Beyond Pairwise: How Higher-Order Interactions Are Reshaping Network Science and Drug Discovery

This article explores the critical shift in complex systems analysis from traditional pairwise connectivity to the incorporation of higher-order interactions (HOIs).

Beyond Pairwise: How Higher-Order Interactions Are Reshaping Network Science and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical shift in complex systems analysis from traditional pairwise connectivity to the incorporation of higher-order interactions (HOIs). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts, methodological advances, and practical applications. We examine how HOIs, which involve three or more components simultaneously, reveal emergent system properties that are invisible to pairwise models. The content covers cutting-edge discovery techniques, addresses the challenges of combinatorial complexity, and presents rigorous validation studies. Through comparative analysis, we demonstrate the superior performance of HOI-aware models in tasks like drug-side effect prediction and brain connectome mapping, arguing for their necessity in accurately modeling and intervening in complex biological and clinical systems.

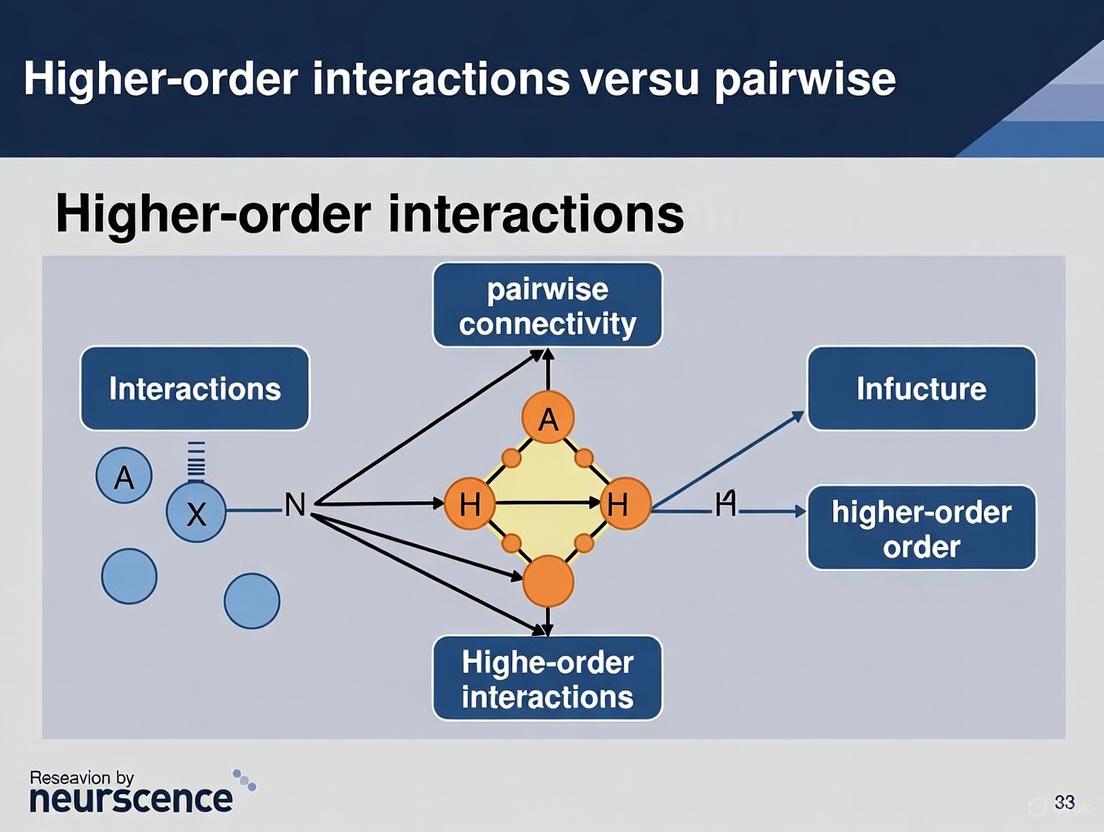

Unveiling a New Dimension: From Pairwise Links to Higher-Order Structures

In the study of complex systems, from neural networks in the brain to the efficacy of drug combinations, the traditional focus has been on pairwise interactions. This approach models relationships between two elements at a time, forming the basis of classical network science. However, a paradigm shift is underway, driven by the growing recognition that many system behaviors cannot be fully explained by these dyadic connections alone. Higher-order interactions (HOIs)—simultaneous interactions among three or more elements—are now understood to be critical for generating synergistic effects and emergent properties that are irreducible to any pair of components [1] [2].

This guide objectively compares the performance of research frameworks based on higher-order interactions against those limited to pairwise connectivity. We present quantitative evidence from neuroscience and drug discovery, detailing experimental protocols and providing a structured toolkit for researchers aiming to implement these advanced analytical approaches. The consistent finding across fields is that higher-order models provide a more comprehensive, accurate, and biologically plausible understanding of system dynamics, leading to tangible improvements in task decoding, individual identification, behavior prediction, and therapeutic discovery [2] [3].

Comparative Performance: Higher-Order vs. Pairwise Frameworks

Performance in Neural Decoding and Brain Function

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies that directly compare higher-order and pairwise interaction models.

Table 1: Comparison of HOI and Pairwise Models in fMRI Brain Analysis

| Analysis Task | Higher-Order Model Performance | Pairwise Model Performance | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Decoding | Superior identification of task/rest blocks using local topological indicators from simplicial complexes [2]. | Lower performance in dynamic task identification using traditional edge-centric methods [2]. | HCP fMRI (100 subjects) [2] |

| Individual Identification | Improved functional "fingerprinting" based on local topological structures of unimodal/transmodal subsystems [2]. | Less effective individual identification compared to higher-order approaches [2]. | HCP fMRI (100 subjects) [2] |

| Brain-Behavior Association | Significantly stronger association between brain activity and behavior [2]. | Weaker association with behavioral measures [2]. | HCP fMRI (100 subjects) [2] |

| Information Encoding | Information gain encoded synergistically at the level of triplets and quadruplets; long-range interactions centered on vmPFC/OFC [4]. | Limited capacity to capture complex, multi-element information encoding [4]. | MEG during goal-directed learning [4] |

Performance in Drug Synergy Prediction

In pharmacological research, higher-order models that integrate multiple data types significantly improve the prediction of synergistic drug combinations.

Table 2: Comparison of HOI and Pairwise Models in Drug Synergy Prediction

| Model Feature | Higher-Order Model Approach | Pairwise/Low-Order Model Approach | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Integration | Integration of Drug Resistance Signatures (DRS) capturing transcriptomic changes [3]. | Reliance on chemical structures or general drug-induced transcriptional responses [3]. | DRS-based models consistently outperform traditional approaches across multiple ML algorithms [3]. |

| Interaction Modeling | Hypergraph-based models (e.g., HGCNDR) explicitly model high-order interactions among drugs and diseases [5]. | Graph models capturing only pairwise drug-disease or drug-drug relationships [5]. | Improved prediction accuracy and retrieval of actual drug-disease associations [5]. |

| Model Architecture | Multimodal feature fusion (e.g., MFFDTA) integrates diverse data types (structure, expression, knowledge) [6]. | Unimodal inputs (e.g., molecular fingerprints or protein descriptors alone) [6]. | Superior generalizability and robustness, particularly in low-resource or noisy data settings [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Higher-Order Interactions

Protocol 1: Temporal Higher-Order Topological Analysis of fMRI Data

This protocol, detailed in [2], infers instantaneous higher-order patterns from fMRI time series to study brain function.

- Step 1: Signal Standardization: Begin by z-scoring the N original fMRI signals from parcellated brain regions (e.g., N=119 regions from the HCP atlas) to ensure comparability [2].

- Step 2: k-Order Time Series Calculation: For all possible (k+1)-node combinations, compute a k-order time series as the element-wise product of the (k+1) z-scored signals. For example, a 2-order time series (representing a 3-node interaction) is the product of three z-scored regional signals. The resulting time series is also z-scored. A sign is assigned at each timepoint: positive for fully concordant interactions (all node signals are positive or negative), and negative for discordant interactions [2].

