The Inflation Problem: Why Small Discovery Sets Undermine Replicability in Scientific Research

This article examines a critical challenge in modern research: the inflation of effect sizes in small discovery datasets and its detrimental impact on replicability.

The Inflation Problem: Why Small Discovery Sets Undermine Replicability in Scientific Research

Abstract

This article examines a critical challenge in modern research: the inflation of effect sizes in small discovery datasets and its detrimental impact on replicability. Drawing on evidence from brain-wide association studies (BWAS), genetics (GWAS), and social-behavioral sciences, we explore the statistical foundations of this problem, methodological solutions for robust discovery, strategies for optimizing study design, and frameworks for validating findings. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current insights to guide the development of more reliable and replicable scientific models, which is a cornerstone for progress in biomedical and clinical research.

The Replicability Crisis and the Root Cause: Effect Size Inflation in Small Samples

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary statistical reason behind inflated findings in small studies? When a true discovery is claimed based on crossing a threshold of statistical significance (e.g., p < 0.05) but the discovery study is underpowered, the observed effects are expected to be inflated compared to the true effect sizes. This is a well-documented statistical phenomenon [1]. In underpowered studies, only the largest effect sizes, often amplified by random sampling variability, are able to reach statistical significance, leading to a systematic overestimation of the true relationship.

FAQ 2: How does sample size directly affect the reproducibility of my findings? Sample size is a critical determinant of reproducibility. In brain-wide association studies (BWAS), for example, the median effect size (|r|) is remarkably small, around 0.01 [2]. With such small true effects, studies with typical sample sizes (e.g., n=25) are statistically underpowered and highly susceptible to sampling variability. This means two independent research groups can draw opposite conclusions about the same association purely by chance [2]. As sample sizes grow into the thousands, replication rates improve and effect size inflation decreases significantly [2].

FAQ 3: Are certain types of studies more susceptible to this problem? Yes, the risk varies. Brain-wide association studies (BWAS) that investigate complex cognitive or mental health phenotypes are particularly vulnerable because the true brain-behaviour associations are much smaller than previously assumed [2]. Similarly, in genomics, gene set analysis results become more reproducible as sample size increases, though the rate of improvement varies by analytical method [3]. Studies relying on multivariate methods or functional MRI may show slightly more robust effects compared to univariate or structural MRI studies, but they still require large samples for reproducibility [2].

FAQ 4: Beyond sample size, what other factors contribute to irreproducible findings? Multiple factors compound the problem of small discovery sets:

- Flexible Data Analysis: The "vibration ratio"—the ratio of the largest to smallest effect obtained from different analytic choices on the same data—can be very large, and this flexibility, coupled with selective reporting, inflates published effects [1].

- Inadequate Measurement Reliability: Low reliability of experimental measurements, whether in behavioural phenotyping or imaging, can further attenuate observed effect sizes and hinder reproducibility [2].

- Publication and Confirmation Biases: The scientific ecosystem often favours the publication of novel, positive results, while null findings and replication failures frequently go unpublished [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Effect Size Inflation and Failed Replications

Symptoms:

- Initial experiment shows a strong, statistically significant association.

- Follow-up studies fail to replicate the finding.

- The effect size measured in subsequent studies is much smaller than the original discovery.

Diagnosis and Solution: This is a classic symptom of the "winner's curse," where effects from underpowered discovery studies are inflated [1].

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acknowledge the Limitation | Understand that effect sizes from small studies are likely inflated and should be interpreted with caution [1]. |

| 2 | Plan for Downward Adjustment | Consider rational down-adjustment of the observed effect size for future power calculations, as the true effect is likely smaller [1]. |

| 3 | Prioritize Large-Scale Replication | Design an independent replication study with a sample size much larger than the original discovery study to obtain a stable, accurate estimate of the effect [2]. |

| 4 | Use Methods that Correct for Inflation | Employ statistical methods designed to correct for the anticipated inflation in the discovery phase [1]. |

Problem 2: Designing a Reproducible Discovery Study

Symptoms:

- Uncertainty about the appropriate sample size for a new line of research.

- History of irreproducible results within your research domain.

Diagnosis and Solution: The study is being designed without a realistic estimate of the true effect size and the sample size required to detect it robustly.

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Consult Consortia Data | Use large-scale consortium data (e.g., UK Biobank, ABCD Study) to obtain realistic, field-specific estimates of true effect sizes, which are often much smaller than reported in the literature [2]. |

| 2 | Power Analysis with Realistic Effects | Conduct a power analysis using the conservatively adjusted (downward) effect size from consortium data, not from small, initial studies [2] [1]. |

| 3 | Pre-register Analysis Plan | Finalize and publicly register your statistical analysis plan before collecting data to prevent flexible analysis and selective reporting [1]. |

| 4 | Allocate Resources for Large N | Plan for sample sizes in the thousands, not the tens, if investigating complex brain-behavioural or genomic associations [2]. |

Quantitative Data on Sample Size and Reproducibility

Table 1: Sample Size Impact on Effect Size and Reproducibility in BWAS [2]

| Sample Size (N) | Typical Median | r | 99% Confidence Interval for an Effect | Replication Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | ~0.01 | ± 0.52 | Highly unstable; opposite conclusions likely | ||

| ~2,000 | ~0.01 | N/A | Top 1% of effects still inflated by ~78% | ||

| >3,000 | 0.01 | N/A | Replication rates improve; largest reproducible effect | r | =0.16 |

Table 2: Impact of Sample Size on Gene Set Analysis Reproducibility [3]

| Sample Size (per group) | Percentage of True Positives Captured | Reproducibility Trend |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20 - 40% | Low and highly variable between methods |

| 20 | >85% | Reproducibility significantly increased |

| Larger samples | Increases further | Results become more reproducible as sample size grows |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Reproducibility Across Sample Sizes Using Real Datasets

This methodology allows researchers to quantify how sample size affects the stability of their own findings [3].

Workflow Diagram:

1. Initial Setup and Data Source:

- Obtain a large-scale original dataset (D) from a public repository (e.g., Gene Expression Omnibus for genomic data, or UK Biobank for neuroimaging data). This dataset should have a large number of both case and control samples (e.g., nC and nT > 50) [3].

2. Replicate Dataset Generation:

- Choose a sample size

n(wherenis less than the number of available cases and controls). - Generate

mreplicate datasets (e.g., m=10) for thisn. Each replicate is created by randomly selectingnsamples from the original controls andnsamples from the original cases, without replacement. This ensures all samples within a replicate are unique [3]. - Repeat this process for a range of

nvalues (e.g., from 3 to 20) to model different study sizes.

3. Analysis and Evaluation:

- Apply the chosen analysis method (e.g., a specific gene set analysis tool or a BWAS pipeline) to each of the replicate datasets for all sample sizes.

- Collect all results, including p-values, effect sizes, and lists of significant hits or enriched pathways.

