Validating Brain Signatures Across Multiple Cohorts: A Roadmap for Robust Biomarker Development in Neuroscience

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the development and validation of brain signatures as reliable biomarkers across independent cohorts—a critical step for their translation into clinical and research applications.

Validating Brain Signatures Across Multiple Cohorts: A Roadmap for Robust Biomarker Development in Neuroscience

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the development and validation of brain signatures as reliable biomarkers across independent cohorts—a critical step for their translation into clinical and research applications. We explore the foundational concepts of data-driven brain signatures and their evolution from theory-based approaches. The article details rigorous methodological frameworks, including multi-cohort discovery designs and machine learning applications, that enhance generalizability. It addresses common pitfalls in reproducibility and offers optimization strategies for handling cohort heterogeneity and data integration challenges. Finally, we present established validation protocols and comparative analyses demonstrating how validated multi-cohort signatures outperform traditional measures in explaining behavioral outcomes and predicting clinical status. This guide equips researchers and drug development professionals with practical strategies for creating neurologically informative and clinically actionable biomarkers.

The Foundation of Brain Signatures: From Theoretical Constructs to Data-Driven Discovery

In the pursuit of translating neurobiological insights into clinical applications, the field of cognitive neuroscience has increasingly embraced data-driven approaches to delineate robust brain-behavior relationships. The concept of a "brain signature" has emerged as a powerful paradigm, referring to a data-driven, exploratory approach to identify key brain regions most strongly associated with specific cognitive functions or behavioral outcomes [1]. Unlike theory-driven or lesion-based approaches that dominated earlier research, brain signatures aim to characterize brain substrates of behavioral outcomes through comprehensive exploratory searches that select features based solely on performance metrics of prediction or classification [2]. This methodological evolution has been catalyzed by the availability of larger datasets, improved computational resources, and high-quality brain parcellation atlases that enable more comprehensive mapping of brain-behavior associations [1].

Statistical Regions of Interest (sROIs or statROIs) represent a core implementation of the brain signature concept, providing an alternative to predefined anatomical atlas regions [1]. The fundamental advantage of this approach lies in its ability to detect associations that may cross traditional ROI boundaries, potentially recruiting subsets of multiple regions without using the entirety of any single region [1]. This property allows sROIs to more accurately reflect the underlying brain architecture supporting specific cognitive functions or affected by pathological processes. The clinical promise of this approach is substantial—by providing maximally informative biomarkers, validated brain signatures could enhance early diagnosis, improve prognostic accuracy, guide targeted interventions, and serve as endpoints in clinical trials for neurological and psychiatric disorders [2] [3].

Methodological Framework: Computational Approaches for Signature Derivation

Core Computational Techniques

The derivation of brain signatures employs diverse computational techniques ranging from voxel-wise parametric methods to multivariate machine learning algorithms. Voxel-aggregation approaches implement direct computation of voxel-based regressions with multiple comparison corrections to generate regional masks corresponding to different association strength levels with behavioral outcomes [2]. This method delineates 'non-standard' regions that may not conform to prespecified atlas parcellations but more accurately reflect relevant brain architecture. Machine learning techniques include support vector machines (SVM) for classification [3], relevant vector regression (RVR) for predicting continuous variables [1] [2], and deep learning using convolutional neural nets [1]. Additionally, multivariate pattern analysis methods leverage information distributed across multiple brain systems to provide quantitative, falsifiable predictions and establish mappings between brain and mind [4].

Table 1: Computational Techniques for Brain Signature Derivation

| Technique | Primary Use | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel-Wise Regression & Aggregation | Continuous outcomes | Creates non-atlas dependent regions; High interpretability | Computationally intensive for large datasets |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Binary classification | Effective for categorical outcomes; Handles high-dimensional data | Limited native probabilistic output |

| Relevant Vector Regression (RVR) | Continuous outcomes | Sparse solution; Probabilistic predictions | Model can be like a "black box" |

| Spatial Patterns of Abnormalities (SPARE) Framework | Disease severity indexing | Quantifies individual-level expression; Cross-validated | Requires large training datasets |

| Multivariate Information Theory | High-order interactions | Captures synergistic subsystems beyond pairwise correlations | Computationally complex; Emerging methodology |

Essential Methodological Considerations

Several methodological considerations are critical for deriving robust brain signatures. Feature selection must balance comprehensiveness with specificity, avoiding both overly restrictive anatomical constraints and uncontrolled multiple comparisons. Model interpretability remains challenging, particularly for complex machine learning approaches, though methods like layer-wise relevance propagation are emerging to address this "black box" problem [1]. Statistical validation requires rigorous approaches, including surrogate time series to assess coupling significance and bootstrap techniques to generate confidence intervals for individual estimates [5]. The level of analysis must also be considered—while pairwise functional connectivity has been valuable, high-order interactions (HOIs) investigating statistical interactions involving more than two network nodes may better capture the brain's functional complexity [5].

Validation Protocols: Ensuring Robustness and Generalizability

Multi-Cohort Validation Framework

Robust validation of brain signatures requires demonstrating replicability across multiple independent datasets beyond the discovery set where they were developed [1]. The validation protocol encompasses two key properties: model fit replicability (consistent performance in explaining outcome variance) and spatial extent replicability (consistent selection of signature regions across cohorts) [1]. A rigorous approach involves:

- Discovery in multiple subsets: Deriving regional brain associations in numerous randomly selected discovery subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of size 400) within each cohort [1].

- Consensus mask generation: Creating spatial overlap frequency maps and defining high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1].

- Independent validation: Evaluating replicability using completely separate validation datasets [1] [2].

- Performance comparison: Comparing signature model fits with each other and with competing theory-based models [1].

This protocol was successfully implemented in a 2023 study validating gray matter thickness signatures for memory domains, which demonstrated that consensus signature model fits were highly correlated across validation cohorts and outperformed other models [1].

Handling Population Heterogeneity

Population heterogeneity represents a significant challenge for brain signature validation. Demographic differences and other factors outside primary scientific interest can substantially impact predictive accuracy and pattern stability [6]. Evidence suggests that larger, more diverse cohorts often yield poorer prediction performance despite better representing true population diversity [6]. Propensity scores can serve as a composite confound index to quantify diversity arising from major sources of population variation [6]. Studies indicate that population heterogeneity particularly affects pattern stability in default mode network regions [6], highlighting the limitations of prevailing deconfounding practices and the need for explicit consideration of diversity in validation frameworks.

Experimental Protocols: From Signature Derivation to Application

Protocol 1: Voxel-Based Signature Derivation for Continuous Outcomes

This protocol details the derivation of brain signatures for continuous behavioral outcomes (e.g., cognitive test scores) using voxel-based methods:

- Image Processing: Process T1-weighted structural images through pipelines including brain extraction, tissue segmentation, and registration to standardized space [1] [2].

- Voxel-Wise Analysis: Perform whole-brain voxel-wise regression between gray matter measures and the behavioral outcome, correcting for multiple comparisons [2].

- Threshold Determination: Establish association strength thresholds based on statistical significance and spatial extent criteria [2].

- Region Aggregation: Aggregate significant voxels into contiguous regions, applying morphological operations to ensure spatial coherence [2].

- Mask Creation: Create binary masks representing the signature regions in standardized template space [2].

This approach has successfully generated replicable signatures for episodic memory performance in cohorts encompassing normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia [2].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Based Signature Derivation

This protocol outlines the use of machine learning for deriving brain signatures, as implemented in the SPARE (Spatial Patterns of Abnormalities for Recognition) framework [3]:

- Data Harmonization: Process and harmonize MRI data across multiple cohorts to minimize site effects [3].

- Feature Extraction: Extract comprehensive neuroimaging features from structural MRI, including regional volumes, cortical thickness, and white matter hyperintensities [3].

- Model Training: Train support vector classification models to distinguish between presence and absence of specific conditions using neuroimaging patterns [3].

- Pattern Expression Scoring: Compute individual expression scores for each participant, reflecting the degree to which their brain features match the signature pattern [3].

