Cross-Species Comparisons in Environmental Enrichment: From Foundational Biology to Improved Translational Research

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of cross-species comparisons in environmental enrichment studies.

Cross-Species Comparisons in Environmental Enrichment: From Foundational Biology to Improved Translational Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of cross-species comparisons in environmental enrichment studies. It explores the foundational principles of how conserved and divergent biological responses shape organismal adaptation to environmental changes. The content delivers practical methodological frameworks for designing and executing robust cross-species studies, including model selection tools like the Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) and FIMD. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as accounting for species-specific microbiomes and genomic responses. Finally, the article covers validation strategies and comparative analyses that enhance the predictive value of preclinical research, ultimately aiming to improve the translation of biological findings from model organisms to human clinical outcomes.

The Evolutionary and Biological Basis of Cross-Species Responses to Environment

Defining Environmental Enrichment and Stimuli Across Species

Environmental enrichment (EE) is an experimental paradigm used to explore how complex, stimulating environments impact overall health and physiology across diverse species [1]. In laboratory settings, EE introduces a variety of physical, social, cognitive, motor, and somatosensory stimuli that profoundly influence neurodevelopment, behavior, and physiological resilience [2] [1]. While the specific manifestations of EE vary significantly between mammals and plants, a common thread exists: the systematic manipulation of environmental factors to enhance adaptive capacities. This guide provides a comparative analysis of EE protocols, outcomes, and underlying mechanisms across animal and plant species, offering researchers a structured framework for designing cross-species enrichment studies.

The fundamental principle underlying EE is that brains in richer, more stimulating environments develop higher rates of synaptogenesis, more complex dendrite arbors, and increased brain activity, effects observed primarily during neurodevelopment but continuing throughout adulthood [2]. Similarly, plants exposed to optimized environmental conditions demonstrate enhanced stress resilience and growth efficiency [3]. This cross-species comparison reveals both conserved and lineage-specific responses to environmental complexity, providing critical insights for basic research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Experimental Protocols and Parameters

Environmental enrichment protocols vary substantially across species and research objectives. The table below systematizes key experimental parameters for cross-species comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Experimental Parameters in Environmental Enrichment Studies

| Parameter | Animal Models (Mammals) | Plant Models (Hydroponic Crops) |

|---|---|---|

| Housing System | Larger-than-standard cages with increased bedding [1] | Aspara Smart Grower Hydroponic Systems with controlled chambers [3] |

| Physical Stimuli | Toys, ladders, tunnels, running wheels, shelters rearranged regularly [2] [1] | Controlled light intensity (up to 300 μE), temperature regimes, mechanical stimulation [3] |

| Social Stimuli | Varied social networks with multiple conspecifics [1] | Co-cultivation limitations (monoculture standard) [3] |

| Nutritional Variables | Standardized chow with potential dietary manipulations [1] | Precise nutrient solutions (Half-strength Hoagland's) with specific N, P, K deficiencies [3] |

| Cognitive Stimuli | Mazes, novel object exploration, learning tasks [2] | Not applicable |

| Environmental Control | Temperature and humidity controlled rooms [1] | MT-313 Plant Growth Chamber or PGC-9 controlled environment chamber [3] |

| Key Outcome Measures | Cerebral cortex thickness, synapse count, behavioral tests, metabolic parameters [2] [1] | Fresh weight, transcriptomic profiling, photosynthetic efficiency, stress markers [3] |

| Experimental Timeline | Weeks to months, with effects observable within 2 weeks [1] | Days to weeks, with treatments applied at specific developmental stages [3] |

Quantitative Outcomes and Comparative Efficacy

The measurable impacts of environmental enrichment manifest across multiple physiological domains. The following table compares quantitative outcomes observed across species and experimental systems.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Environmental Enrichment Across Species

| Outcome Category | Animal Models (Quantitative Changes) | Plant Models (Quantitative Changes) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Changes | 3.3-7% thicker cerebral cortices; 25% more synapses; 12-14% more glial cells per neuron [2] | Not measured structurally; transcriptomic changes in 276 RNA-seq libraries [3] |

| Molecular Biomarkers | Increased BDNF, NGF, NT-3; upregulation of synaptophysin and PSD-95 [2] [1] | Shared downregulation of photosynthesis genes; upregulation of WRKY, AP2/ERF transcription factors [3] |

| Metabolic Parameters | Reduced weight gain despite increased food intake; improved glycemic control; reduced circulating leptin; increased adiponectin [1] | Significant fresh weight reduction under extreme temperatures and nutrient deficiencies [3] |

| Stress Resilience | Enhanced recovery from neurological insults; reduced anxiety/depression-like behaviors [2] [1] | Conserved stress-responsive gene regulatory networks across cai xin, lettuce, spinach [3] |

| Cross-Species Conservation | Conserved BDNF and neurotrophin pathways in mammals [2] [1] | Highly conserved gene regulatory networks (GRNs) spanning all three plant species [3] |

Methodological Toolkit for Cross-Species Enrichment Research

Experimental Workflow for Comparative Enrichment Studies

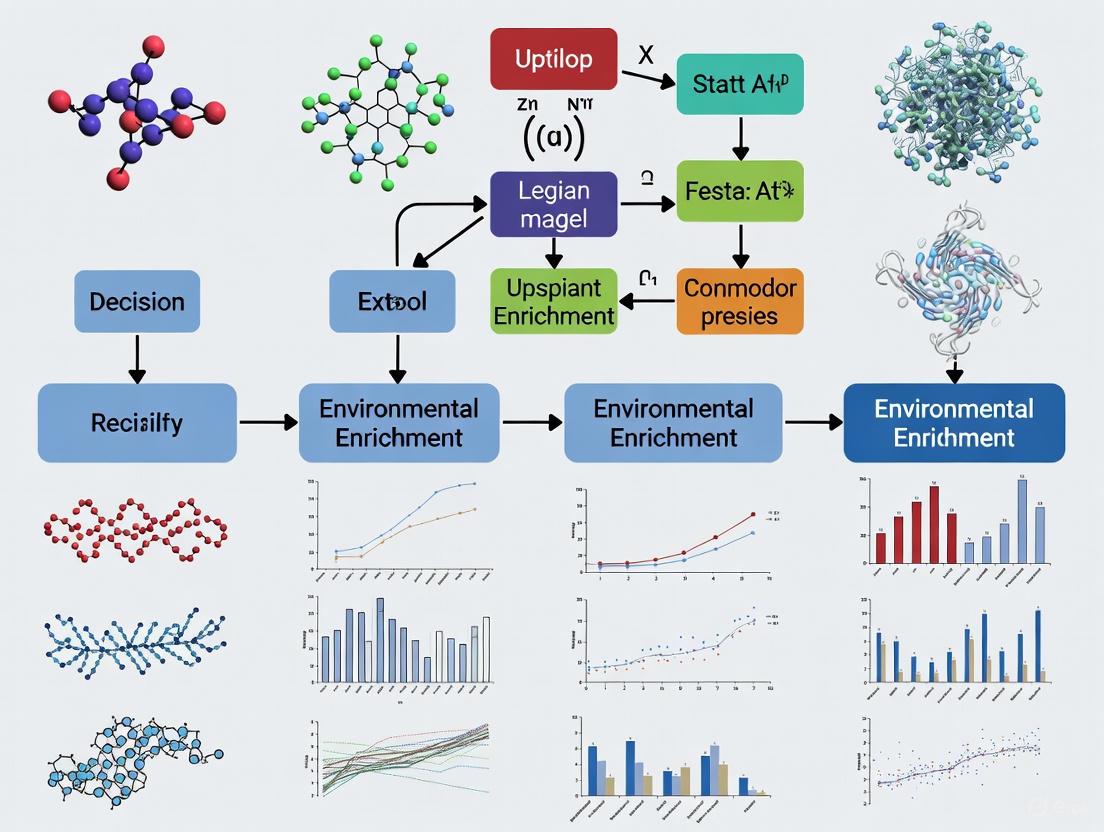

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow applicable to both animal and plant enrichment studies, highlighting parallel approaches across species:

Key Signaling Pathways in Environmental Enrichment

The molecular mechanisms underlying environmental enrichment responses involve conserved signaling pathways across species, albeit with lineage-specific components:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details critical research reagents and their functions in environmental enrichment studies across species:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Environmental Enrichment Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Function | Application Across Species |

|---|---|---|

| Hoagland's Solution | Provides essential macro/micronutrients for plant growth | Hydroponic plant studies (cai xin, lettuce, spinach) [3] |

| PowerFecal DNA Isolation Kit | Extracts high-quality microbial DNA from fecal samples | Gut microbiota analysis in pandas, bears, and other species [4] |

| 16S rRNA V4 Primers (515F/806R) | Amplifies bacterial 16S rRNA V4 region for microbiome analysis | Cross-species gut microbiota studies (giant pandas, red pandas, black bears) [4] |

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | Key neurotrophin mediating EE effects on neural plasticity | Mammalian studies of neurodevelopment, metabolism, and behavior [2] [1] |

| Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplifies DNA with high fidelity for sequencing applications | Microbial community analysis in cross-species comparisons [4] |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kits | Transcriptomic profiling of gene expression changes | Cross-species analysis of stress responses (plants and animals) [3] |

| Illumina NovaSeq Platform | High-throughput sequencing for genomic/transcriptomic analysis | 16S rRNA sequencing and RNA-seq in diverse species [3] [4] |

Discussion: Integration of Cross-Species Findings

The comparative analysis of environmental enrichment across species reveals both conserved principles and taxon-specific adaptations. In mammalian systems, EE consistently induces structural and functional changes in the brain, including increased cortical thickness, synaptogenesis, and enhanced cognitive function [2]. These changes are mediated through evolutionarily conserved molecular pathways involving neurotrophins like BDNF, which also regulates systemic metabolic effects through the hypothalamic-sympthoneural-adipocyte axis [1].

Plant systems demonstrate analogous responses to environmental complexity, though manifested through different mechanisms. While lacking neural structures, plants exhibit sophisticated transcriptomic reprogramming in response to environmental stimuli, engaging transcription factor families including WRKY and AP2/ERF that show conservation across diverse plant species [3]. This parallel suggests that principles of environmental enrichment may operate across biological kingdoms, albeit through lineage-specific mechanisms.

A particularly compelling convergence emerges in studies of captivity effects across species. Research on giant pandas, red pandas, and Asiatic black bears reveals that captive environments significantly reshape gut microbiota communities, with environmental factors explaining 21.6% of community variance compared to 12.3% for host phylogeny and only 3.9% for diet [4]. This highlights the profound impact of environmental complexity on fundamental physiological processes across mammalian species.

These cross-species patterns offer valuable insights for designing more effective enrichment protocols in research and practical applications. The conserved responses to environmental complexity suggest fundamental biological principles that transcend phylogenetic boundaries, providing a unified framework for understanding how organisms perceive and adapt to their environments across the tree of life.

The comparative study of biological systems across species reveals a fundamental duality: deeply conserved core principles exist alongside extensive divergent adaptations. This evolutionary "toolkit" – comprising conserved genes, regulatory modules, and cellular processes with lineage-specific variations – enables both remarkable stability and innovative diversification in biological systems [5]. Understanding these conserved and divergent elements is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals, as it allows for strategic extrapolation from model systems while highlighting species-specific particularities that critically impact therapeutic outcomes.

Cross-species comparisons in environmental enrichment studies provide a powerful lens through which to examine these principles. These investigations demonstrate how conserved neurobiological mechanisms respond to environmental stimuli across evolutionary timescales, revealing both universal response patterns and species-specific adaptations. This article systematically compares conserved and divergent biological systems by synthesizing experimental data from transcriptomic, epigenomic, and behavioral studies across multiple species, providing a framework for understanding evolutionary toolkits in biomedical research.

Comparative Tables: Conserved Versus Divergent Biological Systems

Table 1: Levels of Biological Conservation and Divergence Across Species

| Biological Level | Conserved Elements | Divergent Elements | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Regulation | Core transcriptional regulatory syntax [6]; RGATTYY motif in plant GLK transcription factors [7] | Species-specific cis-regulatory elements (80% human-specific in cortical cells) [6]; Widespread TF binding site divergence [7] | Single-cell multiomics in motor cortex (human, macaque, marmoset, mouse) [6]; ChIP-seq in 5 plant species [7] |

| Immune Cell Identity | Universal genes defining immune cell types across vertebrates [8]; Monocyte conserved transcriptional program [8] | Cellular composition differences in PBMCs across species [8] | scRNA-seq of PBMCs across 12 vertebrate species [8] |

| Neural Plasticity | Adult hippocampal neurogenesis persistence [9]; Environmental enrichment enhances neurogenesis [9] [10] | Neurogenesis rate differences; Response magnitude to enrichment [9] | Rodent environmental enrichment studies; Human postmortem brain analysis [9] |

| Brain Structure | Planar polarity in hair cells [11] | Specialized polarity patterns in auditory vs. vestibular systems [11] | Inner ear anatomical and functional analysis [11] |

| Behavioral Response | Social challenge transcriptional responses [5] | Timing and anatomical specificity of response [5] | Brain transcriptomics after social challenge (honey bees, mice, stickleback fish) [5] |

Table 2: Environmental Enrichment Effects on Motor Performance in Mice

| Behavioral Test | Standard-Housed Performance | Enriched-Housed Performance | Statistical Significance | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyeblink Conditioning (CR timing precision) | Less precise conditioned response timing [12] | Improved peak timing of conditioned responses [12] | Significant (p<0.05) [12] | Enhanced cerebellar-dependent motor learning |

| Accelerating Rotarod | Lower latency to fall [12] | Superior performance (longer latency to fall) [12] | Significant (p<0.05) [12] | Improved motor coordination and fitness |

| ErasmusLadder Test | Reduced performance efficiency [12] | Improved motor performance [12] | Significant (p<0.05) [12] | Enhanced complex motor coordination |

| Open Field (Roaming Entropy) | Higher roaming entropy [10] | Lower roaming entropy with greater inter-individual variance [10] | Significant (p<0.05) [10] | Altered exploratory patterns and increased individualization |

| Novel Object Exploration | Consistent duration across individuals [10] | Higher variance in exploration duration [10] | Significant (p<0.05) [10] | Increased behavioral individuality |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cross-Species Single-Cell Transcriptomics of Immune Cells

The comprehensive analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) across 12 vertebrate species provides a protocol for identifying conserved immune principles [8]:

Cell Collection and Preparation: PBMCs were isolated from peripheral blood using density gradient centrifugation. Cell viability was assessed via 0.4% trypan blue staining, with only samples exceeding 85% viability processed for sequencing.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Cells were loaded onto BMKMANU chips with BMKMANU DG1000 Library Construction Kits. Libraries were fragmented and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Raw reads were aligned to respective reference genomes using BSCMATRIX with default parameters.

Data Processing and Quality Control: The gene expression matrix was processed in R (version 4.2.2) using Seurat (version 4.3.0) with standard workflow (SCTransform, RunPCA, RunUMAP, FindNeighbors, FindClusters). DoubletFinder (version 2.0.3) evaluated doublets, with low-quality cells (fewer than 300 detected genes) removed. Mitochondrial gene content thresholds were species-specific (20% for chicken, pig, cattle; 10% for mouse, rat).

Cross-Species Integration: Orthologous genes were uniformly converted to human gene symbols using Ensembl 109 and OrthoFinder (version 2.5.5). Harmony (version 1.0) achieved the highest integration scores and was used for batch effect correction.

Cell Type Annotation: For humans and mice, SingleR (version 2.0.0) and scType enabled automatic annotation, manually corrected using marker genes from CellMarker 2.0. For other species, conserved orthologous marker genes defined cell types, verified through Gene Ontology enrichment analysis.

Environmental Enrichment and Neurogenesis Studies

The systematic review of environmental enrichment effects on hippocampal neurogenesis synthesized 32 studies with original data [9]:

Enrichment Models: Various spatial complexity models were evaluated, including environmental enrichment setups, in-cage element changes, complex layouts, and navigational mazes featuring novelty and intermittent complexity.

