Affordances and Cognitive Capital: A Behavioral Neuroscience Framework for Brain Health and Drug Development

This article synthesizes the behavioral neuroscience of affordances—environmental opportunities for action—with the concept of cognitive capital, the neural and cognitive resources that support adaptive behavior.

Affordances and Cognitive Capital: A Behavioral Neuroscience Framework for Brain Health and Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes the behavioral neuroscience of affordances—environmental opportunities for action—with the concept of cognitive capital, the neural and cognitive resources that support adaptive behavior. It explores the neurocognitive mechanisms of affordance processing, from direct perception to visuomotor transformation, and their critical role in health and neurological disease. We provide a framework for translating basic research on dispositional and neural accounts of affordances into novel methodologies for assessing cognitive capital, troubleshooting neuropsychiatric deficits, and validating biomarkers. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review outlines how an affordance-based approach can optimize therapeutic strategies, refine clinical trial endpoints, and ultimately promote cognitive resilience.

Deconstructing Affordances: From Gibson's Ecology to Modern Neural Circuitry

James J. Gibson's affordance theory, formally introduced in his 1979 work The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, represents a paradigm shift in understanding how organisms perceive their environments [1]. Gibson proposed that perception is not a passive process of constructing internal representations of the world, but rather a direct pickup of information that specifies action possibilities [2]. This revolutionary perspective contends that we perceive the environment not in terms of abstract geometric properties, but in terms of what it affords for action—what it offers, provides, or furnishes, for good or ill [1] [2]. The concept of affordances has since become foundational across multiple disciplines, including ecological psychology, behavioral neuroscience, human-computer interaction, and architectural design [1] [2].

Within behavioral neuroscience research, the study of affordances provides a crucial framework for understanding the perception-action cycle and its neural underpinnings [3] [4]. This technical guide examines Gibson's foundational theory through a neuroscientific lens, exploring how the brain bridges the gap between perceiving environmental opportunities and executing appropriate motor responses, with implications for understanding cognitive capital—the neural resources that enable adaptive behavior.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Principles

Core Definition and Relational Nature

Gibson defined affordances as the action possibilities offered by the environment relative to an organism's capabilities [1] [5]. Crucially, affordances are relational properties that emerge from the interaction between an organism's abilities and environmental features [1]. They are neither solely properties of the environment nor solely properties of the perceiver, but rather exist in the dynamic relationship between them [1]. For example, a staircase affords climbing for an adult human but not for an infant; a rock affords throwing for a human but not for a squirrel of proportional size [1].

This relational character means affordances are objective in that they exist independently of being perceived, yet they are species-specific and individual-specific [1]. As Gibson stated, "An affordance is neither an objective property nor a subjective property; or it is both if you like. An affordance cuts across the dichotomy of subjective-objective and helps us to understand its inadequacy. It is equally a fact of the environment and a fact of behavior. It is both physical and psychical, yet neither. An affordance points both ways, to the environment and to the observer" [1].

Direct Perception versus Representational Models

Gibson's concept of direct perception stands in stark contrast to traditional representational models of perception [2]. Where representational models propose that perception involves processing sensory inputs to construct internal representations of the world, Gibson argued that perception is direct and unmediated by such representations [2]. According to his ecological approach, meaningful information about affordances is directly available in the ambient optic array and can be picked up without cognitive mediation [5] [2].

The environment is structured, and these structures are meaningful to the animal [2]. For instance, surfaces, layouts, objects, and events directly provide information about possibilities for action—shelters afford hiding, tools afford manipulation, paths afford walking, and obstacles afford avoidance [2]. This direct perception of affordances enables rapid, fluid interaction with the environment without the need for complex inferential processes [1].

Table 1: Key Properties of Affordances According to Gibson's Original Formulation

| Property | Description | Theoretical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Relational | Emerges from animal-environment fit; neither subjective nor objective | Challenges subjective-objective dichotomy [1] |

| Directly Perceived | Picked up without cognitive mediation or representation | Opposes constructivist models of perception [2] |

| Action-Oriented | Specifies possibilities for behavior | Links perception directly to action [3] |

| Species-Specific | Dependent on an organism's anatomical and action capabilities | Explains behavioral variation across species [1] |

| Multidimensional | Objects and surfaces afford multiple actions simultaneously | Accounts for behavioral flexibility [5] |

Neuroscientific Evidence and Mechanisms

Neurocognitive Foundations of Affordance Perception

Research in cognitive neuroscience has demonstrated that perceiving affordances activates specific brain regions involved in motor planning and execution [3]. Neuroimaging studies reveal that simply viewing graspable objects automatically activates the visuomotor system, including premotor and parietal areas that would be involved in actually performing the action [3]. In seminal experiments, Tucker and Ellis (1998, 2001) demonstrated that merely seeing an object biases behavior toward actions that match the object's features—for instance, precision grips for small objects and power grips for large objects [3]. This suggests that motor resonance occurs automatically upon viewing affordant objects.

These findings indicate that the brain maintains a tight coupling between perception and action systems, supporting Gibson's claim that we directly perceive what the environment affords rather than constructing abstract representations [3]. The canonical neuron system—which includes ventral premotor cortex and inferior parietal regions—is thought to play a key role in encoding object-directed actions and may constitute part of the neural substrate for affordance perception [4].

Current Debates in Affordance Neuroscience

Despite substantial progress, several key questions about the neural mechanisms of affordances remain actively debated:

Attention and Affordances: It is unclear whether affordance perception depends on attention or, conversely, whether affordances automatically guide attention to goal-relevant objects [3]. Humphreys and colleagues have shown that the action relevance of objects can influence attentional selection, suggesting a bidirectional relationship [3].

Dynamic versus Memory-Based Perception: Researchers debate whether affordances are perceived dynamically relative to current context and capabilities or retrieved based on memory of prior object interactions [3]. Evidence exists for both flexible, context-dependent affordance perception and more rigid object-action associations [3].

Spatial Coding: The relationship between affordance processing and spatial representation remains unclear, particularly how peripersonal space structures our interactions with objects and other people [3]. Farnè and Làdavas demonstrated that tool use can dynamically reshape peripersonal space representations, suggesting flexible spatial mapping of affordances [3].

Table 2: Key Experimental Paradigms in Affordance Neuroscience

| Experimental Paradigm | Key Findings | Neural Correlates |

|---|---|---|

| Grasp Compatibility | Objects automatically evoke compatible grip responses [3] | Premotor cortex activation, response time facilitation [3] |

| TMS Studies | Motor evoked potentials enhance when viewing graspable objects [3] | Increased motor cortex excitability during affordance perception [3] |

| fMRI Adaptation | Viewing tools activates hand-specific motor regions [3] | Ventral premotor cortex, inferior parietal lobule [3] |

| EEG/ERP | N2pc component sensitive to hand-posture/object match [3] | Visual selection mechanisms tuned to action possibilities [3] |

| Neuropsychology | Brain-damaged patients show selective deficits in object interaction [3] | Dissociations between semantic knowledge and action knowledge [3] |

Experimental Methods and Protocols

Behavioral Paradigms for Studying Affordances

Grip Compatibility Task

Purpose: To investigate how object properties automatically evoke compatible motor responses.

Methodology: Participants are presented with images of objects varying in size (e.g., small berry vs. large apple) or orientation (e.g., handle facing left vs. right). They respond using either precision grip (thumb and index finger) or power grip (whole hand) on response device. Critical trials involve compatibility between object properties and response type [3].

Key Variables:

- Response time differences between compatible and incompatible trials

- Error rates

- Grip force measurements

Neuroscientific Application: This paradigm can be combined with fMRI, TMS, or EEG to identify neural correlates of automatic affordance evocation. Kumar et al. demonstrated that the N2pc component in EEG—indicative of visual selection—is sensitive to match between hand posture and type of action an object affords [3].

Stair Climbability Judgment

Purpose: To investigate how affordance perception is calibrated to the perceiver's action capabilities.

