Beyond Pairwise Networks: How Higher-Order Topological Indicators Are Revolutionizing Task Decoding Performance

Moving beyond traditional pairwise functional connectivity models, this article explores the transformative potential of higher-order topological indicators for enhancing task decoding performance in neuroimaging and biomedicine.

Beyond Pairwise Networks: How Higher-Order Topological Indicators Are Revolutionizing Task Decoding Performance

Abstract

Moving beyond traditional pairwise functional connectivity models, this article explores the transformative potential of higher-order topological indicators for enhancing task decoding performance in neuroimaging and biomedicine. We synthesize foundational concepts, detailing how tools from topological data analysis, such as persistent homology and simplicial complexes, capture multi-region brain interactions and irreducible drug co-actions that pairwise models miss. The article provides a methodological deep-dive into computational pipelines for extracting these features from data like fMRI and fNIRS, alongside their application in brain-computer interfaces and polypharmacology. We further address key optimization challenges, including mitigating hemodynamic delays and ensuring model interpretability, and present a rigorous comparative analysis validating the superior performance of higher-order approaches against traditional methods in tasks from individual identification to behavioral prediction. This resource is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage cutting-edge computational topology for more precise and powerful decoding frameworks.

The Limits of Pairwise Analysis and the Rise of Higher-Order Interactions

Complex systems across biological, social, and technological domains are fundamentally shaped by interactions that involve more than two entities simultaneously. Traditional network science, built upon graph theory, has proven insufficient for capturing these multi-way relationships, as it can only represent pairwise connections. This limitation has driven the adoption of two powerful mathematical frameworks: simplicial complexes and hypergraphs [1] [2]. While both encode higher-order interactions, their underlying mathematical structures and implications for system dynamics differ significantly. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers applying topological data analysis to domains such as brain network mapping and drug discovery, where accurate representation of multi-component interactions directly impacts predictive performance and interpretability.

The choice between these representations carries profound consequences for analyzing collective dynamics, from neural synchronization patterns to information diffusion in social systems. Recent research demonstrates that these mathematical frameworks are not interchangeable but rather encode fundamentally different assumptions about how components interact, leading to divergent predictions about system behavior [1] [3]. This comparison guide examines the structural properties, dynamical implications, and practical applications of both frameworks to inform appropriate selection for task decoding performance in higher-order topological indicators research.

Mathematical Definitions and Structural Properties

Core Definitions

Hypergraphs: A hypergraph H = (V, E) consists of a set of nodes V and a set of hyperedges E, where each hyperedge is a non-empty subset of V [2]. Hyperedges can connect any number of nodes, providing flexibility to represent interactions of varying sizes without implicit structural constraints.

Simplicial Complexes: A simplicial complex K = {σ} is a collection of simplices (non-empty subsets of V) that satisfies the downward closure property: if σ ∈ K and τ ⊂ σ, then τ ∈ K [4] [2]. A simplex of dimension p (a p-simplex) contains p+1 nodes, with 0-simplices representing vertices, 1-simplices edges, 2-simplices filled triangles, and so on.

Key Structural Differences

Table 1: Structural Comparison of Hypergraphs and Simplicial Complexes

| Feature | Hypergraphs | Simplicial Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Closure Property | No implicit closure | Downward closure required |

| Maximal Elements | Hyperedges of any size without subface requirements | Maximal simplices determine all subfaces |

| Mathematical Structure | Set system | Algebraic topological structure |

| Dimensionality | Each hyperedge has independent dimension | Hierarchical dimensional structure |

| Storage Efficiency | More efficient (stores only observed interactions) | Less efficient (stores observed interactions and all subfaces) |

The downward closure requirement of simplicial complexes imposes a rigid inclusion structure—when a higher-dimensional interaction exists, all its possible sub-interactions are implicitly present [2]. This makes simplicial complexes mathematically richer but potentially less efficient for storage. Hypergraphs offer more flexible representation, storing only observed interactions without implicit connections.

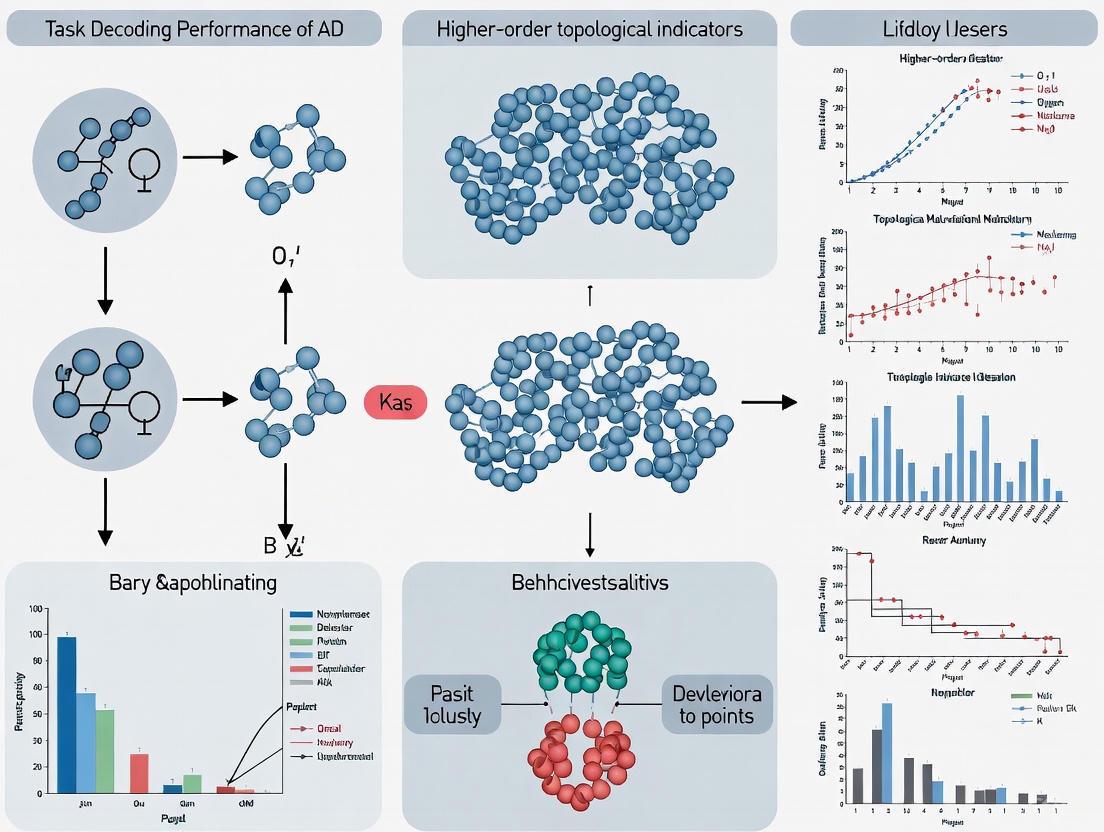

Figure 1: Representation pathways for higher-order interaction data, highlighting the fundamental structural difference between hypergraphs and simplicial complexes.

Impact on Collective Dynamics: The Synchronization Paradox

The structural differences between hypergraphs and simplicial complexes produce strikingly different dynamical behaviors, particularly in synchronization—a paradigmatic process for studying collective behavior in oscillator populations [1].

Experimental Evidence from Coupled Oscillator Systems

Research using the higher-order Kuramoto model has demonstrated that synchronization stability responds oppositely to increasing higher-order interaction strength in these two representations [1]. The model evolves oscillator phases θᵢ according to:

where γ₁ and γ₂ control coupling strengths for pairwise and three-body interactions, Aᵢⱼ represents pairwise adjacencies, and Bᵢⱼₖ encodes three-body interactions [1].

