Beyond Single Studies: A Framework for Replicable Consensus Models in Biomedical Validation Cohorts

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on ensuring the replicability of consensus prediction models across diverse validation cohorts.

Beyond Single Studies: A Framework for Replicable Consensus Models in Biomedical Validation Cohorts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on ensuring the replicability of consensus prediction models across diverse validation cohorts. It explores the foundational principles of the replication crisis in science, presents methodological frameworks for building robust multi-model ensembles, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous standards for external validation and comparative performance analysis. Drawing on recent advances in machine learning and lessons from large-scale replication projects, the content offers practical strategies to enhance the reliability, generalizability, and clinical applicability of predictive models in biomedical research.

The Replicability Crisis and the Critical Need for Consensus Models

Defining Replicability and Reproducibility in Computational Biomedicine

In computational biomedicine, where research increasingly informs regulatory and clinical decisions, the precise concepts of reproducibility and replicability form the bedrock of scientific credibility. While often used interchangeably in general discourse, these terms represent distinct validation stages in the scientific process. Reproducibility refers to obtaining consistent results using the same input data, computational steps, methods, and conditions of analysis, essentially verifying that the original analysis was conducted correctly. Replicability refers to obtaining consistent results across studies aimed at answering the same scientific question, each of which has obtained its own data [1].

The importance of this distinction has been formally recognized by major scientific bodies. At the request of Congress, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) conducted a study to evaluate these issues, highlighting that reproducibility is computationally focused, while replicability addresses the robustness of scientific findings [2] [1]. This guide explores these concepts within computational biomedicine, providing a framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to enhance the rigor of their work.

Defining the Framework: Reproducibility vs. Replicability

Terminological Challenges and Consensus

The scientific community has historically used the terms "reproducibility" and "replicability" in inconsistent and even contradictory ways across disciplines [2]. As identified in the NASEM report, this confusion primarily stems from three distinct usage patterns:

- Usage A: The terms are used with no distinction between them.

- Usage B1: "Reproducibility" refers to using the original researcher's data and code to regenerate results, while "replicability" refers to a researcher collecting new data to arrive at the same scientific findings.

- Usage B2: "Reproducibility" refers to independent researchers arriving at the same results using their own data and methods, while "replicability" refers to a different team arriving at the same results using the original author's artifacts [2].

The NASEM report provides clarity by establishing standardized definitions, which are adopted throughout this guide and summarized in the table below.

Comparative Definitions

| Concept | Core Definition | Key Question | Primary Goal | Typical Inputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | Obtaining consistent computational results using the same input data, computational steps, methods, code, and conditions of analysis [1]. | "Can we exactly recompute the reported results from the same data and code?" | Verify the computational integrity and transparency of the original analysis [3]. | Original data + original code/methods |

| Replicability | Obtaining consistent results across studies aimed at the same scientific question, each of which has obtained its own data [1]. | "Do the findings hold up when tested on new data or in a different context?" | Confirm the robustness, generalizability, and validity of the scientific finding [3]. | New data + similar methods |

This relationship is foundational. Reproducibility is a prerequisite for replicability; if a result cannot be reproduced, there is little basis for evaluating its validity through replication [4].

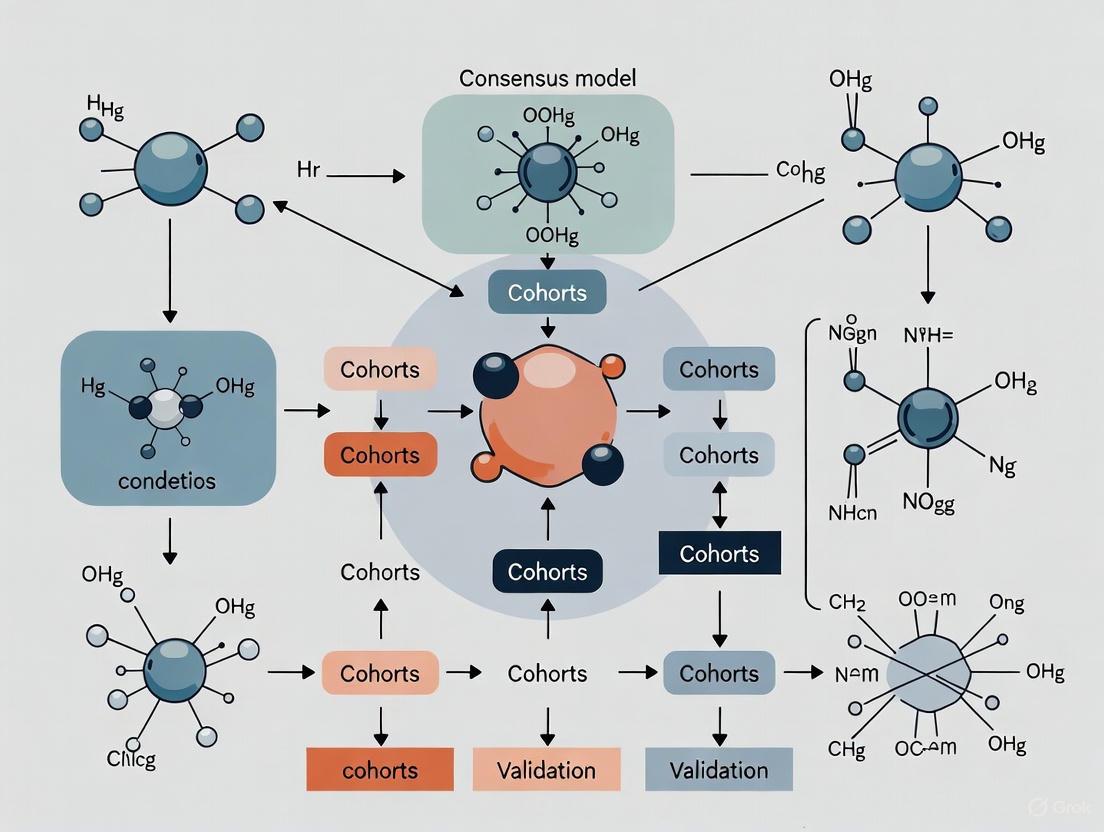

The Reproducibility and Replicability Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the typical sequential workflow for validating computational findings, from initial discovery through reproduction and replication, highlighting the distinct inputs and goals at each stage.

Case Study: Replicability in Brain Signature Research

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2023 study on "brain signatures of cognition" provides a robust example of replicability in computational biomedicine [5]. The researchers aimed to develop and validate a data-driven method for identifying key brain regions associated with specific cognitive functions.

The experimental workflow involved a multi-cohort, cross-validation design, which can be broken down into the following key stages:

- Discovery of Consensus Signatures: In each of two independent discovery cohorts, researchers repeatedly (40 times) randomly selected subsets of 400 participants. For each subset, they computed associations between regional brain gray matter thickness and two behavioral domains: neuropsychological and everyday cognition memory. They then generated spatial overlap frequency maps from these iterations and defined the most frequently associated regions as "consensus" signature masks [5].

- Validation of Replicability: The core of the replicability test was performed using completely separate validation datasets that were not used in the discovery phase. The researchers evaluated whether the consensus signature models derived in the discovery phase showed consistent model fits and maintained their explanatory power for predicting behavioral outcomes in the new cohorts. The analysis compared the performance of these data-driven signature models against other theory-based models [5].

