Beyond Memory: The Hippocampus as a Dynamic Hub in Stress Response and Adaptive Decision-Making

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the multifaceted role of the hippocampus, moving beyond its traditional association with memory to explore its critical functions in stress regulation and adaptive decision-making.

Beyond Memory: The Hippocampus as a Dynamic Hub in Stress Response and Adaptive Decision-Making

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the multifaceted role of the hippocampus, moving beyond its traditional association with memory to explore its critical functions in stress regulation and adaptive decision-making. We examine the neurobiological mechanisms through which stress alters hippocampal structure and function, including synaptic plasticity and neuronal excitability, and how these changes impact behavior. The review further explores the hippocampus's contribution to model-based decision-making, spatial representation, and social learning through its interactions with prefrontal-striatal circuits. By integrating foundational knowledge with current methodological approaches, troubleshooting insights, and comparative validations, this article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to understand and target hippocampal-centered pathways in neuropsychiatric disorders.

The Stressed Hippocampus: Neural Mechanisms Linking Stress to Structural and Functional Plasticity

The HPA Axis and Glucocorticoid-Mediated Effects on Hippocampal Circuits

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents the body's primary neuroendocrine stress response system, with glucocorticoids as its final effector hormones. This review examines the complex bidirectional relationship between glucocorticoid signaling and hippocampal neural circuits, focusing on the molecular, cellular, and systems-level mechanisms that underlie stress response integration. We explore how glucocorticoids mediate both adaptive and maladaptive changes in hippocampal function, with particular emphasis on circuit-level computations that may influence broader cognitive and affective processes relevant to stress-related disorders and therapeutic development. The hippocampus exerts powerful inhibitory control over HPA axis activity through multi-synaptic pathways involving intermediary structures such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), creating a critical feedback loop that becomes disrupted in conditions of chronic stress. Understanding these precise circuit mechanisms provides novel targets for intervention in stress pathophysiology and informs drug development strategies for mood and anxiety disorders.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis constitutes the body's central stress response system, coordinating neuroendocrine adaptations to physical and psychological challenges [1]. This axis initiates when parvocellular neurosecretory cells in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the hypophyseal portal system [1]. CRH then stimulates anterior pituitary corticotropes to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into systemic circulation [1]. Upon reaching the adrenal cortex, ACTH triggers the synthesis and release of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents) [1].

Glucocorticoids, as steroid hormones, readily cross the blood-brain barrier and phospholipid bilayers of cells throughout the body and brain to bind intracellular glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) [1]. These ligand-receptor complexes then dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they function as transcription factors to regulate gene expression [1]. The HPA axis is regulated through a negative feedback loop wherein circulating glucocorticoids inhibit their own production by acting on GR-containing neurons in the hypothalamus and pituitary [1]. The hippocampus plays a particularly crucial role in this regulatory circuit, providing tonic inhibition to the HPA axis under basal conditions and contributing to feedback termination of the stress response [2] [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the HPA Axis

| Component | Key Elements | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus | Paraventricular Nucleus (PVN), Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) | Integrates stress signals and initiates neuroendocrine response |

| Pituitary | Anterior Lobe, Corticotropes, Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) | Amplifies hypothalamic signal and stimulates adrenal output |

| Adrenal | Adrenal Cortex, Glucocorticoid Synthesis Enzymes | Produces systemic glucocorticoid hormones |

| Regulatory Centers | Hippocampus, Prefrontal Cortex, BNST | Provide negative feedback and cognitive/contextual modulation |

Hippocampal Regulation of HPA Axis Activity

Circuit Mechanisms of Hippocampal Inhibition

The hippocampus serves as a principal regulator of HPA axis function through inhibitory projections that ultimately suppress CRH neuron activity in the PVN. Despite the fact that hippocampal pyramidal cells are glutamatergic and thus excitatory, their net effect on the HPA axis is inhibitory [2] [3]. This paradox is resolved through a disynaptic inhibitory pathway wherein ventral hippocampal (vHip) outputs excite GABAergic intermediaries that subsequently inhibit CRH-expressing neurons in the PVN [2] [3].

Recent optogenetic studies have identified the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) as a critical intermediary in this regulatory circuit [2] [3]. Channelrhodopsin-assisted circuit mapping in mice revealed that photostimulation of vHip terminals elicits excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in both CRF+ and GAD+ neurons in the BNST, followed by longer-latency inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) [2]. This sequence indicates initial excitation of GABAergic BNST neurons that subsequently inhibit PVN activity. The functional significance of this pathway was confirmed in vivo, where photostimulation of hippocampal afferents to the BNST and PVN attenuated the rise in blood glucocorticoid levels during acute restraint stress [2] [3].

The ventral subiculum, as the primary output structure of the ventral hippocampus, sends substantial projections to the BNST, hypothalamus, and other limbic regions involved in stress regulation [2]. These projections target specific BNST subnuclei rich in GABAergic and CRF+ neurons that in turn project to the PVN, completing the inhibitory circuit [2]. This hippocampal-BNST-PVN pathway represents a crucial neural substrate for the contextual regulation of stress responses, allowing cognitive and contextual information processed by the hippocampus to modulate neuroendocrine output.

Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid Feedback

The hippocampus expresses high densities of both mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) and glucocorticoid receptors (GR), making it exquisitely sensitive to circulating glucocorticoid levels [4] [5]. MRs have approximately 10-fold higher affinity for glucocorticoids than GRs and are largely occupied under basal conditions, while GRs become increasingly occupied as glucocorticoid levels rise during stress [4]. This receptor complement allows the hippocampus to detect and respond to dynamic changes in hormone concentrations.

Under acute stress conditions, glucocorticoid binding to hippocampal GR and MR enhances negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis through genomic mechanisms that ultimately strengthen hippocampal inhibitory output [5]. However, chronic glucocorticoid exposure produces paradoxical effects, disrupting feedback sensitivity through several molecular pathways. Research demonstrates that chronic glucocorticoids in the hippocampus activate an MR-nNOS-NO pathway (mineralocorticoid receptor - neuronal nitric oxide synthase - nitric oxide) that impairs GR function and disrupts feedback inhibition [5]. This pathway involves glucocorticoid activation of MR, subsequent upregulation of nNOS expression, increased NO production, and NO-mediated disruption of GR function via both sGC-cGMP and peroxynitrite signaling pathways [5].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Hippocampal-HPA Axis Regulation

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Optogenetic stimulation of vHip→BNST pathway | Attenuated glucocorticoid response to acute restraint stress; elicited EPSCs and IPSCs in BNST CRF+ and GAD+ neurons | [2] [3] |

| Chronic glucocorticoid administration | Induced HPA axis hyperactivity when administered to hippocampus but not hypothalamus; implicated MR-nNOS-NO pathway | [5] |

| Ventral hippocampal lesions | Resulted in HPA axis hyperactivity and impaired glucocorticoid-mediated feedback inhibition | [2] |

| GR knockdown in hippocampal pyramidal cells | Produced elevated basal glucocorticoid levels and enhanced stress responsiveness | [2] |

Glucocorticoid-Mediated Effects on Hippocampal Circuits

Structural and Functional Plasticity

Chronic exposure to elevated glucocorticoids produces significant structural remodeling within hippocampal circuits. These changes include dendritic atrophy in CA3 pyramidal neurons, reduction in dendritic spine density, and impaired neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus subgranular zone [4]. The mechanisms underlying these structural alterations involve both direct genomic actions of glucocorticoid receptors and indirect non-genomic effects. Glucocorticoids eliminate activity-dependent increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a crucial growth factor for neuronal survival and plasticity, thereby inhibiting experience-dependent dendritic branching [4].

At the functional level, glucocorticoids modulate synaptic plasticity by altering the balance between excitation and inhibition within hippocampal networks. Chronic stress and glucocorticoid exposure impair long-term potentiation (LTP) while facilitating long-term depression (LTD) in the hippocampus, particularly in the CA1 region [6]. These effects involve glucocorticoid-induced changes in glutamate receptor trafficking and function, including reduced surface expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors [6]. Additionally, glucocorticoids enhance hippocampal sensitivity to glutamate excitotoxicity by increasing extracellular glutamate levels and reducing glutamate reuptake, potentially contributing to stress-induced hippocampal damage [4].

Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis

The adult hippocampal dentate gyrus maintains a population of neural stem cells (NSCs) and neural progenitor cells that continue to generate new neurons throughout life [6] [7]. These adult-born neurons undergo a maturation process lasting approximately 4-6 weeks, during which they extend dendrites into the molecular layer, receive synaptic inputs from the entorhinal cortex, and project mossy fiber axons to CA3 pyramidal neurons [6]. This developmental process is highly sensitive to glucocorticoid levels, with acute stress suppressing progenitor cell proliferation and chronic stress impairing multiple stages of neuronal maturation and integration [6] [7].

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) contributes to hippocampal functions by promoting pattern separation - the ability to disambiguate similar experiences or contexts - which is crucial for contextual discrimination and cognitive flexibility [7]. This computational function enables more precise and context-appropriate stress responses by reducing overgeneralization of threatening experiences to safe contexts [7]. Through its effects on neurogenesis and other forms of plasticity, chronic glucocorticoid exposure impairs pattern separation while enhancing pattern completion, potentially contributing to the overgeneralization of fear and stress responses observed in mood and anxiety disorders [7].

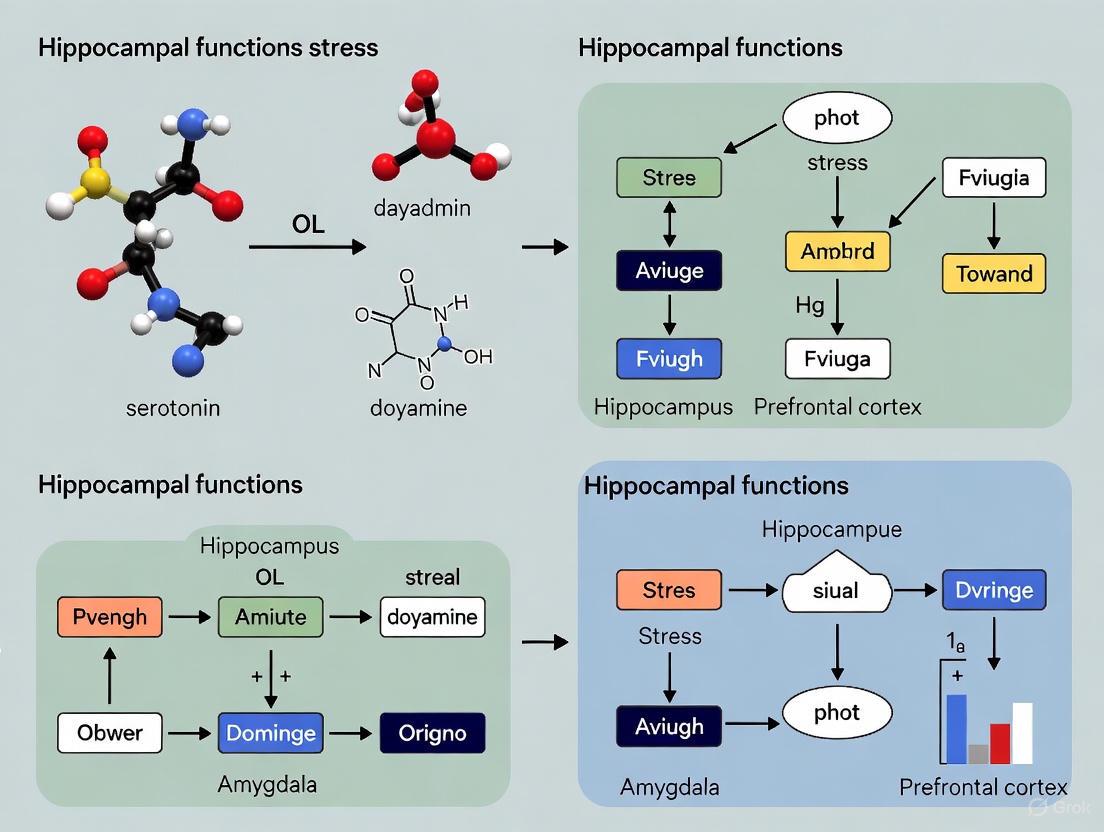

Figure 1: Hippocampal Regulation of HPA Axis. The hippocampus provides inhibitory control over HPA axis activity via a disynaptic pathway through the BNST. Glucocorticoids complete the negative feedback loop by acting on receptors in multiple brain regions.

Chronic Stress, Hippocampal Dysfunction, and Disease Implications

Mechanisms of HPA Axis Dysregulation in Chronic Stress

Chronic stress leads to a progressive dysregulation of the HPA axis characterized by hyperactivity and impaired negative feedback [8] [5]. This state is associated with persistently elevated glucocorticoid levels and reduced sensitivity to glucocorticoid-mediated feedback inhibition. The hippocampus is both a regulator and target of this dysregulation, with chronic glucocorticoid exposure leading to functional GR downregulation and impaired GR signaling [5]. The molecular mechanisms underlying this impairment involve multiple pathways, including increased expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, oxidative stress, and reduced neurotrophic support [8].

In chronic stress conditions, the typically adaptive stress response becomes maladaptive, leading to a cascade of physiological alterations. The "glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis" proposes that chronic stress-induced glucocorticoid exposure causes hippocampal damage, which in turn reduces hippocampal inhibitory control over the HPA axis, leading to further glucocorticoid elevation and progressive hippocampal impairment [4]. This positive feedback loop may contribute to the development and progression of stress-related psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD) [8] [4]. Supporting this model, structural imaging studies frequently demonstrate reduced hippocampal volume in patients with MDD, particularly those with a history of chronic stress or early life adversity [4].

Implications for Drug Development

Understanding the precise mechanisms of glucocorticoid-hippocampal interactions provides multiple targets for therapeutic intervention in stress-related disorders. Potential approaches include GR antagonists, CRH receptor antagonists, MR modulators, and compounds targeting downstream effectors such as nNOS or FKBP5 [5]. Additionally, strategies aimed at enhancing hippocampal resilience, such as neurogenesis-promoting agents or glutamate modulators, may counteract the detrimental effects of chronic glucocorticoid exposure [7].

The development of valid animal models and translational research approaches is crucial for advancing these therapeutic strategies. The chronic mild stress (CMS) paradigm in rodents effectively recapitulates many features of depression, including HPA axis dysregulation and hippocampal alterations [5]. Combining such models with advanced techniques such as optogenetics, chemogenetics, and in vivo imaging allows researchers to dissect circuit-specific mechanisms and test candidate therapeutics with precision.

Table 3: Quantitative Measures of HPA Axis Dysregulation in Chronic Stress

| Parameter | Normal Function | Chronic Stress Alterations | Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Cortisol | Diurnal rhythm with morning peak and evening nadir | Elevated evening levels, flattened rhythm | Salivary cortisol sampling across day |

| CAR (Cortisol Awakening Response) | 50-60% increase within 30 min of awakening | Enhanced response magnitude | Salivary cortisol at 0, 30, 45 min post-awakening |

| Dexamethasone Suppression Test | >50% suppression of cortisol | Reduced suppression (<50%) | 0.5-1.0 mg dexamethasone, measure cortisol |

| DEX/CRH Test | Moderate cortisol/ACTH response | Exaggerated cortisol/ACTH response | CRH administration post-dexamethasone |

| Hippocampal Volume | Age-appropriate volume | 8-10% reduction in MDD | Structural MRI, voxel-based morphometry |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Circuit Manipulation and Mapping Techniques

Elucidating the functional connectivity between hippocampal subregions and HPA axis regulatory centers has been revolutionized by advanced circuit manipulation tools. Optogenetics enables precise temporal control of specific neural pathways using light-sensitive opsins such as channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) [2]. The standard protocol involves stereotaxic injection of AAV vectors carrying Cre-dependent ChR2 into the ventral hippocampus of Cre-driver mouse lines (e.g., CRF-Cre or GAD-Cre mice) [2]. After 4-6 weeks for viral expression and axonal transport, photostimulation of hippocampal terminals in target regions such as the BNST or PVN is performed while recording neural activity or measuring hormonal output [2].

Anatomical tracing approaches remain essential for mapping connectivity within hippocampal-HPA axis circuits. Anterograde tracers such as AAV-EGFP or biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) injected into the hippocampus reveal projection patterns to downstream targets, while retrograde tracers including fluorogold or retrograde AAV variants identify neurons that provide input to the PVN or BNST [2]. Combining these anatomical approaches with immunohistochemistry for immediate early genes (e.g., c-Fos) allows researchers to identify circuits activated by specific stressors or hormonal manipulations.

