Active Sensing in Virtual Reality: Transforming Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of Virtual Reality (VR) as an active sensing platform in biomedical research and drug development.

Active Sensing in Virtual Reality: Transforming Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Virtual Reality (VR) as an active sensing platform in biomedical research and drug development. Targeting researchers, scientists, and pharmaceutical professionals, it details how VR enables the interactive exploration and manipulation of complex biological systems. The scope spans from foundational principles of VR-enabled active sensing to its methodological applications in molecular visualization and clinical trial optimization. It also addresses critical challenges in model fidelity and data integration, and provides a framework for validating VR systems against traditional methods, offering a comprehensive guide to leveraging immersive technologies for scientific advancement.

What is VR-Enabled Active Sensing? Core Principles for Scientific Inquiry

Defining Active Sensing in Virtual Environments

Active sensing represents a fundamental framework for understanding how intelligent agents strategically control their sensors to extract task-relevant information from their environment. In virtual environments, this process becomes both measurable and manipulable, offering unprecedented opportunities for research and application. This technical guide examines the core principles, mechanisms, and implementations of active sensing within virtual reality systems, with particular emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research and drug development. By synthesizing computational theories with practical implementations, we provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for leveraging active sensing paradigms in virtual environments to advance scientific discovery.

Active sensing describes the closed-loop process whereby an agent directs its sensors to efficiently gather and process task-relevant information [1]. Unlike passive sensing, where information is received without deliberate sensor manipulation, active sensing involves strategic movements specifically designed to reduce uncertainty about environmental variables or system states. This paradigm has profound implications for virtual reality (VR) applications, where sensorimotor contingencies can be precisely controlled and measured.

The theoretical foundation of active sensing rests upon two complementary processes: perception, through which sensory information is processed to form inferences about the world, and action, through which agents select optimal sampling strategies to acquire useful information [1]. In virtual environments, this closed loop enables researchers to study and exploit the symbiotic relationship between movement and information gain under controlled conditions. The integration of active sensing principles with VR technologies is particularly transformative for domains requiring visualization and manipulation of complex 3D data, such as structure-based drug design [2] [3].

Theoretical Framework

Computational Foundations

Active sensing can be formally described as an approximation to the general problem of exploration in reinforcement learning frameworks [1]. The process involves an ideal observer that extracts task-relevant information from sensory inputs, and an ideal planner that specifies actions leading to the most informative observations [1].

The mathematical formulation centers on the Bayesian ideal observer, which performs inference about environmental states using Bayes' rule:

ℙ(x|z₀:t,M) ∝ ℙ(z₀:t|x,M)ℙ(x|M)

where x represents environmental states, z₀:t represents sensory inputs from time 0 to t, and M represents the internal model of the environment and sensory apparatus [1].

Information Maximization Principle

A fundamental proxy for evaluating action selection in active sensing is Shannon information, which quantifies the expected reduction in uncertainty about state x:

ℐ(x,zₜ₊₁|a) = ℋ(x|z₀:t,M) - ⟨⟨ℋ(x|z₀:t₊₁,M)⟩ℙ(zₜ₊₁|a,x,M)⟩ℙ(x|z₀:t,M)

where ℋ(x) represents the entropy of the probability distribution ℙ(x), quantifying uncertainty about x [1]. The information-maximizing ideal planner simply selects the action a that maximizes this information gain:

aₜ₊₁ = argmaxₐ ℐ(x,zₜ₊₁|a)

This formalization provides a principled approach to understanding how virtual agents can optimize their sensing strategies to extract maximal information from their environments.

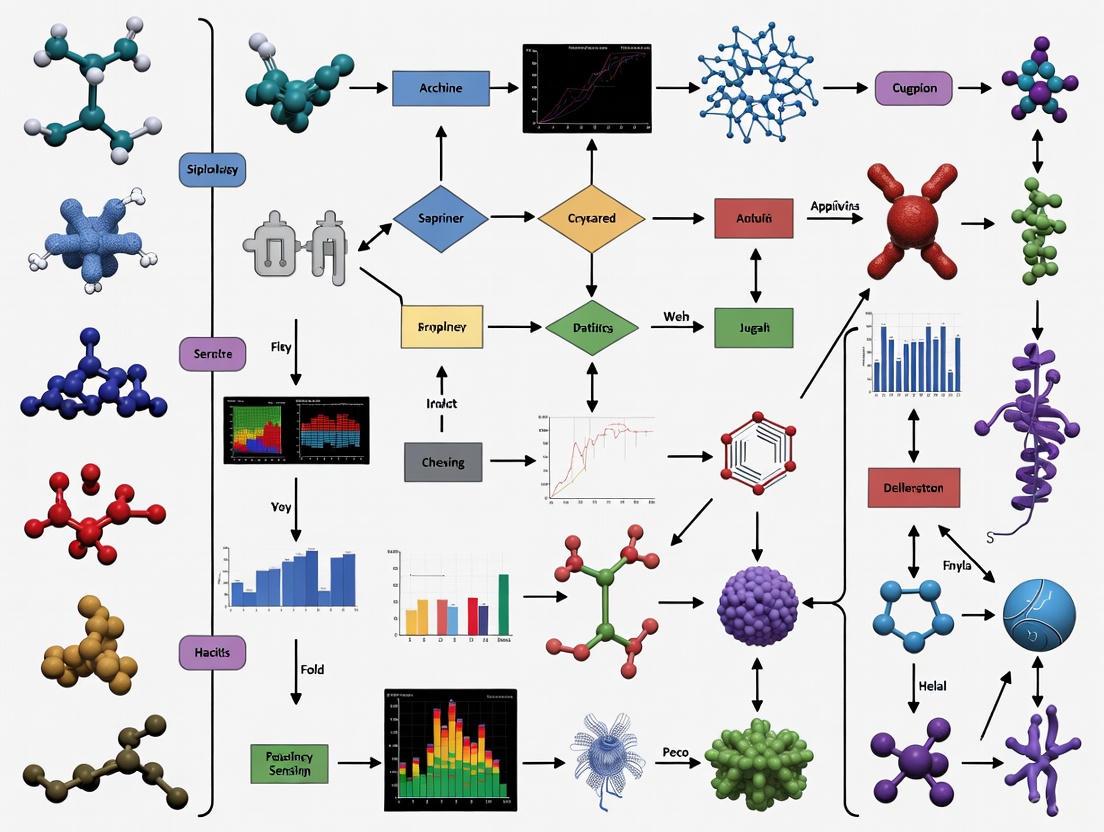

Figure 1: Active Sensing Closed-Loop Framework. This diagram illustrates the fundamental perception-action cycle underlying active sensing, where beliefs inform actions that modify sensory inputs.

Active Sensing in Virtual Reality Systems

Implementation in Immersive Environments

Virtual reality implementations of active sensing leverage head-mounted displays (HMDs) and motion tracking systems to create controlled sensorimotor loops [4]. Multi-user VR platforms further extend these capabilities by enabling collaborative active sensing scenarios, where multiple agents can simultaneously gather and share information within shared virtual spaces [5]. These platforms have proven particularly valuable in industrial contexts, where they facilitate intuitive exploration of complex data structures [4].

In pharmaceutical applications, VR enables researchers to visualize and manipulate molecular structures in three dimensions, engaging in active sensing behaviors such as rotating protein-ligand complexes, examining binding sites from multiple viewpoints, and simulating molecular dynamics through controlled movements [2] [3]. This immersive interaction paradigm transforms how scientists extract information from complex biochemical data.

Levels of Interaction in Drug Design

Three distinct levels of interaction characterize active sensing applications in structure-based drug design within virtual environments [2] [3]:

Level 1: Visualization and Inspection - Researchers manipulate viewpoint and orientation to examine molecular structures from optimal angles, employing natural head and hand movements to resolve spatial ambiguities.

Level 2: Molecular Manipulation - Users directly manipulate molecular components through gesture-based controls, testing hypotheses about binding affinities and structural compatibilities through purposeful sensorimotor engagement.

