fMRI vs. EEG vs. fNIRS: A Comprehensive Neuroimaging Comparison for Design Neurocognition Research

This article provides a systematic comparison of three pivotal neuroimaging techniques—functional magnetic resonance imaging (fNIRS), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)—for researchers and professionals in design neurocognition and drug...

fMRI vs. EEG vs. fNIRS: A Comprehensive Neuroimaging Comparison for Design Neurocognition Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of three pivotal neuroimaging techniques—functional magnetic resonance imaging (fNIRS), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)—for researchers and professionals in design neurocognition and drug development. It explores the foundational principles, measuring electrical activity with EEG and hemodynamic responses with fMRI and fNIRS, and delves into their specific methodological applications in studying cognitive processes relevant to design. The review addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, including cost, portability, and motion artifact tolerance, and offers a direct, evidence-based validation of their spatial and temporal resolution, data quality, and suitability for naturalistic study environments. By synthesizing these dimensions, the article serves as a guide for selecting the optimal modality or multimodal combination to advance research in cognitive neuroscience and clinical translation.

Understanding the Core Principles: What fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS Measure in the Brain

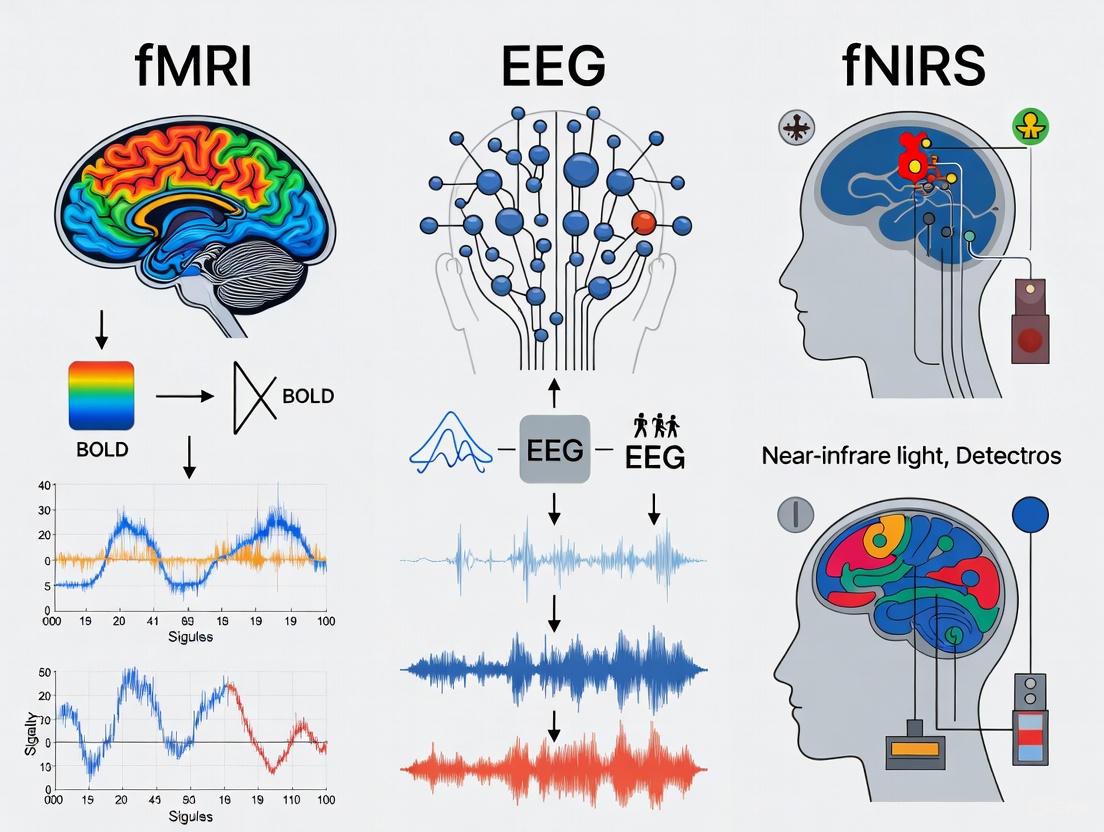

Understanding brain function requires tools that can capture its rapid electrical activity and the slower, metabolic processes that support it. Electrical signals, measured by techniques like electroencephalography (EEG), provide a direct, millisecond-scale view of neural firing. In contrast, hemodynamic signals, measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), reflect indirect, metabolic correlates of brain activity through changes in blood oxygenation and flow [1]. This fundamental difference—direct neural activity versus metabolic proxies—defines the capabilities and limitations of each class of imaging technology. For researchers in neurocognition and drug development, selecting the appropriate tool is paramount. This guide provides a structured, evidence-based comparison of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS to inform your experimental design, framed within the broader context of investigating the brain's structure-function relationships [2].

Fundamental Differences in Signal Origin and Physiology

The core distinction between these signals lies in their physiological origins and the principles of neurovascular coupling.

Electrical Signals: The Direct Measure of Neural Activity

EEG captures the electrical potentials generated by the synchronized activity of large groups of neurons, primarily the postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal cells aligned perpendicular to the scalp [1]. This signal is a direct correlate of neural firing, offering an unmediated view of brain communication and computation.

Hemodynamic Signals: The Metabolic Correlates

Hemodynamic signals are an indirect measure of neural activity, reliant on neurovascular coupling—the process by which neural activity triggers changes in local blood flow and oxygenation [3] [4]. Techniques like fMRI and fNIRS measure these hemodynamic changes. fMRI typically detects the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal, which reflects the balance of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin [5]. fNIRS directly measures concentration changes in both oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) using near-infrared light [3] [1]. The hemodynamic response lags behind the initiating neural activity by 2 to 6 seconds, representing a slow, metabolic consequence of neuronal firing rather than the firing itself [5] [1].

The diagram below illustrates this fundamental relationship and measurement approach.

Technical Specifications and Performance Comparison

The physiological differences between electrical and hemodynamic signals directly translate into distinct performance profiles for the neuroimaging modalities that measure them. The table below provides a quantitative and qualitative comparison of fMRI, fNIRS, and EEG.

Table 1: Technical Specification and Performance Comparison of fMRI, fNIRS, and EEG

| Feature | fMRI | fNIRS | EEG |

|---|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Blood-Oxygen-Level Dependent (BOLD) signal [5] | Concentration changes in HbO and HbR [3] [1] | Electrical potentials from cortical neurons [1] |

| Signal Source | Hemodynamic response (indirect) [5] | Hemodynamic response (indirect) [1] | Postsynaptic potentials (direct) [1] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (0.33 - 2 Hz, ~seconds) [5] | Low (~0.1 - 10 Hz, ~seconds) [5] [2] | Very High (milliseconds) [1] |

| Spatial Resolution | High (millimeter-level) [5] | Moderate (centimeter-level) [5] [1] | Low (centimeter-level) [1] |

| Depth of Measurement | Whole brain (cortical & subcortical) [5] | Superficial cortex (1-2.5 cm) [5] [1] | Cortical surface [1] |

| Portability | Low (immobile scanner) [5] | High (wearable systems) [5] [1] | High (wearable systems) [1] |

| Tolerance to Motion Artifacts | Low [5] | Moderate/High [1] | Low [1] |

| Best Use Cases | Spatial localization of deep brain activity, network connectivity [5] | Naturalistic studies, child development, bedside monitoring [5] [1] | Fast cognitive tasks, ERPs, sleep studies, brain-state monitoring [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Robust experimental design is crucial for valid data interpretation. Below are detailed methodologies from key studies that have successfully employed these modalities, either individually or in a multimodal setup.

