fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS: A Comparative Guide to Principles, Applications, and Optimization in Modern Brain Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of three cornerstone neuroimaging techniques—functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)—tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS: A Comparative Guide to Principles, Applications, and Optimization in Modern Brain Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of three cornerstone neuroimaging techniques—functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)—tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and physiological basis of each modality, contrasting their spatial and temporal resolution. The scope extends to methodological applications in clinical and cognitive neuroscience, including multimodal integration strategies. It further addresses critical troubleshooting, optimization approaches, and reproducibility challenges, culminating in a rigorous validation and comparative analysis of their strengths and limitations. This synthesis aims to serve as a strategic resource for selecting and applying these tools in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Core Principles and Physiological Basis of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

Functional neuroimaging has revolutionized our understanding of the human brain by enabling non-invasive observation of brain activity in real time. Among the most prominent techniques in cognitive neuroscience and clinical research are functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). While each modality offers unique insights into brain function, they all relate—directly or indirectly—to the fundamental physiological process of neurovascular coupling, which links neural activity to subsequent changes in cerebral blood flow and oxygenation. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of these core neuroimaging modalities, with particular focus on their relationship to the hemodynamic response, their comparative strengths and limitations, and their application in contemporary neuroscience research and drug development.

Core Principles and Measurement Techniques

The Hemodynamic Response Function

The hemodynamic response function (HRF) represents the transfer function that links neural activity to the measured fMRI signal, effectively modeling the neurovascular coupling process [1]. When neurons become active, they trigger a complex physiological cascade that increases local cerebral blood flow to meet metabolic demands, typically occurring 2-6 seconds after the neural event [2] [3]. This delayed response follows a characteristic shape that can be mathematically modeled using a Gamma distribution, peaking approximately 4-6 seconds after stimulus onset before returning to baseline [3]. The HRF can be characterized by three primary parameters: response height (amplitude), time-to-peak (latency), and full-width at half-maximum (duration) [1].

The neurovascular coupling mechanism involves intricate relationships between neural activity, cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR), and vasodilation/vasoconstriction of local blood vessels [1]. Neurometabolic modulators released by glutamatergic and GABAergic interneurons directly and indirectly modulate CBF, with higher glutamate concentration resulting in taller, quicker, and narrower HRFs, while higher GABA has opposite effects [1]. This physiological foundation forms the basis for interpreting signals across all hemodynamic-based neuroimaging modalities.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

Physical and Physiological Basis

fMRI relies on the Blood-Oxygen-Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast mechanism, which exploits the different magnetic properties of oxygenated hemoglobin (diamagnetic) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (paramagnetic) [2] [4]. When neuronal activity increases in a specific brain region, the subsequent metabolic demand triggers an increased blood flow to that region, disproportionately increasing oxygenated hemoglobin relative to oxygen consumption [4]. This alters the local magnetic properties, detectable using T2*-weighted sequences sensitive to magnetic field variations [4].

Data Acquisition and Experimental Design

Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) serves as the primary acquisition method for fMRI studies, allowing whole-brain acquisition every 2-3 seconds [4]. fMRI experiments typically employ either block designs or event-related designs. Block designs alternate between periods of task performance and rest (e.g., 20 seconds of finger tapping followed by 20 seconds of rest), repeated multiple times to enhance signal detection [4] [5]. Event-related designs present discrete, short-duration stimuli with variable inter-stimulus intervals, allowing analysis of individual hemodynamic responses to each stimulus [5]. The correlation between the acquired fMRI data and the expected hemodynamic response curve is quantified mathematically by the correlation coefficient, with voxels demonstrating strong correlations interpreted as active regions [4].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Measurement Principle

fNIRS employs near-infrared light (650-1000 nm) to measure changes in cerebral hemoglobin concentrations [2] [6]. When light at specific wavelengths penetrates biological tissues, chromophores—particularly oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR)—exhibit characteristic absorption patterns [6]. By placing light sources and detectors on the scalp, fNIRS systems measure the attenuated light intensity, from which concentration changes of HbO and HbR can be computed using the Modified Beer-Lambert Law [6]. Continuous wave NIRS (CW-NIRS) represents the most extensively used approach in research and clinical settings due to its low cost and simplicity [6].

Physiological Basis and Relationship to fMRI

Like fMRI, fNIRS measures the hemodynamic response consequent to neural activity, with fNIRS measurements demonstrating similarity to the BOLD response obtained by fMRI [2] [6]. However, while fMRI's BOLD signal primarily reflects changes in deoxygenated hemoglobin, fNIRS separately quantifies both oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations [2]. This provides complementary information about the hemodynamic response, with HbO typically increasing and HbR decreasing during neuronal activation [6].

Electroencephalography (EEG)

Neural Basis and Signal Generation

EEG measures the brain's electrical activity via electrodes placed on the scalp, detecting voltage changes resulting from synchronized firing of cortical neurons, primarily pyramidal cells [7] [6]. These post-synaptic potentials represent the summed activity of tens of thousands of synchronized pyramidal neurons within the cortex, whose dendritic trunks are coherently orientated parallel to each other and perpendicular to the cortical surface, enabling sufficient signal summation to propagate to the scalp [6]. EEG signals are typically divided into characteristic frequency bands: theta (4-7 Hz), alpha (8-14 Hz), beta (15-25 Hz), and gamma (>25 Hz), each associated with different brain states and functions [6].

Relationship to Hemodynamic Measures

While EEG directly measures neural electrical activity with millisecond temporal resolution, it bears an indirect relationship to the hemodynamic response through neurovascular coupling [6]. The synchronized electrical activity detected by EEG represents the initial neural event that subsequently triggers the hemodynamic response measured by fMRI and fNIRS, providing complementary information about different aspects of brain function with distinct temporal characteristics.

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities

Table 1: Technical comparison of primary neuroimaging modalities

| Feature | fMRI | fNIRS | EEG |

|---|---|---|---|

| What it Measures | BOLD signal (deoxygenated hemoglobin) | HbO and HbR concentration changes | Electrical activity from cortical neurons |

| Spatial Resolution | High (millimeter-level) | Moderate (cortical surface only) | Low (centimeter-level) |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (seconds) | Moderate (1-2 seconds) | High (milliseconds) |

| Penetration Depth | Whole brain | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm) | Cortical surface |

| Portability | Low (requires MRI scanner) | High (wearable systems available) | High (wireless systems available) |

| Motion Tolerance | Low (highly sensitive to movement) | Moderate (relatively robust to motion) | Low (susceptible to movement artifacts) |

| Subject Limitations | Metal implants, claustrophobia | Limited to cortical measurements | Few limitations |

| Cost | High (equipment and scanning) | Moderate | Low to moderate |

| Acoustic Noise | High (120+ dB) | Minimal | Minimal |

Table 2: Experimental considerations for different research applications

| Research Context | Recommended Modality | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Studying rapid cognitive processes (e.g., sensory perception, attention) | EEG | Millisecond temporal resolution ideal for capturing rapid neural dynamics [7] |

| Localizing cortical activation during sustained tasks | fNIRS | Good spatial resolution for surface cortical areas with greater movement tolerance [2] [7] |

| Mapping deep brain structures | fMRI | Whole-brain coverage enables imaging of subcortical regions [2] |

| Naturalistic settings (classrooms, sports, clinical environments) | fNIRS | Portability and robustness to movement artifacts [2] [7] |

| Presurgical mapping | fMRI | Gold standard for identifying eloquent cortex relative to pathological structures [4] |

| Multimodal brain investigation | EEG + fNIRS | Complementary electrical and hemodynamic information with good portability [6] |

| Studies with sensitive populations (infants, children, patients) | fNIRS | Quiet operation, tolerance to movement, and no physical restrictions [2] |

Integrated Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Simultaneous fNIRS-fMRI Acquisition

Several studies have successfully combined fNIRS and fMRI to gain complementary insights into brain activity patterns. In a study by Jalavandi et al., simultaneous fNIRS and fMRI measurements during motor tasks showed strong correlation between modalities, validating fNIRS as a reliable alternative for subjects unable to undergo fMRI scans [2]. Similarly, Huppert et al. performed simultaneous fNIRS and fMRI measurements during parametric median nerve stimulation, finding good correspondence between the modalities [2].

