Validating Virtual Reality Social Paradigms for Autism Research: From Foundational Theory to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation process for Virtual Reality (VR) social interaction paradigms in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research.

Validating Virtual Reality Social Paradigms for Autism Research: From Foundational Theory to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation process for Virtual Reality (VR) social interaction paradigms in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational theory behind VR's applicability for ASD, detailing methodological approaches for creating controlled social scenarios. The content addresses key technical and design challenges, including physiological synchronization and user safety, and critically examines validation strategies and comparative efficacy against traditional methods. By synthesizing evidence from recent systematic reviews and clinical feasibility studies, this article establishes a framework for developing robust, ecologically valid VR tools that can enhance therapeutic outcomes and serve as sensitive endpoints in clinical trials.

The Theoretical Basis: Why VR is a Transformative Tool for Autism Social Research

The validation of virtual reality (VR) social interaction paradigms represents a significant advancement in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, offering methodologies that address fundamental limitations of traditional approaches. VR-based interventions provide core strengths—malleability, controllability, and safe practice environments—that enable researchers to create ecologically valid yet tightly controlled experimental conditions. These technological advantages allow for the precise targeting of social communication deficits that characterize ASD, supporting both intervention and fundamental research into social functioning mechanisms. This guide objectively examines the experimental evidence supporting VR's efficacy in ASD research, comparing its performance against traditional alternatives and detailing the methodological protocols that ensure scientific rigor.

Core Strength 1: Malleability of Virtual Environments

The malleability of VR systems enables researchers to dynamically modify environmental stimuli, social scenarios, and task complexity in response to individual participant needs and research objectives. This adaptability spans multiple dimensions critical to autism research.

Customizable Social Scenarios

VR platforms allow for the creation of diverse social situations that can be tailored to specific research hypotheses. Studies have successfully developed scenarios ranging from basic emotional recognition tasks to complex social interactions like conversational turn-taking and understanding non-literal language [1]. This customizability enables researchers to systematically manipulate variables of interest while maintaining control over confounding factors.

Individualized Sensory Profiles

A critical application of VR malleability lies in adapting sensory inputs to accommodate the unique sensory processing profiles of individuals with ASD. Research indicates that the multi-perceptibility of VR systems allows for the graduated exposure to sensory stimuli, which can be calibrated in real-time based on participant response [2]. This capacity for individualization supports the investigation of sensory integration theories in ASD within controlled yet adaptable environments.

Table 1: Applications of VR Malleability in ASD Research

| Malleability Feature | Research Application | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario Customization | Testing social cue recognition | Virtual characters with programmable facial expressions and vocal tones [1] |

| Sensory Adjustment | Investigating sensory processing | Modifiable visual, auditory, and tactile inputs in virtual environments [2] |

| Difficulty Progression | Measuring skill acquisition | Incrementally complex social tasks with adaptive challenge levels [3] |

| Cultural Contextualization | Examining cross-cultural social cognition | Culturally-specific social scenarios for diverse participant populations [2] |

Core Strength 2: Controllability of Experimental Parameters

The controllability of VR environments provides researchers with unprecedented precision in manipulating and maintaining experimental conditions, addressing fundamental methodological challenges in ASD research.

Precision in Variable Manipulation

VR systems enable exacting control over social stimuli presentation, allowing researchers to isolate specific variables for systematic investigation. This controllability supports rigorous experimental designs that can establish causal relationships between intervention components and outcomes. The replicability of VR environments ensures consistent stimulus presentation across participants and research sites, enhancing methodological reliability [1]. A meta-analysis of intelligent interaction technology found that the controlled nature of VR interventions contributed to significant effect sizes (SMD=0.66, 95% CI: 0.27-1.05, p<0.001) in ASD interventions [4].

Standardization of Research Protocols

The programmable nature of VR systems facilitates the implementation of standardized research protocols across diverse settings. This consistency is particularly valuable in multi-site trials and longitudinal studies, where maintenance of identical experimental conditions is methodologically essential. Research indicates that VR-based studies can maintain protocol fidelity through automated presentation of stimuli and systematic data collection [3].

Core Strength 3: Safe Practice Environments for Social Skill Development

The capacity of VR to create safe practice environments addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional ASD interventions by providing low-risk settings for social skill development.

Anxiety Reduction Through Controlled Exposure

VR environments mitigate the anxiety typically associated with social interaction for individuals with ASD by offering predictable, repeatable social scenarios. Research demonstrates that the safe, controllable nature of virtual spaces lowers perceived anxiety levels, enabling participants to engage in social learning without the overwhelming stressors of real-world interactions [1]. This controlled exposure aligns with theoretical frameworks such as social motivation theory, which suggests that reduced anxiety facilitates increased engagement with social stimuli [2].

Error-Friendly Learning Spaces

The consequence-free nature of VR environments allows participants to experiment with social strategies and learn from mistakes without real-world social repercussions. This capacity is particularly valuable for practicing complex social skills such as emotion recognition, conversational reciprocity, and social inference. Studies indicate that this error-tolerant learning approach leads to improved generalization of skills to real-world contexts [3] [5].

Table 2: Comparative Outcomes: VR Interventions vs. Traditional Approaches

| Outcome Measure | VR Intervention Results | Traditional Intervention Results | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Skill Improvement | Significant positive effects (HFA: complex skills; LFA: basic skills) [6] | Variable effects depending on method and delivery | VR shows targeted efficacy based on functioning level |

| Behavioral Regulation | ABC score reduction: Adjusted mean difference = -5.67, 95% CI [-6.34, -5.01], partial η² = 0.712 [2] | Moderate improvements typically observed | VR demonstrates large effect sizes in controlled trials |

| Autism Symptom Severity | CARS reduction: Adjusted mean difference = -3.36, 95% CI [-4.10, -2.61], partial η² = 0.408 [2] | Gradual improvement over extended periods | VR shows significant reduction in core symptom measures |

| Caregiver Satisfaction | 95.2% satisfaction rate in VR groups vs. 82.3% in traditional interventions [2] | Generally positive but limited by accessibility | VR offers higher acceptability among stakeholders |

| Skill Generalization | Improved transfer to real-world settings reported in multiple studies [3] [7] | Generalization often limited without explicit programming | VR shows promising generalization patterns |

Experimental Evidence and Research Protocols

Key Research Findings from Clinical Studies

Recent controlled studies provide compelling evidence for VR efficacy in ASD interventions. A retrospective cohort study with 124 children with ASD compared fully immersive VR (FIVR) combined with psychological and behavioral intervention against traditional approaches alone [2]. After three months, the FIVR group demonstrated significantly greater improvements on standardized measures, including the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), with large effect sizes (partial η² = 0.712 and 0.408, respectively). Similarly, PEP-3 total scores were significantly higher in the FIVR group (adjusted mean difference = 8.21), particularly in language and adaptive behavior domains [2].

