Virtual Reality vs. Real-World Navigation: A Neuroscientific Comparison for Clinical and Research Applications

This article synthesizes current research on the neural correlates of spatial navigation in virtual reality (VR) versus real-world environments, tailored for researchers, neuroscientists, and drug development professionals.

Virtual Reality vs. Real-World Navigation: A Neuroscientific Comparison for Clinical and Research Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the neural correlates of spatial navigation in virtual reality (VR) versus real-world environments, tailored for researchers, neuroscientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational neuroscience, highlighting shared and distinct brain network engagement. The review covers the application of VR in clinical diagnostics, cognitive training, and neuroimaging, while addressing key methodological challenges such as cybersickness and sensory conflict. It critically evaluates the validity of VR for modeling real-world navigation and the transfer of spatial knowledge. The conclusion synthesizes these findings, discussing implications for developing novel biomarkers and therapeutic interventions for neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders.

The Brain's Navigation System: Core Circuits and the Impact of Virtual Environments

The study of spatial navigation has been revolutionized by the discovery of specialized neural populations—place cells, grid cells, and head direction cells—that collectively form the brain's positioning system. While traditionally studied in freely moving animals, recent advances in virtual reality (VR) technologies have enabled unprecedented experimental control, allowing researchers to dissect the specific contributions of various sensory cues to spatial representations. This guide compares the firing properties and functional characteristics of these spatial cells across real-world and virtual environments, synthesizing key experimental findings to illuminate how the brain constructs spatial maps under different navigation conditions. The integration of VR in neuroscience has revealed both remarkable preservation and significant alteration of spatial coding principles, with important implications for interpreting neural data collected under various experimental constraints.

Comparative Analysis of Spatial Cell Firing Properties

Quantitative Differences Between Real and Virtual Navigation

Table 1: Comparison of Place Cell Properties in Real vs. Virtual Environments

| Property | Real World (R) | Virtual Reality (VR) | Change Factor | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place Field Size | Baseline | 1.44x larger | 1.44× increase | Broader spatial tuning [1] |

| Spatial Information Content | Higher | Lower | Significant decrease | Reduced location specificity [1] |

| Directional Modulation | Less directional | More strongly directional | Significant increase | Increased direction-specific firing [1] |

| Firing Rates | Similar baseline | Similar to real world | No significant change | Preserved firing rate patterns [1] |

| Theta Phase Precession | Present | Similar to real | No significant change | Intact temporal coding [1] |

Table 2: Comparison of Grid Cell Properties in Real vs. Virtual Environments

| Property | Real World (R) | Virtual Reality (VR) | Change Factor | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Scale | Baseline | 1.42x larger | 1.42× increase | Expanded spatial periodicity [1] |

| Gridness Score | Similar to baseline | Similar to real | No significant change | Preserved hexagonal symmetry [1] |

| Spatial Information Content | Higher | Lower | Significant decrease | Reduced spatial specificity [1] |

| Directional Modulation | Slightly directional | Less directional | Slight decrease | Effect disappears in controlled models [1] |

| Firing Rates | Similar baseline | Similar to real | No significant change | Preserved firing rate patterns [1] |

Table 3: Comparison of Head Direction Cell Properties

| Property | Real World (R) | Virtual Reality (VR) | Change Factor | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Tuning | Stable directional firing | Similar to real | No significant change | Preserved directional tuning [1] |

| Firing Patterns | Characteristic directional tuning | Unchanged spatial tuning | Minimal differences | Most stable across environments [1] |

Behavioral and Cognitive Correlates

Spatial memory performance shows consistent advantages for physical navigation compared to virtual environments. In human studies, participants demonstrated significantly better memory performance when physically walking during a spatial task compared to a stationary VR version, despite identical visual cues [2]. Participants also reported that the walking condition was significantly easier, more immersive, and more enjoyable than the stationary condition, suggesting that the incorporation of actual movement enhances both performance and engagement [2]. These behavioral advantages correlate with neural signatures, including increased amplitude of hippocampal theta oscillations during physical movement, potentially explaining the memory enhancement [2].

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Rodent Virtual Reality Navigation Paradigms

The foundational rodent VR studies employed sophisticated systems designed to balance experimental control with naturalistic navigation behaviors. The typical apparatus involves:

- Head-fixed navigation on an air-suspended Styrofoam ball, allowing rotation but restricting translational movement [1]

- Projection systems that display 360° virtual environments from a viewpoint that moves with the rotation of the ball [1]

- Visual cue control that eliminates uncontrolled real-world cues while maintaining precise experimental manipulation capabilities [1]

In the fading beacon task used to assess spatial learning, mice were trained to navigate to an unmarked reward location in an open virtual arena, similar to a continuous Morris Water Maze task [1]. Performance steadily improved across 2-3 weeks of training, demonstrating that mice could perceive and remember locations defined solely by virtual space, even after visual beacons were completely removed [1].

Gain Manipulation Experiments

To dissociate the contributions of visual environmental inputs from physical self-motion signals, researchers have employed gain manipulation protocols [3]. This approach involves:

- Altering the relationship between physical movement on the ball and visual motion in the virtual environment

- Implementing differential gain changes (e.g., G=2 for increased gain, G=2/3 for decreased gain) along one spatial dimension while maintaining normal gain along the other dimension as an internal control

- Quantifying the relative influence of physical motion versus visual input using a Motor Influence (MI) score, where MI = (F-1)/(G-1), with F representing the stretch factor that provides the best fit to baseline firing patterns

These experiments revealed that place cell firing patterns show predominantly visual influence (median MI = 0.21-0.37), while grid cell patterns reflect a more balanced influence with weighting toward physical motion (median MI = 0.58-0.89) [3].

Figure 1: Differential Influences on Spatial Cell Types. Place cell firing predominantly follows visual cues, while grid cell activity shows stronger influence from physical self-motion, leading to potentially dissociable spatial representations [3].

Reward-Relative Remapping Protocols

Recent research has investigated how hippocampal representations encode events relative to reward locations using virtual reality reward learning tasks [4]. The experimental approach includes:

- Training head-fixed mice to navigate virtual linear tracks with hidden reward zones

- Implementing reward location switches within constant visual environments to dissociate spatial from reward-related coding

- Using two-photon calcium imaging of CA1 neurons throughout learning

- Analyzing remapping patterns by comparing peak spatial firing before versus after reward switches

This research identified distinct cell populations: Track-Relative (TR) cells that maintain stable firing at the same track location regardless of reward (21.4% of place cells), and Reward-Relative (RR) cells that update their firing fields to maintain the same position relative to reward locations [4]. The proportion of RR cells increases with task experience, demonstrating how hippocampal ensembles flexibly encode multiple aspects of experience while amplifying behaviorally relevant information.

Extended Neural Correlates of Spatial Navigation

Distributed Spatial Representations

While the hippocampal formation remains the central hub for spatial processing, recent evidence reveals that spatial coding extends throughout the brain:

- Somatosensory cortex contains the full complement of spatially selective cells, including place cells, grid cells, head direction cells, and border cells [5]. Approximately 9.63% of S1 neurons show place cell-like properties when applying stringent classification criteria [5].

- Grid-like representations have been observed in human fMRI studies across multiple brain regions outside the hippocampal formation, including posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and retrosplenial cortex [5].