- Validation: Validate models in independent datasets and assess robustness across demographic subgroups [3].

This protocol has been successfully applied to derive signatures for various cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in cognitively unimpaired individuals [3].

Clinical Applications and Exemplary Findings

Validated Signatures Across Domains

Brain signature approaches have yielded robust, clinically relevant biomarkers across multiple domains:

Table 2: Exemplary Validated Brain Signatures and Their Characteristics

| Domain | Signature Basis | Key Brain Regions | Clinical Application | Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | Gray matter thickness | Medial temporal, precuneus, temporal regions [2] | Tracking cognitive decline in aging and early AD [2] | Validated across 3 independent cohorts [2] |

| Everyday Memory | Gray matter thickness | Strongly shared substrates with neuropsychological memory [1] | Assessing subtle functional changes in older adults [1] | Cross-validated in UCD and ADNI cohorts [1] |

| Social Inference | fMRI activation patterns | Right pSTS, TPJ, temporal poles, mPFC [7] | Predicting real-world social contacts; ASD assessment [7] | Validated in neurotypical and ASD samples [7] |

| Cardiovascular & Metabolic Risks | Structural MRI patterns | Frontal GM, insula, temporal regions [3] | Early risk detection in cognitively unimpaired [3] | Large multinational dataset (N=37,096) [3] |

| Preclinical AD | Glucose metabolism | Precuneus, posterior cingulate, temporal gyrus [8] | Ultra-early diagnosis in cognitively normal [8] | Cross-validated in Chinese and American cohorts [8] |

Performance Metrics and Effect Sizes

Quantitative performance assessments demonstrate the utility of validated brain signatures:

- Episodic memory signatures derived through voxel-aggregation approaches better explained baseline and longitudinal memory than theory-driven 'standard' models and other data-driven models [2].

- Cardiometabolic risk signatures developed using machine learning outperformed conventional structural MRI markers with a ten-fold increase in effect sizes and detected subtle patterns at sub-clinical stages [3].

- Social inference signatures predicted the number of real-life social contacts in neurotypical adults and autism symptom severity in ASD individuals, demonstrating generalization to neurodiverse populations [7].

- Preclinical AD metabolic patterns showed significant correlations with CSF tau biomarkers but not with amyloid deposition, suggesting sensitivity to downstream neurodegeneration [8].

Successful brain signature research requires specific data resources and analytical tools:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Brain Signature Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Key Utility | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Cohort Datasets | ADNI, UC Davis Aging and Diversity Cohort, UK Biobank, iSTAGING [1] [8] [3] | Provides diverse samples for discovery and validation | Data use agreements; Ethical approvals |

| Image Processing Pipelines | FreeSurfer, SPM, FSL, CNN-based extraction [1] [2] | Standardized feature extraction | Computational infrastructure requirements |

| Statistical Platforms | R, Python (scikit-learn, nilearn) [3] [6] | Implementation of machine learning models | Open-source with specific dependency packages |

| Validation Frameworks | Cross-validation utilities, permutation testing tools [7] [5] | Robust validation of signature performance | Custom implementation often required |

| Cloud Computing Resources | XSEDE, Google Cloud Platform, AWS [3] | Handles computational demands of large datasets | Cost and data transfer considerations |

Methodological Considerations for Implementation

When implementing brain signature research, several methodological considerations prove critical:

- Cohort Size and Diversity: Signatures derived from discovery sets numbering in the thousands demonstrate better replicability, with heterogeneous cohorts better representing true population variability [1] [6].

- Multisite Harmonization: When pooling data across multiple acquisition sites, implementing harmonization techniques is essential to mitigate site effects while preserving biological variability [3] [6].

- Statistical Power Considerations: Pitfalls of using undersized discovery sets include inflated strengths of associations and loss of reproducibility [1].

- Clinical Ground Truth: Precise phenotypic characterization and standardized behavioral assessment are crucial for meaningful signature development [1] [7].

The development of validated brain signatures represents a paradigm shift in neuroimaging research, moving from localized brain-behavior associations toward integrated, predictive models of mental events that leverage information distributed across multiple brain systems [4]. The methodological framework outlined—encompassing rigorous multi-cohort validation, sophisticated computational approaches, and attention to population heterogeneity—provides a roadmap for creating robust biomarkers with genuine clinical utility.

The most promising future directions include: (1) the integration of multimodal imaging data to capture complementary aspects of brain structure and function; (2) the development of dynamic signatures that track change over time; (3) the application of high-order interaction analyses to capture the complex, synergistic nature of brain networks [5]; and (4) the implementation of federated learning approaches to leverage large datasets while preserving privacy. As these methodologies mature and validation standards become more rigorous, brain signatures are poised to transition from research tools to clinically useful biomarkers, ultimately fulfilling their promise for precision medicine in neurology and psychiatry.

The Evolution from Theory-Driven to Data-Driven Exploratory Approaches

Human neuroimaging research has undergone a significant paradigm shift, transitioning from traditional brain mapping approaches toward developing integrated, multivariate brain models of mental events [9]. Traditional theory-driven methods analyzed brain-mind associations within isolated brain regions or voxels tested one at a time, treating local brain responses as outcomes to be explained by statistical models [9]. This approach was grounded in modular views of mental processes implemented in isolated brain regions, often informed by lesion studies [9]. In recent years, the "brain signature of cognition" concept has garnered interest as a data-driven, exploratory approach to better understand key brain regions involved in specific cognitive functions, with the potential to maximally characterize brain substrates of behavioral outcomes [1] [10]. This evolution represents a fundamental reorientation: where traditional approaches analyzed brain responses as outcomes, modern predictive models specify how to combine brain measurements to predict mental states and behavior [9].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Theory-Driven and Data-Driven Approaches

| Feature | Theory-Driven Approaches | Data-Driven Exploratory Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Modular view of mental processes [9] | Population coding and distributed representation [9] |

| Analysis Focus | Isolated brain regions/voxels [9] | Multivariate patterns across brain systems [9] |

| Primary Outcome | Local brain responses [9] | Behavioral and mental state predictions [1] |

| ROI Definition | Predefined anatomical or functional regions [1] | Data-driven statistical ROIs (sROIs) [1] |

| Validation Approach | Single-cohort hypothesis testing | Multi-cohort replicability and model fit [1] |

| Information Encoding | Assumed localized encoding | Distributed population coding [9] |

Theoretical Foundations and Advantages

Theoretical Underpinnings of Data-Driven Approaches

Data-driven exploratory approaches emerge from theories grounded in neural population coding and distributed representation [9]. Neurophysiological studies have established that information about mind and behavior is encoded in the activity of intermixed populations of neurons, where joint activity across cell populations often predicts behavior more accurately than individual neurons [9]. This distributed representation permits combinatorial coding, providing the capacity to represent extensive information with limited neural resources [9]. Multivariate modeling of how activity spanning many brain voxels jointly encodes behavioral outcomes represents an extension of these population coding concepts to human neuroimaging [9].

Advantages of Data-Driven Signature Approaches

Data-driven brain signature approaches offer several distinct advantages over traditional methods:

- Larger Effect Sizes: Multivariate models demonstrate larger effect sizes in brain-outcome associations than standard local region-based approaches [9].

- Quantitative Predictions: These models provide quantitative predictions about outcomes that can be empirically falsified, moving beyond descriptive mapping [9].

- Cross-Validation Capability: Models with defined measurement properties can be tested and validated across studies and laboratories [1] [10].

- Boundary Flexibility: Unlike predefined ROI approaches that may miss associations crossing ROI boundaries, signature approaches can detect subtle effects that recruit subsets of multiple regions [1].

- Interpretative Power: The approach offers a path toward validating mental constructs and understanding how psychological distinctions parallel neurological ones [9].

Quantitative Validation Metrics Across Cohorts

Rigorous validation across multiple cohorts is essential for establishing robust brain signatures. Recent research demonstrates the performance advantages of data-driven signature approaches when validated across independent datasets.

