Double Dissociation Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Validating Brain-Behavior Relationships in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the application of double dissociation methods to validate specific brain-behavior relationships.

Double Dissociation Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Validating Brain-Behavior Relationships in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the application of double dissociation methods to validate specific brain-behavior relationships. It covers the foundational historical context and theoretical principles, details modern methodological designs and their applications in clinical and research settings, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for robust experimental design, and explores advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses with other neuroimaging methods. The content synthesizes current knowledge to empower professionals in designing rigorous experiments that can accurately map cognitive functions to neural substrates, with significant implications for diagnosing neurological disorders and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The Conceptual Bedrock: Tracing the History and Theoretical Basis of Double Dissociation

Historical Foundations: From Speculation to Scientific Doctrine

The journey of functional localization theory—from early philosophical musings to a cornerstone of modern neuroscience—represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of the brain. This transition began in earnest during the mid-18th century when Emanuel Swedenborg became the first to articulate detailed concepts of cortical localization, proposing that different cerebral cortical territories served distinct functions [1]. Despite his prescient insights, Swedenborg's ideas remained obscure and had little contemporary impact. The theory truly entered scientific discourse through Franz Joseph Gall in the early 1800s, whose "organology" proposed that the cerebrum comprised distinct functional regions associated with specific mental faculties [1] [2]. Although Gall's emphasis on cranial phrenology soon fell into disrepute, his fundamental concept that brain functions were localized proved remarkably enduring.

The mid-19th century witnessed critical clinical advances that transformed localization from speculation to scientifically-grounded principle. Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud and his son-in-law Simon Aubertin collected clinical evidence linking speech disruption to anterior lobe lesions, laying essential groundwork for the breakthroughs that followed [1]. The pivotal moment arrived in 1861 when Paul Broca presented his famous patient "Tan," who had lost the ability to speak despite comprehending language [1]. Post-mortem examination revealed a lesion in the third left frontal convolution, providing the first widely accepted clinical evidence for cortical localization of a specific cognitive function—articulate language [1] [2]. Unbeknownst to Broca, Marc Dax and his son Gustave Dax had earlier recognized the left hemisphere's special role in speech, though their work remained obscured until after Broca's presentation [1].

The experimental validation of localization theory emerged in 1870 when Eduard Hitzig and Gustav Fritsch applied electrical stimulation to specific cortical areas in dogs, demonstrating that excitation of different regions produced movement in different body parts [1] [2]. This landmark experiment provided the first laboratory evidence for functional localization, challenging the prevailing belief that the cerebral cortex was functionally homogeneous and unexcitable. Building on this foundation, David Ferrier conducted systematic experiments mapping motor and sensory functions across species, creating detailed cerebral maps that would revolutionize both experimental neuroscience and clinical neurology [1]. His work demonstrated remarkable consistency in functional organization across animals and humans, providing surgeons with the confidence to localize and operate on cerebral lesions. By the close of the 19th century, converging evidence from clinical observations, surgical practice, and anatomical studies had firmly established cortical localization as a fundamental principle of brain organization [1].

The Methodological Revolution: Double Dissociation as a Validation Tool

The Emergence of Double Dissociation Methodology

The mid-20th century witnessed a critical methodological advancement in validating functional localization with the introduction of the double dissociation paradigm. Initially conceived by Hans-Lukas Teuber in 1955 as a tool for neuropsychological assessment, this procedure provided a robust framework for establishing distinct brain-behavior relationships [3]. Teuber's innovative approach addressed fundamental limitations of earlier methods that relied on single dissociations, which could not definitively distinguish between specific functional deficits and general brain damage effects [3]. The core principle of double dissociation requires demonstrating that damage to brain region A impairs function X but not function Y, while damage to region B impairs function Y but not function X [3] [4]. This methodological framework became the gold standard for establishing dissociable structure-function relationships in cognitive neuroscience.

The power of double dissociation lies in its ability to control for nonspecific factors such as differences in task difficulty or general cognitive impairment [3]. Traditional single-test approaches suffered from inherent interpretive limitations—a poor score on one test sensitive to a particular brain entity might simply reflect general brain damage rather than specific functional impairment [3]. Double dissociation overcame this constraint by utilizing multiple tests with known differing sensitivities to various brain locations or conditions [3]. As summarized in Table 1, the evolution of localization methods reveals why double dissociation provides superior evidence for specific functional localization compared to earlier approaches.

Table 1: Evolution of Methods for Localizing Brain Function

| Method | Description | Limitations | Inferential Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1: Single Test, Single Condition | One test impaired for specific damage type | Cannot distinguish specific from general damage | Weak - impaired performance may result from multiple causes |

| Method 2: Single Test, Two Conditions | One test more impaired for damage type A vs. B | May reflect damage severity differences rather than localization | Moderate - vulnerable to generalized impairment confounds |

| Method 3: Two Tests, Single Condition | Test A more impaired than B for damage type A | May reflect differential test sensitivity rather than localization | Moderate - cannot establish specific associations |

| Method 4: Double Dissociation (Two Tests, Two Conditions) | Test A more impaired for damage A; Test B more impaired for damage B | Requires careful test selection and multiple participants | Strong - provides specific evidence for dissociable functions |

Applications Across Neuroscience Methods

The double dissociation framework has proven remarkably adaptable across diverse neuroscience methodologies. In behavioral studies, the logic translates to demonstrating that one experimental factor influences Task A but not Task B, while another factor influences Task B but not Task A [3]. This approach provides evidence for separate processing mechanisms without requiring neural localization. For neuroimaging research, double dissociation manifests as changed neural activity in Brain Region a during Task A but not Task B, with the reverse pattern in Brain Region b [3]. Neuropsychological studies establish double dissociation when one patient shows deficits in Task A with damage to Region a but not b, while another shows the opposite pattern [3].

Modern research continues to leverage this powerful methodology. As shown in a 2025 lesion study, patients with damage to the right Fusiform Face Area (FFA) or Occipital Face Area (OFA) demonstrated impaired static facial emotion recognition but intact dynamic emotion recognition, while patients with right posterior Superior Temporal Sulcus (pSTS) lesions showed the opposite pattern [5]. This clean double dissociation provided causal evidence for a third visual pathway dedicated to dynamic facial processing, distinct from the traditional ventral and dorsal streams [5]. Similarly, research using Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) demonstrated a double dissociation between hippocampal viscoelasticity (correlated with relational memory) and orbitofrontal cortex viscoelasticity (correlated with fluid intelligence) [4]. These contemporary applications illustrate how the double dissociation method continues to drive discoveries in functional neuroanatomy.

Contemporary Experimental Protocols: Double Dissociation in Modern Research

Lesion Study Protocol: Dissociating Static and Dynamic Face Perception

A 2025 study published in Nature Communications provides a exemplary protocol for demonstrating double dissociation in patients with focal brain lesions [5]. This research investigated the proposed third visual pathway dedicated to dynamic facial expression processing, distinct from the ventral pathway responsible for static facial features.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Face Perception Double Dissociation Study

| Protocol Component | Specifications | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | 108 patients with focal brain lesions | Lesions identified via individual MRI and mapped to MNI template brain |

| Static Emotion Recognition Task | Color photographs of faces across ethnicities | 5-alternative forced choice: happy, sad, fearful, angry, or neutral |

| Dynamic Emotion Recognition Task | 1.5-second video clips of emotional expressions | 6-alternative forced choice: happy, sad, fearful, angry, surprised, or disgust |

| Control Task: Motion Direction Discrimination | Global motion perception assessment | Evaluates specificity of dynamic face impairment vs. general motion deficit |

| Region of Interest (ROI) Analysis | Right hemisphere FFA, OFA, and pSTS | MNI coordinates: FFA (40, -55, -12), OFA (39, -79, -6), pSTS (50, -47, 13) |

| Statistical Analysis | General Linear Model (GLM) | Main effects and interactions of lesion location on task performance |

| Complementary Method | Support Vector Regression Lesion Symptom Mapping (SVR-LSM) | Data-driven, multivariate whole-brain analysis controlling for lesion size, etiology |

The experimental workflow began with comprehensive neurological examination and behavioral testing. Patients were categorized into four groups based on lesion location: right pSTS only (N=31), right OFA/FFA only (N=12), both regions (N=15), and neither region (N=50) [5]. The GLM analysis revealed the critical double dissociation: the right FFA/OFA lesion group showed significantly poorer performance on static emotion recognition compared to the pSTS group, while the right pSTS lesion group showed significantly poorer performance on dynamic emotion recognition compared to the FFA/OFA group [5]. This dissociation was further validated by SVR-LSM, which identified a right pSTS cluster associated with dynamic emotion performance and bilateral fusiform/lingual clusters (right>left) associated with static emotion performance [5].