Experimental Protocol: Simultaneous fNIRS-fMRI for Motor Tasks

- Participant Preparation: Screen for MRI contraindications; familiarize participant with motor tasks.

- Equipment Setup: Position fMRI-compatible fNIRS optodes over motor cortex regions using the international 10-20 system for placement consistency.

- Task Design: Implement block design with alternating 20-second periods of motor execution (e.g., wrist movement) and rest, repeated 6-8 times.

- Synchronization: Use TTL pulses from fMRI scanner to synchronize fNIRS and fMRI data acquisition.

- Data Acquisition: Collect simultaneous BOLD fMRI signals and fNIRS hemoglobin concentration changes throughout task performance.

- Data Analysis: Perform separate preprocessing pipelines followed by correlation analysis between BOLD signals and HbO/HbR concentration changes.

Concurrent fNIRS-EEG Recordings

The integration of EEG and fNIRS offers numerous benefits by exploiting their complementary strengths—EEG provides superior temporal resolution while fNIRS offers better spatial resolution and noise robustness [6]. Three primary methodological approaches have emerged for concurrent fNIRS-EEG data analysis: EEG-informed fNIRS analyses, fNIRS-informed EEG analyses, and parallel fNIRS-EEG analyses [6].

Experimental Protocol: Concurrent fNIRS-EEG for Cognitive Tasks

- Hardware Configuration: Use integrated EEG-fNIRS caps with predefined compatible openings to avoid sensor interference.

- Sensor Placement: Apply international 10-20 system for consistent placement of both EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes.

- Synchronization: Employ external hardware (TTL pulses) or shared acquisition software for temporal alignment of data streams.

- Task Paradigm: Implement event-related design with cognitive tasks (e.g., working memory, attention tasks) suitable for both electrical and hemodynamic response capture.

- Data Collection: Simultaneously record EEG electrical potentials and fNIRS hemoglobin concentration changes.

- Signal Processing: Apply separate preprocessing pipelines (filtering, artifact removal) followed by data fusion techniques such as joint Independent Component Analysis (jICA) or canonical correlation analysis (CCA).

HRF Characterization in Clinical Populations

The hemodynamic response function has demonstrated sensitivity to brain pathology and treatment response. In a study examining obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), HRF parameters (response height, time-to-peak, and full-width at half-maximum) were abnormal in OCD patients compared to healthy controls and normalized following cognitive-behavioral therapy [1]. Furthermore, pre-treatment HRF measures predicted treatment outcome with 86.4% accuracy using machine learning approaches [1].

Experimental Protocol: Resting-State HRF Characterization

- Participant Groups: Include patient population (e.g., OCD, depression) and matched healthy controls.

- Data Acquisition: Collect resting-state fMRI data over 8-10 minutes using standard EPI sequences.

- HRF Estimation: Perform deconvolution on pre-processed fMRI data to estimate voxel-level HRF parameters.

- Parameter Extraction: Calculate response height, time-to-peak, and full-width at half-maximum across regions of interest.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare HRF parameters between groups and correlate with clinical measures or treatment outcomes.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Neurovascular Coupling Pathway

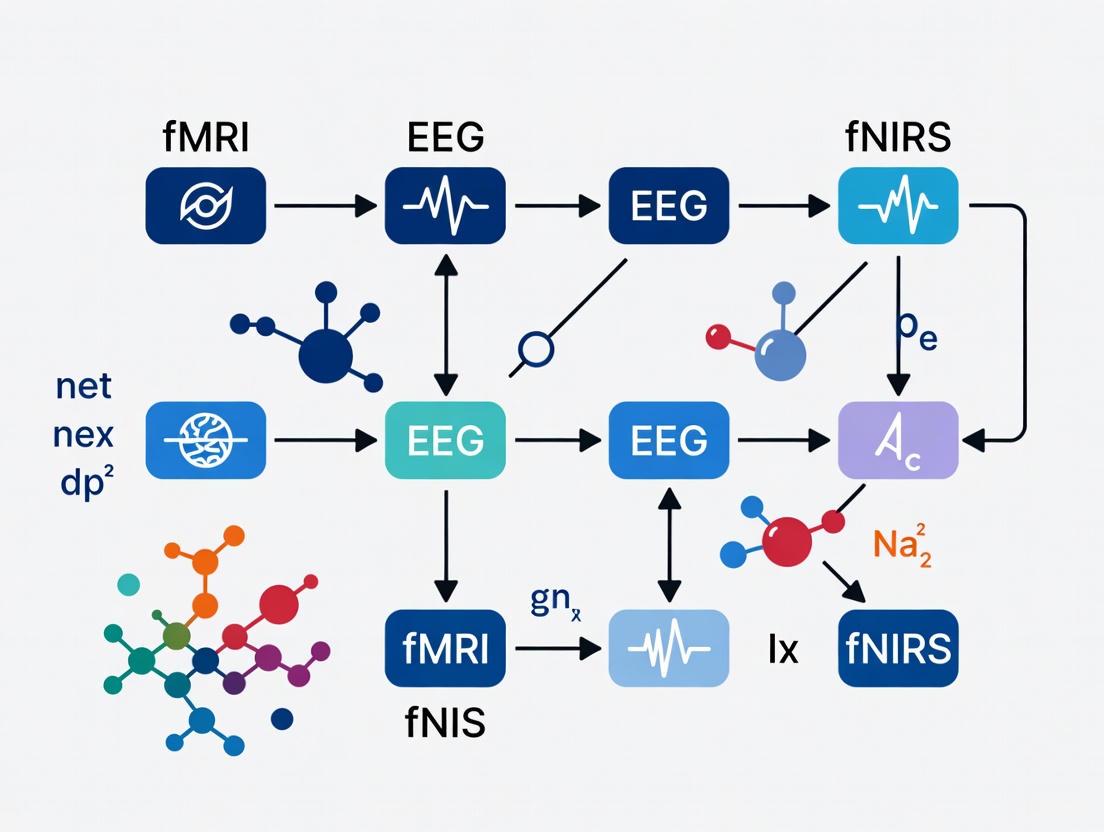

Diagram 1: Neurovascular coupling pathway linking neural activity to hemodynamic responses

Experimental Workflow for Multimodal Neuroimaging

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for concurrent EEG-fNIRS studies

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for neuroimaging studies

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI Contrast Agents (Gadolinium) | Enhances tissue contrast in MRI images by altering magnetic properties of water molecules [8] | Administered via IV injection; facilitates detailed visualization of organs, blood vessels, and abnormalities [8] |

| EEG Electrode Gel | Ensures conductive connection between scalp and electrodes for optimal signal acquisition [7] | Reduces impedance; requires proper scalp preparation; various conductivity formulations available |

| fNIRS Optode Holders | Secures light sources and detectors in predetermined positions on scalp [6] | Ensures consistent source-detector distances; compatible with EEG caps for multimodal studies |

| Disinfecting Solutions | Cleans EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes between uses | Prevents cross-contamination; maintains signal quality |

| Synchronization Hardware | Coordinates timing across multiple acquisition systems (TTL pulses, parallel ports) [6] | Essential for multimodal studies; ensures temporal alignment of data streams |

| Anatomical Localization Tools | Correlates functional data with anatomical structures (3D digitizers, MRI-compatible markers) [2] | Enables precise sensor placement and registration with structural images |

| Motion Stabilization Equipment | Minimizes head movement artifacts during data acquisition | Particularly important for EEG and fMRI; includes foam padding, chin rests, and bite bars |

The integration of multiple neuroimaging modalities represents the future of comprehensive brain investigation, leveraging the complementary strengths of each technique to overcome individual limitations. fMRI continues to serve as the gold standard for spatial localization of brain activity, particularly for deep structures, while fNIRS offers an adaptable alternative for cortical mapping in naturalistic settings and with challenging populations. EEG remains unparalleled for capturing the temporal dynamics of neural processing. The hemodynamic response function provides a critical link between these modalities, reflecting the fundamental neurovascular coupling process that translates neural activity into measurable signals. As research continues to elucidate the relationships between the HRF, neural activity, and various disease states, these neuroimaging approaches will play increasingly important roles in both basic neuroscience and clinical applications, including pharmaceutical development and personalized treatment approaches. The ongoing development of integrated multimodal platforms and analytical approaches promises to further enhance our ability to non-invasively probe human brain function in health and disease.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized non-invasive brain imaging since its development in the early 1990s, becoming a cornerstone of neurocognitive research and clinical practice [9]. The most common fMRI technique leverages the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast, which allows researchers and clinicians to visualize brain activity by detecting localized changes in blood oxygenation [10] [9]. This signal serves as an indirect marker of neural activity, capitalizing on the tight coupling between cerebral blood flow, energy demand, and neural firing [10]. The BOLD effect is fundamentally rooted in the magnetic properties of hemoglobin: oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic while deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic [9]. This difference causes deoxygenated hemoglobin to act as an intrinsic contrast agent that produces local distortions in the magnetic field, leading to a detectable loss of T2* MRI signal [10] [9].

