |

| PMC + Minimal Processing | 38% | 48% reduction | Prospective correction during acquisition |

| PMC + ABCD-BIDS | 14% | 81% reduction | Combined prospective and retrospective correction |

The ABCD-BIDS denoising pipeline achieves a relative reduction in motion-related variance of approximately 69% compared to minimal processing alone [2]. However, even after comprehensive denoising, 23% of signal variance remains explainable by head motion, underscoring the challenge of complete motion artifact removal [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AFNI Software Suite | Preprocessing and analysis of fMRI data | Implements volume registration, censoring, nuisance regression |

| 3T MRI Scanner with EPI | BOLD signal acquisition | Standard field strength for fMRI; EPI sequence for speed |

| MR-Compatible Optical Tracking | Real-time head motion monitoring | Essential for Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) |

| Motion Simulation (MotSim) Algorithm | Generation of motion-related regressors | Creates PCA-based nuisance regressors from simulated motion |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) Metric | Quantitative motion measurement | Scalar summary of between-volume head movement |

| SHAMAN Framework | Trait-specific motion impact scoring | Quantifies motion overestimation/underestimation of effects |

| Temporal PCA | Dimensionality reduction of noise regressors | Extracts principal components from motion-simulated data |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | Integrated denoising pipeline | Combines GSR, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking |

Methodological Workflows

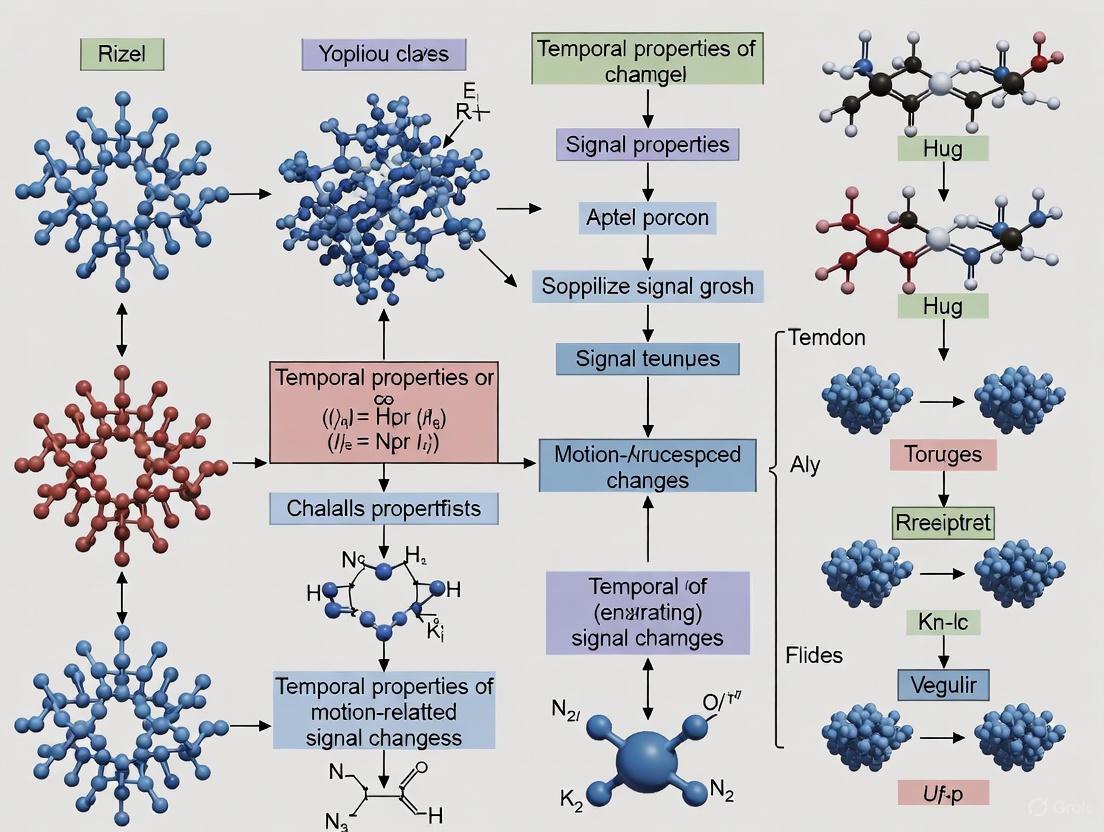

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for motion characterization and correction, combining the MotSim regressor generation with comprehensive denoising strategies.

The temporal properties of motion-related signal changes represent a fundamental challenge in functional neuroimaging that demands sophisticated characterization and correction approaches. Traditional methods based on linear regression of motion parameters fail to capture the complex, non-linear relationship between head movement and signal artifacts. The Motion Simulation framework provides a significant advancement by generating biologically plausible nuisance regressors that account for interpolation errors and motion estimation inaccuracies. Combined with prospective motion correction during acquisition and rigorous post-hoc assessment of motion impacts using frameworks like SHAMAN, researchers can substantially mitigate the confounding effects of motion on functional connectivity measures. As neuroimaging continues to expand into clinical populations with inherent motion tendencies, including children, elderly individuals, and patients with neurological disorders, these advanced methods for defining and addressing temporal properties of motion-related signal changes will become increasingly essential for valid neurobiological inference.

Head Motion in fMRI and Conformational Dynamics in Molecular Interactions

Within the context of a broader thesis on the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes, this technical guide explores two seemingly disparate domains united by their dependence on precise motion detection and correction: functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain and conformational dynamics in molecular interactions. In fMRI, head motion constitutes a major confounding artifact that systematically biases data, particularly threatening the validity of studies involving populations prone to movement, such as children or individuals with neurological disorders [2]. In molecular biology, conformational dynamics refer to the essential movements of proteins and nucleic acids that govern their biological functions, such as binding and catalysis [5] [6]. Understanding and quantifying the temporal evolution of motion in both systems is not merely a technical challenge but a fundamental prerequisite for generating reliable, interpretable data in neuroscience and drug development.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the sources and impacts of motion in these fields, summarizes current methodological approaches for its management, and presents standardized protocols and reagent toolkits to aid researchers in implementing these techniques. The focus on temporal properties underscores that motion is not a static nuisance but a dynamic process whose properties must be characterized over time to be effectively mitigated or understood.

