Conquering Motion Artifacts in Behavioral Neuroimaging: From Prevention to AI-Powered Correction

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing motion artifacts in neuroimaging during behavioral tasks.

Conquering Motion Artifacts in Behavioral Neuroimaging: From Prevention to AI-Powered Correction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing motion artifacts in neuroimaging during behavioral tasks. It explores the fundamental physics and origins of motion-related signal corruption in key modalities like fMRI and fNIRS, which are crucial for assessing brain function in active participants. The content details a toolbox of mitigation strategies, from simple patient preparation to advanced deep learning and algorithmic corrections. A comparative analysis validates the performance of various methods, from established techniques like ICA-AROMA to novel generative models, providing a clear framework for selecting optimal motion correction approaches to ensure data integrity in clinical and cognitive neuroscience research.

The Motion Problem: Unraveling the Physics and Impact on Behavioral Data

Why Neuroimaging is Uniquely Sensitive to Subject Motion

Why is motion a particularly critical problem in neuroimaging?

Motion is a paramount concern in neuroimaging because even sub-millimeter movements—smaller than the typical voxel size—are large enough to significantly compromise the quality and reliability of both functional and structural data [1] [2]. Unlike a simple photograph where motion causes blurring, the effects of motion in neuroimaging are complex and can mimic or obscure genuine brain signals, leading to false conclusions in research and clinical assessments [1].

The core reasons for this unique sensitivity include:

- The Physics of Data Acquisition: When a subject moves inside an MRI scanner, it perturbs the spatial frequencies (k-space) used to construct the image. This introduces artifacts that are not localized but propagate throughout the entire image, manifesting as ghosting, ringing, and blurring [1].

- The Challenge of Task-Correlated Motion: In functional MRI (fMRI) studies, participants often move in sync with a task (e.g., a button press in response to a stimulus). This creates a situation where the motion is systematically correlated with the experimental paradigm. Since standard analysis methods are designed to detect signal changes time-locked to the task, this correlated motion can be easily misinterpreted as true brain activation [3] [4].

- Impact on Key Metrics: Motion artifacts have a downstream effect on nearly all common neuroimaging metrics. For structural scans, motion can lead to underestimates of cortical thickness and grey matter volume [1]. For functional scans, it can inflate or distort measures of functional connectivity between brain regions [5].

Quantifying the Motion Problem: Key Indicators and Impacts

Understanding which factors predict motion can help in better study planning. The following table summarizes key indicators of in-scanner head motion identified from a large-scale study of 40,969 subjects [2].

Table 1: Subject Indicators of fMRI Head Motion

| Indicator Category | Specific Indicator | Association with Head Motion |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | Body Mass Index (BMI) | Strongest indicator. A 10-point increase in BMI (e.g., from "healthy" to "obese") corresponds to a 51% increase in motion [2]. |

| Demographic | Age | Motion is higher at the extreme ends of the age distribution (e.g., in children and older adults) [1] [2]. |

| Ethnicity | A significant association was identified, though the specific reasons are complex and may be socio-economic rather than biological [2]. | |

| Clinical & Behavioral | Psychiatric & Neurological Disorders | Populations with ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and schizophrenia tend to exhibit significantly increased motion [1]. |

| Cognitive Task Performance | Performing a cognitive task in the scanner is associated with increased head motion compared to rest [2]. | |

| Executive Functioning | In older adults, poorer performance on tasks of inhibition and cognitive flexibility is correlated with a higher number of motion-corrupted scans [6]. |

The impact of motion also depends on the type of data being acquired and the analysis method used. The table below outlines how motion affects different neuroimaging domains.

Table 2: Impact of Motion Across Neuroimaging Domains

| Neuroimaging Domain | Primary Impact of Motion | Evidence from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Structural MRI | Artificial reduction of grey matter volume and cortical thickness [1]. | Motion can create a false, non-linear trajectory of cortical development in youth [1]. |

| fMRI (Task-Based) | Introduction of false positives (artifactual activations) and false negatives (masked true activations), especially with block designs [7] [4]. | Motion parameters correlated with a task paradigm (r ~0.5) can cause spurious activations [4]. |

| fMRI (Resting-State) | Inflation of functional connectivity measures, particularly in short-range connections; reduces test-retest reliability [2] [5]. | Full correlation is highly sensitive to motion; partial correlation and coherence are more robust [5]. |

| Clinical Group Analysis | Confounding of case-control differences, as patient groups often move more than healthy controls [1]. | In Autism studies, inconsistent findings of cortical thickness have been linked to differing motion exclusion criteria [1]. |

A Researcher's Guide to Motion Correction Methodologies

A multi-pronged strategy is required to tackle motion, involving both prospective (during scanning) and retrospective (after scanning) methods.

Prospective Motion Reduction Strategies

These methods aim to minimize motion at its source.

- Subject Preparation: Clear communication, acclimation to the scanner environment, and comfortable positioning are crucial [1] [2].

- Use of Head Stabilization: Personalized head moulds and foam padding can significantly restrict movement [2].

- Real-Time Feedback: Systems that provide visual or tactile feedback to the subject about their head position can help them remain still [2].

- Task Design: For fMRI, using rapid event-related designs instead of block designs can help decouple the task from motion, reducing the risk of correlated artifacts [4].

Retrospective Motion Correction Algorithms

These are standard preprocessing steps applied to the data after acquisition.

- Rigid-Body Realignment: This is the most common method, implemented in tools like FSL's MCFLIRT or SPM's realign. It models head motion as a rigid body with six degrees of freedom (translations and rotations along x, y, z axes) and realigns all volumes in a time-series to a reference volume [3].

- Motion Parameter Regression (MPR): The six motion parameters estimated during realignment are included as nuisance regressors in the statistical model (e.g., General Linear Model) to remove variance associated with motion [4] [8]. Caution: In block designs, if motion is correlated with the task, MPR can remove genuine brain signal along with the artifact [4].

- Motion Scrubbing: Data points (volumes) that are identified as severe motion outliers are removed from the analysis entirely [7].

- Incorporating Motion Covariates in Group Analysis: Including a subject-level measure of motion (e.g., mean framewise displacement) as a covariate in group-level statistics helps control for inter-subject differences in motion [4].

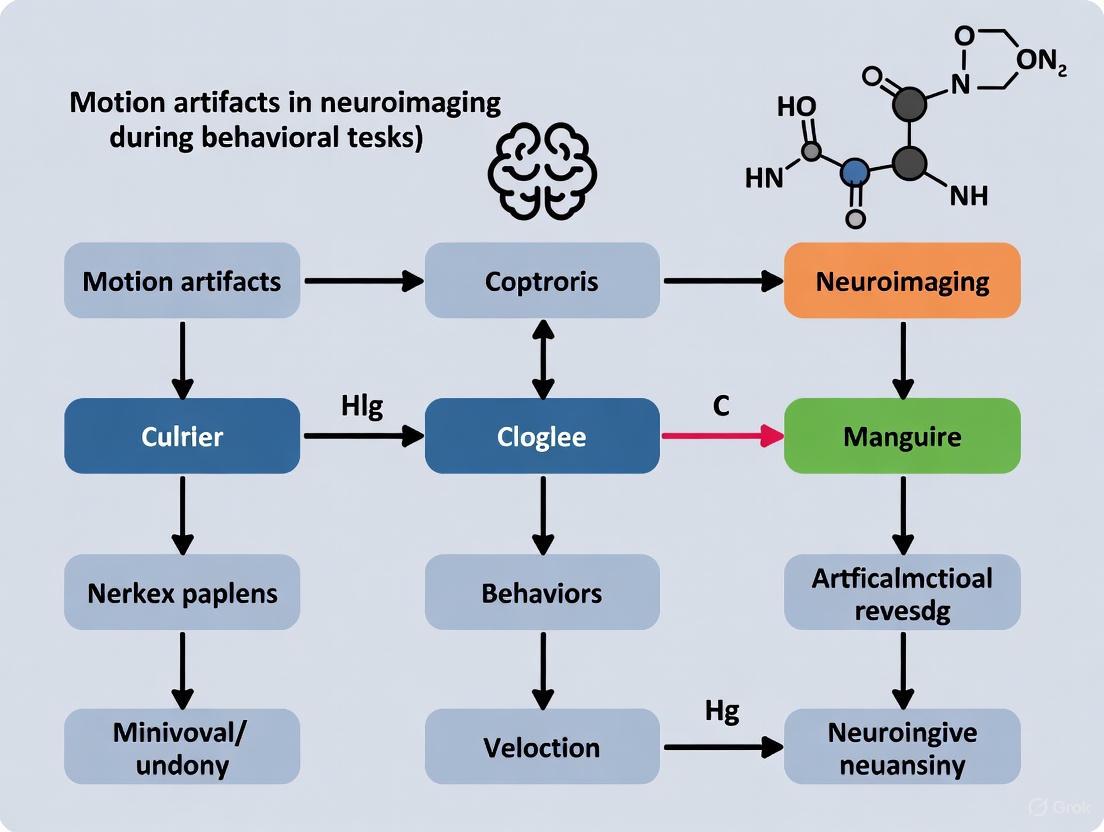

The following diagram illustrates a standard workflow for integrating these retrospective correction methods into an fMRI preprocessing pipeline.