Level 3: Dynamic Simulation Control - Experts actively control parameters of molecular dynamics simulations, strategically sampling conformational spaces to identify stable binding configurations and reaction pathways.

Table 1: Active Sensing Interaction Levels in VR Drug Design

| Interaction Level | Primary Sensing Actions | Information Gained | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visualization & Inspection | Viewpoint manipulation, rotation, zoom | Spatial relationships, molecular geometry | 3D visualization, head tracking |

| Molecular Manipulation | Direct manipulation, docking, positioning | Binding compatibility, steric constraints | Hand tracking, haptic feedback |

| Dynamic Simulation Control | Parameter adjustment, sampling strategy | Energy landscapes, kinetic properties | Real-time simulation, interactive rendering |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

BOUNDS Computational Pipeline

The BOUNDS (Bounding Observability for Uncertain Nonlinear Dynamic Systems) pipeline provides a empirical methodology for quantifying how sensor movement contributes to estimation performance in active sensing scenarios [6]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing active sensing in virtual environments, where state trajectories can be precisely recorded and analyzed.

Protocol Implementation:

State Trajectory Collection - Record time-series state trajectories (X̃) comprising sequences of observed state vectors (x̃ₖ) that describe agent/sensor movement and environmental variables in the virtual environment [6].

Model Definition - Define a model incorporating: (i) inputs controlling locomotion, (ii) basic physical properties, and (iii) sensory dynamics representing what the agent measures [6].

Observability Matrix Calculation - Compute the empirical observability matrix (O) for nonlinear systems using measured or simulated state trajectories [6].

Fisher Information Matrix Computation - Calculate the Fisher information matrix (F) associated with O to account for sensor noise properties [6].

Cramér-Rao Bound Application - Apply the Cramér-Rao bound under rank-deficient conditions to quantify observability with meaningful units [6].

Active Sensing Motif Identification - Iterate the pipeline along dynamic state trajectories to identify patterns of sensor movement that increase information for individual state variables [6].

Figure 2: BOUNDS Computational Pipeline. This workflow illustrates the empirical process for quantifying observability and identifying active sensing patterns in virtual environments.

Systematic Evaluation Framework

Comprehensive assessment of human factors in VR active sensing environments requires standardized methodologies [4]. A systematic literature review approach based on PRISMA 2020 guidelines can identify and categorize key evaluation metrics and experimental designs [4].

Experimental Design Protocol:

Research Question Formulation - Define specific questions addressing how human factors influence and are influenced by active sensing in VR environments [4].

Search Strategy Implementation - Execute structured searches across electronic databases using tailored search equations combining terms for: (i) virtual reality/VR, (ii) industry 4.0/5.0 context, (iii) human factors/cognition/UX, and (iv) evaluation/assessment [4].

Study Selection - Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria focusing on peer-reviewed journal articles within appropriate timeframes relevant to current VR technological capabilities [4].

Data Extraction and Synthesis - Extract data on human factors, metrics, and experimental outcomes, then synthesize to identify patterns and relationships [4].

Quality Assessment - Evaluate selected studies for potential biases and methodological limitations [4].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Molecular Visualization and Manipulation

Virtual reality active sensing systems enable researchers to visualize and manipulate complex molecular structures in immersive 4D environments [2] [3]. This capability transforms structure-based drug design by allowing intuitive exploration of protein-ligand complexes through natural sensorimotor interactions [2]. Case studies in COVID-19 research have demonstrated VR's potential for rapid molecular structure analysis, where researchers actively sensed structural features of viral proteins to identify potential drug targets [2] [3].

The active sensing paradigm in molecular visualization allows researchers to employ embodied cognition strategies, using physical movements to resolve spatial ambiguities that remain opaque in traditional 2D representations. This approach leverages human spatial reasoning capabilities to solve complex structural biological problems through strategic viewpoint control and molecular manipulation [2].

Industrial Perspectives and Implementation Challenges

Conversations with pharmaceutical industry experts reveal cautious optimism about VR's potential in drug discovery, while highlighting significant implementation challenges [2] [3]. Key barriers include integration with existing workflows, hardware ergonomics, and establishing synergistic relationships between VR and expanding artificial intelligence tools [2].

Industry professionals identify active sensing interfaces as particularly promising for collaborative drug design sessions, where multi-user VR environments enable research teams to collectively explore molecular interactions and formulate structural hypotheses [3]. However, widespread adoption requires addressing technical challenges related to simulation fidelity, interaction precision, and seamless integration with computational chemistry pipelines [2] [3].

Table 2: Active Sensing Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

| Application Domain | Active Sensing Actions | Research Impact | Implementation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand Docking | Molecular rotation, binding site exploration | Improved understanding of binding mechanisms | Research validation |

| Structure-Based Drug Design | Conformational sampling, interactive modification | Accelerated lead optimization | Early adoption |

| COVID-19 Research | Spike protein analysis, binding site identification | Rapid target identification | Case studies demonstrated |

| Collaborative Drug Design | Multi-user molecular inspection, shared perspective control | Enhanced team-based problem solving | Prototype development |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Active Sensing in Virtual Environments

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Active Sensing Research |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | Meta Quest, HTC Vive, Sony PlayStation VR | Provide immersive display and tracking capabilities for sensorimotor loops [4] |

| Multi-User VR Platforms | Custom collaborative environments | Enable shared active sensing experiences for team-based research [5] |

| Molecular Visualization Software | Custom VR-enabled molecular viewers | Facilitate 3D manipulation of chemical structures [2] [3] |

| Observability Analysis Tools | BOUNDS/pybounds Python package | Quantify information gain from sensor movements [6] |

| Motion Tracking Systems | Inside-out tracking, lighthouse systems | Capture precise movement data for sensing action analysis [4] |

| Data Analysis Frameworks | Fisher information calculators, Bayesian estimators | Process sensor data and quantify information extraction [1] [6] |

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The convergence of active sensing principles with virtual reality technologies presents numerous research opportunities across scientific domains. In pharmaceutical research, developing more sophisticated molecular manipulation interfaces that provide haptic feedback and physicochemical simulation capabilities represents a promising direction [2]. Integration with artificial intelligence systems creates opportunities for hybrid intelligence approaches, where human active sensing strategies complement machine learning algorithms in analyzing complex biological data [2] [3].

Advancements in hardware ergonomics and display technologies will address current limitations in resolution, field of view, and comfort, enabling longer, more productive active sensing sessions [4]. Standardized assessment frameworks for evaluating human factors in VR active sensing environments will facilitate more systematic research and application development [4].

From a computational perspective, extending the BOUNDS framework to handle increasingly complex state estimation problems will expand applications in virtual environment design and analysis [6]. The Augmented Information Kalman Filter (AI-KF) approach, which combines data-driven state estimation with model-based filtering, demonstrates how active sensing principles can be implemented in practical estimation algorithms [6].

As these technologies mature, active sensing in virtual environments is poised to transform research methodologies across scientific disciplines, particularly in complex 3D data analysis domains like drug discovery, structural biology, and materials science [2] [3].

The study of human perception and behavior has long relied on passive observation paradigms, where data is collected from subjects reacting to static, laboratory-controlled stimuli. This whitepaper delineates a fundamental paradigm shift toward interactive manipulation, enabled by advanced virtual reality (VR) technologies and sophisticated sensing techniques. Within VR environments, participants are no mere observers but active agents whose sensing and manipulation behaviors can be tracked, quantified, and analyzed in real-time. This shift is critically examined through its application in affective computing and immersive analytics, demonstrating enhanced ecological validity, richer data acquisition, and the emergence of novel experimental frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals.

Traditional research methodologies in neuroscience and psychology have been dominated by passive induction paradigms. In these settings, subjects are exposed to stimuli—such as images or videos on a screen—while their physiological responses are measured. While controlled, this approach lacks ecological validity; the induced emotional changes differ significantly from the active, self-generated emotions experienced in real-world scenarios [7]. This limitation poses a significant challenge for fields like drug development, where understanding genuine human responses is paramount.