A Unimodal fNIRS-EEG Protocol: Visual Evoked Responses

A study investigating the correlation between electrical and hemodynamic responses during visual stimulation provides a clear protocol for parallel measurement [3].

- Participants & Stimuli: Thirteen healthy volunteers viewed full-field windmill checkerboard patterns reversing at 4 Hz. The stimulus contrast was graded (100%, 10%, 1%) to probe different levels of neural response [3].

- Protocol Design: The session began with a 30-second baseline, followed by seven blocks. Each block consisted of a 25-second stimulation period and a 30-second rest period. The order of contrasts was randomized [3].

- EEG Data Acquisition & Analysis: VEPs were recorded using a 64-channel system. Data processing involved down-sampling to 1000 Hz, band-pass filtering (1-100 Hz), ocular correction via ICA, and segmentation into epochs from -50 ms to +200 ms around stimulus onset. Epochs with artifacts (> ±50 µV) were rejected before averaging [3].

- fNIRS Data Acquisition & Analysis: Hemodynamic responses were recorded with a system placing optodes over the visual cortex. Data was converted to HbO and HbR concentrations using the modified Beer-Lambert Law and then band-pass filtered (0.01-0.1 Hz) to remove physiological noise [3].

A Multimodal Protocol: Motor Execution, Observation, and Imagery

A 2023 study showcases a sophisticated simultaneous fNIRS-EEG protocol to investigate shared neural networks, highlighting the power of multimodal integration [6].

- Participants & Paradigm: Sixty healthy adults participated in a live-action paradigm involving Motor Execution (ME), Motor Observation (MO), and Motor Imagery (MI) of a cup-moving task, while being seated face-to-face with an experimenter [6].

- Simultaneous Recording: A 24-channel fNIRS system (Hitachi ETG-4100) was embedded within a 128-electrode EEG cap (Electrical Geodesics, Inc.). The fNIRS probe was placed over sensorimotor and parietal cortices. Optode positions were digitized for precise co-registration [6].

- Data Fusion Analysis: The study employed a advanced analysis technique called structured sparse multiset Canonical Correlation Analysis (ssmCCA). This method fuses the electrical (EEG) and hemodynamic (fNIRS) data to pinpoint brain regions consistently identified by both modalities, thereby providing a more robust picture of neural activity [6].

The workflow for such a multimodal experiment is complex and requires careful synchronization, as shown below.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for a Multimodal fNIRS-EEG Study

| Item Category | Specific Tool/Software | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Integrated fNIRS-EEG Cap [6] [7] | Ensures precise and stable co-registration of fNIRS optodes and EEG electrodes on the scalp. |

| Synchronization System | TTL Pulses / Shared Clock [1] | Aligns the data streams from both modalities to a common timeline for fused analysis. |

| Data Acquisition | Brain Vision Recorder (EEG) [3], TechEn CW6 (fNIRS) [3], Hitachi ETG-4100 (fNIRS) [6] | Software and hardware to record raw, high-fidelity electrical and optical signals. |

| Preprocessing & Analysis | Brain Vision Analyzer (EEG) [3], HOMER2 (fNIRS) [3], MNE-Python [2], ssmCCA [6] | Software toolkits for modality-specific preprocessing (filtering, artifact removal) and advanced multimodal data fusion. |

Complementary Nature and Multimodal Integration

The discrepancies often observed between EEG and fNIRS/fMRI findings are not necessarily errors but reflections of the brain's complex, multi-faceted activity [6]. EEG captures rapid, synchronized electrical oscillations, while fNIRS/fMRI reveals the slower, metabolically demanding hemodynamic processes they drive [4] [2]. Multimodal integration leverages these differences to create a more complete picture.

- Validation and Spatial Refinement: Simultaneous EEG-fMRI has been used to validate fNIRS signals, leveraging fMRI's high spatial resolution to confirm the cortical origins of fNIRS-measured hemodynamics [5].

- Uncovering Complex Brain Dynamics: A 2025 sleep study using simultaneous EEG-PET-MRI demonstrated tightly coupled temporal progression of global electrophysiology, hemodynamics, and metabolism, revealing how these processes interact across different brain states [8].

- Enhanced Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs): Combining EEG's rapid response with fNIRS's superior spatial localization has been shown to improve the classification accuracy of brain states in real-time systems [3] [7].

The choice between electrical (EEG) and hemodynamic (fMRI, fNIRS) neuroimaging technologies is not a matter of selecting a superior tool, but of aligning the tool's strengths with the research question. EEG is unparalleled for capturing the high-speed dynamics of neural communication, making it ideal for studying sensory processing, rapid cognitive tasks, and brain states. fMRI provides unparalleled spatial resolution for deep brain structures and network mapping in highly controlled environments. fNIRS offers a powerful balance, providing localized hemodynamic information with the portability necessary for naturalistic studies involving movement, children, or clinical populations.

For the most comprehensive investigations into brain function—particularly in applied neurocognition and drug development research—a multimodal approach that integrates EEG with fNIRS or fMRI is increasingly becoming the gold standard. This strategy successfully bridges the temporal and spatial resolution gap, allowing researchers to delineate both the direct neural activity and its metabolic correlates, and ultimately uncover the principles of brain organization and its alteration in disease states [2].

Electroencephalography (EEG) stands as a cornerstone non-invasive technique for studying human brain function, offering unparalleled temporal resolution to capture neural dynamics on a millisecond scale. The biophysical basis of EEG originates from the electrical activity of populations of cortical neurons, primarily the post-synaptic potentials of pyramidal cells aligned perpendicular to the scalp [1]. When these neurons fire synchronously, their summed electrical currents generate potentials measurable at the scalp surface, creating the oscillatory patterns that characterize EEG recordings.

Understanding what EEG measures—and what it cannot measure—is crucial for interpreting its signals accurately. Computational biophysical modeling has demonstrated that action potentials contribute negligibly to the broadband spectral trend of scalp EEG, which is instead dominated by synaptic currents and their filtering properties [9]. This fundamental understanding of EEG's neural origins provides the foundation for its application in cognitive neuroscience, clinical diagnosis, and the emerging field of design neurocognition, where it complements other neuroimaging modalities with its unique strengths.