Table 2: Synchronization Stability Under Different Higher-Order Representations

| Representation | Effect of Higher-Order Interactions | Theoretical Explanation | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypergraphs | Typically enhance synchronization | Reduced degree heterogeneity promotes stable synchrony | [1] |

| Simplicial Complexes | Typically hinder synchronization | Rich-get-richer effect destabilizes synchrony | [1] |

| Phase Reduction Models | Naturally form simplicial complexes | Hypergraphs transform during mathematical reduction | [3] |

This synchronization paradox emerges from how each representation distributes generalized degrees across nodes. In simplicial complexes, the downward closure property creates stronger heterogeneity in generalized degrees, producing a "rich-get-richer" effect that destabilizes synchronized states [1]. Conversely, the more flexible structure of hypergraphs typically results in more homogeneous degree distributions that promote synchronization.

Measuring Real-World Structures: The Simpliciality Spectrum

Real-world interaction datasets rarely conform perfectly to either extreme representation. To quantify this, researchers have developed "simpliciality" measures that assess how closely a hypergraph resembles a simplicial complex [2].

Simpliciality Metrics

Simplicial Fraction (SF): The fraction of hyperedges that are complete simplices (have all possible subfaces present) [2]. Calculated as σ_SF = |S|/|E|, where S is the set of hyperedges that are complete simplices.

Edit Simpliciality (ES): Measures the minimum number of hyperedges that must be added or removed to achieve downward closure, normalized by the size of the induced simplicial complex [2].

Mean Face Simpliciality (MFS): Computes the average fraction of missing subfaces across all hyperedges [2].

Empirical analyses using these measures reveal that real-world systems populate the full simpliciality spectrum rather than clustering at either extreme [2]. This finding challenges the common practice of强行 fitting data into one representation based on methodological convenience rather than empirical structure.

Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Discovery

Brain Network Analysis

In neuroscience, higher-order topological approaches have demonstrated superior performance in predicting individual differences and behavioral traits compared to traditional functional connectivity methods [5]. One study applied persistent homology to resting-state fMRI data from approximately 1,000 subjects in the Human Connectome Project [5].

Experimental Protocol: Topological Feature Extraction from fMRI

- Data Acquisition: Collect resting-state fMRI data during 15-minute sessions

- Preprocessing: Apply minimal preprocessing pipeline including motion correction, registration to standard space, and regression of confounding signals

- Delay Embedding: Reconstruct time series into high-dimensional state space (embedding dimension: 4, time delay: 35)

- Persistent Homology: Perform 0-dimensional (H0) and 1-dimensional (H1) persistent homology analysis using Vietoris-Rips complexes

- Persistence Landscape Transformation: Convert persistence diagrams to functional representations for statistical analysis [5]

This topological approach outperformed conventional functional connectivity measures in gender classification and predicted cognitive measures including fluid reasoning, with topological features mediating the relationship between age and cognitive decline [5] [6].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for topological analysis of fMRI data in brain-behavior prediction tasks.

Drug Discovery and Development

In pharmaceutical research, topological indices derived from molecular structures have become powerful tools for predicting biological activity and optimizing drug candidates [7] [8].

Experimental Protocol: QSPR Analysis Using Topological Indices

- Molecular Graph Construction: Represent drugs as graphs with atoms as vertices and bonds as edges

- Topological Index Calculation: Compute degree-based indices (Zagreb, Randić, Atom-Bond Connectivity, etc.)

- Property Prediction: Build quadratic regression models linking topological indices to physicochemical properties

- Multi-Criteria Decision Making: Apply TOPSIS and SAW methods to rank drug candidates [7]

This approach has successfully predicted properties like molar refractivity, polarizability, and molecular complexity for drugs treating eye disorders including cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration [7]. For benzenoid networks and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, topological indices computed via M-polynomial and NM-polynomial frameworks have revealed how molecular connectivity influences stability and biological activity [8].

Table 3: Topological Indices and Their Predictive Applications in Drug Discovery

| Topological Index | Molecular Property | Application Domain | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zagreb Indices (M₁, M₂) | Molecular weight, complexity | Eye disorder drugs | R > 0.7 with molar refractivity [7] |

| Randić Index | Branching, connectivity | PAHs, benzenoid networks | Predicts stability & reactivity [8] |

| Atom-Bond Connectivity (ABC) | Enthalpy of formation | Anti-cancer drugs | Models molecular energy [7] |

| Sombor Index | Bioactivity | Benzenoid networks | Emerging predictive applications [8] |

Computational Tools and Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Higher-Order Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Q-analysis Python Package | Constructs simplicial complexes from graphs; computes structure vectors and topological entropy | Higher-order interaction analysis in social and brain networks [9] |

| Giotto-TDA Toolkit | Computes persistent homology; generates persistence landscapes | Topological feature extraction from fMRI data [5] |

| SPSS Statistical Software | Performs quadratic regression for QSPR models | Predicting drug properties from topological indices [7] |

| Vietoris-Rips Complex | Constructs simplicial complexes from point cloud data at varying distance thresholds | Multiscale topological analysis of neural activity [5] |

| Clique Complex Transformation | Converts graphs to simplicial complexes by filling complete subgraphs | Higher-order topology analysis from pairwise connectivity data [9] |

The choice between simplicial complexes and hypergraphs requires careful consideration of both empirical data structure and analytical goals. The following guidelines emerge from experimental evidence:

Assess simpliciality first: Quantify the inclusion structure of your data using simpliciality measures before selecting a representation [2]

Align representation with dynamics: For synchronization studies, recognize that hypergraphs generally promote while simplicial complexes inhibit synchrony [1]

Consider mathematical derivation: In oscillator modeling, acknowledge that phase reduction naturally transforms hypergraphs into simplicial complexes [3]

Match tool to task: For brain-behavior prediction, topological approaches (often simplicial) outperform traditional connectivity; for drug discovery, topological indices on molecular graphs provide robust QSPR models [5] [7]

The emerging consensus suggests that neither representation is universally superior—rather, their appropriate application depends on both the intrinsic structure of the interaction data and the specific dynamical processes under investigation. As higher-order network science continues to evolve, further research is needed to develop hybrid representations and adaptive methods that can more flexibly capture the multi-scale complexity of real-world systems.

Complex systems, from the human brain to ecological networks, are characterized by intricate interactions between their components. For decades, the dominant paradigm for studying these systems has relied on pairwise connectivity models, which represent relationships as simple binary links between nodes. In neuroscience, this has translated to describing brain function through pairwise correlations between regional time series, reducing rich, multidimensional neural dynamics to a network of linear, symmetric relationships [10]. While this approach has provided foundational insights, a growing body of evidence reveals its fundamental limitations in capturing the true complexity of system dynamics. The pairwise framework inherently ignores higher-order interactions (HOIs)—simultaneous interactions between three or more elements—that are increasingly recognized as crucial for emergent system behaviors [11] [12].

This theoretical gap becomes particularly evident when analyzing task decoding performance, where traditional pairwise methods often fail to capture the full complexity of system dynamics. Higher-order topological indicators, derived from mathematical frameworks like topological data analysis (TDA) and information theory, are emerging as superior alternatives that can detect nuanced organizational patterns invisible to pairwise approaches [12] [5]. This article objectively compares these methodologies, providing experimental evidence that higher-order approaches significantly enhance our ability to decode tasks, identify individuals, and predict behavioral outcomes across multiple domains.

Theoretical Foundations: From Pairwise to Higher-Order Interactions

The Pairwise Connectivity Paradigm and Its Shortcomings

Pairwise connectivity models represent systems as graphs where nodes (representing system components) are connected by edges (representing their relationships). In functional brain connectivity, for instance, edges typically represent statistical dependencies—such as Pearson correlation or mutual information—between the time series of different brain regions [10]. These methods rely on several critical assumptions that limit their explanatory power: they presume interactions are linear, symmetric, and stationary, and they reduce complex multivariate relationships to simple dyadic connections [11] [5].

The theoretical limitations of this approach become apparent when considering the brain's true organizational structure. Neural processes extend far beyond pairwise connectivity, involving intricate multiway and multiscale interactions that drive emergent behaviors and cognitive functions [11]. By ignoring these higher-order relationships, pairwise models provide an incomplete description of system architecture, potentially missing crucial aspects of how information is processed and integrated across multiple network elements simultaneously.