Key Quantitative Findings

The study successfully demonstrated a high degree of replicability, a critical step for establishing these brain signatures as robust measures.

| Validation Metric | Finding | Implication for Replicability |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Convergence | Convergent consensus signature regions were identified across cohorts [5]. | The brain-behavior relationships identified were not flukes of a single sample. |

| Model Fit Correlation | Consensus signature model fits were "highly correlated" across 50 random subsets of each validation cohort [5]. | The predictive model itself was stable and reliable when applied to new data from similar populations. |

| Explanatory Power | Signature models "outperformed other commonly used measures" in full-cohort comparisons [5]. | The replicable models provided a superior explanation of the cognitive outcomes compared to existing approaches. |

This study exemplifies the "replicability consensus model fits validation cohorts research" context, moving beyond a single discovery dataset to demonstrate that the findings are stable and generalizable.

Case Study: Reproducibility in Real-World Evidence

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A large-scale 2022 study in Nature Communications systematically evaluated the reproducibility of 150 real-world evidence (RWE) studies used to inform regulatory and coverage decisions [4]. These studies analyze clinical practice data to assess the effects of medical products.

The reproduction protocol was designed to be independent and blinded:

- Study Identification: A systematic, random sample of 250 RWE studies fitting pre-specified parameters was identified.

- Independent Reproduction: For 150 of these studies, researchers independently attempted to reproduce the study population and primary outcome findings. This was done using the same underlying healthcare databases as the original authors.

- Method Application: The reproduction team applied the methods described in the original papers, appendices, and other public materials.

- Blinded Assumptions: When study parameters were not fully reported, the reproduction team made informed assumptions while blinded to the original study's findings to avoid bias [4].

Key Quantitative Findings on Reproducibility

The results provide a unique, large-scale insight into the state of reproducibility in the field.

| Reproduction Aspect | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Effect Size Correlation | Original and reproduction effect sizes were strongly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.85) [4]. | Indicates a generally strong but imperfect level of reproducibility across a large number of studies. |

| Relative Effect Magnitude | Median relative effect (e.g., HR~original~/HR~reproduction~) = 1.0 [IQR: 0.9, 1.1], Range: [0.3, 2.1] [4]. | The central tendency was excellent, but a subset of results showed significant divergence. |

| Population Size Reproduction | Relative sample size (original/reproduction) median = 0.9 [IQR: 0.7, 1.3] [4]. | For 21% of studies, the reproduced cohort size was less than half or more than double the original, highlighting reporting ambiguities. |

| Clarity of Reporting | The median number of methodological categories requiring assumptions was 4 out of 6 for comparative studies [4]. | Incomplete reporting of key parameters (e.g., exposure duration algorithms, covariate definitions) was the primary barrier to perfect reproducibility. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for R&R

Achieving reproducibility and replicability requires more than just careful analysis; it depends on a ecosystem of tools and practices. The table below details key "research reagent solutions" essential for robust computational research in biomedicine.

| Tool Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Role in Enhancing R&R |

|---|---|---|

| Data & Model Standards | MIBBI (Minimum Information for Biological and Biomedical Investigations) checklists [6], BioPAX (pathway data), PSI-MI (proteomics) [6]. | Standardizes data and model reporting, enabling other researchers to understand, reuse, and replicate the components of a study. |

| Version-Controlled Code & Data | Public sharing of analysis code and data via repositories (e.g., GitHub, Zenodo) [2] [6]. | The fundamental requirement for reproducibility, allowing others to verify the computational analysis. |

| Declarative Modeling Languages | Standardized model description languages (e.g., SBML, CellML) [6]. | Facilitates model sharing and reuse across different simulation platforms, aiding both reproducibility and replicability. |

| Workflow Management Systems | Galaxy [6], Workflow4Ever project [6]. | Captures and shares the entire analytical pipeline, reducing "in-house script" ambiguity and ensuring reproducibility. |

| Software Ontologies | Software Ontology (SWO) for describing software tasks and data flows [6]. | Helps clarify if the same scientific question is being asked when different software tools are used, supporting replicability. |

In computational biomedicine, reproducibility (using the same data and methods) and replicability (using new data and similar methods) are not interchangeable concepts but are complementary pillars of rigorous and credible science. The consensus, as detailed by the National Academies, provides a clear framework for the field [2] [1]. As evidenced by the case studies, achieving these standards requires a concerted effort involving precise methodology, transparent reporting, and the adoption of shared tools and practices. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorously demonstrating both reproducibility and replicability is paramount for building a reliable evidence base that can confidently inform clinical and regulatory decisions.

The credibility of scientific research across various disciplines has been fundamentally challenged by what is now known as the "replicability crisis." This crisis emerged from numerous high-profile failures to reproduce landmark studies, particularly in psychology and medicine, prompting a systemic reevaluation of research practices. In response, the scientific community has initiated large-scale, collaborative projects specifically designed to empirically assess the reproducibility and robustness of published findings. These projects systematically re-test key findings using predefined methodologies, often in larger, more diverse samples, and with greater statistical power than the original studies. The emergence of these projects represents a paradigm shift toward prioritizing transparency, rigor, and self-correction in science. This guide objectively compares the protocols and outcomes of major replication efforts across psychology and medicine, framing the results within a broader thesis on replicability consensus model fits validation cohorts research. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these findings is crucial for designing robust studies, interpreting the published literature, and developing reproducible and useful measures for modeling complex biological and behavioral domains [7].

Comparative Analysis of Large-Scale Replication Projects

Large-scale replication initiatives have now been conducted across multiple scientific fields, providing a quantitative basis for comparing replicability. The table below summarizes the objectives and key findings from several major projects.

Table 1: Overview of Large-Scale Replication Projects

| Project Name | Field/Topic | Key Finding/Objective | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility Project: Psychology [8] | Psychology | A large-scale collaboration to replicate 100 experimental and correlational studies published in three psychology journals. | Completed |

| Many Labs 1-5 [8] | Psychology | A series of projects investigating the variability in replicability of specific effects across different samples and settings. | Completed |

| Reproducibility Project: Cancer [8] | Medicine (Preclinical) | Focused on replicating important results from preclinical cancer biology studies. | Completed |

| REPEAT Initiative [4] [8] | Healthcare (RWE) | A systematic evaluation of the reproducibility of real-world evidence (RWE) studies used to inform regulatory and coverage decisions. | Completed |

| CORE [8] | Judgment and Decision Making | Replication studies in the field of judgment and decision-making. | Ongoing |

| Many Babies 1 [8] | Developmental Psychology | A collaborative effort to replicate foundational findings in infant cognition and development. | Ongoing |

| Sports Sciences Replications [8] | Sports Sciences | A centre dedicated to replicating findings in the field of sports science. | Ongoing |

The outcomes of these projects reveal a spectrum of replicability. In the Reproducibility Project: Psychology, only 36% of the replications yielded significant results, and the effect sizes of the replicated studies were on average half the magnitude of the original effects [8]. This contrasts with findings from the REPEAT Initiative in healthcare, which demonstrated a stronger correlation between original and reproduced results. In REPEAT, which reproduced 150 RWE studies, the original and reproduction effect sizes were positively correlated (Pearson’s correlation = 0.85). The median relative magnitude of effect (e.g., hazard ratio~original~/hazard ratio~reproduction~) was 1.0, with an interquartile range of [0.9, 1.1] [4]. This suggests that while the majority of RWE results were closely reproduced, a subset showed significant divergence, underscoring that reproducibility is not guaranteed even in data-rich observational fields.

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Replication Efforts

Protocol: The "REPEAT Initiative" for Real-World Evidence Validation

The REPEAT Initiative provides a rigorous methodology for assessing the reproducibility of RWE studies, which are critical for regulatory and coverage decisions in drug development [4].

- Aim: To evaluate the independent reproducibility of 150 published RWE studies using the same healthcare databases as the original investigators.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Systematic Sampling: A large, random sample of RWE studies fitting pre-specified parameters was systematically identified.