The Impact and Artifacts of Head Motion in fMRI

Physiological and Physical Origins of Motion Artifacts

Head motion during fMRI acquisition introduces a complex array of physical phenomena that corrupt the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal. These effects are multifaceted and extend beyond simple image misalignment. As detailed in [7], the consequences of motion include spin-history effects, where movement alters the magnetization history of spins; changes in reception coil sensitivity profiles as the head moves relative to stationary receiver coils; and modulation of magnetic field (B0) inhomogeneities as the head rotates in the static magnetic field. These effects collectively introduce systematic bias into functional connectivity (FC) measures, not merely random noise.

Critically, the impact of motion is spatially systematic. It consistently causes decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity, most notably within the default mode network [2]. This specific pattern creates a severe confound in studies of clinical populations, such as children or individuals with psychiatric disorders, who may move more frequently. For instance, early studies concluding that autism spectrum disorder decreases long-distance FC were likely measuring motion artifact rather than a genuine neurological correlate [2].

Quantitative Impact on Data Quality

The quantitative impact of head motion on fMRI data is substantial, even after standard denoising procedures. As demonstrated in a large-scale analysis of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Head Motion on Resting-State fMRI

| Metric | Before Denoising | After ABCD-BIDS Denoising | After Censoring (FD < 0.2 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Variance Explained by Motion | 73% [2] | 23% [2] | Not Reported |

| Correlation between Motion-FC Effect and Average FC Matrix | Not Reported | Spearman ρ = -0.58 [2] | Spearman ρ = -0.51 [2] |

| Traits with Significant Motion Overestimation | Not Reported | 42% (19/45 traits) [2] | 2% (1/45 traits) [2] |

The strong negative correlation indicates that participants who moved more showed consistently weaker connection strengths across the brain. Furthermore, the effect size of motion on FC was often larger than the trait-related effects under investigation [2]. A separate study on prospective motion correction (PMC) for fetal fMRI reported a 23% increase in temporal SNR and a 22% increase in the Dice similarity index after correction, highlighting the potential gains in data quality [8].

Methodological Approaches for Motion Management in fMRI

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC)

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) systems actively track head movement and adjust the slice acquisition plane in real-time during the scan. One advanced implementation for fetal fMRI integrates U-Net-based segmentation and rigid registration to track fetal head motion, using motion data from one repetition time (TR) to guide adjustments in subsequent frames with a latency of just one TR [8]. This real-time adjustment mitigates artifacts at their source, before they are embedded in the data. PMC has been shown to be particularly effective in reducing the spin-history effects that retrospective correction cannot address [7].

Retrospective Motion Correction

Retrospective correction is applied after data acquisition during the preprocessing stage. The most common method is rigid-body realignment, which uses six parameters (translations and rotations along the x, y, and z-axes) to realign all volumes in a time series to a reference volume [9] [10]. This is typically performed using tools like FSL's MCFLIRT or the algorithms implemented in BrainVoyager, which can use trilinear or sinc interpolation for resampling [9] [10]. While essential, this method alone is insufficient as it does not correct for intra-volume motion or spin-history effects [7].

Additional retrospective denoising strategies include:

- Nuisance Regression: Including the 6 realignment parameters (and their derivatives) as regressors in the statistical model.

- Frame Censoring (Spiking): Identifying and removing high-motion volumes based on a framewise displacement (FD) threshold (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) [2] [11].

- Advanced Algorithms: Methods like ICA-based cleanup (e.g., ICA-AROMA), global signal regression, and respiratory filtering are often combined in pipelines like the ABCD-BIDS pipeline [2].

Real-Time Feedback and Behavioral Interventions

Reducing motion at the source is highly effective. Real-time feedback systems, such as the FIRMM software, provide participants with visual cues about their head motion during the scan [11]. For example, a crosshair may change color from white (FD < 0.2 mm) to yellow (0.2 mm ≤ FD < 0.3 mm) to red (FD ≥ 0.3 mm). This approach, combined with between-run feedback reports, has been shown to significantly reduce head motion during both resting-state and task-based fMRI [11].

Conformational Dynamics in Molecular Interactions

Significance in Biomolecular Function

Proteins, RNA, and DNA are inherently dynamic molecules that sample a landscape of conformations to perform their functions. These conformational changes are critical for processes such as antibody-antigen recognition, the function of intrinsically disordered proteins, and protein-nucleic acid binding [5]. The transition states between stable conformations represent the "holy grail" in chemistry, as they dictate the rates and pathways of biomolecular processes [6]. Understanding these dynamics is therefore essential for rational drug design, where the goal is often to stabilize a particular conformation or inhibit a functional transition.

Methodological Advances for Studying Molecular Motion

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations are a primary tool for studying conformational changes, allowing researchers to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. The recently developed DynaRepo repository provides a foundation for dynamics-aware deep learning by offering over 1100 µs of MD simulation data for approximately 450 complexes and 270 single-chain proteins [5].

A key challenge has been the automatic identification of sparsely populated transition states within massive MD datasets. The novel deep learning method TS-DAR (Transition State identification via Dispersion and vAriational principle Regularized neural networks) addresses this by framing the problem as an out-of-distribution (OOD) detection task [6]. TS-DAR embeds MD simulation data into a hyperspherical latent space, where it can efficiently identify rare transition state structures located at free energy barriers. This method has been successfully applied to systems like the AlkD DNA motor protein, revealing new insights into how hydrogen bonds govern the rate-limiting step of its translocation along DNA [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Real-Time Motion Feedback in Task-Based fMRI

This protocol is adapted from [11].

- Participant Setup and Instruction: After standard head stabilization with foam padding, provide the participant with clear instructions on the importance of remaining still. For the feedback group, explain the meaning of the visual cues (e.g., white cross for FD < 0.2 mm, yellow for 0.2-0.3 mm, red for ≥ 0.3 mm).

- Software Configuration: Configure the FIRMM (or equivalent) software to receive real-time image data from the scanner. Set the framewise displacement (FD) thresholds for the visual feedback display.

- Data Acquisition: Begin the task-based fMRI acquisition. The software calculates FD for each volume and updates the visual feedback presented to the participant in the scanner.

- Between-Run Feedback: After each functional run, show the participant a Head Motion Report. This report should include a percentage score (0-100%) and a graph of their motion over time. Encourage them to improve their score on the next run.

