Unraveling Motion Artifacts in fMRI: From Cognitive Task Interference to Advanced Correction Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the causes and consequences of motion artifacts in task-based fMRI, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals.

Unraveling Motion Artifacts in fMRI: From Cognitive Task Interference to Advanced Correction Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the causes and consequences of motion artifacts in task-based fMRI, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational mechanisms by which head movement corrupts BOLD signals and confounds brain-behavior associations. The scope extends to methodological advances in both prospective and retrospective correction, including real-time tracking and denoising algorithms like RETROICOR. We detail practical troubleshooting and optimization protocols for mitigating spurious findings, and conclude with validation frameworks and comparative analyses of correction efficacy. This resource is designed to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance the reliability and clinical relevance of their fMRI investigations.

The Root of the Problem: How Head Motion Systematically Corrupts fMRI Signals and Spurious Brain-Behavior Associations

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized cognitive neuroscience by enabling non-invasive visualization of brain activity. However, the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal changes of interest are remarkably small, typically just a few percent or less, making them exceptionally vulnerable to contamination by noise sources. Among these, head motion constitutes the most significant source of artifact and signal variance, systematically biasing functional connectivity estimates and threatening the validity of neuroimaging research. This technical review examines the physical origins of motion-induced artifacts, quantifies their disproportionate impact on fMRI signal variance, details the mechanisms through which they corrupt functional connectivity measures, and evaluates current methodological approaches for mitigation. Within the context of cognitive tasks research, understanding and addressing motion artifacts is paramount, particularly as certain populations—including children, older adults, and individuals with neurological or psychiatric conditions—exhibit greater in-scanner movement, potentially creating spurious group differences that mimic neuronal effects.

The Fundamental Challenge: Physical Origins of Motion Artifacts

The Nature of fMRI Data Acquisition

Spatial encoding in MRI is an intrinsically slow and sequential process. Unlike photography, which acquires data directly in image space, MRI data collection occurs in frequency or Fourier space, commonly termed k-space. Each sample in k-space contains global information about the entire image; a change in a single k-space sample affects the entire image, and conversely, a signal change in a single pixel affects all k-space samples [1]. The most common clinical approach uses Cartesian sampling, which collects data on a rectilinear k-space grid. The specific order in which these grid points are visited—the k-space trajectory—fundamentally determines the appearance of motion artifacts [1].

Mechanisms of Motion-Induced Signal Corruption

Head motion during the prolonged acquisition of k-space data violates the core assumption of a stationary object, leading to inconsistencies in the collected data. The interaction between motion type and k-space sampling order produces characteristic artifacts:

- Ghosting: Partial or complete replication of moving structures along the phase-encoding dimension. Periodic motion synchronized with k-space acquisition produces coherent ghosts, while non-periodic motion creates incoherent ghosting, appearing as multiple overlapped replicas or stripes [1].

- Blurring: The loss of sharp edges and contrast details, analogous to photography of a moving subject [1].

- Signal Loss: Caused by spin dephasing or undesired magnetization evolution within the pulse sequence, particularly problematic in diffusion-weighted imaging [1].

- Spin History Effects: When a voxel moves in or out of a region that has been recently excited by an RF pulse, the local magnetization is altered, creating signal changes that are unrelated to the BOLD effect [2].

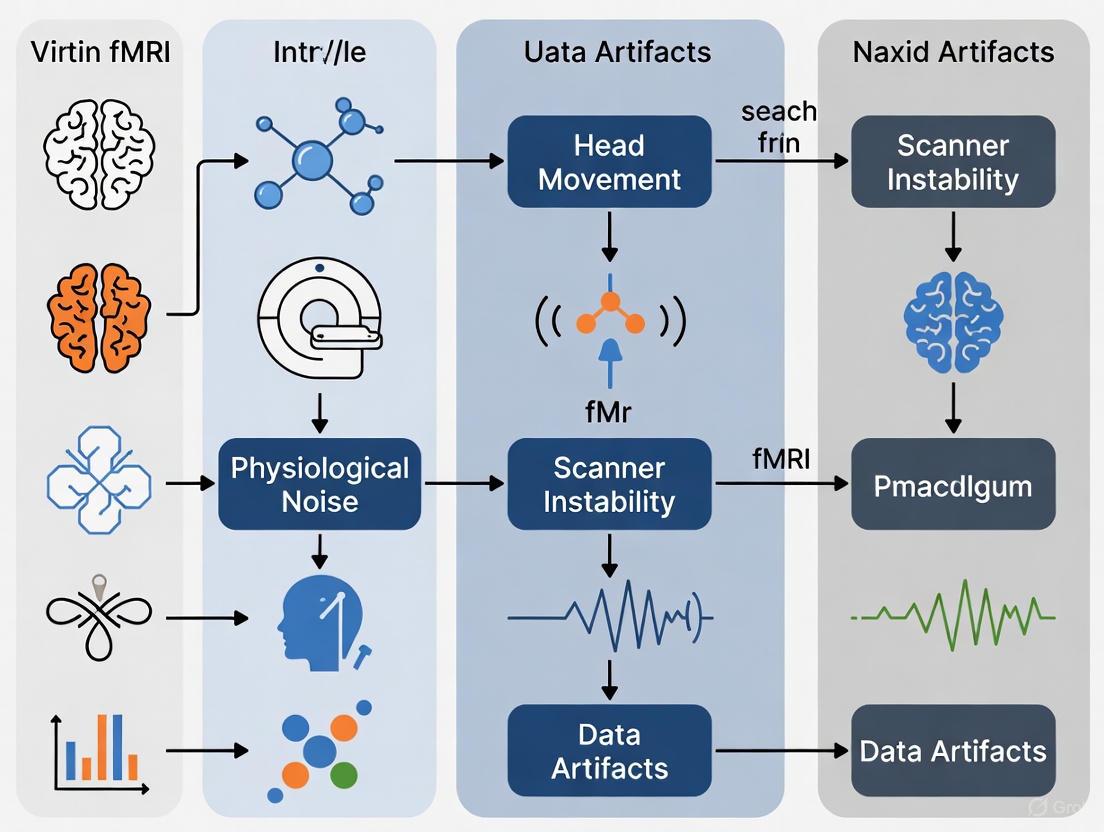

Diagram 1: Causal pathway from head motion to fMRI image artifacts, illustrating the key physical mechanisms involved.

Quantitative Evidence: Establishing Motion as the Dominant Variance Source

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that head motion accounts for the largest proportion of variance in fMRI signals, dwarfing the contribution of the BOLD signal of interest.

Magnitude of Motion-Related Variance

A 2025 analysis of the large-scale Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study quantified this relationship directly. After minimal processing (motion-correction by frame realignment only), head motion explained a remarkable 73% of the signal variance in the fMRI timeseries. Application of the standard ABCD-BIDS denoising pipeline—which includes global signal regression, respiratory filtering, motion timeseries regression, and despiking—reduced this figure to 23%. While this represents a substantial relative reduction of 69%, motion remains a dominant noise source, as nearly a quarter of the signal variance is still attributable to head movement after aggressive denoising [3].

Systematic Effects on Functional Connectivity

Head motion does not introduce random noise; it systematically biases estimates of functional connectivity (FC). Van Dijk et al. (2012) demonstrated that even sub-millimeter motions (0.1-0.2 mm) significantly distort FC estimates [4]. The effects are spatially specific and predictable:

- Decreased Long-Distance Connectivity: Coupling among distributed regions of association cortex, particularly within the default network and frontoparietal control network, is disproportionately reduced by motion [4] [3].

- Increased Short-Distance Connectivity: Motion artifact inflates estimates of local functional coupling [4].