The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) marks a transition to active induction paradigms. VR provides a highly immersive and realistic virtual environment, allowing for the assessment of emotional experiences and behaviors in a more naturalistic context [7]. This evolution from passive observation to interactive manipulation represents a profound methodological shift. It moves the subject from a reactive entity to an active participant who can sense, manipulate, and alter a virtual environment, thereby generating a richer, more complex, and ecologically valid dataset for analysis. This whitepaper explores the technical underpinnings, experimental evidence, and practical implementations of this shift.

Theoretical Foundations: From Passive to Active Paradigms

The distinction between passive and active research paradigms is foundational to this discussion.

Passive Observation Paradigms: Characterized by a one-directional flow of information. The laboratory environment presents a stimulus, and the researcher measures the subject's response using tools like Electroencephalography (EEG) or functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). This method is often critiqued for its weak induction effects and its disconnection from the complexities of real-life situations [7]. The data acquired, while precise, may not fully capture the dynamism of natural human behavior.

Interactive Manipulation Paradigms: Founded on the principles of active sensing, where perception is guided by action. In a VR environment, participants use motor actions to control sensing apparatuses. For instance, they might turn their heads to look around a virtual space or use haptic controllers to manipulate virtual objects. This process generates a closed-loop feedback system between the participant and the environment [8]. This paradigm provides a highly immersive experience, evoking emotions and behaviors more naturally and authentically [7]. It allows researchers to study not just the final response, but the entire process of sensory-guided motor planning and execution.

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Comparisons

The superiority of active, VR-based paradigms is supported by empirical evidence across multiple domains. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from comparative studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Passive vs. Active VR Research Paradigms

| Research Domain | Experimental Task | Key Metric | Passive Paradigm Result | Active VR Paradigm Result | Significance & Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Emotion Recognition [7] | Emotion classification using EEG signals | Classification Performance | High performance on lab-collected data, but lacks ecological validity and transferability. | Robust classification performance; model (EmoSTT) transferred well between different emotion elicitation paradigms. | The VR-based active paradigm provides data that leads to more generalizable and robust computational models. |

| Graph Data Analytics [9] | Cluster search task in a graph | Task Efficiency & Error Rate | Efficient manipulation on 2D touch displays, but limited by display space and lack of immersion. | More efficient task performance with user-controlled transformation; lower error rates with constant transformation. | User-controlled manipulation in immersive 3D space enhanced task efficiency, demonstrating the value of interactive exploration. |

| Crowd Dynamics Research [5] | Study of pedestrian movement patterns | Data Validity & Control | Field observations (video) have high external validity but lack control and are difficult to quantify. | Controlled experiments with high external validity; enables study of dangerous scenarios safely. | VR provides an optimal balance between experimental control and ecological validity for complex behavioral studies. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: EEG-Based Emotion Recognition in VR

The following protocol outlines the methodology for conducting an active paradigm emotion recognition study, as exemplified in the research by Beihang University [7].

1. Objective: To collect electroencephalography (EEG) data correlated with emotional states elicited within an immersive Virtual Reality environment.

2. Materials and Reagents: - VR Head-Mounted Display (HMD): A high-fidelity HMD (e.g., Meta Quest 3, Apple Vision Pro) capable of rendering immersive videos. - EEG Acquisition System: A multi-channel EEG system with a compatible electrode cap (e.g., 32 or 64 channels). - Stimuli: A curated set of 360-degree VR videos designed to elicit specific emotional states (e.g., joy, fear, calmness). - Software: VR presentation software, EEG recording software, and data analysis platforms (e.g., Python with MNE, EEGLAB).

3. Experimental Procedure: - Step 1: Participant Preparation. Recruit participants according to the approved ethical guidelines. After obtaining informed consent, fit the participant with the EEG electrode cap, ensuring impedances are below 5 kΩ. Then, equip the participant with the VR HMD. - Step 2: Baseline Recording. Record a 5-minute resting-state EEG with eyes open and closed in a neutral VR environment (e.g., a plain, virtual room). - Step 3: VR Stimulus Presentation. Present the series of VR videos to the participant in a randomized or counterbalanced order. Each video segment should be followed by a self-assessment manikin (SAM) questionnaire where the participant rates their emotional experience. - Step 4: Data Synchronization. Ensure precise synchronization between the EEG data stream, the VR stimulus markers (e.g., start/end of each video), and the behavioral responses from the questionnaire. - Step 5: Data Preprocessing. Process the raw EEG data, which includes: - Filtering (e.g., 0.5-50 Hz bandpass, 50/60 Hz notch filter). - Bad channel removal and interpolation. - Ocular and muscular artifact correction using algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA). - Epoching the data into 1-second segments. - Step 6: Feature Extraction. For each epoch, apply the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) to compute frequency-domain features. Extract Differential Entropy (DE) features from the five standard frequency bands: δ (1-3Hz), θ (4-7Hz), α (8-13Hz), β (14-30Hz), and γ (31-50Hz) [7]. - Step 7: Model Training and Analysis. The DE features (shape: N samples × T time frames × C channels × F frequency bands) are used to train a spatial and temporal Transformer model (EmoSTT) to decode emotional states, comparing its performance against models trained on passive paradigm data.

Technical Implementation: Enabling Technologies

The shift to interactive manipulation is powered by advances in several key technological areas.

Haptic Sensing and Feedback

Haptic interaction is a cornerstone of active manipulation, comprising two main functions:

- Haptic Sensing: Artificial tactile sensors gather information from physical contact. Based on mechanisms like piezoresistive, capacitive, and piezoelectric effects, these sensors can detect force, pressure distribution, and even identify textures [8]. In VR, they are used for gesture recognition and touch identification, translating real-world actions into virtual commands.

- Haptic Feedback: This is the reverse process, where devices stimulate the skin to evoke tactile sensations. Techniques include:

- Mechanical Vibration: Actuators provide vibrotactile feedback, targeting Meissner corpuscles (FA-I, 10-50 Hz) for light contact and texture, and Pacinian corpuscles (FA-II, 200-300 Hz) for high-frequency vibrations [8].

- Dielectric Elastomer Actuators (DEAs): These soft actuators can produce controllable deformations to simulate touch.

- Electrotactile (ET) Display: Uses electrical currents to stimulate nerve endings directly, creating tactile feelings.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System | Records electrical brain activity with high temporal resolution, essential for capturing neural correlates of active tasks in VR [7]. |

| Video-Based See-Through HMD | Provides the immersive VR/AR environment; video pass-through allows for seamless blending of real and virtual elements (Cross-Reality) [9]. |

| Haptic Sensing Glove | Equipped with tactile sensor arrays to capture hand gestures, touch force, and manipulation kinematics for virtual object interaction [8]. |

| Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) Sensor | Measures electrodermal activity as a proxy for physiological arousal and stress, often used in conjunction with VR behavioral analysis [10]. |

| Eye-Tracking Module (Integrated in HMD) | Monitors gaze direction and pupillometry, providing insights into visual attention and cognitive load during interactive tasks [10]. |

| Spatial-Temporal Transformer Model (EmoSTT) | A deep learning architecture specifically designed to model both the temporal dynamics and spatial relationships of physiological signals like EEG for robust state classification [7]. |

Sensor Fusion and Lightweight Sensing Architectures

A key development is the move away from complex, multi-sensor setups to more streamlined architectures. The Sensor-Assisted Unity Architecture exemplifies this: it uses VR as the primary sensing platform for behavioral analysis (e.g., head movement, interaction logs) and supplements it with a minimal number of physiological sensors, such as a GSR sensor [10]. This approach reduces system complexity and cost while maintaining high data quality by focusing on the most informative signals.

Data Visualization and Transformation

Interactive manipulation also extends to data exploration. Research shows that transforming 2D data visualizations into 3D Augmented Reality (AR) space can enhance understanding. Parameters such as transformation methods (e.g., user-controlled vs. constant), node transformation order, and visual interconnection (e.g., using "ghost" visuals of the original 2D view) are critical for helping users build a coherent mental model of their data when shifting from a 2D display to an interactive 3D manipulation space [9].