Fundamental Principles and Neural Generators

Biophysical Mechanisms of EEG Signal Generation

The electrical signals measured by EEG emerge from the coordinated activity of millions of neurons, with particular emphasis on pyramidal cells in the cerebral cortex. These neurons possess a distinct spatial orientation perpendicular to the cortical surface, allowing their synchronized post-synaptic potentials to summate effectively rather than cancel each other out. When excitatory neurotransmitters bind to post-synaptic receptors, they open ion channels that create current sinks, while inhibitory inputs create current sources. This spatial separation of currents generates a dipole field that propagates through various tissues—including cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp—before being detected by electrodes on the scalp surface [1].

The transmission of these electrical signals through different biological tissues is governed by their conductive properties, with the skull presenting particularly high electrical resistance compared to other tissues. This journey through resistive media significantly attenuates the signal and blurs its spatial origin, explaining EEG's limited spatial resolution. The amplitude of scalp-recorded EEG typically ranges from 10 to 100 microvolts, representing a heavily attenuated version of the original cortical currents, which may be stronger by orders of magnitude at their source.

Action Potentials vs. Synaptic Activity in EEG Generation

A critical distinction in understanding EEG's biophysical basis lies in differentiating the contributions of action potentials versus synaptic activity to the recorded signal. Detailed biophysical simulations have revealed that action potentials generally contribute negligibly to the EEG spectral trend, with the signal instead being dominated by synaptic currents and their filtering properties [9]. This occurs because action potentials are typically too brief and poorly synchronized to generate significant summation at the scalp, whereas synaptic potentials last longer and involve larger dendritic areas, facilitating spatial summation.

However, under specific conditions of high neuronal synchrony, action potentials can generate detectable narrowband power in the high-frequency range (approximately 60-1000 Hz) [9]. This explains why certain high-frequency oscillations can occasionally be observed in EEG recordings, though the majority of the unprocessed EEG signal above 30 Hz reflects muscle activity rather than neural sources [9]. The predominant contribution of synaptic activity to EEG signals validates the technique's sensitivity to integrated network inputs rather than output spiking activity, shaping how researchers interpret EEG findings in relation to underlying neural computation.

Technical Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities

EEG Versus fNIRS and fMRI: Core Technical Differences

Understanding EEG's capabilities requires direct comparison with other prominent neuroimaging techniques, particularly functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Each method captures distinct physiological phenomena with unique spatiotemporal characteristics, making them complementary rather than redundant for comprehensive brain imaging.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Technical Specifications for Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Feature | EEG | fNIRS | fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| What it Measures | Electrical activity from synchronized neuronal firing | Hemodynamic response (blood oxygenation) | Blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal |

| Signal Source | Post-synaptic potentials in cortical pyramidal neurons | Changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin | Magnetic susceptibility of deoxygenated hemoglobin |

| Temporal Resolution | High (milliseconds) | Low (seconds) | Low (seconds) |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (centimeter-level) | Moderate (better than EEG) | High (millimeter-level) |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface | Outer cortex (~1-2.5 cm deep) | Whole brain (cortical and subcortical) |

| Portability | High (wearable systems available) | High | Low (requires fixed scanner) |

| Tolerance to Motion | Low (susceptible to artifacts) | High | Low |

| Best Use Cases | Fast cognitive tasks, ERPs, sleep studies | Naturalistic studies, child development, rehabilitation | Precise spatial localization, deep brain structures |

EEG's paramount advantage lies in its exceptional temporal resolution, capturing neural dynamics at the millisecond scale essential for analyzing rapid cognitive processes like sensory perception, attention, and motor planning [1]. This temporal precision enables researchers to track the rapid sequence of information processing through different neural systems with timing accuracy unmatched by hemodynamic-based methods. However, this strength comes at the cost of spatial resolution, as electrical signals become blurred and attenuated while passing through the skull and scalp [1].

In contrast, fMRI provides excellent spatial resolution (millimeter-level) for localizing brain activity throughout both cortical and subcortical structures, but suffers from limited temporal resolution due to the slow hemodynamic response (typically lagging 4-6 seconds behind neural activity) [10]. fNIRS occupies a middle ground, offering better spatial resolution than EEG for surface cortical areas while maintaining greater tolerance for movement and more naturalistic testing environments than fMRI [1] [11].

Quantitative Experimental Comparisons

Direct comparisons between these modalities reveal their complementary nature. Simultaneous fMRI-EEG recordings have demonstrated a linear relationship between spatial increases in the BOLD signal and increased regional neural activity measured by EEG [11]. However, these signals originate from different physiological processes—EEG measures direct electrical activity while fMRI reflects the metabolic consequences of neural activity through neurovascular coupling.

Similarly, combined fNIRS-EEG studies show that while fNIRS offers better spatial localization for surface cortical areas, EEG provides superior temporal resolution for capturing rapid neural dynamics [1] [12]. The integration of both techniques creates a powerful hybrid approach that compensates for their individual limitations, providing both spatial and temporal information in a single experimental setup [1].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

| Experimental Aspect | EEG Protocols | fNIRS Protocols | fMRI Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Setup Time | 20-45 minutes (including electrode application) | 10-20 minutes | 30-60 minutes |

| Subject Preparation | Electrode application with conductive gel/gel, scalp abrasion often needed | Optode placement with minimal skin preparation | No direct physical preparation but safety screening |

| Typical Sampling Rate | 250-2000 Hz | 1-100 Hz | 0.3-2 Hz (BOLD signal) |

| Primary Signal Processing | Filtering (0.1-100 Hz), artifact removal, independent component analysis | Filtering, motion correction, conversion to hemoglobin concentrations | Slice timing correction, motion correction, spatial normalization |

| Key Artifacts | Ocular movements, muscle activity, line noise | Scalp blood flow, motion, hair interference | Motion, magnetic susceptibility, physiological noise |

| Environment Constraints | Electrically shielded room preferred but not always required | Controlled lighting preferred | Strict magnetic field control required |

Methodological Approaches in EEG Research

Advanced Signal Processing Techniques

Extracting meaningful neural information from EEG signals requires sophisticated processing approaches to overcome the technique's limitations regarding spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. Spatial filtering methods represent some of the most powerful tools in this domain, with constrained independent component analysis (cICA) demonstrating particular efficacy for detecting movement-related cortical potentials (MRCPs) during motor execution and imagery tasks [13].

In one detailed study comparing spatial filters for MRCP detection, cICA achieved significantly lower latencies (-34 ± 29 ms for motor execution and 28 ± 16 ms for motor imagery) and higher true positive rates (87.11 ± 11.73 for motor execution and 86.66 ± 6.96 for motor imagery) compared to other methods like Common Spatial Pattern and Laplacian filtering [13]. The experimental protocol for this investigation involved:

- Participants: 24 healthy adults (7 female, 17 male, 27 ± 4 years)

- Task: Ankle dorsiflexion (actual and imagined) with visual cues

- EEG Recording: 10 electrodes at standard 10-20 positions, 500 Hz sampling rate

- Data Processing: Non-causal bandpass filtering (0.05-3 Hz) using zero-phase second-order Butterworth filter

- Analysis: cICA extraction of desired sources using reference signals without manual intervention

This methodological approach demonstrates how advanced signal processing can enhance EEG's utility for detecting specific neural patterns, even those with relatively low signal-to-noise characteristics like MRCPs.