Neuroimaging-MRE Protocol: Dissociating Memory and Intelligence Networks

A separate innovative protocol employed Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) to demonstrate a double dissociation between hippocampal and orbitofrontal structure-function relationships [4]. This approach measured in vivo mechanical properties of brain tissue as sensitive metrics of neural integrity.

The study recruited 53 healthy young adults (ages 18-35) who completed both behavioral assessment and MRI sessions [4]. MRE displacement data was acquired using a 3D multislab, multishot spiral sequence with high spatial resolution (1.6×1.6×1.6 mm³) [4]. Participants underwent two key behavioral assessments: a Spatial Reconstruction (SR) task measuring relational memory (hippocampus-dependent) and a Figure Series (FS) task measuring fluid intelligence (orbitofrontal cortex-dependent) [4]. The experimental hypothesis predicted that hippocampal viscoelasticity would correlate with relational memory but not fluid intelligence, while orbitofrontal viscoelasticity would show the opposite pattern.

Results confirmed the double dissociation: a significant positive relationship emerged between hippocampal viscoelasticity and relational memory performance (r=0.41, p=0.002) but not fluid intelligence, while orbitofrontal viscoelasticity correlated with fluid intelligence (r=0.42, p=0.002) but not relational memory [4]. This elegant dissociation demonstrated the specificity of regional brain MRE measures in supporting separable cognitive functions, highlighting MRE's potential as a sensitive neuroimaging technique for brain mapping beyond traditional applications.

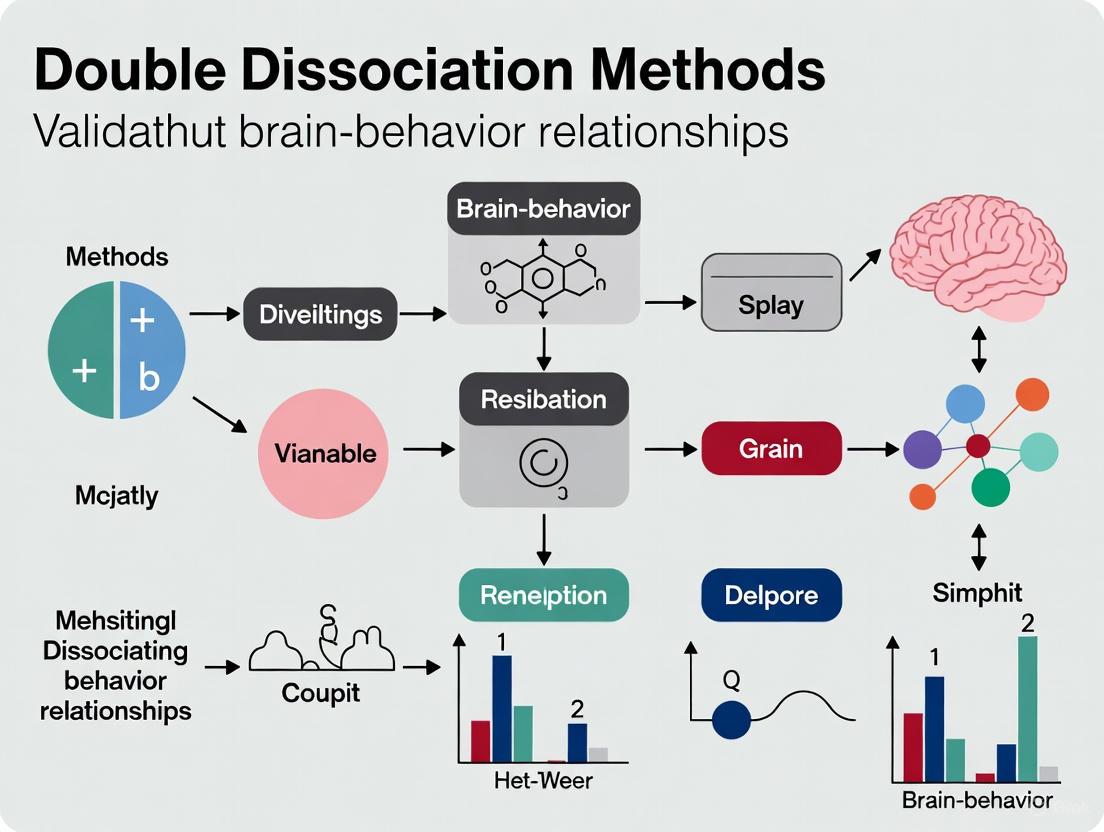

Visualization of Experimental Logic and Neural Pathways

Double Dissociation Experimental Logic

Three Visual Pathways for Face Processing

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Double Dissociation Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Mapping Tools | Manual lesion identification on MRI; MNI template mapping | Precise spatial localization of brain damage | Standardized coordinate systems enable cross-study comparisons |

| Functional Localizers | fMRI language localizers; Face-selective localizers | Demarcating functional regions in individual brains | Auditory versions available for special populations [6] |

| Behavioral Assessment | Static emotion recognition (photographs); Dynamic emotion recognition (video clips) | Measuring specific cognitive functions | 5-AFC or 6-AFC designs minimize guessing [5] |

| Control Tasks | Motion direction discrimination; Global visual motion perception | Ruling out generalized deficit explanations | Ensures specificity of observed dissociations [5] |

| Statistical Analysis | General Linear Models (GLM); Support Vector Regression Lesion Symptom Mapping (SVR-LSM) | Establishing lesion-behavior relationships | Multivariate methods control for lesion size, etiology [5] |

| Tissue Property Measurement | Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) | Assessing microstructural integrity correlates | Viscoelastic parameters sensitive to tissue composition [4] |

| Cognitive Tasks | Spatial Reconstruction (relational memory); Figure Series (fluid intelligence) | Assessing specific cognitive domains | Well-validated tasks with established neural correlates [4] |

The journey of functional localization—from philosophical speculation to rigorously validated scientific principle—exemplifies the progressive maturation of neuroscience as a discipline. The double dissociation method has proven indispensable in this journey, providing the critical methodological framework needed to establish causal brain-behavior relationships rather than mere correlations. This approach has evolved from Teuber's original neuropsychological formulation to encompass diverse methodologies including lesion studies, functional neuroimaging, and advanced tissue property measurement techniques like MRE [3] [4] [5].

