Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Resolving Discrepancies Between Automated and Manual Behavior Scoring

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with discrepancies between automated and manual behavior scoring.

Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Resolving Discrepancies Between Automated and Manual Behavior Scoring

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with discrepancies between automated and manual behavior scoring. It explores the fundamental causes of these divergences, from algorithmic limitations to environmental variables. The content delivers practical methodologies for implementation, advanced troubleshooting techniques, and robust validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from preclinical and clinical research, this guide empowers scientists to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and translational value of behavioral data in biomedical studies.

Understanding the Divide: Why Automated and Manual Behavior Scoring Disagree

FAQs: Understanding Human Annotation

What is a "gold standard" in research, and why is human annotation used to create it?

A gold standard in research is a high-quality, benchmark dataset used to train, evaluate, and validate machine learning systems and research methodologies [1]. Human experts create these benchmarks by manually generating the desired output for raw data inputs, a process known as annotation [2]. This is crucial because natural language descriptions or complex phenotypes are opaque to machine reasoning without being converted into a structured, machine-readable format [1]. Human annotation provides the "ground truth" that enables supervised machine learning, where a function learns to automatically create the desired output from the input data [2].

Why is there variability in human annotations, even among experts?

Variability, or inter-annotator disagreement, is common and arises from several sources [3] [4]. Even highly experienced experts can disagree due to inherent biases, differences in judgment, and occasional "slips" [3]. Key reasons include:

- Subjectivity in the Labelling Task: Annotation often requires judgment, not just mechanical diagnosis, leading to legitimate differences in interpretation [3].

- Insufficient Information: Unclear guidelines or poor quality data can lead to different deductions about the original intent [1] [3].

- Human Error and Noise: Unwanted variability can occur due to cognitive overload or simple mistakes [3].

- Differences in Methodology and Context: Experts may use varying methodologies or be influenced by their specific domain expertise, leading to different conclusions [5].

How is the quality and consistency of human annotations measured?

The consistency of annotations is typically quantified using statistical measures of inter-rater agreement. The most common metrics are Fleiss' Kappa (κ) for multiple annotators and Cohen's Kappa for two annotators [3]. The values on these scales indicate the strength of agreement, which can range from "none" to "almost perfect". For example, a Fleiss' κ of 0.383 is considered "fair" agreement, while a Cohen's κ of 0.255 indicates "minimal" agreement [3].

What is the practical impact of using inconsistently annotated data to train an AI model?

Using inconsistently annotated ("noisy") data for training can have significant negative consequences. It can lead to [3]:

- Decreased classification accuracy of the resulting AI model.

- Increased model complexity.

- Increased number of training samples needed.

- Difficulty in selecting the right features for the model. In clinical settings, this can result in AI-driven clinical decision-support systems with unpredictable and potentially harmful consequences [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Inter-Annotator Agreement

Problem: Different human experts are assigning different labels to the same data instances, leading to an unreliable gold standard.

Solution:

- Refine Annotation Guidelines: Ensure the protocol for annotation is exceptionally clear, detailed, and includes examples for edge cases. Re-train annotators on the revised guidelines [3] [2].

- Expand Ontology Coverage: In fields like biology, the underlying ontologies used for annotation may lack terms. Adding new, relevant ontology terms has been shown to increase the accuracy and consistency of both human and machine annotations [1].

- Implement a Consensus Process: For critical gold standard datasets, do not rely on a single annotator. Have multiple annotators label the same data and establish a consensus method, such as adjudication by a "super-expert" or a majority vote [3] [2].

- Assess Annotation Learnability: Research suggests that instead of using all annotated data, better models can be built by determining consensus using only datasets where the annotations show high 'learnability' [3].

Issue: Resolving Discrepancies Between Human and Automated Scoring

Problem: An automated scoring system is producing results that are significantly different from the traditional human-based manual assessment.

Solution:

- Quantify the Disagreement: Use appropriate statistical methods to understand the scope of the discrepancy. A study comparing automated and manual Balance Error Scoring System (BESS) scoring used a linear mixed model and Bland-Altman analyses to determine the limits of agreement between the two methods [6].

- Evaluate the Gold Standard: Scrutinize the human annotations for inherent variability. Recognize that human judgment is not infallible and can be a source of noise. The performance of automated systems should be evaluated against a high-quality, expert-curated gold standard [1].

- Consider the Trade-offs: Acknowledge that the two methods may be fundamentally different. In the BESS study, the two scoring methods showed "wide limits of agreement," meaning they are not interchangeable. The choice of method should be based on the specific needs of the clinical use or research study [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Evaluating an Automated vs. Human Scoring System

This methodology is adapted from a study comparing automated and traditional scoring for the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS) [6].

- Objective: To evaluate the performance and agreement between an automated computer-based scoring system and traditional human-based manual assessment.

- Experimental Design: A descriptive cross-sectional study design.

- Participants: 51 healthy, active participants.

- Procedure:

- Participants perform BESS trials following standard procedures on an instrumented pressure mat.

- Trained human evaluators manually score balance errors from video recordings.

- The same trials are scored using an automated software that analyzes center of force measurements from the pressure mat.

- Statistical Analysis:

- A linear mixed model is used to determine measurement discrepancies across the two methods.

- Bland-Altman analyses are conducted to determine the limits of agreement between the automated and manual scoring methods.

Protocol: Measuring Inter-Curator Consistency in Phenotype Annotation

This methodology is adapted from a study on annotating evolutionary phenotypes [1].

- Objective: To assess the consistency of human annotations and create a high-quality gold standard dataset.

- Experimental Design: An inter-curator consistency experiment.

- Procedure:

- Selection: A set of phenotype descriptions (e.g., 203 characters from phylogenetic matrices) is randomly selected.

- Independent Annotation: Multiple curators (e.g., three) independently annotate the same set of descriptions into a logical Entity-Quality (EQ) format, using a provided set of initial ontologies.

- Rounds of Annotation:

- Naïve Round: Curators are not allowed access to any external sources of knowledge.

- Knowledge Round: Curators are permitted to access the full publication, related literature, and other online sources to deduce the original author's intent.

- Ontology Augmentation: New ontology terms created by curators during the process are added to the initial set.

- Gold Standard Creation: The final gold standard is developed by achieving consensus among the curators.

- Evaluation: Annotator consistency is measured using ontology-aware semantic similarity metrics and, ideally, evaluated by the original authors of the descriptions.

Quantitative Data on Annotation Variability

Table 1: Inter-Annotator Agreement in Clinical Settings [3]

| Field of Study | Annotation Task | Agreement Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive Care | Patient severity scoring | Fleiss' κ | 0.383 | Fair agreement |

| Pathology | Diagnosing breast lesions | Fleiss' κ | 0.34 | Fair agreement |

| Psychiatry | Diagnosing major depressive disorder | Fleiss' κ | 0.28 | Fair agreement |

| Intensive Care | Identifying periodic EEG discharges | Avg. Cohen's κ | 0.38 | Minimal agreement |

Table 2: Comparison of Automated vs. Human Scoring Performance [6]

| Stance Condition | Statistical result (p-value) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Bilateral Firm Stance | Not Significant (p ≥ .05) | No significant difference between methods |

| All Other Conditions | Significant (p < .05) | Significant difference between methods |

| Tandem Foam Stance | Most significant discrepancy | Greatest difference between methods |

| Tandem Firm Stance | Least significant discrepancy | Smallest difference between methods |