Methodology: Based on Warren's (1984) classic study, participants judge whether stairs are climbable at different ratios of stair height to leg length. Psychophysical functions are plotted to determine the critical boundary where stairs transition from climbable to unclimbable [3].

Key Variables:

- Critical boundary ratio (transition point)

- Sensitivity (slope of psychometric function)

- Perceiver's action capabilities (e.g., leg length, mobility)

Theoretical Significance: This paradigm demonstrates that affordance perception is precisely calibrated to the perceiver's bodily capabilities, supporting Gibson's claim that affordances are relational properties [3].

Neuroimaging Protocols

fMRI Adaptation for Tool-Selective Responses

Purpose: To identify brain regions selectively involved in processing action possibilities afforded by tools.

Methodology: Participants view images of tools and non-tool objects during fMRI scanning. Adaptation paradigms present identical versus different actions with the same tool to identify action-specific rather than object-specific responses [3].

Analysis Approach: Compare BOLD responses in premotor and parietal regions to tools versus non-tools. Effective connectivity analysis can examine information flow between these regions during affordance perception [4].

Computational Models and Theoretical Frameworks

Integrating Behavioral and Neuroscientific Accounts

Recent theoretical work has attempted to reconcile different interpretations of affordances by proposing a unified framework that accommodates both behavioral dispositional accounts and neuroscientific processing accounts [5]. This framework distinguishes between:

Dispositional Account of Nomological Affordance Response: Affordances as necessary relationships that are automatically actualized when certain conditions are met, particularly relevant for understanding pathological cases where patients cannot avoid interacting with affording objects [5].

Dispositional Account of Probable Affordance Response: Affordances as probabilistic relationships that depend on context and current goals, accounting for flexible affordance perception in healthy individuals [5].

This integrative perspective suggests that different dispositional accounts can capture distinct aspects of how affordances operate at the neurocognitive level, both in healthy and pathological subjects [5].

Hierarchical Architecture for Affordance Selection

Computational models of affordance processing often employ hierarchical architectures that address two fundamental challenges: (1) selecting among multiple competing affordances, and (2) organizing behavior hierarchically based on actions and action-goals [4]. These models typically include:

- Perceptual Processing Layers: Extract object properties and spatial relationships

- Affordance Activation Layers: Map object properties to possible actions

- Selection Mechanisms: Resolve competition between alternative actions based on current goals and contextual factors

- Motor Programming Layers: Translate selected affordances into motor commands

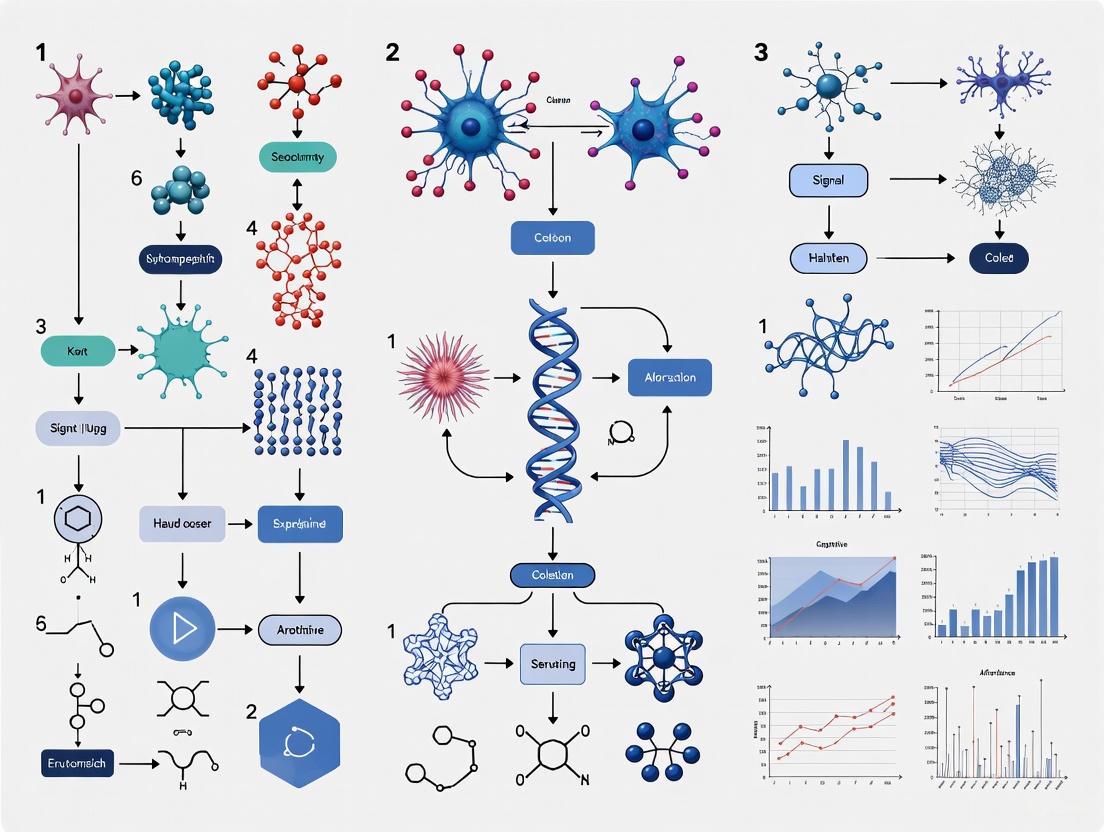

Diagram 1: Hierarchical affordance processing model showing information flow from perception to action.

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Affordance Neuroscience

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | 3T fMRI, High-density EEG, TMS | Localizing neural correlates of affordance perception [3] |

| Eye Tracking | Pupil-core, Tobii Pro | Measuring visual attention during affordance judgment tasks [6] |

| Motion Capture | Vicon, OptiTrack, Kinect | Quantifying action kinematics during object interaction [3] |

| Behavioral Apparatus | Grip force sensors, Response boxes, Touchscreens | Measuring response compatibility effects [3] |

| Stimulus Presentation | E-Prime, PsychoPy, Presentation | Controlled presentation of affordance-relevant stimuli [3] |

| Computational Modeling | MATLAB, Python, NEURON | Implementing and testing computational models [4] |

Clinical and Applied Implications

Neurological Disorders and Affordance Processing

Deficits in affordance perception manifest in various neurological conditions. Patients with optic ataxia following parietal lobe damage struggle to interact with objects despite preserved semantic knowledge about them [3]. Those with utilization behavior due to frontal lobe lesions cannot inhibit automatically evoked actions toward affording objects [5]. Understanding these pathological patterns informs both theoretical models and rehabilitation approaches.

The distinction between nominal and probable affordance responses helps explain different pathological presentations. Patients with utilization behavior may represent a case where probable affordance responses become nominal—triggering automatic actions that cannot be inhibited despite being contextually inappropriate [5].

Applications in Design and Human-Technology Interaction

Donald Norman's adaptation of affordance theory for user experience design has proven highly influential in human-computer interaction [1] [2]. Norman emphasized perceived affordances—what users believe they can do with an interface element—as crucial for intuitive design [2]. This application demonstrates how Gibson's ecological concept can be operationalized in artificial environments, with implications for:

- Interface Design: Creating controls that visually suggest their operation

- Virtual Reality: Designing immersive environments with natural interaction patterns

- Accessibility: Ensuring interfaces afford use by people with diverse capabilities

Future Research Directions

The neuroscience of affordances continues to evolve with several promising research trajectories:

- Multisensory Integration: How visual, haptic, and auditory information combine to specify affordances

- Social Affordances: How we perceive what the environment affords for others, with implications for social cognition [3]

- Developmental Trajectories: How affordance perception emerges and changes across the lifespan

- Computational Modeling: Developing more sophisticated models that bridge neural mechanisms and behavioral outcomes [4]

- Neurorehabilitation: Applying affordance principles to improve motor rehabilitation after brain injury

Recent work by Coello and Cartaud has proposed that peripersonal space may flexibly guide interactions with objects and other people, acting as a buffer against unwanted interactions [3]. This highlights the dynamic, context-dependent nature of affordance perception that remains a rich area for future investigation.