- Blinded Reproduction: Reproduction teams, blinded to the original studies' results, attempted to reconstruct the study population and analyze the primary outcome by applying the methods described in the original publications and appendices.

- Assumption Logging: For study parameters that were not explicitly reported (e.g., detailed algorithms for defining exposure duration or covariate measurement), the reproduction team documented and made informed assumptions. This process directly tested the clarity of reporting.

- Outcome Comparison: The reproduced population sizes, baseline characteristics, and outcome effect sizes (e.g., hazard ratios) were quantitatively compared to the original published results.

- Key Metrics:

- Relative sample size (original/reproduction).

- Difference in prevalence of baseline characteristics (original—reproduction).

- Relative magnitude of effect (e.g., hazard ratio~original~/hazard ratio~reproduction~).

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the REPEAT Initiative's validation process.

Protocol: Brain Signature Validation using Consensus Model Fits in Validation Cohorts

Research in neuroscience has developed sophisticated methods for creating and validating brain signatures of cognition, which serve as a prime example of replicability consensus model fits validation cohorts research [7].

- Aim: To derive and validate robust, data-driven brain signatures (e.g., of episodic memory) that replicate across independent cohorts, moving beyond theory-driven approaches.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Discovery in Multiple Subsets: In discovery cohorts (e.g., n=578 from UCD and n=831 from ADNI 3), regional brain gray matter thickness associations with a behavioral outcome (e.g., neuropsychological memory) are computed not once, but in 40 randomly selected discovery subsets of size 400. This step leverages multiple discovery set generation to enhance robustness.

- Consensus Mask Generation: Spatial overlap frequency maps are generated from these multiple discovery runs. Regions that are consistently selected as significant across the majority of subsets are defined as a "consensus" signature mask.

- Validation in Separate Cohorts: The derived consensus signature is then applied to completely separate validation cohorts (e.g., n=348 from UCD and n=435 from ADNI 1) that were not used in the discovery phase.

- Model Fit Evaluation: The replicability of the consensus model's fit to the behavioral outcome is evaluated in 50 random subsets of each validation cohort. Its explanatory power is compared against competing theory-based models.

- Key Metrics:

- Spatial convergence of consensus signature regions.

- Correlation of consensus signature model fits across validation subsets.

- Explanatory power (e.g., R²) compared to other models.

The multi-cohort, multi-validation design of this protocol is captured in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Replication Research

Successful replication and validation research relies on a set of key "reagents" or resources beyond traditional laboratory materials. The following table details these essential components for researchers designing or executing replication studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Replication and Validation Studies

| Item/Resource | Function in Replication Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Cohorts | Independent datasets, separate from discovery cohorts, used to test the robustness and generalizability of a model or finding. | Used in brain signature research to evaluate if a model derived in one population predicts outcomes in another [7]. |

| High-Quality Healthcare Databases | Large, longitudinal datasets from clinical practice used to generate and test Real-World Evidence (RWE). | The REPEAT Initiative used such databases to reproduce study findings on treatment effects [4]. |

| Consensus Model Fits | A statistical approach that aggregates results from multiple models or subsets to create a more robust and reproducible final model. | Used to define robust brain signatures by aggregating features consistently associated with an outcome across many discovery subsets [7]. |

| Standardized Reporting Guidelines | Frameworks (e.g., CONSORT, STROBE) that improve methodological transparency by ensuring all critical design and analytic parameters are reported. | Lack of adherence to such guidelines was a key factor leading to irreproducible RWE studies, as critical parameters were missing [4]. |

| Pre-registration Platforms | Public repositories (e.g., OSF, ClinicalTrials.gov) where research hypotheses and analysis plans are documented prior to data collection. | Mitigates bias and distinguishes confirmatory from exploratory research, a core practice in many large-scale replication projects [8]. |

Quantitative Results from Replication Validations

The outcomes of large-scale replication projects provide hard data on the state of reproducibility. The following table synthesizes key quantitative results from major efforts, offering a clear comparison of replicability across fields.

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes from Major Replication Projects

| Project | Primary Quantitative Outcome | Result Summary | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| REPEAT Initiative (RWE) [4] | Correlation between original and reproduced effect sizes. | Pearson’s correlation = 0.85. | Strong positive relationship with room for improvement. |

| REPEAT Initiative (RWE) [4] | Relative magnitude of effect (Original/Reproduction). | Median: 1.0; IQR: [0.9, 1.1]; Range: [0.3, 2.1]. | Majority of results closely reproduced, but a subset diverged significantly. |

| REPEAT Initiative (RWE) [4] | Relative sample size (Original/Reproduction). | Median: 0.9 (Comparative), 0.9 (Descriptive); IQR: [0.7, 1.3]. | For 21% of studies, reproduction size was <½ or >2x original, indicating population definition challenges. |

| Brain Signature Validation [7] | Correlation of consensus model fits in validation subsets. | Model fits were "highly correlated" across 50 random validation subsets. | High replicability of the validated model's performance was achieved. |

| Brain Signature Validation [7] | Model performance vs. theory-based models. | Signature models "outperformed other commonly used measures" in explanatory power. | Data-driven, validated models can provide more complete accounts of brain-behavior associations. |

The collective evidence from large-scale replication projects underscores a critical message: reproducibility is achievable but not automatic. It is a measurable outcome that depends critically on methodological rigor, transparent reporting, and the use of robust validation frameworks. The higher correlation and closer effect size alignment observed in the REPEAT Initiative, compared to earlier psychology projects, may reflect both the nature of the data and an evolving scientific culture increasingly attuned to these issues. The successful application of consensus model fits and independent validation cohorts in neuroscience illustrates a proactive methodological shift designed to build replicability directly into the discovery process.

For the research community, the path forward is clear. Prioritizing transparent reporting of all methodological parameters, from cohort entry definitions to analytic code, is non-negotiable for enabling independent reproducibility [4]. Embracing practices like pre-registration and data sharing, as seen in the projects listed on the Replication Hub [8], is essential. Furthermore, adopting sophisticated validation architectures, such as consensus modeling and hold-out validation cohorts, will help ensure that the measures and models we develop are not only statistically significant but also reproducible and useful across different populations and settings [7]. For drug development professionals, these lessons are directly applicable to the evaluation of RWE and biomarker validation, ensuring that the evidence base for regulatory and coverage decisions is as robust and reliable as possible.

In the pursuit of accurate predictive models, researchers and drug development professionals often find that a model that performs exceptionally well in initial studies fails catastrophically when applied to new data. This replication crisis stems primarily from two intertwined pitfalls: overfitting and sample-specific bias. Overfitting occurs when a model learns not only the underlying signal in the training data but also the noise and irrelevant details, rendering it incapable of generalizing to new datasets [9] [10]. Sample-specific bias arises when training data is not representative of the broader population, often due to limited sample size, demographic skew, or non-standardized data collection protocols [9] [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance of single, complex models against consensus and validated approaches, demonstrating through experimental data why rigorous validation frameworks are non-negotiable for replicable science.

Defining the Problem: Overfitting and Bias Explained

An overfit model is characterized by high accuracy on training data but poor performance on new, unseen data [9] [12]. This undesirable machine learning behavior is often driven by high model complexity relative to the amount of training data, noisy data, or training for too long on a single sample set [9].

The companion issue, sample-specific bias, introduces systematic errors. For instance, a model predicting academic performance trained primarily on one demographic may fail for other groups [9]. Similarly, an AI game agent might exploit a glitch in its specific training environment, a creative but fragile solution that fails in a corrected setting [10]. This underscores that a model can fail not just on random data, but on data from a slightly different distribution, which is common in real-world applications.

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

The classical understanding of this problem is framed by the bias-variance tradeoff [10] [12].