- Step 3: Construct Weighted Simplicial Complexes: At each timepoint t, encode all k-order time series into a weighted simplicial complex. In this complex, nodes are brain regions, edges represent pairwise interactions, triangles represent 3-way interactions, and so on. The weight of each simplex (e.g., a triangle) is the value of its corresponding k-order time series at time t [2].

- Step 4: Topological Indicator Extraction: Apply computational topology tools to each simplicial complex to extract relevant indicators. Key indicators include:

- Violating Triangles: Triplets of nodes where the strength of the 3-way interaction (triangle weight) is greater than the strengths of the three corresponding pairwise interactions (edge weights). This identifies interactions that are irreducible to pairwise relationships [2].

- Homological Scaffold: A weighted graph that highlights the importance of edges in forming mesoscopic topological structures, such as 1-dimensional cycles, within the higher-order co-fluctuation landscape [2].

- Step 5: Performance Benchmarking: Use the extracted indicators as features for tasks such as dynamic task decoding (using recurrence plots and community detection) and individual identification. Compare their performance against features derived from raw BOLD signals and pairwise edge time series [2].

Protocol 2: Information Dynamics Analysis with MEG

This protocol uses Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and information theory to quantify how synergistic interactions encode learning signals [4].

- Step 1: Experimental Task Design: Implement a goal-directed learning task where participants discover stimulus-response associations through exploration. The design should control the exploratory phase to ensure reproducible behaviors across subjects and sessions. For example, correct responses can be defined only after a specific number of incorrect attempts for different stimuli [4].

- Step 2: Behavioral Modeling and Signal Extraction: Fit a computational model (e.g., a Q-learning model) to the behavioral data to estimate trial-by-trial learning signals. Key signals include:

- Reward Prediction Error (RPE): The difference between received and expected outcomes.

- Information Gain (IG): The reduction in uncertainty about action-outcome relationships, quantified as the distance between probability distributions of actions before and after an outcome [4].

- Step 3: Neural Data Acquisition and Processing: Record neural activity using MEG during the task. Process the data to source-localized High-Gamma Activity (HGA, 60-120 Hz), which is a robust correlate of local cortical firing. Extract time series from regions of interest within the goal-directed learning circuit (e.g., visual, parietal, lateral prefrontal, and ventromedial/orbital prefrontal cortices) [4].

- Step 4: Partial Information Decomposition (PID): Apply PID to the neural time series. PID decomposes the total information that a set of source variables (e.g., neural signals from multiple regions) provides about a target variable (e.g., Information Gain) into four components:

- Unique Information from each source.

- Redundant Information shared by multiple sources.

- Synergistic Information that is only available from the joint state of multiple sources together [4].

- Step 5: Characterize Synergistic Interactions: Identify the brain regions participating in significant synergistic interactions and determine their order (e.g., triplets, quadruplets). Analyze the role of these synergistic networks in broadcasting information across the cortex, with particular attention to hubs like the ventromedial and orbitofrontal cortices, which often act as key receivers [4].

Protocol 3: Drug Synergy Prediction with Resistance Signatures

This protocol leverages higher-order data integration to predict synergistic anti-cancer drug combinations [3].

- Step 1: Data Compilation from Public Databases:

- Drug Combination Data: Obtain large-scale drug synergy screening data (e.g., from DrugComb, O'Neil, or ALMANAC databases), which include synergy scores (e.g., S-score) for numerous drug pairs across multiple cancer cell lines [3].

- Transcriptomic Data: Acquire drug-induced gene expression profiles from the LINCS database. A common condition is 24-hour treatment with a 10 μM drug concentration [3].

- Drug Sensitivity Data: Gather drug response metrics, such as IC50 values (concentration that inhibits 50% of growth), for a wide array of cancer cell lines from databases like the GDSC [3].

- Step 2: Feature Engineering - Drug Resistance Signatures (DRS):

- For each drug, classify cell lines from the GDSC as "sensitive" or "resistant" based on whether their IC50 value is below or above the median IC50 across all cell lines [3].

- Perform differential gene expression analysis to compare the LINCS transcriptomic profiles of sensitive versus resistant cell lines for the same drug. The resulting differential expression scores constitute the DRS, which captures transcriptional adaptations associated with drug resistance [3].

- Step 3: Model Training and Comparison:

- Train a suite of machine learning and deep learning models (e.g., LASSO, Random Forest, XGBoost, SynergyX) to predict synergy scores.

- Experimental Group: Use the DRS features, combined with cell line genomic features, as input.

- Control Group: Use conventional drug descriptors (e.g., chemical fingerprints) and the same cell line features as input [3].

- Step 4: Validation and Interpretation:

- Validate all models rigorously on independent, held-out test sets from different databases (e.g., train on DrugComb, test on O'Neil) to assess generalizability.

- Compare the predictive performance (e.g., using metrics like RMSE, AUC-ROC) between the DRS-based models and the conventional models. Perform ablation studies to confirm the contribution of the DRS features [3].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Higher-Order Interaction Studies

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Dataset | Neuroimaging Data | Provides high-quality, multimodal fMRI data from a large cohort of healthy adults for benchmarking analytical methods [2]. | Human Brain Function |

| NeuroMark_fMRI Template | Software/Atlas | A multiscale brain network template with 105 intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs) derived from over 100K subjects, enabling consistent parcellation for fMRI analysis [7]. | Human Brain Function |

| LINCS / GDSC Databases | Pharmaco-genomic Database | LINCS provides drug-induced gene expression profiles; GDSC provides drug sensitivity data (IC50). Together, they enable the calculation of Drug Resistance Signatures (DRS) [3]. | Drug Discovery |

| DrugComb / ALMANAC | Drug Synergy Database | Curated repositories of experimentally measured synergistic interactions between drug pairs across numerous cell lines, used for model training and validation [3]. | Drug Discovery |

| Partial Information Decomposition (PID) | Computational Framework | Decomposes multivariate information into unique, redundant, and synergistic components, allowing quantification of higher-order information sharing [4]. | Information Theory, Neuroscience |

| Simplicial Complexes & Persistent Homology | Mathematical Framework | Represents and quantifies higher-order structures (e.g., triangles, tetrahedra) in data, allowing for topological analysis beyond pairwise graphs [1] [2]. | Topological Data Analysis |

| Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNN) | Algorithm/Model | A class of neural networks designed to process data structured as hypergraphs, explicitly modeling relationships involving any number of nodes [5]. | Drug Repositioning, Network Science |

The experimental data and comparative analyses presented in this guide lead to a consistent and compelling conclusion: frameworks that incorporate higher-order interactions consistently outperform those restricted to pairwise connectivity across multiple domains. In neuroscience, HOIs provide a more nuanced and powerful lens for understanding brain function, significantly enhancing task decoding, individual identification, and the correlation of brain activity with behavior [2]. In drug discovery, models that embrace higher-order biological data, such as drug resistance signatures and hypergraph-based relationships, demonstrate superior accuracy and generalizability in predicting synergistic therapeutic combinations [3] [5].

The methodological shift from pairwise to higher-order analysis is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental advancement in how we represent and understand complexity. It allows researchers to capture the synergistic and emergent properties that are defining features of sophisticated biological and pharmacological systems. As the tools and protocols outlined in this guide become more accessible, their widespread adoption promises to accelerate progress in unraveling the complexities of the brain and developing more effective, multi-targeted therapies for complex diseases.

Network science has long relied on pairwise connectivity to model complex systems, from neural circuits in the brain to combination therapies in pharmacology. This approach represents systems as graphs where nodes represent components and edges represent pairwise relationships. However, mounting evidence reveals that higher-order interactions (HOIs)—simultaneous interactions among three or more components—play critical roles that pairwise models cannot capture. This guide compares the descriptive and predictive performance of pairwise versus higher-order frameworks across biological domains. We demonstrate through experimental data that higher-order approaches consistently outperform pairwise models in detecting system dynamics, predicting emergent behaviors, and identifying robust biomarkers—revealing a vast space of hidden structures in complex systems.