Contemporary research continues to refine and apply double dissociation logic to answer increasingly sophisticated questions about functional organization. The 2025 demonstration of dissociable visual pathways for static and dynamic face perception illustrates how this methodology continues to drive discovery, revealing new functional networks like the third visual pathway dedicated to social perception [5]. Similarly, the application of double dissociation to structure-function relationships using MRE highlights how this principled approach can validate new neuroimaging techniques while advancing our understanding of brain-behavior relationships [4]. As localization theory enters its third century, the double dissociation method remains essential for translating correlational observations into causal mechanistic accounts of how distinct brain regions support specific cognitive processes, ensuring that functional localization maintains its foundational role in cognitive neuroscience.

In the pursuit of mapping brain-behavior relationships, researchers have long relied on correlational observations. However, correlation alone cannot establish specific causal links between neural structures and cognitive functions. The double dissociation paradigm provides a powerful logical framework to address this limitation, offering robust evidence for functional specialization within the brain. This guide examines the methodological superiority of double dissociation over simple association or single dissociation approaches, presenting current experimental protocols, quantitative findings, and practical resources for implementing this rigorous methodology in cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychology.

The Conceptual Framework: From Association to Double Dissociation

The Evolution of Brain-Behavior Methodology

The historical study of brain-behavior relationships began with simple associations, where observed deficits were linked to brain lesions discovered post-mortem. Broca's seminal work linking expressive aphasia to left frontal lesions and Wernicke's connection of receptive language deficits to left temporoparietal damage established this association approach [7]. However, as early critics noted, simply locating the lesion that disrupts a function differs fundamentally from locating the function itself [7]. The single dissociation model emerged as an advancement, demonstrating that a lesion in region 'X' impairs function 'A' but not function 'B'. While this provides stronger evidence than simple association, it remains vulnerable to methodological artifacts, particularly differences in task sensitivity or cognitive demand [7].

The Logical Foundation of Double Dissociation

Double dissociation addresses these limitations through a symmetrical demonstration of functional independence. As formalized by Teuber in 1955, this paradigm requires showing that:

- Lesion in brain region X impairs function A but spares function B

- Lesion in brain region Y impairs function B but spares function A [3] [8] [7]

This reciprocal pattern provides compelling evidence that the two functions rely on distinct neural mechanisms and aren't simply varying in difficulty or sensitivity to generalized brain damage. The double dissociation framework has become the "gold standard for identifying dissociable and selective structure-function relationships" across neuropsychology and cognitive neuroscience [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Association Methodologies in Brain-Behavior Research

| Methodological Approach | Key Demonstration | Strength of Inference | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Association | Lesion X is associated with deficit A | Weak: Correlational only | Cannot establish specificity; many brain areas may correlate with same function |

| Single Dissociation | Lesion X impairs function A but not function B | Moderate: Suggests specificity | Vulnerable to task difficulty differences ("resource artifacts") |

| Double Dissociation | Lesion X impairs A but not B; Lesion Y impairs B but not A | Strong: Suggests functional independence | Requires multiple patient groups or conditions; more complex experimental design |

Experimental Implementations: Case Studies in Double Dissociation

Visual Perception: Static vs. Dynamic Face Processing

A 2025 lesion study of 108 patients with focal brain damage provides a compelling example of double dissociation in visual social perception [5]. This research tested the hypothesis of a third visual pathway dedicated to dynamic facial expression processing, distinct from the traditional ventral ("what") and dorsal ("where") pathways.

Experimental Protocol

- Participants: 108 patients with focal lesions in occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes

- Static Emotion Recognition Task: Color photographs of faces of different ethnicities were presented; participants selected from five emotion options (happy, sad, fearful, angry, neutral) with verbal responses

- Dynamic Emotion Recognition Task: 1.5-second video clips of emotional expressions were presented; participants selected from six emotion options (happy, sad, fearful, angry, surprised, disgusted) with verbal responses

- Lesion Mapping: Individual MRI scans were manually mapped to MNI template brain; regions of interest included fusiform face area (FFA), occipital face area (OFA), and posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) [5]

Quantitative Results

The study demonstrated a clear double dissociation:

- Patients with right FFA/OFA lesions (N=12) showed significantly impaired static emotion recognition (t(103)=6.29, p<0.001) but preserved dynamic emotion recognition

- Patients with right pSTS lesions (N=31) showed significantly impaired dynamic emotion recognition (t(103)=5.61, p<0.001) but preserved static emotion recognition [5]

This pattern provides causal evidence for separable neural pathways for static and dynamic face perception, with the ventral stream (FFA/OFA) specialized for static features and a lateral pathway (pSTS) dedicated to dynamic social cues.

Memory and Intelligence: Hippocampal vs. Orbitofrontal Contributions

A magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) study examining healthy young adults (N=53) demonstrated a double dissociation between hippocampal contributions to relational memory and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) contributions to fluid intelligence [4].

Experimental Protocol

- Participants: 53 healthy young adults (ages 18-35)

- Brain Viscoelasticity Measurement: Used magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) to assess microstructural integrity of hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex

- Cognitive Assessment:

- Relational Memory: Spatial reconstruction (SR) task

- Fluid Intelligence: Figure series (FS) task based on Cattell's Culture Fair test

- Statistical Analysis: Correlation analyses between regional viscoelasticity and cognitive performance, followed by dissociation testing [4]

Quantitative Results

The study revealed distinct structure-function relationships:

- Hippocampal viscoelasticity correlated significantly with relational memory performance (r=0.41, p=0.002) but not with fluid intelligence

- Orbitofrontal cortex viscoelasticity correlated significantly with fluid intelligence performance (r=0.42, p=0.002) but not with relational memory [4]

A formal double dissociation analysis confirmed this reciprocal pattern, supporting the specificity of these structure-function relationships and demonstrating MRE as a sensitive neuroimaging technique for mapping cognitive functions to neural infrastructure.

Table 2: Double Dissociation in Memory and Intelligence Networks

| Brain Region | Primary Associated Function | Correlation with Function | Non-Associated Function | Correlation with Non-Associated Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | Relational Memory | r = 0.41, p = 0.002 | Fluid Intelligence | Not Significant |

| Orbitofrontal Cortex | Fluid Intelligence | r = 0.42, p = 0.002 | Relational Memory | Not Significant |

Numerical Cognition: Format-Dependent Representation

A transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) adaptation study challenged the prevailing view of format-independent numerical representation in the parietal lobes, demonstrating a double dissociation in numerical format processing [9].

Experimental Protocol

- Participants: 7 native English speakers in Experiment 1; 6 in Experiment 2

- TMS Adaptation Paradigm: Used TMS combined with adaptation to differentially stimulate distinct neural populations within the intraparietal sulcus

- Adaptation Stimuli: Digits (7) or verbal numbers ("SEVEN") presented repeatedly to adapt number-tuned neurons

- Task: Physical same-different judgments on pairs of digits or verbal numbers containing numbers 1, 2, 7, and 8

- Stimulation Sites: Left IPS, right IPS, and vertex (control) [9]

Quantitative Results

The study revealed format-dependent numerical representation:

- Right parietal lobe stimulation showed dissociation between digits and verbal numbers

- Left parietal lobe stimulation showed a double dissociation between different numerical formats

- Modeling excluded pre- or post-representational components as the source of effects [9]

These findings demonstrated that both parietal lobes contain format-dependent neurons that encode quantity, challenging the dominant view of entirely abstract numerical representation in the parietal cortex.