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Research Reagents for Motion Correction

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSL MCFLIRT [3] | Software Algorithm | Performs rigid-body motion correction on fMRI time-series. | A standard, widely-used tool. Often used as a benchmark. |

| SPM Realign [4] | Software Algorithm | Performs rigid-body realignment as part of the SPM preprocessing pipeline. | Integrated into the popular SPM software suite. |

| AIR (Automated Image Registration) [4] | Software Algorithm | An early and influential image registration tool adapted for fMRI motion correction. | |

| Motion Parameters (6+) [4] | Data Output | The translational (x,y,z) and rotational (pitch,roll,yaw) parameters estimated during realignment. | Used for regression and quality control. The "root mean square" (RMS) is a common summary metric [2]. |

| Framewise Displacement (FD) | Quantitative Metric | A scalar value that quantifies volume-to-volume head movement. | Used to identify motion outliers for scrubbing [6]. |

| NPAIRS Framework [8] | Validation Framework | A data-driven framework for evaluating preprocessing pipeline performance using cross-validation. | Helps optimize pipeline choices for a specific dataset. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our patient group moves significantly more than our healthy controls. Should we exclude high-movers, and what are the alternatives? This is a common dilemma in clinical neuroscience [1]. Excluding high-movers risks biasing your sample and losing hard-to-recruit patients. Alternatives include:

- Proactive Mitigation: Invest more time in participant preparation, use improved head stabilization, and consider real-time motion correction techniques [2].

- Statistical Control: Include subject-level motion estimates as a covariate in your group-level analysis [4].

- Robust Analysis Methods: Choose functional connectivity measures that are less sensitive to motion, such as partial correlation instead of full correlation [5].

- Transparent Reporting: Always report motion exclusion criteria and the amount of motion in each group to allow for informed interpretation of results [1].

Q2: We've applied rigid-body motion correction. Is our data now clean? Not necessarily. Motion correction is essential but imperfect [4]. Residual artifacts often remain because:

- Physics-Based Distortions: Head movement causes dynamic changes in the magnetic field, leading to nonlinear distortions that rigid-body models cannot correct [4].

- Intra-Volume Motion: Motion that occurs during the acquisition of a single volume cannot be fully characterized or corrected by standard methods [4].

- Spin-History Effects: Motion affects the longitudinal magnetization of spins, creating signal changes that are not addressed by spatial realignment [4]. Therefore, motion correction should be seen as a necessary first step, but it must often be combined with other methods like MPR or scrubbing.

Q3: For an event-related fMRI design, what is the most effective motion correction strategy? Research indicates that for rapid event-related designs, including the motion parameters as covariates (MPR) in the general linear model is highly effective at increasing sensitivity [4]. Interestingly, in this context, it may matter less whether the motion correction (realignment) was actually applied to the data before this step, as the MPR can account for a large portion of the motion-related variance [4].

Q4: How does motion specifically affect studies of brain development or aging? Motion can profoundly confound studies across the lifespan. In developmental studies, younger children move more, which can create a false impression of exaggerated cortical thinning with age if motion is not controlled [1]. In older adults, higher motion is correlated with poorer executive functioning, meaning that excluding high-movers may systematically remove those with lower cognitive performance, biasing the sample and skewing our understanding of the aging brain [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Resolving Ghosting Artefacts

Problem: My fMRI images show repeating ghost-like duplicates of the brain structure, often in the phase-encoding direction.

Root Cause: Ghosting artefacts primarily arise from inconsistencies between different portions of the k-space data used for image reconstruction. This can be caused by:

- Phase Discontinuities: Constant-phase shifts between echoes, caused by factors like magnetic field inhomogeneities, chemical shift, or receiver-phase misregistrations [9].

- Amplitude Discontinuities: Variations in signal amplitude between k-space lines, for instance, due to T2 decay or periodic motion [9].

- System Imperfections: Timing misregistrations from system filter delays or eddy currents [9].

Solutions:

- Use Reference Scans: Acquire "reference" scans without phase-encoding to measure constant-phase offsets and timing delays. These measurements can then be used for post-processing correction [9].

- Optimize K-space Ordering: For periodic motion (e.g., respiration, cardiac pulsation), use a k-space acquisition order that is synchronized with the motion to minimize inconsistencies [10].

- Apply Post-Processing Algorithms: Implement correction algorithms that apply measured constant-phase shifts and phase rolls to correct for time shifts in the k-space data before Fourier transformation [9].

Guide 2: Addressing Image Blurring

Problem: My fMRI data appears unfocused, with a loss of sharpness at contrast edges.

Root Cause: Blurring is typically the result of slow, continuous motion during the data acquisition period. This is particularly problematic for sequences using interleaved k-space acquisitions, such as T2-weighted Turbo Spin Echo (TSE/FSE) sequences [10]. Unlike sudden motion that causes ghosting, slow drifts violate the assumption that the object is stationary throughout the scan, leading to a smearing of information in k-space.

Solutions:

- Prospective Motion Correction: Use real-time head-tracking systems (e.g., optical tracking, navigator echoes) to adjust the imaging plane during data acquisition [11] [12].

- Increase Acquisition Speed: Use faster imaging sequences to reduce the time window during which motion can occur [10].

- Retrospective Correction: Employ image registration techniques to align all volumes in a time series to a reference volume. This is a common first step in fMRI preprocessing [11] [13].

Guide 3: Managing Residual Motion Artefacts After Correction

Problem: Even after volume realignment (motion correction), my functional connectivity (RSFC) results show motion-related biases.

Root Cause: Standard 3D volume registration does not fully correct for all motion-induced signal changes. Residual artefacts stem from:

- Partial Volume Effects: The resampling of the target image during realignment causes mixing of signals from different tissue types [12].

- Spin History Effects: Motion moves spins into and out of the imaging plane, altering their excitation history and leading to signal modulations [12].

- Intra-volume Motion: Motion occurring during the acquisition of a single volume cannot be corrected by inter-volume registration [12].

Solutions:

- Incorporate Slice-Level Correction: Use methods like SLOMOCO that perform slice-wise motion correction to account for intra-volume motion [12].

- Apply Nuisance Regressors: Regress out signals derived from motion parameters (e.g., Vol-mopa, Sli-mopa) and proposed regressors like the Partial Volume (PV) regressor to remove residual variance related to motion [12].

- Data Scrubbing: Identify and remove individual volumes that are excessively corrupted by motion [14]. Framewise displacement (FD) is a common metric for this [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is fMRI particularly sensitive to subject motion compared to other MRI types?

fMRI is exquisitely sensitive to motion because it detects very small signal changes (often 1-2%) related to the BOLD (Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent) effect [9] [15]. The primary data acquisition occurs in k-space (Fourier space), where each sample contains global spatial information about the entire image. Any motion during acquisition creates inconsistencies in k-space, which, upon reconstruction, manifest as artefacts like ghosting and blurring that can obscure or mimic genuine neural activity [10] [13].

FAQ 2: What is the fundamental link between k-space errors and image artefacts?