When neurons become active, a complex neurovascular response is triggered. The ensuing metabolic demand drives a regional increase in cerebral blood flow that overcompensates for the local oxygen consumption [10] [9]. This results in a localized decrease in deoxyhemoglobin concentration relative to the baseline, thereby reducing its paramagnetic effect and causing an increase in the T2* signal detected by MRI [9]. These signal changes, while subtle—typically ranging from about 2% on a 1.5 Tesla scanner to approximately 12% on a 7 Tesla system—can be reliably measured with appropriate statistical methods [9]. The temporal dynamics of this response are characterized by a predictable latency; the BOLD signal onset is typically delayed by ∼2 seconds after neural activity, peaks after 6–12 seconds, and often exhibits a prolonged post-stimulus undershoot before returning to baseline [10].

The Physiological Basis of the BOLD Signal

Neurovascular Coupling and Hemodynamic Response

The BOLD signal is an indirect measure of brain activity that depends on the intricate process of neurovascular coupling—the relationship between neural activity, metabolic demand, and subsequent hemodynamic changes [6] [11]. When a brain region becomes active, it consumes more oxygen and nutrients, triggering a complex biochemical signaling cascade that ultimately increases local cerebral blood flow (CBF) to meet this heightened demand [6]. The exact mechanisms remain under investigation but likely involve chemical mediators such as nitrous oxide and glutamate, with possible participation from astrocytes [9].

This hemodynamic response exhibits characteristic temporal properties that fundamentally constrain the temporal resolution of BOLD fMRI. The typical timeline includes:

- Onset delay: ∼2 seconds after neural activity begins [10]

- Time to peak: 6-12 seconds to reach maximum amplitude [10]

- Return to baseline: A similar ramp down, often followed by a prolonged post-stimulus undershoot [10]

The observed BOLD signal intensity enhancement reflects an increase in CBF that overcompensates for the increased oxygen consumption, resulting in an oversupply of oxygenated blood to active regions [10]. This phenomenon was first documented by Fox and Raichle (1986), who observed that the increase in cerebral blood flow exceeds the increase in cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) during neural activation [10].

Biological Pathway of the BOLD Response

The following diagram illustrates the sequential physiological events that generate the measurable BOLD signal, from initial neural activation to the resulting MRI signal change.

Technical Implementation and Experimental Design

fMRI Acquisition and Pulse Sequences

BOLD fMRI detection requires specialized MRI pulse sequences sensitive to T2* variations. The most common approach involves using T2*-sensitive echo planar imaging (EPI) sequences, particularly gradient-echo (GRE) EPI, which can rapidly acquire whole-brain images [9]. Ogawa's initial discovery of BOLD contrast emerged from observations that gradient-echo pulse sequences produced signal dropouts from blood vessels due to susceptibility effects from deoxyhemoglobin, while spin-echo sequences did not [10]. Each individual scan through the brain typically takes between 333-3000 milliseconds depending on scanner model and pulse sequence parameters, enabling repeated sampling of the brain's hemodynamic state over time [9].

The sensitivity of BOLD fMRI is significantly influenced by magnetic field strength. Higher field strengths (e.g., 3T, 7T, and above) provide greater BOLD signal changes and improved spatial resolution [12] [9]. Recent advances in ultra-high field (7T) MRI have enabled more detailed investigations, including laminar fMRI that can differentiate activity across cortical layers with resolutions approaching 1 mm³ [12]. Innovative multi-contrast approaches now combine BOLD with complementary measures like cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) to provide a more comprehensive characterization of neurovascular responses [12].

Experimental Paradigms and Design

BOLD fMRI experiments employ standardized paradigms to elicit and measure brain activity:

Table 1: Common fMRI Experimental Paradigms

| Paradigm Type | Design | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block Design | Stimuli presented in extended blocks (e.g., 20-30s) alternating with rest periods [9] | High statistical power for detecting activation [9] | Predictable presentation may induce habituation or strategy effects |

| Event-Related Design | Stimuli presented at random or pseudorandom intervals [9] | More naturalistic presentation; can model hemodynamic response to single events [9] | Lower statistical power than block designs |

| Mixed Designs | Combination of block and event-related elements | Benefits of both approaches; can separate sustained and transient activity | Increased analytic complexity |

Clinical applications, particularly presurgical mapping, require special considerations. The Organization for Human Brain Mapping (OHBM) Clinical fMRI Working Group has established consensus recommendations for clinical language mapping, emphasizing task designs optimized for specific clinical objectives and modifications for patients with existing impairments [13]. For example, establishing language dominance often requires multiple language tasks targeting different components of the language system [13].

Analysis and Interpretation of BOLD Signals

Preprocessing and Statistical Analysis

fMRI data analysis involves multiple stages to transform raw MR images into interpretable statistical maps of brain activation:

Preprocessing: Corrects for various confounding factors including patient head motion, slice timing differences, and image noise or artifacts [9]. In research settings, preprocessing often includes spatial normalization to align images to a common anatomical space or atlas [9].

Statistical Analysis: Employs voxel-wise statistical comparisons of T2* signal between task and control conditions [9]. Common approaches include:

- General linear model (GLM)

- Correlation analysis

- Voxel-wise t-tests

The final output is a statistical map showing voxels where stimulus-related activation exceeds a specified threshold (e.g., p-value, t-value, or z-score) [9]. For clinical applications, statistical thresholds often require individual customization due to inter-subject variability in cerebrovascular responsiveness, whereas research studies typically apply uniform thresholds across subjects with appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons [9].

Relationship to Underlying Neural Activity

A critical consideration in BOLD fMRI interpretation is understanding what specific aspects of neural activity the signal reflects. The BOLD signal appears to be more closely tied to local field potentials (LFPs) and input processing rather than spiking output [10]. Extracellular recordings suggest that the BOLD signal represents the weighted sum of all sinks and sources along multiple cells—essentially reflecting integrated synaptic activity rather than individual action potentials [10].

This relationship becomes particularly important when interpreting negative BOLD responses (NBR), which can reflect either reduced neuronal activity or heightened neuronal activity under certain conditions, depending on the complex interplay between CBF, CBV, and CMRO2 [12]. Advanced multi-contrast laminar fMRI at 7T has demonstrated distinct neurovascular and metabolic responses across cortical layers, suggesting potential feedback inhibition of neuronal activities in both superficial and deep cortical layers underlying negative BOLD signals [12].

Advanced Applications and Multimodal Integration

Clinical Applications of BOLD fMRI

BOLD fMRI has established significant clinical utility, particularly in presurgical planning:

Table 2: Primary Clinical Applications of BOLD fMRI

| Application | Purpose | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Presurgical Mapping | Identify eloquent cortex (motor, language, visual) near surgical targets [13] [9] | Define surgical risk, aid operative planning, expedite intraoperative mapping [9] |

| Language Lateralization | Determine hemisphere dominance for language functions [13] | Inform patient consent, decide whether to proceed with surgery [13] |

| Cerebrovascular Reactivity | Assess vascular reserve in patients with cerebrovascular disease [9] | Identify regions with impaired vasodilatory capacity [9] |

When combined with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) for visualizing white matter tracts, fMRI has been shown to reduce postoperative neurologic deficits [9]. However, it is crucial to recognize that fMRI provides statistical activation maps at arbitrary thresholds rather than direct anatomical representations, which must be considered when integrating them into surgical navigation systems [9].