Experimental Considerations for Design Neurocognition

In design neurocognition research, EEG paradigms have successfully differentiated cognitive processes relevant to design thinking. Studies have shown that higher alpha-band activity over temporal and occipital regions distinguishes between open-ended versus close-ended problem descriptions during design problem-solving in expert designers [14]. Similarly, EEG components have served as reliable indicators of effort, fatigue, and concentration during conceptual design tasks [14].

The experimental setup for design neurocognition studies typically involves:

- Task Design: Ecologically valid design problems presented visually or verbally

- Recording Parameters: Dense-array EEG systems (64-128 channels) for improved spatial sampling

- Protocol: Mixed design incorporating both structured tasks and open-ended design challenges

- Complementary Data: Video recording, protocol analysis, and behavioral metrics synchronized with EEG

- Analysis Focus: Event-related potentials, time-frequency decomposition, and functional connectivity

These methodologies enable researchers to capture the temporal dynamics of design thinking, revealing how different cognitive processes unfold over millisecond to minute timescales during complex design activities.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Equipment and Analytical Tools for EEG Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Systems | High-density EEG caps (64-256 channels), wearable EEG systems | Signal acquisition with varying spatial resolution and mobility |

| Amplifiers | Biosemi ActiveTwo, BrainAmp, Neuroscan NuAmps | Signal amplification and digitization with high dynamic range |

| Electrodes | Ag/AgCl electrodes, sintered silver ring electrodes, active electrodes | Signal transduction with optimized skin contact and stability |

| Conductive Media | Electrolyte gels, saline solutions, electrode pastes | Maintaining stable electrical contact between scalp and electrodes |

| Stimulation Equipment | Visual and auditory stimulators, response pads | Presenting experimental paradigms and collecting behavioral data |

| Analysis Software | EEGLAB, FieldTrip, Brainstorm, MNE-Python | Signal processing, artifact removal, and statistical analysis |

| Spatial Filtering Algorithms | Constrained ICA, Common Spatial Patterns, Laplacian filters | Enhancing signal-to-noise ratio and source separation |

Visualization of EEG Signal Generation and Processing

The following diagram illustrates the biophysical basis of EEG signal generation and the subsequent processing pipeline:

Integrated Applications in Design Neurocognition

The emerging field of design neurocognition leverages multiple neuroimaging techniques to understand the neural basis of design thinking, with EEG playing a crucial role in capturing its temporal dynamics. Studies have demonstrated that EEG patterns can distinguish between different cognitive processes in design, differentiate expert designers based on their specialization, and track changes in cognitive states during extended design sessions [14].

The combination of EEG with fNIRS is particularly promising for design neurocognition research, as it enables researchers to capture both the rapid temporal dynamics of design cognition (via EEG) and the localized cortical activation patterns (via fNIRS) during ecologically valid design tasks [14]. This multimodal approach overcomes the limitations of individual techniques, providing a more comprehensive picture of how the brain supports complex design thinking in real-world contexts.

Future methodological advances in EEG technology, including improved artifact removal algorithms, more sophisticated source localization techniques, and enhanced integration with other neuroimaging modalities, will further strengthen its utility for design neurocognition research. These developments will enable more detailed investigations into the neural processes underlying creativity, problem-solving, and innovation—ultimately contributing to improved design education and practice.

EEG provides cognitive neuroscientists with a powerful tool for capturing millisecond-scale electrical potentials generated primarily by synchronized post-synaptic activity in cortical pyramidal cells. While limited in spatial resolution, its exceptional temporal resolution makes it ideally suited for studying the rapid neural dynamics underlying design thinking and other higher cognitive functions. When combined with complementary techniques like fNIRS and fMRI in multimodal frameworks, EEG enables researchers to overcome the limitations of individual modalities, providing both temporal and spatial information about brain function. This integrated approach holds particular promise for advancing design neurocognition research, offering new insights into the neural basis of design thinking while providing a foundation for enhancing design education and practice through neuroscience-informed approaches.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), particularly through the Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast, has revolutionized non-invasive brain mapping by allowing researchers to visualize neural activity with exceptional spatial detail. The physical principles of MRI are based on nuclear magnetic resonance theory, where hydrogen protons in a magnetic field align and process at frequencies proportional to field strength when exposed to radiofrequency pulses [15]. This technical foundation enables fMRI to detect subtle hemodynamic changes associated with brain activity, making it a cornerstone of modern cognitive neuroscience. While fMRI provides excellent spatial resolution, other prominent techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) offer complementary strengths in temporal resolution and practical applicability.

The BOLD signal specifically originates from magnetic susceptibility differences between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood [15]. Deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic and creates magnetic field inhomogeneities that reduce MR signal intensity, while oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic and increases signal intensity [15]. When neural activity increases in a brain region, the resultant metabolic demands trigger a complex hemodynamic response where blood flow delivery exceeds oxygen consumption, leading to a net decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin and a corresponding increase in the BOLD signal [15]. This neurovascular coupling forms the fundamental basis of BOLD fMRI and enables the high-resolution mapping of brain function, though it inherently limits temporal resolution due to the slow hemodynamic response.

Technical Comparison of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

Table 1: Technical specifications and performance characteristics of major neuroimaging modalities

| Specification | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 0.3 mm voxels (ultra-high field) [16] to 2-3 mm (standard) [17] | 5-9 cm [18] | 2-3 cm [18] |

| Temporal Resolution | 0.33-2 Hz (limited by hemodynamic response) [10] | >1000 Hz [18] | ≤10 Hz [18] |

| Penetration Depth | Whole head, including subcortical structures [10] | Brain cortex (EEG), deep structures (MEG) [18] | Superficial cortex only (limited by light penetration) [10] |

| Portability | None (requires fixed scanner) [18] | Yes (portable systems available) [18] | Yes (portable systems available) [18] |

| Cost | High [18] | Low (EEG), High (MEG) [18] | Low [18] |

| Tolerance to Motion | Limited [15] | Limited [18] | Very good [18] |

| Primary Signal Source | Hemodynamic (BOLD contrast) [15] | Electrical activity (postsynaptic potentials) [2] | Hemodynamic (HbO/HbR concentration changes) [15] |

Each modality offers distinct advantages depending on research requirements. fMRI provides unparalleled spatial resolution for deep brain structures, with ultra-high field systems (7T and above) enabling sub-millimeter resolution suitable for cortical layer analysis [19] [16]. EEG captures neural electrical activity directly with millisecond temporal precision, ideal for tracking rapid neural dynamics [18]. fNIRS represents a middle ground, measuring hemodynamic responses like fMRI but with better motion tolerance and portability, though limited to superficial cortical regions [15] [10].