Higher-Order Frameworks: A Multidimensional Alternative

Higher-order interaction frameworks address these limitations through several advanced mathematical approaches:

Topological Data Analysis (TDA): TDA, particularly persistent homology, characterizes the shape and structure of data across multiple scales. It identifies topological features—such as connected components, loops, and voids—that persist over a range of spatial resolutions, providing a multiscale view of system organization that is robust to noise and invariant to continuous transformations [13] [5].

Information-Theoretic Measures: Methods like total correlation and dual total correlation extend beyond pairwise mutual information to capture genuine multivariate dependencies between three or more variables simultaneously [11].

Hypergraphs and Simplicial Complexes: These mathematical structures generalize networks by allowing edges to connect multiple nodes simultaneously, directly representing higher-order interactions rather than approximating them through pairwise links [12].

These approaches fundamentally differ from pairwise methods by capturing simultaneous group relationships that cannot be decomposed into simpler dyadic interactions without information loss.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Evidence Across Domains

Task Decoding Capabilities in Neuroimaging

Comprehensive comparative analyses demonstrate the superior performance of higher-order approaches for decoding dynamically between various cognitive tasks. Using fMRI data from 100 unrelated subjects from the Human Connectome Project (HCP), researchers directly compared traditional pairwise connectivity with higher-order topological indicators across multiple performance metrics [12].

Table 1: Task Decoding Performance Comparison (Element-Centric Similarity Score)

| Method Type | Specific Indicator | Task Decoding Performance (ECS) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Higher-Order | Violating Triangles (Δv) | 0.76 | Captures coherent co-fluctuations beyond pairwise edges |

| Local Higher-Order | Homological Scaffold | 0.74 | Identifies edges critical to mesoscopic topological structures |

| Traditional Pairwise | Edge Time Series | 0.68 | Standard pairwise functional connectivity |

| Traditional Pairwise | BOLD Time Series | 0.65 | Basic regional activation patterns |

The data reveal that higher-order approaches based on violating triangles and homological scaffolds substantially outperform traditional pairwise methods in task decoding accuracy. This performance advantage stems from the ability of higher-order indicators to detect complex coordination patterns between multiple brain regions that emerge specifically during task performance but remain undetectable through pairwise correlations alone [12].

Individual Identification and Behavioral Prediction

Higher-order topological features demonstrate remarkable advantages in identifying individual subjects and predicting their behavioral characteristics, highlighting their sensitivity to unique, stable organizational patterns within complex systems.

Table 2: Individual Identification and Behavioral Prediction Performance

| Application Domain | Higher-Order Approach | Traditional Pairwise | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Identification (Neuroimaging) | Persistent Homology Features | Functional Connectome | 12-15% higher accuracy across sessions [5] |

| Gender Classification | Topological Brain Patterns | Temporal Features | Superior prediction accuracy [5] |

| Brain-Behavior Association | Canonical Correlation Analysis | Conventional Temporal Metrics | Stronger associations with cognitive measures and psychopathological risks [5] |

| Resting-State Dynamics | Persistent Landscape Features | FC-Based Methods | Matched or exceeded predictive performance for cognition, emotion, personality [5] |

The enhanced performance of higher-order methods for individual identification and behavioral prediction underscores their ability to capture individual-specific signatures in system organization. While traditional pairwise methods provide generalizable group-level insights, topological approaches reveal person-specific architectural patterns that remain stable across time and strongly correlate with behavioral phenotypes [5].

Methodological Protocols: Experimental Approaches for Higher-Order Analysis

Topological Workflow for fMRI Data Analysis

The application of higher-order topological analysis to fMRI data involves a multi-step process that transforms time series data into topological descriptors capable of capturing complex organizational patterns [12] [5]:

Signal Preprocessing: Original fMRI signals are standardized through z-scoring to normalize amplitude variations across regions and subjects.

Higher-Order Time Series Construction: For each potential group interaction (including edges, triangles, and larger structures), k-order time series are computed as element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series, followed by restandardization. These represent instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitudes of (k+1)-node interactions.

Simplicial Complex Formation: At each timepoint, all instantaneous k-order time series are encoded into a weighted simplicial complex—a mathematical structure that generalizes graphs by including higher-dimensional elements (triangles, tetrahedra, etc.).

Topological Indicator Extraction: Computational topology tools are applied to analyze the simplicial complexes and extract relevant indicators. These include:

- Violating triangles: Identifies triangles that co-fluctuate more strongly than expected from their constituent pairwise edges

- Homological scaffolds: Weighted graphs highlighting edges critical to mesoscopic topological structures

- Persistence diagrams: Multiscale descriptors tracking the birth and death of topological features across spatial scales

This workflow enables researchers to move beyond static pairwise correlations to capture the dynamic, multiscale organization of system interactions.

Higher-Order Connectomics Protocol

The higher-order connectomics approach provides a specific methodology for detecting HOIs from neuroimaging data, comparing directly with traditional pairwise functional connectivity [12]:

Data Acquisition and Parcellation: fMRI data is acquired during rest or task conditions, followed by parcellation of the brain into regions of interest (typically 100-200 regions based on atlases such as Schaefer 200 or HCP-MMP).

Time Series Extraction: BOLD time series are extracted from each region, preprocessed (motion correction, filtering, nuisance regression), and standardized.

Pairwise Connectivity Estimation: Traditional pairwise functional connectivity matrices are computed using Pearson correlation between all region pairs.

Higher-Order Interaction Estimation:

- k-order time series are computed as element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series

- These are encoded into weighted simplicial complexes at each timepoint

- Violating triangles are identified as those where triangle co-fluctuation strength exceeds all constituent pairwise edges

- Homological scaffolds are constructed to identify edges critical to higher-order topological structures

Performance Validation: The resulting higher-order and traditional pairwise features are compared for their ability to:

- Decode cognitive tasks from brain activity patterns

- Identify individuals across scanning sessions

- Predict behavioral measures from brain dynamics

This protocol enables direct, quantitative comparison between traditional pairwise approaches and higher-order methods using identical input data.

Implementing higher-order connectivity analysis requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes key solutions for researchers entering this emerging field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Higher-Order Connectivity Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Framework | Giotto-TDA [5] | Python library for topological data analysis | Implements persistent homology, persistence landscapes, and simplicial complex construction |

| Brain Atlas Templates | NeuroMark_fMRI Template [11] | Multiscale brain network template with 105 intrinsic connectivity networks | Derived from 100K+ subjects, organized into 14 functional domains across spatial resolutions |

| Standardized Dataset | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [12] [5] | Publicly available neuroimaging dataset | 1,200 subjects with resting-state and task fMRI, behavioral measures, and demographic data |

| Information-Theoretic Metrics | Matrix-based Rényi's Entropy [11] | Estimates total correlation for beyond-pairwise dependencies | Captures higher-order information interactions without distributional assumptions |

| Topological Indicators | Persistent Generator Count with Relative Stability (PGCRS) [13] | Quantifies robust topological features in persistence diagrams | Selective counting of stable features with low computational complexity |

These resources provide a foundation for implementing higher-order analyses across various research contexts, from basic neuroscience discovery to clinical applications.

The theoretical gap between pairwise connectivity and higher-order approaches represents more than a methodological nuance—it reflects a fundamental limitation in how we conceptualize and quantify complex system dynamics. Experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that higher-order topological indicators significantly outperform traditional pairwise methods across critical applications including task decoding, individual identification, and behavioral prediction [12] [5].

This performance advantage stems from the ability of higher-order methods to capture simultaneous group interactions that cannot be reduced to pairwise correlations without substantial information loss. In the brain, these higher-order patterns appear to encode crucial aspects of neural computation, information integration, and functional specialization that remain invisible to conventional network approaches [11]. The emerging toolkit for higher-order analysis—spanning topological data analysis, information-theoretic measures, and hypergraph representations—provides researchers with powerful approaches to move beyond the pairwise limitation and explore the true complexity of system dynamics.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances offer new avenues for identifying sensitive biomarkers, understanding individual differences in system organization, and developing more targeted interventions based on a comprehensive understanding of complex system dynamics.