Visualization of Core Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core logical and workflow relationships described in this whitepaper.

Active Sensing Research Paradigm

Diagram 1: Active sensing research paradigm workflow.

Sensor-Assisted VR Architecture

Diagram 2: Sensor-assisted VR architecture for data collection.

Virtual Reality (VR) has transcended its origins in entertainment to become a pivotal tool in scientific research, particularly in the field of active sensing, which is fundamental to pharmaceutical development. Active sensing describes the purposeful acquisition of sensory information to guide behavior. In the context of drug discovery, researchers act as active sensors, using their expertise to probe and understand the three-dimensional (3D) interaction between drug molecules and their biological targets. VR technologies directly augment this human-centered research process. This whitepaper details how three key technological enablers—haptic feedback, motion tracking, and real-time rendering—create immersive, interactive environments that empower scientists to conduct research intuitively and with unprecedented spatial understanding. By bridging the gap between abstract data and tangible experience, these technologies are revolutionizing the design and discovery of new therapeutic compounds.

Haptic Feedback: Conveying Molecular Interactions

Haptic feedback technology aims to replicate the sense of touch, providing critical tactile and force feedback that is essential for a researcher interacting with virtual molecular models. This transforms the drug design process from a visual exercise into a multi-sensory experience.

Technological Foundations and Recent Advances

Most commercial haptic technologies are limited to simple vibrations, which fall short of conveying the complex forces involved in molecular docking. The sense of touch in human skin involves different mechanoreceptors sensitive to pressure, vibration, and stretching. Reproducing this sophistication requires precise control over the type, magnitude, and timing of stimuli [11].

A significant recent advancement is the development of a compact, wireless haptic actuator with Full Freedom of Motion (FOM). This device can apply forces in any direction—pushing, twisting, and sliding—against the skin, rather than merely poking it. By combining these actuators into arrays, the technology can reproduce sensations as varied as pinching, stretching, and tapping [11]. These devices include an accelerometer to track orientation and movement, enabling context-aware haptic feedback. For instance, the friction of a virtual finger moving across different molecular surfaces can be simulated by altering the direction and speed of the actuator's movement [11].

Application in Pharmaceutical Active Sensing

In active sensing research, advanced haptics allows a scientist to "feel" the interaction between a drug candidate and a protein binding pocket. The repulsive forces from steric clashes, the attractive forces of hydrogen bonds, or the smooth sliding along a hydrophobic patch can be rendered as tangible sensations. This provides an intuitive understanding of molecular fit and stability that is difficult to glean from a 2D screen, dramatically enhancing the researcher's role as an active sensor in the virtual environment [11].

Table 1: Quantitative Data for Advanced Haptic Actuators

| Parameter | Specification / Capability | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Form Factor | Compact, millimeter-scale, wearable [11] | Can be placed anywhere on the body or integrated into gloves. |

| Actuation Type | Full Freedom of Motion (FOM) [11] | Simulates push, pull, twist, and slide forces for complex texture and force feedback. |

| Force Control | Precise control via magnetic field interaction with a tiny magnet [11] | Enables fine manipulation of virtual molecular objects. |

| Sensory Engagement | Engages multiple mechanoreceptors (pressure, vibration, stretch) [11] | Creates a nuanced and realistic sense of touch for molecular interactions. |

| Connectivity | Wireless, Bluetooth [11] | Allows for unencumbered movement in a VR space. |

Motion Tracking: Capturing and Translating Researcher Movement

Precise motion tracking is the cornerstone of immersion, ensuring that a researcher's physical movements are accurately mirrored by their virtual avatar or hands. This creates a direct, one-to-one correspondence between human action and virtual reaction, which is critical for precise manipulation of 3D molecular structures.

Tracking Modalities and Performance Metrics

Multiple technological approaches exist for motion tracking, each with distinct advantages:

- Inside-Out Tracking (HMD-Based): Used in headsets like Meta Quest and HTC Vive, this method relies on cameras and sensors on the headset itself to map the environment and track movement. It offers a good balance of ease of use, display quality, and affordability, making it accessible for research labs [12].

- Outside-In Tracking (External Sensor-Based): Systems like OptiTrack use external cameras placed around a room to track reflective or active LED markers. This provides superior, sub-millimeter accuracy and ultra-low latency, which is essential for applications requiring the highest precision. These systems are also "drift-free," meaning their calibration does not degrade over time, unlike some IMU-based systems [13].

- Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) Tracking: Systems like SlimeVR full-body trackers use onboard IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units) to track their own rotation without external cameras or base stations. While susceptible to yaw drift over time, this drift can be easily reset with a gesture or keypress [14].

- Camera-Based AI Tracking: Solutions like Driver4VR leverage the power of artificial intelligence and a standard smartphone or webcam to infer body pose through deep learning, providing an accessible entry point for full-body tracking [15] [16].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Motion Tracking Technologies

| Tracking Technology | Accuracy & Latency | Key Advantage | Best-Suited Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inside-Out (HMD) | Moderate accuracy, low latency [12] | Ease of setup and use; wireless freedom [12] | Collaborative molecular visualization; routine drug design ideation [17] |

| Outside-In (Optical) | Sub-millimeter accuracy, very low latency [13] | High precision for complex manipulations; drift-free [13] | Detailed molecular docking studies; high-fidelity simulation and training |

| IMU-Based (e.g., SlimeVR) | Rotation-only tracking; susceptible to drift [14] | No external hardware required; not susceptible to occlusion [14] | Supplementary tracking for body posture in large-scale virtual labs |

| Camera/AI (e.g., Driver4VR) | Lower accuracy, higher latency | Very low cost; utilizes existing hardware (phone/webcam) [15] | Prototyping and exploring full-body tracking applications |

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Docking with Interactive Manipulation

The following workflow, derived from published studies, outlines how precise motion tracking is utilized in a drug design experiment using Interactive Molecular Dynamics in VR (iMD-VR) [18].

Diagram 1: Motion tracking workflow for iMD-VR.

Methodology:

- System Setup: The researcher dons a VR headset (e.g., Meta Quest) with hand controllers, and the tracking system (either inside-out or outside-in) is calibrated [17] [18].

- Environment Loading: The target protein (e.g., influenza neuraminidase) and drug molecule are loaded into the iMD-VR software, which renders them as 3D objects in the virtual space [18].

- Docking Procedure: The researcher uses physically tracked hand movements to grab the virtual drug molecule, position it near the protein's binding site, and manipulate it in 3D space. The tracking system relays the precise position and rotation of the researcher's hands to the software in real time [18].

- Interaction and Analysis: The researcher can push, pull, and rotate the drug to find the optimal binding conformation. The software provides real-time computational feedback on binding energies and molecular forces [18]. This entire unbinding and rebinding process can be achieved interactively in under five minutes of real time [18].

Real-Time Rendering: Visualizing Complex Data in 3D

Real-time rendering is the computational process of generating photorealistic or scientifically accurate 3D imagery instantaneously as the user interacts with the environment. For active sensing in drug discovery, it transforms complex molecular data into visual forms that researchers can intuitively explore and understand.

Technology and Impact on Spatial Awareness

Modern VR systems leverage powerful graphics processing units (GPUs) to render high-fidelity virtual worlds with high-resolution textures, dynamic lighting, and high frame rates essential for user comfort and immersion [19]. Standalone headsets like the Meta Quest 3 have been crucial in making this technology accessible, offering sufficient processing power to visualize multiple protein structures simultaneously without a tethered PC [17].

