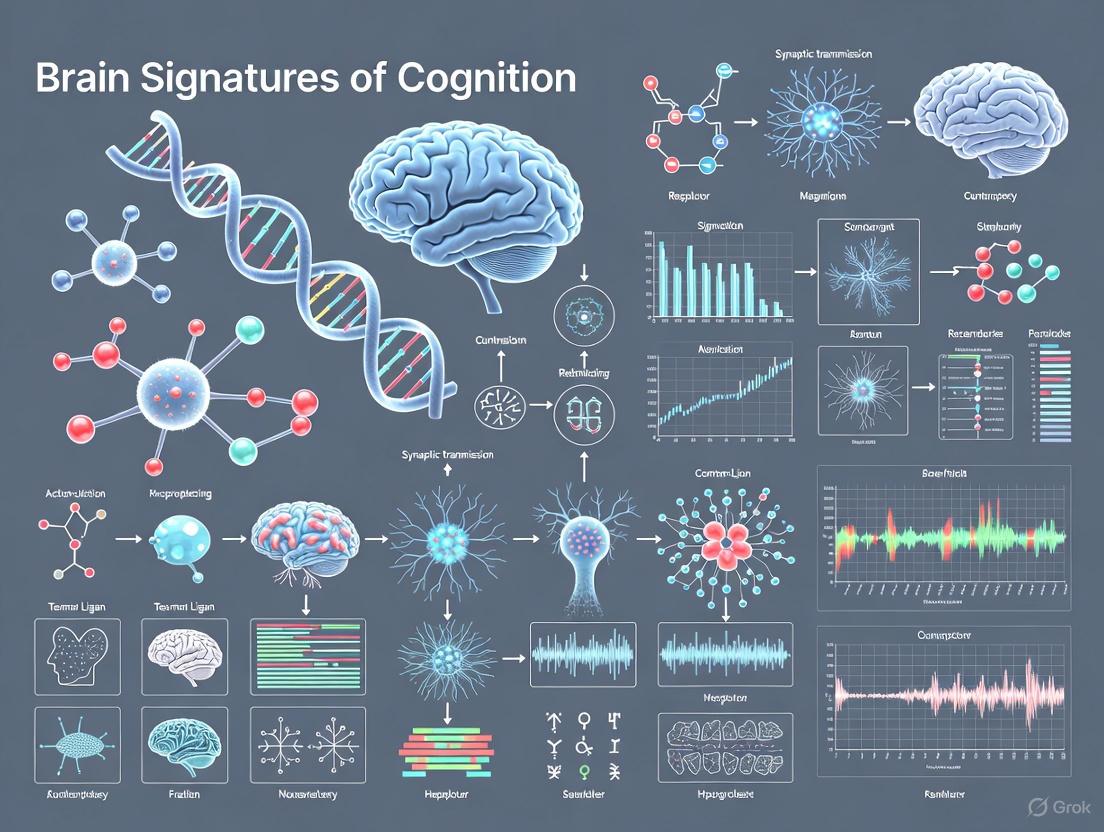

Brain Signatures of Cognition: Decoding Neural Architectures for Clinical and Research Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the 'brain signatures of cognition' concept, a data-driven approach to identify robust neural patterns associated with cognitive functions.

Brain Signatures of Cognition: Decoding Neural Architectures for Clinical and Research Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the 'brain signatures of cognition' concept, a data-driven approach to identify robust neural patterns associated with cognitive functions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational neurobiological principles revealed by large-scale imaging studies, innovative methodologies from mobile neuroimaging to machine learning, critical challenges in reproducibility and optimization, and rigorous statistical validation frameworks. By synthesizing findings from recent high-impact studies and large cohorts like the UK Biobank, we outline how validated brain signatures can serve as reliable biomarkers for understanding cognitive health, disease trajectories, and evaluating therapeutic interventions.

Mapping the Neurobiological Landscape of Human Cognition

The concept of a "brain signature of cognition" represents a fundamental evolution in neuroscience, moving from isolated theory-driven hypotheses to comprehensive, data-driven explorations of brain-behavior relationships. This paradigm shift leverages advanced computational power and large-scale datasets to identify statistical regions of interest (sROIs or statROIs) – brain areas where structural or functional properties are most strongly associated with specific cognitive functions or behavioral outcomes [1]. The core objective is to move beyond simplistic, lesion-based models toward a more complete, multivariate accounting of the complex brain substrates underlying human cognition.

This transition addresses critical limitations of earlier approaches. Theory-driven or lesion-driven studies, while valuable, often missed subtler yet significant effects distributed across brain networks [1]. Furthermore, approaches relying on predefined anatomical atlas regions assume that brain-behavior associations conform to these artificial boundaries, which may not reflect the true, distributed nature of neural coding [1]. The modern signature approach overcomes these constraints by using data-driven feature selection to identify optimal brain patterns associated with cognition without prior anatomical constraints, promising a more genuine and comprehensive understanding of the neural architecture of thought.

Theoretical Evolution: From Lesions to Large-Scale Data

The journey to contemporary brain signature research began with foundational insights from lesion studies, which established causal links between specific brain areas and cognitive deficits. While these studies identified key regions, they provided an incomplete picture, often overlooking the distributed network dynamics essential for complex cognitive functions. The advent of neuroimaging enabled non-invasive measurement of brain structure and function across the entire brain, setting the stage for more exploratory research.

Initially, neuroimaging studies remained largely theory-driven, testing hypotheses about predefined regions of interest (ROIs). However, the development of high-quality brain parcellation atlases enabled a more systematic survey of brain-behavior associations across many regions [1]. A significant conceptual advance was the Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT), which provided a theoretical framework for the predominant involvement of fronto-parietal regions in supporting complex cognition [2]. Despite these advances, atlas-based approaches still constrained analyses within predetermined anatomical boundaries.

The modern signature approach represents the next evolutionary step, employing fully data-driven feature selection at a fine-grained (e.g., voxel) level [1]. This methodology does not require predefined ROIs and can capture complex, distributed patterns that cross traditional anatomical boundaries. The exponential growth of large-scale, open-access neuroimaging datasets (e.g., UK Biobank, ADNI) has been instrumental in this shift, providing the necessary statistical power for robust, replicable discoveries [1] [2].

Methodological Foundations: Computing Robust Brain Signatures

Core Computational Frameworks

The computational foundation of brain signature research involves sophisticated analytical pipelines that identify multivariate brain patterns predictive of cognitive phenotypes. Several methodological approaches have emerged:

- Voxel-Based Regression: Directly computes associations between brain measures (e.g., gray matter thickness) and behavioral outcomes at each voxel, creating a whole-brain significance map without anatomical constraints [1].

- Machine Learning Algorithms: Include support vector machines, support vector classification, relevant vector regression, and convolutional neural networks that can identify complex, non-linear relationships between brain features and cognition [1].

- Consensus Mask Approach: Derives signatures by aggregating results across multiple random discovery subsets to enhance robustness and replicability [1].

A critical validation study implemented a rigorous approach to signature development, deriving regional gray matter thickness associations for memory domains in 40 randomly selected discovery subsets of size 400 across two cohorts (UCD and ADNI3) [1]. Spatial overlap frequency maps were generated, with high-frequency regions defined as "consensus" signature masks, which were then validated in separate datasets (UCD and ADNI1) [1]. This method demonstrated both spatial convergence and model fit replicability, addressing key validation requirements for robust signature development.

Experimental Protocol for Signature Development and Validation

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive methodology for developing and validating brain signatures:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Acquire T1-weighted structural MRI scans using standardized protocols [1].

- Process images through automated pipelines: brain extraction using convolutional neural net recognition of intracranial cavity with human quality control [1].

- Perform affine and B-spline registration to a structural template [1].

- Conduct native-space tissue segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and CSF [1].

Discovery Phase:

- Randomly select multiple discovery subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of n=400) from the discovery cohort [1].

- For each subset, compute voxel-wise associations between gray matter thickness and cognitive outcomes [1].

- Generate spatial overlap frequency maps across all discovery subsets [1].

- Define high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks for each cognitive domain [1].

Validation and Replicability Assessment:

- Apply consensus signatures to independent validation cohorts [1].