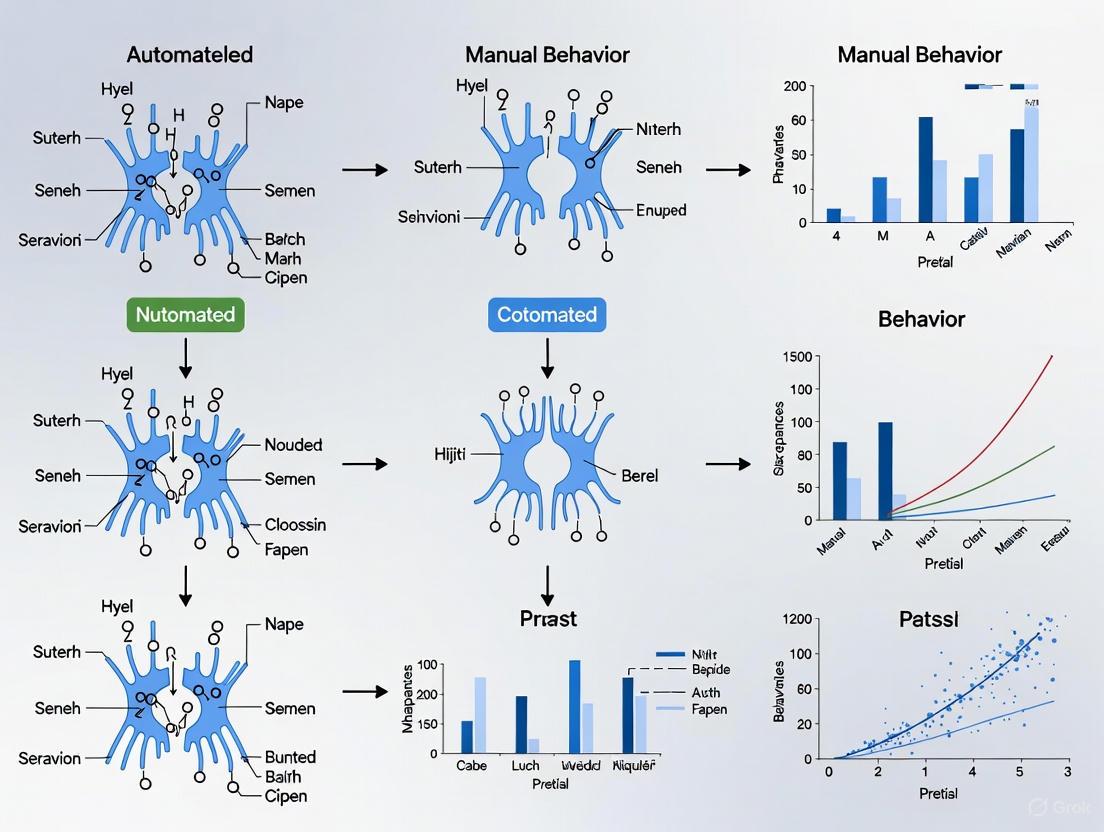

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Gold Standard Annotation and Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Resolving Human vs. Automated Scoring Discrepancies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Annotation and Validation Research

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fleiss' Kappa / Cohen's Kappa | Statistical measure of inter-rater agreement for multiple or two raters, respectively. | Quantifying the consistency among clinical experts labeling patient severity [3]. |

| Bland-Altman Analysis | A method to assess the agreement between two different measurement techniques. | Determining the limits of agreement between automated and manual BESS scoring systems [6]. |

| Ontologies (e.g., Uberon, PATO) | Structured, controlled vocabaries that represent entities and qualities. | Providing the standard terms needed to create machine-readable phenotype annotations (e.g., Entity-Quality format) [1]. |

| Semantic Similarity Metrics | Ontology-aware metrics that account for partial semantic similarity between annotations. | Evaluating how closely machine-generated annotations match a human gold standard, beyond simple exact-match comparisons [1]. |

| Annotation Platforms (e.g., CVAT, Label Studio) | Open-source tools to manage the process of manual data labeling. | Providing a structured environment for annotators to label images, text, or video according to a defined protocol [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does the automated system score answers from non-native speakers differently than human raters?

Research indicates that this is a common form of demographic disparity. A study on automatic short answer scoring found that students who primarily spoke a foreign language at home received significantly higher automatic scores than their actual performance warranted. This happens because the system may latch onto specific, simpler language patterns that are more common in this group's responses, rather than accurately assessing the content's correctness. To investigate, you should disaggregate your scoring accuracy data by language background [7].

Q2: Our automated scoring has high overall accuracy, but we suspect it is unfair to a specific subgroup. How can we test this?

The core methodology is to perform a bias audit. Compare the agreement rates between human and machine scores across different demographic subgroups (e.g., gender, language background, etc.). A fair system should have similar error rates (e.g., false positives and false negatives) for all groups. A significant difference in these rates, as found in studies focusing on language background, indicates algorithmic bias [7].

Q3: What are the most common technical sources of error in training a scoring model?

The primary sources are often in the initial stages of the machine learning pipeline [7]:

- Data Collection: If your training data is not representative of the entire population of respondents, the model will be less accurate for underrepresented groups. This is known as representation bias.

- Scoring/Labeling: The quality of your human-scored training data is paramount. If the human ratings are biased or inconsistent ("garbage in, garbage out"), the model will learn and amplify these biases [7].

Q4: How can the design of an evaluation form itself introduce scoring errors?

If using a commercial automated evaluation system, poor question design is a major source of error. The guidelines for such systems recommend [8]:

- Avoid Subjective Queries: Questions like "Was the agent patient?" are hard for AI to score reliably.

- Focus on Transcript-Driven Evidence: Rephrase questions to be specific and measurable, e.g., "Did the agent allow the customer to finish speaking without interruption?"

- Improve Clarity: Use complete sentences and consistent terminology to avoid confusing the scoring model.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Scoring Discrepancies

| Problem Area | Symptoms | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Bias | High error rates for a specific demographic group; model performance varies significantly between groups. | 1. Disaggregate validation results by gender, language background, etc. [7]. 2. Check training data for balanced representation of all subgroups. | 1. Collect more representative training data. 2. Apply algorithmic fairness techniques to mitigate discovered biases. |

| Labeling Inconsistency | The model seems to learn the wrong patterns; human raters disagree with each other frequently. | 1. Measure inter-rater reliability (IRR) for your human scorers. 2. Review the coding guide for ambiguity. | 1. Retrain human raters using a refined, clearer coding guide. 2. Re-label training data after improving IRR. |

| Model & Feature Issues | The model fails to generalize to new data; it performs well on training data but poorly in production. | 1. Analyze the features (e.g., word embeddings) the model uses. 2. Test different semantic representations and classification algorithms [7]. | 1. Try a different model (e.g., SVM with RoBERTa embeddings showed high accuracy [7]). 2. Expand the feature set to better capture the intended construct. |

| Question/Form Design | Low confidence scores from the AI; human reviewers consistently override automated scores. | 1. Audit evaluation form questions for subjectivity and ambiguity [8]. 2. Check if questions can be answered from the available data (e.g., transcript). | 1. Rephrase questions to be objective and evidence-based. 2. Add detailed "help text" to provide context for the AI scorer [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Discrepancy Investigation

Protocol 1: Auditing for Demographic Disparity

This protocol is designed to detect and quantify bias in your automated scoring system against specific demographic groups, a problem identified in research on automatic short answer scoring [7].

1. Objective: To determine if the automatic scoring system produces significantly different error rates for subgroups based on gender or language background.

2. Materials & Dataset:

- A dataset of text responses that has been scored by both human experts and the automated system.

- Demographic metadata for each respondent (e.g., gender, language spoken at home).

- The dataset should be large enough to allow for statistically significant comparisons between groups (e.g., the study by Schmude et al. used n = 38,722 responses [7]).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Split the data into subgroups based on the demographic characteristics of interest.

- Step 2: Performance Calculation. For each subgroup, calculate the following metrics by comparing machine scores to human scores:

- Accuracy: The overall proportion of correct scores.

- False Positive Rate: The proportion of incorrect answers that were mistakenly scored as correct.

- False Negative Rate: The proportion of correct answers that were mistakenly scored as incorrect.

- Step 3: Statistical Comparison. Use statistical tests (e.g., t-tests) to determine if the differences in the metrics from Step 2 between subgroups are significant.