Hormonal Manipulation and Assessment

Precise manipulation and measurement of glucocorticoid signaling are fundamental to investigating HPA axis-hippocampal interactions. The glucocorticoid synthesis inhibitor metyrapone (100 mg/kg/d, subcutaneous) is used to block stress-induced glucocorticoid elevations and assess glucocorticoid-dependent phenomena [5]. For site-specific manipulations, chronic corticosterone can be administered via intracerebral infusion (e.g., 40 mg/kg/d via osmotic minipump) to specific brain regions while monitoring HPA axis function and behavioral outcomes [5].

Assessment of HPA axis function typically involves measurement of ACTH and corticosterone levels in plasma collected via tail vein or terminal cardiac puncture under baseline conditions and at multiple timepoints following acute restraint stress (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 min) [5]. The dexamethasone suppression test (DEX; 0.05-0.1 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) evaluates negative feedback integrity by measuring the degree of corticosterone suppression following GR agonist administration [4]. The combined dexamethasone-CRH test provides enhanced sensitivity for detecting HPA axis dysregulation by administering CRH (typically 100 μg) after dexamethasone pretreatment and measuring subsequent ACTH and cortisol responses [4].

Figure 2: Experimental Approaches for HPA-Hippocampal Research. Methodologies for investigating HPA axis-hippocampal interactions span circuit manipulation, hormonal assessment, behavioral analysis, and structural characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for HPA-Hippocampal Axis Investigations

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| AAV-CaMKIIa-hChR2-EYFP | Optogenetic activation of hippocampal pyramidal neurons | Enables light-induced activation of specific hippocampal efferent pathways [2] |

| CRF-iCre or GAD-iCre Mice | Cell-type-specific targeting | Allows genetic access to CRF or GABAergic neurons in BNST, PVN [2] |

| Metyrapone | Glucocorticoid synthesis inhibition | Blocks 11-β-hydroxylase to assess glucocorticoid-dependent phenomena [5] |

| Corticosterone (40 mg/kg/d) | Chronic glucocorticoid elevation models | Mimics chronic stress hormone exposure when administered via subcutaneous implantation [5] |

| Dexamethasone (0.05-0.1 mg/kg) | Negative feedback assessment | Synthetic GR agonist tests HPA axis feedback sensitivity [4] |

| CRH (100 μg) | HPA axis activation | Directly stimulates ACTH release from pituitary for challenge tests [4] |

| nNOS inhibitors | Nitric oxide pathway modulation | Tests role of NO signaling in glucocorticoid effects (e.g., 7-NI, L-NAME) [5] |

The intricate relationship between the HPA axis and hippocampal circuits represents a fundamental mechanism through which stress impacts brain function and behavior. Glucocorticoids mediate complex effects on hippocampal networks, modulating synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and circuit dynamics in ways that influence cognitive and affective processes. The hippocampus in turn provides essential inhibitory control over HPA axis activity through multi-synaptic pathways involving structures such as the BNST. Under conditions of chronic stress, this carefully balanced system becomes dysregulated, leading to hippocampal impairment and HPA axis hyperactivity that may contribute to stress-related psychopathology. Elucidating the precise molecular and circuit mechanisms underlying these interactions continues to provide critical insights for developing novel therapeutic approaches that target specific components of this system, offering promise for more effective interventions for mood and anxiety disorders.

This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the impact of chronic stress on hippocampal structure and function, with particular emphasis on the interconnected alterations in synaptic plasticity and adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN). The hippocampus, a brain region critical for cognitive function and emotional regulation, exhibits remarkable plasticity that is profoundly disrupted by chronic stress exposure. We examine the mechanistic pathways through which stress impairs synaptic transmission and dendritic morphology while suppressing the generation of new neurons, processes increasingly implicated in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. The document further explores emerging therapeutic interventions that target these plasticity mechanisms, including probiotic regimens, virome transplantation, and caspase-3 inhibition. Designed for researchers, neuroscientists, and drug development professionals, this review integrates these findings within the broader context of hippocampal function in stress adaptation and decision-making processes, providing both quantitative experimental data and detailed methodological protocols to support ongoing research efforts.

The hippocampus serves as a computational hub within the brain, ideally positioned to detect cues and contexts linked to past, current, and predicted stressful experiences [9]. Through its extensive connections and high degree of input convergence and output divergence, the hippocampus supervises the expression of stress responses across cognitive, affective, behavioral, and physiological domains [9]. This supervisory role depends critically on two fundamental forms of neural plasticity: synaptic plasticity, which underlies the dynamic strengthening and weakening of connections between existing neurons, and neurogenesis, the birth and integration of new neurons throughout adulthood.

The hippocampus is functionally segmented along its dorsoventral axis, with the dorsal portion more strongly associated with cognitive functions such as spatial learning and memory, while the ventral hippocampus plays a more prominent role in emotional regulation and stress response [10]. Chronic stress exposure disrupts the delicate balance of plasticity mechanisms across these hippocampal subregions, leading to structural reorganization and functional impairments that manifest in behavioral phenotypes relevant to neuropsychiatric disorders. Understanding these stress-induced alterations provides critical insights for developing targeted interventions that restore hippocampal plasticity and promote adaptive functioning.

Impact of Chronic Stress on Synaptic Plasticity

Stress-Induced Synaptic Weakening and Signaling Mechanisms

Chronic stress exposure produces significant impairments in synaptic plasticity, particularly through weakening of synaptic connections in the hippocampus. Research using chronic restraint stress (CRS) models in mice has demonstrated that stress selectively suppresses basal synaptic transmission in the ventral hippocampus, a region critically involved in emotional regulation, while sparing the dorsal hippocampus [10]. This regional specificity highlights the vulnerability of emotion-related circuits to stress-induced synaptic dysfunction.

The molecular mechanisms underlying stress-induced synaptic weakening involve caspase-3 activation triggered by glucocorticoid signaling. Corticosteroids activate a synapse-weakening pathway through caspase-3 in the hippocampus, leading to reduced synaptic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) expression through calcium-dependent mechanisms [10]. This process shares similarities with physiological long-term depression (LTD), a normal mechanism for synaptic pruning, but when pathologically activated by chronic stress, contributes to excessive synaptic weakening that underlies depressive symptomatology.

Table 1: Quantitative Measures of Stress-Induced Synaptic Alterations

| Parameter Measured | Experimental Group | Control Group | Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal synaptic transmission in ventral hippocampus | Suppressed | Normal | p < 0.05 | [10] |

| Dendritic spine density on CA1 (apical) | Decreased | Normal | Significant | [11] |

| Basal dendritic arborization in CA1 | Atrophy | Normal | Significant | [11] |

| BLA pyramidal neuron dendritic arborization | Enhanced | Normal | Significant | [11] |

Structural Remodeling of Dendritic Arbors

Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling across different brain regions, creating an imbalance in neural circuitry that processes stressful experiences. In the hippocampus, repeated social defeat stress produces significant dendritic atrophy of CA1 basal dendrites and decreased apical dendritic spine density [11]. This stress-induced structural simplification reduces the computational capacity of hippocampal neurons and limits their connectivity within cognitive networks.

Conversely, the same stress paradigm elicits enhanced dendritic arborization in pyramidal neurons of the basolateral amygdala (BLA) [11]. This opposing pattern of plasticity creates a neural imbalance where emotion-related circuits gain influence while cognitive-control circuits become diminished. Such divergent structural changes may underlie the cognitive deficits and heightened emotional reactivity observed in stress-related psychiatric conditions. The medial prefrontal cortex appears more resilient to these particular structural changes, with social stress failing to induce lasting morphological alterations in this region [11].

Suppression of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis by Chronic Stress

Mechanisms of Neurogenesis Suppression

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN), the process of generating new neurons throughout life in the dentate gyrus, represents one of the most robust forms of neuroplasticity in the mammalian brain. Chronic stress significantly suppresses multiple stages of this process, from initial neural progenitor proliferation through differentiation, maturation, and functional integration of new neurons [12] [9]. This suppression occurs primarily through glucocorticoid-mediated mechanisms that alter the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, ultimately affecting the morphology and function of the hippocampus.