Table 2: Validation Metrics for Brain Signature Models Across Cohorts

| Validation Metric | Discovery Cohorts (UCD & ADNI 3) | Validation Cohorts (UCD & ADNI 1) | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 578 (UCD), 831 (ADNI 3) [1] | 348 (UCD), 435 (ADNI 1) [1] | Large samples enable replicability [1] |

| Discovery Subsets | 40 randomly selected subsets of size 400 [1] | 50 random subsets for replicability testing [1] | High replicability in validation subsets [1] |

| Spatial Convergence | Convergent consensus signature regions [1] | Spatial replication produced convergent regions [1] | High-frequency regions defined as consensus masks [1] |

| Model Fit Correlation | N/A | Highly correlated in validation subsets [1] | Indicates high replicability [1] |

| Explanatory Power | Signature models developed | Outperformed theory-based models in full cohorts [1] | Better explanatory power than competing models [1] |

Application Notes: Implementing Data-Driven Signature Methods

Protocol 1: Computing Robust Gray Matter Signatures for Behavioral Domains

Purpose: To compute data-driven brain signatures of behavioral domains (e.g., episodic memory, everyday cognition) that replicate across multiple cohorts.

Materials and Reagents:

- Structural T1-weighted MRI scans

- Gray matter thickness pipeline [1]

- Cognitive assessment batteries (e.g., SENAS, ADNI-Mem) [1]

- Everyday function measures (e.g., ECog) [1]

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Cohort Selection: Identify discovery and validation cohorts with appropriate sample sizes (N > 400 per cohort) [1].

- Image Processing:

- Cognitive Assessment: Administer standardized neuropsychological tests (e.g., episodic memory tests) and everyday function measures (e.g., ECog) [1].

- Discovery Phase:

- Validation Phase:

Troubleshooting:

- If discovery-validation bias appears, increase discovery sample size or number of random subsets [1].

- For poor spatial convergence, ensure cohort heterogeneity representing full variability in pathology and cognition [1].

Protocol 2: Identifying Endogenous Brain States Through Trial-Variability Clustering

Purpose: To discover endogenous brain state variability relevant to cognition using data-driven clustering of trial-level activity.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-density EEG system

- Behavioral task with multiple coherence levels (e.g., motion discrimination) [11]

- Modularity-maximization clustering algorithms [11]

- Computational modeling frameworks for decision thresholds [11]

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- EEG Acquisition: Collect high-density EEG data throughout task performance [11].

- Data-Driven Clustering:

- Behavioral Correlation:

- Computational Modeling:

Troubleshooting:

- If clusters do not separate cleanly, optimize modularity parameters or feature selection.

- For weak behavioral correlations, increase trial numbers or optimize task design.

Brain Signature Development and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structural MRI T1-weighted | High-resolution 3D sequences | Gray matter thickness measurement and voxel-based morphometry [1] |

| Cognitive Batteries | SENAS, ADNI-Mem, ECog | Standardized assessment of episodic memory and everyday function [1] |

| EEG Systems | High-density (64+ channels) | Recording spatial-temporal brain activity patterns during tasks [11] |

| Modularity-Maximization Clustering | Data-driven algorithm | Identifying consistent spatial-temporal EEG patterns across trials [11] |

| Voxel-Based Regression | Whole-brain analysis | Computing regional brain-behavior associations without predefined ROIs [1] |

| Computational Decision Models | Threshold adjustment frameworks | Interpreting behavioral differences between brain state subtypes [11] |

| Population Coding Frameworks | Theoretical foundation | Guiding multivariate analysis based on distributed neural representation [9] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The evolution from theory-driven to data-driven exploratory approaches represents a fundamental advancement in cognitive neuroscience methodology. Data-driven brain signatures offer robust, replicable measures for modeling substrates of behavioral domains, outperforming traditional theory-based models in explanatory power [1] [10]. The strength of these approaches lies in their ability to detect distributed patterns that cross traditional anatomical boundaries and their capacity for quantitative prediction and cross-validation [9].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas. First, addressing the interpretability challenges of complex multivariate models, particularly as machine learning and deep learning approaches become more prevalent [1]. Second, developing standardized protocols for multi-cohort validation to ensure robustness across diverse populations. Third, integrating multimodal data (fMRI, EEG, structural imaging) to create more comprehensive models of brain-behavior relationships [9]. Finally, establishing clearer connections between population coding principles from cellular neuroscience and distributed representations in human neuroimaging [9].

The paradigm shift toward data-driven exploratory approaches positions the field to develop increasingly accurate models of how distributed brain patterns represent mental constructs, ultimately advancing both basic neuroscience and clinical applications in drug development and personalized medicine.

The "brain signature of cognition" concept has garnered significant interest as a data-driven, exploratory approach to better understand key brain regions involved in specific cognitive functions [1]. This paradigm represents an evolution from theory-driven or lesion-driven approaches, offering the potential to more completely characterize brain substrates of behavioral outcomes by discovering statistical regions of interest (sROIs or statROIs) associated with specific cognitive domains [1]. The validation of robust brain signatures across multiple cohorts represents a critical advancement for neuroscience research and drug development, providing reliable measures for modeling the neuroanatomical substrates of behavioral domains.

For brain signatures to be considered robust biological measures, they require rigorous validation of model performance across diverse cohorts [1]. This includes demonstrating both spatial replicability (consistent identification of signature brain regions across discovery datasets) and model fit replicability (consistent explanatory power for behavioral outcomes in independent validation datasets) [1]. The emergence of large-scale neuroimaging datasets has enabled the development of signature approaches that can overcome limitations of earlier methods, which potentially missed subtler but significant effects in brain-behavior associations [1].

Domain-Specific Brain Signatures: Application Notes

Episodic Memory Signature

Episodic memory, the ability to encode, store, and retrieve personal experiences, has been a primary focus for brain signature development. Validation studies have employed neuropsychological assessments such as the Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales (SENAS) and the ADNI memory composite (ADNI-Mem) to quantify episodic memory performance [1]. These instruments are specifically designed to be sensitive to individual differences across the full range of episodic memory performance, from intact to impaired functioning.

Research has established that robust episodic memory signatures involve distributed brain networks rather than isolated regions. The validation of these signatures requires demonstrating that model fits to outcome are highly correlated across multiple random subsets of validation cohorts, indicating high replicability [1]. When properly validated, signature models for episodic memory have been shown to outperform other commonly used neuroanatomical measures in explanatory power [1].

Everyday Cognition Signature

Everyday cognition represents a crucial domain for assessing functional impact of cognitive changes, measured through informant-based scales such as the Everyday Cognition scales (ECog) [1]. The ECog is specifically designed to address functional abilities of older adults, focusing on subtle changes in everyday function spanning preclinical Alzheimer's disease to moderate dementia [1]. This domain captures clinically meaningful aspects of cognition that may not be fully apparent in traditional neuropsychological testing environments.

Studies comparing brain signatures for everyday memory (ECogMem) and neuropsychological memory have found strongly shared brain substrates, suggesting convergent validity across these assessment modalities [1]. The successful extension of the signature method to this behavioral domain illustrates its usefulness for discerning and comparing brain substrates across different behavioral domains [1].

Executive Function Considerations

While executive function represents another crucial brain-behavior domain, the provided search results focus primarily on memory-related domains. However, the methodological framework for developing and validating brain signatures can be extended to executive function measures, which typically assess higher-order cognitive processes including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control.

Table 1: Key Brain-Behavior Domains and Associated Assessment Measures

| Brain-Behavior Domain | Primary Assessment Measures | Population Applications | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | SENAS, ADNI-Mem | Cognitively diverse older adults | Sensitive across full performance range |

| Everyday Cognition | Everyday Cognition (ECog) scales | Preclinical AD to moderate dementia | Captures clinically meaningful function |

| Neuropsychological Memory | Composite list learning tests | General adult populations | Standardized quantitative metrics |

Experimental Protocols for Signature Validation

Multi-Cohort Validation Protocol

The validation of brain signatures requires a rigorous multi-cohort approach to ensure generalizability and robustness. The following protocol outlines the key steps for establishing validated brain signatures:

Discovery Cohort Selection: Identify multiple independent cohorts with appropriate sample sizes. Studies suggest samples in the thousands may be needed for optimal replicability, though smaller carefully selected cohorts can still yield meaningful results [1]. Example cohorts include the UC Davis Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Longitudinal Diversity Cohort (n=578) and Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Phase 3 (n=831) [1].