Diagram 2: Interdisciplinary connections in affordance research showing reciprocal influences.

Gibson's theory of affordances as directly perceived action possibilities continues to provide a powerful framework for understanding the perception-action cycle in behavioral neuroscience. The concept's enduring value lies in its ability to bridge multiple levels of analysis—from neural mechanisms to embodied cognition to applied design. As research progresses, integrating behavioral, neuroscientific, and computational approaches will further illuminate how the brain enables organisms to perceive and capitalize on the opportunities for action that their environments provide.

The study of affordances remains particularly relevant for understanding cognitive capital in behavioral neuroscience, as it addresses fundamental questions about how neural resources are deployed to support adaptive, efficient interaction with the environment. By clarifying how action possibilities are perceived and actualized, affordance research contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the neural foundations of adaptive behavior.

The field of cognitive neuroscience is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional reductionist approaches toward a more integrated framework that emphasizes ecological perception and its underlying brain mechanisms. This paradigm shift, largely centered on Gibson's theory of affordances—the action possibilities that the environment offers an organism—recognizes that the human brain has evolved to function within complex, real-world settings rather than controlled laboratory environments [7]. The growing emphasis on ecological validity reflects the understanding that brain functions must be studied within the contexts that characterize our daily lives to achieve meaningful generalizability of findings [7].

This whitepaper examines the neurocognitive transition from theoretical concepts of ecological perception to the empirical identification of specific brain mechanisms, framed within the broader thesis of affordances and cognitive capital in behavioral neuroscience research. We explore how technological advances in mobile brain recording and sophisticated analytical tools have enabled researchers to bridge the gap between abstract psychological constructs and their biological substrates, ultimately informing drug development and therapeutic interventions for neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive disorders [8] [7].

Foundational Theories: From Ecological Psychology to Neuroscience

Gibson's Affordance Theory and Its Neural Correlates

James Gibson's groundbreaking 1979 concept of affordances proposed that organisms directly perceive environmental action possibilities relevant to their current capabilities and goals, without requiring complex cognitive mediation [9]. Subsequent research in psychology and neuroscience has demonstrated that people exhibit exquisite sensitivity to affordances in a manner precisely calibrated to their body's real capabilities, with neuroimaging evidence confirming that actionable objects activate corresponding regions of the neuronal system involved in controlling relevant actions [9].

The neurocognitive architecture supporting affordance perception involves a distributed network including premotor and parietal cortices, which facilitate the translation of environmental features into potential actions [9]. This direct perception-action coupling represents a fundamental component of our cognitive capital—the neural resources that enable adaptive interaction with our environment.

The Challenge of Ecological Validity

Traditional neuroscience research has been criticized for its reductionist approach, which often employs impoverished stimuli and artificial tasks that limit how participants can engage as active agents [7]. As Bannister noted, this approach forces subjects to "behave as little like human beings as possible" to satisfy experimental control requirements [7]. The emerging framework for real-world cognitive science and neuroscience addresses these limitations through a cyclic process of "bringing the lab to the real world" (recording behavior and neural activity in natural settings) and "bringing the real world to the lab" (manipulating environments in laboratory settings) [7].

Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Affordance Perception

Neural Systems for Affordance Processing

Research has identified several key neural systems involved in affordance perception and processing:

- Visuomotor Transformation Systems: Regions including the premotor cortex and posterior parietal cortex activate when viewing tools and objects that afford specific actions, even in the absence of overt movement [9]

- Attention Modulation Networks: The N2pc component in EEG recordings, indicative of visual selection, is sensitive to the match between hand posture and the type of action an object affords [9]

- Technical Reasoning Systems: Contrary to theories suggesting rigid object-behavior links, evidence supports a flexible technical reasoning process that combines currently available environmental transformations to enable complex actions [9]

Clinical Implications of Affordance Processing Deficits

Degradation in affordance perception capacity has emerged as a sensitive marker for neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer's disease (AD). Patients with AD show significant impairments in identifying secondary affordances (alternative uses of familiar tools) while retaining the ability to judge physical properties of the same objects, suggesting a specific deficit in affordance perception rather than general visual processing [8].

Table 1: Affordance Perception Across Neurodegenerative Conditions

| Patient Group | Affordance Perception Ability | Chance Performance Level | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Severely impaired | At chance level | Potential early biomarker |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) | Moderately impaired | Above chance but below normal | Possible prognostic indicator |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Largely preserved | Similar to elderly controls | Differential diagnostic marker |

| Elderly Controls (EC) | Normal performance | Well above chance level | Baseline reference |

This affordance deficit in AD manifests particularly in ideational apraxia, where patients may perform wrong movements or execute sequences in the wrong order, suggesting disruption to the movement formulas stored in the parietal lobe [8]. The detection of affordance perception deficits may provide a non-invasive, economical biomarker for early AD identification, potentially augmenting the diagnostic power of existing neuropsychological tests [8].

Experimental Paradigms and Methodologies

Standardized Protocols for Assessing Affordance Perception

Experiment 1: Secondary Affordance Identification

- Objective: Measure the ability to identify alternative uses of familiar tools as an index of affordance perception capacity [8]

- Task Structure: Single-response Go/No-Go paradigm where participants identify valid secondary affordances [8]

- Stimuli: Common man-made artifacts with both primary and secondary affordances [8]

- Procedure: Participants are presented with object images and must determine whether valid alternative uses exist [8]

- Groups Tested: AD, MCI, PD, and elderly controls, matched for age and education [8]

Experiment 2: Physical Property Judgment

- Objective: Rule out visual processing deficits as the basis for poor affordance perception [8]

- Task Structure: Judgment of physical properties of the same objects used in Experiment 1 [8]

- Results: Even AD patients perform reliably, confirming the specificity of affordance perception deficits [8]

Neuroimaging Approaches

Modern affordance research employs multiple neuroimaging modalities:

- fMRI: Identifies activation patterns in premotor and parietal regions during tool observation [9]

- EEG/ERP: Captures rapid neural dynamics of affordance processing, including N2pc components [9]

- Resting-state fMRI: Measures intrinsic functional connectivity between networks supporting affordance perception [10]

The Neurocognitive Shift in Environmental Neuroscience

From Laboratory to Real-World Environmental Decision-Making

The neurocognitive shift has profoundly influenced our understanding of environmental decision-making, which involves choosing between courses of action that impact the natural environment by weighing immediate costs and benefits against future ones [11]. This process engages brain circuits involved in valuation, self-control, and perspective-taking, with sustainable decision-making requiring the activation of these circuits despite the temporal, social, and spatial distance of environmental benefits [11].

Research indicates that the reward system and Sense of Agency (SoA)—the feeling of controlling one's actions and their consequences—jointly influence environmental behavior [11]. Environmentally damaging behavior often results from immediate gratification overpowering abstract future benefits, compounded by reduced SoA over delayed outcomes [11].