- High Bias (Underfitting): The model is too simple to capture the underlying patterns in the data, leading to inaccurate predictions on both training and test data [9] [12].

- High Variance (Overfitting): The model is too complex, capturing noise in the training data and resulting in accurate predictions for training data but poor performance on new data [9] [12].

The conventional solution is to find a "sweet spot" between bias and variance [9] [10]. However, modern machine learning, particularly deep learning, has revealed phenomena that challenge this classical view, such as complex models that generalize well despite interpolating training data, suggesting our understanding of overfitting is still evolving [10].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies of Model Failure and Success

The following case studies from recent biomedical research illustrate the severe consequences of overfitting and bias, and how rigorous validation protocols can mitigate them.

Case Study 1: Predicting Complications in Acute Leukemia

This study developed a model to predict severe complications in patients with acute leukemia, explicitly addressing overfitting risks through a robust validation framework [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To develop and externally validate a machine-learning model for predicting severe complications within 90 days of induction chemotherapy [11].

- Data Cohorts: Retrospective electronic health record data from three tertiary haematology centres (2013–2024). The derivation cohort had 2,009 patients, and the external validation cohort had 861 patients [11].

- Predictor Selection: 42 candidate predictors were selected based on literature review and clinical relevance. Data preprocessing included multiple imputation for missing values, Winsorization of outliers, and correlation filtering to remove highly correlated features (|ρ| > 0.80) [11].

- Model Training: Five algorithms (Elastic-Net, Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, and a multilayer perceptron) were trained using nested 5-fold cross-validation to tune hyperparameters and evaluate performance without overfitting the validation set [11].

- Validation Strategy: The model was tested on a temporally and geographically distinct external validation cohort, following TRIPOD-AI and PROBAST-AI guidelines [11].

Table 1: Performance of Machine Learning Models for Leukemia Complication Prediction

| Model | Derivation AUROC (Mean ± SD) | External Validation AUROC (95% CI) | Calibration Slope |

|---|---|---|---|

| LightGBM | 0.824 ± 0.008 | 0.801 (0.774–0.827) | 0.97 |

| XGBoost | Not Reported | 0.785 (0.757–0.813) | Not Reported |

| Random Forest | Not Reported | 0.776 (0.747–0.805) | Not Reported |

| Elastic-Net | Not Reported | 0.759 (0.729–0.789) | Not Reported |

| Multilayer Perceptron | Not Reported | 0.758 (0.728–0.788) | Not Reported |

The LightGBM model demonstrated the best performance, maintaining robust discrimination in external validation. Its excellent calibration (slope close to 1.0) indicates that its predicted probabilities closely match the observed outcomes, a critical feature for clinical decision-making [11]. The use of external validation, rather than just internal cross-validation, provided a true test of its generalizability.

Case Study 2: A Simplified Frailty Assessment Tool

This study developed a machine learning-based frailty tool, highlighting the importance of feature selection and multi-cohort validation to ensure simplicity and generalizability [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To develop a clinically feasible frailty assessment tool that balances predictive accuracy with implementation simplicity [13].

- Data Cohorts: Multi-cohort study using data from NHANES (n=3,480), CHARLS (n=16,792), CHNS (n=6,035), and SYSU3 CKD (n=2,264) [13].

- Feature Selection: A systematic process using five complementary algorithms (LASSO, VSURF, Boruta, varSelRF, and RFE) was applied to 75 potential variables. Intersection analysis identified a minimal set of 8 core features consistently selected by all algorithms [13].

- Model Training: 12 machine learning algorithms were evaluated. The best-performing model was selected based on performance across training, internal validation, and external validation datasets [13].

- Validation Strategy: The model was externally validated on three independent cohorts for predicting frailty diagnosis, chronic kidney disease progression, cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality [13].

Table 2: Performance of XGBoost Frailty Model Across Cohorts and Outcomes

| Validation Cohort | Outcome | AUROC (95% CI) | Comparison vs. Traditional Indices (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHANES (Training) | Frailty Diagnosis | 0.963 (0.951–0.975) | Not Applicable |

| NHANES (Internal) | Frailty Diagnosis | 0.940 (0.924–0.956) | Not Applicable |

| CHARLS (External) | Frailty Diagnosis | 0.850 (0.832–0.868) | Not Applicable |

| SYSU3 CKD | CKD Progression | 0.916 | < 0.001 |

| SYSU3 CKD | Cardiovascular Events | 0.789 | < 0.001 |

| SYSU3 CKD | All-Cause Mortality | 0.767 (Time-dependent) | < 0.001 |

The XGBoost model, built on only 8 readily available clinical parameters, significantly outperformed traditional frailty indices across multiple health outcomes [13]. This demonstrates that rigorous feature selection can create simple, generalizable models without sacrificing predictive power. The decline in AUROC from training to external validation underscores the necessity of testing models on independent data.

The Validation Toolkit: Methodologies to Ensure Replicability

Detecting and preventing overfitting requires a systematic approach to model validation. Below are key techniques and their workflows.

Core Validation Techniques

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: This method partitions the dataset into K equally sized subsets (folds). The model is trained on K-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold. This process is repeated K times, with each fold used exactly once as the validation set. The final performance is averaged across all iterations [9] [14] [12].

- Hold-Out Validation with a Test Set: The dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets. The model is trained on the training set, its hyperparameters are tuned on the validation set, and its final performance is evaluated exactly once on the held-out test set [15].

- External Validation: The ultimate test of a model's generalizability is its performance on data collected from a different source, location, or time period, ideally as part of a multi-cohort study [11] [13].

- Regularization: Techniques like L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization add a penalty term to the model's loss function, discouraging it from becoming overly complex and relying too heavily on any single feature [9] [10] [12].

- Ensembling: Methods like bagging (e.g., Random Forest) and boosting (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) combine predictions from multiple weaker models to create a more robust and accurate final model that is less prone to overfitting [9] [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these techniques are integrated into a robust model development pipeline.

Key Performance Metrics for Validation

A comprehensive model assessment requires evaluating multiple aspects of performance [16].

Table 3: Key Metrics for Model Validation

| Aspect | Metric | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Performance | Brier Score | Measures the average squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes. Closer to 0 is better [16]. |

| Discrimination | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC/AUROC) | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes. 0.5 = random, 1.0 = perfect discrimination [11] [16]. |

| Discrimination | Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) | Particularly informative for imbalanced datasets, as it focuses on the performance of the positive (usually minority) class [11]. |

| Calibration | Calibration Slope & Intercept | Assesses the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed frequencies. A slope of 1 and intercept of 0 indicate perfect calibration [11] [16]. |

| Clinical Utility | Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) | Quantifies the net benefit of using the model for clinical decision-making across a range of probability thresholds [11] [17] [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools and reagents are essential for building and validating predictive models that stand up to the demands of replicable research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item | Function | Example Tools & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Environment | Provides the foundational language and libraries for data manipulation, model development, and analysis. | R (version 4.4.2) [17], Python with scikit-learn [15]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | The core models used to learn patterns from data. Comparing multiple algorithms is crucial. | LightGBM [11], XGBoost [13], Random Forest [11], Elastic-Net regression [11] [17]. |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Identify the most predictive variables, reducing model complexity and overfitting potential. | LASSO regression [17], Boruta algorithm, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [13]. |

| Model Validation Platforms | Tools that streamline the process of model comparison, validation, and visualization. | DataRobot [18], Scikit-learn, TensorFlow [14]. |

| Explainability Frameworks | Techniques to interpret "black-box" models, building trust and providing biological insights. | SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) [11]. |

Key Insights and Best Practices for Robust Models

The evidence overwhelmingly shows that a single model developed and validated on a single dataset is highly likely to fail in practice. The path to replicable models requires a consensus on rigorous validation.

