Calibrating Automated Behavior Scoring: A Cross-Context Framework for Reliable Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on calibrating automated behavior scoring systems to ensure reliability and reproducibility across diverse experimental contexts.

Calibrating Automated Behavior Scoring: A Cross-Context Framework for Reliable Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on calibrating automated behavior scoring systems to ensure reliability and reproducibility across diverse experimental contexts. It explores the foundational need for robust calibration to detect subtle behavioral phenotypes in preclinical models and translational research. The content covers practical methodological approaches, including self-calibrating software and unified scoring systems, alongside critical troubleshooting strategies for parameter optimization and context-specific challenges. Finally, it establishes a rigorous framework for validation against human scoring and comparative analysis of system performance, aiming to standardize practices, reduce bias, and enhance the translational validity of behavioral data in drug discovery and neurological disorder research.

Why Calibration is Critical: The Foundation of Reliable Automated Behavioral Data

The Problem of Context-Dependent Variability in Automated Scoring

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is context-dependent variability in automated behavior scoring, and why is it a problem in drug development research?

Context-dependent variability refers to the phenomenon where an automated scoring system's performance and the measured behaviors change significantly when the experimental conditions, such as the subject's environment, timing, or equipment, are altered. This is a critical problem because it challenges the reliability and reproducibility of data. In drug development, a behavioral test score used to assess a drug's efficacy in one lab (e.g., a tilt aftereffect measurement) might not be comparable to a score from another lab with a different setup. This variability can obscure true treatment effects, lead to inaccurate conclusions about a drug candidate's potential, and ultimately waste valuable resources [1] [2].

Q2: My automated scoring system works perfectly in my lab, but other researchers cannot replicate my results. What could be wrong?

This is a classic sign of context-dependent variability. The issue likely lies in differences between your experimental context and theirs. Key factors to investigate include:

- Environmental Cues: Differences in lighting, background noise, or time of day when experiments are run can influence subject behavior and sensor readings [1].

- Equipment and Software: Even the same model of camera or analysis software with different version numbers or settings (e.g., resolution, frame rate) can produce different raw data.

- Subject Handling and Acclimation: Variations in how subjects are transported, handled, or acclimated to the testing apparatus can induce different stress levels, thereby altering behavioral outcomes.

- Data Pre-processing: Slight differences in how raw data is filtered, normalized, or segmented before it reaches the scoring algorithm can have a major impact.

Q3: How can I calibrate my automated scoring system to ensure it performs reliably across different experimental contexts?

Calibration requires a structured, multi-step process focused on validating the system's performance across a range of expected conditions. The following troubleshooting guide provides a detailed methodology.

Troubleshooting Guide: System Calibration for Cross-Context Reliability

This guide walks you through a systematic process to diagnose, mitigate, and validate your automated scoring system against context-dependent variability.

Phase 1: Understanding and Isolating the Problem

The first step is to ensure you truly understand the scope of the variability and can reproduce the issue under controlled conditions.

Step 1: Gather Information and Reproduce the Issue

- Document Everything: Create a detailed log of all parameters from the original experiment where the system worked well and the new experiment where it is failing. This includes environmental conditions, hardware specifications, software versions, and subject metadata.

- Reproduce the Discrepancy: In your lab, intentionally run experiments that mimic the two different contexts (e.g., change the lighting conditions or use a different camera). Confirm that you can observe the same scoring variability internally.

Step 2: Isolate the Root Cause

- Change One Thing at a Time: Systematically alter single variables from your documented list while keeping all others constant. For example, change only the camera model, then reset it and change only the background color of the testing arena [3].

- Compare to a Working Baseline: After each change, compare the new automated scores against the "gold standard" baseline, which is often manual scoring by human experts. This will help you identify which specific variable is the primary source of the variability.

Phase 2: Implementing a Calibration Protocol

Once key variables are identified, implement a formal calibration protocol.

Step 3: Establish a Reference Dataset

- Create a curated, shared dataset of video or sensor recordings that spans the range of expected experimental conditions and behaviors. This dataset must be meticulously scored by multiple human experts to establish a ground truth. This dataset will serve as your system's calibration benchmark.

Step 4: Re-calibrate Algorithm Parameters

- Use the reference dataset to retrain or fine-tune your scoring algorithm's parameters. The goal is to make it robust to the isolated contextual variables. This often involves adjusting thresholds or incorporating context-invariant features.

Step 5: Validate with a Robustness Assessment

- Test the re-calibrated system on a completely new set of data from a different context (e.g., a collaborator's lab). Do not use this data in the calibration step. The table below outlines key assessment criteria based on model evaluation frameworks [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment Criteria for Calibrated Scoring Systems

| Assessment Area | Metric | Target Value (Example) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biology/Behavior | Correlation with Expert Scores (e.g., Pearson's r) | > 0.9 | Ensures the automated score maintains biological relevance and agrees with expert judgment. |

| Implementation | Sensitivity Analysis | < 10% output change | Measures how much the score changes with small perturbations in input data or parameters. |

| Simulation Results | Accuracy & F1-Score across Contexts | > 95% | Evaluates classification performance (e.g., behavior present/absent) in multiple environments. |

| Robustness of Results | Coefficient of Variation (CV) across Contexts | < 5% | Quantifies the consistency of scores when the same behavior is measured under different conditions. |

Phase 3: Technical Validation and Documentation

Step 6: Perform Technical Quality Checks

- Code Review: Check the algorithm's code for errors and ensure it adheres to best practices for reproducibility [2].

- Unit Testing: Implement tests to verify that individual components of your scoring pipeline (e.g., a function that extracts movement speed) produce the expected output for a given input.

Step 7: Document the Calibration

- Create a comprehensive document detailing the reference dataset, the final algorithm parameters, the validation results, and the acceptable range of contextual variables. This is your lab's standard operating procedure (SOP) for the scoring system.

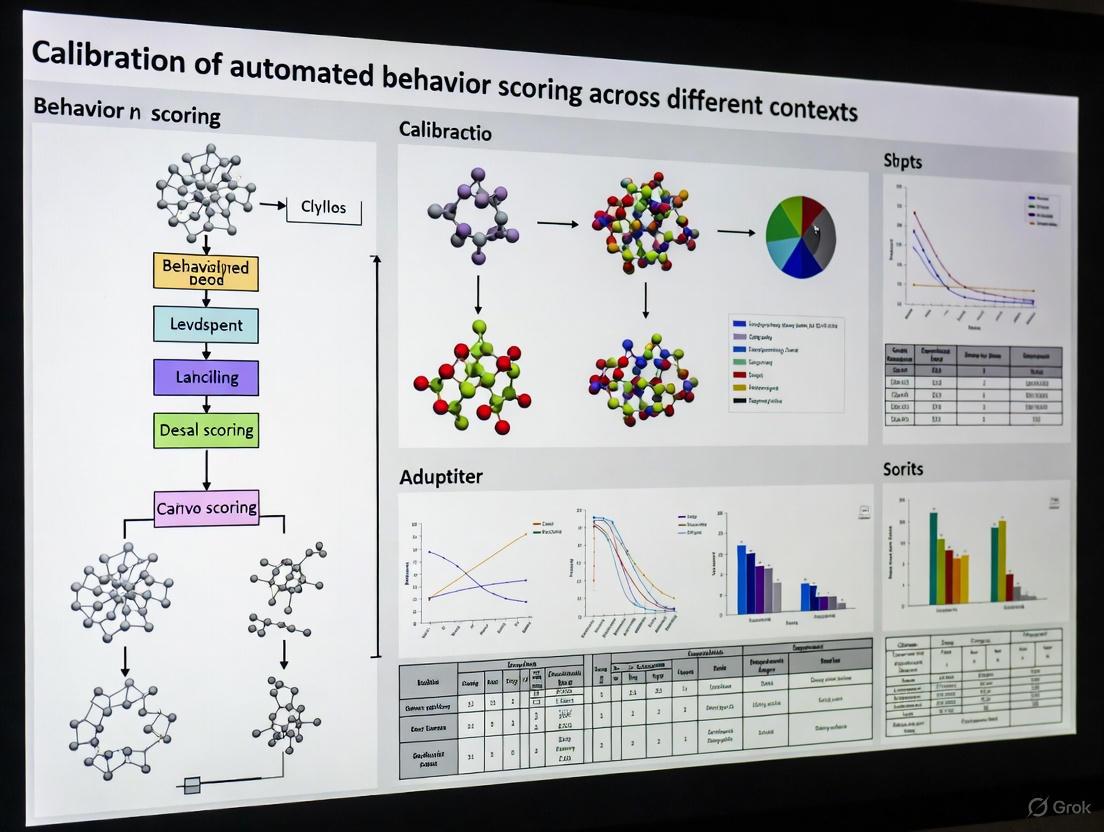

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for troubleshooting and calibration:

Experimental Protocol: Cross-Context Validation for an Automated Scoring System

Aim: To empirically determine the sensitivity of an automated behavior scoring system to specific contextual variables and to establish a validated operating range.

1. Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function / Description | Critical Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Behavior Dataset | A ground-truth set of video/sensor recordings used to calibrate and validate the automated scorer. | Must be scored by multiple human experts to ensure inter-rater reliability. Should cover diverse behaviors and contexts. |

| Automated Scoring Software | The algorithm or software platform used to quantify the behavior of interest. | Version control is critical. Note all parameters and settings. |

| Data Acquisition System | Hardware for capturing raw data (e.g., high-speed camera, microphone, accelerometer). | Document model, serial number (if possible), and all settings (e.g., resolution, sampling rate). |

| Testing Arenas/Apparatus | The environment in which the subject's behavior is observed. | Standardize size, shape, and material. Document any changes for context manipulation. |

| Calibration Validation Suite | A set of scripts to run the automated scorer on the reference dataset and calculate performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, CV). | Custom-built for your specific assay. Outputs should align with Table 1 metrics. |

2. Methodology

Step 1: Baseline Acquisition.

- Set up the ideal, standardized context (Context A). Record a set of behavioral sessions.

- Process the data with the automated scoring system to establish your baseline scores.

Step 2: Context Manipulation.

- One at a time, introduce a single contextual variable to create a new context (Context B, C, etc.). Examples include:

- Environmental: Reduce ambient light level by 50%.

- Hardware: Use a different camera model or lens.

- Software: Apply a different video compression format.

- For each new context, record the same subjects or a new cohort from the same population.

Step 3: Data Analysis and Comparison.

- Run the automated scoring system on all data from all contexts.

- For each subject/recording, compare the automated score from the altered context to both the baseline automated score and the human expert score for that recording.

- Calculate the performance metrics from Table 1 for each context.

Step 4: Interpretation and Definition of Valid Range.

- If the performance metrics for a given context (e.g., low light) fall outside your pre-defined acceptance thresholds (e.g., Accuracy < 95%), that context is outside the valid range for your system.

- The valid operational range is defined by the set of all contextual variables for which the system meets all performance criteria.

The logical relationship between the system's core components and the validation process is shown below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes of low accuracy in my automated behavior scoring system? Low accuracy often stems from improper motion threshold calibration, inconsistent lighting conditions between training and testing environments, or high-frequency noise in the raw data acquisition. First, verify your motion detection sensitivity and ensure lighting is consistent. If the problem persists, examine your raw data streams for electrical noise or sampling rate inconsistencies [4].

Q2: How can I ensure my visualized data and scoring outputs are accessible to all team members, including those with color vision deficiencies? Adhere to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) for color contrast. For all text in diagrams, scores, or UI elements, ensure a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 against the background. Use tools like WebAIM's Color Contrast Checker to validate your color pairs. Avoid conveying information by color alone [5] [6].

Q3: My system's behavioral scores are not reproducible across different experimental setups. What should I check? This indicates a potential lack of contextual calibration. Begin by auditing your "Research Reagent Solutions" (e.g., anesthetic doses, sensor types) for consistency. Implement a unified scoring protocol that uses standardized positive and negative control stimuli to normalize scores across different hardware or animal models, creating a common baseline [7] [8].

Q4: What does the 'unified' in Unified Behavioral Scores mean? A 'Unified' score integrates data from multiple modalities (e.g., velocity, force, spectral patterns) and normalizes them against a common scale using validated controls. This process allows for the direct comparison of behavioral outcomes across different drugs, species, or experimental contexts, moving beyond simple, context-dependent motion counts [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Motion Detection

This problem manifests as the system failing to detect similar movements under different conditions or producing erratic motion counts.

Step 1: Verify Pre-processing and Thresholds Check the raw input data from your motion sensor for saturation or excessive noise. Adjust the motion detection algorithm's sensitivity threshold. A threshold that is too high will miss subtle movements, while one that is too low will capture noise as false positives.

Step 2: Calibrate with Positive Controls Use a standardized positive control, such as a mechanical vibrator at a known frequency and amplitude, to simulate a consistent motion. Record the system's output across multiple trials and adjust the detection threshold until the score is consistently accurate and precise.

Step 3: Contextual Re-Calibration If inconsistency persists across different environments (e.g., new testing room, different cage material), you must perform a full contextual recalibration. This involves running a suite of control stimuli (both positive and negative) in the new context to establish a new baseline for your unified scores.

Issue: Poor Generalization of Scores to New Drug Classes

The behavioral scoring model works well for established drugs but fails to accurately score behaviors for new therapeutic compounds.

Step 1: Analyze Model Training Data Review the diversity of compounds and behaviors in your model's training set. The model may be over-fitted to a narrow range of pharmacological mechanisms.

Step 2: Employ Active Learning for Data Collection Instead of collecting a large, random dataset, use an active learning framework like BATCHIE. This approach uses a Bayesian model to intelligently select the most informative new drug experiments to run, optimizing the dataset to improve model generalization efficiently [8].

- Procedure:

- Train an initial model on your existing data.

- The model calculates an "informativeness" score for potential new drug experiments.

- Conduct a small batch of the highest-priority experiments.

- Update the model with the new results.

- Repeat until model performance meets the desired accuracy across diverse drug classes.

- Procedure:

Step 3: Validate with Orthogonal Assays Correlate the new unified behavioral scores with results from other assays to ensure the scores reflect the intended biology and not an artifact of the model.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Protocol: Active Learning for Score Model Enhancement

This protocol is adapted from Bayesian active learning principles used in large-scale drug screening [8].

- Initialization: Start with an initial, small dataset of drug-behavior profiles ( D_{initial} ).

- Model Training: Train a Bayesian predictive model ( M ) on ( D_{initial} ). This model should output both a prediction and a measure of uncertainty.

- Batch Design:

- For a wide range of candidate drugs ( C ), use the PDBAL (Probabilistic Diameter-based Active Learning) criterion to calculate how much information each experiment is expected to provide.

- Select the top

kmost informative candidates to form a new batch ( B ).

- Experiment Execution: Conduct behavioral scoring experiments for all drug candidates in batch ( B ).

- Model Update: Add the new data ( B ) to the training set, updating the model to ( M' ).

