EEG-fNIRS Data Fusion: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

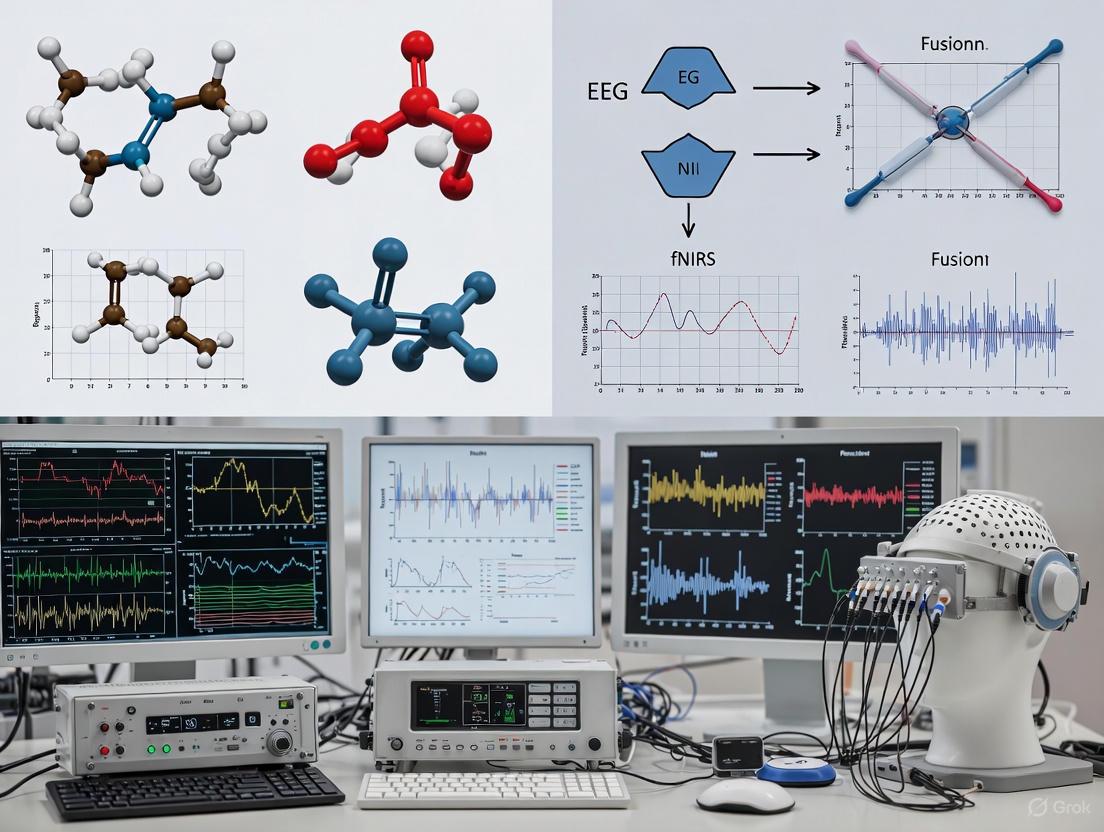

This comprehensive review explores data fusion techniques for integrating electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) signals to advance biomedical research and clinical applications.

EEG-fNIRS Data Fusion: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores data fusion techniques for integrating electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) signals to advance biomedical research and clinical applications. It covers the fundamental principles of these complementary neuroimaging modalities, detailed methodological approaches for multimodal fusion, practical strategies for optimizing data quality, and rigorous validation frameworks. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article highlights how EEG-fNIRS fusion overcomes individual modality limitations by combining millisecond temporal resolution with improved spatial localization. Through clinical case studies and emerging research applications, we demonstrate how this integrated approach provides richer insights into brain function, enhances diagnostic capabilities, and accelerates therapeutic development for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Understanding EEG and fNIRS: Complementary Neuroimaging Modalities

The human brain operates through two primary, interconnected physiological processes: rapid electrical activity from neuronal firing and slower hemodynamic responses that deliver energy resources. Electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) have emerged as complementary neuroimaging techniques that capture these distinct phenomena directly related to neural function [1]. EEG measures the electrical potentials generated by synchronized pyramidal neuron activity, offering millisecond-level temporal resolution to track immediate brain dynamics [1]. In contrast, fNIRS detects hemodynamic changes by measuring concentration changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the blood, providing better spatial localization of active brain regions [2] [3]. Their integration creates a powerful multimodal approach for studying brain function, leveraging the neurovascular coupling mechanism that links neuronal electrical activity to subsequent vascular responses [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of EEG and fNIRS Neuroimaging Modalities

| Characteristic | EEG (Electrical Activity) | fNIRS (Hemodynamic Response) |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Parameter | Electrical potentials from synchronized post-synaptic activity | Concentration changes of HbO and HbR |

| Physiological Basis | Direct neuronal electrical activity | Neurovascular coupling |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond level (∼5 ms) [4] | Slower (∼0.1-1 Hz) [2] [1] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (several centimeters) [5] [1] | Moderate (∼1-3 cm) [4] [5] |

| Penetration Depth | Superficial and deep sources (with volume conduction) | Cortical surface (1-3 cm) [2] |

| Primary Signal Origin | Pyramidal neurons in cortical layers [1] | Cerebral microvasculature (arterioles, capillaries, venules) |

| Noise Sensitivity | Sensitive to electromagnetic artifacts [6] | Sensitive to systemic physiological noise [7] |

Physiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The Electrophysiological Basis of EEG Signals

Electroencephalography captures the macroscopic temporal dynamics of brain electrical activity through passive measurements of scalp voltages [2]. The recorded EEG signal primarily results from the summation of synchronized post-synaptic potentials in cortical pyramidal neurons [1]. For detectable EEG signals to occur, tens of thousands of pyramidal neurons within a cortical column must fire synchronously, with their dendritic trunks coherently oriented parallel to each other and perpendicular to the cortical surface [1]. This specific anatomical arrangement enables sufficient summation and propagation of electrical signals to the scalp surface where electrodes detect voltage fluctuations [1]. These neural oscillations are categorized into characteristic frequency bands—theta (4-7 Hz), alpha (8-14 Hz), beta (15-25 Hz), and gamma (>25 Hz)—each associated with different brain states and cognitive functions [1].

The Hemodynamic Basis of fNIRS Signals

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy leverages the relative transparency of biological tissues to light in the near-infrared spectrum (650-950 nm) to measure hemodynamic changes associated with neural activity [2] [3]. Within this wavelength range, light penetrates the scalp and skull, reaching the cortical surface where it is predominantly absorbed by the chromophores oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) [3]. The neurovascular coupling mechanism forms the foundation for fNIRS: when neurons become active, they trigger a complex cascade that increases local cerebral blood flow, delivering oxygen and nutrients to support metabolic demands [1] [3]. This hemodynamic response manifests as an initial, brief increase in deoxyhemoglobin concentration (the "initial dip") followed by a more pronounced increase in oxyhemoglobin and a decrease in deoxyhemoglobin concentration [3]. fNIRS systems typically utilize two or more wavelengths to distinguish between HbO and HbR based on their distinct absorption spectra [2].

Neurovascular Coupling: Connecting Electrical and Hemodynamic Domains

Neurovascular coupling represents the critical physiological link between neuronal electrical activity and the hemodynamic responses measured by fNIRS [1]. When neurons fire, they consume energy, triggering a complex signaling cascade that involves astrocytes, neurons, and vascular cells [3]. This process begins with increased oxygen extraction from local blood vessels, creating a transient rise in deoxyhemoglobin [3]. Almost simultaneously, vasoactive signals cause arteriolar dilation, increasing local cerebral blood flow and delivering oxygenated blood that typically overshoots metabolic demands [3]. The resulting hemodynamic response peaks 4-6 seconds after neural activation, creating the characteristic fNIRS signal patterns [8]. This tightly regulated mechanism forms the theoretical basis for integrating EEG and fNIRS, as it connects the direct electrical measurements of EEG with the indirect metabolic-hemodynamic measurements of fNIRS [1].