The impact of stress on neurogenesis involves complex molecular pathways where excess glucocorticoids during stress target neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs) [12]. The mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) differentially influence NSPC proliferation and differentiation—low cortisol levels promote human hippocampal progenitor cell proliferation through MR function, while high cortisol levels via GR suppress proliferation and neuronal differentiation [12]. This receptor-specific activity demonstrates the nuanced regulation of neurogenesis by stress hormones and explains how prolonged stress exposure leads to sustained suppression of neuronal production.

Functional Consequences of Impaired Neurogenesis

The functional implications of stress-suppressed neurogenesis extend beyond simple neuronal replacement. AHN contributes critically to pattern separation—the ability to distinguish between similar experiences or contexts—and cognitive flexibility [9] [7]. By biasing hippocampal computations toward enhanced conjunctive encoding and pattern separation, adult-born neurons normally promote contextual discrimination and reduce proactive interference, preventing the generalization of stressful experiences to safe contexts [9].

When neurogenesis is suppressed, these adaptive functions become compromised, leading to maladaptive behaviors and impaired stress coping. The literature has historically divided the functional impact of AHN into cognitive (memory-related) and affective (stress response) dimensions, but these likely represent two manifestations of a fundamental role in adaptation [9] [7]. Through its computational influences on hippocampal information processing, AHN shapes adaptation to environmental demands, enabling cognitive, behavioral, and physiological responses to be more appropriately matched with contextual requirements [7].

Table 2: Effects of Chronic Stress on Neurogenesis and Recovery Interventions

| Parameter | Effect of Chronic Stress | Intervention | Outcome Post-Intervention | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial learning & memory | Disrupted | Probiotic administration | Improved behavioral functions | [13] |

| Hippocampal synaptic plasticity | Disrupted (no LTP) | Probiotic administration | Restored synaptic plasticity | [13] |

| Serum oxidant/antioxidant balance | Decreased antioxidants, increased oxidants | Probiotic treatment | Improved oxidant/antioxidant profile | [13] |

| Social interaction behavior | Reduced | Faecal virome transplant (FVT) | Restored social investigatory behavior | [14] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Chronic Stress Paradigms

Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS) Protocol: The CUMS model exposes rodents to a series of mild, unpredictable stressors over several weeks (typically 4-8 weeks) to simulate the persistent, low-grade stress experienced in human populations. Stressors include restraint, cage tilting, damp bedding, light-dark cycle alterations, and periodic food/water deprivation, presented in an unpredictable sequence to prevent habituation [13]. This paradigm effectively disrupts spatial learning and memory, suppresses synaptic plasticity, and creates an imbalance in serum oxidant/antioxidant factors, providing a comprehensive model for studying stress-induced physiological and behavioral alterations [13].

Chronic Social Stress Protocols: Social stress paradigms utilize ethologically relevant stressors through resident-intruder confrontations or social defeat. In a typical protocol, male experimental mice or rats are introduced into the territory of larger, aggressive residents for brief daily sessions (5-10 minutes) over 5-10 consecutive days, resulting in clear social avoidance behavior [14] [11]. This approach produces robust and persistent changes in social behavior, immune function, and structural plasticity in both hippocampal and amygdalar circuits [14] [11].

Assessment Techniques for Synaptic Plasticity and Neurogenesis

Electrophysiological Analysis of Synaptic Function: Brain slice electrophysiology provides direct measurement of synaptic strength and plasticity. Acute hippocampal slices (300-400μm thickness) are prepared following stress paradigms, and field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) are recorded in response to Schaffer collateral stimulation in the CA1 region [10]. Measurements include input-output curves to assess basal synaptic transmission and paired-pulse ratios to evaluate presynaptic function. Long-term potentiation (LTP), a cellular model for learning and memory, is induced using high-frequency stimulation protocols, with stress typically impairing LTP induction and maintenance [13] [10].

Structural Analysis of Dendritic Morphology: Golgi-Cox staining remains the gold standard for visualizing complete neuronal arborization and dendritic spine density. Following stress protocols, brains are processed using commercial Golgi-Cox kits, with impregnated neurons randomly selected from specific hippocampal subregions (CA1, CA3, DG) [11]. Detailed morphometric analyses include Sholl analysis to quantify dendritic complexity (counting intersections of dendrites with concentric circles centered on the soma) and spine density quantification along apical and basal dendritic segments [11].

Tracking Adult Neurogenesis: Multiple complementary approaches assess different stages of AHN. Immunohistochemistry using cell-type-specific markers identifies neural progenitors (GFAP, Sox2), proliferating cells (Ki67), immature neurons (Doublecortin/DCX), and mature neurons (NeuN) [15]. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling, administered prior to sacrifice, allows birth-dating and tracking of newborn cells through their development and maturation [15]. Functional integration is assessed using retroviral vectors expressing fluorescent proteins, which specifically label dividing cells and their developing processes, allowing detailed analysis of dendritic and axonal maturation and connectivity [15].

Emerging Therapeutic Interventions and Mechanisms

Probiotic and Virome-Based Approaches

Recent research has revealed promising interventions targeting the microbiota-gut-brain axis to counteract stress-induced hippocampal alterations. Administration of specific probiotic mixtures to stressed animals improves behavioral functions, restores synaptic plasticity, and rebalances serum oxidant/antioxidant profiles [13]. Different probiotic cocktails appear to produce similar beneficial effects on hippocampus-dependent cognition and synaptic plasticity, suggesting possible convergent mechanisms of action [13].

Even more remarkably, faecal virome transplants (FVT) from non-stressed donors to stressed recipients can prevent stress-associated behavioral sequelae and restore stress-induced changes in immune parameters and bacteriome alterations [14]. This approach utilizes bacteriophages—viruses that specifically target bacteria—to remodel the gut microbiome without transferring live microorganisms. FVT treatment protects against stress-induced deficits in social investigatory behavior, improves locomotor and anxiety-like behaviors, and normalizes corticosterone responses to forced swim test stress [14]. The transfer of specific viral populations, particularly those from the class Caudoviricetes, is associated with these protective effects, indicating that virome-directed therapies represent a novel approach for modulating the microbiota-gut-brain axis during stress [14].

Molecular Targets and Signaling Pathways

At the molecular level, caspase-3 inhibition has emerged as a promising strategy for preventing stress-induced synaptic weakening. Local administration of Z-DEVD-FMK, a cell-permeable and irreversible caspase-3 inhibitor, into the ventral hippocampus blocks the synaptic depression induced by chronic stress [10]. This intervention prevents the internalization of AMPA receptors and preserves synaptic function despite stress exposure, highlighting the potential of targeting specific synaptic weakening pathways for therapeutic benefit.

The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in stress-induced hippocampal alterations:

Diagram Title: Stress-Induced Hippocampal Alterations and Intervention Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Stress-Induced Hippocampal Alterations

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Examples | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) | Thymidine analog labeling dividing cells | Birth-dating and tracking newborn neurons | [15] |

| Doublecortin (DCX) antibody | Marker of immature neurons | Identifying and quantifying newborn neurons | [15] |

| Golgi-Cox staining kit | Complete neuronal visualization | Dendritic arborization and spine density analysis | [11] |

| Z-DEVD-FMK | Caspase-3 inhibitor | Blocking stress-induced synaptic weakening | [10] |

| Probiotic mixtures | Gut microbiome modulation | Restoring stress-induced cognitive deficits | [13] |

| Caudoviricetes phages | Virome component | FVT for stress resilience | [14] |

The evidence reviewed herein establishes that chronic stress induces coordinated alterations in synaptic plasticity and adult neurogenesis within the hippocampus, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of maladaptive plasticity that compromises cognitive function and emotional regulation. The functional interconnection between these two forms of plasticity suggests that therapeutic strategies should target both processes simultaneously for optimal efficacy. Emerging interventions focusing on the microbiota-gut-brain axis, particularly probiotic regimens and faecal virome transplantation, represent promising avenues for restoring hippocampal homeostasis by engaging multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

Future research should prioritize temporal mapping of the progression from initial stress exposure to established plasticity alterations, identifying critical windows for intervention. Additionally, the development of cell-type-specific approaches that selectively modulate vulnerable neuronal populations while preserving overall circuit function will advance both our mechanistic understanding and therapeutic capabilities. As techniques for monitoring and manipulating neural circuits in real-time continue to evolve, so too will our ability to precisely counteract the detrimental effects of chronic stress on hippocampal function, ultimately promoting resilience in the face of adverse experiences.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram summarizes a comprehensive experimental approach for investigating stress-induced hippocampal alterations:

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Stress Hippocampal Research

Ventral Hippocampal Hyperexcitability as a Neural Substrate for Anxiety

The ventral hippocampus (vHPC) has emerged as a critical hub in the neurocircuitry of anxiety, serving as a key interface between cognitive processes and emotional regulation. Within the broader context of hippocampal functions in stress and adaptive decision-making research, the vHPC occupies a pivotal position, processing threat-related contextual information and modulating defensive behaviors [16] [17]. This region displays a remarkable functional segregation along the hippocampal longitudinal axis, with the ventral pole specialized for emotional and stress-related processing, contrasting with the dorsal hippocampus's role in spatial cognition and memory [16]. The conceptual framework of hippocampal-dependent anxiety posits that vHPC hyperexcitability disrupts the normal balance of neural activity, leading to maladaptive anxiety states that characterize stress-related psychiatric disorders [18] [17].