Speed Modulation of Grid Cell Coding

Running speed significantly influences the quality of spatial representations in grid cells:

- Spatial coding accuracy in grid cell populations improves with increasing running speed, as measured by locally linear classification accuracy [6]

- Increased running speed both dilates the grid cells' toroidal-like manifold and increases neural noise, but the manifold dilation outpaces noise increase [6]

- The net effect is higher Fisher information at faster speeds, suggesting improved spatial decoding accuracy despite increased noise [6]

Figure 2: Speed Modulation of Grid Cell Coding. Increased running speed has competing effects on grid cell spatial representations, with beneficial manifold dilation outweighing detrimental noise increases, resulting in net improved spatial coding accuracy [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

| Reagent/Technology | Function/Application | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Reality Systems | Provides controlled visual environments while restricting movement | Compatible with multiphoton imaging; allows cue manipulation [1] |

| Tetrode/Multitetrode Arrays | Enables extracellular recording of multiple single neurons | Allows simultaneous monitoring of place, grid, and head direction cells [5] |

| Two-Photon Calcium Imaging | Monitors neural population activity with cellular resolution | Suitable for head-fixed VR experiments; tracks large ensembles [4] |

| Air-Suspended Styrofoam Ball | Provides locomotion interface for head-fixed navigation | Allows rotation but constrains translation; compatible with VR [1] |

| Gain Manipulation Software | Decouples visual motion from physical movement | Quantifies relative influence of different cue types [3] |

| Position Decoding Algorithms | Reconstructs spatial position from neural activity | Tests functional fidelity of spatial representations [6] [7] |

The comparative analysis of spatial navigation across real and virtual environments reveals both remarkable resilience and intriguing vulnerability in the brain's positioning system. While the core representational patterns of place cells, grid cells, and head direction cells persist in VR, systematic alterations in spatial tuning, field size, and directional properties highlight the differential dependence of these cell types on various sensory inputs. Place cells appear more tightly coupled to visual environmental cues, while grid cells maintain stronger connections to physical self-motion signals, creating a potential fault line in spatial coherence under cue dissociation [3]. These findings not only illuminate the fundamental organization of spatial circuits but also provide crucial constraints for interpreting neural data collected under various experimental conditions, from tightly controlled VR paradigms to naturalistic navigation studies.

Spatial navigation is the ability to determine and maintain a route from a starting point to a goal, a complex cognitive process supported by multiple neural systems [8]. Research into these systems has increasingly focused on two primary frames of reference: allocentric (map-based) and egocentric (body-centered) navigation [9] [8]. The allocentric strategy involves encoding spatial relationships between landmarks in the environment independent of one's own position, creating a cognitive map of the environment [10]. In contrast, the egocentric strategy relies on self-to-object relationships and path integration, updating one's position relative to the starting point based on self-motion cues such as vestibular and proprioceptive information [10]. Understanding these distinct but interacting systems is crucial for research comparing neural correlates in virtual reality (VR) versus real-world navigation, particularly as VR and serious game-based instruments become valuable tools for assessing spatial memory in clinical and research populations [8].

Comparative Analysis: Core Definitions and Characteristics

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Allocentric and Egocentric Navigation

| Feature | Allocentric (Map-Based) Navigation | Egocentric (Body-Centered) Navigation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Encodes object positions using a framework external to the navigator [10] | Encodes object positions relative to the self, using body-centered coordinates [10] [11] |

| Primary Strategy | Map-based navigation or piloting [10] | Path integration combined with landmark/scene processing [10] |

| Reference Frame | World-centered, viewpoint-independent [8] | Body-centered, viewpoint-dependent [8] |

| Key Inputs | Allothetic (external) cues: landmarks and environmental features [10] | Idiothetic (self-motion) cues: vestibular, proprioceptive, optic/acoustic flow [10] |

| Spatial Knowledge | Survey knowledge: holistic, "bird's-eye-view" configuration [10] | Egocentric survey knowledge: orientation-specific, first-person perspective [10] |

| Cognitive Process | Integration of landmark configurations in spatial working memory [10] | Continuous or discrete updating of position relative to travel origin [10] |

Neural Substrates: Dissociable but Interactive Brain Networks

The two navigation strategies are supported by distinct, though interacting, neural networks. Allocentric navigation is primarily linked to structures in the medial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal cortex, which support the cognitive map [8]. Egocentric navigation, however, relies more heavily on the parietal lobe, particularly the posterior parietal cortex, precuneus, and retrosplenial cortex (RSC) [8]. The RSC is considered a critical interface for transformations between egocentric and allocentric coordinate systems [11]. During navigation, information from these systems is integrated with contributions from frontal lobes, caudate nucleus, and thalamus [8].

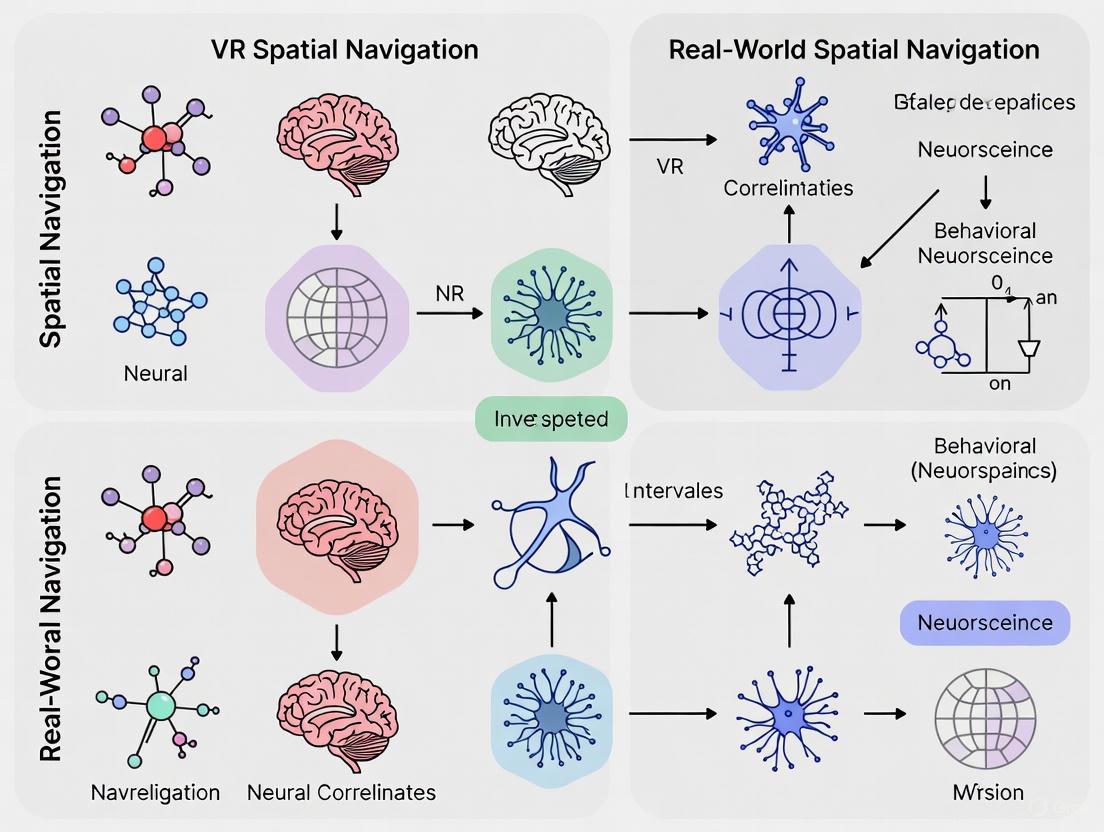

Figure 1: Neural Networks of Allocentric and Egocentric Navigation. The diagram illustrates the dissociable but interactive brain systems supporting the two primary navigation strategies, culminating in integrated spatial behavior through higher-order structures.

Experimental Evidence and Key Methodologies

Behavioral Dissociation Paradigms

Experimental studies have successfully dissociated these navigation systems through targeted interventions. Zhong and Kozhevnikov (2023) demonstrated a double dissociation: participants forming egocentric survey-based representations were significantly impaired by disorientation, indicating reliance on path integration. Conversely, those forming allocentric survey-based representations were impaired by a secondary spatial working memory task, indicating reliance on map-based navigation [10]. This confirms that egocentric representations are orientation-specific, while allocentric representations are orientation-free and depend on spatial working memory.

Virtual Reality Navigation Tasks

VR has become a primary tool for investigating spatial memory, with the hidden goal task (a human version of the Morris water maze) being a prominent paradigm [8]. This task can be configured to assess either allocentric or egocentric strategies. In one systematic review, both real-world and virtual versions of navigation tasks showed good overlap for assessing spatial memory, supporting the ecological validity of VR [9].