4. Interpretation: A significant difference in false positive or false negative rates indicates a demographic disparity. For example, a study found that students speaking a foreign language at home had a higher false positive rate, meaning the machine was too lenient with this group [7].

Protocol 2: Validating Form Questions for AI Scoring

This protocol ensures that questions in an evaluation form are correctly interpreted by an AI scoring engine, minimizing processing failures and low-confidence answers [8].

1. Objective: To refine and validate evaluation form questions to maximize the accuracy and reliability of automated scoring.

2. Materials:

- A draft evaluation form with questions and potential answer choices.

- Access to a set of real or simulated conversation transcripts that the form is designed to evaluate.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Clarity Review. For each question, check if it meets the following criteria [8]:

- Is it a complete sentence, not shorthand?

- Is it based solely on evidence available in the transcript?

- Is it free from subjective terms and based on measurable, observable actions?

- Does it use consistent terminology?

- Step 2: Add Help Text. For each question, write "help text" that provides additional context and specific criteria for the AI to use when scoring. Example: For "Did the agent confirm the customer's identity?", help text could be: "Agents must verify the customer’s phone number and order ID before resolving the issue." [8]

- Step 3: Pilot Testing. Run the form against a sample of transcripts. Monitor for system errors like "Low confidence on question" or "Processing failure" [8].

- Step 4: Iterative Refinement. Based on the pilot results, rephrase questions that cause errors and retest. The goal is to achieve a high "rolling accuracy" where human reviewers rarely need to edit the AI's scores [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Automated Scoring Research |

|---|---|

| Human-Scored Text Response Dataset | Serves as the "gold standard" ground truth for training and validating automated scoring models. The quality and bias in this dataset directly impact the model's performance [7]. |

| Semantic Representation Models (e.g., RoBERTa) | These models convert text responses into numerical vectors (embeddings) that capture linguistic meaning. They form the foundational features for classification algorithms [7]. |

| Classification Algorithms (e.g., Support Vector Machines) | These are the core engines that learn the patterns distinguishing correct from incorrect answers based on the semantic representations. Different algorithms may have varying performance and bias profiles [7]. |

| Demographic Metadata | Data on respondent characteristics (gender, language background) is not used for scoring but is essential for auditing the system for fairness and identifying demographic disparities [7]. |

| Algorithmic Fairness Toolkits | Software libraries that provide standardized metrics and statistical tests for quantifying bias (e.g., differences in false positive rates between groups), moving fairness checks from ad-hoc to systematic [7]. |

Table 1: Algorithmic Fairness Findings from Short Answer Scoring Study

This table summarizes key quantitative results from a study that analyzed algorithmic bias in automatic short answer scoring for 38,722 text responses from the 2015 German PISA assessment [7].

| Metric | Finding | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Bias | No discernible gender differences were found in the classifications from the most accurate method (SVM with RoBERTa) [7]. | Suggests that gender may not be a primary source of bias in all systems, but auditing for it remains critical. |

| Language Background Bias | A minor significant bias was found. Students speaking mainly a foreign language at home received significantly higher automatic scores than warranted by their actual performance [7]. | Indicates that systems can unfairly advantage certain linguistic groups, potentially due to learned patterns in simpler or more formulaic responses. |

| Primary Contributing Factor | Lower-performing groups with more incorrect responses tended to receive more correct scores from the machine because incorrect responses were generally less likely to be recognized [7]. | Highlights that overall system accuracy can mask significant biases against specific subgroups, necessitating disaggregated analysis. |

Table 2: WCAG Color Contrast Requirements for Visualizations

To ensure your diagrams and interfaces are accessible to all users, including those with low vision, adhere to these Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) for color contrast [9] [10] [11].

| Element Type | Minimum Ratio (AA Rating) | Enhanced Ratio (AAA Rating) | Example Use Case in Diagrams |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Text | 4.5:1 [11] | 7:1 [11] | Any explanatory text within a node. |

| Large Text (18pt+ or 14pt+ bold) | 3:1 [9] [11] | 4.5:1 [11] | Large titles or labels. |

| User Interface Components & Graphical Objects | 3:1 [10] [11] | Not defined | Arrows, lines, symbol borders, and the contrast between adjacent data series. |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Machine Learning Pipeline Vulnerability

Scoring Discrepancy Investigation

The Impact of Context and Environment on Scoring Consistency

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides resources for researchers addressing discrepancies between automated and manual scoring methods in scientific experiments, particularly in drug development and behavioral research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my automated and manual scoring results show significant discrepancies?

Automated systems excel at consistent, repeatable measurements but can miss nuanced, context-dependent factors that human scorers identify. Key mediators include:

- System Capabilities: Automated systems may overlook novel or unexpected response patterns that fall outside training data [12].

- Scoring Environment: The quality of input data (e.g., noise, variability in experimental conditions) significantly impacts automated scoring reliability [13].

- Procedural Context: Differences in application or interpretation of scoring rubrics between human teams and automated parameters create inconsistency [13].

Q2: What strategies can improve alignment between scoring methods?

- Implement Hybrid Scoring Models: Use automated systems for initial, high-volume scoring with manual review for borderline cases or a sample for validation [14].

- Enrich Automated Systems with Contextual Parameters: Move beyond basic scoring to incorporate contextual mediators as defined in Integral Theory frameworks [13].

- Establish Rigorous Validation Protocols: Continuously validate automated scores against manual benchmarks, especially when experimental conditions change [15].

Q3: How much correlation should I expect between automated and manual scoring?

Correlation strength depends on the measured metric. One study on creativity assessment found:

- Very Strong Correlation (rho = 0.76) for elaboration scores [15].

- Weak but Significant Correlation (rho = 0.21) for originality scores [15].

- Weak Correlation (approx. rho = 0.1-0.13) between creative self-belief and manual fluency/originality [15].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Automated system fails to replicate expert manual scores for essay responses.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Feature Extraction | Analyze which essay aspects (coherence, relevance) show greatest variance [12]. | Retrain system with expanded feature set focusing on semantic content over stylistic elements [12]. |

| Poorly Defined Rubrics | Conduct inter-rater reliability check among manual scorers [12]. | Refine scoring rubric with explicit, quantifiable criteria; recalibrate automated system to new rubric [12]. |

| Contextual Blind Spots | Check if automated system was trained in different domain context [13]. | Fine-tune algorithms with domain-specific data; implement context-specific scoring rules [13]. |

Problem: Inconsistent scoring results across different experimental sites or conditions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Environmental Variables | Audit site-specific procedures and environmental conditions [13]. | Implement standardized protocols and environmental controls; use statistical adjustments for residual variance [13]. |

| Instrument/Platform Drift | Run standardized control samples across all sites and platforms [16]. | Establish regular calibration schedule; use standardized reference materials across sites [16]. |

| Criterion Contamination | Review how local context influences scorer interpretations [13]. | Provide centralized training; implement blinding procedures; use automated pre-scoring to minimize human bias [13]. |

Quantitative Data on Scoring and Method Performance

Table 1: Clinical Drug Development Failure Analysis (2010-2017)

| Failure Cause | Percentage of Failures | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy | 40-50% | Biological discrepancy between models/humans; inadequate target validation [17]. |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | 30% | Off-target or on-target toxicity; tissue accumulation in vital organs [17]. |

| Poor Drug-Like Properties | 10-15% | Suboptimal solubility, permeability, metabolic stability [17]. |

| Commercial/Strategic Issues | ~10% | Lack of commercial needs; poor strategic planning [17]. |

Table 2: STAR Classification for Drug Candidate Optimization

| Class | Specificity/Potency | Tissue Exposure/Selectivity | Clinical Dose | Efficacy/Toxicity Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | High | High | Low | Superior efficacy/safety; high success rate [17]. |

| II | High | Low | High | High toxicity; requires cautious evaluation [17]. |

| III | Adequate | High | Low | Manageable toxicity; often overlooked [17]. |

| IV | Low | Low | N/A | Inadequate efficacy/safety; should be terminated early [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Scoring Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Automated Essay Scoring Systems

Purpose: Establish correlation between automated essay scoring and expert human evaluation.