A systematic review of 14 studies concluded that VR interventions positively impact social skills in children and adolescents with ASD, with particularly pronounced effects on complex social skills in individuals with high-functioning autism (HFA) [6]. Those with low-functioning autism (LFA) showed progress primarily in basic skills, suggesting the need for functionality-specific intervention approaches.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol represents a synthesized methodology from recent high-quality VR-ASD studies:

Participant Recruitment and Matching:

- Sample: 124 children with ASD (age range: 2-15 years), diagnosed using standardized instruments [2]

- Matching: 1:1 manual matching based on age (±1 year), gender, disease duration, and initial ASD severity (CARS and ABC scores)

- Design: Retrospective cohort study with experimental and control groups

VR Intervention Parameters:

- Hardware: Head-mounted displays (HMDs) for fully immersive VR

- Software: Customizable virtual environments developed using platforms such as Unity 2021.3 LTS [5]

- Session Structure: 3-month intervention period with standardized frequency and duration

- Content: Graduated social scenarios with adaptive difficulty progression

Assessment Methodology:

- Primary Measures: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), Psychoeducational Profile-third edition (PEP-3)

- Secondary Measures: Caregiver satisfaction surveys, behavioral observation coding

- Timing: Pre-test, post-test, and (in some studies) follow-up assessments

- Analysis: ANCOVA adjusted for baseline covariates, reporting of effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for VR-ASD Studies

| Research Component | Representative Examples | Function in VR-ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs), Oculus Rift/Quest, HTC Vive [1] | Provide immersive visual and auditory experiences; enable user interaction with virtual environments |

| Software Development Frameworks | Unity 3D, OpenXR runtime, Python 3.10 for data logging [5] | Create customizable virtual environments; implement experimental protocols; collect performance data |

| Assessment Instruments | Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), Psychoeducational Profile-3 (PEP-3) [2] | Standardized measurement of core ASD symptoms and intervention outcomes; enable cross-study comparisons |

| Behavioral Coding Systems | Automated tracking of gaze patterns, response times, and social initiations [3] | Objective quantification of behavioral responses; measurement of subtle changes in social engagement |

| Data Analysis Tools | STATA for random-effects models, G*Power for sample size calculation [4] [5] | Statistical analysis of intervention effects; power analysis for research design; meta-analytic synthesis |

The core strengths of VR—malleability, controllability, and safe practice environments—establish it as a transformative methodology for ASD research with robust experimental support. Quantitative evidence demonstrates significant advantages across multiple domains, including social skill acquisition, behavioral regulation, and reduction of core ASD symptoms. The methodological rigor of VR-based protocols, characterized by precise environmental control and standardized assessment, addresses longstanding challenges in autism intervention research.

Future research directions should prioritize longitudinal studies examining skill maintenance, investigation of individual difference variables predicting treatment response, and development of more sophisticated adaptive algorithms that respond in real-time to participant performance. Additionally, further exploration of the neural mechanisms underlying VR-mediated learning in ASD populations would strengthen theoretical frameworks. As VR technology continues to advance, its integration with artificial intelligence and physiological monitoring promises to further enhance its research utility, potentially offering new insights into the social-cognitive processes in autism spectrum disorder.

Virtual Reality (VR) is emerging as a transformative tool in autism research, creating controlled, safe, and customizable environments for teaching social skills. For researchers and clinicians, VR offers a unique paradigm to address the core social attention impairments in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), from foundational skills like joint attention to nuanced complex social scenarios [8]. This technology shows particular promise due to its ability to provide repeatable social practice, minimize overstimulating sensory inputs, and offer immediate feedback in a structured setting [9] [8]. The validation of these VR paradigms is crucial for establishing standardized, evidence-based interventions that can bridge the gap between laboratory research and real-world application, potentially offering scalable solutions to complement traditional therapy [10].

The following analysis compares the performance of different VR technological approaches, presents quantitative outcomes, details experimental methodologies, and outlines the essential toolkit for conducting rigorous research in this field.

Comparative Analysis of VR Intervention Performance

Research indicates that intelligent interactive technologies, particularly those based on Extended Reality (XR), show significant efficacy in ASD interventions. The table below summarizes key performance data from recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Table 1: Overall Efficacy of Intelligent Interactive Interventions for ASD

| Intervention Category | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Primary Supported Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligent Interaction (Overall) | 0.66 | 0.27 - 1.05 | < 0.001 | Social, Cognitive, Behavioral [4] |

| Extended Reality (XR) | 0.80 | 0.47 - 1.13 | - | Social, Cognitive, Behavioral [4] |

| Robotic Systems | Inconclusive | High Heterogeneity | - | - |

Subgroup analyses reveal that participant age and target skills significantly influence outcomes. The most pronounced effects are observed in preschool-aged children, suggesting a critical window for intervention [4].

Table 2: Efficacy of VR Interventions by Age Group and Target Skill

| Factor | Subgroup | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Preschool (2-6 years) | 1.00 | p = 0.007 [4] |

| School-aged & Adolescents | Variable | - | |

| Intervention Target | Joint Attention | Positive trend | Supported by pilot studies [9] |

| Social Communication & Emotion Recognition | Positive outcomes | Improved eye contact, empathy, conversation [8] | |

| Cognitive Skills | Significant effect | - |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of VR-based social attention research, adherence to detailed experimental protocols is essential. The following workflows are derived from cited, peer-reviewed studies.

Protocol for Joint Attention Intervention

A pilot study investigating the feasibility of a VR joint attention module for school-aged children with ASD provides a robust methodological template [9].

Table 3: Key Components of the Joint Attention Intervention Protocol

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Participants | 12 participants, aged 9-16 years, with ASD [9]. |

| Technology | Mobile VR platform (Floreo) pairing a user's headset with a monitor's tablet [9]. |

| Intervention | Training with the Joint Attention Module [9]. |

| Dosage | 14 sessions over 5 weeks [9]. |

| Primary Outcome Measures | - Feasibility/Tolerability: Monitor-reported data on headset tolerance and participant enjoyment [9].- Skill Change: Pre-post scoring on a joint attention measure assessing total interactions, eye contact, and initiations [9]. |

| Safety Monitoring | Recording of adverse effects (e.g., cybersickness) and dropout rates [9]. |

The study reported high tolerability (95.4%), enjoyment (95.4%), and valuable experiences (95.5%), with preliminary data suggesting improvements in joint attention skills [9].

Protocol for VR-Motion Serious Game Intervention

A randomized controlled trial utilized an interactive VR-Motion serious game to enhance social willingness and self-living ability [5].

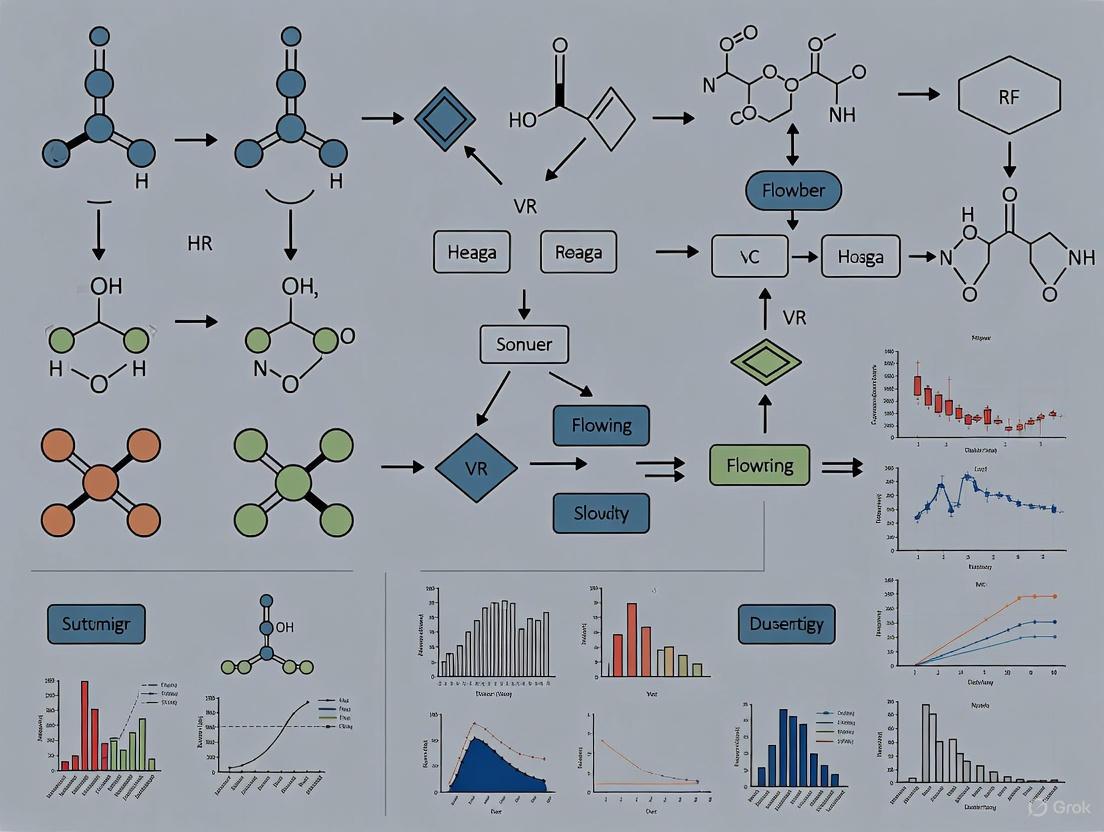

Diagram 1: VR Game Study Workflow

- Game Design: Participants chose an animal to care for (e.g., feeding, walking), with tasks requiring pedal-powered energy input from a stationary bicycle [5].