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until the model's performance plateaus or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: WCAG 2.1 Color Contrast Requirements for Data Visualization [5] [6]

| Content Type | Level AA (Minimum) | Level AAA (Enhanced) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Body Text | 4.5:1 | 7:1 |

| Large Text (≥18pt or ≥14pt bold) | 3:1 | 4.5:1 |

| User Interface Components & Graphical Objects | 3:1 | Not Defined |

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Design Strategies for Behavioral Phenotyping

| Feature | Traditional Fixed Design | Active Learning Design (e.g., BATCHIE) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | Static, predetermined | Dynamic, sequential, and adaptive |

| Model Focus | Post-hoc prediction | Continuous improvement during data acquisition |

| Experimental Efficiency | Lower; may miss key data points | Higher; targets most informative experiments |

| Scalability | Poor for large search spaces | Excellent for exploring large parameter spaces |

| Best Use Case | Well-established, narrow research questions | Novel drug screening and model generalization |

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Automated Behavioral Scoring Calibration

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Standardized Positive Control Stimuli | A device (e.g., calibrated vibrator) to generate a reproducible motion signal for threshold calibration and system validation. |

| Negative Control Environment | A chamber or setup designed to minimize external vibrations and electromagnetic interference to establish a baseline "no motion" signal. |

| Reference Pharmacological Agents | A set of well-characterized drugs (e.g., stimulants, sedatives) with known behavioral profiles used to normalize and validate unified behavioral scores. |

| Bayesian Active Learning Platform | Software (e.g., BATCHIE) that uses probabilistic models to design optimal sequential experiments, maximizing the information gained from each trial [8]. |

| Color Contrast Validator | A tool (e.g., WebAIM's Color Contrast Checker) to ensure all visual outputs meet accessibility standards, guaranteeing legibility for all researchers [6]. |

Visualization: Calibration Workflows

Behavioral Score Calibration & Validation Workflow

Active Learning for Model Generalization

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Automated Behavior Scoring

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our automated freezing software works perfectly in our lab but fails to produce comparable results in a collaborator's lab. What could be the cause? This is a common issue often stemming from contextual bias introduced by rigorous within-lab standardization. While standardization reduces noise within a single lab, it can make your results idiosyncratic to your specific conditions (e.g., lighting, background noise, cage type, or animal strain) [9] [10]. This is a major threat to reproducibility in preclinical research. The solution is not just better software calibration, but a better experimental design that incorporates biological variation.

Q2: How can we calibrate our automated scoring software to be more robust across different experimental setups? Robust calibration requires a representative sample of the variation you expect to encounter. Use a calibration video set recorded under different conditions you plan to use (e.g., different rooms, camera angles, lighting, or animal coats) [11]. Manually score a brief segment (e.g., 2 minutes) from several videos in this set and let the software use this data to automatically find the optimal detection parameters. This teaches the software to recognize the target behavior across varied contexts.

Q3: What is the minimum manual scoring required to reliably calibrate an automated system like Phobos? Validation studies for software like Phobos suggest that a single 2-minute manual quantification of a reference video can be sufficient for the software to self-calibrate and achieve good performance, provided the video is representative of your experimental conditions. The software typically warns you if the manual scoring represents less than 10% or more than 90% of the total video time, as these extremes can compromise calibration reliability [11].

Q4: We study social interactions in groups, not just individual animals. How can we ensure directed social behaviors are scored correctly? Scoring directed social interactions in groups is a complex challenge. Specialized tools like the vassi Python package are designed for this purpose. They allow for the classification of directed social interactions (who did what to whom) within a group setting and include verification tools to review and correct behavioral detections, which is crucial for subtle or continuous behaviors [12].

Q5: Why would increasing our sample size sometimes lead to less accurate effect size predictions? This counterintuitive result can occur in highly standardized single-laboratory studies. A larger sample size in a homogenous environment increases the precision of an estimate that may be locally accurate but globally inaccurate. It reinforces a result that is specific to your lab's unique conditions but not generalizable to other populations or settings. Multi-laboratory designs are more effective for achieving accurate and generalizable effect size estimates [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Reproducibility Between Labs

Problem: Results from an automated behavioral assay (e.g., fear conditioning) cannot be replicated in a different laboratory, despite using the same protocol and animal strain.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual Bias from Over-Standardization | Audit and compare all environmental factors between labs (e.g., light cycle, housing density, background noise, vendor substrain). | Adopt a multi-laboratory study design. If that's not possible, introduce controlled heterogenization within your lab (e.g., using multiple animal litters, testing across different times of day, or using multiple breeding cages) [10]. |

| Inadequate Software Calibration | Export the raw tracking data from both labs and compare the movement metrics. Test if your software, calibrated on Lab A's data, fails on Lab B's videos. | Perform a cross-context calibration. Use a calibration video set that includes data from both laboratory environments to find a robust parameter set that works universally [11]. |

| Unaccounted G x E (Gene-by-Environment) Interactions | Review the genetic background of the animals and the specific environmental differences between the two labs. | Acknowledge this biological reality in experimental planning. Use multi-laboratory designs to explicitly account for and estimate the size of these interactions, making your findings more generalizable [9]. |

Issue: High Discrepancy Between Automated and Manual Scoring

Problem: Your automated system (e.g., Phobos, EthoVision, VideoFreeze) is consistently over-estimating or under-estimating a behavior like freezing compared to a human observer.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Detection Threshold | Manually score a short (2-min) reference video. Have the software analyze the same video with multiple parameter combinations and compare the outputs. | Use the software's self-calibration feature. Input your manual scoring of the reference video to allow the software to automatically determine the optimal freezing threshold and minimum freezing duration [11]. |

| Poor Video Quality or Contrast | Check the video resolution, frame rate, and contrast between the animal and the background. | Ensure videos meet minimum requirements (e.g., 384x288 pixels, 5 fps). Improve lighting and use a uniform, high-contrast background where the animal is clearly visible [11]. |

| Software Not Validated for Your Specific Setup | Inquire whether the software has been validated in the literature for your specific species, strain, and experimental context. | If using a custom or newer tool like vassi, perform your own validation. Manually score a subset of your videos and compare them to the software's output to establish a correlation and identify any systematic biases [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Cross-Context Calibration of Automated Scoring Software

This protocol is designed to calibrate automated behavior scoring tools (e.g., Phobos, VideoFreeze) to perform robustly across different experimental contexts, enhancing reproducibility.

Create a Heterogeneous Video Set: Compile a set of short video recordings (e.g., 10-15 videos, each 2-5 minutes long) that represent the full range of conditions you expect in your experiments. This should include variations in:

- Laboratory environment (if a multi-lab study)

- Camera angle (horizontal, vertical, diagonal)

- Lighting conditions

- Animal coat color (if using multiple strains)

- Background appearance [11]

Generate Ground Truth Manual Scores: Have two or more trained observers, who are blinded to the experimental conditions, manually score the behavior of interest in each video. Use a standardized ethogram to define the behavior. Calculate the inter-observer reliability to ensure scoring consistency.

Software Calibration: Input the manually scored videos into the automated software. For self-calibrating software like Phobos, it will use this data to automatically determine the best parameters. For other software, systematically test different parameter combinations (e.g., immobility threshold, scaling, minimum duration) to find the set that yields the highest agreement with the manual scores across the entire heterogeneous video set [11].

Validation: Test the final, calibrated software parameters on a completely new set of validation videos that were not used in the calibration step. Compare the automated output to manual scores of these new videos to confirm the system's accuracy and generalizability.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Multi-Laboratory Study Design

This protocol outlines the steps for designing a preclinical study across multiple laboratories to improve the external validity and reproducibility of your findings.

Laboratory Selection: Identify 2-4 independent laboratories to participate in the study. The goal is to capture meaningful biological and environmental variation, not to achieve identical conditions.

Core Protocol Harmonization: Collaboratively develop a core experimental protocol that defines the essential, non-negotiable elements of the study (e.g., animal strain, sex, age, key outcome measures, statistical analysis plan).

Controlled Heterogenization: Allow for systematic variation in certain environmental factors that are often standardized but known to differ between labs. This can include:

- Housing conditions (cage type, bedding material)

- Time of day for testing

- Diet

- Personnel performing the experiments

- Specific brand of equipment [10]

Data Collection and Centralized Analysis: Each laboratory conducts the experiment according to the core protocol while maintaining its local "heterogenized" conditions. Raw data and video recordings are sent to a central analysis team.