Integration with EEG and fNIRS in Multimodal Studies

BOLD fMRI serves as a cornerstone in multimodal brain imaging approaches, often combined with electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to overcome the inherent limitations of each individual technique:

EEG-fMRI Integration: EEG provides millisecond-level temporal resolution of electrical brain activity, complementing fMRI's spatial precision [6]. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI recording presents technical challenges but enables direct correlation of electrical and hemodynamic brain events [6].

fNIRS-fMRI Integration: fNIRS measures hemodynamic changes using near-infrared light, providing a portable alternative for measuring brain oxygenation [6] [11]. Simultaneous fNIRS-fMRI studies have demonstrated correlations between BOLD signals and hemoglobin concentration changes, validating fNIRS as a reliable hemodynamic measure [14] [11]. This integration is particularly valuable for studies in naturalistic settings where MRI scanners cannot be used [11].

The combination of these modalities capitalizes on their complementary strengths: fMRI's high spatial resolution, EEG's exceptional temporal resolution, and fNIRS's portability and suitability for long-term monitoring [6] [11]. This multimodal approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of brain function across different spatiotemporal scales and experimental contexts.

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions in BOLD fMRI Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| MRI Scanner | Image acquisition with T2* sensitivity | Clinical (1.5T, 3T) to research (7T, 11T) field strengths [12] [9] |

| EPI/GRE Pulse Sequence | T2*-weighted image acquisition | Enables rapid whole-brain imaging; sensitive to magnetic susceptibility [9] |

| Visual Presentation System | Stimulus delivery | MRI-compatible goggles, projectors, or LCD screens with precise timing [9] |

| Auditory Presentation System | Auditory stimulus delivery | MRI-compatible headphones or ear buds with artifact minimization [9] |

| Response Recording Device | Subject performance monitoring | MRI-compatible button boxes, joysticks, or eye-tracking systems [13] |

| Physiological Monitoring | Cardiorespiratory recording | Pulse oximetry, respiration monitoring for noise correction [9] |

| Analysis Software | Data processing and statistical mapping | FSL, SPM, AFNI; commercial clinical packages [9] |

The BOLD signal has fundamentally transformed our ability to noninvasively investigate human brain function, providing a window into the complex interplay between neural activity, metabolism, and hemodynamics. While technically challenging and methodologically complex, BOLD fMRI continues to evolve through advancements in high-field imaging, sophisticated analysis techniques, and multimodal integration. Understanding its physiological basis, technical implementation, and analytical approaches is essential for proper interpretation and application across basic neuroscience and clinical domains. As technological innovations continue to emerge, BOLD fMRI remains an indispensable tool for unraveling the functional organization of the human brain.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive neurophysiological technique that measures the brain's spontaneous electrical activity from the scalp surface. First described by Hans Berger in 1929, EEG records the summation of synchronous postsynaptic potentials from billions of cortical neurons, primarily pyramidal cells [6] [15]. These electrical signals represent the macroscopic activity of the brain surface, requiring at least 6 square centimeters of synchronized cortical activity to be detectable by scalp electrodes [16]. The exquisite temporal resolution of EEG (on the millisecond scale) enables researchers to capture neural dynamics associated with rapid cognitive processes, making it an indispensable tool for studying brain function in both research and clinical settings [6] [17].

The electrical potentials measured by EEG originate mainly from excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents generated by cortical pyramidal neurons. When many neurons within a narrow timeframe are activated, their current dipoles summate, producing measurable voltage fluctuations on the scalp [15]. The rhythmic oscillatory patterns of EEG reflect synchronized activity of neuronal circuits connecting different brain regions, with thalamic pacemaker neurons synchronizing cortical firing to generate characteristic rhythms [15]. This neurophysiological foundation enables EEG to serve as a direct measure of neural electrical activity, contrasting with hemodynamic-based techniques like fMRI and fNIRS that measure metabolic responses coupled to neural activity [6].

Core Electrophysiological Principles

From Neuronal Firing to Scalp Potentials

At the cellular level, the genesis of EEG signals begins with the electrical properties of individual neurons. Neuronal membranes maintain a resting potential of approximately -70mV through ion channels, most notably the sodium-potassium pump that exchanges three Na+ ions out for every two K+ ions into the cell [16]. When a neuron receives excitatory input, neurotransmitter binding leads to depolarization through the opening of Na+/K+ channels, causing Na+ influx that shifts the intracellular voltage toward positive values (e.g., from -70mV to -20mV) [16]. This depolarization creates a relatively negative voltage outside the cell, which EEG electrodes can detect when summed across thousands of synchronously activated neurons.

Critical to EEG generation is the specific architecture of cortical pyramidal neurons. Their dendritic trunks are coherently oriented, parallel with each other and perpendicular to the cortical surface, enabling sufficient summation and propagation of electrical signals to the scalp [6]. The arrangement creates what is effectively a dipole field, with charge separations that can be detected at a distance. When superficial cortical layers undergo excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs), the extracellular space near the scalp becomes negatively charged, producing negative deflections on EEG. Conversely, deep EPSPs or superficial inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) produce positive scalp deflections [16]. This relationship is crucial for accurate interpretation of EEG waveforms.

Table 1: Neural Events and Their EEG Correlates

| Neural Event | Cortical Depth | Extracellular Potential | EEG Deflection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitatory (EPSP) | Superficial | Negative | Upward (Negative) |

| Excitatory (EPSP) | Deep | Positive | Downward (Positive) |

| Inhibitory (IPSP) | Superficial | Positive | Downward (Positive) |

| Inhibitory (IPSP) | Deep | Negative | Upward (Negative) |

Signal Characteristics and Limitations

EEG signals possess distinctive characteristics that determine their utility and limitations in brain research. The voltage fluctuations measured on the scalp are typically in the range of 10-100 microvolts, requiring significant amplification for analysis [18]. Several factors constrain what EEG can detect: the electrical signals must pass through cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp, which act as a low-pass filter attenuating high-frequency components and spatially blurring the source signals [6]. This biological filtering effect contributes to EEG's limited spatial resolution, as the electrical activity from a localized cortical region spreads before reaching scalp electrodes.

The orientation of neuronal dipoles significantly impacts their detectability on scalp EEG. Dipoles perpendicular to the cortical surface are well-detected, while those parallel or tangential to the scalp are poorly seen or missed completely [16]. This has important implications for localizing brain activity, particularly in regions with complex cortical folding patterns. For instance, activity originating in the interhemispheric fissure with transverse dipoles may appear to come from the contralateral hemisphere, creating potential false localization [16]. Understanding these fundamental principles is essential for proper experimental design and interpretation of EEG findings in research contexts.

EEG Signal Acquisition Methodology

Electrode Systems and Placement

Standardized electrode placement follows the International 10-20 system or its higher-resolution variants (10-10, 10-5 systems), which ensures consistent positioning relative to cranial landmarks and proportional coverage across head sizes [18] [19]. This system uses specific anatomical reference points (nasion, inion, preauricular points) to create a coordinate system for electrode placement, with letters indicating brain regions (F-frontal, C-central, P-parietal, O-occipital, T-temporal) and numbers indicating specific positions within those regions [19]. Modern high-density EEG systems can utilize 128, 256, or more electrodes to provide improved spatial sampling of brain electrical activity.

During acquisition, voltage differences between each electrode and a reference electrode are measured and amplified [6]. The choice of reference significantly influences the recorded signals, with common options including linked ears, averaged reference, or cephalic references. Proper electrode application requires careful skin preparation and conductive gel to maintain impedance below 5-10 kΩ, ensuring optimal signal quality [18]. Modern systems increasingly use active electrodes with built-in impedance conversion to improve signal quality and reduce environmental interference.

Technical Considerations and Equipment

EEG acquisition systems consist of electrodes, amplifiers, filters, and analog-to-digital converters. Amplifiers must have high common-mode rejection ratios (typically >100 dB) to reject noise that appears equally at all electrodes while amplifying the differential signals of interest [18]. Signal filtering is applied during acquisition, with typical bandpass settings of 0.1-100 Hz to capture relevant neural activity while excluding non-physiological frequencies. The sampling rate must be sufficiently high (usually 200-1000 Hz or higher) to avoid aliasing while capturing the frequency content of interest [20].