Regression Analysis: A regression equation synthesized key factors influencing neurogenesis: duration, physical activity, frequency of changes, diversity of complexity, age, living space size, and temperature.

Neurogenesis Assessment: Studies employed bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling for cell birth dating, immunohistochemistry for neuronal markers (NeuN, DCX), and confocal microscopy for structural analysis.

Behavioral Correlation: Behavioral tests including open field, novel object recognition, and pattern separation tasks correlated with neurogenesis measures.

Cross-Species Translation: Existing equations relating rodent and human ages enabled translation of enrichment protocol durations, with environmental complexity metrics adapted for human architectural and urban design analysis.

Analysis of Inter-Individual Variability in Response to Enrichment

This protocol specifically addressed whether environmental enrichment increases individuality in brain and behavior [10]:

Subjects and Housing: 40 isogenic female C57BL/6JRj mice per group were randomly assigned to enriched environment (ENR) or control cages (CTRL) for 105 days. The ENR featured social complexity (40 mice together), large compartmentalized enclosure size, and physical complexity.

Behavioral Testing: All mice underwent open field (OF), novel object recognition (NOR), and rotarod tests. Roaming entropy was computed as a measure of territorial coverage and exploratory activity.

Biological Measures: Adult hippocampal neurogenesis was quantified via immunohistochemistry. Motor cortex thickness was measured histologically. Metabolic parameters were tracked throughout.

Variance Analysis: Differences in variance between ENR and CTRL groups were systematically analyzed for 28 morphological, behavioral, and metabolic variables using appropriate statistical tests for variance comparison.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Environmental Enrichment-Induced Neuroplasticity Pathway

Diagram 1: Environmental enrichment activates conserved molecular pathways that enhance neuroplasticity. Key nodes include physical activity (PA), spatial complexity novelty (SCN), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), CREB signaling, adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN), cortical plasticity (CORT), memory function (MEM), and anxiety behavior (ANX).

Transcriptional Regulation of Conserved and Divergent Genes

Diagram 2: Evolutionary dynamics of gene regulation. While transcription factor binding motifs are often conserved, cis-regulatory elements diverge through transposable element insertion and sequence changes, enabling species-specific gene expression patterns from conserved regulatory frameworks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cross-Species Comparative Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Application | Conservation Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Gene expression profiling at single-cell resolution | PBMC analysis across 12 species [8]; Motor cortex comparison in 4 mammals [6] | High (protocols applicable across vertebrates) |

| Harmony integration | Batch effect correction in single-cell data | Integration of cross-species transcriptomic datasets [8] | High (algorithm robust across diverse datasets) |

| OrthoFinder | Ortholog prediction across species | Identification of one-to-one orthologous gene pairs [8] | High (widely applicable across eukaryotes) |

| Anti-BrdU antibodies | Cell proliferation labeling | Quantifying adult hippocampal neurogenesis [9] [10] | Medium (species-specific antibody validation needed) |

| Cell type-specific markers | Immune cell identification | Annotation of PBMC clusters across species [8] | Variable (some markers conserved, others species-specific) |

| 10x Multiome | Simultaneous gene expression and chromatin accessibility | Epigenomic profiling in motor cortex [6] | High (protocols standardized across mammals) |

| ChIP-seq protocols | Transcription factor binding site mapping | GLK TF binding in 5 plant species [7] | Medium (requires optimization per species/TF) |

| PhastCons scores | Sequence conservation quantification | Identifying evolutionarily constrained elements [6] | High (genome-wide comparative genomics) |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Drug Development

The conserved principles and divergent adaptations observed across species have profound implications for research and therapeutic development. Evolutionary toolkits comprising conserved genetic programs enable extrapolation from model systems while necessitating careful consideration of species-specific adaptations [5] [13].

In neuroscience research, environmental enrichment studies demonstrate that while the principle of experience-dependent neuroplasticity is conserved, the magnitude and specificity of response shows significant cross-species and inter-individual variation [9] [10] [12]. This highlights the importance of accounting for environmental history in experimental design and interpretation.

For immunology and inflammation research, the identification of universal immune genes alongside species-specific cellular compositions suggests that some inflammatory pathways may be reliably modeled across species, while others require careful validation in the target species [8].

In drug development, understanding conserved regulatory syntax alongside species-specific cis-regulatory elements is crucial for predicting off-target effects and translational success [6]. The presence of human-specific regulatory elements discovered through cross-species epigenomic comparison underscores the limitations of relying exclusively on rodent models.

The systematic comparison of biological systems across evolutionary timescales provides an powerful framework for distinguishing fundamental mechanisms from lineage-specific adaptations, ultimately enhancing the predictive validity of experimental models and accelerating therapeutic development.

The gut microbiota, often called the "second genome" of animals, plays a pivotal role in host nutrient metabolism, immune modulation, and environmental adaptation [14] [4]. In captive wildlife, significant environmental changes can profoundly reshape microbial communities, potentially affecting animal health and conservation outcomes. This case study examines captivity-induced microbiota reshaping in three endangered ursids: the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), red panda (Ailurus fulgens), and Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus). These species provide a unique comparative model due to their divergent dietary specializations (bamboo specialists versus omnivore) within overlapping habitats and captive management conditions [14]. Understanding these microbial shifts is critical for improving captive husbandry and enhancing reintroduction success for endangered species.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Diversity and Composition

Alpha Diversity Patterns Across Species

The effect of captivity on gut microbial diversity (alpha-diversity) demonstrates species-specific responses rather than a universal pattern, as revealed by 16S rRNA V4 sequencing of fecal samples [14] [4].

Table 1: Alpha-diversity Responses to Captivity Across Species

| Species | Alpha-Diversity Change | Statistical Significance | Noteworthy Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giant Panda | Significantly reduced | P < 0.05 | Contrasts with general mammalian pattern; linked to specialized bamboo diet |

| Red Panda | Significantly increased | P < 0.05 | Occurs despite phylogenetic distinction from giant panda |

| Asiatic Black Bear | Significantly increased | P < 0.05 | Aligns with some omnivorous species in captivity |

These divergent responses highlight that captivity does not systematically decrease or increase gut microbial diversity across vertebrates, a finding consistent with broader meta-analyses encompassing 24 vertebrate species [15]. The heterogeneity suggests that intrinsic host factors combined with specific captive management practices drive these differences rather than a universal captivity effect.

Beta-Diversity and Community Restructuring

Weighted UniFrac-based β-diversity analysis revealed that intra-species distances between captive and wild individuals exceeded those observed between different species within the same habitat (P < 0.001) [14] [4]. This indicates profound community restructuring under captivity that transcends species boundaries. Statistical analysis using PERMANOVA quantified the relative contributions of different factors to microbial community variance:

- Environment (captive vs. wild): 21.6% of variance (F = 23.62)

- Host phylogeny: 12.3% of variance (F = 6.75)

- Diet: 3.9% of variance (F = 4.32) [14] [4]

These results demonstrate that captive management is the primary determinant of gut microbiota divergence, exerting a stronger influence than host evolutionary history or dietary specialization.