Figure 1: Signaling Pathway Linking Neural Activity to Measurable Signals. The diagram illustrates how initial neural electrical activity triggers neurovascular coupling, leading to measurable EEG and fNIRS signals through different physiological pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS Recording

Hardware Integration and Setup

Successful simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording requires careful hardware integration to ensure signal quality and synchronization. Two primary approaches exist for system integration: (1) separate systems synchronized via computer, and (2) unified systems with a single processor for both modalities [5]. While the first approach offers simplicity, the second provides more precise synchronization essential for capturing the temporal relationship between electrical and hemodynamic responses [5]. For helmet design, researchers typically use flexible EEG electrode caps as a foundation, creating punctures at specific locations to accommodate fNIRS probe fixtures [5]. Customized helmets using 3D printing or cryogenic thermoplastic sheets offer better fit and more consistent optode placement across subjects [5]. The integration must maintain proper source-detector distances (typically 2.5-3.5 cm for adults) for fNIRS while ensuring good electrode-scalp contact for EEG [2] [3]. Optodes and electrodes should be co-registered to anatomical landmarks (nasion, inion, preauricular points) using a 3D digitizer for accurate spatial localization [9].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS System Components | Continuous-wave NIRS system (e.g., Hitachi ETG-4100), optical fibers, laser diodes/LEDs (695 & 830 nm) [9] | Generate and detect NIR light to measure HbO/HbR concentration changes |

| EEG System Components | EEG amplifier system (e.g., BrainAMP), Ag/AgCl electrodes, electrolyte gel [5] | Measure electrical potentials from scalp surface |

| Integration Materials | Custom integration caps, 3D-printed helmet fixtures, thermoplastic sheets [5] | Co-register EEG and fNIRS components with consistent geometry |

| Auxiliary Equipment | 3D magnetic space digitizer (e.g., Polhemus Fastrak), response recording devices [9] | Record spatial coordinates of optodes/electrodes; capture behavioral data |

| Software Tools | MNE-Python, NIRS processing toolboxes, custom analysis scripts [8] | Preprocess, synchronize, and analyze multimodal data |

Protocol for Motor Execution, Observation, and Imagery Paradigm

The motor execution, observation, and imagery paradigm provides an excellent experimental framework for studying the action observation network (AON) and comparing electrical and hemodynamic responses across different motor conditions [9]. This protocol employs a block design with three conditions: (1) Motor Execution (ME): participants physically perform a motor task (e.g., grasping and moving a cup) in response to an "your turn" auditory cue; (2) Motor Observation (MO): participants observe an experimenter performing the same motor task following a "my turn" cue; and (3) Motor Imagery (MI): participants mentally simulate the motor task without physical movement [9]. Each trial begins with a 2-second instruction period, followed by a 5-second task period, and a variable inter-trial interval (10-20 seconds) to allow hemodynamic responses to return to baseline [9]. For simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording, participants should be seated comfortably facing an experimenter, with the fNIRS optodes placed over sensorimotor and parietal cortices and EEG electrodes arranged according to the international 10-20 system [9].

Figure 2: Experimental Protocol for Motor Paradigm. The workflow outlines the procedure for simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording during motor execution, observation, and imagery tasks.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Preprocessing simultaneous EEG-fNIRS data requires modality-specific pipelines executed in parallel before multimodal fusion. For fNIRS data, begin by converting raw intensity signals to optical density, then to hemoglobin concentration changes using the modified Beer-Lambert law [8]. Apply bandpass filtering (0.01-0.5 Hz) to remove cardiac pulsation (∼1 Hz) and slow drifts while preserving the hemodynamic response [8]. For EEG data, implement high-pass filtering (0.5 Hz) to remove slow drifts, notch filtering (50/60 Hz) to remove line noise, and artifact removal techniques (e.g., ICA) to eliminate ocular and muscle artifacts [1]. Quality control metrics should include the scalp coupling index (SCI) for fNIRS (recommended threshold >0.5) and signal-to-noise ratio for EEG [8]. Epoch data according to experimental conditions, with appropriate baseline correction (typically -5 to 0 seconds before stimulus onset) and artifact rejection [8]. Finally, synchronize the preprocessed EEG and fNIRS data streams using recorded trigger pulses or shared clock signals [5].

Data Fusion Methodologies and Applications

Fusion Approaches for EEG-fNIRS Integration

Multimodal fusion of EEG and fNIRS data occurs at three primary levels: decision-level, feature-level, and data-level fusion [1]. Decision-level fusion involves processing and classifying each modality separately, then combining the results at the decision stage using methods like majority voting or meta-classifiers [4]. This approach demonstrated a 5-7% improvement in classification accuracy for motor imagery tasks compared to single-modality approaches [4]. Feature-level fusion combines extracted features from both modalities before classification, often employing techniques like canonical correlation analysis (CCA) or structured sparse multiset CCA (ssmCCA) to identify relationships between electrical and hemodynamic features [9] [4]. This method has shown particular promise in identifying shared neural regions associated with the action observation network during motor tasks [9]. Data-level fusion integrates raw or minimally processed data from both modalities, often using joint blind source separation or model-based approaches to identify common underlying components [7].

Applications in Clinical Neuroscience and Brain-Computer Interfaces

The complementary nature of EEG and fNIRS has enabled advanced applications across clinical and research domains. In clinical neuroscience, simultaneous EEG-fNIRS has been applied to study neurological and psychiatric disorders including epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, stroke, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [4] [5]. For epilepsy monitoring, EEG provides precise temporal localization of epileptiform activity while fNIRS offers improved spatial localization of the epileptic focus [3]. In brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), hybrid EEG-fNIRS systems have significantly improved classification accuracy for motor imagery tasks compared to unimodal systems [4] [6]. Recent advances include deep learning approaches with cross-modal attention mechanisms (e.g., MBC-ATT framework) that dynamically weight the contribution of each modality based on task demands, further enhancing classification performance for cognitive state decoding [6].

The fundamental differences between electrical activity and hemodynamic responses, rather than presenting a challenge, create a powerful complementary relationship when captured through simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording. EEG's millisecond temporal resolution provides an exquisite window into the direct electrical consequences of neural processing, while fNIRS's superior spatial localization captures the metabolically coupled hemodynamic responses that support such activity. The neurovascular coupling mechanism binds these phenomena together, offering researchers a more complete picture of brain function than either modality could provide alone. Through appropriate experimental protocols and advanced fusion methodologies, researchers can leverage these complementary strengths to advance our understanding of brain function in both healthy and pathological states, paving the way for more precise diagnostics and innovative therapeutic interventions in clinical neuroscience.

In non-invasive neuroimaging, the trade-off between temporal and spatial resolution is a fundamental concept. Electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) represent two pillars of brain imaging, each with distinct resolution profiles. Temporal resolution refers to the precision with which a technique can measure when neural activity occurs, while spatial resolution describes its ability to pinpoint where in the brain this activity is generated [10] [11]. EEG is renowned for its millisecond-scale temporal resolution, enabling it to capture rapid neural dynamics. In contrast, fNIRS provides better spatial localization of cortical activity by measuring hemodynamic responses, though its temporal resolution is limited to seconds due to the slow nature of blood flow changes [10] [12]. This application note details the comparative strengths and limitations of these modalities and provides practical protocols for their integrated use in multimodal research, framed within the context of data fusion techniques for enhancing spatiotemporal imaging capabilities.

Technical Comparison of EEG and fNIRS

Quantitative Comparison of Resolutions

Table 1: Technical Specifications of EEG and fNIRS

| Feature | EEG (Electroencephalography) | fNIRS (Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy) |

|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Electrical activity from postsynaptic potentials of cortical neurons [10] | Hemodynamic response (changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin) [10] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (millisecond scale) [10] [13] | Low (seconds scale) [10] [14] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeter-level) [10] [14] | Moderate (better than EEG, but limited to outer cortex) [10] [12] |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface [10] | Outer cortex (~1–2.5 cm deep) [10] |

| Key Strength | Capturing rapid cognitive processes (e.g., sensory perception, ERPs) [10] | Localizing sustained cortical activity (e.g., workload, problem-solving) [10] |

| Primary Limitation | Spatial smearing due to volume conduction [13] | Indirect, slow hemodynamic response and superficial penetration [10] [12] |

Fundamental Limitations and Interdependence of Resolutions

The conventional depiction of temporal and spatial resolution as independent axes is an oversimplification. In practice, the factor that limits one resolution often degrades the other [13].

- EEG's Spatial Blurring Distorts Timing: The primary cause of EEG's poor spatial resolution is volume conduction—the blurring of electrical signals as they pass through the skull and other tissues [13]. This same effect distorts the recovered time course of the underlying neural sources at the scalp level. The recorded signal at any single electrode is a mixture of activities from multiple neural sources, which temporally smears their individual latencies. Techniques like the Surface Laplacian transform, which improves spatial resolution by estimating the Current Source Density (CSD), also secondarily provide a more accurate representation of the underlying source time courses [13].