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: Obtain standardized essay responses with human scores (e.g., Cambridge Learner Corpus) [12].

- Feature Extraction: Implement NLP techniques to extract syntactic, semantic, and structural features [12].

- Model Training: Apply machine learning (regression, classification, neural networks) using human scores as ground truth [12].

- Validation: Use cross-validation; measure agreement with quadratic weighted kappa or Pearson correlation [12].

Evaluation Metrics:

- Accuracy Measures: Quadratic Weighted Kappa (QWK), Pearson Correlation, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [12].

- Benchmarking: Compare automated-human agreement to inter-human agreement rates [12].

Protocol 2: Cross-Method Validation for Behavioral Coding

Purpose: Ensure consistency between manual and automated behavioral scoring.

Methodology:

- Parallel Scoring: Apply both manual and automated scoring to identical dataset [15].

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Spearman's rho) between methods [15].

- Bias Detection: Use Bland-Altman plots to identify systematic differences between methods [15].

- Contextual Analysis: Test whether correlations vary under different experimental conditions [13].

Research Workflow Visualization

Scoring System Development Workflow

Context Impact on Scoring Consistency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Scoring Validation Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Datasets (e.g., Cambridge Learner Corpus) | Provide benchmark data with human scores for validation [12]. | Essential for establishing baseline performance of automated systems. |

| Open Creativity Scoring with AI (OCSAI) | Automated scoring of creativity tasks like Alternate Uses Test [15]. | Shows strong correlation (rho=0.76) with manual elaboration scoring [15]. |

| Validation Software Suites (e.g., Phoenix Validation Suite) | Automated validation of analytical software in regulated environments [16]. | Reduces validation time from days to minutes while ensuring regulatory compliance [16]. |

| Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity-Activity Relationship (STAR) | Framework for classifying drug candidates based on multiple properties [17]. | Improves prediction of clinical dose/efficacy/toxicity balance [17]. |

| Environmental Performance Index (EPI) | Objective environmental indicators for validation of survey instruments [18]. | Measures correlation between subjective attitudes and objective conditions [18]. |

| GAMP 5 Framework | Risk-based approach for compliant GxP computerized systems [16]. | Provides methodology for leveraging vendor validation to reduce internal burden [16]. |

The drive for increased experimental throughput in genetics and neuroscience has fueled a revolution in behavioral automation [19]. This automation integrates behavior with physiology, allowing for unprecedented quantitation of actions in increasingly naturalistic environments. However, this same automation can obscure subtle behavioral effects that are readily apparent to human observers. This case study examines the critical discrepancies between automated and manual behavior scoring, providing a technical framework for diagnosing and resolving these issues within the research laboratory.

Key Discrepancies: Where Automation Fails to Capture Nuance

Automated systems excel at quantifying straightforward, high-level behaviors but often struggle with nuanced or complex interactions. The table below summarizes common failure points identified in the literature.

Table 1: Common Limitations in Automated Behavioral Scoring

| Behavioral Domain | Automated System Limitation | Manual Scoring Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Social Interactions | May track location but miss subtle action-types (e.g., wing threat, lunging in flies) [19]. | Trained observer can identify and classify complex, multi-component actions. |

| Action Classification | Machine learning classifiers can be confounded by novel behaviors or subtle stance variations [19]. | Human intuition can adapt to new behavioral patterns and contextual cues. |

| Environmental Context | Requires unobstructed images, limiting use in enriched, complex home cages [19]. | Observer can interpret behavior within a naturalistic, complex environment. |

| Sensorimotor Integrity | May misinterpret genetic cognitive phenotypes if basic sensorimotor functions are not first validated [19]. | Can holistically assess an animal's general health and motor function. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for Your Research

Q1: Our automated tracking system (e.g., EthoVision, ANY-maze) for rodent home cages is producing erratic locomotion data that doesn't match manual observations. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Contrast or Environmental Interference. The system may be losing track of the animal due to poor contrast between the animal and the bedding, or obstructions in the cage like enrichment items [19].

- Solution:

- Verify Contrast: Ensure the animal's fur color has a high contrast ratio against the background. While WCAG standards for web accessibility recommend a ratio of at least 4.5:1 for text, this principle applies to visual tracking [20] [21]. Use a grayscale card to check.

- Simplify Environment: Temporarily remove enrichment items that obstruct the camera's view to see if tracking improves. Consider alternative systems like LABORAS, which detect floor movements and are less constrained by environmental complexity [19].

- Adjust Lighting: Ensure consistent, shadow-free illumination to prevent the system from misinterpreting dark patches as the animal.

Q2: The software classifying aggressive behaviors in Drosophila (e.g., CADABRA) is missing specific action-types like "wing threats." How can we improve accuracy?

- Potential Cause: Inadequate Feature Extraction. The software's geometric features (e.g., velocity, wing angle) may not be sensitive enough to capture the specific limb position or stance of the subtle behavior [19].

- Solution:

- Re-train the Classifier: Use a larger and more specific training dataset that includes multiple examples of the "wing threat" stance from various angles. The quality of a machine-learning classifier is directly dependent on the training data [19].

- Validate with Manual Ethograms: Always run a parallel manual scoring session on a subset of your videos. Use the manually generated ethograms as a ground truth to validate and calibrate the automated output [19]. This process is critical for ensuring the automated version probes the same behavior.

Q3: We see a significant difference in results for a spatial memory test (e.g., T-maze) when we switch from a manual to a continuous, automated protocol. Are we measuring the same behavior?

- Potential Cause: Unintended Variables in Automation. The automated version may introduce or remove key stressors and handling effects, such as the scent of the experimenter or the sound of the door opening, which can be part of the contextual learning process [19].

- Solution:

- Concareful Validation: Systematically compare the two methods in a validation study. Ensure that the automated version of a paradigm is probing the same underlying behavior by checking for similar effect sizes and patterns in a wild-type strain before testing mutants [19].

- Monitor for New Confounds: Automated systems can have new failure modes. Check for technical issues like sensor errors, software freezes, or incorrect stimulus delivery that could explain the discrepancy.

Experimental Protocol: Validating Automated Behavioral Scoring Systems

Objective: To systematically compare and validate the output of an automated behavior scoring system against manual scoring by trained human observers.

Methodology:

- Video Recording: Record high-resolution video of the subjects (e.g., mice, flies) in the behavioral paradigm. Ensure lighting and camera angles are consistent across all sessions.

- Blinded Manual Scoring: Have two or more trained researchers, blinded to the experimental groups, score the videos using a detailed ethogram. Calculate the inter-rater reliability to ensure consistency in manual scoring.

- Automated Scoring: Process the same set of videos through the automated tracking and classification software (e.g., Ctrax for flies, EthoVision for rodents) using standard protocols [19].

- Data Comparison: For each behavioral metric (e.g., distance traveled, number of rearings, frequency of specific social interactions), perform a correlation analysis between the manual scores and the automated output.