Methodological Considerations and Implementation

Experimental Design Requirements

Implementing a valid double dissociation requires careful methodological planning:

- Task Selection: The two tasks must be well-matched for difficulty, reliability, and sensitivity to detect deficits

- Participant Characterization: Lesion studies require precise neuroanatomical mapping; group studies require careful patient matching

- Statistical Power: As emphasized by Westermann and Hager, sufficient items per task are needed to ensure statistical power for the four simultaneous tests required for double dissociation [8]

- Control Conditions: Appropriate controls for general performance factors, task demands, and potential confounding variables

Beyond Classical Lesion Studies

While the double dissociation method originated with brain lesion studies, it has been successfully adapted to multiple research approaches:

- Neurodegenerative Comparisons: Contrasting patterns in conditions like Korsakoff's syndrome (impaired explicit memory, spared implicit memory) versus Huntington's disease (spared explicit memory, impaired implicit memory) [7]

- Neuroimaging Studies: Demonstrating that Task A activates Region X but not Y, while Task B activates Region Y but not X [3]

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: Temporary "virtual lesions" creating reversible dissociations in healthy participants [9]

- Behavioral Genetics: Showing different genetic influences on distinct cognitive processes

Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Double Dissociation Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Double Dissociation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Modalities | Structural MRI, fMRI, MRE, DTI | Anatomical localization, functional activation mapping, tissue property measurement, connectivity analysis |

| Brain Stimulation Methods | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), tDCS | Creating reversible "virtual lesions" to establish causal relationships |

| Lesion Mapping Software | Brainsight, MRIcron, FSL | Precise anatomical localization of lesions and their overlap with regions of interest |

| Cognitive Task Platforms | E-Prime, PsychoPy, Presentation, MATLAB | Implementing carefully matched behavioral tasks with precise timing control |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | R, SPSS, MATLAB with specialized toolboxes | Conducting dissociation analyses, controlling for multiple comparisons, managing power calculations |

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its logical power, the double dissociation approach faces several important challenges:

- Resource Artifacts: As noted by Shallice (1988), complementary dissociations across two patients alone may not suffice; additional evidence must rule out performance differences due to task difficulty rather than functional specialization [8]

- Neural Interconnectivity: The brain's highly interconnected nature means that "dissociable" systems may still interact extensively, creating challenges for interpreting selective deficits

- Rare Patient Populations: Finding patients with highly selective, focal lesions affecting specific brain regions can be challenging

- Underutilization in Psychiatry: A 2019 review found only 2% of psychiatric research publications examined double dissociations between neurobiological measures and clinical presentations, representing a significant missed opportunity [10]

The double dissociation method remains the gold standard for establishing specific structure-function relationships in cognitive neuroscience. By moving beyond simple correlation to demonstrate reciprocal patterns of sparing and impairment, this approach provides compelling evidence for functional specialization within the brain. Recent innovations in neuroimaging, brain stimulation, and lesion-symptom mapping have expanded the applications of this powerful methodology while maintaining its core logical rigor. As neuroscientific techniques continue to advance, the double dissociation framework will remain essential for translating brain-behavior correlations into meaningful causal explanations of cognitive architecture.

In neuropsychology, establishing specific brain-behavior relationships is fundamental to understanding how cognitive functions are organized in the brain. For decades, researchers have relied on dissociation methods to draw inferences about functional localization. Dissociation in neuropsychology involves identifying the neural substrate of a particular brain function through case studies, neuroimaging, or neuropsychological testing [11]. While the single dissociation approach provides initial evidence for functional independence, it is the more rigorous double dissociation methodology that offers conclusive evidence for separable cognitive processes and their distinct neural substrates. This guide objectively compares these methodological approaches, examining their experimental protocols, interpretive strength, and applications in contemporary neuroscience research.

Conceptual Foundations: Defining the Dissociation Methods

Single Dissociation

A single dissociation occurs when a researcher demonstrates that a lesion to brain structure A disrupts function X but not function Y [11]. This approach represents the initial step in dissecting complex mental tasks into their subcomponents, suggesting that functions X and Y may be independent in some way.

The classic example comes from patient D.F., described by Dr. Oliver Sacks, who was unable to consciously perceive and report the orientation of a slot but could successfully perform the motor action of posting a letter through it [11]. This suggested that visual perception and visuomotor control might involve separate systems. However, as Teuber [7] and Lashley [7] cautioned, single dissociations can lead to incorrect conclusions about functional localization because observed deficits could stem from differences in test sensitivity or demand rather than true brain-behavior specificity.

Double Dissociation

A double dissociation provides substantially stronger evidence for functional independence. This approach, introduced by Hans-Lukas Teuber in 1955 [11], demonstrates that two experimental manipulations each have different effects on two dependent variables [3]. Specifically, it requires showing that a lesion in brain area A impairs function X but spares Y, while a lesion in brain area B impairs function Y but spares X [11].

This methodological framework allows researchers to make more specific inferences about brain function and localization [11]. As Parkin explained, the distinction can be understood through a television analogy: "If your TV set suddenly loses the color you can conclude that picture transmission and color information must be separate processes (single dissociation)... If on the other hand you have two TV sets, one without sound and one without a picture you can conclude that these must be two independent functions (double dissociation)" [11].

Table 1: Key Conceptual Differences Between Single and Double Dissociation

| Feature | Single Dissociation | Double Dissociation |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Evidence Required | One patient with deficit in function X but not Y | Two patients with complementary deficits |

| Inferential Strength | Suggests possible independence | Demonstrates conclusive independence |

| Vulnerability to Artifacts | High (test difficulty differences) | Low (controls for task demands) |

| Localization Specificity | Limited | Strong |

| Historical Development | Early neuropsychological observations | Formalized by Teuber (1955) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Implementation

Single Dissociation Methodology

The single dissociation model tests whether a lesion is related to a specific cognitive function but not to another different function [7]. In practice, this involves:

- Patient Selection: Identifying individuals with focal brain lesions or specific neurological conditions

- Task Administration: Administering at least two behavioral tests assessing different cognitive functions

- Performance Analysis: Demonstrating impaired performance on Task A with preserved performance on Task B

The fundamental limitation of this approach is that differences in performance could result from variations in test sensitivity, cognitive demand, or measurement reliability rather than true dissociations in brain function [7]. A test might appear more sensitive to a particular lesion not because of functional specificity, but because it is simply more demanding of cognitive resources overall [3].

Double Dissociation Methodology

The double dissociation approach requires a more comprehensive experimental design:

- Participant Recruitment: Two or more patients/groups with different lesion locations or neurological conditions

- Task Battery: Administration of the same cognitive tasks to all participants

- Cross-Comparison: Demonstrating complementary patterns of impairment and preservation

Teuber's original framework for double dissociation involves comparing results of at least two tests for lateralizing damage applied to two hemispheres [3]. The critical insight is that it is the ratio between test scores, not absolute scores, that is crucial for localization [3].

Table 2: Experimental Requirements for Valid Dissociation Studies

| Methodological Element | Single Dissociation | Double Dissociation |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Patient Groups | 1 | 2 |

| Minimum Tasks | 2 | 2 |

| Control Group | Recommended | Essential |

| Task Difficulty Matching | Not required | Critical |

| Statistical Analysis | Comparison to norms | Crossed interaction analysis |

Case Studies: From Classical to Contemporary Evidence

Historical Foundations: Language Processing

The most celebrated historical example of double dissociation comes from 19th-century language research. Paul Broca's patients could understand language but not produce it (non-fluent aphasia), while Carl Wernicke's patients could produce speech but not comprehend it (fluent aphasia) [11]. Post-mortem examinations revealed lesions in separate brain areas - now known as Broca's area (left frontal cortex) and Wernicke's area (left temporoparietal cortex) [11] [7]. This double dissociation provided foundational evidence for separable neural systems underlying language production and comprehension.

Modern Evidence: Face Perception Pathways

Recent research has revealed a double dissociation between static and dynamic face perception, providing causal evidence for a third visual pathway dedicated to social perception [5]. In a comprehensive study of 108 patients with focal brain lesions:

- Patients with lesions to the right fusiform face area (FFA) and occipital face area (OFA) showed impaired static emotion recognition but preserved dynamic emotion recognition

- Patients with lesions to the right posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) demonstrated impaired dynamic emotion recognition but intact static recognition [5]

This clean double dissociation supports the existence of a visual pathway along the lateral brain surface, distinct from the traditional ventral ("what") and dorsal ("where") pathways, specifically dedicated to processing dynamic social cues [5].