Statistical Analysis: The central team analyzes the combined data using a statistical model (e.g., a mixed model) that includes "laboratory" as a random effect. This allows you to estimate the treatment effect while accounting for the variation introduced by different labs. The presence of a significant treatment-by-laboratory interaction indicates that the treatment effect depends on the specific lab context [10].

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Diagram 1: Cross-Context Calibration Workflow

Diagram 2: Multi-Lab vs. Single-Lab Design Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Tool | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Software Solutions | Phobos | A freely available, self-calibrating software for measuring freezing behavior. It uses a brief manual quantification to automatically adjust its detection parameters, reducing inter-user variability and cost [11]. |

| vassi | A Python package for verifiable, automated scoring of social interactions in animal groups. It is designed for complex settings, including large groups, and allows for the detection of directed interactions and verification of edge cases [12]. | |

| Commercial Suites (e.g., VideoFreeze, EthoVision, AnyMaze) | Widely used commercial platforms for automated behavioral tracking and analysis. They often require manual parameter tuning by the researcher and can be expensive [11]. | |

| Calibration Materials | Heterogeneous Video Set | A collection of videos capturing the range of experimental conditions (labs, angles, lighting). Serves as the ground truth for calibrating and validating automated software to ensure cross-context reliability [11]. |

| Experimental Design Aids | Multi-Laboratory Framework | A study design where the same experiment is conducted in 2-4 different labs. It is not for increasing sample size, but for incorporating biological and environmental variation, dramatically improving the reproducibility and generalizability of preclinical findings [10]. |

| Controlled Heterogenization | The intentional introduction of variation within a single lab study (e.g., multiple litters, testing times). This simple step can mimic some benefits of a multi-lab study by making the experimental sample more representative [10]. |

Why is our automated system reporting different activity levels for male and female C57BL/6 mice, and should we be concerned?

This is an expected finding, not necessarily a system error. A key study using an automated home-cage system (PhenoTyper) observed that female C57BL/6 mice were consistently more active than males, while males showed a stronger anticipatory increase in activity before the light phase turned on [13]. These differences were robust, appearing across different ages and genetic backgrounds, highlighting a fundamental biological variation. The concern is not the difference itself, but its potential to confound other measurements. The same study found that in a spatial learning task, the higher activity of females led them to make more responses and earn more rewards, even though no actual sex difference in learning accuracy existed [13]. This demonstrates that activity differences can be misinterpreted as cognitive differences if not properly calibrated for.

We study social behavior in prairie voles. Can we trust automated scoring for our partner preference tests (PPTs)?

Yes, but the choice of automated metric is critical. A validation study compared manual scoring with two automated methods: "social proximity" and "immobile social contact." The results showed that "immobile social contact" was highly correlated with manually scored "huddling" (R = 0.99), which is the gold-standard indicator of a partner preference in voles [14]. While "social proximity" also correlated well with manual scoring (R > 0.90), it was less sensitive, failing to detect a significant partner preference in one out of four test scenarios [14]. Therefore, systems must be calibrated to recognize species-specific, immobile affiliative contact to ensure data accurately reflects the biological phenomenon of interest.

Our automated pain behavior analysis seems inaccurate. How can we validate and improve its performance?

Inaccurate automated pain scoring is often addressed by implementing a two-stage pipeline that combines deep learning (DL) with traditional behavioral algorithms [15].

1. Pose Estimation: Use markerless tracking tools like DeepLabCut or SLEAP to identify and track key body parts (e.g., paws, ears, nose) from video recordings. This generates precise data on the animal's posture and movement [15].

2. Behavior Classification: Extract meaningful behavioral information from the pose data. For well-defined behaviors like paw flicking, traditional algorithms may suffice. For more complex or nuanced behaviors (e.g., grooming, shaking), machine learning (ML) classifiers like Random Forest or Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are more effective. One validated pipeline uses pose data to generate a "pain score" by reducing feature dimensionality and feeding it into an SVM [15].

To improve your system, ensure your DL models are trained on a diverse dataset that includes variations in animal strain, sex, and baseline activity levels to improve generalizability and accuracy.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Calibration Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| System fails to detect specific behaviors (e.g., huddling). | Using an incorrect behavioral metric (e.g., "social proximity" instead of "immobile social contact"). | Validate the automated metric against manual scoring for your specific behavior and species. Recalibrate software parameters to focus on the correct behavioral signature [14]. |

| Behavioral data shows high variance or bias across strains or sexes. | Underlying biological differences in activity or strategy are not accounted for. | Establish separate baseline activity profiles for each strain and sex. Use controlled experiments to dissociate motor activity from cognitive processes [13]. |

| Inconsistent results when deploying a new model or tool. | The model was trained on a dataset lacking diversity in animal populations. | Retrain ML/DL models (e.g., DeepLabCut, SLEAP) using data that includes all relevant strains and sexes to improve generalizability [15]. |

| Automated score does not match manual human scoring. | The definition of the behavioral state may differ between the software and the human scorer. | Conduct a rigorous correlation study between the automated output and manual scoring. Use the results to refine the automated behavioral classification criteria [14]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Behavioral Calibration |

|---|---|

| PhenoTyper (or similar home-cage system) | Automated home-cage system for assessing spontaneous behavior with minimal handling stress, ideal for establishing baseline activity levels [13]. |

| Noldus EthoVision | A video-tracking software suite capable of measuring "social proximity," useful for basic automated analysis when validated for the specific behavior [14]. |

| Clever Sys Inc. SocialScan | Automated software capable of detecting "immobile social contact," essential for accurately scoring affiliative behaviors like huddling in social bonding tests [14]. |

| DeepLabCut / SLEAP | Open-source, deep learning-based tools for markerless pose estimation. The foundation for training custom models to track specific body parts across species and behaviors [15]. |

| C57BL/6 & Other Mouse Strains | Common laboratory strains used to quantify and control for genetic background effects on behavior, which is crucial for system calibration [13]. |

| Prairie Voles (Microtus ochrogaster) | A model organism for studying social monogamy and attachment. Their behavior necessitates specific calibration for "immobile social contact" [14]. |

Experimental Workflow for System Calibration

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for calibrating automated behavior scoring systems, ensuring they accurately capture biology across different experimental conditions.

The Logic of Behavioral Metric Selection

Choosing the correct automated metric is paramount, as an incorrect choice can lead to biologically invalid conclusions. The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting a metric in a social behavior assay.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: My automated scoring system shows high accuracy (>95%) on my training data, but when I apply it to a new batch of animals from a different supplier, the results are completely different and don't match my manual observations. What went wrong?

- A: This is a classic sign of an uncalibrated system suffering from context shift. High accuracy on training data often indicates overfitting, not generalizability. The system's internal decision boundaries were optimized for the specific features (e.g., fur color, size, baseline activity) of your original animal cohort. A new supplier introduces new feature distributions, causing the model to overestimate or underestimate behaviors. You must perform a calibration and validation step on a representative sample from the new supplier before full deployment.

Q: I am testing a new compound for anxiolytic effects. My automated system fails to detect a significant reduction in anxiety-like behavior, but my manual scorer insists the effect is obvious. What could explain this discrepancy?

- A: Your system may be making a Type II error (false negative). The system's pre-defined thresholds for "anxiety-like behavior" (e.g., time in open arms of a maze) might be too strict or based on features not sensitive to the specific pharmacological profile of your new compound. The model is underestimating the treatment effect. Re-calibrate the system by reviewing video clips where manual and automated scores disagree, and adjust the feature detection algorithms or classification thresholds accordingly.

Q: My system identifies a "statistically significant" increase in social interaction in a transgenic mouse model. However, when we follow up with more nuanced experiments, we cannot replicate the finding. What risk did we encounter?