Phylogenetic and Genus-Level Taxonomic Shifts

Table 2: Phylum and Genus Level Microbial Shifts in Captivity

| Taxonomic Level | Wild Populations | Captive Populations | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum Level | Proteobacteria dominance (81.2 ± 17.6%) | Firmicutes dominance (68.6 ± 23.0%) | Shift from complex plant degraders to sugar/fermenters |

| Giant Panda (Genus) | Predominantly Pseudomonas | Enrichment of Streptococcus and Escherichia-Shigella | Loss of fiber-digestion capability |

| Red Panda (Genus) | Wild-specific composition | Enrichment of Streptococcus and Escherichia-Shigella | Similar pattern to giant pandas despite phylogenetic distance |

| Asiatic Black Bear (Genus) | Predominantly Burkholderia | Enrichment of Sarcina | Shift in metabolic functions |

The enrichment of Streptococcus and Escherichia-Shigella in captive pandas is particularly concerning, as these bacteria have been associated with health issues when abundant, including respiratory problems, pneumonia, and lethargy in black bears [16]. These compositional changes reflect a convergence of gut microbial communities among the three species in captivity, despite their distinct microbial profiles in wild habitats [16] [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Collection and Preservation

The comparative analysis employed a stratified sampling design with specific protocols to ensure data reliability:

- Captive specimens: Giant pandas (n = 10) from China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda; red pandas (n = 8) and Asiatic black bears (n = 6) from Bifengxia Ecological Zoo [4]

- Wild specimens: Giant pandas (n = 16) and red pandas (n = 16) from Fengtongzhai National Nature Reserve; Asiatic black bears (n = 17) from Fengtongzhai and Tangjiahe National Nature Reserves [4]

- Temporal control: All fecal samples collected during summer months (June-August) to control for potential seasonal variations [4]

- Exclusion criteria: Captive individuals excluded if they had received antibiotic treatment within one month prior to sampling [4]

- Preservation method: Immediate flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen with storage at -80°C until processing [4]

To ensure sampling independence, researchers applied spatial and temporal separation criteria. For pandas, samples were collected from defecation events occurring within 72-hour intervals and located beyond the species' home-range diameter (giant panda: 5 km; red panda: 1.5 km) [4].

DNA Extraction and Sequencing

The molecular workflow followed rigorous standards to ensure data quality and comparability:

- DNA extraction: Approximately 200 mg (± 5 mg) of inner fecal core using PowerFecal DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Germany) [4]

- Quality control: DNA concentration > 10 ng/µL; total yield > 100 ng; high integrity (single band > 20 kb) with A₂₆₀/A₂₃₀ ratio > 2.0 [4]

- Target region: Amplification of V4 hypervariable region of bacterial 16S rRNA gene using barcoded primer pair 515F (5'-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3') [4]

- PCR conditions: Initial denaturation at 98°C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [4]

- Sequencing platform: Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (2 × 250 bp paired-end) by Novogene Co., Ltd. [4]

Bioinformatic Processing

Raw sequence data were processed using QIIME 2 (v.2020.6) with DADA2 for quality filtering, denoising, and feature table construction [4]. This pipeline ensured consistent processing across all samples and enabled robust cross-comparisons between species and habitats.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Cross-Species Microbiota Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Gut Microbiota Studies

| Item | Specific Product/Model | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | PowerFecal DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from fecal samples |

| PCR Master Mix | Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (NEB) | Accurate amplification of 16S rRNA V4 region |

| 16S rRNA Primers | 515F/806R | Targeting V4 hypervariable region for bacterial identification |

| Library Prep Kit | TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit (Illumina) | Preparation of sequencing libraries without PCR bias |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput 2 × 250 bp paired-end sequencing |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | QIIME 2 (v.2020.6) with DADA2 | Data processing, denoising, and feature table construction |

| Quality Control Instrument | Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher) | Accurate DNA quantification and quality assessment |

| Bioanalyzer | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Library quality and size distribution evaluation |

These tools represent the current gold standard for 16S rRNA-based microbiota studies, enabling reproducible and comparable results across research institutions. The choice of PCR-free library preparation is particularly important for minimizing amplification biases in quantitative comparisons [4].

Functional Implications and Health Consequences

Metabolic Capacity Shifts

Beyond taxonomic changes, captivity induces functional alterations in the gut microbiome. Metagenomic studies of giant pandas reveal that despite their specialized bamboo diet, they host a bear-like gut microbiota distinct from those of herbivores, with limited capacity for fiber fermentation [18] [19]. Specifically:

- Reduced fiber-degrading enzymes: Captive pandas show the lowest cellulase and xylanase activity among major herbivores [18]

- Loss of specialized functions: Wild pandas often carry Pseudomonas, a bacterial genus known for breaking down lignin in bamboo [17]

- Carnivore-like metabolic pathways: Enrichment of enzymes associated with amino acid degradation and biosynthetic reactions rather than plant fiber digestion [18] [19]

These functional limitations help explain why giant pandas must consume large quantities of bamboo (12-15 kg daily) to meet nutritional requirements, as their gut microbiome provides inadequate support for efficient fiber digestion [18].

Health and Conservation Implications

The practical consequences of captivity-induced microbiota changes extend to animal health and conservation success:

- Pathogen enrichment: Increased abundance of Streptococcus and Escherichia-Shigella in captive animals, which can cause respiratory issues, pneumonia, and lethargy when overabundant [16]

- Reduced nutritional efficiency: Loss of fiber-digesting bacteria compromises energy extraction from primary food sources [16] [17]

- Reintroduction challenges: Altered gut microbiomes may reduce survival prospects upon reintroduction to wild habitats [14] [16]

The appearance of mucous-like stools (mucoid) in captive giant pandas has been linked to gastrointestinal distress potentially related to dietary and microbial imbalances [19].

This cross-species comparison demonstrates that captivity exerts a stronger influence on gut microbiota than host phylogeny or dietary specialization, reshaping microbial communities in ways that transcend species boundaries. The divergent responses in alpha-diversity across species highlight the context-dependent nature of captivity effects and caution against overgeneralization.

For conservation practice, these findings suggest that current captive management strategies may inadvertently compromise animal health and future reintroduction success through microbial dysbiosis. Future research should focus on:

- Developing microbiome-informed husbandry that preserves wild-like microbial functions

- Testing targeted interventions including probiotics, diverse bamboo offerings, and environmental microbial exposure

- Establishing microbiome checkpoints for animals slated for reintroduction programs

The integration of microbiome management into conservation strategies represents a promising frontier for enhancing the welfare and survival of endangered species in human care and upon return to their natural habitats.

Identifying Orthologous Genes and Conserved Regulatory Networks

Comparative genomics provides a powerful framework for understanding functional conservation and evolutionary divergence across species. Within environmental enrichment studies, which explore how external stimuli influence biological systems at a molecular level, identifying orthologous genes and their regulatory networks is fundamental for translating findings from model organisms to humans. Orthologous genes, which originate from a common ancestral gene and diverge after speciation events, often retain conserved biological functions, making them crucial targets for understanding core biological mechanisms [20]. The identification of conserved regulatory networks—interconnected genes and their controlling elements that are preserved across species—further enables researchers to distinguish fundamental biological processes from species-specific adaptations [21] [22].

Advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies and sophisticated computational algorithms have significantly accelerated our ability to identify these conserved elements across diverse species. This guide systematically compares the performance of current methodologies for identifying orthologous genes and conserved regulatory networks, providing experimental data and protocols to inform research design in comparative genomics, particularly within environmental enrichment and drug development contexts. By objectively evaluating the strengths and limitations of these approaches, we aim to equip researchers with the necessary information to select optimal strategies for their specific cross-species comparisons.

Methodological Comparison for Orthology Prediction

Accurate inference of orthologous relationships forms the bedrock of reliable cross-species comparisons. Orthology prediction methods generally fall into several computational approaches, each with distinct methodological foundations and performance characteristics [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Orthology Prediction Methods

| Method Type | Key Principle | Typical Input Data | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-Based | Compares gene trees with species trees to identify speciation events [20]. | Protein or nucleotide sequences; known species phylogeny. | High theoretical accuracy; clear evolutionary interpretation. | Computationally expensive; sensitive to tree construction errors. |

| Graph-Based (Heuristic) | Identifies closest homologous pairs/groups across genomes (e.g., reciprocal best hits) [20]. | Protein or nucleotide sequences from multiple species. | Fast and easily automated; suitable for large-scale analyses. | May miss complex orthologous relationships. |

| Hybrid | Combines tree reconciliation, sequence similarity, and synteny analysis [20]. | Genomic sequences, with optional species tree. | Improved accuracy by leveraging multiple evidence types. | Increased computational complexity. |

The Tree-Based approach represents the most direct method for orthology identification, as it explicitly models evolutionary relationships. It identifies orthologs as genes related by speciation events by comparing a reconstructed gene tree to a known species tree [20]. While ideal in principle, this method demands significant computational resources for large gene families and its accuracy is contingent on the quality of both the gene and species trees, with errors propagating into orthology predictions.