Neural Networks Supporting Pro-Environmental Attitudes

Resting-state fMRI studies reveal that individual differences in pro-environmental attitudes correlate with specific patterns of intrinsic functional connectivity [10]:

Table 2: Neural Correlates of Pro-Environmental Attitudes

| Neural Connection | Network Affiliation | Correlation with Pro-Environmental Attitudes | Potential Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left PPC Bilateral Insula | FPN SN | Positive | Integration of cognitive control with emotional/salience processing |

| Left PPC Right PPC | FPN FPN | Negative | Potential reduction in internal network coherence |

| vmPFC Hippocampus | DMN | Positive | Mentalizing and future thinking about environmental consequences |

| dLPFC thickness | FPN | Positive | Cognitive control for overriding immediate temptations |

Key: PPC = Posterior Parietal Cortex; FPN = Frontoparietal Network; SN = Salience Network; DMN = Default Mode Network; vmPFC = ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex; dLPFC = dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Affordance and Neurocognitive Studies

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | Mobile neural activity recording | Real-world affordance perception studies [7] |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Brain activation mapping | Laboratory-based affordance tasks [9] |

| Eye-Tracking Equipment | Visual attention measurement | Object interaction and affordance perception [9] |

| Go/No-Go Task Paradigms | Response inhibition assessment | Secondary affordance identification [8] |

| Naturalistic Stimuli Sets | Ecologically valid stimulus presentation | Real-world object interaction studies [7] |

| Resting-state fMRI Protocols | Intrinsic connectivity analysis | Network correlates of pro-environmental attitudes [10] |

Visualization of Neurocognitive Workflows

Experimental Protocol for Affordance Assessment

Neural Networks in Environmental Decision-Making

Future Directions and Research Applications

The neurocognitive shift from ecological perception to brain mechanisms opens several promising research directions with significant implications for drug development and therapeutic interventions:

Biomarker Development for Neurodegenerative Diseases

The identification of affordance perception deficits as early markers of Alzheimer's disease provides a non-invasive, economical approach to early detection [8]. Pharmaceutical researchers can leverage this knowledge to develop more sensitive cognitive endpoints for clinical trials targeting early-stage AD, potentially allowing for intervention during the preclinical phase when disease-modifying therapies may be most effective [8].

Cognitive Capital and Therapeutic Design

Understanding the neural bases of affordance processing enables more targeted development of cognitive rehabilitation approaches for patients with apraxia and tool-use deficits [8] [9]. By focusing on the integrity of brain networks supporting affordance perception, researchers can design interventions that directly address the specific neural mechanisms underlying functional impairments in daily activities.

Ecological Validity in Clinical Trial Design

The shift toward real-world neuroscience supports the development of more ecologically valid assessment tools for clinical trials [7]. Pharmaceutical companies can incorporate these paradigms to better predict real-world functional outcomes of cognitive-enhancing medications, moving beyond traditional laboratory-based measures that may not generalize to patients' daily lives.

This whitepaper demonstrates that the neurocognitive shift from ecological perception to brain mechanisms represents not merely a methodological evolution but a fundamental reconceptualization of how we study the brain-behavior relationship, with far-reaching implications for neuroscience research, drug development, and therapeutic innovation.

Cognitive capital represents the cumulative neural and cognitive resources that enable adaptive behavioral responses in complex environments. This whitepaper synthesizes contemporary behavioral neuroscience research to define cognitive capital as the functional product of experience-dependent neuroplasticity and the building of neurogenic reserves [12]. We examine how environmental affordances—opportunities for action provided by the environment—serve as the primary mechanism for building this capital through structured interactions. The document provides a technical framework for quantifying cognitive capital through specific experimental paradigms, neural measurements, and analytical approaches, with particular relevance for research in neurotherapeutic development.

Cognitive capital, within behavioral neuroscience, denotes the brain's capacity for adaptive, optimal performance in goal-directed tasks. This conceptual framework moves beyond static anatomical measures to encompass dynamic, experience-driven enhancements in neural structure and function that constitute a reserve for future adaptive behaviors [12]. The construction of cognitive capital is fundamentally linked to an organism's interaction with environmental affordances. The term "affordance," originating from ecological psychology, refers to the actions that the environment makes possible for an organism—that a chair affords sitting, or a ball affords throwing [3] [5]. These perceived opportunities for action are not passively received but are actively engaged, building behavioral repertoires and informing future decisions [12]. This process of engagement and the resultant neural modifications are the core engines of cognitive capital accumulation.

Contemporary research indicates that neural design is far from simplistic, requiring consideration of context-specific and individual variables to determine functional gains from neuroplasticity [12]. The definition of optimal function is complex, yet behavioral neuroscience offers unique opportunities to evaluate adaptive functions of various neural responses to enhance the functional capacity of neural systems.

Neural Mechanisms and Affordance Processing

The Neurobiological Basis of Cognitive Capital

Cognitive capital is underwritten by multiple, interconnected manifestations of neural plasticity. While adult neurogenesis is often emphasized, other critical mechanisms include:

- Altered Morphology: Increased dendritic spines, modified dendritic branching, and synaptogenesis [12].

- Altered Neurophysiology: Modified synaptic efficacy, such as through Long-Term Potentiation (LTP), which strengthens neural connections in response to experience [12].

- Modified Neural Networks: Large-scale reorganization of functional brain networks supporting complex behaviors [12].

These plastic changes are not automatic; they are driven by an organism's active behavior within its environment. As observed in research, it is the "animals’ behavior and actions in its environment" that instigate dendritic growth and other neural adaptations [12]. Furthermore, studies reveal additive effects between physical activity and exposure to complex environments, suggesting multifaceted pathways for building neural reserves [12].

Neural Systems for Affordance Perception

The perception of affordances and their translation into action is supported by specialized neurocognitive systems. Research in psychology and neuroscience has demonstrated that simply seeing an object biases behavior toward actions that match the object's features (e.g., precision grips for small objects) [3]. Neuroimaging studies provide complementary evidence that actionable objects activate corresponding parts of the neuronal system involved in controlling relevant actions [3].

Two predominant theoretical accounts seek to explain the neural processing of affordances:

- The Dispositional Account of Probable Affordance Response: This "conditional" view, aligned with Scarantino's work, posits that affordances are behavioral dispositions that are likely to be, but are not necessarily, actualized. This account explains usual affordance perception in healthy individuals who perceive multiple potential actions but selectively execute one based on goals and context [5].

- The Dispositional Account of Nomological Affordance Response: This "necessity" view, associated with Turvey, suggests that certain affordances, given the suitable agent-object relationship, have a causal propensity to necessarily actualize. This can account for either the automatic, covert activation of motor systems upon seeing a graspable object, even without overt action, or pathological behaviors in brain-damaged patients who cannot avoid interacting with objects [5].

The integration of these systems with the mirror neuron network is crucial for understanding how organisms select among multiple affordances and organize behavior hierarchically based on action goals [4].

Table 1: Key Neural Correlates of Affordance Processing and Cognitive Capital

| Brain Region | Function in Affordance Processing | Role in Building Cognitive Capital |

|---|---|---|

| Somatosensory Cortex | Processes tactile and bodily sensations during object interaction; exhibits plasticity from repetitive use (e.g., ventral stimulation in lactating rodents) [12]. | Encodes sensorimotor experiences, refining the body schema for more precise future interactions. |

| Hippocampus | Central for spatial navigation and memory; site of experience-dependent adult neurogenesis [12]. | Generates new neurons integrated into networks supporting flexible learning and behavioral flexibility, a core component of cognitive reserve. |

| Prefrontal Cortex | Involved in executive control and goal-directed behavior; critical for selecting among competing affordances [4]. | Supports the development of adaptive strategies and complex decision-making based on accumulated experience. |

| Basolateral Amygdala | Processes emotional valence, such as fear. Activation is reduced in enriched environments during challenging tasks [12]. | Modulates the emotional component of experiences, contributing to emotional resilience, a key aspect of adaptive capacity. |

| Nucleus Accumbens | Key node in the brain's reward circuit. Activation patterns are altered by environmental enrichment [12]. | Links successful interactions with positive reinforcement, motivating further exploration and capital-building behaviors. |

Experimental Paradigms and Quantitative Assessment

Models for Measuring Cognitive Capital

Researchers can operationalize and quantify cognitive capital through several validated behavioral paradigms. The protocols below are designed to elicit and measure the neural reserves and adaptive behaviors that constitute cognitive capital.

Protocol 1: Naturalistic Enriched Environment Housing

- Objective: To assess the impact of complex environmental affordances on neuroplasticity and resilience.

- Subjects: Laboratory rodents (e.g., rats or mice).