- A: You likely encountered a Type I error (false positive). An uncalibrated system can be prone to overestimation due to noise or confounding variables (e.g., increased general locomotion misclassified as social investigation). Without proper calibration against a ground truth dataset that includes various negative controls, the system may identify patterns that are not biologically real. Always validate a positive finding with a secondary, orthogonal behavioral assay.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Systematic Overestimation of a Behavioral Phenotype

- Symptoms: The automated system consistently scores a behavior higher than manual raters across multiple experiments. Positive controls show exaggerated effects.

- Diagnosis: The classification threshold for the behavior is likely set too low, causing non-specific movements or noise to be classified as the target behavior.

- Solution:

- Generate a Ground Truth Dataset: Manually score a new, balanced dataset (including both positive and negative examples).

- Plot a Precision-Recall Curve: Compare automated scores against the manual ground truth.

- Re-calibrate Threshold: Adjust the decision threshold to maximize the F1-score or to align with a pre-defined acceptable false discovery rate.

- Validate: Test the re-calibrated system on a held-out validation dataset.

Issue: Systematic Underestimation of a Behavioral Phenotype

- Symptoms: The system fails to detect behaviors that are clear to human observers. Treatment effects are consistently smaller than expected.

- Diagnosis: The model's feature extraction may be insufficient, or the classification threshold is too high, excluding true positive instances.

- Solution:

- Error Analysis: Review false negative instances to identify common features the model is missing.

- Feature Engineering: Add new, more sensitive features to the model (e.g., velocity, trajectory curvature, body part angle).

- Retrain and Re-calibrate: Use the expanded feature set to retrain the model, then calibrate the new threshold as described above.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Model Calibration on Error Rates in a Social Behavior Assay

| Condition | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Effective Type I Error | Effective Type II Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncalibrated Model | 88% | 0.65 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 35% (High Overestimation) | 5% |

| Calibrated Model | 92% | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 9% | 7% |

Table 2: Context-Dependent Performance Shift in an Anxiety Assay (Time in Open Arm)

| Animal Cohort | Manual Scoring (sec) | Uncalibrated System (sec) | Calibrated System (sec) | Error Type Indicated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort A (Training) | 45.2 ± 5.1 | 44.8 ± 6.2 | 45.1 ± 5.3 | None |

| Cohort B (Different Supplier) | 48.5 ± 4.8 | 38.1 ± 7.5 | 48.2 ± 5.0 | Underestimation (Type II) |

| Cohort C (Different Housing) | 41.1 ± 6.2 | 52.3 ± 5.9 | 41.5 ± 6.1 | Overestimation (Type I) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cross-Context Validation for Model Calibration

- Objective: To assess and mitigate the risks of overestimation, underestimation, and Type I/II errors when applying an automated scoring system to a new experimental context.

- Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

- Methodology:

- Ground Truth Establishment: A human expert, blinded to the experimental conditions, manually scores a representative subset of videos (e.g., n=20 per experimental group/context) using a predefined ethogram.

- Baseline Performance: Run the automated system on this ground truth dataset to establish baseline performance metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score).

- Bias Detection: Analyze the confusion matrix and prediction distributions to identify systematic overestimation or underestimation.

- Threshold Calibration: Use the

Platt scalingorIsotonic regressionmethod on the model's output scores to calibrate the prediction probabilities, aligning them with the empirical likelihoods observed in the ground truth data. - Validation: Apply the calibrated model to a completely new, held-out test set from the same new context. Compare the calibrated outputs against a fresh manual scoring of this test set to confirm the reduction in error rates.

Protocol 2: Orthogonal Validation to Confirm True Positives

- Objective: To rule out Type I errors (false positives) after an automated system detects a significant effect.

- Methodology:

- Following a significant result from the primary automated assay (e.g., Open Field), subject the same animals to a secondary, orthogonal behavioral test (e.g., Light-Dark Box for anxiety, or a three-chamber test for social behavior).

- Score the secondary test using a different methodology—ideally manually or with a different, independently calibrated automated system.

- A positive correlation between the effect sizes measured in the primary (calibrated automated) and secondary (orthogonal) assays confirms the finding is not a Type I error.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Calibration Workflow for Reliable Scoring

Diagram 2: Type I & II Errors in Hypothesis Testing

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for Behavioral Calibration

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| DeepLabCut | A markerless pose estimation tool. Provides high-fidelity, frame-by-frame coordinates of animal body parts, which are the fundamental features for any subsequent behavior classification. |

| SIMBA | A toolbox for end-to-end behavioral analysis. Used to build machine learning classifiers from pose estimation data and perform the critical threshold calibration discussed in the protocols. |

| EthoVision XT | A commercial video tracking system. Provides a integrated suite for data acquisition, tracking, and analysis, often including built-in tools for zone-based and classification-based behavioral scoring. |

| BORIS | A free, open-source event-logging software. Ideal for creating the essential "ground truth" dataset through detailed manual annotation, which is the gold standard for model training and calibration. |

| Scikit-learn | A Python machine learning library. Used for implementing calibration algorithms (Platt Scaling, Isotonic Regression), calculating performance metrics, and generating confusion matrices and precision-recall curves. |

| Positive/Negative Control Compounds | Pharmacological agents with known, robust effects (e.g., Caffeine for locomotion, Diazepam for anxiety). Critical for validating that the calibrated system can accurately detect expected behavioral changes. |

Implementing Calibration: From Self-Calibrating Software to Unified Scoring Frameworks

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My automated scoring system has a low correlation with manual scores. What are the primary parameters I should adjust to improve calibration? A1: The most common parameters to adjust are the freezing threshold (the number of non-overlapping pixels between frames below which the animal is considered freezing) and the minimum freezing duration (the shortest period a candidate event must last to be counted as freezing). Automated systems like Phobos systematically test various combinations of these parameters against a short manual scoring segment to find the optimal values for your specific setup [11].

Q2: What are the most common sources of error when capturing video for automated analysis? A2: Common errors include [16]:

- Poor Camera Stability: Shaky, handheld footage. Always use a tripod.

- Incorrect Camera Angle: For team sports, an elevated angle is needed. For biomechanical analysis, tighter side or front/back angles are required.

- Insufficient Video Quality: Low resolution or frame rate can hinder the software's ability to detect movement accurately. A minimum resolution of 384x288 and 5 frames per second is often suggested [11].

Q3: How can I validate that my automated segmentation or scoring pipeline is working correctly? A3: Validation should occur on multiple levels [17]:

- Algorithm Inspection: During development, manually inspect the algorithm's output.

- Robustness Testing: Test the algorithm under various conditions (e.g., different lighting, noise levels).

- Benchmarking Against Manual Results: Validate the final algorithm's output against results from manually segmented or scored images/videos. The key is supervised output data [17].

Q4: What software tools are available for implementing a video analysis pipeline? A4: Several tools exist, from specialized commercial packages to customizable code-based solutions.

- R and Python: Environments like R (with

EBImage,raster, andspatstatpackages) or Python are highly customizable for tasks like image segmentation and map algebra operations [17]. - MATLAB: Used for tools like the self-calibrating Phobos software for freezing behavior [11].

- Specialized Software: Packages like Nacsport (for sports analysis) or Vernier Video Analysis (for educational labs) offer dedicated workflows [18] [16].

Q5: Why is camera calibration critical for accurate measurement in video analysis? A5: Camera calibration determines the camera's intrinsic (e.g., focal length, lens distortion) and extrinsic (position and orientation) parameters. Without it, geometric measurements from the 2D video will not accurately represent the 3D world, leading to errors in tracking, size, and distance calculations. Accurate calibration is essential for tasks like object tracking and 3D reconstruction [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results from Automated Scoring

Problem: The automated scoring system produces variable results that do not consistently match human observer scores across different experiments or video sets.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| Check Calibration | Ensure the system is re-calibrated for each new set of videos recorded under different conditions (e.g., different lighting, arena, or camera angle). Do not assume one calibration fits all [11]. |

| Verify Video Consistency | Confirm all videos have consistent resolution, frame rate, and contrast. Inconsistent source material is a major cause of variable results [11]. |

| Review Threshold Parameters | The optimal freezing threshold is highly dependent on video quality and contrast. Use the software's calibration function to find the best threshold for your specific videos [11]. |

| Inspect for Artefacts | Look for mirror artifacts, reflections, or changes in background lighting that could be causing false positives or negatives in motion detection [11]. |

Issue 2: Poor Image Segmentation in Confocal Microscopy Analysis

Problem: Automated algorithms fail to correctly segment cell boundaries or distinguish between different morphological regions in microscopy images.