The final MR image is generated via an inverse Fourier transform of the acquired k-space data. Simple reconstruction assumes the object is perfectly stationary. Motion causes the k-space data to be an inconsistent mix of information from different object positions. This violation of the reconstruction model directly creates artefacts [10]. The specific nature of the motion determines the pattern of k-space corruption and, consequently, the type of artefact:

- Periodic Motion causes coherent modulation, leading to ghosting [10] [9].

- Slow, Continuous Motion causes a broader corruption, leading to blurring [10].

FAQ 3: What are the main categories of motion correction techniques?

Motion correction strategies can be broadly classified into two groups:

- Prospective Correction: Motion is detected and corrected during data acquisition. Examples include optical tracking or navigator echoes that adjust the imaging plane in real-time [11].

- Retrospective Correction: Motion is corrected after data acquisition. This includes volume-based realignment and more advanced slice-based methods, and often involves weighting or "scrubbing" of corrupted data volumes [11] [12] [16].

FAQ 4: How can I quantitatively assess the severity of ghosting artefacts in my data?

The intensity of ghosting artefacts can be mathematically described and quantified. For example, in interleaved EPI, the ghost kernel resulting from an amplitude discontinuity is given by a specific equation that includes the modulation parameters [9]. In quality assurance (QA) protocols, the Signal-to-Ghost Ratio (SGR) is a key metric used to evaluate system performance and can be applied to your data to quantify ghosting severity [15].

Quantitative Data Reference

Table 1: Characteristics of Common fMRI Motion Artefacts

| Artefact Type | Primary Cause | K-space Origin | Typical Appearance | Correction Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghosting | Periodic motion (respiration, pulsation), system phase errors [10] [9] | Phase/amplitude discontinuities between lines [9] | Replicas of the main image shifted along the phase-encode direction [10] | Reference scans, k-space reordering, post-processing phase correction [9] |

| Blurring | Slow, continuous motion (drift) [10] | Data inconsistency across entire k-space [10] | Loss of sharpness and fine detail [10] | Prospective motion correction, faster acquisition, registration [10] [11] |

| Signal Loss | Spin dephasing in magnetic field gradients [10] | Irreversible signal loss from magnetization evolution [10] | Dark regions in the image, often near tissue boundaries | Ensure subject comfort to minimize bulk motion, use spin-prep methods less sensitive to motion [10] |

Table 2: Essential Tools for the fMRI Researcher's Toolkit

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Software/Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective Motion Correction | Software Package | Corrects for head motion after data acquisition by aligning volumes. | FSL (MCFLIRT), AFNI, SPM [11] [12] |

| Advanced Motion Correction Pipelines | Software Pipeline | Corrects for intra-volume motion and spin history effects at the slice level. | SLOMOCO [12] |

| Nuisance Regressor Regression | Data Cleaning Method | Removes residual motion artefact from the signal after motion correction. | Partial Volume (PV) Regressors, Vol-/Sli-mopa [12] |

| Data Scrubbing | Data Cleaning Method | Identifies and removes severely motion-corrupted volumes from the time series. | Framewise Displacement (FD) [14] [15] |

| QA Phantom | Physical Standard | Mimics brain properties to measure scanner stability and artefact levels for QA. | FBIRN Phantom [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Reference Scan Correction for Ghosting

Purpose: To measure and correct for system-induced phase offsets and timing delays that cause ghosting artefacts in interleaved EPI.

Methodology:

- Acquire Reference Scans: Prior to or following the main fMRI acquisition, run a calibration scan with the phase-encoding gradient turned off.

- Acquire Internal Reference Lines: Collect at least two "internal reference" lines to measure time delays [9].

- Reconstruct with Correction: Integrate the measured phase offsets and time delays into the reconstruction pipeline: a. Fourier transform the raw data in the readout direction. b. Apply the constant-phase shift corrections and phase rolls to the data to correct for the measured time shifts. c. Perform the final Fourier transform in the phase-encoding direction to generate the artefact-corrected image [9].

Protocol 2: A SIMPACE Pipeline for Validating Motion Correction

Purpose: To generate motion-corrupted fMRI data with known, user-defined motion parameters for validating motion correction algorithms.

Methodology:

- Phantom Setup: Use an ex vivo brain phantom fixed in a container to provide a stable, motionless baseline [12].

- Inject Motion: Utilize the Simulated Prospective Acquisition Correction (SIMPACE) sequence to synthetically alter the imaging plane coordinates before each volume and slice acquisition, emulating realistic intervolume and intravolume motion [12].

- Data Analysis: Process the simulated motion-corrupted data with different motion correction pipelines (e.g., VOLMOCO, SLOMOCO) and nuisance regressors. Compare the residual signal (e.g., standard deviation in gray matter) to quantify the efficacy of each correction method [12].

Visualizations

K-space Corruption and Image Artefacts

Motion Correction Pipeline for fMRI Data

Motion artifacts represent one of the most significant challenges in task-based neuroimaging research, potentially compromising data quality and leading to spurious findings. These artifacts originate from two primary sources: physiological motion (e.g., cardiac pulsation, respiration, and tremors) and voluntary motion (e.g., head movements, swallowing, and task-related movements). In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), even small movements can cause significant signal changes that may be misinterpreted as neural activity, particularly because the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal change related to neuronal activity is typically only 1-2% [17]. The problem is especially pronounced in task-based paradigms where subjects must perform voluntary movements as part of the experimental design, creating a dual challenge of capturing intended motor activity while eliminating confounding motion artifacts.

The sensitivity of neuroimaging techniques to motion varies considerably. MRI is particularly vulnerable to motion due to prolonged acquisition times and the encoding of spatial information in frequency space (k-space), where motion causes inconsistencies that manifest as ghosts, blurring, and signal loss in reconstructed images [10]. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), while more resilient to motion than fMRI, still faces significant artifact challenges from optode-scalp decoupling during head movements [18]. Understanding, mitigating, and correcting these artifacts is therefore essential for maintaining data integrity in behavioral tasks research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is MRI particularly sensitive to subject motion compared to other imaging modalities?

MRI's sensitivity to motion stems from its sequential data acquisition process in k-space (frequency space). Unlike photographic techniques that capture image data directly, MRI encodes spatial information through a series of measurements in k-space that are later transformed into images using Fourier transformation. When motion occurs during this sequential acquisition, it creates inconsistencies in k-space data that manifest as various artifacts in the reconstructed images, including blurring, ghosting, and signal loss [10]. This problem is exacerbated in longer acquisitions and techniques with inherent low signal-to-noise ratio like fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging.

Q2: What are the main types of motion artifacts encountered in task-based neuroimaging?

Motion artifacts generally fall into three categories:

- Rigid body motion: Movement of the head or body as a single unit, causing shifted or rotated imaging data

- Non-rigid body motion: Deformation or shape changes during scanning, causing more complex artifacts

- Physiological motion: Motion from breathing, heartbeat, blood flow, or other biological processes [19]

In task-based paradigms, voluntary movements required by the experimental design introduce additional rigid and non-rigid motions that can be difficult to distinguish from the neural signals of interest.

Q3: How do motion artifacts affect statistical analysis in task-based fMRI?

Motion artifacts can induce signal changes that confound statistical analysis in multiple ways. In worst-case scenarios, motion-related signal changes may become correlated with task activation patterns, leading to false positives or inflated effect sizes. Motion also introduces structured noise that violates the assumption of independent and identically distributed Gaussian noise in standard statistical models [17]. Even after motion correction, residual artifacts can reduce statistical power and validity.

Q4: Can motion artifacts mimic genuine brain network activity?

Yes, research has demonstrated that motion artifacts can produce spatial patterns resembling genuine functional connectivity networks. Carefully mapped head movement artifacts have been shown to create patterns similar to the default mode network, potentially leading to misinterpretation of network connectivity in resting-state and task-based studies [17]. This is particularly problematic for studies of populations with different movement characteristics, such as children, elderly individuals, or patients with movement disorders.

Troubleshooting Guides

Prevention Strategies During Data Acquisition

Subject Preparation and Positioning

- Comfort Optimization: Use foam padding and comfortable head restraints to minimize voluntary movement. Ensure the subject is properly positioned and comfortable before scanning begins.

- Comprehensive Pre-scan Briefing: Clearly explain the importance of remaining still, providing specific examples of problematic movements (e.g., swallowing, head adjustments). For task-based paradigms, practice the movement outside the scanner to minimize excessive motion.