- Bland-Altman Analysis: Use this statistical method to assess the agreement between the two measurement techniques. It will show the average difference (bias) between the methods and the limits of agreement, revealing any systematic errors in the automation [22].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Behavioral Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| High-Definition Cameras | Captures fine-grained behavioral details for both manual and automated analysis. |

| Open-Source Tracking Software (e.g., pySolo, Ctrax) | Provides a customizable platform for automated behavior capture and analysis, often with better spatial resolution than conventional systems [19]. |

| Behavioral Annotation Software (e.g., BORIS) | Aids in the efficient and standardized creation of manual ethograms by human observers. |

| Standardized Ethogram Template | A predefined list of behaviors with clear definitions; ensures consistency and reliability in manual scoring across different researchers. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python) | Used to perform correlation analyses, Bland-Altman plots, and other statistical comparisons between manual and automated datasets. |

The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from the literature on the performance and validation of automated systems.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Automated Systems in Behavioral Research

| System / Study | Reported Automated Performance | Context & Validation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CADABRA (Drosophila) | Decreased time to produce ethograms by ~1000-fold [19]. | Capable of detecting subtle strain differences, but requires human-trained action classification. |

| Automated Medication Verification (AMVS) | Achieved >95% accuracy in identifying drug types [23]. | Performance declined (93% accuracy) with increased complexity (10 drug types). |

| Pharmacogenomic Patient Selection | Automated algorithm was 33% more effective at identifying patients with clinically significant interactions (62% vs. 29%) [22]. | Highlights that manual (medication count) and automated methods select different patient cohorts. |

| Between-Lab Standardization | Human handling and lab-idiosyncrasies contribute to systematic errors, undermining reproducibility [19]. | Automation that obviates human contact is proposed as a mitigation strategy. |

Visualizing the Validation Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving a discrepancy between automated and manual scoring, a core process for any behavioral lab.

Diagnosing Automated Scoring Discrepancies

A sophisticated approach to behavioral research recognizes automation not as a replacement for human observation, but as a powerful tool that must be continuously validated against it. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, validation protocols, and diagnostic workflows outlined in this case study, researchers can critically assess their tools, ensure the integrity of their data, and confidently interpret the subtle behavioral effects that are central to understanding brain function and drug efficacy.

Building a Cohesive System: Methodologies for Integrating Automated and Manual Scoring

Implementing Unified Scoring Models to Maximize Data Utility

Fundamental Concepts and Troubleshooting Guide

What is a Unified Scoring Model?

A Unified Scoring Model refers to a single, versatile model architecture capable of handling multiple, distinct scoring tasks using one set of parameters. In behavioral research, this translates to a single AI model that can evaluate diverse behaviors—such as self-explanations, think-aloud protocols, summarizations, and paraphrases—based on various expert-defined rubrics, instead of requiring separate, specialized models for each task [24]. The core advantage is maximized data utility, as the model learns a richer, more generalized representation from the confluence of multiple data types and scoring criteria.

Troubleshooting Common Discrepancies

Discrepancies between automated unified model scores and manual human ratings often stem from a few common sources. The following guide addresses these specific issues in a question-and-answer format.

Q1: Our unified model's scores show a consistent bias, systematically rating certain types of responses higher or lower than human experts. How can we diagnose and correct this?

- Diagnosis: This often indicates that the model has failed to fully capture the nuances of the expert rubric for a particular subclass of data (e.g., short responses, responses with complex syntax, or responses from a specific demographic).

- Solution:

- Error Analysis: Conduct a granular analysis of the discrepancies. Manually review all responses where the model's score diverges significantly from the human score (e.g., by more than one point on a Likert scale). Categorize these errors to identify patterns.

- Data Augmentation: For the identified subclasses with poor performance, source or generate additional training examples. The goal is to re-balance the training data so the model learns the correct scoring policy for these cases.

- Multi-Task Fine-Tuning: If you are training separate models for each rubric, switch to a multi-task fine-tuning approach. Research shows that training a single model across multiple scoring tasks consistently outperforms single-task training by enhancing generalization and mitigating overfitting to idiosyncrasies in any single dataset [24].

Q2: The model performs well on most metrics but fails to replicate the correlation structure between different scoring rubrics that is observed in the manual scores. Why is this happening, and how critical is it?

- Diagnosis: This is a fundamental challenge in synthetic data generation and automated scoring. The model may be accurately predicting individual variable means but failing to capture the intricate pairwise dependencies (correlations) that exist in the real, expert-generated data [25].

- Solution:

- Assess Correlation Fidelity: Use the Propensity Score Mean-Squared Error (pMSE) or directly compare correlation matrices between your model's outputs and the manual scoring ground truth. This provides a quantitative measure of utility preservation beyond simple accuracy [25].

- Prioritize Robust Methods: Be mindful that different model architectures have varying capabilities in capturing correlation structures. One study found that statistical methods like

synthpopandcopulaconsistently outperformed deep learning approaches in replicating correlation structures in tabular data, though the latter may excel with highly complex datasets given sufficient resources and tuning [25]. - Criticality Check: The importance of perfectly replicating correlations depends on your downstream use case. If the relationship between scores (e.g., between "cohesion" and "wording quality") is a key analysis variable, then this discrepancy is critical to resolve. If only the individual scores are used, it may be less so.

Q3: We are concerned about the "black box" nature of our unified model. How can we build trust in its scores and ensure it is evaluating based on the right features?

- Diagnosis: A lack of interpretability can hinder adoption, especially in critical fields like drug development where understanding the "why" behind a score is as important as the score itself.

- Solution:

- Leverage Model Explainability (XAI) Tools: Implement techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to analyze individual predictions. These tools can highlight which words, phrases, or features in the input text most influenced the final score.

- Variable Importance Analysis: For simpler models or engineered features, perform a variable importance analysis. This helps validate that the model is relying on features that are semantically meaningful for the task, rather than spurious correlations [25].

- Adversarial Validation: Create a dataset of "adversarial" examples designed to trick the model. If the model fails on these, it reveals weaknesses in its reasoning and helps you refine the training data and objectives.

Q4: Our model achieves high performance on our internal test set but generalizes poorly to new, unseen data from a slightly different distribution. How can we improve robustness?

- Diagnosis: This is a classic case of overfitting. The model has memorized the specifics of your training data rather than learning the underlying, generalizable scoring function.

- Solution:

- Architectural Improvements: Adopt a unified model design that incorporates mechanisms for generalization. For instance, the UniCO framework for combinatorial optimization uses a "CO-prefix" to aggregate static problem features and a two-stage self-supervised learning approach to handle heterogeneous data, which improves its ability to generalize to new, unseen problems with minimal fine-tuning [26].

- Regularization: Increase the strength of regularization techniques (e.g., L1/L2 regularization, dropout) during training.

- Data Diversity: Ensure your training data encompasses the full spectrum of response types, styles, and domains you expect to encounter in production. Diversity in training data is one of the most effective guards against poor generalization.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure your unified scoring model is valid and reliable, follow these detailed experimental protocols.

Protocol for Benchmarking Against Manual Scoring

Objective: To quantitatively compare the performance of the unified scoring model against manual expert scoring, establishing its validity and identifying areas for improvement.

Methodology:

- Data Splitting: Split your expert-annotated dataset into training, validation, and a held-out test set (e.g., 70/15/15). The test set must be completely unseen during model development.

- Model Training: Train the unified scoring model on the training set. If using a multi-task setup, ensure all scoring rubrics are trained simultaneously.

- Prediction & Comparison: Run the trained model on the held-out test set to generate automated scores.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate inter-rater reliability metrics between the model and the human experts. Key metrics include:

- Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): For continuous scores, to measure agreement.

- Cohen's Kappa or Fleiss' Kappa: For categorical scores, to account for chance agreement.

- Pearson/Spearman Correlation: To measure the strength of the ordinal relationship.

- Error Analysis: As described in the troubleshooting section, manually analyze discrepancies to understand the model's failure modes.

Protocol for Evaluating Cross-Domain Generalization

Objective: To assess the model's ability to maintain scoring accuracy on data from a new domain or problem type that was not present in the original training data.

Methodology:

- Zero-Shot Testing: Take the model trained on your primary dataset (e.g., scoring self-explanations in biology) and apply it directly to a new, unseen dataset (e.g., scoring self-explanations in chemistry) without any further training. Compare its performance against manual scores for the new domain.

- Few-Shot Fine-Tuning: If zero-shot performance is inadequate, select a very small number of annotated examples from the new domain (e.g., 10-100 instances). Fine-tune the pre-trained unified model on this small dataset.