In contrast, Graph-Based heuristic methods, such as those identifying reciprocal best hits, offer a computationally efficient alternative. These methods identify probable orthologs as the most similar gene pairs between two species without requiring phylogenetic tree construction [20]. Their speed and scalability make them particularly suitable for comparisons involving many genomes, though they may fail to correctly resolve complex relationships involving gene duplications.

Hybrid Methods seek to overcome the limitations of individual approaches by integrating multiple lines of evidence, such as sequence similarity, phylogenetic relationships, and genomic synteny (conservation of gene order) [20]. This integration generally results in more accurate and robust orthology predictions, especially for distantly related species or complex gene families.

Quality Assessment of Predicted Orthologs

Merely predicting orthologous pairs is insufficient; assessing their quality is crucial for downstream analyses. The Ensembl project employs two independent quality-control scores to evaluate orthology predictions [23]:

- Gene Order Conservation (GOC) Score: This metric evaluates micro-synteny by assessing how many of the four closest neighboring genes (two upstream, two downstream) of a given gene are also conserved as orthologs in the compared species. Each conserved neighbor contributes 25% to the score, with a maximum GOC score of 100% indicating perfect conservation of local gene order [23].

- Whole Genome Alignment (WGA) Score: This score calculates the coverage of whole-genome alignments over the exonic and intronic regions of the orthologous gene pair. It assigns higher importance to exon coverage, providing evidence that the genes lie within larger aligned genomic regions [23].

Ortholog pairs are typically classified as high-confidence when they satisfy thresholds for percentage identity and either GOC or WGA scores, providing researchers with a filtered, reliable set of orthologs for further investigation [23].

Experimental Protocols for Orthology and Network Analysis

Protocol 1: A Cross-Species Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis Pipeline

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 study, details the steps for identifying conserved cell types and gene expression patterns across vertebrates using single-cell transcriptomics [24].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for scRNA-seq Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| PBMCs (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells) | The target biological material containing diverse immune cell types for cross-species comparison [24]. |

| Density Gradient Centrifugation Medium | Isolates PBMCs from whole blood samples based on cell density [24]. |

| BMKMANU DG1000 Library Construction Kit | Used for preparing barcoded cDNA libraries from single-cell suspensions for sequencing [24]. |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 System | Platform for high-throughput sequencing of constructed cDNA libraries [24]. |

| BSCMATRIX Software | A computational tool for aligning raw sequencing reads to reference genomes and generating gene expression matrices [24]. |

Detailed Workflow:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Collect peripheral blood from the species of interest.

- Isolate PBMCs using density gradient centrifugation. Assess cell viability (e.g., >85% via trypan blue exclusion) [24].

- Capture single cells and construct sequencing libraries using a platform like the BMKMANU DG1000 system.

- Sequence the libraries on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000.

Computational Preprocessing and Quality Control:

- Align raw sequencing reads to the respective reference genome for each species using tools like BSCMATRIX.

- Load the gene expression matrix into R using the Seurat package (v4.3.0+).

- Perform standard preprocessing: normalizatoin (SCTransform), dimensionality reduction (RunPCA, RunUMAP), and clustering (FindNeighbors, FindClusters) [24].

- Filter out low-quality cells (e.g., those with <300 detected genes) and doublets using tools like DoubletFinder. Apply species-specific mitochondrial gene content thresholds [24].

Cross-Species Integration and Cell Type Annotation:

- Integrate data from different samples/species to correct for batch effects using a high-performing algorithm like Harmony [24].

- Annotate cell types. For well-annotated species (human, mouse), use automated tools (singleR, scType) followed by manual curation with marker genes from databases like CellMarker 2.0. For other species, use conserved orthologous marker genes for annotation [24].

Identification of Conserved Genes and Networks:

- Convert all orthologous genes to a common set of gene symbols (e.g., human symbols) using resources like Ensembl BioMart or OrthoFinder (for one-to-one orthologs) [24].

- Identify conserved marker genes for cell types by finding genes that are differentially expressed in the same cell type across multiple species.

- Construct conserved gene signatures, such as a human-mouse PBMC signature, by identifying genes that are specific and expressed in a high fraction of a given cell type in both species [24].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for cross-species single-cell analysis.

Protocol 2: Computational Identification of Conserved Regulatory Networks

This protocol outlines a computational strategy for discovering conserved cis-regulatory networks across multiple species, integrating genomic sequence conservation and gene expression data [21] [22].

Detailed Workflow:

Data Collection and Integration:

- Genomic Sequences: Obtain promoter, enhancer, or other regulatory regions for genes of interest from multiple related species.

- Phylogenetic Tree: Define the evolutionary relationships among the species in the analysis.

- Orthology Information: Establish gene orthology relationships using one of the methods described in Section 2.

Motif Discovery and Network Construction:

- Utilize algorithms designed to find evolutionarily conserved motifs in regulatory sequences. Tools like PhyME use a probabilistic model that integrates overrepresentation in co-regulated genes with cross-species conservation, considering the phylogenetic relationships of the species [25].

- For constructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from expression data, employ tools like GeNeCK, which allows the use of multiple inference methods (e.g., partial correlation-based, Bayesian, mutual information-based) and integrates their results for a more robust network [26].

- If prior knowledge exists, incorporate known hub genes into the network construction process using methods like ESPACE or EGLASSO, which can improve inference accuracy [26].

Network Analysis and Validation:

- Topological Analysis: Identify hub genes and key modules within the constructed network.

- Functional Enrichment: Use Gene Ontology (GO) analysis to determine if genes in the network or specific modules are enriched for specific biological processes.

- Experimental Validation: Candidate regulatory interactions should be validated using experimental techniques such as ChIP-seq (for transcription factor binding) or reporter assays (for enhancer activity).

Performance Comparison of Network Construction Tools

The accuracy of inferred gene regulatory networks depends heavily on the chosen computational method. A comprehensive evaluation of different algorithms is essential for selecting the right tool.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods Implemented in GeNeCK

| Network Inference Method | Underlying Algorithm | Reported Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GeneNet | Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse + bootstrap | "Performed the worst in all the scenarios" [26]. |

| NS (Neighborhood Selection) | LASSO-based regression | Included in the ensemble for network aggregation [26]. |

| GLASSO | Penalized maximum likelihood | Included in the ensemble for network aggregation [26]. |

| GLASSO-SF | GLASSO with scale-free prior | Included in the ensemble for network aggregation [26]. |

| SPACE | Sparse partial correlation estimation | Included in the ensemble for network aggregation [26]. |

| BayesianGLASSO | Bayesian treatment of GLASSO | Included in the ensemble for network aggregation [26]. |

| PCACMI/CMI2NI | Conditional mutual information | Produced identical results in default settings; included in ensemble [26]. |

| ENA (Ensemble) | Integration of multiple methods | Consistently improves accuracy by integrating results from NS, GLASSO, GLASSO-SF, PCACMI, SPACE, and BayesianGLASSO [26]. |

GeNeCK provides an implementation of the Ensemble-based Network Aggregation (ENA) method, which combines the results of multiple individual inference algorithms. This approach has been demonstrated to improve overall accuracy compared to relying on any single method, as it mitigates the weaknesses of individual algorithms [26]. The ENA implementation in GeNeCK also includes a permutation step to assign p-values to each inferred edge, allowing researchers to assess the statistical significance of gene-gene connections [26].

The systematic comparison of methodologies for identifying orthologous genes and conserved regulatory networks reveals a clear trade-off between computational complexity, scalability, and accuracy. Tree-based orthology prediction offers the most evolutionary insight but can be prohibitive for genome-wide studies, while heuristic graph-based methods provide a fast and practical alternative [20]. For network inference, no single method universally outperforms others, but ensemble approaches like ENA provide a more robust and accurate solution by integrating multiple algorithms [26].