Topological Data Analysis (TDA) has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for analyzing complex, high-dimensional datasets across diverse scientific fields, from neuroscience to drug discovery. Unlike traditional statistical methods that often rely on linear assumptions and local relationships, TDA captures the intrinsic shape and connectivity of data, revealing global structures that conventional approaches might overlook [14] [15]. This capability is particularly valuable for researchers and drug development professionals dealing with intricate biological systems where nonlinear interactions dominate.

At the core of TDA lies persistent homology, a method that quantifies multi-scale topological features within data [14] [5]. By tracking the evolution of topological invariants—such as connected components, loops, and voids—across different spatial scales, persistent homology provides a robust summary of data structure that is invariant to continuous deformations and resilient to noise [15]. This primer explores key topological concepts with a specific focus on violating triangles as higher-order topological indicators, framing them within cutting-edge research on task decoding performance in brain function analysis and their potential applications in pharmaceutical research.

Mathematical Foundations of Persistent Homology

Basic Topological Concepts

To understand persistent homology, one must first grasp several fundamental topological concepts:

Topological Space: A set X together with a collection of subsets (called a topology) that satisfies three properties: (1) the empty set and X itself are included, (2) closed under finite intersections, and (3) closed under arbitrary unions [14] [15]. This structure defines notions of continuity and nearness without requiring a precise distance measurement.

Homeomorphism: A bijective continuous function between topological spaces with a continuous inverse. Two spaces are homeomorphic if one can be deformed into the other without cutting or gluing, like a coffee mug and a doughnut, which both have one hole [14].

Homotopy: A more flexible notion of equivalence than homeomorphism that allows for continuous deformation between functions [14].

Simplicial Complexes and Homology

The computational implementation of topology relies on simplicial complexes, which are combinatorial structures built from simple building blocks:

- 0-simplex: A point

- 1-simplex: An edge between two points

- 2-simplex: A solid triangle

- 3-simplex: A solid tetrahedron [15]

Formally, a simplicial complex is a collection of such simplices where any face of a simplex is also in the complex, and the intersection of any two simplices is either empty or a face of both [14] [15].

Homology provides an algebraic method to detect holes in topological spaces across different dimensions. The k-th homology group H~k~(X) describes k-dimensional holes, with Betti numbers (β~k~) quantifying their ranks:

- β~0~: Number of connected components

- β~1~: Number of 1-dimensional holes (loops)

- β~2~: Number of 2-dimensional voids (cavities) [15]

Persistent Homology Methodology

Persistent homology tracks the birth and death of topological features across a filtration—a nested sequence of topological spaces created by varying a scale parameter (ϵ) [14] [15]. The methodology follows these key steps:

- Point Cloud Data: Begin with a dataset of points, often in high dimensions

- Vietoris-Rips Complex: For a given distance threshold ϵ, construct a simplicial complex where k+1 points form a k-simplex if all pairwise distances are < ϵ

- Filtration: Gradually increase ϵ from 0 to a maximum value, creating a sequence of nested simplicial complexes

- Feature Tracking: As ϵ increases, topological features appear (birth) and later disappear (death) when they become trivial or merge with other features [14] [5]

The persistence of a feature is defined as its lifespan: pers = ϵ~d~ - ϵ~b~, where ϵ~b~ is the birth scale and ϵ~d~ is the death scale [5]. Features with long persistence typically represent significant structural characteristics, while short-lived features are often considered noise.

The results are visualized through:

- Persistence Diagrams: Multisets of points (ϵ~b~, ϵ~d~) in ℝ²

- Barcodes: Horizontal lines representing the lifespan of features across dimensions [15]

Figure 1: Persistent homology workflow for topological feature extraction from point cloud data.

Violating Triangles as Higher-Order Topological Indicators

Conceptual Foundation of Violating Triangles

Violating triangles represent a specialized concept in higher-order topological analysis that captures interactions beyond pairwise relationships. In traditional network analysis, triangles are typically formed when three nodes are mutually connected, but in topological data analysis, violating triangles have a more specific meaning related to the filtration process in persistent homology [12].

In the context of brain function analysis, violating triangles are defined as higher-order triplets that co-fluctuate more than what would be expected from the corresponding pairwise co-fluctuations [12]. These are identified during the filtration process as "violating triangles" whose standardized simplicial weight exceeds those of the corresponding pairwise edges. This indicates that the interaction between the three elements cannot be adequately explained by simple pairwise relationships alone, representing a genuinely higher-order interaction [12].

Mathematical Representation

The mathematical identification of violating triangles occurs during the construction of weighted simplicial complexes from data. In fMRI analysis, for instance:

- Original fMRI signals are standardized through z-scoring

- K-order time series are computed as element-wise products of k+1 z-scored time series

- Each resulting k-order time series is assigned a sign based on parity rules: positive for fully concordant group interactions, negative for discordant interactions

- For each timepoint, all instantaneous k-order time series are encoded into a weighted simplicial complex

- Violating triangles are identified when the weight of a triangular simplex exceeds what would be expected from its constituent edges [12]

This approach enables researchers to move beyond traditional pairwise connectivity models and capture the rich higher-order organizational structure of complex systems like the human brain.

Experimental Protocols for Higher-Order Topological Analysis

fMRI Data Analysis Protocol

Recent research utilizing higher-order topological indicators has employed sophisticated experimental protocols, primarily analyzing fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) [5] [12]. The standard methodology involves:

- Data Acquisition: Using resting-state and task-based fMRI data from approximately 1,000 healthy adults (aged 22-36) acquired via 3T Siemens Prisma scanners [5]

- Preprocessing: Applying minimal preprocessing pipelines including gradient distortion correction, motion correction, and non-linear registration to MNI152 standard space [5]

- Signal Processing: Regressing out effects of head motion, temporal trends, cerebrospinal fluid signals, white matter signals, and global signals, followed by bandpass filtering (0.01-0.08 Hz) [5]

- Parcellation: Utilizing brain atlases such as the Schaefer 200 atlas with 200 regions of interest divided into 7 brain networks [5]

Topological Feature Extraction Protocol

The core topological analysis follows this workflow:

Time-Delay Embedding: Reconstructing one-dimensional time series into high-dimensional state space using mutual information method for optimal time delay and false nearest neighbor method for embedding dimension (typically dimension 4 and time delay 35 for fMRI) [5]

Simplicial Complex Construction: Building Vietoris-Rips complexes from the point cloud data at multiple scales [5]

Persistent Homology Computation: Applying 0-dimensional (H0) and 1-dimensional (H1) persistent homology analysis using computational tools like Giotto-TDA toolkit [5]

Persistence Landscape Transformation: Converting persistence diagrams to functional representations using persistence landscape (PL) method for statistical analysis [5]

Higher-Order Indicator Extraction: Calculating violating triangles and other higher-order indicators from the weighted simplicial complexes [12]

Figure 2: Higher-order topological feature extraction from fMRI data.

Comparative Performance in Task Decoding

Task Decoding Performance Metrics

Research has demonstrated that higher-order topological indicators, including violating triangles, significantly enhance task decoding performance compared to traditional methods. Evaluation typically uses the Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) measure, which quantifies similarity between community partitions identified in recurrence plots, where 0 indicates poor task decoding and 1 indicates perfect task identification [12].