Memory Systems Dissociation

Research on memory processes has demonstrated another robust double dissociation. Patients with Korsakoff's syndrome show severe explicit memory impairment with relatively intact implicit, procedural memory. Conversely, patients with Huntington's disease show the opposite pattern - preserved explicit memory but impaired implicit memory [7]. This dissociation supports the independence of neural systems supporting these memory forms, with Korsakoff's syndrome affecting thalamic regions and Huntington's disease impacting striatal regions [7].

Advanced Applications and Methodological Innovations

Neuroimaging Extensions

The logic of double dissociation has been successfully extended to neuroimaging studies. As Smith & Jonides explained: "If performance on Task A is associated with changed neural activity in Brain Region a but not Brain Region b, whereas performance on Task B is associated with changed neural activity in Region b but not Region a, then the two tasks are mediated by different processing mechanisms" [3].

A sophisticated example comes from magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) research, which measures brain tissue mechanical properties. Schwarb and colleagues demonstrated a double dissociation where hippocampal viscoelasticity predicted relational memory performance but not fluid intelligence, while orbitofrontal cortex viscoelasticity predicted fluid intelligence but not relational memory [4]. This illustrates how double dissociation logic can validate the specificity of structure-function relationships even with continuous neural measures.

Process-Based vs. Data-Based Limitations

Modern research has applied dissociation logic to distinguish between different types of processing limitations. A notable fMRI study demonstrated a dissociation between process-based limitations (straining attentional resources) and data-based limitations (impoverished sensory input) [12]. Only process-based limitations modulated activation in the parieto-frontal attention network, while data-based limitations primarily affected sensory processing regions [12]. This neural dissociation supports theoretical distinctions between these cognitive limitations.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dissociation Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Focal Lesion Patients | Natural experiments for brain-behavior relationships | Etiology, chronicity, and comorbidities must be documented |

| High-Resolution Neuroimaging | Lesion mapping and volumetric analysis | Enables precise anatomical localization |

| Standardized Cognitive Batteries | Assessment of multiple cognitive domains | Ensures reliability and comparability across studies |

| Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) | Measurement of brain tissue mechanical properties | Novel metric of tissue integrity beyond structure [4] |

| Lesion Symptom Mapping Software | Voxel-based statistical analysis of lesion-deficit relationships | Data-driven approach complementing ROI methods [5] |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation | Temporary, reversible "virtual lesions" | Causal inference without permanent damage |

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Advantages of Double Dissociation

The methodological superiority of double dissociation is demonstrated quantitatively across multiple research domains:

Diagnostic Specificity

In neuropsychological assessment, double dissociation provides the foundation for reliable test batteries. While single tests can only examine single dissociations, properly constructed batteries utilizing double dissociation logic can distinguish between types of pathologies or locations [3]. This is particularly important given that poor scores on a single test sensitive to a particular entity may result from multiple causes, including general brain damage [3].

Statistical Robustness

For a valid double dissociation, Shallice argued that it is insufficient to reveal two complementary dissociations on two patients [8]. Researchers must also demonstrate that both patients exhibit a complementary and significant difference between both tasks [8]. This empirical requirement implies a conjunction of four one-sided statistical alternative hypotheses, substantially strengthening inference beyond single dissociation approaches.

Localization Precision

Research on proper name retrieval demonstrates how double dissociation clarifies neural organization. While numerous cases showed impaired production of proper names with preserved common noun production, the reverse dissociation was harder to establish [8]. Martins and Farrajota eventually documented two patients providing clear double dissociation evidence - one with impaired object naming but spared proper name recall, and another with the opposite pattern [8]. This conclusive evidence supported distinct neural mechanisms for these lexical categories.

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that double dissociation provides superior methodological rigor compared to single dissociation approaches. While single dissociation offers initial suggestive evidence for functional independence, double dissociation delivers conclusive proof through complementary patterns of impairment and preservation. The methodological strength of double dissociation lies in its ability to control for confounding factors like differential task sensitivity and generalized performance deficits that plague single dissociation interpretations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing double dissociation logic - whether through lesion studies, neuroimaging, or neuromodulation techniques - provides the most compelling evidence for specific brain-behavior relationships. This approach has fundamentally advanced our understanding of functional specialization in language, memory, perception, and other cognitive domains. As neuroscience continues to develop increasingly sophisticated tools for assessing brain function, the logical rigor of double dissociation remains essential for validating claims about functional localization and independence.

Theoretical Foundations of Cognitive Modularity

The concept of cognitive modularity proposes that the mind is not a uniform system but is composed of specialized, domain-specific processing units. This framework is fundamental to understanding how brain damage can lead to highly specific cognitive deficits, providing a window into the functional architecture of the brain [13] [14].

Jerry Fodor's seminal 1983 work established core criteria for what constitutes a module. Fodorian modules are characterized as being:

- Domain-specific: They process only a specific type of information

- Informationally encapsulated: Their processing is isolated from other cognitive systems

- Mandatory in operation: They operate automatically when presented with relevant stimuli

- Hardwired: They have a fixed neural architecture

- Fast: Due to their specialized nature [13]

This view initially emphasized modular organization in perceptual and language systems while considering central cognitive systems (like reasoning) as non-modular [13].

Subsequent theories, notably Peter Carruthers' massive modularity hypothesis, extended the modular framework to encompass broader cognitive functions, suggesting that even high-level cognition is largely composed of specialized modules [13]. This perspective is supported by evolutionary psychology, which views the mind as a collection of adaptively specialized computational mechanisms designed to solve specific problems faced by our ancestors [15].

Modern neuroscience has refined these concepts through evidence of functional specialization within large-scale brain networks. Rather than strict one-to-one mapping between single brain areas and cognitive functions, current models propose that specialized functions emerge from interactions within networks of brain regions [13] [14]. The Moscovitch and Umiltà model further differentiates between levels of modularity: innate systems, genetically predisposed systems that develop over time, and hyper-learned systems acquired through executive attention and working memory [13].

Double Dissociation: The Gold Standard for Establishing Functional Dissociations

The double dissociation method provides critical evidence for validating modular architecture by demonstrating that two cognitive processes can be independently impaired.

Fundamental Principles and Methodology

A double dissociation is established when two patients (or patient groups) show opposite patterns of preserved and impaired abilities [16]:

- Patient/Group A is impaired on Task 1 but performs normally on Task 2

- Patient/Group B is impaired on Task 2 but performs normally on Task 1

This pattern provides stronger evidence for functional independence than single dissociation, as it rules out explanations based on task difficulty or general cognitive impairment [16]. The methodology assumes that if damage to different brain regions selectively affects different cognitive functions, these functions likely rely on distinct neural substrates and processing mechanisms [14].

Classic and Contemporary Experimental Paradigms

The logic of double dissociation originates from classic anatomical-clinical correlations. Broca's and Wernicke's seminal observations of language deficits associated with different lesion locations provided an early template: posterior inferior frontal lesions impaired speech production but spared comprehension, while posterior temporal lesions impaired comprehension but spared production [14].