- Social Integration: The game encouraged social expansion by having the virtual animal bring friends home, designed to help children overcome social fears [5].

- Role of Therapist: A teacher or therapist assisted by releasing tasks, providing prompts, and increasing communication during gameplay [5].

- Experimental Parameters:

The results (df=9; t=-1.155; p=0.281) indicated a positive improvement in the social willingness of the children in the experimental group [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Implementing a rigorous VR intervention study requires a suite of technological and assessment tools. The table below catalogs key solutions referenced in the literature.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Autism Studies

| Item Category | Specific Example / Specification | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platform | Meta Quest (with Horizon OS) | Provides a standalone, commercially available HMD with integrated tracking [11]. |

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Mobile VR (e.g., Google Cardboard), Oculus Rift | Creates an immersive experience; level of immersion varies by device [9] [10]. |

| Software Development Kit (SDK) | Meta XR Interaction SDK (for Unity/Unreal) | Streamlines development of VR interactions (grabbing, pointing, UI raycasts) [11]. |

| UI Component Library | Horizon OS UI Set (for Figma/Unity) | Provides pre-built, native UI components (buttons, sliders) to ensure consistency and reduce development time [11]. |

| Game Engine | Unity 2021.3 LTS | The software environment for building and rendering the virtual environment and gameplay logic [5]. |

| Input & Tracking Devices | Cadence-sensor stationary bicycle | Translates real-world physical activity into in-game energy, promoting engagement and physical movement [5]. |

| Data Acquisition & Analysis | STATA, Python 3.10 scripts | Performs statistical analysis (e.g., random-effects meta-analysis) and data logging [4] [5]. |

| Standardized Assessment | Custom Joint Attention Measure | Quantifies changes in core skills like eye contact, initiations, and response to bids for attention [9]. |

The collective evidence from recent meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and clinical trials validates VR as a promising paradigm for addressing social attention impairments in individuals with ASD. The quantitative data demonstrates measurable efficacy, particularly for XR-based interventions targeting preschool-aged children. The established experimental protocols provide a framework for future rigorous research, while the outlined toolkit offers a starting point for assembling necessary resources.

Future work should focus on overcoming current limitations, including small sample sizes, lack of long-term follow-up data, and the critical need to demonstrate generalization of skills to real-world social contexts [8]. Standardizing outcome measures across studies will also be vital for comparing results and drawing definitive conclusions about the clinical benefits of specific VR approaches [10].

A significant challenge in autism research is the replicability of social interventions from controlled settings to the complex, unpredictable nature of the real world. Virtual Reality (VR) technology presents a paradigm shift, offering a bridge across this gap by enabling the creation of standardized, yet ecologically valid, social simulations. For children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), deficits in social skills—such as interpreting social cues, understanding emotions, and maintaining social relationships—can lead to increased social isolation and diminished quality of life [12]. Traditional interventions, while beneficial, are often hampered by high costs, limited accessibility, and an inability to provide consistent, repeatable practice in lifelike scenarios [12]. VR technology addresses these limitations by providing a safe, controlled environment where individuals with ASD can practice social interactions without real-world pressures [12]. This article objectively compares the efficacy of different VR technological approaches in simulating key real-world contexts—specifically classrooms and public transport—for autism research, providing a detailed analysis of experimental data and methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of VR Platforms and Modalities

The effectiveness of a VR intervention is heavily influenced by the choice of technology. The primary modalities—categorized as immersive and non-immersive VR—cater to different needs and populations within the autism spectrum [12]. Furthermore, the design of user interfaces and cognitive aids within these environments is critical for usability and learning outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of VR Modalities for Social Context Simulation

| Feature | Immersive VR | Non-Immersive VR |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Uses head-mounted displays (HMDs) to fully engage the user's senses in a virtual world [12]. | Experienced through traditional computer screens, offering a window into the virtual environment [12]. |

| Best Suited For | Individuals with High-Functioning Autism (HFA); training of complex social skills [12]. | Individuals with Low-Functioning Autism (LFA); interventions focused on basic social skills [12]. |

| Effectiveness | Shows particularly significant effects on the enhancement of complex social skills in HFA [12]. | Progress is mainly observed in basic skills for children and adolescents with LFA [12]. |

| Cost & Flexibility | Higher cost; requires specialized hardware [12]. | Lower cost and greater flexibility, suitable for everyday educational settings [12]. |

| Example Context | A multi-step journey on public transport requiring situational awareness and quick decision-making. | A basic classroom interaction, such as recognizing a teacher's request. |

The design of the virtual environment itself is paramount. Evidence from VR driving simulators demonstrates that the type of cognitive aid integrated into the system significantly impacts user performance. A study investigating aids for trainee drivers found that image-arrow aids (combining arrows, images, and short text) led to superior outcomes compared to audio-textual or arrow-textual aids alone [13]. The group using image-arrow aids achieved a lower mean error rate (8.1, SD=1.23) and faster mean completion time (3.26 minutes, SD=0.56) [13]. This principle translates directly to social simulations; well-designed visual cues can guide users toward correct social responses without causing cognitive overload.

Usability heuristics, such as Jakob Nielsen's 10 principles, are equally critical for VR design. Key considerations for social context simulations include [14]:

- Visibility of system status: The environment must clearly communicate what is happening to foster trust and predictability.

- Match between system and the real world: Interactions should build on users' existing mental models of social situations.

- Recognition rather than recall: On-screen prompts and labels should minimize memory load, a crucial factor for users who may struggle with executive function.

- Aesthetic and minimalist design: Interfaces should be free of unnecessary clutter to avoid distraction and sensory overload, a common challenge for individuals with ASD.

Quantitative Outcomes: Efficacy Data from Social Simulations

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate the positive effect of VR interventions on the social skills of children and adolescents with ASD. A systematic review of 14 studies concluded that VR technology has a positive effect on improving these skills, with the level of functionality on the autism spectrum being a key moderating factor [12] [15]. The following table summarizes the core quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 2: Efficacy Outcomes of VR Social Skills Interventions for ASD

| Outcome Measure | High-Functioning Autism (HFA) | Low-Functioning Autism (LFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Benefit | Enhancement of complex social skills [12]. | Progress in basic social skills [12]. |

| Suitability of VR Modality | Immersive VR is more suitable for training complex skills [12]. | Non-immersive VR is more appropriate for basic skill interventions [12]. |

| Reported Adverse Effects | Potential for dizziness, eye fatigue, and sensory overload, particularly in immersive settings [12]. | Generally lower risk of adverse effects due to less immersive nature of recommended technology [12]. |

Beyond autism-specific research, studies in health care education show that VR simulation allows students to prepare for complex clinical situations in a safe environment, training soft skills like communication, decision-making, and critical thinking [16]. The learning is significantly enhanced when the VR experience is coupled with a structured debriefing and group discussion, which helps solidify social and emotional learning [16].

Experimental Protocols for VR Social Context Research

To ensure the validity and replicability of findings, researchers must adhere to rigorous experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines a standardized methodology for conducting studies on VR-based social simulations, synthesized from multiple research efforts.