Equipment for EEG acquisition ranges from traditional laboratory-based systems to increasingly portable and wearable devices. Research-grade systems typically offer high channel counts (64-256 channels), precision timing, and extensive support for multimodal integration [18]. Portable systems such as the Emotiv EPOC (14 channels) and Muse (4 channels) provide greater flexibility for naturalistic experiments but with potentially reduced signal quality and spatial resolution [18]. The emergence of wearable EEG technology has enabled field studies and long-term monitoring outside traditional laboratory settings, expanding the methodological possibilities for brain research.

Table 2: EEG Acquisition Systems and Their Characteristics

| System Type | Channel Count | Portability | Typical Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research-grade | 64-256+ | Low | Laboratory studies, clinical | High signal quality, precise timing |

| Clinical | 19-32 | Moderate | Diagnostic medicine | Standardized montages, medical safety |

| Portable/Wearable | 4-32 | High | Field studies, BCI, monitoring | Trade-offs between mobility and data quality |

EEG Signal Processing and Analysis

Preprocessing and Denoising

Raw EEG signals are invariably contaminated with various artifacts and noise sources that must be addressed before meaningful analysis. Major artifact sources include ocular movements (EOG), muscle activity (EMG), cardiac signals (ECG), skin potentials, and environmental interference such as power line noise [18] [21]. Effective preprocessing pipelines typically include multiple stages: filtering (bandpass, notch), artifact detection, and correction or rejection of contaminated segments.

Advanced preprocessing techniques include Independent Component Analysis (ICA), which separates statistically independent sources from the recorded signals, enabling identification and removal of artifact-related components while preserving neural activity [18]. Other methods include regression-based approaches, blind source separation, and adaptive filtering. The specific choice of preprocessing methods depends on the experimental paradigm, artifact types, and subsequent analysis goals. Validation of preprocessing effectiveness is crucial, often involving both automated metrics and visual inspection to ensure meaningful neural signals are preserved while artifacts are adequately addressed.

Feature Extraction and Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative EEG (qEEG) analysis transforms raw waveforms into measurable features that characterize brain states and cognitive processes. The most fundamental analysis approach involves decomposing the EEG signal into characteristic frequency bands, each associated with different functional states [15]:

- Delta (0.1-4 Hz): Prominent in deep sleep, coma

- Theta (4-8 Hz): Seen in drowsiness, meditation

- Alpha (8-12 Hz): Characteristic of relaxed wakefulness with eyes closed

- Beta (12-30 Hz): Dominant during active thinking, focus

- Gamma (>30 Hz): Associated with cognitive engagement, sensory binding

Multiple mathematical approaches are available for feature extraction from EEG signals. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) calculates power spectral density to quantify the distribution of signal power across frequency bands [15] [21]. Wavelet Transform (WT) provides time-frequency representation with variable window sizes, offering superior analysis of non-stationary signals like EEG [21]. Eigenvector methods (Pisarenko, MUSIC, Minimum Norm) estimate signal frequency and power from noise-corrupted measurements [21]. Each method has distinct advantages and limitations, with selection depending on the specific analysis goals and signal characteristics.

Figure 1: EEG Signal Processing Pipeline

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Experimental Paradigms

EEG research employs standardized protocols to investigate specific cognitive processes and brain functions. Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) are obtained by time-locking EEG segments to stimulus events and averaging across multiple trials to extract consistent neural responses embedded in background activity [18]. Common ERP components include the P300 (associated with attention and context updating), N400 (language processing), and MMN (deviance detection). These components provide precise temporal information about cognitive processes with millisecond resolution.

Resting-state EEG protocols record spontaneous brain activity during awake, relaxed states with eyes closed or open, providing measures of baseline brain dynamics and functional connectivity [19]. Quantitative features derived from resting-state EEG, such as spectral power ratios and network connectivity metrics, serve as biomarkers for various neurological and psychiatric conditions. Task-based EEG paradigms engage specific cognitive functions through carefully designed experimental tasks, enabling researchers to study the neural correlates of perception, attention, memory, decision-making, and other cognitive processes.

Clinical and Applied Protocols

In clinical neuroscience, specialized EEG protocols facilitate diagnosis and monitoring of neurological disorders. For epilepsy evaluation, prolonged EEG monitoring captures interictal and ictal activity, with automated detection algorithms employing measures of signal amplitude variation, pattern regularity, and frequency characteristics to identify seizure patterns [20]. In critical care settings, continuous EEG monitoring detects nonconvulsive seizures in comatose patients, utilizing quantitative trend analysis to simplify review of extended recordings [20].

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) protocols establish real-time communication between brain activity and external devices, often using sensorimotor rhythms, P300 responses, or steady-state visually evoked potentials as control signals [18]. These protocols require specialized signal processing for real-time feature extraction and classification, with applications in assistive technology, neurorehabilitation, and human-computer interaction. Each protocol type demands specific experimental design considerations, including appropriate control conditions, trial structure, and timing parameters to ensure valid and interpretable results.

Comparative Framework with Other Neuroimaging Modalities

EEG versus fNIRS: Complementary Strengths

EEG and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) represent complementary approaches to non-invasive brain imaging, each with distinct strengths and limitations. While EEG measures direct electrical neural activity with millisecond temporal resolution, fNIRS detects hemodynamic responses (changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin) with slower temporal resolution (seconds) but better spatial localization for cortical areas [6] [17]. This fundamental difference in measured signals creates opportunities for multimodal integration that leverages the advantages of both techniques.

The spatial resolution of EEG is limited by the volume conduction of electrical signals through head tissues, typically localizing activity to regions of several square centimeters. fNIRS provides better spatial resolution for superficial cortical areas but is limited to measuring outer cortical layers (1-2.5 cm depth) [17]. fNIRS is more tolerant of movement artifacts than EEG, making it suitable for studies involving natural movements, children, or real-world environments [17]. The choice between modalities depends on the research question, with EEG preferred for studying rapid neural dynamics and fNIRS advantageous for investigating localized cortical activity during naturalistic tasks.

Table 3: Comparison of EEG and fNIRS Characteristics

| Characteristic | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|

| What is Measured | Electrical activity of neurons | Hemodynamic response (blood oxygenation) |

| Signal Source | Postsynaptic potentials in cortical neurons | Changes in oxygenated/deoxygenated hemoglobin |

| Temporal Resolution | High (milliseconds) | Low (seconds) |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeter-level) | Moderate (better than EEG) |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm deep) |

| Sensitivity to Motion | High | Low |

| Portability | High | High |

| Best Use Cases | Fast cognitive tasks, ERP studies, seizure detection | Naturalistic studies, child development, motor rehabilitation |

Multimodal Integration: EEG-fNIRS

Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS recording provides comprehensive assessment of brain function by capturing both electrical neural activity and hemodynamic responses [6] [19]. This multimodal approach enables investigation of neurovascular coupling - the relationship between neural activity and subsequent cerebral blood flow changes [6]. Integration approaches include EEG-informed fNIRS analysis, fNIRS-informed EEG analysis, and parallel analyses that combine information from both modalities [6].

Technical implementation of simultaneous EEG-fNIRS requires careful consideration of sensor placement compatibility, typically using integrated caps with predefined positions for both electrodes and optodes following the 10-20 system [17]. Hardware synchronization ensures temporal alignment of data streams, while specialized processing pipelines address modality-specific artifacts and combine features for enhanced classification of brain states [17] [19]. Multimodal integration has demonstrated particular utility in brain-computer interfaces, where combined electrical and hemodynamic features improve classification accuracy and information transfer rates compared to either modality alone.

Figure 2: EEG and fNIRS Complementary Strengths and Multimodal Integration

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit for EEG research encompasses specialized equipment, software resources, and methodological components that enable comprehensive investigation of brain electrical activity. These tools facilitate signal acquisition, processing, analysis, and interpretation across diverse experimental contexts.