Feature Selection: Compute regional brain gray matter associations for behavioral outcomes of interest. Implement voxel-based regressions without predefined ROI boundaries to allow fully data-driven feature selection [1].

Consensus Mask Generation: Run multiple iterations (e.g., 40 randomly selected discovery subsets) to generate spatial overlap frequency maps. Define high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1].

Independent Validation: Evaluate replicability using separate validation datasets (e.g., additional participants from original cohorts or independent studies). Assess both spatial convergence and model fit to behavioral outcomes [1].

Performance Comparison: Compare signature model fits with competing theory-based models to establish explanatory superiority [1].

Neuroimaging Data Processing Protocol

Standardized image processing is essential for reproducible brain signature development. The following protocol details key processing steps:

Image Acquisition: Acquire high-quality T1-weighted structural MRI images using standardized sequences. For functional signatures, acquire resting-state or task-based fMRI sequences [12].

Preprocessing: Process images through established pipelines including:

Quality Control: Implement rigorous quality control procedures at each processing stage, including human review of automated processing outputs [1].

Feature Extraction: Extract gray matter thickness values or functional connectivity measures for signature development.

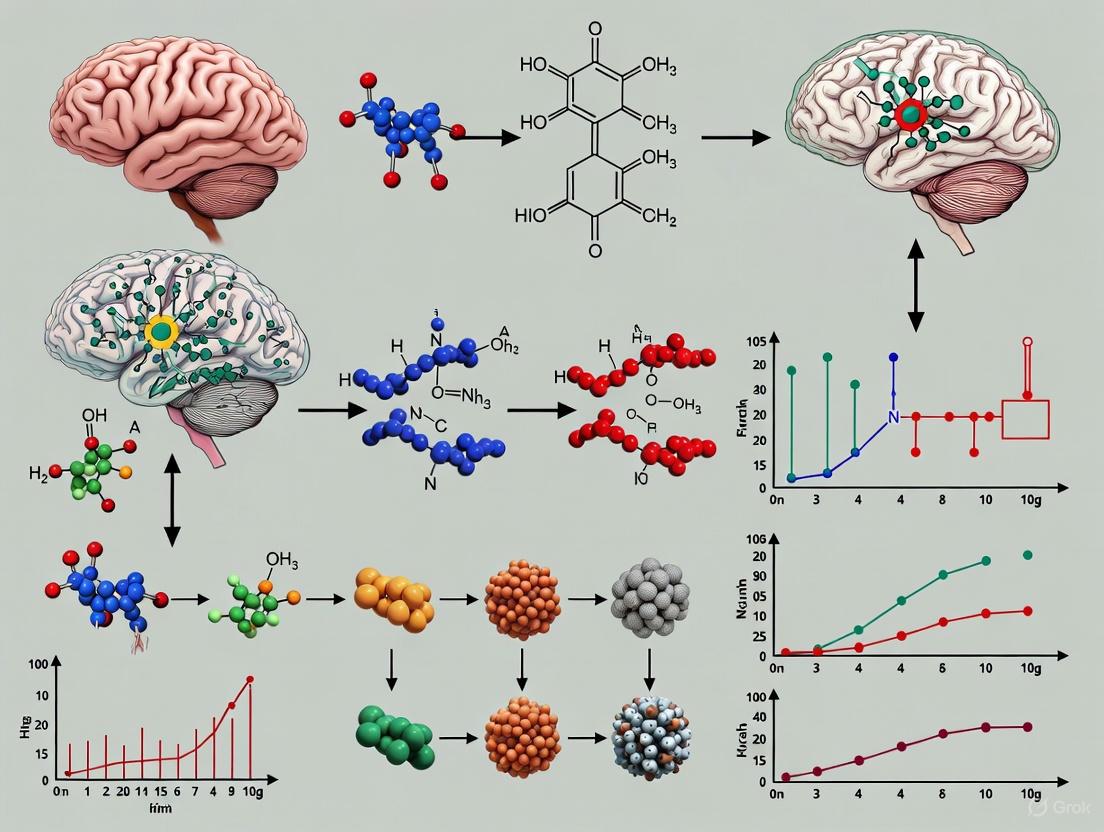

Figure 1: Brain Signature Validation Workflow

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Topological Data Analysis for Brain Dynamics

Beyond structural brain signatures, topological data analysis (TDA) represents an innovative framework for capturing individual differences in brain function. This approach characterizes the non-linear, high-dimensional structure of brain dynamics through persistent homology, identifying topological features such as loops and voids that describe how data points are organized in space and evolve over time [13].

The TDA protocol involves:

- Delay Embedding: Reconstruct one-dimensional time series into high-dimensional state space using optimal embedding dimensions and time delays [13].

- Persistent Homology Analysis: Perform 0-dimensional (H0) and 1-dimensional (H1) persistent homology analysis to extract topological features [13].

- Persistence Landscape Construction: Describe the birth and death of topological holes across different dimensions for analyzable feature sets [13].

Research has demonstrated that topological features exhibit high test-retest reliability and enable accurate individual identification across sessions [13]. In classification tasks, these features have outperformed commonly used temporal features in predicting gender and have shown significant associations with cognitive measures and psychopathological risks through canonical correlation analysis [13].

Machine Learning Considerations

Machine learning approaches represent powerful alternatives for developing brain-behavior models, with algorithms including support vector machines, support vector classification, relevant vector regression, and deep learning using convolutional neural nets [1]. However, these methods present distinct challenges for interpretation, as complex models can function as "black boxes" [1].

Key considerations for machine learning applications include:

- Overfitting Prevention: Implement rigorous cross-validation strategies and independent validation to prevent performance inflation [14].

- Confounding Control: Identify and mitigate confounding variables that can bias brain-behavior relationship examinations [14].

- Multisite Harmonization: Apply appropriate harmonization strategies to reduce unwanted variability in multisite datasets [14].

- Model Interpretability: Utilize post hoc interpretation methods to enhance model transparency while avoiding misinterpretation [14].

Table 2: Analytical Approaches for Brain-Behavior Signature Development

| Methodological Approach | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel-Based Signature | Data-driven voxel selection without predefined ROIs | Comprehensive brain coverage; avoids ROI boundary constraints | Requires large samples; multiple comparison challenges |

| Topological Data Analysis | Persistent homology to capture topological features | Robust to noise; captures non-linear dynamics | Computationally intensive; complex interpretation |

| Machine Learning | Multivariate pattern analysis; predictive modeling | High predictive power; handles complex relationships | Black box problem; risk of overfitting |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Brain Signature Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Assessment | SENAS, ADNI-Mem, Everyday Cognition (ECog) scales | Quantification of behavioral domains | Validation across cognitive ranges; sensitivity to change |

| Image Processing Software | In-house pipelines; established software packages | Structural and functional image analysis | Quality control procedures; standardized processing |

| Statistical Analysis Platforms | R, Python with specialized neuroimaging packages | Signature development and validation | Multivariate analysis; cross-validation capabilities |

| Data Harmonization Tools | ComBat; other cross-scanner harmonization methods | Multi-site data integration | Adjustment for scanner and site effects |

| Topological Analysis | Giotto-TDA toolkit | Persistent homology feature extraction | Delay embedding; persistence landscape construction |

The development of validated brain signatures for key behavioral domains represents a transformative approach in neuroscience with significant implications for drug development and clinical trial design. The rigorous multi-cohort validation framework ensures that resulting signatures are robust and generalizable, providing reliable neuroanatomical substrates for episodic memory, everyday cognition, and other behavioral domains.