- Evaluate signature replicability through correlation of model fits across multiple random validation subsets [1].

- Compare explanatory power of signature models against theory-based models in full validation cohorts [1].

- Assess spatial consistency of signature regions across independent discovery cohorts [1].

Table 1: Essential Resources for Brain Signature Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Cohorts | UK Biobank (N=500,000), ADNI, Generation Scotland, LBC1936 [2] | Provide large-scale discovery and validation datasets with cognitive and imaging data |

| Cognitive Assessments | SENAS, ADNI-Mem, Everyday Cognition (ECog) scales [1] | Measure specific cognitive domains (episodic memory, everyday function) with high sensitivity |

| Image Processing Tools | FreeSurfer, FSL, SPM, in-house pipelines [1] [2] | Perform cortical surface reconstruction, tissue segmentation, and spatial normalization |

| Statistical Platforms | R, Python, MATLAB with specialized neuroimaging toolboxes | Implement voxel-wise analyses, machine learning, and statistical validation |

| Brain Atlases | Desikan-Killiany, Glasser, AAL | Provide anatomical reference frameworks for regional analyses |

Key Research Findings and Quantitative Comparisons

Large-Scale Brain-Cognition Associations

Recent mega-analyses have quantified brain-cognition relationships with unprecedented precision. A 2025 study meta-analyzed vertex-wise general cognitive functioning (g) and cortical morphometry associations across 38,379 participants from three cohorts (UK Biobank, Generation Scotland, Lothian Birth Cohort 1936) [2]. The study revealed that g-morphometry associations vary substantially across the cortex (β range = -0.12 to 0.17 across morphometry measures) and show good cross-cohort agreement (mean spatial correlation r = 0.57, SD = 0.18) [2].

This research identified four major dimensions of cortical organization that explain 66.1% of the variance across 33 neurobiological characteristics (including neurotransmitter receptor densities, gene expression, functional connectivity, metabolism, and cytoarchitectural similarity) [2]. These dimensions showed significant spatial patterning with g-morphometry profiles (p_spin < 0.05 |r| range = 0.22 to 0.55), providing insights into the neurobiological principles underlying cognitive individual differences [2].

Validation Studies and Comparative Performance

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Signature vs. Theory-Based Models

| Model Type | Discovery Cohort | Validation Cohort | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory Signature | UCD (n=578), ADNI3 (n=831) | UCD (n=348), ADNI1 (n=435) | Outperformed theory-based models; high replicability (r > .85 in random subsets) | [1] |

| Everyday Memory Signature | UCD (n=578), ADNI3 (n=831) | UCD (n=348), ADNI1 (n=435) | Similar performance to neuropsychological memory signatures; strongly shared brain substrates | [1] |

| General Cognition (g) Maps | UKB, GenScot, LBC1936 (N=38,379) | Cross-cohort replication | Moderate to strong spatial consistency (mean r=0.57); association with neurobiological gradients | [2] |

| Education Quality Effects | 20 countries (n=7,533) | Cross-national comparison | Education quality had 1.3-7.0x stronger effect on brain measures than years of education | [3] |

A critical validation study demonstrated that consensus signature model fits were highly correlated in 50 random subsets of each validation cohort, indicating high replicability [1]. In full cohort comparisons, signature models consistently outperformed other commonly used measures [1]. Notably, signatures derived for two memory domains (neuropsychological and everyday cognition) suggested strongly shared brain substrates, indicating both domain-specific and generalizable neural correlates [1].

Neurobiological Interpretation and Multimodal Integration

The interpretation of brain signatures has been enhanced through spatial correlation with neurobiological profiles. A 2025 study created a compendium of cortex-wide and within-region spatial correlations among general and specific facets of brain cortical organization and higher-order cognitive functioning [2]. This approach enables direct quantitative inferences about the organizing principles underlying cognitive-MRI signals, moving beyond descriptive interpretations.

The integration of multiple neurobiological modalities reveals four major dimensions of cortical organization:

- Molecular-Genetic Gradients: Spatial patterns of neurotransmitter receptor densities and gene expression profiles.

- Microstructural Architecture: Cytoarchitectural similarity and cellular composition patterns.

- Functional Network Organization: Intrinsic connectivity and network topology measures.

- Metabolic Profiles: Regional variations in energy metabolism and hemodynamic coupling.

These dimensions provide a neurobiological framework for interpreting why certain brain regions consistently emerge in cognitive signatures, linking macroscopic associations to their underlying cellular, molecular, and systems-level determinants.

Future Directions and Clinical Applications

Emerging Methodological Innovations

The future of brain signature research involves several promising directions:

- Multimodal Integration: Combining structural, functional, metabolic, and genetic information for more comprehensive signatures [2].

- Dynamic Signatures: Capturing temporal changes in brain-behavior relationships across the lifespan and in disease progression.

- Causal Inference: Integrating interventional approaches (TMS, tDCS, pharmacological challenges) to establish causal links between signature regions and cognitive outcomes.

- Advanced Computational Methods: Deep learning architectures that can identify complex, non-linear brain-behavior relationships while maintaining interpretability [1].

Clinical Translation and Precision Medicine

Brain signatures hold significant promise for clinical applications:

- Early Detection: Identifying individuals at risk for cognitive decline based on deviation from healthy brain patterns [3].

- Differential Diagnosis: Distinguishing between neurodegenerative conditions with overlapping symptoms [3].

- Treatment Targeting: Guiding neuromodulation interventions by identifying optimal targets based on individual brain architecture.

- Treatment Response Prediction: Forecasting individual response to cognitive interventions or pharmacological treatments based on baseline brain signatures.

The 2025 study on educational disparities demonstrated that education quality has a substantially stronger influence (1.3 to 7.0 times) on brain health metrics than simply years of education, with robust effects persisting despite variations in income and socioeconomic factors [3]. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating qualitative measures alongside quantitative metrics in brain signature research.

The evolution from theory-driven to data-driven explorations has fundamentally transformed our approach to understanding brain-behavior relationships. Brain signatures represent a powerful framework for identifying robust, replicable neural patterns associated with cognitive functions, with rigorous validation approaches addressing previous limitations in reproducibility. The integration of large-scale datasets, advanced computational methods, and multimodal neurobiological data has positioned the field to make transformative discoveries about the neural architecture of human cognition. As these methods continue to mature, brain signatures promise to bridge the gap between basic cognitive neuroscience and clinical applications, enabling more precise diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention for neurological and psychiatric conditions.

The pursuit of robust neural correlates of human cognition represents a fundamental challenge in neuroscience, particularly for developing biomarkers for psychiatric and neurological disorders. The "brain signatures of cognition" concept refers to the identification of reproducible neurobiological patterns—whether structural, functional, or neurochemical—that underlie core cognitive processes and can be reliably measured across populations. Large-scale meta-analyses have emerged as a powerful methodology to overcome the limitations of individual neuroimaging studies, which often suffer from small sample sizes, methodological heterogeneity, and low statistical power. By quantitatively synthesizing data from tens of thousands of individuals, these approaches can distinguish consistent neural signatures from noise, providing a more definitive mapping between brain organization and cognitive function. This whitepaper examines convergent evidence from recent large-scale meta-analyses that collectively analyze data from 38,379 individuals [2], outlining the core findings, methodological frameworks, and practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals. These findings establish a foundational framework for understanding the neurobiological architecture of human cognition and its perturbations in clinical populations.

Core Quantitative Findings from Large-Scale Meta-Analyses

Recent large-scale investigations have yielded comprehensive maps of the relationship between brain structure and general cognitive functioning (g). The following tables summarize the key quantitative findings from a vertex-wise meta-analysis of cortical morphometry and its association with cognitive performance.