Core Experimental Workflow

The diagram above illustrates a robust experimental workflow for validating VR social paradigms. Key phases include:

- Participant Profiling: The population must be children and adolescents (aged 3-18) with a reliable ASD diagnosis. Crucially, participants should be categorized by their functioning level (HFA or LFA) at this stage, as this is a major predictive factor for outcomes [12] [15].

- Intervention Phase: The VR intervention itself should be structured. It begins with a briefing to prepare the user, followed by exposure to the target social scenario (e.g., a classroom or a bus ride). The session must conclude with a guided debriefing; research confirms that debriefing sessions are a vital part of the learning process that enhances active involvement and conceptual change [16].

- Measurement and Analysis: Studies should employ validated tools or methodologies to assess social competence before and after the intervention (pre-test/post-test) [12]. The analysis should then compare outcomes not just between control and experimental groups, but also between sub-groups like HFA and LFA.

Building and evaluating effective VR social simulations requires a suite of specialized tools and resources. The following table details key components for a research toolkit in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Social Simulation Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function in Research | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Provides the hardware platform for immersive VR experiences. | Oculus Quest series [14]. Displays must be calibrated for color accuracy and comfort [17]. |

| 360-Degree Video Cameras | Creates live-action, immersive scenarios for VR simulation. | Used in health care education to create realistic, non-interactive scenarios for soft skills training [16]. |

| Game Engines | Software environment to build and render interactive, 3D virtual social scenarios. | Unity [13]. Allows for the programming of social interactions and integration of cognitive aids. |

| Validated Social Skills Assessments | Standardized metrics to quantitatively measure intervention outcomes. | Pre-test and post-test tools are required to assess social competence [12]. The specific tool should be chosen for the target skill and population. |

| Usability Evaluation Framework | Assesses the user experience, cognitive load, and potential side effects of the VR system. | Adapted heuristics for VR [14], questionnaires (e.g., RIMMS for motivation [18]), and monitoring for cybersickness [16]. |

| Cognitive Aids Library | Pre-designed visual or auditory elements that guide user behavior and learning within the VR environment. | Image-arrow aids, iconic cues, or textual hints proven to improve performance and understanding [13]. |

The body of evidence confirms that VR technology is a powerful tool for bridging the replicability gap in autism social skills research. The key to its efficacy lies in matching the technological modality to the individual's needs—utilizing immersive VR for complex skill training in HFA and non-immersive VR for basic skills in LFA. The systematic integration of rigorous experimental protocols, robust usability principles, and effective cognitive aids is fundamental for creating valid and reliable social simulations of environments like classrooms and public transport.

Future research should focus on optimizing individualized interventions and further exploring the long-term effects of VR-based social training [12]. As the technology evolves, so too must the research paradigms, continually enhancing the ecological validity of these virtual worlds to ensure the skills learned within them seamlessly transfer to the enriching complexity of everyday life.

The Role of Immersion and Presence in Eliciting Ecologically Valid Social Behaviors

The validation of Virtual Reality (VR) social interaction paradigms for autism research represents a critical frontier in both clinical neuroscience and neurodevelopmental studies. An essential tension exists between researchers interested in ecological validity and those concerned with maintaining experimental control [19]. Research in human neurosciences often involves simple, static stimuli lacking important aspects of real-world activities and interactions. VR technologies proffer assessment paradigms that combine the experimental control of laboratory measures with emotionally engaging background narratives to enhance affective experience and social interactions [19]. This review examines how immersion and presence serve as foundational mechanisms for creating ecologically valid social environments, with particular application to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) research, where the transfer of learned skills to real-world contexts remains a significant challenge.

Theoretical Foundations: Ecological Validity in Virtual Environments

Defining Ecological Validity in Clinical Neuroscience

The concept of ecological validity has been refined for neuropsychological assessment through two primary requirements: (1) Veridicality, where performance on a construct-driven measure should predict features of day-to-day functioning, and (2) Verisimilitude, where the requirements of a neuropsychological measure and testing conditions should resemble those found in a patient's activities of daily living [19]. Traditional construct-driven measures like the Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST) were developed to assess cognitive constructs without regard for their ability to predict functional behavior [19]. In contrast, a function-led approach to neuropsychological assessment proceeds from directly observable everyday behaviors backward to examine how sequences of actions lead to given behaviors in normal functioning, and how those behaviors might become disrupted [19].

Immersion and Presence: Conceptual Distinctions

A crucial distinction exists between immersion as the technical capability of a system that allows a user to perceive the virtual environment through natural sensorimotor contingencies, and presence as the subjective experience of actually being inside the virtual environment [20]. Slater and colleagues further delineate two important components of presence: (1) Place illusion, the illusion of "being there" in the virtual environment, and (2) Plausibility, the feeling that the depicted scenario is really occurring [20]. A consequence of place illusion and plausibility is that users behave in VR as they would do in similar circumstances in reality, which is of paramount importance for VR training and assessment [20].

The Relationship Between Presence and Ecological Behavior

Considerable work has demonstrated VR's ability to elicit behavioral responses to virtual environments, even when participants are well aware the environment isn't "real" [21]. The sense of presence enables individuals to exhibit emotions and behaviors similar to those in real-world contexts [22]. This phenomenon is particularly valuable for ASD research, where individuals often struggle with generalization—the ability to transfer learned skills to new settings [22]. IVR addresses these limitations by creating realistic and immersive scenarios that mimic real-world conditions, facilitating skill generalization [22].

Table 1: Key Definitions for Immersion and Ecological Validity in VR Research

| Term | Definition | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Validity | The degree to which research findings can be generalized to real-world settings | Ensures laboratory assessments predict real-world functioning |

| Immersion | The technical capability of a system to provide virtual environment perception through natural sensorimotor contingencies | Objective feature of the VR system hardware and software |

| Presence | The subjective experience of "being there" in the virtual environment | Psychological state crucial for eliciting naturalistic behaviors |

| Place Illusion | The specific illusion of being located in the virtual environment | Contributes to behavioral authenticity in responses |

| Plausibility | The belief that the depicted scenario is really occurring | Enhances emotional engagement and task investment |

Experimental Evidence: Efficacy of VR Social Training Paradigms

Meta-Analytic Findings on Intelligent Interaction Technologies

A recent meta-analysis based on trial assessments evaluated the effectiveness of intelligent interaction technology in autism interventions, including Extended Reality (XR) and robotic systems [4]. The analysis included 13 studies involving 459 individuals with ASD from different regions (age range: 2-15 years). The results demonstrated that intelligent interactive intervention showed significant efficacy (SMD=0.66, 95% CI: 0.27-1.05, p < 0.001) [4]. Subgroup analyses revealed that XR interventions exhibited particularly positive effects (SMD=0.80, 95% CI: 0.47-1.13), while robotic interventions showed high heterogeneity and wider confidence intervals [4]. The most pronounced positive impacts were observed in preschool-aged children (2-6 years; SMD=1.00, p = 0.007) and cognitive interventions [4].

IVR Training for Adaptive Skills in ASD

A pilot study examining immersive virtual reality (IVR) training for adaptive skills in children and adolescents with high-functioning ASD demonstrated promising results [22]. Thirty-three individuals with ASD (ages 8-18) received weekly one-hour IVR training sessions completing 36 tasks across four key scenarios: subway, supermarket, home, and amusement park [22]. The system integrated a treadmill with headset and handheld controllers, allowing participants to physically walk within the virtual environment, enhancing realism and immersion [22].

The study reported significant improvements in IVR task scores (5.5% improvement, adjusted P = 0.034) and completion times (29.59% decrease, adjusted P < 0.001) [22]. Parent-reported measures showed a 43.22% reduction in ABC Relating subscale scores (adjusted P = 0.006) and moderate reductions in executive function challenges [22]. The training demonstrated high usability with an 87.9% completion rate and no severe adverse effects, though some participants reported mild discomforts including dizziness (28.6%) and fatigue (25.0%) [22].