Studies have constructed recurrence plots by concatenating resting-state fMRI data with task fMRI data, then computing time-time correlation matrices for various local indicators including BOLD signals, edge signals, triangle signals, and scaffold signals [12]. These matrices are binarized at the 95th percentile of their distributions, followed by community detection using the Louvain algorithm to identify timings corresponding to task and rest blocks [12].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Task decoding performance comparison of different topological indicators

| Topological Indicator | Task Decoding Performance (ECS) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| BOLD Signals (Traditional) | Baseline | Standard approach, well-established |

| Edge Signals (Pairwise) | Moderate improvement over BOLD | Captures pairwise functional connectivity |

| Triangle Signals (Higher-Order) | Significant improvement | Identifies violating triangles and genuine 3-way interactions |

| Scaffold Signals (Higher-Order) | Strong improvement | Highlights important connections in higher-order co-fluctuation landscape |

Higher-order approaches, particularly those utilizing triangle signals and homological scaffolds, greatly enhance the ability to decode dynamics between various tasks compared to traditional node and edge-based methods [12]. This improved performance stems from their capacity to capture interactions that involve three or more brain regions simultaneously, which traditional pairwise models miss entirely [12].

Interestingly, while local higher-order indicators show significant advantages, similar indicators defined at the global scale do not consistently outperform traditional pairwise methods, suggesting a localized and spatially-specific role of higher-order functional brain coordination [12].

Table 2: Essential resources for topological data analysis in neuroscience research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Data | Human Connectome Project (HCP) dataset [5] [12] | Provides standardized, high-quality fMRI data for methodological development and validation |

| Computational Tools | Giotto-TDA toolkit [5] | Implements persistent homology and other TDA methods with user-friendly interfaces |

| Brain Parcellation | Schaefer 200 atlas [5] | Divides cortex into 200 regions of interest for consistent spatial analysis |

| Analysis Frameworks | Topological pipeline for higher-order interactions [12] | Specialized framework for extracting violating triangles and other HOIs from fMRI data |

| Performance Metrics | Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) [12] | Quantifies task decoding accuracy in community partitions of recurrence plots |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The application of higher-order topological indicators extends beyond basic neuroscience to potentially transform drug discovery and development. As the pharmaceutical industry increasingly focuses on personalized and genetic treatment approaches [16], the ability to precisely map individual differences in brain function using topological methods could enable more targeted therapeutic interventions.

Topological biomarkers derived from persistent homology analysis have demonstrated high test-retest reliability and accurate individual identification across sessions [5], suggesting their potential utility as functional fingerprints in clinical trials. Furthermore, the association between topological brain patterns and behavioral traits [5] provides a pathway for connecting neural mechanisms to clinical outcomes.

In the context of first-in-class drug development [17] [18], topological methods could offer novel biomarkers for target engagement and patient stratification, particularly for neurological and psychiatric disorders where traditional biomarkers have shown limitations. The ability of higher-order topological indicators to capture individualized brain dynamics [5] aligns with the industry's shift toward personalized medicine and targeted therapies.

Persistent homology and higher-order topological indicators like violating triangles represent a paradigm shift in analyzing complex biological systems. By moving beyond traditional pairwise connectivity models, these approaches capture the rich, multi-dimensional interactions that characterize real-world biological complexity. The superior task decoding performance of higher-order indicators, as demonstrated in fMRI studies, highlights their potential to reveal organizational principles that remain hidden to conventional methods.

For researchers and drug development professionals, incorporating topological data analysis into their analytical toolkit offers a powerful approach to unravel complex relationships in high-dimensional data, from brain function to drug response patterns. As topological methods continue to evolve and become more accessible, they are poised to play an increasingly important role in personalized medicine and targeted therapeutic development.

Emerging evidence in neuroscience demonstrates that brain function relies on complex interactions extending beyond simple pairwise connections between regions. This guide compares traditional functional connectivity models with novel higher-order approaches, focusing on their performance in decoding cognitive tasks. We synthesize recent findings showing that higher-order topological indicators significantly outperform traditional methods in task classification, individual identification, and behavior prediction. Experimental data from the Human Connectome Project and related studies provide robust support for integrating these advanced analytical frameworks into neuroimaging research and drug development pipelines.

Traditional models of human brain activity represent it as a network of pairwise interactions between brain regions, known as functional connectivity (FC) [12]. This approach defines weighted edges as statistical dependencies between time series recordings from different brain regions, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). However, this model is fundamentally limited by its underlying hypothesis that interactions between nodes are strictly pairwise [12].

Higher-order interactions (HOIs) represent a paradigm shift, capturing relationships that involve three or more brain regions simultaneously [12]. Mounting evidence at both micro- and macro-scales suggests these complex spatiotemporal dynamics are essential for fully characterizing human brain function [12]. In simple dynamical systems, higher-order interactions can exert profound qualitative shifts in a system's dynamics, suggesting methods relying on pairwise statistics alone might miss significant information present only in joint probability distributions [12].

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols for Higher-Order Analysis

Topological Pipeline for Higher-Order Inference

A recent topological approach combines topological data analysis and time series analysis to reveal instantaneous higher-order patterns in fMRI data [12]. This protocol involves four key steps:

- Signal Standardization: The N original fMRI signals are standardized through z-scoring [12].

- k-Order Time Series Computation: All possible k-order time series are computed as the element-wise products of k+1 z-scored time series, which are further z-scored for cross-k-order comparability. These represent the instantaneous co-fluctuation magnitude of associated (k+1)-node interactions (edges, triangles) [12].

- Simplicial Complex Construction: For each timepoint t, all instantaneous k-order time series are encoded into a weighted simplicial complex, with each simplex's weight defined as the value of the associated k-order time series at that timepoint [12].

- Topological Indicator Extraction: Computational topology tools analyze the simplicial complex weights to extract global indicators (hyper-coherence, landscape contributions) and local indicators (violating triangles, homological scaffolds) [12].

Contrast Subgraph Extraction for Group Comparisons

For identifying altered functional connectivity patterns in clinical populations, contrast subgraph methodology provides a mesoscopic approach [19]:

- Network Construction: Compute standard functional connectivity matrices from preprocessed fMRI timeseries using Pearson's correlation coefficient, then sparsify using algorithms like SCOLA to obtain individual sparse weighted networks [19].

- Summary Graph Formation: For each cohort, combine the group's functional networks into a single summary graph, compressing common peculiarities of multiple networks into a single observation [19].

- Difference Graph Calculation: Combine two summary graphs into a difference graph whose edge weights equal the difference between the two summary graphs' weights [19].

- Optimization and Bootstrapping: Solve an optimization problem on the difference graph to identify contrast subgraphs - sets of regions that maximize density difference between groups. Iterate through bootstrapping to obtain a family of contrast subgraphs [19].

- Statistical Validation: Use Frequent Itemset Mining techniques to select statistically significant nodes from candidate contrast subgraphs [19].

Performance Comparison: Higher-Order vs. Traditional Methods

Task Decoding Capabilities

Higher-order approaches substantially improve dynamic decoding between various tasks compared to traditional pairwise methods [12]. In studies using fMRI data from 100 unrelated subjects from the Human Connectome Project, local higher-order indicators extracted from instantaneous topological descriptions outperformed traditional node and edge-based methods in task decoding [12].

Table 1: Task Decoding Performance Using Element-Centric Similarity (ECS)

| Method | Signal Type | Task Decoding Performance (ECS) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOLD Signals | Regional activity | Baseline | Traditional measure |

| Edge Time Series | Pairwise connectivity | Moderate improvement | Standard functional connectivity |

| Violating Triangles | Higher-order interactions | Significant improvement | Captures triple interactions beyond pairwise |

| Homological Scaffolds | Mesoscopic structures | Significant improvement | Highlights cyclic connectivity patterns |

Individual Identification and Behavioral Prediction

Higher-order methods improve individual identification of unimodal and transmodal functional subsystems and significantly strengthen associations between brain activity and behavior [12]. The homological scaffold assesses edge relevance toward mesoscopic topological structures within the higher-order co-fluctuation landscape, providing a weighted graph that highlights connection importance in overall brain activity patterns [12].

