Brain Fingerprinting: Unlocking Individual Identity Through Functional Connectivity

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of functional connectivity (FC) as a unique and reliable biomarker for individual identification, known as brain fingerprinting.

Brain Fingerprinting: Unlocking Individual Identity Through Functional Connectivity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of functional connectivity (FC) as a unique and reliable biomarker for individual identification, known as brain fingerprinting. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts, methodological advances, optimization challenges, and validation paradigms. We cover the neurobiological basis of FC fingerprints, the application of machine learning and tensor decomposition for enhanced identifiability, strategies to overcome computational and reliability hurdles, and the critical distinction between identification accuracy and behavioral prediction. The review highlights the potential of this technology to advance personalized medicine and the development of objective neurodiagnostic tools.

The Blueprint of the Self: Foundations of the Functional Connectome Fingerprint

The study of brain organization has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift. For decades, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies traditionally collapsed data from many subjects to draw inferences about general patterns of brain activity common across people, overlooking the considerable heterogeneity within groups [1]. This approach, while valuable for identifying universal brain network blueprints, ignored a critical aspect of brain functional organization: its substantial individual variability. The emergence of the functional connectome fingerprint represents a transformative advancement, enabling a transition from population-level studies to investigations of single subjects [1]. This revolutionary concept establishes that an individual's pattern of functional connectivity—the statistical associations between time series of different brain regions—acts as a unique "fingerprint" that can accurately identify subjects from a large group [1]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of methodological approaches for defining and extracting these individual-specific connectivity signatures, detailing experimental protocols, benchmarking performance across methods, and outlining essential research tools for advancing this promising field toward personalized medicine and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Functional Connectome Fingerprinting Methodologies

Core Methodological Approaches and Identification Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Functional Connectome Fingerprinting Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Identification Accuracy | Key Brain Networks | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Correlation (Finn et al.) [1] | Pearson correlation between regional time courses | 92.9-99% (rest-rest); 54-87% (cross-task) [1] | Frontoparietal, Medial Frontal [1] | Two scanning sessions (different days) |

| PCA Reconstruction & Identifiability Maximization [2] | Reconstruction via group-wise connectivity eigenmodes | Maximizes subject identifiability across rest and tasks [2] | Optimized global and edgewise connectivity [2] | Multiple task and rest sessions |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) with Explicit Sparsity Control [3] | Hierarchical feature learning from time-varying FC | 97.1% (300 subjects, 15s window); 93.3% (870 subjects) [3] | Whole-brain with individualized important edges [3] | Single resting-state session with multiple time windows |

| Multi-Modal Pairwise Statistics Benchmarking [4] | Comparison of 239 interaction statistics | Varies by method; precision and covariance perform well [4] | Varies by method; dorsal attention, default mode highlighted [4] | Resting-state fMRI for benchmarking |

Neuroimaging Modalities for Fingerprint Extraction

Table 2: Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities for Functional Connectome Fingerprinting

| Modality | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Practical Advantages | Identification Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI [1] | Moderate (0.5-2s) | High (mm) | Comprehensive brain coverage; established pipelines | 92.9-99% accuracy (HCP data) [1] |

| fNIRS [5] | High (0.1s) | Limited to cortex | Portable; insensitive to motion; lower cost | Effective cross-task identification [5] |

| MEG [5] | High (ms) | Moderate | Direct neural activity measurement; excellent temporal resolution | Similar recognition rates to fMRI [5] |

| EEG [5] | High (ms) | Low | Cost-effective; excellent temporal resolution | Possible with graph neural network features [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Fingerprint Extraction and Validation

Core Fingerprinting Protocol Using Pairwise Correlations

The foundational protocol for establishing functional connectome fingerprints involves several methodical stages [1]. First, data acquisition typically uses resting-state or task-based fMRI from the Human Connectome Project or similar datasets, with multiple scanning sessions per subject. Preprocessing follows established pipelines including artifact removal, motion correction, registration to standard space, global signal regression, and bandpass filtering (typically 0.001-0.08 Hz) [1] [2].

For functional connectivity matrix construction, a brain atlas with 268 nodes (or alternative parcellations) defines regions of interest. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the timecourses of each possible pair of nodes is calculated to construct symmetrical connectivity matrices where each element represents connection strength between two nodes [1]. This produces a subject-specific connectivity profile for each scanning session.

The identification process itself involves iterative matching between "target" and "database" sessions from different days. For each individual's target connectivity matrix, similarity is computed against all matrices in the database using Pearson correlation between vectors of edge values. The database matrix with maximum similarity is selected, and the identity prediction is scored correct if it matches the true identity [1]. This process systematically demonstrates that an individual's connectivity profile is intrinsic and reliable enough to distinguish that individual regardless of how the brain is engaged during imaging.

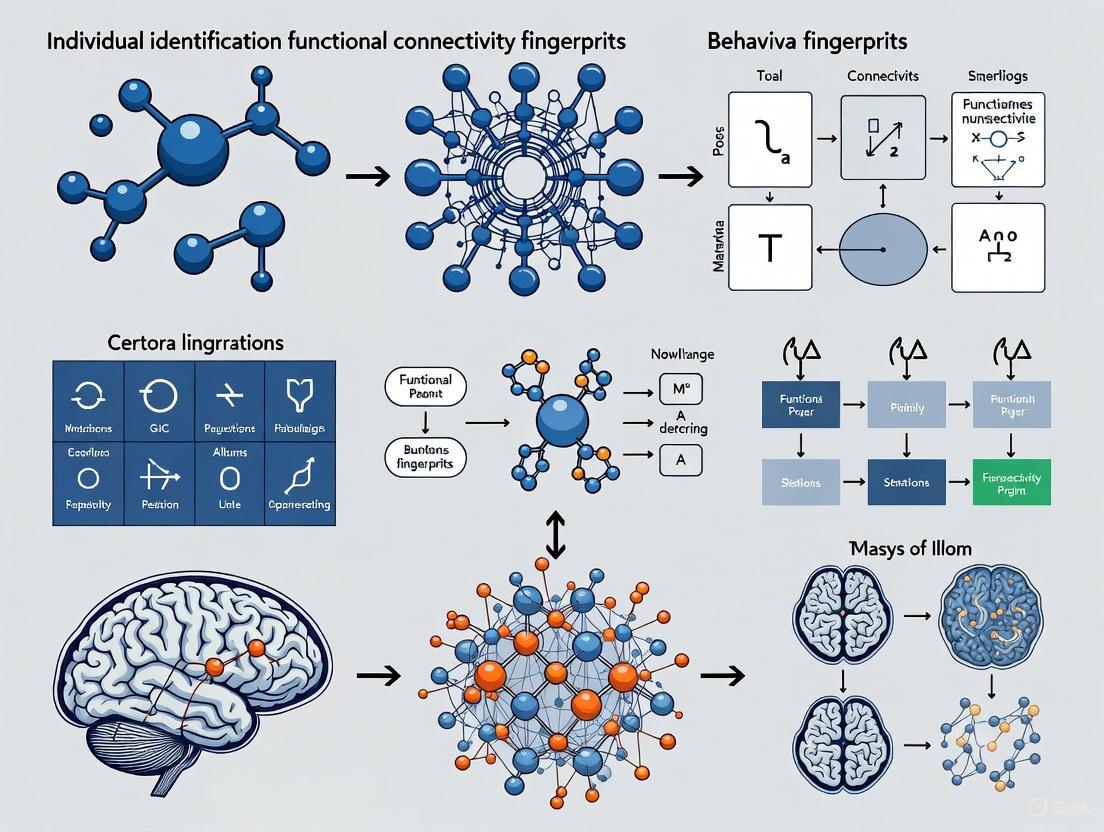

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for functional connectome fingerprint identification

Advanced Protocol: Deep Neural Network Fingerprint Extraction

For DNN-based fingerprint extraction, the protocol differs substantially [3]. After standard preprocessing, time-varying functional connectivity (tvFC) is estimated using sliding window approaches with varying window lengths (from 15 seconds to several minutes). A deep neural network with explicit weight sparsity control is then trained for individual identification, combining L1 regularization (for feature selection) and L2 regularization (for stability). The trained DNN generates what researchers term the "fingerprint of FC" (fpFC)—representative edges of individual FC that serve as robust neuromarkers. This approach successfully identifies hundreds of individuals even with very short time windows (15 seconds), demonstrating remarkable temporal efficiency [3].