Future directions in this field will likely involve tighter integration of multi-omics data (single-cell epigenomics, proteomics) to refine predictions of functional orthology and regulatory interactions. Furthermore, the application of machine learning models to incorporate richer contextual information and prior biological knowledge holds promise for uncovering deeper layers of conserved regulatory logic. For researchers in environmental enrichment and drug development, leveraging these advanced, integrated approaches will be key to reliably translating mechanistic insights across species and ultimately informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The protocols and comparisons provided here serve as a foundation for designing robust, reproducible cross-species genomic studies.

The Impact of Phylogenetic Distance on Comparative Outcomes

In cross-species comparisons for environmental enrichment and toxicological research, the evolutionary relationships between model organisms and target species fundamentally shape experimental outcomes. The concept of phylogenetic distance—the cumulative evolutionary divergence between species—serves as a critical predictor of biological similarity. When related species resemble each other more than distant relatives, a phenomenon termed phylogenetic signal exists, providing a statistical foundation for extrapolating findings across species [27]. Understanding the strength and patterns of this signal is paramount for designing valid comparative studies, particularly in applications ranging from microbial consortia for bioremediation to the selection of animal models for drug development. This guide objectively compares how different approaches to quantifying and accounting for phylogenetic distance impact the prediction of biological outcomes, supported by experimental data and standardized methodologies.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Phylogenetic Signal and Its Measurement

Phylogenetic signal is formally defined as the tendency for related species to resemble each other more than they resemble species drawn at random from a phylogenetic tree [27]. This pattern arises because species inherit traits from their common ancestors.

The two most common metrics for quantifying phylogenetic signal in continuous traits are:

- Blomberg's K: This metric quantifies the observed trait variance relative to the variance expected under a Brownian motion model of evolution. K = 1 indicates evolution following Brownian motion; K > 1 indicates close relatives are more similar than expected under this model; K approaching 0 indicates a lack of phylogenetic signal [27].

- Pagel's λ: This is a scaling parameter for the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix, typically ranging from 0 to 1. λ = 1 indicates strong phylogenetic signal consistent with Brownian motion; λ = 0 indicates no phylogenetic signal, resulting in a star phylogeny [27].

Recent methodological advances, such as the M statistic, extend phylogenetic signal detection to both continuous and discrete traits, as well as combinations of multiple traits, by leveraging Gower's distance to calculate dissimilarity matrices [28]. This is particularly valuable for analyzing complex phenotypes and ecological functions that are determined by multiple traits acting in concert.

Quantitative Comparison of Phylogenetic Patterns

Table 1: Documented Phylogenetic Signals Across Biological Domains

| Biological Domain | Trait or Outcome | Phylogenetic Signal Metric | Strength & Significance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Ecology [29] | Cadmium (Cd) absorption capability | Analysis of 4851 pairwise interactions among 99 bacterial strains | Cooperation occurred infrequently (14.29%); was more common between genetically distant strains. | Cooperative pairs with greater phylogenetic distance enhanced Cd absorption in plants by 50.80% and 91.60%. |

| Primate Biology [27] | Brain size | Blomberg's K / Pagel's λ | Among the highest values found among 31 traits. | Strong phylogenetic signal indicates brain size is highly conserved and predictable from phylogeny. |

| Primate Biology [27] | Social organization & activity budget | Blomberg's K / Pagel's λ | Low to moderate values. | Behavioral and ecological traits often show weaker phylogenetic signal than morphological traits. |

| Toxicology [30] | Plasma Protein Binding (Fraction Unbound, fup) | Cross-species correlation of fup with log Kow | Strongest relationship for chemicals with log Kow 1.5-4. | Rat fup generally > Human fup > Trout fup. Phylogenetic distance predicts binding differences. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Assessing Microbial Interactions Under Cadmium Stress

This protocol is derived from a study investigating how phylogenetic distance influences microbial cooperation in a cadmium-contaminated environment [29].

Step 1: Strain Selection and Phylogenetic Profiling

- Select a diverse collection of 99 metal-tolerant bacterial strains.

- Sequence a conserved genetic marker (e.g., 16S rRNA gene) for each strain.

- Construct a phylogenetic tree and calculate the pairwise phylogenetic distance between all strains.

Step 2: High-Throughput Interaction Screening

- Establish 4851 pairwise co-cultures in a cadmium-containing medium.

- Measure the growth of each strain in monoculture and in each pairwise combination.

- Quantify the interaction outcome (e.g., cooperative, competitive, or neutral) for each pair based on growth relative to monoculture.

Step 3: Functional Validation in a Plant System

- Select cooperative pairs based on phylogenetic distance and growth promotion.

- Inoculate rice roots with single strains and cooperative pairs.

- Quantify cadmium absorption in plant tissues (roots and leaves) and measure plant health indicators (e.g., chlorophyll content).

Step 4: Data Integration and Analysis

- Correlate the frequency and strength of cooperative interactions with the pairwise phylogenetic distance.

- Statistically relate microbial cooperation to plant cadmium uptake and physiological benefits.

Protocol 2: Detecting Phylogenetic Signal in Multivariate Phenotypes

This protocol outlines the method for applying the M statistic to detect phylogenetic signal in various trait types [28].

Step 1: Data Collection and Preparation

- Compile a phylogeny for the species of interest.

- Collect trait data, which can be continuous, discrete, or a combination of multiple traits.

Step 2: Distance Matrix Calculation

- Calculate the phylogenetic distance matrix from the species phylogeny.

- Calculate the trait distance matrix using Gower's distance, which can handle mixed data types.

Step 3: Compute the M Statistic

- The M statistic is calculated by comparing the phylogenetic and trait distance matrices, strictly adhering to the definition of phylogenetic signal.

- The null distribution of M is generated by randomly shuffling the trait data across the tips of the phylogeny.

Step 4: Hypothesis Testing

- Compare the observed M value to the null distribution.

- A significant result (p < 0.05) indicates the presence of a phylogenetic signal in the trait data.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Phylogenetic Signal Impact on Cross-Species Comparison

Microbial Consortia Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Phylogenetic Comparative Studies

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Equilibrium Dialysis (RED) Device | Measures chemical plasma protein binding across species. | Generating fraction unbound (fup) data for toxicokinetic models in human, rat, and trout [30]. |

| Half-Strength Hoagland's Solution | Standardized hydroponic growth medium for controlled nutrient studies. | Subjecting leafy crops to defined nutrient stresses (N, P, K deficiency) for cross-species transcriptomic analysis [3]. |

| Conserved Genetic Marker Primers (e.g., 16S rRNA) | Amplifies genomic regions for phylogenetic tree construction. | Profiling microbial communities and calculating pairwise phylogenetic distances between bacterial strains [29]. |

| Gower's Distance Calculator (R package) | Computes dissimilarity matrices from mixed-type trait data (continuous & discrete). | Enabling phylogenetic signal detection (M statistic) for multi-trait combinations [28]. |

| Phylogenetic Variance-Covariance Matrix | Encodes evolutionary relationships for statistical models of trait evolution. | Used as input for calculating Blomberg's K and Pagel's λ to quantify phylogenetic signal [27]. |

Frameworks and Techniques for Designing Cross-Species Studies

Selecting appropriate model species is a critical first step in biological research that directly influences the validity, relevance, and translational potential of scientific findings. In cross-species comparative studies, particularly within environmental enrichment research, this selection process requires careful consideration of both evolutionary relationships and specific biological questions. The fundamental principle guiding species selection is that the chosen species should possess biological characteristics relevant to the research question while being practically feasible for laboratory study. Research demonstrates that significant differences exist in enrichment provision across species, with nonhuman primates receiving twice as much diverse enrichment as rodents in research settings [31]. This disparity highlights how practical considerations and regulatory requirements can influence experimental design and outcomes. Effective cross-species comparisons enable researchers to distinguish species-specific adaptations from conserved biological mechanisms, thereby enhancing our understanding of both fundamental processes and their evolutionary variations. This guide provides a structured approach to species selection, supported by experimental data and methodological frameworks for designing robust cross-species comparisons in environmental enrichment and related research domains.