The neurobiological basis of anxiety is intimately linked to the hippocampus's capacity for relational memory representation, which enables the flexible use of information to guide behavior in complex environments [16]. In pathological states, this flexible cognition becomes compromised, giving way to rigid, anxiety-driven responses. The vHPC functions as a computational hub that detects cues and contexts linked to stressful experiences and supervises the expression of stress responses across cognitive, affective, behavioral, and physiological domains [7]. This review synthesizes current evidence establishing ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability as a fundamental neural substrate for anxiety, examining its mechanistic bases, functional consequences, and implications for therapeutic development.

Mechanisms of Ventral Hippocampal Hyperexcitability

Cellular and Synaptic Substrates of Hyperexcitability

The emergence of hyperexcitability within ventral hippocampal circuits involves distinct pathophysiological processes at cellular and synaptic levels. In experimental models of temporal lobe epilepsy, which exhibits notable psychiatric comorbidity including anxiety, vCA1/subiculum principal neurons demonstrate significant electrophysiological alterations. These include depolarized resting membrane potentials and reduced synaptically driven hyperpolarizations during alveus stimulation, indicating profound disinhibition of ventral hippocampal circuits [18]. This disinhibition is further compounded by reductions in parvalbumin (PV) and somatostatin (SST) interneuron densities in stratum oriens, creating an environment permissive for hyperexcitability [18].

The inhibitory control of ventral hippocampal circuits demonstrates remarkable specialization, with distinct GABAergic microcircuits orchestrating the activity of pyramidal neuron subpopulations to shape different emotional states. Research reveals that somatostatin (Sst) interneurons in the vCA1 play a particularly important role in fear behavior, with nearly half of these interneurons displaying plastic inhibitory responses during trace fear learning [19]. During cued fear memory tests, an even larger fraction (68.4%) of Sst interneurons exhibits inhibitory responses to conditioned threat-predicting stimuli [19]. This specialized inhibitory patterning enables the emergence of task-specific pyramidal neuron ensembles for anxiety versus fear processing.

Neurotransmitter and Neuromodulator Systems

Dysregulation of dopaminergic modulation represents another significant mechanism contributing to ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability. Experimental evidence from Alzheimer's disease models demonstrates that dopamine neuron degeneration in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) impairs hippocampal dopaminergic innervation, resulting in reduced D2-receptor-mediated activation of the CREB pathway in parvalbumin interneurons [20]. This dopaminergic deficit diminishes PV-IN firing, weakens inhibition of pyramidal neurons, and ultimately induces hippocampal hyperexcitability [20]. Importantly, this hyperexcitable state can be rescued by D2-receptor agonists such as quinpirole, which restore p-CREB levels in PV-INs and improve inhibitory function [20].

Stress hormones exert complex modulatory effects on hippocampal excitability through genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. Glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in the hippocampus mediate biphasic effects on neuronal excitability, with imbalances leading to hyperexcitability states [21]. Chronic stress produces structural remodeling of hippocampal neurons, including dendritic shrinkage of CA3 neurons and spine loss in CA1, which alters circuit function and contributes to anxiety-related behaviors [21]. These structural changes involve multiple mediators beyond glucocorticoids, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and endocannabinoids [21].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms Contributing to Ventral Hippocampal Hyperexcitability

| Mechanistic Category | Specific Alterations | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitory Circuit Dysfunction | Reduced PV+ and SST+ interneuron density in stratum oriens [18] | Disinhibition of principal neurons, increased network excitability |

| Interneuron Specialization | Distinct Sst interneuron responses to anxiety vs. fear stimuli [19] | Separation of emotional processing microcircuits |

| Dopaminergic Modulation | Reduced VTA dopamine input, impaired D2-receptor signaling [20] | Decreased CREB activation in PV interneurons, reduced inhibition |

| Structural Plasticity | Chronic stress-induced dendritic retraction in CA3/CA1 [21] | Altered circuit connectivity and information processing |

| Receptor Signaling | Imbalanced MR/GR activation, altered GluNR2B-containing NMDA receptors [7] [21] | Enhanced excitability, modified synaptic plasticity |

Functional Link Between vHPC Hyperexcitability and Anxiety Behaviors

Behavioral Manifestations of vHPC Hyperexcitability

Ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability manifests in specific anxiety-related behavioral phenotypes across multiple experimental paradigms. In epileptic mice, social memory deficits emerge alongside anxiety-like behaviors, with animals showing impaired social discrimination despite preserved social approach behavior [18]. These mice also display reduced center preference in the open field test and exhibit high-velocity movement bouts, both indicative of heightened anxiety states [18]. Crucially, chemogenetic inhibition of vCA1 principal neurons increases the probability of successful social discrimination and normalizes center preference and movement patterns, directly linking vCA1 hyperexcitability to these behavioral deficits [18].

The functional specialization of the ventral hippocampus is evidenced by the segregation of anxiety and fear circuits within the vCA1. In vivo calcium imaging reveals that distinct subpopulations of vCA1 pyramidal neurons represent anxiety and fear behaviors, with minimal overlap between these ensembles [19]. Specifically, approximately 37.7% of vCA1 pyramidal neurons consistently show enhanced activity in anxiety-inducing tasks such as the elevated plus maze and forced anxiety-shifting task, while a separate population (39.7%) responds to conditioned fear stimuli [19]. This functional segregation enables targeted regulation of specific emotional behaviors through dedicated microcircuits.

Cognitive and Adaptive Deficits

The impact of vHPC hyperexcitability extends beyond traditional anxiety measures to encompass broader cognitive and adaptive functions. The hippocampus supports flexible cognition through the encoding and flexible expression of relational memory representations, allowing for adaptive behavior in complex environments [16]. When hippocampal hyperexcitability disrupts this function, behavior becomes driven by inappropriate, inflexible, and stereotypical responses rather than appropriately contextualized decisions [16]. This manifests as an inability to modify behavior based on subtle contextual differences, precisely the deficit observed in anxiety disorders.

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) represents another mechanism through which vHPC hyperexcitability may influence anxiety and adaptive behavior. AHN promotes contextual discrimination between overlapping experiences and memories, enabling individuals' responses to be more appropriately matched with the context [7]. By biasing hippocampal computations toward enhanced conjunctive encoding and pattern separation, AHN reduces proactive interference and generalization of stressful experiences to safe contexts [7]. When hyperexcitability or stress disrupts AHN, this adaptive function is compromised, potentially contributing to anxiety disorders characterized by excessive threat generalization.