Modern applications employ more sophisticated designs:

- Group comparison studies: Comparing performance across different patient etiologies (e.g., Alzheimer's disease vs. Parkinson's disease) on multiple cognitive tasks [16]

- Within-group heterogeneity analysis: Examining performance variations within a single clinical group to identify dissociable cognitive profiles [16]

- Parametric manipulation in neuroimaging: Using fMRI to isolate distinct brain networks sensitive to different task variables (e.g., notation vs. semantic distance in number processing) [15]

Table 1: Key Criteria for Valid Double Dissociation

| Criterion | Description | Methodological Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Independence | Two tasks probe distinct cognitive processes | Establishes that tasks measure different constructs rather than varying difficulty of the same construct |

| Selective Neural Correlates | Lesions/abnormalities affect different brain systems | Links functional dissociation to neuroanatomical distinctness |

| Task Reliability and Validity | Tasks consistently measure intended constructs | Ensures dissociations reflect true cognitive differences rather than measurement error |

| Matched Task Difficulty | Tasks are comparable in cognitive demands | Rules out explanations based on differential sensitivity to generalized impairment |

Experimental Protocols for Dissociation Research

Lesion Study Protocol for Double Dissociation

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for establishing double dissociations in patients with focal brain damage.

Participant Selection and Characterization:

- Recruit participants with clearly delineated, stable lesions (e.g., stroke, traumatic brain injury)

- Match participant groups on demographic variables (age, education), lesion volume, and time since injury

- Include comprehensive neurological and neuropsychological assessment to characterize general cognitive status

Task Development and Administration:

- Select or design tasks that tap putative distinct cognitive functions based on theoretical models

- Pilot tasks to ensure comparable difficulty levels and psychometric properties

- Administer tasks in counterbalanced order across multiple sessions to minimize practice effects

- Include control tasks to assess general cognitive abilities (attention, processing speed)

Data Analysis:

- Compare performance using standardized scores accounting for demographic factors

- Conduct dissociation analyses using multiple statistical approaches (e.g., ANOVA interaction effects, Crawford-Howell tests for single-case studies)

- Relate dissociation patterns to lesion characteristics using voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping or similar techniques

The following workflow illustrates the key stages of this experimental approach:

Neurodegenerative Disease Research Protocol

Neurodegenerative conditions offer unique opportunities to study dissociations as they affect distributed neural systems rather than producing focal damage [14].

Participant Selection:

- Recruit well-characterized patient groups with distinct neurodegenerative syndromes (e.g., semantic dementia, primary progressive aphasia, Alzheimer's disease)

- Use established diagnostic criteria and include biomarker confirmation when available

- Match groups on overall dementia severity using standardized measures (e.g., MMSE, CDR)

Assessment Approach:

- Administer comprehensive cognitive batteries targeting multiple domains (language, memory, executive functions, visuospatial skills)

- Include tasks with well-established neural correlates

- Obtain structural and/or functional neuroimaging to correlate cognitive profiles with neural integrity

Analysis Strategy:

- Compare cross-sectional profiles across patient groups

- Examine longitudinal trajectories to determine if dissociations persist over time

- Use multivariate techniques to identify clusters of associated and dissociated deficits

- Relate cognitive patterns to patterns of neural degeneration using voxel-based morphometry or similar techniques

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dissociation Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological Assessments | Western Aphasia Battery, Wechsler Memory Scale, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Standardized measurement of specific cognitive domains to establish dissociations |

| Lesion Mapping Software | MRIcron, FSL, SPM, VLSM toolboxes | Precise delineation and analysis of brain lesions to establish structure-function relationships |

| Statistical Packages for Single-Case Studies | Crawford & Howell t-test, SINGLISIS, BRGL | Specialized statistical methods for comparing individual patients to control groups |

| Cognitive Task Programming Platforms | E-Prime, PsychoPy, Presentation, MATLAB with Psychtoolbox | Creation and administration of experimental tasks with precise timing and response collection |

| Neuroimaging Acquisition Sequences | T1-weighted, FLAIR, DTI, resting-state fMRI | Visualization of structural damage and connectivity disruptions associated with cognitive deficits |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Different research methodologies offer complementary strengths for investigating modularity through dissociation logic.

Table 3: Comparison of Methodological Approaches in Modularity Research

| Methodology | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Lesion Studies | Examination of cognitive deficits following discrete brain damage | Strong causal inferences about brain necessity; clear anatomical correlates | Limited patient availability; lesions rarely respect functional boundaries; network effects | Establishing necessity of specific regions for cognitive functions; classic double dissociation |

| Neurodegenerative Disease Studies | Investigation of cognitive profiles in progressive disorders affecting neural systems | Reveals dissociations in gradually evolving systems; studies brain networks rather than focal areas | Progressive nature complicates interpretation; multiple system involvement | Understanding network-level organization; studying functions not typically disrupted by stroke |

| Functional Neuroimaging (fMRI, PET) | Measurement of brain activity during cognitive task performance | Identifies networks supporting cognitive functions; can study healthy brains | Correlational evidence; subtraction logic may oversimplify; indirect neural measure | Identifying neural correlates of cognitive components; testing predictions from lesion studies |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | Temporary disruption of neural processing in specific brain regions | Causality testing in healthy participants; excellent spatial and temporal precision | Superficial targets only; limited duration of effect; network-wide effects | Testing necessity of specific regions in healthy brains; establishing timing of processing |

The following diagram illustrates how these methodological approaches complement each other in building evidence for cognitive modularity:

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Future Directions

The modularity framework and dissociation approach have significant implications for drug development and clinical trials in neurology and psychiatry.

Target Validation and Biomarker Development:

- Cognitive dissociation paradigms help identify specific cognitive processes affected by neurological conditions, providing sensitive endpoints for clinical trials

- Understanding modular organization allows for development of drugs targeting specific neurotransmitter systems within defined cognitive networks

- Establishing cognitive profiles associated with different neurodegenerative pathologies aids in patient stratification for clinical trials

Treatment Efficacy Assessment:

- Double dissociation logic enables more precise measurement of treatment effects on specific cognitive domains rather than global cognitive scores

- Drugs can be tested for selective improvement of particular cognitive functions while leaving others unaffected, demonstrating targeted efficacy

- Cognitive dissociation patterns can serve as intermediate biomarkers for target engagement in early-phase trials

Future Methodological Developments:

- Integration of neuroimaging with cognitive testing to establish direct links between drug effects on neural systems and cognitive changes

- Use of computational modeling to generate precise predictions about how pharmacological modulation of specific neural systems should affect cognitive performance

- Development of more sophisticated cognitive batteries specifically designed to detect dissociations in clinical trial populations

The continued refinement of modularity theories and dissociation methodologies provides an essential foundation for developing more targeted and effective interventions for cognitive disorders. As our understanding of the neural implementation of cognitive modules advances, so too will our ability to develop precise pharmacological treatments that can selectively modulate dysfunctional cognitive systems while preserving normal functioning.

From Theory to Practice: Designing and Implementing Double Dissociation Studies

Classic experimental design serves as the foundational framework for establishing causal brain-behavior relationships in neuroscience and drug development research. This methodological approach provides the structural integrity necessary to isolate specific neural mechanisms and their corresponding behavioral manifestations. Within this context, the double dissociation method stands as a particularly rigorous experimental paradigm for validating hypothesized relationships between brain systems and behavior. Double dissociation designs demonstrate that one neural structure (A) is necessary for one cognitive function (X) but not another (Y), while a different neural structure (B) is necessary for function Y but not X. This approach provides compelling evidence for functional specialization within the brain, moving beyond simple correlational findings to establish dissociable neural systems.

The fundamental strength of classic experimental design lies in its systematic approach to variable management, control procedures, and measurement protocols. When properly implemented, this methodology enables researchers to draw valid conclusions about the efficacy of pharmaceutical interventions, the functional contributions of specific neural circuits, and the behavioral consequences of targeted manipulations. For drug development professionals, these designs provide the critical evidence base required for advancing compounds through clinical trial phases by establishing clear mechanistic relationships between molecular targets and cognitive or behavioral outcomes.