- Assess reproducibility by measuring the consistency of results across the

mreplicates for eachn. Specificity can be evaluated by testing datasets where both case and control samples are drawn from the actual control group, where any significant finding is a false positive [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Robust and Reproducible Research

| Resource/Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Large-Scale Consortia Data (e.g., UK Biobank, ABCD Study) | Provides realistic, population-level estimates of effect sizes for power calculations and serves as a benchmark for true effects [2]. |

| Pre-registration Platforms (e.g., OSF, ClinicalTrials.gov) | Allows researchers to pre-specify hypotheses, primary outcomes, and analysis plans, mitigating the problem of flexible analysis and selective reporting [1]. |

| Statistical Methods that Correct for Inflation | Provides a statistical framework to adjust for the anticipated overestimation of effect sizes in underpowered studies, leading to more accurate estimates [1]. |

| High-Reliability Measurement Protocols | Improves the signal-to-noise ratio of both behavioural/phenotypic and instrumental (e.g., MRI) measurements, reducing attenuation of observed effect sizes [2]. |

| Data and Code Sharing Repositories | Ensures transparency and allows other researchers to independently verify computational results, a key aspect of reproducibility [4]. |

Logical Pathway to Irreproducibility

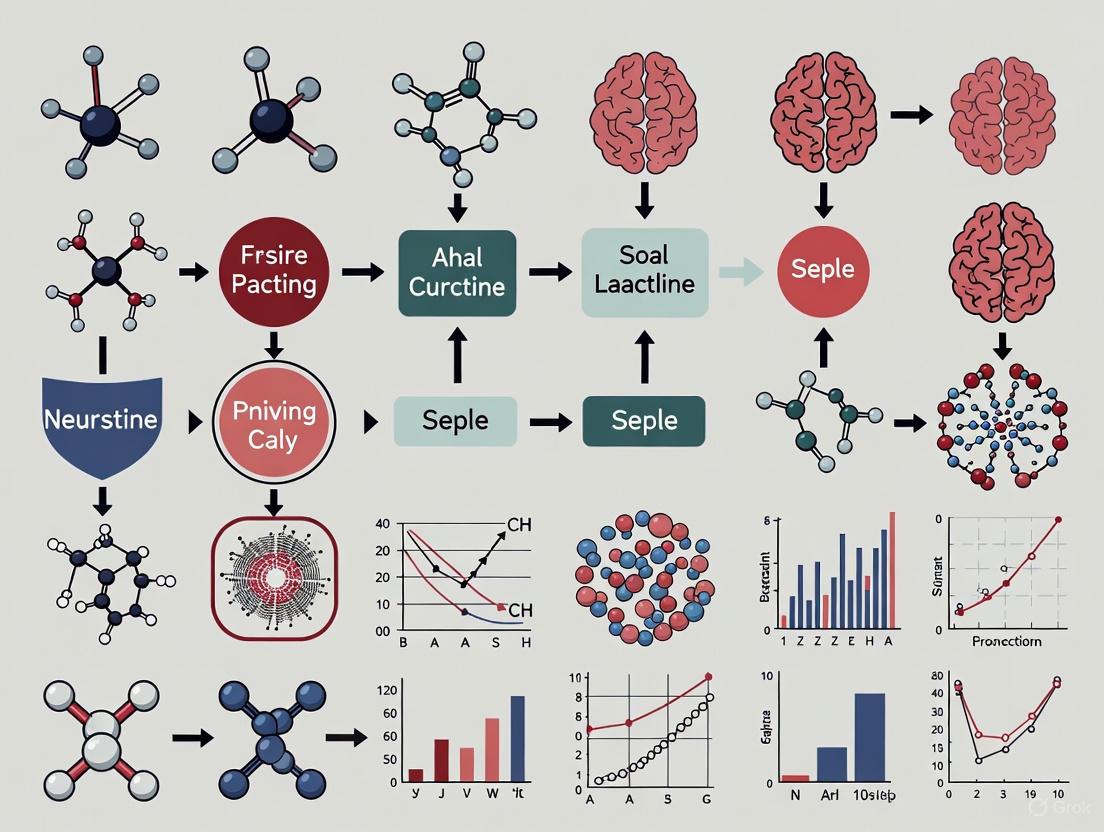

The following diagram illustrates the typical cascade from a small discovery set to an irreproducible finding.

Schematic Diagram:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the Winner's Curse in statistical terms?

The Winner's Curse is a phenomenon of systematic overestimation where the initial discovery of a statistically significant association (e.g., a genetic variant affecting a trait) reports an effect size larger than its true value. It occurs because, in a context of multiple testing and statistical noise, the effects that cross the significance threshold are preferentially those whose estimates were inflated by chance [5] [6]. In essence, "winning" the significance test often means your result is an overestimate.

Why should researchers in drug development be concerned about it?

The Winner's Curse poses a direct threat to replicability and research efficiency. If a discovered association is inflated, any subsequent research—such as validation studies, functional analyses, or clinical trials—will be designed based on biased information. This can lead to replication failures, wasted resources, and flawed study designs that are underpowered to detect the true, smaller effect [5] [7]. For drug development, this can mean pursuing targets that ultimately fail to show efficacy in larger, more rigorous trials.

What are the main statistical drivers of this inflation?

The primary drivers are:

- Low Statistical Power: Studies with small sample sizes have a low probability of detecting a true effect. When a true effect is barely detectable, the only time it will cross the significance threshold is when random sampling error pushes its observed effect size substantially upward [7].

- Significance Thresholding: The practice of selecting only the most extreme results (those passing a p-value threshold like 5×10⁻⁸ in GWAS) for reporting creates an ascertainment bias. This selected set is enriched with overestimates [5].

- The Base Rate of True Effects: In research domains where true effects are rare, a higher proportion of the statistically significant findings will be false positives. The Winner's Curse further ensures that the few true positives that are discovered have inflated effect sizes [8].

How can I quantify the potential impact of the Winner's Curse on my results?

The impact is most severe for effects with lower power and for variants with test statistics close to the significance threshold. One empirical investigation found that for genetic variants just at the standard genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸), the observed genetic associations could be inflated by 1.5 to 5 times compared to their expected value. This inflation drops to less than 25% for variants with very strong evidence for association (e.g., P < 10⁻¹³) [9]. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Empirical Evidence on Effect Size Inflation from the Winner's Curse

| Research Context | P-value Threshold for Discovery | Observed Inflation of Effect Sizes | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mendelian Randomization (BMI) | ( P < 5 \times 10^{-8} ) | Up to 5-fold inflation | [9] |

| Mendelian Randomization (BMI) | ( P < 10^{-13} ) | Less than 25% inflation | [9] |

| Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) | Various (post-WC correction) | Replication rate matched expectation after correction | [5] |

What practical steps can I take to avoid or correct for the Winner's Curse?

- Increase Sample Size: The most effective method is to conduct discovery studies with large sample sizes, which increases power and reduces the magnitude of the Winner's Curse [7].

- Use Independent Samples: Always use a completely independent cohort for replication. The replication sample must not have been used in any part of the discovery process [5] [9].

- Apply Statistical Corrections: Before replication, apply statistical methods to correct the observed effect sizes from the discovery cohort for the anticipated bias. These methods can provide a less biased estimate of the true effect for power calculations [5].

- Select Stronger Signals: When moving to validation, prioritize variants that are highly significant (e.g., P < 10⁻¹³) as they suffer less from inflation, making replication more likely [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Replication failure despite a strong initial signal.

Potential Cause: The initial discovery was a victim of the Winner's Curse. The effect size used to power the replication study was an overestimate, leading to an underpowered replication attempt.

Solution:

- Re-estimate Power: Recalculate the power of your replication study using a Winner's Curse-corrected effect size estimate from the discovery cohort [5].

- Consider a Larger Sample: If the corrected effect size is much smaller, you may need to increase your replication sample size to achieve adequate power.

- Verify Ancestry Matching: Ensure the genetic ancestry of your replication cohort is similar to the discovery cohort. Differences in linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns between ancestries can cause replication failure even for true effects [5].

Table 2: Checklist for Diagnosing Replication Failure

| Checkpoint | Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Effect Size Inflation | Re-analyze discovery data with Winner's Curse correction. | [5] |

| Sample Size & Power | Re-calculate replication power using a corrected, smaller effect size. | [7] |

| Cohort Ancestry | Confirm matched ancestry between discovery and replication cohorts to ensure consistent LD. | [5] |

| Significance Threshold | Check if the discovered variant was very close to the significance cutoff in the original study. | [9] |

Problem: Designing a new association study and wanting to minimize the impact of the Winner's Curse.

Solution: Implement a rigorous two-stage design with pre-registration. The following workflow outlines a robust experimental protocol to mitigate the Winner's Curse from the outset.

Experimental Protocol for a Two-Stage Study Design:

Discovery Stage:

- Cohort: Assemble a discovery cohort with a sample size as large as possible to maximize initial power [7].