Protocol for Maximizing Identifiability Through Connectivity Eigenmodes

This innovative approach employs group-wise decomposition in a finite number of brain connectivity modes to maximize individual fingerprint [2]. The method applies principal component analysis (PCA) decomposition across the cohort's functional connectomes, identifying common connectivity patterns. Individual connectomes are then reconstructed through an optimal finite linear combination of orthogonal principal components (connectivity eigenmodes). The optimal reconstruction level maximizes subject identifiability across both resting-state and task conditions. This reconstruction enhances edgewise identifiability as measured by intra-class correlation and produces more robust associations with task-related behavioral measurements [2].

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Functional Connectome Fingerprinting

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Application in Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Datasets | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [1] [2] | Method development and validation | High-quality fMRI; multiple tasks; large sample |

| Tel Aviv University SNBB [6] | Real-world cognitive prediction | Coupled with psychometric test scores | |

| Brain Atlases | 268-node functional atlas [1] | Standardized parcellation | Whole-brain coverage; defined on healthy subjects |

| Glasser 360-region cortical parcellation [2] | Fine-grained analysis | Detailed cortical mapping plus subcortical regions | |

| Software & Pipelines | FSL FIX ICA [2] | Artifact removal | Automated noise component identification |

| HCP Workbench [2] | Data processing | CIFTI data handling; surface-based analysis | |

| PySPI package [4] | Multi-method connectivity | 239 pairwise interaction statistics | |

| Analysis Methods | Pearson's correlation [1] | Baseline connectivity | Simple linear association; widely used |

| Precision/inverse covariance [4] | Direct connectivity estimation | Controls for shared network influences | |

| Sparse DNN architectures [3] | Individual fingerprint extraction | Handles high-dimensional noisy data |

Beyond Identification: Predicting Behavior and Cognitive Traits

The true value of functional connectome fingerprints extends far beyond mere identification to predicting clinically and educationally relevant outcomes. Research demonstrates that the same functional connectivity profiles that successfully identify individuals can also predict fundamental cognitive traits [1]. Specifically, connectivity patterns predict levels of fluid intelligence, with the most discriminating networks (frontoparietal) also being most predictive of cognitive behavior [1].

Remarkably, recent studies have successfully predicted real-world cognitive performance using resting-state functional connectivity patterns. Researchers significantly predicted performance on the Psychometric Entrance Test—a standardized exam used for university admissions—including global scores and specific cognitive domains (quantitative reasoning, verbal reasoning, and foreign language proficiency) [6]. This demonstrates that functional connectomes capture real-world variability in both global and domain-specific cognitive abilities, emphasizing their potential as objective markers of real-world cognitive performance with substantial implications for educational and clinical applications [6].

Figure 2: Applications and implications of functional connectome fingerprinting

Critical Methodological Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Key Factors Influencing Fingerprint Accuracy

Several technical and methodological factors significantly impact fingerprinting accuracy. Scan duration profoundly affects reliability, with longer acquisitions naturally providing more stable connectivity estimates, though advanced methods like DNNs can achieve remarkable accuracy with windows as brief as 15 seconds [3]. The choice of pairwise interaction statistic substantially alters resulting FC matrices and their downstream identifiability, with precision-based and covariance-based methods generally outperforming others for both identification and structure-function coupling [4].

The selection of functional networks included in analysis dramatically influences discriminative power. The frontoparietal network emerges consistently as the most distinctive for individual identification, with the combination of medial frontal and frontoparietal networks significantly outperforming either network alone or whole-brain connectivity [1]. Edgewise analysis reveals that connections with high differential power (ability to distinguish individuals) predominantly involve frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, particularly within and between frontoparietal networks and default mode network [1].

Addressing Reproducibility and Generalizability

The reproducibility of functional connectome fingerprints across sessions and tasks establishes their reliability as intrinsic brain features [1]. Successful identification across scan sessions and even between task and rest conditions confirms that an individual's connectivity profile is intrinsic, and can be used to distinguish that individual regardless of how the brain is engaged during imaging [1]. Furthermore, transfer learning approaches demonstrate that models trained on one dataset can successfully identify individuals from independent datasets, supporting the feasibility of the technique across different acquisition protocols and populations [3].

For optimal fingerprint extraction, researchers should consider implementing PCA-based reconstruction to maximize identifiability [2], employing multiple connectivity metrics rather than defaulting exclusively to Pearson correlation [4], utilizing sparse DNN architectures when dealing with short time windows or high-dimensional data [3], and focusing analytical attention on frontoparietal and default mode networks which consistently demonstrate highest discriminative power [1].

The quest to understand the biological underpinnings of individual identity has led neuroscientists to investigate the brain's intrinsic functional architecture. Rather than operating as a collection of isolated regions, the brain organizes itself into large-scale intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs)—collections of widely distributed brain areas that demonstrate synchronized activity patterns during rest and task performance [7]. These ICNs provide a fundamental organizational framework for brain function, with emerging research suggesting that individual variations in these networks may serve as unique functional connectivity fingerprints that anchor individual identity [8]. The study of these networks has been revolutionized by analytical methods such as independent component analysis (ICA), which enables data-driven identification of these functional systems without a priori assumptions about their structure [9] [10].

The concept of ICNs expands upon earlier observations of resting state networks to include the set of large-scale functionally connected networks that can be identified in both resting state and task-based neuroimaging data [10]. This recognition that the brain's intrinsic functional architecture persists across both task-free and task-engaged states provides a robust foundation for investigating stable, individual-specific features of brain organization. Current neurobiological models propose that these networks represent a fundamental aspect of human brain architecture that supports cognition, emotion, perception, and action [10] [7], with their unique configurations potentially encoding the neural basis of individual differences.

The Canonical Large-Scale Brain Networks: A Reference Framework

Research converging from multiple studies has identified a core set of large-scale brain networks that consistently appear across individuals and methodologies. While different classification schemes exist, most include several well-established networks with distinct functional roles [7]. The following table summarizes the primary large-scale brain networks and their associated functions:

Table 1: Canonical Large-Scale Brain Networks and Their Functions

| Network Name | Core Brain Regions | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, inferior parietal lobule | Self-referential thought, mind-wandering, memory retrieval, future planning [7] [11] |

| Salience Network (SN) | Anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | Detecting behaviorally relevant stimuli, switching between networks, emotional awareness [7] [11] |

| Executive Control Network (ECN) | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, posterior parietal cortex | Goal-directed cognition, working memory, cognitive control [7] [11] |

| Dorsal Attention Network (DAN) | Intraparietal sulcus, frontal eye fields | Voluntary, top-down attention orienting [7] |

| Sensorimotor Network (SMN) | Precentral and postcentral gyri | Somatosensory processing and motor coordination [7] |

| Visual Network (VN) | Occipital cortex regions | Visual information processing [7] |

| Limbic Network | Amygdala, hippocampus, ventral prefrontal regions | Emotional processing, memory formation [7] |

These networks do not operate in isolation but rather interact in a carefully coordinated manner. The triple network model—focusing on the dynamic interactions between the default mode, salience, and executive control networks—has proven particularly valuable for understanding how the brain switches between internal and external focus, and how these interactions may be disrupted in various neuropsychiatric conditions [11].