Table 1: Cohort Characteristics and Meta-Analytic Sample [2]

| Cohort Name | Sample Size (N) | Age Range (Years) | Female (%) | Primary Morphometry Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank (UKB) | 36,744 | 44 - 83 | 53% | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth |

| Generation Scotland (GenScot) | 1,013 | 26 - 84 | 60% | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth |

| Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (LBC1936) | 622 | ~70 | - | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth |

| Meta-Analytic Total | 38,379 | 26 - 84 | ~54% | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth |

Table 2: Summary of g-Morphometry Associations Across the Cortex [2]

| Morphometry Measure | Range of Standardized Association (β) with g | Key Cortical Regions Involved | Notes on Association Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Volume | -0.12 to 0.17 | Frontal, Parietal, Temporal | Positive in most association cortices |

| Surface Area | -0.12 to 0.17 | Frontal, Parietal | Generally positive correlations |

| Cortical Thickness | -0.12 to 0.17 | Prefrontal, Anterior Cingulate | Positive and negative associations observed |

| Curvature | -0.12 to 0.17 | Frontal, Insular | Complex regional patterning |

| Sulcal Depth | -0.12 to 0.17 | Parieto-occipital, Frontal | Complex regional patterning |

The associations between g and cortical morphometry demonstrate significant regional variation across the cortex, with effects varying in both magnitude and direction depending on the specific morphometric measure and brain region. The strongest and most consistent positive associations are observed within the fronto-parietal network, a finding that aligns with the established Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) of intelligence [4] [2]. This large-scale analysis provides unprecedented precision in mapping these relationships, confirming that brain-cognition associations are not uniform but are instead patterned according to underlying neurobiological principles.

Table 3: Convergent Functional Alterations in Clinical Populations from Meta-Analyses

| Clinical Population | Convergent Brain Regions with Functional Alterations | Task Paradigm / State | Number of Experiments/Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar Disorder (BD) [5] | Left Amygdala, Left Medial Orbitofrontal Cortex, Left Superior & Right Inferior Parietal Lobules, Right Posterior Cingulate Cortex | Emotional, Cognitive, and Resting-State | 506 experiments; 5,745 BD & 8,023 control participants |

| Escalated Aggression [6] | Amygdala, lOFC, dmPFC, MTG, ACC, Anterior Insula | Multi-Paradigm (Functional & Structural) | 325 experiments; 16,529 subjects |

The functional meta-analysis of Bipolar Disorder reveals condition-dependent neural signatures, with emotional processing differences localized to the left amygdala, cognitive task differences in parietal lobules and medial orbitofrontal cortex, and resting-state differences in the posterior cingulate cortex [5]. This underscores the importance of context in identifying neural biomarkers.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Framework

Large-Scale Morphometry Meta-Analysis Protocol

The protocol for the large-scale g-morphometry analysis represents a state-of-the-art approach for integrating multi-cohort data.

Cohort and Data Aggregation:

- Individual-level data were harmonized from three large independent cohorts: UK Biobank, Generation Scotland, and the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 [2].

- General cognitive functioning (

g) was derived as a latent factor from multiple cognitive tests per cohort, capturing variance common across cognitive domains. - Cortical morphometry was processed using FreeSurfer, yielding five vertex-wise measures: cortical volume, surface area, thickness, curvature, and sulcal depth.

Vertex-Wise Association Mapping:

- Within each cohort, linear models were run at each of the approximately 299,790 cortical vertices for each morphometry measure, predicting

gwhile controlling for age and sex [2]. - The model was:

Morphometry ~ g + Age + Sex, generating a standardized beta (β) coefficient and statistical significance map for each vertex.

- Within each cohort, linear models were run at each of the approximately 299,790 cortical vertices for each morphometry measure, predicting

Meta-Analysis Integration:

- The vertex-wise association results (β estimates) from the three cohorts were then synthesized using a random-effects meta-analysis [2].

- This produced a single, comprehensive set of meta-analytic maps (one per morphometry measure) indicating the consistent association between brain structure and

gacross a total of 38,379 individuals.

Neurobiological Decoding:

- To interpret the

g-morphometry maps, their spatial patterning was tested for correlation with 33 open-source cortical maps of neurobiological properties, including:- Neurotransmitter receptor densities (e.g., serotonin, dopamine, GABA)

- Gene expression profiles from the Allen Human Brain Atlas

- Functional connectivity gradients

- Metabolic profiles and cytoarchitectural similarity [2]

- Spatial correlations were computed both cortex-wide and within specific anatomical regions to decode the biological meaning of the brain-cognition associations.

- To interpret the

Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) Meta-Analysis Protocol for Functional Studies

For synthesizing functional neuroimaging studies across different tasks and clinical groups, a coordinate-based meta-analysis approach is employed.

Systematic Literature Search:

- A comprehensive search of databases (e.g., PubMed) is conducted using predefined search terms related to the population (e.g., Bipolar Disorder) and imaging modality (fMRI, PET) [5].

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria are strictly applied, typically including: whole-brain voxelwise results in standard space, comparison of a clinical group vs. controls, and adult participants.

Data Extraction:

- Coordinates of significant activation or functional connectivity differences between groups (e.g., BD vs. controls) are extracted from each included study [5].

- Experiments are often categorized by paradigm type (e.g., emotional, cognitive, resting-state) for separate and pooled analyses.

Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE):

- The ALE algorithm models each reported focus as the center of a 3D Gaussian probability distribution, accounting for spatial uncertainty [5].

- Voxel-wise ALE scores are computed, representing the convergence of probabilities across all experiments.

- Statistical Significance is determined using cluster-level family-wise error (FWE) correction, comparing the observed ALE values against a null distribution of random spatial convergence [5]. This is a conservative threshold that minimizes false positives.

Conjunction and Contrast Analyses:

- To identify condition-independent signatures, convergence across all experiment types is tested.

- To identify condition-dependent signatures, separate ALE analyses are run for each paradigm type (e.g., emotional tasks only) [5].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the two primary meta-analytic pathways discussed above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Brain Signature Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer Software Suite | Automated cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation of structural MRI data. | Used to generate vertex-wise maps of cortical volume, surface area, thickness, curvature, and sulcal depth [2]. |

| Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) | Coordinate-based meta-analysis algorithm for identifying convergent brain activation across studies. | Implemented in platforms like GingerALE; used to synthesize functional neuroimaging foci [5]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Processing large-scale neuroimaging datasets and running computationally intensive vertex-wise analyses. | Essential for handling data from tens of thousands of participants and millions of data points [2]. |

| Standard Stereotaxic Spaces (MNI/Talairach) | Common coordinate systems for spatial normalization of neuroimaging data. | Allows for pooling and comparison of data across different studies and scanners [5]. |

| Allen Human Brain Atlas | Provides comprehensive data on gene expression patterns in the human brain. | Used for neurobiological decoding to relate morphometry maps to underlying genetic architecture [2]. |

| Neurotransmitter Receptor Atlases | Maps of density and distribution for various neurotransmitter systems (e.g., serotonin, dopamine). | Used to test spatial correlations between cognitive signatures and neurochemical organization [2]. |

| UK Biobank Neuroimaging Data | A large-scale, open-access database of structural and functional MRI, genetics, and health data. | Serves as a primary cohort for discovery and replication in large-scale studies [2]. |

Visualizing the Neurobiological Dimensions of Cognition

The integration of neurobiological maps reveals the fundamental organizational principles of the cortex that relate to cognitive functioning. The following diagram illustrates the four major dimensions derived from the 33 neurobiological profiles and their relationship with the g-morphometry associations.

These four major dimensions of cortical organization, which collectively explain 66.1% of the variance across the 33 neurobiological properties, show significant spatial correlation with the patterns of g-morphometry associations [2]. This indicates that the brain's fundamental neurobiological architecture—spanning molecular, microstructural, and functional levels—shapes the structural correlates of higher-order cognitive functioning. This integrative approach moves beyond mere description to provide a mechanistic framework for understanding individual differences in cognition.

Large-scale meta-analyses provide the statistical power and robustness necessary to identify reproducible neural signatures of cognition and its disorders. The convergent evidence from nearly 40,000 individuals solidifies the role of fronto-parietal networks in general cognitive functioning and reveals distinct, condition-dependent functional alterations in clinical populations like Bipolar Disorder. The integration of meta-analytic findings with multidimensional neurobiological maps represents a significant advance, decoding the underlying biological principles that give rise to the observed brain-cognition relationships. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings provide a validated set of target networks and regions for therapeutic intervention. The methodological frameworks and tools outlined here offer a blueprint for future research aimed at identifying clinically translatable biomarkers for cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric and neurological diseases, ultimately guiding diagnosis, treatment selection, and the development of novel therapeutics.