- Method:

- Housing Conditions: Subjects are randomly assigned to one of three housing conditions for several weeks:

- Standard (Impoverished): Standard laboratory cage with ad libitum food and water.

- Artificial-Enriched: Larger cage containing various manufactured objects (e.g., plastic toys, tunnels).

- Natural-Enriched: Larger cage containing naturalistic stimuli (e.g., dirt, rocks, sticks).

- Behavioral Sampling: Interactions with objects are recorded and quantified, particularly during the active (dark) phase. Studies show natural-enriched subjects interact with objects approximately 50% more [12].

- Post-Housing Testing: Subjects are evaluated in behavioral assays such as the open field test, novel object test, or a predator threat paradigm to measure anxiety-like behavior and exploratory drive.

- Neural Endpoints: Following behavioral testing, neural activation is quantified using Fos immunolabeling in regions like the basolateral amygdala and nucleus accumbens. Brain tissue may also be analyzed for dendritic branching complexity and neurogenesis rates [12].

- Housing Conditions: Subjects are randomly assigned to one of three housing conditions for several weeks:

Protocol 2: The Water Navigation Challenge Task

- Objective: To measure adaptive problem-solving and resilience under physical and psychological stress.

- Subjects: Rodents or other appropriate animal models.

- Method:

- Apparatus: A water tank with a hidden escape platform. The water is kept at a temperature that is not harmful but is mildly stressful.

- Training: Subjects are trained to locate the platform using spatial cues.

- Challenge Phase: The task is made more complex (e.g., platform location is moved, or distracting stressors are introduced).

- Data Collection:

- Performance: Latency to find the platform, path efficiency, and search strategy.

- Physiological Markers: Plasma levels of stress hormones (e.g., corticosterone) and neuroprotective steroids like DHEA can be measured, as DHEA has been correlated with superior performance in similar extreme challenge tasks [12].

Advanced Analytical Tools

Moving beyond linear statistical models is crucial for analyzing the complex, hierarchical neural representations underlying cognitive capital.

Deep Learning for Neural Data Analysis:

- Application: Deep networks can be applied to neural signals (e.g., electrocorticography (ECoG)) to predict behaviors such as speech production with higher accuracy than linear models [13].

- Utility for Cognitive Capital: The superior predictive power of deep networks allows for a more sensitive measurement of the information content within neural signals. Furthermore, by analyzing the "confusions" of the deep network—what items it misclassifies and what it misclassifies them as—researchers can reveal the latent hierarchical structure the brain uses to organize information (e.g., an articulatory hierarchy for speech sounds) [13]. This structure is a manifestation of built cognitive capital.

- Methodology Summary:

- Data Collection: Record high-density neural signals (e.g., ECoG, EEG) during a complex task.

- Model Training: Train a deep network (e.g., a convolutional neural network) to classify behavioral states or stimuli from the neural data.

- Model Interrogation:

- Use the model's classification accuracy as a proxy for the amount of task-relevant information in the neural signal.

- Analyze the model's confusion matrix to infer the underlying representational structure learned from the brain's activity patterns [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Cognitive Capital in Rodent Models

| Metric Category | Specific Measure | Experimental Paradigm | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Flexibility | Success rate in acquiring reversed task rules; Time taken to extinguish a learned response. | Morris water maze reversal; Operant conditioning extinction. | Higher success rates and faster adaptation indicate greater behavioral flexibility and cognitive reserve. |

| Resilience to Stress | Plasma DHEA-to-Corticosterone ratio; Fos activation in basolateral amygdala vs. nucleus accumbens. | Water Navigation Challenge Task; Predator threat exposure. | A higher DHEA ratio and altered Fos patterns (less amygdala, more accumbens) indicate enhanced emotional resilience. |

| Neural Plasticity | Density of doublecortin (DCX)+ immature neurons in hippocampal dentate gyrus; Dendritic spine density in prefrontal cortex. | Post-mortem histological analysis of brain tissue from enriched environment studies. | Higher densities are direct morphological correlates of increased neural and cognitive capital. |

| Exploratory Drive | Percentage of time interacting with novel vs. familiar objects; Latency to enter a novel environment. | Novel Object Recognition; Open Field Test. | Increased interaction with novelty reflects a broader behavioral repertoire and greater curiosity, fueling future capital accumulation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Investigating Cognitive Capital

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Density ECoG Arrays | Chronic implantation over sensorimotor cortex to record high gamma (Hγ) cortical surface potentials and other frequency bands during complex behaviors like speech or object interaction [13]. |

| DCX & Fos Antibodies | Immunohistochemical labeling of newly born neurons (Doublecortin, DCX) and neural activation (c-Fos) to quantify neurogenesis and map functional neural circuits engaged by affordance-rich tasks [12]. |

| DHEA/Corticosterone ELISA Kits | For quantitative measurement of plasma or serum levels of these hormones, providing a physiological index of stress resilience and neuroprotection during extreme behavioral challenges [12]. |

| Automated Behavioral Tracking Software (e.g., EthoVision) | To provide objective, high-throughput quantification of complex behaviors such as interaction time with objects, locomotor paths, and social approaches in enriched environments. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) | To build and train custom neural networks for analyzing high-dimensional neural data, classifying behavioral states, and uncovering latent representational structures [13]. |

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

Affordance Processing and Cognitive Capital Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow through which environmental affordances lead to the development of cognitive capital and, ultimately, adaptive behavior.

Neuroplasticity Signaling Pathway

This diagram outlines key neurobiological pathways activated by behavioral interactions, leading to the structural and functional changes that constitute cognitive capital.

The framework presented herein defines cognitive capital as a dynamic, plastic resource rooted in measurable neurobiological substrates and built through active engagement with environmental affordances. The experimental and analytical tools detailed—from naturalistic housing and challenge paradigms to deep learning-based neural analysis—provide a roadmap for quantifying this critical resource. For researchers and drug development professionals, this paradigm is essential. It offers a mechanistic basis for understanding how experiential and pharmacological interventions can enhance neural resilience and adaptive capacity. Future research should focus on further elucidating the molecular bridges between specific affordance-driven behaviors and the plasticity mechanisms that expand cognitive capital, paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies in cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders.

The parieto-frontal visuomotor system represents a core network within the primate brain that enables the seamless transformation of visual information into skilled motor actions. This distributed circuitry facilitates our ability to interact with objects in our environment, supporting functions from basic reaching and grasping to complex tool use. Grounded in the theoretical framework of affordance processing—whereby objects automatically activate potential motor actions—this system forms the neural basis for converting perceptual information into motor capital [14]. Contemporary research has moved beyond simple dichotomies of dedicated reaching versus grasping pathways toward a more integrated understanding of how dorsomedial and dorsolateral circuits dynamically interact based on task demands [15]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the parieto-frontal network's functional organization, quantitative properties, and research methodologies, with particular relevance for researchers investigating the neural underpinnings of cognitive-motor integration and neuropsychiatric disorders affecting motor cognition.

Functional Neuroanatomy of Parieto-Frontal Circuits

Core Structural Components

The parieto-frontal visuomotor system comprises highly specialized, reciprocally connected regions that form functional modules for processing distinct aspects of visuomotor control. Hierarchical cluster analysis of corticocortical connectivity reveals that parietal and frontal areas group into clusters typically containing contiguous architectonic fields, forming five distinct medio-laterally oriented pillar domains spanning the posterior parietal, anterior parietal, cingulate, frontal, and prefrontal cortex [16]. This organization creates a sophisticated network architecture that minimizes communication distances, delays, and metabolic costs while supporting specialized information processing streams.