Methodological Foundations: Mapping the Brain's Intrinsic Architecture

Analytical Approaches for Network Identification

The identification and characterization of intrinsic brain networks relies on sophisticated analytical approaches that can detect synchronized activity patterns across the brain. The primary methods include:

Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A blind source separation technique that decomposes neuroimaging data into maximally independent spatial components and their associated time courses [9]. ICA can be applied at the individual or group level, with spatial group-ICA (sgr-ICA) providing a robust framework for identifying shared functional networks across individuals [9]. This data-driven approach does not require a priori seed selection and can reveal novel network configurations.

Seed-Based Functional Connectivity: This hypothesis-driven approach calculates temporal correlations between a pre-defined seed region and all other brain voxels. While powerful for testing specific hypotheses about network connections, it depends critically on accurate seed selection and may miss complex, distributed network patterns [7].

Graph Theoretical Approaches: These methods represent the brain as a collection of nodes (brain regions) and edges (connections between them), enabling quantification of network properties such as modularity, efficiency, and hub identification [7]. This approach facilitates comparison with other complex networks and provides metrics for individual differences.

High-Order ICA for Fine-Grained Network Parsellation

Traditional ICA applications typically used lower-order models (20-45 components) that identified broad, large-scale networks [9]. However, advances in computational power and the availability of large datasets have enabled very high-order ICA models that parse the brain into hundreds of distinct components. For example, a recent study applied group-ICA with 500 components to more than 100,000 subjects, generating a robust, fine-grained ICN template called NeuroMark-fMRI-500 [9].

This high-order approach reveals functionally distinct subnetworks embedded within larger-scale systems. For instance, the cerebellar region, often treated as a relatively homogeneous area in lower-order models, can be parsed into multiple fine-grained components with distinct connectivity patterns [9]. This enhanced granularity improves the detection of disease-related connectivity differences and provides a more detailed framework for identifying individual-specific network features.

Table 2: Comparison of ICA Model Orders and Their Applications

| ICA Model Order | Spatial Resolution | Primary Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Order (20-45 components) | Identifies broad, large-scale networks | Initial network characterization, clinical studies with smaller sample sizes | Limited granularity, misses finer network subdivisions |

| Medium-Order (75-200 components) | Reveals intermediate-scale networks and major subnetworks | Detailed mapping of network architecture, individual differences research | May miss highly specialized subnetwork regions |

| High-Order (500+ components) | Parses networks into fine-grained, functionally specific components | Creating detailed network templates, detecting subtle disease effects, fingerprinting studies | Requires very large sample sizes, computational intensity |

Experimental Protocol: Large-Scale Network Analysis with High-Order ICA

The following experimental workflow outlines the protocol for conducting high-order ICA analysis of intrinsic brain networks, based on methodologies described in the search results [9]:

Data Acquisition and Quality Control

- Acquire resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) data with a minimum of 120 time points (volumes)

- Apply rigorous quality control: mean framewise displacement < 0.25 mm, head motion transitions within 3mm

- Address inter-site variability through standardized preprocessing when using multi-site datasets

Preprocessing Pipeline

- Perform standard preprocessing: slice timing correction, realignment, normalization to standard space

- Apply additional preprocessing: band-pass filtering (typically 0.01-0.1 Hz), regression of nuisance variables (white matter, CSF, motion parameters)

Group-Level ICA Decomposition

- Concatenate preprocessed data across subjects

- Perform dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis

- Apply ICA algorithm (e.g., Infomax, FastICA) at specified model order (e.g., 500 components)

- Estimate spatial independent components and associated time courses

Component Identification and Classification

- Identify components corresponding to neural networks (vs. artifacts) through visual inspection and automated template matching

- Classify components into established network categories using atlases or template matching algorithms

- For fine-grained templates (e.g., NeuroMark-fMRI-500), organize and label networks using terminology familiar to cognitive and affective neuroscience

Network Connectivity Analysis

- Calculate functional network connectivity (FNC) as correlations between component time courses

- Compare connectivity patterns between groups or correlate with behavioral measures

- Perform statistical analysis with appropriate multiple comparisons correction

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for intrinsic network analysis using high-order ICA. The process flows from data acquisition through network identification to individual fingerprinting applications.

Intrinsic Networks as Individual Identity Anchors: Evidence and Mechanisms

Individual Variability in Network Organization

The concept of intrinsic brain networks as identity anchors stems from growing evidence that individuals possess unique and stable patterns of functional network organization. Several key principles support this framework:

Spatial Variability: While large-scale networks show consistent organization across individuals, their precise spatial boundaries and topography vary in individually specific ways [8]. These spatial differences are not random noise but represent meaningful variations that correlate with behavior and cognitive abilities.

Connectional Fingerprints: The strength of connections within and between networks creates a unique pattern for each individual. One study demonstrated that very high-order ICA (500 components) could capture fine-grained connectivity patterns that differentiated individuals with schizophrenia from healthy controls with high accuracy [9].

Temporal Dynamics: The brain's functional architecture is not static but dynamically reconfigured over time [12]. Individuals show characteristic patterns in how their networks transition between different connectivity states, providing another dimension for individual identification [12].

Contextual Connectivity: The Dynamic Framework of Network Interactions

A recent framework termed contextual connectivity proposes that canonical static networks are actually superordinate approximations of underlying dynamic states [12]. According to this model, each network can resolve into multiple network connectivity states (NC-states) that occur in specific whole-brain contexts. This dynamic perspective bridges the gap between static network models and fully time-varying approaches, providing a more comprehensive foundation for understanding individual differences in brain organization [12].

The dynamic nature of network organization does not undermine its potential as an identity anchor; rather, it adds another dimension of individual specificity. Studies have shown that individuals exhibit characteristic patterns in how their networks transition between different connectivity states, with these dynamic features potentially providing more discriminative power for individual identification than static connectivity alone [12].

Diagram 2: Contextual connectivity framework. Whole-brain states (blue rectangles) provide context for specific network connectivity states within canonical networks (colored circles), creating a hierarchical organization of brain dynamics.

Clinical Applications: Network Alterations in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

The utility of intrinsic networks as identity anchors is particularly evident in clinical neuroscience, where distinct network alterations have been identified across various neuropsychiatric conditions:

Table 3: Network Dysconnectivity Patterns in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

| Disorder | Key Network Alterations | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Hypoconnectivity between cerebellar and subcortical domains; hyperconnectivity between cerebellar and visual/sensorimotor domains [9]; triple network dysfunction [9] | Impaired information integration, cognitive deficits, hallucinations |

| Cocaine Use Disorder | Stronger SN-aDMN and ECN-aDMN connectivity; disrupted subcortical-network connectivity [11] | Executive dysfunction, craving, emotional dysregulation |

| Methamphetamine Dependence | Gray matter reductions in default mode, cognitive control, salience networks; differential basal ganglia-network connectivity patterns [13] | Cognitive impairment, compensatory network reorganization |

| Depression, Alzheimer's, Autism | Disruptions in triple network interactions and default mode network integrity [7] | Domain-specific cognitive and emotional deficits |

These disorder-specific network "fingerprints" not only advance our understanding of disease mechanisms but also hold promise for developing biomarkers for diagnosis, treatment selection, and monitoring treatment response. For example, a classifier based on triple network connectivity achieved 77.1% accuracy in distinguishing individuals with cocaine use disorder from controls [11], demonstrating the discriminative power of network-based approaches.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Intrinsic Network Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Software | FSL MELODIC ICA, GIG-ICA, CONN toolbox | Data preprocessing, ICA decomposition, connectivity analysis |

| Network Templates | NeuroMark-fMRI-500, Yeo 17-network atlas | Reference for component identification, network classification |

| Data Resources | UK Biobank, ADNI, Human Connectome Project | Large-scale datasets for method validation, individual differences research |

| Quality Control Metrics | Framewise displacement, DVARS, FIX classifier | Assessing data quality, identifying motion artifacts |

| Statistical Approaches | Network-based statistic, graph theory metrics, dynamic connectivity | Identifying significant group differences, characterizing network properties |

| Visualization Tools | BrainNet Viewer, Connectome Workbench | Visualizing network maps, connection patterns |

The conceptualization of intrinsic brain networks as identity anchors represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience, moving beyond localized brain regions to distributed network systems as the fundamental units of brain organization and individual differences. The development of high-order ICA approaches, combined with large-scale datasets and dynamic connectivity frameworks, has provided unprecedented resolution for parsing the brain's functional architecture and its individual variations.