Table 2: Method Performance Across Research Applications

| Research Application | Pairwise Connectivity Performance | Higher-Order Connectivity Performance | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Block Identification | Moderate (Baseline ECS) | High (Significantly improved ECS) | Strong [12] |

| Individual Fingerprinting | Limited discrimination | Improved functional subsystem identification | Strong [12] |

| Behavior-Brain Association | Moderate correlations | Significantly strengthened associations | Strong [12] |

| Clinical Group Classification | Variable reports | Contrast subgraphs classify ASD vs. TD (80% accuracy children) | Moderate [19] |

Table 3: Essential Materials for Higher-Order Connectomics Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Datasets | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [12] | Provides high-quality fMRI data for methodology development and validation | 100 unrelated subjects for higher-order method validation |

| Clinical Datasets | ABIDE dataset [19] | Enables study of functional connectivity alterations in clinical populations | Resting-state fMRI from 57 ASD and 80 TD males |

| Computational Libraries | Topological Data Analysis tools [12] | Infers higher-order interactions from neuroimaging signals | Construction and analysis of weighted simplicial complexes |

| Sparsification Algorithms | SCOLA algorithm [19] | Reduces dense connectivity matrices to sparse networks for analysis | Creates individual sparse weighted networks (density <0.1) |

| Network Comparison Tools | Contrast subgraph extraction [19] | Identifies maximally different connectivity patterns between groups | Detects hyper/hypo-connectivity in ASD vs. neurotypical |

| Color Visualization Tools | ColorBrewer [20] | Generates appropriate color palettes for data visualization | Creates sequential, diverging, and qualitative palettes |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Strengths

Table 4: Methodological Strengths and Limitations Comparison

| Analytical Aspect | Pairwise Functional Connectivity | Higher-Order Topological Approaches | Contrast Subgraph Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Traditional network theory | Topological data analysis, simplicial complexes | Network comparison, optimization theory |

| Spatial Specificity | Global and local connections | Local topological signatures show superior performance | Mesoscopic-scale structures |

| Clinical Applicability | Mixed, conflicting reports of hyper/hypo-connectivity | Emerging evidence in consciousness states, age effects | Reconciles hyper/hypo-connectivity findings in ASD |

| Computational Complexity | Lower | Higher due to combinatorial explosion | Moderate, depends on bootstrapping iterations |

| Temporal Resolution | Static or dynamic sliding window | Instantaneous co-fluctuation patterns | Typically static group-level differences |

| Developmental Insights | Local to distributed shift with maturation [21] | Potential for enhanced tracking of brain maturation | Captures evolving hyper/hypo-connectivity across age |

Higher-order approaches to functional brain connectivity represent a significant advancement over traditional pairwise methods. The experimental evidence synthesized in this guide demonstrates their superior performance in task decoding, individual identification, and behavior prediction. The topological pipeline for higher-order inference and contrast subgraph methods for group comparisons provide robust methodological frameworks for detecting these complex patterns.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these approaches offer more sensitive biomarkers for tracking brain states, disease progression, and treatment response. The ability of higher-order methods to capture meaningful neural signatures that remain hidden to traditional analyses positions them as essential tools in next-generation neuroimaging research.

Building a Higher-Order Decoding Pipeline: From Data to Biomarkers

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing for Topological Feature Extraction

In the evolving field of neuroscience and drug discovery, the ability to accurately decode cognitive tasks or predict biomolecular interactions hinges on the quality of extracted features from complex data. Traditional analytical models often represent systems as networks of pairwise interactions, limiting their capacity to capture the rich, higher-order structures that characterize biological processes. Higher-order interactions (HOIs)—relationships involving three or more nodes simultaneously—are increasingly recognized as crucial for understanding the spatiotemporal dynamics of the human brain and molecular systems [12]. Going beyond traditional pairwise connectivity, topological data analysis (TDA) and higher-order topological indicators have emerged as powerful frameworks that significantly enhance task decoding performance, individual identification, and the association between brain activity and behavior [12] [6]. This guide objectively compares the performance of topological feature extraction pipelines against traditional methods, providing a detailed overview of data acquisition requirements, preprocessing methodologies, and experimental protocols essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Data Acquisition for Topological Analysis

The acquisition of high-quality, temporally and spatially rich data is the foundational step for effective topological feature extraction. Data requirements vary significantly across applications, from neuroimaging to drug discovery.

Table 1: Data Acquisition Specifications Across Domains

| Application Domain | Data Modality & Source | Key Specifications | Sample Size (Typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Brain Function | fMRI (Human Connectome Project) [12] | 100 unrelated subjects; 119 brain regions (100 cortical, 19 sub-cortical); resting-state and task-based fMRI | 100+ subjects |

| Neural Spike Decoding | Neuropixel recordings (Allen Brain Institute) [22] | Spike responses from hundreds of neurons in visual cortex and subcortical regions; high spatiotemporal resolution | Hundreds of neurons |

| Breast Cancer Detection | Mammography images (INbreast dataset) [23] | 7,632 images (2,520 benign, 5,112 malignant); 224x224 pixel resolution; DICOM format | Thousands of images |

| Drug-Target Interaction | Chemical-protein networks (BioSNAP, Human) [24] | SMILES strings for drugs; amino acid sequences for proteins; interaction data from literature | Varies by dataset |

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition

For studying brain function, functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) is a primary data source. The Human Connectome Project (HCP) provides a benchmark dataset, offering fMRI time series from 100 unrelated subjects during both resting-state and various tasks [12]. The data is typically preprocessed and mapped onto a cortical parcellation of 119 brain regions, creating a high-dimensional time series for each region. This dense sampling is critical for constructing accurate functional connectivity networks and inferring higher-order interactions, as it captures dynamic co-fluctuation patterns across the brain.

Molecular and Chemical Data Acquisition

In drug discovery, data acquisition involves compiling heterogeneous information. The TCoCPIn framework for chemical-protein interactions utilizes drug information represented as SMILES strings or molecular formulas, aggregated from experimental data, computational predictions, and literature mining [25]. Protein data includes amino acid sequences or contact maps. Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, such as named entity recognition and dependency parsing, are employed to extract interaction information between chemicals and proteins from biomedical literature (e.g., PubMed), constructing comprehensive interaction networks [25].

Preprocessing Workflows for Topological Feature Extraction

Raw data must be transformed into structured formats amenable to topological analysis. Preprocessing pipelines are tailored to the data modality and the specific topological features of interest.

Preprocessing for Higher-Order Brain Connectivity

A prominent topological method for fMRI data involves a four-step pipeline to reveal instantaneous higher-order patterns [12].

Step 1: Signal Standardization. The original fMRI signals from N brain regions are standardized through z-scoring to ensure comparability [12].

Step 2: k-Order Time Series Computation. All possible k-order time series are computed as the element-wise products of (k+1) z-scored time series. For example, a 1-order time series corresponds to an edge (pairwise interaction), while a 2-order time series corresponds to a triangle (three-way interaction). These product time series are also z-scored. A sign is assigned at each timepoint based on parity: positive for fully concordant group interactions and negative for discordant ones [12].

Step 3: Simplicial Complex Encoding. At each time point t, all instantaneous k-order co-fluctuation time series are encoded into a single mathematical object—a weighted simplicial complex. The weight of each simplex (e.g., edge, triangle) is the value of its associated k-order time series at time t [12].

Step 4: Topological Indicator Extraction. Computational topology tools are applied to the simplicial complex to extract indicators. Local indicators include violating triangles (Δv) and homological scaffolds, which highlight higher-order co-fluctuations and the importance of edges in mesoscopic topological structures, respectively [12].

Preprocessing for Neural Spike Train Decoding

Decoding spatial information from head direction or grid cells requires capturing the higher-order firing structure of neuron ensembles. The Simplicial Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (SCRNN) framework uses a specific preprocessing pipeline [26].

Preprocessing: Neural spikes are first binned to generate a binarized spike count matrix. A key topological step follows: within each time bin, every set of simultaneously active cells is connected by a simplex in a simplicial complex. This construction does not require prior knowledge of neural connectivity and automatically captures the higher-order functional relationships between neurons [26].