- Data Analysis: Compare the average FD and number of high-motion events (e.g., FD > 0.2 mm) between feedback and control groups using linear mixed-effects models to account for within-participant correlations.

Protocol: Identifying Transition States with TS-DAR

This protocol is based on the methodology described in [6].

- System Preparation: Select the protein or protein-nucleic acid system of interest. Obtain its initial atomic coordinates from a database like the Protein Data Bank.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Solvate the system in an explicit water box, add ions to neutralize charge, and minimize energy. Heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) and equilibrate. Run a production MD simulation for a sufficient duration to observe the conformational change of interest (typically hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds). Perform multiple replicate simulations to improve sampling.

- Data Preparation: Extract the atomic coordinates (trajectories) from the MD simulations. Pre-process the data as required by the TS-DAR framework, which may include aligning structures to a common reference to remove global rotation and translation.

- TS-DAR Analysis: Input the pre-processed MD data into the TS-DAR deep learning framework. The model will automatically embed the data into a hyperspherical latent space and identify out-of-distribution data points corresponding to transition states.

- Validation and Interpretation: Analyze the identified transition state structures. Validate them by examining their position along the reaction coordinate and their structural features (e.g., broken/formed bonds, angles, dihedrals). Use this insight to understand the energy landscape and rate-limiting steps of the conformational change.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Motion-Correction and Dynamics Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Field of Use |

|---|---|---|

| FIRMM Software | Provides real-time calculation of framewise displacement (FD) to give participants visual feedback on their head motion during an fMRI scan. | fMRI [11] |

| U-Net-based Segmentation Model | A deep learning model used for real-time, automatic segmentation of the fetal head in fMRI images to enable prospective motion tracking. | Fetal fMRI [8] |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | A standardized fMRI denoising pipeline that incorporates global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion parameter regression, and despiking to reduce motion artifacts. | fMRI (Post-processing) [2] |

| MCFLIRT Tool (FSL) | A widely used tool for performing rigid-body retrospective motion correction on fMRI time-series data. | fMRI (Post-processing) [9] |

| DynaRepo Repository | A curated repository of macromolecular conformational dynamics data, including extensive Molecular Dynamics (MD) trajectories for proteins and complexes. | Molecular Dynamics [5] |

| TS-DAR Framework | A deep learning method that uses out-of-distribution detection in a hyperspherical latent space to automatically identify transition states from MD simulation data. | Molecular Dynamics [6] |

| GROMACS/AMBER | High-performance MD simulation software packages used to generate atomic-level trajectories of biomolecular motion. | Molecular Dynamics |

The precise characterization and management of motion—whether in the macro-scale of a human head within an MRI scanner or the atomic-scale fluctuations of a protein—are fundamental to advancing biomedical research. In fMRI, failure to adequately address head motion introduces systematic bias that can produce spurious brain-behavior associations, thereby jeopardizing the validity of scientific findings and their application in clinical trials. In molecular biology, capturing conformational dynamics is central to understanding mechanism and function. The methodologies outlined in this guide, from real-time prospective correction and deep learning-based denoising for fMRI to advanced MD simulations and transition state identification for proteins, provide a robust toolkit for researchers. As both fields continue to evolve, the integration of these sophisticated, motion-aware approaches will be critical for enhancing the reliability of data, the accuracy of biological models, and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions developed from this knowledge.

The Nonlinear Nature of Motion-Induced Signal Artifacts

Motion-induced artifacts represent a fundamental challenge in biomedical signal acquisition and neuroimaging, corrupting data integrity and threatening the validity of scientific and clinical conclusions. While often perceived as simple noise, the relationship between physical motion and the resulting signal artifact is profoundly nonlinear and complex. This in-depth technical guide explores the nonlinear nature of these artifacts, framing the discussion within a broader thesis on the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes. Understanding these nonlinear characteristics is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical prerequisite for developing effective correction algorithms and ensuring reliable data interpretation in drug development and clinical neuroscience. The core of the problem lies in the failure of linear models to fully capture the artifact's behavior, as motion induces signal changes through multiple, interdependent mechanisms that do not scale proportionally with the magnitude of movement [12] [1].

Nonlinear Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

Fundamental Nonlinear Mechanisms

Motion artifacts manifest through several distinct nonlinear mechanisms across different imaging and signal acquisition modalities:

Nonlinear Signal Intensity Relationships: In fMRI, at curved tissue boundaries or regions with nonlinear intensity gradients, a displacement in one direction does not produce the same magnitude or even polarity of signal change as a displacement in the opposite direction. For instance, motion at a curved edge where contrast exists may cause a signal increase with movement in one direction, while the same motion in the opposite direction fails to produce a symmetrical decrease [1].

Spin History and Excitation Effects: In MRI, motion alters the spin excitation history in a nonlinear fashion. When a brain region moves into a plane that has recently been excited, its spins may have different residual magnetization compared to a stationary spin, creating signal artifacts that persist beyond the movement itself [12].

Interpolation Artifacts: During image reconstruction and realignment, interpolation processes introduce nonlinear errors, particularly near high-contrast boundaries. These errors are compounded when motion estimation itself is imperfect, creating a cascade of nonlinear effects [12] [1].

Interactions with Magnetic Field Properties: Head motion interacts with intrinsic magnetic field inhomogeneities, causing distortions in EPI time series that cannot be modeled through simple linear transformations [12].

Partial Volume Effects: Motion causes shifting tissue classifications at voxel boundaries, where the resulting signal represents a nonlinear mixture of different tissue types. This effect is particularly pronounced at the brain's edge, where large signal increases occur due to partial volume effects with cerebrospinal fluid or surrounding tissues [12].

Spatial and Temporal Properties

The spatial distribution of motion artifacts demonstrates clear nonlinear patterns. Biomechanical constraints of the neck create a gradient where motion is minimal near the atlas vertebrae and increases with distance from this anchor point. Frontal regions typically show the highest motion burden, largely due to the prevalence of y-axis rotation (nodding movement) [12]. This spatial heterogeneity interacts nonlinearly with the artifact's temporal dynamics.