The quest to understand the biological foundations of human cognition represents a central challenge in modern neuroscience. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on three fundamental neurobiological correlates—cortical morphometry, neurotransmitter system organization, and gene expression architecture—and their collective relationship to cognitive functioning. By integrating findings from large-scale neuroimaging studies, molecular analyses, and genetic investigations, we provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how multi-scale brain properties give rise to individual differences in cognitive abilities, particularly general cognitive functioning (g). This synthesis aims to inform future research directions and therapeutic development by elucidating the core neurobiological signatures that underlie human cognition.

Cortical Morphometry and Cognitive Functioning

Cortical morphometry examines the structural characteristics of the cerebral cortex, including thickness, surface area, volume, curvature, and sulcal depth. These macroscopic measures reflect underlying microarchitectural properties and developmental processes that support cognitive functions.

Large-Scale Mapping of g-Cortical Morphometry Associations

Recent meta-analyses comprising 38,379 participants from three cohorts (UK Biobank, Generation Scotland, and Lothian Birth Cohort 1936) have provided robust mapping of associations between general cognitive functioning and multiple cortical morphometry measures across 298,790 cortical vertices [2]. The findings demonstrate that:

- g-morphometry associations vary substantially across the cortex in both magnitude and direction (β range = -0.12 to 0.17 across morphometry measures)

- Cross-cohort consistency is observed with mean spatial correlation r = 0.57 (SD = 0.18)

- Regional specificity exists in how different morphometric measures relate to cognitive function, suggesting distinct biological underpinnings

Table 1: Effect Size Ranges for g-Morphometry Associations Across the Cortex

| Morphometry Measure | β Range | Primary Cortical Patterns |

|---|---|---|

| Cortical Volume | -0.12 to 0.17 | Regional specificity with strongest associations in parieto-frontal regions |

| Surface Area | -0.10 to 0.15 | Distributed associations across association cortices |

| Cortical Thickness | -0.09 to 0.13 | More spatially restricted pattern than surface area |

| Curvature | -0.08 to 0.11 | Regional specificity in temporal and frontal regions |

| Sulcal Depth | -0.07 to 0.10 | Association with major sulcal patterns |

Methodological Considerations and Challenges

The relationship between cortical morphometry and intelligence requires careful methodological consideration [7]. Key challenges include:

- Multicollinearity among independent variables in multivariate regression models

- Complex relationship with total brain volume, which is itself associated with intelligence (r ≈ 0.19-0.60)

- Limited predictive utility of cortical thickness and peri-cortical contrast beyond brain volume alone across multiple datasets (ABCD, NIHPD, NKI-RS)

These findings suggest that cortical morphometry-cognition relationships must be interpreted within the context of overall brain architecture and that methodological approaches must account for the interdependency of morphometric measures.

Neurotransmitter Systems and Brain Organization

Neurotransmitter receptors and transporters are heterogeneously distributed across the neocortex and fundamentally shape brain communication, plasticity, and functional specialization.

Comprehensive Mapping of Neurotransmitter Systems

A whole-brain three-dimensional normative atlas of 19 receptors and transporters across nine neurotransmitter systems has been constructed from positron emission tomography (PET) data from more than 1,200 healthy individuals [8]. This resource provides unprecedented insight into the chemoarchitectural organization of the human brain:

Table 2: Key Neurotransmitter Systems Mapped in the Human Neocortex

| Neurotransmitter System | Receptors/Transporters | Primary Cortical Gradients |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | D1, D2, DAT | Frontal to posterior gradient |

| Serotonin | 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, 5-HT4, 5-HT6, SERT | High density in limbic and paralimbic regions |

| Glutamate | NMDA, AMPA, mGluR5 | Widespread with regional variations |

| GABA | GABAA, GABAB | Complementary to glutamate distribution |

| Acetylcholine | α4β2, M1 | Higher in sensory and limbic regions |

| Norepinephrine | NET | Diffuse with frontal predominance |

| Cannabinoid | CB1 | Limbic and association areas |

| Opioid | MOR, DOR, KOR | Limbic system and pain processing regions |

| Histamine | H3 | Thalamocortical and basal forebrain targets |

Receptor Architecture and Large-Scale Brain Organization

The distribution of neurotransmitter receptors follows fundamental principles of brain organization [8] [9]:

- Receptor similarity decreases exponentially with Euclidean distance, supporting proximity-based microarchitectural organization

- Anatomically connected areas show greater receptor similarity, suggesting coordinated modulation

- Regions within intrinsic networks share similar receptor profiles according to the Yeo-Krienen seven-network classification

- Receptor similarity correlates with functional connectivity (r = 0.23 after regressing Euclidean distance)

- Receptor distributions augment structure-function coupling, particularly in unimodal areas and the paracentral lobule

Neurotransmitter Systems Shape Oscillatory Dynamics and Network Centrality

The local receptor microarchitecture fundamentally constrains large-scale brain dynamics [9]:

- Network centrality in delta and gamma frequencies covaries positively with GABAA, NMDA, dopaminergic, and most serotonergic receptor/transporter densities

- Alpha and beta band networks show negative covariance with the same receptor systems

- Spectrally specific patterning demonstrates that neurotransmitter systems shape frequency-specific communication in resting-state networks

Diagram 1: Neurotransmitter Systems Shape Multi-Scale Brain Organization

Gene Expression Architecture of the Cortex

The spatial patterning of gene expression across the cerebral cortex denotes specialized molecular support for particular brain functions and represents a fundamental link between genetics and brain organization.

Major Components of Cortical Gene Expression

Advanced analysis of the Allen Human Brain Atlas has revealed three major components of cortical gene expression that represent fundamental transcriptional programs [10]:

- C1 (First Component): Accounts for 38% of variance, represents a sensorimotor-association (S-A) axis, enriched for general neuronal processes

- C2 (Second Component): Accounts for 10% of variance, separates metabolic from epigenetic processes

- C3 (Third Component): Accounts for 6.5% of variance, distinguishes synaptic plasticity/learning from immune-related processes

These components demonstrate high generalizability (gC1 = 0.97, gC2 = 0.72, gC3 = 0.65) and reproducibility in independent datasets (PsychENCODE regional correlations: rC1 = 0.85, rC2 = 0.75, rC3 = 0.73) [10].

Gene Expression and Cognitive Functioning

Principal component analysis of 8,235 genes across 68 cortical regions reveals that region-to-region variation in cortical expression profiles covaries across two major dimensions [11]:

- Spatial covariation in gene expression accounts for 49.4% of variance across regions

- Two major dimensions are characterized by downregulation and upregulation of cell-signaling/modification and transcription factors

- Brain regions more strongly implicated in g show balanced expression between these major components

- 41 candidate genes identified as cortical spatial correlates of g beyond the major components (|β| range = 0.15 to 0.53)

Table 3: Gene Categories Associated with Cortical Organization and Cognitive Functioning

| Gene Category | Representative Genes | Primary Cortical Associations | Functional Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interneuron Markers | SST, PVALB, VIP, CCK | C1 component (sensorimotor-association axis) | GABAergic signaling, cortical inhibition |

| Glutamatergic Genes | GRIN, GABRA | C1 component with opposite weighting | excitatory neurotransmission |

| Metabolic Genes | Various oxidative phosphorylation | C2 positive weighting | mitochondrial function, energy metabolism |

| Epigenetic Regulators | Chromatin modifiers | C2 negative weighting | transcriptional regulation, DNA modification |

| Synaptic Plasticity | ARC, FOS, NPAS4 | C3 positive weighting | learning, memory formation, synaptic scaling |

| Immune-related Genes | Complement factors, cytokines | C3 negative weighting | neuroinflammation, microglial function |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Large-Scale Morphometry-cognition Mapping

Objective: To identify brain regions where cortical morphometry is associated with general cognitive function [2]

Sample Characteristics:

- Meta-analytic N = 38,379 (age range = 44-84 years)

- Multi-cohort design: UK Biobank, Generation Scotland, Lothian Birth Cohort 1936