Table 2: Behavioral Paradigms for Assessing vHPC Hyperexcitability-Related Anxiety

| Behavioral Paradigm | Specific Behavioral Measures | Relationship to vHPC Hyperexcitability |

|---|---|---|

| Social Discrimination Test | Ability to distinguish novel from familiar conspecifics [18] | Impaired discrimination despite preserved approach in hyperexcitable state |

| Open Field Test | Center preference, locomotor patterns, high-velocity bouts [18] | Reduced center exploration, increased erratic movement |

| Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) | Open arm exploration time, risk assessment behaviors [19] | Decreased open arm exploration; reversible with vCA1 inhibition |

| Forced Anxiety-Shifting Task (FAST) | Hesitation to extend beyond elevated platform [19] | Specific vCA1 pyramidal neuron activation during anxiogenic trials |

| Trace Fear Conditioning | Freezing response to conditioned threat-predicting cues [19] | Distinct vCA1 neuronal population activated; separable from anxiety circuits |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Chemogenetic Modulation Protocols

Chemogenetic Inhibition of vCA1 Principal Neurons: This protocol utilizes Cre-dependent Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) expressed in vCA1 principal neurons. For inhibition, the hM4Di or KORD receptors are targeted using stereotaxic injection of AAV vectors carrying the receptor sequence under the CaMKIIα promoter (for principal neuron-specific expression) into the vCA1 of adult mice (coordinates: AP: -3.3 mm, ML: ±3.2 mm, DV: -4.2 mm from bregma) [18]. Following 3-4 weeks of expression, the designer ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) is administered intraperitoneally (3 mg/kg) 30 minutes prior to behavioral testing. For KORD receptors, salvinorin B (2.5 mg/kg) is used as the activating ligand. Whole-cell recordings confirm that CNO hyperpolarizes hM4Di-expressing cells by approximately 5 mV and decreases current-evoked spiking [18].

Chemogenetic Excitation Protocol: For excitation of vCA1 principal neurons, the hM3Dq DREADD is expressed using similar viral delivery methods. CNO administration (same dosage) depolarizes hM3Dq-expressing cells, increasing their excitability. This bidirectional control allows establishment of causal relationships between vCA1 activity states and anxiety behaviors [18].

In Vivo Calcium Imaging During Anxiety Behaviors

vCA1 Pyramidal Neuron Imaging in Freely Behaving Mice: This methodology enables monitoring of neuronal population activity during anxiety behaviors. The genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f is expressed in vCA1 pyramidal neurons using AAV vectors under the CaMKIIα promoter. A gradient refractive index (GRIN) lens is implanted above the vCA1, and a head-mounted miniature microscope is used for imaging [19]. Mice are subjected to anxiety tests (elevated plus maze, forced anxiety-shifting task) while neuronal activity is recorded. Data analysis includes motion correction, source extraction, and deconvolution of calcium transients using standardized pipelines. Cells are classified as anxiety-responsive based on significantly elevated activity during anxiogenic components of tasks compared to safe periods [19].

Dual-Color Imaging with Optogenetic Manipulation: For simultaneous manipulation and imaging, a dual-color miniscope is employed to image vCA1 pyramidal neuron activity (GCaMP6f) while optogenetically activating interneurons (e.g., Sst interneurons expressing ChrimsonR) [19]. This approach enables real-time assessment of how specific interneuron populations shape pyramidal neuron activity during anxiety behaviors.

Electrophysiological Characterization of Hyperexcitability

Whole-Cell Recordings from Labeled vCA1/Subicular Neurons: Acute brain slices containing the ventral hippocampus are prepared following perfusion with ice-cold slicing solution. Neurons are visualized using infrared differential interference contrast microscopy, and mCherry-labeled principal neurons are identified for patching. Recording parameters include resting membrane potential, input resistance, action potential threshold, and firing patterns in response to current injections [18]. To assess synaptic inhibition/excitation, alveus stimulation is performed while recording synaptically driven hyperpolarizations. Hyperexcitable states are identified by depolarized resting membrane potentials and reduced inhibitory postsynaptic potentials [18].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating vHPC Hyperexcitability

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| DREADDs (hM4Di, KORD, hM3Dq) | Chemogenetic manipulation of neuronal activity [18] | Bidirectional control of principal neuron excitability in vivo |

| AAV-CaMKIIα-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry | Targeted expression in vCA1 principal neurons [18] | Cre-dependent inhibitory DREADD expression for circuit manipulation |

| GCaMP6f | In vivo calcium imaging of neuronal populations [19] | Monitoring ensemble activity during anxiety behaviors |

| eNpHR3.0 | Optogenetic inhibition of pyramidal neurons [19] | Precise temporal control of neuronal silencing during behavior |

| Cre-dependent GCaMP6f (AAV-Syn-FLEX-GCaMP6f) | Cell-type specific calcium imaging [19] | Monitoring activity in specific interneuron populations (e.g., Sst, PV) |

| Quinpirole | D2 receptor agonist intervention [20] | Rescue of dopaminergic signaling deficits and PV interneuron function |

| CNO (Clozapine-N-Oxide) | DREADD receptor activation [18] | Chemogenetic actuator for in vivo neuronal manipulation |

| Anti-Parvalbumin Antibody | Immunohistochemical identification of PV+ interneurons [18] | Quantification of interneuron density and distribution |

| Anti-Somatostatin Antibody | Identification of SST+ interneurons [18] [19] | Assessment of specific interneuron population integrity |

Visualization of Key Mechanisms and Experimental Approaches

Ventral Hippocampal Microcircuits in Anxiety and Fear

Diagram 1: Functional Segregation of vHPC Microcircuits in Anxiety and Fear. Distinct subpopulations of vCA1 pyramidal neurons encode anxiety versus fear behaviors with minimal overlap. SST interneurons provide specialized inhibitory control for fear-related circuits [19].

Mechanisms Driving vHPC Hyperexcitability in Anxiety

Diagram 2: Pathological Mechanisms Converging on vHPC Hyperexcitability in Anxiety. Multiple insults lead to hyperexcitability through distinct but convergent cellular mechanisms, resulting in characteristic behavioral deficits [18] [20] [21].

Discussion and Therapeutic Implications

The evidence consolidated in this review firmly establishes ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability as a critical neural substrate for anxiety, particularly in the context of stress-related psychiatric disorders and neurological conditions with psychiatric comorbidity. The functional specialization within vCA1 microcircuits, with distinct neuronal ensembles dedicated to anxiety versus fear responses, provides a refined framework for understanding the neural basis of negative emotional states [19]. This functional segregation at the microcircuit level parallels the broader longitudinal specialization along the hippocampal axis and offers promising targets for therapeutic intervention.

The therapeutic implications of these findings are substantial. The demonstration that chemogenetic inhibition of vCA1 principal neurons can restore social memory function and normalize anxiety-related behaviors in epileptic mice, despite persistent interneuron loss, supports the potential of targeting ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability for treating cognitive and affective comorbidities in epilepsy and possibly other disorders [18]. Similarly, the rescue of hippocampal hyperexcitability in Alzheimer's disease models through D2 receptor agonism suggests that dopaminergic restoration may have therapeutic benefits beyond motor symptoms [20]. These approaches highlight the importance of circuit-based interventions that modulate neuronal activity patterns rather than simply targeting specific neurotransmitters.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular and cellular mechanisms that confer vulnerability to hyperexcitability in stress-related disorders, developing more targeted interventions for specific vHPC microcircuits, and exploring the translational potential of these findings through human imaging studies and clinical trials. The integration of ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability into a broader conceptual framework of hippocampal function in stress and adaptive decision-making will continue to yield important insights into the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders and their treatment.

Relational Memory Representations as the Foundation for Cognitive Flexibility

Relational memory, the ability to bind distinct elements of experience into a coherent representation, is a core function of the hippocampal formation. This whitepaper synthesizes recent advances in neuroscience to establish how the hippocampus supports cognitive flexibility through the encoding and flexible expression of relational memory representations. We detail the mechanistic basis by which hippocampal circuits, including place cells and vector cells, form compositional state spaces that enable adaptive behavior. The discussion is framed within the context of stress and adaptive decision-making research, highlighting how disruptions in these systems—such as impaired hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony—contribute to maladaptive behaviors in neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. For researchers and drug development professionals, this guide provides a technical overview of core concepts, key experimental paradigms, and essential research tools.

The hippocampus has traditionally been characterized as a critical substrate for long-term declarative memory [16]. However, a growing body of evidence reframes its primary function as the construction and flexible manipulation of relational memory representations [16] [22]. These representations bind the co-occurring people, places, objects, and events of an experience into a durable format that can be searched, reconstructed, and recombined to guide behavior in novel situations [16]. This functionality is fundamental to cognitive flexibility—the adaptive process of generating, updating, and integrating information to respond optimally to changing environmental demands [16].