- Direction-Specific Effects: Connectivity is decreased along the anterior-posterior axis but increased in medial-lateral regions, creating a distinctive spatial signature that can be mistaken for neuronal effects [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Head Motion on fMRI Signal and Connectivity

| Metric | Effect Size or Proportion | Context/Measurement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Variance Explained | 73% | After minimal processing (realignment only) | [3] |

| Signal Variance Explained | 23% | After comprehensive denoising (ABCD-BIDS pipeline) | [3] |

| FC Reduction (Default Network) | Significant decrease | Per 1 mm framewise displacement (FD) | [4] |

| FC Increase (Local Coupling) | Significant increase | Per 1 mm framewise displacement (FD) | [4] |

| Motion-FC vs. Average FC Correlation | Spearman ρ = -0.58 | Correlation between motion-FC effect matrix and average FC matrix | [3] |

Motion as a Confound in Group Differences

The systematic nature of motion artifacts is particularly problematic when comparing groups that inherently differ in their ability to remain still. Children move more than adults, older adults more than younger adults, and patient populations (e.g., those with ADHD, autism, or neurodegenerative diseases) more than healthy controls [4] [6] [7]. For instance, a study of healthy older adults found that greater head motion was significantly associated with poorer performance on cognitive tasks of inhibition and cognitive flexibility [7]. Systematically excluding "high-movers" from analyses may therefore bias samples by removing older adults with lower executive functioning, potentially skewing the understanding of brain-behavior relationships in aging populations [7].

Methodological Approaches: From Quantification to Correction

Measuring Head Motion

The first step in managing motion is its quantification. The most common metric is Framewise Displacement (FD), which summarizes the total translational and rotational movement of the head from one volume to the next [4] [3]. Studies often define a threshold (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) to flag "invalid" volumes for censoring (scrubbing) [3].

Retrospective Correction Methods

A multitude of post-processing methods exist to mitigate motion artifacts retrospectively. These are often applied in combination:

- Realignment: Rigid-body correction is a standard preprocessing step that aligns all volumes in a timeseries to a reference volume [4]. However, it cannot correct for spin history effects or non-rigid body movements [1].

- Regression of Motion Parameters: The six rigid-body motion parameters (three translations, three rotations) and their temporal derivatives are regressed out of the fMRI signal at each voxel [4] [3].

- Motion Censoring (Scrubbing): High-motion volumes identified by FD thresholds are removed from analysis, and the remaining data are concatenated or interpolated [3] [5].

- Global Signal Regression (GSR): Regressing out the average signal from the entire brain can help remove spatially coherent noise, including motion-related variance, but remains controversial due to its potential to introduce artifactual anti-correlations [3] [2].

- Physiological Noise Modeling: Methods like RETROICOR use external monitoring (e.g., pulse oximeter, respirometer) to model and remove cardiac and respiratory fluctuations, which can be exacerbated by motion [8] [2].

- Advanced Denoising Pipelines: Combinations of the above methods, such as the ABCD-BIDS pipeline, are becoming standard. These may also include component-based noise correction (CompCor), ICA-based artifact removal, and spectral filtering [3].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Motion Correction in fMRI Research

| Method Category | Key Protocols/Methods | Brief Principle | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective Correction | Volumetric navigators (vNavs), FID navigators, Optical tracking | Measures and corrects for head position in real-time during scan acquisition. | Not universally available; can reduce sequence efficiency. |

| Real-Time Correction | Prospective Motion Correction (PROMO) | Updates the imaging volume in real-time based on estimated head position. | Complexity of implementation. |

| Post-Processing Regression | 24-parameter model (6 motion params + derivatives + squares), GSR | Models motion as a nuisance regressor in a general linear model (GLM). | Incomplete removal; GSR may distort neural correlations. |

| Data Censoring | "Scrubbing" (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm) | Removes high-motion volumes from the analysis. | Reduces temporal degrees of freedom; may bias sample if high-movers are excluded entirely. |

| Physiological Correction | RETROICOR, RVHRCOR | Models periodic noise from cardiac and respiration cycles, often requiring external monitoring. | Requires additional hardware; ineffective for non-periodic motion. |

| Novel Acquisition | Multi-echo fMRI, Inverse Imaging (InI) | Acquires data at multiple TEs to separate BOLD from non-BOLD signals, or uses high-speed acquisition to avoid aliasing. | InI has lower spatial resolution; multi-echo requires specialized sequences. |

Diagram 2: A typical workflow for retrospective motion artifact correction in fMRI studies, showing the sequential application of common processing steps.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for fMRI Motion Artifact Investigation

| Tool/Resource | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | A scalar summary metric of volume-to-volume head movement. | Primary quantitative measure for identifying motion-corrupted timepoints and excluding participants based on mean FD [4] [3]. |

| ABCD-BIDS Pipeline | A standardized, comprehensive fMRI denoising pipeline. | Used in large-scale studies (e.g., ABCD Study) to ensure reproducible motion correction, incorporating GSR, respiratory filtering, and despiking [3]. |

| SHAMAN | Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks; calculates a trait-specific motion impact score. | Determines if a specific brain-behavior relationship is confounded by motion, distinguishing over- from underestimation of effects [3]. |

| Connectome-based Predictive Modeling (CPM) | A machine learning approach that uses functional connectivity to predict behavior or states. | Used to predict an individual's in-scanner head motion from their functional connectivity patterns, revealing associated networks like the DMN and cerebellum [6]. |

| RETROICOR | Retrospective Image-based Correction for physiological motion. | Models and removes signal components related to cardiac and respiratory cycles, which are significant noise sources at high fields [8] [2]. |

| High-Speed Acquisition (InI) | Inverse Imaging achieves very high temporal resolution by minimizing k-space traversal. | Allows sampling rates high enough to satisfy the Nyquist criterion for cardiac/respiratory noise, enabling effective removal via simple temporal filtering [8]. |

| Prospective Motion Correction (PROMO) | Real-time tracking and updating of the scan plane to account for head motion. | Actively corrects for motion during data acquisition, reducing the burden of post-processing and the severity of residual artifacts [5]. |

Head motion is unequivocally the largest source of artifact and signal variance in fMRI. Its primacy stems from the fundamental physics of MR signal acquisition and the small amplitude of BOLD signals of interest. The problem is exacerbated because motion artifact is not random noise but introduces systematic, spatially specific biases in functional connectivity that can mimic genuine neurobiological effects, particularly threatening the validity of studies comparing groups with different motion profiles. While a sophisticated toolbox of retrospective correction methods has been developed, achieving a relative reduction of motion-related variance by nearly 70%, residual artifacts persist. The future of robust fMRI research, especially in clinical and developmental populations, depends on a multi-faceted strategy: adopting standardized denoising pipelines, developing and using trait-specific motion impact assessments like SHAMAN, transparently reporting motion metrics, and advancing real-time prospective correction technologies. For researchers using fMRI to study cognitive tasks, rigorous motion management is not merely a preprocessing step but a fundamental prerequisite for valid scientific inference.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized our understanding of brain function by enabling non-invasive measurement of neural activity through the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal. However, this powerful neuroimaging technique faces a fundamental physical challenge: its exquisite sensitivity to subject motion. Even submillimeter movements can induce spurious variance in the BOLD signal, creating systematic biases that can compromise the validity of functional connectivity (FC) findings and brain-behavior associations [9] [3]. The core physics principle underlying this vulnerability lies in the disruption of the precisely calibrated magnetic field environment necessary for accurate signal acquisition. When a subject moves within the static magnetic field, it alters the relationship between spatial location and magnetic field strength, corrupting the spatial encoding process and introducing artifacts that mimic or obscure genuine neural signals.

This problem is particularly pronounced in specific populations and research contexts. In fetal fMRI, for instance, irregular and unpredictable fetal movement represents the most common cause of artifacts, significantly limiting our understanding of early functional brain development [9]. Similarly, in clinical populations such as individuals with autism spectrum disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorders, increased in-scanner head motion can systematically bias between-group differences, potentially leading to false conclusions about neurobiological mechanisms [10] [3]. Understanding the physics of how motion disrupts magnetic fields and creates systematic bias in BOLD signals is therefore essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to generate valid and reliable fMRI findings.