- Prioritize External Validation: Internal validation via cross-validation is necessary but insufficient. Models must be tested on externally held-out cohorts, preferably from different institutions or time periods, to prove their generalizability [11] [13].

- Embrace Simplicity with Rigor: A model with fewer, well-selected features is often more robust and clinically translatable than a complex model with hundreds of variables. Employ systematic feature selection to avoid overfitting [13].

- Report Comprehensive Metrics: Go beyond the AUROC. A model must also be well-calibrated (its predictions must match reality) and provide a net clinical benefit, as shown by decision curve analysis [11] [16].

- Utilize Ensemble Methods: For complex problems, ensemble methods like gradient boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM) often provide superior and more robust performance compared to single models by reducing variance [11] [13].

- Adopt a Validation-First Mindset: The validation strategy should be designed before model development begins, incorporating techniques like nested cross-validation to prevent over-optimism and data leakage [11] [14].

In conclusion, the failure of single models is not an inevitability but a consequence of inadequate validation. By adopting a consensus framework that demands external validation, transparent reporting, and a focus on clinical utility, researchers can build predictive tools that truly replicate and deliver on their promise in drug development and beyond.

In scientific research and forecasting, a multi-model ensemble (MME) is a technique that combines the outputs of multiple, independent models to produce a single, more robust prediction or projection. The fundamental thesis is that a consensus drawn from diverse models is more likely to capture the underlying truth and generalize effectively to new data, such as validation cohorts, than any single "best" model. This guide explores the theoretical and empirical basis for this consensus, comparing the performance of ensemble means against individual models across diverse fields including hydrology, climate science, and healthcare.

Theoretical Foundations of Ensemble Robustness

The enhanced robustness of MMEs is not merely an empirical observation but is grounded in well-established statistical and theoretical principles.

- The Wisdom of Crowds: The core idea is that the aggregation of information from a group of independent, diverse, and decentralized models often yields a more accurate and stable estimate than that of any single member. In the context of climate science, this means that different models, with their unique structural representations of physical processes, sample the uncertainties in our understanding of the climate system [19].

- Error Cancellation: Individual models often contain specific biases and errors. When models are independent, their errors are frequently uncorrelated. By averaging model outputs, these individual biases can partially cancel each other out, leading to an ensemble mean with a lower overall error than the average error of the constituent models [20].

- Structural Uncertainty Quantification: A key source of uncertainty in predictions is "structural uncertainty," which arises from the different ways processes can be represented in a model. A multi-model ensemble directly samples this structural uncertainty. Relying on a single model ignores this uncertainty, while an MME provides a distribution of plausible outcomes, offering a more honest representation of forecast confidence [19].

Empirical Evidence: Cross-Domain Performance Comparison

Quantitative evidence from multiple scientific disciplines consistently demonstrates the superior performance and robustness of multi-model ensembles when validated on independent data.

Table 1: Performance of Multi-Model Ensembles Across Disciplines

| Field of Study | Ensemble Method | Performance Metric | Ensemble Result | Individual Model Results | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrology [20] | Arithmetic Mean (44 models) | Accuracy & Robustness | More accurate and robust; smaller performance degradation in validation | Performance degraded more significantly, especially with climate change | MME showed greater robustness to changing climate conditions between calibration and validation periods. |

| Climate Simulation [21] | Bayesian Model Averaging (5 models) | Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) | Precipitation: 0.82Tmax: 0.65Tmin: 0.82 | Arithmetic Mean KGE:Precipitation: 0.59Tmax: 0.28Tmin: 0.45 | Performance-weighted ensemble (BMA) significantly outperformed simple averaging. |

| Colorectal Cancer Detection [22] | Stacked Ensemble (cfDNA fragmentomics) | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Validation AUC: 0.926 | N/A | The ensemble achieved high sensitivity across all cancer stages (Stage I: 94.4%, Stage IV: 100%). |

| ICU Readmission Prediction [23] | Custom Ensemble (iREAD) | AUROC (Internal Validation) | 48-hr Readmission: 0.771 | Outperformed all traditional scoring systems and conventional machine learning models (p<0.001) | Demonstrated superior generalizability in external validation cohorts. |

Experimental Protocols for Ensemble Construction

The process of building and validating a robust multi-model ensemble follows a systematic workflow. The diagram below outlines the key stages, from model selection to final validation.

The following protocols detail the critical methodologies cited in the research:

- Protocol 1: Large-Sample Hydrological Ensemble Testing - This evaluation of 44 conceptual hydrological models across 582 river basins highlights the importance of scale. The models were calibrated on a period (1980-1990) and validated on a much later period (2013-2014) with a long gap in between. This "differential split-sample" test was designed to stress-test model robustness under a changing climate. The key performance metric was the degradation in prediction accuracy between the calibration and validation periods, with the MME showing significantly less degradation than any single model [20].

- Protocol 2: Multi-Criteria Climate Model Ranking and Weighting - This study used a Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) technique, TOPSIS, to rank 19 CMIP6 climate models. The models were evaluated against ERA5 reanalysis data using seven different error metrics (e.g., Kling-Gupta Efficiency, normalized root mean squared error) for different seasons and variables. This comprehensive ranking ensured that the final ensemble of top models was not biased by a single performance metric. The ensemble mean was then calculated using both a simple Arithmetic Mean (AM) and a performance-weighted Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA), with BMA demonstrating superior skill [21].

- Protocol 3: Stacked Ensemble for Medical Diagnosis - In this clinical study, a stacked ensemble model was built by integrating three distinct fragmentomics features from cell-free DNA using a machine learning meta-learner. The model was trained on a multi-center cohort and then validated on a completely independent cohort of patients. This rigorous validation on unseen data from different hospitals was critical to demonstrating that the model's high accuracy (AUC of 0.926) was generalizable and not a product of overfitting to the training data [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ensemble Research

Table 2: Key Analytical Tools and Resources for Ensemble Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Function in Ensemble Research | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| MARRMoT Toolbox [20] | Provides 46 modular conceptual hydrological models for consistently testing and comparing a wide range of model structures. | Hydrology, Rainfall-Runoff Modeling |

| CAMELS Dataset [20] | A large-sample dataset providing standardized meteorological forcing and runoff data for hundreds of basins, enabling robust large-sample studies. | Hydrology, Environmental Science |

| CMIP6 Data Portal [21] | The primary repository for a vast suite of global climate model outputs, forming the basis for most modern climate multi-model ensembles. | Climate Science, Meteorology |

| ERA5 Reanalysis Data [21] | A high-quality, globally complete climate dataset that serves as a common benchmark ("observed data") for evaluating and weighting climate models. | Climate Science, Geophysics |

| TOPSIS Method [21] | A multi-criteria decision-making technique used to rank models based on their performance across multiple, often conflicting, error metrics. | General Model Evaluation |

| Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) [21] | A sophisticated ensemble method that assigns weights to individual models based on their probabilistic likelihood and historical performance. | Climate, Statistics, Machine Learning |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [24] | An interpretable machine learning method used to explain the output of an ensemble model by quantifying the contribution of each input feature. | Machine Learning, Healthcare AI |

Advanced Ensemble Methodologies

Beyond simple averaging, advanced techniques are being developed to further enhance the robustness and adaptability of ensembles, particularly for complex, non-stationary systems.

- Dynamic Weighting with Reinforcement Learning: Unlike ensembles with static weights, this approach uses reinforcement learning (e.g., the soft actor-critic framework) to dynamically adjust the contribution of each base model in response to changing environmental conditions. This has shown significant promise in ocean wave forecasting, where the optimal model mix can change with sea state, leading to more accurate and stable predictions than any single model or static ensemble [25].