Traditional network models provide a powerful but limited framework for complex systems analysis. By representing systems as graphs with pairwise edges, these models inherently assume that all interactions can be decomposed into binary relationships. This simplification has facilitated the application of graph theory to diverse fields but fails to capture the multivariate dependencies that arise when three or more components interact simultaneously. In neuroscience, pairwise functional connectivity quantifies correlations between brain regions but misses synergistic information sharing across distributed networks. In pharmacology, pairwise drug interaction models cannot predict emergent effects that only manifest when three or more drugs are combined. The combinatorial complexity of measuring all possible higher-order interactions has historically constrained their systematic study, but recent methodological advances now enable researchers to move beyond the pairwise paradigm and uncover these hidden interaction layers.

Performance Comparison: Pairwise vs. Higher-Order Approaches

Quantitative Evidence from Neuroscience and Pharmacology

Table 1: Performance Metrics in Brain Network Analysis

| Metric | Pairwise Approach | Higher-Order Approach | Improvement | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task decoding accuracy | 0.47 (Element-centric similarity) | 0.72 (Element-centric similarity) | +53% | fMRI task classification [2] |

| Individual identification | Moderate | Substantial improvement | Not quantified | Functional brain fingerprinting [2] |

| Brain-behavior association | Weaker | Significantly stronger | Not quantified | Resting-state fMRI [2] |

| Redundancy detection | Effective | Comparable | Similar performance | Functional connectivity [8] |

| Synergy detection | Cannot detect | Effective identification | Fundamental capability | Multivariate information [8] |

Table 2: Drug Interaction Patterns Across Orders

| Interaction Order | Number of Combinations | Net Synergy Frequency | Emergent Antagonism | Study System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-way | 251 | Lower | Less frequent | Pathogenic E. coli [9] |

| 3-way | 1,512 | Increasing | More frequent | Pathogenic E. coli [9] |

| 4-way | 5,670 | Higher | Even more frequent | Pathogenic E. coli [9] |

| 5-way | 13,608 | Highest | Most frequent | Pathogenic E. coli [9] |

Key Performance Insights

Detection of Emergent Properties: Higher-order approaches uniquely detect synergistic information—multivariate dependencies where information is shared collectively but not present in any subset [8]. Pairwise methods systematically miss these phenomena.

Scalability of Interactions: The frequency and strength of interactions increase with system complexity. In pharmacology, higher-order drug combinations show elevated frequencies of both net synergy and emergent antagonism as more drugs are added [9].

Domain-Specific Advantages: In neuroscience, higher-order methods significantly improve task decoding accuracy (from 0.47 to 0.72 element-centric similarity) and strengthen brain-behavior associations compared to pairwise connectivity [2].

Experimental Protocols for Higher-Order Analysis

Protocol 1: Topological Analysis of fMRI Data

This protocol enables reconstruction of higher-order interactions from brain activity signals [2]:

Signal Standardization: Z-score all original fMRI signals from N brain regions to normalize activity time series.

K-Order Time Series Computation: Calculate all possible k-order time series as element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series. For example, a 2-order time series represents triple interactions (triangles) rather than pairwise edges.

Sign Assignment: Assign positive signs to fully concordant group interactions (all time series have same-sign values) and negative signs to discordant interactions (mixed signs) at each timepoint.

Simplicial Complex Encoding: Encode all instantaneous k-order time series into a weighted simplicial complex—a mathematical object that generalizes graphs to include higher-dimensional relationships.

Topological Indicator Extraction: Apply computational topology tools to extract local and global higher-order indicators, including:

- Violating triangles: Triplets that co-fluctuate more than expected from pairwise edges

- Homological scaffolds: Weighted graphs highlighting edge importance in mesoscopic topological structures

- Hyper-coherence: Global measure of higher-order triplet co-fluctuation

Protocol 2: Higher-Order Drug Interaction Screening

This full-factorial protocol quantifies net and emergent interactions in multi-drug combinations [9]:

Experimental Design: Implement full-factorial combination screening across all drug orders (single drugs to N-way combinations) with appropriate concentration ranges.

Fitness Measurement: Quantify relative fitness (w) for each drug combination, typically measured as bacterial growth rate inhibition for antibiotic studies. Values range from 0 (no growth, complete lethality) to 1 (maximum growth, no effect).

Null Model Specification: Define non-interacting expectation using Bliss Independence: for a combination D, the expected fitness without interaction is the product of individual drug fitness values.

Net Interaction Calculation: Compute net N-way interaction (N~N~) as the deviation from Bliss Independence: N~N~ = w~X1X2...XN~ - w~X1~w~X2~...w~XN~

Emergent Interaction Quantification: Calculate emergent N-way interaction (E~N~) by subtracting all lower-order interaction effects from the net interaction, isolating effects that require all N components to be present.

Interaction Classification: Classify combinations as:

- Synergistic: Significant negative deviation (greater inhibition than expected)

- Antagonistic: Significant positive deviation (less inhibition than expected)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Higher-Order Interaction Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Reagents | Function in Research | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python with NetworkX, Topological Data Analysis libraries | Simplicial complex construction, higher-order metric calculation | Neuroscience, General Systems [2] |

| Information Theory Metrics | O-information (OI), Mutual Information (MI), Multi-information | Quantifying redundancy/synergy dominance in multivariate systems | Brain Connectivity [8] |

| Experimental Platforms | High-throughput screening systems, Automated liquid handling | Full-factorial combination testing across multiple concentrations | Pharmacology [9] |

| Neuroimaging Data | Human Connectome Project (HCP) datasets, Resting-state fMRI | Benchmark data for higher-order method validation | Neuroscience [2] |

| Biological Model Systems | Pathogenic E. coli strains, Bacterial growth assay kits | Controlled system for drug interaction studies | Pharmacology [9] |

| Validation Frameworks | Surrogate data analysis, Bootstrap confidence intervals | Statistical significance testing for individual subject analysis | Clinical Applications [8] |

The evidence across domains clearly demonstrates that pairwise connectivity provides an incomplete picture of complex system organization. Higher-order approaches reveal hidden patterns that enhance task decoding in neuroscience, predict emergent effects in pharmacology, and provide more robust biomarkers for clinical applications. While pairwise methods remain valuable for initial network characterization and benefit from computational efficiency, researchers studying multivariate systems should integrate higher-order analyses to capture the full complexity of their systems. Future methodological developments should focus on overcoming the combinatorial challenges of higher-order measurement and creating unified frameworks that bridge pairwise and higher-order perspectives across biological scales.

Complex systems in fields ranging from neuroscience to drug development are fundamentally shaped by interactions that involve more than two entities simultaneously. Traditional network science, built upon pairwise connections, often fails to capture these higher-order interactions [10]. Two primary mathematical frameworks have emerged to model these complex relationships: hypergraphs and simplicial complexes [11]. While both generalize simple graphs, they possess distinct mathematical properties that influence their application in scientific research. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these frameworks, their mathematical foundations, and their differential impact on predicting system behavior, with particular relevance to research professionals investigating complex biological systems and drug interactions.

Foundational Definitions and Key Differences

What is a Hypergraph?

A hypergraph ( HG = (V, H) ) is defined by a finite set of vertices ( V ) and a set of hyperedges ( H ), where each hyperedge is a non-empty subset of ( V ) [10]. The striking feature of hypergraphs is that hyperedges can connect any number of nodes, enabling them to capture multi-way relationships natively without imposing additional structural constraints.

Example: In a scientific collaboration network, a single hyperedge can link all co-authors of a paper, directly representing the collaborative group without ambiguity.

What is a Simplicial Complex?

A simplicial complex ( K ) on a base set ( X ) is a collection of nonempty subsets of ( X ) (called simplices) with the property that if ( \sigma \in K ) and ( \tau \subset \sigma ), then ( \tau \in K ) [12]. This closure property under subsets is the defining characteristic that distinguishes simplicial complexes from general hypergraphs.

Example: If researchers A, B, and C publish a paper together, a simplicial complex representation would include not only the 2-simplex {A,B,C} but also all its subsets: the 1-simplices {A,B}, {A,C}, {B,C}, and the 0-simplices {A}, {B}, {C}.