The Physical Mechanisms of Motion Artifacts

How Motion Disrupts Magnetic Field Integrity

The BOLD signal in fMRI is derived from the nuclear magnetic resonance of hydrogen atoms in water molecules within the brain. Under ideal conditions, these atoms precess at a frequency directly proportional to the strength of the static magnetic field (B0), creating a predictable relationship between spatial position and resonance frequency that enables spatial encoding. Head motion within the scanner disrupts this delicate equilibrium through several interconnected physical mechanisms:

Magnetic Field Inhomogeneity Induction: When a subject moves through the spatially varying magnetic field gradients used for spatial encoding, it introduces transient inhomogeneities in the local magnetic field experienced by hydrogen nuclei. These inhomogeneities cause phase errors and signal loss that propagate through the image reconstruction process, creating artifacts in the final BOLD images [9] [11].

Resonance Frequency Shifts: Rotational head motion, particularly in smaller brains such as those of fetuses or children, causes significant resonance frequency shifts due to the non-linear relationship between position and field strength in gradient fields. This effect biases functional connectivity toward stronger short-range connections as the apparent distance between brain regions becomes distorted [9] [3].

k-Space Corruption: Each fMRI volume is reconstructed from raw data acquired in k-space (the spatial frequency domain). Motion during the acquisition of k-space lines creates inconsistencies that result in ghosting, blurring, and signal dropout artifacts in the reconstructed images. Prospective motion correction techniques like MS-PACE attempt to address this by updating the scanning parameters in real-time to account for head position changes [11] [12].

The problem is further compounded by the echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence typically used for fMRI acquisitions, which is particularly sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneities due to its low bandwidth in the phase-encoding direction and long readout times.

From Magnetic Disruption to Systematic BOLD Signal Bias

The disruption of magnetic fields by motion translates into systematic biases in the BOLD signal through well-characterized pathways:

Spurious Variance Introduction: Submillimeter movements can induce spurious variance to BOLD signal timecourses, which can be misattributed to neural activity [9]. This variance follows a specific spatial pattern, preferentially affecting long-distance connections between brain regions.

Distance-Dependent Effects: Motion artifact systematically decreases functional connectivity between distant brain regions while increasing short-range connections [3]. This creates a distinctive signature wherein the motion-FC effect matrix shows a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with the average FC matrix [3].

Global Signal Contamination: Motion-related magnetic field disruptions often affect the entire brain volume, contributing to the global signal. This global contamination presents particular challenges for analysis methods like global signal regression, which must balance artifact removal against potential removal of biologically meaningful signals [9] [13].

Table 1: Quantitative Characterization of Motion Effects on BOLD Signals

| Effect Type | Measured Impact | Measurement Context | Primary Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FD-FC Correlation | Spearman ρ = -0.58 | Correlation between motion-FC effect matrix and average FC matrix | [3] |

| Variance Explained | 23% of signal variance explained by motion after denoising | After ABCD-BIDS denoising | [3] |

| Reduction in Long-Distance FC | Significant decrease | Systematic review of motion effects | [3] |

| Fetal Motion Impact | Substantial artifact generation | Evaluation of 70 fetuses (19-39 weeks GA) | [9] |

| sLFO Amplitude Change | Increased during nicotine abstinence | Clinical relevance of physiological "noise" | [13] |

Methodological Approaches for Quantifying Motion Effects

Experimental Protocols for Motion Impact Assessment

Researchers have developed sophisticated experimental protocols to quantify the specific impact of motion on BOLD signals and functional connectivity:

The SHAMAN Protocol (Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks) This method capitalizes on the observation that traits (e.g., cognitive abilities) are stable over the timescale of an MRI scan while motion is a state that varies from second to second. The protocol involves:

- Splitting each participant's fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on framewise displacement (FD) metrics

- Measuring differences in correlation structure between split halves

- Computing a motion impact score with directionality (positive/negative) indicating whether motion causes overestimation or underestimation of trait-FC effects

- Permuting the timeseries and using non-parametric combining across pairwise connections to generate significance values [3]

Application of this method to the ABCD Study dataset (n = 7,270) revealed that after standard denoising, 42% (19/45) of traits had significant motion overestimation scores and 38% (17/45) had significant underestimation scores [3].

Fetal fMRI Motion Assessment Protocol This specialized approach addresses the unique challenges of in utero imaging:

- Average time series of BOLD signals from cortical regions of interest are extracted

- Time-varying functional connectivity and framewise displacement are computed over sliding windows

- Correlation coefficients are measured between FC and FD timeseries

- An appropriate null distribution is formed by generating surrogate FD time series

- Statistical significance of the FC-FD relationship is determined by comparison to the null distribution [9]

This protocol was systematically evaluated on 70 fetuses with gestational age of 19-39 weeks, demonstrating better accuracy in identifying corrupted FC compared to methods designed for adults [9].

Motion Impact Score Development

The motion impact score represents a significant advancement in quantifying trait-specific motion artifacts in FC. The development process involves:

Preliminary Analysis: Quantifying residual motion after denoising by measuring how much between-participant variability in fMRI timeseries is explained by head motion using linear, log-log transformed models [3].

Motion-FC Effect Matrix Generation: Regressing each participant's FD against their FC to generate a matrix with units of change in FC per mm FD [3].

Trait-Specific Scoring: Applying the SHAMAN method to compute motion overestimation scores (when motion impact direction aligns with trait-FC effect direction) and motion underestimation scores (when motion impact direction opposes trait-FC effect direction) [3].

This approach revealed that even after denoising with the ABCD-BIDS pipeline, 23% of signal variance was still explained by head motion, representing a 69% reduction compared to minimal processing alone [3].

Emerging Correction Technologies and Methodologies

Prospective Motion Correction Techniques

Prospective motion correction technologies aim to address the fundamental physics of motion artifacts by updating scanning parameters in real-time to account for head movement:

Real-time Multislice-to-Volume Motion Correction (MS-PACE) This approach for task-based EPI-fMRI at 7T provides:

- Sub-TR, higher temporal resolution motion correction without external tracking equipment

- Significant, consistent reduction in residual motion across scanned cohorts

- Increased temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) in resting-state scans

- Reduction of artefactual activations compared to standard retrospective correction [11]

Implementation results demonstrate that prospective motion correction improves tSNR and restores motor cortex activation disrupted by motion, recovering activation in primary expected areas [11].

Markerless Tracking for Prospective Motion Correction This contactless approach utilizes:

- Real-time tracking of head position without physical markers

- Continuous adjustment of scanning parameters to compensate for motion

- Improved activation maps and tSNR under clinical conditions with realistic patient motion [12]

This method shows particular promise for clinical settings where patients may have limited motion control, though further research into real-time tracking integration is needed [12].

Deep Learning-Based Correction Approaches

Artificial intelligence approaches represent a paradigm shift in motion artifact correction:

Res-MoCoDiff (Residual-guided Diffusion Models) This novel approach leverages:

- Residual error shifting mechanism during forward diffusion to incorporate information from motion-corrupted images

- U-net backbone with Swin Transformer blocks replacing attention layers for robustness across resolutions

- Combined ℓ1+ℓ2 loss function to promote image sharpness and reduce pixel-level errors

- Four-step reverse diffusion process for computational efficiency [14]

Performance metrics demonstrate superior artifact removal across minor, moderate, and heavy distortion levels, with PSNR up to 41.91±2.94 dB for minor distortions and sampling time reduced to 0.37 s per batch [14].