- Comprehensive exclusion criteria for neurological conditions

MRI Acquisition and Processing:

- T1-weighted structural imaging across multiple sites

- FreeSurfer processing pipeline for cortical reconstruction

- Vertex-wise analysis of 5 morphometry measures: volume, surface area, thickness, curvature, sulcal depth

- Quality control: exclusion based on FreeSurfer qcaching success

Cognitive Assessment:

- Multi-domain cognitive test batteries

- Derivation of general cognitive factor (g) using principal component analysis or latent variable modeling

- Covariate adjustment for age, sex, and relevant demographic variables

Statistical Analysis:

- Cohort-specific vertex-wise general linear models

- Random-effects meta-analysis across cohorts

- Multiple comparison correction using family-wise error rate or false discovery rate

- Spatial correlation analysis for cross-cohort consistency

Protocol 2: Neurotransmitter Receptor Mapping

Objective: To construct a comprehensive atlas of neurotransmitter receptor distributions and relate them to brain structure and function [8]

PET Data Collection:

- 19 different neurotransmitter receptors/transporters across 9 systems

- 1,238 healthy participants total

- Multiple tracers for comprehensive coverage

- Standardized acquisition protocols across sites

Data Processing:

- Parcellation into 100 cortical regions using harmonized atlas

- Z-scoring within each tracer map for comparability

- Construction of receptor similarity matrix between brain regions

- Spatial correlation with structural and functional connectivity measures

Validation:

- Comparison with independent autoradiography dataset

- Robustness checks across different parcellation schemes

- Sensitivity analyses for individual receptor contributions

Protocol 3: Cortical Gene Expression Analysis

Objective: To identify major dimensions of cortical gene expression and their relationship to neurodevelopment and cognition [10]

Data Sources:

- Allen Human Brain Atlas (6 donors, 5 male, 1 female, age 24-57)

- PsychENCODE replication dataset (54 healthy controls, 11 regions)

- Quality control filtering for spatially consistent genes

Dimension Reduction:

- Application of diffusion map embedding (DME) to filtered expression matrix

- Generalizability assessment across donor brains

- Comparison with principal component analysis (PCA)

Functional Annotation:

- Gene Ontology enrichment analysis (FDR 5%)

- Cell-type specificity using marker genes

- Cortical layer enrichment patterns

Triangulation with Neuroimaging:

- Spatial correlation with cortical thickness, T1w/T2w, and functional gradients

- Association with neurodevelopmental disorder genetic risk

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Neurobiological Correlates Research

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Key Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Data | UK Biobank Neuroimaging | Large-scale morphometry-cognition mapping | Application required |

| Molecular Atlases | Allen Human Brain Atlas | Cortical gene expression patterns | Publicly available |

| Neurotransmitter Maps | PET Receptor Atlas (Hansen et al.) | Receptor density-function relationships | https://github.com/netneurolab/hansen_receptors |

| Analysis Pipelines | FreeSurfer | Cortical surface reconstruction and morphometry | Publicly available |

| Morphometry Networks | MIND (Morphometric Inverse Divergence) | Person-specific structural networks | Published methods [12] |

| Genetic Data | PsychENCODE | Developmental transcriptomics | Controlled access |

| Cognitive Data | Multiple cohort cognitive batteries | General cognitive factor derivation | Varies by cohort |

Integrated Signaling Pathways and Biological Workflows

Diagram 2: Multi-Scale Integration from Genes to Cognition

The relationship between neurotransmitter systems, gene expression, and cortical morphometry follows an integrated pathway from molecular organization to cognitive function:

- Genetic variation influences regional gene expression patterns across the cortex

- Spatial gene expression gradients determine neurotransmitter receptor and transporter distributions

- Receptor distributions shape microstructural organization and cell-type distributions

- Microstructural properties influence macroscopic cortical morphometry and connectivity patterns

- Morphometric networks support large-scale functional dynamics that implement cognitive processes

- Individual differences in these multi-level properties give rise to variations in cognitive ability and clinical phenotypes

This integrated framework highlights the importance of studying neurobiological correlates across spatial and temporal scales, from molecular architecture to system-level organization, to fully understand the biological basis of human cognition.

The integration of cortical morphometry, neurotransmitter system organization, and gene expression architecture provides a powerful multi-scale framework for understanding the neurobiological correlates of human cognition. Large-scale mapping efforts have revealed consistent spatial patterns linking brain structure, molecular organization, and cognitive function. The developing toolkit of open resources, standardized protocols, and analytical frameworks promises to accelerate discovery in this field, with important implications for understanding cognitive individual differences, neurodevelopmental disorders, and personalized therapeutic approaches. Future research should focus on longitudinal designs, cross-species validation, and integration across omics technologies to further elucidate the causal pathways linking molecular organization to cognitive function.

The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) and Modern Expansions

The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) represents a foundational framework for understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of human intelligence. First comprehensively proposed by Jung and Haier in 2007, this theory identifies a distributed network of brain regions that collectively support intelligent behavior and reasoning capabilities [13] [14]. The P-FIT model emerged from a systematic review of 37 neuroimaging studies encompassing 1,557 participants, synthesizing evidence from multiple imaging modalities including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and voxel-based morphometry (VBM) [13] [14]. A 2010 review of the neuroscience of intelligence described P-FIT as "the best available answer to the question of where in the brain intelligence resides" [13], affirming its significance in the field of cognitive neuroscience. The theory situates itself within the broader research on brain signatures of cognition by proposing that individual differences in cognitive performance arise from variations in the structure and function of this specific network, rather than from domain-specific modules or general brain properties [13].

Core Principles of the P-FIT Model

The P-FIT conceptualizes intelligence as emerging from how effectively different brain regions integrate information to form intelligent behaviors [13]. The theory proposes that intelligence relies on large-scale brain networks connecting specific regions within the frontal, parietal, temporal, and cingulate cortices [13]. These regions, which show significant overlap with the task-positive network, facilitate efficient communication and information exchange throughout the brain [13].

The model outlines a sequential information processing pathway essential for intelligent behavior, incorporating four key stages: (1) sensory processing primarily in visual and auditory modalities within temporal and parietal areas; (2) sensory abstraction and elaboration by the parietal cortex, particularly the supramarginal, superior parietal, and angular gyri; (3) interaction between parietal and frontal regions for hypothesis testing and evaluating potential solutions; and (4) response selection and inhibition of competing responses mediated by the anterior cingulate cortex [13]. According to this framework, greater general intelligence in individuals results from enhanced communication efficiency between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe, anterior cingulate cortex, and specific temporal and parietal cortex regions [13].

Table 1: Core Brain Regions in the P-FIT Network and Their Functional Contributions

| Brain Region | Brodmann Areas | Functional Role in Intelligence |

|---|---|---|

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | 6, 9, 10, 45, 46, 47 | Executive control, working memory, problem-solving, hypothesis testing |

| Inferior Parietal Lobule | 39, 40 | Sensory abstraction, semantic processing, symbolic representation |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | 7 | Visuospatial processing, sensory integration |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | 32 | Response selection, error detection, inhibition of competing responses |

| Temporal Regions | 21, 37 | Visual and auditory processing, semantic memory |

| Occipital Regions | 18, 19 | Visual processing and imagery |

| White Matter Tracts | Arcuate Fasciculus | Information transfer between temporal, parietal, and frontal regions |

Neuroimaging Evidence Supporting P-FIT

Structural Imaging Evidence

Across structural neuroimaging studies reviewed by Jung and Haier (2007), full-scale IQ scores from the Wechsler Intelligence scales correlated with frontal and parietal regions in more than 40% of 11 studies analyzed [13]. More than 30% of studies using full-scale IQ measures found correlations with the left cingulate as well as both left and right frontal regions [13]. Interestingly, no structural correlations were observed between temporal or occipital lobes and intelligence scales, which the authors attributed to the task-dependent nature of relationships between intellectual performance and these regions [13].