Comparative Structural Properties

Table 1: Fundamental structural differences between hypergraphs and simplicial complexes

| Feature | Hypergraph | Simplicial Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Element | Hyperedge | Simplex |

| Subset Closure | Not required | Required (if σ ∈ K, τ ⊂ σ, then τ ∈ K) |

| Mathematical Flexibility | High (arbitrary edge sizes) | Constrained (by closure property) |

| Dimensionality | Variable per hyperedge | Determined by maximal simplex |

| Representation Power | Direct multi-way relations | Implied lower-order relations |

Mathematical Foundations and Algebraic Topology

Homology Theories for Hypergraphs

Unlike simplicial complexes, which have a canonical homology theory, multiple approaches exist for defining homology on hypergraphs by constructing auxiliary structures [12]. The survey by Gasparovic et al. describes nine different homology theories for hypergraphs, falling into three main categories:

- Simplicial Complex-Based Homologies: Transform the hypergraph into a simplicial complex, then compute simplicial homology. Examples include the inclusion complex and edge intersection complex.

- Relative Homologies: Compute homology relative to specially constructed subcomplexes.

- Chain Complex Homologies: Define chain complexes directly on the hypergraph structure without intermediate transformation.

Each theory captures different aspects of hypergraph structure, with no single approach being universally canonical [12].

Kernel Methods and Machine Learning

Graph kernels provide one approach to measuring similarity between graphs for pattern recognition and machine learning tasks. Recent work has extended these methods to hypergraphs through the lens of simplicial complexes [10]. The proposed hypergraph kernels exploit the multi-scale organization of complex networks, demonstrating competitive performance against state-of-the-art graph kernels on benchmark datasets and showing particular effectiveness in biological case studies like metabolic pathway classification [10].

Figure 1: Workflow for applying kernel methods to hypergraphs via simplicial complexes

Experimental Comparisons and Collective Dynamics

Synchronization Dynamics: A Case Study

A seminal study published in Nature Communications directly compared the impact of higher-order interactions on synchronization dynamics in hypergraphs versus simplicial complexes [11]. The researchers examined a system of identical phase oscillators with interactions up to order two (three-body interactions), using a generalized Kuramoto model.

Experimental Protocol:

- System: ( n ) identical phase oscillators with states ( \theta = (\theta1, \cdots, \thetan) )

- Dynamics: ( \dot{\theta}i = \omega + \frac{\gamma1}{\langle k^{(1)}\rangle} \sum{j=1}^n A{ij} \sin (\thetaj - \thetai) + \frac{\gamma2}{\langle k^{(2)}\rangle} \sum{j,k=1}^n \frac{1}{2} B{ijk} \frac{1}{2} \sin (\thetaj + \thetak - 2\thetai) )

- Coupling Strengths: ( \gamma1 = 1 - \alpha ), ( \gamma2 = \alpha ), with ( \alpha \in [0,1] ) controlling relative strength

- Stability Analysis: Linearization around synchronous state using multiorder Laplacian

Table 2: Synchronization stability results for different higher-order structures

| Structure Type | Higher-Order Interaction Effect | Key Influencing Factor | Theoretical Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplicial Complexes | Destabilizes synchronization | Higher-order degree heterogeneity | "Rich-get-richer" effect amplifies imbalances |

| Random Hypergraphs | Enhances synchronization | More homogeneous degree distribution | Enables simultaneous information exchange |

| Semi-Structured Hypergraphs | Generally enhances synchronization | Cross-order degree correlations | Balanced interaction patterns |

The findings revealed that higher-order interactions consistently destabilize synchronization in simplicial complexes but typically enhance synchronization in random hypergraphs [11]. This striking difference was attributed to the distinct higher-order degree heterogeneities produced by the two representations, with simplicial complexes exhibiting a "rich-get-richer" effect that amplifies dynamical instabilities.

Link Prediction Performance

Another experimental comparison examined higher-order link prediction capabilities in simplicial networks versus traditional approaches [13]. The Simplicial Motif Predictor Method (SMPM) introduced the concept of "simplicial motifs" as local topological patterns for predicting complex connections.

Experimental Protocol:

- Datasets: Ten temporal simplicial networks from diverse fields

- Method Definition: 16 possible simplicial motifs for ( m \in {3,4} ) nodes

- Classifier: Logistic regression with motif counts as predictors

- Comparison: Against traditional similarity-based metrics and other supervised methods

The results demonstrated that SMPM achieved superior performance in 7 out of 10 datasets compared to traditional approaches, with performance positively correlated with motif richness and richness distribution divergence [13].

Figure 2: Example simplicial motifs used for link prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential analytical tools for higher-order network research

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Framework Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| Multiorder Laplacian | Linear stability analysis of synchronized states | Both (with appropriate formulations) |

| Simplicial Motif Counters | Quantifying local structural patterns | Primarily simplicial complexes |

| Hypergraph Kernels | Similarity measurement for machine learning | Primarily hypergraphs |

| Persistent Homology Pipelines | Computing multiscale topological features | Both (via appropriate constructions) |

| Higher-order Link Predictors | Forecasting complex connections | Both (method-dependent performance) |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The choice between hypergraphs and simplicial complexes has profound implications for modeling biological systems in drug development:

Protein Interaction Networks: Hypergraphs can natively represent protein complexes without artificially decomposing them into pairwise interactions [10] [12].

Drug Synergy Prediction: Simplicial complexes naturally model how drug combinations interact with protein targets, capturing the closure property where lower-order interactions imply higher-order compatibility.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis: Hypergraph kernels show promise for classifying metabolic pathways, outperforming state-of-the-art graph kernels in experimental evaluations [10].

The representation-dependent effects on collective dynamics highlighted by synchronization studies [11] suggest that drug developers should carefully select their modeling framework based on whether they expect higher-order interactions to enhance or suppress coordinated activity in biological systems.

Hypergraphs and simplicial complexes offer complementary approaches to modeling higher-order interactions, each with distinct mathematical foundations and practical implications. Hypergraphs provide flexibility for representing arbitrary multi-way relations, while simplicial complexes offer rich mathematical structure through their closure properties. Experimental evidence demonstrates that the choice between these representations can fundamentally alter predictions about system behavior, particularly for dynamical processes like synchronization. For researchers in drug development and systems biology, selecting the appropriate framework requires careful consideration of both the biological context and the specific analytical questions being pursued.

For decades, the scientific study of complex systems—from neural circuits to ecosystems and pharmacological networks—has been dominated by pairwise interaction models. These models simplify systems into networks of binary connections, fundamentally assuming that the interaction between any two components can be understood in isolation. While this approach has yielded significant insights, it inherently fails to capture the simultaneous influence that multiple components exert upon one another, a phenomenon now recognized as a higher-order interaction (HOI). The limitation of pairwise models is not merely theoretical; it has practical consequences for our ability to predict, manipulate, and understand the behavior of complex systems. This guide synthesizes cutting-edge evidence from neuroscience, ecology, and pharmacology to objectively compare the performance of higher-order interaction frameworks against traditional pairwise models. The consistent finding across these diverse fields is that HOI-based analyses provide a deeper explanatory power and superior predictive accuracy, revealing a layer of complexity that pairwise connectivity routinely misses.

Higher-Order Interactions in Neuroscience

Empirical Evidence and Comparative Data

The human brain represents one of the most complex systems known to science. Traditional functional connectivity models, based on pairwise correlations of fMRI time-series, have provided a foundational but incomplete map of brain network dynamics. Recent research leveraging higher-order topological analysis has demonstrated a clear advantage over these traditional methods.

A comprehensive study using fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project revealed that local higher-order indicators, particularly those capturing triple-interactions (3-way), significantly outperformed traditional node and edge-based methods in several critical tasks. The following table summarizes the performance comparison in task decoding, a key benchmark for functional brain analysis [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Brain Network Analysis Methods in Task Decoding

| Method | Basis of Analysis | Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOLD Signals | Single-region activity | 0.24 | Baseline measure of local activity |

| Edge Time-Series | Pairwise correlations | 0.31 | Captures direct pairwise connectivity |

| Violating Triangles (Δv) | 3-way coherent co-fluctuations | 0.42 | Identifies interactions beyond pairwise capacity |

| Homological Scaffolds | Mesoscopic topological structures | 0.45 | Highlights importance of connections for overall topology |

This data indicates that methods capturing higher-order interactions (triangles and scaffolds) provide a nearly 50% improvement in task identification accuracy compared to traditional BOLD signal analysis. The "violating triangles" metric is particularly telling, as it identifies triplets of brain regions that co-fluctuate more strongly than what would be expected from their pairwise connections alone, directly evidencing HOIs [2].