Table 2: Functional characteristics and optimal applications for each neuroimaging modality

| Characteristic | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strengths | High spatial resolution, whole-brain coverage, detailed localization [15] | Excellent temporal resolution, direct neural activity measurement, low cost [18] | Good motion tolerance, portable, silent operation [15] [18] |

| Key Limitations | Expensive, sensitive to motion, noisy environment, limited temporal resolution [15] | Poor spatial resolution, sensitive to artifacts, limited to cortical surface for EEG [18] | Limited to superficial cortex, lower spatial resolution than fMRI [10] |

| Optimal Research Applications | High-precision spatial mapping, subcortical studies, layer-specific fMRI [19] [16] | Temporal dynamics, cognitive processing speed, clinical monitoring [18] [2] | Naturalistic settings, pediatric populations, rehabilitation studies [15] [10] |

| Hemodynamic Specificity | High (BOLD signal with vascular contributions) [16] | None (measures electrical activity) | High (direct HbO/HbR measurement) [15] |

High-Resolution fMRI: Technical Considerations and Methodological Advances

Ultra-High Field fMRI and Cortical Layer Imaging

Pushing fMRI to its spatial resolution limits requires addressing numerous technical challenges, particularly at ultra-high magnetic field strengths (7T and above). At 9.4T, researchers face significant obstacles including B1+ and B0 inhomogeneities that limit efficient blood tagging, specific absorption rate (SAR) constraints that restrict RF pulse application, short T2* values that necessitate brief readout durations, and long T1 values that can cause blood-inflow contaminations [19]. These challenges become particularly pronounced when attempting layer-dependent fMRI, which aims to resolve activity across cortical layers with thicknesses typically between 0.2 mm and 1 mm [19].

Advanced methodological approaches have been developed to overcome these limitations. These include temporally alternating pTx B1+ shimming parameters to address B1+ inhomogeneities, advanced adiabatic RF pulses to improve inversion efficiency within SAR constraints, 3D-EPI signal readout to accommodate short T2* values at 9.4T, optimized GRAPPA acquisition and reconstruction for accelerated imaging, and stability-optimized RF channel combination schemes [19]. The motor cortex has served as an important model system for developing high-resolution fMRI due to its consistent folding pattern, susceptibility to blood inflow effects, and unique double-layer structure of input and output layers [19].

Cerebral Blood Volume fMRI as a High-Specificity Alternative

While BOLD fMRI is widely used, its specificity is compromised by venous drainage effects, where activated signals can be detected in draining veins distant from the actual neural activity site [19]. Cerebral Blood Volume (CBV) imaging using Vascular Space Occupancy (VASO) techniques provides higher localization specificity for mapping cortical layers and columns [19]. VASO measures CBV changes through selective detection of signal changes in the extravascular compartment while nulling the intravascular blood compartment using inversion recovery timing based on T1 differences between blood and tissue [19].

The combination of CBV-fMRI with ultra-high field systems creates a powerful tool for investigating human cortical microcircuitry, potentially bridging gaps between preclinical animal research and clinical psychology [19]. This approach is particularly valuable for testing theories of psychiatric and neurological diseases as disorders of neural circuits [19]. However, VASO methods face their own challenges, including higher noise levels and lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) compared to BOLD, especially at ultra-high spatial resolutions [19].

Experimental Protocols for High-Resolution Neuroimaging

Layer-Dependent fMRI Protocol for Motor Cortex Mapping

A representative protocol for layer-dependent CBV-fMRI investigation of the motor cortex at 9.4T involves several critical components [19]:

Participant Preparation and Setup: Participants are scanned using a head gradient set in combination with a 16-channel parallel transmit system and a dual-row 31-channel receive array coil. Online local SAR monitoring is essential for safety compliance.

Functional Task Design: A unilateral finger tapping task (thumb and index finger) is implemented in a block design. Blocks of 80 seconds (40s rest and 40s paced tapping at 0.75Hz) are repeated 12 times, resulting in 16-minute acquisitions. During the task, participants watch a video of a moving hand and mimic the tapping movement.

MR Sequence Parameters: The protocol employs SS-SI VASO with 3D-EPI readout, optimized for 9.4T specific challenges. Key parameters include customized inversion pulses for blood-nulling, accelerated GRAPPA acquisition, and stability-optimized RF channel combination.

Data Analysis: Cortical layer segmentation is performed based on high-resolution anatomical images, with functional data analyzed for layer-specific activation profiles.

Hybrid EEG-fNIRS Protocol for Mental Workload Classification

Multimodal approaches combining EEG and fNIRS have been developed for mental workload classification [18]:

Experimental Paradigm: Participants perform n-back working memory tasks (0-back, 2-back, and 3-back) with randomized presentation. Each task begins with a 2s instruction period, followed by 40s task period (20 trials), 1s stop period, and 20s rest period.

Data Acquisition: Simultaneous recording from 30 EEG electrodes (placed according to international 10-5 system) at 1000Hz sampling rate and 36 fNIRS channels (14 sources and 16 detectors with 30mm inter-optode distance) at 12.5Hz sampling rate using two wavelengths (760nm and 850nm).

Signal Preprocessing:

- fNIRS: Optical density transformation, bandpass filtering (0-0.04Hz), baseline correction, and sensitivity analysis to determine optimal time window (typically 5s).

- EEG: Resampling to 200Hz, improved Weight-Adjusted Second-Order Blind Identification (iWASOBI) for artifact removal.

Feature Extraction:

- fNIRS: Mean, variance, slope, skewness, and kurtosis of HbO and HbR concentrations.

- EEG: Power spectral density in delta (0.5-4Hz), theta (4-7Hz), and alpha (8-15Hz) bands, plus functional brain connectivity features in time and frequency domains.

Classification: Implementation of Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) classifiers with Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) algorithm for dimensionality reduction, achieving accuracy improvements from 69% to 84.19% for LDA with CSP [18] [20].

Signaling Pathways and Neurovascular Coupling

The relationship between neural activity, metabolic demand, and hemodynamic response forms the foundation of BOLD fMRI. The neurovascular coupling process involves complex signaling pathways between neurons, astrocytes, and vascular components.

Diagram 1: Neurovascular coupling pathway linking neural activity to BOLD signal changes.

The BOLD signal does not directly measure neural activity but reflects the hemodynamic response triggered by neural metabolic demands. When neurons become active, they release glutamate, triggering calcium influx in postsynaptic neurons and astrocytes [16]. This leads to the production of vasoactive signaling molecules including nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and arachidonic acid metabolites that cause vasodilation of arterioles [16]. The resultant cerebral blood flow (CBF) increase delivers oxygenated blood, with the inflow typically exceeding oxygen consumption, leading to a net decrease in deoxyhemoglobin concentration [15] [16]. This increase in HbO relative to HbR reduces the paramagnetic effects of deoxyhemoglobin, thereby increasing the BOLD signal detected in fMRI [15].

Integrated Experimental Workflow for Multimodal Neuroimaging

Combining multiple neuroimaging modalities requires careful experimental design and data integration strategies. The following workflow illustrates a typical multimodal approach:

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for simultaneous multimodal neuroimaging studies.