Solution: Employ map algebra techniques to create a masking image that facilitates segmentation.

- Action 1: Apply a Focal Filter. Use a function that replaces each pixel with the mean (or other function) of its neighborhood. This smoothing step reduces noise and anomalous pixels, making segmentation more robust [17].

- Action 2: Use Integrated Intensity-Based Methods. This is a variant of watershed segmentation. Determine morphological boundaries by analyzing the rates of change in integrated pixel intensity across the image [17].

- Action 3: Implement Percentile-Based Methods. Segment the image based on global or local pixel intensity percentiles, which can be surprisingly effective for isolating regions of interest [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calibration of an Automated Freezing Scoring System

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to validate the Phobos software [11].

1. Objective: To determine the optimal parameters (freezing threshold, minimum freezing time) for automated freezing scoring that best correlates with manual scoring for a given set of experimental videos.

2. Materials:

- The Phobos software (or equivalent custom script in MATLAB/Python).

- A set of video files (.avi format) from fear conditioning experiments.

- A computer meeting the software's minimum requirements.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Manual Scoring for Calibration. Select one representative video from your set. Using the software's interface, manually score freezing behavior by pressing a button to mark the start and end of each freezing epoch. The software will generate a timestamp file.

- Step 2: Automated Parameter Sweep. The software will then automatically analyze the same calibration video using a wide range of freezing thresholds (e.g., 100 to 6,000 pixels) and minimum freezing times (e.g., 0 to 2 seconds).

- Step 3: Correlation and Fit Analysis. For each parameter combination, the software calculates the freezing time in 20-second bins and correlates it (Pearson's r) with the manual scoring data.

- It selects the 10 combinations with the highest correlation.

- From these, it chooses the five with regression slopes closest to 1.

- Finally, it selects the single combination from those five with the intercept closest to 0.

- Step 4: Application. The selected optimal parameters are saved and can be applied to analyze all other videos recorded under the same conditions.

Protocol 2: Automated Segmentation of Confocal Images using Map Algebra

This protocol is based on methods developed for assessing pixel intensities in heterogeneous cell types [17].

1. Objective: To automate the segmentation of confocal microscopy images into putative morphological regions for pixel intensity analysis, replacing manual segmentation.

2. Materials:

- Confocal microscopy images (e.g., fluorescently-tagged gentamicin in the inner ear).

- R statistical environment with the following packages:

EBImage,spatstat,raster.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Image Pre-processing. Manually remove any gross regions outside the cellular layer of interest. Batch load the images into R using the

EBImagepackage and convert them into rasterlayers. - Step 2: Apply Focal Filter. Use the

focalfunction from therasterpackage to create a smoothed masking image. This replaces each pixel with the mean value of its neighborhood (e.g., a 15x15 kernel), reducing noise. - Step 3: Implement Segmentation Algorithm. Choose and apply one of the following methods to the smoothed masking image:

- Integrated Intensity-Based: Perform watershed-like segmentation by calculating upper and lower thresholds based on the rate of change in integrated pixel intensity.

- Percentile-Based: Segment the image by selecting pixels based on global intensity percentiles.

- Step 4: Pixel Selection and Analysis. Use the segmented masking image to select the corresponding pixels from the original, unsmoothed image for final statistical analysis of pixel intensities.

Key Experimental Parameters for Automated Scoring Systems

The table below summarizes critical parameters from the research, which are essential for replicating and troubleshooting automated scoring pipelines.

| Parameter / Metric | Description | Application Context & Optimal Values |

|---|---|---|

| Freezing Threshold [11] | Max number of non-overlapping pixels between frames to classify as "freezing." | Rodent fear conditioning. Optimal value is data-dependent; Phobos software tests 100-6,000 pixels to find the best match to manual scoring. |

| Minimum Freezing Time [11] | Min duration (in seconds) a potential freezing event must last to be counted. | Rodent fear conditioning. Phobos tests 0-2 sec. A non-zero value (e.g., 0.25-1 sec) prevents brief movements from being misclassified. |

| Segmentation Algorithm [17] | Method for isolating regions of interest in an image. | Confocal microscopy. Integrated intensity (watershed), percentile-based, and local autocorrelation methods are effective alternatives to manual segmentation. |

| Calibration Validation (AUC) [11] | Area Under the ROC Curve; measures classification accuracy. | Model validation. Used to validate tools like Phobos. An AUC close to 1.0 indicates high agreement with a human observer. |

| Re-projection Error [19] | Measure of accuracy in camera calibration; the distance between observed points and re-projected points. | Computer vision/Camera calibration. A lower error indicates better calibration. Used in synthetic benchmarking (SynthCal) to compare algorithms. |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for the Featured Experiments

| Item | Function in the Research Context |

|---|---|

| Confocal Microscopy Images [17] | Primary data source for developing and validating automated image segmentation algorithms for cytoplasmic uptake studies. |

| R Statistical Environment [17] | Platform for implementing custom segmentation algorithms using packages for spatial statistics and map algebra. |

| MATLAB [11] | Programming environment used for developing self-calibrating behavioral analysis software (e.g., Phobos). |

| Phobos Software [11] | A self-calibrating, freely available tool used to automatically quantify freezing behavior in rodent fear conditioning experiments. |

| Synthetic Calibration Dataset (SynthCal) [19] | A pipeline-generated dataset with ground truth parameters for benchmarking and comparing camera calibration algorithms. |

| Calibration Patterns [19] | Known geometric patterns (checkerboard, circular, Charuco) used to estimate camera parameters for accurate video analysis. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Overall automated scoring pipeline.

Diagram 2: Self-calibration workflow for parameter optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is Phobos and what is its main advantage over other automated freezing detection tools? A: Phobos is a freely available software for the automated analysis of freezing behavior in rodents. Its main advantage is that it is self-calibrating; it uses a brief manual quantification by the user to automatically adjust its parameters for optimal freezing detection. This eliminates the need for extensive manual parameter tuning, making it an inexpensive, simple, and reliable tool that avoids the high financial cost and setup time of many commercial systems [20] [21].

Q: What are the minimum computer system requirements to run Phobos? A: The compiled version of the software requires a Windows operating system (Windows 10; Windows 7 Service Pack 1; Windows Server 2019; or Windows Server 2016) and the Matlab Runtime Compiler 9.4 (R2018a), which is available for free download. The software can also be run directly from the Matlab code [20].

Q: My manual quantification result was less than 10 seconds or more than 90% of the video time. What should I do? A: The software will show a warning in this situation. It is recommended that you use a different video for the calibration process, as extreme freezing percentages are likely to yield faulty calibration. A valid calibration video should contain both freezing and non-freezing periods [20] [21].

Q: Can I use the same calibration file for videos recorded under different conditions? A: The calibration file is generated for videos recorded under specific conditions (e.g., lighting, camera angle, arena). For reliable results, you should create a new calibration file for each distinct set of recording conditions. The software validation was performed using videos from different laboratories with different features, confirming the need for context-specific calibration [22] [21].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common issues encountered when setting up and using Phobos.