Table 1: Key Regions in the Parieto-Frontal Visuomotor Network

| Brain Region | Architectonic Area | Primary Function | Connectivity Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Intraparietal Area (AIP) | IPL | Processing object intrinsic features (size, shape, orientation) for grasp configuration | Strong connectivity with PMv (F5) [15] |

| Ventral Premotor Cortex (PMv) | F5 | Planning and executing grasping movements; hand shaping | Receives input from AIP; part of dorsolateral circuit [15] |

| V6A | Superior Parietal Lobule | Processing object spatial location (extrinsic features); reaching control | Connected with PMd (F2); contains reaching cells [15] |

| Dorsal Premotor Cortex (PMd) | F2 | Planning and executing arm movements; reaching transport | Receives input from V6A; part of dorsomedial circuit [15] |

Information Processing Streams

The statistical structure of parieto-frontal connectivity reveals several distinct information processing streams that run through the pillar domains [16]. These streams include:

- Fast hand reaching and its control: Primarily involving the dorsomedial circuit

- Hand grasping and manipulation: Primarily involving the dorsolateral circuit

- Complex visuomotor action spaces: Integrating spatial and object information

- Action/intention recognition: Supporting social cognition through mirror mechanisms

- Oculomotor intention and visual attention: Coordinating eye-hand movements

- Behavioral goals and strategies: Higher-order cognitive motor control

- Reward and decision value outcome: Linking action to anticipated outcomes

These specialized streams are embedded within a larger eye-hand coordination matrix, from which they can be selectively activated according to specific task demands [16]. The cingulate domain serves as a central hub where most of these streams converge, integrating information across functional modules.

Quantitative Experimental Data and Findings

Dynamic Causal Modeling of Visuomotor Control

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies using dynamic causal modeling (DCM) have quantified how inter-regional couplings within the parieto-frontal network are modulated by different visuomotor demands. In one pivotal experiment, researchers examined connectivity during planning and execution of reaching-to-grasp movements toward objects of different sizes (LARGE vs. SMALL) [15].

Table 2: Effective Connectivity Changes During Object Grasping

| Condition | Network Modulation | Connectivity Increase | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grasping LARGE objects | Enhanced dorsomedial circuit coupling | V6APMd connectivity | Increased demand for on-line control of transport phase [15] |

| Grasping SMALL objects | Enhanced dorsolateral circuit coupling | AIPPMv connectivity | Increased demand for precision grip and digit configuration [15] |

| Overlap condition | Simultaneous activation of both circuits | Shared regions in both pathways | Integrated control of reach and grasp for complex objects [15] |

This experimental evidence demonstrates that the relative contribution of dorsomedial and dorsolateral circuits is not strictly determined by movement type (reach vs. grasp) but rather by the degree of on-line control required by the specific task parameters [15]. This finding argues against rigidly dedicated cerebral circuits for reaching and grasping in favor of a more flexible, demand-based organization.

Behavioral Metrics in Affordance Processing

Research on affordance perception—how objects automatically activate associated motor codes—has yielded quantitative behavioral data supporting the involvement of parieto-frontal networks in visuomotor transformation. Compatibility effects (faster responses when actions are compatible with object affordances) provide a key metric for quantifying this relationship [17].

Table 3: Compatibility Effects for Objects vs. Words

| Metric | Objects | Words | Statistical Significance | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean compatibility effect size | 29.11 ms | 21.83 ms | F(1,29)=1.05, p=0.31 [17] | Comparable effect sizes for both stimulus types |

| Effect evolution over time | Larger for slow responses | Larger for slow responses | Significant 3-way interaction (F(1,29)=16.66, p<0.001) [17] | Motor activation emerges over time for both |

| Cross-trial carry-over | Immune to previous response | Sensitive to previous response | Different patterns observed [17] | Stronger object-action link through visual pathway |

These behavioral findings demonstrate that both objects and their names automatically activate motor representations, suggesting shared cognitive and neural mechanisms for accessing motor codes [17]. However, the differential carry-over effects suggest a stronger direct link between objects and actions through the visual pathway compared to the linguistic pathway.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

fMRI with Dynamic Causal Modeling

Protocol Title: Assessing Effective Connectivity During Visually Guided Grasping

Experimental Setup:

- Participants perform reaching-to-grasp and place movements while in the MR scanner [15]

- Specialized apparatus allows direct line of sight to objects despite supine position

- Head coil tilted 30° forward along sagittal plane for visual guidance

- Plastic splint constrains arm movement to elbow flexion/extension, minimizing shoulder involvement

- Optical response box records reaction times and movement times

Stimuli and Task:

- Objects consist of large red cube and small green cube attached to supporting rail

- Computer-controlled pneumatic mechanism alternates which cube is on top

- Color-coded LED instructs participants which part to grasp

- Participants grasp specified part, remove object from rail, insert into slot, return to rail

- 252 pseudo-randomized trials across 42 blocks (total scanning time: 45 minutes) [15]

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- fMRI time series acquired during planning and execution phases

- Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) applied to assess inter-regional couplings

- Effective connectivity analyzed within dorsolateral (AIP-PMv) and dorsomedial (V6A-PMd) circuits

- Modulation of connectivity by object size (LARGE vs. SMALL) quantified

Stimulus-Response Compatibility Paradigm

Protocol Title: Quantifying Motor Activation from Object Affordances

Experimental Design:

- Participants prepare hand or foot responses according to instructional cue [17]

- Judge whether object or word is hand-related or foot-related

- Response made by left or right effector indicated by cue

- Compatibility manipulated orthogonally (compatible vs. incompatible trials)

Stimuli and Conditions:

- Two stimulus types: object pictures and corresponding words

- Two stimulus effector types: hand-related vs. foot-related objects/words

- Two response effector types: hand response vs. foot response

- Miniblock design (Experiment 2): participants alternate between hand and foot responses every 4 trials [17]

Dependent Measures:

- Reaction time from stimulus onset to response initiation

- Response accuracy

- Compatibility effect calculated as RT-incompatible minus RT-compatible

- Analysis of carry-over effects across consecutive trials

Visualization of Parieto-Frontal Network Architecture

Information Processing Streams

Figure 1: Information Processing Streams in the Parieto-Frontal Network

Dorsomedial vs. Dorsolateral Circuit Activation

Figure 2: Circuit Specialization for Different Object Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Materials for Parieto-Frontal Visuomotor Studies

| Item/Reagent | Specification | Research Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI-Compatible Grasping Apparatus | Custom-built with pneumatic object rotation | Enables presentation of manipulable objects in scanner environment | Studying neural correlates of reach-to-grasp in humans [15] |

| Retrograde Neural Tracers | Fluoro-Gold, Fast Blue, cholera toxin subunit B | Mapping anatomical connectivity between parietal and frontal regions | Defining parieto-frontal pathways in non-human primates [16] |

| Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) Software | SPM12, Friston et al. 2003 algorithm | Quantifying effective connectivity between brain regions | Assessing how object size modulates AIP-PMv coupling [15] |

| Stimulus-Response Compatibility Setup | E-Prime or Presentation software with response box | Measuring compatibility effects in affordance perception | Quantifying automatic motor activation by objects vs. words [17] |

| Hierarchical Cluster Analysis Algorithms | Custom MATLAB or R scripts | Identifying statistical structure of cortical connectivity | Revealing pillar domains in parieto-frontal network [16] |

The parieto-frontal visuomotor system embodies the neural instantiation of affordance processing, transforming object properties into potential actions through highly specialized yet integrated circuits. The empirical evidence demonstrates that this system operates not through rigid anatomical segregation but via dynamic, demand-based recruitment of computational resources [15] [14]. This organizational principle represents a fundamental aspect of cognitive capital—the neural resources that enable efficient interaction with our environment—with direct implications for understanding both typical brain function and neuropsychiatric disorders characterized by visuomotor deficits.

The statistical structure of parieto-frontal connectivity, with its pillar domains and specialized processing streams, provides a architectural framework for understanding how the brain bridges perception and action [16]. Future research leveraging the experimental protocols and analytical approaches detailed in this whitepaper will further elucidate how this system contributes to the building of cognitive capital across development and how it becomes compromised in neurological and psychiatric conditions, ultimately informing targeted interventions for restoring visuomotor competence.