The integrated approach begins with comprehensive study design that defines the research questions and determines which modalities provide complementary information [10]. Participant preparation involves positioning and securing various sensors - EEG electrodes, fNIRS optodes, and ensuring participant comfort within the MRI environment [10]. Simultaneous data acquisition requires careful synchronization of timing signals across all modalities to enable later data fusion [10]. Modality-specific preprocessing addresses the unique artifacts and noise sources for each technique - correcting geometric distortions and physiological noise in fMRI, removing motion artifacts and systemic components in fNIRS, and filtering line noise and muscle artifacts in EEG [18]. Feature extraction identifies relevant signal characteristics, such as BOLD amplitude changes, HbO/HbR concentration variations, or spectral power in specific frequency bands [18]. Data fusion integrates these features using various approaches, from simple concatenation to advanced machine learning methods that weight contributions according to signal quality and relevance to the research question [10]. Finally, multimodal analysis extracts insights that would be inaccessible to any single modality alone [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential equipment and computational tools for advanced neuroimaging research

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Hardware | Ultra-High Field MRI Scanner | 7T-9.4T with high-performance gradients [19] | High-resolution BOLD and CBV fMRI, cortical layer imaging [19] |

| Multi-channel RF Coils | 16-channel transmit/31-channel receive arrays [19] | Improved SNR and parallel imaging capabilities [19] | |

| fNIRS Systems | Portable systems with 760nm and 850nm wavelengths [18] | Naturalistic studies, bedside monitoring, pediatric populations [15] | |

| EEG Systems | High-density caps (30+ channels) with compatible amplifiers [18] | Temporal dynamics of neural processing, brain connectivity [2] | |

| Pulse Sequences | 3D-EPI | Volumetric echo-planar imaging for high spatial resolution [19] | Reduced distortion in high-resolution fMRI [19] |

| SS-SI VASO | Slice-selective inversion vascular space occupancy [19] | Cerebral blood volume mapping with high specificity [19] | |

| ASL (Arterial Spin Labeling) | Magnetic labeling of arterial blood for perfusion imaging [16] | Quantitative cerebral blood flow measurement [16] | |

| Computational Tools | GRAPPA Reconstruction | GeneRalized Autocalibrating Partial Parallel Acquisition [19] | Accelerated image acquisition with improved SNR [19] |

| PCA Denoising | Principal Component Analysis for physiological noise removal [18] | Removal of systemic artifacts from fNIRS signals [18] | |

| CSP Algorithm | Common Spatial Pattern for dimensionality reduction [20] | Improved classification in EEG and fNIRS studies [20] | |

| GSP Framework | Graph Signal Processing for network analysis [2] | Structure-function relationship mapping [2] |

The choice between fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS depends fundamentally on the specific research questions, target brain regions, and practical constraints. fMRI with BOLD contrast remains the gold standard for non-invasive mapping of brain function with high spatial resolution, particularly valuable for studying subcortical structures and fine-grained cortical organization [15] [16]. The development of ultra-high field systems and advanced CBV techniques like VASO further enhances its specificity for investigating cortical layers and microcircuits [19]. EEG provides unparalleled temporal resolution for capturing neural dynamics at the millisecond scale, making it ideal for studying the timing of cognitive processes and functional brain connectivity [18] [2]. fNIRS offers a practical compromise with better motion tolerance and portability than fMRI, enabling brain imaging in more naturalistic settings and with populations challenging to study in traditional scanners [15] [10].

The future of neuroimaging lies not in identifying a single superior modality but in strategically combining complementary techniques. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI provides both high temporal and spatial resolution [2], while integrated fMRI-fNIRS approaches enable the validation of fNIRS signals against the established gold standard of BOLD fMRI [10]. As computational methods advance, particularly in machine learning and multimodal data fusion, researchers will increasingly extract insights that transcend the limitations of any single technique, ultimately providing a more comprehensive understanding of human brain function in health and disease.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) represents a rapidly advancing neuroimaging technology that utilizes near-infrared light to non-invasively monitor cerebral hemodynamics associated with neural activity. As a portable and flexible alternative to traditional neuroimaging methods, fNIRS has carved out a significant niche in neuroscience research, particularly for studying cortical brain function in naturalistic settings and with populations that challenge the limitations of other modalities. The fundamental principle underlying fNIRS stems from the discovery that biological tissues exhibit relative transparency to light in the near-infrared spectrum (650-950 nm), creating an "optical window" through which researchers can probe cortical activity [21] [22]. This optical property, combined with the differential absorption characteristics of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin, enables fNIRS to track the hemodynamic responses that accompany neuronal activation through neurovascular coupling mechanisms [23] [15].

The growing importance of fNIRS in neuroscience coincides with increasing recognition that no single neuroimaging modality can fully capture the brain's complexity. Consequently, multimodal approaches that integrate complementary techniques have gained prominence, with fNIRS serving as a bridge between the high temporal resolution of electroencephalography (EEG) and the superior spatial resolution of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [10] [23]. This review systematically examines the technical foundations of fNIRS, its comparative advantages and limitations relative to fMRI and EEG, experimental protocols for its application, and emerging trends that combine these modalities to advance our understanding of brain function in diverse contexts, from laboratory settings to real-world environments.

Technical Foundations of fNIRS

Fundamental Physical Principles

The operational principle of fNIRS relies on the transmission and absorption of near-infrared light as it passes through biological tissues. When neurons become active, they trigger a hemodynamic response that increases cerebral blood flow to the region, altering the local concentrations of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR). These hemoglobin species possess distinct absorption spectra in the near-infrared range, with HbR absorbing more light at wavelengths below approximately 810 nm (the isosbestic point) and HbO absorbing more light above this point [21] [24]. By emitting light at multiple wavelengths (typically 2-4 wavelengths between 650-950 nm) and measuring its attenuation after passing through the scalp, skull, and brain tissue, fNIRS can quantify changes in HbO and HbR concentrations using a modified version of the Beer-Lambert Law [21] [23].

The modified Beer-Lambert law describes the relationship between light attenuation and chromophore concentration as:

OD = log₁₀(I₀/I) = ε·[X]·l·DPF + G

Where OD represents optical density, I₀ and I are incident and detected light intensities respectively, ε is the extinction coefficient of the chromophore, [X] is chromophore concentration, l is the distance between source and detector, DPF is the differential pathlength factor accounting for light scattering in tissue, and G is a geometry-dependent factor [21]. Using a dual-wavelength system, changes in HbO and HbR concentrations can be solved from the matrix equation derived from differential absorption measurements.

fNIRS Measurement Configurations

fNIRS systems employ different technological approaches to measure hemodynamic responses, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Continuous Wave (CW) Systems: These most common fNIRS systems use light sources with constant intensity and frequency. They measure light attenuation but cannot directly determine absolute photon pathlength, providing only relative changes in hemoglobin concentration. Their advantages include simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high temporal resolution, making them suitable for many research and clinical applications [21].

- Frequency Domain (FD) Systems: FD systems utilize amplitude-modulated light sources (typically near 100 MHz) and measure both light attenuation and phase shift. This approach enables direct measurement of absorption and scattering coefficients, allowing for absolute quantification of hemoglobin concentrations without requiring separate pathlength information [21].