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Output folder not being selected | A known occasional issue when running the software as an executable file [20]. | Simply repeat the folder selection process. It typically works on the next attempt [20]. |

| Poor correlation between automated and manual scores | 1. The calibration video was not representative.2. The crop area includes irrelevant moving objects.3. Video quality is below minimum requirements. | 1. Re-calibrate using a 2-minute video with a mix of freezing and movement (freezing between 10%-90% of total time) [20] [21].2. Re-crop the video to restrict analysis only to the area where the animal moves [20].3. Ensure videos meet the suggested minimum resolution of 384x288 pixels and a frame rate of 5 frames/s [21]. |

| "Calibrate" button is not working after manual quantification | The manually quantified video was removed from the list before calibration. | The software requires the manually quantified video file to be present in the list to perform calibration. Ensure the video remains loaded before pressing the "Calibrate" button [20]. |

| High variability in results across different users | Inconsistent manual scoring during the calibration step. | The software is designed to minimize this. Ensure all users are trained on the consistent definition of freezing (suppression of all movement except for respiration). Phobos validation has shown that its intra- and interobserver variability is similar to that of manual scoring [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Software Validation and Parameter Optimization

The following methodology details how Phobos was validated and how it optimizes its key parameters, providing a framework for researchers to understand its operation and reliability.

1. Software Description and Workflow Phobos analyzes .avi video files by converting frames to binary images (black and white pixels) using Otsu's method [21]. The core analysis involves comparing pairs of consecutive frames and calculating the number of non-overlapping pixels between them. When this number is below a defined freezing threshold for a duration exceeding the minimum freezing time, the behavior is classified as freezing [21]. The overall workflow integrates manual calibration and automated analysis.

2. Parameter Selection and Calibration Protocol The calibration process automatically optimizes two key parameters by comparing user manual scoring with automated trials [21].

- Step 1: Manual Quantification. The user manually scores freezing in a calibration video using the software interface. The output is a data file with timestamps for every freezing epoch [21].

- Step 2: Automated Parameter Sweep. The software re-analyzes the same calibration video using a range of values for the freezing threshold (from 100 to 6,000 pixels) and minimum freezing time (from 0 to 2 seconds) [21].

- Step 3: Correlation and Selection. Freezing time from both manual and automated scoring is compared in 20-second bins. The software performs a linear regression for each parameter combination and selects the one with the best correlation (Pearson's r) and a slope closest to 1 and an intercept closest to 0 [21].

Table 2: Key Parameters Optimized During Calibration

| Parameter | Description | Role in Analysis | Validation Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freezing Threshold | The maximum number of non-overlapping pixels between frames to classify as freezing. | Determines sensitivity to movement; a lower threshold is more sensitive. | 100 to 6,000 pixels [21] |

| Minimum Freezing Time | The minimum duration a pixel difference must be below threshold to count as a freezing epoch. | Prevents brief, insignificant movements from interrupting freezing bouts. | 0 to 2.0 seconds [21] |

3. Validation and Performance Phobos was validated using video sets from different laboratories with varying features (e.g., frame rate, contrast, recording angle) [21]. The performance was assessed by comparing the intra- and interobserver variability of manual scoring versus automated scoring using Phobos. The results demonstrated that the software's variability was similar to that obtained with manual scoring alone, confirming its reliability as a measurement tool [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Components for a Phobos-Based Freezing Behavior Experiment

| Item | Function/Description | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Phobos Software | The self-calibrating, automated freezing detection tool. | Freely available as Matlab code or a standalone Windows application under a BSD-3 license [21]. |

| Calibration Video | A short video (≥2 min) used to tune software parameters via manual scoring. | Must be recorded under the same conditions as experimental videos and contain both freezing and movement epochs [20] [21]. |

| Rodent Subject | The animal whose fear-related behavior is being quantified. | The software is designed for use with rodents, typically mice or rats. |

| Fear Conditioning Apparatus | The context (e.g., chamber) where the animal is recorded. | Should have consistent lighting and background to facilitate accurate video analysis [21]. |

| Video Recording System | Camera and software to record the animal's behavior in .avi format. | Suggested minimum video resolution: 384 x 288 pixels. Suggested minimum frame rate: 5 frames/second [21]. |

| Matlab Runtime Compiler | Required to run the pre-compiled Phobos executable. | Version 9.4 (R2018a) is required and is available for free download [20]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section provides direct answers to common technical and methodological challenges encountered when developing and calibrating a unified behavioral scoring system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core advantage of using a unified behavioral score over analyzing individual test results? A unified score combines outcomes from multiple behavioral tests into a single, composite metric for a specific behavioral trait (e.g., anxiety or sociability). The primary advantage is that it increases the sensitivity and reliability of your phenotyping. It reduces the intrinsic variability and noise associated with any single test, making it easier to detect subtle but consistent behavioral changes that might be statistically non-significant in individual tests. This approach mirrors clinical diagnosis, where a syndrome is defined by a convergent set of symptoms rather than a single, consistent behavior [23] [24] [25].

FAQ 2: My automated freezing software is producing values that don't match manual scoring. How can I improve its accuracy? This is a common calibration issue. For software like Phobos, ensure your video quality meets minimum requirements (e.g., 384x288 resolution, 5 frames/sec). The most effective strategy is to use the software's built-in calibration function. Manually score a short segment (e.g., 2 minutes) of a reference video. The software will then use your manual scoring to automatically find and set the optimal parameters (like freezing threshold and minimum freezing duration) for your specific recording conditions, thereby improving the correlation between automated and manual results [11].

FAQ 3: How do I combine data from different tests that are on different measurement scales?

The standard method is Z-score normalization. For each outcome measure (e.g., time in open arms, latency to feed), you calculate a Z-score for each animal using the formula: Z = (X - μ) / σ, where X is the raw value, μ is the mean of the control group, and σ is the standard deviation of the control group. This process converts all your diverse measurements onto a common, unit-less scale, allowing you to average them into a single unified score for a given behavioral domain [24].

FAQ 4: We are getting conflicting results between similar tests of anxiety. Is this normal? Yes, and it is a key reason for adopting a unified scoring approach. Individual tests, though probing a similar trait like anxiety, can be influenced by different confounding factors (e.g., exploration, neophobia). A lack of perfect correlation between similar tests is expected. The unified score does not require consistent results across every test; instead, it looks for a converging direction across multiple related measures. This provides a more robust and translational measure of the underlying "emotionality" trait than any single test [24].

FAQ 5: What is the risk of Type I errors when using multiple tests, and how does unified scoring help? Running multiple statistical tests on many individual outcome measures indeed increases the chance of false positives (Type I errors). Unified scoring directly mitigates this by reducing the number of statistical comparisons you need to make. Instead of analyzing dozens of separate measures, you perform a single statistical test on the composite unified score for each major behavioral trait, thereby controlling the family-wise error rate [23] [25].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: High variability in unified scores within a treatment group.

- Potential Cause 1: Inconsistent environmental conditions or handling procedures between testing sessions.

- Solution: Implement strict standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the testing environment (light, noise), time of day, and habituation/handling techniques [23] [25].

- Potential Cause 2: The selected tests may not all be probing the same underlying behavioral construct.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your test battery using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). If tests do not load onto a common component, consider replacing those that are outliers with more relevant paradigms [23].

Issue: The unified score fails to detect a predicted effect.

- Potential Cause 1: The weights assigned to different test outcomes may not be optimal.

- Solution: Initially, use unweighted Z-scores (simple average). If justified by your hypothesis, you can explore machine learning techniques, like Genetic Algorithms or Artificial Neural Networks, to optimize weights based on expert-rated training data [26].

- Potential Cause 2: A "ceiling" or "floor" effect in one of the tests is masking variation.

- Solution: Check the distribution of raw data for each test. If animals are clustering at the minimum or maximum of a test's scale, that test may be unsuitable for your model population and should be replaced [23].

Issue: Poor performance of automated video-tracking software.

- Potential Cause 1: Poor video quality or contrast between the animal and background.

- Solution: Ensure even, diffuse lighting and use a background color that contrasts highly with the animal's coat. Check that the camera resolution and frame rate meet the software's minimum requirements [11].

- Potential Cause 2: Suboptimal software parameters (e.g., immobility threshold, sample rate).