Deep Learning for Biomarker Discovery This approach utilizes:

- Synthetic BOLD signals generated using supercritical Hopf brain network model

- Training of deep learning models to predict bifurcation parameters from BOLD signals

- Application to empirical data (HCP dataset) to estimate bifurcation parameter distributions

- Classification of brain states based on predicted bifurcation values [15]

This method achieved 62.63% accuracy in classifying bifurcation values into eight cohorts, well above the 12.50% chance level [15].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Motion Correction Methods

| Method | Key Innovation | Performance Metrics | Limitations | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Res-MoCoDiff | Residual-guided diffusion model | PSNR: 41.91±2.94 dB (minor distortions); Sampling time: 0.37 s/batch | Computational intensity during training | [14] |

| Prospective MS-PACE | Real-time slice-to-volume correction | Significant tSNR increase; Reduced artefactual activations | Requires specific sequence implementation | [11] |

| Markerless PMC | Contactless tracking | Improved tSNR; Restored motor cortex activation | Further research needed for clinical application | [12] |

| sLFO Isolation (RIPTiDe) | Physiological signal extraction | Correlation with dependence severity and craving | Interpretation complexity for clinical translation | [13] |

| Fetal fMRI Censoring | Motion-FC correlation analysis | Better accuracy than adult methods | Specialized for fetal population | [9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Motion Artifact Research

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies head motion between volumes | General fMRI quality assessment | Composite of translational and rotational parameters |

| SHAMAN | Computes trait-specific motion impact scores | Large-scale studies (ABCD, HCP) | Distinguishes overestimation vs. underestimation |

| RIPTiDe | Isolates systemic low-frequency oscillations (sLFOs) | Physiological noise characterization | Identifies globally present physiological signals |

| Res-MoCoDiff | Corrects motion artifacts using diffusion models | Structural and functional MRI | Preserves fine structural details; fast sampling |

| MS-PACE | Real-time prospective motion correction | Task-based fMRI at ultra-high field | Sub-TR correction without external equipment |

| Global Signal Regression | Removes global signal components | Functional connectivity analysis | Controversial but effective for motion reduction |

| Censoring (Scrubbing) | Removes high-motion volumes from analysis | Post-hoc motion mitigation | Balance between data retention and artifact removal |

| Generative Brain Network Models | Simulates BOLD signals with known parameters | Biomarker discovery; method validation | Provides ground truth for algorithm development |

Visualizing Motion Artifact Pathways and Correction Strategies

Physics of Motion Artifact Generation

Motion Correction Strategy Workflow

The physics of motion artifacts in fMRI represents a fundamental challenge that transcends mere technical nuisance, creating systematic biases that can compromise the validity of brain-behavior associations and clinical findings. The disruption of carefully calibrated magnetic fields by head movement introduces spurious variance in BOLD signals that follows distinctive spatial patterns, preferentially affecting long-distance functional connections while increasing short-range connectivity. This systematic bias disproportionately impacts populations with naturally higher movement, including children, individuals with neuropsychiatric conditions, and fetal subjects, potentially creating false group differences or obscuring genuine effects.

Moving forward, the field requires a multifaceted approach that combines physical prevention strategies, advanced prospective correction technologies, sophisticated post-processing algorithms, and rigorous impact validation methods. Promising avenues include deep learning-based correction models like Res-MoCoDiff that preserve structural details while significantly reducing computational overhead, prospective methods like MS-PACE that correct motion in real-time without external equipment, and validation frameworks like SHAMAN that provide trait-specific motion impact scores. Furthermore, recognizing that certain "noise" components like systemic low-frequency oscillations may carry clinically relevant information encourages a more nuanced approach to motion artifact management rather than simple removal.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, implementing comprehensive motion mitigation strategies is no longer optional but essential for generating valid, reproducible fMRI findings. This requires careful consideration of population-specific challenges, selection of appropriate correction methods validated for specific research contexts, and transparent reporting of motion impacts on reported results. Only through such rigorous attention to the physics of disruption can we ensure that the BOLD signals we measure reflect genuine neural phenomena rather than artifacts of movement within magnetic fields.

In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research, the term "corruption" most accurately refers to motion-induced artifacts that systematically alter measured functional connectivity. This technical guide examines how in-scanner head motion creates a specific spatial pattern of corruption: artificially decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity [16]. This artifact poses a significant threat to the validity of cognitive tasks research, as it can generate false results that are erroneously interpreted as neuronal effects [16].

Understanding this phenomenon is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Motion artifacts can confound studies comparing different populations (e.g., patients versus controls) and hinder the accurate assessment of functional networks, ultimately impacting the development and evaluation of neurotherapeutics [16]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms, spatial patterns, and methodological corrections for this pervasive issue in fMRI research.

The Impact of Head Motion on Functional Connectivity

Head motion during fMRI scans is a major source of noise, fundamentally altering the measured correlations between brain regions. The observed spatial pattern is robust and consistent across studies:

- Diminished Long-Distance Connectivity: Motion artifact leads to a reduction in correlation strength between spatially distant brain regions. This effect is particularly pronounced in networks like the Default Mode Network (DMN), which includes key hubs such as the medial prefrontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, and the inferior parietal lobule [16].

- Enhanced Short-Range Connectivity: Simultaneously, motion causes an artificial inflation of correlation values between geographically proximate brain areas [16]. This creates a false impression of heightened local functional integration.

Research by Satterthwaite et al. quantified this transition point, demonstrating that the effect of motion shifts from causing increased connectivity to decreased connectivity at a distance of approximately 96 mm between network nodes [16]. This distance-dependent artifact profile is a hallmark of motion corruption.

Table 1: Characteristics of Motion-Induced Connectivity Artifacts

| Feature | Long-Distance Connectivity | Short-Range Connectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of Effect | Decreased | Increased |

| Primary Networks Affected | Default Mode Network (DMN) | Local, adjacent cortical areas |

| Typical Affected Regions | Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Inferior Parietal Lobule [16] | Posterior cingulate cortex and nearby areas [16] |

| Impact on Analysis | False negative correlations; weakened network structure | False positive correlations; inflated local clustering |

Mechanisms Linking Motion to Spatial Corruption Patterns

The underlying mechanisms through which head motion corrupts fMRI signals are multifaceted. When a participant moves their head, the content of each voxel changes, disrupting the magnetic field's uniformity. This alteration resets the steady-state magnetization, particularly in tissue that has moved from one slice to another during the sequence [16]. The consequence is a complex artifact that manifests differently across spatial scales.

Motion causes spin history effects and changes in magnetic field inhomogeneity, which are not uniform across the brain. The signal disruptions are more consistent and coherent within local regions, leading to inflated short-range correlations. In contrast, the signal changes between distant regions become less synchronized, resulting in spurious decreases in long-distance correlations [16]. This creates the characteristic spatial pattern of corruption that can easily be mistaken for genuine neuronal effects, especially in studies comparing groups with different inherent motion levels, such as children versus adults or patient populations versus healthy controls [16].

Methodological Approaches for Detection and Correction

Several methodological approaches have been developed to quantify and correct for motion-related artifacts in fMRI data. The table below summarizes key metrics and correction methods used in the field.

Table 2: Motion Detection Metrics and Correction Methods

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement (FD) [16] | Measures volume-to-volume head movement; used to identify excessive motion. |

| Motion Quantification | Regional Displacement Interaction (RDI) [16] | Assesses localized motion effects on connectivity. |

| Data Correction | Scrubbing [16] | Removal of high-motion volumes from the time series. |

| Data Correction | ICA+FIX Cleaning [17] | Uses independent component analysis to identify and remove structured artifacts. |

| Registration Quality Control | Functional MRI of the brain's nonlinear image registration tool (FNIRT) [16] | Quantifies registration accuracy to a standard template. |

| Registration Quality Control | Boundary-based registration (mcBBR) [16] | Measures the minimal cost for linear registration quality. |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Management

To ensure data integrity in cognitive tasks research, incorporating rigorous motion management protocols is essential. The following workflow, derived from established methodologies in the field, outlines a comprehensive approach [18] [17]:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire resting-state or task-based fMRI data. The UK Biobank protocol, for instance, involves a 6-minute resting-state scan (490 time points, TR=0.735s) and task-based scans, using a 3-Tesla scanner [17].

- Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing steps, which typically include motion correction, group-mean intensity normalization, and high-pass temporal filtering. Spatial smoothing (e.g., with a Gaussian kernel of FWHM 5 mm) may be applied to task fMRI [17].

- Motion Quantification: Calculate subject-level motion metrics, such as Framewise Displacement (FD), to quantify head motion throughout the scan [16].

- Artifact Removal: Implement advanced cleaning procedures. For resting-state data, ICA+FIX can be used to automatically remove structured artifacts [17]. For both resting-state and task data, scrubbing can be employed to remove volumes where FD exceeds a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.2 mm) [16].

- Connectivity Analysis: Perform functional connectivity analysis only on the cleaned data.

- Statistical Control: In group-level analyses, include the average FD as a nuisance covariate to statistically control for residual effects of motion [16].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for managing fMRI motion artifacts.

This section details key reagents, software, and data resources essential for conducting robust fMRI research on connectivity and motion artifacts.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for fMRI Connectivity Studies

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Motion & Connectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSL FEAT [17] | Software Toolbox | fMRI data analysis; first-level model fitting. | Used to extract z-statistic maps from task fMRI; includes motion parameters in the model. |

| fMRIprep [17] | Software Tool | Robust preprocessing pipeline for fMRI data. | Automates motion correction and other preprocessing steps, standardizing the initial data cleaning. |

| ICA+FIX [17] | Software Algorithm | Automatic cleanup of fMRI data. | Identifies and removes noise components from resting-state data, including motion-related artifacts. |

| SwiFUN [17] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts task activation from resting-state fMRI. | Showcases advanced modeling that must account for motion to achieve accurate predictions. |

| UK Biobank [17] | Biomedical Database | Provides large-scale health and imaging data. | Enables large-sample studies of motion effects across populations; includes preprocessed fMRI. |

| ABCD Study [17] | Longitudinal Dataset | Tracks brain development in children. | Critical for studying age-related motion patterns and their impact on connectivity. |

Emerging Frontiers and Advanced Techniques

The field is rapidly evolving with new technologies and analytical approaches to better understand and mitigate spatial corruption.

- Deep Learning for Enhanced Classification: Recent studies use Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), such as 1D-CNN and BiLSTM models, to classify cognitive states from fMRI data [18]. A key finding is that these models' classification accuracy is significantly correlated with individual task performance (p < 0.05 for 1D-CNN, p < 0.001 for BiLSTM), suggesting that motion-related data corruption in poorer-performing subjects may reduce the distinctiveness of neural signatures [18].

- Multimodal Integration for Validation: Combining fMRI with other modalities, such as functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRs), is a promising frontier. fNIRs offers superior temporal resolution and is less susceptible to motion artifacts, providing a valuable cross-validation tool for fMRI-derived connectivity measures, especially in naturalistic settings or with populations prone to movement [19].

- Transformer-Based Prediction Models: Architectures like SwiFUN (Swin fMRI UNet Transformer) represent the cutting edge in predicting task-related brain activity from resting-state fMRI [17]. These models must inherently learn to manage motion-related variance to achieve high prediction accuracy, marking a shift towards more robust, data-driven inference of brain function.

Diagram 2: Logical relationships of motion artifacts in fMRI research.

Head motion represents a significant threat to the validity of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, systematically introducing spurious brain-behavior associations that can be misinterpreted as genuine neurobiological effects. This technical review examines how in-scanner motion produces false positive findings in clinical and cognitive group studies, where motion is often correlated with the traits of interest. We synthesize current evidence quantifying this problem, detail the mechanistic pathways through which motion artifacts corrupt fMRI signals, and evaluate methodological frameworks for detecting and mitigating these spurious effects. With evidence indicating that even state-of-the-art denoising leaves substantial residual motion artifacts, researchers must implement rigorous motion management strategies throughout experimental design, data acquisition, and analysis pipelines to ensure the reliability of fMRI findings in both basic and clinical research contexts.

In-scanner head motion constitutes a fundamental methodological challenge for fMRI research, particularly in studies comparing clinical populations or developmental groups where motion tendencies systematically differ from control participants. The problem is especially pernicious because motion artifacts are not random noise but introduce systematic biases that can mimic or mask genuine neurobiological effects [20]. Early studies of clinical populations such as autism spectrum disorder initially reported decreased long-distance functional connectivity, which were later attributed to increased head motion in these participants rather than genuine neural characteristics [3]. This revelation prompted widespread re-evaluation of the fMRI literature and spurred methodological innovation in motion correction.

Motion artifacts persist as a critical concern despite advances in denoising algorithms because of the complex, nonlinear relationship between physical head movements and their impact on the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal [21]. The problem is particularly acute in resting-state fMRI, where the timing of neural processes is unknown, making it difficult to distinguish motion-related signal fluctuations from neurally-driven connectivity patterns [3]. Furthermore, certain physiological noise sources, such as respiratory activity, are generated by the same underlying brain networks that produce functional signals of interest, creating additional challenges for distinguishing signal from noise [22].

Quantitative Evidence: Establishing the Magnitude of the Problem

Prevalence of Motion-Induced Spurious Associations

Recent large-scale studies have quantified the extensive impact of residual head motion on brain-behavior associations, even following standard denoising procedures. Analysis of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study dataset (n = 7,270) revealed alarming rates of spurious associations across diverse traits after standard denoising without motion censoring [3].

Table 1: Motion Impact on Trait-FC Associations in ABCD Study

| Motion Impact Type | Traits Affected (Pre-Censoring) | Traits Affected (Post-Censoring FD < 0.2mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Significant Overestimation | 42% (19/45 traits) | 2% (1/45 traits) |

| Significant Underestimation | 38% (17/45 traits) | No decrease observed |

| Overall Impact | 80% of traits showed significant motion impact | Censoring reduced but did not eliminate problem |

The data demonstrates that motion can cause both overestimation and underestimation of true trait-functional connectivity effects. While aggressive censoring (framewise displacement < 0.2mm) substantially reduced motion-related overestimation, it did not decrease the number of traits with significant underestimation scores, indicating a complex relationship between motion correction strategies and bias direction [3].

Impact on Statistical Inference and False Positive Rates

The spurious associations introduced by motion have direct implications for false positive rates in statistical inference. When multiple comparisons are performed without appropriate correction, the family-wise error rate increases dramatically, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: False Positive Risk in Multiple Comparisons

| Number of Tests | Per-Comparison α | Family-Wise α (False Positive Rate) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| 6 | 0.05 | 0.26 |

| 10 | 0.05 | 0.40 |

| 15 | 0.05 | 0.54 |

Traditional correction methods like Bonferroni adjustment can substantially reduce false positives but at the cost of increased false negative rates [23]. Alternative approaches such as the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling false discovery rate offer a more balanced approach when dealing with the numerous comparisons typical in fMRI research [23].

Mechanisms: How Motion Generates Spurious Associations

Spatial Characteristics of Motion Artifacts

Motion artifacts exhibit distinctive spatial patterns that contribute to their capacity to generate spurious findings. Analysis of motion-FC effect matrices reveals a strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) with average functional connectivity matrices, indicating that head motion systematically decreases long-distance connectivity while increasing short-range connections [3]. This pattern emerges because in-scanner motion causes signal dropouts that disproportionately affect connections between distant brain regions while creating artificial correlations between adjacent areas [20].

The spatial distribution of motion itself follows biomechanical constraints, with minimal movement near the atlas vertebrae (where the skull attaches to the neck) and increasing motion with distance from this anchor point [20]. Furthermore, motion produces increased image smoothness and causes large signal increases at tissue class boundaries due to partial volume effects, particularly at the edge of the brain and around ventricles [20].