Future directions in the field should include:

- Increased sample sizes and diversity to enhance generalizability [1]

- Multimodal approaches combining structural, functional, and topological features [13] [15]

- Advanced harmonization methods for multisite studies [14]

- Integration of genetic and environmental factors to comprehensively model brain-behavior relationships [15]

As these methodologies continue to evolve, validated brain signatures offer promising pathways for precision medicine approaches in neurology and psychiatry, enabling more targeted interventions and personalized treatment strategies based on individual neurocognitive profiles.

The Critical Need for Multi-Cohort Validation in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs), including Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), represent a significant and growing global health challenge, affecting over 57 million people worldwide [16]. These conditions are characterized by substantial heterogeneity in their clinical presentation and underlying pathology, which has consistently hampered the development of effective diagnostics and therapeutics. A predominant factor in the high failure rate of clinical trials is the limited generalizability of findings derived from single-cohort studies, which often fail to capture the full spectrum of disease variability across different populations. Multi-cohort validation has emerged as a critical methodological framework to address these challenges, enabling the identification of robust, reproducible biomarkers and signatures that transcend cohort-specific biases and technical variations. This approach is rapidly becoming the gold standard in neurodegenerative disease research, providing the statistical power and diversity necessary to accelerate the development of precision medicine approaches.

The Imperative for Multi-Cohort Approaches

Limitations of Single-Cohort Studies

Single-cohort studies are frequently limited by cohort-specific characteristics, including unique demographic distributions, recruitment strategies, clinical assessment protocols, and biospecimen handling procedures. These factors introduce biases that can lead to the identification of putative biomarkers that fail to replicate in independent populations [17]. Furthermore, the statistical power of single-cohort studies is often constrained by sample size limitations, particularly for less common neurodegenerative conditions such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD) or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The siloing of data among a fragmented research community has been a significant barrier to biomarker discovery, as many research institutions have historically maintained restricted access to their datasets [16].

Advantages of Multi-Cohort Validation

Multi-cohort analysis significantly enhances the robustness and generalizability of research findings by explicitly addressing and quantifying inter-cohort heterogeneity. By integrating data from multiple independent sources, researchers can distinguish consistently dysregulated biomarkers from those that are cohort-specific artifacts. A key demonstration of this principle comes from a PD cognitive impairment study, which found that multi-cohort models provided greater performance stability over single-cohort models while retaining competitive average performance [17]. Similarly, in AD research, a three-cohort cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) proteomics study identified a 10-protein signature that achieved exceptional predictive accuracy (AUC > 0.90) across independent validation sets [18]. This level of validation provides greater confidence in the potential clinical utility of such signatures.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Single vs. Multi-Cohort Machine Learning Models in Parkinson's Disease Cognitive Impairment Prediction

| Model Type | Prediction Task | Performance Metric | Performance Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cohort (LuxPARK) | PD-MCI Classification | Hold-out AUC | 0.70 | Highest performing single cohort |

| Single-Cohort (PPMI) | PD-MCI Classification | Hold-out AUC | 0.69 | Comparable performance |

| Multi-Cohort (Cross-cohort) | PD-MCI Classification | Hold-out AUC | 0.67 | Competitive performance with improved stability |

| Single-Cohort (PPMI) | Time-to-SCD Analysis | Hold-out C-index | 0.76 | Highest performing single cohort |

| Multi-Cohort (Cross-cohort) | Time-to-SCD Analysis | Hold-out C-index | 0.72 | Similar performance with greater robustness |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Cohort Studies

Protocol 1: Multi-Cohort Proteomic Analysis for Biomarker Discovery

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for identifying and validating protein biomarkers across multiple cohorts, based on established methodologies from recent large-scale consortia [16].

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

- Cohort Selection: Identify and collaborate with 3-5 independent cohorts with available biospecimens (plasma, CSF) and associated clinical data. Ensure diversity in geographic location, recruitment criteria, and demographic characteristics.

- Sample Processing: Use standardized SOPs for sample collection, processing, and storage across all sites. Aliquot samples to avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

- Proteomic Profiling: Utilize high-throughput proteomic platforms (e.g., SomaScan, Olink) to quantify protein levels. Include internal quality controls and inter-plate calibrators to monitor technical variability.

- Data Preprocessing: Perform normalization within and across batches using robust statistical methods (e.g., quantile normalization, ComBat). Implement rigorous quality control metrics to exclude poor-quality samples.

Statistical Analysis and Validation

- Discovery Phase: Conduct differential abundance analysis in the largest cohort (or meta-analyze across multiple discovery cohorts) using appropriate linear models, adjusting for key covariates (age, sex, technical factors).

- Replication Phase: Test significantly dysregulated proteins (FDR < 0.05) in independent replication cohorts using pre-specified statistical models.

- Meta-Analysis: Perform an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects or random-effects meta-analysis across all cohorts to obtain pooled effect estimates and assess heterogeneity (I² statistic).

- Machine Learning: Develop predictive models (e.g., LASSO regression) on the discovery set and validate on held-out cohorts. Assess performance using AUC, sensitivity, specificity.

Protocol 2: Multi-Cohort Transcriptomic Meta-Analysis

This protocol describes an integrated meta-analysis approach for identifying conserved transcriptional signatures across neurodegenerative diseases, adapted from a pioneering study that analyzed 1,270 post-mortem CNS tissue samples [19].

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Dataset Curation: Search public repositories (e.g., GEO, ArrayExpress) for gene expression datasets from neurodegenerative disease studies. Apply inclusion criteria: ≥5 cases and ≥5 controls, human post-mortem CNS tissue, genome-wide profiling.

- Data Harmonization: Log2-transform and quantile-normalize gene expression values for each dataset. Map microarray probes to standard gene symbols, resolving many-to-many relationships by creating additional records.

- Cohort Stratification: Divide datasets into discovery (smaller cohorts) and validation (larger cohorts) sets. Ensure representation of different CNS regions affected by each disease.

Meta-Analysis Execution

- Effect Size Calculation: Compute standardized mean differences (Hedge's adjusted g) for each gene in each dataset. For multiple probes mapping to the same gene, summarize effect sizes using fixed-effects inverse-variance model.

- Cross-Study Integration: Combine study-specific effect sizes using random-effects inverse-variance models to obtain pooled effect sizes and standard errors.

- Robustness Validation: Perform leave-one-disease-out analyses to identify genes consistently dysregulated across different combinations of neurodegenerative conditions.

- Functional Interpretation: Conduct pathway enrichment analysis, cell-type deconvolution, and upstream regulator prediction using established bioinformatics resources.

Table 2: Key Stages in Multi-Cohort Transcriptomic Meta-Analysis with Sample Sizes

| Stage | Description | Sample Size | Number of Cohorts | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Meta-Analysis | Initial integration of gene expression data | 1,270 samples | 13 patient cohorts | 243 differentially expressed genes |

| Leave-One-Disease-Out Analysis | Iterative exclusion of each disease | 1,270 samples | 13 patient cohorts | Common Neurodegeneration Module (CNM) |

| Independent Validation | Validation in larger cohorts | 985 samples | 3 patient cohorts | Confirmed conserved signature |

| Secondary Validation | Extension to additional diseases | 205 samples | 15 patient cohorts | Signature applicable to 7 neurodegenerative diseases |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful multi-cohort studies require standardized reagents and platforms to ensure comparability across sites and datasets. The following table outlines essential research reagents and their applications in multi-cohort neurodegenerative disease research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Cohort Neurodegeneration Research

| Reagent/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SomaScan Assay | Proteomic Platform | High-throughput protein quantification (7,029 analytes) | CSF proteomic analysis across Knight ADRC, FACE, ADNI cohorts [20] |

| Olink Proximity Extension Assay | Proteomic Platform | Multiplex protein quantification with high specificity | Plasma proteomic profiling in GNPC consortium [16] |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Clinical Assessment | Cognitive screening and mild cognitive impairment detection | Predictor of cognitive impairment in PD multi-cohort study [17] |

| Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (JLO) | Neuropsychological Test | Visuospatial ability assessment | Key predictor for PD-MCI in multi-cohort analysis [17] |

| MDS-UPDRS Parts I-IV | Clinical Rating Scale | Comprehensive assessment of Parkinson's disease symptoms | Motor and non-motor predictor integration in PD models [17] |

| OMOP Common Data Model | Data Standardization Framework | Harmonization of observational data across different sources | Cohort data management system interoperability [21] |