- Physiological Monitoring: Implement cardiac and respiratory monitoring for later gating or noise correction, particularly for paradigms sensitive to physiological noise.

Sequence Optimization

- Acquisition Parameter Adjustment: Utilize faster imaging sequences (e.g., parallel imaging, multiband acquisitions) to reduce motion sensitivity by shortening acquisition windows [10].

- K-space Reordering Strategies: Employ motion-resistant k-space sampling trajectories such as radial, PROPELLER, or spiral sequences that are less sensitive to motion artifacts than standard Cartesian sampling [10].

- Gating and Triggering: Implement cardiac gating for sequences sensitive to pulsatility (e.g., diffusion imaging) and respiratory gating for abdominal or thoracic imaging.

Motion Tracking and Monitoring

Hardware-Based Motion Tracking

- Camera-Based Systems: Optical tracking systems using cameras to monitor head position in real-time, allowing for prospective motion correction [19].

- Sensor-Based Systems: Inertial measurement units (IMUs), accelerometers, or gyroscopes attached to the subject to provide continuous motion data [19].

- MR-Compatible Optical Tracking: Systems specifically designed to operate within the MR environment, providing real-time head position data for prospective correction.

Image-Based Motion Tracking

- Navigator Echoes: Brief additional MR acquisitions interspersed throughout the sequence to detect subject position.

- Image-Based Registration: Real-time image registration to detect inter-volume motion for prospective correction.

Post-Processing Correction Methods

Retrospective Motion Correction

- Rigid-Body Registration: Standard volume realignment using six-parameter (three translation, three rotation) rigid body transformation to correct for inter-volume motion [17].

- Slice-Based Correction: Methods like SLOMOCO that perform slice-wise motion correction to address intra-volume motion, which is particularly effective for spin-echo sequences [12].

- Advanced Registration Algorithms: Non-linear registration techniques that can correct for non-rigid motion and deformations.

Nuisance Regression Techniques

- Motion Parameter Regression: Including the six motion parameters (and their derivatives) as regressors in general linear model analysis to account for motion-related variance.

- Spike Regression: Identifying and regressing out volumes with excessive motion ("spikes") to minimize their influence on statistical results.

- Partial Volume Regressors: Voxel-wise motion nuisance regressors that account for partial volume effects at tissue boundaries [12].

Data-Driven Cleaning Approaches

- Independent Component Analysis: ICA-based methods like ICA-AROMA that automatically identify and remove motion-related components from fMRI data without requiring manual classification [20].

- Principal Component Analysis: Using PCA to identify and remove major sources of variance attributable to motion.

- CompCor: A component-based noise correction method that identifies noise regions of interest (e.g., white matter, CSF) and removes their signal contributions.

Table 1: Comparison of Motion Correction Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume-Based Registration | 3D rigid-body transformation between volumes | Widely available, computationally efficient | Cannot correct intra-volume motion | Block-design fMRI with minimal movement |

| Slice-Based Correction (SLOMOCO) | Motion correction at slice acquisition level | Addresses spin history effects, handles intra-volume motion | More computationally intensive | Sequences with long TR, high-resolution fMRI |

| ICA-AROMA | Automatic classification and removal of motion components | No manual classification needed, preserves temporal structure | May remove neural signal in some cases | Resting-state and task-based fMRI |

| Prospective Motion Correction | Real-time adjustment of imaging plane | Prevents artifacts rather than correcting them | Requires specialized hardware/sequences | Populations prone to movement (children, patients) |

| Retrospective Correction with SIMPACE | Uses simulated motion data for optimization | Provides gold-standard correction validation | Currently limited to research settings | Methodological development and validation |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Management

Protocol for Combined fMRI-fNIRS in Task Paradigms

Rationale: Combining fMRI's high spatial resolution with fNIRS's superior temporal resolution and motion resilience provides complementary data streams, with fNIRS serving as a validation tool for fMRI findings in moving subjects [21].

Equipment Setup

- Synchronize fMRI and fNIRS acquisition systems using a common trigger signal

- Position fNIRS optodes to cover regions of interest while minimizing interference with MRI head coils

- Use MRI-compatible fNIRS systems with non-magnetic components and filtered cabling

- Implement motion tracking for both modalities (camera-based for fNIRS, navigators for fMRI)

Data Acquisition Parameters

- fMRI: Use multiband EPI sequences with in-plane acceleration to reduce TR and motion sensitivity

- fNIRS: Employ dual-wavelength systems (e.g., 760 nm and 850 nm) with sampling rates ≥10 Hz

- Motion Tracking: Record camera-based optode movement tracking for fNIRS and volumetric navigators for fMRI simultaneously

Processing Pipeline

- Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing separately to fMRI (motion correction, smoothing) and fNIRS (filtering, motion artifact correction) data

- Motion Detection: Identify motion-contaminated epochs in both modalities using threshold-based approaches

- Temporal Alignment: Precisely align fMRI and fNIRS time series using recorded trigger pulses

- Hemodynamic Response Comparison: Compare motion-corrected hemodynamic responses across modalities to validate correction efficacy

Protocol for Residual Motion Artifact Removal Using SIMPACE

Rationale: The SIMPACE (Simulated Prospective Acquisition Correction) method uses ex vivo brain phantoms to generate gold-standard motion-corrupted data, enabling optimization of motion correction pipelines with known ground truth [12].

Phantom Preparation

- Prepare formalin-fixed ex vivo brain phantom soaked in Fomblin to remove bubbles

- Position phantom in 3D-printed holder within standard head coil

- Ensure temperature stabilization before data acquisition

SIMPACE Data Acquisition

- Acquire reference 2D EPI data without motion simulation

- Program SIMPACE sequence with predefined motion patterns (intervolume and intravolume)

- Inject varying degrees of motion (translation, rotation, and combined movements)

- Repeat for different k-space sampling trajectories (linear, interleaved)

Motion Correction Pipeline Optimization

- Apply standard volume-based correction (e.g., FSL MCFLIRT) and calculate residual artifacts

- Implement slice-wise correction (SLOMOCO) addressing intravolume motion

- Apply partial volume regressors to address residual boundary artifacts

- Compare performance against ground truth phantom data

- Iteratively refine parameters to minimize residual motion in gray matter

Validation Metrics

- Standard deviation of residual time series in gray matter regions

- Quantitative comparison with ground truth reference data

- Reduction in motion-to-signal ratio across different motion patterns

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Motion Correction Methods on SIMPACE Data [12]

| Correction Method | Motion Parameters Used | Residual Noise Reduction (1× motion) | Residual Noise Reduction (2× motion) | Computational Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VOLMOCO (Volume-based) | 6 Vol-mopa + PV regressors | Baseline | Baseline | Fastest |

| Original SLOMOCO | 14 voxel-wise regressors | 12% improvement | 14% improvement | Moderate |

| Modified SLOMOCO | 12 Vol-/Sli-mopa + PV regressors | 29% improvement | 45% improvement | Longest |

| ICA-AROMA | Automated component removal | 22% improvement | 31% improvement | Fast-Moderate |

Visualization of Motion Correction Workflows

Motion Artifact Correction Pipeline

Multimodal Integration for Motion Resilience

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Motion Management in Neuroimaging Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Tracking Hardware | Camera-based systems (MRC Systems), inertial measurement units (IMUs), MR-compatible optical tracking | Real-time monitoring of subject movement | Compatibility with imaging environment, sampling rate, accuracy |

| Post-Processing Software | FSL (MCFLIRT), SPM, AFNI, SLOMOCO, ICA-AROMA | Retrospective motion correction and artifact removal | Compatibility with data format, computational demands, ease of use |

| Phantom Systems | SIMPACE-compatible phantoms, custom motion platforms | Validation and optimization of correction methods | Reproducibility of motion patterns, tissue-like properties |

| Multimodal Integration Platforms | NIRS-KIT, Homer2, NIRS-ICA, SPM-fNIRS | Co-registration and joint analysis of multiple data modalities | Data synchronization, coordinate system alignment |

| Reference-Based Noise Correction | ECG, respiratory belt, carbon wire loops, component-based noise correction (CompCor) | Identification and removal of physiological noise | Signal quality, temporal precision relative to imaging data |

| Accelerated Imaging Sequences | Multiband fMRI, compressed sensing, parallel imaging | Reduction of acquisition time to minimize motion window | Signal-to-noise tradeoffs, hardware requirements |

| Motion-Resistant Acquisition | PROPELLER, radial, spiral k-space trajectories | inherently motion-resistant data acquisition | Reconstruction complexity, sequence availability |

Core Problem: How Motion Artifacts Compromise Neuroimaging Data Integrity

Motion artifacts introduce non-neuronal noise that systematically biases neuroimaging data, leading to false conclusions about brain function and connectivity. Even minor, unavoidable movements—from breathing, cardiac cycles, or small head shifts—generate signal changes that can mimic, mask, or distort true neural activity. In functional MRI (fMRI), these artifacts are particularly problematic because the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal changes reflecting neural activity are very small (typically 1–2%), making them highly susceptible to contamination by motion-induced noise [17] [22]. This contamination manifests as two primary threats to data integrity: signal loss (reduced sensitivity to detect true effects) and spurious findings (increased false positives in connectivity and activation maps).