The primary value for pharmaceutical research lies in enhancing spatial awareness. Traditional methods rely on 2D screens, physical models, or imagination to comprehend 3D molecular interactions. Real-time rendering places the scientist inside the structure, allowing them to walk around a protein, look into active sites, and perceive depth and spatial relationships directly. This has been shown to help chemists create "better" drugs by improving their understanding of the spatial arrangement between molecules and their targets [17]. Studies using software like Nanome on Meta Quest headsets have demonstrated that after a short orientation, design teams can independently build and manipulate immersive molecular models [17].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for VR-Enabled Drug Design

The following table details key hardware and software "reagents" required to establish a VR-based active sensing platform for pharmaceutical research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for VR-Enabled Drug Design

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Standalone VR Headset | Provides the immersive visual interface and onboard processing for untethered operation. | Meta Quest series used for collaborative molecular design with Nanome software [17]. |

| Interactive MD-VR Software | Enables real-time manipulation and simulation of molecules with physics-based feedback. | University of Bristol's iMD-VR for docking drugs into proteins like HIV protease [18]. |

| Collaborative VR Platform | Allows multiple researchers in different locations to share and manipulate the same virtual models. | Nanome software used by LifeArc to bring chemists from London and Lithuania together in a virtual lab [17]. |

| Haptic Feedback Actuators | Provides tactile sensation to simulate molecular forces like repulsion and bond formation. | Northwestern University's FOM actuators to simulate the feeling of touching different molecular surfaces [11]. |

| Precision Tracking System | Captures user movement with high accuracy for precise manipulation of virtual objects. | OptiTrack systems for sub-millimeter tracking in research requiring the highest precision [13]. |

Integrated Experimental Protocol: A Collaborative Drug Design Session

This protocol synthesizes the three enabling technologies into a single, cohesive workflow for a collaborative drug design session, based on the documented practices of organizations like LifeArc [17].

Diagram 2: Collaborative drug design workflow.

Methodology:

- Session Initiation: Multiple researchers from different geographical locations don their VR headsets and join a shared virtual room using a platform like Nanome. Their movements are tracked, and their avatars are represented in the space [17].

- Data Integration and Rendering: The target protein structure and relevant molecular data (e.g., from assays or computational models) are loaded and rendered in 3D in the center of the virtual space. Real-time rendering ensures all participants see the model from their own perspective [17].

- Collaborative Ideation and Manipulation: One researcher ("Driver") takes control of a drug molecule. Using precise motion tracking, they grab and position the molecule into the protein's binding site. Other participants can observe from the same viewpoint and provide real-time verbal feedback or use virtual annotations to suggest modifications [17].

- Multi-Sensory Feedback Loop: As the drug is manipulated, real-time simulation calculations run in the background. The rendering engine visually updates the model, while haptic actuators (if available) provide force feedback based on molecular interactions. This creates a tight loop where the researcher's active sensing is guided by immediate visual and tactile cues [18].

- Output and Iteration: Promising molecular designs are saved directly from the virtual session. The team can rapidly iterate on designs, with changes incorporated and visualized in real-time, significantly accelerating the ideation process compared to traditional methods [17]. This integrated approach has been reported to yield a 10-fold gain in efficiency for method transfer and design tasks [20].

Haptic feedback, motion tracking, and real-time rendering are not isolated technologies; they are deeply interconnected enablers of a new paradigm for active sensing in pharmaceutical research. Together, they create a synthetic environment where the intricate, 3D nature of molecular interactions can be perceived, manipulated, and understood with human intuition and skill. By effectively placing the scientist inside the data, these technologies enhance spatial awareness, enable true collaborative exploration, and dramatically accelerate the iterative process of drug design. As these technologies continue to advance—becoming more affordable, higher-fidelity, and more deeply integrated with computational simulation—their role in unlocking new therapeutic discoveries will only grow more critical.

The ability to comprehend complex, multi-dimensional data is paramount in fields such as drug development and active sensing research. Traditional visualization methods often fall short in conveying the intricate spatial relationships inherent in such datasets. Immersive technologies, particularly Virtual Reality (VR) and Mixed Reality (MR), are emerging as transformative tools that leverage the human brain's innate capacities for spatial reasoning to overcome these limitations. Framed within the broader context of active sensing—where an agent selectively gathers sensory information to guide its actions in an environment—immersive visualization creates a closed-loop system. In this system, researchers can actively explore data, and their movements and decisions within the virtual space in turn shape the information they perceive [21]. This article details the theoretical foundations, supported by empirical evidence and experimental protocols, that explain how immersion fundamentally enhances the spatial understanding of complex data.

Theoretical Foundations of Immersive Spatial Understanding

The efficacy of immersive visualization is rooted in several interconnected cognitive and technological principles.

Multimodal Perception and Interaction

Immersive visualization utilizes VR, MR, and interactive devices to create a novel visual environment that integrates multimodal perception and interaction [21]. Unlike traditional screens, immersive environments engage multiple sensory channels—visual, auditory, and sometimes haptic—in a coordinated manner. This multisensory input is crucial for building robust mental models of complex data, as it mirrors the way humans naturally perceive and interact with the physical world. The integration of perception and action allows researchers to actively sense their data environment, testing hypotheses through physical navigation and manipulation rather than passive observation [21].

Ecological Validity and Embodied Cognition

A core strength of immersive environments is their high ecological validity; they can present complex data within a context that closely mimics real-world scenarios or effectively represents abstract data spaces [22]. This is closely tied to the theory of embodied cognition, which posits that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body's interactions with the world. In an immersive setting, a researcher's physical movements—such as walking around a molecular structure or using hand gestures to manipulate a dataset—facilitate deeper cognitive engagement and understanding. This embodied experience is a direct analogue to active sensing, where perception is guided by action [23].

Enhanced Spatial Memory Encoding

Spatial memory, the cognitive ability to retain and recall the configuration of one's surroundings, is fundamental to navigation and environmental awareness [23]. Research indicates that immersive technologies are particularly effective at engaging the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, brain regions critical for spatial memory and among the first affected in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's [23]. By presenting data in a full 3D, navigable space, immersion promotes the same neural mechanisms used for real-world navigation, leading to more durable and accessible memory traces of the data's spatial layout [23].

Empirical Evidence and Quantitative Data

The theoretical principles are supported by a growing body of empirical evidence. The table below summarizes key findings from recent research on the application of immersive technologies to spatial tasks.

Table 1: Empirical Evidence for Immersion in Spatial Understanding

| Study Focus | Technology Used | Key Spatial Metric | Reported Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Memory Assessment | Immersive VR (HMD) | Path Integration, Object-Location Memory | Higher diagnostic sensitivity for Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) than traditional paper-and-pencil tests. | [23] |

| User Comfort & Behaviour | Immersive Virtual Office | Sense of Presence, Realism | Excellent self-reported sense of presence and realism, supporting ecological validity. | [22] |

| Framework for Behavioural Research | VR Frameworks (EVE, Landmarks, etc.) | Data Reproducibility & Experiment Control | DEAR principle (Design, Experiment, Analyse, Reproduce) improves standardization. | [24] |

| Museum Immersive Experience | VR in Cultural Institutions | Perceived Usefulness, Ease of Use | Core technical indicators (from Technology Acceptance Model) are primary drivers of user engagement. | [25] |

Furthermore, studies have successfully captured the impact of environmental variables on human performance within immersive settings, demonstrating the criterion validity of VR. For instance, an experiment with 52 subjects in a virtual office showed that the system could properly capture the statistically significant influence of different temperature setpoints on thermal comfort votes and adaptive behavior [22].

Experimental Protocols for Immersive Data Visualization

To ensure the validity and reliability of research conducted in immersive environments, a structured experimental framework is essential. The following protocol, synthesizing best practices from the literature, can be adapted for studies on spatial data understanding.

Pre-Experimental Phase: Design and Preparation

- Hypothesis and Variable Definition: Clearly define the research question. The independent variable could be the level of immersion (e.g., desktop 3D vs. fully immersive VR). Dependent variables should measure spatial understanding, such as:

- Content and Ecological Validity: Develop the virtual environment and data representation. For active sensing research, this could be a 3D point cloud from LIDAR scans or a complex molecular structure. Expert review should be used to establish content validity, ensuring the environment accurately represents the target domain [22].

- Pilot Testing: Conduct small-scale trials to calibrate the experiment, identify technical issues, and ensure that tasks are neither too easy nor too difficult.

Experimental Execution: Data Collection

- Participant Briefing and Training: Inform participants about the procedure and obtain consent. Provide a standardized training session within the VR environment to familiarize them with the controls and interface, minimizing the impact of the learning curve on task performance [24].