Another brain-wide analysis in mice recorded from over 50,000 neurons and used machine learning to relate neural activity to ongoing movements. While movement-related activity was widespread, the study found fine-scale structure in how this activity was encoded, with the strength of movement-related signals differing systematically across brain areas and their subdomains. This structured encoding across and within areas points to a complex, higher-order organization of motor commands that cannot be fully described by simple pairwise connections between regions [14].

Experimental Protocols for Neuroscientific HOI Analysis

Protocol: Temporal Higher-Order Topological Analysis (fMRI)

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Collect resting-state or task-fMRI data. Standardize the N original fMRI signals (BOLD time-series) from parcellated brain regions through z-scoring [2].

- Construct k-Order Time Series: Compute all possible k-order time series as the element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series. For example, a triangle (2-order) time series for regions A, B, and C is calculated as

TS_ABC = z(A) * z(B) * z(C)at each time point, followed by re-z-scoring. A sign is assigned at each time point based on the concordance of the original signals [2]. - Build Simplicial Complexes: For each time point t, encode all instantaneous k-order time series into a weighted simplicial complex. In this complex, nodes are brain regions, edges represent pairwise interactions, and triangles (or higher-dimensional simplices) represent 3-way interactions. The weight of each simplex is the value of its corresponding k-order time series at time t [2].

- Topological Indicator Extraction: Apply computational topology tools (e.g., persistent homology) to the weighted simplicial complexes to extract relevant indicators. Key local indicators for HOIs include:

- Violating Triangles (Δv): Triangles whose weight is greater than the weights of their constituent edges, indicating a higher-order interaction that cannot be explained pairwise [2].

- Homological Scaffold: A weighted graph that highlights the importance of edges for the formation of mesoscopic topological structures (like 1-cycles) within the higher-order co-fluctuation landscape [2].

- Validation & Benchmarking: Use extracted indicators as features in machine learning tasks (e.g., task decoding, individual identification) and benchmark their performance against traditional pairwise and node-based features [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Neuroscience HOI Research

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Neuroscientific HOI Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Neural Probes | Enable simultaneous recording from thousands of neurons across multiple brain regions. | Brain-wide analysis of movement encoding in mice [14]. |

| fMRI Scanner | Non-invasively measures Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signals from the entire brain. | Mapping large-scale functional networks in humans [2]. |

| Topological Data Analysis Software | Software libraries for constructing and analyzing simplicial complexes and calculating persistent homology. | Extracting higher-order indicators like violating triangles from fMRI data [2]. |

| DeepLabCut | Markerless pose estimation software for tracking animal behavior from video. | Relating high-dimensional orofacial and paw movements to neural activity [14]. |

| Allen Common Coordinate Framework | A standardized 3D reference atlas for the mouse brain. | Registering recording sites to a common anatomical framework for cross-study comparison [14]. |

Workflow for Temporal Higher-Order Topological Analysis in fMRI

Higher-Order Interactions in Ecology

Empirical Evidence and Comparative Data

In ecology, the concept of HOIs moves beyond simple predator-prey or competitive pairs to consider how the interplay between three or more species, or between multiple human pressures, shapes biodiversity. A landmark 2025 meta-analysis compiled an unprecedented dataset from 2,133 publications, covering 97,783 sites and 3,667 comparisons, to quantify how human pressures affect biodiversity across different dimensions [15]. The analysis explicitly tested for changes in local diversity, compositional shifts, and biotic homogenization—a process where previously distinct biological communities become more similar, often driven by the non-random, joint effects of multiple pressures.

Contrary to long-standing ecological theory that predicted general biotic homogenization, the meta-analysis found no evidence of systematic homogenization from human pressures overall. Instead, the response was context-dependent, mediated by the type of pressure and the spatial scale of the study. This critical finding, which pairwise models failed to anticipate, underscores the need for a higher-order perspective that can account for the interacting effects of multiple factors [15].

Table 3: Impact of Human Pressures on Different Dimensions of Biodiversity

| Human Pressure | Effect on Local Diversity (LRR) | Effect on Compositional Shift (LRR) | Effect on Homogenization (LRR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land-Use Change | Decrease | 0.467 to 0.661 (Increase) | Varied with scale |

| Resource Exploitation | Decrease | Significant Increase | -0.197 to -0.036 (Differentiation) |

| Pollution | Decrease | Significant Increase | -0.129 to -0.012 (Differentiation) |

| Climate Change | Decrease | Significant Increase | Varied with scale |

| Invasive Species | Decrease | Significant Increase | Varied with scale |

| Overall Impact | Distinct Decrease | Distinct Shift (0.564) | No clear general effect |

The data shows that while all five major human pressures consistently decrease local diversity and cause significant shifts in community composition, their effect on spatial homogeneity is not uniform. Pressures like resource exploitation and pollution actually caused biotic differentiation (communities becoming more different), particularly at smaller spatial scales. This demonstrates that the net effect of human activity on biodiversity is not a simple, predictable pairwise force but a higher-order phenomenon that can only be accurately described by considering the interplay of specific pressures, organismal groups, and spatial scales [15].

Experimental Protocols for Ecological HOI Analysis

Protocol: Meta-Analytical Assessment of Biodiversity Change

- Literature Compilation & Inclusion Criteria: Systematically compile studies from scientific databases using predefined search terms. Include studies that contrast impacted sites (subject to human pressures) with reference (control) sites. The 2025 meta-analysis compiled 2,133 publications covering terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems [15].

- Data Extraction & Standardization: For each study, manually extract data on key biodiversity measures. This includes:

- Local Diversity: Species richness at a single site.

- Compositional Shift: The difference in species composition between impacted and reference sites.

- Homogeneity: The similarity in composition among multiple impacted sites versus among multiple reference sites. Calculate a standardized effect size for each comparison, such as the log-response ratio (LRR), which is the logarithm of the ratio between the impacted and reference values [15].

- Mediating Factor Classification: Classify each comparison based on potential mediating factors:

- Type of Human Pressure: Land-use change, resource exploitation, pollution, climate change, invasive species.

- Biome: Terrestrial, freshwater, marine.

- Spatial Scale: Local, regional, global.

- Organismal Group: Plants, tetrapods, fish, insects, etc [15].

- Statistical Modeling: Use mixed linear models to estimate the overall magnitude and significance of biodiversity changes. The models should include the mediating factors as fixed effects to test their influence, and study identity as a random effect to account for non-independence of multiple comparisons from the same study [15].

- Interpretation: Generalize findings to show how the effects of human pressures are not monolithic but are distinctly mediated by higher-order interactions between pressures, biomes, and scales.

Higher-Order Interactions in Pharmacology and Toxicology

Empirical Evidence and Comparative Data

In pharmacology, the concept of HOIs is crucial for understanding polypharmacy, mixture toxicology, and the complex etiology of diseases. A single substance rarely acts in isolation within a biological system; its effect is modulated by the presence of other substances and the physiological state of the organism. This is starkly illustrated in the investigation of prenatal acetaminophen exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes.

A rigorous 2025 systematic review applied the Navigation Guide methodology to 46 studies on prenatal acetaminophen exposure and neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). The findings reveal a complex landscape where the effect of exposure is likely modified by higher-order factors such as genetic susceptibility, timing of exposure, and co-exposure to other stressors [16].

Table 4: Association Between Prenatal Acetaminophen Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

| Outcome | Number of Studies (Total=46) | Studies Showing Positive Association | Studies Showing Null Association | Studies Showing Negative Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 18 (non-duplicative) | Majority | Minority | N/A |

| ASD | 7 (non-duplicative) | Majority | Minority | N/A |

| Other NDDs | 17 (non-duplicative) | Majority | Minority | 4 (Protective) |

| Overall Trend | Higher-quality studies more likely to show positive associations. |

The table shows that while the majority of studies report a positive association (increased risk), a significant number show null associations, and some even suggest protective effects. This heterogeneity is a classic signature of higher-order interactions. The effect of acetaminophen is not a simple, deterministic pairwise relationship but is contingent on other variables. The review concluded that the evidence is consistent with an association between exposure and increased incidence of NDDs, but the presence of conflicting results underscores that the biological pathway involves a web of interacting factors beyond a simple cause-and-effect pair [16].