- Genotyping/Sequencing: Perform high-quality genome-wide genotyping or sequencing.

- Quality Control (QC): Apply standard QC filters to variants and samples (e.g., call rate, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, heterozygosity rate).

- Association Analysis: Conduct an association analysis for your trait of interest, correcting for population structure (e.g., using principal components).

- Variant Selection: Identify variants that pass a pre-specified, stringent genome-wide significance threshold (e.g., P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). Clump variants to select independent loci [9].

Winner's Curse Correction & Replication Planning:

- Statistical Correction: Apply a statistical correction method for the Winner's Curse to the effect sizes (e.g., beta coefficients or odds ratios) of the significant, independent loci from the discovery cohort [5].

- Power Calculation: Use these corrected effect sizes—not the original inflated ones—to calculate the required sample size for the replication study to achieve sufficient power (e.g., 80% or 90%).

Replication Stage:

- Cohort: Genotype the top associated variants in a completely independent replication cohort. This cohort must not have any sample overlap with the discovery cohort [9].

- Analysis: Perform an association analysis in the replication cohort for these specific variants.

- Replication Threshold: Define a replication significance threshold a priori, which can be a nominal threshold (e.g., P < 0.05) or a Bonferroni-corrected threshold based on the number of independent loci tested [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for Robust Genetic Association Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Importance | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Large, Well-Phenotyped Biobanks | Provides the high sample size needed for powerful discovery and replication, directly mitigating the root cause of the Winner's Curse. | Examples include UK Biobank, All of Us. Ensure phenotyping is consistent across cohorts. |

| Independent Replication Cohorts | The gold standard for validating initial discoveries. A lack of sample overlap is critical to avoid bias. | Must be genetically and phenotypically independent from the discovery set. |

| Winner's Curse Correction Software | Statistical packages that implement methods to debias initial effect size estimates. | Examples include software based on maximum likelihood estimation [5] or bootstrap methods. |

| Clumping Algorithms (for GWAS) | Identifies independent genetic signals from a set of associated variants, preventing redundant validation efforts. | Tools like PLINK's clump procedure use linkage disequilibrium (LD) measures (e.g., r²). |

| Power Calculation Software | Determines the necessary sample size to detect an effect with a given probability, preventing underpowered studies. | Tools like G*Power or custom scripts. Crucially, use corrected effect sizes as input. |

FAQs on BWAS Reproducibility

Why do many BWAS findings fail to replicate? Low replicability in BWAS has been attributed to a combination of small sample sizes, smaller-than-expected effect sizes, and problematic research practices like p-hacking and publication bias [10] [11]. Brain-behavior correlations are much smaller than previously assumed; median effect sizes (|r|) are around 0.01, and even the top 1% of associations rarely exceed |r| = 0.06 [12]. In small samples, these tiny effects are easily inflated or missed entirely due to sampling variability.

What is the primary solution to improve replicability? The most direct solution is to increase the sample size. Recent studies have demonstrated that thousands of participants—often more than 1,000 and sometimes over 4,000—are required to achieve adequate power and replicability for typical brain-behaviour associations [12] [10] [13]. For context, while a study with 25 participants has a 99% confidence interval of about ±0.52 for an effect size, making findings highly unstable, this variability decreases significantly as the sample size grows [12].

Are there other ways to improve my study besides collecting more data? Yes, optimizing study design can significantly increase standardized effect sizes and thus replicability, without requiring a larger sample size. Two key features are:

- Increasing Covariate Variability: Sampling participants to maximize the standard deviation of the variable of interest (e.g., age) can strengthen the observable effect size [10] [11].

- Using Longitudinal Designs: For variables that change within an individual (e.g., cognitive decline), longitudinal studies can yield much larger standardized effect sizes than cross-sectional studies. One meta-analysis found a 380% increase for brain volume-age associations in longitudinal designs [10] [11].

Do these reproducibility issues apply to studies of neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer's? The need for large samples is general, but the required size can vary. Studies of Alzheimer's disease often investigate more pronounced brain changes (atrophy) than studies of subtle cognitive variations in healthy populations. Therefore, robust and replicable patterns of regional atrophy have been identified with smaller sample sizes (a few hundred participants) through global consortia like ENIGMA [13]. However, for detecting subtle effects or studying rare conditions, large samples remain essential.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common BWAS Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Symptom | Underlying Cause | Solution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irreproducible Results | An association found in one sample disappears in another. | Small Sample Size (& Sampling Variability): At small n (e.g., 25), confidence intervals for effect sizes are enormous (±0.52), allowing for extreme inflation and flipping of effects by chance [12]. | Use samples of thousands of individuals for discovery. For smaller studies, collaborate through consortia (e.g., ENIGMA) for replication [12] [13]. | ||||

| Inflated Effect Sizes | Reported correlations (e.g., r > 0.2) are much larger than those found in mega-studies. | The Winner's Curse: In underpowered studies, only the most inflated effects reach statistical significance, especially with stringent p-value thresholds [12]. | Use internal replication (split-half) and report unbiased effect size estimates from large samples. Be skeptical of large effects from small studies. | ||||

| Low Statistical Power | Inability to detect true positive associations; high false-negative rate. | Tiny True Effects: With true effect sizes of | r | ≈ 0.01-0.06, small studies are severely underpowered. False-negative rates can be nearly 100% for n < 1,000 [12]. | Conduct power analyses based on realistic effect sizes ( | r | < 0.1). Use power-boosting designs like longitudinal sampling [10] [11]. |

| Conflated Within- & Between-Subject Effects | In longitudinal data, the estimated effect does not clearly separate individual differences from within-person change. | Incorrect Model Specification: Using models that assume the relationship between within-person and between-person changes are equal can reduce effect sizes and replicability [10] [11]. | Use statistical models that explicitly and separately model within-subject and between-subject effects (e.g., mixed models) [10] [11]. |

Quantitative Data on Sample Size and Effect Sizes

Table 1: Observed BWAS Effect Sizes in Large Samples (n ≈ 3,900-50,000) [12]

| Brain Metric | Behavioural Phenotype | Median | r | Maximum Replicable | r | Top 1% of Associations | r | > | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-State Functional Connectivity (RSFC) | Cognitive Ability (NIH Toolbox) | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Cortical Thickness | Psychopathology (CBCL) | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Task fMRI | Cognitive Tests | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

Table 2: Replication Rates for a Functional Connectivity-Cognition Association [12]

| Sample Size per Group | Approximate Replication Rate |

|---|---|

| n = 25 | ~5% |

| n = 500 | ~5% |

| n = 2,000 | ~25% |

Table 3: Impact of Study Design on Standardized Effect Sizes (RESI) [10] [11]

| Design Feature | Example Change | Impact on Standardized Effect Size |

|---|---|---|

| Population Variability | Increasing the standard deviation of age in a sample by 1 year. | Increases RESI by ~0.1 for brain volume-age associations. |

| Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional | Studying brain-age associations with a longitudinal design. | Longitudinal RESI = 0.39 vs. Cross-sectional RESI = 0.08 (380% increase). |

Experimental Protocols for Robust BWAS

Protocol 1: Designing a BWAS with High Replicability Potential

- Define Your Covariate of Interest: Identify the primary behavioural, cognitive, or clinical variable for association.

- Maximize Variability: Design your sampling scheme to maximize the variance of this covariate. Instead of a tight, bell-shaped distribution, consider uniform or even U-shaped sampling if scientifically justified [10] [11].

- Choose Sample Size: For a discovery BWAS, plan for a sample size in the thousands. Use power analysis software with realistic, small effect sizes (|r| < 0.1) derived from large, public datasets like the UK Biobank or ABCD [12].

- Pre-register Your Analysis Plan: Detail your hypotheses, preprocessing pipelines, and statistical models on a public registry to avoid p-hacking and data dredging.