- Experimental Task: Guide participants through the core task. An example workflow for a drug development context is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for an Immersive Drug Discovery Study

- Data Recording: Automatically and systematically log all relevant data. This includes the dependent variables, but also process metrics like head and hand tracking data, gaze paths, and interaction logs, which can provide rich insights into the user's cognitive and active sensing strategies [24].

Post-Experiment: Analysis and Reproducibility

- Data Analysis: Apply statistical tests to evaluate the hypothesis. For complex data, machine learning techniques can be used to analyze behavioral patterns [23].

- Ensuring Reproducibility: Adhere to the DEAR (Design, Experiment, Analyse, Reproduce) principle. This involves documenting all aspects of the experiment, from the framework and software version to the specific parameters of the virtual environment, and making the experimental setup scriptable to allow for exact replication [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Conducting rigorous immersive visualization research requires both hardware and software components. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Immersive Visualization

| Item Name | Category | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Hardware | Provides the visual and auditory immersive experience. Application: The primary device for presenting the virtual data environment to the user. Examples include Oculus, VIVE. [24] |

| Motion Tracking System | Hardware | Tracks the user's head, hand, and potentially full-body position in real-time. Application: Enables embodied interaction and active sensing, allowing researchers to physically navigate and manipulate data. [21] |

| VR Experiment Framework (e.g., EVE, UXF) | Software | Provides pre-determined features and templates for creating, running, and managing experiments in VR. Application: Standardizes experimental procedures, manages participants, and facilitates data collection, enhancing internal validity and reproducibility. [24] |

| Game Engine (e.g., Unity, Unreal) | Software | The development platform used to create the 3D virtual environment and data visualizations. Application: Allows for the rendering of complex data structures and the programming of interactive elements and logic. [24] |

| Data Logging Module | Software | A customized or framework-integrated tool for recording participant data. Application: Systematically captures all dependent variables (accuracy, time) and process metrics (trajectories, gaze) for subsequent analysis. [22] [24] |

The theoretical basis for how immersion enhances spatial understanding of complex data is built upon a powerful convergence of cognitive science and technology. By leveraging multimodal perception, embodied cognition, and ecological validity, immersive environments transform abstract data into spatial experiences that the human brain is exquisitely adapted to understand. This creates a direct pipeline to the neural substrates of spatial memory, making it a potent tool for tasks ranging from analyzing molecular interactions in drug development to interpreting 3D sensor data in active sensing research. While challenges such as cybersickness and standardization remain, the rigorous application of structured experimental protocols and frameworks ensures that this promising field will continue to yield valid, reproducible, and profound insights into complex data.

VR in Action: Methodologies for Drug Target Visualization and Simulation

Molecular Docking and Drug-Target Interaction Analysis in VR

Active sensing research, particularly in the context of drug discovery, involves the proactive exploration of biological systems to understand how potential therapeutics interact with their targets. Virtual Reality (VR) is transforming this field by providing an immersive, three-dimensional spatial context for visualizing and manipulating complex molecular and biological data. This paradigm shift moves researchers from passive observation to active, intuitive exploration within a computational space, dramatically accelerating the process of hypothesis generation and testing [26]. The core of this approach lies in using VR to simulate a hypothetical reality where researchers can confront scenarios driven by interactions between their scientific intuition and the digital environment, much like pilots training in flight simulators [26]. This guide details the technical integration of molecular docking, drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, and VR, framing them as essential components of an advanced active sensing framework for modern pharmaceutical research.

Recent Advances in Computational Prediction Methods

Molecular Docking Techniques

Molecular docking is a fundamental structure-based method that predicts the orientation and conformation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor). Recent advances have significantly enhanced their accuracy and efficiency in predicting drug-target interactions [27].

Key Advancements include:

- Fragment-Based Docking: This technique breaks down complex molecules into smaller fragments for docking, improving the sampling of binding sites and the identification of key interactions.

- Covalent Docking: These methods predict interactions between drugs and protein residues that form covalent bonds, opening new opportunities for targeting challenging drug-resistant mutations [27].

- Handling Protein Flexibility: Improved sampling techniques and sophisticated algorithms have increased the efficiency and precision of simulations, allowing researchers to investigate conformational changes and protein flexibility during the drug-binding process [27].

- Virtual Screening: This approach leverages docking to rapidly evaluate massive libraries of compounds against a target, streamlining the initial hit-finding phase [27].

Popular algorithms such as Vina, Glide, and AutoDock continue to be refined, offering enhanced performance. However, it is crucial to remember that molecular docking alone is insufficient to ensure the safety and efficacy of a drug candidate. While it excels at predicting binding affinity and interaction, it does not account for pharmacokinetics, toxicity, off-target effects, or in vivo behavior. Experimental validation through molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, ADMET profiling, and in vitro/in vivo studies remains essential [27].

Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction

While docking relies on 3D structures, broader DTI prediction methods use various data types to identify potential interactions. Accurate DTI prediction is an essential step in drug discovery, and in silico approaches mitigate the high costs, low success rates, and extensive timelines of traditional development [28].

Table 1: Categories of In Silico DTI Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Description | Key Strengths | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based [29] | Uses 3D structures of target proteins (e.g., from X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, or AlphaFold) to predict interactions. | Provides atomic-level insight into binding modes; facilitates lead optimization. | Computational resource-intensive; requires a known or reliably predicted 3D structure. |

| Ligand-Based [29] | Compares a candidate ligand to known active ligands for a target (e.g., using QSAR). | Effective when target structure is unknown but active ligands are available. | Predictive power limited by the number and diversity of known ligands. |

| Network-Based [29] | Constructs heterogeneous networks from diverse data (chemical, genomic, pharmacological) and uses topological information. | Does not require structural data; can integrate multiple data types for novel predictions. | Can be a "black box"; performance depends on network quality and completeness. |

| Machine Learning-Based [29] | Uses ML models to learn latent features from drug and target data (e.g., SMILES strings, protein sequences). | Can handle large-scale data; strong predictive performance with sufficient labeled data. | Often relies on large, high-quality labeled datasets; can suffer from "cold start" problems with new entities. |

Recent state-of-the-art frameworks, such as DTIAM, unify the prediction of DTI, drug-target binding affinity (DTA), and the critical mechanism of action (MoA)—distinguishing between activation and inhibition [29]. DTIAM and similar advanced models leverage self-supervised learning from large amounts of unlabeled data (molecular graphs and protein sequences) to learn meaningful representations, which dramatically improves generalization performance, especially in "cold start" scenarios involving novel drugs or targets [29].

Integrating VR into the Drug Discovery Workflow

Virtual Reality acts as a powerful unifying layer, bringing the computational methods described above into an interactive, intuitive, and collaborative environment. The VRID (Virtual Reality Inspired Drugs) concept formalizes this approach, positioning VR as a vein for novel drug discoveries [26].

Table 2: VR Applications in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

| Discovery Stage | Role of Virtual Reality | Quantitative Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Serves as a hypothesis generator by providing a system-level theoretical framework to explore dynamics and test "what-if" scenarios [26]. | Allows theoretical testing of hundreds of treatment combinations and doses in silico [26]. |

| Lead Generation & Screening | Provides a 3D spatial platform to screen and visualize lead compounds, tuning parameters like potency and selectivity interactively [26]. | Shortens lead generation and screening phases by predicting therapeutic efficacy and biological activity before wet-lab experiments. |

| Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) | Models drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) in a dynamic 3D space for different delivery systems [26]. | Serves as an additional layer to mathematical PK/PD models, guiding treatment strategy and dosage predictions. |

| Precision Medicine | Builds patient-specific simulations from individual data (e.g., MRI) to tailor optimal treatment protocols [26]. | Moves beyond "one-size-fits-all"; e.g., eBrain modeling indicated combinatorial approaches could reduce single drug doses, lowering side-effect likelihood [26]. |

A proof-of-concept for VRID is eBrain, a VR platform that models drug administration to the brain. For instance, eBrain can upload a patient's MRI, simulate the infusion of a drug (e.g., intranasal insulin for Alzheimer's), and visualize its diffusion through brain tissue and subsequent activation of neurons [26]. This allows for the in silico testing of hundreds of doses and combination treatments to identify the most efficacious and cost-effective approach for a specific patient profile [26].