Temporal and Spectral Properties

Motion-related artifacts demonstrate characteristic temporal signatures that can help distinguish them from neural signals. Immediately following movement events, motion produces a substantial drop in signal that scales with movement magnitude [20]. These signal changes are temporally circumscribed and maximal at the volume acquired immediately after an observed movement. Additionally, longer duration artifacts (persisting up to 8-10 seconds) occur idiosyncratically, potentially due to motion-related changes in CO₂ accompanying yawning or deep breathing [20].

The interaction between motion and MRI physics introduces nonlinear relationships between head position and signal intensity that are difficult to remove using standard rigid-body correction methods. These nonlinear effects include spin excitation history effects that persist after movement, interpolation artifacts during image reconstruction, and interactions between magnetic field and head position that introduce distortions in EPI time series [20].

Diagram 1: Pathways Through Which Motion Generates Spurious Associations

Motion Correlations with Traits of Interest

The most problematic aspect of motion artifacts arises from systematic correlations between in-scanner movement and participant characteristics. Numerous studies have established that participants with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and other clinical conditions tend to have higher in-scanner head motion than neurotypical participants [3]. This creates a perfect storm where the variable of interest (clinical status) is confounded with the major source of artifact (head motion).

Even when denoising algorithms remove much of the overall signal variance associated with motion, inferences about motion-correlated traits may remain significantly impacted by residual motion artifact [3]. This residual artifact introduces systematic bias that can either inflate or obscure genuine effects, potentially leading to false conclusions in group comparison studies.

Methodological Framework: Detection and Mitigation

Motion Quantification and Impact Assessment

Accurate motion quantification provides the foundation for effective artifact mitigation. The most common approach involves calculating Framewise Displacement from the six realignment parameters (three translations, three rotations) generated during image registration [20]. FD measures should be calculated consistently within studies, as different implementations (e.g., Power et al. versus Jenkinson et al.) produce values on different scales despite being highly correlated [20].

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks represents a recent methodological advance for assessing motion impact on specific trait-FC relationships [3]. SHAMAN operates by measuring differences in correlation structure between split high- and low-motion halves of each participant's fMRI timeseries, capitalizing on the relative stability of traits over time. This approach can distinguish between motion causing overestimation versus underestimation of trait-FC effects and provides a motion impact score with associated p-value [3].

Denoising Methodologies and Comparative Efficacy

Multiple denoising approaches have been developed to mitigate motion artifacts, with varying efficacy and trade-offs. Table 3 summarizes key methodologies and their characteristics.

Table 3: Motion Denoising Methodologies in fMRI

| Method Category | Specific Approaches | Mechanism | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression-Based | Realignment parameter regression, aCompCor, GSR | Remove variance associated with motion estimates | Incomplete removal of nonlinear effects, GSR controversial |

| Censoring | Framewise displacement scrubbing, spike regression | Remove high-motion volumes from analysis | Data loss, discontinuities in time series |

| Component-Based | ICA-AROMA, visual inspection of ICs | Identify and remove motion-related components | Subjectivity in classification, requires expertise |

| Model-Based | Structured low-rank matrix completion | Estimate and recover missing data using signal priors | Computational complexity, implementation challenges |

| Prospective | Volume reacquisition, prospective motion correction | Prevent motion occurrence or correct during acquisition | Requires specialized sequences or hardware |

Recent comparisons indicate that aCompCor, which estimates nuisance signals from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid using principal components analysis, more effectively attenuates motion artifacts than mean signal regression [24]. aCompCor offers the advantage of identifying multiple nuisance signals without assuming a specific relationship between motion and signal change, potentially better capturing delayed and nonlinear effects [24].

Structured low-rank matrix completion represents a promising advanced approach that formulates motion compensation as a matrix recovery problem [25]. This method excises high-motion volumes and exploits linear recurrence relations in BOLD signals to reconstruct missing data while simultaneously performing slice-timing correction [25].

Diagram 2: Motion Artifact Management Workflow

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Management

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Quantification | Framewise Displacement, DVARS | Quantify volume-to-volume motion | Standardize calculation method across studies |

| Denoising Pipelines | ABCD-BIDS, aCompCor, ICA-AROMA | Remove motion-related variance | Balance artifact removal against signal preservation |

| Impact Assessment | SHAMAN, distance-dependent correlation | Evaluate residual motion effects | Trait-specific versus global motion impact |

| Statistical Correction | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR, mixed effects models | Address multiple comparisons and confounding | Control false positives without excessive false negatives |

| Data Quality Control | Visual inspection, motion diagnostics | Identify problematic datasets | Establish exclusion criteria priori |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

SHAMAN Protocol for Trait-Specific Motion Impact Assessment

The Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks provides a rigorous method for evaluating whether specific trait-FC relationships are compromised by motion artifacts [3]. The experimental protocol involves:

Data Preparation: Process resting-state fMRI data using standard denoising pipelines (e.g., ABCD-BIDS pipeline including global signal regression, respiratory filtering, spectral filtering, despiking, and motion parameter regression).

Motion Stratification: For each participant, split the fMRI timeseries into high-motion and low-motion halves based on framewise displacement values.

Connectivity Analysis: Calculate separate functional connectivity matrices for high-motion and low-motion halves.

Trait-FC Effect Estimation: Compute the correlation between trait measures and FC strength separately for each motion stratum.

Impact Score Calculation: Derive motion impact scores by comparing trait-FC effects between high-motion and low-motion strata, with permutation testing to establish significance.

Direction Classification: Classify significant impacts as motion overestimation (impact score aligned with trait-FC effect direction) or underestimation (opposite direction) [3].

Validation Using Structured Low-Rank Matrix Completion

Advanced motion correction methods require rigorous validation against established benchmarks:

Simulation Experiments: Generate synthetic fMRI data with known ground truth connectivity and introduced motion artifacts, then evaluate recovery of true connectivity patterns after correction.

Motion-Added Validation: Acquire low-motion reference datasets, then introduce realistic motion artifacts to create paired datasets for evaluating correction efficacy.

Functional Connectivity Specificity: Assess correction quality by measuring the spatial specificity of known functional networks (e.g., default mode network, motor network) following processing with different pipelines [24].

Motion-FC Correlation: Evaluate residual correlations between framewise displacement and functional connectivity measures, with effective correction showing minimal systematic relationships [25].

Head motion remains a formidable challenge for fMRI research, with the capacity to generate spurious associations that can misdirect scientific understanding and clinical applications. The evidence reviewed demonstrates that even advanced denoising leaves substantial residual motion artifacts that can systematically bias brain-behavior associations, particularly for traits correlated with movement tendency.

Moving forward, the field requires increased adoption of rigorous motion management practices including:

- Prospective motion correction during data acquisition

- Standardized reporting of motion metrics and denoising procedures

- Routine implementation of trait-specific motion impact assessments like SHAMAN

- Development of robust statistical methods that account for motion confounding without sacrificing sensitivity

Furthermore, researchers must recognize that no universal motion correction solution exists—optimal approaches must be tailored to specific research questions, participant populations, and acquisition parameters. By embracing comprehensive motion management frameworks that extend from experimental design through final analysis, the fMRI community can enhance the reliability and reproducibility of findings in both basic cognitive neuroscience and clinical application domains.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become a cornerstone technique for investigating the neural correlates of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, the inherent behavioral characteristics of these populations—including restlessness, hyperactivity, and difficulty with impulse control—systematically predispose them to increased head motion during scanning. This motion introduces significant artifacts into fMRI data, creating a fundamental confounding pattern: the very traits we seek to study potentially generate the noise that obscures or distorts our findings. This case study examines how motion artifacts correlate with clinical traits in ASD and ADHD research, quantifies the resulting biases, and presents methodological frameworks for distinguishing true neural signatures from motion-related confounds.