- Plan for Internal Replication: If collecting a large single sample, pre-plan a split-half analysis, where the discovery analysis is performed on one half and the confirmatory analysis on the other [12].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Longitudinal BWAS Design

- Cohort Selection: Recruit a cohort that will exhibit change in your phenotype of interest over the study period.

- Wave Scheduling: Plan at least two, but preferably more, longitudinal follow-up scans and assessments. The timing should be informed by the expected rate of change for your phenotype and population.

- Data Collection: Acquire MRI and phenotypic data at each wave using consistent protocols and scanners to minimize technical variance.

- Statistical Modeling: Use a correctly specified model to analyze the data.

- Interpretation: Report within-person and between-person effects separately, as they may have different magnitudes and interpretations.

Visualizing the Workflow for a Robust BWAS

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for planning and executing a BWAS with enhanced reproducibility, integrating key design considerations.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Conducting Large-Scale BWAS

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Large Public Datasets | Provide pre-collected, large-scale neuroimaging and behavioural data for hypothesis generation, piloting, and effect size estimation. | UK Biobank (UKB): ~35,735 adults; structural & functional MRI [12] [13]. ABCD Study: ~11,874 children; longitudinal design [12] [10]. Human Connectome Project (HCP): ~1,200 adults; high-quality, dense phenotyping [12]. |

| ENIGMA Consortium | A global collaboration network that provides standardized protocols for meta-analysis of neuroimaging data across many diseases and populations. | Allows researchers with smaller cohorts to pool data, achieving the sample sizes necessary for robust, replicable findings [13]. |

| Robust Effect Size Index (RESI) | A standardized effect size measure that is robust to model misspecification and applicable to many model types, enabling fair comparisons across studies. | Used to quantify and compare effect sizes across different study designs (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) [10] [11]. |

| Pre-registration Platforms | Publicly document research hypotheses and analysis plans before data collection or analysis to reduce researcher degrees of freedom and publication bias. | Examples: AsPredicted, OSF. Critical for confirming that a finding is a true discovery rather than a result of data dredging. |

| Mixed-Effects Models | A class of statistical models essential for analyzing longitudinal data, as they can separately estimate within-subject and between-subject effects. | Prevents conflation of different sources of variance, leading to more accurate and interpretable effect size estimates [10] [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Effect Size Inflation in Your Dataset

Problem: Observed effect sizes in discovery research are larger than the true effect sizes, leading to problems with replicability.

Primary Cause: The Vibration of Effects (VoE)—the variability in estimated association outcomes resulting from different analytical model specifications [14]. When researchers make diverse analytical choices, the same data can produce a wide range of effect sizes.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check Study Power: Underpowered studies are a major source of effect size inflation. In underpowered studies, only effect sizes that are large enough to cross the statistical significance threshold are detected, creating a systematic bias toward inflation [1] [15].

- Assess Analytical Flexibility: Evaluate how many reasonable choices exist for model specification (e.g., selection of adjusting covariates, handling of outliers, data transformations). A large set of plausible choices increases the VoE [14].

- Quantify the Vibration Ratio: For a given association, run multiple analyses with different, justifiable model specifications. The vibration ratio is the ratio of the largest to the smallest effect size observed across these different analytical approaches [1].

Solution:

- Conduct a Vibration of Effects analysis to quantify the uncertainty. If the VoE is large, claims about the association should be made very cautiously [14].

- Use larger sample sizes in the discovery phase to reduce inflation [1].

- Pre-register your analytical plan to reduce the impact of flexible analysis and selective reporting [1].

Guide 2: Addressing Low Replication Rates

Problem: A high proportion of published statistically significant findings fail to replicate in subsequent studies.

Primary Cause: While Questionable Research Practices (QRPs) like p-hacking and selective reporting contribute, the base rate of true effects (π) in a research domain is a major, often underappreciated, factor [8]. In fields where true effects are rare, a higher proportion of the published significant findings will be false positives, naturally leading to lower replication rates.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Evaluate the Research Domain: Consider if the field is discovery-oriented (likely lower base rate of true effects) or focused on testing well-established theories (likely higher base rate) [8].

- Test for Publication Bias: Use statistical tools like the Replicability Index (RI) or Test of Excessive Significance (TES) to detect if the literature shows an excess of significant results that would be unexpected given the typical statistical power in the field [16].

- Check for p-hacking: Look for signs of analytical flexibility, such as the use of multiple dependent variables or alternative covariate sets without clear a priori justification [8].

Solution:

- Focus on effect sizes and confidence intervals rather than just binary significance testing [15].

- Place strong emphasis on independent replication before drawing firm conclusions [1].

- Be fair in the interpretation of results, acknowledging analytical choices and uncertainties [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "vibration of effects" and why should I care about it?

A: The Vibration of Effects (VoE) is the phenomenon where the estimated association between two variables changes when different but reasonable analytical models are applied to the same dataset [14]. You should care about it because a large VoE indicates that your results are highly sensitive to subjective analytical choices. This means the reported effect size might be unstable and not a reliable estimate of the true relationship. For example, one study found that 31% of variables examined showed a "Janus effect," where analyses could produce effect sizes in opposite directions based solely on model specification [14].

Q2: My underpowered pilot study found a highly significant, large effect. Is this a good thing?

A: Counterintuitively, this is often a reason for caution, not celebration. When a study has low statistical power, the only effects that cross the significance threshold are those that are, by chance, disproportionately large. This is a statistical necessity that leads to the inflation of effect sizes in underpowered studies [1] [15]. You should interpret this large effect size as a likely overestimate and plan a larger, well-powered study to obtain a more accurate estimate.

Q3: How can I quantify the uncertainty from my analytical choices?

A: You can perform a Vibration of Effects analysis. This involves:

- Defining a set of plausible adjusting variables based on the literature and subject-matter knowledge.

- Running your association analysis repeatedly using every possible combination of these adjusting variables.

- Examining the distribution of the resulting effect sizes and p-values [14].

The variance or range of this distribution quantifies your results' sensitivity to model specification. Presenting this distribution is more transparent than reporting a single effect size from one chosen model.

Q4: We've used p-hacking in our lab because "everyone does it." How much does this actually hurt replicability?

A: While QRPs like p-hacking unquestionably inflate false-positive rates and are ethically questionable, their net effect on replicability is complex. P-hacking increases the Type I error rate, which reduces replicability. However, it also increases statistical power for detecting true effects (power inflation), which increases replicability [8]. A quantitative model suggests that the base rate of true effects (π) in a research domain is a more dominant factor for determining overall replication rates [8]. In domains with a low base rate of true effects, even a small amount of p-hacking can produce a substantial proportion of false positives.

Quantitative Data on Effect Size Inflation and VoE

Table 1: Factors Contributing to Inflated Effect Sizes in Published Research

| Factor | Mechanism of Inflation | Impact on Effect Size |

|---|---|---|

| Low Statistical Power [1] [15] | In underpowered studies, only effects large enough to cross the significance threshold are detected, creating a selection bias. | Can lead to very large inflation, especially when the true effect is small or null. |

| Vibration of Effects (VoE) [1] [14] | Selective reporting of the largest effect from multiple plausible analytical models. | The "vibration ratio" (max effect/min effect) can be very large. In one study, 31% of variables showed effects in opposite directions. |

| Publication Bias (Selection for Significance) [16] | Journals and researchers preferentially publish statistically significant results, filtering out smaller, non-significant effects. | Inflates the published effect size estimate relative to the true average effect. |

| Questionable Research Practices (p-hacking) [8] | Flexible data collection and analysis until a significant result is obtained. | Inflates the effect size in the published literature, though its net effect on replicability may be secondary to the base rate. |

Table 2: Exemplary VoE Assessment on 417 Variables (NHANES Data)

This table summarizes the methodology and key results from a large-scale VoE analysis linking 417 variables to all-cause mortality [14].