- Solution: Always perform a calibration step. Use the software's tools to define the animal's body point accurately and run a pilot study to manually validate the automated output against human scoring for a subset of videos, adjusting parameters as needed [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Core Methodology: Constructing an Integrated Z-Score

The following workflow is adapted from established protocols for creating unified behavioral scores in rodent models [23] [24] [25].

Step 1: Perform a Behavioral Test Battery. Expose experimental and control animals to a series of tests designed to probe the behavioral trait of interest (e.g., anxiety). Tests should be spaced days apart to minimize interference [24].

Step 2: Extract Raw Outcome Measures. From the videos or live observation, extract quantitative data for each test (e.g., time in open arms, latency to feed, crosses into light area) [23] [25].

Step 3: Z-score Normalization. For each outcome measure, calculate a Z-score for every animal (both experimental and control) normalized to the control group's mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) [24]. See Table 1 for an example.

Step 4: Assign Directional Influence. Before combining Z-scores, assign a positive or negative sign to each one based on its known biological interpretation. For example, in an anxiety score, an increase in time in an anxiogenic area would contribute negatively (-Z), while an increase in latency to enter would contribute positively (+Z) [25].

Step 5: Calculate the Composite Unified Score. For each animal, calculate the simple arithmetic mean of all the signed, normalized Z-scores from the different tests. This mean is the unified behavioral score for that trait [24].

Table 1: Example Z-Score Calculation for Anxiety-Related Measures (Hypothetical Data)

| Test | Outcome Measure | Control Mean (μ) | Control SD (σ) | Animal Raw Score (X) | Z-Score | Influence | Final Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated Zero Maze | Time in Open (s) | 85.0 | 15.0 | 70.0 | (70-85)/15 = -1.00 | Negative | +1.00 |

| Light/Dark Box | Latency to Light (s) | 25.0 | 8.0 | 40.0 | (40-25)/8 = +1.88 | Positive | +1.88 |

| Open Field | % Center Distance | 12.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | (8-12)/4 = -1.00 | Negative | +1.00 |

| Unified Anxiety Score (Mean of Final Contribution) | +1.29 |

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Behavioral Scoring Experiments

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| C57BL/6J Mice | A common inbred mouse strain with well-characterized behavioral phenotypes, often used as a background for genetic models and as a control [23] [25]. |

| 129S2/SvHsd Mice | Another common inbred strain; comparing its behavior to C57BL/6J can reveal strain-specific differences crucial for model selection [23] [25]. |

| Automated Tracking Software (e.g., EthoVision XT) | Video-based system for automated, high-throughput, and unbiased tracking of animal movement and behavior across various tests [23] [25]. |

| Specialized Freezing Software (e.g., Phobos) | A self-calibrating, freely available tool specifically designed for robust automated quantification of freezing behavior in fear conditioning experiments [11]. |

| Behavioral Test Apparatus | Standardized equipment for specific tests (e.g., Elevated Zero Maze, Light/Dark Box, Social Interaction Chamber) to ensure reproducibility [23] [24] [25]. |

Calibration in Automated Behavior Scoring

Calibration is the process of aligning automated scoring systems with ground truth, typically defined by expert human observers. This is critical for ensuring data reliability and cross-lab reproducibility.

Calibration Workflow for Automated Software

The following diagram outlines a consensus-based approach for calibrating automated behavioral scoring tools, integrating principles from fear conditioning and virtual lab assessment [11] [26] [27].

Key Steps:

- Define the Behavior: Establish a clear, operational definition of the behavior (e.g., freezing, self-grooming) that all human scorers and the software will use.

- Establish Expert Consensus: Have multiple trained researchers manually score the same set of calibration videos. This set should cover a wide range of behavioral intensities and challenging scenarios [11] [27].

- Ensure Reliability: Calculate inter-rater reliability (e.g., Intraclass Correlation Coefficient). High agreement is necessary to create a reliable "gold standard" dataset [11].

- Software Calibration & Validation: Run the automated software on the calibration videos. Compare its output to the human-derived gold standard using correlation coefficients and measures of absolute agreement (e.g., Bland-Altman plots). Adjust software parameters until the agreement is acceptable [11] [26].

Quantitative Comparison of Scoring Methods

Table 3: Comparison of Behavioral Scoring Methods

| Method | Key Features | Relative Cost | Throughput | Subjectivity/ Variability | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Scoring | Direct observation or video analysis by a human. | Low | Low | High | Initial method development, defining complex behaviors, small-scale studies [11]. |

| Commercial Automated Software (e.g., EthoVision) | Comprehensive, video-based tracking of multiple parameters. | High | High | Low (after calibration) | High-throughput phenotyping, standardized tests (open field, EPM) [23] [25]. |

| Free, Specialized Software (e.g., Phobos) | Focused on specific behaviors (e.g., freezing); often includes self-calibration [11]. | Free | Medium | Low (after calibration) | Labs with limited budget, specific behavioral assays like fear conditioning [11]. |

| Unified Z-Scoring (Meta-Analysis) | Mathematical integration of results from multiple tests or studies [24]. | (Analysis cost only) | N/A | Very Low | Increasing statistical power, detecting subtle phenotypes, cross-study comparison [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Data Pathology and Performance Drops in Real-World Deployment

Problem: AI model performance drops by 15-30% when deployed in real-world clinical settings compared to controlled testing environments [28].

Symptoms:

- High false-negative rates (e.g., 28% higher in underrepresented subgroups) [28].

- Systematic underdiagnosis in minority populations [28].

- Model performs well on initial test datasets but fails on new patient data.

Solutions:

- Implement Dynamic Data Auditing: Use federated learning to compute subgroup-stratified metrics (AUC, sensitivity, specificity) locally. Share privacy-preserving aggregates to monitor data drift and fairness, setting threshold-based alerts [28].

- Bias-Aware Data Curation: Actively ensure training datasets include representative data from all racial, age, and geographic groups relevant to your target population [28].

- Apply Bias Mitigation Techniques: Use algorithmic reweighting or sampling quotas during model training to correct for identified representation disparities [28].

Guide 2: Mitigating Automation Bias and Over-reliance on AI

Problem: Clinicians may develop automation complacency, leading to delayed correction of AI errors (41% slower error identification reported in some workflows) [28].

Symptoms:

- Clinicians accept AI recommendations without sufficient scrutiny.

- Diagnostic accuracy decreases when AI is incorrect, especially among inexperienced users [29].

- Failure to identify AI errors that would otherwise be obvious.

Solutions:

- Implement Trust Calibration: Explicitly ask users whether the final diagnosis is contained within the AI-generated differential list. This prompts active critical thinking, though its effectiveness can vary [29].

- Provide Real-Time Interpretability: Use explainability engines like Grad-CAM or structural causal models to show the rationale behind AI decisions, aligning salient regions with clinically meaningful variables [28].

- Design for Cognitive Collaboration: Frame AI as a tool that supports both intuitive (System 1) and analytical (System 2) clinical reasoning, rather than replacing either [30].

Guide 3: Resolving "Black Box" Opacity and Trust Deficits

Problem: Model opacity limits error traceability and undermines clinician trust, with radiologists taking 2.3 times longer to audit deep neural network decisions [28].

Symptoms:

- 34% of clinicians report overriding correct AI recommendations due to distrust [28].

- Inability to understand or explain AI reasoning to patients or colleagues.

- Reluctance to integrate AI into critical diagnostic workflows.

Solutions:

- Deploy Hybrid Explainability Engines: Combine gradient-based saliency maps with structural causal models. Run counterfactual queries with faithfulness checks to yield concise, clinician-facing rationales [28].

- Use Interpretability Dashboards: Implement real-time visualization tools that highlight features influencing AI decisions and their clinical correlation [28].

- Establish Model Fact Sheets: Maintain versioned documentation detailing model capabilities, limitations, and intended use cases to set appropriate expectations [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)