Further evidence came from Haier et al. (2009), who investigated correlations between psychometric g and gray matter volume, aiming to determine whether a consistent "neuro-g" substrate exists [13]. Using data from 6,292 participants on eight cognitive tests to derive g factors, with a subset of 40 participants undergoing voxel-based morphometry, they found that neural correlates of g depended partly on the specific test used to derive g, despite evidence that g factors from different tests tap the same underlying psychometric construct [13]. This methodological insight helps explain variance in neuroimaging findings across studies. In the same year, Colom and colleagues measured gray matter correlates of g in 100 healthy Spanish adults, finding general support for P-FIT while noting some inconsistencies, including voxel clusters in frontal eye fields and inferior/middle temporal gyrus involved in planning complex movements and high-level visual processing, respectively [13].

Functional Imaging Evidence

Across functional neuroimaging studies, Jung and Haier reported that more than 40% of studies found correlations between bilateral activations in frontal and occipital cortices and intelligence, with left hemisphere activation typically significantly higher than right [13]. Similarly, bilateral cortical areas in the occipital lobe, particularly BA 19, were activated during reasoning tasks in more than 40% of studies, again with greater left-side activation [13]. The parietal lobe was consistently involved in reasoning tasks, with BA 7 activated in more than 70% of studies and BA 40 activation observed in more than 60% of studies [13].

Vakhtin et al. (2014) specifically investigated functional networks related to fluid intelligence as measured by Raven's Progressive Matrices tests [13]. Using fMRI on 79 American university students across three sessions (resting state, standard Raven's, and advanced Raven's), they identified a discrete set of networks associated with fluid reasoning, including the dorsolateral cortex, inferior and parietal lobule, anterior cingulate, and temporal and occipital regions [13]. The activated networks included attentional, cognitive, sensorimotor, visual, and default-mode networks during the reasoning task, providing what the authors described as evidence "broadly consistent" with the P-FIT theory [13].

Table 2: Key Neuroimaging Studies Supporting P-FIT

| Study | Participants | Methods | Key Findings Supporting P-FIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jung & Haier (2007) [13] [14] | 1,557 (across 37 studies) | Multimodal review | Identified consistent network of frontal, parietal, temporal, and cingulate regions |

| Haier et al. (2009) [13] | 6,292 (40 scanned) | Voxel-based morphometry | Gray matter correlates of g partly test-dependent, explaining variance across studies |

| Colom et al. (2009) [13] | 100 Spanish adults | Structural MRI | General P-FIT support with additional frontal eye field and temporal involvement |

| Vakhtin et al. (2014) [13] | 79 university students | fMRI (resting state + Raven's Matrices) | Discrete networks for fluid reasoning including DLPFC, parietal, ACC, temporal regions |

| Gläscher et al. (2010) [13] | 182 lesion patients | Voxel-based lesion symptom mapping | Left hemisphere lesions primarily affected g; only BA 10 in left frontal pole unique to g |

Evidence from Lesion Studies

Lesion studies provide critical causal evidence for the P-FIT model by demonstrating how specific brain injuries impact cognitive performance. The majority of studies providing lesion evidence use voxel-based lesion symptom mapping, a method that compares intelligence test scores between participants with and without lesions at each voxel, enabling identification of regions with causal roles in test performance [13].

Gläscher et al. (2010) explored whether g has distinct neural substrates or relates to global neural properties like total brain volume [13]. Using voxel-based lesion symptom mapping, they found significant relationships between g scores and regions primarily in the left hemisphere, including major white matter tracts in temporal, parietal, and inferior frontal areas [13]. Only one brain area was unique to g—Brodmann Area 10 in the left frontal pole—while remaining areas activated by g were shared with subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) [13].

A study of 182 male veterans from the Phase 3 Vietnam Head Injury Study registry provided additional causal evidence [13]. Barbey, Colom, Solomon, Krueger, and Forbes (2012) used voxel-based lesion symptom mapping to identify regions interfering with performance on the WAIS and the Delis-Kaplan executive function system [13]. Their findings indicated that g shared neural substrates with several WAIS subtests, including Verbal Comprehension, Working Memory, Perceptual Organization, and Processing Speed [13]. The implicated areas are known to be involved in language processing, working memory, spatial processing, and motor processing, along with major white matter tracts including the arcuate fasciculus connecting temporal, parietal, and inferior frontal regions [13]. Frontal and parietal lobes were found critical for executive control processes, demonstrated by significantly worse performance on specific executive functioning subtests in participants with damage to these regions and their connecting white matter tracts [13].

Modern Expansions: Extended P-FIT (ExtPFIT)

Recent research has expanded the original P-FIT framework into an Extended P-FIT (ExtPFIT) model that incorporates additional brain regions and developmental perspectives. A 2020 multimodal neuroimaging study of 1,601 youths aged 8–22 from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort tested the P-FIT across structural and functional brain parameters in a single, well-powered study [15]. This research measured volume, gray matter density (GMD), mean diffusivity (MD), cerebral blood flow (CBF), resting-state fMRI measures of the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFFs) and regional homogeneity (ReHo), and activation to working memory and social cognition tasks [15].

The findings demonstrated that better cognitive performance was associated with higher volumes, greater GMD, lower MD, lower CBF, higher ALFF and ReHo, and greater activation for working memory tasks in P-FIT regions across age and sex groups [15]. However, the study also revealed that additional cortical, striatal, limbic, and cerebellar regions showed comparable effects, indicating that the original P-FIT needed expansion into an extended network incorporating nodes supporting motivation and affect [15]. The associations between brain parameters and cognitive performance strengthened with advancing age from childhood through adolescence to young adulthood, with these developmental effects occurring earlier in females [15]. The authors conceptualize this ExtPFIT network as "developmentally fine-tuned, optimizing abundance and integrity of neural tissue while maintaining a low resting energy state" [15].

Diagram 1: P-FIT to Extended P-FIT Model Evolution

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multimodal Neuroimaging Protocol (Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort)

The 2020 ExtPFIT study implemented a comprehensive multimodal imaging protocol in a sample of 1,601 participants aged 8–22, all studied on the same 3-Tesla scanner with contemporaneous cognitive assessment [15]. The methodology included rigorous quality assurance procedures, excluding participants for medical disorders affecting brain function, psychoactive medication use, prior inpatient psychiatric treatment, or structural brain abnormalities, with further exclusions for excessive motion during scanning [15].

The multimodal protocol encompassed seven distinct imaging modalities: (1) GM and WM volume and GMD from T1-weighted scans; (2) MD from DTI; (3) resting-state CBF from arterial spin-labeled sequences; (4) ALFF from rs-fMRI; (5) ReHo measures from rs-fMRI; (6) BOLD activation for an N-back working memory task; and (7) BOLD activation for an emotion identification social cognition task [15]. Neurocognitive assessment provided measures of accuracy and speed across multiple behavioral domains, with the primary cognitive measure being a factor score summarizing accuracy on executive functioning and complex cognition [15].

Lesion Study Methodology (Vietnam Head Injury Study)

The Phase 3 Vietnam Head Injury Study implemented voxel-based lesion symptom mapping to identify regions causally affecting cognitive performance [13]. This approach maps where brain damage impacts performance by comparing scores on intelligence test batteries between participants with and without lesions at every voxel [13]. The study included 182 male veterans from the registry who completed both the WAIS and selected measures from the Delis-Kaplan executive function system known to be sensitive to frontal lobe damage [13]. The methodology enabled identification of neural substrates shared between g and specific cognitive domains including Verbal Comprehension, Working Memory, Perceptual Organization, and Processing Speed [13].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for P-FIT Investigations

| Research Tool | Category | Function in P-FIT Research |

|---|---|---|

| 3-Tesla MRI Scanner | Imaging Hardware | High-field strength provides resolution for structural and functional imaging |

| Voxel-Based Morphometry | Software Algorithm | Quantifies regional gray matter volume and density correlations with intelligence |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging | Imaging Protocol | Maps white matter integrity and connectivity between P-FIT regions |

| Arterial Spin Labeling | Perfusion Imaging | Measures cerebral blood flow without exogenous contrast agents |

| Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuations | fMRI Analysis | Assesses spontaneous brain activity in resting state networks |

| Regional Homogeneity | fMRI Analysis | Measures local synchronization of brain activity |

| Voxel-Based Lesion Symptom Mapping | Lesion Analysis | Identifies causal brain-behavior relationships through lesion-deficit mapping |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scales | Cognitive Assessment | Standardized measures of intellectual functioning for correlation with brain parameters |

| Raven's Progressive Matrices | Cognitive Assessment | Culture-reduced measure of fluid reasoning ability |

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

While the P-FIT model enjoys substantial empirical support, several methodological considerations merit attention. A review of methods for identifying large-scale cognitive networks highlights the importance of multidimensional context in understanding neural bases of cognitive processes [13]. The authors caution that structural imaging and lesion studies, while valuable for implicating specific regions, provide limited insight into the dynamical nature of cognitive processes [13]. Furthermore, a review of intelligence neuroscience emphasizes the need for studies to consider different cognitive and neural strategies individuals may employ when completing cognitive tasks [13].