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Data Source | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004 |

| Outcome | All-cause mortality |

| Analytical Method | 8,192 Cox models per variable (all combinations of 13 adjustment covariates) |

| Key Metric | Janus Effect: Presence of effect sizes in opposite directions at the 99th vs. 1st percentile of the analysis distribution. |

| Key Finding | 31% of the 417 variables exhibited a Janus effect. Example: The vitamin E variant α-tocopherol showed both higher and lower risk for mortality depending on model specification. |

| Conclusion | When VoE is large, claims for observational associations should be very cautious. |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Vibration of Effects Analysis

Objective: To empirically quantify the stability of an observed association against different analytical model specifications.

Materials:

- Dataset with the exposure, outcome, and a set of potential covariates.

- Statistical computing software (e.g., R, Python).

Methodology:

- Define the Core Association: Identify the exposure (e.g., a biomarker) and outcome (e.g., mortality) variables of interest.

- Establish the Adjustment Set: Based on prior literature and theoretical knowledge, select a set of

kpotential covariates that could plausibly be adjusted for (e.g., age, sex, BMI, smoking status, etc.). Age and sex are often included in all models as a baseline [14]. - Generate Model Specifications: Create a list of all possible combinations of the

kcovariates. The total number of models will be2^k. For example, with 13 covariates, you will run 8,192 models [14]. - Execute Models: For each model specification, run the statistical model (e.g., Cox regression, linear regression) and extract the effect size estimate (e.g., hazard ratio, beta coefficient) and its p-value for the exposure-outcome association.

- Analyze the Distribution: Collect all results and analyze the distribution of the effect sizes and p-values.

- Calculate the vibration ratio (largest effect / smallest effect).

- Plot the distribution of effect sizes to check for multimodality.

- Determine if a Janus effect exists (i.e., effect directions change).

- Report Findings: Report the entire distribution of effect sizes or key percentiles (e.g., 1st, 50th, 99th) to transparently communicate the stability of the association.

Logical Workflow: From Analytical Choices to Replicability

The diagram below visualizes the logical pathway through which analytical decisions and research practices ultimately impact the replicability of scientific findings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Robust Research

This table lists key conceptual "reagents" and their functions for diagnosing and preventing effect size inflation and replicability issues.

| Tool | Function | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Vibration of Effects (VoE) Analysis [14] | Quantifies the variability of an effect estimate under different, plausible analytical model specifications. | Observational research (epidemiology, economics, social sciences) to assess result stability. |

| Replicability Index (RI) [16] | A powerful method to detect selection for significance (publication bias) in a set of studies (e.g., a meta-analysis). | Meta-research, literature synthesis, to check if the proportion of significant results is too high. |

| Test of Excessive Significance (TES) [16] | Compares the observed discovery rate (percentage of significant results) to the expected discovery rate based on estimated power. | Meta-research to identify potential publication bias or p-hacking in a literature corpus. |

| Pre-registration [1] | The practice of publishing your research plan, hypotheses, and analysis strategy before data collection or analysis begins. | All experimental and observational research; reduces analytical flexibility and selective reporting. |

| Power Analysis [1] [15] | A calculation performed before a study to determine the sample size needed to detect an effect of a given size with a certain confidence. | Study design; helps prevent underpowered studies that are prone to effect size inflation. |

The replication crisis represents a significant challenge across multiple scientific fields, marked by the accumulation of published scientific results that other researchers are unable to reproduce [17]. This crisis is particularly acute in psychology and medicine; for example, only about 30% of results in social psychology and approximately 50% in cognitive psychology appear to be reproducible [18]. Similarly, attempts to confirm landmark studies in preclinical cancer research succeeded in only a small fraction of cases (approximately 11-20%) [18] [17]. While multiple factors contribute to this problem, one underappreciated aspect is the base rate of true effects within a research domain—the fundamental probability that a investigated effect is genuinely real before any research is conducted [18]. This technical support guide explores how this base rate problem influences replicability and provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers navigating these methodological challenges.

Understanding the Base Rate Framework

What is the Base Rate Problem?

In scientific research, the base rate (denoted as π) refers to the proportion of studied hypotheses that truly have a real effect [18]. This prevalence of true effects varies substantially across research domains. When the base rate is low, meaning true effects are rare, the relative proportion of false positives within that research domain will be high, leading to lower replication rates [18].

The relationship between base rate and replicability follows statistical necessity: when π = 0 (no true effects exist), all positive findings are false positives, while when π = 1 (all effects are true), no false positives can occur [18]. Consequently, replication rates are inherently higher when the base rate is relatively high compared to when it is low.

Domain-Specific Base Rate Estimates

Research has quantified base rates across different scientific fields, revealing substantial variation that correlates with observed replication rates:

Table 1: Estimated Base Rates and Replication Rates Across Scientific Domains

| Research Domain | Estimated Base Rate (π) | Observed Replication Rate | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Psychology | 0.09 (9%) | <30% | [18] |

| Cognitive Psychology | 0.20 (20%) | ~50% | [18] |

| Preclinical Cancer Research | Not quantified | 11-20% | [18] [17] |

| Experimental Economics | Model explains full rate | Varies | [19] |

These estimates explain why cognitive psychology demonstrates higher replicability than social psychology—the prior probability of true effects is substantially higher [18]. Similarly, discovery-oriented research (searching for new effects) typically has lower base rates than theory-testing research (testing predicted effects) [18].

Mechanisms Linking Base Rates to Replicability

Statistical Foundations

The base rate problem interacts with statistical testing through Bayes' theorem. Even with well-controlled Type I error rates (α = 0.05), when the base rate of true effects is low, most statistically significant findings will be false positives. This occurs because the proportion of true positives to false positives depends not only on α and power (1-β), but also on the prior probability of effects being true [18].

The relationship between these factors can be visualized in the following diagnostic framework:

This diagram illustrates how multiple factors, including the base rate, collectively determine replication outcomes. The base rate serves as a fundamental starting point that influences the entire research ecosystem.

Effect Size Inflation (The "Winner's Curse")

Newly discovered true associations are often inflated compared to their true effect sizes [1]. This inflation, known as the "winner's curse," occurs primarily because:

- Statistical sampling: When true discovery is claimed based on crossing a threshold of statistical significance and the discovery study is underpowered, the observed effects are expected to be inflated [1].

- Flexible analyses: Selective reporting and analytical choices can dramatically inflate published effects. The vibration ratio (the ratio of the largest vs. smallest effect on the same association approached with different analytic choices) can be very large [1].

- Interpretation biases: Effects may be further inflated at the stage of interpretation due to diverse conflicts of interest [1].

This effect size inflation creates a vicious cycle: initially promising effects appear stronger than they truly are, leading to failed replication attempts when independent researchers try to verify these inflated claims.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Research Practitioners

Diagnosis and Risk Assessment

Table 2: Diagnostic Checklist for Base Rate Problems in Research

| Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently failed replications | Low base rate domain, p-hacking | Calculate observed replication rate; Test for excess significance |

| Effect sizes diminish in subsequent studies | Winner's curse, Underpowered initial studies | Compare effect sizes across study sequences |

| Literature with contradictory findings | Low base rate, High heterogeneity | Meta-analyze existing literature; Assess between-study variance |

| "Too good to be true" results | QRPs, Selective reporting | Test for p-hacking using p-curve analysis |

Q1: How can I estimate the base rate in my research field?

A1: Base rates can be estimated through several approaches:

- Analyze results from systematic replication initiatives in your field [18]

- Use prediction markets where researchers bet on replicability of findings [18]

- Employ statistical models that estimate the false discovery rate from patterns of published p-values [19]

- Conduct meta-scientific analyses of multi-experiment papers for signs of "too good to be true" results [18]

Q2: What specific methodological practices exacerbate the base rate problem?