Case Studies in Multi-Cohort Validation

The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC)

The GNPC represents a paradigmatic example of large-scale multi-cohort collaboration, establishing one of the world's largest harmonized proteomic datasets for neurodegenerative diseases [16]. This public-private partnership includes approximately 250 million unique protein measurements from multiple platforms from more than 35,000 biofluid samples (plasma, serum, and CSF) contributed by 23 partners. The consortium has established a secure cloud-based environment (AD Workbench) for data access and analysis, addressing critical challenges in data siloing and harmonization. The GNPC has successfully identified disease-specific differential protein abundance patterns and transdiagnostic proteomic signatures of clinical severity that are reproducible across different neurodegenerative conditions. Particularly notable is the discovery of a robust plasma proteomic signature of APOE ε4 carriership that is consistent across AD, PD, FTD, and ALS, suggesting shared biological pathways influenced by this major genetic risk factor.

Multi-Cohort CSF Proteomics in Alzheimer's Disease

A landmark three-stage multi-cohort study of CSF proteomics in AD exemplifies the power of this approach for biomarker discovery [18]. The analysis employed a rigorous design with distinct discovery (Knight ADRC and FACE cohorts, n=1,170), replication (ADNI and Barcelona-1 cohorts, n=593), and validation (Stanford ADRC, n=107) phases. This study identified 2,173 analytes (2,029 unique proteins) dysregulated in AD, of which 1,164 (57%) were novel associations. Machine learning approaches applied to this data yielded highly accurate and replicable models (AUC > 0.90) for predicting AD biomarker positivity and clinical status. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that proteomic changes in AD follow four distinct pseudo-trajectories across the disease continuum, with specific pathway enrichments at different stages: neuronal death and apoptosis (early stages), microglia dysregulation and endolysosomal dysfunction (mid-stages), brain plasticity and longevity (mid-stages), and microglia-neuron crosstalk (late stages).

Cross-Disease Transcriptional Meta-Analysis

An integrated multi-cohort transcriptional meta-analysis of neurodegenerative diseases revealed conserved molecular pathways across distinct clinical conditions [19]. The study analyzed 1,270 post-mortem CNS tissue samples from 13 patient cohorts covering four neurodegenerative diseases (AD, PD, HD, and ALS), with validation in an additional 15 cohorts (205 samples) including seven neurodegenerative diseases. This approach identified 243 differentially expressed genes that were similarly dysregulated across multiple conditions, with the signature correlating with histologic disease severity. The analysis highlighted pervasive bioenergetic deficits, M1-type microglial activation, and gliosis as unifying themes of neurodegeneration. Notably, metallothioneins featured prominently among the differentially expressed genes, and functional pathway analysis identified specific convergent themes of dysregulation. The study also demonstrated how removal of genes common to neurodegeneration from disease-specific signatures revealed uniquely robust immune response and JAK-STAT signaling in ALS, illustrating the power of this approach to distinguish shared from distinct disease mechanisms.

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Cohort Data Management Systems (CDMS)

Effective multi-cohort research requires sophisticated data management infrastructure. Modern Cohort Data Management Systems (CDMS) must address both functional requirements (data collection, processing, analysis) and non-functional requirements (flexibility, security, usability) [21]. These systems facilitate cohort studies through comprehensive data operations, secure access controls, user engagement features, and interoperability with other research platforms. Key considerations include:

- Data Harmonization: Implementation of common data models (e.g., OMOP CDM) and standardized terminologies to enable cross-cohort analyses.

- Privacy and Security: Adherence to regulatory frameworks (GDPR, HIPAA) through de-identification, access controls, and audit trails.

- Interoperability: Support for integration with electronic health records, multi-omics platforms, and analysis tools through API-based architectures.

- Scalability: Capacity to handle exponentially increasing data volumes from digital health technologies and high-throughput molecular profiling.

Analytical Considerations

Robust multi-cohort analysis requires careful attention to methodological challenges:

- Cross-Study Normalization: Application of appropriate batch correction methods (e.g., ComBat, cross-study normalization) to address technical variability while preserving biological signals [17].

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Quantification of between-cohort heterogeneity using metrics such as I² statistics, with application of random-effects models when substantial heterogeneity is present.

- Stratified Analysis: Exploration of sex-specific, ancestry-specific, and disease-stage-specific effects through pre-specified subgroup analyses.

- Confounding Control: Standardized adjustment for key demographic and clinical variables across cohorts to enhance comparability.

Multi-cohort validation represents a transformative approach in neurodegenerative disease research, directly addressing the challenges of disease heterogeneity and limited reproducibility that have plagued the field. Through the integration of diverse, independent datasets, researchers can distinguish robust, generalizable biomarkers from cohort-specific artifacts, accelerating the development of clinically applicable tools. The establishment of large-scale consortia such as the GNPC, together with standardized protocols for cross-cohort analysis and data management, provides a foundational framework for future discoveries. As the field advances, multi-cohort approaches will be increasingly essential for the development of precision medicine strategies that can deliver the right intervention to the right patient at the right time, ultimately transforming the prognosis for millions affected by these devastating conditions.

Methodological Frameworks: Building Robust Signatures with Machine Learning and Multi-Cohort Designs

Application Notes: The Role of Multi-Cohort Designs in Validating Brain Signatures

Rationale and Scientific Foundation

Multi-cohort discovery designs have emerged as a critical methodology in neuroscience research to address critical limitations of single-cohort studies, including limited generalizability, cohort-specific biases, and reduced statistical power. These designs enable researchers to develop and validate robust brain signatures—data-driven patterns of brain structure or function that serve as reliable biomarkers for cognitive status, disease progression, and treatment response. By leveraging multiple independent cohorts, researchers can distinguish consistent neurobiological patterns from cohort-specific artifacts, producing findings that translate across diverse populations and clinical settings [1] [22].

The validation of brain signatures across multiple cohorts represents a paradigm shift from theory-driven approaches to data-driven discovery of brain-behavior relationships. This approach leverages high-dimensional data from neuroimaging, cognitive assessments, and biomarkers to identify complex patterns that may not be evident through hypothesis-testing alone. As noted in recent research, "The 'brain signature of cognition' concept has garnered interest as a data-driven, exploratory approach to better understand key brain regions involved in specific cognitive functions, with the potential to maximally characterize brain substrates of behavioral outcomes" [1]. This methodological evolution has been facilitated by the growing availability of large-scale, multimodal datasets from international consortia and advances in computational power and machine learning algorithms.

Key Advantages and Applications

Multi-cohort designs offer several distinct advantages over traditional single-cohort studies. They significantly enhance the robustness and generalizability of findings by testing associations across diverse populations with varying recruitment criteria, measurement protocols, and demographic characteristics. These designs improve statistical power for detecting subtle but consistent effects by combining data across multiple sources. They also enable the identification of cohort-invariant biological patterns that reflect core disease processes rather than cohort-specific characteristics. Furthermore, multi-cohort designs facilitate the development of comprehensive disease models by integrating complementary variables measured across different studies [23] [22].