- Performance Comparison: Evaluate the few-shot fine-tuned model on the remainder of the new domain's test set. A successful unified model will show a rapid performance improvement with minimal additional data, achieving what is known as few-shot generalization [26] [24].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on unified and automated scoring models, providing benchmarks for expected performance.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Automated Scoring and Data Generation Models

| Model / Method | Task / Evaluation Context | Key Performance Metric | Result | Implication for Data Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-task Fine-tuned LLama 3.2 3B [24] | Scoring multiple learning strategies (self-explanation, think-aloud, etc.) | Outperformed a 20x larger zero-shot model | High performance across diverse rubrics | Enables accurate, scalable automated assessment on consumer-grade hardware. |

| UniCO Framework [26] | Generalization to new, unseen Combinatorial Optimization problems | Few-shot and zero-shot performance | Achieved strong results with minimal fine-tuning | A unified architecture maximizes utility by efficiently adapting to new tasks. |

| Statistical SDG (synthpop) [25] | Replicating correlation structures in synthetic medical data | Propensity Score MSE (pMSE), Correlation Matrix Distance | Consistently outperformed deep learning approaches (GANs, LLMs) | Superior at preserving dataset utility for tabular data; robust for downstream analysis. |

| Deep Learning SDG (ctgan, tvae) [25] | Replicating correlation structures in synthetic medical data | Propensity Score MSE (pMSE), Correlation Matrix Distance | Underperformed compared to statistical methods; required extensive tuning | Potential for complex data, but utility preservation is less reliable without significant resources. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential computational "reagents" and tools for developing and testing unified scoring models.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Unified Scoring Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case in Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained LLMs (e.g., Llama, FLAN-T5) [24] | Provides a powerful base model with broad language understanding, which can be fine-tuned for specific scoring tasks. | Serves as the foundation model for a unified scorer that is subsequently fine-tuned on multiple behavioral rubrics. |

| LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) [24] | An efficient fine-tuning technique that dramatically reduces computational cost and time by updating only a small subset of model parameters. | Enables rapid iteration and fine-tuning of large models (7B+ parameters) on scoring tasks without full parameter retraining. |

| Synthetic Data Generation (SDG) Tools (e.g., synthpop, ctgan) [25] | Generates synthetic datasets that mimic the statistical properties of real data, useful for data augmentation or privacy preservation. | Augmenting a small dataset of expert-scored behaviors to create a larger, more diverse training set for the unified model. |

| XAI Libraries (e.g., SHAP, LIME) | Provides post-hoc interpretability for complex models, explaining the contribution of input features to a final score. | Diagnosing a scoring discrepancy by showing that the model incorrectly weighted a specific keyword in a behavioral response. |

| UniCO-inspired CO-prefix [26] | A architectural component designed to aggregate static problem features, reducing token sequence length and improving training efficiency. | Adapting the unified model to a new behavioral domain by efficiently encoding static domain knowledge (e.g., experimental protocol rules). |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram visualizes the end-to-end workflow for developing, validating, and deploying a unified scoring model, highlighting the critical pathways for ensuring alignment with manual scoring.

Leveraging Deep Learning and Pose Estimation for Enhanced Feature Detection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most suitable pose estimation models for real-time behavioral scoring in a research setting?

The choice of model depends on your specific requirements for accuracy, speed, and deployment environment. Currently, several high-performing models are widely adopted in research.

- YOLO11 Pose: This is a state-of-the-art, single-stage model that simultaneously detects people and estimates their keypoints. It is known for an excellent balance of speed and accuracy, achieving high performance on standard benchmarks like COCO Keypoints. It is ideal for applications requiring real-time processing on various hardware, from cloud GPUs to edge devices [27].

- MediaPipe Pose: Google's framework is highly optimized for real-time performance, even on CPU-only devices and mobile platforms. It uses a two-stage pipeline (person detection followed by keypoint localization) and provides an extensive set of 33 landmarks, including hands and feet, which is beneficial for detailed behavioral analysis [27].

- HRNet (High-Resolution Network): HRNet maintains high-resolution representations throughout the network, unlike models that repeatedly downsample data. This architecture achieves superior accuracy in keypoint localization, especially for small joints, making it suitable for applications where precision is more critical than extreme speed [27].

- OpenPose: A well-known, open-source library for real-time multi-person 2D pose estimation. It uses Part Affinity Fields (PAFs) to associate body parts with individuals and has been extensively used in research, including studies on classifying lifting postures [28].

Table 1: Comparison of Leading Pose Estimation Models

| Model | Key Strengths | Ideal Use Cases | Inference Speed | Keypoint Detail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11 Pose [27] | High accuracy & speed balance, easy training | Real-time applications, custom datasets | Very High (30+ FPS on T4 GPU) | Standard 17 COCO keypoints |

| MediaPipe Pose [27] | Mobile-optimized, runs on CPU, 33 landmarks | Mobile apps, resource-constrained devices | Very High (30+ FPS on CPU) | Comprehensive (body, hands, face) |

| HRNet [27] | State-of-the-art localization accuracy | Detailed movement analysis, biomechanics | High | Standard 17 COCO keypoints |

| OpenPose [28] | Real-time multi-person detection | Multi-subject research, legacy systems | High | Can detect body, hand, facial, and foot keypoints |

FAQ 2: How can we resolve common discrepancies between automated pose estimation scores and manual human observations?

Discrepancies often arise from technical limitations of the model and the inherent subjectivity of human scoring. A systematic approach is needed to diagnose and resolve them.

- Check for Occlusion and Crowding: Models can struggle with occluded body parts or crowded scenes where keypoints are hidden or incorrectly assigned [29]. Review your video data for these scenarios and consider using models robust to occlusions or implementing post-processing logic to handle missing data.

- Verify Training Data Relevance: A model trained on a general dataset (e.g., COCO) may perform poorly on domain-specific postures (e.g., rodent behaviors). Fine-tuning the model on a custom, annotated dataset that closely mirrors your experimental conditions is often necessary to improve agreement [27].

- Calibrate Confidence Thresholds: The model's confidence score for each keypoint detection is crucial. Setting the threshold too low introduces false positives (noisy detections), while setting it too high increases false negatives (missed detections). Manually inspect frames with high disagreement to find the optimal threshold for your application [28].

- Standardize Manual Scoring: Human raters can suffer from biases like the "halo/horn effect" or fatigue [30]. Implement a rigorous manual scoring protocol with clear, objective definitions for each behavior. Training raters together and measuring inter-rater reliability ensures that the "ground truth" data used to validate the automated system is itself consistent and reliable [14].

FAQ 3: What are the critical steps in creating a high-quality dataset for training a custom pose estimation model?

The quality of your dataset is the primary determinant of your model's performance.

- Data Collection: Record videos from multiple angles and under varying lighting conditions that reflect your real experimental setup. This helps the model generalize better. As shown in a lifting posture study, using multiple camera angles (frontal, sagittal, oblique) significantly improves robustness [28].

- Data Annotation: Annotate your images with keypoints and bounding boxes consistently. It is best practice to have multiple annotators (e.g., two radiologists, as in one study) label the data, with a senior expert adjudicating any disagreements to establish a reliable reference standard [31].

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your dataset by applying random transformations to your images. This reduces overfitting and improves model robustness. Common techniques include random rotation (±15°), horizontal flipping, and brightness/contrast adjustment (±20%) [31].

- Data Preprocessing: Implement a pipeline to handle missing keypoints. For example, in a time-series analysis, a window of frames (e.g., 15 frames) can be used to identify and replace missing or outlier keypoint values with the mean coordinates from that window, reducing noise [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performance is Poor on Specific Behavioral Poses

- Problem: The automated system fails to correctly identify keypoints or classify behaviors that are common in your experiment but might be underrepresented in standard training data.

- Solution:

- Isolate Failure Modes: Manually review a sample of videos where the model performed poorly and categorize the errors (e.g., "missed paw keypoints," "confusion between rearing and leaning").

- Targeted Data Collection: Collect more video data focusing specifically on these problematic poses.