Table 2: Key Experimental Paradigms and Their Findings

| Experimental Paradigm | Target Strategy | Key Manipulation/Task | Primary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disorientation & Spatial WM Tasks [10] | Both | Disorientation; Secondary spatial working memory task | Double dissociation: Egocentric impaired by disorientation; Allocentric impaired by spatial WM load [10] |

| Virtual Reality Hidden Goal Task [8] | Both | Navigate to a hidden goal using environmental cues | Correlates with integrity of medial temporal and parietal lobes; used to detect MCI/AD [8] |

| Virtual Museum Object-Location Task [12] | Both | Encode and recall locations of paintings in a VR museum | Better egocentric recall accuracy for body-related stimuli (hands), regardless of perspective [12] |

| Pursuit/Predation Behavior Task [11] | Transformation | Rats chase a moving target | Retrosplenial cortex (RSC) shows predictive coding and complex firing patterns during coordinate transformation [11] |

Figure 2: Generic Workflow for a VR Object-Location Memory Task. This paradigm, adapted from studies like the virtual museum experiment [12], can be configured to test either allocentric or egocentric spatial memory separately or concurrently.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Navigation Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function/Application | Relevance to Navigation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Unity Game Engine with Landmarks Asset Package [13] | Platform for building and deploying 3D navigation experiments for desktop and VR | Provides a flexible, no-code/low-code framework for creating controlled, replicable navigation environments; supports various VR HMDs [13] |

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) e.g., HTC Vive, Oculus Rift [13] | Provide immersive VR experiences with access to body-based cues | Enables more naturalistic study of learning and memory in 3D spaces compared to desktop setups [13] |

| Hidden Goal Task (Virtual Morris Water Maze) [8] | Assess allocentric and egocentric navigation strategies | Gold-standard paradigm for testing spatial mapping and memory; correlates with medial temporal lobe function [8] |

| Non-Immersive VR Setups [9] | Desktop-based virtual navigation tasks | Provides a controlled, accessible alternative to HMDs; widely used in studies involving clinical populations like MCI [9] |

| Retrosplenial Cortex (RSC) Animal Models [11] | Investigate neural mechanisms of spatial transformation | Key for causal studies on the role of RSC in transforming between egocentric and allocentric coordinates during behaviors like pursuit [11] |

Implications for VR vs. Real-World Neural Correlates Research

The dissociation between allocentric and egocentric systems provides a critical framework for evaluating the ecological validity of VR in spatial navigation research. Studies indicate that both real-world and VR versions of navigation tasks show good overlap in assessing spatial memory, particularly for allocentric abilities [9]. However, an important consideration is that VR may place different demands on egocentric processing due to potential reductions in or altered quality of idiothetic (self-motion) cues compared to real-world navigation [8]. This is particularly relevant for patient populations. For instance, in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease (AD), deficits in allocentric navigation often manifest earlier due to initial pathological changes in the medial temporal lobe, while egocentric deficits become more pronounced as the disease progresses to involve parietal regions [9] [8]. Consequently, VR tasks sensitive to allocentric impairments, such as the hidden goal task, are being developed as potential digital biomarkers for preclinical AD screening [8].

Virtual Reality (VR) provides unprecedented control for studying spatial navigation, yet it fundamentally lacks the rich, integrated idiothetic cues—vestibular, proprioceptive, and motor efference signals—that are crucial for real-world navigation and the neural processes that support it. In real-world navigation, the brain seamlessly integrates allothetic cues (external, sensory information like landmarks) with idiothetic cues (internal, self-motion information derived from body movement) to create stable spatial representations and support accurate navigation [14] [15]. VR systems, particularly those that are stationary or use artificial locomotion methods, create a sensory conflict by providing compelling visual allothetic cues while stripping away or distorting the idiothetic signals that the brain expects from actual movement through space. This review synthesizes current experimental evidence demonstrating how this idiothetic deficit in VR affects both behavioral navigation performance and the underlying neural correlates, with critical implications for research and clinical applications.

Behavioral and Performance Discrepancies: VR vs. Real-World Navigation

Empirical Evidence of Navigation Performance Gaps

Multiple controlled studies directly comparing navigation in virtual and real environments reveal significant performance decrements in VR, attributable to the lack of integrated idiothetic cues.

Table 1: Comparative Navigation Performance in Real-World (RW) vs. Virtual Reality (VR) Environments

| Performance Metric | Real-World Performance | VR Performance | Significance & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path Efficiency | Shorter distances covered [16] | Longer distances covered [16] | RW navigation is more efficient |

| Wayfinding Accuracy | Fewer errors and wrong turns [16] | More mistakes made [16] | RW wayfinding is more accurate |

| Task Completion Time | Faster task completion [16] | Longer task completion times [16] | RW navigation is faster |

| Spatial Memory Accuracy | Significantly better object-location recall [2] | Reduced spatial memory performance [2] [16] | Physical movement enhances encoding |

| Participant Perception | Reported as easier, more immersive, and fun [2] | Higher perceived cognitive workload and task difficulty [16] | Physical navigation is subjectively preferred |

A study utilizing an Augmented Reality (AR) paradigm, which allows for physical movement, provided direct evidence for the importance of idiothetic cues. Participants showed significantly better spatial memory performance when walking in the real world (AR condition) compared to performing a matched task in stationary VR. Participants also reported that the walking condition was "significantly easier, more immersive, and more fun" [2]. This suggests that the lack of integrated physical movement and its associated idiothetic cues in VR negatively impacts both objective performance and subjective experience.

Furthermore, a comparative study in a multi-level educational facility found that VR navigation involved longer distances covered, more errors, and longer task completion times compared to navigating an identical real-world environment [16]. These findings indicate that the idiothetic cue deficit in VR leads to less efficient and accurate wayfinding.

The Impact of VR Locomotion Methods on Spatial Orientation

The method by which users navigate in VR—a proxy for the degree of idiothetic cue simulation—differentially affects spatial orientation and user comfort.

Table 2: Impact of VR Locomotion Methods on Spatial Orientation and Cybersickness

| Locomotion Method | Description | Navigation Performance | Cybersickness | Usability (SUS Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand-Tracking (HTR) with Teleportation | Instantaneous displacement; minimal self-motion | Longest completion times; impaired spatial orientation [17] | Lowest (1.8 ± 0.9) [17] | 65.83 ± 22.22 [17] |

| Controller (CTR) Joystick | Continuous visual flow without vestibular match | Moderate completion times [17] | Intermediate (2.3 ± 1.1) [17] | 74.67 ± 18.52 [17] |

| Cybershoes (CBS) | Foot-based movement with proprioceptive feedback | Efficient navigation, comparable to CTR [17] | Highest (2.9 ± 1.2) [17] | 67.83 ± 24.07 [17] |

Research demonstrates that teleportation, while minimizing cybersickness, severely impairs spatial orientation and cognitive map formation because it provides no continuous idiothetic information for path integration [17]. In contrast, continuous locomotion methods like joystick control (CTR) or foot-based devices (CBS) provide more idiothetic information, supporting better navigation efficiency, particularly in complex environments [17]. However, these methods often induce greater cybersickness due to the sensory conflict between visual motion and the lack of corresponding vestibular acceleration signals [17]. This conflict is a direct consequence of the idiothetic cue deficit.

Neural Correlates: How Idiothetic Cues Shape Hippocampal Function

The behavioral deficits observed in VR have a clear neurophysiological basis. The hippocampus and associated medial temporal lobe structures, which are fundamental for spatial memory and navigation, rely on the integration of both allothetic and idiothetic cues.

Figure 1: Neural Integration of Cues in Hippocampal Navigation. Idiothetic and allothetic cues drive multiplexed coding within the hippocampal theta rhythm, which is disrupted in VR.

Groundbreaking research reveals that hippocampal theta oscillations (~6-10 Hz) act as a temporal framework that multiplexes the processing of different cue types into distinct phases [15]. Idiothetic cues (self-motion) predominantly reinforce late theta phase activity, driving phase precession where place cells fire to prospectively represent future locations [15]. In contrast, allothetic cues (landmarks) primarily shape early theta phase activity, modulating retrospective representations and novel memory encoding [15]. This multiplexing allows the brain to simultaneously manage prediction (via idiothetic cues) and learning (via allothetic cues).