The problem extends beyond simple data quality degradation to deeper methodological and conceptual challenges. When researchers exclude high-motion participants to ensure data quality, they inadvertently create a selection bias that limits the generalizability of findings. In ASD populations, this practice systematically eliminates individuals with more severe clinical presentations, potentially skewing our understanding of the disorder's neural basis. Furthermore, the complex relationship between motion, data quality, and individual differences in task performance creates additional layers of interpretation challenges that require sophisticated analytical approaches to untangle.

Quantitative Evidence: Documenting the Motion-Trait Relationship

Exclusion Bias in Autism Spectrum Disorder

A comprehensive analysis of 545 children (173 autistic and 372 typically developing) participating in resting-state fMRI studies revealed profound exclusion biases resulting from motion-related quality control practices. As shown in Table 1, autistic children were significantly more likely to be excluded than typically developing children across both lenient and strict motion criteria [26].

Table 1: Differential Exclusion Rates of Autistic Children in fMRI Studies

| Motion Exclusion Criterion | Autistic Children Excluded | Typically Developing Children Excluded | Exclusion Ratio (ASD:TD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lenient | 28.5% | 16.1% | 1.77:1 |

| Strict | 81.0% | 60.1% | 1.35:1 |

This differential exclusion created significant systematic biases in the resulting research samples. Autistic children who remained in studies after motion exclusion tended to be older, have milder social deficits, better motor control, and higher intellectual ability than the original sample [26]. These variables were also significantly related to functional connectivity strength among children with usable data, suggesting that the generalizability of previous studies reporting naïve analyses (i.e., based only on participants with usable data) may be limited by the selection of older children with less severe clinical profiles [26].

Motion-Related Performance Classification in Deep Learning Models

Recent research using deep neural networks (DNNs) to classify cognitive task states from fMRI data has revealed intriguing relationships between motion, task performance, and classification accuracy. As detailed in Table 2, both one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1D-CNN) and bidirectional long short-term memory networks (BiLSTM) demonstrated significantly lower classification accuracy for individuals with poorer task performance [18].

Table 2: Relationship Between Task Performance and fMRI Classification Accuracy in DNN Models

| Model Architecture | Overall Classification Accuracy | Correlation with Task Performance (EBQ) | Statistical Significance | Behavioral Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D-CNN | 81% (Macro AUC = 0.96) | r = -0.35 | p = 0.05 | Moderate |

| BiLSTM | 78% (Macro AUC = 0.95) | r = -0.41 | p < 0.05 | High |

The negative correlation indicates that individuals with higher effective behavioral quartile (EBQ) scores, reflecting better task performance, tended to have fewer incorrect predictions in both models. When comparing EBQ scores for correct versus incorrect predictions, both models showed significant differences (1D-CNN: t-statistic = 2.45, p < 0.05; BiLSTM: t-statistic = 3.77, p < 0.001), with correct predictions associated with higher behavioral performance [18]. This pattern suggests that task-differentiating attributes in the fMRI signal are more pronounced during better behavioral performance, which may simultaneously correlate with reduced motion.

Methodological Approaches: Techniques for Addressing Motion Confounds

Statistical Correction Frameworks

To address the biases introduced by motion-related exclusions, researchers have developed sophisticated statistical frameworks that treat excluded scans as a missing data problem rather than simply omitting them. The doubly robust targeted minimum loss-based estimation (DRTMLE) with an ensemble of machine learning algorithms represents one promising approach [26].

This method involves:

- Modeling the Selection Process: Using machine learning algorithms to model the probability of scan exclusion based on clinical and demographic variables

- Outcome Modeling: Predicting functional connectivity outcomes based on the same set of variables

- Doubly Robust Estimation: Combining these models to produce effect estimates that remain consistent if either the selection or outcome model is correctly specified

When applied to ASD data, this approach selected more edges that differed in functional connectivity between autistic and typically developing children than the naïve approach, supporting its utility for improving the study of heterogeneous populations in which motion is common [26].

Integrative Analysis Approaches

Combining fMRI with complementary neuroimaging modalities represents another promising strategy for addressing motion-related confounds. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRs) offers particularly strong synergies, as it provides superior temporal resolution and greater resilience to motion artifacts compared to fMRI [19].

Table 3: Multimodal Integration Approaches for Motion Resilience

| Integration Method | Description | Applications | Benefits for Motion Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous fMRI-fNIRs | Simultaneous data acquisition during identical tasks | Spatial localization, validation studies | fNIRs provides motion-tolerant validation for fMRI findings |

| Asynchronous fMRI-fNIRs | Separate but complementary data collection | Naturalistic settings, clinical populations | Enables data collection in challenging populations across different contexts |

| Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling | Data-driven subject-level predictive modeling | Symptom severity prediction, cross-disorder comparison | Whole-brain approach reduces reliance on motion-affected specific regions |

The integration of fMRI's high spatial resolution with fNIRs' temporal precision and operational flexibility facilitates more robust spatiotemporal mapping of neural activity, validated across motor, cognitive, and clinical tasks [19]. This multimodal approach is particularly advantageous in clinical settings, where the portability of fNIRs allows for bedside monitoring of patients alongside the detailed structural and functional insights provided by fMRI.

Individualized Functional Network Mapping

Traditional group-level analytical approaches in functional connectivity research may amplify motion-related confounds by obscuring individual differences. Recent advances in individualized functional network mapping using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) methods enable the definition of subject-specific functional networks, providing a more nuanced understanding of neural organization in neurodevelopmental disorders [27].

This methodology involves:

- Data Preprocessing: Standard preprocessing including motion correction, registration, smoothing, and nuisance regression

- Network Initialization: Construction of a group-level matrix from randomly selected subjects for decomposition

- Individual Decomposition: Application of spatially regularized NMF to define 17 large-scale functional networks for each participant

- Connectivity Analysis: Calculation of both node-wise and edge-wise functional connectivity metrics

This individualized approach has revealed disorder-specific and shared regional and edge-wise functional connectivity differences between ASD and ADHD, facilitating understanding of the neurobiological basis for both disorders while potentially mitigating motion-related confounds through personalized network identification [27].

Experimental Workflows and Analytical Pipelines

The relationship between motion, data quality, and analytical outcomes necessitates carefully designed experimental workflows. The following diagram illustrates an integrated approach to addressing motion confounds throughout the research pipeline:

Integrated Workflow for Motion Management: This workflow demonstrates a comprehensive approach to addressing motion confounds throughout the research pipeline, from study design to result interpretation.

Contrast Subgraph Analysis for Mesoscopic Network Differences

In ASD research, where conflicting reports of both hyper-connectivity and hypo-connectivity abound, contrast subgraph analysis provides a network comparison technique to capture mesoscopic-scale differential patterns of functional connectedness while potentially mitigating motion effects. This approach involves:

- Network Construction: Computing standard functional connectivity matrices from preprocessed timeseries using Pearson's correlation coefficient

- Sparsification: Applying the SCOLA algorithm to obtain individual sparse weighted networks with consistent densities

- Summary Graphs: Combining group functional networks into single summary graphs for each cohort

- Difference Graph: Creating a network with edge weights equal to the difference between summary graphs

- Optimization: Solving an optimization problem to identify contrast subgraphs that maximize density differences between groups

- Bootstrapping: Iterating detection across equally-sized samples to generate families of contrast subgraphs

- Statistical Validation: Selecting significantly overrepresented node sets using Frequent Item-set Mining

This methodology has revealed significantly larger connectivity among occipital cortex regions and between the left precuneus and superior parietal gyrus in ASD subjects, alongside reduced connectivity in the superior frontal gyrus and temporal lobe regions [28]. The approach reconciles within a single framework multiple previous separate observations about functional connectivity alterations in ASD.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Solutions