Feature Extraction and Modeling: The sequence of simplicial complexes is fed into simplicial convolutional layers for feature extraction, leveraging the higher-order connectivity. The extracted features are then processed by a recurrent neural network (RNN) to model the temporal dependencies and decode variables like head direction or animal location [26].

Experimental Protocols & Performance Comparison

Protocol: Task Decoding from fMRI Data

This protocol is based on the comprehensive analysis of HCP data [12].

- Objective: To compare the task-decoding performance of higher-order topological indicators against traditional pairwise and node-level methods.

- Data: fMRI time series from 100 HCP subjects, concatenating the first 300 volumes of resting-state data with data from seven tasks.

- Feature Extraction:

- Traditional Methods: N BOLD time series (node-level) and edge time series (pairwise).

- Higher-Order Methods: Triangles (violating triangles, Δv) and scaffold signals (homological scaffold).

- Analysis: For each method, a recurrence plot (time-time correlation matrix) is constructed. These matrices are binarized at the 95th percentile, and the Louvain community detection algorithm is applied to identify temporal communities.

- Evaluation: The Element-Centric Similarity (ECS) measure quantifies how well the community partitions identify task and rest blocks, with 1 indicating perfect identification.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Topological vs. Traditional Features

| Feature Type | Description | Key Performance Metrics | Superior Performance Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Higher-Order Indicators (Triangles, Scaffold) [12] | Capture 3+ node interactions (e.g., violating triangles) | Task decoding (Element-Centric Similarity) | Greatly enhanced dynamic task decoding vs. pairwise |

| Global Higher-Order Indicators (Hyper-coherence) [12] | Quantifies fraction of triplets co-fluctuating beyond pairwise expectation | Task decoding, Individual identification | Did not significantly outperform pairwise methods |

| Persistent Homology (B0 AUC) [6] | Area under the 0-dimension Betti curve from task-based fMRI | Predicting longitudinal behavioral change (Fluid Reasoning) | Predicted longitudinal cognitive decline; mediated effect of age on cognition |

| Topological Features (TDA) + LLMs (Top-DTI) [24] | Persistent homology from protein/drug structures + language model embeddings | AUROC, AUPRC, Sensitivity, Specificity (Drug-Target Interaction) | Outperformed state-of-the-art; AUROC: 0.987 on BioSNAP, 0.983 on Human |

| Simplicial Convolutional RNN (SCRNN) [26] | Simplicial complexes from neural spike trains + RNN | Median Absolute Error (Head Direction, Location Decoding) | Lower error vs. Feedforward, Recurrent, and Graph Neural Networks |

Protocol: Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction

The Top-DTI framework demonstrates the power of integrating topological features with modern deep learning [24].

- Objective: Predict interactions between drug molecules and target proteins.

- Data: Public benchmark datasets BioSNAP and Human.

- Feature Extraction:

- Topological Features: Generated using persistent homology on 2D drug molecular images and protein contact maps.

- Sequence Embeddings: Generated using large language models (LLMs) like MoLFormer for drug SMILES strings and ProtT5 for protein sequences.

- Model Architecture: A feature fusion module dynamically integrates TDA and LLM embeddings. These are processed by a graph neural network (GNN) that models the relationships in the DTI graph.

- Evaluation: Model performance is assessed using Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), sensitivity, and specificity. The model is also tested in a cold-split scenario where drugs or targets in the test set are absent from the training set.

Results: Top-DTI achieved an AUROC of 0.987 on the BioSNAP dataset and 0.983 on the Human dataset, outperforming state-of-the-art methods. The incorporation of topological features alongside LLM embeddings provided a significant performance boost, underscoring the value of integrating structural information [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Resources for Topological Feature Extraction Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Dataset [12] | Provides high-resolution fMRI data for constructing whole-brain functional connectivity and higher-order interaction models. | Benchmarking task decoding algorithms [12] |

| INbreast Dataset [23] | Publicly available mammography image database for developing topological cancer classification models. | Breast cancer detection using persistent homology [23] |

| Allen Brain Observatory [22] | Provides Neuropixel recordings from the mouse visual system, including spike data from hundreds of neurons. | Decoding visual stimuli and head direction from neural activity [26] [22] |

| BioSNAP & Human DTI Datasets [24] | Benchmark datasets for drug-target interaction prediction, containing known interactions between chemicals and proteins. | Training and evaluating Top-DTI and similar models [24] |

| Persistent Homology Software | Computational tools for topological feature extraction. | Generating Betti curves from fMRI [6] or features from molecular graphs [24] |

| Simplicial Complex Libraries [26] | Software for constructing and analyzing simplicial complexes from data. | Building SCRNN models for neural decoding [26] |

The pursuit of decoding complex brain tasks has catalyzed the evolution of neuroimaging techniques capable of capturing the brain's intricate dynamic processes. Within this context, the reconstruction of temporal higher-order interactions (HOIs) from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) time series represents a cutting-edge frontier. These interactions move beyond simple pairwise connections to capture the complex, multi-region dynamics that underpin sophisticated cognitive functions. The broader thesis of this guide is that task decoding performance is significantly enhanced by research into higher-order topological indicators, which provide a more nuanced map of the brain's network architecture. This guide objectively compares the performance of fMRI and fNIRS in reconstructing these temporal HOIs, underpinned by experimental data and detailed methodological protocols.

Neuroimaging Modalities: A Technical Comparison for HOI Research

fMRI and fNIRS are both hemodynamic-based imaging techniques, but their fundamental technical differences directly influence their efficacy for reconstructing temporal higher-order interactions. The following table summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between fMRI and fNIRS technologies.

| Feature | fMRI | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Signal | Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) [27] [28] | Concentration changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) [28] [29] |

| Spatial Resolution | High (millimeter-level); whole-brain coverage including subcortical structures [27] [28] | Low (1-3 cm); restricted to superficial cortical regions [27] [28] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (0.33-2 Hz); limited by slow hemodynamic response [27] | High (often 10 Hz+); can capture rapid hemodynamic fluctuations [27] [30] |

| Portability & Use | Not portable; requires immobile scanner environment [27] [28] | Highly portable; suitable for naturalistic settings and free movement [27] [28] |

| Key Advantage for HOIs | Excellent for mapping the spatial architecture of large-scale networks. | Superior for tracking the fine-grained temporal dynamics of cortical networks. |

Quantitative Performance Data in Task Decoding

The practical performance of fMRI and fNIRS in experimental settings reveals their complementary strengths. Quantitative data from various cognitive and clinical tasks highlight their respective capabilities.

Table 2: Experimental performance data in task decoding and application domains.

| Experimental Task / Domain | fMRI Performance & Findings | fNIRS Performance & Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Execution/Imagery | Provides detailed maps of motor cortex, supplementary motor area (SMA), and subcortical involvement. | Validated against fMRI, fNIRS reliably detects SMA activation with high task sensitivity during both execution and imagery [28]. |

| Semantic Decoding | High spatial resolution allows successful decoding of semantic representations of words and pictures from distributed neural patterns [30]. | fNIRS response patterns can be decoded to identify specific stimulus representations and semantic information, though with lower spatial granularity than fMRI [30]. |

| Naturalistic & Dyadic Settings | Challenging due to sensitivity to motion artifacts and confined scanner environment [27]. | High motion tolerance enables neural synchrony analysis in child-parent dyads and other interactive, naturalistic paradigms [30] [29]. |

| Clinical Populations | Gold standard for localization but can be unsuitable for infants, children, or patients with implants/mobility issues [28]. | High tolerance for movement and insensitivity to metal makes it ideal for infants, children, and various clinical populations [30] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for HOI Reconstruction

Protocol 1: Dynamic Effective Connectivity using Physiologically informed Dynamic Causal Model (P-DCM)

This protocol uses a generative model to infer time-varying effective connectivity from task-based fMRI data, which can serve as a foundation for identifying HOIs [31].

- Data Acquisition: Collect task-based fMRI BOLD time-series using a paradigm that involves changing cognitive conditions (e.g., movie-watching).