- Fine-tune the Model: Use transfer learning to retrain a pre-trained model (e.g., YOLO11 Pose) on your new, targeted dataset. This allows the model to adapt its general knowledge to your specific domain [27].

- Validate: Test the fine-tuned model on a held-out validation set to confirm improvement.

Issue: High Variance Between Automated and Manual Scores Across Different Raters

- Problem: The automated scores agree well with one human rater but poorly with another, indicating inconsistency in the manual "ground truth."

- Solution:

- Conduct Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR) Analysis: Calculate statistical measures of agreement (e.g., Cohen's Kappa, Intra-class Correlation Coefficient) between all human raters. This quantifies the subjectivity in your manual scoring [14].

- Refine the Scoring Protocol: If IRR is low, revisit your behavioral scoring definitions. Make them more objective and operationalized.

- Re-train Raters: Organize sessions where raters score sample videos together and discuss discrepancies until a consensus is reached.

- Adjudicate: Designate a senior researcher to make the final call on ambiguous cases to create a single, consistent ground truth for model validation [31].

Issue: Inconsistent Keypoint Detection in Low-Contrast or Noisy Video

- Problem: The model's detection accuracy drops in poor lighting conditions or when the subject's color blends with the background.

- Solution:

- Preprocessing: Apply image preprocessing techniques to enhance the input. The CSS

contrast()filter function can be used programmatically to adjust the contrast of image frames [32]. - Ensure WCAG Compliance for Visualization: When designing tools for human raters, ensure that the color contrast between text/UI elements and the background meets accessibility standards (e.g., a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1) to prevent display-related errors [20].

- Improve Experimental Setup: Where possible, optimize the physical recording environment with consistent, high-contrast backlighting and ensure the subject stands out from the background.

- Preprocessing: Apply image preprocessing techniques to enhance the input. The CSS

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Classifying Lifting Postures using OpenPose and LSTM

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, provides a clear methodology for classifying discrete actions from pose data [28].

- Aim: To automatically classify lifting postures as "correct" or "incorrect" to assess the risk of low back pain.

- Materials:

- Recording System: Smartphones mounted on tripods.

- Software: OpenPose v1.3 for keypoint extraction.

- Processing Environment: R statistical software for analysis; deep learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow/PyTorch) for LSTM model.

- Procedure:

- Data Collection: Record participants from multiple angles (e.g., 0°, 45°, 90°) and camera heights while they perform correct and incorrect lifting tasks. Video resolution: 1920x1080 at 30 fps [28].

- Keypoint Extraction: Process video frames through OpenPose to obtain 2D coordinates of anatomical landmarks.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate biomechanical features from the keypoints. The study used:

- Joint angles (shoulder, hip, knee), their angular velocities, and accelerations.

- The difference in the y-coordinate between the neck and the mid-hip point to quantify trunk flexion [28].

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing keypoints by using a sliding time window (e.g., 15 frames) and replacing outliers with the window's mean [28].

- Model Training: Train a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model on the sequence of engineered features to perform the classification.

- Validation: Validate the model's accuracy on a separate testing set and an external validation set from public videos.

Lifting Posture Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Framework for Validating Automated Against Manual Scoring

This protocol outlines a generalizable framework for resolving discrepancies, a core concern of your thesis.

- Aim: To systematically identify and minimize differences between automated pose estimation scores and manual behavioral annotations.

- Materials:

- Recorded Behavioral Videos

- Automated Pose Estimation Pipeline (e.g., based on YOLO11 or MediaPipe)

- Annotation Software for manual scoring

- Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python with pandas/scikit-learn)

- Procedure:

- Synchronized Scoring: Run the automated system and have at least two trained human raters score the same set of behavioral videos.

- Data Alignment: Temporally align the automated keypoint sequences/outputs with the manual annotation timelines.

- Discrepancy Analysis: For periods of disagreement, manually review the video to categorize the root cause (e.g., "Occlusion," "Low Model Confidence," "Ambiguous Behavior," "Rater Error").

- Quantitative Comparison: Calculate agreement metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, Cohen's Kappa) between the automated system and the adjudicated manual ground truth.

- Iterative Refinement: Use the findings from the discrepancy analysis to refine the model (e.g., by fine-tuning on problematic cases) or the manual protocol (e.g., by clarifying definitions).

Automated vs. Manual Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Pose Estimation Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Pose Model | Provides a foundational network for feature extraction and keypoint detection; can be used off-the-shelf or fine-tuned. | YOLO11 Pose, MediaPipe, HRNet, OpenPose [27]. |

| Annotation Tool | Software for manually labeling keypoints or behaviors in images/videos to create ground truth data. | CVAT, LabelBox, VGG Image Annotator. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Provides the programming environment to build, train, and deploy pose estimation models. | PyTorch, TensorFlow, Ultralytics HUB [27]. |

| Video Dataset (Custom) | Domain-specific video data critical for fine-tuning models and validating performance in your research context. | Should include multiple angles and lighting conditions [28]. |

| Computational Hardware | Accelerates model training and inference, enabling real-time processing. | NVIDIA GPUs (T4, V100), Edge devices (NVIDIA Jetson) [27]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Used for analyzing results, calculating agreement metrics, and performing significance testing. | R, Python with Pandas/Scikit-learn [28]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Why does my automated scoring system fail to validate against manual ratings?

Problem: Automated behavior scoring results show significant statistical discrepancies when compared to traditional manual scoring by human experts.

Solution:

- Conduct a correlation analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Spearman's rho) between manual and automated scores for key metrics like fluency, originality, and elaboration. One study found a strong correlation for elaboration (rho = 0.76) but a weaker one for originality (rho = 0.21), highlighting that some constructs are harder to automate reliably [15].

- Implement a calibration protocol: Use a subset of expert-scored data to fine-tune the algorithm's thresholds before full deployment. This establishes a baseline agreement.

- Introduce a human validation checkpoint: Designate a strategic point where a researcher manually reviews a random sample of the automated scores (e.g., 10-20%) to monitor for drift and validate consistency [33].

How to address a sudden drop in automated scoring performance?

Problem: The autonomous workflow's performance degrades, leading to increased errors that were not present during initial testing.

Solution:

- Check for data drift: Verify that the input data (e.g., new experimental subjects, altered conditions) still matches the data distribution on which the AI was trained.

- Activate human-in-the-loop oversight: Immediately shift the workflow from a fully autonomous to a hybrid model. Route all scores through a human expert for review and confirmation before they are finalized. This contains errors while the root cause is investigated [33].

- Review error logs and feedback loops: Analyze cases where human oversight corrected the automation. This data is critical for retraining and improving the AI model [34].

How to integrate a new scoring parameter into an existing hybrid workflow?

Problem: Incorporating a new, complex behavioral metric disrupts the existing automated workflow and requires human intervention.

Solution:

- Phased integration via a hybrid model:

- Initial Phase (Human-led): The new parameter is scored entirely manually by researchers.

- Training Phase (Human-in-the-Loop): Collect manual scores and use them as a ground-truth dataset to train an automated scorer. The AI's output is not used operationally but is compared against human scores.

- Deployment Phase (Hybrid): Deploy the automated scorer to handle routine cases, flagging low-confidence or anomalous results for human expert review [34] [33].

- Update governance framework: Document the new parameter, the rationale for the chosen level of automation, and the specific conditions that trigger human intervention [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

At what specific points should a human intervene in an automated behavior scoring workflow?

Strategic human intervention is critical at points involving ambiguity, validation, and high-stakes decisions. Key points include:

| Strategic Point for Intervention | Rationale and Action |

|---|---|

| Low Confidence Scoring | When the AI system's confidence score for a particular data point falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 90%), it should be flagged for human review [33]. |

| Edge Case Identification | Uncommon or novel behaviors not well-represented in the training data should be routed to a human expert for classification [34]. |

| Periodic Validation | Schedule regular, random audits where a human re-scores a subset of the AI's work to continuously validate performance and prevent "automation bias" [35]. |

| Final Decision-Making | In high-stakes scenarios, such as determining a compound's efficacy or toxicity, the final call should be made by a researcher informed by, but not solely reliant on, automated scores [33]. |

How do we balance the trade-off between workflow speed (automation) and scoring accuracy (human)?