The fundamental challenge is that motion artifacts are not random noise. They introduce spatiotemporally structured patterns that can be misinterpreted as biologically plausible neural processes. For instance, studies have shown that motion artifacts can create spatial patterns that resemble the brain's default mode network—a key resting-state network—during functional connectivity analysis [17] [22]. This occurs because motion often causes signal changes at tissue boundaries (e.g., at the borders between gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid), creating structured artifacts that confound statistical analyses [10].

Table 1: Primary Motion Artifact Types and Their Direct Impacts on Data

| Artifact Type | Primary Cause | Impact on Data Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Ghosting/Blurring | Periodic motion (respiration, cardiac pulse) [23] | Reduces spatial accuracy; creates false replicas of anatomy [10] |

| Spin History Effects | Movement altering proton excitation history [12] | Causes local signal loss or gain that mimics activation/deactivation [12] |

| Magnetic Field Distortions | Head movement in B0 field [24] [12] | Introduces geometric distortions and voxel misplacement [12] |

| Physiological Noise | Cardiorespiratory cycles, blood flow [17] | Creates periodic signal changes that confound connectivity analyses [17] |

Quantitative Impacts: From Signal Loss to Spurious Connectivity

The consequences of motion are quantifiable and severe. In fMRI, head motion has been identified as one of the main sources of bias, with residual motion artifacts persisting even after standard correction procedures [12]. The impact is particularly pronounced in studies requiring high precision, such as cortical thickness measurements, where motion can create the false appearance of cortical thinning, mimicking disease-related atrophy [25].

The relationship between motion severity and data corruption follows a dose-response pattern. For example:

- In diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), longer acquisition times (4-5 minutes for 20-60 gradient directions vs. 2 minutes for 3 directions) significantly increase sensitivity to motion, resulting in misaligned data and introduced noise that compromises fiber tracking reliability [17] [22].

- In functional connectivity analyses, motion artifacts induce spurious correlations between brain regions that do not actually share functional relationships. This occurs because motion affects different brain regions in a coordinated manner, creating the illusion of connected networks [17].

- In activation maps for task-based fMRI, motion-related signal changes may accidentally correlate with the task timing, leading to false positive activations. Conversely, motion can also mask true activations, resulting in false negatives [22].

Table 2: Impact of Motion on Different Neuroimaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Key Vulnerability | Consequence for Data Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Resting-State fMRI | Low signal-to-noise ratio; sensitive to slow drifts [17] [22] | Spurious functional connectivity; corrupted network maps [17] [26] |

| Task-Based fMRI | Temporal correlation with task design [22] | False positive/negative activation; biased group comparisons [22] |

| Diffusion MRI (DTI) | Long acquisition times; sensitivity to misalignment [17] | Inaccurate fiber tracking; compromised white matter integrity measures [17] |

| Structural MRI (T1-weighted) | High spatial resolution demands [25] | Compromised cortical surface reconstructions; inaccurate volumetry [25] |

| Simultaneous EEG-fMRI | Electromagnetic induction from motion [24] | Neuronal signals masked by imaging/ballistocardiogram artifacts [24] |

Diagram 1: Motion artifact impact pathway on data integrity.

Methodological Guide: Motion Mitigation Protocols

Acquisition-Based Prevention Strategies

Participant Preparation and Positioning: Meticulous attention to participant comfort and stabilization is the first line of defense. Use vacuum cushions and adjustable head restraints to minimize head movement. Provide clear instructions about the importance of staying still, and consider practice sessions in a mock scanner to acclimatize participants. For special populations (children, patients with movement disorders), appropriate sedation or anesthesia may be necessary [23].

Sequence Optimization and Hardware Selection: Implement fast imaging sequences (e.g., gradient echo, multiband EPI) to reduce acquisition time and motion probability [10] [22]. Utilize cardiac gating for pulsation artifacts and breath-hold timing or respiratory triggering for abdominal/chest imaging [23]. Higher channel count phased-array coils improve signal-to-noise ratio, potentially mitigating some motion effects [17]. For EEG-fMRI simultaneously, consider carbon-wire loop systems to specifically capture MR-induced artifacts for later removal [24].

Prospective Motion Correction: These real-time approaches adjust the imaging plane during acquisition based on detected motion. Optical tracking systems monitor head position and orientation, while navigator echoes or real-time image registration can be embedded in sequences to prospectively correct for motion [12]. The SIMPACE (simulated prospective acquisition correction) sequence represents an advanced approach that alters the imaging plane coordinates before each volume and slice acquisition to emulate motion-free conditions [12].

Post-Processing Correction Techniques

Volume-Based Registration: The most common retrospective correction method involves 3D rigid body transformation with six parameters (three translational, three rotational) to realign each volume to a reference volume [22] [12]. While essential, this approach alone is insufficient as it cannot address spin history effects or intravolume motion [12].

Slice-Level Correction: Advanced methods like SLOMOCO (slice-oriented motion correction) address intravolume motion by applying slice-wise rigid motion parameters, significantly outperforming volume-based methods alone. As demonstrated in studies using the SIMPACE sequence, combining volume-wise and slice-wise motion parameters with partial volume regressors reduced residual motion artifacts by 29-45% compared to traditional approaches [12].

Nuisance Regression and Data Cleaning: After motion correction, residual motion artifacts must be addressed through nuisance regression. This includes:

- Expanding motion parameters (including temporal derivatives and squared terms) to capture nonlinear relationships [12]

- Implementing spike regression (or "scrubbing") to remove severely motion-corrupted volumes [12]

- Incorporating tissue-based regressors (white matter and CSF signals) to remove non-neuronal signals [12]

- Applying data-driven approaches like ICA-AROMA to automatically identify and remove motion-related components [24]

Diagram 2: Motion mitigation protocol workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Motion Management

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SIMPACE Sequence | Simulates motion-corrupted data by altering imaging plane coordinates [12] | Method validation; algorithm testing |

| SLOMOCO Pipeline | Implements slice-wise motion correction for intravolume motion [12] | fMRI preprocessing; motion correction |

| 3D CNN Correction | Deep learning approach for retrospective motion correction in structural MRI [25] | T1-weighted image enhancement |

| Carbon-Wire Loops (CWL) | Reference system capturing MR-induced artifacts in EEG-fMRI [24] | Artifact removal in simultaneous EEG-fMRI |

| WCBSI Algorithm | Combined wavelet and correlation-based signal improvement for fNIRS [27] | Motion artifact correction in fNIRS data |

| Point-Process Analysis | Sparse representation of BOLD signals as discrete events [26] | Dimensionality reduction; noise filtering |

| Rigid Body Transformation | Six-parameter (3 translation, 3 rotation) volume realignment [22] | Standard motion correction across modalities |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our group comparisons show significant cognitive network differences, but motion was greater in our patient group. Are these results valid? This is a critical confound. Motion artifacts can create spurious group differences that mimic disease effects. You must:

- Quantify motion metrics (mean framewise displacement, DVARS) for both groups [22]

- Include motion as a covariate in group analyses

- Consider implementing matched motion between groups through subgroup selection

- Apply rigorous motion correction (slice-level correction + nuisance regression) [12] Without these steps, your network differences may reflect motion artifacts rather than true neural effects.