Temporally, motion produces both immediate, circumscribed signal changes and longer-duration artifacts that can persist for 8-10 seconds post-movement. The immediate effects include signal drops that scale nonlinearly with motion magnitude, maximal in the volume acquired immediately after an observed movement [12]. The origins of longer-duration artifacts remain partially unexplained but may involve motion-related changes in physiological parameters like CO2 levels from yawning or deep breathing, or slow equilibration of large signal disruptions [12].

Table 1: Characteristics of Motion Artifacts Across Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Manifestation | Temporal Properties | Key Nonlinear Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Increased signal at brain edges; global signal decreases in parenchyma | Immediate signal drops; persistent artifacts (8-10s); spectral power shifts | Spin history effects; interpolation errors; nonlinear intensity relationships at boundaries |

| Structural MRI | Blurring, ghosting, ringing in phase-encoding direction | Single acquisition corruption | Complex k-space perturbations; partial volume effects |

| EEG/mo-EEG | Channel-specific artifacts from electrode movement | Muscle twitches (sharp transients); gait-related oscillations; baseline shifts | Non-stationary spectral contamination; amplitude bursts from electrode displacement |

| Cardiac Mapping | Myocardial border distortions; quantification errors | Through-plane motion between acquisitions | Partial volume effects; registration errors in parametric maps |

Quantitative Analysis of Motion Artifacts and Correction Performance

Impact on Functional Connectivity

In functional connectivity research, motion artifacts introduce systematic biases rather than random noise, particularly problematic because in-scanner motion frequently correlates with variables of interest such as age, clinical status, and cognitive ability [12]. Even small amounts of movement cause significant distortions to connectivity estimates, potentially biasing group comparisons in clinical trials and neurodevelopmental studies.

The spectral characteristics of motion artifacts further complicate their removal. Research has demonstrated that motion affects specific frequency bands differentially, with power transferring from lower to higher frequencies with age—a phenomenon that cannot be fully explained by head motion alone [13]. This frequency-dependent impact means that simple band-pass filtering is insufficient for complete artifact removal, as motion artifacts contaminate the same frequency ranges that contain neural signals of interest.

Performance of Deep Learning Correction Methods

Recent advances in deep learning have produced several promising approaches for motion artifact correction, with quantitative metrics demonstrating their effectiveness across modalities.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Deep Learning Artifact Correction Methods

| Method | Modality | Architecture | Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGAN for MRI [14] | Head MRI (T2-weighted) | Conditional Generative Adversarial Network | SSIM: >0.9 (26% improvement); PSNR: >29 dB (7.7% improvement) | Direction-dependent performance; requires large training datasets |

| Motion-Net for EEG [15] | Mobile EEG | 1D U-Net with Visibility Graph features | Artifact reduction (η): 86% ±4.13; SNR improvement: 20 ±4.47 dB; MAE: 0.20 ±0.16 | Subject-specific training required; computationally intensive |

| AnEEG [16] | Conventional EEG | GAN with LSTM layers | Improved NMSE, RMSE, CC, SNR, and SAR compared to wavelet techniques | Limited validation across diverse artifact types |

| FastSurferCNN [17] | Structural MRI | Fully Convolutional Network | Higher test-retest reliability than FreeSurfer under motion corruption | Segmentation accuracy dependent on ground truth quality |

The conditional GAN (CGAN) approach for head MRI exemplifies how deep learning can address nonlinear artifacts. When trained on 5,500 simulated motion artifacts with both horizontal and vertical phase-encoding directions, the model learned to generate corrected images with structural similarity (SSIM) indices exceeding 0.9 and peak signal-to-noise ratios (PSNR) above 29 dB. The improvement rates for SSIM and PSNR were approximately 26% and 7.7%, respectively, compared to the motion-corrupted images [14]. Notably, the most robust model was trained on artifacts in both directions, highlighting the importance of comprehensive training data that captures the full spectrum of artifact manifestations.

Experimental Protocols for Motion Artifact Research

MRI Motion Artifact Simulation and CGAN Correction

Protocol Objective: To generate realistic motion-corrupted MRI images and train a deep learning model for artifact reduction [14].

Materials and Equipment:

- T2-weighted axial head MRI images from healthy volunteers (e.g., 24 slices per participant)

- MRI simulator with motion simulation capabilities

- Deep learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) with CGAN implementation

- High-performance computing resources with GPU acceleration

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire T2-weighted images using fast spin-echo sequence parameters: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 90 ms, matrix size = 256 × 256, FOV = 240 × 240 mm², slice thickness = 5.0 mm.

- Motion Simulation:

- Generate translated images by shifting original images by ±10 pixels with one-pixel intervals in vertical, horizontal, and diagonal directions.

- Generate rotated images by rotating original images by ±5° with 0.5° intervals around the image center.

- Create 80 types of movement images (20 translation + 20 rotation + 20 diagonal + 20 rotation).

- Convert images to k-space using Fourier transform.

- Randomly select sequential matrix data from translated and rotated images.

- Rearrange selected data for phase encoding to create k-space data containing motion artifacts.

- Apply inverse Fourier transform to generate simulated images with motion artifacts.

- Dataset Preparation:

- Create 5,500 motion artefact images in both horizontal and vertical phase-encoding directions.

- Split data: 90% for training (4,455 images), 10% of training for validation (495 images), 10% for testing (550 images).

- Normalize pixel values to range (0, 1) for input and (0, 255) for output.

- Model Training:

- Implement CGAN with generator and discriminator networks.

- Train with motion-corrupted images as input and motion-free images as ground truth.

- Use adversarial loss to enforce higher-order consistency in output images.

- Validation:

- Compare corrected images with original motion-free images using SSIM and PSNR metrics.

- Evaluate model robustness to different artifact directions and severities.

MotSim Model for Improved fMRI Motion Regression

Protocol Objective: To create an improved model of motion-related signal changes in fMRI using motion-simulated regressors [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Resting-state fMRI data (e.g., EPI sequence: TR = 2.6 s, TE = 25 ms, matrix size = 64×64, 40 slices)

- T1-weighted structural images (e.g., MPRAGE sequence: 1 mm isotropic resolution)

- Processing software (e.g., AFNI, FSL) with volume registration and PCA capabilities

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire resting-state fMRI during eyes-open fixation (10 minutes) and T1-weighted structural images.

- Motion Simulation (MotSim) Dataset Creation:

- Select one volume (e.g., 4th volume) from preprocessed fMRI data as reference.