Similarly, environmental toxicology is moving beyond the study of single contaminants. A 2025 study on tire wear particles used nontargeted screening to identify a more diverse array of toxic p-phenylenediamine antioxidant-derived quinones (PPD-Qs) than previously known. This discovery of multiple structurally related compounds highlights that real-world exposure involves complex mixtures, where the combined toxicological effect (the higher-order interaction) may be greater than, or different from, the sum of effects from individual compounds studied in isolation [17].

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacological HOI Analysis

Protocol: Navigation Guide for Systematic Evidence Review

- Define the Research Question (PECO Framework):

- Population: Offspring of pregnant women.

- Exposure: Prenatal acetaminophen (measured via self-report, biomarkers, or records).

- Comparator: Offspring of pregnant women not exposed to acetaminophen.

- Outcome: Neurodevelopmental disorders (ADHD, ASD) or related symptoms [16].

- Systematic Literature Search: Conduct a comprehensive search of databases (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science) using predefined keyword strategies. The 2025 review searched through February 2025. Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts, then to full-text articles [16].

- Data Extraction & Risk of Bias Assessment: Use standardized forms to extract data (study design, sample size, risk estimates, confidence intervals). Critically, rate each study for risk of bias using a structured framework like GRADE, evaluating factors like participant selection, exposure assessment, and confounding control [16].

- Evidence Synthesis and Rating: Synthesize the body of evidence. Rather than just counting studies, weigh the evidence based on study quality and risk of bias. The Navigation Guide methodology specifically rates the overall strength of evidence (e.g., high, moderate, low, insufficient) considering factors like risk of bias, consistency of results across studies, and precision of effect estimates [16].

- Conclusion and Translation: Draw a conclusion about the evidence for a causal relationship. The conclusion should transparently reflect the strength and consistency of the higher-order evidence base, guiding public health recommendations.

Systematic Review Workflow for Pharmacological HOI Evidence

Integrated Discussion: HOIs as a Cross-Disciplinary Paradigm

The evidence synthesized from neuroscience, ecology, and pharmacology presents a convergent narrative: higher-order interactions are not a niche phenomenon but a fundamental property of complex systems. The failure of pairwise models to capture critical system behaviors—be it the accurate decoding of cognitive tasks in the brain, the scale-dependent impact of pollution on biotic homogenization, or the heterogeneous effects of a common drug—signals a pervasive limitation of the traditional approach. The shift to an HOI framework is more than a technical improvement; it is a paradigm shift that offers a more authentic representation of system complexity.

In neuroscience, HOI analysis moves us from a static map of brain regions to a dynamic understanding of how neural assemblies collectively encode information. In ecology, it transforms our view of human impact from a simple, homogenizing force to a context-dependent driver of change, which is critical for benchmarking effective conservation strategies [15]. In pharmacology, it pushes the field beyond one-drug, one-outcome models toward a more holistic view of patient health, disease etiology, and mixture toxicology.

The methodological advances driving this shift—topological data analysis in neuroscience, large-scale meta-analytics in ecology, and rigorous evidence integration in pharmacology—provide a toolkit for researchers across disciplines. While the computational burden of analyzing HOIs is significant, as seen in the analysis of 187,460 unique triple interactions in a single brain [7], the payoff in explanatory and predictive power makes it an indispensable avenue for future research. For scientists and drug development professionals, embracing this higher-order perspective is essential for generating robust, translatable findings that reflect the true complexity of biological systems.

Polypharmacy, commonly defined as the use of five or more concurrent medications, presents a significant and growing challenge in clinical pharmacology, particularly for vulnerable populations such as older adults with cancer [18]. This medication complexity creates a perfect storm for unexplained adverse drug reactions (ADRs) through intricate drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that often evade prediction by conventional methods. Recent evidence indicates that 36.0% to 38.0% of older Chinese cancer patients experience polypharmacy, with clinically significant DDIs affecting 20.1% to 23.0% of these individuals, directly contributing to ADR rates of 6.9% to 8.1% [18]. The situation is particularly acute in geriatric oncology; for example, prospective cohorts of older breast cancer patients reveal a median of eleven concomitant drugs, with clinically relevant potential DDIs present in up to 75% of patients [19].

The central challenge lies in the combinatorial explosion of possible interactions. While exhaustive testing of all possible drug combinations grows exponentially with each additional medication, emerging research suggests that higher-order combination effects may be predictable through pairwise interaction data [20] [21]. This article compares methodological approaches for predicting and analyzing these complex interactions, providing clinical researchers with experimental protocols and tools to address this urgent pharmacological problem.

Methodological Comparison: Pairwise Connectivity vs. Higher-Order Interaction Prediction

Fundamental Conceptual Approaches

Current research strategies for understanding complex DDIs generally fall into two complementary paradigms:

Pairwise Connectivity Approach: This method operates on the principle that the behavior of complex, multi-drug systems can be largely explained by aggregating the interactions between all possible drug pairs. It dramatically reduces the experimental burden, as the number of pairs grows quadratically rather than exponentially with the number of drugs [20] [21]. The underlying assumption is that higher-order interactions (involving three or more drugs) are weak or can be decomposed into a simple combination of pairwise effects, a concept successfully demonstrated in antibiotic combinations [21].

Higher-Order Interaction Research: This paradigm directly investigates emergent properties that arise only when three or more drugs are combined simultaneously and cannot be predicted from any subset of pairwise interactions alone. This approach acknowledges that complex biological systems, such as neural circuits for goal-directed learning, encode information through synergistic interactions at the level of triplets and quadruplets, with long-range relationships that are not fully captured by pairwise models [4].

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Models and Tools

The table below summarizes key methodologies and tools used for DDI prediction and analysis, highlighting their core applications and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Methodologies for Drug Interaction Analysis

| Method/Tool | Core Approach | Primary Application Context | Key Advantage | Principal Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose Model [21] [20] | Mathematical prediction of high-order effects from pairwise interaction parameters. | Screening antibiotic/anti-cancer drug combinations. | Reduces experimental burden from exponential to quadratic complexity. | Relies on assumption that higher-order effects are derivable from pairs. |

| eyesON Drug Interaction Visualizer [22] [23] | Data mining of FDA adverse event reports to profile two-drug interaction patterns. | Clinical decision support; post-market surveillance. | Uses real-world data from a large-scale regulatory database. | Limited to pairwise analysis; cannot predict novel high-order synergies/antagonisms. |

| PyRx Virtual Screening Software [24] | Computational docking of drug molecules against protein targets in silico. | Early-stage drug discovery and lead compound identification. | Can screen vast chemical libraries without wet-lab experiments. | Predictive accuracy is limited by the quality of the protein structure and scoring functions. |

| Information Decomposition in Neural Systems [4] | Analyzing redundant and synergistic information flow in brain networks via magnetoencephalography. | Basic research on how learning signals are encoded in neural circuits. | Provides a theoretical framework for quantifying synergy beyond pairs. | Currently not directly applicable to pharmacology or drug screening. |

Experimental Data & Protocols for Interaction Prediction

Key Experimental Findings on Prevalence and Risk

Quantitative data from clinical and preclinical studies underscores the scale of the polypharmacy problem and validates predictive modeling approaches.

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence on Polypharmacy and Interaction-Derived Risk

| Study Context | Polypharmacy Prevalence | DDI Prevalence | Associated ADR Risk Increase | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older Chinese Cancer Patients (n=408) | 36.0% (Baseline) to 38.0% (Follow-up) | 20.1% to 23.0% | Polypharmacy: OR=2.21 (1.14-4.30)DDIs: OR=3.28 (1.54-6.99) | [18] |

| Older Breast Cancer Patients (Geriatric Oncology Cohort) | ~52% to 75% | 31% to 75% | Severe DDI nearly doubles non-hematological toxicity (OR=1.94, 1.22-3.09) | [19] |

| E. coli Growth Inhibition (10 antibiotics) | N/A | 45 drug pairs measured | Dose model accurately predicted effects of 3-10 drug combinations using only pairwise data. | [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Predicting High-Order Combinations via the Dose Model

The following protocol, adapted from Katzir et al. (2019), provides a validated methodology for predicting the effects of ultra-high-order drug combinations using pairwise data [21].