In VR, where idiothetic cues are absent or unreliable, this delicate neural balance is disrupted. Studies in cue-poor VR environments show that the hippocampus attempts to compensate by relying heavily on a global distance coding scheme based on self-motion [18]. However, this coding is altered and less rigid than normal, and the critical theta rhythm—which is pronounced during real physical movement—is significantly degraded in stationary VR tasks [2] [15]. This provides a direct neural explanation for the less robust and accurate spatial memories formed in virtual environments.

Experimental Paradigms and Research Tools

Key Experimental Protocols

To investigate the role of idiothetic cues, researchers have developed sophisticated protocols that manipulate the relationship between visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive feedback.

1. Motion Gain Adaptation Protocol: This paradigm, used to study perceptual and postural adaptation, involves an initial adaptation phase where participants perform a VR game (e.g., hitting targets by moving laterally) while their physical motion is scaled by a gain factor [19]. In a reduced gain condition (e.g., 0.667), a large physical step produces a small virtual step, while an increased gain (e.g., 2.0) makes a small physical step result in a large virtual displacement [19]. The subsequent test phase measures the aftereffects on the Point of Subjective Stationarity (PSS) and postural sway, revealing how the sensorimotor system recalibrates to mismatched cues [19].

2. Integrated GVS and VR Balance Protocol: This protocol directly tests vestibular-visual integration by combining Galvanic Vestibular Stimulation (GVS) with a VR optokinetic (OPK) stimulus [20]. Participants stand on a force plate while black and white vertical bars move left to right in the VR headset. Researchers apply GVS current in the same direction as the visual motion (Positive GVS), opposite (Negative GVS), or with no GVS (Null GVS) [20]. The force plate records center of pressure (COP) sway, measuring how conflicting vestibular and visual inputs disrupt postural stability, a low-level indicator of idiothetic cue conflict [20].

Figure 2: GVS-VR Postural Sway Protocol. This workflow tests integration of visual and artificially provided vestibular signals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Idiothetic Cues Research

| Item | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Presents controlled visual stimuli and tracks head orientation. | Oculus Rift S [19], HTC Vive [20], SteamVR [20] |

| Galvanic Vestibular Stimulator (GVS) | Artificially provides vestibular sensation via mastoid electrodes, probing vestibular contribution. | Bipolar electrodes delivering 0-2 mA current [20] |

| Force Plate / Posturography System | Quantifies postural sway and balance (Center of Pressure) in response to sensory conflicts. | Bertec Portable Essential dual-balance platform [20] |

| Motion Tracking System | Precisely records physical movement (head/body) for gain manipulation and analysis. | Built-in HMD cameras & IMU for 6 DoF tracking [19] |

| Virtual Environment Software | Creates reproducible, cue-controlled navigation tasks (e.g., mazes, spatial memory tests). | PsychoPy [19], Custom VR games (Sea Hero Quest [21], MoonRider [19]) |

| Olfactory Delivery Device | Provides synchronized scent cues to study multisensory integration beyond vision/hearing. | Device attachable to HMD delivering instant scents [22] |

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that the lack of integrated vestibular, proprioceptive, and motor efference signals in VR creates a fundamental disconnect between human neural architecture and the simulated environment. This idiothetic deficit is not merely a technical limitation but a core issue that manifests behaviorally as reduced navigation efficiency, impaired spatial memory, and increased disorientation, and neurally as disrupted hippocampal theta rhythms and altered place cell dynamics. While VR remains an invaluable tool for its experimental control and flexibility, researchers and clinicians must explicitly account for its ecological validity limitations, particularly when generalizing findings to real-world navigation or using VR for diagnostic purposes. Future research must focus on developing more effective methods to simulate or stimulate idiothetic cues, such as advanced GVS, omnidirectional treadmills, and multisensory integration, to bridge the gap between the virtual and the real.

Spatial navigation is a complex cognitive process that engages a distributed brain network. With the increasing use of virtual reality (VR) in cognitive neuroscience and clinical diagnostics, a critical question has emerged: to what extent do the neural correlates of navigation in virtual environments mirror those activated in real-world navigation? This review synthesizes functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) evidence to compare brain activation patterns during real-world and virtual navigation. We find substantial but not complete neural overlap, characterized by a core network including medial temporal, parietal, and frontal regions. Key divergences appear in the depth of hippocampal engagement and the integration of sensory and self-motion signals, influenced by factors such as physical movement and immersion level. Understanding these shared and unique neural signatures is crucial for refining VR's application in fundamental research and early detection of neurodegenerative diseases.

Spatial navigation is a fundamental cognitive ability that enables organisms to traverse and understand their environment. In humans, this process relies on a sophisticated brain network, notably including the hippocampal formation, which supports the formation and recall of cognitive maps [23]. The advent of virtual reality (VR) technology has provided neuroscientists with a powerful tool to study navigation in controlled, replicable laboratory settings. However, the ecological validity of VR hinges on a critical question: does the brain navigate a virtual space as it does a real one?

Neuroimaging, particularly fMRI, has been instrumental in mapping the neural underpinnings of navigation. A meta-analysis of 27 years of functional neuroimaging studies on urban navigation identified a consistent large-scale network in healthy humans. This network encompasses the bilateral median cingulate cortex, supplementary motor areas, parahippocampal gyri, hippocampi, retrosplenial cortex, precuneus, prefrontal regions, cerebellar lobule VI, and striatum [23]. This core network is engaged across various navigation tasks, but its specific activation pattern is modulated by the nature of the task, such as the choice between route-based and survey-based strategies [23].

This article provides a systematic comparison of the fMRI-derived neural activation patterns during real-world and virtual navigation. We synthesize evidence from meta-analyses, controlled comparative studies, and clinical applications to delineate the boundaries of neural overlap and divergence. Furthermore, we detail the experimental protocols that have generated key findings and visualize the core neural circuits and experimental workflows. This synthesis aims to guide researchers in interpreting neuroimaging data across navigation paradigms and in developing more ecologically valid virtual environments.

Neural Overlap: The Core Navigation Network

Despite differences in medium, navigation in both real and virtual worlds consistently recruits a common set of brain regions fundamental to spatial processing and memory. This core network facilitates a range of functions from path integration to cognitive map formation.

Key Overlapping Brain Regions

The shared neural substrate for navigation is extensive. A large-scale meta-analysis of urban navigation studies, which included data from both real and virtual environments, identified a consistent frontal-occipito-parieto-temporal network [23]. The table below summarizes the key brain regions and their proposed functions in this core network.

Table 1: Core Brain Regions Activated in Both Real and Virtual Navigation

| Brain Region | Proposed Function in Navigation |

|---|---|

| Hippocampus | Formation of cognitive maps and episodic spatial memory [23]. |

| Parahippocampal Gyrus / Parahippocampal Place Area (PPA) | Processing of environmental landmarks and spatial scenes [23]. |

| Retrosplenial Cortex / Precuneus | Translating egocentric and allocentric perspectives; episodic memory retrieval [23] [24]. |

| Medial Prefrontal Cortex | Decision-making and processing self-relevance [24]. |

| Parietal Cortex | Spatial transformation and attention to spatial features [25]. |

| Cingulate Gyrus | Monitoring performance and motor control [23] [26]. |

The parahippocampal place area and retrosplenial cortex are notably engaged across different navigation strategies, serving as central hubs for processing the spatial layout and landmarks of an environment [23]. Furthermore, regions like the medial prefrontal cortex and precuneus, which are part of the brain's "default mode network," are active not only during navigation but also during other forms of autobiographical and semantic memory retrieval, suggesting a role in integrating spatial information with broader self-referential and memory processes [24].

Neural Divergence: Signature Differences in Activation

While a core network is shared, the degree and pattern of activation within this network can differ significantly between real and virtual navigation. These divergences are primarily driven by the distinct sensory and motor inputs available in each context.

The Role of Physical Movement and Sensory Cues

A critical factor differentiating real and virtual navigation is the presence of physical, self-generated movement. A 2025 study directly compared an augmented reality (AR) task involving physical walking to a matched stationary desktop VR task. While performance was good in both, memory performance was significantly better in the walking condition [2]. Participants also reported that the walking condition was significantly easier, more immersive, and more fun than the stationary condition [2].