- Create a 4D dataset by applying the inverse of the estimated motion parameters to this reference volume using linear interpolation.

- This generates a time series where signal changes are solely due to motion.

- Nuisance Regressor Extraction:

- Forward Model (12Forw): Perform temporal PCA on the whole-brain MotSim dataset, retaining the first 12 principal components.

- Backward Model (12Back): Realign the MotSim dataset using standard volume registration, then perform PCA on the realigned data.

- Combined Model (12Both): Spatially concatenate MotSim and realigned MotSim datasets, then perform PCA.

- Model Comparison:

- Compare MotSim models against standard 12-parameter model (6 realignment parameters + derivatives).

- Evaluate models based on variance explained, temporal signal-to-noise ratio improvement, and functional connectivity estimates.

- Validation:

- Assess residual motion-artifact contamination in functional connectivity matrices.

- Compare motion-to-connectivity relationships across correction methods.

Motion-Net for EEG Motion Artifact Removal

Protocol Objective: To remove motion artifacts from mobile EEG signals using a subject-specific deep learning approach [15].

Materials and Equipment:

- Mobile EEG system with accelerometer

- Computing environment with deep learning framework (TensorFlow/PyTorch)

- EEG recording setup with ground-truth reference capability

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Record EEG signals with synchronized accelerometer data.

- Cut data according to experimental triggers and resample to synchronize EEG and accelerometer signals.

- Apply baseline correction using polynomial fitting.

- Feature Extraction:

- Extract raw EEG signals and compute visibility graph (VG) features to capture signal structure.

- Combine raw signals and VG features for input to neural network.

- Model Architecture and Training:

- Implement 1D U-Net (Motion-Net) with encoder-decoder structure.

- Train model separately for each subject (subject-specific approach).

- Use artifact-contaminated signals as input and clean reference signals as target.

- Validation:

- Evaluate using artifact reduction percentage (η), SNR improvement, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

- Compare performance across different motion types (gait, head movements, muscle artifacts).

Visualization of Methodologies and Signal Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate key methodologies and relationships in motion artifact research, created using DOT language with specified color palette constraints.

Motion Artifact Simulation and Correction Workflow

Motion Artifact Simulation and Correction

MotSim Regressor Generation Process

MotSim Regressor Generation Process

Nonlinear Motion Artifact Mechanisms

Nonlinear Motion Artifact Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Motion Artifact Investigation

| Item | Specifications | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| MRI Phantom | Anthropomorphic head phantom with tissue-equivalent properties | Controlled motion studies without participant variability |

| Motion Tracking System | Optical tracking (e.g., MoCap) with sub-millimeter accuracy | Ground truth motion measurement independent of image-based estimates |

| Deep Learning Framework | TensorFlow/PyTorch with GPU acceleration | Implementation of CGAN, U-Net, and other correction architectures |

| EEG with Accelerometer | Mobile EEG system with synchronized 3-axis accelerometer | Correlation of motion events with EEG artifacts |

| Motion Simulation Software | Custom k-space manipulation tools | Generation of realistic motion artifacts for algorithm training |

| PCA Toolbox | MATLAB/Python implementation with temporal PCA capabilities | Extraction of motion-related components from simulated and real data |

| Quality Metrics Suite | SSIM, PSNR, FD, DVARS calculation scripts | Quantitative assessment of artifact severity and correction efficacy |

The nonlinear nature of motion-induced signal artifacts presents a multifaceted challenge that demands sophisticated analytical approaches. Traditional linear models prove insufficient for complete characterization and correction, as demonstrated by the complex spatial, temporal, and spectral properties of these artifacts. The emergence of deep learning methods, particularly those employing generative adversarial networks and specialized motion simulation techniques, offers promising avenues for addressing these nonlinear relationships. The continued development and validation of these approaches is essential for ensuring data integrity in both basic neuroscience research and clinical applications, including pharmaceutical development where accurate biomarker quantification is critical. Future research directions should focus on unifying correction approaches across imaging modalities, developing real-time artifact mitigation systems, and establishing standardized validation frameworks for motion correction algorithms.

The accurate interpretation of biological data is paramount across scientific disciplines, from systems-level neuroscience to molecular pharmacology. A pervasive challenge confounding this interpretation is the presence of unmodeled temporal signal changes originating from non-biological sources. This whitepaper examines the consequences of such artifacts, with a specific focus on motion-related signal changes in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and their impact on the study of functional connectivity (FC). Furthermore, we explore the parallel challenges in ligand-receptor binding studies, where similar principles of kinetic analysis are susceptible to confounding variables. Framed within a broader thesis on the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes, this guide details the systematic errors introduced by these artifacts, surveys advanced methodologies for their mitigation, and provides a framework for robust data interpretation aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Motion Artifacts in Functional Connectivity fMRI

The Nature and Impact of the Problem

In-scanner head motion is one of the largest sources of noise in resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), causing significant distortions in estimates of functional connectivity [1] [18]. Even small, sub-millimeter movements introduce systematic biases that are not fully removed by standard realignment techniques [18] [19]. The core issue is that motion-induced signal changes are non-linearly related to the estimated realignment parameters, violating the assumptions of common nuisance regression approaches [1].

These artifacts manifest as spurious correlation structures throughout the brain. Analyses have consistently shown that subject motion decreases long-distance correlations while increasing short-distance correlations [18] [2]. This pattern is spatially systematic, most notably affecting networks like the default mode network [2]. The consequences are severe: if uncorrected, these motion-related signals can bias group results, particularly when comparing populations with differential motion characteristics (e.g., patients versus controls, or children versus adults) [1] [18].

Quantitative Characterization of Motion Effects

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Head Motion on Functional Connectivity

| Metric | Effect of Motion | Quantitative Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-distance FC | Decrease | Strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) between motion and average FC matrix | [2] |

| Short-distance FC | Increase | Systematic increases observed, particularly in default mode network | [18] [2] |

| Signal Variance | Increase | Motion explains 73% of variance after minimal processing; 23% remains after denoising | [2] |

| Temporal SNR | Decrease | Significantly improved with advanced motion correction (MotSim) | [1] |

Advanced Methodologies for Motion Correction

Motion Simulation (MotSim) Approach

The Motion Simulation (MotSim) method represents a significant advancement over standard motion correction techniques that rely on regressing out realignment parameters and their derivatives [1] [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Volume Selection: Extract a single volume from the original fMRI data after initial preprocessing steps (removal of initial transient volumes, slice-timing correction).