- Addressing Model Dependence: A critical theoretical challenge is that models within an ensemble are often not fully independent, as they share literature, ideas, and code. The presence of these "model families" can bias the ensemble if not accounted for. Research emphasizes that quantifying this dependence and using weighting or sub-selection strategies that consider both model performance and independence is key to a sound interpretation of ensemble projections [19].

The consensus derived from multi-model ensembles provides a more robust and reliable foundation for scientific prediction and decision-making than single-model approaches. The theoretical basis—rooted in error cancellation and structural uncertainty quantification—is strongly supported by empirical evidence across hydrology, climate science, and clinical research. The critical factor for success is a rigorous validation protocol that tests the ensemble on independent data, ensuring that the observed robustness translates to real-world generalizability. As ensemble methods evolve with techniques like dynamic weighting and sophisticated dependence-aware averaging, their role in enhancing the replicability and reliability of scientific models will only grow.

In the evolving landscape of scientific research, particularly within drug development and biomedical sciences, the validation of findings through replication has become a cornerstone of credibility and progress. Replication serves as the critical process through which the scientific community verifies the reliability and validity of reported findings, ensuring that research built upon these foundations is sound. A nuanced understanding of replication reveals three distinct methodologies: direct, conceptual, and computational replication. Each approach serves unique functions in the scientific ecosystem, from verifying basic reliability to exploring the boundary conditions of findings and leveraging in silico technologies for validation.

The ongoing "replication crisis" in various scientific fields has heightened awareness of the importance of robust replication practices. Within this context, direct replication focuses on assessing reliability through repetition, conceptual replication explores the generality of findings across varied operationalizations, and computational replication emerges as a transformative approach leveraging virtual models and simulations. This guide provides an objective comparison of these replication methodologies, their experimental protocols, and their application within modern research paradigms, particularly focusing on the validation of consensus models and cohorts in biomedical research.

Defining the Replication Landscape

Direct Replication

Direct replication (sometimes termed "exact" or "close" replication) involves repeating a study using the same methods, procedures, and measurements as the original investigation [26]. The primary function is to assess the reliability of the original findings by determining whether they can be consistently reproduced under identical conditions [27]. While a purely "exact" replication may be theoretically impossible due to inevitable contextual differences, researchers strive to maintain the same operationalizations of variables and experimental procedures [26].

A key insight from recent literature is that direct replication serves functions beyond mere reliability checking. It can uncover important contextualities inherent in research findings, leading to a richer understanding of what results truly imply [27]. For instance, identical numerical results in direct replications may sometimes mask differential effects of biases across different data sources, highlighting the risk of asymmetric evaluation in scientific assessment [27].

Conceptual Replication

Conceptual replication tests the same fundamental hypothesis or theory as the original study but employs different methodological approaches to operationalize the key variables [26]. This form of replication aims to determine whether a finding holds across varied measurements, populations, or contexts, thereby assessing its generality and robustness.

Where direct replication seeks to answer "Can this finding be reproduced under the same conditions?", conceptual replication asks "Does this phenomenon manifest across different operationalizations and contexts?" This approach is particularly valuable for addressing concerns about systematic error that might affect both the original and direct replication attempts [26]. By deliberately sampling for heterogeneity in methods, conceptual replication can reveal whether a finding represents a general principle or is limited to specific methodological conditions.

Computational Replication

Computational replication represents a paradigm shift in verification methodologies, leveraging computer simulations, virtual models, and artificial intelligence to validate research findings. In biomedical contexts, this approach includes in silico trials that use "individualized computer simulation used in the development or regulatory evaluation of a medicinal product, device, or intervention" [28]. This methodology is rapidly evolving from a supplemental technique to a central pillar of biomedical research, alongside traditional in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo approaches [29].

The rise of computational replication is facilitated by advances in AI, high-performance computing, and regulatory science. The FDA's 2025 announcement phasing out mandatory animal testing for many drug types signals a paradigm shift toward in silico methodologies [29]. Computational replication enables researchers to simulate thousands of virtual patients, test interventions across diverse demographic profiles, and model biological systems with astonishing granularity, all while reducing ethical concerns and resource requirements associated with traditional methods.

Comparative Analysis of Replication Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Replication Types Across Key Dimensions

| Dimension | Direct Replication | Conceptual Replication | Computational Replication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Assess reliability through identical repetition | Test generality across varied operationalizations | Validate through simulation and modeling |

| Methodological Approach | Same procedures, measurements, and analyses | Different methods testing same theoretical construct | Computer simulations, digital twins, AI models |

| Key Strength | Identifies false positives and methodological artifacts | Establishes robustness and theoretical validity | Enables rapid, scalable, cost-effective validation |

| Limitations | Susceptible to same systematic errors as original | Difficult to interpret failures; may test different constructs | Model validity dependent on input data and assumptions |

| Resource Requirements | Moderate to high (new data collection often needed) | High (requires developing new methodologies) | High initial investment, lower marginal costs |

| Typical Timeframe | Medium-term | Long-term | Rapid once models are established |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established | Well-established | Growing rapidly (FDA, EMA) |

| Role in Consensus Model Validation | Tests reliability of original findings | Explores boundary conditions and generalizability | Enables validation across virtual cohorts |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Replication Impact and Outcomes

| Performance Metric | Direct Replication | Conceptual Replication | Computational Replication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Overturn Rate | 3.5-11% of studies [30] | Not systematically quantified | Varies by model accuracy |

| Citation Impact After Failure | ~35% reduction after few years [30] | Dependent on clarity of conceptual linkage | Not yet established |

| Typical Cost Range | Similar to original study | Often exceeds original study | $3.76B global market (2023) [31] |

| Time Efficiency | Similar to original study | Often exceeds original study | VICTRE study: 1.75 vs. 4 years [28] |

| Downstream Attention Averted | Up to 35% of citations [30] | Potentially broader impact | Prevents futile research directions earlier |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Direct Replication

A rigorous direct replication requires meticulous attention to methodological fidelity while acknowledging inevitable contextual differences:

Protocol Verification: Obtain and thoroughly review the original study materials, including methods, measures, procedures, and analysis plans. When available, examine original data and code to identify potential ambiguities in the reported methodology.

Contextual Transparency: Document all aspects of the replication context that may differ from the original study, including laboratory environment, researcher backgrounds, participant populations, and temporal factors. As Satyanarayan et al. note, design elements of visualizations (and by extension, all methodological elements) can influence viewer assumptions about source and trustworthiness [32].

Implementation Fidelity: Execute the study following the original procedures as closely as possible while maintaining ethical standards. This includes using the same inclusion/exclusion criteria, experimental materials, equipment specifications, and data collection procedures.

Analytical Consistency: Apply the original analytical approach, including statistical methods, data transformation procedures, and outcome metrics. Preregister any additional analyses to distinguish confirmatory from exploratory work.

Reporting Standards: Clearly report all deviations from the original protocol and discuss their potential impact on findings. The replication report should enable readers to understand both the methodological similarities and differences relative to the original study.

Protocol for Conceptual Replication

Conceptual replication requires careful translation of theoretical constructs into alternative operationalizations:

Construct Mapping: Clearly identify the theoretical constructs examined in the original study and develop alternative methods for operationalizing these constructs. This requires deep theoretical understanding to ensure the new operationalizations adequately capture the same underlying phenomenon.

Methodological Diversity: Design studies that vary key methodological features while maintaining conceptual equivalence. This might include using different measurement instruments, participant populations, experimental contexts, or data collection modalities.

Falsifiability Considerations: Define clear criteria for what would constitute successful versus unsuccessful replication. Unlike direct replication where success is typically defined as obtaining statistically similar effects, conceptual replication success may involve demonstrating similar patterns across methodologically diverse contexts.