At a neural level, the inclusion of physical movement appears to enhance the fidelity of spatial representations. The same study found evidence for an increase in the amplitude of hippocampal theta oscillations during walking, a neural rhythm strongly associated with spatial encoding and movement in animal models [2]. This suggests that stationary VR, which lacks idiothetic (self-motion) cues from the vestibular and proprioceptive systems, may fail to fully engage the neural mechanisms that support natural navigation.

Implications for Hippocampal and Medial Temporal Lobe Engagement

The reduction in sensory cues and physical movement in many VR paradigms can lead to under-engagement of key regions. In rodents, place cell activity in the hippocampus is often disrupted or degraded in virtual environments compared to real ones [2]. Although evidence in humans is still accumulating, the finding that theta oscillations are less prominent in stationary VR [2] points to a similar phenomenon. This relative under-engagement of the hippocampal formation in VR may limit the extent to which findings from VR studies can be generalized to real-world navigation.

Furthermore, the type of navigation strategy employed also dictates neural recruitment patterns. The meta-analysis by Shima et al. found distinct activations for route-based versus survey-based navigation. Route-based navigation uniquely recruited the right inferior frontal gyrus, a region involved in sequential processing and cognitive control. In contrast, survey-based navigation (requiring a map-like perspective) uniquely engaged the thalamus and insula [23]. These strategy-specific differences can be confounded by the design of a VR task, potentially leading to divergent activation patterns when compared to a real-world task that more freely allows for strategy switching.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies Unveiled

To critically evaluate the evidence for neural overlap and divergence, it is essential to understand the methodologies of the key studies providing this data.

The "Treasure Hunt" Spatial Memory Task

This paradigm has been used in both its original VR form and a modified AR version to directly compare stationary and ambulatory navigation.

- Objective: To assess object-location associative memory with and without physical movement [2].

- Task Design: Participants encode the locations of objects hidden in chests within an environment. After a distractor task, they are prompted to recall and navigate to each object's location.

- Comparison: The task is performed in two matched conditions:

- Stationary VR: Participants navigate using a keyboard and joystick while seated.

- Ambulatory AR: Participants physically walk through a real-world space while viewing the task environment through a tablet or AR headset.

- Key Metrics: Spatial memory accuracy (error distance), subjective reports of ease and immersion, and in some cases, neural recordings like hippocampal theta oscillations [2].

Virtual Reality Path Integration for Early Alzheimer's Detection

This protocol uses immersive VR to isolate a specific navigation function that is highly dependent on the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus.

- Objective: To use path integration (PI) errors as a behavioral marker for early Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology [27].

- Task Design: Participants wear a head-mounted VR display in a virtual arena. They use a joystick to navigate from a start point to a target. After a brief delay, they must return to the start point using only self-motion cues, without any landmarks [27].

- Key Metrics: The primary outcome is the path integration error, calculated as the distance between the returned position and the true start position. This metric is then correlated with blood-based AD biomarkers (e.g., p-tau181, GFAP) and genetic risk factors (ApoE genotype) [27].

- Finding: PI errors significantly increase with age and correlate positively with plasma levels of AD-related proteins, suggesting VR-based navigation tasks can detect pre-clinical neurological changes [27].

The diagram below illustrates the typical workflow for a VR navigation study with integrated biomarker analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources and technologies used in the featured navigation research.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Navigation Neuroscience Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) VR Systems (e.g., Meta Quest 2) | Provides an immersive 3D visual experience, blocking out the real world to control sensory input during navigation tasks [27] [28]. |

| fMRI-Compatible Joysticks/Response Pads | Allows participants to navigate in a virtual environment while their brain activity is being recorded using functional magnetic resonance imaging [23]. |

| Blood Biomarker Assays (e.g., for p-tau181, GFAP) | Provides a molecular measure of Alzheimer's disease pathology, allowing researchers to correlate navigation performance with underlying neurobiological changes [27]. |

| Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) | A coordinate-based meta-analysis technique used to identify significant convergence of activation across multiple neuroimaging studies, helping to define core neural networks [25] [26]. |

| Augmented Reality (AR) Platforms | Enables the overlay of virtual objects onto the real world, facilitating the study of spatial memory and navigation with full physical movement in a controlled setting [2]. |

The fMRI evidence confirms that real and virtual navigation share a robust core neural network centered on the medial temporal lobe, parietal cortex, and prefrontal areas. This overlap validates the use of VR as a powerful tool for studying the fundamental principles of spatial cognition. However, the brain is not fooled; significant divergences exist. The absence of rich vestibular and proprioceptive feedback in stationary VR can lead to reduced hippocampal theta activity and potentially less robust spatial representations, manifesting as behavioral performance deficits compared to ambulatory navigation.

These findings have profound implications, especially for clinical applications. The success of VR-based path integration tasks in detecting early Alzheimer's disease biomarkers [27] [29] is a promising breakthrough. Future work should focus on developing more immersive VR systems that incorporate physical motion platforms or multisensory stimulation to better engage the hippocampus. Furthermore, combining fMRI with other techniques like EEG and MEG in these paradigms will help bridge the gap between the slow hemodynamic response and the fast neural dynamics of navigation. As VR technology becomes more advanced and accessible, it holds the potential to become a gold standard for the early, non-invasive detection of cognitive decline.

Leveraging VR Tools for Neuroscience Research and Clinical Translation

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful tool in functional neuroimaging, creating immersive environments that balance experimental control with ecological validity. This technology enables researchers to investigate complex neural processes—from spatial navigation to emotional experiences—within controlled laboratory settings. By simulating real-world scenarios, VR elicits robust brain activity patterns that traditional stimuli often fail to produce, providing new insights into brain function and dysfunction. This guide compares the implementation, capabilities, and experimental findings across major neuroimaging modalities integrated with VR, with particular attention to the ongoing debate comparing neural correlates of virtual versus real-world navigation.

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities with VR

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities with VR Integration

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Compatibility with VR Hardware | Key Measured Parameters | Representative Findings with VR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | High (mm-level) | Low (seconds) | Moderate (requires MR-compatible goggles) | BOLD signal changes | Stereoscopic presentation increases activation in visual area V3A; reduced DMN activity during awe experiences [30] [31] |

| EEG | Low (cm-level) | High (milliseconds) | High (minimal interference) | Spectral power (theta, beta, gamma bands), ERD/ERS | Increased beta/gamma power in occipital lobe during embodiment; theta power changes during spatial navigation [32] [2] |

| TMS-EEG | Moderate (targeted stimulation) | High (milliseconds) | Moderate (physical constraints) | Cortical excitability, effective connectivity | Investigating left DLPFC connectivity changes during awe experiences [31] |

| Deep Brain Recordings | High (single neuron) | High (milliseconds) | Limited (mobile implants in development) | Local field potentials, single-unit activity | Theta oscillation increases during physical navigation observed in hippocampal recordings [2] |

Table 2: Spatial Memory Performance: Physical vs. Virtual Navigation

| Parameter | Physical Navigation (AR) | Stationary VR | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Performance | Significantly better | Lower | p < 0.05 [2] |

| Participant Perception | Easier, more immersive, more fun | Less engaging | Significant difference in ratings [2] |

| Theta Oscillation Amplitude | Greater increase | Moderate increase | More pronounced during movement [2] |

| Neural Representation | Enhanced spatial signals | Disrupted/degraded | Consistent with animal models [2] |

| Experimental Control | Moderate | High | - |

| Idiothetic Cues | Full integration | Limited | Critical for spatial memory [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

VR-EEG-TMS Protocol for Investigating Awe (SUBRAIN Study)

The SUBRAIN project exemplifies integrated multimodal neuroimaging to study complex emotions. The protocol employs:

- Participant Flow: Screening → Enrollment → Pre-experimental assessment → VR experimental assessment → Post-experimental debriefing [31]

- VR Stimuli: Three immersive awe-inducing natural environments (forest, mountains, Earth view from space) plus one neutral control environment [31]

- Neural Recording: Continuous EEG during VR navigation, with TMS-EEG sessions immediately following each VR exposure [31]

- TMS Parameters: Stimulation targeting left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) based on its implicated role in awe processing and MDD-related circuitry [31]

- Subjective Measures: Self-reported questionnaires assessing emotional state changes post-VR exposure [31]

This protocol addresses technical challenges of integrating VR headsets with TMS coil positioning, utilizing the DLPFC as a target due to its accessibility and theoretical relevance to awe's potential effects on self-referential thinking [31].

fMRI Protocol for Visual Attention in Stereoscopic VR

This protocol examines how stereoscopic depth perception affects attentional networks:

- Display System: MR-compatible video goggles presenting alternating monoscopic and stereoscopic conditions [30]

- Task Design: Visual attention task alternating between active engagement trials and passive observation trials [30]

- fMRI Parameters: Standard BOLD acquisition during task performance, with focus on dorsal attention network and visual processing areas [30]

- Analysis Approach: Contrasting stereoscopic versus monoscopic conditions, with ROI analysis of area V3A [30]

The protocol capitalizes on fMRI's spatial resolution to pinpoint depth processing in visual cortex areas and their downstream effects on attention networks [30].