- Time Domain (TD) Systems: These systems introduce short pulses of light (picosecond range) and measure the temporal distribution of photons as they exit the tissue. This "time-of-flight" measurement provides the most detailed information about tissue optical properties and can distinguish between absorption and scattering changes while offering depth resolution [21].

In typical fNIRS configurations, light emitter and detector optodes are placed ipsilaterally on the scalp surface, with recorded measurements resulting from back-scattered light following elliptical pathways through cortical tissues. The penetration depth of near-infrared light is approximately 1-3 cm beneath the scalp, limiting fNIRS sensitivity primarily to superficial cortical regions [21] [22]. Spatial resolution depends on the source-detector separation distance, generally ranging from 1-3 cm, with greater separation providing deeper penetration but reduced spatial resolution due to increased light scattering [10] [24].

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

fNIRS, fMRI, and EEG each offer distinct advantages and limitations for neuroimaging research. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their key technical characteristics:

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Parameter | fNIRS | fMRI | EEG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate (1-3 cm) [24] | High (mm to sub-mm) [10] [24] | Low (source localization challenges) [25] [24] |

| Temporal Resolution | Moderate (0.1-10 Hz) [24] | Slow (seconds) [10] [24] | Very high (millisecond range) [25] [24] |

| Portability | High [26] [15] | Low [26] [15] | Moderate to high [25] |

| Motion Tolerance | High [26] [24] | Low [26] [24] | Moderate [25] [24] |

| Depth Sensitivity | Superficial cortex (1-3 cm) [10] [22] | Whole brain [10] [15] | Cortical surface, limited to deeper structures [25] |

| Measurement Type | Hemodynamic (indirect) [21] [23] | Hemodynamic (indirect) [10] [15] | Electrophysiological (direct) [25] [23] |

| Cost | Low to moderate [26] [24] | High [26] [24] | Low [25] |

| Naturalistic Testing | Excellent [26] [15] | Poor [26] [15] | Good [25] |

Complementary Strengths and Limitations

The comparative analysis reveals a compelling pattern of complementary strengths and limitations across the three modalities. fMRI excels in spatial localization throughout the entire brain, including deep structures, making it ideal for precise mapping of neural networks [10] [15]. However, its practical limitations include sensitivity to motion artifacts, requirement for subjects to remain supine and stationary, loud acoustic noise, and limited accessibility due to high costs [26] [15]. These constraints restrict its utility for studying naturalistic behaviors, populations with movement disorders, or children.

EEG provides direct measurement of neural electrical activity with millisecond temporal resolution, capturing rapid neural dynamics associated with sensory processing, cognitive functions, and brain states [25] [23]. Its limitations include poor spatial resolution due to the blurring effect of the skull and scalp on electrical signals, sensitivity to muscle and motion artifacts, and challenges in localizing activity to specific brain regions [25] [23].

fNIRS occupies a unique middle ground, offering better spatial resolution than EEG for cortical regions while providing greater portability and motion tolerance than fMRI [26] [15]. Its relative silence, safety, and compatibility with metal implants further expand its applicability to diverse populations and environments, including bedside monitoring, developmental studies, and rehabilitation settings [26] [24]. However, fNIRS cannot investigate subcortical structures and offers lower spatial resolution compared to fMRI [10] [26].

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Representative Experimental Designs

fNIRS has been successfully employed across diverse experimental paradigms. The table below summarizes key applications and their methodological considerations:

Table 2: Experimental Paradigms Using fNIRS and Multimodal Approaches

| Research Domain | Experimental Task | Measured Signals | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Control | Motor execution, observation, and imagery | fNIRS (HbO, HbR) + EEG | Shared activation in left inferior parietal lobe across conditions; multimodal fusion identified Action Observation Network | [6] |

| Schizophrenia Research | Verbal fluency tasks, working memory | fNIRS (HbO) | Reduced prefrontal HbO signals during cognitive tasks correlated with symptom severity | [24] |

| Vestibular Function | Balance task using Wii Fit ski game | fNIRS (HbO, HbR) | Activation in superior temporal gyrus modulated by task difficulty; demonstrates utility in dynamic tasks | [22] |

| Brain Network Connectivity | Resting state vs. motor imagery | fNIRS + EEG + structural connectivity | Structure-function coupling varies across brain states and follows unimodal-transmodal gradient | [2] |

| Cognitive Neuroscience | Various cognitive tasks in natural settings | fNIRS (HbO, HbR) | Validated fNIRS as reliable alternative to fMRI for cortical measurement during functional tasks | [10] [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Motor Execution, Observation, and Imagery

A representative multimodal experimental protocol from [6] illustrates the integrated application of fNIRS and EEG. This study investigated the Action Observation Network (AON) during motor execution (ME), motor observation (MO), and motor imagery (MI) using simultaneous fNIRS-EEG recordings.

Participants and Setup:

- Sixty healthy adults participated, with 21 included in final analysis after quality control

- A 24-channel continuous-wave fNIRS system (Hitachi ETG-4100) measuring HbO and HbR at 695 nm and 830 nm wavelengths

- A 128-electrode EEG system (Electrical Geodesics, Inc.) embedded with fNIRS optodes in the same cap

- Optodes positioned over sensorimotor and parietal cortices to cover AON regions

- 3D magnetic digitizer (Fastrak, Polhemus) used to record optode positions relative to anatomical landmarks

Experimental Paradigm:

- Participants sat face-to-face with an experimenter across a table

- Three conditions: (1) ME: participant grasped and moved a cup upon audio cue; (2) MO: participant observed experimenter performing the same action; (3) MI: participant imagined performing the action without movement

- Trial structure included baseline, preparation, task execution, and rest periods

- Multiple trials per condition with counterbalanced presentation

Data Processing and Analysis:

- fNIRS data processed using modified Beer-Lambert law to compute HbO and HbR concentration changes

- EEG data processed for event-related potentials and spectral power changes

- Structured sparse multiset Canonical Correlation Analysis (ssmCCA) used to fuse fNIRS and EEG data

- Unimodal and multimodal analyses compared to identify consistent activation patterns

This protocol demonstrates the comprehensive approach required for multimodal neuroimaging, including careful experimental design, simultaneous data acquisition, sophisticated signal processing, and advanced fusion algorithms to extract complementary information from both modalities.

Multimodal Integration: Synergistic Approaches

fNIRS-EEG Integration

The combination of fNIRS and EEG represents a particularly powerful multimodal approach that captures both hemodynamic and electrophysiological aspects of brain function [23]. The integration rationale stems from the neurovascular coupling phenomenon - the inherent relationship between neural electrical activity and subsequent hemodynamic responses [23]. Simultaneous fNIRS-EEG measurements provide built-in validation for identified neural activity through concordance between electrical and hemodynamic responses [23] [6].