- fNIRS's Slow Response Obscures Spatial Detail: The hemodynamic response measured by fNIRS evolves over several seconds [14]. If two adjacent brain regions are activated in rapid succession (e.g., with a few hundred milliseconds separation), the slow fNIRS signal will merge their responses into a single, spatially blurred activation, thereby degrading the effective spatial resolution for mapping rapid, sequential neural events [14].

Multimodal Fusion of EEG and fNIRS

The complementary strengths of EEG and fNIRS make them ideal candidates for multimodal fusion, which aims to achieve a comprehensive view of brain activity with high spatiotemporal resolution [7] [14]. Fusion can be implemented at different stages of data processing.

Fusion Approaches and Rationale

Table 2: Data Fusion Approaches for EEG and fNIRS

| Fusion Stage | Description | Key Techniques | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early-Stage Fusion | Raw or pre-processed data from both modalities are combined before feature extraction [15]. | Inputting concurrent EEG and fNIRS data into a Y-shaped neural network [15]. | Can capture underlying neurovascular coupling and subtle interactions; has shown higher classification performance in some BCI tasks [15]. |

| Data-Level / Symmetric Fusion | Data-driven methods that treat both modalities equally to find shared latent components [7]. | Joint Independent Component Analysis (jICA), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) [7]. | Can reveal complex, shared neural processes without strong prior assumptions [7]. |

| Model-Based / Asymmetric Fusion | Using one modality to constrain or inform the analysis of the other [14]. | Using high-spatial-resolution fNIRS (or DOT) reconstruction as a spatial prior to constrain the EEG source localization inverse problem [14]. | Dramatically improves the spatial resolution of reconstructed neuronal sources; allows resolution of spatially close sources activated with small temporal separations (e.g., 50 ms) [14]. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The rationale for fNIRS-EEG fusion is grounded in the principle of neurovascular coupling, where neuronal electrical activity triggers a subsequent hemodynamic response. The following diagram illustrates this relationship and a generalized experimental workflow.

Diagram Title: Neurovascular Coupling and Multimodal Fusion Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Imaging

Protocol 1: Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS Setup and Data Acquisition

This protocol ensures high-quality, synchronized data collection.

Equipment and Reagents:

- Integrated EEG-fNIRS system or two synchronized standalone systems.

- EEG cap with pre-defined fNIRS-compatible openings or a custom cap allowing co-registration of electrodes and optodes.

- EEG electrolyte gel and skin prepping supplies (abrasive gel, alcohol wipes).

- fNIRS optodes and holders.

- Head measurement tools for International 10-20 system placement.

- Synchronization hardware (e.g., TTL pulse generator) if systems are separate.

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Measure the participant's head according to the 10-20 system. Mark landmark positions (nasion, inion, pre-auricular points). Abrade the skin at electrode sites to reduce impedance to below 10 kΩ for high-density EEG or below 50 kΩ for lower-density setups [16].

- Cap and Sensor Placement: Secure the integrated cap on the participant's head. For EEG, inject electrolyte gel into the electrodes. For fNIRS, place optodes in their holders, ensuring good skin contact without excessive pressure. Use a cap with a tight but comfortable fit to minimize motion artifacts [10].

- Hardware Synchronization: If using separate systems, establish a synchronization link. A common method is to send a TTL pulse from a stimulus computer to both the EEG and fNIRS acquisition systems at the start of each trial to align the data streams during post-processing [10].

- Signal Quality Check: Verify EEG signal quality by inspecting for noise and impedance. Check fNIRS signal quality by ensuring a strong detected light intensity and checking for saturated or absent channels.

- Data Acquisition: Run the experimental paradigm (e.g., motor imagery, cognitive task) while recording synchronized EEG and fNIRS data.

Protocol 2: Joint EEG-fNIRS Source Reconstruction

This protocol uses fNIRS to spatially constrain EEG source analysis, enhancing spatial accuracy [14].

Equipment and Software:

- Computational software (e.g., MATLAB, Python).

- Toolboxes for EEG source analysis (e.g., FieldTrip, BrainStorm) and fNIRS reconstruction (e.g, HOMER, NIRS-Toolbox).

- Head model (e.g., from MNI template or individual MRI if available).

Procedure:

- Pre-processing: Process EEG and fNIRS data through separate, modality-specific pipelines.

- EEG: Apply band-pass filtering, artifact removal (e.g., ocular, muscle), and re-referencing.

- fNIRS: Convert raw light intensity to optical density, then to concentration changes in oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin. Perform motion artifact correction and band-pass filtering to remove physiological noise [12].

- fNIRS Source Reconstruction (Spatial Prior): Solve the fNIRS inverse problem to reconstruct the 3D distribution of the hemodynamic activity (e.g., Δ[HbO]) on the cortical surface. This provides a high-spatial-resolution map of activated regions [14].

- EEG Forward Modeling: Construct a head model and calculate the leadfield matrix, which defines how electrical currents from cortical sources project to the EEG electrodes [14].

- Joint Inversion: Incorporate the fNIRS reconstruction as a spatial prior constraint in the EEG inverse problem. Algorithms like Restricted Maximum Likelihood (ReML) can be used to fuse the high-temporal-resolution EEG data with the high-spatial-resolution fNIRS prior [14].

- Validation: Validate the reconstructed activity against known neurophysiological principles or task timings.

- Pre-processing: Process EEG and fNIRS data through separate, modality-specific pipelines.

Protocol 3: Early-Stage Fusion for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) Classification

This protocol uses a Y-shaped neural network to fuse EEG and fNIRS data at the raw data level for improved classification of mental states [15].

Equipment and Software:

- Pre-processed, synchronized EEG-fNIRS dataset.

- Machine learning environment (e.g., Python with PyTorch/TensorFlow).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Segment the synchronized EEG and fNIRS data into epochs time-locked to the events of interest (e.g., cue for motor imagery). Normalize the data.

- Network Architecture:

- Input Layer: Two separate input branches for EEG data and fNIRS data.

- Modality-Specific Encoders: The EEG branch can use a architecture like EEGNet to extract temporal and spectral features. The fNIRS branch, due to its lower temporal complexity, may use a simpler network (e.g., the later layers of EEGNet) to extract features from the hemoglobin concentration time series [15].

- Fusion Layer (Early-Stage): Concatenate the feature maps from both encoders at an early stage in the network, before the final classification layers.

- Classification Head: The concatenated features are fed into fully connected layers and a softmax output layer to generate the final classification (e.g., left vs. right hand motor imagery) [15].

- Training: Train the network using an appropriate optimizer and loss function (e.g., cross-entropy loss), validating performance on a held-out test set.

- Evaluation: Compare the classification accuracy of this early-fusion model against models using only EEG or only fNIRS, or against models using late-fusion (decision-level) strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Multimodal EEG-fNIRS Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated EEG-fNIRS Caps | Head caps with pre-defined placements for both electrodes and optodes, ensuring consistent co-registration across sessions [10]. | Essential for any multimodal study to ensure sensors are positioned correctly relative to each other and brain anatomy. |

| Conductive Electrolyte Gel | Reduces impedance between the scalp and EEG electrodes, facilitating the measurement of electrical potentials. | Standard requirement for obtaining high-quality EEG signals. |

| Short-Separation fNIRS Channels | fNIRS detectors placed very close (~8 mm) to a source, which are predominantly sensitive to systemic physiological noise in the scalp [7]. | Used as regressors in data processing to separate superficial (scalp) from deep (cortical) components of the fNIRS signal, improving signal quality [7]. |

| TTL Pulse Generator / Sync Box | A hardware device that sends precise digital timing pulses to multiple data acquisition systems. | Critical for synchronizing the clocks of separate EEG and fNIRS systems during simultaneous recording. |

| 3D Digitizer | A stylus-based system to record the precise 3D locations of EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes relative to head landmarks. | Improves the accuracy of source reconstruction by providing exact sensor positions for the forward model. |

| Surface Laplacian (CSD) Toolbox | Software (e.g., in EEGLAB) that computes the Current Source Density (CSD) from scalp potentials. | Used to reduce the spatial blurring effect of volume conduction in EEG, thereby improving both spatial and temporal resolution of scalp-level data [13]. |

Neurovascular coupling (NVC) describes the fundamental biological mechanism that creates a tight temporal and regional linkage between neural activity and subsequent changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF). This physiological process ensures that active brain regions promptly receive an increased supply of oxygen and nutrients to meet heightened metabolic demands [17]. The adult human brain constitutes approximately 2% of total body weight yet consumes over 20% of the body's oxygen and glucose at rest, creating a critical dependence on precisely regulated blood flow delivery [17]. The neurovascular unit, composed of vascular smooth muscle cells, neurons, and astrocyte glial cells, forms the anatomical foundation for this sophisticated communication system [17] [18].