A2: Several questionable research practices (QRPs) significantly worsen the impact of low base rates:

- p-hacking: Exploiting researcher degrees of freedom to achieve statistical significance [18]

- Selective reporting: Conducting multiple studies but only reporting those with significant results (file drawer problem) [18]

- Multiple testing without correction: Measuring multiple dependent variables and reporting only significant ones [18]

- Data peeking: Repeatedly testing data during collection and stopping when significance is achieved [18]

Mitigation Strategies and Methodological Solutions

Q3: What practical steps can I take to minimize false positives in low-base-rate environments?

A3: Implement these evidence-based practices:

- Increase sample sizes: Conduct high-powered studies with sample sizes determined through proper power analysis [18] [19]

- Use stricter significance thresholds: In exploratory research, consider lowering α to 0.005 or using false discovery rate controls [18]

- Pre-register studies: Submit hypotheses, methods, and analysis plans before data collection [17]

- Adopt blind analysis: Finalize analytical approaches before seeing the outcome data [1]

- Pursive direct replications: Verify findings through exact replication before building theories [17]

Q4: How should I approach sample size determination for replication studies?

A4: Traditional approaches to setting replication sample sizes often lead to systematically lower replication rates than intended because they treat estimated effect sizes from original studies as fixed true effects [19]. Instead:

- Account for the fact that original effect sizes are estimates that may be inflated [19]

- Use bias-corrected effect size estimates when determining sample needs [1]

- Consider sequential designs that allow for sample size adjustment based on accumulating data [19]

- For rare-variant association analyses, ensure consistent variant-calling pipelines between cases and controls [20]

The following troubleshooting workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and addressing replication failures:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Addressing Base Rate Problems

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function/Purpose | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Pre-registration platforms | Reduces questionable research practices (QRPs) | [17] |

| Statistical Analysis | p-curve analysis | Detects selective reporting and p-hacking | [18] |

| Power Analysis | Bias-corrected power calculators | Accounts for effect size inflation in replication studies | [19] |

| Data Processing | Standardized variant-calling pipelines | Reduces false positives in genetic association studies | [20] |

| Meta-Science | Replication prediction markets | Estimates prior probabilities for research hypotheses | [18] |

The base rate problem represents a fundamental challenge to research replicability, particularly in fields where true effects are genuinely rare. While methodological reforms like pre-registration and open science address some symptoms, the underlying mathematical reality remains: when searching for rare effects, most statistically significant findings will be false positives [18]. This does not mean such research domains are unscientific, but rather that they require more stringent standards, larger samples, and greater skepticism toward initial findings [18] [1].

Moving forward, the research community should:

- Develop field-specific base rate estimates to inform research practice [18]

- Prioritize large-scale collaborative studies over small, underpowered studies [1]

- Reward replication efforts and null results to combat publication bias [17]

- Utilize emerging technologies like cloud-based computing to enable consistent analytical pipelines [20]

By acknowledging and directly addressing the base rate problem, researchers across scientific domains can develop more robust, reliable research programs that withstand the test of replication.

Building Robustness: Methodological Solutions for Reliable Discovery

Why are my initial discovered associations often stronger than what is found in follow-up studies?

This phenomenon, known as effect size inflation, is a common challenge in research, particularly when discovery phases use small sample sizes. When a study is underpowered and a discovery is claimed based on crossing a threshold of statistical significance, the observed effects are expected to be inflated compared to the true effect size [1]. This is a manifestation of the "winner's curse." Furthermore, flexible data analysis approaches combined with selective reporting can further inflate the published effect sizes; the ratio between the largest and smallest effect for the same association approached with different analytical choices (the vibration ratio) can be very large [1].

Solution: To mitigate this, employ a multi-phase design with a distinct discovery cohort followed by a replication study in an independent sample [21]. Using a large sample size even in the discovery phase, as achieved through large international consortia, also helps reduce this bias [21].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

The Problem: Low Replicability of Findings Across Independent Studies

Diagnosis and Solution: This often stems from a combination of small discovery sample sizes, lack of standardized protocols, and undisclosed flexibility in analytical choices. The solution involves a concerted effort to enhance Data Reproducibility, Analysis Reproducibility, and Result Replicability [21].

| Challenge | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inflated effect sizes in discovery phase | Underpowered studies; "winner's curse" [1] | Use large-scale samples from inception; employ multi-phase design with explicit replication [21] |

| Batch or center effects in genotype or imaging data | Non-random allocation of samples across processing batches or sites [21] | Balance cases/controls and ethnicities across batches; use joint calling and rigorous QC [21] |

| Phenotype heterogeneity | Inconsistent or inaccurate definition of disease/trait outcomes across cohorts [21] | Adopt community standards (e.g., phecode for EHR data); implement phenotype harmonization protocols [21] |

| Inconsistent analysis outputs | Use of idiosyncratic, non-standardized analysis pipelines by different researchers [21] | Use field-standardized, open-source analysis software and protocols (e.g., Hail for genomic analysis) [21] [22] |

| Difficulty in data/resource sharing | Lack of infrastructure and mandates for sharing [21] | Utilize supported data repositories (e.g., GWAS Catalog); adhere to journal/funder data sharing policies [21] |

The Problem: How to Manage and Analyze Genomic Data at a Biobank Scale

Diagnosis and Solution: Researchers, especially early-career ones, can be overwhelmed by the computational scale and cost. The solution is to use scalable, cloud-based computing frameworks and structured tutorials [22].

| Challenge | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Intimidated by large-scale genomic data | Lack of prior experience with biobank-scale datasets and cloud computing [22] | Utilize structured training resources and hands-on boot camps (e.g., All of Us Biomedical Researcher Scholars Program) [22] |

| High cloud computing costs | Inefficient use of cloud resources and analysis strategies [22] | Employ cost-effective, scalable libraries like Hail on cloud-based platforms (e.g., All of Us Researcher Workbench) [22] |

| Ensuring analysis reproducibility | Manual, non-documented analytical steps [21] | Conduct analyses in Jupyter Notebooks which integrate code, results, and documentation for seamless sharing and reproducibility [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Large-Scale Studies

Protocol 1: Conducting a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) in the Cloud

This protocol is adapted from the genomics tutorial used in the All of Us Researcher Workbench training [22].

1. Data Preparation and Quality Control (QC):

- Dataset: Load genomic data (e.g., v.5 or v.7 of the All of Us controlled tier) into the cloud environment.

- QC Steps: Perform rigorous QC on both samples and genetic variants.

- Sample QC: Filter out individuals with high missingness, sex discrepancies, or extreme heterozygosity.

- Variant QC: Filter out variants with low call rate, significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, or low minor allele frequency.

- Population Structure: Address population stratification by calculating principal components (PCs) and including them as covariates in the association model.

2. Association Testing:

- Model: Use a linear or logistic regression model, depending on the trait (quantitative or case-control).

- Covariates: Include age, sex, genotyping platform, and top principal components to control for confounding.

- Computation: Use the Hail library's

hl.linear_regressionorhl.logistic_regressionmethods to run the association tests across the genome in a distributed, scalable manner [22].

3. Result Interpretation:

- Significance Threshold: Apply a stringent, genome-wide significance level (e.g., ( p < 5 \times 10^{-8} )) to account for multiple testing [21].

- Visualization: Generate a Manhattan plot to visualize association p-values across chromosomes and a QQ-plot to assess inflation of test statistics.

- Replication Plan: Top association signals should be taken forward for replication in an independent cohort [21].

Protocol 2: Standardized Meta-Analysis of Neuroimaging Data Across Sites

This protocol follows the model established by the ENIGMA Consortium [23] [24].

1. Pipeline Harmonization:

- Standardization: All participating sites use the same, harmonized image processing protocols to extract brain metrics (e.g., cortical thickness, subcortical volume) from raw MRI scans.

- Software: Utilize widely adopted, standardized software tools (e.g., FreeSurfer, FSL).