The emerging evidence suggests that each individual possesses a unique pattern of functional network organization and dynamics that remains stable over time yet adapts to changing cognitive demands and life experiences. This network fingerprint is not merely a biological curiosity but has profound implications for understanding the neurobiological basis of individuality, including variations in cognitive abilities, emotional processing, and vulnerability to neuropsychiatric disorders.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances offer new pathways for developing network-based biomarkers for diagnosis, treatment selection, and monitoring therapeutic response. The ability to precisely map an individual's unique network architecture brings us closer to personalized neuroscience approaches that respect the biological individuality of each person's brain while identifying common principles of brain organization that unite us as a species.

The human brain operates through the dynamic interplay of large-scale, intrinsic networks. Among these, the Frontoparietal Network (FPN) and the Default Mode Network (DMN) play critical and distinct roles in cognitive processes. The FPN is central to goal-directed behavior, cognitive control, and working memory, acting as a flexible hub that coordinates other brain networks [14]. In contrast, the DMN is most active during rest and supports self-referential thought, autobiographical memory, and mental simulation [15] [16]. A key feature of their relationship is their typical anti-correlation; during demanding cognitive tasks, the FPN activates while the DMN deactivates, a dynamic thought to be crucial for focused attention [17]. Disruptions in the connectivity within and between these networks are increasingly recognized as transdiagnostic biomarkers for a range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD) [18] [19]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the FPN and DMN, detailing their distinct functional profiles, the experimental data that delineates them, and the methodologies used to map their intricate landscape.

Comparative Functional Profiles: FPN vs. DMN

Table 1: Core Functional Characteristics of the FPN and DMN.

| Feature | Frontoparietal Network (FPN) | Default Mode Network (DMN) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functions | Cognitive control, working memory, task initiation, goal-directed attention, flexible hub function [14] | Self-referential thought, autobiographical memory, mind-wandering, envisioning the future, theory of mind [15] [16] |

| Key Anatomical Nodes | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (dlPFC), Intraparietal Sulcus (IPS), Lateral Prefrontal Cortex [18] [14] | Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC), Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC)/Precuneus, Angular Gyrus [15] [16] |

| Typical Activity State | Activated during externally-focused, cognitively demanding tasks [14] [20] | Activated during rest and internally-focused mental states; deactivated during demanding external tasks [15] [17] |

| Network Relationship | Anti-correlated with DMN during tasks; interacts with and modulates other networks [14] [17] | Anti-correlated with FPN during tasks; dynamically interacts with Salience and Executive networks [16] [20] |

| Role in Psychopathology | Dysconnectivity linked to cognitive impairments in schizophrenia, ADHD, and mood disorders [18] [14] | Hyperconnectivity and failure to deactivate linked to rumination in MDD and self-referential deficits in schizophrenia [15] [19] |

Direct Comparative Evidence: Network Dysconnectivity in Affective Disorders

A direct comparison of functional connectivity (FC) in first-episode bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) reveals distinct dysconnectivity patterns, offering insights into their unique pathophysiologies.

Table 2: Distinct Functional Connectivity Patterns in First-Episode Affective Disorders.

| Connectivity Measure | Bipolar Disorder (BD) Pattern | Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Characterization | More extensive functional dysconnectivity, involving both within- and between-network alterations [18] [21] | More localized functional dysconnectivity, confined primarily to the anterior DMN [18] [21] |

| Within-Network DMN FC | Increased FC (hyperconnectivity) between ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) and occipital region [18] | Increased FC only within the anterior DMN (vmPFC, superior frontal cortex, ventrolateral PFC) [18] |

| Within-Network FPN FC | Increased FC between ventral anterior PFC and intraparietal sulcus [18] | Not reported as a prominent feature in first-episode cases [18] |

| Between-Network FC (FPN-DMN) | Increased FC between ventral anterior PFC and occipital region, and between ventral PFC and precuneus [18] | Not reported as a prominent feature in first-episode cases [18] |

| Associated Cognitive Deficit | Correlated with greater cognitive impairment, particularly in executive function (e.g., percent perseverative errors on WCST) [18] | Less severe cognitive impairment compared to BD at first episode [18] |

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

- Protocol Purpose: To map intrinsic functional connectivity within and between the FPN and DMN by measuring spontaneous, low-frequency fluctuations in the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal while the subject is at rest [18] [15].

- Detailed Workflow:

- Participant Preparation: Participants are instructed to lie still in the scanner with their eyes open or closed, fixating on a cross-hair, without engaging in any structured task.

- Data Acquisition: High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images are acquired, followed by a 5-10 minute resting-state functional scan using an echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence.

- Preprocessing: Data undergoes slice-timing correction, realignment for head motion correction, normalization to a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI), and spatial smoothing.

- Seed-Based FC Analysis: A seed region (e.g., in the vmPFC for the DMN) is defined. The average BOLD time series from this seed is correlated with the time series of every other voxel in the brain to generate a connectivity map [15].

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A data-driven approach used to identify large-scale networks like the FPN and DMN without a priori seed selection [20].

- Statistical Analysis: Group-level comparisons (e.g., patients vs. controls) are conducted on connectivity strength to identify significant alterations.

Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) with fMRI

- Protocol Purpose: To establish a causal link between frontoparietal synchronization and working memory performance, and to visualize the underlying neural effects using fMRI [22].

- Detailed Workflow:

- Stimulation Setup: Theta-frequency (6 Hz) tACS is applied simultaneously to two key nodes of the right FPN: the middle frontal gyrus (MFG) and the inferior parietal lobule (IPL). Conditions include synchronous (0° phase lag) and desynchronous (180° phase lag) stimulation, alongside a sham control.

- Task Paradigm: Participants perform a verbal N-back task (e.g., 1-back and more demanding 2-back) and a simple choice reaction time task inside the fMRI scanner during stimulation.

- fMRI Acquisition & Analysis: BOLD signals are collected concurrently. General Linear Model (GLM) analysis identifies task-related activation. Functional connectivity between FPN nodes is assessed using psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis.

- Behavioral Correlation: Changes in reaction time and accuracy on the 2-back task are correlated with tACS-induced changes in BOLD activity and connectivity [22].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) for Network Connectivity

- Protocol Purpose: To assess the functional connectivity of the FPN during rest and complex task performance using a portable, non-invasive optical neuroimaging technology [23].

- Detailed Workflow:

- Optode Placement: fNIRS optodes are positioned over the frontal and parietal cortices based on the international 10-20 system to cover the FPN.

- Resting-State Recording: Participants undergo a 5-minute resting-state recording while fixating on a crosshair.

- Task Performance: Participants engage in a complex task, such as the Space Fortress video game, which demands working memory, attention, and cognitive control.

- Data Processing: The concentration changes of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) are calculated. The time series data from different channels are used to compute functional connectivity metrics, such as correlation coefficients, within the FPN.

- Prediction Analysis: The strength of resting-state FPN connectivity is used as a predictor for subsequent complex task performance [23].