The significance of neurovascular coupling extends beyond basic physiology to underpin modern functional neuroimaging techniques. Both functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) rely on the hemodynamic changes triggered by neural activity to indirectly map brain function [19] [3]. Understanding NVC is therefore paramount for proper interpretation of neuroimaging data across both research and clinical settings. impairments in neurovascular coupling have been implicated in various pathological conditions including Alzheimer's disease, stroke, hypertension, and diabetes, highlighting its clinical relevance [18] [1].

Biological Mechanisms of Neurovascular Coupling

Cellular Components and Signaling Pathways

The neurovascular unit operates through coordinated interactions between three primary cell types: neurons, astrocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Upon neuronal activation, glutamate released from presynaptic terminals activates postsynaptic neurons and surrounding astrocytes [17]. Neurons respond by activating neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), producing nitric oxide (NO) that directly dilates parenchymal arterioles [17]. Concurrently, astrocytes respond to glutamate through metabotropic glutamate receptors, triggering calcium-dependent production of vasoactive compounds [17] [19].

The signaling cascade in astrocytes involves production of arachidonic acid, which is subsequently metabolized into several vasoactive messengers: prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) via cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET) via cytochrome P450 (CYP) epoxygenase, and 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) via CYP4A [19]. These molecules collectively modulate vascular tone by acting on arterioles and capillaries. Additionally, GABA interneurons release various vasoactive substances including NO, acetylcholine, neuropeptide Y, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), which can produce both constrictive and dilatory effects on cerebral microvasculature [17].

Figure 1: Cellular Signaling Pathways in Neurovascular Coupling. This diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms through which neural activity triggers hemodynamic responses. Key pathways include neuronal nitric oxide production, astrocytic vasoactive compound synthesis, and interneuron-mediated regulation.

Hemodynamic Response Characteristics

The canonical hemodynamic response to neural activity follows a characteristic pattern known as "functional hyperemia." During baseline conditions, cerebral blood flow is closely matched to metabolic demands. Upon neural activation, a biphasic response occurs: an initial brief increase in deoxygenated hemoglobin (the "initial dip") followed by a substantial increase in cerebral blood flow that delivers oxygenated hemoglobin beyond metabolic requirements [17] [3]. This overcompensation results in a 4-fold greater increase in CBF relative to the increase in ATP consumption, forming the physiological basis for blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast used in fMRI [17].

The hemodynamic response profile varies between populations, with neonates and preterm infants demonstrating delayed and less pronounced responses compared to adults [18]. This developmental difference is attributed to ongoing maturation of neurovascular unit components including astrocytes and pericytes during early life [18]. The typical adult response to a stimulus produces a 10-20% increase in cerebral blood flow in the posterior cerebral artery and a 5-8% increase in the middle cerebral artery territory [18].

Quantitative Models and Analysis Frameworks

Mathematical Modeling of Neurovascular Coupling

Computational models of neurovascular coupling integrate complementary data from animal and human studies to create quantitative frameworks for predicting hemodynamic responses. Sten et al. (2023) developed a comprehensive mathematical model that preserves mechanistic behaviors across species by translating cell-specific contributions identified in rodent optogenetics studies to human applications [19]. Their model identifies distinct neuronal subpopulations responsible for different temporal components of the vascular response: NO-producing interneurons mediate the initial rapid dilation, pyramidal neurons sustain the main dilation during prolonged stimuli, and NPY-interneurons contribute to the post-stimulus undershoot [19].

These models enable more accurate interpretation of neuroimaging data by accounting for the complex, non-linear relationships between neural activity and hemodynamic responses. For example, they incorporate the interplay between cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2), cerebral blood flow (CBF), and cerebral blood volume (CBV) that governs the BOLD response [19]. Such quantitative frameworks are particularly valuable for understanding pathophysiological conditions where neurovascular coupling is impaired, including stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, and developmental disorders [18] [19].

Signal Analysis Techniques

Advanced signal processing methods have been developed to characterize neurovascular coupling in both task-based and resting-state paradigms. For spatiotemporal studies involving controlled stimuli, the hemodynamic response function can be modeled using general linear models that account for the typical delay and dispersion of the blood flow response relative to neural activity [7] [18]. Resting-state analyses employ correlation techniques, coherence analysis, and graph theory to identify spontaneous coupling between electrical and hemodynamic fluctuations [18].

Recent methodological advances include the application of Dirichlet distribution parameter estimation to model uncertainty in multimodal data fusion and Dempster-Shafer theory for evidence combination from heterogeneous signal sources [20]. These approaches are particularly valuable for integrating EEG and fNIRS measurements, as they provide formal frameworks for handling the different temporal characteristics and physiological origins of electrical and hemodynamic signals [20] [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters of Neurovascular Coupling

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Measurement Context | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBF Response to CO₂ | 1-6% per mm Hg CO₂ change | Global cerebral hemodynamics | Particularly sensitive in hypercapnic range [17] |

| Temporal Delay | 1-5 seconds post-stimulus | Adult sensory stimulation | Longer delays observed in neonates [18] |

| Hemodynamic Response Duration | 10-20 seconds | Brief sensory stimulus (e.g., finger tapping) | Duration depends on stimulus length and intensity [18] |

| Spatial Extent of CBF Increase | 10-20% in PCA, 5-8% in MCA | Task-activated regions | Varies by vascular territory [18] |

| Initial Dip Onset | 1-2 seconds post-stimulus | BOLD fMRI/fNIRS | Not always reliably detected [3] |

Multimodal Integration of EEG and fNIRS

Methodological Rationale and Advantages

The integration of electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) provides a powerful multimodal approach for investigating neurovascular coupling by simultaneously capturing electrical neural activity and hemodynamic responses [1]. These modalities offer complementary technical properties: EEG delivers millisecond-level temporal resolution of neural oscillations but limited spatial resolution, while fNIRS provides better spatial localization of hemodynamic changes with reasonable temporal resolution (typically up to 10 Hz) [21] [1]. Furthermore, the signals originate from distinct yet coupled physiological processes—EEG primarily reflects postsynaptic potentials of cortical pyramidal neurons, while fNIRS measures hemodynamic changes associated with neurovascular coupling [1].

The practical advantages of combined EEG-fNIRS systems include portability, non-invasiveness, relative tolerance to movement artifacts, and compatibility with naturalistic environments [7] [1]. This makes them particularly suitable for studying brain function in special populations including children, patients with implants, and those requiring bedside monitoring [21] [1]. The built-in validation provided by measuring both electrical and hemodynamic responses to neural activation strengthens the interpretation of observed brain activity patterns [1].

Data Fusion Strategies

Three primary methodological categories have emerged for analyzing concurrent EEG-fNIRS data:

EEG-informed fNIRS analysis: Using EEG features to guide the analysis of hemodynamic responses, particularly for event-related paradigms where precise timing from EEG can improve modeling of the delayed fNIRS response [1].

fNIRS-informed EEG analysis: Employing hemodynamic information to constrain source localization of electrical neural activity, addressing EEG's inherent spatial limitations [1].

Parallel EEG-fNIRS analysis: Processing both modalities independently followed by integrated interpretation, often using advanced fusion techniques such as classifier combination or evidence theory [20] [1].

Deep learning approaches have shown particular promise for multimodal fusion, with recent implementations using dual-scale temporal convolution and hybrid attention modules for EEG feature extraction combined with spatial convolution and gated recurrent units for fNIRS processing [20]. Decision-level fusion using Dempster-Shafer theory has achieved 83.26% accuracy in motor imagery classification, demonstrating the practical benefits of integrated analysis [20].

Figure 2: EEG-fNIRS Integration Workflow. This diagram outlines the major approaches for combining electrophysiological (EEG) and hemodynamic (fNIRS) data, including preprocessing steps, fusion strategies, and application domains.