Q2: We're studying a population with inherent movement disorders. What acquisition strategies are most effective? Prioritize fast acquisition sequences to minimize motion probability [10]. Consider:

- Multiband EPI for reduced scan times

- Prospective motion correction (PACE) if available [12]

- Smaller voxel sizes can sometimes reduce spin history effects

- For structural imaging, use sequences less sensitive to motion (e.g., MP-RAGE) Always acquire multiple runs to ensure some usable data if others are severely corrupted.

Q3: After volume realignment, why do we still see motion artifacts in our connectivity matrices? Volume-based correction alone cannot address spin history effects or intravolume motion [12]. The signal changes from these artifacts persist as structured noise. Implement:

- Slice-level motion correction (e.g., SLOMOCO) [12]

- Additional nuisance regression using:

- Expanded motion parameters (including derivatives and squares)

- Tissue-based regressors (white matter, CSF signals)

- Spike regression for severely corrupted volumes

- Data-driven approaches like ICA-AROMA

Q4: How does motion specifically create spurious functional connectivity? Motion creates coordinated signal changes across the brain that are not neuronal in origin. Specifically:

- Motion affects signal intensity most prominently at tissue boundaries [10]

- These signal changes occur simultaneously across distant brain regions

- Standard correlation metrics interpret these coordinated artifacts as "functional connections"

- The resulting patterns can resemble biologically plausible networks like the default mode network [17] [22]

Q5: For cortical thickness analysis, how much motion is acceptable before data should be excluded? There's no universal threshold, but studies show that even subtle motion can compromise cortical surface reconstructions [25]. Implement quality control metrics such as:

- Quantitative image quality metrics (e.g., CNR, SNR)

- Visual inspection for gray-white boundary integrity

- Cortical surface reconstruction success rates Consider deep learning-based correction methods, which have shown success in recovering usable data from motion-corrupted structural scans [25].

The Correction Toolbox: Proven and Novel Mitigation Strategies

FAQs: Addressing Motion Artifacts in Neuroimaging Research

1. What are the most common causes of motion artifacts in neuroimaging? Motion artifacts are primarily caused by subject movement during the scan. This includes gross involuntary movements, but also physiological motion from cardiac pulsation, respiration, and tremors. In the context of behavioral tasks, even small movements like button presses can introduce artifacts that degrade image quality [10].

2. Why is neuroimaging particularly sensitive to patient motion? Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is highly sensitive to motion because it requires a long time to collect sufficient data to form an image. This acquisition time is often far longer than the timescale of most physiological motions. The process of spatial encoding in k-space means that even small, transient movements can cause inconsistencies in the data, resulting in blurring, ghosting, or signal loss in the final image [10].

3. How can we proactively manage patient anxiety to reduce motion? Non-pharmacological interventions are the first line of defense. Creating a calm environment by minimizing noise and light is recommended. Furthermore, providing patients with clear information about the scanning procedure can reduce anxiety. For some patients, relaxation techniques or music therapy may be effective [28].

4. When is sedation considered, and what are the current best practices? Sedation may be necessary for patients who cannot remain still, such as certain pediatric populations or patients with conditions that cause involuntary movements. Recent 2025 clinical practice guidelines from the Society of Critical Care Medicine conditionally recommend using dexmedetomidine over propofol for sedation in adults, as it may promote more favorable outcomes. The guidelines strongly emphasize using the lightest effective level of sedation to keep patients more awake and alert, which is associated with better recovery [29] [28].

5. What are the key considerations for immobilization? While physical immobilization using head straps and padding is common and useful, it must be balanced with patient comfort. Discomfort from excessive restraint can itself lead to movement. The goal of immobilization is to minimize motion without causing stress or anxiety, which requires careful setup and communication with the patient [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Motion Artifacts

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Proactive Prevention Strategy | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghosting or replication of structures in the phase-encoding direction [10] | Periodic motion (e.g., respiration, cardiac pulsation) | Use prospective motion correction (MoCo) sequences or cardiac/respiratory gating where available [10]. | Consider re-acquiring the sequence with a different phase-encoding direction to change the artifact's orientation. |

| General blurring of image details [10] | Slow, continuous patient drift or gross involuntary movement | Optimize patient comfort with padding, use vacuum immobilization mats, and provide clear instructions on the importance of staying still. | Implement post-processing motion correction algorithms or use a sequence less sensitive to motion (e.g., single-shot EPI). |

| Signal loss in specific areas [10] | Spin dephasing due to movement during diffusion-sensitizing gradients or other contrast preparation. | Ensure secure head immobilization and consider sedation protocols for at-risk populations [29] [28]. | Re-scan with a reduced echo time (TE) or a sequence with reduced motion sensitivity, if diagnostically acceptable. |

| Anxiety and agitation in the scanner, leading to motion | Claustrophobia, scanner noise, or underlying medical condition. | Conduct a pre-scan rehearsal, use a mirror for visual exit, provide earplugs/headphones, and employ non-pharmacological anxiety reduction techniques [28]. | Follow institutional sedation protocols, which may include short-acting agents like dexmedetomidine [29] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Motion Mitigation

Protocol 1: Pre-Scan Patient Preparation and Comfort Optimization

Objective: To minimize motion at its source by reducing patient anxiety and maximizing physical comfort.

- Screening and Communication: Prior to the scan, screen patients for claustrophobia and anxiety. Explain the entire procedure, including the sounds and duration, and emphasize the critical importance of remaining still.

- Immobilization Setup: Use comfortable but firm foam padding around the patient's head within the head coil. Secure the head with a strap without causing discomfort.

- Environmental Adjustments: Offer the patient earplugs or noise-canceling headphones to reduce acoustic noise. Ensure the scanner bore is well-ventilated. For longer scans, consider placing a mirror to give the patient a view outside the bore.

- Task Practice: If the session involves a behavioral task, have the patient practice the task outside the scanner to build familiarity and reduce movement associated with task uncertainty [30].

Protocol 2: Implementation of Sedation for Motion-Prone Populations

Objective: To safely administer sedation to ensure scan viability in patients who cannot otherwise remain still. Note: This protocol must be conducted by qualified medical personnel following institutional regulations.

- Patient Selection and Assessment: Identify patients requiring sedation (e.g., young children, patients with movement disorders). Obtain informed consent and perform a pre-sedation health assessment.

- Sedation Protocol: Based on the latest 2025 guidelines, a protocol using Dexmedetomidine is preferred for its sedative and analgesic properties with a lower delirium risk profile compared to other sedatives [29] [28].

- Loading Dose: Administer 0.5–1 mcg/kg over 10 minutes.

- Maintenance Infusion: Titrate between 0.2–1 mcg/kg/hr to achieve a light sedation level where the patient is sleepy but rousable.

- Monitoring: Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation) throughout the scan. Use capnography if available.

- Recovery: Monitor the patient in a dedicated recovery area until standard discharge criteria are met.

Research Reagent Solutions for Motion Management

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Dexmedetomidine | A sedative and analgesic used in research protocols to facilitate motion-free scanning in awake or lightly sedated subjects, valued for its minimal impact on respiratory drive [29]. |

| Foam Padding & Vacuum Immobilization Mats | Essential non-invasive tools for comfortably stabilizing the subject's head and body within the scanner, reducing motion from muscle relaxation and discomfort. |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) Cap with Motion Sensors | Integrated systems (e.g., with accelerometers) used to quantitatively measure head motion in real-time, providing data for prospective or retrospective motion correction algorithms [31]. |

| Multi-dimensional Experience Sampling (mDES) | A validated questionnaire battery administered to subjects during task performance to collect introspective reports on psychological state, which can be correlated with motion-prone brain states [32]. |

| Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A class of deep learning models that can be trained to automatically rate motion artifacts in neuroimages, enabling rapid quality control of large datasets [33]. |

Workflow for a Proactive Motion Prevention Strategy

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for implementing a comprehensive strategy to prevent motion artifacts, integrating comfort, immobilization, and sedation.

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: FAQ on Acquisition-Based Motion Reduction

Q1: What are the primary acquisition-based strategies for mitigating motion artifacts in MRI? The main strategies can be categorized into three groups: (1) Prospective Motion Correction, which actively adjusts the imaging sequence in real-time based on detected motion (e.g., using navigator echoes or external tracking systems); (2) Gating, which acquires data only during specific phases of a periodic motion (e.g., cardiac or respiratory cycle); and (3) Ultrafast Imaging, which uses very short acquisition times to "freeze" motion [34] [35].