Table 4: Essential EEG Research Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Systems | Research-grade EEG systems (BrainAmp, Biosemi), Portable systems (Emotiv EPOC, Muse) | Signal recording with precise timing and amplification |

| Electrodes & Supplies | Active/passive electrodes, Electrode caps, Conductive gel, Abrasive preparations | Signal transduction from scalp to recording system |

| Analysis Software | EEGLAB, Brainstorm, MNE-Python, FieldTrip | Signal processing, visualization, and statistical analysis |

| Quantitative Tools | qEEGt Toolbox, VARETA source imaging | Normative comparison, source localization, spectral analysis |

| Experimental Platforms | Presentation, E-Prime, PsychToolbox | Stimulus presentation and experimental control |

| Reference Databases | Cuban Human Brain Mapping Project, CAMCAN | Normative comparisons, methodological validation |

Advanced analytical tools like the qEEGt Toolbox enable quantitative EEG analysis integrated with the Montreal Neurological Institute neuroinformatics ecosystem, producing age-corrected normative statistical parametric maps of EEG source spectra [22]. This toolbox incorporates the Variable Resolution Electrical Tomography (VARETA) method for source imaging and provides z-spectra based on normative databases, facilitating comparison of individual subjects against population norms [22]. Such standardized processing pipelines enhance reproducibility and enable multi-site collaborations in EEG research.

EEG fundamentals rest upon the neurophysiological principles of synchronized neuronal activity that generates measurable electrical potentials on the scalp surface. The technique's exceptional temporal resolution provides direct insight into neural dynamics across diverse cognitive states and pathological conditions. While limitations in spatial resolution and sensitivity to deep sources persist, ongoing methodological advances in high-density recording, source localization, and multimodal integration continue to expand EEG's research applications.

Understanding the core principles of EEG signal generation, acquisition, and analysis is essential for leveraging this technology effectively in neuroscience research and clinical applications. The integration of EEG with complementary modalities like fNIRS creates powerful frameworks for comprehensive brain investigation, bridging gaps between electrical neural activity and hemodynamic responses. As neurotechnologies evolve, EEG maintains its fundamental role as a versatile, non-invasive window into human brain function, with particular utility for studying the temporal dynamics of cognitive processes that underlie perception, cognition, and behavior.

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a non-invasive, portable neuroimaging technique that measures cerebral hemodynamic activity by detecting changes in near-infrared light absorption by brain tissue [23] [24]. First reported by Jöbsis in 1977, fNIRS leverages the relative transparency of biological tissue to light in the 700-900 nm range, known as the "optical window," to infer neural activity indirectly via neurovascular coupling [25] [23] [6]. This article provides an in-depth technical examination of fNIRS fundamentals, detailing its physical basis, instrumentation, signal processing, and experimental protocols, contextualized within the broader landscape of brain research tools like fMRI and EEG.

Core Physical Principles of fNIRS

The Optical Window and Light-Tissue Interaction

fNIRS functionality relies on the optical properties of biological tissues and chromophores. Within the near-infrared spectrum (700-900 nm), skin, skull, and brain tissue scatter light but absorb it relatively weakly, allowing light to penetrate several centimeters and reach the cerebral cortex [23] [24]. The primary absorbers in this window are oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR), which have distinct and sensitive absorption spectra [23] [6]. Light emitted onto the scalp is either absorbed by these chromophores or scattered within the tissue. A detector placed a few centimeters away measures the back-scattered light, the attenuation of which depends on the absorption properties of the underlying tissue, which in turn reflects hemoglobin concentration changes [25] [24].

The Modified Beer-Lambert Law

The conversion of measured light intensity into hemodynamic changes is primarily achieved using the Modified Beer-Lambert Law (mBLL) for continuous-wave systems, the most common fNIRS type [23] [6]. The standard Beer-Lambert law is modified to account for significant light scattering in tissue. The fundamental equation is expressed as:

OD = log10(I0/I) = ϵ · [X] · l · DPF + G [23]

Where:

- OD is the optical density (unitless)

- I0 and I are the input and detected light intensities, respectively

- ϵ is the extinction coefficient of the chromophore (HbO or HbR)

- [X] is the concentration of the chromophore

- l is the physical distance between source and detector

- DPF is the differential pathlength factor, accounting for increased photon pathlength due to scattering

- G is a geometry-dependent factor

To solve for the relative changes in HbO and HbR concentrations (Δ[HbO] and Δ[HbR]), measurements at a minimum of two wavelengths are required, forming a system of equations [23]:

| (ΔODλ1) | (ϵλ1Hbd ϵλ1HbO2d) | (Δ[X]Hb) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (ΔODλ2) | = | (ϵλ2Hbd ϵλ2HbO2d) | (Δ[X]HbO2) |

Here, d represents the total mean pathlength (l · DPF) [23]. The following diagram illustrates the complete photon migration and concentration calculation pathway.

fNIRS Instrumentation and System Types

fNIRS systems are categorized based on their light emission and detection techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The key system types are detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of fNIRS System Types

| System Type | Basic Principle | Key Measurements | Pathlength Knowledge | Relative Cost & Complexity | Primary Use/Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Wave (CW) [23] [6] | Constant intensity light source | Light attenuation (ΔOD) | Estimated (uses DPF factor) | Low cost, simple | Most common; suitable for relative concentration changes |

| Frequency-Domain (FD) [23] | Amplitude-modulated light (~100 MHz) | Attenuation, phase shift, average pathlength | Directly measured | High cost, complex | Provides absolute concentrations of HbO and HbR |

| Time-Domain (TD) [23] [24] | Short light pulses (~picoseconds) | Photon time-of-flight | Directly measured | Highest cost, most complex | High depth resolution; can separate absorption and scattering |

CW-fNIRS is the most prevalent system in research and clinical settings due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and capacity for high-channel counts [23] [6]. The subsequent workflow diagram outlines the standard data acquisition and processing pipeline for a CW-fNIRS experiment.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A Representative Experimental Protocol

A typical block-design fNIRS experiment involves participants performing a task in alternating blocks of activity and rest. The following methodology is adapted from a study investigating prefrontal cortex (PFC) activation during an auditory task with and without Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) technology [26] [27].

- Participants: 41 normal-hearing adults.

- Task: Auditory decision-making task performed in two conditions: ANC OFF and ANC ON.

- fNIRS Recording: Concentration changes of oxyhemoglobin (Δoxy-Hb) in the prefrontal cortex were measured using a multi-channel fNIRS system [26] [27].

- Additional Measures: Subjective listening effort was assessed using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Behavioral performance (accuracy and reaction time) was also collected [26].

- Procedure: The experiment consisted of multiple trials. Each trial began with a 30-second resting baseline, followed by the task period (self-paced, ~37-63 seconds), and concluded with another 30-second rest period [25] [26].

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The table below catalogs essential materials and their functions for a standard fNIRS experiment.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for fNIRS Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Instrument | A system (typically CW) with sources and detectors to emit and record light. | 32-channel CW-fNIRS system (TechEn CW6) [25]. |

| fNIRS Cap/Probe | A headgear holding sources and detectors in predetermined locations. | Cap with sources and detectors placed according to the international 10-20 system [19] [28]. |

| Short-Separation Detectors | Optional detectors placed ~8mm from a source to measure systemic physiological noise from the scalp for signal correction [23]. | Used to separate brain signal from superficial scalp hemodynamics [23]. |

| Anatomical Registration System | A 3D digitizer (e.g., FastSCAN stylus) to record the precise locations of optodes on the head for spatial mapping [25]. | Used to register fNIRS probe position on each subject's head for inter-subject data registration [25]. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Software to deliver controlled auditory, visual, or other stimuli to the participant. | Software presenting the auditory decision-making task [26]. Nintendo Wii Fit game for balance task [25]. |

| Data Processing Software | Tools for converting raw signals, filtering, and statistical analysis (e.g., HOMER3, MNE-Python, NIRS Toolbox) [29] [23]. | MNE-Python and Brainstorm software used for preprocessing optical density and converting to hemoglobin [19] [29]. |

Signal Preprocessing and Analysis

Raw fNIRS signals require extensive preprocessing to isolate the neural-related hemodynamic response. A standard pipeline, as implemented in tools like MNE-Python, includes the following steps [29]:

- Conversion to Optical Density: The raw light intensity signal is converted to optical density, which makes the signal linear with respect to changes in chromophore concentration [29].

- Quality Assessment: The Scalp Coupling Index (SCI) can be used to identify and exclude channels with poor contact between optodes and the scalp [19] [29].

- Conversion to Hemoglobin: The mBLL is applied to the optical density signals to compute relative concentration changes of HbO and HbR [29]. A common partial pathlength factor (ppf) of 0.1 is used [29].