Experimental Protocols for Neurovascular Coupling Assessment

Stimulus Paradigms and Experimental Design

Well-controlled stimulus paradigms are essential for reliable assessment of neurovascular coupling. In adult populations, standardized motor tasks such as finger tapping reliably activate contralateral motor cortex, producing measurable hemodynamic responses [18]. Visual stimuli using checkerboard patterns or flashing LEDs, and auditory stimuli using tone sequences or speech samples, effectively activate respective sensory cortices [18]. For neonatal and infant populations, flashing LEDs are particularly advantageous as they can be administered during sleep, minimizing movement artifacts [18].

Block-designed experiments, alternating between active and rest conditions, enhance the detection of stimulus-locked hemodynamic responses by improving signal-to-noise ratio through multiple trial averaging [3]. Event-related designs allow for more natural task structures and reduce habituation effects but typically require more sophisticated analysis approaches [3]. The selection of appropriate inter-stimulus intervals is critical, as the hemodynamic response requires 10-20 seconds to return to baseline following a brief stimulus [18].

Protocol Standardization Guidelines

To improve reliability and comparability across studies, standardized assessment protocols for neurovascular coupling should incorporate the following elements:

Physiological monitoring: Continuous measurement of end-tidal CO₂, blood pressure, and heart rate to account for systemic influences on cerebral hemodynamics [17].

Artifact handling: Implementation of robust artifact removal techniques, including short-separation channels for fNIRS to correct for superficial scalp blood flow contributions, and advanced algorithms for EEG artifact suppression [7] [21].

Stimulus characterization: Precise documentation of stimulus parameters (duration, intensity, modality) and timing synchronization between stimulus presentation and data acquisition [18].

Quality metrics: Establishment of predefined quality thresholds for signal-to-noise ratio, motion artifact contamination, and physiological noise levels for data inclusion [21] [3].

Recent methodological developments include automated software that coalesces repetitive trials into single contours and extracts multiple neurovascular coupling metrics including response latency, peak amplitude, and duration [17]. Such tools also facilitate normalization of responses to dynamic changes in arterial blood gases, which significantly influence the hyperemic response [17].

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Neurovascular Coupling Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Systems | Continuous-wave NIRS, Time-domain NIRS, Frequency-domain NIRS | Hemodynamic response measurement | CW-NIRS most common due to cost and simplicity [1] |

| EEG Systems | High-density EEG systems, Amplifiers, Active/passive electrodes | Neural electrical activity recording | Sampling rates typically 256-1024 Hz; higher than fNIRS [1] |

| Stimulation Equipment | LCD displays for visual patterns, Tactile stimulators, Auditory delivery systems | Controlled stimulus presentation | LED-based visual stimuli suitable for sleeping neonates [18] |

| Physiological Monitoring | Capnography, Pulse oximetry, Non-invasive BP monitoring | Control for systemic confounders | Essential for normalizing cerebral hemodynamic responses [17] |

| Analysis Software | Homer2, NIRS-SPM, EEGLAB, FieldTrip, Custom MATLAB scripts | Data processing and fusion | Increasing availability of open-source toolboxes [7] [1] |

| Computational Modeling Tools | MATLAB with custom scripts, Monte Carlo simulation packages | Quantitative modeling of NVC | Enables integration of animal and human data [19] |

Clinical Applications and Future Directions

Neurovascular coupling assessment has significant clinical utility across multiple neurological conditions. In critical care settings, fNIRS monitoring of cerebral oxygenation and autoregulation provides valuable information for managing patients with stroke, traumatic brain injury, and undergoing neurosurgical procedures [3]. The non-invasive nature and portability of fNIRS-EEG systems make them particularly suitable for prolonged monitoring in intensive care units [3].

In neurodegenerative disorders, impaired neurovascular coupling has been identified as a potential early biomarker for Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia [18] [1]. The combination of fNIRS with EEG offers a practical method for repeated assessment of neurovascular function in these patient populations [1]. Additionally, epilepsy monitoring benefits from simultaneous electrical and hemodynamic recording, as the spread of seizure activity involves complex neurovascular interactions that can be localized through multimodal integration [3].

Future methodological developments are likely to focus on several key areas. First, the creation of high-density whole-head optode arrays with anatomical co-registration will improve spatial accuracy and enable more reliable individual subject analysis [3]. Second, advanced signal processing techniques including vector diagram analysis to detect the initial dip in the hemodynamic response may enhance temporal precision for event detection [3]. Third, the integration of additional physiological parameters such as cytochrome oxidase measurements will provide more comprehensive assessment of metabolic function alongside hemodynamic responses [21] [3].

The expanding application of machine learning and deep learning approaches to multimodal data fusion promises to advance both basic understanding of neurovascular coupling and its clinical applications. These techniques enable more sophisticated pattern recognition in complex datasets and improve real-time classification of brain states for brain-computer interfaces and clinical monitoring systems [20] [3]. As these methodologies mature, standardized protocols for assessing neurovascular coupling will become increasingly important for translating research findings into clinical practice.

{article}

Naturalistic Brain Imaging: Advantages Over fMRI and PET in Real-World Settings

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and electroencephalography (EEG) are revolutionizing cognitive neuroscience by enabling brain imaging in naturalistic, real-world settings. This paradigm shift addresses a critical limitation of traditional neuroimaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), which require strict physical constraints and immobilization, thereby compromising ecological validity. This article details the technical advantages of portable fNIRS-EEG systems and provides structured Application Notes and Protocols for their use. Framed within a broader thesis on data fusion techniques, the content provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical methodologies for leveraging multimodal signal fusion to gain deeper, more authentic insights into brain function.

Traditional neuroimaging techniques, particularly fMRI and PET, have been foundational for human neuroscience. Functional MRI (fMRI) explores brain architecture and activity patterns by measuring the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal, offering high spatial resolution for localizing neural activity across the entire brain [22]. PET imaging relies on the use of radiolabeled tracers to measure metabolic processes, such as glucose utilization. However, a key assumption of these methods is that findings from highly controlled laboratory settings can be generalized to mental processes in real-world scenarios [23]. This assumption is increasingly being challenged.

The pursuit of ecological validity—the extent to which experimental findings reflect real-world behavior and experience—is driving the adoption of naturalistic neuroimaging [23]. This approach utilizes portable technologies like fNIRS and EEG to study the brain in dynamic, interactive contexts. Research has revealed significant differences in brain activation between traditional paradigms and those that approximate real life. For example, the amygdala, often identified as a "fear center" in studies using static threatening images, is not engaged in the same way during dynamic and prolonged fear experiences, suggesting that different neural systems underpin acute versus sustained affective states [23]. Moving beyond the scanner is therefore not merely a technical convenience but a necessity for a complete understanding of brain function.

Comparative Advantages of Portable Modalities

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of fMRI and PET compared to the portable modalities used for naturalistic imaging.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities for Real-World Settings

| Feature | fMRI | PET | fNIRS | EEG | fNIRS-EEG Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | High (millimeters) [22] | High (millimeters) | Moderate (centimeters) [24] | Low (centimeters) [24] | Enhanced & Complementary [24] |

| Temporal Resolution | Slow (1-5 seconds) [22] | Very Slow (minutes) | Slow (1-5 seconds) | Very Fast (milliseconds) [24] | Enhanced & Complementary [24] |

| Portability | No | No | Yes [25] [24] | Yes [24] | Yes [26] |

| Tolerance to Motion | Low | Low | High [25] | Moderate | High [25] |

| Measurement Type | Hemodynamic (BOLD) [22] | Metabolic (Glucose) | Hemodynamic (HbO/HbR) [24] | Electrical Activity [24] | Neurovascular Coupling [7] |

| Key Real-World Advantage | N/A (Scanner-bound) | N/A (Scanner-bound) | Bedside/ecological use [25] | Real-time tracking | Comprehensive brain activity decoding [7] |

The fusion of fNIRS and EEG creates a synergistic system that overcomes the limitations of each individual modality. EEG provides excellent temporal resolution to track rapid neural events, while fNIRS offers better spatial resolution for localizing the hemodynamic response associated with neural activity [24]. This combination is particularly powerful for studying complex, real-world cognitive processes and for applications in clinical populations where traditional scanning is impractical [25].

Data Fusion Techniques for EEG and fNIRS

Integrating signals from EEG and fNIRS requires sophisticated data fusion strategies. The choice of fusion stage presents a key research decision, with each level offering distinct advantages.

Table 2: Data Fusion Techniques for Multimodal EEG-fNIRS Data

| Fusion Stage | Description | Key Findings & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Early-Stage (Data-Level) Fusion | Raw or pre-processed data from both modalities is combined into a single data structure for input into a model. | Shown to significantly improve classification of motor imagery tasks compared to middle- or late-stage fusion [15]. |

| Feature-Level Fusion | Features are extracted from each modality separately and then concatenated into a combined feature vector. | Direct concatenation has performed on par with the best decision-level techniques in emotion recognition tasks [27]. |

| Decision-Level (Late) Fusion | Each modality is processed through separate models, and the final decisions (e.g., classifications) are combined. | Average-based soft voting has shown strong performance in emotion recognition across valence, arousal, and dominance dimensions [27]. |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a Y-shaped neural network, a common architecture for investigating these fusion strategies:

Multimodal Fusion Network - This Y-shaped network processes EEG and fNIRS signals through separate encoders before fusing them for a unified output.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Application Note 1: Motor Imagery for Neurorehabilitation

Background: Motor imagery (MI)-based neurofeedback is a promising tool for post-stroke motor rehabilitation, aiming to stimulate neuroplasticity in lesioned motor areas [26]. Unimodal neurofeedback has limitations, with approximately 30% of users unable to self-regulate brain activity effectively [26].

Objective: To assess the efficacy of multimodal EEG-fNIRS neurofeedback compared to unimodal (EEG-only or fNIRS-only) NF for upper-limb motor imagery.

Experimental Protocol:

- Participants: 30 right-handed healthy volunteers (as a precursor to clinical trials) [26].

- Equipment & Setup:

- fNIRS System: Continuous-wave system (e.g., NIRScout XP) with sources and detectors positioned over the sensorimotor cortices to measure changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated (HbR) hemoglobin [26].

- EEG System: 32-channel system (e.g., ActiCHamp) with electrodes positioned according to the 10-10 international system over sensorimotor areas [26].

- Integrated Cap: A custom cap holding both EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes to ensure concurrent recording and co-localization [26].

- Procedure:

- Participants undergo three randomized NF conditions in a single session: EEG-only, fNIRS-only, and combined EEG-fNIRS.

- Each trial presents a visual cue (e.g., a black arrow) for 2 seconds, indicating which hand to imagine moving.

- This is followed by a 10-second MI period, where participants perform kinesthetic motor imagery (e.g., imagining opening and closing a hand). During this period, a real-time NF score is calculated and presented as visual feedback (e.g., a moving ball on a gauge).

- The session includes a rest period of 10-12 seconds between trials [26].

- Data Fusion & Analysis:

- Real-time Processing: For the fused condition, an NF score is computed by integrating features from both modalities. The EEG feature is typically the event-related desynchronization (ERD) in the mu/beta band over the sensorimotor cortex. The fNIRS feature is the increase in HbO concentration in the contralateral motor cortex [26].

- Outcome Measures: Primary outcomes include the NF performance score and the amplitude of brain activity modulation in the targeted sensorimotor cortex. Exploratory outcomes include subjective reports of MI vividness and feeling of control over the NF [26].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Motor Imagery Protocol

| Item | Specification / Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS System | NIRScout XP (NIRx) with 16 detectors, 16 LED sources | Measures hemodynamic response (HbO/HbR) in the cortex during motor imagery. |

| EEG System | ActiCHamp (Brain Products) 32-channel amplifier | Records electrical brain activity (ERD/ERS) with high temporal resolution. |

| Integrated Cap | EasyCap (CNX-128) with integrated EEG & fNIRS holders | Ensures stable and co-registered positioning of all sensors on the scalp. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | MATLAB with Psychtoolbox or Presentation | Presents visual cues and the real-time neurofeedback metaphor to the participant. |

| Real-time Processing Platform | Custom software (e.g., via Lab Streaming Layer) | Synchronizes data streams, extracts features, computes NF score, and controls feedback. |

Application Note 2: Naturalistic Emotion Recognition

Background: Emotions are complex states that unfold dynamically in real-world contexts. Traditional experiments using static stimuli lack the ecological validity to capture these processes fully [23] [27].

Objective: To develop a personalized multi-modal fNIRS-EEG system for decoding the dynamic trajectories of emotional experiences in naturalistic settings.

Experimental Protocol:

- Stimuli: Use of ecologically valid stimuli such as movie clips known to elicit strong, dynamic emotional responses (e.g., fear, sadness, amusement) [23].

- Equipment & Setup:

- Similar to Protocol 4.1, using a portable, synchronized fNIRS-EEG system to allow for some participant movement and a more immersive experience.

- Procedure:

- Participants watch a series of movie clips while fNIRS and EEG data are recorded concurrently.

- Following each clip, participants provide continuous or discrete self-assessments of their emotional state along dimensions such as valence (pleasantness), arousal (intensity), and dominance [27].

- Data Fusion & Analysis:

- Feature Extraction: For EEG, features include spectral power in frequency bands of interest (e.g., alpha, beta). For fNIRS, features include the mean and slope of HbO and HbR time series.

- Fusion and Classification: Implement and compare feature-level (e.g., direct concatenation of features) and decision-level (e.g., soft voting of classifier outputs) fusion techniques [27].

- Validation: Use machine learning models to classify the self-reported emotional states and compare the classification accuracy of the fused system against unimodal benchmarks.

The workflow for such a naturalistic emotion study is outlined below:

Emotion Decoding Workflow - This protocol uses naturalistic stimuli and fused neuroimaging to decode emotional states.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of fNIRS and EEG represents a significant step toward truly naturalistic brain imaging, offering a compelling alternative to the scanner-bound environment of fMRI and PET. The synergistic combination of these modalities provides a more comprehensive picture of brain function by capturing complementary aspects of neural activity [24]. This is particularly valuable for tracking the dynamic, context-dependent, and personalized nature of cognitive and affective processes as they occur in real-world environments [23].

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on refining data-driven fusion techniques, such as source-decomposition methods, to better reveal latent neurovascular coupling processes [7]. Furthermore, the development of more miniaturized, robust, and user-friendly hardware will continue to push neuroimaging out of the laboratory and into clinics, homes, and real-world settings, opening unprecedented opportunities for diagnosing, monitoring, and treating neurological and psychiatric disorders [25] [28].

{/article}

Technical and Physical Basis of Signal Acquisition Methods

The integration of electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) represents a leading approach in non-invasive neuroimaging, capitalizing on the complementary strengths of each modality. This fusion provides a more comprehensive picture of brain activity by combining EEG's millisecond-level temporal resolution with fNIRS's superior spatial localization capabilities [7] [29] [6]. While EEG captures postsynaptic potentials from pyramidal neurons, reflecting electrical brain activity with high temporal precision, fNIRS measures hemodynamic responses associated with neural activity through near-infrared light, providing better spatial resolution and resistance to motion artifacts [29] [6]. This combination is particularly valuable for brain-computer interface (BCI) applications, clinical neurology, and neurorehabilitation research, where understanding both rapid neural dynamics and underlying metabolic processes is essential [7] [29]. The technical and physical foundations of these signal acquisition methods must be thoroughly understood to design effective experiments and implement appropriate data fusion strategies.

Technical Principles and Physical Foundations

Electroencephalography (EEG) Physical Basis

EEG measures electrical potentials generated by the synchronized postsynaptic activity of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex. These electrical signals originate from ionic currents flowing during neuronal excitation and inhibition, creating dipole fields that can be detected on the scalp surface [6]. The conductive properties of biological tissues (scalp, skull, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain) volume-conduct these signals, which typically range from 10 to 100 microvolts in amplitude. EEG electrodes detect voltage differences between active sites and reference points, capturing oscillatory activity across multiple frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma) that correlate with various brain states and cognitive processes.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of EEG Signal Acquisition

| Parameter | Specification | Physiological Basis | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Signal | Electrical potentials | Postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons | Voltage differences measured at scalp surface |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond level (<100 ms) | Direct measurement of neural firing | Limited only by sampling rate (typically 250-2000 Hz) |

| Spatial Resolution | ~1-3 cm (limited) | Signal smearing by volume conduction | Improved with high-density arrays (64-256 channels) |

| Frequency Bands | Delta (0.5-4 Hz), Theta (4-8 Hz), Alpha (8-13 Hz), Beta (13-30 Hz), Gamma (30-100 Hz) | Different cognitive states and processes | Filter settings critical for isolating bands of interest |

| Artifact Sources | Ocular, muscle, cardiac, environmental noise | Non-neural bioelectric activity, external interference | Requires robust artifact detection/correction strategies |

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) Physical Basis

fNIRS utilizes near-infrared light (typically 690-850 nm wavelengths) to measure hemodynamic changes in cortical tissue. The physical principle is based on the modified Beer-Lambert law, which describes light attenuation in scattering media like biological tissue [30]. At these wavelengths, light penetrates biological tissues effectively and is differentially absorbed by oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR), enabling quantification of changes in cerebral blood oxygenation associated with neural activity through neurovascular coupling.

The technique employs optical sources (emitting specific wavelengths) and detectors arranged on the scalp with specific separation distances (typically 3-4 cm), creating measurement channels. The differential pathlength factor (DPF) accounts for light scattering in tissue, while the partial volume factor (PVF) corrects for the fraction of the path that passes through brain tissue versus other tissues [30]. These are often combined into a partial pathlength factor (PPF) for practical application in concentration calculations.

Table 2: Key Characteristics of fNIRS Signal Acquisition

| Parameter | Specification | Physiological Basis | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Signal | Light attenuation | Hemoglobin absorption of NIR light | Measures HbO and HbR concentration changes |

| Temporal Resolution | ~0.1-1.0 seconds | Hemodynamic response delay (neurovascular coupling) | Limited by slow hemodynamic response (5-8 sec peak) |

| Spatial Resolution | 5-10 mm | Limited by source-detector separation (typically 3 cm) | High-density arrays enable tomographic reconstruction (HD-DOT) |

| Depth Sensitivity | Superficial cortex (1-3 cm) | Light scattering limits penetration | Short-separation channels help correct for superficial artifacts |

| Artifact Sources | Motion, scalp blood flow, systemic physiology | Non-cerebral hemodynamics, movement | Motion correction algorithms essential |

Complementary Nature of EEG and fNIRS

The synergy between EEG and fNIRS stems from their complementary measurement principles and spatiotemporal characteristics. EEG provides direct measurement of neural electrical activity with excellent temporal resolution, ideal for tracking rapid neural dynamics during cognitive tasks [6]. Conversely, fNIRS offers indirect measurement of neural activity via neurovascular coupling with better spatial specificity and resistance to movement artifacts, making it suitable for naturalistic environments [29] [6]. This complementary relationship enables more comprehensive brain monitoring, as each modality captures different aspects of brain function with different artifact profiles, providing built-in validation through neurovascular coupling principles [29].

Experimental Protocols for Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS Acquisition

Subject Preparation and Equipment Setup

Proper subject preparation is essential for high-quality simultaneous EEG-fNIRS data acquisition. Begin by measuring head circumference and selecting an appropriate integrated EEG-fNIRS cap size (e.g., Model M for 54-58 cm circumferences) [31]. Position the cap according to the international 10-20 or 10-5 system, ensuring comprehensive coverage of regions of interest (typically motor, prefrontal, and parietal cortices depending on the experimental paradigm) [31] [32].

For EEG setup, apply electrolytic gel to achieve electrode impedances below 10 kΩ, using the left or right mastoid as reference (M1/M2) [32] [33]. For fNIRS optode placement, ensure good skin contact without excessive pressure, verifying that source-detector pairs maintain approximately 3 cm separation to achieve optimal cortical sensitivity [31] [32]. Implement a synchronization trigger between EEG and fNIRS systems, typically using event markers transmitted from stimulus presentation software (e.g., E-Prime) to both acquisition systems simultaneously [31].

Table 3: Standardized Equipment Parameters for Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS

| Component | EEG Specifications | fNIRS Specifications | Integration Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition System | g.HIamp amplifier (g.tec) or Neuroscan SynAmps2 | NirScan (Danyang Huichuang) or NIRScout (NIRx) | Synchronized triggering capability |

| Sampling Rate | 256-1000 Hz | 7.8125-11 Hz | Integer ratio recommended for data fusion |

| Channel Count | 32-64 electrodes | 24-90 measurement channels | Co-registered positioning via integrated cap |

| Reference Scheme | Mastoid (M1/M2) or average reference | Short-separation channels (<1 cm) for superficial artifact removal | Anatomical co-registration of all elements |

| Stimulus Synchronization | Event markers from E-Prime 3.0 or equivalent | Same event markers as EEG | Simultaneous trigger to both systems |

Motor Imagery Paradigm Protocol

Motor imagery (MI) paradigms are widely used in BCI research and provide an excellent framework for demonstrating EEG-fNIRS integration. The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies used in recent multimodal datasets [31] [32]:

Pre-experiment Preparation: Conduct a grip strength calibration procedure using a dynamometer and stress ball to enhance motor imagery vividness. Have participants perform repeated 5 kg maximal force exertions followed by equivalent force applications using a stress ball, then practice grip training at one contraction per second [31].

Baseline Recording: Begin with 1-minute eyes-closed resting state followed by 1-minute eyes-open resting state, demarcated by an auditory cue (200 ms beep) [31].

Trial Structure: Implement the following sequence for each trial:

- Visual Cue (2 s): Present a directional arrow (left/right) or text/video cue indicating the required MI task [31] [32].

- Execution Phase (4-10 s): Display a fixation cross following an auditory cue (200 ms beep). Participants perform kinesthetic motor imagery of the specified movement (e.g., hand grasping) at approximately one imagined movement per second [31] [32].

- Inter-trial Interval (10-15 s): Blank screen or "Rest" instruction appears, allowing hemodynamic responses to return to baseline [31] [32].

Session Structure: Include at least 2 sessions per subject, with each session containing 15-40 trials per condition. Implement 5-10 minute breaks between sessions to mitigate fatigue effects [31] [32].

Task Variants: For upper limb MI, include multiple joint movements: hand open/close, wrist flexion/extension, wrist abduction/adduction, elbow pronation/supination, elbow flexion/extension, shoulder pronation/supination, shoulder abduction/adduction, and shoulder flexion/extension [32].

Cognitive Task Protocol (n-back Working Memory)

For cognitive studies, the n-back task provides a well-established paradigm for investigating working memory load:

Instruction Display (2 s): Present task instructions indicating 0-back, 2-back, or 3-back condition [6].

Task Period (40 s): Display a random one-digit number every 2 s for 0.5 s, followed by a 1.5-s fixation cross [6]. In 0-back, participants press target button for a specific pre-defined number; in 2-back/3-back, participants indicate whether current number matches the number shown 2/3 trials earlier.

Rest Period (20 s): Participants focus on a fixation cross while minimizing movement [6].

Block Structure: Each participant should complete multiple blocks (e.g., 20 trials × 3 series × 3 sessions) to ensure adequate statistical power [6].

Signal Processing Pathways and Data Fusion Approaches

Preprocessing Workflows

Diagram 1: EEG-fNIRS Preprocessing and Fusion Pathway. This workflow illustrates the parallel processing streams for EEG and fNIRS data before multimodal fusion, highlighting key steps including filtering, artifact correction, and feature extraction.

Preprocessing choices significantly impact downstream analysis and decoding performance. For EEG, optimal preprocessing typically includes high-pass filtering (≥1 Hz cutoff) to remove slow drifts, with evidence showing that higher high-pass filter cutoffs consistently increase decoding performance [34]. For fNIRS, motion correction is paramount, with algorithms like CBSI (correlation-based signal improvement), PCA, wavelet-based methods, and spline interpolation being commonly employed [30]. Physiological noise removal via bandpass filtering (0.01-0.5 Hz) effectively isolates hemodynamic responses from cardiac (~1-2 Hz), respiratory (~0.4 Hz), and Mayer wave (~0.1 Hz) interference [30].

Data Fusion Strategies

Diagram 2: Multimodal Fusion Hierarchy. This diagram categorizes the primary fusion strategies for EEG-fNIRS integration, ranging from early data-level fusion to late decision-level fusion, with associated methodologies and applications.

Three primary fusion approaches dominate EEG-fNIRS integration:

Early Fusion: Concatenating raw data or low-level features before classification, potentially improving performance but requiring temporal alignment of fundamentally different signal dynamics [6].

Intermediate Fusion: Employing cross-modal attention mechanisms or joint feature learning to model dynamic dependencies between modalities, automatically focusing on relevant signals across time and space [6].