Convergent Validation: Incorporate multiple methodological variations within a single research program or across collaborating labs to establish a pattern of convergent findings. As Feest argues, systematic error remains a concern in replication, necessitating thoughtful design [26].

Interpretive Framework: Develop a framework for interpreting both consistent and inconsistent findings across methodological variations. Inconsistencies may reveal theoretically important boundary conditions rather than simple replication failures.

Protocol for Computational Replication

Computational replication, particularly using in silico trials, follows a distinct protocol focused on model development and validation:

Figure 1: Computational Replication Workflow for In Silico Trials

Data Integration and Model Development: Collect and integrate diverse real-world data sources to inform model parameters. This includes clinical trial data, electronic health records, biomedical literature, and omics data. Develop mechanistic or AI-driven models that accurately represent the biological system or intervention being studied.

Virtual Cohort Generation: Create in silico cohorts that reflect the demographic, physiological, and pathological diversity of target populations. The EU-Horizon funded SIMCor project, for example, has developed statistical web applications specifically for validating virtual cohorts against real datasets [28].

Simulation Execution: Run multiple iterations of the virtual experiment across the simulated cohort to assess outcomes under varied conditions. This may include testing different dosing regimens, patient characteristics, or treatment protocols.

Validation Against Empirical Data: Compare simulation outputs with real-world evidence from traditional studies. Use statistical techniques to quantify the concordance between virtual and actual outcomes. The SIMCor tool provides implemented statistical techniques for comparing virtual cohorts with real datasets [28].

Regulatory Documentation: Prepare comprehensive documentation of model assumptions, parameters, validation procedures, and results for regulatory submission. Agencies like the FDA and EMA increasingly accept in silico evidence, particularly through Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) programs [29] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Replication Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Replication | Applicable Replication Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Platforms | R-statistical environment with Shiny [28] | Validates virtual cohorts and analyzes in-silico trials | Computational |

| Simulation Software | BIOVIA, SIMULIA [31] | Virtual device testing and biological modeling | Computational |

| Digital Twin Platforms | Unlearn.ai, InSilicoTrials Technologies [29] [31] | Creates virtual patient replicas for simulation | Computational |

| Toxicity Prediction | DeepTox, ProTox-3.0, ADMETlab [29] | Predicts drug toxicity and off-target effects | Computational, Direct |

| Protein Structure Prediction | AlphaFold [29] | Predicts protein folding for target validation | Conceptual, Computational |

| Validation Frameworks | Good Simulation Practice (GSP) | Standardizes model evaluation procedures | Computational |

| Data Visualization Tools | ColorBrewer, Tableau | Ensures accessible, interpretable results reporting | All types |

| Protocol Registration | OSF, ClinicalTrials.gov | Ensures transparency and reduces publication bias | All types |

Analysis of Quantitative Data and Outcomes

Success Rates and Impact Metrics

Recent meta-scientific research provides quantitative insights into replication outcomes across fields. Analysis of 110 replication reports from the Institute for Replication found that computational reproduction and robustness checks fully overturned a paper's conclusions approximately 3.5% of the time and substantially weakened them another 16.5% of the time [30]. When considering both fully overturned cases and half of the weakened cases, the estimated rate of genuine unreliability across the literature reaches approximately 11% [30].

The impact of failed replications on subsequent citation patterns reveals important information about scientific self-correction. Evidence suggests that failed replications lead to a ~10% reduction in citations in the first year after publication, stabilizing at a ~35% reduction after a few years [30]. This citation impact is crucial for calculating the return on investment of replication studies, as averted citations to flawed research represent saved resources that might otherwise have been wasted on fruitless research directions.

Economic Considerations in Replication

The economic case for replication funding hinges on comparing the costs of replication against the potential savings from averting research based on flawed findings. When targeted at recent, influential studies, replication can provide large returns, sometimes paying for itself many times over [30]. Analysis suggests that a well-calibrated replication program could productively spend about 1.4% of the NIH's annual budget before hitting negative returns relative to funding new science [30].

The economic advantage of computational replication is particularly striking. The VICTRE study demonstrated that in silico trials required only one-third of the resources and approximately 1.75 years compared to 4 years for a conventional trial [28]. The global in-silico clinical trials market, valued at USD 3.76 billion in 2023 and projected to reach USD 6.39 billion by 2033, reflects growing recognition of these efficiency gains [31].

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Selecting Replication Approaches

The contemporary research landscape demands a strategic approach to replication that leverages the complementary strengths of direct, conceptual, and computational methodologies. Direct replication remains essential for verifying the reliability of influential findings, particularly those informing policy or clinical practice. Conceptual replication provides critical insights into the generality and boundary conditions of phenomena. Computational replication offers transformative potential for accelerating validation while reducing costs and ethical concerns.

The most robust research programs strategically integrate these approaches, recognizing that they address different but complementary questions about scientific claims. Direct replication asks "Can we trust this specific finding?" Conceptual replication asks "How general is this phenomenon?" Computational replication asks "Can we model and predict this system?" Together, they form a comprehensive framework for establishing scientific credibility.

As computational methods continue to advance and gain regulatory acceptance, their role in the replication ecosystem will likely expand. However, rather than replacing traditional approaches, in silico methodologies will increasingly complement them, creating hybrid models of scientific validation that leverage the strengths of each paradigm. The researchers and drug development professionals who master this integrated approach will be best positioned to produce reliable, impactful science in the decades ahead.

Building Robust Consensus Models: From Data Curation to Implementation

High-dimensional data presents a significant challenge in biomedical research, particularly in genomics, transcriptomics, and clinical biomarker discovery. The selection of relevant features from thousands of potential variables is critical for building robust, interpretable, and clinically applicable predictive models. Within the context of replicability consensus model fits validation cohorts research, the choice of feature selection methodology directly impacts a model's ability to generalize beyond the initial discovery dataset and maintain predictive performance in independent validation cohorts.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three prominent feature selection approaches—LASSO regression, Random Forest-based selection, and the Boruta algorithm—examining their theoretical foundations, practical performance, and suitability for different research scenarios. Each method represents a distinct philosophical approach to the feature selection problem: LASSO employs embedded regularization within a linear framework, Random Forests use ensemble-based importance metrics, and Boruta implements a wrapper approach with statistical testing against random shadows. Understanding their comparative strengths and limitations is essential for constructing models that not only perform well initially but also maintain their predictive power across diverse populations and experimental conditions, thereby advancing replicable scientific discovery.

Methodological Foundations: Three Approaches to Feature Selection

LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator)

LASSO regression operates as an embedded feature selection method that performs both variable selection and regularization through L1-penalization. By adding a penalty equal to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients, LASSO shrinks less important feature coefficients to zero, effectively removing them from the model [33] [34]. This results in a sparse, interpretable model that is particularly valuable when researchers hypothesize that only a subset of features has genuine predictive power. The method assumes linear relationships between features and outcomes and requires careful hyperparameter tuning (λ) to control the strength of regularization.

Random Forest Feature Importance

Random Forest algorithms provide feature importance measures through an embedded approach that calculates the mean decrease in impurity (Gini importance) across all trees in the ensemble [35]. Each time a split in a tree is based on a particular feature, the impurity decrease is recorded and averaged over all trees in the forest. Features that consistently provide larger decreases in impurity are deemed more important. This method naturally captures non-linear relationships and interactions without explicit specification, making it valuable for complex biological systems where linear assumptions may not hold.