Clinical and Translational Applications

The distinct connectivity patterns of the FPN and DMN serve as critical biomarkers for understanding and diagnosing neuropsychiatric conditions. In Alzheimer's disease (AD), the DMN shows decreased activity and connectivity, closely overlapping with regions of amyloid plaque deposition, making it a promising early diagnostic biomarker [15] [19]. In contrast, conditions like schizophrenia and depression are often characterized by DMN hyperconnectivity and a failure to deactivate during tasks, which correlates with symptoms like rumination and impaired attention [15]. The competitive relationship between the FPN and DMN is crucial for optimal cognitive performance; when this anti-correlation breaks down, as observed in several disorders, it leads to attention lapses and poor task performance [17]. Furthermore, interventions such as pharmacological treatments and meditation have been shown to modulate DMN activity and FPN-DMN connectivity, suggesting these networks are viable targets for therapeutic development [15] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for FPN/DMN Research.

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Equipment | 3T/7T fMRI Scanner, fNIRS System, EEG/MEG System | Measures neural activity (BOLD signal, hemodynamic response, electrical activity) to map network connectivity and dynamics [18] [23]. |

| Stimulation Devices | Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS), Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | Provides causal intervention by exogenously modulating oscillatory activity in target networks to study effects on behavior and connectivity [22]. |

| Analysis Software & Suites | SPM, FSL, CONN, DPABI, MATLAB Toolboxes | Processes and analyzes neuroimaging data for preprocessing, statistical modeling, and functional connectivity calculation [18] [20]. |

| Cognitive Task Paradigms | N-back Task, Space Fortress, Resting-State Paradigm, Emotional Face Recognition Tasks | Engages specific cognitive functions (working memory, cognitive control) to probe FPN and DMN activity under controlled conditions [18] [17] [23]. |

| Standardized Atlases & ROIs | Dosenbach's 160 ROI Atlas, Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) Atlas, Harvard-Oxford Atlas | Provides standardized definitions of brain regions for seed-based connectivity analysis and network quantification [18]. |

The discovery that an individual's pattern of brain connectivity can serve as a unique "fingerprint" has established a new frontier in cognitive neuroscience. Functional connectome fingerprinting leverages the fact that the pattern of functional connections between brain regions is both unique to each individual and stable over time, enabling remarkable accuracy in identifying individuals from a population [24]. While initial groundbreaking work demonstrated this principle using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the field has rapidly expanded to investigate whether these neural fingerprints can be consistently detected across different neuroimaging modalities, each with its own distinct physiological basis and technical characteristics [25] [26] [27]. This cross-modal validation is crucial not only for confirming the fundamental biological reality of brain fingerprints but also for translating this knowledge into practical applications across various settings, from clinical monitoring to pharmacological research.

The core hypothesis driving this field is that an individual's functional connectome (FC)—a comprehensive map of statistical dependencies between neural signals across different brain regions—contains idiosyncratic features that are as distinctive as a traditional fingerprint [28]. This review synthesizes evidence from three prominent neuroimaging techniques: fMRI, celebrated for its high spatial resolution; magnetoencephalography (MEG), which captures neurophysiological activity with millisecond temporal precision; and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), an emerging portable technology that measures cortical hemodynamics. By comparing the replicability of functional connectome fingerprints across these modalities, we provide a comprehensive assessment of the current state of cross-modal individual identification and its promising applications in neuroscience and medicine.

Experimental Evidence Across Modalities

fMRI Fingerprinting: The Gold Standard

Functional MRI has served as the foundation for connectome fingerprinting research, establishing benchmark performance levels against which other modalities are compared. The methodology typically involves calculating correlation matrices from blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) time series to represent functional connectivity between brain regions, which then serve as input for identification algorithms.

Table 1: fMRI Fingerprinting Performance Characteristics

| Study | Subjects | Conditions | Accuracy | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finn et al. (2015) [24] | 1,206 | Resting-state & tasks | >90% | Established FC fingerprints as a reliable biometric |

| Cai et al. (2021) [24] | 862 | Resting-state pairs | 99.5% | Used autoencoder to enhance uniqueness |

| Kaufmann et al. (2017) [24] | Adolescents | Longitudinal | High | Found fingerprints stabilize during development |

The exceptional discriminative power of fMRI-based fingerprints stems from the concentration of unique connectivity profiles in higher-order association cortices, particularly the frontoparietal network (FPN) and default mode network (DMN) [29]. These networks exhibit the highest degree of inter-individual variability, providing the most distinctive features for identification. Furthermore, refinement techniques using autoencoder networks with sparse dictionary learning have successfully enhanced the uniqueness of individual connectomes by removing contributions from shared neural activities across individuals, pushing identification accuracy to nearly perfect levels (99.5% for rest-rest pairs) [24].

MEG Fingerprinting: The Temporal Dimension

MEG fingerprinting extends the concept into the domain of direct neurophysiological measurement, capturing the brain's rich electrophysiological dynamics with exceptional temporal resolution. The identification pipelines for MEG data typically involve either functional connectomes derived from phase-coupling measures or simpler spectral power features across frequency bands.

Table 2: MEG Fingerprinting Performance Across Studies

| Study | Subjects | Features | Accuracy | Temporal Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| da Silva Castanheira et al. (2021) [26] | 158 | FC & PSD | 94.9%-96.2% | Stable over weeks/months |

| Sareen et al. (2021) [27] | HCP Dataset | Phase-coupling | Variable by band | Higher in alpha/beta bands |

| Demeter et al. (2023) [30] | Multiple | Task vs. rest | Task > Rest | Improved in controlled tasks |

Seminal work by da Silva Castanheira and colleagues demonstrated that both functional connectomes and power spectral density (PSD) estimates enable individual differentiation with accuracies rivaling fMRI (94.9% for connectomes, 96.2% for spectral features) [26]. Notably, their research revealed several distinctive advantages of MEG fingerprinting: successful identification from brief 30-second recordings, robustness across test-retest intervals averaging 201.7 days, and consistently high performance across frequency bands—with narrowband connectome fingerprinting achieving perfect (100%) accuracy in theta and beta bands [26]. Furthermore, task-based MEG recordings have demonstrated improved identifiability compared to resting-state, with strictly controlled tasks providing the most distinctive individual signatures [30].

fNIRS Fingerprinting: Portability and Practicality

As a relatively portable and cost-effective technology, fNIRS presents an attractive alternative for real-world fingerprinting applications. fNIRS measures cortical hemodynamics through changes in oxygenated (Oxy-Hb) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (Deoxy-Hb) concentrations, providing a physiological signal conceptually similar to fMRI but with practical advantages for specific populations and settings.

Research by PMC (2022) investigated whether fNIRS-based brain functional networks could serve as reliable fingerprints across different tasks (resting state, right-handed tapping, left-handed tapping, and foot tapping) [25]. Their experimental pipeline involved calculating Pearson's correlation-based functional connectivity from preprocessed fNIRS signals, followed by nearest-neighbor matching. The results demonstrated that cross-task identification worked generally well, with an interesting finding that accuracy under cross-task conditions was significantly higher than under cross-view conditions (comparing Oxy-Hb and Deoxy-Hb signals) [25]. This suggests that task-based functional patterns may provide more stable biometric features than the differential hemodynamic responses captured by separate oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin measurements.

The portability, relative motion tolerance, and lower cost of fNIRS systems make them particularly suitable for fingerprinting applications in special populations such as infants, children, and clinical populations where fMRI is impractical [31]. Furthermore, the ability to perform longer monitoring and repeated measurements in more naturalistic environments positions fNIRS as a promising modality for tracking connectome stability and changes in real-world contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Experimental Protocols and Technical Considerations

Each neuroimaging modality requires specialized experimental protocols and analytical approaches to optimize fingerprinting performance, reflecting their distinct technical foundations and physiological sensitivities.

fMRI Protocols utilize the high spatial resolution of BOLD contrast imaging, typically employing multiband sequences (e.g., TR/TE=720/33.1ms) to capture whole-brain connectivity patterns [24]. The HCP-style protocols involve multiple resting-state and task-based conditions (working memory, motor, language, emotion) to capture comprehensive connectivity profiles. Preprocessing pipelines emphasize motion correction, spatial normalization, and global signal regression, with connectivity typically quantified through Pearson correlation between regional time series.