Experimental Protocols for VR-Enhanced Analysis

Protocol 1: VR-Enabled Molecular Docking and Analysis

This protocol integrates traditional docking workflows with an immersive VR layer for enhanced visualization and interaction.

1. System Setup and Preparation: * Hardware: Utilize a standalone VR headset (e.g., Meta Quest 3) or a PC-connected system. For full sensory immersion, consider haptic feedback gloves or suits to "feel" molecular forces and surfaces [19]. * Software: Employ a molecular visualization package with VR capability (e.g., molecular viewers extended for VR) coupled with standard docking software (Vina, Glide, AutoDock). * Data Preparation: Prepare the protein target by removing water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and defining the binding site grid, as per standard docking procedure.

2. Immersive Docking and Visualization: * Import the prepared protein structure and pre-docked ligand poses into the VR environment. * Don the VR headset to enter the molecular-scale space. Physically walk around the protein target to inspect the binding pocket from all angles. * Manually manipulate and re-dock ligands using hand controllers, leveraging intuitive human spatial reasoning to explore binding modes that might be missed by automated algorithms alone. * Use the VR interface to toggle visualization of key interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and pi-stacking, overlaid directly within the 3D space.

3. Analysis and Hypothesis Generation: * Compare multiple docked poses side-by-side in the virtual space to assess their stability and interaction networks critically. * Annotate observations directly in the VR environment using virtual markers or voice notes. * Collaboratively analyze the scene with remote colleagues in a multi-user VR session, discussing the viability of different binding hypotheses in real-time [19].

Protocol 2: Validating DTI Predictions Using a VR Simulation Platform

This protocol uses a VR simulation platform like eBrain to validate and contextualize DTI predictions from a model like DTIAM.

1. Data Input and Model Integration: * Input: Feed the results from a DTIAM prediction—including the predicted interaction, binding affinity, and MoA (activation/inhibition)—into the VR platform. * Contextualization: The VR platform (e.g., eBrain) maps this drug-target interaction onto a broader physiological context. For a neurological target, this means simulating the relevant brain region based on a standard or patient-specific MRI atlas [26].

2. System-Level Simulation: * The platform simulates the pharmacokinetics of the drug, modeling its route of administration (e.g., intranasal, intravenous), diffusion through tissues, and uptake by cells [26]. * It then visualizes the pharmacodynamic effect—the activation or inhibition of the target pathway—within the virtual tissue environment. For example, the propagation of a neural signal in the substantia nigra could be simulated and visually represented [26].

3. Outcome Analysis and Iteration: * Observe the system-level outcome of the drug's action, such as changes in network activity or biomarker levels. * Analyze the simulation to predict efficacy and potential side-effects based on the drug's distribution and MoA in the full physiological context. * Iteratively adjust drug parameters (e.g., dose, formulation) in the VR model and re-run the simulation to theoretically optimize the treatment protocol before moving to experimental validation [26].

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core logical workflows and relationships described in this guide.

VR Enhanced Drug Discovery Workflow

DTIAM Model Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for VR-Enhanced Drug Discovery

| Item | Function & Role in Research |

|---|---|

| VR Simulation Platform (e.g., eBrain) | Models drug administration, diffusion, uptake, and effect within a physiological system (e.g., the brain), allowing for system-level testing of treatments in silico [26]. |

| Standalone VR Headset (e.g., Meta Quest 3) | Provides an accessible, high-performance, wireless portal into the virtual molecular environment, enabling widespread adoption in labs [19]. |

| Multi-sensory Haptic Technology | Haptic gloves and suits provide tactile feedback, allowing researchers to "feel" molecular surfaces, forces, and textures, which is critical for assessing interactions in fields like gaming and training [19]. |

| Self-Supervised Learning Model (e.g., DTIAM) | A unified computational framework that learns from unlabeled data to predict drug-target interactions, binding affinity, and mechanism of action, particularly powerful for cold-start problems [29]. |

| Advanced Docking Software (Vina, Glide, AutoDock) | The computational engine for predicting the atomic-level binding pose and orientation of a small molecule within a target protein's binding site [27]. |

| Scientific Illustration Tool (e.g., BioRender) | Creates clear, standardized visual protocols and pathway diagrams to document findings, communicate complex concepts, and ensure consistency across research teams [30] [31]. |

Building Patient-Specific 3D Disease Models for Personalized Medicine

The paradigm of drug development and therapeutic intervention is shifting from a one-size-fits-all approach to a more tailored strategy, enabled by the creation of patient-specific three-dimensional (3D) disease models. These advanced ex vivo systems aim to recapitulate the complex architecture and cellular crosstalk of human tissues, providing a powerful platform for personalized drug screening and disease mechanism investigation [32]. The convergence of tissue engineering, 3D bioprinting, and patient-derived cellular materials has facilitated the development of biomimetic environments that more accurately predict individual patient responses to therapies. Furthermore, the integration of these physical models with immersive virtual reality (VR) technologies is opening new frontiers for researchers to visualize, manipulate, and understand disease biology within spatially complex microenvironments, thereby enhancing the utility of these models in active sensing research [33]. This technical guide examines the current state of patient-specific 3D disease models, with a focus on their construction, validation, and integration with VR for advanced analysis in personalized medicine.

Technical Foundations of 3D Disease Models

Core Bioprinting Technologies

The fabrication of patient-specific 3D models relies heavily on additive manufacturing approaches that enable precise spatial patterning of cellular and acellular components [34].

- Inkjet Bioprinting: This non-contact technology utilizes thermal or piezoelectric mechanisms to deposit bioink droplets. It is characterized by its high speed and capability for multi-material printing, enabling the generation of heterogeneous tissues. A key limitation is the potential for nozzle clogging and reduced cell viability due to shear stress, restricting bioink cell density to below 5 × 10^6 cells/mL [32].

- Extrusion Bioprinting: This method employs pneumatic or mechanical dispensing systems to continuously deposit bioink filaments. It is one of the most prevalent techniques in tissue engineering due to its ability to handle a wide range of biomaterial viscosities and achieve high cell densities. Challenges include limited printing resolution (typically in the hundreds of microns) and potential nozzle obstruction [32].

- Laser-Assisted Bioprinting: This technology uses laser energy to transfer bioink from a donor layer to a substrate. It offers high resolution and is gentle on cells, but its complexity and cost have limited its widespread adoption compared to other modalities [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Major 3D Bioprinting Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inkjet Bioprinting | Thermal/Piezoelectric droplet deposition | Single cell scale | High speed, multi-material capability, non-contact | Low cell density, potential heat/shear stress |

| Extrusion Bioprinting | Continuous filament deposition | ~100 μm | High cell density, wide biomaterial compatibility | Lower resolution, nozzle clogging risk |

| Laser-Assisted Bioprinting | Laser-induced forward transfer | High (cell scale) | High resolution, high cell viability | High cost, complex setup, lower throughput |

Essential Biomaterials and Microenvironment

The biomaterials used in 3D disease models, often hydrogel-based, are critical as they must biomimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM) to support physiological cell behavior [34].

Key Hydrogel Properties:

- Biocompatibility: The material must support cell viability, proliferation, and function without inducing cytotoxicity [34].

- Biomimicry: The hydrogel should replicate the biochemical and biophysical properties of the target tissue's native ECM, including presentation of adhesion ligands and appropriate mechanical stiffness [34] [35].

- Tunable Mechanical Properties: The stiffness, viscosity, and elasticity of the hydrogel can be modulated to match the pathological tissue of interest [34].