Objective: To accurately predict the growth inhibitory effect of multi-drug antibiotic combinations (e.g., 3-10 drugs) on E. coli using only single-drug and pairwise interaction measurements, thereby overcoming the combinatorial explosion problem.

Materials:

- Biological System: E. coli culture strain.

- Drugs: 10 antibiotics with diverse mechanisms of action (e.g., from Table 1 of [21]).

- Equipment: 96-well plates, plate reader for optical density (OD) measurement at 600nm.

- Software: Data analysis software (e.g., Python, R) for implementing the dose model.

Procedure:

- Single-Drug Dose-Response Curves:

- Prepare a series of 13 linearly spaced doses for each of the 10 individual antibiotics. The middle dose should approximate the D50 (dose causing 50% growth inhibition).

- Incubate E. coli with each drug at each dose for 12 hours.

- Measure the OD600nm to determine the growth reduction,

g(D_i), for each drugiat doseD_i. The effectgis defined as the reduction in growth relative to the no-drug control. - Fit a Hill curve to each single-drug dose-response data set.

Pairwise Drug Interaction Screen:

- For all 45 possible pairs of the 10 drugs, test 13 "diagonal" dose combinations. This involves mixing the two drugs, with each at half of its 13 single-drug doses, resulting in 13 dose combinations per pair.

- Measure the combined growth inhibition,

g(D_i, D_j), for each pair(i,j)at each dose combination.

Parameter Fitting for the Dose Model:

- Use the pairwise data to fit interaction parameters

a_ijanda_jifor each drug pair. The fundamental assumption of the dose model is that each drug linearly rescales the effective concentration of its partner. - The model uses these parameters to predict the effect of any higher-order combination. The effective dose of drug

iin an N-drug cocktail is modeled as being rescaled by the presence of all other drugsj.

- Use the pairwise data to fit interaction parameters

Model Validation and Prediction:

- To validate, measure the actual growth inhibition of a selection of 3-to-10-drug combinations across various doses.

- Compare these empirical results to the predictions generated by the dose model using only the fitted pairwise parameters

a_ij. - The accuracy of the model can be quantified using metrics like R² or root-mean-square error (RMSE) between predicted and observed effects.

Logical Workflow of the Dose Model Protocol:

For researchers investigating polypharmacy and complex DDIs, the following tools and resources are critical.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Interaction Databases | Identify known pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic DDIs for clinical correlation. | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) via tools like the eyesON Visualizer [22] [23]. |

| Virtual Screening Software | Perform in-silico docking to predict drug-target and potential drug-drug binding interference. | PyRx software, which incorporates AutoDock Vina and other docking engines [24]. |

| Validated Prescribing Tools | Identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) in complex regimens during medication reviews. | STOPP/START criteria or Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) [25] [26]. |

| Mathematical Modeling Environment | Implement and test predictive models like the Dose Model or higher-order interaction networks. | Python or R with packages for scientific computing and nonlinear regression [21]. |

| Clinical Polypharmacy Guidelines | Inform the design of interventions and deprescribing strategies based on evidence-based recommendations. | National guidelines on medication review and management in polypharmacy [26]. |

The urgency posed by polypharmacy and unexplained ADRs demands a multi-faceted research strategy. While pairwise connectivity models offer a pragmatically feasible path to navigate the combinatorial explosion and have demonstrated remarkable predictive power for antibiotic combinations [21], a complete understanding requires acknowledging and quantifying genuine higher-order interactions that emerge in complex biological systems [4]. The future of safer pharmacology in an aging, multi-medicated population lies in integrating these approaches: using pairwise models as a powerful screening tool to prioritize combinations, while developing more sophisticated experimental and computational frameworks to detect and validate critical higher-order synergistic toxicities. This integration will be essential for advancing from reactive ADR detection to proactive, predictive risk assessment in polypharmacy.

Mapping the Unseen: Techniques for Capturing and Modeling HOIs

The analysis of complex biological systems has traditionally relied on network science, with weighted complete graphs serving as a fundamental representation for modeling pairwise relationships between entities. In genetics, methods like Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) construct networks where genes are nodes connected by edges weighted according to their pairwise correlation coefficients, identifying modules of co-expressed genes through topological overlap matrices [27]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical research, databases like TWOSIDES document pairwise drug-drug interactions, representing these relationships through conventional graph structures where drugs are nodes and edges capture their two-way interactive effects [28].

However, a fundamental limitation plagues these pairwise approaches: many biological phenomena inherently involve higher-order interactions where three or more elements interact simultaneously in ways that cannot be decomposed into simpler pairwise components. Recognizing this limitation, researchers are increasingly turning to hypergraph-based representations that can naturally capture these complex multi-way relationships [27] [28]. In hypergraphs, hyperedges can connect any number of nodes, enabling more faithful modeling of biological reality where gene regulatory complexes, multi-drug therapeutic combinations, and protein-protein interaction networks often involve simultaneous interactions among multiple entities [29] [30].

This paradigm shift from graphs to hypergraphs represents more than a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental rethinking of how we represent and analyze biological complexity. Where graphs can only capture the structure of pairwise relationships, hypergraphs can capture the higher-order organization of biological systems, leading to more accurate models, better predictions, and deeper insights into the underlying mechanisms driving biological phenomena [31] [29].

Theoretical Foundations: From Graphlets to Hyper-Graphlets

Graphlets: The Building Blocks of Networks

In traditional network analysis, graphlets serve as the fundamental building blocks of complex networks. These small, connected, non-isomorphic subgraphs represent the local topological patterns that define a network's structural properties. In biological contexts, specific graphlet occurrence patterns can characterize functional structures within gene regulatory networks, protein-protein interaction networks, and metabolic pathways. The analysis of graphlets has provided crucial insights into network organization, enabling researchers to compare networks topologically and identify statistically significant motifs that may correspond to functional units within biological systems.

Hyper-Graphlets: Generalizing to Higher-Order Structures

Hyper-graphlets extend this conceptual framework to hypergraphs, serving as small, connected hypergraph patterns that capture the local higher-order organization of complex systems. Where traditional graphlets are limited to capturing pairwise connectivity patterns, hyper-graphlets can represent the intricate ways in which multiple elements interact simultaneously, providing a more nuanced and powerful framework for characterizing biological systems [27] [29].

The mathematical representation of hyper-graphlets requires more complex data structures than their graph-based counterparts. While a simple adjacency matrix suffices for representing traditional graphs, hypergraphs require incidence matrices or other specialized representations to capture which nodes participate in which hyperedges [27]. This increased representational complexity enables hyper-graphlets to detect and quantify structural patterns that are invisible to traditional graphlet analysis, particularly those involving group interactions and higher-order dependencies that characterize many biological processes [31] [28].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Graphlets vs. Hyper-Graphlets

| Feature | Graphlets | Hyper-Graphlets |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Graph theory | Hypergraph theory |

| Relationship Type | Pairwise interactions | Higher-order, multi-way interactions |

| Representation | Adjacency matrix | Incidence matrix |

| Biological Applications | Protein-protein interactions, gene co-expression networks (WGCNA) | Multi-gene regulatory complexes, polypharmacy effects, patient phenotyping |

| Structural Patterns | Limited to dyadic connections | Can capture complex group interactions |

| Data Requirements | Pairwise correlation matrices | Multi-way association data |

Experimental Comparison: Performance Benchmarks

Gene Co-expression Analysis

In genomic research, both weighted complete graphs and hypergraph approaches have been applied to gene co-expression analysis, with significant performance differences observed. Traditional WGCNA constructs networks where genes are connected based on pairwise correlation coefficients, identifying modules of co-expressed genes through topological overlap matrices [27]. While this approach has proven valuable, it struggles to capture higher-order interactions and exhibits computational inefficiency with large, complex datasets.