The P-FIT model exhibits high compatibility with the neural efficiency hypothesis and is supported by evidence relating white matter integrity to intelligence [13]. Studies indicate that white matter integrity provides the neural basis for rapid information processing, considered central to general intelligence [13]. This compatibility suggests that future research integrating these perspectives may yield more comprehensive models of intelligent information processing in the brain.

Diagram 2: Multimodal Neuroimaging Protocol for P-FIT Research

The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory has evolved from its original formulation to incorporate expanded neural networks and developmental perspectives. The original P-FIT model provided a parsimonious account relating individual differences in intelligence test scores to variations in brain structure and function across frontal, parietal, temporal, and cingulate regions [13] [14]. Modern evidence supports this core network while indicating the need for expansion to include striatal, limbic, and cerebellar regions that support motivation and affect—the Extended P-FIT model [15].

Future research directions should include longitudinal studies tracking the developmental fine-tuning of the ExtPFIT network from childhood through adulthood, with particular attention to sex differences in developmental trajectories [15]. Additionally, research integrating genetic markers with multimodal neuroimaging may help elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying individual differences in network efficiency [13]. The P-FIT framework continues to provide a valuable foundation for investigating the biological basis of human intelligence and its relationship to brain structure and function across the lifespan.

Linking Cortical Structure to Domain-General Cognitive Function (g)

Domain-general cognitive functioning (g) is a robust, replicated construct capturing individual differences in cognitive abilities such as reasoning, planning, and problem-solving [2]. It is associated with significant life outcomes, including educational attainment, health, and longevity. This whitepaper synthesizes the most current neuroimaging and neurobiological research to delineate the cortical signatures of g. We present quantitative meta-analytic findings from structural MRI, detail the underlying molecular and systems-level organization, and provide a framework for experimental protocols aimed at further elucidating these brain-cognition relationships. The findings underscore the potential for identifying multimodal brain signatures that can inform early risk detection and targeted interventions in cognitive decline and neuropsychiatric disorders [16].

The quest to understand the biological substrates of general cognitive function (g) has evolved from establishing simple brain-behavior correlations to decoding complex, multimodal neurobiological signatures. The parieto-frontal integration theory (P-FIT) provided an initial theoretical framework, positing that a distributed network of frontal and parietal regions supports complex cognition [2]. Contemporary research, powered by large-scale datasets and multi-modal integration, now seeks to move beyond descriptive associations to a mechanistic understanding. This involves characterizing the neurobiological properties—including cortical morphometry, gene expression patterns, neurotransmitter systems, and functional connectivity—that spatially covary with brain structural correlates of g [2] [17]. This whitepaper consolidates recent large-scale meta-analyses and methodological advances to serve as a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals exploring the cortical foundations of human cognition.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent large-scale meta-analyses on the cortical correlates of g.

Table 1: Meta-Analysis Cohorts and Morphometry Measures for g-Associations

| Cohort Name | Sample Size (N) | Age Range (Years) | Morphometry Measures Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank (UKB) | 36,744 | 44 - 83 [2] | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth [2] |

| Generation Scotland (GenScot) | 1,013 | 26 - 84 [2] | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth [2] |

| Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (LBC1936) | 622 | 44 - 84 [2] | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth [2] |

| Meta-Analytic Total | 38,379 | 44 - 84 | Volume, Surface Area, Thickness, Curvature, Sulcal Depth |

Table 2: Summary of Key g-Association Effect Sizes and Neurobiological Correlates

| Analysis Type | Key Finding | Effect Size / Correlation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

Global Brain Volume - g association |

Larger total brain volume associated with higher g [2] |

r = 0.275 (95% C.I. = [0.252, 0.299]) [2] | Found in a sample of N=18,363 [2] |

Vertex-Wise g-Morphometry |

Associations vary across cortex | β range = -0.12 to 0.17 [2] | Direction and magnitude depend on cortical location and morphometric measure |

| Cross-Cohort Consistency | Spatial patterns of g-morphometry associations |

Mean spatial correlation r = 0.57 (SD = 0.18) [2] | Indicates good replicability across independent cohorts |

Gene Expression - g Spatial Correlation |

Association with two major gene expression components | |r| range = 0.22 to 0.55 [2] | Medium-to-large effects for volume/surface area; weaker for thickness [17] |

| Specific Gene Identification | 29 genes identified beyond major components | |β| range = 0.18 to 0.53 [17] | Many linked to neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [17] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Large-Scale Meta-Analysis ofg-Cortical Morphometry

This protocol outlines the methodology for conducting a vertex-wise meta-analysis of associations between general cognitive functioning and cortical structure, as employed in recent landmark studies [2].

1. Participant Cohorts and Cognitive Phenotyping:

- Cohorts: Utilize large, population-based cohorts with brain MRI and cognitive data. Key examples include UK Biobank (UKB), Generation Scotland (GenScot), and the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (LBC1936) [2].

- General Cognitive Function (

g): Administer a battery of cognitive tests covering multiple domains (e.g., reasoning, memory, processing speed). Derive thegfactor using principal component analysis (PCA) or latent variable modeling on the cognitive test scores to capture the shared variance [2].

2. Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Processing:

- MRI Acquisition: Conduct T1-weighted structural MRI scans using standardized protocols across all sites.

- Cortical Surface Reconstruction: Process T1 images using automated software like FreeSurfer to reconstruct cortical surfaces and extract vertex-wise morphometry measures, including:

- Cortical Volume

- Surface Area

- Cortical Thickness

- Curvature

- Sulcal Depth [2]

- Quality Control: Implement rigorous QC. Exclude participants based on medical history (e.g., dementia, stroke, brain injury) and failed image processing runs [2].

3. Statistical Analysis within Cohorts:

- For each cohort, at each of the ~298,790 cortical vertices, run a general linear model for each morphometry measure (e.g.,

Volume ~ g + age + sex). - Register all individual-level statistical maps to a common surface space (e.g., fsaverage 164k) [2].

4. Meta-Analysis across Cohorts:

- Perform a random-effects meta-analysis at each vertex to combine association statistics (e.g., β-coefficients for the

gterm) across the independent cohorts. - The resulting meta-analytic maps show the spatial pattern of

g-morphometry associations across the entire cortex [2].

Spatial Correlation with Neurobiological Cortical Profiles

This methodology tests the spatial concordance between the meta-analytic g-morphometry maps and underlying neurobiological properties [2].

1. Assembly of Neurobiological Maps:

- Collate open-source brain maps of various neurobiological properties registered to the same common surface space. These may include:

- Neurotransmitter receptor/transporter densities (e.g., for serotonin, dopamine, GABA)

- Regional gene expression data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas

- Post-mortem cytoarchitectural maps

- Functional connectivity gradients derived from resting-state fMRI

- Metabolic maps (e.g., glucose metabolism) [2]

2. Dimensionality Reduction of Neurobiological Data:

- To address multicollinearity among the many neurobiological maps, perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

- This identifies a smaller number of major dimensions (e.g., 4 components accounting for ~66% of variance) that represent fundamental patterns of cortical organization [2].

3. Spatial Correlation Analysis:

- Cortex-Wide Correlation: Calculate the spatial correlation (e.g., Pearson's r) across all vertices between the

g-morphometry map and each neurobiological map (or its principal components). - Regional Correlation: Calculate spatial correlations within specific brain regions (e.g., using the Desikan-Killiany atlas with 34 regions per hemisphere) to assess regional variations in co-patterning [2].