The trade-off is managed by adopting a hybrid automation model, not choosing one over the other. The balance is achieved by classifying tasks based on risk and complexity [33]:

- High-Speed, Low-Risk Tasks: Use fully autonomous automation for high-volume, repetitive, and rule-based preprocessing tasks (e.g., data filtering, basic feature extraction) where the cost of error is low.

- Moderate-Risk Tasks: Use human-in-the-loop automation for core scoring activities. The automation performs the initial scoring, but humans intervene for exceptions or low-confidence outcomes.

- High-Risk, Complex Tasks: Use human-led processes for final interpretation, complex pattern recognition, and context-heavy decisions. This ensures accuracy and accountability where it matters most [34].

What is the most common source of discrepancy between automated and manual scoring?

The most common source is the fundamental difference in how humans and algorithms process context and nuance. While automated systems excel at quantifying pre-defined, observable metrics (e.g., frequency, duration), they often struggle with the qualitative, contextual interpretation that human experts bring [15]. For instance, a human can recognize a behavior as a novel, intentional action versus a random, incidental movement, whereas an AI might only count its occurrence. This discrepancy is often most pronounced in scoring constructs like "originality" or "intentionality" [15].

How can we build trust in the automated components of a hybrid workflow?

Trust is built through transparency, performance, and governance [35]:

- Transparency: Choose AI systems that provide explainable outputs or confidence scores, not just a final result.

- Performance: Demonstrate the system's reliability through rigorous, ongoing validation against gold-standard manual scores.

- Governance: Establish clear protocols that define the limits of automation and the process for human oversight, ensuring users know the system has safeguards [33].

Are there compliance considerations for using automated scoring in regulated drug development?

Yes, absolutely. Regulated industries like drug development require strict audit trails and accountability. A human-in-the-loop model is often essential for compliance because it:

- Provides a clear record of human review and approval for critical data points.

- Ensures that a qualified expert is ultimately accountable for the scientific validity of the scored data.

- Aligns with regulatory principles for data integrity and computerised system validation [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol for Validating Automated Behavior Scoring Against Manual Scoring

Objective: To quantitatively assess the agreement between an automated behavior scoring system and manual scoring by trained human experts.

Methodology:

- Data Selection: Select a representative dataset of raw behavioral data (e.g., video files, sensor data) from experiments.

- Blinded Scoring:

- Manual Cohort: Trained human scorers, blinded to the automated system's results, score the entire dataset using a standardized protocol for target metrics (e.g., fluency, originality, elaboration).

- Automated Cohort: The automated AI system scores the same dataset independently.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate inter-rater reliability and correlation coefficients (e.g., Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Spearman's rho) between the manual and automated scores for each metric.

Expected Output: A validation report with correlation coefficients, guiding the level of human oversight required for each metric [15].

Quantitative Data from Comparative Scoring Studies

The table below summarizes findings from a study comparing manual and automated scoring methods, illustrating the variable reliability of automation across different metrics [15].

Table 1: Correlation Between Manual and Automated (OCSAI) Scoring Methods

| Scoring Metric | Manual vs. Automated Correlation (Spearman's rho) | Strength of Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Elaboration | 0.76 | Strong |

| Originality | 0.21 | Weak |

| Fluency | Not strongly correlated with single-item self-belief (rho=0.13) | Weak |

Table 2: Relationship Between Creative Self-Belief and Personality [15]

| Personality Trait | Correlation with Creative Self-Belief (CSB) |

|---|---|

| Openness to Experience | rho = 0.49 |

| Extraversion | rho = 0.20 |

| Neuroticism | rho = -0.20 |

| Agreeableness | rho = 0.14 |

| Conscientiousness | rho = 0.14 |

Workflow Visualization

Hybrid Human-AI Behavior Scoring Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Hybrid Scoring Research Pipeline

| Item | Function in Hybrid Workflow |

|---|---|

| Automated Scoring AI (e.g., OCSAI) | Provides the initial, high-speed quantification of behavioral metrics. Handles the bulk of repetitive scoring tasks [15]. |

| Confidence Scoring Algorithm | A critical software component that flags low-confidence results for human review, enabling intelligent delegation [33]. |

| Human Reviewer Dashboard | An interface that presents flagged data and automated scores to human experts for efficient review and correction [34]. |

| Validation Dataset (Gold Standard) | A benchmark dataset of manually scored behaviors, essential for initial AI training and ongoing validation [15]. |

| Audit Log System | Software that tracks all actions (both automated and human) to ensure compliance, reproducibility, and provide data for error analysis [35]. |

Standardizing Data Protocols to Ensure AI-Ready Inputs

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: AI model performance is degraded due to inconsistent data formats, naming conventions, and units from diverse sources like clinical databases, APIs, and sensor networks [36].

Solution: Implement a structured data standardization protocol at the point of collection [37].

- 1. Identify Inconsistency: Review error logs from your data validation tools or AI model preprocessing stages. Look for failed schema checks or multiple formats for the same data type (e.g., varying date formats: DD/MM/YYYY vs. MM-DD-YYYY).

- 2. Apply Schema Enforcement: Define and enforce a strict schema for all incoming data. This blueprint specifies required fields, allowed data types (string, boolean, timestamp), and value formats [37].

- 3. Standardize Naming and Values:

- Events & Properties: Apply consistent naming conventions (e.g.,

snake_casefor events likeuser_logged_in) [37]. - Value Formatting: Convert values to a standard format (e.g., ISO 8601 for dates, ISO 4217 codes for currency, consistent

true/falsefor Booleans) [37]. - Unit Conversion: Convert all units to a single standard (e.g., kilograms, Celsius) to prevent skewed analytics [37].

- Events & Properties: Apply consistent naming conventions (e.g.,

- 4. Validate and Monitor: Use automated data integration tools to validate data against the schema at collection and during transformation. Continuously monitor data quality reports [37] [36].

Guide 2: Addressing Discrepancies Between Automated and Manual Scoring

Problem: A study comparing an automated pressure mat system with traditional human scoring for the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS) found significant discrepancies across most conditions, with wide limits of agreement [6].

Solution: Calibrate automated systems and establish rigorous validation protocols.

- 1. Diagnose the Discrepancy: Conduct a Bland-Altman analysis to quantify the limits of agreement between the automated and manual methods and identify where the largest differences occur [6].

- 2. Refine the Algorithm: Analyze the raw data from the automated system (e.g., center of force measurements from the pressure mat) against the human-scored errors. Use this analysis to adjust the algorithm's sensitivity and logic for detecting specific error types [6].

- 3. Implement a Hybrid Validation Protocol: For initial deployment and periodic checks, use a dual-scoring approach where a subset of data is scored by both human experts and the automated system to ensure ongoing agreement and identify drift.

- 4. Document the Workflow: Clearly document the capabilities and limitations of the chosen scoring method for clinical or research use [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is data standardization critical for AI in drug development? Data standardization transforms data from various sources into a consistent format, which is essential for building reliable and accurate AI models [36]. It ensures data is comparable and interoperable, which improves trust in the data, enables reliable analytics, reduces manual cleanup, supports governance compliance, and powers downstream automation and integrations [37].

Q2: At which stages of the data pipeline should standardization occur? Standardization should be applied at multiple points [37]:

- At Collection: Use web or mobile SDKs and APIs to ensure data is clean and consistent from the start.

- During Transformation: Clean and align data with defined standards before loading it into a data warehouse.

- In Reverse ETL: Apply standards before sending data from the warehouse to operational tools.

Q3: What are the best practices for building a data standardization process? Best practices include [37]: