Ecological Validity in Virtual Reality: Advancing Naturalistic Neuroscience for Research and Drug Development

This article explores the critical role of ecological validity in virtual reality (VR) paradigms for naturalistic neuroscience research.

Ecological Validity in Virtual Reality: Advancing Naturalistic Neuroscience for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of ecological validity in virtual reality (VR) paradigms for naturalistic neuroscience research. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it examines how VR bridges the gap between controlled laboratory settings and real-world complexity while maintaining experimental rigor. The content covers foundational theories, methodological applications across clinical and cognitive domains, optimization strategies for enhanced validity, and comparative validation approaches. By synthesizing current evidence and frameworks, this article provides practical guidance for implementing ecologically valid VR simulations to improve the predictive power of neuroscience findings and accelerate therapeutic development.

Bridging Real Worlds and Virtual Labs: The Foundation of Ecological Validity in Neuroscience

Ecological validity, a cornerstone of rigorous experimental design, measures the extent to which scientific findings can be generalized from controlled laboratory settings to real-world conditions. In the burgeoning field of naturalistic neuroscience, virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a pivotal technology, offering a unique middle ground that balances experimental control with the richness of naturalistic environments [1]. This whitepaper delineates the theoretical framework of ecological validity, evaluates VR's capacity to emulate real-world conditions through verisimilitude and veridicality, and provides a detailed analysis of experimental methodologies and neurophysiological metrics for researchers and drug development professionals. By integrating quantitative data on perceptual, psychological, and physiological responses, we present a comprehensive toolkit for designing ecologically valid VR paradigms that can reliably predict real-world cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

Ecological validity originated in psychological research to describe the generalizability of laboratory findings to real-world settings [2]. In modern neuroscience, this concept has become increasingly critical as researchers recognize the limitations of traditional, highly controlled paradigms. These paradigms, while excellent for isolating variables, often fail to capture the dynamic, multimodal, and interactive nature of real-world perception and behavior [1]. The resulting "ecological validity gap" can limit the translational potential of neuroscientific discoveries, particularly in drug development where predicting real-world efficacy is paramount.

Virtual reality (VR) presents a powerful solution to this challenge. By creating immersive, interactive simulations, VR allows researchers to maintain precise experimental control while eliciting more naturalistic behaviors and neural responses [1]. In its application to neuroscience, VR is defined as a technique that induces targeted behavior through artificial sensory stimulation, featuring a closed-loop system where the participant's actions determine the sensory input they receive [1]. This interactive experience is fundamental to its ecological advantage over conventional passive-stimulus paradigms.

Theoretical Framework: Verisimilitude and Veridicality

The ecological validity of VR experiments is quantitatively assessed through two complementary approaches: verisimilitude and veridicality [2]. These frameworks provide researchers with distinct yet interconnected metrics for validating their paradigms.

Verisimilitude: The Similarity of Task Demands

Verisimilitude refers to "the similarity between the task demands of the test and the demands imposed in everyday life" [2]. It evaluates how closely an experimental setting resembles the real world in terms of the cognitive, perceptual, and motor challenges presented to the participant. In VR research, verisimilitude is often measured through subjective participant ratings on dimensions such as:

- Immersion: The feeling of being present in the virtual environment.

- Realism: The perceived authenticity of the environment and events.

- Audio and Video Quality: The fidelity of sensory presentation.

Veridicality: The Empirical Relationship with Real-World Functioning

Veridicality refers to "the degree to which existing tests are empirically related to measures of real-world functioning" [2]. This approach requires direct comparison between data collected in laboratory settings (including VR) and data collected in actual real-world situations or in-situ experiments. Veridicality is established when statistical analyses show no significant differences or strong correlations between laboratory and real-world measurements across perceptual, psychological, and physiological domains.

Table 1: Comparative Ecological Validity of VR Setups Across Measurement Domains

| Measurement Domain | Specific Metrics | Cylinder Room-Scale VR | Head-Mounted Display (HMD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptive Parameters | Soundscape perception, Landscape perception [2] | Ecologically valid [2] | Ecologically valid [2] |

| Psychological Restoration | Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS), Restorative Outcome Scale (ROS) [2] | Moderate ecological validity [2] | Limited ecological validity [2] |

| Physiological - Heart Rate | HR change rate from stressor [2] | Shows promise for ecological validity [2] | Shows promise for ecological validity [2] |

| Physiological - EEG | Time-domain features [2] | More accurate representation of real-world conditions [2] | Less accurate for time-domain features [2] |

| Physiological - EEG | Change metrics, Asymmetry features [2] | Shows promise for ecological validity [2] | Shows promise for ecological validity [2] |

Experimental Protocols for VR-Based Naturalistic Neuroscience

Implementing ecologically valid VR experiments requires meticulous protocol design that balances immersive naturalism with scientific rigor. The following methodologies, drawn from recent studies, provide frameworks for investigating diverse neuroscientific questions.

Protocol: Assessing Audio-Visual Environment Responses

Objective: To evaluate the ecological validity of VR experiments for assessing human perceptual, psychological, and physiological responses to audio-visual environments [2].

- Experimental Design: A 2×3 within-subject design, incorporating two testing sites (e.g., a garden and an indoor space) and three experimental conditions: in-situ (real-world), room-scale cylindrical VR environment, and Head-Mounted Display (HMD) VR [2].

- Stimuli: Environments should represent different categories (natural, semi-natural, artificial) and contain diverse audio-visual elements to test generalizability [2].

- Procedure:

- Pre-Exposure Baseline: Record physiological baseline measures (e.g., EEG, HR) during an initial resting state.

- Stressor Task: Administer a standardized cognitive stressor (e.g., serial subtraction) to induce physiological arousal.

- Environmental Exposure: Participants experience each environmental condition (in-situ, cylinder VR, HMD) in counterbalanced order.

- Post-Exposure Assessment: Collect self-reported perceptions and psychological restoration metrics.

- Data Collection:

- Perception & Psychology: Questionnaire-based metrics for audio quality, video quality, immersion, realism, and psychological restoration (e.g., Perceived Restorativeness Scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) [2].

- Physiological: Continuous HR monitoring and EEG recordings throughout the experiment. EEG data should be processed into frequency bands (theta: 4-8 Hz, alpha: 8-14 Hz, beta: 14-30 Hz) for analysis of power spectral density and asymmetry features [2].

- Analysis: Compare results across the three conditions using repeated-measures ANOVA to determine veridicality. Verisimilitude is assessed through subjective ratings of immersion and realism.

Protocol: Investigating Naturalistic Eye and Head Movements

Objective: To study vision in tandem with natural movement by capturing eye and head tracking data during a visual discrimination task in VR [3].

- Apparatus: Unity game engine for stimulus presentation, HTC Vive VR headset with integrated eye tracking (120Hz sampling), and Lab Streaming Layer for synchronizing eye/head tracking data with stimulus presentation and behavioral responses [3].

- Stimuli: Simplified visual discrimination targets presented in a 3D virtual space, allowing strict control over stimulus timing and location while permitting unrestricted eye and head movements [3].

- Procedure:

- Calibration: Implement a 5-point calibration using the eye tracker's SDK before each experimental block.

- Task: Participants perform a visual discrimination task requiring foveation of both static and moving stimuli.

- Data Recording: Synchronously capture gaze direction, head rotation, head position, and behavioral responses.

- Data Analysis: Classify eye movements using threshold-based algorithms (I-S5T) adapted for 3D environments. Key movement categories include saccades, fixations, smooth pursuit, vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), and head pursuit [3].

Protocol: Examining Cognitive Efficiency in Nature-Inspired VR Environments

Objective: To investigate neurophysiological and affective responses to nature-inspired indoor design elements and their effects on cognitive performance [4].

- Experimental Design: Within-subject design where participants experience one control condition (neutral interior) and three experimental conditions (curvilinear forms, nature views, wooden interiors) in counterbalanced order [4].

- Environment Design: Pre-model 3D virtual interiors using software such as Unity or Unreal Engine, systematically varying architectural elements while controlling for confounding variables like lighting and spatial volume.

- Procedure:

- Environmental Exposure: Participants experience each virtual environment for a standardized duration.

- EEG Recording: Continuous EEG recording during environmental exposure to capture neurophysiological responses.

- Affective Assessment: Self-reported ratings of relaxation and emotional valence after each condition.

- Cognitive Assessment: Administration of standardized cognitive tasks (e.g., attention tests, working memory tasks) following exposure to each environment.

- Data Analysis:

- EEG Indicators: Calculate alpha-to-theta ratio (ATR) in frontal region, theta-to-beta ratio (TBR) in frontal region, and alpha-to-beta ratio (ABR) in occipital region [4].

- Statistical Analysis: Use repeated-measures ANOVA to compare conditions, followed by post-hoc comparisons to identify specific differences between nature-inspired and control environments.

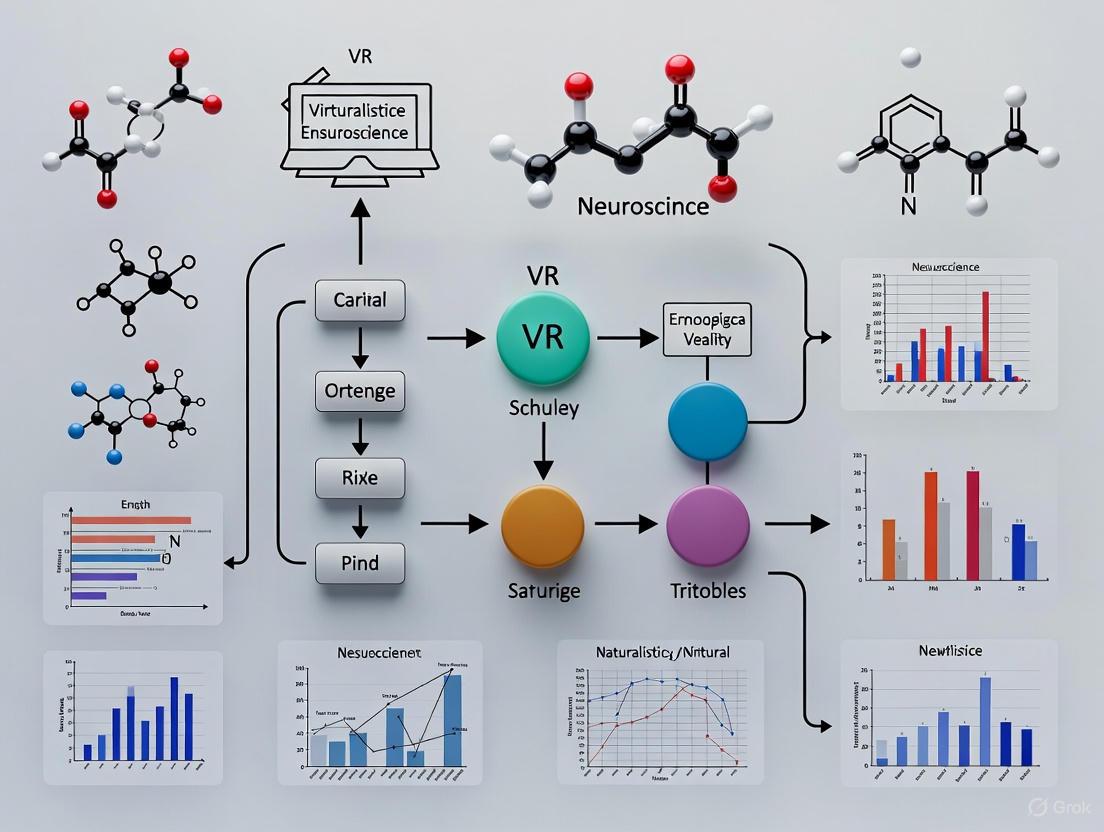

Experimental Workflow for VR Ecological Validity Research

Quantitative Neurophysiological and Behavioral Metrics

Establishing ecological validity requires objective, quantifiable metrics that can be compared across real and virtual environments. Electroencephalography (EEG) provides particularly valuable biomarkers for assessing neural states during VR experiences.

Table 2: Key EEG Metrics for Assessing Cognitive States in VR Environments

| EEG Metric | Frequency Band Definition | Cognitive Correlate | Response in Naturalistic VR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-to-Theta Ratio (ATR) [4] | Alpha (8-14 Hz) / Theta (4-8 Hz) | Relaxed attentional engagement; internal attention [4] | Significantly increased in wooden interiors versus control condition [4] |

| Theta-to-Beta Ratio (TBR) [4] | Theta (4-8 Hz) / Beta (14-30 Hz) | Attentional control; mental workload [4] | Decreased in wooden interiors, indicating improved attentional engagement [4] |

| Alpha-to-Beta Ratio (ABR) [4] | Alpha (8-14 Hz) / Beta (14-30 Hz) | Relaxed yet alert state [4] | Increased in wooden interiors, suggesting calm alertness [4] |

| Frontal Alpha Asymmetry [2] | Difference in alpha power between right and left frontal hemispheres | Approach-withdrawal motivation; emotional valence [2] | Shows promise for ecological validity in both HMD and cylinder VR [2] |

| EEG Change Metrics [2] | Percentage change from baseline in band power | General reactivity to environmental stimuli [2] | Shows promise for ecological validity in both HMD and cylinder VR [2] |

Implementing ecologically valid VR neuroscience research requires specialized equipment and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key resources and their applications in naturalistic paradigms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for VR Neuroscience

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) with Integrated Eye Tracking [3] | Presents immersive virtual environments while capturing gaze behavior and head movements. | HTC Vive with Tobii eye tracking (120Hz sampling, 0.5° estimated accuracy) [3] |

| Game Engine for Stimulus Presentation [3] | Creates and renders controlled, interactive 3D environments for experimental paradigms. | Unity or Unreal Engine [3] |

| Data Synchronization Software [3] | Integrates multiple data streams (eye tracking, EEG, behavioral responses) with sub-millisecond precision. | Lab Streaming Layer (LSL) [3] |

| Wireless EEG System [4] | Records neural activity during unrestricted movement in VR environments, capturing cognitive states. | Research-grade systems with appropriate channel counts for spectral analysis [4] |

| Heart Rate Monitor [2] | Measures cardiovascular activity as an indicator of physiological arousal and restoration. | Consumer-grade or research-grade sensors with continuous recording capability [2] |

| Eye Movement Classification Algorithm [3] | Identifies and categorizes naturalistic eye movements (saccades, pursuit, VOR) from raw gaze data. | I-S5T algorithm adapted for VR, thresholding eye, head, and gaze speed [3] |

Technological Considerations and Methodological Constraints

The successful implementation of ecologically valid VR paradigms requires careful consideration of technological limitations and methodological constraints that may impact data quality and interpretation.

Vestibular Mismatch and Spatial Coding

A significant challenge in VR neuroscience involves conflicts between visual and vestibular information, particularly in head-fixed or body-fixed rodent experiments. These conflicts can alter the firing patterns of spatially tuned neurons, with studies showing that place cells in the hippocampus demonstrate different position coding when vestibular input is disrupted [1]. This limitation can be mitigated through freely-moving VR setups [1] or systems that do not restrict body rotations, thereby preserving normal vestibular feedback about rotational movements [1].

Measurement Accuracy and Data Quality

The use of consumer-grade sensors for physiological measurement, while increasing accessibility, may impact data accuracy. These sensors, though validated for reliability, typically offer lower precision than research-grade equipment, potentially introducing measurement errors or variability [2]. Researchers must balance practical considerations with data quality requirements based on their specific research questions and analytical needs.

Stimulus Control Versus Behavioral Freedom

A fundamental tension in VR experimental design exists between maintaining precise stimulus control and allowing naturalistic behavioral responses. While HMDs with eye tracking permit more natural movement of eyes and head compared to traditional monitor setups [3], participants are typically more limited in overall mobility, often relying on unnatural navigation methods like teleportation to maintain position within the headset-tracking volume and avoid collisions [3].

VR as a Balance Between Control and Naturalism

Virtual reality represents a transformative methodological approach in naturalistic neuroscience, offering a scientifically rigorous pathway to bridge the ecological validity gap between laboratory control and real-world generalization. By systematically applying the frameworks of verisimilitude and veridicality, researchers can design VR paradigms that maintain experimental precision while eliciting naturally relevant behaviors and neural responses. The integration of neurophysiological metrics, particularly EEG biomarkers of cognitive state, provides objective means to validate these paradigms and establish their predictive power for real-world functioning.

For drug development professionals, ecologically valid VR paradigms offer promising platforms for evaluating cognitive and behavioral effects of pharmacological interventions in environments that more closely mirror real-world conditions than traditional laboratory tasks. This enhanced predictive validity may accelerate development cycles and improve success rates in clinical translation. Future research should focus on standardizing VR protocols across research sites, developing more sophisticated analytical approaches for naturalistic behavioral data, and addressing current technological limitations in sensory feedback and mobility. As VR technology continues to advance, its role in closing the ecological validity gap will undoubtedly expand, offering unprecedented opportunities to understand brain function in contexts that matter for real-world health and performance.

For decades, neuroscience research has been defined by a fundamental methodological tension: the struggle between experimental control and ecological validity. This dichotomy has shaped research design, interpretation, and the generalizability of findings. On one side, traditional laboratory approaches prioritize precise manipulation of variables in simplified, highly controlled environments to establish causal mechanisms [5]. On the other, ecological validity emphasizes the study of behavior and brain function in contexts that resemble real-world situations, ensuring that findings generalize beyond the laboratory [6]. This article examines how virtual reality (VR) technologies are bridging this historical divide, creating a middle ground that maintains experimental rigor while capturing the complexity of naturalistic behaviors.

The ecological validity debate gained significant traction in 1978 when Neisser criticized cognitive psychology experiments as occurring in artificial settings with measures bearing little resemblance to everyday life [5]. Counterarguments from Banaji and Crowder (1989) emphasized that ecological approaches lacked the internal validity and experimental control necessary for scientific progress, creating a schism in the field [5]. This debate has been particularly pronounced in clinical neuroscience, where the limitations of generalizing sterile laboratory findings to patients' everyday functioning have significant practical implications for assessment and treatment [5].

Defining the Contours of the Debate

Ecological Validity Frameworks

In clinical neuroscience, ecological validity has been refined through two distinct requirements: veridicality and verisimilitude [5]. Veridicality refers to the ability of a patient's performance on a neuropsychological measure to predict some feature of their day-to-day functioning (e.g., vocational status). Verisimilitude describes how closely the requirements of a neuropsychological measure and testing conditions resemble those found in a patient's activities of daily living [5].

Limitations of Traditional Approaches

Traditional neuropsychological assessments often fall short of ecological validity despite their experimental robustness. Tests such as the Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST) and Stroop test were developed to assess cognitive constructs without regard for their ability to predict functional behavior [5]. While valuable for measuring specific cognitive constructs like set shifting or response inhibition, their connection to real-world functioning remains tenuous. For instance, impaired performance on the Stroop test may suggest difficulties with inhibiting prepotent responses, but it provides limited insight into whether a patient can safely navigate complex traffic situations [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Laboratory Paradigms vs. Naturalistic Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Laboratory Paradigms | Naturalistic Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Characteristics | Simple, static, unimodal | Complex, dynamic, multimodal |

| Participant Role | Passive perception | Active exploration & interaction |

| Environmental Context | Artificial, sterile | Contextually embedded |

| Task Structure | Highly constrained, repetitive | Flexible, goal-directed |

| Generalizability | High internal validity, limited ecological validity | High ecological validity, potential confounds |

Virtual Reality as a Methodological Bridge

Theoretical Foundations of VR in Neuroscience

Virtual reality represents a transformative methodology that simultaneously addresses both sides of the historical tension. VR creates artificial environments where participants' actions determine sensory stimulation, establishing a closed-loop between stimulation, perception, and action [7]. This interactive experience stands in stark contrast to conventional laboratory settings characterized by numerous repetitions of the same imposed stimuli, often directed to only a single sense and disconnected from the animal's responses [7].

VR is defined as "inducing targeted behavior in an organism by using artificial sensory stimulation, while the organism has little or no awareness of the interference" [7]. For neuroscientific applications, the critical feature is that the virtual world updates based on the user's behavior in real time, creating an interactive experience that distinguishes VR from simple sensory stimulation [7]. This capacity enables researchers to present dynamic stimuli concurrently or serially in a manner that allows assessment of integrative processes carried out by perceivers over time [5].

Key Advantages of VR for Neuroscience Research

VR offers three primary advantages for neuroscientific research that bridge the ecological validity-control divide:

Multimodal stimulation with flexible and precise control: VR provides control over environmental complexity without physical space restrictions. Researchers can systematically add or remove cues to test their contribution to neural activity or behavior without influencing other environmental components [7].

Interactivity instead of purely passive perception: Natural behavior is characterized by active exploration and interrogation of the environment, where attention is selected and specifically probed according to motivations and needs [7]. VR captures this essential feature through closed-loop design.

Compatibility with neural recording techniques: VR enables behavioral testing while using recording apparatuses that require stability unavailable during free movement [7]. This allows for rigorous neural measurement during ecologically valid tasks.

Methodological Framework for Ecological Validity

Evaluating Ecological Validity in Study Design

A proposed framework for evaluating ecological validity in memory and event cognition research considers the alignment between task settings and the complexity of target cognitive phenomena [6]. This framework suggests that:

- For cognitive processes involving few fundamental computations, simplified laboratory tasks with high experimental control remain appropriate and valid.

- For complex, multiple interacting higher-order processes, more naturalistic tasks that better approximate real-world contexts are necessary for ecological validity [6].

This framework emphasizes that the relevance of materials alone is insufficient for ecological validity; the complexity of the cognitive phenomenon must align with the naturalism of the task settings [6].

Experimental Design Guidelines

Based on this framework, researchers can apply these guidelines when designing ecologically valid studies:

Identify complexity: Determine whether the cognitive process under investigation involves fundamental computations or multiple interacting higher-order processes [6].

Task design: Ensure the task closely resembles the real-world scenario in which the cognitive process would typically operate, particularly for complex phenomena [6].

Stimulus selection: Use stimuli that are dynamic, multimodal, and contextually embedded when studying complex, everyday cognitive processes [6].

Response measures: Record not only accuracy but also other characteristics like response time, eye movements, and neural activity that provide richer information about cognitive processing [6].

Table 2: VR-Enhanced Assessment Domains in Neuroscience

| Research Domain | Traditional Assessment Limitations | VR-Enhanced Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Navigation | Limited by physical space; conflicts between vestibular and visual information in rodent VR [7] | Large-scale environment simulation; path integration studies [7] |

| Clinical Neuropsychology | Paper-and-pencil tests lack predictive validity for real-world functioning [5] | Simulation of daily living activities and social interactions [8] |

| Social Neuroscience | Static, decontextualized stimuli fail to capture dynamics of social interaction [5] | Emotionally engaging narratives enhancing affective experience [5] |

| Memory Research | Simple, artificial stimuli lacking real-world context [6] | Naturalistic scenarios using lifelogging and extended reality technologies [6] |

Implementation and Applications

VR in Clinical Neuroscience Assessment

VR technologies address significant limitations in traditional neuropsychological assessment by creating simulations that mirror real-world demands while maintaining measurement precision. The shift from "construct-driven" to "function-led" assessments represents a crucial advancement in clinical neuroscience [5]. Rather than measuring isolated cognitive constructs, function-led tests proceed from directly observable everyday behaviors backward to examine how action sequences lead to behavior in normal functioning and how that behavior becomes disrupted [5].

For example, the ACME VR paradigm demonstrates how VR can maintain high experimental control while creating realistic scenarios to investigate complex psychological phenomena like work-related objectification [9]. This paradigm compares an assembly line task (characterized by repetitiveness and fragmentation) with a woodworking task (emphasizing autonomy and holistic engagement) to study how task characteristics influence self-objectification [9]. The paradigm successfully induced higher self-objectification in the assembly line scenario while maintaining satisfactory usability and user experience, validating VR's capacity to replicate complex workplace dynamics [9].

Naturalistic Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory

The landscape of human memory research has transformed from using abrupt, artificial stimuli to employing naturalistic tasks that better represent real-world contexts [6]. This shift responds to concerns that insights into higher-order cognition from highly contrived experimental conditions may not generalize well to more naturalistic settings [6].

Modern approaches leverage technologies like lifelogging (comprehensive personal archives of everyday experiences) and extended reality to enhance ecological validity without sacrificing experimental control [6]. These technologies allow researchers to study memory in contexts that closely resemble real-life situations, engaging neural processes similar to those used in daily functioning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for VR-Enhanced Naturalistic Neuroscience

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | Head-mounted displays (HMDs), Cave Automatic Virtual Environments (CAVEs) | Create immersive sensory experiences with varying levels of immersion [7] [5] |

| Tracking Systems | Motion capture, Eye-tracking, Physiological monitoring | Capture behavioral, physiological, and neural responses during immersive tasks [8] |

| Software Environments | Unity, Unreal Engine, Ouvrai | Design and implement controlled virtual environments with precise stimulus manipulation [10] |

| Stimulus Modalities | 360° videos, Computer-generated environments, Spatial audio | Create multimodal simulations of real-world contexts with varying complexity [8] |

| Data Analysis Frameworks | Automated logging systems, Mobile brain recording integration | Process complex behavioral, physiological, and neural datasets acquired in naturalistic contexts [5] [6] |

Visualizing the VR Bridge in Neuroscience Research

VR as Methodological Bridge

The historical tension between experimental control and ecological validity in neuroscience is being productively resolved through technological and methodological innovations. Virtual reality represents a transformative approach that combines the precision of laboratory control with the meaningful context of real-world environments. By creating closed-loop systems where sensory stimulation dynamically responds to participant behavior, VR enables researchers to study complex cognitive processes as they naturally occur while maintaining the rigorous experimental control necessary for neuroscientific investigation.

As VR technologies continue to advance, their integration with mobile brain recording techniques and sophisticated data analysis frameworks will further enhance our capacity to understand brain function in ecologically valid contexts. This methodological shift promises not only to bridge a historical divide in neuroscience but also to improve the translation of research findings to real-world applications across clinical, affective, and social domains.

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in neuroscience, striking a critical balance between the controlled conditions of the laboratory and the ecological validity of real-world environments [1]. Traditional neuroscience paradigms often rely on numerous repetitions of simplified, artificial stimuli directed to a single sense, which are disconnected from the subject's natural responses [1]. This approach, while valuable for isolating variables, suffers from limited ecological validity and may not reveal the true neural mechanisms underlying natural behavior [1]. In contrast, naturalistic neuroscience seeks to study brain function under conditions that more closely mimic real-world experiences, utilizing complex, dynamic, and multimodal stimuli [11]. VR stands at the intersection of these approaches, offering a middle ground by creating interactive, immersive simulations that maintain a high degree of experimental control [1] [12]. This whitepaper explores the role of VR in advancing naturalistic neuroscience paradigms, detailing its theoretical basis, empirical support, methodological protocols, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Conceptual Framework: VR as a Bridging Technology

Defining Ecological Validity in Neuroscientific Context

In the context of VR and neuroscience, validity is multifaceted. Ecological validity is a specific type of external validity referring to the degree to which experimental findings reflect real-world phenomena [12]. It is distinct from, yet related to, internal validity (the local consistency of a simulation) and external validity (consistency with external observations) [12]. Two primary approaches are used to assess ecological validity:

- Verisimilitude: The similarity between the task demands of the test and the demands imposed in the everyday environment.

- Veridicality: The degree to which test results are empirically related to measures of real-world functioning [13].

The Closed-Loop Advantage of VR

A defining characteristic of VR is its closed-loop nature. Unlike traditional passive stimulation paradigms, VR creates an interactive experience where the participant's actions determine the sensory stimulation, establishing a continuous feedback cycle between stimulation, perception, and action [1]. This interactivity is a fundamental aspect of natural behavior, which involves active exploration and interrogation of the environment [1]. This closed-loop design is crucial for inducing a psychological state of "presence"—the subjective perception of existing within the virtual environment—which forms the basis for ecological validity [12].

Empirical Evidence: Quantifying VR's Ecological Validity

Recent systematic reviews and experimental studies have aggregated evidence on the performance of VR simulations across different behavioral domains relevant to neuroscience and occupational safety.

Table 1: Ecological Validity of VR Across Behavioral Domains

| Behavioral Domain | Key Findings on Ecological Validity | Correlational Strength with Real-World Behavior | Primary Technological Mediators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Perception & Navigation | Alterations in hippocampal place cell firing reported in body-fixed VR due to vestibular-visual mismatch; normal firing patterns restored in setups permitting free rotation [1]. | Variable (Low to High) | Vestibular congruence, freedom of movement, rotational tracking [1] |

| Movement Kinematics | High similarity in movement patterns and postures between real and virtual environments for industrial tasks; minor but statistically significant differences in joint angles and task completion times [12]. | High | Latency, display resolution, field of view, haptic feedback [12] |

| Stress & Risk Perception | Effective for evoking phobic responses and fear; shows promise for simulating hazardous industrial situations; subjective risk perception may be lower than in real equivalents [12]. | Moderate to High | Immersion level, visual fidelity, narrative context [12] |

| Cognitive Assessment | Useful for assessing memory, attention, and executive function in context-rich scenarios; shows high subject engagement and reproducibility of brain responses [13] [11]. | High | Task design, environmental complexity, multimodal integration [13] |

Table 2: Impact of Technical Factors on Ecological Validity in Soundscape/Landscape Research

| Experimental Factor | Condition with Higher Ecological Validity | Quantitative Effect on Ecological Validity (Descriptor/Index) | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auralization: Sound Level | Adjusted level of -8 dB relative to in-situ recording [13] | Optimized Veridicality | An adjustment of -8 dB was found to yield the highest congruence between laboratory and real-world perceptual ratings [13]. |

| Auralization: Audio Method | Ambisonics and Synthesis [13] | Significantly Higher vs. Monoaural | Both ambisonics (spatially recorded) and synthesized audio showed superior ecological validity compared to monoaural recording [13]. |

| Visualization: Method | 3D Video [13] | Higher Verisimilitude | 3D video provided a higher level of verisimilitude; however, 3D modelling paired with ambisonics audio showed comparable potential [13]. |

| Human-Computer Interaction | Virtual Walking [13] | Significant Enhancement | The inclusion of virtual walking, as an exploratory movement, showed great potential to significantly enhance ecological validity [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating VR Paradigms

To ensure that VR paradigms provide scientifically valid data, researchers must employ rigorous validation methodologies. The following protocol, derived from recent research, provides a template for establishing ecological validity.

A Three-Step Experimental Validation Method

A robust method for assessing ecological validity involves a three-step experimental procedure [13]:

- Step 1: Parameter Calibration. This initial phase aims to identify optimal baseline parameters for the VR simulation. For instance, a within-subjects experiment can be conducted to determine the sound level that yields the highest congruence between VR and real-world perceptual ratings. As highlighted in Table 2, one study found that an adjustment of -8 dB relative to the in-situ recording optimized ecological validity [13].

- Step 2: Factor Reduction. Before a full-scale validation study, a multiple comparison experiment (e.g., a variant of the MUSHRA test) is used to identify critical experimental factors. This step determines which technical factors (e.g., different auralization methods) participants can subjectively differentiate. Factors that are not perceptibly different can be consolidated, reducing the number of variables for the final experiment [13].

- Step 3: Full-Matrix Validation. The core of the procedure is a series of controlled comparison experiments that directly contrast in-situ surveys with VR experiments. This step tests the independent and interactive effects of the key factors identified in Step 2 (e.g., auralization, visualization, HCI) on ecological validity. The results are used to calculate verisimilitude and veridicality descriptors, which can be integrated into an Ecological Validity Index (EVI) [13].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Technical Implementation

Successful implementation of a naturalistic VR paradigm requires careful consideration of hardware, software, and experimental design. The following toolkit outlines essential components and their functions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Naturalistic VR Neuroscience

| Category / Item | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Ecological Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Display Systems | ||

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Provides immersive stereoscopic visual stimulation. | Field of View, Resolution, Refresh Rate: Critical for visual fidelity and reducing simulator sickness [12]. |

| Eye Tracking Integration | Monitors gaze and exploratory behavior. | Essential for studying attention and cognitive load; enables foveated rendering [12]. |

| Auralization Systems | ||

| Ambisonics Audio | Creates spatially realistic 3D soundscapes. | Significantly enhances ecological validity over monoaural audio; crucial for spatial awareness [13]. |

| Synthesized Audio | Generates controlled auditory stimuli. | Allows for well-controlled experiments; can achieve high ecological validity when properly implemented [13]. |

| Interaction & Tracking | ||

| Motion Capture System | Tracks full-body posture and movement. | Enables naturalistic movement and kinematic analysis; required for virtual walking paradigms [12] [13]. |

| Force Feedback Devices | Provides haptic feedback for object interaction. | Improves task performance realism and sense of presence; mitigates limitations of visual-only interaction [12]. |

| Software & Analysis | ||

| VR Content-Authoring Tool | Enables creation and modification of virtual environments. | Flexibility to quickly alter environmental features (e.g., add/remove cues) is a key VR advantage [1] [12]. |

| Computational Models (DNNs) | To model neural information processing from brain responses. | An emerging approach to bridge brain data to human behavior under naturalistic stimulation [11]. |

Virtual Reality solidly occupies a unique and valuable niche as a middle ground in neuroscience research design, effectively balancing the competing demands of naturalism and experimental precision. The empirical evidence demonstrates that while VR simulations do not perfectly replicate reality, they can achieve a high degree of ecological validity, particularly for spatial navigation, cognitive assessment, and movement kinematics, when the appropriate technical factors are optimized [1] [12] [13]. The key to successful implementation lies in a rigorous, multi-step validation protocol that calibrates parameters, reduces factors, and quantitatively compares VR-based outcomes with real-world benchmarks [13]. Future developments in VR technology, such as improved haptic feedback, lower latency, and higher-resolution displays, will further enhance its fidelity. Moreover, the growing potential of deep learning models to interpret complex brain responses to naturalistic stimuli presents a promising avenue for future discovery [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing VR within a carefully validated framework offers a powerful means to generate more translatable and ecologically relevant findings on brain function and behavior.

Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) constitute two foundational psychological frameworks that explain how exposure to certain environments can enhance cognitive functioning and facilitate emotional recovery. Within virtual reality (VR) research, these theories provide the conceptual basis for designing interventions and assessing their ecological validity—the degree to which laboratory findings generalize to real-world settings [2]. ART, pioneered by Kaplan and Kaplan, posits that natural environments restore depleted cognitive resources through "soft fascination," allowing directed attention mechanisms to recover from fatigue [14] [15]. SRT, developed by Ulrich, emphasizes the rapid psycho-physiological response to non-threatening natural settings, triggering automatic reductions in stress arousal [16]. The integration of these theories into VR research creates a powerful paradigm for investigating human-environment interactions with unprecedented experimental control while maintaining relevance to real-world functioning.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Core Components of Attention Restoration Theory

ART proposes that restorative environments must embody four key components: being away, fascination, extent, and compatibility [15]. "Being away" refers to the psychological distance from routine mental contents and demands, which VR facilitates through immersive transportation to alternative settings. "Fascination" involves stimulus patterns that hold attention without effort, with "soft fascination" (such as watching clouds or flowing water) being particularly restorative as it allows for reflection [17]. "Extent" describes the coherence and scope of an environment that is rich enough to engage the mind, enabling a sense of exploration. "Compatibility" reflects the match between an individual's inclinations and what the environment affords [17]. Natural environments typically contain these properties, making them ideal for attention restoration. In VR, these components can be systematically manipulated and enhanced through interactive design elements.

Psycho-Physiological Mechanisms of Stress Recovery Theory

SRT operates through an evolutionary lens, suggesting that humans have a genetically predisposed capacity for rapid recovery from stress when exposed to unthreatening natural environments [16]. This process begins with an immediate, positive affective response to natural settings, which triggers a cascade of physiological changes including reduced heart rate, decreased blood pressure, and lower skin conductance levels [18] [19]. Neuroimaging studies reveal that exposure to nature activates brain regions associated with the parasympathetic nervous system, down-regulating the sympathetic arousal associated with stress [16]. The theory suggests that natural environments, unlike urban settings, contain cues that signal safety and resources, thereby reducing the need for heightened vigilance and enabling recovery processes [20].

Complementary Theoretical Perspectives

While ART and SRT originate from different paradigms—cognitive versus psycho-physiological—they offer complementary explanations for nature's benefits:

Table: Comparative Analysis of ART and SRT

| Aspect | Attention Restoration Theory (ART) | Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Recovery from directed attention fatigue (cognitive) | Recovery from psycho-physiological stress and negative affect (emotional) |

| Core Mechanism | "Soft fascination" that engages involuntary attention, allowing directed attention to rest | Immediate, automatic positive emotional response to non-threatening nature, triggering physiological calming |

| State Being Addressed | Mental fatigue from prolonged cognitive effort | Excessive arousal (e.g., anxiety, fear, tension) |

| Temporal Dynamics | Gradual restoration over longer exposure | Rapid recovery occurring within minutes |

| Key Physiological Correlates | EEG changes (frontal theta, parietal P3b) [15] | Heart rate, blood pressure, cortisol, skin conductance [21] [18] |

| VR Application Example | Closed-loop environments that adjust based on EEG metrics of attention [15] | Virtual natural environments for stress reduction in clinical populations [21] |

Assessing Ecological Validity in VR Paradigms

Defining and Measuring Ecological Validity

Ecological validity in VR research refers to "the extent to which laboratory data reflect real-world perceptions" and encompasses two primary approaches: verisimilitude and veridicality [2]. Verisimilitude concerns the similarity between experimental task demands and those encountered in everyday life, while veridicality examines the empirical relationship between laboratory measures and real-world functioning [2]. Recent studies have adopted multi-method approaches to assess ecological validity, comparing in-situ, room-scale VR, and head-mounted display (HMD) conditions across perceptual, psychological, and physiological domains.

Empirical Evidence for Ecological Validity

A comprehensive study examining ecological validity found that both cylindrical room-scale VR and HMD setups demonstrated ecological validity regarding audio-visual perceptive parameters, though HMDs were perceived as more immersive [2]. For psychological restoration metrics, neither VR tool perfectly replicated in-situ experiments, with cylindrical VR showing slightly better accuracy than HMDs [2]. Physiological measures revealed that both VR types showed potential for representing real-world conditions in terms of EEG change metrics and asymmetry features, though HMDs were not valid substitutes for real-world settings concerning EEG time-domain features [2].

Table: Ecological Validity of VR Measures Across Response Domains

| Response Domain | VR Type | Ecological Validity Assessment | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptual | Room-scale (Cylinder) | High validity | No significant difference in audio quality, video quality, and realism compared to in-situ [2] |

| Perceptual | HMD | High validity | Higher immersion ratings than room-scale VR; valid for audio-visual parameters [2] |

| Psychological Restoration | Room-scale (Cylinder) | Moderate validity | Slightly more accurate than HMD for restoration metrics but still imperfect [2] |

| Psychological Restoration | HMD | Moderate validity | Cannot perfectly replicate in-situ restoration experiences [2] |

| Physiological (EEG) | Room-scale (Cylinder) | High for some metrics | Accurate for EEG time-domain features; promising for change metrics and asymmetry [2] |

| Physiological (EEG) | HMD | Limited for some metrics | Not valid for EEG time-domain features; promising for change metrics and asymmetry [2] |

| Physiological (HR/SCL) | Both | Variable | HR decreased significantly in VR stress-reduction interventions [21]; SCL responses mixed |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized VR Restoration Protocols

Stress Induction and Recovery Protocol (adapted from multiple studies [21] [18] [19]):

- Baseline Assessment (10-15 minutes): Collect pre-intervention measures including psychological surveys (STAI-S, PSS-10) and physiological baselines (HR, HRV, EEG, SCL, salivary cortisol).

- Stress Induction (5-10 minutes): Implement standardized stressor tasks such as the Trier Social Stress Test for Groups (TSST-G) or cognitively demanding activities (e.g., timed arithmetic, Stroop tasks).

- Post-Stress Assessment (5 minutes): Re-measure psychological and physiological states to confirm stress induction.

- VR Intervention (10-30 minutes): Participants engage with the virtual environment according to experimental condition.

- Post-Intervention Assessment (10 minutes): Collect the same measures as baseline to quantify change.

- Follow-up (optional): Some protocols include delayed measures to assess duration of effects.

Closed-Loop ART Protocol [15]:

- EEG Baseline (3 minutes): Participants sit quietly with eyes closed to establish neural baseline.

- VR Exposure with Neurofeedback (30 minutes): Participants experience virtual nature environments while EEG vigilance levels are monitored in real-time.

- Dynamic Environment Adjustment: Virtual environments automatically modify elements (e.g., fog dissipation, visual complexity) based on EEG metrics of attentional engagement.

- Pre-Post Behavioral Tasks: Perceptual discrimination tasks administered before and after VR exposure to quantify attentional improvements.

VR Technical Specifications and Equipment

Table: Research-Grade VR Equipment for Restoration Studies

| Equipment Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Display Systems | CAVE systems, HTC Vive, Meta Quest 2, Samsung Gear | Presentation of restorative environments | CAVE offers multi-user capability; HMDs provide higher immersion [2] [15] |

| Physiological Monitoring | Polar H10 HR monitor, NeuLog GSR sensor, research-grade EEG (e.g., 64-channel systems), eye-tracking systems | Objective measurement of restorative outcomes | Consumer-grade sensors increase accessibility but may reduce accuracy [2] [21] |

| Software Platforms | Unity, Unreal Engine, specialized VR therapy platforms | Creation and delivery of virtual environments | Customizability vs. standardization trade-offs |

| Stress Induction | TSST-G materials, cognitive task batteries | Standardized stress induction | Must be ethically appropriate for participant population |

Quantitative Findings and Empirical Support

Efficacy of VR-Based Restoration Interventions

Multiple studies demonstrate the effectiveness of VR environments for restoration, with varying effect sizes across different outcome measures and population types:

Table: Quantitative Outcomes of VR Restoration Interventions

| Study Reference | VR Environment | Population | Key Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lu & Lau (2025) [2] | Natural audio-visual (Cylinder VR vs. HMD) | General adults | Perceptual, psychological, EEG, HR | Both VR types ecologically valid for perceptual measures; mixed results for psychological restoration |

| Cardiology VR Pilot (2025) [21] | Geometric visual with binaural audio | CVD patients | STAI-S, HR, BP, GSR, HRV | Significant STAI-S reduction (median 31 to 24, p<.001); HR decreased (73 to 67 bpm, p<.001) |

| Gao et al. (2025) [18] | Spatial openness variations | General adults | STAI, EEG (α/β, θ/β), SCL, eye-tracking | Open spaces significantly reduced stress, increased α/β and θ/β ratios, decreased pupil diameter |

| Adolescent VR Study [19] | Green/blue space, urban, classroom | Adolescents (10-19) | HR, SCL, RMSSD, LF/HF, PANAS | Virtual natural environments showed most pronounced effects on stress recovery and positive affect |

| Closed-Loop ART [15] | Nature environments with EEG feedback | University students | EEG (frontal theta ITC, P3b), response time | Improved attentional engagement with positive EEG changes in treatment group |

Neural Correlates of Restoration in Virtual Environments

Neuroimaging studies provide compelling evidence for the neural mechanisms underlying restoration in VR environments:

Table: Neural Correlates of Restoration in Response to Virtual Environments

| Neural Measure | Experimental Condition | Key Findings | Theoretical Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Frontal Theta Inter-trial Coherence [15] | Closed-loop ART vs. standard ART | Increased in treatment group, correlated with attentional improvement | ART: Directed attention restoration |

| EEG α/β and θ/β Ratios [18] | Open vs. closed virtual spaces | Significantly higher in open spaces, particularly in occipital and left frontal lobes | SRT: Physiological relaxation |

| DMN Functional Connectivity [20] | Nature image viewing vs. urban image viewing | Enhanced connectivity between medial DMN and attention/executive regions | ART: Being away and reflection |

| Parietal P3b Event-Related Potential [15] | Post-VR attention tasks | Increased amplitude after closed-loop ART intervention | ART: Attentional resource allocation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Materials for VR Restoration Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Psychological Scales | STAI-S, Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS), Restorative Outcome Scale (ROS), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) | Quantify subjective restoration experiences | Ensure cross-cultural validation; adapt for specific populations |

| Physiological Monitoring Systems | EEG systems, Polar H10 HR monitor, Shimmer GSR, Salivary cortisol kits | Objective measurement of restorative outcomes | Standardize placement, timing, and preprocessing pipelines |

| VR Hardware Platforms | CAVE systems, HTC Vive, Meta Quest, eye-tracking integration | Presentation of restorative environments | Balance ecological validity with experimental control |

| Stress Induction Protocols | Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), cognitive depletion tasks (e.g., directed attention fatigue tasks) | Standardized pre-intervention state | Ethical considerations; appropriate for population |

| Data Analysis Tools | EEGLAB, HRV analysis tools, statistical packages (R, Python with specialized libraries) | Quantification and interpretation of outcomes | Pre-register analysis plans; account for multiple comparisons |

Future Directions and Methodological Considerations

The integration of ART and SRT within VR research paradigms continues to evolve, with several promising directions emerging. First, closed-loop systems that dynamically adjust virtual environments based on real-time physiological feedback represent a frontier in personalized restoration interventions [15]. Second, research must address individual differences in responsiveness to virtual restoration, potentially identifying participant characteristics that predict intervention efficacy. Third, standardization of measures across studies would enhance comparability and enable meta-analytic approaches. Fourth, longitudinal investigations are needed to examine whether repeated VR restoration sessions produce cumulative benefits. Finally, research should explore hybrid approaches that combine ART and SRT principles to simultaneously target cognitive and emotional restoration pathways.

Methodologically, researchers must continue to address the limitations of current VR approaches, including potential measurement inaccuracies with consumer-grade sensors [2], limited diversity in experimental sites and participants, and the challenge of creating virtual environments that fully capture the multi-sensory richness of real-world natural settings. Nevertheless, the existing evidence strongly supports the ecological validity of well-designed VR paradigms for investigating restoration theories, offering powerful tools for advancing our understanding of human-environment interactions across research and clinical applications.

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in neuroscience, not merely for its immersive capabilities but for its unique alignment with the brain's fundamental operational principles. The theoretical foundation for this alignment is embodied cognition, a materially-grounded theory proposing that the human mind is predominantly determined by the form of the human body [22]. This framework suggests that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body's interactions with the world. According to this perspective, to regulate and control the body effectively, the brain continuously creates embodied simulations—internal models of the body in its environment that are used to represent and predict actions, concepts, and emotions [23]. These simulations form the core of how the brain understands and navigates the real world.

VR operates on a remarkably similar principle. A VR system maintains a model—a simulation—of the body and the space around it, predicting the sensory consequences of a user's movements and providing corresponding sensory feedback [23]. This parallel suggests that VR functions as an externalized embodied technology, capable of interfacing directly with the brain's innate simulation mechanisms. This connection provides a powerful neurophysiological basis for using VR to study, and potentially alter, human experience. This is particularly relevant within naturalistic neuroscience paradigms, where VR is considered a middle ground, offering a compelling balance between ecological validity and experimental control [1]. It allows researchers to present dynamic, multimodal stimuli in controlled yet contextually rich environments, thereby addressing a critical tension in neuroscience research between laboratory control and real-world applicability [24].

Neurophysiological Evidence: Brain Activity in Virtual Environments

The claim that VR leverages the brain's inherent simulation mechanisms is supported by growing empirical evidence from neurophysiological studies. Quantitative Electroencephalography (QEEG) analyses during immersive tasks reveal specific and significant alterations in brain network activity.

Fronto-Parietal Network Activation

Studies employing immersive role-playing games have demonstrated the activation of fronto-parietal networks associated with executive functioning and goal-directed behavior. Independent Component Analysis of QEEG data has shown that this activation significantly differs from baseline resting states, particularly in the theta (4-8 Hz) and high alpha (8-14 Hz) frequency bands [22]. These frequency bands are critical for the formation of functional long-range coherence between different brain regions, suggesting that VR tasks engage large-scale, integrated neural systems rather than isolated cortical areas.

A principal function of the superior parietal lobe is to represent the position of the body in physical space. The consistent involvement of a fronto-parietal network during immersive VR tasks implies that the brain is engaging its natural, embodied cognition-type mechanisms to interact with the virtual environment [22]. This finding supports the revolutionary idea that cognitive processes related to body representation can be "transferred" to a digital avatar, creating a fundamentally different cognitive environment for the brain.

Neural Signatures of Attention and Distraction

Research using VR-based Continuous Performance Tests (VR-CPT) in virtual classrooms provides deeper insights into how virtual environments modulate cognitive processes like sustained attention. Investigations into the impact of visual distractors combine behavioral measures with electrophysiological markers, such as event-related potentials (ERPs), and nonlinear dynamics, like signal entropy.

Table 1: Neurophysiological and Behavioral Changes Under Visual Distraction in VR

| Measurement Domain | Specific Metric | Change without Distractors (N-D) | Change with Distractors (Y-D) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Performance | Commission Errors | Lower | Significantly Increased (p<0.001) | Increased impulsivity |

| Omission Errors | Lower | Significantly Increased (p<0.001) | Decreased vigilance | |

| Multipress Errors | Lower | Significantly Increased (p<0.001) | Reduced response inhibition | |

| ERP (P300) | Latency | Shorter | Prolonged (esp. at CPz, Pz, Oz) | Slower cognitive processing & stimulus evaluation |

| Amplitude | Lower | Increased (at Fz, FCz, Oz) | Greater attentional resource allocation | |

| EEG Nonlinear Dynamics | Sample Entropy (SampEn) | Lower | Significantly Higher (frontal, central, parietal) | Increased neural complexity & cognitive load |

| Fuzzy Entropy (FuzzyEn) | Lower | Significantly Higher (frontal, central, parietal) | Increased system unpredictability |

The findings from this study [25] demonstrate that visual distractors in an ecologically valid VR setting disrupt cognitive processes related to visual information integration, attentional control, and decision-making. The concomitant decrease in behavioral performance and increase in neural complexity, as measured by entropy, indicates a state of elevated cognitive workload as the brain attempts to manage multiple streams of information.

Experimental Protocols for VR-Based Neuroscience

To systematically investigate the neurophysiological correlates of embodied cognition in VR, researchers have developed robust experimental protocols. The following workflow visualizes a typical structure for such an experiment, integrating behavioral, subjective, and neurophysiological measures.

Protocol 1: VR Continuous Performance Test with EEG

This protocol is designed to study sustained attention under ecologically valid conditions [25].

- Objective: To investigate the effects of visual distractors in a VR environment on behavioral performance and neural correlates of sustained attention.

- Participants: Typically 50+ neurotypical adults, screened for ADHD symptoms and neurological conditions.

- VR Environment: A virtual classroom is rendered using a head-mounted display (HMD) like the HTC VIVE.

- Task: A Go/No-go Continuous Performance Test (CPT). Participants must respond quickly to target stimuli ("Go") and inhibit responses to non-targets ("No-go").

- Experimental Conditions:

- No-Distractor (N-D): The virtual classroom is devoid of distracting events.

- With Visual Distractors (Y-D): Ecologically valid distractors are introduced (e.g., a classmate walking in, objects falling).

- Data Collection:

- Behavioral: Commission errors (responding to No-go), omission errors (not responding to Go), multipress errors, and reaction time.

- Electrophysiological: 32-channel EEG is recorded continuously. Data is analyzed for:

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): P300 component (amplitude and latency).

- Nonlinear Dynamics: Sample entropy (SampEn) and fuzzy entropy (FuzzyEn) of the EEG signal.

- Analysis: Comparison of behavioral and EEG metrics between N-D and Y-D conditions using paired statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA).

Protocol 2: QEEG During Immersive Gameplay

This protocol explores the transfer of bodily consciousness to a virtual avatar [22].

- Objective: To identify changes in brain network activation during an immersive gaming task that suggests embodied cognition.

- Participants: Adult players engaged in immersive role-playing games (e.g., The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim).

- Task: Free exploration and goal-directed activity within the open-world game.

- Data Collection: Quantitative Electroencephalography (QEEG) is recorded during both a baseline resting state and gameplay.

- Analysis: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is used to identify activated brain networks. Statistical comparisons of spectral power in theta (4-8 Hz) and high alpha (8-14 Hz) bands are made between baseline and gameplay, focusing on fronto-parietal networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Conducting rigorous neurophysiological research in VR requires a suite of specialized tools and technologies. The table below details key components of a VR neuroscience laboratory.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for VR Neuroscience

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware | HTC VIVE, Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs), Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) | Presents immersive, 3D visual stimuli. HMDs offer accessibility, while room-scale systems like CAVEs may provide higher ecological validity for group interactions [2]. |

| Neuroimaging Equipment | 32-channel EEG system (e.g., NeuroScan), amplifier (e.g., NuAmps) | Records millisecond-level brain activity non-invasively. Critical for capturing ERPs like P300 and for entropy analysis [25]. |

| Computing & Graphics | High-performance PC (NVIDIA GTX 2080Ti+, i7 CPU) | Renders complex, high-fidelity virtual environments in real-time without latency, preserving the closed-loop experience and user presence [25]. |

| Experimental Paradigms | Virtual Reality Continuous Performance Test (VR-CPT), Virtual Morris Water Maze (VMWM) | Provides standardized, replicable tasks with high verisimilitude. VR-CPT assesses attention; VMWM assesses spatial navigation [24] [25]. |

| Software & Analysis Tools | G*Power (for sample size calculation), EEG analysis toolbox (e.g., for ICA, entropy calculation) | Ensures statistical robustness and enables processing of complex neurophysiological signals, including time-frequency and nonlinear analyses [25] [26]. |

Ecological Validity: Bridging the Lab and the Real World

A central promise of VR in neuroscience is its ability to enhance ecological validity—the extent to which laboratory findings generalize to real-world scenarios [2]. This is evaluated through two main approaches:

- Verisimilitude: The similarity between the task demands of the test and the demands imposed in everyday life. VR environments excel here by simulating complex, dynamic scenarios that require multimodal processing and active engagement, moving beyond simple, static laboratory stimuli [24].

- Veridicality: The degree to which performance in the laboratory test is empirically related to measures of real-world functioning. Research shows that VR-based assessments, such as the VR-CPT, have enhanced diagnostic precision in distinguishing clinical populations (e.g., ADHD) compared to traditional tests, suggesting stronger veridicality [25].

Comparative studies have demonstrated that both HMDs and room-scale VR setups can be ecologically valid for audio-visual perceptual parameters and show promise for physiological measures like EEG [2]. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the level of immersion and the design of the VR system can influence outcomes. For instance, conflicts between vestibular and visual information in head-fixed setups can lead to altered neural coding in spatial navigation circuits, such as place cells in the hippocampus [1]. This underscores the importance of matching the VR setup to the specific research question to maximize ecological validity while maintaining the experimental control that makes VR such a powerful tool for naturalistic neuroscience.

The pursuit of ecological validity—the extent to which laboratory findings generalize to real-world conditions—represents a fundamental challenge in neuroscience research [24]. For decades, researchers have navigated a essential tension between experimental control and the ability to recreate the complex, dynamic nature of real-world environments [24]. The Spectrum Approach to environmental naturalism provides a methodological framework for addressing this challenge by systematically categorizing and manipulating the degree of naturalism in experimental settings, particularly through virtual reality (VR) technologies.