2. Distributed Analysis:

- Local Analysis: Each site processes its own data locally using the consortium's script to generate summary statistics for the association of interest.

- Quality Control: A central team checks all output files for quality and outliers.

3. Meta-Analysis:

- Aggregation: The coordinating center aggregates the summary statistics from all sites.

- Effect Size Estimation: Meta-analysis is performed to estimate the pooled effect size and its precision for each brain-behavior or brain-genetic association.

- Mega-Analysis Alternative: Where possible, anonymized individual-level data are aggregated for a pooled "mega-analysis," allowing for more sophisticated statistical modeling [24].

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Hail Library | An open-source, scalable Python library for genomic data analysis. It is essential for performing GWAS and other genetic analyses on biobank-scale datasets in a cloud environment [22]. |

| Jupyter Notebooks | An interactive, open-source computing environment that allows researchers to combine code execution (e.g., in Python or R), rich text, and visualizations. It is critical for documenting, sharing, and ensuring the reproducibility of analytical workflows [22]. |

| GWAS Catalog | A curated repository of summary statistics from published GWAS. It is a vital resource for comparing new findings with established associations and for facilitating data sharing as mandated by many funding agencies [21]. |

| ENIGMA Protocols | A set of standardized and harmonized image processing and analysis protocols for neuroimaging data. They enable large-scale, multi-site meta- and mega-analyses by ensuring consistency across international cohorts [23] [24]. |

| Phecode Map | A system that aggregates ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes into clinically meaningful phenotypes for use in research with Electronic Health Records (EHR). It is crucial for standardizing and harmonizing phenotype data across different healthcare systems [21]. |

| Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) Standards | International standards and frameworks for the responsible sharing of genomic and health-related data. They provide the foundational principles and technical standards for large-scale data exchange and collaboration [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is a 'Union Signature' and how does it improve upon traditional brain measures? A Union Signature is a data-driven brain biomarker derived from the spatial overlap (or union) of multiple, domain-specific brain signatures [25]. It is designed to be a multipurpose tool that generalizes across different cognitive domains and clinical outcomes. Research has demonstrated that a Union Signature has stronger associations with episodic memory, executive function, and clinical dementia ratings than standard measures like hippocampal volume. Its ability to classify clinical syndromes (e.g., normal, mild cognitive impairment, dementia) also exceeds that of these traditional measures [25].

Q2: Why is it critical to use separate cohorts for discovery and validation? Using independent cohorts for discovery and validation is a fundamental principle for ensuring the robustness and generalizability of a data-driven signature [25]. This process helps confirm that the discovered brain-behavior relationships are not specific to the sample they were derived from (overfitted) but are reproducible and applicable to new, unseen populations. This step is essential for building reliable biomarkers that can be used in clinical research and practice [25].

Q3: What is a key consideration when building an unbiased reference standard for evaluation? A key consideration is to make the reference standard method-agnostic. This means the standard should be derived from a consensus of analytical methods that are distinct from the discovery method being evaluated [26]. Using the same method for both discovery and building the reference standard can replicate and confound methodological biases with authentic biological signals, leading to overly optimistic and inaccurate performance measures [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The discovered brain signature does not generalize well to the independent validation cohort.

- Potential Cause 1: Overfitting to the discovery cohort.

- Solution: Implement rigorous internal validation during the discovery phase. The signature should be derived using multiple, random subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of 400 samples) from the discovery cohort, with a consensus region (e.g., voxels present in at least 70% of the subsets) being defined for the final signature [25].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate statistical power or demographic mismatch between cohorts.

- Solution: Ensure the discovery cohort is sufficiently large and, if possible, demographically diverse. When collecting the validation cohort, strive for a sample size that is larger than the discovery set and ensure it includes a mix of cognitive normal, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia participants to test the signature's classification power robustly [25].

Problem: Low concordance between different analytical methods when building a consensus.

- Potential Cause: High statistical noise and discordance inherent in comparing methods with different distributional assumptions (e.g., binomial vs. negative binomial).

- Solution: Apply optimization techniques such as thresholding effect-size and expression-level filtering. For example, one study achieved a 65% increase in concordance between methods by strategically applying these filters to reduce the greatest discordances [26].

Problem: Uncertainty in interpreting the practical utility of the signature's association with clinical outcomes.

- Potential Cause: Lack of comparison to established benchmarks.

- Solution: Always benchmark the performance of your new data-driven signature against standard, clinically accepted measures. Compare the strength of your signature's associations with cognitive scores and its power to classify clinical syndromes against measures like hippocampal volume or cortical gray matter to demonstrate added value [25].

Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Cohort Details for Signature Discovery and Validation

| Cohort Name | Primary Use | Participant Count | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADNI 3 [25] | Discovery | 815 | Used for initial derivation of domain-specific GM signatures. |

| UC Davis (UCD) Sample [25] | Validation | 1,874 | A racially/ethnically diverse combined cohort; included 946 cognitively normal, 418 with MCI, and 140 with dementia. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters from Validated Studies

| Parameter | Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Subsets [25] | 40 randomly selected subsets of 400 samples from the discovery cohort. | Used to compute significant regions, ensuring robustness. |

| Consensus Threshold [25] | Voxels present in at least 70% of discovery sets. | Defines the final signature region, improving generalizability. |

| Effect-Size Thresholding [26] | Applying a Fold Change (FC) range filter to results. | Optimizes consensus between methods and reduces biased results. |

| Expression-Level Cutoff [26] | Filtering out gene products with low expression counts. | Increases concordance between different analytical methods. |

Detailed Methodology: Deriving and Validating a Gray Matter Union Signature

Signature Discovery:

- Data Preparation: Process T1-weighted MRI scans from the discovery cohort. This includes affine and nonlinear B-spline registration to a common template space, followed by segmentation into gray matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Native GM thickness maps are then deformed into the common template space [25].

- Domain-Specific Signature Derivation: For each cognitive domain (e.g., episodic memory, executive function), use a computational algorithm on the discovery cohort. The algorithm is run on multiple random subsets to identify GM regions where thickness is significantly associated with the behavioral outcome [25].

- Consolidation: Identify the consensus region across all discovery subsets by selecting voxels that appear in a high percentage (e.g., 70%) of them. This creates a robust signature for each domain [25].

- Union Signature Creation: Spatially combine the regions from multiple domain-specific signatures (e.g., memory and executive function) to create a single "Union Signature" [25].

Signature Validation:

- Independent Testing: Apply the derived Union Signature to a completely separate, validation cohort. Extract the mean GM thickness within the signature region for each participant [25].

- Association Testing: Statistically test the relationship between the signature value and relevant clinical outcomes (e.g., cognitive test scores, CDR-Sum of Boxes) in the validation cohort. Compare the strength of these associations to those of traditional brain measures [25].

- Classification Accuracy: Evaluate the signature's ability to classify participants into diagnostic groups (e.g., Cognitively Normal, MCI, Dementia) using metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC) and compare its performance to benchmarks [25].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Workflow for deriving and validating a Union Signature from multiple discovery subsets.

Figure 2: Process for creating an unbiased reference standard to evaluate a single method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| T1-Weighted MRI Scans | High-resolution structural images used to quantify brain gray matter morphology (thickness, volume) [25]. |

| Common Template Space (MDT) | An age-appropriate, minimal deformation synthetic template. Allows for spatial normalization of all individual brain scans, enabling voxel-wise group analysis [25]. |

| Cognitive & Functional Assessments | Validated neuropsychological tests (e.g., SENAS, ADNI-Mem/EF) and informant-rated scales (Everyday Cognition - ECog) to measure domain-specific cognitive performance [25]. |

| Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) | A clinician-rated scale used to stage global dementia severity. The Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) provides a continuous measure of clinical status [25]. |

referenceNof1 R Package |

An open-source software tool designed to facilitate the construction of robust, method-agnostic reference standards for evaluating single-subject 'omics' analyses [26]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Preregistration and Pre-Registered Analyses

Understanding the Problem

Q: I am unsure if my research plan is detailed enough for a valid preregistration. What are the essential components I must include?