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Motion-Resilient fMRI Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function and Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Prevention | Participant Training Programs | Pre-scan behavioral preparation to reduce motion | Especially critical for pediatric and neurodevelopmental populations |

| Motion Quantification | Frame-wise Displacement (FD) | Quantifies head motion between volumes | Standard threshold: FD < 0.5mm for inclusion |

| Motion Correction | Motion Scrubbing | Removal of high-motion volumes with cubic spline interpolation | Reduces data points but preserves participant inclusion |

| Statistical Control | Motion Covariates in Models | Includes motion parameters as nuisance regressors | Standard practice but may not fully address systematic biases |

| Advanced Modeling | Doubly Robust Estimation (DRTMLE) | Addresses missing data from motion-related exclusions | Requires specialized statistical expertise |

| Multimodal Validation | Simultaneous fMRI-fNIRs | Cross-validates findings with motion-resilient modality | Hardware compatibility challenges require resolution |

| Individualized Mapping | Non-negative Matrix Factorization | Defines subject-specific functional networks | Reduces reliance on potentially problematic group averages |

| Network Analysis | Contrast Subgraph Extraction | Identifies mesoscopic network differences | Robust to motion-induced noise in individual connections |

The relationship between motion and clinical traits in ASD and ADHD research represents more than a technical nuisance—it constitutes a fundamental methodological challenge that threatens the validity and generalizability of findings. The evidence presented in this case study demonstrates that motion artifacts systematically correlate with the very traits we seek to study, creating confounding patterns that can lead to erroneous conclusions about neural correlates of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Moving forward, the field must adopt more sophisticated approaches that explicitly account for these relationships rather than attempting to eliminate motion through exclusion. Promising directions include:

- Improved Motion Resilience: Development of acquisition sequences and hardware that minimize motion sensitivity

- Advanced Statistical Methods: Wider adoption of techniques like DRTMLE that properly handle missing data due to motion exclusion

- Multimodal Integration: Strategic combination of fMRI with more motion-tolerant modalities like fNIRs

- Individualized Approaches: Movement beyond group-level analyses to personalized functional network mapping

- Transparent Reporting: Comprehensive documentation of motion exclusion rates and their potential impact on sample representativeness

By implementing these approaches, researchers can transform motion from a confounding variable into a source of valuable information about the relationship between behavior and neural function in neurodevelopmental disorders. This paradigm shift will enhance the validity, reproducibility, and clinical relevance of neuroimaging findings in ASD and ADHD research.

Correcting the Unseen: Prospective and Retrospective Methodologies for Motion Artifact Mitigation

In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), subject motion is one of the most significant confounding factors affecting data quality and the validity of statistical inferences. Even minor head movements can introduce signal variations that obscure the subtle Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) effects, which typically represent less than a 1% signal change [29]. In cognitive tasks research, this is particularly problematic as in-scanner motion is frequently correlated with variables of interest such as age, clinical status, and cognitive ability, potentially introducing systematic bias into study results [20]. Motion artifacts manifest not as classical blurring or ghosting but as complex temporal signal inconsistencies across sequentially acquired volumes, severely deteriorating statistical analysis and distorting activation maps [30].

The Fundamental Challenge of Motion in fMRI

Physics of Motion Artifacts

While single-shot 2D EPI acquisitions (under 100ms) effectively "freeze" motion for individual slices, complete volumetric data requires sequential acquisition of multiple slices over several seconds. This creates two primary types of inconsistencies [30]:

- Intra-volume inconsistencies: Resulting from motion during the acquisition of different slices within the same volume.

- Inter-volume instabilities: Arising from motion between successive volume acquisitions across the time series.

Physiological and Physical Effects of Motion

Head motion during fMRI scans triggers multiple physical phenomena that contribute to undesired temporal signal variations. The table below categorizes these primary effects:

Table 1: Principal Physical Effects of Motion in fMRI

| Source | Effect | Consequence | Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF Transmit | Motion relative to RF excitation pulses | Spin-history effects, contrast modulation | High |

| RF Receive | Motion relative to receiver coil sensitivities | Intensity modulation | High |

| Spatial Encoding | Motion relative to gradient encoding coordinates | Partial-volume effect modulation | High |

| Magnetic Field Homogeneity | Motion-induced changes in B₀ field | B₀ modulation, image distortions | Medium |

The spin-history effect is particularly detrimental to fMRI data quality. When a brain region moves out of and then back into the imaging plane between successive excitations, it experiences different RF pulse histories, leading to signal variations unrelated to neural activity [30]. Additionally, motion alters the relationship between the head and the stationary receiver coil sensitivity profiles, creating position-dependent signal weighting that cannot be fully corrected retrospectively, especially in parallel imaging and simultaneous multi-slice acquisitions [30].

Motion Correction Approaches

Retrospective Motion Correction

Traditional retrospective correction methods apply rigid-body transformations to align each volume in a time series to a reference volume during data processing. These methods estimate motion through 6 realignment parameters (3 translations and 3 rotations) and are integrated into most fMRI analysis toolboxes [30] [20]. While computationally robust and sequence-independent, retrospective approaches have fundamental limitations:

- No intra-volume correction: Cannot address slice-to-volume motion inconsistencies [30]

- Spin-history effects: Unable to correct for signal variations due to differential RF excitation histories [30]

- Interpolation artifacts: Image resampling during realignment can introduce its own artifacts [20]

- Magnetic field interactions: Cannot compensate for motion-induced changes in B₀ field inhomogeneity [30]

Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) Fundamentals

Prospective Motion Correction represents a paradigm shift by actively preventing the accumulation of motion artifacts during data acquisition rather than attempting to remove them afterward. PMC systems utilize MR-compatible optical tracking systems that monitor head position in real-time (typically at 60-100Hz). This tracking data continuously updates the imaging sequence, adjusting the slice position and orientation, gradients, and radiofrequency pulses to maintain a consistent coordinate system relative to the participant's head [30] [31].

The fundamental advantage of PMC is that it maintains a fixed relationship between the imaging coordinates and the anatomy throughout the scan, effectively preventing many motion-induced artifacts from occurring in the first place.

Table 2: Comparison of Motion Correction Approaches

| Feature | Retrospective Correction | Prospective Correction (PMC) |

|---|---|---|

| Correction Principle | Post-acquisition image registration | Real-time sequence adjustment during acquisition |

| Temporal Resolution | Limited by TR (volume acquisition time) | High (∼60-100Hz) |

| Intra-volume Correction | No | Yes |

| Spin-History Effects | Cannot correct | Mitigates by maintaining consistent excitation |

| Magnetic Field Interactions | Cannot address | Partially addresses through real-time updates |

| Implementation Complexity | Low (post-processing) | High (requires specialized hardware) |

Technical Implementation of PMC Systems

Core System Components

A complete PMC system requires several integrated hardware and software components:

- Motion Tracking System: MR-compatible optical cameras (typically infrared) with tracking markers attached to the participant

- Reference Scan: A high-resolution anatomical scan establishing the initial relationship between tracking markers and brain anatomy

- Real-Time Control Interface: Hardware/software platform that feeds motion data into the scanner reconstruction process

- Sequence Modification: Pulse sequences capable of receiving real-time position updates and adjusting imaging parameters accordingly

Operational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous feedback loop that enables prospective motion correction during fMRI acquisition:

Integration with fMRI Sequences

PMC can be integrated with various fMRI acquisition schemes, though each presents unique considerations:

- 2D Multi-slice EPI: The most common application, where PMC adjusts slice position and orientation in real-time

- Simultaneous Multi-slice (SMS): Requires more complex corrections due to accelerated acquisition

- 3D acquisitions: Particularly benefits from PMC as motion affects the entire k-space dataset

Advanced implementations combine PMC with dynamic distortion correction to additionally address motion-induced changes in magnetic field inhomogeneity, providing comprehensive artifact mitigation [30].

Experimental Evidence and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Benefits of PMC

Research studies have demonstrated significant improvements in data quality when using PMC compared to conventional retrospective correction alone:

Table 3: Quantitative Benefits of PMC in Resting-State fMRI

| Metric | No Intentional Motion | Large Motion (No PMC) | Large Motion (With PMC) | Improvement with PMC |

|---|---|---|---|---|