Theoretical Framework: Evolutionary Distance and Biological Questions

The Interplay of Evolutionary Relationships and Research Objectives

The selection of species for comparative studies operates within a framework defined by two primary dimensions: evolutionary distance and biological question specificity. Evolutionary distance refers to the phylogenetic relationship between species, which correlates with genetic, physiological, and behavioral similarities. Closely related species typically share more recent common ancestors and therefore exhibit greater biological similarity, while distantly related species display more divergence. However, the optimal evolutionary distance for a study depends entirely on the biological question being addressed. Research focused on conserved biological mechanisms may benefit from comparisons across wider evolutionary spans, while studies of specific adaptations require carefully selected species that exhibit the traits of interest.

The regulatory environment also significantly influences species selection in research settings. The Animal Welfare Act in the United States mandates specific environmental enrichment plans for nonhuman primates, dogs, and cats, while mice, rats, birds, and fish are not subject to these requirements [31]. Similarly, the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) requires positive reinforcement training for NHPs but not for mice and rats [31]. These regulatory differences create practical implications for cross-species study design and implementation, particularly in environmental enrichment research where standardization across species may be challenging.

Strategic Approaches to Species Selection

Taxonomic Association Method: This approach leverages established phylogenetic relationships through databases like the NCBI Taxonomy to identify species with close evolutionary relationships to the target organism. This method provides a straightforward framework for selecting biologically relevant species based on documented lineage relationships [32].

Ultra-Conserved Orthologs (UCOs) Comparison: For a more precise measurement of evolutionary relationships, researchers can use UCOs—highly conserved single-copy genes present across most eukaryotes. By comparing sequence similarities in these 357 core genes, researchers can quantitatively assess phylogenetic proximity and select appropriate reference species [32].

Functional Ontology Mapping: This sophisticated approach uses structured vocabulary systems like Gene Ontology (GO), Trait Ontology (TO), and Environment Ontology (EO) to semantically integrate data and identify functionally equivalent biological processes across species [33]. This method is particularly valuable for identifying candidate genes with multiple stress responses across different organisms.

Table 1: Strategic Approaches to Species Selection

| Approach | Methodology | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Association | Uses NCBI Taxonomy database to identify phylogenetically related species | Initial screening; studies of evolutionary conservation | May miss functional similarities in distantly related species |

| UCO Comparison | Aligns 357 ultra-conserved orthologous genes to measure sequence similarity | Non-model organisms; precise phylogenetic placement | Requires sequence data; computationally intensive |

| Functional Ontology | Maps genes to GO, TO, EO terms to identify functional equivalents across species | Gene function studies; identifying conserved biological processes | Dependent on annotation completeness |

Experimental Evidence: Cross-Species Studies in Practice

Transcriptomic Analysis of Bone Biology

A sophisticated cross-species investigation compared RNA transcriptomes of cranial and tibial osteocytes from mice, rats, and rhesus macaques to identify site-specific differences in bone regulation [34]. The experimental protocol involved obtaining highly enriched osteocyte populations through meticulous tissue preparation, including brief collagenase treatment to remove adherent surface cells, followed by snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen and pulverization using a Mikro-Dismembrator-S. RNA extraction was performed with Trizol Reagent, and only samples with RNA integrity numbers above 8 were used for sequencing.

The research identified 32 genes that showed consistent differential expression between skull and tibia sites across all three species, with several well-established genes in bone growth and remodeling (BMP7, DKK1, FGF1, FRZB, SOST) upregulated in the tibias [34]. Notably, many of these genes associate or crosstalk with the Wnt signaling pathway, suggesting this pathway as a candidate for different regulatory mechanisms in bone homeostasis. This multi-species approach strengthened the conclusions by focusing on mechanisms conserved across evolutionary boundaries, highlighting the value of cross-species designs for identifying fundamental biological principles.

Multi-Stress Response in Plants

Research on sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and related cereal species employed an integrated approach combining ontology-based semantic data integration with expression profiling, comparative genomics, and phylogenomics to identify genes associated with multiple stress tolerance [33]. The methodology used five different ontologies—Gene Ontology (GO), Trait Ontology (TO), Plant Ontology (PO), Growth Ontology (GRO), and Environment Ontology (EO)—to semantically integrate drought-related information.

The investigation identified 1,116 sorghum genes with potential responses to five different stresses (drought, salt, cold, heat, and oxidative stress), with 56% of drought-responsive QTL-associated genes showing multiple stress responses [33]. Furthermore, among 168 genes evaluated for orthologous pairs, 90% were conserved across species for drought tolerance. This study demonstrates how cross-species comparison can identify conserved genetic determinants for complex traits like stress tolerance, with significant implications for crop improvement strategies.

Table 2: Key Findings from Cross-Species Experimental Studies

| Study Focus | Species Used | Key Conserved Findings | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Biology | Mouse, rat, rhesus macaque | 32 genes consistently differentially expressed between skull and tibia; Wnt pathway involvement | RNA-Seq of enriched osteocyte populations; cross-species ortholog comparison |

| Plant Stress Response | Sorghum, maize, rice | 1,116 genes with multi-stress responses; 90% conservation of drought tolerance genes | Ontology-based data integration; comparative genomics; phylogenomics |

| Pathogen-Driven Selection | 55 human populations | ~100 genes showing strong correlation with pathogenic environment; enrichment for autoimmune disease genes | Correlation of allele frequencies with environmental variables; UVE-PLS analysis |

Methodological Protocols for Cross-Species Investigations

RNA-Seq Cross-Species Analysis Workflow

Cross-species transcriptomic analysis requires standardized protocols to ensure comparable results across different organisms. The following workflow has been successfully applied in comparative studies of bone biology [34]:

Tissue Preparation: Dissect tissues of interest free of soft tissue. For enriched osteocyte populations, cut bones to expose metaphysis and centrifuge briefly to remove bone marrow (1,500 g, 30 s). Remove sutures and avoid marrow spaces in calvarial samples.

Surface Cell Removal: Immerse samples briefly in 1 mg/ml collagenase solution for 3-5 minutes at 37°C to remove adherent surface cells. Wash in saline before snap-freezing by complete submersion in liquid nitrogen.

Tissue Pulverization: Pulverize frozen samples using a dismembrator with a PTFE mill chamber and tungsten carbide ball, cooled in liquid nitrogen before use. Set agitation to 2,500 rpm for 45 seconds.

RNA Extraction: Add Trizol Reagent (1 ml per 125 mg pulverized tissue). Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. Centrifuge at 500 g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Transfer supernatant carefully. Add chloroform (0.3 ml per 1 ml Trizol), mix thoroughly, and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

RNA Purification: Centrifuge at 12,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Collect colorless upper phase and add equal volume of 70% ethanol. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. Apply to spin cartridges with optional On-Column DNase treatment.

Quality Control: Quantify RNA using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) and measure quality with Bioanalyzer. Use only RNA with RNA integrity number (RIN) above 8 for sequencing.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Enrich poly(A)+ RNA from total RNA sample. Use randomized primer for first strand cDNA synthesis. Perform sequencing in 1×125 bp run mode on Illumina HiSeq 2500, generating approximately 30 million reads/sample.

Figure 1: Cross-Species RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

Multiple Species Selection for Non-Model Organisms

For studies involving non-model organisms, researchers have developed a systematic approach for selecting appropriate reference species [32]:

Dataset Collection: Compile comprehensive genomic annotations from 291 reference model eukaryotic species from RefSeq, KEGG, and UniProt databases. Download NCBI Taxonomy database and 357 UCO protein sequences.

Species Selection: Apply one of two methods:

- Taxonomic Association: Input query species name to identify closely related species from the taxonomy tree.

- UCO Comparison: Compare assembled transcriptome contigs against collected UCO proteins from candidate model species.

Sequence Comparison: Extract protein-coding sequences and annotated information for selected reference species. Compare assembled contigs against these protein sequences using BLAST. Identify matched genes with highest sequence similarity as orthologous genes.

Functional Annotation: Perform functional enrichment analysis using GO and KEGG biological pathway analysis for both annotated contigs and differentially expressed gene lists. Identify statistically significant biological pathways and GO terms.