Within research on stress and adaptive decision-making, the integrity of hippocampal relational memory systems is paramount. Successful decision-making in dynamic, ecologically valid environments depends on the ability to simulate potential outcomes and flexibly apply past learning [23] [24]. The hippocampus is now understood to be central to this process, forming a "cognitive map" that represents not only spatial but also non-spatial relational structures, thereby supporting inference, imagination, and optimal policy selection [22].

Core Mechanisms: How the Hippocampus Supports Flexible Representations

The hippocampus enables cognitive flexibility through two hallmark features: the binding of arbitrary relations between elements of experience, and the flexible, goal-directed expression of these representations [16]. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and underlying mechanisms of relational memory.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Hippocampal Relational Memory

| Characteristic | Functional Description | Proposed Neural Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Arbitrary Associative Binding | Binding distinct, unrelated elements (e.g., a person, a place, an object) into a unified memory trace. | Convergent input from medial temporal lobe cortices into hippocampal CA3 region, enabling synaptic co-activation [16]. |

| Representational Flexibility | The ability to recombine and reconstruct elements of past experiences for use in new contexts. | Pattern completion and separation processes in hippocampal subfields CA3 and CA1, respectively [16] [22]. |

| Compositionality | Constructing novel representations by combining reusable "building blocks" or primitives of knowledge. | Conjunctive coding by hippocampal place cells, binding inputs from entorhinal cortex (e.g., grid cells, vector cells) [22]. |

| Offline (Re)Construction | The offline creation and strengthening of memory representations without direct experience. | Sharp-wave ripples (SWRs) and neural replay during rest/sleep, which consolidate and pre-construct state spaces [23] [22]. |

The Compositional Model: Zero-Shot Generalization

A leading computational model posits that the hippocampus constructs state spaces compositionally from reusable cortical "primitives" [22]. In this framework, cortical regions provide fundamental building blocks—such as grid cells for self-location and vector cells for representing the direction and distance to borders, objects, or rewards. The hippocampus then acts as a compositional engine, binding these primitives together into a conjunctive representation [22].

For example, a hippocampal "landmark-vector cell" might fire at a specific location and direction relative to a salient object, effectively constituting a place cell that also carries relational information about that object [22]. This composition is powerful because it allows for zero-shot generalization. An agent entering a new environment can immediately infer behavioral policies by composing known building blocks in a new configuration, rather than requiring slow, trial-and-error learning [22].

Diagram 1: The Compositional Memory Model. The hippocampus binds cortical primitives to form a flexible relational state space.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Investigating relational memory and cognitive flexibility requires sophisticated behavioral paradigms and neural recording techniques. The following section details key experimental approaches and their findings.

Key Experimental Paradigms and Findings

Table 2: Key Experimental Paradigms in Relational Memory Research

| Paradigm | Core Methodology | Key Quantitative Finding | Implication for Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Foraging Task [24] | Rodents forage in a risk/reward environment with changing threat conditions (e.g., "approach food-avoid predator"). | 5XFAD mice (AD model) show ~40% reduction in adaptive risk adjustment compared to wild-types [24]. | Tests real-world decision-making; links amyloid pathology to behavioral rigidity. |

| fMRI of Episodic Prediction Error [25] | Human subjects undergo fMRI while completing a memory task designed to elicit mismatches between expectation and outcome. | Specific hippocampal and prefrontal subregions show BOLD activation correlating with prediction error strength (p < 0.005, FWE-corrected) [25]. | Memory updating is driven by prediction errors, a key learning signal for flexible behavior. |

| Mood & Destination Memory Task [26] | Human participants under positive, negative, or neutral mood induction perform a task requiring recall of information recipients. | One-way ANOVA showed a significant mood effect: F(2, 57) = 5.25, p = .008, η² = 0.13. Neutral mood led to superior performance vs. positive mood [26]. | Emotional state modulates social memory accuracy, relevant for stress research. |

| Neural Replay Analysis [22] | Recordings of hippocampal CA1 place cells during rest/quiet wakefulness after exposure to a new environment or task. | Replay events at a new landmark induced new remote firing fields; field strength increased with replay prevalence [22]. | Offline replay constructs and strengthens memory representations for future use. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Rodent Spatial Decision-Making

The following workflow visualizes a typical integrated protocol for assessing relational memory and neural dynamics in rodent models, synthesizing methodologies from [24] and [22].

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Assessing Neural Dynamics and Behavior.

Core Methodological Steps:

- Surgical Preparation: Subjects (e.g., C57BL/6 or 5XFAD mice) are implanted with chronic multi-electrode arrays (e.g., 64- or 128-channel silicon probes) targeting the hippocampal CA1 region and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) for simultaneous neural recording [24].

- Behavioral Training & Habituation: Animals are habituated to the testing arena and trained on the core task logic. In the "approach food-avoid predator" paradigm, they learn to forage for food rewards while avoiding zones associated with a predator threat [24].

- Task Execution & Neural Recording: During the task, neural activity (single-unit spikes and local field potentials) and behavioral tracking (via overhead cameras) are recorded simultaneously. The task parameters may be altered (e.g., shifting threat locations) to probe cognitive flexibility [24].

- Post-Task Rest Session: Immediately following the task, neural activity is recorded during a rest or sleep session in a home cage. This data is critical for detecting offline sharp-wave ripples (SWRs) and replay events [22].

- Data Analysis:

- Behavioral: Calculate metrics like percent of risky choices, adjustment to rule shifts, and foraging efficiency.

- Neural: Spike sorting to identify single units. Place field mapping for hippocampal cells. Analysis of SWR rate, content, and prefrontal-hippocampal coherence (e.g., phase-locking value) [24].

- Replay Detection: Identify sequences of place cell activity during SWRs that recapitulate or pre-play behavioral trajectories [22].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Relational Memory

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transgenic Animal Models (e.g., 5XFAD) | Model neurodegenerative pathology (Amyloid-β) to study its impact on hippocampal dynamics and behavior. | Linking amyloidosis to disrupted SWRs, place cell rigidity, and impaired decision-making [24]. |

| Multi-Channel Electrophysiology Probes (e.g., Neuropixels) | High-density recording of single-unit and population activity from multiple brain regions simultaneously. | Recording from hippocampal-prefrontal circuits during behavior to assess synchrony and replay [24]. |

| Chemogenetic/Light-Sensitive Tools (DREADDs, Optogenetics) | Temporally-precise inhibition or excitation of specific neural populations or pathways. | Causally testing the role of CA1 SWRs or CA3 output on memory consolidation and flexibility. |

| Cypher Query Language | A declarative language for querying graph databases, enabling complex relational data analysis. | Modeling and querying complex biological networks (e.g., protein-protein interactions) [27]. |

| Graph Database Systems (e.g., Neo4j) | Specialized databases to store and analyze complex, interconnected data as nodes and relationships. | Managing and analyzing networked neuroscience data, such as functional connectivity maps [27]. |

Implications for Stress and Adaptive Decision-Making Research

Dysfunction in the relational memory network has profound consequences for adaptive behavior, particularly under stress. Chronic stress is known to impair hippocampal function, leading to over-generalization of fear memories and reduced behavioral flexibility. The mechanisms detailed herein provide a scaffold for understanding these effects at a circuit and representational level.

Research in Alzheimer's disease models shows that amyloid pathology disrupts the very dynamics that support flexible representations: it reduces sharp-wave ripple frequency, causes rigid place cell firing patterns, and diminishes hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony [24]. This breakdown in corticolimbic coordination directly correlates with poor performance in ecologically valid decision-making tasks, where 5XFAD mice persist in risky choices despite changing threats [24]. This mirrors real-world cognitive inflexibility in patients.

Furthermore, computational models like "Meta-Dyna" unite hippocampal replay with prefrontal meta-control, suggesting that stress-induced disruption of this loop could impair the ability to simulate and evaluate potential futures, a core deficit in anxiety and PTSD [23]. Therapeutic interventions aimed at enhancing hippocampal plasticity (e.g., through neuromodulation or pharmacological agents that promote SWRs) may therefore restore a degree of cognitive flexibility by targeting these fundamental relational memory processes.