Affordances, defined as opportunities for action offered by the environment to an agent, are fundamentally shaped by the organism's physical anatomy and action capabilities. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes contemporary research on bodily scaling to elucidate the psychophysical and neurocognitive mechanisms underpinning affordance perception. We examine the critical distinction between body-scaled information (relative to static morphological dimensions) and action-scaled information (relative to dynamic movement capabilities), framing this within an ecological neuroscience perspective on cognitive capital. The analysis covers quantitative psychophysical laws, neural representation findings from fMRI, and advanced concepts of nested affordances, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous framework for understanding how perception and action are adaptively coupled.

The foundational principle of ecological psychology is that perception is for action. Grounded in Gibson's theory, affordances reflect the reciprocal relationship between an organism and its environment [18]. A core tenet is that affordances are not perceived in absolute physical units but are scaled relative to the perceiving agent. This scaling ensures that perceived action possibilities are meaningful to the individual's specific bodily constraints and capacities, a process essential for efficient behavioral investment and the conservation of cognitive capital.

This review posits that bodily scaling operates through two primary, complementary mechanisms:

- Body-Scaling: Affordances are perceived relative to static anatomical dimensions (e.g., leg length, arm span). This offers a stable, readily available metric for perception.

- Action-Scaling: Affordances are perceived relative to dynamic action capabilities (e.g., maximum reach, walking speed). This accounts for biomechanical constraints like strength, flexibility, and skill level, and is particularly critical for nested and skilled actions.

Understanding this distinction is vital for behavioral neuroscience research, as it delineates the complex interplay between an organism's physiological hardware (its body) and its functional software (its capabilities) in generating adaptive behavior.

Core Quantitative Evidence and Psychophysics

The application of psychophysical methods has quantitatively defined the relationship between bodily metrics and perceptual reports of affordances.

Stevens' Power Law in Affordance Perception

Research into the psychophysics of affordance perception reveals a distinct quantitative signature. In studies of perceived maximum forward reachability with an object, affordance perception follows Stevens' power law but with a characteristic scaling exponent [19].

Table 1: Power Law Scaling Exponents (β) for Perceptual Reports

| Perceptual Report | Stimulus | Scaling Exponent (β) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affordance Perception (Reach-with-ability) | Rod Length | 0.32 | Underaccelerated function, similar to brightness perception. |

| Length Perception | Rod Length | 0.73 | Less accelerated, closer to ideal discriminability. |

This key finding demonstrates that perceived reachability is an underaccelerated function of actual changes in reaching ability. This means that as the rod length (and thus actual reaching ability) increases, the reported perceptual magnitude of that reachability increases at a slower rate. This scaling was consistent across self and other judgments and different task contexts (seated vs. standing), suggesting a fundamental property of affordance perception distinct from the perception of pure physical properties like length [19].

The Body-Size Boundary in Object Affordances

Evidence suggests that the human body size acts as a categorical boundary for organizing object-based affordances. A study measuring the affordances of objects spanning a wide range of real-world sizes identified a dramatic decline in affordance similarity for objects larger than the human body [20].

- Experimental Protocol: Participants were presented with a matrix of objects and reported which of 14 common daily actions (e.g., sit-able, grasp-able) each object afforded. Affordance similarity between all object pairs was calculated to construct a similarity matrix [20].

- Key Finding: A clear trough in affordance similarity was found between size rank 4 (77 cm average) and rank 5 (146 cm average), with the similarity dropping to near zero. This boundary of ~104-130 cm aligns with the body size of a typical human adult [20].

- Causal Link: When participants' body schema was manipulated by having them imagine a larger or smaller body size, the location of this affordance boundary shifted accordingly, establishing a causal link between body size and affordance perception [20].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and central finding of this body-size boundary study:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying the body-size affordance boundary.

Methodological Protocols in Bodily Scaling Research

The Shrinking Gap Paradigm

This paradigm investigates the perception of passability through a dynamically changing aperture, requiring the integration of locomotor capabilities.

- Objective: To determine how individuals perceive whether they can pass through a shrinking gap between converging obstacles before it closes [21].

- Setup: Participants navigate in a virtual environment towards a pair of converging obstacles. The gap between them shrinks at a defined rate.

- Key Variable: The critical optical variable is the minimum locomotor speed required (v_min) to pass through the gap safely. This is specified by the distance the observer must travel to the gap's future location (when it reaches their body width) divided by the time remaining until that moment [21].

- Manipulation: Visual and non-visual self-motion information are independently manipulated on catch trials (e.g., by varying virtual walking speed) to dissect their contributions to detecting v_min [21].

- Finding: Participants can accurately judge passability even when stationary, indicating the visual system can recover information about obstacle motion independent of self-motion [21].

Expert Climbers and Nested Affordances

Research on expert rock climbers provides a rich model for studying complex, action-scaled affordances.

- Objective: To examine how expertise modulates the perception of nested affordances—multiple, hierarchically organized action possibilities (e.g., reach-to-touch → grasp → use-to-move-up) [18].

- Protocol: Climbers of varying skill levels are presented with reaches of different complexities:

- Low Complexity: Two nested affordances (e.g., Reach-to-Touch; Reach-to-Grasp).

- High Complexity: More than two nested affordances (e.g., Reach-to-Grasp-with-one-hand → Remove-other-hand → Move-up-to-grasp-another-handhold) [18].

- Measures: Perception of maximum reachability is compared against actual performance. Both body-scaled (arm length, height) and action-scaled (strength, flexibility) metrics are analyzed for their explanatory power [18].

- Findings: For complex, nested affordances, action-scaled measures (capabilities) are superior predictors of perception and performance compared to body-scaled measures (anatomy). Experts exhibit degeneracy (functional equivalence), using different coordination patterns to achieve the same superordinate goal, highlighting their sensitivity to nuanced, nested affordances [18].

Neural and Computational Representations

The neural correlates of bodily scaling provide a window into the cognitive capital invested in affordance perception.

fMRI Evidence for a Neural Affordance Boundary

Neuroimaging evidence supports the behavioral finding of a body-size boundary. An fMRI study revealed a qualitative difference in brain activity when viewing objects within versus beyond one's body-size range [20].

- Finding: Affordance-related processing for objects within the human body size range was represented in both the dorsal and ventral visual streams. In contrast, there was a lack of such affordance processing for objects beyond the body size range [20].

- Implication: The brain's representation of object affordances is ecologically constrained, prioritizing resources for objects that are practically manipulable, thereby optimizing neural computation.

Embodiment in Large Language Models

Intriguingly, a modest affordance boundary at the human body scale was also identified in the large language model ChatGPT, which lacks physical embodiment [20]. This suggests that the statistical structure of human language captures aspects of this bodily scaling, and that such boundaries can emerge from linguistic data alone, informing models of grounded cognition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bodily Scaling Research

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Virtual Reality (VR) Setup with Treadmill | Creates immersive, controllable environments for studying locomotion-based affordances (e.g., shrinking gap paradigm) while allowing for precise manipulation of visual and self-motion cues [21]. |

| Climbing Wall with Instrumented Holds | Provides an ecologically valid platform for studying nested affordances and expert action. Force sensors and motion capture can be integrated to measure kinematics and dynamics of reach, grasp, and use [18]. |

| Report Apparatus (e.g., Adjustable Pulley System) | Allows for precise, quantitative perceptual reports in psychophysical studies (e.g., reporting perceived maximum reachability or object length) without providing numerical cues to the participant [19]. |

| Set of Rods/Varied Objects | A calibrated set of objects (e.g., clear PVC rods) of varying lengths/sizes serves as the physical stimulus set for probing reachability and other body-scaled judgments [19]. |

| Motion Capture System | The gold standard for quantifying body dimensions (anthropometry) and capturing the kinematics of actual performance (e.g., true maximum reach), providing the ground truth against which perceptual reports are compared [18] [19]. |

| fMRI Scanner | Enables non-invasive mapping of neural activity associated with perceiving affordances for objects of different sizes relative to the body, identifying brain regions involved in embodied cognition [20]. |

The following diagram summarizes the logical relationships between key concepts in bodily scaling research, from the organism's properties to the emergence of complex behavior:

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of bodily scaling leading to affordance perception and behavior.