MEG Protocols leverage the millisecond temporal resolution of neurophysiological signals, requiring sophisticated source modeling to resolve spatial patterns. Studies typically employ Elekta Neuromag or CTF systems with 300+ sensors inside magnetically shielded rooms [26] [27]. The analytical workflow includes empty-room noise recording, signal space separation for artifact suppression, beamforming or minimum-norm estimation for source localization, and functional connectivity estimation through phase-based metrics (phase-locking value, imaginary coherence) or amplitude correlations within standard frequency bands.

fNIRS Protocols balance practical considerations with signal quality, using systems like LIGHTNIRS with multiple sources and detectors (typically 8×8 forming 20 channels) placed over targeted cortical regions [25]. The preprocessing chain involves converting optical density to hemoglobin concentrations via modified Lambert-Beer law, band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1Hz) to remove physiological noise, and baseline correction. Connectivity is then estimated through Pearson correlation between channel-wise hemodynamic time series.

Cross-Modal Concordance and Validation

Multimodal imaging studies provide direct evidence for the convergent validity of connectome fingerprints across different measurement techniques. Huppert and colleagues conducted simultaneous fNIRS-fMRI and fNIRS-MEG recordings during somatosensory stimulation, finding good spatial correspondence among the modalities (R=0.54-0.80 for amplitude correlations) [32]. The majority of differences across modalities were attributed to differential sensitivity to deeper brain sources, with MEG and fNIRS showing reduced sensitivity compared to fMRI for subcortical structures.

Sareen et al. conducted comprehensive cross-modality fingerprinting comparisons between MEG and fMRI, revealing certain degrees of spatial concordance, particularly within the visual system [27]. This suggests that despite measuring different physiological phenomena (electrophysiological activity versus hemodynamic responses), the resulting functional connectomes capture overlapping aspects of individual brain organization.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The fingerprinting process across modalities follows a shared conceptual workflow while employing modality-specific data processing techniques, as illustrated below.

Figure 1: Cross-Modal Fingerprinting Workflow

This unified workflow demonstrates the shared conceptual framework while highlighting modality-specific feature extraction approaches that capitalize on each technique's unique strengths.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Successful implementation of connectome fingerprinting requires careful selection of analytical components and research reagents tailored to each modality's characteristics.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Connectome Fingerprinting

| Component | Function | Modality Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Preprocessing Toolkits | BBCI toolkit (fNIRS) [25], FSL/FMRIPREP (fMRI), FieldTrip/Brainstorm (MEG) | Critical for artifact removal and signal quality enhancement |

| Connectivity Metrics | Pearson correlation (fMRI/fNIRS) [25], Phase-based measures (MEG) [27] | Determines functional network estimation quality |

| Parcellation Atlases | Desikan-Killiany (MEG) [26], Yeo networks (fMRI) [29] | Standardizes regional definitions across studies |

| Identification Algorithms | Nearest neighbor [25], Differential identifiability [27], Tangent space projection [33] | Directly impacts fingerprinting accuracy |

| Validation Frameworks | Within/between-session differentiation [26], Cross-task identification [25] | Ensures reliability and generalizability |

The selection of appropriate functional connectivity measures is particularly crucial, with fingerprinting performance heavily dependent on this choice across all modalities. For MEG data, phase-coupling methods generally outperform amplitude-based measures, with the highest identification success rates observed in central frequency bands (alpha and beta) [27]. For fMRI and fNIRS, standard Pearson correlation provides robust results, though advanced sparse coding approaches can enhance individual uniqueness [24].

Advanced dimensionality reduction techniques have emerged as powerful tools for enhancing fingerprinting performance. Tensor decomposition methods like Tucker decomposition significantly increase matching rates compared to approaches that don't model the high-dimensionality of functional connectivity data, particularly for lower parcellation granularities [33]. Similarly, Riemannian geometry-based methods using tangent space projection enable more robust comparisons by accounting for the non-Euclidean nature of connectivity matrices [33].

Implications for Basic Research and Pharmaceutical Applications

The demonstrated cross-modal replicability of functional connectome fingerprints has profound implications for both basic neuroscience and applied pharmaceutical research, particularly in the emerging field of pharmacological brain fingerprinting.

In basic research, the robustness of individual identification across fMRI, MEG, and fNIRS provides compelling evidence that functional connectomes reflect fundamental, modality-independent properties of brain organization. This strengthens the theoretical foundation for investigating how these individual connectivity patterns emerge from genetic and environmental factors, how they stabilize across development, and how they relate to cognitive traits and behavioral variability [29]. The observation that discriminatory and predictive connections may represent distinct functional systems [29] opens new avenues for understanding the relationship between brain individuality and behavior.

In pharmaceutical research, pharmacological brain fingerprinting represents a promising approach for understanding individual variability in drug response. Recent work has demonstrated that psilocybin alters functional connectome fingerprints, making them more idiosyncratic and shifting distinctive features toward the default mode network [28]. This reconfiguration predicted subjective drug experiences, illustrating how fingerprinting approaches can bridge neural and phenomenological responses to pharmacological interventions. The portability of fNIRS makes it particularly suitable for monitoring these fingerprint changes in naturalistic settings or across multiple timepoints in clinical trials.

The convergent evidence across fMRI, MEG, and fNIRS modalities firmly establishes functional connectome fingerprinting as a robust, cross-validated phenomenon with significant implications for basic and applied neuroscience. While each modality offers distinct advantages—fMRI with superior spatial resolution, MEG with unmatched temporal precision, and fNIRS with practical portability—their collective ability to identify individuals based on unique connectivity patterns underscores the biological reality and stability of these neural fingerprints.

The cross-modal replication of fingerprinting effects represents more than methodological validation; it provides a foundational framework for future research into individualized brain function across health and disease. As analytical techniques continue to evolve, particularly through advanced dimensionality reduction and geometric approaches, the precision and utility of connectome fingerprints will likely increase, opening new possibilities for personalized medicine, pharmaceutical development, and fundamental understanding of what makes each human brain unique.

The concept of a "fingerprint" has transcended its dermatological origins to become a fundamental principle in biometrics and neuroscience, representing any stable, unique signature that can reliably identify an individual over time. The core premise of any fingerprinting system rests on two pillars: uniqueness (the signature differs between individuals) and persistence (the signature remains stable within an individual over time). While uniqueness has received considerable scientific attention, the question of long-term persistence—particularly over years—remains a critical area of investigation. Understanding the temporal stability of fingerprints is essential for advancing reliable biometric authentication systems, developing robust brain-based biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric disorders, and validating the forensic science that underpins modern identification methodologies. This guide objectively compares the evidence for long-term persistence across three key fingerprint modalities: physical fingerprints, functional brain fingerprints, and electrophysiological brain fingerprints, providing researchers with a synthesis of quantitative data, experimental protocols, and key reagents.