Q2: When should I use navigator echoes versus external optical tracking for prospective motion correction? The choice depends on your experimental needs. Navigator echoes are integrated into the pulse sequence and do not require additional hardware; they are particularly well-suited for tracking periodic motions like diaphragm movement during respiration [36]. External optical motion tracking systems use a camera to track markers placed on the subject, correcting for arbitrary rigid-body motion. They are ideal for imaging freely moving objects or for neuroimaging studies where even small head movements can degrade image quality [37].

Q3: My cardiac-triggered coronary artery images still show blurring. What gating parameter should I check? This is often due to respiratory motion. You should implement respiratory gating in addition to cardiac triggering. Use a navigator echo placed on the right hemidiaphragm and set a narrow gating window (e.g., 5 mm). The scanner will only acquire data when the diaphragm position falls within this window, significantly reducing respiratory blurring. Be aware that this will reduce scanning efficiency and increase total scan time [36].

Q4: What is a major limitation of using a simple linear model for diaphragm-based correction of heart motion? Research using multiple navigators has shown that the relationship between diaphragm and heart motion is not perfectly linear and often exhibits patient-dependent hysteresis. This means that for the same diaphragm position, the actual position of the heart can differ between the inspiration and expiration phases. A simple linear model can therefore lead to residual motion artifacts; a more complex, calibrated model is recommended for high-precision applications [36].

Q5: For an uncooperative patient, should I use sedation or an ultrafast sequence? Whenever ethically and medically feasible, ultrafast sequences (e.g., HASTE, EPI) should be attempted first. These sequences can acquire images in 2-5 seconds, often fast enough to freeze bulk motion without the need for sedation, which simplifies clinical workflow and reduces patient risk [35].

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and parameters for the acquisition-based solutions discussed.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Motion Reduction Techniques

| Technique | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Primary Application Context | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Navigator Echo (for real-time gating) | Gating window of 5 mm provided reproducible image quality for coronary arteries [36]. | Respiratory motion compensation in cardiac imaging [36]. | Reduces gating efficiency (20-60%), increasing scan time [36]. |

| External Optical Motion Tracking | Enabled imaging of freely moving objects without motion-related artefacts [37]. | Prospective correction of arbitrary rigid body motion in neuroimaging [37]. | Requires additional external hardware and camera system setup [37]. |

| Ultrafast Sequences (e.g., HASTE, EPI) | Acquisition times of 2-5 seconds can freeze bulk motion [35]. | Imaging uncooperative patients or reducing specific artifacts (e.g., in abdominal imaging) [35]. | May have lower signal-to-noise ratio or contrast compared to conventional sequences [35]. |

| Deep CNN for Motion Rating | 100% acquisition-based accuracy on test set; 90.3% on generalization epilepsy dataset [33]. | Reference-free automated quality evaluation of MR images for motion artifact rating [33]. | Performance can drop (e.g., 63.6%) on data from different domains/scanners without adaptation [33]. |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Navigator Echo Implementation

| Parameter | Typical Value / Setting | Explanation and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Pencil Beam Diameter | ~25 mm [36] | Defines the spatial region being monitored. A larger diameter averages over a larger area. |

| Navigator Total Duration | ~20 ms [36] | Includes excitation, acquisition, and evaluation time. Determines how frequently motion can be sampled. |

| Displacement Accuracy | <1 mm [36] | The precision with which the navigator can detect position changes, achieved via sub-pixel interpolation. |

| Gating Window | 5 mm (example for coronary imaging) [36] | The range of motion within which data is accepted. A smaller window improves quality but lowers efficiency. |

| Gating Efficiency | 20% - 60% [36] | The percentage of accepted data acquisitions. Patient-dependent and inversely related to gating window tightness. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Navigator Echoes for Respiratory Gating

Objective: To integrate a navigator echo for respiratory gating in a cardiac-triggered 3D coronary MR angiography sequence to mitigate respiratory motion artifacts during free breathing.

Materials and Equipment:

- 1.5 T or 3 T whole body MRI scanner.

- ECG triggering equipment.

- The pulse sequence must support the integration of a navigator echo pulse.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Subject Setup: Position the subject in the scanner in a supine position. Attach the ECG electrodes for cardiac triggering.

- Localizer and Planning: Acquire standard survey scans (e.g., coronal, sagittal, transverse) to locate the heart and the diaphragm.

- Navigator Positioning: On a coronal localizer image, graphically position the pencil beam navigator so that it passes through the dome of the right hemidiaphragm, creating a clear lung-liver tissue interface [36]. The Fourier transform of the signal from this beam creates a "navigator profile" with a sharp edge.

- Sequence Integration: Integrate the navigator pulse into the coronary MRA sequence. A typical navigator pulse sequence (excitation, acquisition, and evaluation) has a duration of about 20 ms [36].

- Reference Acquisition: Before starting the main scan, acquire a reference navigator profile.

- Set Gating Parameters: Define the acceptance window (e.g., 5 mm). During scanning, the system will use a cross-correlation algorithm in real-time to compare each new navigator profile to the reference. Data is only accepted if the measured displacement of the diaphragm is within the specified 5 mm window [36].

- Data Acquisition: Start the ECG-triggered, segmented k-space 3D gradient echo sequence. The scanner will continuously monitor the diaphragm position and only acquire imaging data when the respiratory position is within the gating window.

- Monitoring: Monitor the "gating efficiency" (the percentage of accepted acquisitions) throughout the scan. Be prepared for longer total scan times, as efficiency can vary between 20% and 60% depending on the subject's breathing pattern [36].

Visual Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationship between the primary acquisition-based solutions for motion artifact reduction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential "research reagents" – the key hardware, software, and sequence components required for implementing the featured motion reduction techniques.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Motion Artifact Experiments

| Item Name / Solution | Category | Primary Function in Motion Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| 2D RF Pulse (Spiral Trajectory) | Pulse Sequence Component | Creates a spatially selective "pencil beam" for exciting the navigator echo, which is used to monitor tissue position [36]. |

| External Optical Motion Tracking System | Hardware | Tracks the position of markers placed on the subject in real-time, allowing the scanner to prospectively correct the imaging volume position prior to each excitation [37]. |

| ECG Triggering Device | Hardware | Detects the cardiac cycle (R-wave) to prospectively trigger the start of data acquisition during a specific, stable phase of the heart cycle (e.g., diastole) [34] [35]. |

| Respiratory Belt or Bellows | Hardware | Monitors the expansion and contraction of the chest wall for use in respiratory triggering or gating [35]. |

| Ultrafast Sequences (e.g., HASTE, EPI) | Pulse Sequence | Acquires images rapidly (in seconds or less) to minimize the time during which motion can occur, effectively "freezing" motion [35]. |

| Radial/Spiral k-space Trajectories | Pulse Sequence Design | Disperses motion artifacts throughout the image rather than concentrating them as discrete ghosts, which is common with Cartesian trajectories [35]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting ICA-AROMA for Task-Based fMRI

Problem 1: Poor Component Classification After Running ICA-AROMA

- Symptoms: The classifier fails to identify obvious motion-related components, or too many neural components are mistakenly flagged as noise.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect feature calculation due to misalignment between high-resolution brain extraction and functional data.

- Solution: Ensure the brain mask derived from your high-resolution structural image is accurately registered to your functional space. Visually inspect the overlap.

- Cause: The motion parameters used for feature extraction are not representative of the true head displacement.

- Solution: Verify the quality of your motion parameter estimation by plotting frame-wise displacement. Check for outliers or failed registrations.

- Cause: Unusual motion patterns that fall outside the classifier's trained feature space.

- Solution: Manually inspect the classified components. ICA-AROMA allows for manual intervention to override the automatic classification if necessary [20] [38].

Problem 2: Over-Aggressive Denoising Leading to Loss of Neural Signal

- Symptoms: A significant reduction in task-based activation, particularly in regions known to be susceptible to motion (e.g., prefrontal cortex).

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The threshold for the classifier's decision boundary is too sensitive for your specific dataset.