The applications of multi-cohort designs in brain signature validation span multiple domains: early detection and risk stratification for neurodegenerative diseases, tracking disease progression and treatment response, parsing heterogeneity within clinical syndromes, and providing robust endpoints for clinical trials. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that a "Union Signature" derived from multiple behavioral domains showed stronger associations with clinical outcomes than traditionally used brain measures and excelled at classifying clinical syndromes across the cognitive normalcy-to-dementia spectrum [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cohort Selection and Data Harmonization

Cohort Selection Criteria: The foundation of a successful multi-cohort study lies in the strategic selection of complementary datasets. Ideal cohorts should have: (1) clearly defined diagnostic criteria consistently applied across all participants (e.g., NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer's disease); (2) sufficient sample sizes per diagnostic group (typically >10 participants per group, though larger samples are preferred); (3) multimodal data collection encompassing imaging, clinical, cognitive, and biomarker assessments; and (4) diversity in recruitment strategies and population characteristics to enhance generalizability [23] [24].

Data Harmonization Protocols: Cross-cohort data harmonization is a critical step that requires meticulous attention to technical and methodological variability. Key harmonization procedures include: (1) imaging data processing through standardized pipelines (e.g., FreeSurfer for volumetric measures, DiReCT for gray matter thickness); (2) cross-study normalization to adjust for scanner and protocol differences; (3) cognitive score harmonization using equating procedures or factor analysis; and (4) covariate adjustment for demographic and clinical variables [1] [25]. The normalization of volumetric measures should account for intracranial volume differences using the formula: VRa = VR/tICV * mean(tICV), where VRa is the adjusted volume, VR is the raw volume, and tICV is total intracranial volume [25].

Table 1: Exemplar Cohorts for Multi-Cohort Brain Signature Research

| Cohort Name | Primary Focus | Sample Characteristics | Key Data Modalities | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADNI [26] [27] | Alzheimer's disease biomarkers | 229 normal, 398 MCI, 192 AD (baseline) [24] | MRI, PET, CSF biomarkers, genetics, cognitive tests | LONI IDA repository with data use agreement [27] |

| UCD ADRC [22] | Diverse cognitive aging | 946 normal, 418 MCI, 140 dementia (diverse ethnic/racial composition) | Structural MRI, cognitive tests, clinical assessments | Requires institutional approval and data use agreement |

| MCR Consortium [25] | Motoric cognitive risk | N=1987 across 6 international cohorts | Gait measures, volumetric MRI, cognitive tests | Collaborative consortium approval required |

| LuxPARK [17] | Parkinson's disease cognitive impairment | Luxembourgish PD cohort with cognitive assessments | Clinical measures, cognitive tests, motor assessments | Requires individual cohort data use agreements |

Brain Signature Discovery and Validation Workflow

The validation of brain signatures through multi-cohort designs follows a rigorous multi-stage process that emphasizes generalizability and robustness at each step.

Discovery Phase Protocol:

- Feature Selection: Identify candidate brain features (e.g., voxel-wise gray matter thickness, regional volumes) associated with behavioral outcomes of interest. Use whole-brain exploratory analyses without pre-specified regions of interest to avoid confirmation bias.

- Multi-Subset Discovery: Generate 40+ randomly selected subsets (n=400 each) from the discovery cohort to compute regions of interest significantly associated with the behavioral outcome in each subset [1] [22].

- Consensus Mask Creation: Calculate voxel-wise overlaps across discovery subsets. Define "consensus" signature regions as those appearing in at least 70% of discovery subsets, ensuring robustness against sampling variability [22].

- Initial Model Building: Develop predictive models using machine learning algorithms (e.g., gradient boosting, regularized regression) that incorporate the identified signature regions.

Validation Phase Protocol:

- Cross-Cohort Validation: Test the discovered signatures in completely independent validation cohorts that were not used in the discovery phase. This assesses generalizability across different populations and measurement protocols.

- Performance Benchmarking: Compare signature performance against theory-based models (e.g., hippocampal volume for memory) and established biomarkers using metrics such as AUC for classification, C-index for time-to-event analysis, and R² for continuous outcomes [17] [22].

- Clinical Utility Assessment: Evaluate the signature's ability to predict clinically relevant outcomes such as conversion from MCI to dementia, functional decline, or treatment response.

Multi-Cohort Machine Learning Protocol: For predictive model development across multiple cohorts, the following protocol has demonstrated efficacy:

- Data Integration: Combine data from multiple cohorts while preserving cohort identities to account for systematic differences.

- Cross-Cohort Normalization: Apply harmonization methods to minimize technical variability while preserving biological signals.

- Algorithm Selection: Implement machine learning methods suitable for multi-cohort data, such as mixed-effects models, domain adaptation techniques, or ensemble methods that account for cohort heterogeneity.

- Explainable AI (XAI) Integration: Incorporate interpretability methods such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to identify robust predictors across cohorts and enhance clinical translatability [17].

Diagram 1: Multi-Cohort Brain Signature Validation Workflow

Statistical Validation Framework

Robust validation of brain signatures requires a comprehensive statistical framework that addresses both model performance and spatial reproducibility:

Model Fit Replicability:

- Evaluate signature-outcome associations across multiple random subsets (50+)

- Test correlation of model fits between discovery and validation cohorts

- Assess performance stability across cross-validation cycles [1]

Spatial Extent Replicability:

- Quantify overlap between signature regions identified in different cohorts

- Calculate spatial correlation metrics (e.g., Dice coefficient)

- Identify consistently engaged neural systems across cohorts [1]

Performance Metrics:

- For classification tasks: AUC, sensitivity, specificity, precision

- For survival analysis: C-index, time-dependent AUC

- For continuous outcomes: R², mean squared error, correlation coefficients [17]

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Multi-Cohort Studies

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event-Based Modeling [23] | Probabilistic event sequences, Meta-sequence aggregation | Disease staging, Biomarker ordering | Handles partially overlapping variables across cohorts |

| Machine Learning [17] | Gradient boosting, Regularized regression, Explainable AI (SHAP) | Prediction of conversion, Cognitive decline | Requires careful cross-cohort normalization |

| Signature Discovery [22] | Voxel-wise regression, Consensus masking, Union signatures | Brain-behavior mapping, Multi-domain assessment | Balances discovery and validation sample sizes |

| Clustering Methods [25] | HYDRA (Heterogeneity through Discriminative Analysis) | Disease subtyping, Heterogeneity analysis | Uses reference population to control for normal variation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Multi-Cohort Brain Signature Research

| Resource Category | Specific Resources | Function/Purpose | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | ADNI (LONI IDA) [26] [27] | Primary data source for Alzheimer's disease biomarkers | Online application with data use agreement [27] |

| Analysis Platforms | FreeSurfer, FSL, SPM, CAT12 | Image processing and volumetric analysis | Open-source or licensed software packages |

| Computational Tools | Python (scikit-learn, nilearn, PyTorch), R (brainGraph, ebmc) | Machine learning, statistical analysis, signature development | Open-source programming languages and libraries |

| Validation Frameworks | Cross-validation, leave-one-cohort-out, bootstrap aggregation | Robustness assessment, generalizability testing | Implemented in statistical software environments |

| Consortium Data | MCR Consortium [25], ADNI, UCD ADRC, LuxPARK [17] | Multi-cohort validation, increased sample diversity | Varied access procedures from open to restricted |

Case Studies and Empirical Evidence

Multi-Cohort Validation of Parkinson's Disease Cognitive Impairment Signatures

A recent large-scale study demonstrated the power of multi-cohort designs by integrating data from three independent Parkinson's disease cohorts (LuxPARK, PPMI, and ICEBERG) to develop machine learning models predicting cognitive impairment. The study found that multi-cohort models showed greater performance stability over single-cohort models while retaining competitive average performance (hold-out AUC 0.67 for PD-MCI classification). Key predictors included age at diagnosis and visuospatial ability, with significant sex differences observed in cognitive impairment patterns. The study highlighted that "multi-cohort models provided more stable performance statistics than single-cohort models across cross-validation cycles," demonstrating the value of incorporating diverse populations to improve model robustness and reduce cohort-specific biases [17].