Comparative Evidence for Fingerprint Persistence Across Modalities

The evidence for long-term persistence varies significantly across different fingerprint modalities. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of key studies, highlighting the methods, time spans, and stability metrics reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Long-Term Fingerprint Persistence Across Modalities

| Fingerprint Modality | Specific Measure | Time Span Studied | Key Stability Metric | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Brain (fMRI) | Functional Connectome (FC) | Multiple sessions (varies) | Matching Rate (Within-condition) | 11-36% improvement using Tucker decomposition | [34] |

| Functional Connectome (FC) | Multiple sessions (varies) | Matching Rate (Between-condition) | 43-72% improvement using Tucker decomposition | [34] | |

| Electrophysiological (EEG) | Frontal Lobe Alpha Coherence | Avg. 7.11 ± 4.56 years | Interannual Canonical Correlation | 0.792 | [35] [36] |

| Whole-Brain Data Variance | Avg. 7.11 ± 4.56 years | Shared Variance | 62.7% | [35] [36] | |

| Occipital Lobe Beta Coherence | Avg. 7.11 ± 4.56 years | Remarkable Correlation | Not specified | [35] [36] | |

| Physical Fingerprints | Fingerprint Similarity (Genuine Scores) | Up to 12 years | Trend in Match Scores | Significant decrease with increasing time interval | [37] |

| Fingerprint Recognition Accuracy | Up to 12 years | Operational Stability | Stable accuracy up to 12 years | [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Long-Term Persistence

Protocol for EEG Coherence Fingerprinting

This protocol is designed to assess the long-term stability of EEG coherence patterns, which reflect the functional connectivity between different brain regions.

- Objective: To examine the persistence of EEG coherence in delta, theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands across interhemispheric spatial domains and over extended interannual periods [35] [36].

- Participants: 28 participants with no history or presence of major neurological or psychiatric disorders [36].

- Data Acquisition:

- Equipment: EEG recordings are performed according to the 10-20 international electrode placement system.

- Procedure: Each participant undergoes at least two EEG recording sessions separated by a long-term interval. In the cited study, the average interval was 7.11 ± 4.56 years, with a range from 1.88 to 19.19 years [35] [36].

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Data is filtered and cleaned of artifacts.

- Feature Extraction: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) coherence is calculated for fundamental brain waves (delta, theta, alpha, beta) across different brain lobes (frontal, occipital, etc.) [35] [36].

- Stability Analysis:

- Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA): Used to measure the relationship between the first and second EEG recordings. A high correlation indicates strong temporal stability [35] [36].

- Variance Sharing: The proportion of shared variance between the two sessions is calculated to quantify information overlap [35] [36].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this experimental protocol:

Protocol for Functional Connectome Fingerprinting via Tensor Decomposition

This protocol uses advanced tensor decomposition to extract a unique signature from functional MRI (fMRI) data, assessing its stability across different cognitive states and over time.

- Objective: To uncover the functional connectome (FC) fingerprint of individuals using Tucker tensor decomposition and assess its accuracy in within- and between-condition matching [34].

- Participants & Data: 426 unrelated participants from the Young-Adult Human Connectome Project (HCP) dataset, which includes resting-state and task-based fMRI [34].

- Data Processing:

- Parcellation: The brain is divided into multiple regions (e.g., 100, 200, 300) using a standard atlas.

- FC Matrix Estimation: For each participant and session, a Functional Connectome (FC) matrix is estimated by calculating the correlation between the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) time series of every pair of brain regions. This results in a symmetric matrix of dimensions

Number of Brain Regions x Number of Brain Regions[34].

- Tensor Construction and Analysis:

- Tensor Building: FC matrices from all participants in the first acquisition session are concatenated to form a 3D tensor of dimensions

Regions x Regions x Participants. A second tensor is built from the second session [34]. - Tensor Decomposition: The tensors are decomposed using Tucker decomposition, a higher-order principal component analysis (PCA). This yields factor matrices, including a "participants factor matrix" that acts as the unique fingerprint for each individual [34].

- Fingerprint Matching: The participant factor matrices from different sessions are compared. The matching rate—the percentage of participants correctly identified across sessions—quantifies the fingerprint's persistence [34].

- Tensor Building: FC matrices from all participants in the first acquisition session are concatenated to form a 3D tensor of dimensions

The logical relationship and workflow of this protocol are summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successfully conducting persistence studies requires a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table details essential components for research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Fingerprint Persistence Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| EEG System with 10-20 Electrodes | Records electrical activity from the scalp; essential for EEG coherence studies. | Used to collect initial and follow-up EEG data years apart to measure interannual coherence [35] [36]. |

| fMRI Scanner (3T+) | Acquires Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) signals for mapping brain activity. | The customized Siemens 3T "Connectome Skyra" scanner used in the HCP project [38] [34]. |

| Biometric Data Processing Software | Processes raw fingerprint images and computes match scores for longitudinal analysis. | Used to analyze longitudinal fingerprint records from 15,597 subjects over 5-12 years [37]. |

| Tensor Decomposition Library | Implements Tucker and other decomposition algorithms for high-dimensional data analysis. | Critical for decomposing the functional connectome tensor to extract participant-specific factor matrices [34]. |

| Standardized Brain Parcellation Atlas | Divides the brain into distinct regions for consistent functional connectivity analysis. | Used to create granular brain maps (e.g., 214 regions) for constructing Functional Connectome (FC) matrices [34]. |

| Canonical Correlation Analysis Tool | A multivariate statistical method used to assess the relationship between two sets of variables. | Employed to measure the correlation between EEG data collected years apart [35] [36]. |

The body of evidence confirms that long-term fingerprint persistence is a measurable and robust phenomenon across multiple modalities, though the degree and nature of stability vary.

- Electrophysiological (EEG) Fingerprints demonstrate remarkable long-term stability, with frontal alpha coherence emerging as a particularly strong candidate for a neural fingerprint. The high canonical correlation (0.792) and significant shared variance (62.7%) over an average of seven years suggest that the core architecture of brain connectivity is highly stable in adults [35] [36].

- Functional Connectome (fMRI) Fingerprints show high distinctiveness, and their stability can be significantly enhanced by advanced computational methods like Tucker decomposition. This is evidenced by the 43-72% improvement in between-condition matching rates, revealing a stable neural signature that persists across different cognitive states [34].

- Physical Fingerprints present a more nuanced picture. While the underlying ridge pattern is persistent, the automated recognition of fingerprints can be influenced by time. Genuine match scores tend to decrease as the time interval between acquisitions increases, highlighting the impact of skin aging and acquisition conditions. Nevertheless, operational recognition accuracy remains stable for up to 12 years, supporting its continued use in forensic and security applications [37].

In conclusion, the evidence strongly supports the thesis that individuals possess unique signatures—whether neural or physical—that exhibit significant temporal stability over years. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the potential of stable brain fingerprints as biomarkers for tracking disease progression or therapeutic outcomes over long periods. Future work should focus on standardizing protocols and validating these persistence metrics in larger, more diverse populations, including those with neurological and psychiatric disorders.

From Data to Identity: Methodological Advances and Practical Applications

In neuroscience and psychology research, the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) has been the default statistical tool for estimating functional connectivity (FC), which quantifies the statistical relationships between brain regions' activity [39] [4]. This method is deeply embedded in analytical pipelines, with approximately 75% of connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM) studies relying solely on Pearson's r for validation [39]. However, this widespread dependence presents significant limitations for advancing individual identification and functional connectivity fingerprint research.

The Pearson correlation fundamentally measures zero-lag linear relationships between time series [4]. While computationally straightforward, this approach inherently struggles to capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics that characterize true neural interactions [39]. When used for feature selection and model evaluation in predictive modeling, Pearson's r faces three critical limitations: inability to capture complex nonlinear relationships, inadequate reflection of model errors (especially with systematic biases), and lack of comparability across datasets due to high sensitivity to data variability and outliers [39]. These limitations directly impact the reliability of functional connectome fingerprinting, where identifying stable, individual-specific patterns requires methods sensitive to the full complexity of brain network interactions.

Benchmarking 239 Pairwise Interaction Statistics

Comprehensive Framework for Comparison

A landmark 2025 benchmarking study addressed these limitations by systematically evaluating 239 pairwise interaction statistics from 49 distinct measures across six fundamental families [4]. This comprehensive analysis utilized resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from 326 unrelated healthy young adults from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) S1200 release, employing the Schaefer 100×7 atlas for regional parcellation [4]. The benchmarking examined how FC network organization varied with the choice of pairwise statistic across multiple neurophysiologically relevant properties.