Boruta Algorithm

The Boruta algorithm is a robust wrapper method built around Random Forest classification that identifies all relevant features—not just the most prominent ones [33] [36]. It works by creating shuffled copies of all original features (shadow features), training a Random Forest classifier on the extended dataset, and then comparing the importance of original features to the maximum importance of shadow features. Features with importance significantly greater than their shadow counterparts are deemed important, while those significantly less are rejected. This iterative process continues until all features are confirmed or rejected, or a predetermined limit is reached [36].

Performance Comparison Across Biomedical Applications

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methods Across Different Biomedical Domains

| Application Domain | LASSO Performance | Random Forest Performance | Boruta Performance | Best Performing Model | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke Risk Prediction in Hypertension [33] | AUC: 0.716 | AUC: 0.626 | AUC: 0.716 | LASSO and Boruta (tie) | Area Under Curve (AUC) of ROC |

| Asthma Risk Prediction [34] | AUC: 0.66 | N/R | AUC: 0.64 | LASSO | Area Under Curve (AUC) of ROC |

| COVID-19 Mortality Prediction [35] | N/R | Accuracy: 0.89 with Hybrid Boruta | Accuracy: 0.89 (Hybrid Boruta-VI + RF) | Hybrid Boruta-VI + Random Forest | Accuracy, F1-score: 0.76, AUC: 0.95 |

| Diabetes Prediction [37] | N/R | N/R | Accuracy: 85.16% with LightGBM | Boruta + LightGBM | Accuracy, F1-score: 85.41%, 54.96% reduction in training time |

| DNA Methylation-based Telomere Length Estimation [38] | Moderate performance with prior feature selection | Variable performance | N/R | PCA + Elastic Net | Correlation: 0.295 on test set |

Table 2: Characteristics and Trade-offs of Feature Selection Methods

| Characteristic | LASSO | Random Forest Feature Importance | Boruta |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Type | Embedded | Embedded | Wrapper |

| Primary Strength | Produces sparse, interpretable models; handles correlated features | Captures non-linear relationships and interactions | Identifies all relevant features; robust against random fluctuations |

| Key Limitation | Assumes linear relationships; sensitive to hyperparameter tuning | May miss features weakly relevant individually; bias toward high-cardinality features | Computationally intensive; may select weakly relevant features |

| Interpretability | High (clear coefficient magnitudes) | Moderate (importance scores) | Moderate (binary important/not important) |

| Computational Load | Low to Moderate | Moderate | High (iterative process with multiple RF runs) |

| Stability | Moderate | Moderate to High | High (statistical testing against shadows) |

| Handling of Non-linearity | Poor (without explicit feature engineering) | Excellent | Excellent |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Low to Moderate | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Boruta Implementation Protocol

The Boruta algorithm follows a meticulously defined iterative process to distinguish relevant features from noise [36]:

- Shadow Feature Creation: Duplicate all features in the dataset, shuffle their values to break correlations with the outcome, and prefix them with "shadow" for identification.

- Random Forest Training: Train a Random Forest classifier on the extended dataset containing both original and shadow features.

- Importance Comparison: Calculate the Z-score of importance for each original and shadow feature. Establish a threshold using the maximum importance score among shadow features.

- Statistical Testing: Perform a two-sided test of equality for each unassigned feature comparing its importance to the shadow maximum.

- Feature Classification:

- Features with importance significantly higher than the threshold are tagged as 'important'

- Features with importance significantly lower are deemed 'unimportant' and removed from consideration

- Iteration: Remove all shadow features and repeat the process until importance is assigned to all features or a predetermined iteration limit is reached.

LASSO Regression Protocol for Feature Selection

LASSO implementation follows a standardized workflow [33] [34]:

- Data Preprocessing: Standardize or normalize all features to ensure penalty terms are equally applied. For positive indicators, divide each value by the maximum value (X′ = X/max). For negative indicators, divide the minimum value by each observation (X′ = min/X).

- Parameter Tuning: Use k-fold cross-validation (typically 5- or 10-fold) to determine the optimal regularization parameter (λ) that minimizes cross-validation error.

- Model Fitting: Apply LASSO regression with the optimal λ to the entire training set, which will naturally shrink coefficients of less relevant features to zero.

- Feature Selection: Retain only features with non-zero coefficients in the final model.

- Validation: Assess model performance on held-out test data using AUC, accuracy, or other domain-appropriate metrics.

Hybrid Boruta-LASSO Workflow

Recent studies have explored combining Boruta and LASSO in sequential workflows [33]:

- Initial Feature Screening: Apply Boruta algorithm to identify a subset of potentially relevant features, removing clearly irrelevant variables.

- Secondary Regularization: Apply LASSO regression to the Boruta-selected feature subset for further refinement and coefficient shrinkage.

- Performance Validation: Evaluate the hybrid approach against individual methods using nested cross-validation or independent test sets.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Feature Selection Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary environment for statistical computing and model implementation | glmnet package for LASSO [33] [34], Boruta package for Boruta algorithm [33] [36] |

| Python Scikit-learn | Machine learning library for model development and evaluation | LassoCV for LASSO, RandomForestClassifier for ensemble methods [35] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretation framework for consistent feature importance values | TreeExplainer for Random Forest and Boruta interpretations [36] [37] |

| MLR3 Framework | Comprehensive machine learning framework for standardized evaluations | mlr3filters for filter-based feature selection methods [35] |

| Custom BorutaShap Implementation | Python implementation combining Boruta with SHAP importance | Enhanced feature selection with more consistent importance metrics [36] |

| Cross-Validation Frameworks | Robust performance estimation and hyperparameter tuning | k-fold (typically 5- or 10-fold) cross-validation for parameter optimization [33] [37] |

Discussion: Implications for Replicability and Validation Research

The comparative analysis of LASSO, Random Forest, and Boruta feature selection methods reveals critical considerations for researchers focused on replicability consensus model fits validation cohorts. Each method offers distinct advantages that may be appropriate for different research contexts within biomedical applications.

LASSO regression demonstrates strong performance in multiple clinical prediction tasks (AUC 0.716 for stroke risk, 0.66 for asthma) while providing sparse, interpretable models [33] [34]. Its linear framework produces coefficients that are directly interpretable as feature effects, facilitating biological interpretation and clinical translation. However, this linear assumption may limit its performance in capturing complex non-linear relationships prevalent in biological systems.

Random Forest-based feature importance, particularly when implemented through the Boruta algorithm, excels at identifying features involved in complex interactions without requiring a priori specification of these relationships. The superior performance of Boruta with LightGBM for diabetes prediction (85.16% accuracy) and Hybrid Boruta-VI with Random Forest for COVID-19 mortality prediction (AUC 0.95) demonstrates its capability in challenging prediction tasks [35] [37].

For replicability research, the stability of feature selection across study populations is paramount. Boruta's statistical testing against random shadows provides theoretical advantages for stability, though at increased computational cost. The hybrid Boruta-LASSO approach represents a promising direction, potentially leveraging Boruta's comprehensive screening followed by LASSO's regularization to produce sparse, stable feature sets [33].

Researchers should select feature selection methods aligned with their specific replicability goals: LASSO for interpretable linear models, Random Forest for capturing complexity, and Boruta for comprehensive feature identification. In all cases, validation across independent cohorts remains essential for establishing true replicability, as performance on training data may not generalize to diverse populations.

Multi-cohort studies have become a cornerstone of modern epidemiological and clinical research, enabling investigators to overcome the limitations of individual studies by increasing statistical power, enhancing generalizability, and addressing research questions that cannot be answered by single populations [39]. The integration of data from diverse geographic locations and populations allows researchers to explore rare exposures, understand gene-environment interactions, and investigate health disparities across different demographic groups [39]. However, the process of sourcing and harmonizing data from multiple cohorts presents significant methodological challenges that must be carefully addressed to ensure valid and reliable research findings.