Virtual reality has emerged as a powerful tool for bridging this gap, offering the potential to present digitally recreated real-world activities to participants while maintaining laboratory control [24]. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundations, methodological considerations, and practical applications of the Spectrum Approach within naturalistic neuroscience paradigms, with specific relevance to drug development research.

Theoretical Framework: Defining the Spectrum of Environmental Naturalism

The Ecological Validity Construct

Ecological validity in psychological assessment encompasses two distinct requirements: veridicality, where performance on a measure predicts real-world functioning, and verisimilitude, where testing conditions resemble activities of daily living [24]. Originally introduced by Orne (1962), ecological validity describes the extent to which experimental findings can be generalized to settings outside the laboratory [2].

The concept originated in psychology, with Neisser (1978) contending that cognitive psychology experiments conducted in artificial settings with measures bearing little resemblance to everyday life lack ecological validity and fail to generalize beyond constrained laboratory settings [24].

The Naturalism Spectrum

The Spectrum Approach conceptualizes environmental naturalism across a continuum ranging from highly controlled laboratory tasks to fully naturalistic real-world settings:

| Level of Naturalism | Description | Typical Paradigms | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Naturalism | Highly controlled, abstract laboratory tasks | Wisconsin Card Sort Test, Stroop Task, N-back tasks | Static stimuli, minimal context, response limitations [24] [27] |

| Moderate Naturalism | Simplified real-world scenarios with some contextual elements | Video-game like tasks, cartoon viewing with time monitoring | Some contextual embedding, limited interaction, constant pacing [28] [29] |

| High Naturalism | Complex, dynamic environments allowing free exploration | Virtual reality tasks like EPELI, real-world simulations | Stimulus-rich environments, free-paced activities, varied behavioral responses [27] |

| Full Naturalism | Actual real-world settings with minimal experimental control | In-situ observations, naturalistic observation | Complete contextual embedding, unrestricted behavior, authentic consequences |

Table 1: The Spectrum of Environmental Naturalism in Experimental Paradigms

Virtual Reality as a Bridge Across the Spectrum

VR Technologies for Naturalistic Neuroscience

Virtual reality technologies offer the unique capability to position experimental paradigms at various points along the naturalism spectrum. Recent advances provide enhanced computational capacities for administration efficiency, stimulus presentation, automated logging of responses, and data analytic processing [24]. Different VR implementations offer varying degrees of immersion and ecological validity:

| VR Technology | Immersion Level | Ecological Validity Findings | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | High | Perceived as more immersive; valid for audio-visual perceptive parameters but not perfect for psychological restoration [2] | Individual assessment, highly immersive scenarios |

| Cylinder Room-Scaled VR | Moderate | Slightly more accurate than HMD for psychological restoration metrics; more accurate for EEG time-domain features [2] | Small group assessments, controlled naturalism |

| CAVE Systems | High | Enables multi-participant interaction with virtual environments; underexplored ecological validity [2] | Social interaction studies, complex environmental exposure |

| Desktop VR | Low | Limited immersion but maintains experimental control; lower ecological validity [24] | Initial testing, populations prone to VR sickness |

Table 2: Virtual Reality Technologies and Their Position on the Naturalism Spectrum

Physiological Correlates of Naturalistic Experience

The ecological validity of VR experiments has been examined through multiple physiological measures that may respond differently across the naturalism spectrum:

| Physiological Measure | Response to VR Naturalism | Ecological Validity Findings | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Metrics | Varies by VR technology | Both HMD and cylindrical VR show potential for real-world conditions in change metrics and asymmetry features; cylindrical VR more accurate for time-domain features [2] | Critical for affective and cognitive neuroscience |

| Heart Rate (HR) | Sensitive to environmental exposure | HR change rate (percentage difference from stressor period) shows promise as ecological validity metric [2] | Stress recovery and arousal research |

| Electrodermal Activity (EDA) | Modulated by cognitive activities | Used to assess presence; also affected by movement, humidity, and temperature [28] | Arousal and emotional response studies |

| Eye Tracking | Integrated into VR headsets | Studies gaze control, eye-hand coordination in naturalistic contexts [28] | Visual attention and information processing |

Table 3: Physiological Measures for Assessing Ecological Validity Across the Naturalism Spectrum

Methodological Implementation: The EPELI Case Study

Experimental Protocol for High-Naturalism Assessment

The Executive Performance in Everyday Living (EPELI) VR task represents a high-naturalism approach specifically designed to address ecological validity challenges in clinical populations [27]. This protocol exemplifies the implementation of the Spectrum Approach in naturalistic neuroscience research:

Population and Sampling:

- Recruit 71 children with ADHD and 71 typically developing peers aged 9-13 years

- Exclude participants based on standard neurodevelopmental criteria

- Ensure unmedicated status during testing for ADHD group

VR Environment Setup:

- Implement a stimulus-rich virtual apartment resembling a typical home

- Enable free exploration and interaction with objects at participant's own pace

- Develop 13 different scenarios representing everyday activities (e.g., morning routines, evening preparations)

Task Administration:

- Present auditory instructions for a set of tasks to complete at beginning of each scenario

- Incorporate Time-Based Prospective Memory (TBPM) tasks requiring execution after specific time intervals

- Enable spontaneous clock-checking behavior without external prompts

Data Collection:

- Record absolute frequency of clock checks (resource allocation)

- Calculate strategic time monitoring (relative clock-checking: ratio of checks in last interval to total checks)

- Measure TBPM performance (successful execution of intended tasks at appropriate times)

- Log additional behavioral metrics (navigation paths, interaction sequences, errors)

Key Research Findings from Naturalistic Assessment

Implementation of the EPELI protocol revealed critical insights that would be difficult to obtain through low-naturalism paradigms:

- Children with ADHD showed lower TBPM performance not because of reduced overall clock-checking frequency, but due to less strategic time monitoring [27]

- Strategic time monitoring accounted for 22.1% of variance in TBPM performance and fully mediated the effect of ADHD [27]

- The combination of absolute clock-checking frequency, strategic time monitoring, and ADHD status explained 53.9% of variance in TBPM performance [27]

- These findings highlight the value of high-naturalism assessment for identifying specific mechanistic deficits rather than generalized performance impairments

The Researcher's Toolkit: Implementing the Spectrum Approach

Research Reagent Solutions for Naturalistic Paradigms

Successful implementation of the Spectrum Approach requires specific technical resources and methodological components:

| Research Reagent | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| EPELI VR Environment | Quantifies goal-directed behavior in naturalistic but controlled settings | Stimulus-rich virtual apartment with 13 scenarios, object interaction, free navigation [27] |

| Consumer-Grade EEG Sensors | Measures electrical brain activity across naturalism conditions | Portable systems with 4-frequency band analysis (theta: 4-8Hz, alpha: 8-14Hz, beta: 14-30Hz) [2] |

| Heart Rate Variability Monitors | Captures cardiovascular responses to environmental stimuli | Wearable sensors calculating HR change rate from stressor baselines [2] |

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) Systems | Provides immersive VR experience with head-tracking | High-resolution displays with integrated eye-tracking capabilities [2] [28] |

| Room-Scale VR Systems | Enables multi-participant naturalistic assessment | Cylindrical or CAVE environments with projection surfaces on walls, floors, and ceilings [2] |

| Strategic Time Monitoring Algorithm | Quantifies temporal distribution of clock-checking behavior | Calculates ratio of clock checks in final interval to total checks before target time [27] |

Table 4: Essential Research Components for Implementing the Spectrum Approach

Experimental Workflow for Spectrum Approach Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for applying the Spectrum Approach in naturalistic neuroscience research:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for spectrum approach

Relationship Between Ecological Validity Concepts

This conceptual diagram illustrates the key components and their relationships in assessing ecological validity within the Spectrum Approach:

Diagram 2: Ecological validity assessment framework

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Neuroscience

Enhancing Clinical Trial Methodology

The Spectrum Approach offers significant promise for improving measurement sensitivity in clinical trials for neurological and psychiatric disorders:

- Endpoint Development: High-naturalism VR tasks can provide more sensitive endpoints for detecting treatment effects on real-world functioning