The hippocampus, long recognized for its role in spatial navigation and episodic memory, is now understood to be fundamental in constructing cognitive maps that extend beyond physical space into abstract, state-based representations critical for decision-making. This review synthesizes recent advances revealing how hippocampal neural circuits encode state spaces—internal models of task structure and contingencies—and how this encoding enables adaptive value-based decisions, particularly under stressful conditions. We examine the division of labor within the hippocampal-prefrontal circuit, where the hippocampus represents contextual states and relays this information to the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) to generate state-appropriate value representations. The integration of cognitive map theory with state-space representation provides a powerful framework for understanding how animals and humans navigate multidimensional decision spaces, with significant implications for understanding the neural mechanisms disrupted in stress-related psychiatric disorders and for developing novel therapeutic interventions.

The concept of the cognitive map originated from observations that rats form mental representations of their environment that extend beyond simple stimulus-response associations [28]. Initially applied to physical navigation, this theory has since expanded to encompass nonspatial domains, including value-based decision-making and abstract reasoning. The medial temporal lobe (MTL), particularly the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) have emerged as key nodes in a system that supports cognitive maps for both physical and abstract spaces [28].

Contemporary research suggests the hippocampus functions as a state-space encoder, creating flexible internal representations of task states, rules, and relationships that guide adaptive behavior. This representational capacity enables animals to understand that "what is good in one scenario may be bad in another," forming the computational foundation for context-dependent decision-making [29]. The emerging concept of "decision maps" represents a synthesis of cognitive map theory with value-based choice, positioning the hippocampus as crucial for navigating complex decision spaces where the values of options depend on contextual states.

Neural Mechanisms of State-Space Representation

Hippocampal Encoding of Contextual States

The hippocampus exhibits specialized neural mechanisms for encoding and representing state information:

State Encoding Dynamics: Hippocampal neurons show strong encoding of state information when it first becomes available. In primate studies, HPC neurons were significantly more likely to encode state information during the state cue period compared to OFC neurons (P < 0.001) [29]. This early encoding allows the hippocampus to represent the current contextual framework before decision options are presented.

Population Coding Geometry: When population activity from hippocampal neurons is projected into a low-dimensional space, value representations maintain an isomorphic structure across different task states. However, these representations require only minimal rotation (mean = 34° ± 0.13°) to align across states, suggesting the hippocampus maintains a relatively stable value code that generalizes across contexts [29].

Temporal Dynamics of Information Flow: Hippocampal state encoding predominates during initial state presentation, while OFC state encoding becomes more prominent during the choice epoch, suggesting a serial processing model where contextual information flows from hippocampus to OFC for decision implementation [29].

Hippocampal-Prefrontal Circuitry for State-Dependent Valuation

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) transforms hippocampal state representations into state-appropriate value signals:

State-Dependent Value Coding: Unlike hippocampal neurons that maintain consistent value coding across states, OFC neurons exhibit state-dependent value representations. Many OFC neurons uniquely encode value in only one state but not the other, with value manifolds requiring near-orthogonal rotations (mean = 77° ± 0.15°) to align across states [29].

Functional Dissociation: This suggests a specialized division of labor where the hippocampus encodes contextual information that is then broadcast to the OFC to select state-appropriate value subcircuits [29].

Cross-State Decoding Limitations: Decoders trained to identify values in one state show significantly reduced performance when applied to the alternative state, confirming the state-specific nature of OFC value representations [29].

Theta Synchronization as a Communication Mechanism

Hippocampal-prefrontal communication occurs through synchronized neural oscillations:

Theta Band Coordination: Theta oscillations (4-8 Hz) dominate both HPC and OFC activity during decision-making tasks and serve as a mechanism for information transfer between these regions [29].

Information Relay: Theta synchronization enables the hippocampus to relay state information to the OFC during the choice period, allowing contextual information to shape value representations precisely when needed for decision formation [29].

Table 1: Neural Signatures of State-Space Representation Across Brain Regions

| Brain Region | State Encoding Dynamics | Value Coding Properties | Representational Geometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus (HPC) | Strong during state cue period; encodes context as it becomes available | Stable across states; maintains consistent value coding | Isomorphic across states; requires minimal rotation (34°) for alignment |

| Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) | Strong during choice period; uses state to guide decisions | State-dependent; different neurons active in different states | Orthogonal across states; requires substantial rotation (77°) for alignment |

| Hippocampal-OFC Circuit | Serial processing: HPC → OFC via theta synchronization | Transformation of state information to state-appropriate values | Enables flexible context-value associations |

Experimental Evidence and Protocols

Primate State-Dependent Decision Task

Experimental Objective: To investigate how neural circuits support state-dependent value-based decisions and identify the respective contributions of hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex.

Subjects: Two monkeys (Subjects K and D) trained on a state-dependent choice task [29].

Task Structure:

- State Cue: Monkeys were cued whether the trial should be evaluated according to value scheme A or B.

- Delay Period: Brief interval between state cue and option presentation.

- Choice Period: Presentation of either one (forced choice, 20% of trials) or two options (free choice, 80% of trials).

- Critical Manipulation: Picture values depended on the cued task state, requiring flexible updating of option values based on context.

Behavioral Results: Both subjects achieved high accuracy (Subject K: 98% correct; Subject D: 94% correct on average) with no significant difference between states, demonstrating successful task mastery. Decision times decreased with larger value differences between options (Subject K: β = -5.5, P < 0.001; Subject D: β = -4.9, P < 0.001), indicating sensitivity to decision variables [29].

Neural Recording Protocol:

- Simultaneous recordings from HPC (Subject K: 179 neurons; Subject D: 125 neurons) and OFC (Subject K: 251 neurons; Subject D: 281 neurons).

- Sliding-window ANOVA to assess state tuning across trial epochs.

- Regression analysis to quantify value coding with predictors for state, value, and their interaction.

- Population analysis using dimensionality reduction to examine representational geometry.

- Theta oscillation analysis through power spectrum density and coherence measurements.

Experimental Objective: To identify brain regions involved in constructing cognitive maps for multidimensional abstract spaces and determine how the hippocampus and OFC collaborate during learning [28].

Subjects: 27 healthy adults (14 women) performing navigation tasks in abstract spaces.

Abstract Space Construction:

- Spaces of varying dimensionality (1D, 2D, 3D) created using modified features of basic symbols.

- Five different abstract spaces with counterbalanced symbol assignment.

- Subjects navigated from starting point to destination by selecting adjacent points in the abstract space.

fMRI Protocol:

- Acquisition parameters: Whole-brain coverage, TE = 30 ms, TR = 2 s, flip-angle = 65°, resolution 3×3×3 mm.

- pRF mapping with bar aperture traversing visual field while revealing scene fragments.

- Six category localizer runs (scenes, faces, bodies, buildings, objects, scrambled objects).

- Learning stage classification using deep neural network to estimate learning level and k-means clustering to separate exploration and exploitation stages.

Key Findings:

- Exploration Phase: Higher activation in bilateral hippocampus and lateral PFC, positively correlated with learning level and accuracy.

- Exploitation Phase: Higher activation in bilateral OFC and retrosplenial cortex, negatively correlated with learning level and accuracy.

- Representational Similarity: Hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and OFC more accurately represented destinations during exploitation than exploration [28].

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Paradigms in State-Space Research

| Study Type | Subjects | Key Manipulations | Measurement Techniques | Principal Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primate Neurophysiology [29] | 2 monkeys | State-dependent value mappings; free vs. forced choice | Single-unit recording in HPC and OFC; LFP for oscillations | HPC encodes state early; OFC encodes state-dependent values; communication via theta synchronization |

| Human fMRI Abstract Navigation [28] | 27 humans | Multidimensional abstract spaces (1D-3D); exploration vs. exploitation | fMRI; pRF mapping; representational similarity analysis | Hippocampus active during exploration; OFC during exploitation; collaborative learning |

| Rodent Spatial Decision-Making [30] | Rats | Navigational decisions in mazes; vicarious trial and error behavior | Single-unit recording; theta and SWR analysis | Hippocampal replay at decision points; theta sequences during deliberation |

Computational Framework: State-Space Representations

State-space models provide a mathematical framework for understanding how the brain might represent and update internal models of task states:

Basic State-Space Formulation

In control engineering and systems neuroscience, state-space representations describe how system states evolve over time and how observations relate to these hidden states [31]. The fundamental equations are:

State Equation:

x_{t+1} = A x_t + C w_{t+1}

Observation Equation:

y_t = G x_t

Where:

x_trepresents the hidden state vector at timety_trepresents observationsAis the state transition matrixCis the volatility matrixGis the output matrixw_tis system noise [32]