Table 1: Families of Pairwise Interaction Statistics Included in Benchmark

| Statistic Family | Representative Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Covariance | Pearson's correlation | Measures zero-lag linear dependence; current standard |

| Precision | Partial correlation | Inverse covariance; emphasizes direct relationships |

| Distance | Distance correlation | Captures linear and nonlinear associations |

| Information Theoretic | Mutual information | Quantifies both linear and nonlinear dependence |

| Spectral | Coherence, Imaginary coherence | Frequency-specific interactions |

| Linear Model Fit | Slope, Correlation of residuals | Models specific relationship patterns |

The analysis revealed substantial quantitative and qualitative variation across FC methods, demonstrating that different pairwise statistics capture fundamentally different aspects of network organization [4]. While covariance-based measures (like Pearson's r) showed moderate correlation with some other families (distance correlation and mutual information), they were often highly anticorrelated with precision and distance-based measures. This divergence confirms that the choice of pairwise statistic substantially influences the resulting FC matrix configuration.

Performance Across Neurophysiological Properties

The benchmarking evaluated how effectively each statistic recapitulated well-established features of brain networks, with results demonstrating significant variability across methods [4].

Table 2: Performance of Select Statistic Families on Key Brain Network Properties

| Statistic Family | Structure-Function Coupling (R²) | Distance Relationship (∣r∣) | Individual Fingerprinting | Brain-Behavior Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariance (Pearson) | Moderate | Moderate (~0.2-0.3) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Precision | High (up to 0.25) | Moderate | High | High |

| Distance | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Information Theoretic | Variable | Variable | High | High |

| Spectral | Low | Low (<0.1) | Low | Low |

Structure-function coupling, which measures the alignment between functional connectivity and anatomical wiring (diffusion MRI-estimated structural connectivity), varied considerably across statistics [4]. Precision-based statistics, stochastic interaction, and imaginary coherence demonstrated the strongest structure-function coupling. This enhanced performance likely stems from their ability to partial out shared network influences, thereby emphasizing functional interactions more directly supported by structural connections.

The distance-relationship property, quantifying the inverse correlation between physical distance and connection strength, also showed notable variation. While most statistics displayed moderate inverse relationships (0.2 < ∣r∣ < 0.3), several exhibited weaker associations (∣r∣ < 0.1) [4]. This finding challenges the universality of this fundamental brain network property, suggesting it may be methodology-dependent.

For individual fingerprinting and brain-behavior prediction—crucial for functional connectivity fingerprint research—precision and information-theoretic statistics consistently outperformed conventional Pearson correlation [4]. These methods demonstrated enhanced capacity to differentiate individuals and predict individual differences in behavior, making them particularly valuable for personalized neuroscience applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The benchmarking study utilized data from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) S1200 release [4] [38]. The HCP acquisition protocol employed a customized Siemens 3T "Connectome Skyra" scanner with advanced motion tracking systems to minimize head movement [38]. Resting-state fMRI data were collected using a whole-brain multiband gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence optimized for imaging quality. For standardization, only fMRI data with left-to-right phase encoding were included in analyses.

Preprocessing followed HCP's minimal preprocessing pipelines, including artifact removal, motion correction, and registration to standard space [4]. Time series were extracted from the Schaefer 100×7 atlas (100 regions per hemisphere, grouped into 7 networks), though analyses were repeated across multiple atlases to ensure robustness.

Pairwise Statistic Computation

The 239 pairwise statistics were computed using the pyspi package, a comprehensive library for calculating statistical pairwise interactions from time series data [4]. The computational workflow maintained consistency across statistics through standardized implementation:

- Time series extraction for each brain region

- Pairwise computation of all selected statistics

- Matrix construction for each participant and statistic

- Quality control to ensure numerical stability

This systematic approach enabled direct comparison across diverse statistical families without confounding computational differences.

Evaluation Metrics and Validation

The benchmarking employed multiple evaluation criteria to assess each statistic's performance [4]:

- Structure-function coupling: Correlation between functional connectivity and diffusion MRI-based structural connectivity

- Individual fingerprinting: Ability to correctly identify individuals from a database using connectivity profiles

- Brain-behavior prediction: Capacity to predict individual differences in behavioral measures from connectivity patterns

- Biological alignment: Correspondence with multimodal neurophysiological networks (gene expression, receptor similarity, electrophysiology)

- Network topology: Identification of hub regions and community structure

Sensitivity analyses confirmed that findings were robust across different brain parcellations and processing choices [4].

Implications for Functional Connectivity Fingerprinting

Enhancing Individual Identification

Functional connectome fingerprinting leverages the unique patterns of brain connectivity that characterize individuals, with applications ranging from personalized treatment strategies for neurological disorders to forensic neuroscience [38]. The benchmark findings directly impact this field by identifying optimal pairwise statistics for maximizing subject identifiability.

Recent advances in fingerprinting methodologies include convolutional autoencoders and sparse dictionary learning applied to residual connectomes, which have achieved approximately 10% improvement over baseline group-averaged FC models [38]. These approaches isolate subject-specific features by subtracting shared connectivity patterns, then apply sparse coding to identify distinctive features. When combined with high-performing pairwise statistics like precision and information-theoretic measures, these methods significantly enhance fingerprint accuracy.

Cross-Condition Fingerprinting and Clinical Applications

The preservation of individual fingerprints across different cognitive states (resting-state vs. task conditions) is crucial for clinical applications. Research demonstrates that individual-specific patterns persist across both resting-state and task-based fMRI, including during working memory, motor, language, and emotion tasks [38]. This stability enables reliable identification regardless of cognitive state, though task conditions may enhance certain individual differences.

In clinical populations such as glioma patients, integrated structural-functional fingerprinting has revealed that tumors disrupt networks in both hemispheres, with left hemisphere lesions particularly altering homotopic connections in healthy tissues [40]. These disruptions are more readily detected using functional connectivity measures than structural measures alone, highlighting the importance of selecting optimal FC metrics for clinical biomarker development.

Computational Efficiency and Practical Implementation

For practical implementation in large-scale studies and clinical settings, computational efficiency is paramount. Research demonstrates that identifiability scores can be preserved with high accuracy even when sampling only 5% of functional edges through random projection methods [41]. This approach maintains statistical preservation of identifiability while dramatically reducing computational requirements, enhancing the clinical utility of functional connectomes.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Connectivity Fingerprinting

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) S1200 | Dataset | Gold-standard neuroimaging data for method development | Publicly available |

| pyspi package | Software Library | Computes 239 pairwise interaction statistics from time series | Open source |

| Schaefer 100×7 Atlas | Parcellation | Defines brain regions for network construction | Publicly available |

| PairInteraX Framework | Analytical Approach | Systematic pairwise interaction characterization | Reference implementation |

| Random Projection Algorithm | Computational Method | Reduces FC dimensionality while preserving identifiability | Custom implementation |

The comprehensive benchmarking of 239 pairwise interaction statistics demonstrates that the dominant reliance on Pearson correlation substantially limits our ability to capture the complexity of functional brain networks. Precision-based and information-theoretic statistics consistently outperform conventional Pearson correlation across multiple dimensions relevant to individual identification, including structure-function coupling, individual fingerprinting, and brain-behavior prediction [4].

For functional connectivity fingerprint research, these findings suggest that methodological optimization should be prioritized alongside analytical advances. Future directions should include:

- Task-specific statistic selection based on research objectives (e.g., precision methods for structure-function studies)

- Multi-metric evaluation frameworks that combine complementary statistics

- Development of standardized pipelines incorporating high-performing alternatives to Pearson correlation