The Weighted Gene Co-expression Hypernetwork Analysis (WGCHNA) method addresses these limitations by constructing a hypergraph where genes are modeled as nodes and samples as hyperedges [27]. By calculating the hypergraph Laplacian matrix, WGCHNA generates a topological overlap matrix for module identification through hierarchical clustering. Experimental results across four gene expression datasets demonstrate that WGCHNA outperforms WGCNA in module identification and functional enrichment, identifying biologically relevant modules with greater complexity and uncovering more comprehensive pathway hierarchies [27].

Table: Performance Comparison in Gene Co-expression Analysis

| Metric | WGCNA (Graph-Based) | WGCHNA (Hypergraph-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Module Identification Accuracy | Baseline | Superior - identifies more biologically relevant modules |

| Computational Efficiency | Lower with large, complex datasets | Higher efficiency in handling large datasets |

| Functional Enrichment | Standard | More comprehensive pathway hierarchies |

| Biological Insight | Captures pairwise correlations | Reveals higher-order regulatory relationships |

| Application Example | Gene co-expression patterns | Neuronal energy metabolism linked to Alzheimer's disease |

Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

The field of computational pharmacovigilance provides particularly compelling evidence for the superiority of hypergraph approaches in modeling complex biological interactions. Traditional resources like TWOSIDES focus primarily on pairwise drug interactions, representing these relationships through conventional graph structures [28]. While valuable, this approach fundamentally limits our understanding of polypharmacy effects, where patients frequently take three or more medications simultaneously.

The HODDI (Higher-Order Drug-Drug Interaction) dataset addresses this gap by capturing multi-drug interactions from FDA Adverse Event Reporting System records [28]. When evaluated with multiple models, hypergraph approaches demonstrated superior performance in capturing complex multi-drug interactions. Simple Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) utilizing higher-order features from HODDI sometimes outperformed sophisticated graph models like Graph Attention Networks (GAT), suggesting the inherent value of higher-order drug interaction data itself [28]. However, models explicitly incorporating hypergraph structures, such as HyGNN, further enhanced prediction accuracy by directly capturing complex multi-drug relationships.

Disease Gene Prioritization

In medical genetics, phenotype-driven disease prediction has been revolutionized by hypergraph approaches. Traditional methods like Phenomizer and Graph Convolution Networks (GCN) have provided valuable tools for linking patient phenotypes to potential genetic diagnoses, but face limitations in capturing the complex multi-way relationships between genes, phenotypes, and diseases [30].

A novel hypergraph-powered approach to phenotype-driven gene prioritization demonstrates remarkable performance improvements, capturing 50% of causal genes within the top 10 predictions and 85% within the top 100 predictions [30]. The algorithm maintains a high accuracy rate of 98.09% for the top-ranked gene, significantly outperforming existing state-of-the-art tools in both prediction accuracy and processing speed [30]. This performance advantage stems from the hypergraph framework's ability to naturally represent the multifaceted relationships inherent in genetic data, where genes contribute simultaneously to multiple phenotypic traits and diseases.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

WGCHNA Protocol for Gene Co-expression Analysis

The Weighted Gene Co-expression Hypernetwork Analysis (WGCHNA) method follows a structured workflow for identifying gene modules from expression data [27]:

Data Preprocessing: Raw gene expression data is normalized and quality-controlled using standard bioinformatics pipelines.

Hypergraph Construction: Genes are modeled as nodes, while samples constitute hyperedges. This representation naturally captures the co-expression patterns across multiple genes within individual samples.

Laplacian Matrix Calculation: The hypergraph Laplacian matrix is computed to characterize the network's global properties and topological structure.

Topological Overlap Computation: A topological overlap matrix (TOM) is derived from the Laplacian to quantify the interconnectedness of any two genes based on their higher-order relationships.

Hierarchical Clustering: Genes are clustered using the topological overlap matrix to identify modules of co-expressed genes.

Functional Enrichment Analysis: Identified modules are analyzed for enrichment of biological pathways and functions using standard ontologies.

This methodology was validated on four gene expression datasets, including mouse Alzheimer's disease data (5xFAD) from MODEL-AD and breast cancer data (GSE48213) from GEO [27].

HODDI Protocol for Drug Interaction Analysis

The Higher-Order Drug-Drug Interaction (HODDI) dataset construction and analysis follows a rigorous protocol [28]:

Data Sourcing: Extraction of raw data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) records spanning the past decade.

Data Curation and Filtering: Implementation of stringent quality control measures to select cases involving co-administered drugs, focusing specifically on multi-drug combinations and their collective impact on adverse effects.

Hypergraph Model Construction: Representation of drugs as nodes and multi-drug therapy regimens as hyperedges, with adverse effects as properties of these hyperedges.

Model Evaluation: Comparison of multiple computational approaches including MLP, GAT, and hypergraph neural networks (HyGNN) using carefully constructed evaluation subsets.

Statistical Validation: Comprehensive statistical analyses to characterize the dataset's properties and validate the significance of identified higher-order interactions.

The final HODDI dataset contains 109,744 records involving 2,506 unique drugs and 4,569 unique side effects, specifically curated to capture multi-drug interactions [28].

Hypergraph-Based Gene Prioritization Protocol

The phenotype-driven disease prediction framework utilizes hypergraphs for prioritizing causal genes [30]:

Data Integration: Consolidation of 2130 diseases, 4655 genes, and 9541 phenotypes from Orphanet and Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) databases.

Multi-Relational Hypergraph Construction: Implementation of a hypergraph structure that simultaneously captures gene-disease, gene-phenotype, and disease-phenotype relationships as hyperedges rather than simple pairwise links.

Robust Ranking Algorithm Application: Utilization of specialized ranking algorithms designed specifically for hypergraph structures to prioritize candidate genes based on phenotypic similarity.

Validation Against Known Associations: Benchmarking of predictions against established gene-disease associations to quantify performance metrics.

Comparison with Existing Tools: Direct performance comparison with state-of-the-art tools including Phenomizer and GCN-based approaches across multiple metrics including accuracy, precision, and computational efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| HODDI Dataset | Provides higher-order drug-drug interaction data | Computational pharmacovigilance, polypharmacy research |

| Orphanet & HPO Databases | Source of disease-gene-phenotype associations | Rare disease diagnosis, gene prioritization |

| FAERS Database | Repository of real-world drug adverse event reports | Drug safety research, interaction discovery |

| WGCHNA Algorithm | Implements hypergraph-based gene co-expression analysis | Genomic module discovery, functional enrichment |

| Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNN) | Deep learning framework for hypergraph-structured data | Various domains including drug interaction prediction |

| Implicit HGNN (IHGNN) | Advanced hypergraph network with equilibrium formulation | Citation network analysis, relational learning |

| TabNet with Hypergraph Features | Interpretable deep learning for tabular data | Student performance prediction, feature importance analysis |

The experimental evidence across multiple domains consistently demonstrates the superior capability of hypergraph representations compared to traditional weighted complete graphs for capturing the complexity of biological systems. In gene co-expression analysis, drug interaction prediction, and disease gene prioritization, hypergraph-based methods consistently outperform their graph-based counterparts in accuracy, biological relevance, and ability to uncover novel relationships [27] [28] [30].

This performance advantage stems from the fundamental ability of hypergraphs to naturally represent higher-order interactions that characterize biological reality, where multi-gene regulatory complexes, polypharmacy effects, and pleiotropic genes involve simultaneous interactions among multiple elements. The research community is increasingly recognizing that pairwise connectivity models, while valuable, provide an incomplete picture of biological complexity [31] [29].

As the field continues to evolve, several promising research directions emerge. More sophisticated hypergraph learning algorithms, including implicit hypergraph neural networks and equilibrium models, show potential for further improving performance and scalability [29]. The development of standardized hypergraph datasets across biological domains will enable more systematic benchmarking and method development. Finally, the creation of specialized hypergraph analysis tools designed specifically for biological researchers will help bridge the gap between methodological advances and practical applications in genomics, drug discovery, and precision medicine.