- Solution: While ICA-AROMA is largely automatic, some implementations allow for a "non-aggressive" denoising option. This regresses out the time courses of noise components rather than fully removing them, helping to preserve the variance of the signal of interest [20].

- Cause: The data has a very low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), making it difficult to distinguish motion from neural activity.

- Solution: This is a fundamental data quality issue. Consider acquiring more data points or using a multi-echo sequence to improve ICA component estimation in future studies.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Structured Low-Rank Matrix Completion

Problem 1: High Computational Demand and Memory Usage

- Symptoms: The algorithm runs very slowly or fails due to insufficient memory, especially with high-resolution datasets.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The constructed Hankel matrix is extremely large, leading to high computational complexity [39].

- Solution: The original paper proposes a variable splitting strategy to decouple the problem into simpler sub-problems. Ensure you are using an implementation that employs this or similar optimization (e.g., alternating direction method of multipliers) for memory efficiency [39].

- Cause: The data dimensions are too high.

- Solution: As a preprocessing step, consider modest spatial smoothing or down-sampling of the data, balancing the trade-off between resolution and computational feasibility.

Problem 2: Ineffective Recovery of Censored Time Points

- Symptoms: The recovered time series still shows clear discontinuities or introduces strange patterns at the censored time points.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The low-rank prior assumption is violated, which can happen if the motion is very severe and affects a large portion of the data.

- Solution: The method works best when the number of censored time points is not excessive. Increase the stringency of your motion censoring (scrubbing) to remove only the most severely corrupted volumes, leaving a sufficient number of "clean" time points for the matrix completion to work effectively [39].

- Cause: The linear recurrence relation (LRR) model order is inappropriate for your data.

- Solution: The window length

Lfor the Hankel matrix is a key parameter. Try adjusting this parameter, as an overestimated window length can lead to a higher-than-expected rank and poor performance [39].

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Wavelet-Based Filters

Problem 1: Signal Distortion Following Artifact Removal

- Symptoms: The denoised signal appears overly smoothed, and key features of the physiological signal (e.g., SCR peaks in EDA) are attenuated [40].

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The thresholding of wavelet coefficients is too aggressive, removing not only artifacts but also signal components of interest.

- Solution: The artifact proportion parameter

δcontrols the threshold. Reduce the value ofδto be more conservative in what is considered an artifact. Use adaptive thresholding that calculates thresholds within local time windows to account for dynamic changes in the signal amplitude [40]. - Cause: The choice of mother wavelet is not well-matched to the signal morphology.

- Solution: The Haar wavelet is often preferred for its edge-detection capabilities with motion artifacts. However, if your signal of interest has specific characteristics, testing other wavelets (e.g., Daubechies) might yield better results [40].

Problem 2: Residual Motion Artifacts Remain

- Symptoms: Clear spike artifacts are still visible in the data after filtering.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The artifact has a frequency profile that overlaps significantly with the signal of interest.

- Solution: This is a fundamental limitation. Consider a hybrid approach: first use a wavelet-based method to detect the location of artifacts, then use an interpolation method (like cubic spline) specifically for the identified contaminated segments, rather than relying solely on coefficient thresholding [40].

- Cause: The decomposition level of the stationary wavelet transform (SWT) is insufficient to isolate the artifact.

- Solution: Increase the number of decomposition levels (e.g., from 8 to 10) to ensure the artifact is captured in the detail coefficients where it can be effectively thresholded [40].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Under what conditions should I choose ICA-AROMA over a simpler motion regression model (e.g., 24-parameter model)?

ICA-AROMA is particularly advantageous when you are concerned about preserving the temporal degrees of freedom and autocorrelation structure of your data. Simple regression models remove motion-induced signal variations at the cost of destroying this autocorrelation, which can invalidate subsequent statistical tests. ICA-AROMA overcomes this drawback. Furthermore, it has been shown to remove motion-related noise to a larger extent than 24-parameter regression or spike regression and can increase sensitivity to group-level activation in both resting-state and task-based fMRI [20] [38].

FAQ 2: My research involves infant populations with frequent, large head movements. Which algorithm is most suitable?

For populations like infants who exhibit infrequent but large motions, a combination of strategies is often best. The JumpCor technique was specifically designed for this scenario. It identifies large "jumps" in motion and models separate baselines for the data segments between these jumps, effectively accounting for signal intensity changes caused by the head moving into a different part of the RF coil [41]. This can be combined with structured matrix completion to recover the censored time points, as this method has been validated to improve functional connectivity estimates even in the presence of large motions by exploiting the underlying structure of the fMRI time series [39] [41].

FAQ 3: How does structured low-rank matrix completion compare to simple interpolation for filling in censored ("scrubbed") volumes?

Simple interpolation (e.g., linear or spline) replaces missing data using only immediately adjacent time points, which can create smooth but unrealistic transitions and does not account for the global spatio-temporal structure of the brain's signals. In contrast, structured matrix completion uses a low-rank prior, formalized by constructing a Hankel matrix from the time series. This model leverages information from the entire dataset and across voxels to recover the missing entries in a physiologically more plausible way, leading to functional connectivity matrices with lower errors in pair-wise correlation compared to methods using only censoring and interpolation [39].

FAQ 4: Can wavelet-based filters be applied to real-time artifact correction?

The stationary wavelet transform (SWT), which is time-invariant and performs no down-sampling, is a prerequisite for any real-time application. Its structure makes it more suitable than the standard discrete wavelet transform (DWT). However, the adaptive thresholding step, which often involves estimating a Gaussian mixture model for the wavelet coefficients within a sliding window, can be computationally demanding. While promising for near-real-time applications, its true real-time capability depends on a highly optimized implementation that can perform the SWT and statistical estimation within the sampling interval of the acquired signal [40].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Featured Motion Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Modality | Key Performance Findings | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICA-AROMA [20] [38] | fMRI (Task & Resting-state) | Increased sensitivity to group-level activation; More effective motion removal than 24-parameter regression or spike regression. | Preserves temporal degrees of freedom (tDOF); No need for classifier re-training; Fully automatic. |

| Structured Matrix Completion [39] | rsfMRI | Resulted in functional connectivity matrices with lower errors in pair-wise correlation; Improved delineation of the default mode network. | Recovers censored data using global information; Also performs slice-timing correction. |

| Wavelet-Based Filter (SWT) [40] | EDA | Achieved >18 dB attenuation in motion artifact energy; Induced less than -16.7 dB distortion in artifact-free regions. | Adaptive thresholding retains valid signal; Effective for spike-like artifacts in continuous data. |

| JumpCor [41] | fMRI (Infant studies) | Significantly reduced motion-related signal changes from infrequent large motions; Improved functional connectivity estimates. | Specifically designed for large, discrete head "jumps"; Simple regression-based approach. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing ICA-AROMA for fMRI Preprocessing

This protocol outlines the steps to integrate ICA-AROMA into a standard fMRI preprocessing pipeline for motion artifact removal [20] [38].

- Standard Preprocessing: Begin with standard steps including slice-timing correction, realignment (motion correction), and spatial smoothing. Co-registration to a high-resolution structural image is also required.

- ICA-AROMA Execution:

- Input: The realigned (and optionally smoothed) 4D functional data and the corresponding motion parameters obtained from realignment.

- Process: Run the ICA-AROMA classifier. The algorithm performs:

- Melodic ICA: Decomposes the functional data into independent components.

- Feature Extraction: For each component, it calculates four robust features: high-frequency content, correlation with motion parameters, edge fraction (spatial), and CSF fraction (spatial).

- Classification: Uses these features to automatically classify components as either "motion" or "non-motion."

- Denoising: Regress out the time courses of the classified motion components from the original functional data. The "non-aggressive" method is recommended to preserve signal variance.

- Downstream Analysis: Proceed with standard analysis, such as general linear model (GLM) for task-fMRI or functional connectivity analysis for rs-fMRI, using the denoised data.

Protocol 2: Validating a Wavelet-Based Motion Filter for EDA Data

This protocol describes a method to validate the performance of a stationary wavelet transform (SWT) filter for removing motion artifacts from electrodermal activity (EDA) data [40].

- Data Collection & Labeling:

- Record EDA signals (e.g., skin conductance) alongside accelerometer data (actigraph) to provide an objective measure of movement.