AR-VR Comparative Protocol for Spatial Memory

This approach directly compares physical and virtual navigation using matched environments:

- Task Design: "Treasure Hunt" object-location associative memory task with encoding, distractor, retrieval, and feedback phases [2]

- Conditions: Matched AR (ambulatory) and VR (stationary) implementations in the same environment layout [2]

- Measures: Memory accuracy, participant ratings (ease, immersion, enjoyment), and neural signals (theta oscillations) [2]

- Participant Groups: Healthy controls and epilepsy patients with chronic implants for intracranial recordings [2]

The protocol's strength lies in its direct within-subjects comparison of physical versus virtual navigation, controlling for environmental factors while varying movement conditions [2].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Multimodal VR Neuroimaging Protocol

Physical vs Virtual Navigation Neural Correlates

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for VR Neuroimaging

| Item | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Headsets | Create controlled, ecologically valid environments | HTC Vive, Oculus Rift [33] |

| MR-Compatible Goggles | Deliver stereoscopic stimuli within fMRI environment | Customized video goggles for MRI scanners [30] |

| EEG Cap Systems | Record electrical activity during VR immersion | 72-channel BioSemi; 129-channel Geodesic Net [34] |

| TMS Stimulators | Probe cortical excitability and connectivity | TMS systems targeting DLPFC [31] |

| BrainSuite Software | Process and visualize neuroimaging data | Surface model extraction, diffusion MRI processing [33] |

| OpenVR SDK | Develop custom VR applications for research | Valve's open-source VR development platform [33] |

| fMRIPrep Pipeline | Preprocess functional MRI data | Standardized, containerized fMRI processing [34] |

| EEGLAB Toolbox | Preprocess and analyze EEG data | Automated artifact rejection, ICA analysis [34] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Analyze multimodal brain network data | Deep learning framework for connectivity patterns [34] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of VR with neuroimaging modalities reveals both complementary strengths and persistent challenges. While fMRI provides superior spatial localization of VR-elicited brain activity, EEG captures the rapid temporal dynamics of cognitive processes during immersion. The direct comparison of physical versus virtual navigation highlights a fundamental limitation: stationary VR paradigms disrupt natural neural representations of space, likely due to reduced idiothetic cues [2].

Future developments should focus on increasing the mobility of recording techniques, particularly for EEG and deep brain recordings, to preserve natural movement during VR immersion. Furthermore, standardized protocols for multimodal integration—such as the simultaneous EEG-fMRI approaches being developed for major depressive disorder research [34]—could be adapted for VR paradigms. The ongoing technical challenges of combining VR headsets with neural recording and stimulation hardware [31] represent another critical area for innovation.

These methodological advances will be essential for resolving the central tension in VR neuroimaging: balancing experimental control with ecological validity to ensure that virtual environments engage the same neural mechanisms as real-world experiences.

Spatial navigation deficits represent one of the earliest and most sensitive markers of neurodegenerative disease progression, particularly in Alzheimer's disease (AD) [35]. The neural correlates of spatial navigation involve complex interactions between hippocampal formation, entorhinal cortex, and prefrontal regions—areas preferentially affected in early AD pathology [35]. Research contrasting virtual reality (VR) with real-world spatial navigation has revealed critical insights into both the clinical assessment of these deficits and the fundamental neural mechanisms underlying spatial cognition [2]. This review systematically compares VR and real-world spatial navigation assessment methodologies, their diagnostic accuracy, neural correlates, and clinical applications in neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions, providing researchers and clinicians with evidence-based guidance for implementing these tools in both research and clinical settings.

Comparative Analysis of Assessment Modalities

Diagnostic Accuracy of Digital Navigation Assessments

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Digital Spatial Navigation Assessments

| Assessment Tool | Study Population | Key Diagnostic Metrics | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Supermarket Test [35] | 107 participants (CN, aMCI) | Allocentric navigation deficits strongly correlated with CSF biomarkers (Aβ, p-tau) and hippocampal atrophy | Differentiates AD aMCI from non-AD aMCI; Independent of APOE ε4 status |

| SPACE [36] | n=300 (memory clinic & community) | AUC: 0.94 (no dementia vs mild), 0.95 (no dementia vs moderate), 0.91 (questionable vs mild) | Exceeded demographic models; Matched/surpassed traditional neuropsychological tests |

| Sea Hero Quest [21] | Older adults (54-74 years) | Predicted real-world navigation for medium difficulty environments (r=0.68, p<0.01) | Ecologically valid for older populations; Difficulty-dependent predictive power |

| VR-Based Interventions [37] | 1,365 MCI participants (30 RCTs) | Improved global cognition (MoCA: SMD=0.82, MMSE: SMD=0.83); Enhanced attention (DSB: SMD=0.61) | Semi-immersive VR most effective; Optimal session duration ≤60 minutes |

Neural Correlates of Spatial Navigation Deficits

Spatial navigation deficits in early Alzheimer's disease predominantly affect allocentric (world-centered) navigation rather than egocentric (self-centered) navigation [35]. This dissociation aligns with the early vulnerability of the hippocampal formation and entorhinal cortex in AD, regions critically involved in allocentric spatial processing [35]. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (amyloid-β1-42, phosphorylated tau181) and medial temporal lobe atrophy demonstrate strong associations with allocentric navigation performance, highlighting the potential of spatial navigation assessment as a sensitive digital marker of underlying pathology [35].

The APOE ε4 allele, while a significant genetic risk factor for AD, does not appear to directly influence spatial navigation performance beyond its association with AD pathology, suggesting that navigational deficits are primarily driven by the disease process itself rather than genetic predisposition alone [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Virtual Supermarket Test Protocol

The Virtual Supermarket Test (VST) employs a carefully controlled protocol to dissociate allocentric and egocentric navigation strategies [35]:

- Environment: Participants navigate a virtual supermarket environment presented on a standard desktop computer or through immersive VR systems.

- Allocentric Task: Participants learn and recall object locations from a fixed, overhead perspective requiring cognitive mapping of the environment.

- Egocentric Task: Participants navigate from a first-person perspective, remembering sequences of turns and pathways.

- Assessment Phases:

- Encoding Phase: Participants explore the environment and learn target locations.

- Recall Phase: Participants indicate remembered locations from different starting positions.

- Transfer Tests: Assess ability to apply spatial knowledge in novel navigation tasks.

- Outcome Measures: Primary metrics include path efficiency, accuracy of location recall, navigation time, and strategy selection.

This protocol has demonstrated particular sensitivity to early AD pathology, with allocentric deficits strongly correlating with CSF biomarker levels and hippocampal volume reduction [35].

Sea Hero Quest Ecological Validation Protocol

The ecological validation of Sea Hero Quest provides a model for establishing real-world relevance of digital navigation assessments [21]:

- Virtual Task: Participants complete wayfinding levels in Sea Hero Quest mobile game, navigating a boat through virtual environments to locate target destinations.

- Real-World Task: Participants complete analogous wayfinding tasks in the Covent Garden area of London, using GPS tracking to measure navigation performance.