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes from IVR Training in ASD Research

| Outcome Measure | Result | Statistical Significance | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVR Task Performance | 5.5% improvement in scores | Adjusted P = 0.034 | Statistically significant improvement in core task performance |

| Task Efficiency | 29.59% decrease in completion time | Adjusted P < 0.001 | Substantial improvement in processing speed and task efficiency |

| Social Functioning | 43.22% reduction in ABC Relating subscale | Adjusted P = 0.006 | Meaningful improvement in social interaction capabilities |

| Executive Function | Moderate reductions in BRIEF indices | Adjusted P = 0.020 (Behavioral Regulation), P = 0.019 (Metacognition) | Improved behavioral regulation and planning abilities |

| Usability | 87.9% completion rate | N/A | High feasibility and acceptability of the intervention |

Mechanisms of Change: Awe and Empathy in Immersive Environments

Research on eliciting pro-environmental behavior with immersive technology provides insights into psychological mechanisms relevant to social behaviors. A lab experiment using an immersive simulation of a degraded mountain environment found that specific design factors can evoke self-transcendent responses [23]. Specifically, informational prompts were found to elicit empathy with nature, while 360° control elicited both awe and empathic responses [23]. Awe directly influenced pro-environmental behaviors, whereas empathy with nature had a positive effect mediated by perceived consumer effectiveness [23]. These findings suggest that immersive technologies can activate specific affective states that drive behavioral outcomes, with potential applications for social skills training in ASD.

Methodological Protocols for VR Social Paradigm Validation

A Framework for Testing and Validation of Simulated Environments

To ensure VR social interaction paradigms generate ecologically valid behaviors, rigorous testing and validation frameworks are essential [20]. A proposed taxonomy includes multiple subtypes of fidelity and validity that must be established during simulation design [20]. Physical fidelity refers to the degree to which the virtual environment looks, sounds, and feels like the target environment, while functional fidelity concerns the degree to which the virtual environment behaves like the target environment, including how actions are performed and how the environment responds [20]. Psychological fidelity addresses the degree to which the skills, knowledge, and cognitive processes required in the simulation match those required in the real task [20].

Design Considerations for Immersive Virtual Environments

A systematic review of immersive virtual environment design for human behavior research identified key categories and proposed strategies that should be considered when deciding on the level of detail for prototyping IVEs [21]. These include: (1) the appropriate level of visual detail in the environment, including important environmental accessories, realistic textures, and computational costs; (2) contextual elements, cues, and animations for social interactions; (3) social cues, including computer-controlled agent-avatars when necessary and animating social interactions; (4) self-avatars, navigation concerns, and changes in participants' head directions; and (5) nonvisual sensory information, including haptic feedback, audio, and olfactory cues [21].

Heydarian and Becerik-Gerber describe "four phases of IVE-based experimental studies" with best practices for consideration in different phases [21]. The development of experimental procedure (Phase 2) includes the design and setup of the IVEs, especially considerations involving the level of detail required, which may differ between studies and can include visual appearance, behavioral realism, and virtual human behavior [21].

For social interaction paradigms in autism research, specific methodological considerations include:

Gradual Exposure Hierarchy: Similar to Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) protocols used for anxiety disorders, social scenarios should be structured according to a fear hierarchy, allowing customization according to each individual's specific needs [24].

Multimodal Stimulus Presentation: Research in human neurosciences increasingly uses cues about target states in the real world via multimodal scenarios that involve visual, semantic, and prosodic information presented concurrently or serially [19].

Contextual Embedding: Contextually embedded stimuli can constrain participant interpretations of cues about a target's internal states, enhancing ecological validity [19].

Real-time Performance Feedback: IVR systems allow for automated logging of responses and can provide real-time feedback to participants, enhancing learning and skill acquisition [22].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Social Interaction Paradigms

| Tool/Resource | Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Provide immersive visual and auditory experience through dual small screens and stereo headphones | Primary hardware for creating sense of presence in virtual environments [24] [21] |

| Motion Tracking Systems | Track user movements and adjust visual perspective in response | Enable natural sensorimotor contingencies critical for immersion [24] |

| Treadmill Integration | Allow physical walking within virtual environment toward any direction | Enhance realism and immersion in scenarios requiring extensive movement [22] |

| Data Gloves/Haptic Feedback | Provide tactile sensory input through vibration or resistance | Engage multiple senses to intensify sense of realism and enable object manipulation [24] |

| Virtual Agent Platforms | Computer-controlled characters with programmed social responses | Enable controlled social interactions for standardized assessment and training [21] |

| Biometric Monitoring | Record physiological responses (heart rate, skin conductance) during VR tasks | Provide objective measures of emotional and physiological arousal [23] |

| Automated Logging Systems | Record behavioral responses, reaction times, and task performance | Enable precise measurement of behavioral outcomes without researcher interference [19] [22] |

The integration of immersion and presence principles in VR social interaction paradigms offers significant potential for enhancing ecological validity in autism research. Evidence from meta-analyses and experimental studies indicates that immersive technologies, particularly extended reality (XR) systems, can elicit authentic social behaviors and facilitate transfer of learning to real-world contexts [4] [22]. The successful implementation of these paradigms requires rigorous validation approaches that address multiple dimensions of fidelity and validity, with particular attention to the specific needs of the ASD population [20]. Future research should focus on standardized protocols for establishing ecological validity, personalized immersion approaches based on individual sensory profiles, and longitudinal studies examining long-term transfer effects. As VR technologies continue to advance, their role in creating ecologically valid assessment and intervention platforms for social communication challenges in ASD appears increasingly promising.

Building Valid Paradigms: Methodological Approaches and System Design

Virtual Reality (VR) social interaction paradigms represent a transformative methodological shift in autism research, moving from traditional observer-based assessments to immersive, controlled, and quantifiable social simulations. These paradigms enable researchers to systematically investigate social communication deficits core to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) while maintaining the experimental control necessary for rigorous scientific inquiry. The evolution from basic emotion recognition tasks to complex bidirectional conversation scenarios marks significant progress in how researchers can capture the dynamic, interactive nature of real-world social functioning. This guide compares the experimental performance, methodological frameworks, and practical implementations of three dominant VR social scenario types emerging in contemporary autism research: emotion recognition training, adaptive skill acquisition, and bidirectional conversation tasks. Each paradigm offers distinct advantages for specific research objectives, from investigating basic social cognitive processes to measuring complex social interactive behaviors.

Comparative Analysis of VR Social Scenario Paradigms

The table below provides a systematic comparison of three primary VR social scenario types used in autism research, synthesizing performance data across multiple recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of VR Social Scenario Paradigms in Autism Research

| Scenario Type | Primary Research Focus | Experimental Measures | Reported Efficacy | Participant Profile | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Recognition Training | Social cue perception, emotional understanding | Classification accuracy, physiological arousal (SC, HR), reaction time | 70-85% recognition accuracy [25]; 14.14% faster reaction times post-training [22] | Mixed-functioning ASD; suitable for wider age range | Head-Mounted Display (HMD), physiological sensors (EDA, ECG, respiration) [25] |

| Adaptive Skill Acquisition | Daily living skills, executive function, real-world skill transfer | Task completion time, accuracy, parent-reported measures (ABC, BRIEF), transfer to real-world settings | 29.59% faster completion times; 43.22% reduction in ABC Relating subscale [22]; high ecological validity [26] | High-functioning ASD (IQ ≥80); ages 8-18 | HMD with handheld controllers, optional treadmill for locomotion [22] |

| Bidirectional Conversation Tasks | Social reciprocity, conversational turn-taking, gaze patterns | Performance accuracy, looking pattern (fixation duration), physiological engagement (pupil dilation, blink rate) | Improved performance and looking patterns in engagement-sensitive vs performance-only systems [27] | Adolescents with ASD; verbal participants capable of conversation | HMD with eye-tracking, virtual avatar interlocutors, physiological monitoring [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

Emotion Recognition Paradigms

Contemporary emotion recognition protocols utilize immersive VR environments to elicit and measure emotional responses through both behavioral and physiological channels. The standard protocol involves exposing participants to custom-built VR scenarios designed to evoke specific emotional states (sadness, relaxation, happiness, and fear) while collecting multi-modal data streams [25]. The experimental workflow typically follows these stages:

VR Environment Setup: Researchers create emotionally evocative virtual environments using psychology-based design principles. These environments incorporate visual, auditory, and contextual cues to induce target emotions.