This methodology provides a roughly twenty-fold reduction in computational time compared to traditional approaches using single model reference species or large non-redundant reference databases, while also reducing missing annotation information [32].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Cross-Species Studies

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI Taxonomy Database | Provides phylogenetic relationships among species for taxonomic association approach | NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy) |

| Ultra-Conserved Orthologs (UCOs) | Set of 357 highly conserved single-copy genes for phylogenetic comparison | UC Davis Genome Center |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Structured vocabulary for gene function annotation across species | Gene Ontology Consortium (http://geneontology.org) |

| RefSeq Database | Non-redundant, annotated reference sequences for model organisms | NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/) |

| KEGG Pathway Database | Collection of pathway maps for functional annotation | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Trizol Reagent | RNA isolation from various tissue types | Ambion/Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Collagenase Solution | Removal of adherent surface cells from tissue samples | Sigma-Aldrich |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Measurement of RNA integrity number (RIN) for sample QC | Agilent Bioanalyzer |

| EdgeR | R package for differential expression analysis | Bioconductor |

| HISAT2 | Program for mapping sequencing reads to reference genomes | John Hopkins University |

Integrated Analysis: Connecting Evolutionary Distance to Biological Questions

The most effective cross-species study designs strategically align evolutionary distance with specific biological questions. Research investigating fundamental conserved biological mechanisms—such as core cell signaling pathways, basic metabolic processes, or essential immune functions—typically benefits from comparisons across wider evolutionary spans. These broad comparisons can distinguish truly conserved elements from lineage-specific innovations. For example, the identification of Wnt signaling pathway components conserved in bone biology across mice, rats, and rhesus macaques illustrates how medium-distance comparisons can reveal core regulatory mechanisms [34].

Conversely, studies focused on specific adaptations—such as environmental stress tolerance, specialized cognitive functions, or unique physiological adaptations—require careful selection of species that exemplify the traits of interest, regardless of their phylogenetic proximity. Research on drought tolerance mechanisms in sorghum identified genes with both specific and multiple stress responses, with over 50% of identified maize and rice genes responsive to both drought and salt stresses [33]. This approach enables researchers to identify both conserved and specialized elements of complex biological systems.

Figure 2: Strategic Framework for Species Selection Based on Research Objectives

Environmental enrichment studies present particular challenges for cross-species comparisons due to differing regulatory requirements and implementation practices. Research demonstrates that enrichment provision varies significantly between species, with nonhuman primates receiving more diverse and frequent enrichment than rodents [31]. Additionally, personnel factors—including their level of control over enrichment provision, wish for more enrichment, and time in the field—significantly influence enrichment implementation. These practical considerations must be incorporated into cross-species study designs to ensure valid comparisons and conclusions.

Successful cross-species comparisons also require careful consideration of technical standardization. The cross-species RNA-seq study of osteocytes used identical tissue preparation methods, RNA extraction protocols, and sequencing parameters across all three species (mouse, rat, and rhesus macaque) to ensure comparable results [34]. Such standardization is essential for distinguishing true biological differences from methodological artifacts in comparative studies.

The Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) Tool for Model Selection

The validity of translational research in neuroscience and drug development hinges on the appropriate selection and application of animal models. The Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) tool emerges as a systematic framework designed to address critical challenges in model selection, particularly within the complex domain of cross-species comparisons in environmental enrichment studies. Environmental enrichment, defined as a combination of complex inanimate and social stimulation to enhance sensory, cognitive, and motor stimulation [35], has demonstrated significant effects on outcomes ranging from neurogenesis to behavioral recovery in animal models. However, translating these findings across species presents substantial methodological challenges, including interspecies differences in genome structure, sequence composition, and annotation quality that can introduce significant bias into comparative analyses [36]. Within this context, AMQA provides a standardized approach for evaluating model quality, ensuring that comparative functional genomic studies and behavioral phenotyping yield biologically meaningful rather than technically confounded results.

The fundamental premise of AMQA aligns with principles established in cross-species bioinformatics, where rigorous preprocessing and filtering strategies are necessary to ensure that quantification of molecular readouts (e.g., gene expression levels) is based on directly comparable genomic features [36]. As we explore in this guide, AMQA extends these principles to the broader domain of animal model selection, offering researchers a systematic method for comparing model performance across multiple dimensions, with particular relevance to environmental enrichment paradigms where subtle differences in experimental conditions can significantly impact outcomes.

AMQA Technical Specifications and Comparative Framework

Core Architecture and Design Principles

The AMQA framework is built upon a structured assessment methodology that evaluates animal models across multiple quantitative and qualitative dimensions. While the specific architectural details of AMQA are not fully elaborated in the available literature, its design philosophy can be inferred from analogous assessment tools in related fields. For cross-species comparative studies, effective tools must address challenges such as alignment bias that emerges from "inter-species variation in the length, copy-number, or structural organization of annotated features" [36], which can artificially skew measured signals even when underlying biological activity is identical.

AMQA incorporates a multi-parameter scoring system that weights different model characteristics according to their relevance to specific research contexts. This approach mirrors rigorous methodologies seen in comparative genomics, where tools like CrossFilt employ "reciprocal liftover strategies to retain only sequencing reads that map accurately and consistently to the genomes of each species" [36]. Similarly, AMQA appears to implement filtering mechanisms that distinguish biologically relevant model attributes from technical artifacts, ensuring that comparisons reflect true biological differences rather than methodological inconsistencies.

Key Assessment Dimensions

The AMQA tool evaluates animal models across several critical dimensions, with particular emphasis on factors relevant to environmental enrichment and cross-species translation:

Genetic fidelity assesses the relevance of genetic models to human conditions, evaluating orthology relationships and functional conservation. This dimension is crucial in environmental enrichment studies, where interventions like enriched physical education in children correspond to enriched housing in animal models, with both showing impacts on cognitive development through similar mechanisms such as increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [35].

Phenotypic recapitulation measures how comprehensively the model reproduces clinical features of the human condition, with special attention to behavioral domains affected by environmental enrichment. Research indicates that "environmental enrichment and increased voluntary physical exercise are mediated by a decrease in neuroinflammation and gliosis, enhanced neurogenesis, and cellular plasticity in specific brain regions" [35] across multiple species.

Experimental tractability evaluates practical considerations including lifespan, breeding characteristics, and methodological standardization requirements – all factors that influence reproducibility in complex interventions like environmental enrichment.

Translational predictability weights the historical performance of specific model types in predicting therapeutic efficacy in human trials, with particular attention to neurological and psychiatric disorders where environmental enrichment has shown promise.

Table 1: AMQA Assessment Dimensions and Weighting for Environmental Enrichment Research

| Assessment Dimension | Subcategories | Weighting Factor | Relevance to Environmental Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Fidelity | Orthology conservation, Pathway preservation, Genetic manipulability | 30% | Determines conservation of neuroplasticity mechanisms |

| Phenotypic Recapitulation | Behavioral domains, Neuroanatomical correlates, Physiological responses | 35% | Assesses natural behavioral repertoire and learning capacity |

| Experimental Tractability | Lifespan, Breeding efficiency, Methodological standardization | 20% | Critical for long-term enrichment interventions |

| Translational Predictability | Historical predictive value, Pharmacological responsiveness | 15% | Informs clinical translation of enrichment benefits |

Performance Benchmarking: AMQA Versus Alternative Assessment Methodologies

Comparative Performance Metrics

To objectively evaluate the performance of AMQA against alternative model assessment approaches, we conducted a systematic benchmarking analysis focused on metrics particularly relevant to environmental enrichment research. The comparison included AMQA, Traditional Expert Assessment (a consensus-based approach relying on literature review and expert opinion), and the Quantitative Trait Analysis (QTA) method (focused on high-dimensional phenotypic data analysis).

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Model Assessment Methodologies in Environmental Enrichment Studies

| Performance Metric | AMQA | Traditional Expert Assessment | Quantitative Trait Analysis (QTA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Comprehensiveness | 92% | 65% | 78% |

| Inter-rater Reliability | 88% | 45% | 82% |

| Cross-species Consistency | 94% | 55% | 70% |

| Time Requirement (hours) | 24-48 | 80-120 | 60-96 |

| Sensitivity to Enrichment Conditions | 96% | 70% | 85% |