The study of bodily scaling reveals a perception-action system finely tuned to the specific morphological and capability constraints of the individual. The distinction between body-scaling and action-scaling is paramount: while body-scaling provides a foundational heuristic, action-scaling becomes critical for explaining skilled, adaptive behavior in complex environments, representing a higher-order investment of cognitive capital.

Future research, such as that championed by the newly launched Simons Collaboration on Ecological Neuroscience (SCENE), will unite neuroscience and machine learning to discover how the brain encodes these sensorimotor interactions across species [22]. This interdisciplinary approach, leveraging virtual reality, neuroimaging, and sophisticated behavioral paradigms, promises to uncover fundamental principles of how cognition emerges from the embodied relationship between an organism and its environment. For drug development and behavioral neuroscience, this framework underscores the importance of considering an organism's specific physical capital when investigating the neural substrates of behavior and the potential impact of pharmacological interventions on perception-action loops.

Social affordances represent a distinct category of perceptual opportunities—possibilities for social interaction that are directly perceived in the environment, particularly those offered by other agents [23]. This field sits at the intersection of ecological psychology, enactivist philosophy of mind, and behavioral neuroscience, offering a framework for understanding how we navigate our social worlds through direct perception rather than inferential reasoning [23]. Unlike environmental affordances (possibilities for action offered by physical objects), interpersonal affordances involve a unique form of agent-agent coupling that differentiates them fundamentally from agent-environment interactions [23].

The study of social affordances has gained renewed importance within the context of Collective Cognitive Capital—a conceptual framework that synthesizes brain and behavioral data to assess how public policy and social structures affect the cognitive and emotional functioning of populations [24] [25]. This framework argues that cognitive and emotional functioning, and overall brain health, "subserve and maximize individual agency and freedom" [25], positioning social affordances as critical components of societal well-being. When social environments provide rich, appropriate interpersonal action opportunities, they potentially enhance our collective cognitive resources; when they restrict or distort these opportunities, they deplete this vital capital [24].

Theoretical Foundations: From Environmental to Interpersonal Affordances

Defining Social Affordances

The concept of affordances originated in James Gibson's ecological psychology, referring to the perceived possibilities for interaction in an environment, determined by the fit between an agent's abilities and environmental properties [23]. Contemporary research has refined this concept for the social domain:

- Social Affordances: "Possibilities for social interaction or sociability provided by the environment" [23]

- Interpersonal Affordances: Opportunities for interaction afforded specifically by other agents, not merely by the environment in which socializing occurs [23]

The critical distinction lies in recognizing that interpersonal affordances are uniquely interactive [23]. When we perceive another person as affording conversation, collaboration, or conflict, we are not simply perceiving their physical properties but their agency and responsiveness to our own.

The Neuroscience of Perceiving Social Possibilities

Neuroscientific evidence reveals that the perception of affordances generally relies on sensorimotor brain dynamics that reflect potential actions in a given environment [26]. The brain continuously estimates the state of the environment while integrating sensory and motor information to guide behavior [26]. Specific neural oscillations, particularly in the alpha band (8-13 Hz), appear to covary with architectural affordances, with event-related desynchronization (ERD) in parieto-occipital and medio-temporal regions indicating the processing of action possibilities [26].

Table: Key Theoretical Distinctions Between Affordance Types

| Dimension | Environmental Affordances | Interpersonal Affordances |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Physical environment | Other agents |

| Coupling Type | Agent-environment | Agent-agent |

| Neural Correlates | Sensorimotor integration | Mirror systems, mentalizing networks |

| Ethical Dimension | Minimal | Significant (recognition of agency and selfhood) |

| Cultural Variation | Limited | Extensive (social conventions and norms) |

Experimental Approaches and Neural Correlates

Mobile Brain/Body Imaging (MoBI) for Social Affordances

A pioneering approach to studying the neuroscience of affordances uses Mobile Brain/Body Imaging (MoBI) combined with Virtual Reality (VR) to investigate how brain dynamics reflect architectural affordances during navigation tasks [26].

Experimental Protocol:

- Participants: 20 adults (9 female, mean age 28.1 years) with no neurological history [26]

- Setup: Participants navigated a virtual space with two rooms connected by transitions of varying widths (0.2m impassable, 1m passable, 1.5m easily passable) [26]

- Paradigm: S1-S2 motor priming paradigm where S1 revealed transition properties and S2 instructed whether to move through it [26]

- Measurements: 64-channel EEG recording while participants moved freely in physical space corresponding to VR environment [26]

- Trials: 240 trials per participant (40 per condition) [26]

Key Findings:

- Alpha-band event-related desynchronization (ERD) in parieto-occipital and medio-temporal regions covaried with architectural affordances [26]

- Different neural patterns emerged when perceiving poor affordances (narrow, impassable transitions) versus positive affordances (passable transitions) [26]

- The posterior cingulate complex, parahippocampal region, and occipital cortex showed strong ERD of alpha rhythms during affordance processing [26]

These findings demonstrate that brain dynamics systematically reflect behavior-relevant features in the environment, providing a neural basis for how we perceive action possibilities [26].

Social Robot Affordance Alignment Studies

Research on human-robot interaction provides valuable insights into how humans perceive social affordances from artificial agents, with implications for interpersonal perception generally [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Design: 3×3 mixed design examining affordance settings (adult-like, child-like, robot-like) × use cases (informative, emotional, hybrid) [27]

- Participants: 156 interaction samples collected through in-person interactions with social robots [27]

- Robot Platform: Furhat robot with customizable faces and voices [27]

- Measures: Questionnaires assessing perceived competence and warmth before and after interactions, plus semi-structured interviews [27]

Key Findings:

- Static affordances (appearance and voice) significantly affected perceived warmth in first impressions [27]

- Use cases significantly influenced perceived competence and warmth both before and after interactions [27]

- Affordance alignment between static and behavioral features critically impacted user satisfaction and perception [27]

- Some mismatches decreased perceptions (e.g., child-like robot behaving rudely), while others created positive surprise (e.g., robot-like agent using affectionate language) [27]

Table: Quantitative Results from Social Robot Affordance Study

| Experimental Condition | First Impression Warmth | Post-Interaction Competence | User Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult-like (Emotional) | High | Medium-High | High |

| Child-like (Informative) | Medium | Low | Low |

| Robot-like (Hybrid) | Low-Medium | Medium-High | Medium-High |

| Misaligned Conditions | Variable | Significantly Reduced | Significantly Reduced |

Social Affordances and Collective Cognitive Capital

The concept of Collective Cognitive Capital provides a framework for understanding how social affordances at the individual level scale to impact societal functioning and well-being [24] [25]. This framework proposes that we can and should use brain and behavioral science to evaluate public policy decisions by how they affect the cognitive and emotional functioning of people collectively [24].

The Link Between Social Environments and Cognitive Function

Social affordances directly impact cognitive capital through multiple mechanisms:

- Attentional Bandwidth: Finite cognitive resources mean that administrative burdens, social stressors, or impoverished social environments consume attention that could otherwise be directed toward productive social interactions [24]

- Agency Development: Rich interpersonal affordances foster the development of executive function and decision-making capabilities [25]

- Cognitive Load Reduction: Well-designed social environments with clear, appropriate affordances reduce cognitive load, freeing resources for other tasks [28]

Policies that enhance social affordances—such as investing in education, social safety nets, and public spaces—can be reframed as investments in collective cognitive capital [24]. These investments recognize that "it is good for human flourishing when our collective brains work well and together" [24].

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Tools for Studying Social Affordances

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | Mobile EEG (MoBI) | Records brain activity during naturalistic movement and social interaction [26] |