- Filtering: A bandpass filter (e.g., 0.05 - 0.7 Hz) is applied to remove high-frequency noise (e.g., cardiac pulsation ~1 Hz) and very low-frequency drift [29].

- Epoching and Averaging: For task-based designs, the continuous data is segmented into epochs (e.g., -5 s to +15 s around stimulus onset). Epochs are then averaged across trials for each condition to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the hemodynamic response [29].

fNIRS in the Broader Neuroimaging Landscape

fNIRS occupies a unique niche among non-invasive brain imaging techniques. The table below provides a comparative overview of its position relative to fMRI and EEG.

Table 3: fNIRS Compared to Other Primary Non-Invasive Brain Imaging Modalities

| Feature | fNIRS | fMRI | EEG |

|---|---|---|---|

| What it Measures | Hemodynamic response (HbO/HbR) [6] [24] | Hemodynamic response (BOLD signal) [6] | Electrical activity from neurons [6] [28] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (seconds) [6] [28] | Very Low (seconds) [6] | Very High (milliseconds) [6] [28] |

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate (surface cortex) [6] [28] | High (whole brain) | Low [6] [28] |

| Portability | High [6] [24] | Low (requires massive scanner) | High [6] [28] |

| Tolerance to Motion | Moderate/High [6] [28] | Low | Low [6] [28] |

| Measurement Depth | Superficial cortex (1-2 cm) [25] [28] | Whole brain | Primarily cortical surface [28] |

| Best Use Cases | Naturalistic studies, child development, clinical monitoring, mobility studies [24] [28] | Deep brain structures, high-precision anatomy | Rapid cognitive processes, event-related potentials, sleep studies [6] [28] |

A significant trend is the multimodal integration of fNIRS with EEG, as the techniques are highly complementary [6] [28]. EEG provides direct, millisecond-level information on neural electrical activity, while fNIRS provides localized hemodynamic information with better spatial resolution and is less susceptible to motion artifacts [6]. This combination allows for a more comprehensive investigation of brain function and the relationship between electrical and hemodynamic activity (neurovascular coupling) [19] [6]. Integrated systems require careful synchronization of hardware and consideration of sensor placement compatibility, often using caps designed for both modalities [6] [28].

The human brain operates through two primary, interconnected physiological processes: rapid electrical neural signaling and a slower hemodynamic response that delivers energy. Modern neuroimaging techniques allow researchers to probe these processes non-invasively. Electroencephalography (EEG) directly measures electrical activity from populations of neurons, while functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) indirectly monitor neural activity by detecting associated changes in cerebral blood flow and oxygenation [6] [30]. Understanding the origins, relationships, and technical capabilities of these signals is fundamental to advancing brain research. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these modalities, detailing their neurophysiological bases, measurement principles, and methodologies for integrated use.

Fundamental Neurophysiological Signals

The Origin and Measurement of Electrical Activity

Electroencephalography (EEG) captures the electrical fields generated by the synchronous firing of large groups of cortical pyramidal neurons. These cells are orientated perpendicularly to the cortical surface, allowing their post-synaptic potentials to summate effectively and propagate to the scalp [6]. The resulting voltage differences, typically in the microvolt range, are recorded via electrodes placed on the scalp [31].

EEG signals are categorized into rhythmic patterns based on their frequency, each associated with different brain states [31]:

- Delta (δ): 0.5-4 Hz, prominent during deep sleep.

- Theta (θ): 4-7 Hz, associated with drowsiness and cognitive processing.

- Alpha (α): 8-12 Hz, the dominant rhythm during awake, relaxed states with closed eyes.

- Beta (β): 13-30 Hz, linked to active, alert states and motor behavior.

- Gamma (γ): >30 Hz, involved in higher cognitive processing and sensory integration.

Infraslow oscillations (<0.5 Hz), though not part of conventional clinical EEG, have gained research interest for their role in cognitive tasks and long-range spatial coupling in the brain [31].

The Origin and Measurement of Hemodynamic Activity

Neural activity is metabolically expensive. To meet the increased demand for oxygen and glucose, a process called neurovascular coupling occurs. This involves a localized increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) to active brain regions [6] [32]. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) leverages this principle by using near-infrared light (650-950 nm) to measure concentration changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the cortical tissue [6] [30]. The most common fNIRS systems, Continuous Wave (CW) systems, apply the Modified Beer-Lambert Law to attenuated light signals to compute these concentration changes [6] [32].

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) also measures the hemodynamic response, but it is primarily sensitive to the paramagnetic properties of deoxygenated hemoglobin. This is known as the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal. When neural activity increases, the local influx of oxygenated blood outweighs the oxygen consumption, leading to a relative decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin and an increase in the BOLD signal [11].

Table 1: Core Principles of Electrical and Hemodynamic Signals

| Feature | Electrical Activity (EEG) | Hemodynamic Response (fNIRS/fMRI) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Synchronous post-synaptic potentials of cortical pyramidal neurons [6] | Neurovascular coupling; changes in cerebral blood flow and volume [6] [32] |

| Measured Signal | Voltage fluctuations on the scalp (microvolts) [31] | fNIRS: Concentration changes of HbO and HbR [6]fMRI: Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal [11] |

| Temporal Relationship | Direct, instantaneous reflection of neural firing | Indirect, slow response lagging neural activity by 1-6 seconds [11] |

| Key Physiological Principle | Summation of ionic currents across neuronal membranes | Tight coupling between neuronal energy demand and vascular supply [6] [30] |

Technical Comparison of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

EEG, fNIRS, and fMRI offer distinct windows into brain function due to their inherent technical capabilities and limitations. EEG provides millisecond-level temporal resolution, ideal for tracking the rapid dynamics of brain networks, but suffers from limited spatial resolution and difficulty in localizing deep sources due to the inverse problem [6]. fNIRS offers a balance, with better spatial resolution than EEG for cortical regions, good tolerance to motion artifacts, and high portability. However, it is confined to the cerebral cortex and has a lower temporal resolution than EEG, constrained by the slow hemodynamic response [6] [11]. fMRI stands out with its excellent spatial resolution (millimeter-level) and whole-brain coverage, including subcortical structures. Its primary drawbacks are poor temporal resolution (limited by the hemodynamic response), high cost, immobility, and sensitivity to motion artifacts [11].

Table 2: Technical Specifications of EEG, fNIRS, and fMRI

| Characteristic | EEG | fNIRS | fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Poor (several centimeters) [6] | Moderate (1-3 cm) [11] | High (millimeter-level) [11] |

| Temporal Resolution | Excellent (milliseconds) [6] | Moderate (0.1 - 1 Hz) [6] [11] | Poor (0.3 - 2 Hz, limited by HRF) [11] |

| Penetration Depth | Whole brain (but surface-weighted) | Superficial cortex (1-3 cm) [11] | Whole brain (cortex & subcortex) [11] |

| Portability | High [6] [30] | High [30] [11] | Low (immobile scanner) [11] |

| Key Artifacts | Electrical noise (50/60 Hz), muscle activity, eye blinks [6] | Scalp blood flow, motion artifacts, hair [32] [11] | Motion, magnetic susceptibility, physiological noise (cardiac, respiratory) [11] |

| Measured Physiology | Direct neural electrical activity [6] | Hemodynamic (HbO, HbR concentration) [6] | Hemodynamic (BOLD signal) [11] |

Methodologies for Integrated Experimental Protocols

Multimodal integration leverages the strengths of each technique to provide a more comprehensive picture of brain function. The rationale is rooted in the neurovascular coupling phenomenon, where electrical events trigger metabolic and vascular responses [6] [30].

Concurrent fNIRS-EEG Recordings

This combination is highly practical due to the portability of both systems and the absence of electromagnetic interference [6] [30]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Hardware Setup: Use integrated caps that house both EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes. Ensure optode placement avoids blocking EEG electrodes and vice versa.

- Synchronization: Use a common trigger signal (e.g., TTL pulse) sent from the stimulus presentation computer to both the EEG and fNIRS acquisition systems to ensure temporal alignment of data streams.

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record EEG (raw voltage) and fNIRS (light intensity at multiple wavelengths) data throughout the experimental task.