Essential Components of Classic Experimental Design

Experimental Variables: Definition and Operationalization

The precise definition and operationalization of variables constitutes the first critical component of any classic experimental design. Variables must be explicitly delineated from the study's inception to establish clear causal pathways and interpretable results [17].

- Independent Variables: These represent the manipulated factors under investigator control. In brain-behavior research, independent variables typically include the specific experimental intervention (e.g., drug administration, neural stimulation, lesion induction) or the controlled presentation of stimuli. Operationalizing these variables requires precise specification of dosage, stimulation parameters, or stimulus characteristics to ensure consistent application across experimental conditions [17].

- Dependent Variables: These measures capture the outcomes or effects resulting from manipulations of independent variables. In neuroscience contexts, dependent variables commonly include behavioral performance metrics (reaction time, accuracy), physiological measurements (fMRI activation, EEG rhythms), or biochemical assays (neurotransmitter levels, protein expression). The operational definition must specify exactly how these variables are quantified and recorded [17].

- Control Variables: These potentially confounding factors are held constant throughout the experiment to prevent them from influencing the results. In brain-behavior studies, control variables might include environmental conditions (lighting, time of testing), participant characteristics (age, education), or procedural consistency (apparatus, instructions) [17].

- Confounding Variables: These unmeasured or uncontrolled factors may inadvertently influence the relationship between independent and dependent variables, potentially compromising validity. Examples in pharmacological studies include metabolic differences, compensatory neural mechanisms, or experimenter expectations [17].

Table 1: Variable Types in Classic Experimental Design for Brain-Behavior Research

| Variable Type | Definition | Operationalization Examples in Brain-Behavior Research |

|---|---|---|

| Independent | The manipulated condition or intervention | Drug dosage (mg/kg), stimulation frequency (Hz), lesion coordinates (mm from bregma) |

| Dependent | The measured outcome | Reaction time (ms), percent correct (%), BOLD signal change (%), synaptic density (counts/mm²) |

| Control | Factors held constant | Time of testing, apparatus, ambient noise levels, experimenter |

| Confounding | Uncontrolled influencing factors | Circadian rhythms, stress levels, genetic background, prior experience |

Structural Building Blocks: Trials, Blocks, and Sessions

Classic experimental designs are constructed from hierarchical structural elements that organize the presentation of stimuli and collection of data. These building blocks provide the temporal framework within which brain-behavior relationships are quantified [17].

- Trials: A trial represents the fundamental unit of experimentation, typically consisting of a single instance of stimulus presentation, participant response, and data recording. In cognitive neuroscience, a trial might involve presenting a visual stimulus while recording both behavioral (button press) and neural (EEG) responses. Proper trial design ensures that each observation is independent and contributes meaningfully to the overall data set [17].

- Blocks: Blocks organize sequences of trials according to experimental logic, typically grouping trials with similar characteristics or requirements. Researchers utilize blocks to implement different experimental conditions, manage participant fatigue, or separate distinct phases of an experiment (e.g., practice, training, testing). In functional neuroimaging studies, block designs alternate periods of task performance with control conditions to identify neural systems engaged by specific cognitive processes [17].

- Sessions: Sessions represent distinct testing occasions separated by meaningful time intervals. Longitudinal designs employ multiple sessions to track developmental changes, learning effects, or therapeutic outcomes across days, weeks, or even months. In pharmacological studies, sessions might correspond to different drug administration timepoints or dose regimens, allowing researchers to examine temporal dynamics of drug effects on brain and behavior [17].

Experimental Design Configurations

The arrangement of participants across experimental conditions represents a critical design decision that directly impacts the validity and interpretability of brain-behavior research. The two primary approaches—between-subjects and within-subjects designs—offer complementary strengths for different research questions [17].

- Between-Subjects Design: Also known as independent measures design, this approach assigns participants to only one experimental condition or group. This configuration is essential when experimental manipulations produce irreversible effects (e.g., brain lesions) or when carryover effects between conditions would confound interpretation. Between-subjects designs are commonly employed in group comparison studies (e.g., patient population versus healthy controls) and in the initial phases of drug development to establish basic efficacy [17].

- Within-Subjects Design: Also called repeated measures design, this approach exposes participants to all experimental conditions, typically in counterbalanced order. This configuration provides maximum statistical power with fewer participants by controlling for individual differences. Within-subjects designs are particularly valuable in cognitive neuroscience, psychophysics, and studies of learning where tracking changes within individuals provides critical insights into dynamic brain-behavior relationships [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Between-Subjects and Within-Subjects Design Approaches

| Characteristic | Between-Subjects Design | Within-Subjects Design |

|---|---|---|

| Participant allocation | Each participant experiences only one condition | Each participant experiences all conditions |

| Required sample size | Larger | Smaller |

| Control for individual differences | Less control (requires randomization) | More control (each participant serves as own control) |

| Vulnerability to order effects | Not vulnerable | Vulnerable (requires counterbalancing) |

| Ideal application | Irreversible manipulations, group comparisons | Cognitive tasks, learning studies, when participants are scarce |

| Statistical power | Lower | Higher |

Control Parameters in Experimental Design

Randomization and Counterbalancing Procedures

Randomization serves as the cornerstone of experimental control, providing the primary safeguard against systematic bias and confounding. This methodological imperative involves the random assignment of participants to conditions, random ordering of trials, or random sequence of treatment administration [17].

- Random Assignment: In between-subjects designs, random assignment ensures that participant characteristics (both known and unknown) are distributed equally across experimental conditions. This procedure prevents systematic biases that could artificially create or mask true experimental effects. In drug development research, randomization is essential for valid clinical trials, ensuring that treatment and control groups are comparable at baseline [17].

- Counterbalancing: In within-subjects designs, counterbalancing systematically varies the order of condition presentation across participants to control for order effects, practice effects, and fatigue. Complete counterbalancing presents all possible sequences, while Latin square designs provide a more efficient partial counterbalancing approach. For complex behavioral tasks with multiple conditions, counterbalancing ensures that sequence effects do not confound the interpretation of condition differences [17].

Ensuring Semantic Equivalence in Experimental Comparisons

When comparing different experimental manipulations or measurement approaches, establishing semantic equivalence becomes essential for valid interpretation. This control parameter ensures that compared conditions differ only on the intended experimental dimension rather than on extraneous factors that might explain observed differences [18].

In the context of double dissociation designs, semantic equivalence requires that task pairs designed to tap separate cognitive processes are appropriately matched for difficulty, stimulus characteristics, and response demands. Without this equivalence, apparent dissociations might reflect general performance factors rather than specific functional specializations. For example, when comparing visual versus auditory processing, researchers must ensure that stimuli are equally discriminable and that tasks make comparable demands on attention, memory, and response selection [18].

Matching Compression Levels in Experimental Representations

The concept of compression level consistency extends from experimental design to data representation and analysis. Compression level refers to the degree to which information is condensed within a particular representation format. When comparing different measurement approaches (e.g., neuroimaging versus behavioral assessment), mismatched compression levels can create misleading conclusions [18].

For instance, if a highly compressed neural measure (e.g., fMRI block design) is compared with a finely detailed behavioral measure (e.g., trial-by-trial accuracy), apparent discrepancies might reflect different temporal resolution rather than true brain-behavior dissociations. Controlling for compression level requires aligning the granularity of measurement across domains to ensure valid comparisons [18].

The Double Dissociation Method: A Pinnacle of Experimental Design

Theoretical Foundations and Implementation

The double dissociation method represents one of the most rigorous applications of classic experimental design in brain-behavior research. This approach provides compelling evidence for functional independence of cognitive processes or neural systems by demonstrating complementary patterns of deficit or enhancement across two tasks and two populations (or manipulations) [17].