Physiological Signal Acquisition: During VR exposure, multiple physiological signals are continuously recorded, including electrocardiogram (ECG), blood volume pulse (BVP), galvanic skin response (GSR), and respiration patterns [25].

Machine Learning Classification: Features extracted from physiological signals are processed using machine learning models (e.g., Logistic Regression with Square Method feature selection) in a subject-independent approach to classify emotional states.

Validation: Self-report measures and behavioral observations complement physiological data to validate emotional state classifications. Explainable AI techniques identify the most significant physiological features, with GSR peaks emerging as primary predictors for both valence and arousal dimensions [25].

This paradigm's strength lies in its objective, multi-modal assessment approach, which circumvents reliance on self-report measures that can be challenging for autistic individuals.

Adaptive Skill Acquisition Frameworks

Adaptive VR systems for skill training employ sophisticated algorithms that modify task parameters in real-time based on participant performance and engagement metrics. The IVR training system described in [22] exemplifies this approach:

Scenario Design: Researchers create four key training scenarios targeting essential daily skills: subway navigation, supermarket shopping, home activities, and amusement park social interactions. These environments are modeled after real-world settings to enhance ecological validity.

Task Progression Structure: Each scenario contains 36 discrete tasks that participants must complete twice. The system employs a progression-based adaptive strategy, gradually increasing difficulty as mastery is demonstrated [26].

Performance Metrics: The system continuously monitors task scores and completion times as primary outcome measures. This data drives the adaptive algorithm's decisions about when to advance difficulty levels.

Multi-dimensional Assessment: Primary outcomes are supplemented with parent-reported questionnaires (ABAS-II, ABC, BRIEF), neuropsychological tests (Go/No-Go, n-back, emotional face recognition), and qualitative interviews to capture cross-domain treatment effects [22].

This protocol emphasizes real-world skill transfer, with scenarios specifically designed to mirror actual daily challenges faced by autistic individuals.

Bidirectional Conversation Tasks

Bidirectional conversation paradigms represent the most complex social scenario type, focusing on the dynamic, interactive nature of real-world social communication. The physiologically-informed VR system described in [27] employs this approach:

System Architecture: The platform creates virtual environments with avatar interlocutors capable of bidirectional conversation. The system alters conversation components based on either performance alone or a composite of performance and physiological metrics.

Physiological Engagement Monitoring: The system continuously tracks eye gaze patterns, pupil diameter, and blink rate as indicators of engagement during social tasks. These metrics inform the adaptive response technology.

Adaptive Response Algorithm: A rule-governed strategy generator intelligently merges predicted engagement with performance metrics to individualize task modification strategies. For example, if both performance and engagement are low, the system adjusts conversational prompts to recapture attention [27].

Comparison Conditions: Studies typically compare performance-sensitive (PS) systems (responding to performance alone) with engagement-sensitive (ES) systems (responding to both performance and physiological engagement), demonstrating advantages for the ES approach [27].

This protocol's innovation lies in leveraging implicit physiological signals to adapt social demands in real-time, creating a more personalized learning environment.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Emotion Recognition Experimental Pipeline

Adaptive VR System Architecture

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for VR Social Scenario Implementation

| Component Category | Specific Items | Research Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Platforms | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) with eye-tracking capability | Provide immersive visual experience while capturing gaze metrics | HMDs integrated with eye-tracking sensors for conversation tasks [27] |

| Locomotion Interfaces | Treadmills with multidirectional wheels | Enable natural walking navigation in VR environments | Treadmill integration for subway and supermarket navigation scenarios [22] |

| Physiological Sensors | Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), Electrocardiogram (ECG), Blood Volume Pulse (BVP) sensors | Objective measurement of emotional and cognitive states | GSR sensors for emotion recognition accuracy [25] |

| Software Environments | Unity 3D game engine, OpenXR runtime | Creation and deployment of adaptive VR scenarios | Unity-based virtual environments for social skill training [5] |

| Adaptive Algorithms | Machine Learning classifiers (Logistic Regression), Rule-based decision systems | Automated adjustment of scenario difficulty based on performance | Logistic Regression with Square Method feature selection [25] |

| Assessment Tools | Parent-report questionnaires (ABAS-II, ABC, BRIEF), Neuropsychological tests (Go/No-Go, n-back) | Multi-dimensional outcome measurement across domains | ABAS-II for assessing adaptive behavior changes [22] |

The comparative analysis reveals that each VR social scenario paradigm offers distinct advantages for specific research objectives. Emotion recognition paradigms provide the highest measurement precision through multi-modal physiological assessment, making them ideal for investigating basic social cognitive processes. Adaptive skill acquisition frameworks demonstrate superior ecological validity and real-world transfer, particularly for daily living skills training. Bidirectional conversation tasks capture the most complex social interactive dynamics, essential for understanding social reciprocity challenges in ASD.

Selection of appropriate paradigms should consider research goals, participant characteristics, and technical resources. High-functioning autistic individuals typically show better outcomes across all paradigms, while low-functioning individuals may require tailored approaches [15]. Immersive VR systems generally produce stronger treatment effects but require more sophisticated technical infrastructure and careful management of potential adverse effects like dizziness and sensory overload [22] [15]. Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated adaptive algorithms, improving individualization through machine learning, and establishing standardized protocols for cross-study comparisons.

The validation of Virtual Reality (VR) social interaction paradigms for autism research is increasingly reliant on the integration of multi-modal data. This approach combines eye-tracking, physiological metrics, and behavioral performance data to create a comprehensive picture of user engagement, cognitive load, and social responsiveness. By moving beyond single-metric evaluation, researchers can develop more robust and ecologically valid experimental paradigms that accurately capture the complex behavioral and physiological signatures of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The growing emphasis on this multi-modal framework addresses critical challenges in ASD research, including substantial phenotypic heterogeneity and the need for objective biomarkers that can track intervention outcomes [28] [29]. This comparison guide examines current experimental approaches, their technical implementations, and the relative strengths of different multi-modal configurations for advancing VR-based autism research.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Multi-Modal Data Capture

VR Social Interaction with Integrated Physiological Monitoring

Objective: To quantify autistic adolescents' representational flexibility development during VR-based cognitive skills training through synchronized multi-modal data acquisition [30].

Procedure:

- Researchers conducted 178 training sessions with eight autistic adolescents using immersive VR systems.

- The protocol simultaneously collected behavioral cues, physiological responses, and direct interaction logs.

- Data streams were synchronized temporally to enable correlation analysis between physiological arousal, visual attention patterns, and task performance metrics.

- Machine learning techniques, particularly random forest algorithms with decision-level data fusion, were applied to the integrated dataset to predict development of representational flexibility [30].

Key Metrics: Eye-gaze patterns, heart rate variability, electrodermal activity, task completion accuracy, and response latency.

Simulated Interaction Task (SIT) for Behavioral Phenotyping

Objective: To detect autism through automated analysis of non-verbal behaviors using a standardized video dataset [29].

Procedure:

- Participants included 168 individuals with ASC (46% female) and 157 non-autistic controls (46% female), representing the largest and most balanced dataset available.

- The fully automated procedure began with head positioning for facial landmark calibration.

- Participants engaged in a conversation scenario with three emotion-eliciting phases: "Neutral" (meal preparation), "Joy" (favorite foods), and "Disgust" (disliked foods).