Event-Based Modeling Across Alzheimer's Disease Cohorts

A comprehensive analysis of ten independent AD cohort studies revealed both consistency and variability in event-based model sequences derived from different datasets. The average pairwise Kendall's tau correlation coefficient across cohorts was 0.69 (±0.28), indicating general consistency but also notable variability mainly in the positioning of imaging variables. The researchers developed a novel rank aggregation algorithm to combine partially overlapping event sequences into a meta-sequence that integrated complementary information from each cohort. The resulting meta-sequence aligned with current understanding of AD progression, starting with CSF amyloid beta abnormalities, followed by tauopathy, memory impairment, FDG-PET changes, and ultimately brain atrophy and visual memory deficits. This approach demonstrated that "aggregation of data-driven results can combine complementary strengths and information of patient-level datasets" to create more comprehensive disease models [23].

Union Signature Development for Multiple Cognitive Domains

A groundbreaking study developed a "Union Signature" derived from four behavior-specific brain signatures (neuropsychological and informant-rated memory and executive function). This generalized signature demonstrated stronger associations with clinical outcomes than traditionally used brain measures and excelled at classifying clinical syndromes. The Union Signature's associations with episodic memory, executive function, and Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes were stronger than those of several standardly accepted brain measures (e.g., hippocampal volume, cortical gray matter) and other previously developed brain signatures. The study concluded that "the Union Signature is a powerful, multipurpose correlate of clinically relevant outcomes and a strong classifier of clinical syndromes," highlighting the potential of data-driven approaches to discover brain substrates that explain more variance in clinical outcomes than theory-guided measures [22].

Diagram 2: Multi-Cohort Analytical Approaches and Signature Outcomes

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Methodological Challenges and Solutions

Cohort Heterogeneity: Variability in recruitment criteria, measurement protocols, and population characteristics across cohorts can introduce systematic biases. Solution: Implement robust normalization procedures, use mixed-effects models to account for cohort-level variance, and explicitly test for cohort-by-predictor interactions [17] [23].

Missing Data: Different cohorts typically collect partially overlapping sets of variables. Solution: Apply appropriate missing data methods (e.g., multiple imputation), develop models using only commonly assessed variables, or use meta-analytic approaches that combine results from different variable sets [23].

Computational Complexity: Multi-cohort analyses involve large, heterogeneous datasets that require substantial computational resources. Solution: Utilize high-performance computing infrastructure, implement efficient algorithms, and consider distributed computing approaches [1] [22].

Reproducibility: Ensuring that findings replicate across cohorts requires careful methodological planning. Solution: Pre-register analysis plans, implement rigorous cross-validation schemes, and use independent cohorts for discovery and validation [1].

Optimization Strategies

- Sample Size Planning: Balance between cohort diversity and statistical power—include enough cohorts to ensure generalizability but maintain sufficient sample size within each cohort for reliable estimation.

- Variable Selection: Prioritize variables that are measured consistently across cohorts and have established reliability and validity.

- Validation Sequence: Use a stepped validation approach—first within-cohort cross-validation, then between-cohort validation, and finally validation in completely independent datasets.

- Clinical Translation: Engage clinical stakeholders throughout the process to ensure that identified signatures have practical utility and align with clinical decision-making needs.

The implementation of multi-cohort discovery designs represents a significant advancement in neuroscience methodology, addressing critical limitations of single-cohort studies while leveraging the complementary strengths of diverse datasets. As research in this area continues to evolve, these approaches promise to yield more robust, generalizable, and clinically meaningful brain signatures that enhance our understanding of brain-behavior relationships and improve patient care across neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Within the evolving paradigm of precision medicine, the development of robust, biologically grounded biomarkers is paramount. The concept of a "brain signature of cognition" has garnered significant interest as a data-driven, exploratory approach to identify key brain regions associated with specific cognitive functions or disease states, offering the potential to maximally characterize the brain substrates of behavioral and clinical outcomes [1]. However, for such signatures to transition from research tools to clinically viable biomarkers, they must demonstrate robust validation across diverse, independent cohorts. A critical methodological challenge lies in moving beyond signatures derived from single cohorts or simplistic analyses, which often fail to generalize. This Application Note details a refined protocol for consensus signature development, leveraging spatial overlap frequency and aggregation techniques to create neuroanatomical signatures that are reproducible, reliable, and capable of outperforming theory-based models [1] [10]. This methodology is framed within a broader thesis on cross-cohort validation, providing a foundational technique for ensuring that brain signatures are not merely artifacts of a particular dataset but represent consistent biological phenomena.

Core Principles and Definitions

A brain signature is a multivariate pattern derived from neuroimaging data (e.g., gray matter thickness, white matter hyperintensities) that is systematically associated with a behavioral domain (e.g., episodic memory), clinical status (e.g., Alzheimer's disease), or a specific risk factor (e.g., hypertension) [1] [3]. The signature approach represents an evolution from theory-driven or lesion-driven approaches, aiming to provide a more complete accounting of complex brain-behavior relationships.

The transition to a consensus signature involves a deliberate shift from single-cohort discovery to multi-source evidence aggregation. The core principle is that a robust signature should be identifiable across numerous randomly selected subsets of a discovery cohort. Regions that consistently appear across these subsets are considered part of a "consensus" signature mask, thereby enhancing generalizability and mitigating the pitfalls of overfitting and bias inherent in single-dataset discovery [1]. This process is fundamentally based on analyzing the spatial overlap frequency of features (e.g., voxels, regions of interest) associated with the outcome of interest, defining consensus regions as those that exceed a pre-defined frequency threshold [1].

Computational Protocols

Workflow for Consensus Signature Generation

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for developing a consensus signature, from data preparation through to final validation.

Detailed Methodological Steps

Step 1: Repeated Subsampling of Discovery Cohorts

- Objective: To ensure the signature is not dependent on a specific sample composition.

- Protocol: From each discovery cohort, generate a large number (e.g., 40) of random subsets without replacement. The subset size (e.g., n=400) should be chosen to be large enough for stable estimation but small enough to allow for numerous iterations [1].

- Rationale: This step directly addresses population heterogeneity, a major factor affecting the predictive accuracy of brain imaging [6]. It allows for the assessment of a signature's stability across variations in sample makeup.

Step 2: Voxel-wise Association Analysis

- Objective: To identify brain regions associated with the target outcome within each subset.

- Protocol: For each subsample, perform a mass-univariate or multivariate analysis relating the neuroimaging variable (e.g., gray matter thickness) to the outcome (e.g., memory score). This can be implemented using voxel-based regressions or machine learning algorithms like support vector machines [1].

- Output: For each of the 40 subsets, a statistical map (e.g., t-map, beta-map) indicating the strength and direction of association for every voxel.

Step 3: Generation of Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps

- Objective: To quantify the spatial consistency of associations across all subsamples.

- Protocol:

- Thresholding: Convert each statistical map from Step 2 into a binary map by applying a significance threshold (e.g., p < 0.01, FDR-corrected).

- Aggregation: Sum all binary maps across the 40 subsets. This creates a single frequency map where the value at each voxel represents the number of subsamples in which it was significantly associated with the outcome.

- Output: A 3D frequency map where voxel intensities range from 0 to the total number of subsamples (e.g., 40).

Step 4: Consensus Mask Definition

- Objective: To define the final set of regions constituting the consensus signature.

- Protocol: Apply a frequency threshold to the map from Step 3. For instance, only voxels that are significant in more than 70% of the subsamples (e.g., >28 out of 40) are retained. This threshold can be determined empirically or via cross-validation [1].

- Output: A binary "consensus signature mask" that identifies the most robustly associated brain regions.

Validation Framework

The validation of a consensus signature is a multi-faceted process, as depicted in the workflow. The core activities in this phase are detailed below.

Step 6 & 7: Model Fit Evaluation and Comparison

- Objective: To rigorously test the performance and utility of the consensus signature in independent data.

- Protocol:

- Replicability of Model Fits: Apply the consensus signature to 50 random subsets of the validation cohort. High correlation of the signature's model fit (e.g., R²) across these subsets indicates high replicability [1].

- Explanatory Power Comparison: Test whether the consensus signature model explains significantly more variance in the outcome variable than competing theory-based models (e.g., those based on pre-defined regions from the literature) in the full validation cohort [1].