Late Fusion: Processing modalities independently through specialized architectures (e.g., dual-branch networks) then fusing decisions using methods like Dempster-Shafer Theory (DST) to model and combine uncertainty estimates from each modality [20] [6].

Deep learning approaches have shown particular promise, with architectures like MBC-ATT employing independent branches for each modality with cross-modal attention mechanisms, achieving significant improvements in classification accuracy for cognitive tasks [6]. Similarly, evidence theory-based fusion using Dirichlet distribution parameter estimation and DST has demonstrated 3-5% accuracy improvements in motor imagery classification compared to unimodal approaches [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for EEG-fNIRS Acquisition and Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Hardware | Integrated EEG-fNIRS caps (Model M) | Simultaneous signal acquisition with co-registered positioning | Custom-designed caps with 32 EEG electrodes, 32 optical sources, 30 photodetectors [31] |

| Amplification Systems | g.HIamp amplifier (g.tec), Neuroscan SynAmps2 | EEG signal amplification and digitization | 64-channel systems with 1000 Hz sampling rate, mastoid reference [32] |

| fNIRS Systems | NirScan (Danyang Huichuang), NIRScout (NIRx) | Optical signal transmission and detection | Continuous wave systems with 690/830 nm wavelengths, ~10 Hz sampling [31] [32] |

| Stimulus Presentation | E-Prime 3.0, PsychToolbox | Experimental paradigm implementation | Precise timing control with synchronized triggers to both acquisition systems [31] |

| Preprocessing Tools | MNE-Python, Homer3, EEGLAB | Signal preprocessing and artifact removal | Standardized pipelines for filtering, referencing, motion correction [34] [30] |

| Fusion Frameworks | MBC-ATT, EEG-fNIRS evidence theory fusion | Multimodal integration and classification | Deep learning with cross-modal attention; Dempster-Shafer theory for uncertainty modeling [20] [6] |

| Validation Datasets | HEFMI-ICH, TU-Berlin-A, multimodal n-back | Method benchmarking and comparison | Public datasets with simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recordings [20] [31] [6] |

The technical and physical basis of EEG and fNIRS signal acquisition provides the foundation for effective multimodal brain imaging research. EEG's millisecond temporal resolution for capturing electrical neural activity complements fNIRS's superior spatial localization of hemodynamic responses, creating a powerful synergistic combination. The experimental protocols and processing pathways detailed in this document establish standardized methodologies for acquiring high-quality simultaneous data. Current research indicates that sophisticated fusion strategies, particularly deep learning approaches with cross-modal attention and evidence theory-based decision fusion, consistently outperform unimodal classification, with improvements of 3-5% in accuracy for motor imagery and cognitive tasks [20] [6]. As the field advances, focus on standardized preprocessing, artifact handling, and open-access datasets will be crucial for accelerating developments in multimodal brain imaging and its applications in BCI, clinical neurology, and cognitive neuroscience.

EEG-fNIRS Fusion Methods: From Basic Concatenation to Advanced Deep Learning

Data-level fusion, often termed early fusion or feature-level fusion, is a data integration strategy wherein raw data or low-level features from multiple sources are combined before being input into a machine learning or statistical model [35] [36]. In the context of cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, this approach involves the direct combination of raw or minimally processed signals from different modalities, such as EEG and fNIRS, into a single, unified dataset for subsequent analysis. This method stands in contrast to late fusion (decision-level fusion), where each modality is processed independently and their outputs are combined at the decision stage [35].

The principal advantage of early fusion lies in its potential to model low-level, cross-modal interactions that might be lost when processing modalities separately [36]. For EEG and fNIRS, which capture complementary aspects of brain activity—electrical and hemodynamic, respectively—early fusion allows a model to learn the complex, non-linear relationships between immediate neuronal firing (EEG) and the delayed hemodynamic response (fNIRS) directly from the data. This is particularly valuable for researching brain-computer interfaces, cognitive workload assessment, and the neurovascular correlates of neurological disorders, offering a more holistic view of brain function. However, this approach presents significant challenges, including the need for precise temporal alignment of signals, handling the high-dimensional feature spaces that result from concatenation, and managing the different sampling rates inherent to each modality [35] [37].

Preprocessing Pipelines for Individual Modalities

A rigorous and standardized preprocessing pipeline for each modality is a critical prerequisite for successful data-level fusion. Inconsistent or inadequate preprocessing can introduce artifacts and noise that obscure genuine neural signals and lead to unreliable fusion outcomes.

fNIRS Preprocessing Protocol

The goal of fNIRS preprocessing is to isolate the task-related hemodynamic response function (HRF) by removing physiological, instrumental, and motion artifacts from the raw optical intensity signals [38]. The following protocol, adaptable using toolboxes like HOMER3 or MNE-Python, outlines the essential steps [39].

Protocol: fNIRS Data Preprocessing

- Equipment Setup: Record fNIRS data using a continuous-wave system with sources emitting light at least two wavelengths (e.g., 700 nm and 850 nm) and corresponding detectors. Maintain a source-detector distance typically between 2.5 and 3.5 cm to ensure sufficient cortical penetration [38].

- Channel Selection: Identify and exclude channels where the source-detector distance is too short (e.g., < 1 cm) to detect a neural response [39].

- Intensity to Optical Density: Convert the raw light intensity signals to optical density (OD) to linearize the data with respect to chromophore concentration changes [39].

- Motion Artifact Correction: Apply motion artifact correction algorithms. The Savitzky-Golay filtering method is a common and effective choice for this step [40] [39].

- Bandpass Filtering: Apply a zero-phase bandpass filter (e.g., 0.01 - 0.7 Hz) to the OD data. The high-pass cutoff (0.01 Hz) removes slow drifts, while the low-pass cutoff (0.7 Hz) attenuates high-frequency physiological noise like heart rate (~1 Hz) [39].

- Convert to Hemoglobin: Use the Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL) with an appropriate partial pathlength factor (PPF, often 0.1) to convert the filtered OD data into concentration changes of oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated (HbR) hemoglobin [38] [39].

- Epoching: Segment the continuous HbO and HbR data into epochs time-locked to experimental events (e.g., -5 s to +15 s around a stimulus). Apply baseline correction (e.g., from -5 s to 0 s) to each epoch [39].

- Quality Control: Implement the Scalp Coupling Index (SCI) or similar metrics to identify and reject channels with poor signal quality. Manually inspect data and reject epochs with excessive artifact contamination [39].

EEG Preprocessing Protocol

EEG preprocessing aims to isolate neural activity from environmental and physiological artifacts to obtain clean event-related potentials (ERPs) or oscillatory features.

Protocol: EEG Data Preprocessing

- Data Import and Resampling: Import the raw data and downsample to a manageable frequency (e.g., 250 Hz) to reduce computational load, while respecting the anti-aliasing filter [40].

- High-Pass Filtering: Apply a high-pass filter (e.g., 1 Hz) to remove slow drifts and DC offsets [40].

- Line Noise Removal: Use a method like the

cleanlinefunction (in EEGLAB) to adaptively remove power line interference (e.g., 50/60 Hz and its harmonics) [40]. - Bad Channel Detection and Interpolation: Automatically detect and remove channels with excessive noise or artifacts. Interpolate the removed channels using spherical splines or other methods [40].

- Re-referencing: Re-reference the data to a common average reference to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR): Apply ASR, an automated method for removing short-duration, high-amplitude artifacts, using a parameter value (e.g., 20) that balances artifact removal with signal preservation [40].

- Laplacian Spatial Filter: Optionally, apply a surface Laplacian filter to reduce the effect of volume conduction and focus on cortical sources, which may better correlate with fNIRS signals [40].

Table 1: Summary of Key Preprocessing Steps for fNIRS and EEG

| Step | fNIRS | EEG |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Extract HRF | Extract ERP/Oscillations |

| Filtering | Bandpass (0.01-0.7 Hz) | High-pass (e.g., 1 Hz) & Line Noise Removal |

| Key Transformation | MBLL (to HbO/HbR) | Re-referencing, Spatial Filtering |

| Artifact Handling | Savitzky-Golay, SCI | Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) |

| Epoching | Around stimulus onset (e.g., -5 to 15 s) | Around stimulus onset (e.g., -0.2 to 1 s) |

Data-Level Fusion Methodology

Once the individual modalities are preprocessed, the core process of data-level fusion can begin. This involves bringing the data into a common representational space and combining them.

Temporal Alignment and Synchronization