- Performance Metrics:

- Route efficiency (actual distance traveled vs. optimal path)

- Navigation time

- Success rate in reaching destinations

- Strategic wayfinding decisions

- Population: Validation included both young (18-35) and older (54-74) adults to establish age-specific ecological validity.

- Key Finding: Virtual navigation performance predicted real-world performance for medium-difficulty environments in older adults, supporting the ecological validity of digital assessments in this population [21].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Spatial Navigation Assessment Methodology

VR versus Real-World Neural Processing

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Navigation Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Assessment Platforms | Virtual Supermarket Test (VST), Sea Hero Quest, SPACE | Quantifying allocentric/egocentric navigation deficits; Early disease detection | VST specialized for clinical populations; Sea Hero Quest for large-scale screening |

| Immersive VR Systems | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs), CAVE systems, CAREN | High-immersion navigation tasks; Motor-cognitive integration | Motion sickness risk in full-immersion; CAREN integrates motion capture |

| Augmented Reality Platforms | Microsoft HoloLens, Tablet-based AR | Studying physical navigation with virtual elements; Ecological validity | Enables natural movement with controlled stimuli; Theta oscillation studies [2] |

| Biomarker Assays | CSF Aβ42, p-tau181, t-tau; Amyloid PET | Correlating navigation deficits with AD pathology | CSF provides direct pathological measures; PET offers spatial distribution |

| Neuroimaging | Structural MRI (T1-weighted), Functional MRI | Hippocampal volumetry; Activation patterns during navigation | High-resolution MRI for atrophy quantification; fMRI for network engagement |

| Genetic Analysis | APOE genotyping, Whole-genome sequencing | Stratifying genetic risk factors; Personalized assessment | APOE ε4 increases AD risk but doesn't directly affect navigation [35] |

Comparative Effectiveness Across Modalities

Table 3: VR versus Real-World Navigation Assessment

| Parameter | Virtual Reality Assessment | Real-World Assessment | Augmented Reality Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Control | High control over environment and variables [38] | Limited control over external factors | Moderate control with real-world context |

| Ecological Validity | Variable; improves with immersion level [21] | High ecological validity [2] | High ecological validity with control [2] |

| Physical Movement | Typically limited (stationary) [2] | Full physical navigation | Full physical navigation with virtual elements |

| Scalability | High potential for large-scale deployment [36] | Labor-intensive and time-consuming | Moderate scalability with portable systems |

| Neural Engagement | Partial hippocampal network activation [2] | Full hippocampal and medial temporal lobe engagement | Enhanced theta oscillations with movement [2] |

| Spatial Memory Performance | Moderate accuracy and retention [2] | Superior memory encoding and recall [2] | 32% improvement over stationary VR [2] |

| Participant Experience | Reported as less immersive and engaging [2] | Rated as easier, more immersive, and enjoyable [2] | High enjoyment and engagement reported |

| Clinical Implementation | Suitable for clinic-based assessment [36] | Limited by practical constraints | Emerging technology with clinical potential |

Spatial navigation assessment represents a paradigm shift in early detection and monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases. Digital tools like the Virtual Supermarket Test, SPACE, and Sea Hero Quest offer validated, scalable alternatives to traditional cognitive assessments, with particular strength in identifying allocentric navigation deficits as early markers of AD pathology [35] [36] [21].

The integration of physical movement through augmented reality platforms demonstrates enhanced ecological validity and improved spatial memory performance compared to stationary VR tasks [2]. Future research directions should focus on standardizing assessment protocols across platforms, validating predictive value for disease progression, and developing integrated biomarkers combining spatial navigation performance with molecular and imaging biomarkers.

For clinical researchers, the evidence supports implementing spatial navigation assessment as a complementary tool alongside traditional cognitive tests, particularly for early detection of Alzheimer's disease and differentiation of dementia subtypes. The ongoing technological advancements in VR and AR platforms promise increasingly sophisticated, accessible, and clinically useful tools for quantifying spatial deficits across neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions.

The use of virtual reality (VR) in cognitive rehabilitation and spatial memory research represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience and neuropsychology. This technology enables the creation of interactive, multisensory environments for studying spatial cognition and treating cognitive impairments within a safe, controlled setting [39]. A core focus of contemporary research lies in comparing neural correlates and behavioral outcomes between virtual and real-world navigation. Understanding these relationships is critical for validating VR as an ecologically valid tool for both scientific discovery and clinical rehabilitation [40]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of VR and real-world paradigms, detailing experimental protocols, neural mechanisms, and practical research tools for professionals in the field.

Comparative Analysis: VR vs. Real-World Spatial Navigation

Behavioral and Performance Metrics

Extensive research has quantified performance differences in spatial tasks conducted in virtual versus real environments. The table below summarizes key behavioral findings from comparative studies.

Table 1: Behavioral Performance in Real vs. Virtual Environments

| Performance Metric | Real Environment (RE) Findings | Virtual Environment (VE) Findings | Research Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Memory Accuracy | Significantly better memory for object locations [2]. | Reduced spatial memory performance compared to RE [16]. | PMC12247154 [2] |

| Navigation Efficiency | More direct pathways, less backtracking [16]. | Longer distances covered, more errors made [16]. | ScienceDirect [16] |

| Task Completion Time | Shorter time to complete navigational tasks [16]. | Longer task completion times [16]. | ScienceDirect [16] |

| Subjective Experience | Reported as easier, more immersive, and more fun [2]. | Higher perceived cognitive workload and task difficulty [16]. | PMC12247154 [2], ScienceDirect [16] |

Neural Correlates and Physiological Measures

The neural underpinnings of spatial navigation have been extensively studied, revealing both overlaps and divergences between real and virtual experiences.

Table 2: Neural Correlates in Real vs. Virtual Navigation

| Neural Measure | Real Environment (RE) Findings | Virtual Environment (VE) Findings | Research Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal Theta Oscillations | Increase in amplitude associated with physical movement [2]. | Theta activity is less pronounced, particularly in stationary VR [2]. | PMC12247154 [2] |

| Spatial Representation Networks | Engages hippocampus, retrosplenial cortex, entorhinal cortex [40]. | Similar networks active, but representations may be less flexible [40]. | PMC10602022 [40] |

| Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) | N/A | VR elicits stronger EEG energy in occipital, parietal, and central regions [41]. | PMC10346206 [41] |

| Sense of Presence | N/A (Inherent) | A key factor for engagement; influenced by immersion level [39]. | PMC10813804 [39] |

Experimental Protocols in VR Spatial Memory Research

The Treasure Hunt Task (Object-Location Associative Memory)

This paradigm is used to assess how individuals form and recall associations between objects and specific locations.

- Objective: To evaluate spatial memory performance in matched Augmented Reality (AR) and desktop VR conditions [2].

- Protocol:

- Encoding Phase: Participants navigate to a series of treasure chests positioned at random spatial locations. Upon reaching a chest, it opens to reveal an object whose location must be remembered [2].

- Distractor Phase: A short task (e.g., catching an animated animal) prevents memory rehearsal and moves the participant away from the last object's location [2].

- Retrieval Phase: Participants are shown an object and must navigate to and indicate its remembered location [2].

- Feedback Phase: Participants view correct locations alongside their responses and receive accuracy scores [2].

- Key Variables: Number of objects per trial, condition (AR with physical walking vs. stationary VR), and response accuracy [2].

Virtual vs. Real-World Environment Comparison

This protocol assesses the ecological validity of VEs by directly comparing them to identical real-world settings.

- Objective: To determine the transferability of navigational data and user responses from VEs to real-world contexts [16].

- Protocol:

- Environment Creation: A multi-level educational facility is digitally replicated to create a high-fidelity VE [16].

- Task Assignment: Participants in both real and virtual conditions complete identical navigational tasks (e.g., wayfinding between specific points) [16].

- Data Collection: Metrics include path efficiency, number of wrong turns, task completion time, and backtracking frequency [16].

- Subjective Measures: Participants complete surveys on perceived uncertainty, cognitive workload, and task difficulty [16].

- Key Variables: Age group (younger vs. older adults), environment (RE vs. VE), and complexity of navigational tasks [16].