A preregistration is a time-stamped, specific research plan submitted to a registry before you begin your study [27]. To be effective, it must clearly distinguish your confirmatory (planned) analyses from any exploratory (unplanned) analyses you may conduct later [27]. A well-structured preregistration creates a firm foundation for your research, improving the credibility of your results by preventing analytical flexibility and reducing false positives [27].

Ask the right questions of your research plan [28]:

- What is my primary hypothesis?

- What is my exact sample size and how was it determined?

- What are my specific inclusion/exclusion criteria?

- Which variables are my key dependent and independent variables?

- What is my precise statistical model and analysis plan, including how I will handle outliers?

Gather information from your experimental design. Reproduce the issue by writing out your plan in extreme detail as if you were explaining it to a colleague who will conduct the analysis for you [27].

Q: My data collection is complete, but I did not preregister. Can I create a pre-analysis plan now?

Perhaps, but the confirmatory value is significantly reduced. A core goal of a pre-analysis plan is to avoid analysis decisions that are contingent on the observed results [27]. The credibility of a preregistration is highest when created before any data exists or has been observed.

- Isolate the issue: Determine your exact point in the research workflow [27]:

- Prior to analysis: If the data exists but you have not analyzed it related to your research question, you may still preregister. You must certify that you have not analyzed the data and justify how any prior knowledge of the data does not compromise the confirmatory nature of your plan [27].

- After preliminary analysis: If you have already explored the data, any "preregistration" cannot be considered a true confirmatory analysis for the explored hypotheses. In this case, the explored analyses should be clearly reported as exploratory and hypothesis-generating [27].

Isolating the Issue

Q: I have discovered an intriguing unexpected finding in my data. Does my preregistration prevent me from investigating it?

No. Preregistration helps you distinguish between confirmatory and exploratory analyses; it does not prohibit exploration [27]. Exploratory research is crucial for discovery and hypothesis generation [27].

- Remove complexity: Adhere to your preregistered plan for your primary confirmatory tests. Then, clearly label and report any unplanned analyses as "exploratory," "post-hoc," or "hypothesis-generating" [27].

- Change one thing at a time: When reporting results, transparently disclose any deviations from your preregistered plan. Using a "Transparent Changes" document is a best practice to explain the rationale for these deviations [27].

Q: I need to make a change to my preregistration after I have started the study. What is the correct protocol?

It is expected that studies may evolve. The key is to handle changes transparently [27].

- If the registration is less than 48 hours old and not yet finalized, you can cancel it and create a new one [27].

- If changes occur after the registration is finalized:

- Option 1 (Serious error or pre-data collection): Create a new preregistration with the updated information, withdraw the original, and provide a note explaining the rationale and linking to the new plan [27].

- Option 2 (Post-data collection, most common): Start a "Transparent Changes" document. Upload this to your project and refer to it when writing up your results to clearly explain what changed and why [27].

Finding a Fix or Workaround

Q: I am in the early, exploratory phases of my research and cannot specify a precise hypothesis yet. How can I incorporate rigor now?

You can use a "split-sample" approach to maintain rigor even in exploratory research [27].

- Test it out: Randomly split your incoming data into two parts. Use one part for exploration, model building, and finding unexpected trends. Then, take the most tantalizing findings from this exploration, formally preregister a specific hypothesis and analysis plan, and confirm it using the second, held-out portion of the data [27]. This process is analogous to model training and validation.

Q: My field often produces inflated effect sizes in initial, small discovery studies. How can preregistration and transparent practices address this?

Inflation of effect sizes in initial discoveries is a well-documented problem, often arising from underpowered studies, analytical flexibility, and selective reporting [1]. Preregistration is a key defense against this.

- The Problem: Newly discovered true associations are often inflated compared to their true effect sizes. This can occur when discovery claims are based on crossing a threshold of statistical significance in underpowered studies, or from flexible analyses coupled with selective reporting [1].

- The Solution:

- Preregistration: By committing to an analysis plan upfront, you eliminate the vibration of effect sizes that comes from trying different analytical choices [1].

- Large-Scale Replication: Conducting large studies in the discovery phase, rather than small, underpowered ones, reduces the likelihood of inflation [1].

- Complete Reporting: Reporting all results from pre-analysis plans, not just the significant ones, prevents selective interpretation and gives a true picture of the evidence [27] [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the difference between exploratory and confirmatory research?

| Research Type | Goal | Standards | Data Dependence | Diagnostic Value of P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmatory | Rigorously test a pre-specified hypothesis [27] | Highest; minimizes false positives [27] | Data-independent [27] | Retains diagnostic value [27] |

| Exploratory | Generate new hypotheses; discover unexpected effects [27] | Results deserve replication; minimizes false negatives [27] | Data-dependent [27] | Loses diagnostic value [27] |

Q: Do I have to report all the results from my preregistered plan, even the non-significant ones? Yes. Selective reporting of only the significant analyses from your plan undermines the central aim of preregistration, which is to retain the validity of statistical inferences. It can be misleading, as a few significant results out of many planned tests could be false positives [27].

Q: Can I use a pre-existing dataset for a preregistered study? It is possible but comes with significant caveats. The preregistration must occur before you analyze the data for your specific research question. The table below outlines the eligibility criteria based on your interaction with the data [27]:

| Data Status | Eligibility & Requirements |

|---|---|

| Data not yet collected | Eligible. You must certify the data does not exist [27]. |

| Data exists, not yet observed (e.g., unmeasured museum specimens) | Eligible. You must certify data is unobserved and explain how [27]. |

| Data exists, you have not accessed it (e.g., data held by another institution) | Eligible with justification. You must certify no access, explain who has access, and justify how confirmatory nature is preserved [27]. |

| Data exists and has been accessed, but not analyzed for this plan (e.g., a large dataset for multiple studies) | Eligible with strong justification. You must certify no related analysis and justify how prior knowledge doesn't compromise the confirmatory plan [27]. |

Q: How does transparency in methods reporting improve reproducibility? Failure to replicate findings often stems from incomplete reporting of methods, materials, and statistical approaches [29]. Transparent reporting provides the information required for other researchers to repeat protocols and methods accurately, which is the foundation of results reproducibility [29]. Neglecting the methods section is a major barrier to replicability [29].

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Preregistration Workflow for a New Study

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and path for creating a preregistration for a new experimental study.

Split-Sample Validation Workflow

For research in its early, exploratory phases, a split-sample workflow provides a rigorous method for generating and testing hypotheses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components of a rigorous research workflow, framing them as essential "reagents" for reproducible science.

| Item / Solution | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Preregistration Template (e.g., from OSF) | Provides a structured form to specify the research plan, including hypotheses, sample size, exclusion criteria, and analysis plan, before the study begins [27]. |

| Registered Report | A publishing format where peer review of the introduction and methods occurs before data collection. This mitigates publication bias against null results and ensures the methodology is sound [27]. |

| Transparent Changes Document | A living document used to track and explain any deviations from the original preregistered plan, ensuring full transparency in the research process [27]. |

| Split-Sample Protocol | A methodological approach that uses one portion of data for hypothesis generation and a separate, held-out portion for confirmatory hypothesis testing, building rigor into exploratory research [27]. |

| Open Science Framework (OSF) | A free, open-source web platform that facilitates project management, collaboration, data sharing, and provides an integrated registry for preregistrations [27]. |

This guide addresses common technical challenges when choosing between univariate and multivariate methods in scientific research, particularly within life sciences and drug development. A key challenge in this field is that newly discovered true associations often have inflated effects compared to their true effect sizes, especially when discoveries are made in underpowered studies or through flexible analyses with selective reporting [1]. The following FAQs and protocols are framed within the broader context of improving replicability in research using small discovery sets.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between univariate and multivariate analysis?