- Statistical Significance: Assess significance using spin-based permutation tests to account for spatial autocorrelation inherent in cortical data [2].

Identifying Gene Expression Correlates ofg

This protocol details the analysis of the relationship between regional gene expression and g-morphometry associations [17].

1. Gene Expression Data Processing:

- Source regional gene expression data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA), which provides microarray data from post-mortem brains (e.g., N=6 donors).

- Map tissue samples to a standard cortical atlas (e.g., Desikan-Killiany with 68 regions). Calculate median expression values per region per gene across donors.

- Apply quality control to retain only genes with high between-donor consistency in regional expression profiles (e.g., ~8,235 genes) [17].

2. Defining General Dimensions of Gene Expression:

- Perform PCA on the region-by-gene expression matrix. This reveals major components of spatial co-variation in gene expression across the cortex (e.g., two components accounting for 49.4% of variance).

- Interpret these components via gene ontology (GO) analysis to identify enriched biological processes (e.g., "cell-signalling/modifications" vs. "transcription factors") [17].

3. Analysis of Spatial Associations with g:

- General Associations: Correlate the regional scores of the major gene expression components with the strength of regional

g-morphometry associations. - Gene-Specific Associations: For individual genes, compute the spatial correlation between their regional expression and the regional

g-morphometry association strengths, while controlling for the major general components to identify specific genetic correlates [17].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate core concepts and experimental workflows detailed in this whitepaper.

Experimental Workflow forgNeurosignature Research

Cortical Organization ofgand Gene Expression

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Resources for g Neurosignature Research

| Resource / Material | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Biobanks | Provides population-scale datasets with paired neuroimaging, cognitive, and genetic data for high-powered discovery and replication. | UK Biobank (UKB), Generation Scotland (GenScot), Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study [2] [16] |

| Cortical Parcellation Atlases | Standardizes brain region definitions for aggregating data across studies and performing regional-level analyses. | Desikan-Killiany Atlas, Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) Atlas, Harvard-Oxford Atlas (HOA) [2] [18] |

| Gene Expression Atlas | Provides post-mortem human brain data on the spatial distribution of gene expression across the cortex. | Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) [17] |

| Neurobiological Brain Maps | Open-source maps of molecular, structural, and functional properties for spatial correlation analyses with phenotype associations. | Neurotransmitter receptor maps, cytoarchitectural maps, functional connectivity gradients [2] |

| Surface-Based Analysis Software | Processes structural MRI data to reconstruct cortical surfaces and extract vertex-wise morphometry measures. | FreeSurfer [2] |

| Linked Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A data-driven multivariate method to identify co-varying patterns across different imaging modalities (e.g., structure and white matter). | Used in multimodal analysis of brain-behavior relationships [16] |

| Leverage-Score Sampling | A computational feature selection method to identify a minimal set of robust, individual-specific neural signatures from high-dimensional connectome data. | Used for identifying age-resilient functional connectivity biomarkers [18] |

Advanced Methodologies and Translational Applications in Signature Discovery

The human brain operates across multiple spatial and temporal scales, a characteristic that has long challenged neuroscientists. No single neuroimaging modality can fully capture the intricate dynamics of neural activity, from the rapid millisecond-scale electrophysiological events to the slower, metabolically coupled hemodynamic changes. Multimodal neuroimaging represents a paradigm shift, integrating complementary technologies to overcome the inherent limitations of individual methods and create a unified, high-resolution view of brain structure and function. This integrated approach is particularly vital for advancing the study of brain signatures of cognition, where understanding the complex interplay between neural electrical activity, metabolic demand, and vascular response is essential. By combining the superior temporal resolution of electrophysiological techniques like MEG and iEEG with the high spatial resolution of fMRI and the portability of fNIRS, researchers can now investigate cognitive processes with unprecedented comprehensiveness [19] [20]. This technical guide explores the principles, methodologies, and applications of integrating MRI, MEG, fNIRS, and iEEG, providing a framework for researchers aiming to decode the neurobiological foundations of human cognition.

Neuroimaging Modalities: Core Principles and Technical Specifications

Fundamental Biophysics of Individual Modalities

Each major neuroimaging modality captures distinct aspects of neural activity based on different biophysical principles:

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): fMRI primarily measures the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast, an indirect marker of neural activity. The BOLD signal arises from local changes in blood oxygenation, flow, and volume following neuronal activation. Deoxyhemoglobin is paramagnetic and acts as an intrinsic contrast agent, causing signal attenuation in T2*-weighted MRI sequences. When neural activity increases in a brain region, it triggers a coupled hemodynamic response, increasing cerebral blood flow that overshoots the oxygen metabolic demand, resulting in a local decrease in deoxyhemoglobin concentration and a subsequent increase in the MR signal [19]. This hemodynamic response is slow, peaking at 4-6 seconds post-stimulus, which limits fMRI's temporal resolution despite its excellent spatial resolution (millimeter range).

Magnetoencephalography (MEG): MEG measures the minute magnetic fields (10-100 fT) generated by the intracellular electrical currents in synchronously active pyramidal neurons. These magnetic fields pass through the skull and scalp undistorted, allowing for direct measurement of neural activity with millisecond temporal precision. The primary sources of MEG signals are postsynaptic potentials, particularly those occurring in the apical dendrites of pyramidal cells oriented parallel to the skull surface. Modern MEG systems using Optically Pumped Magnetometers (OPMs) offer advantages over traditional superconducting systems, including closer sensor placement to the head ("on-scalp" configuration) for increased signal power and more flexible experimental setups [19] [20].

Intracranial Electroencephalography (iEEG): Also known as electrocorticography (ECoG) when recorded from the cortical surface, iEEG involves placing electrodes directly on or within the brain tissue, typically for clinical monitoring in epilepsy patients. This invasive approach records electrical potentials with exceptional signal-to-noise ratio and high temporal resolution (<10 ms), capturing a broader frequency spectrum (0-500 Hz) than scalp EEG. iEEG provides direct access to high-frequency activity and action potentials, bypassing the signal attenuation and spatial blurring caused by the skull and scalp [19].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS): fNIRS is a non-invasive optical technique that measures hemodynamic responses by monitoring changes in the absorption spectra of near-infrared light as it passes through biological tissues. By measuring concentration changes of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR), fNIRS provides a hemodynamic correlate of neural activity similar to fMRI but with greater portability, lower cost, and higher tolerance for movement. Its limitations include relatively shallow penetration depth (cortical regions only) and lower spatial resolution compared to fMRI [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Modality Characteristics

Table 1: Technical specifications and characteristics of major neuroimaging modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Measured Signal | Invasiveness | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | 1-3 mm | 1-3 seconds | BOLD (hemodynamic) | Non-invasive | High spatial resolution, whole-brain coverage | Indirect measure, poor temporal resolution, scanner environment |

| MEG | 5-10 mm | <1 millisecond | Magnetic fields | Non-invasive | Excellent temporal resolution, direct neural measurement | Limited spatial resolution, sensitivity to superficial sources |

| iEEG | 1-10 mm | <10 milliseconds | Electrical potentials | Invasive | High spatiotemporal resolution, broad frequency range | Clinical population only, limited spatial coverage |

| fNIRS | 10-20 mm | 0.1-1 second | Hemoglobin concentration | Non-invasive | Portable, tolerant to movement, relatively low cost | Limited to cortical regions, depth penetration issues |

Integration Methodologies and Data Fusion Approaches

Neurovascular Coupling: The Biological Bridge

The integration of electrophysiological (MEG, iEEG) and hemodynamic (fMRI, fNIRS) modalities relies fundamentally on understanding neurovascular coupling - the biological mechanism that links neural activity to subsequent changes in cerebral blood flow and metabolism. The current model suggests that increased synaptic activity, particularly glutamatergic transmission, triggers astrocytic signaling that leads to vasodilation of local arterioles. This process is mediated by various metabolic and neural factors, including adenosine, potassium ions, nitric oxide, and arachidonic acid metabolites. The resulting hemodynamic response delivers oxygen and nutrients to support metabolic demands, forming the basis for both fMRI and fNIRS signals [19].