- Each phase consisted of two interactions: participant listening to an actress speak, followed by participant speaking while the actress displayed empathic listening.

- Multi-modal features were extracted across six interaction phases corresponding to emotion-specific segments and speaking roles [29].

Key Metrics: Facial action units, gaze behavior statistics, head movement kinematics, vocal prosody, and heart rate variability.

Motor Function Assessment with Neurophysiological Recording

Objective: To characterize the neural and behavioral mechanisms of motor function in autism during imitation tasks [31].

Procedure:

- Data were collected from 14 autistic adults and 20 neurotypical controls during two distinct imitation tasks: walking (confident vs. sad) and dancing (solo vs. duo).

- Participants wore a 16-channel wireless EEG cap while performing tasks in a 10-camera motion capture system with 37 body markers.

- Event triggers embedded in both data streams ensured temporal alignment between neurophysiological and behavioral data.

- Each recording session was structured into blocks with rest breaks, with trials presented in random order to control for sequence effects.

- The walking task required participants to imitate emotional walking patterns for 4-second intervals after viewing point-light animations [31].

Key Metrics: EEG spectral power, 3D joint kinematics, movement smoothness, task imitation accuracy.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Modal Approaches

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Multi-Modal Data Approaches in Autism Research

| Study Focus | Data Modalities Integrated | Participant Population | Key Findings | Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR Social Cognition Training [30] | Behavioral cues, physiological responses, interaction logs | 8 autistic adolescents | Decision-level data fusion enhanced prediction accuracy for representational flexibility development | Enhanced accuracy vs. single-source approaches (specific % not reported) |

| Automated Autism Detection [29] | Facial expressions, gaze behavior, head motion, voice prosody, HRV | 168 ASC & 157 non-ASC adults | Novel gaze descriptors improved performance; multimodal fusion outperformed unimodal approaches | 74% accuracy (multimodal fusion); 69% (gaze only); 64% (traditional gaze methods) |

| Motor Function in Autism [31] | EEG, 3D motion capture, neuropsychological scores | 14 autistic & 20 neurotypical adults | Dataset enables biomarker discovery for motor coordination difficulties in autism | Not yet reported (dataset designed for future classification studies) |

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Multi-Modal Data Acquisition Systems

| Modality | Recording Technology | Parameters Measured | Sampling Rate | Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye-Tracking [29] | Webcam-based tracking using OpenFace 2.2 | Gaze direction (x,y angles), screen fixation time, off-screen fixations | 30 Hz | OpenFace 2.2, custom MATLAB scripts |

| Physiological Metrics [29] | Webcam-derived photoplethysmography | Heart rate variability (HRV) | 30 Hz (interpolated) | Custom processing pipelines |

| EEG [31] | g.Nautlas wireless EEG system with 16 channels | Spectral power, event-related potentials | 250 Hz | MATLAB with Data Acquisition Toolbox |

| Motion Capture [31] | OptiTrack Flex 3 (10-camera system) | 3D joint angles, position, velocity | 120 Hz | OptiTrack Motive software |

| Facial Expression [29] | Webcam with OpenFace 2.2 | 18 Facial Action Units (presence & intensity) | 30 Hz | OpenFace 2.2 |

Data Integration and Workflow Architectures

Diagram 1: Multi-Modal Data Integration Workflow for VR Autism Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Multi-Modal VR Autism Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | HTC VIVE, Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) [32] [33] | Creates controlled, repeatable social scenarios | Balance ecological validity with experimental control; Consider motion sickness risks [32] |

| Eye-Tracking Solutions | OpenFace 2.2 [29], Webcam-based systems, Specialized eye-trackers | Quantifies gaze patterns, joint attention, social orienting | Webcam-based offers accessibility but lower precision; Dedicated systems provide higher accuracy [29] |

| Physiological Recording | g.Nautilus EEG [31], Wireless ECG/HRV systems, EDA sensors | Measures neural activity, autonomic arousal, stress responses | Wireless systems enable natural movement; Gel-based EEG electrodes provide better signal quality [31] |

| Motion Capture Systems | OptiTrack Flex 3 [31], Marker-based suits, Inertial measurement units | Quantifies motor coordination, gesture use, movement kinematics | Marker-based systems offer high precision but require controlled environments [31] |

| Behavioral Coding Software | OpenFace 2.2 [29], Custom MATLAB scripts, Psychtoolbox-3 [31] | Automates extraction of facial expressions, vocal features | Open-source solutions increase reproducibility; Custom scripts allow task-specific adaptations [29] [31] |

| Data Fusion & Analysis | Random Forest algorithms [30], MATLAB Data Acquisition Toolbox [31] | Integrates multi-modal data streams for predictive modeling | Decision-level fusion often outperforms single-modality approaches [30] |

The integration of multi-modal data represents a paradigm shift in validating VR social interaction paradigms for autism research. Current evidence demonstrates that combining eye-tracking, physiological metrics, and performance data significantly enhances the predictive validity of these experimental approaches beyond what any single modality can achieve. The emerging consensus indicates that decision-level data fusion strategies, particularly those employing machine learning algorithms like random forest, show superior performance in identifying meaningful patterns associated with ASD characteristics [30] [29].

Critical gaps remain in standardizing acquisition protocols across research sites, improving the ecological validity of laboratory-based measures, and developing normative models that account for the substantial heterogeneity within the autism spectrum [28]. Future validation studies should prioritize longitudinal designs that track developmental trajectories and examine how multi-modal profiles change in response to targeted interventions. As the field advances, the integration of these rich multi-dimensional data streams with genetic and neurobiological measures will further strengthen the validation framework for VR social interaction paradigms in autism research.

Virtual Reality (VR) has evolved from a fixed-experience medium to an adaptive intervention tool that dynamically responds to user states. This transformation is particularly impactful in autism research, where the heterogeneity of symptoms demands highly personalized approaches [26]. Physiologically informed VR systems represent a groundbreaking advancement by using real-time biosignal data to tailor interventions, moving beyond static performance-based adaptations to create truly responsive therapeutic environments. These systems address a critical challenge in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) interventions: the need for customized approaches that address individual symptom configurations [26]. By automatically detecting and responding to physiological indicators of engagement and arousal, these systems create dynamic feedback loops that optimize the therapeutic experience in real-time, potentially enhancing both learning outcomes and user engagement for individuals with ASD.

The foundation of these systems lies in their ability to monitor implicit signals—such as gaze patterns, heart rate variability, and electrodermal activity—alongside explicit performance metrics [26]. This multi-modal assessment enables a comprehensive understanding of user state that informs adaptation strategies. For ASD populations, who may experience challenges with emotional expression and communication, these physiological measures provide continuously available data not directly impacted by core communicative impairments [27]. This review systematically examines the experimental evidence, technical implementations, and clinical applications of physiologically adaptive VR systems, with particular emphasis on their validation for social interaction paradigms in autism research.