- Data Processing and Analysis: Three primary analytical approaches are used [6]:

- EEG-informed fNIRS analysis: Use features from the fast EEG signal (e.g., event-related potentials or power in specific bands) to model or constrain the slower fNIRS hemodynamic response.

- fNIRS-informed EEG analysis: Use hemodynamic activation maps from fNIRS to guide source localization for EEG, improving spatial accuracy.

- Parallel fNIRS and EEG analysis: Analyze each modality independently and fuse the results at the interpretation stage (e.g., correlating EEG band power with HbO concentration).

Combined fMRI-fNIRS Studies

This multimodal approach is often used to validate fNIRS signals against the gold-standard spatial resolution of fMRI or to extend fMRI findings to more naturalistic settings [11]. Methodologies include:

- Synchronous Acquisition: Conducting fNIRS and fMRI simultaneously inside the MRI scanner. This requires specialized, MRI-compatible fNIRS equipment that is non-magnetic and does not interfere with the magnetic field [11].

- Asynchronous Acquisition: Performing fNIRS and fMRI sessions separately on the same subjects using identical task paradigms. This allows for the use of standard fNIRS equipment in a natural setting after localizing the region of interest with fMRI.

- Data Fusion: Co-registering fNIRS channels to the subject's anatomical MRI. The high-resolution spatial maps from fMRI can be used to interpret the fNIRS data or to create a head model for advanced fNIRS analysis, such as diffuse optical tomography (DOT) [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for Multimodal Brain Imaging Research

| Item | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Integrated EEG-fNIRS Cap | A flexible head cap with pre-configured layouts holding EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes, enabling simultaneous data acquisition [6] [30]. |

| MRI-Compatible fNIRS System | A specialized fNIRS device constructed from non-magnetic materials (e.g., fiber optics) for safe and artifact-free operation inside an MRI scanner [11]. |

| Electrode Gel (Electrolyte) | Applied at the scalp-electrode interface to reduce impedance and ensure high-quality electrical signal acquisition for EEG [31]. |

| fNIRS Optodes (Sources & Detectors) | Sources emit near-infrared light into the scalp, while detectors capture the light after it has traveled through brain tissue. The source-detector distance determines penetration depth and sensitivity [6] [30]. |

| Trigger Interface Box | A hardware device that receives event markers from a stimulus computer and sends synchronized TTL pulses to all data acquisition systems, ensuring temporal alignment of data with the experimental paradigm [6]. |

| Data Processing Pipelines (Software) | Computational tools and algorithms (e.g., for motion artifact correction, filtering, GLM analysis) are crucial for converting raw signals into interpretable neurophysiological data. Standardization is key for reproducibility [32] [33]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz, illustrate the core neurophysiological pathway and a generalized workflow for a multimodal experiment.

Neurovascular Coupling Pathway

Neurovascular Coupling Links Neural Activity to Blood Flow

Multimodal fNIRS-EEG Experimental Workflow

Concurrent fNIRS-EEG Study Design

In brain research, the selection of a neuroimaging modality is fundamentally governed by a trilemma involving spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and penetration depth. This technical guide examines how functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) navigate these inherent trade-offs, each establishing a unique position within the research ecosystem. Understanding these core principles is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select appropriate methodologies, interpret findings accurately, and design innovative experiments that leverage the strengths of each technique.

The quest to decode brain function relies on non-invasive technologies that can capture neural dynamics with varying degrees of spatial and temporal precision. While the ideal modality would offer millimeter spatial resolution, millisecond temporal resolution, and whole-brain coverage, current technological and physiological constraints make this impossible. Instead, each mainstream technique prioritizes certain dimensions at the expense of others, creating complementary profiles that can be leveraged through multimodal approaches [34] [2].

Technical Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Core Parameters

Table 1: Technical specifications of major neuroimaging modalities

| Parameter | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | High (mm to sub-mm) [34] | Low (source localization challenges) [35] | Moderate (1-3 cm) [35] [2] |

| Temporal Resolution | Moderate (0.3-2 Hz, limited by hemodynamic response) [34] | Very High (millisecond range) [35] [36] | High (0.1-10 Hz) [35] |

| Penetration Depth | Full brain (cortical & subcortical) [34] | Superficial (scalp-level signals) [36] | Superficial cortical (2-3 cm) [37] [2] |

| Primary Signal Measured | Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) [34] | Electrical potentials from neuronal firing [36] | Hemoglobin concentration changes (HbO, HbR) [38] [37] |

| Key Strength | Unparalleled spatial mapping of deep structures | Capturing rapid neural oscillations | Balance of portability, cost, and motion tolerance [35] [2] |

| Principal Limitation | Low temporal resolution, high cost, immobility | Poor spatial localization, sensitive to artifacts | Limited to cortical surfaces, cannot image subcortical areas [37] [34] |

The Fundamental Trade-off Relationships

The quantitative specifications in Table 1 reveal the fundamental constraints of neuroimaging. The relationship between these core parameters can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: The core trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and penetration depth in neuroimaging, with modality positioning.

Modality-Specific Technical Principles and Methodologies

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

fMRI operates by detecting the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal, which exploits the different magnetic properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin. When neurons fire, they consume oxygen, triggering a complex hemodynamic response that ultimately delivers oxygenated blood in excess of demand. This changes the local ratio of oxygenated to deoxygenated hemoglobin, which in turn alters the magnetic properties of the tissue that fMRI can detect [34] [2]. This process typically lags behind neural activity by 4-6 seconds, fundamentally limiting the technique's temporal resolution [34].

Experimental Protocol: Typical fMRI Block Design

- Participant Preparation: Screen for metal implants; ensure compliance with MRI safety protocols.

- Stimulus Presentation: Use specialized MRI-compatible displays and response systems.

- Data Acquisition: Employ a series of alternating task and rest blocks (e.g., 30-second task blocks interspersed with 30-second rest blocks).

- Data Analysis: Preprocess data (motion correction, normalization), then perform statistical parametric mapping (e.g., SPM, FSL) to identify voxels with significant BOLD signal changes between conditions [34].

Electroencephalography (EEG)

EEG measures the electrical potentials generated by the summed postsynaptic activity of large, synchronously firing populations of pyramidal neurons in the cortex. These minute electrical signals are detected by electrodes placed on the scalp, amplified, and digitized. While EEG provides unparalleled temporal resolution for capturing neural oscillations, its spatial resolution is limited by the blurring effects of the skull and other tissues, as well as the challenge of solving the inverse problem to localize source activity [36].

Experimental Protocol: EEG for Attention State Classification

- System Setup: Apply a multi-channel EEG cap according to the 10-20 system; ensure impedances are below 5-10 kΩ.

- Paradigm Design: Implement a sustained attention task (e.g., oddball, continuous performance task) with randomized stimuli.

- Data Recording: Collect continuous EEG data at a high sampling rate (e.g., 500-1000 Hz).

- Feature Extraction: Segment data into epochs; extract features from time, frequency, and connectivity domains (e.g., power spectral density, phase-locking value, functional connectivity).

- Classification: Apply machine learning models (e.g., SVM) to classify mental attention states based on the extracted features [36].

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

fNIRS leverages the relative transparency of biological tissues to near-infrared light (650-950 nm). Within this "optical window," light can penetrate the scalp and skull to reach the cerebral cortex. fNIRS measures changes in the concentration of oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) by exploiting their distinct absorption spectra, typically using the modified Beer-Lambert law [37] [35]. The path of the light between source and detector is typically "banana-shaped," sampling a volume of cortical tissue [37].

Experimental Protocol: fNIRS with Riemannian Geometry Classification

- Optode Placement: Position sources and detectors over the region of interest (e.g., prefrontal cortex) with a 3-cm separation for adults.

- Signal Acquisition: Record changes in HbO and HbR concentrations at a sampling rate of ~10 Hz during cognitive tasks (e.g., motor imagery, verbal fluency).

- Covariance Matrix Estimation: Construct channel-wise kernel matrices that capture the spatial and temporal relationships between fNIRS signals, separately for HbO and HbR.

- Riemannian Classification: Apply classifiers such as the Riemannian Support Vector Machine or Tangent Space Logistic Regression to differentiate brain states based on the geometry of these covariance matrices in the manifold space [38].

Multimodal Integration: Overcoming Individual Limitations

Synergistic Approaches