- Preprocessing: Perform standard fMRI preprocessing (slice-time correction, motion realignment, normalization, smoothing).

- Region of Interest (ROI) Selection: Define ROIs based on the cognitive hypothesis. Time-series are extracted from these regions.

- Model Specification: Construct a P-DCM model that incorporates a two-state excitatory-inhibitory neuronal model and refined BOLD signal physiology to overcome limitations of earlier DCMs in modeling initial overshoot and post-stimulus undershoot [31].

- Discretization and Recurrent Windowing: Implement a discretized P-DCM (dP-DCM) using Euler's method. Slide overlapping windows (Recurrent Units) across the entire BOLD time-series to capture temporal variations in connectivity strength [31].

- Model Inversion & Parameter Estimation: For each window, perform Bayesian model inversion to estimate the underlying neuronal dynamics and effective connectivity parameters until convergence.

- HOI Inference: The time-varying effective connectivity matrices generated can be analyzed with network analysis tools to quantify higher-order statistics and temporal motifs between multiple brain regions.

Protocol 2: HRfunc Tool for fNIRS-Based Neural Activity Estimation

This protocol details the use of the HRfunc tool to deconvolve fNIRS signals, improving the estimation of latent neural activity for subsequent temporal HOI analysis [29].

- fNIRS Data Acquisition: Set up fNIRS optodes over the cortical areas of interest. Record HbO and HbR concentration changes during an event-related or block-designed task.

- Standard Preprocessing: Process data using tools like Homer2: convert raw light intensity to optical density, perform principal component analysis to reduce non-neural physiological signals, bandpass filter (e.g., 0.01-0.5 Hz), and motion correct [30] [29].

- Channel Stability Analysis: Correlate responses for each stimulus type across blocks for every channel. Select channels with high cross-block correlation for further analysis to increase the signal-to-noise ratio [30].

- Toeplitz Deconvolution with HRfunc:

- First Deconvolution (HRF Estimation): Use Toeplitz deconvolution with Tikhonov regularization to estimate the subject- and channel-specific Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) from the preprocessed hemoglobin signals [29].

- Edge Artifact Removal: Employ the tool's edge expansion process (e.g., +25%) prior to deconvolution and trim the edges post-estimation to remove deconvolution artifacts [29].

- Second Deconvolution (Neural Activity Estimation): Use the estimated HRF to deconvolve the original fNIRS signal, resulting in a time-series of estimated latent neural activity.

- Collaborative HRF Sourcing (Optional): Contribute estimated HRFs to the collaborative HRtree database, or load contextually relevant HRFs from other studies to improve the accuracy of the initial deconvolution step [29].

- Temporal HOI Analysis: Use the deconvolved neural activity time-series to compute time-varying functional connectivity networks. Apply higher-order network analysis to these dynamic networks to reveal multi-node interaction patterns.

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Comparative Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines the overarching computational workflow for reconstructing temporal HOIs, highlighting the parallel paths for fMRI and fNIRS data.

Comparative Workflow for HOI Reconstruction

Temporal HOI Reconstruction Logic

This diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway from neural activity to the reconstruction of higher-order interactions, which is the core objective of the computational workflows.

Pathway to Higher-Order Interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for implementing the described experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational solutions for HOI reconstruction.

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Relevance to HOI Research |

|---|---|---|

| HRfunc Tool [29] | A Python-based tool for estimating subject- and context-specific HRFs and deconvolving latent neural activity from fNIRS signals. | Critical for improving the temporal precision of fNIRS signals, providing a cleaner estimate of neural dynamics for subsequent HOI analysis. |

| Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) [31] | A Bayesian framework for inferring effective connectivity (causal influences) between brain regions from fMRI or fNIRS data. | Allows for the modeling of directed, time-varying interactions between regions, forming the basis for inferring complex HOIs. |

| HRtree Database [29] | A collaborative database using a hybrid tree-hash table structure to store and share probabilistic HRF estimates across brain regions and experimental contexts. | Enables more accurate deconvolution by providing access to a pool of empirically derived HRFs, enhancing the reliability of neural activity estimation. |

| Homer2 Software [30] | A standard MATLAB-based software suite for preprocessing fNIRS data (conversion to optical density, filtering, motion correction). | Provides the essential first steps in preparing raw fNIRS data for advanced analysis, including deconvolution and connectivity modeling. |

| Toeplitz Deconvolution [29] | A linear inversion method using a Toeplitz matrix and Tikhonov regularization to solve for a latent function (e.g., HRF or neural activity) from a convolved signal. | The core mathematical engine within HRfunc for separating the hemodynamic response from the underlying neural signal. |

In the analysis of complex systems—from brain networks to molecular structures—traditional feature engineering often fails to capture the multi-scale organizational principles that govern system behavior. Topological indicators provide a powerful mathematical framework for quantifying these organizational patterns, offering insights that transcend conventional network metrics. Within research on task decoding performance, higher-order topological indicators have emerged as particularly valuable for their ability to characterize both local connectivity patterns and global integration capabilities of complex networks.

The fundamental distinction between local and global topological indicators lies in their scope of analysis. Local indicators focus on node-specific properties and immediate neighborhoods, quantifying characteristics like regional influence and specialized processing. In contrast, global indicators capture system-wide integration patterns, reflecting overall efficiency and information flow across the entire network. A third category, meso-scale indicators, bridges these extremes by examining structural properties at intermediate scales, revealing organizational principles that remain invisible to both purely local and entirely global approaches [32]. This comparative guide examines the performance characteristics of these topological indicator classes, with particular emphasis on their emerging applications in task decoding performance and higher-order topological analysis.

Theoretical Foundations: Classes of Topological Indicators

Local Topological Indicators

Local indicators quantify node-level properties and immediate neighborhood characteristics, serving as proxies for regional influence and specialized processing capabilities. These metrics are computationally efficient and particularly valuable for identifying critical hubs within networks.

- Degree Centrality: The most fundamental local indicator, defined simply as the number of direct connections incident upon a node. In ecological networks, it identifies species with the most trophic relationships [32].

- Clustering Coefficient: Measures the degree to which a node's neighbors connect to each other, quantifying the local "cliquishness" or segregation of a network region [33].

- Betweenness Centrality: Captures a node's importance as a bridge in communication pathways by calculating the fraction of shortest paths that pass through it [32].

Global Topological Indicators

Global indicators characterize system-wide integration capabilities, reflecting how efficiently information can traverse a network as a whole.

- Average Path Length: The average number of steps along the shortest paths between all possible node pairs, reflecting global efficiency of information transfer [34].

- Small-Worldness: A composite property indicating networks that combine high local clustering with short global path lengths, enabling both specialized processing and integrated functionality [33].

- Spectral Distance: Based on eigenvalue spectra of connectivity matrices, this metric captures large-scale reorganization and shifts in brain networks [35].

Higher-Order Topological Indicators

Going beyond pairwise interactions, higher-order topological indicators capture simultaneous interactions between three or more network elements, revealing organizational principles invisible to traditional graph-based approaches.

- Persistent Homology: A computational topology approach that identifies connective components across different connectivity thresholds, quantifying the "shape" of brain network connectivity beyond simple edge pairings [6].

- Hyper-Coherence: Quantifies the fraction of higher-order triplets that co-fluctuate more than expected from corresponding pairwise co-fluctuations, identifying "violating triangles" whose activity cannot be explained by pairwise connections alone [12].

- Homological Scaffolds: Weighted graphs that highlight the importance of certain connections in overall brain activity patterns when considering topological structures like 1-dimensional cycles [12].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Local vs. Global Indicators in Task Decoding

Quantitative Comparison of Indicator Performance

Table 1: Performance characteristics of topological indicator classes in task decoding applications

| Indicator Class | Computational Complexity | Task Decoding Accuracy | Individual Identification | Behavior Prediction Power | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Indicators | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Limited | Identifies critical hubs, computationally efficient, interpretable |