- Motion Simulation: Create a 4D dataset by rotating and translating this single volume according to the inverse of the estimated motion parameters, typically using linear interpolation.

- Re-registration: Apply rigid-body volume registration to the MotSim dataset (creating MotSimReg) to model imperfections from interpolation and motion estimation errors.

- Principal Components Analysis (PCA): Perform temporal PCA on voxels from:

- The MotSim dataset ("forward model")

- The registered MotSim dataset ("backward model")

- Both datasets concatenated ("both model")

- Nuisance Regression: Use the first 12 principal components as nuisance regressors in the general linear model to account for motion-related signal changes.

This method accounts for a significantly greater fraction of variance than the standard 12-parameter model (6 realignment parameters + derivatives), results in higher temporal signal-to-noise ratio, and produces functional connectivity estimates that are less correlated with motion [1].

Framewise Censoring and Quality Metrics

An alternative or complementary approach involves identifying and censoring individual time points (frames) corrupted by excessive motion [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Calculate Framewise Displacement (FD): Compute the root mean square of the differential of the 6 realignment parameters at each time point.

- Set Censoring Threshold: Establish an FD threshold (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mm) to flag corrupted frames.

- Data Removal: Exclude flagged frames from functional connectivity calculations.

- Validation: Apply methods like SHAMAN (Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks) to compute trait-specific motion impact scores that distinguish between overestimation and underestimation of trait-FC effects [2].

Table 2: Motion Correction Methods Comparison

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12-Parameter Regression | 6 realignment parameters + temporal derivatives | Standard, simple to implement | Assumes linear relationship; leaves residual artifacts |

| Motion Simulation (MotSim) | PCA of simulated motion data | Accounts for non-linear effects; superior variance explanation | Computationally intensive; complex implementation |

| Framewise Censoring | Removal of high-motion time points | Effective reduction of spurious correlations | Reduces data; requires careful threshold selection |

| SHAMAN Analysis | Split-half analysis of high/low motion frames | Quantifies trait-specific motion impact | Requires sufficient scan duration for splitting |

Parallel Challenges in Ligand-Receptor Binding Studies

Dimensionality and Context in Binding Kinetics

The study of receptor-ligand interactions faces analogous challenges in data interpretation, particularly regarding the dimensional context of measurements. Traditional surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measures binding in three dimensions (3D) using purified receptors and ligands removed from their native environment [21]. However, in situ interactions occur in two dimensions (2D) with both molecules anchored in apposing membranes, resulting in fundamentally different units for kinetic parameters [21].

Critical Dimensional Differences:

- 3D Binding Affinity (K_a): Units of M⁻¹

- 2D Binding Affinity (K_a): Units of μm²

- 3D On-rate (k_on): Units of M⁻¹s⁻¹

- 2D On-rate (k_on): Units of μm²s⁻¹

This dimensional discrepancy means that kinetics measured by SPR cannot be used to derive reliable information on 2D binding, potentially leading to misinterpretation of binding mechanisms and affinities [21].

Environmental Regulation of Binding Kinetics

Cellular microenvironment factors significantly influence receptor-ligand binding kinetics, adding layers of complexity to data interpretation:

- Protein-Membrane Interaction: Membrane-anchored receptors and ligands are restricted to lateral diffusion along membranes, and local membrane separation fluctuations strongly influence binding probability [21].

- Biomechanical Force: Applied mechanical force can significantly alter bond lifetimes and binding affinities through conformational changes in ligands or receptors [21].

- Bioelectric Microenvironment: Local electrical properties can modulate interactions through electrostatic forces that affect molecular orientation and binding probability [21].

These regulatory mechanisms create context-dependent binding kinetics that cannot be fully captured by simplified in vitro assays, potentially leading to inaccurate predictions of in vivo behavior.

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Motion Simulation (MotSim) Methodology

Ligand-Receptor Interaction Network

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Motion Artifact and Binding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Field |

|---|---|---|

| AFNI Software Suite | Preprocessing and analysis of fMRI data; implementation of MotSim | fMRI/FC |

| Siemens MAGNETOM Scanner | Acquisition of BOLD contrast-sensitive gradient echo EPI sequences | fMRI/FC |

| MP-RAGE Sequence | T1-weighted structural imaging for anatomical reference | fMRI/FC |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | In vitro 3D measurement of receptor-ligand binding kinetics | Binding Studies |

| Fluorescence Dual Biomembrane Force Probe | Measurement of bond lifetimes under mechanical force | Binding Studies |

| Coarse-Grained MD Simulation | Computational modeling of membrane-protein interactions | Binding Studies |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Statistical modeling of membrane fluctuations and binding | Binding Studies |

| Connectome-constrained LRIA (CLRIA) | Inference of ligand-receptor interaction networks | Multi-scale |

Integrated Data Interpretation Framework

The parallels between motion artifact correction in FC and environmental context in binding studies reveal fundamental principles for robust biological data interpretation:

- Assumption Validation: Critically examine core assumptions (e.g., linearity of motion effects, dimensional context of binding measurements) that might not hold in biological systems [1] [21].

- Multi-scale Integration: Develop methods like CLRIA (connectome-constrained ligand-receptor interaction analysis) that integrate information across spatial and temporal scales [22].

- Environmental Context: Account for the native environment of measurements, whether considering the electromagnetic environment of fMRI or the membrane context of receptor-ligand interactions [21] [19].

- Systematic Artifact Quantification: Implement rigorous quality control metrics, such as motion impact scores for specific trait-FC relationships, to quantify residual artifacts [2].

These principles form a foundation for more accurate data interpretation across neuroscience and molecular pharmacology, ultimately supporting more reliable scientific conclusions and more effective drug development pipelines.

Linking Motion Artifacts to Broader Anthropometric and Cognitive Factors

Within research on the temporal properties of motion-related signal changes, the paradigm is shifting from considering in-scanner motion as a mere nuisance to recognizing it as a source of biologically meaningful information. Motion artifacts in neuroimaging, particularly functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), exhibit structured spatio-temporal patterns that are not random [23]. These patterns are increasingly linked to a broad array of an individual's anthropometric and cognitive characteristics. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence and methodologies, framing motion artifacts within a broader physiological and neurological context. This reframing suggests that subject movement during scanning may reflect fundamental brain-body relationships and shared underlying mechanisms between cardiometabolic risk factors and brain health [24]. Understanding these correlations is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to disentangle confounds from genuine biomarkers in neuroimaging data.