- Degradability: The scaffold should degrade at a rate commensurate with new tissue formation, allowing for remodeling [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents for 3D Disease Modeling

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for constructing patient-specific 3D disease models.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Cells (e.g., cancer cells, hiPSCs) | Provides the patient-specific genetic and phenotypic foundation for the model. | Source (primary vs. immortalized), culture stability, need for stromal components [32] [35]. |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Provides a tissue-specific biochemical scaffold that preserves native ECM composition and signaling cues. | Source tissue, decellularization efficiency, batch-to-batch variability [34]. |

| Synthetic Hydrogels (e.g., PEG, Pluronics) | Provides a defined, tunable scaffold with controllable mechanical and biochemical properties. | Functionalization for cell adhesion, degradation kinetics, biocompatibility [34]. |

| Natural Hydrogels (e.g., Collagen, Matrigel, Alginate, GelMA) | Offers innate bioactivity and cell adhesion motifs; widely used for high-fidelity cell culture. | Lot-to-lot variability (especially Matrigel), immuneogenicity, mechanical weakness [34]. |

| Crosslinking Agents | Induces gelation of hydrogel precursors to form stable 3D structures (e.g., ionic, UV, enzymatic). | Cytotoxicity, crosslinking speed, homogeneity of the resulting gel [32]. |

| Soluble Factors (e.g., Growth Factors, Cytokines) | Directs cell differentiation, maintains phenotype, and recreates key signaling pathways of the TME. | Stability in culture, concentration gradients, cost [35]. |

Application-Specific Model Design

Modeling the Tumor Microenvironment

3D bioprinted cancer models are at the forefront of personalized oncology, designed to capture the intricate interplay between malignant cells and the tumor microenvironment (TME) [32]. Key design considerations include:

- Incorporating Stromal Components: Faithful models integrate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, and immune cells to replicate the pro-tumorigenic signaling and drug resistance mechanisms conferred by the TME [34] [35].

- Recreating Gradients: The TME is characterized by gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and cytokines. Bioprinting allows for the spatial patterning of these factors to mimic the core vs. periphery conditions of a tumor, which is crucial for studying drug penetration and efficacy [32] [35].

- Vascularization: A major challenge is incorporating functional vasculature. Strategies include co-printing endothelial cells with supportive pericytes and using sacrificial bioinks to create perfusable channels, which are essential for modeling metastatic spread and delivering therapeutics [32].

Diagram 1: Workflow for building a 3D bioprinted patient-specific tumor model.

Recapitulating the Bone Marrow Niche in Hematologic Malignancies

For diseases like multiple myeloma (MM), the bone marrow (BM) niche is a master regulator of disease progression and drug resistance. Patient-derived 3D MM models seek to recreate this complex ensemble [35].

- Cellular Complexity: A faithful MM model must include, besides the malignant plasma cells, BM stromal cells (BMSCs), adipocytes, endothelial cells, osteoclasts, and immune cells. The crosstalk between these cells, mediated by adhesion molecules and soluble factors, is a critical therapeutic target [35].

- Biomaterial Strategy: Hydrogels for MM models must support the growth of both adherent (stromal) and non-adherent (myeloma) cell populations. Fibrin and hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels have shown promise in maintaining these co-cultures and preserving patient-specific drug response profiles [35].

Integration with Virtual Reality for Analysis and Visualization

The complex, multi-parametric data generated by 3D disease models can be more intuitively understood and analyzed through immersive VR technologies. This integration is pivotal for active sensing research, where scientists can actively probe and interact with the model in a simulated space.

- Surgical Planning and Visualization: VR platforms, such as Medical Imaging XR (MIXR), allow clinicians and researchers to visualize medical imaging data (CT, MRI) in augmented reality on common devices like smartphones. Workflows like "VR-prep" optimize DICOM files for rapid AR visualization, significantly improving the confidence of clinicians in using these models for diagnostics and preoperative planning [36].

- Enhanced Collaborative Analysis: Metaverse platforms enable multidisciplinary teams to collaborate in shared virtual spaces to review 3D anatomical models and plan treatments. This facilitates a more holistic understanding of patient-specific disease geometry and the spatial relationship between tissues [33].

- Interactive Medical Education and Training: VR is revolutionizing medical education by providing immersive, interactive learning experiences. For instance, VR anatomy training has been shown to increase knowledge retention by up to 63% and user engagement by up to 72%, enabling students and researchers to deeply understand the structural context of the diseases they are modeling [19] [37].

Diagram 2: VR integration for analyzing 3D model data.

Detailed Experimental Workflow: A Case Study

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a patient-specific, bioprinted breast cancer model for personalized drug screening, as adapted from recent literature [34] [32].

Protocol: Bioprinting a Vascularized Breast Tumor Model

Objective: To fabricate a 3D breast cancer model containing patient-derived cancer cells and an endothelial network for assessing drug response.

Materials:

- Cells: Patient-derived breast cancer cells (BCCs), Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) isolated from the same tumor [34].

- Bioinks:

- Tumor Bioink: Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) supplemented with patient-derived dECM, loaded with BCCs and CAFs.

- Vascular Bioink: Glycidyl methacrylate-hyaluronic acid (GMHA) loaded with HUVECs.

- Bioprinter: Extrusion-based bioprinter equipped with a multi-cartridge printhead and a UV crosslinking module.

Method:

- Pre-bioprinting:

- Cell Expansion: Expand patient-derived BCCs, CAFs, and HUVECs in 2D culture using appropriate media.

- Bioink Preparation: Mix GelMA with digested tumor dECM at a ratio of 4:1. Resuspend the pellet of BCCs and CAFs (at a 5:1 ratio) in the GelMA/dECM blend to a final density of 10 × 10^6 cells/mL. Keep on ice.

- Prepare the vascular bioink by dissolving GMHA and loading HUVECs at a density of 15 × 10^6 cells/mL.

Bioprinting Process:

- Load the tumor and vascular bioinks into separate sterile cartridges mounted on the bioprinter.

- Set the printing parameters: Nozzle diameter: 250 μm (tumor), 150 μm (vascular); Pressure: 18-22 kPa (tumor), 12-15 kPa (vascular); Print speed: 8 mm/s; Print bed temperature: 15°C.

- Using a computer-aided design (CAD) model, co-print the tumor and vascular bioinks in a concentric pattern. The tumor bioink forms the core, while the vascular bioink is printed as an surrounding network.

- Apply UV light (365 nm, 5 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds after each layer is deposited to achieve partial crosslinking.

Post-bioprinting:

- After the construct is complete, immerse it in cell culture medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Culture the model for up to 21 days, with medium changes every 2-3 days. The endothelial network will typically form lumen-like structures within 7-14 days.

Drug Screening Application:

- On day 7 post-bioprinting, treat the model with a panel of anti-cancer drugs (e.g., chemotherapeutics, targeted therapies) at clinically relevant concentrations.

- After 72-96 hours of exposure, assess viability using assays like AlamarBlue or Calcein-AM/Ethidium homodimer-1 live/dead staining. Confocal microscopy and immunohistochemistry can be used to evaluate morphological changes, endothelial integrity, and specific protein markers.

Patient-specific 3D disease models represent a transformative technology in personalized medicine, moving beyond the limitations of traditional 2D cultures and animal models. The synergy between advanced biomanufacturing techniques like 3D bioprinting and cutting-edge visualization tools like virtual reality creates a powerful feedback loop. This integration allows researchers not only to build more physiologically relevant models of human disease but also to actively sense, probe, and interpret the complex biological phenomena within them in an intuitive and collaborative manner. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, they hold the promise of accelerating the development of truly personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately improving patient outcomes across a spectrum of diseases.

Simulating Drug Penetration and Cellular Response in Virtual Tissues

The integration of virtual reality (VR) and computational modeling is revolutionizing active sensing research in drug development. By simulating drug penetration and cellular responses in virtual tissues, researchers can visualize and analyze biological processes in immersive, dynamic environments. This approach leverages in silico models—such as virtual patients, AI-driven virtual cells, and digital twins—to predict drug efficacy, optimize dosing, and reduce reliance on traditional laboratory experiments [38] [39] [40]. Framed within a broader thesis on VR's role in active sensing, this whitepaper explores methodologies, tools, and experimental protocols for simulating tissue-level drug behavior.

Computational Frameworks for Virtual Tissue Simulation