Comparative Analysis of Physiological Adaptation Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Physiological Adaptation Strategies in VR Systems

| Adaptation Type | Physiological Signals Monitored | Adaptive Response | Evidence Strength | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement-Sensitive | Eye gaze patterns, pupil dilation, blink rate [27] | Adjusts conversational prompts & task presentation [27] | Moderate (pilot studies with ASD adolescents) [27] | Social cognition training, conversation skills [27] |

| Performance-Based | Task performance metrics [26] | Level switching (progression/regression) [26] | Strong (multiple RCTs) [34] [35] | Skill acquisition, phobia treatment [36] |

| Arousal-Regulated | Heart rate, HRV, GSR, skin temperature [37] | Modifies cognitive load & environmental stimuli [37] | Emerging (pilot experiments) [37] | Stress management, emotional regulation [37] |

Table 2: Efficacy Outcomes Across VR Adaptation Paradigms

| Study Focus | Participant Group | Key Physiological Findings | Performance Outcomes | User Experience Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR vs. Mobile Gaming [34] | 22 healthy university students | Significantly higher HRmean, HRmax, and HRtotal in VR (p < 0.05) [34] | Increased time spent at Above Very Light intensity in VR [34] | Not assessed in study |

| VR vs. Traditional HIIT [35] | 10 physically active adults | No significant HR differences between groups [35] | Comparable exercise intensity achieved [35] | Lower RPE (p < 0.001) and higher flow state in VR [35] |

| 2D vs. 3D Emotional Arousal [38] | 40 university volunteers | Higher beta EEG power (21-30 Hz) in 3D VR (p < 0.05) [38] | Not primary focus | Stronger emotional arousal in 3D environments [38] |

| Engagement-Sensitive VR [27] | 8 adolescents with ASD | Improved looking patterns and physiological engagement indices [27] | Enhanced task performance in ES vs PS system [27] | High acceptability and feasibility [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Engagement-Sensitive VR for Social Cognition Training

Lahiri and colleagues developed a physiologically responsive VR system for conversation skills training in adolescents with ASD that exemplifies the sophisticated methodology underlying adaptive systems [27]. The experimental protocol involved a within-subjects comparison between two conditions: a Performance-sensitive System (PS) that adapted based solely on task performance, and an Engagement-sensitive System (ES) that responded to a composite of performance and physiological metrics of predicted engagement including gaze patterns, pupil dilation, and blink rate [27]. The system employed a rule-governed strategy generator to intelligently merge predicted engagement with performance during VR-based social tasks.

The experimental workflow followed a structured sequence: (1) baseline physiological calibration, (2) VR social interaction scenario presentation, (3) continuous monitoring of eye-tracking metrics and performance, (4) real-time computation of engagement index, and (5) adaptive response generation. When the system detected unsatisfactory performance coupled with low predicted engagement, it automatically adjusted conversational prompts and task presentation to recapture attention [27]. This methodology demonstrated that adolescents with ASD showed improved performance and looking patterns within the physiologically sensitive system compared to the performance-only system, suggesting that physiologically informed technologies have potential as effective intervention tools [27].

Arousal-Regulated VR for Stress and Performance Optimization

Another innovative approach comes from research examining how VR systems can modulate arousal to optimize performance [37]. This study implemented a modular narrative system designed to manipulate user arousal levels within an optimal range—avoiding both excessive stress (high arousal) and boredom (low arousal). The experimental protocol instantiated an increasing number of simultaneous tests and environmental changes at different points during a VR experience where participants were embodied in a gender-specific out-group avatar subjected to verbal Islamophobic attacks [37].

The methodology included: (1) assignment to one of three stress conditions (low: 1 task, medium: 2 tasks, high: 3 tasks to complete simultaneously), (2) measurement of autonomic signals (heart rate, heart rate variability, galvanic skin response, skin temperature) throughout the experience, (3) assessment of performance in multiple choice listening comprehension tasks, and (4) post-treatment recall evaluation [37]. Contrary to the hypothesized inverted U-model of arousal and performance, results revealed a statistically significant difference in narrative task performance between stress levels (F(2,45)=5.06, p=0.02), with the low stress group achieving the highest mean VR score (M=73.12), followed by the high (M=63.25) and medium stress groups (M=51.81) [37]. This methodology demonstrates how VR systems can systematically manipulate arousal states while measuring corresponding performance impacts.

Technical Implementation: Adaptive Engines and Signaling Pathways

System Architecture and Adaptive Logic

Table 3: Adaptive Engine Architectures in VR Systems

| Engine Type | Decision Mechanism | Input Signals | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-Automatized [26] | Professional analyzes data and makes adaptation decisions [26] | Behavioral observation, performance metrics [26] | Clinical expertise in decision loop | Requires technical expertise, potential human bias [26] |

| System-Automatized (Non-ML) [26] | Rule-based algorithms pre-programmed by developers [26] | Explicit behavioral indicators, task performance [26] | Transparent, predictable, cost-effective | Limited flexibility, may not capture complexity [26] |

| System-Automatized (ML-Based) [26] | Machine learning models trained on user response patterns [26] | Implicit biosignals (eye gaze, physiology), performance [26] | Handles complex patterns, personalized adaptation | "Black box" decisions, requires substantial training data [26] |

The technical implementation of physiologically adaptive VR systems relies on sophisticated signaling pathways that transform raw physiological data into meaningful system adaptations. As illustrated in Figure 2 below, this process involves multiple stages of signal acquisition, processing, and response generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Physiologically Adaptive VR Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | Oculus Quest 2 [34] [35], HTC Vive, PlayStation VR [39] | Creates immersive virtual environments | Exercise studies [35], social scenario presentation [27] |

| Eye Tracking Systems | Tobii Eye Trackers, HMD-integrated gaze tracking [27] | Monitors gaze patterns, pupil dilation, blink rate [27] | Engagement detection in ASD interventions [27] |

| Physiological Monitors | Polar HR monitors [35], GSR sensors, EEG systems [38] | Measures HR, HRV, electrodermal activity, brain activity [37] [38] | Arousal regulation studies [37], emotional response measurement [38] |

| Adaptive Software Platforms | DiSCoVR [40], PsyTechVR [36], oVRcome [36] | Provides framework for implementing adaptation logic | Social cognition training [40], phobia treatment [36] |

| Data Analysis Tools | MATLAB, Python (with scikit-learn, TensorFlow), SPSS | Processes biosignals, implements ML algorithms, statistical analysis | Signal processing, engagement classification [26] |

Discussion and Future Research Directions

The validation of physiologically informed VR systems for autism research represents a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize, design, and implement interventions for social interaction challenges. Current evidence suggests that systems adapting based on composite signals—both implicit physiological measures and explicit performance metrics—outperform those relying on performance alone [27] [26]. However, several important considerations emerge from the experimental data.

The heterogeneity of ASD symptoms necessitates highly individualized adaptation approaches. Research indicates that approximately 76% of participants across adaptive VR studies had ASD, with systems employing various adaptation strategies including level switching (70% of studies), adaptive feedback (90%), and both ML (30%) and non-ML (80%) adaptive engines [26]. These systems used signals ranging from explicit behavioral indicators (60%) to implicit biosignals like eye gaze, motor movements, and physiological responses (70%) [26].

Future research should address several critical gaps. First, larger-scale controlled trials are needed to establish efficacy, as many current studies are pilot investigations with limited sample sizes [27] [35] [40]. Second, the optimal combination of physiological signals for different ASD subgroups remains undetermined. Third, longitudinal studies examining transfer of skills to real-world social interactions are essential. Finally, standardized protocols for system adaptation and outcome measurement would enhance comparability across studies.

The potential impact of these technologies extends beyond clinical applications to fundamental autism research. By providing precise control over social stimuli while monitoring physiological responses, these systems offer unprecedented opportunities to investigate social information processing mechanisms in ASD. This dual utility as both intervention tool and research platform positions physiologically adaptive VR as a transformative technology in the autism research landscape.

As the field advances, integration with other emerging technologies like artificial intelligence for predictive adaptation and wearable sensors for continuous monitoring outside lab settings will likely enhance both the effectiveness and accessibility of these interventions. The convergence of technological innovation and neuroscience-informed approaches holds significant promise for advancing both our understanding and support of social functioning in individuals with ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) encompasses a wide range of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by challenges in social communication and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. The terms "high-functioning autism" (HFA) and "low-functioning autism" (LFA) represent points on this spectrum, though they are not formal diagnostic categories in current clinical guidelines. These distinctions remain clinically useful for tailoring interventions to individual needs and support requirements. While high-functioning autism typically describes individuals with average or above-average intelligence and language skills who can function independently, low-functioning autism refers to those with significant intellectual and developmental disabilities who often require substantial support for daily living activities [41] [42]. The differentiation primarily lies in the level of intellectual and developmental disability, which directly impacts intervention strategies and expected outcomes [41].