Blindfolded Pointing and Walking Tasks

This protocol isolates spatial orientation skills from continuous visual input.

- Objective: To compare spatial orientation and memory-guided navigation between real and virtual environments [42].

- Protocol:

- Learning Phase: Participants observe the location of sport-specific objects in a room for 15 seconds [42].

- Recall Phase: Participants are blindfolded and asked to either walk to the remembered object location or point in its direction [42].

- Conditions: The task is performed in both a real room and a VR replica of the same room [42].

- Data Analysis: Primary measures are pointing accuracy and the precision of walking pathways to target objects [42].

Signaling Pathways and Neural Workflows in Spatial Memory

The formation and retrieval of spatial memories involve complex neural interactions. The diagram below illustrates the primary workflow from sensory input to memory consolidation, highlighting key brain structures and signaling pathways.

Diagram Title: Neural Workflow of Spatial Memory Formation

This workflow illustrates how sensory cues are processed by two primary neural systems: the hippocampus-centered allocentric system (encoding relationships between environmental cues to create a "map-like" representation) and the striatum-centered egocentric system (encoding routes and directions relative to oneself) [40]. The integration of these systems enables flexible navigation and memory. Critically, physical movement during real-world navigation enhances hippocampal theta oscillations, a rhythm linked to neural plasticity and memory formation, which is often diminished in stationary VR setups [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing experiments in VR spatial navigation and cognitive rehabilitation, the following tools and technologies are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for VR Spatial Memory Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Systems | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) like Oculus Rift/Quest, HTC Vive [39] | Provides a fully immersive 3D experience; critical for inducing a sense of presence and studying ecologically valid behaviors. |

| Non-Immersive/Semi-Immersive Systems | Desktop computers, CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) systems [39] | Enables research with varying levels of immersion; desktop systems are widely compatible with neuroimaging equipment. |

| Neuroimaging & Physiology | EEG, fMRI, eye-tracking, motion capture systems [2] [42] [41] | Records neural activity (e.g., theta oscillations, ERPs), gaze, and body movement synchronously with VR navigation. |

| Software Platforms | Unity3D, Blender [42] | Used to create and control custom virtual environments, allowing precise manipulation of experimental variables. |

| Spatial Memory Tasks | Treasure Hunt, Object Location Task, Virtual Morris Water Maze [2] [40] | Standardized behavioral paradigms to assess object-location associative memory and navigational strategies. |

| Subjective Measure Questionnaires | NASA-TLX (Task Load Index), Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ), Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) [41] [43] | Quantifies user experience, including cognitive load, sense of presence, and adverse effects like cybersickness. |

The comparative data indicates that while VR successfully engages core spatial memory networks, real-world navigation with physical movement consistently leads to superior memory performance and enhanced neural signatures like hippocampal theta rhythms [2]. The primary advantages of VR—experimental control, reproducibility, and compatibility with neuroimaging—are undeniable [16]. However, its limitations, particularly the reduction of idiothetic (self-motion) cues and the potential for increased cognitive load, must be factored into experimental design and clinical application [40].

Future developments are likely to focus on bridging this fidelity gap. The integration of Augmented Reality (AR), which overlays virtual elements onto the real world, shows great promise for combining the experimental control of VR with the rich sensory input of real-world navigation [2]. Furthermore, advances in wearable neurotechnology and the development of more sophisticated, adaptive VR environments that respond to user behavior in real-time will further enhance the ecological validity and therapeutic potential of VR-based cognitive rehabilitation [39] [43].

The study of spatial navigation has been profoundly transformed by the adoption of virtual reality (VR) technologies, which offer unprecedented experimental control and data collection capabilities. However, this shift has raised critical questions about the ecological validity of VR-based findings and their transferability to real-world contexts [16]. Central to this debate is understanding how dynamic social cues—particularly human agents—influence spatial exploration and knowledge acquisition, aspects that traditional VR paradigms often overlook. While static landmarks have been extensively studied in spatial cognition research, the neural correlates of navigating social environments remain less understood [44].

This comparison guide examines novel experimental paradigms that address this gap by incorporating dynamic human agents into navigation studies. We objectively evaluate evidence from both VR and real-world studies, with a specific focus on how social cues shape exploration patterns, memory formation, and neural synchronization. The findings have significant implications for multiple fields, including neuroscience research on spatial memory disorders and the development of digital therapeutics for conditions like Alzheimer's disease, where spatial disorientation is an early symptom.

Comparative Performance Data: Virtual Reality vs. Real-World Navigation

Behavioral and Cognitive Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative performance metrics between virtual reality and real-world navigation across key studies.

| Performance Metric | Virtual Reality Findings | Real-World/AR Findings | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Memory Accuracy | Significantly lower in stationary VR; older adults' VR navigation on par with younger users [16]. | Significantly better with physical movement (AR walking condition) [2]. | Object-location associative memory task [2] [16] |

| Navigation Efficiency | Longer distances, more errors, longer task completion times [16]. | More efficient path planning with physical movement cues [2]. | Multi-level building navigation [16] |

| User Experience & Engagement | Higher perceived cognitive workload and task difficulty [16]. | Reported as significantly easier, more immersive, and more fun [2]. | Post-task questionnaires [2] [16] |

| Impact of Social Cues | Contextual agents improved pointing accuracy toward buildings; agents and buildings competed for visual attention [44]. | Not directly measured in real-world social navigation. | Virtual city exploration with human avatars [44] |

Neural Correlates and Physiological Measures

Table 2: Neural correlates and physiological measures compared across navigation environments.

| Neural/Physiological Measure | Virtual Reality Findings | Real-World/AR Findings | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal Theta Oscillations | Theta increases during movement less pronounced in stationary VR [2]. | Significant increase in amplitude during walking; clearer movement-related signals [2]. | Linked to spatial memory encoding and retrieval [2] |

| Inter-Brain Synchrony (IBS) | IBS occurs at levels comparable to real world in collaborative tasks; positively correlated with performance [45]. | Established neural alignment during social interactions and collaboration [45]. | Measure of collaborative efficiency and shared attention [45] |

| Cognitive Load & Stress Markers | Investigated using EDA, ECG, cortisol; inconsistent effects on performance [46]. | More natural sensorimotor integration potentially reduces cognitive load. | Implicit processes mediating navigation performance [46] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The "Treasure Hunt" Spatial Memory Paradigm

This protocol tests object-location associative memory across matched Augmented Reality (AR) and stationary desktop VR conditions [2].

- Participant Groups: Healthy adults and epilepsy patients (including mobile patients with neural implants).

- Task Structure:

- Encoding Phase: Participants navigate to treasure chests positioned at random spatial locations. Each chest opens to reveal an object whose location must be remembered.

- Distractor Phase: An animated rabbit runs through the environment; participants chase it to prevent memory rehearsal and displace them from the last location.

- Retrieval Phase: Participants are shown object names/images and must indicate their remembered locations.

- Feedback Phase: Participants view correct locations alongside their responses with accuracy scoring.

- Implementation: AR condition uses handheld tablets for real-world navigation; VR condition uses standard desktop screen and keyboard.

- Data Collection: 20 trials per condition (~50 spatial memory targets each), plus subjective experience questionnaires.

- Neural Recording: In a case study, continuous hippocampal local field potential data was streamed from a mobile epilepsy patient with a chronic neural implant.

Virtual City Exploration with Human Agents

This paradigm examines how human agents influence spatial exploration and knowledge acquisition [44].

- Virtual Environment: One-square-kilometer VR city ("Westbrook") with 236 buildings (26 public, 26 residential with graffiti markers, 180 non-marked).

- Agent Design:

- Contextual Agents: Perform context-relevant actions (e.g., holding toolbox in front of hardware store).

- Acontextual Agents: Hold resting position without object interaction.

- Experimental Conditions:

- Experiment 1: Contextual agents placed in congruent public building contexts; acontextual agents at residential buildings.

- Experiment 2: Agent-building congruency disrupted to isolate agent-type effects.

- Procedure:

- Five 30-minute free exploration sessions (150 minutes total).

- Spatial knowledge tested via pointing tasks in separate session.

- Navigation tracking includes walking behavior, coverage, decision-point strategies, and visual attention.