Theoretical Framework: The Body-Brain-Motion Nexus

Physiological Links Between Brain Structure and Body Composition

Foundational research reveals significant, though small-effect-size, associations between brain structure and body composition, providing a basis for understanding motion as a biomarker. Large-scale studies using UK Biobank data (n=24,728 with brain MRI; n=4,973 with body MRI) demonstrate that anthropometric measures show negative, nonlinear associations with global brain structures such as cerebellar and cortical gray matter and the brain stem [24]. Conversely, positive associations have been observed with ventricular volumes. The direction and strength of these associations vary across different tissue types and body metrics.

Critically, adipose tissue measures, including liver fat and muscle fat infiltration, are negatively associated with cortical and cerebellum structures [24]. In contrast, total thigh muscle volume shows a positive association with brain stem and accumbens volume. These body-brain connections suggest that motion during scanning may not merely be a artifact but could reflect these underlying structural and physiological relationships.

Spatio-Temporal Structure of Motion

Even in fMRI data that has undergone standard scrubbing procedures to remove excessively corrupted frames, the retained motion time courses exhibit a clear spatio-temporal structure [23]. This structured motion allows researchers to distinguish subjects into separate groups of "movers" with varying characteristics, rather than representing random noise. This temporal structure in motion artifacts provides the foundation for linking them to broader phenotypic factors.

Table 1: Key Anthropometric and Cognitive Correlates of In-Scanner Motion

| Domain | Specific Factor | Nature of Correlation | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | Adipose Tissue (e.g., VAT, ASAT) | Negative association with cortical/cerebellar gray matter [24] | Body-brain mapping (n=4,973) [24] |

| Anthropometric | Liver Fat (PDFF) | Negative association with brain structure [24] | Body-brain mapping [24] |

| Anthropometric | Muscle Fat Infiltration (MFI) | Negative association with brain structure [24] | Body-brain mapping [24] |

| Anthropometric | Total Thigh Muscle Volume | Positive association with brain stem/accumbens [24] | Body-brain mapping [24] |

| Cognitive/Behavioral | Multiple Cognitive Factors | "Tightly relates to a broad array" of factors [23] | Spatio-temporal motion analysis [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Artifact Investigation

Protocol 1: Mitigating Head Motion Artifact in Functional Connectivity MRI

This validated, high-performance denoising strategy combines multiple model features to target both widespread and focal effects of subject movement [25].

Implementation Steps:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire fMRI data using standardized protocols. The UK Biobank, for instance, uses 3T brain MRI scanners across multiple sites with similar scanners and protocols [24].

- Feature Extraction: Extract a comprehensive set of model features including:

- Physiological signals (e.g., cardiac, respiratory)

- Motion estimates (e.g., framewise displacement)

- Mathematical expansions of motion parameters (e.g., derivatives, squares) to capture motion-related variance [25]

- Image Denoising: Apply the denoising model to the fMRI data. This process requires 40 minutes to 4 hours of computing per image, depending on model specifications and data dimensionality [25].

- Performance Assessment: Implement diagnostic procedures to assess denoising performance. The protocol can reduce motion-related variance to near zero in functional connectivity studies, providing up to a 100-fold improvement over minimal-processing approaches in large datasets [25].

Protocol 2: Reproducing Motion Artifacts for Performance Analysis

This protocol uses a software interface to simulate rigid body motion by changing the scanning coordinate system relative to the object, enabling precise reproduction of motion artifacts correctable with prospective motion correction (PMC) [26].

Implementation Steps:

- Motion Tracking: During an initial patient scan, use an external tracking system (e.g., an MR-compatible optical system) to record head position information in six degrees of freedom (6 DoF) throughout the experiment [26].

- Data Logging: Log all tracking data to a file for subsequent analysis.

- Artifact Reproduction: To reproduce the motion artifacts from the original scan, feed the recorded position changes back into the scanner with the direction of motion reversed. This experiment is performed on a stationary volunteer or phantom [26].

- Quantitative Analysis: Compare the original and reproduced artifacts using quantitative metrics like Average Edge Strength (AES) or visual inspection to validate the reproduction accuracy [26].

Protocol 3: Spatio-Temporal Motion Cartography

This analytical approach characterizes the structured patterns of motion in fMRI data typically retained after standard scrubbing [23].

Implementation Steps:

- Data Preprocessing: Apply standard fMRI preprocessing and scrubbing to remove excessively corrupted frames based on a composite framewise displacement (FD) score.

- Motion Time-Course Analysis: Analyze individual motion time courses from the putatively "clean" time points to identify spatio-temporal structure.

- Subject Grouping: Use this structured motion information to distinguish subjects into separate groups of "movers" with varying characteristics.

- Multivariate Correlation Analysis: Employ multivariate analysis techniques, such as Partial Least Squares (PLS), to identify overlapping modes of covariance between motion patterns and a broad array of behavioral and anthropometric variables [23].

Visualizing Research Workflows

Workflow for Investigating Motion-Physiology-Cognition Links

Motion Artifact Reproduction and Correction Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Analytical Tools for Motion Artifact Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 3T MRI Scanner with Body Coil | Acquisition of high-resolution structural brain and body composition images. | Standardized across sites (e.g., UK Biobank uses similar scanners/protocols) [24]. |

| MR-Compatible Motion Tracking System | Real-time tracking of head movement in six degrees of freedom (6 DoF). | Optical systems (e.g., Metria Innovation) with frame rates up to 85 fps; requires attachment via mouthpiece or nasal marker [26]. |

| Body MRI Analysis Software | Quantification of adipose and muscle tissue from body MRI. | AMRA Medical software for measuring VAT, ASAT, liver PDFF, MFI, TTMV [24]. |

| Image Processing Pipelines | Automated processing of neuroimaging data and extraction of brain morphometry. | FreeSurfer (for regional/global brain measures); eXtensible Connectivity Pipeline (XCP) for functional connectivity denoising [24] [25]. |

| Denoising Software Library | Implementation of high-performance denoising to mitigate motion artifact in fMRI. | Combines physiological signals, motion estimates, and mathematical expansions; 40 min-4 hr compute time per image [25]. |

| Prospective Motion Correction Library | Real-time correction of motion during acquisition by updating the coordinate system. | Software libraries like libXPACE for integrating tracking data into pulse sequences [26]. |