A prototypical double dissociation design requires:

- Two carefully selected tasks (X and Y) that purportedly tap distinct cognitive processes

- Two populations or manipulation conditions (A and B) that differentially affect these processes

- A crossover interaction pattern where manipulation A impairs performance on task X but not task Y, while manipulation B impairs performance on task Y but not task X

This pattern cannot be explained by general performance factors such as difficulty, motivation, or sensory requirements, and therefore provides strong evidence for functional specialization in the brain.

Methodological Requirements for Valid Double Dissociation

Implementing a convincing double dissociation requires meticulous attention to several methodological requirements beyond standard experimental controls:

- Process-Purity of Tasks: Each task must engage the cognitive process of interest with specificity, without substantial involvement of the process targeted in the other task.

- Matched Task Demands: Tasks must be carefully matched for difficulty, reliability, and psychometric properties to ensure that differential effects reflect qualitative rather than quantitative differences.

- Specificity of Manipulations: Neural manipulations (lesions, stimulation, pharmacological agents) must target distinct systems with minimal overlap to create the selective pattern of impairment.

- Additivity of Factors: The design assumes that the targeted cognitive processes contribute independently to task performance, without interactive effects that would complicate interpretation.

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure and expected outcomes of a valid double dissociation experiment:

Application in Pharmaceutical Research

In drug development, double dissociation designs provide critical evidence for mechanism-specific actions of candidate compounds. For example, a novel cognitive enhancer might be tested against both a cholinergic and a glutamatergic antagonist to demonstrate specific reversal of cholinergic deficits while having minimal effect on glutamatergic impairments. This pattern would support a specific cholinergic mechanism rather than general cognitive enhancement.

Similarly, double dissociation approaches can differentiate symptomatic relief from disease-modifying effects in neurodegenerative disorders by demonstrating differential patterns of improvement across cognitive domains and temporal trajectories of drug action.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for Double Dissociation Studies

Implementing a methodologically sound double dissociation experiment requires strict adherence to a standardized protocol with multiple validation checkpoints:

Task Selection and Validation Phase:

- Select candidate tasks with strong theoretical links to target cognitive constructs

- Conduct pilot studies to establish psychometric properties (reliability, validity)

- Adjust task parameters to achieve matched difficulty across tasks

- Confirm process-purity through manipulation checks

Participant Screening and Assignment:

- Establish clear inclusion/exclusion criteria based on theoretical rationale

- Implement random assignment to manipulation conditions (or carefully match patient groups)

- Conduct baseline assessments to ensure group equivalence on relevant dimensions

Experimental Implementation:

- Counterbalance task order across participants

- Standardize instructions, apparatus, and testing environment

- Implement quality checks for manipulation fidelity (e.g., lesion verification, drug levels)

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Conduct appropriate statistical tests (typically 2×2 ANOVA) to identify interaction pattern

- Perform follow-up simple effects analyses to confirm dissociation pattern

- Rule out alternative explanations through additional control analyses

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-phase experimental protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Brain-Behavior Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | Pharmacological manipulation of specific neurotransmitter systems | Establishing neurotransmitter involvement in cognitive processes |

| Cre-dependent Viral Vectors | Cell-type specific neural manipulation | Targeting specific neuronal populations in circuit dissection |

| Behavioral Testing Apparatus | Controlled presentation of stimuli and response collection | Standardized assessment of cognitive functions across subjects |

| Neurological Animal Models | Modeling disease states or specific neural alterations | Investigating neural mechanisms of cognitive deficits |

| Functional Imaging Agents | Visualization of neural activity or molecular targets | Correlating neural activity with behavioral performance |

| Data Analysis Software | Statistical analysis and visualization of complex datasets | Identifying significant patterns in brain-behavior data |

Comparative Experimental Data and Evidence Evaluation

Quantitative Comparison of Experimental Designs

The selection of appropriate experimental designs requires careful consideration of their relative strengths and limitations for specific research questions. The following table provides a comparative analysis of major design approaches in brain-behavior research:

Table 4: Quantitative Comparison of Experimental Designs in Brain-Behavior Research

| Design Type | Internal Validity | Statistical Power | Implementation Practicality | Resource Requirements | Ideal Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between-Subjects | Moderate | Lower | High | High (large N) | Group comparisons, irreversible manipulations |

| Within-Subjects | High | Higher | Moderate | Moderate | Cognitive processes, learning, scarce populations |

| Double Dissociation | Very High | High | Low | High | Establishing functional independence |

| Factorial Design | High | High | Moderate | High | Investigating multiple factors simultaneously |

| Mixed Design | High | High | Moderate | High | Combined within/between-subjects approaches |

Evaluating Evidence Strength in Experimental Outcomes

The strength of evidence derived from experimental designs varies systematically based on methodological rigor, control implementation, and analytical approach. Research conclusions exist along a continuum from preliminary observations to firmly established facts, with classic experimental designs providing the framework for advancing along this continuum [17].

Factors contributing to evidence strength include:

- Methodological Controls: The comprehensiveness of control conditions and variables

- Manipulation Specificity: The precision with which independent variables target theoretical constructs

- Measurement Reliability: The consistency and precision of dependent measures

- Statistical Power: The ability to detect true effects when they exist

- Replicability: The consistency of findings across repeated experiments

- Theoretical Coherence: The fit with existing knowledge and explanatory frameworks

Double dissociation designs typically generate strong evidence because they eliminate numerous alternative explanations through their crossover interaction pattern and require multiple convergent operations. This evidential strength makes them particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development, where conclusive demonstration of mechanism is required for regulatory approval and clinical application [17].

Classic experimental design, with its essential components of defined variables, hierarchical structure, and rigorous controls, provides the indispensable foundation for valid brain-behavior research. The double dissociation method represents one of the most powerful implementations of this approach, enabling researchers to establish functional specialization within neural systems with a degree of certainty unmatched by simpler correlational or single dissociation approaches.

For drug development professionals and neuroscientists, mastery of these design principles is not merely academic but fundamentally practical. The validity of conclusions about drug mechanisms, neural circuits, and cognitive processes depends directly on the integrity of the experimental designs through which these phenomena are investigated. As research questions grow increasingly complex and interventions become more targeted, the classic experimental design principles outlined here will continue to provide the methodological bedrock for scientific advances in understanding brain-behavior relationships.

In neuroscience research, particularly for validating brain-behavior relationships, the selection of appropriate patient populations is paramount. Studies of humans with focal brain damage provide pivotal causal insights into the neural basis of behavior that cannot be achieved through correlative methods alone [19]. Unlike functional neuroimaging which shows where a cognitive process is associated with brain activity, lesion studies can demonstrate that a brain region is necessary for that specific cognitive process [19]. This distinction is crucial for drug development professionals targeting specific neurological mechanisms, as it helps differentiate merely correlated brain activity from genuinely essential neural substrates.

The principle of double dissociation provides particularly compelling evidence for functional specialization within the brain. A single dissociation occurs when a lesion in region X impairs function A but not function B. A double dissociation requires demonstrating the complementary pattern: that a lesion in region Y impairs function B but not function A [8]. This methodological approach offers strong evidence for the functional independence of cognitive processes and their underlying neural circuitry, making it invaluable for establishing valid targets for therapeutic intervention.

Comparative Analysis of Lesion Analysis Methods

The table below compares two fundamental approaches to patient group selection and analysis in neurological populations:

Table 1: Comparison of Lesion Analysis Approaches for Patient Group Selection

| Analysis Feature | Lesion-Centered Approach | Severity-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|