Advanced Characterization and Correction Methods for Temporal Signal Artifacts

The accurate estimation of functional connectivity from resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) is fundamentally compromised by in-scanner head motion, which represents one of the largest sources of noise in neuroimaging data. Even small amounts of movement can cause significant distortions to functional connectivity estimates, particularly problematic in populations where motion is prevalent, such as patients and young children [1]. Current denoising approaches primarily rely on regressing out rigid body realignment parameters and their derivatives, operating under the assumption that motion-related signal changes maintain a linear relationship with these parameters. However, this assumption fails in biological systems where motion-induced signal changes often exhibit nonlinear properties due to complex interactions at curved edges of image contrast and regions with nonlinear intensity gradients [1].

The temporal properties of signal processing systems are conventionally characterized through impulse response functions and temporal frequency responses, with research distinguishing between first-order (luminance modulation) and second-order (contrast modulation) visual mechanisms [27]. Similarly, in fMRI noise correction, recent investigations have revealed that motion parameters in single-band fMRI contain factitious high-frequency content (>0.1 Hz) primarily driven by respiratory perturbations of the B0 field, which becomes aliased in standard acquisition protocols (TR 2.0-2.5 s) and introduces systematic biases in motion estimates [28]. This contamination disproportionately affects specific demographic groups, including older adults, individuals with higher body mass index, and those with lower cardiorespiratory fitness [28]. The MotSim framework addresses these temporal complexities by generating motion-related signal changes that more accurately capture the true temporal characteristics of motion artifacts, moving beyond the limitations of linear modeling approaches.

Core Methodology: The MotSim Framework

Theoretical Foundation and Motion Simulation Dataset Creation

The MotSim methodology fundamentally reimagines motion correction by creating a comprehensive model of motion-related signal changes derived from actual acquired imaging data rather than relying solely on realignment parameters. The theoretical innovation lies in recognizing that motion-induced signal changes are not linearly related to realignment parameters, particularly at curved contrast edges or regions with nonlinear intensity gradients where displacements in opposite directions produce asymmetric signal changes [1]. This approach was previously suggested by Wilke (2012) and substantially expanded in the current implementation [1].

The technical workflow for creating the Motion Simulation (MotSim) dataset involves:

- Volume Selection: A single volume is extracted from the original preprocessed fMRI data after removing initial transient volumes and performing slice-timing correction. Typically, the 4th volume serves as the base, consistent with its use in motion realignment procedures [1].

- Inverse Motion Application: This base volume is rotated and translated according to the inverse of the estimated 6 motion parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) derived from the realignment procedure, creating a 4D dataset where signal changes are purely motion-induced [1].

- Interpolation Method: Linear interpolation is typically used for resampling during motion simulation (default in AFNI's 3dWarp), though follow-up analyses with 5th order interpolation demonstrate consistent results [1].

- Motion Correction: The MotSim dataset then undergoes standard rigid body volume registration (MotSimReg), modeling imperfections introduced by interpolation and motion estimation errors [1].

Motion Regressor Models: From Simulation to Nuisance Variables

The MotSim framework generates several distinct motion regressor models through principal components analysis (PCA) to account for motion-related variance while minimizing the number of nuisance regressors:

Table: MotSim Motion Regressor Models

| Model Name | Description | Components | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12mot | Standard approach | 6 realignment parameters + their derivatives | Linear assumption of motion-signal relationship |

| 12Forw | Forward model | First 12 PCs of MotSim dataset | Complete motion-induced signal changes |

| 12Back | Backward model | First 12 PCs of registered MotSim (MotSimReg) | Residual motion after registration (interpolation errors) |

| 12Both | Combined model | First 12 PCs of spatially concatenated MotSim and MotSimReg | Comprehensive motion representation |

| 24mot | Expanded standard | 6 realignment parameters, previous time points, and squares | Friston (1996) expanded motion model |

| 24Both | Expanded MotSim | First 24 PCs of 'Both' model | Enhanced motion capture with matched regressor count |

Temporal PCA generates linear, uncorrelated components that reflect the main features of signal variations in the motion dataset, ordered by decreasing variance explained (PC1 > PC2 > PC3...). This approach minimizes mutual information between components and has precedent in physiological noise modeling (e.g., CompCor technique) [1]. The critical advantage of MotSim PCA is that derived noise time series originate purely from estimated subject motion, unlikely to contain signals of interest unless neural correlates are motion-synchronous [1].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Participant Recruitment and Data Acquisition Specifications

Validation of the MotSim methodology employed a robust experimental design with fifty-five healthy adults (27 females; average age 40.9 ± 17.5 years, range: 20-77) with no neurological or psychological history. Each participant provided written informed consent under a University of Wisconsin Madison IRB approved protocol and underwent two separate scanning sessions within the same visit to assess reliability [1].

Table: MRI Acquisition Parameters

| Parameter | Structural Acquisition | Functional Acquisition |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence | T1-weighted MPRAGE | Gradient-echo EPI |

| Scanner | 3T GE MR750 | 3T GE MR750 |

| TR | 8.13 ms | 2.6 s |

| TE | 3.18 ms | 25 ms |

| Flip Angle | 12° | 60° |

| FOV | 256mm × 256mm | 224mm × 224mm |

| Matrix Size | 256×256 | 64×64 |

| Slice Thickness | 1 mm | 3.5 mm |

| Number of Slices | 156 | 40 |

| Scan Duration | N/A | 10 minutes |

During functional scanning, participants maintained eyes open fixation on a cross-hair, a resting condition shown to yield slightly more reliable results compared to eyes closed or open without fixation [1]. This protocol standardization minimizes visual network variability while maintaining naturalistic conditions prone to motion artifacts.

Preprocessing Pipeline and Analytical Framework

Data preprocessing implemented through AFNI software followed a comprehensive protocol [1]:

- Removal of first 3 volumes to eliminate MR signal transients

- Slice-timing correction for interleaved acquisition timing differences

- Within-run volume registration for motion correction