Methodologically, fNIRS-EEG integration can be implemented through three primary approaches:

- EEG-informed fNIRS analyses: Using EEG features to guide fNIRS signal processing or interpretation

- fNIRS-informed EEG analyses: Employing hemodynamic information to constrain EEG source localization

- Parallel analyses: Processing both modalities separately then integrating results through fusion algorithms like structured sparse multiset Canonical Correlation Analysis (ssmCCA) [23] [6]

Technical considerations for simultaneous fNIRS-EEG include compatible sensor placement using international 10-20 system, hardware synchronization via triggers or shared clocks, motion artifact management, and integrated data analysis pipelines [25] [23]. The resulting complementary data provides both high temporal resolution from EEG and improved spatial localization from fNIRS, enabling more comprehensive characterization of brain dynamics [23] [6].

fNIRS-fMRI Integration

Combining fNIRS with fMRI creates another valuable multimodal approach that leverages fMRI's high spatial resolution for whole-brain coverage and fNIRS's practical advantages for naturalistic testing [10] [15]. Since both modalities measure hemodynamic responses related to neural activity, their signals show strong correlation (spatial correlations up to R=0.86 reported in simultaneous recordings) [22] [15].

Integration methodologies include:

- Synchronous detection: Simultaneous data acquisition to directly correlate signals

- Asynchronous detection: Separate sessions using similar paradigms to validate findings across modalities [10]

This combination is particularly valuable for clinical applications where fMRI provides detailed anatomical localization and fNIRS enables bedside monitoring of treatment progress [10] [24]. Technical challenges include electromagnetic interference in MRI environments, hardware compatibility, and data fusion complexities, though ongoing innovations in MRI-compatible fNIRS probes are addressing these limitations [10].

Visualization of fNIRS Principles and Experimental Workflow

This diagram illustrates the fundamental principles of fNIRS measurement and its implementation in experimental workflows, particularly highlighting its integration with complementary modalities like EEG in multimodal research designs.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for fNIRS Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Systems | Hitachi ETG-4100, TechEn CW6 | Continuous wave fNIRS systems for measuring HbO/HbR changes | [22] [6] |

| EEG Systems | Electrical Geodesics (EGI) systems, BrainAmp | High-density EEG systems for electrical activity recording | [23] [6] |

| Digitization Equipment | Polhemus Fastrak, 3D magnetic digitizers | Records precise sensor positions for anatomical coregistration | [22] [6] |

| Analysis Software | HOMER3, NIRS Toolbox, AtlasViewer | Processing fNIRS signals, statistical analysis, visualization | [21] |

| Multimodal Analysis Tools | Structured Sparse Multiset CCA (ssmCCA) | Data fusion technique for integrating fNIRS and EEG signals | [6] |

| Experimental Paradigms | Verbal Fluency Task, N-back, Motor Execution/Observation/Imagery | Standardized tasks to elicit specific cognitive processes | [24] [6] |

| Quality Metrics | Scalp-Coupled Index (SCI), Global Variance in Temporal Derivative (GVTD) | Assess signal quality and identify motion artifacts | [2] |

fNIRS has established itself as a valuable neuroimaging modality that balances spatial and temporal resolution with practical advantages of portability, motion tolerance, and accessibility. While limited to cortical regions and offering moderate spatial resolution compared to fMRI, its capacity for naturalistic testing and compatibility with diverse populations has expanded the scope of neuroscientific inquiry beyond traditional laboratory constraints. The future of fNIRS lies increasingly in multimodal approaches that leverage its complementary strengths with EEG's millisecond temporal resolution and fMRI's whole-brain coverage. As technological innovations continue to address current limitations in depth sensitivity and spatial resolution, and as analysis methods become increasingly sophisticated through machine learning and advanced fusion algorithms, fNIRS is poised to make increasingly significant contributions to cognitive neuroscience, clinical diagnosis, and therapeutic monitoring.

Neurovascular coupling (NVC) is the fundamental physiological process that links neural electrical activity to subsequent local hemodynamic changes in the brain. This mechanism forms the theoretical cornerstone for integrating neuroimaging techniques that measure electrical potentials (like EEG) with those that measure hemodynamic responses (like fMRI and fNIRS). When neurons become active, they trigger a complex cascade of events—involving neurons, astrocytes, and vascular cells—that leads to an increase in local cerebral blood flow, delivering oxygen and nutrients to meet the metabolic demands of firing neurons [27]. This response, known as functional hyperemia, results in a characteristic hemodynamic signature: an increase in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and a decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the active region [27] [28]. It is this tightly coupled relationship that allows researchers to infer underlying electrical brain activity from hemodynamic measurements and, conversely, to interpret the vascular implications of electrical events. Understanding NVC is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for designing robust neurocognitive studies and accurately interpreting data across the dominant non-invasive neuroimaging modalities.

Core Principles of Neurovascular Coupling

The process of neurovascular coupling is a precisely orchestrated sequence of events. Following synaptic activity and the release of neurotransmitters, a signaling pathway is initiated that ultimately leads to the relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and the dilation of arterioles [27]. This vasodilation causes a rapid increase in local cerebral blood flow (CBF) to the activated brain area. The resulting hemodynamic response function (HRF) is characterized by a temporal delay of 1-2 seconds post-stimulus, peaking around 5-6 seconds before returning to baseline [27]. This overcompensation of blood flow creates an oversupply of oxygen, manifesting as the increased HbO and decreased HbR that fNIRS and fMRI's Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal detect [27] [10]. The integrity of this coupling is essential for healthy brain function, and its disruption is implicated in a range of neurological conditions, from schizophrenia to the long-term effects of concussion [24] [29].

Visualizing the Neurovascular Coupling Process

The following diagram illustrates the sequential relationship between neural activity, the neurovascular coupling mechanism, and the resulting signals measured by different imaging modalities.

Comparative Analysis of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

The theoretical framework of NVC allows for the direct comparison of the primary non-invasive neuroimaging modalities. Each technique captures a different facet of the brain's response to stimulation, governed by its inherent technical strengths and limitations. The table below provides a quantitative overview of these core characteristics.

Table 1: Technical comparison of key neuroimaging modalities

| Parameter | EEG | fNIRS | fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | Electrical activity from postsynaptic potentials [28] [30] | Hemodynamic changes (HbO & HbR) [27] [28] | Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal [10] |

| Temporal Resolution | Very High (milliseconds) [10] [30] | Moderate (0.1 - 10 Hz) [10] [24] | Low (seconds) [10] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (source localization challenges) [28] [24] | Moderate (1-3 cm) [10] [24] | High (mm to sub-mm) [10] [24] |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface [30] | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm) [24] [30] | Whole-brain (cortical & subcortical) [10] |

| Portability | High [10] [30] | High [10] [24] | Low (immobile scanner) [10] |

| Motion Tolerance | Moderate to Low [24] [30] | High [10] [24] | Low [10] |

| Best Use Cases | Fast cognitive tasks, ERPs, sleep studies [30] | Naturalistic studies, child development, rehabilitation [24] [30] | Precise spatial localization, deep brain structures [10] |

Methodological and Practical Considerations

Beyond core technical specifications, several practical factors influence the choice of modality for a given research question.

Table 2: Methodological and practical considerations for neuroimaging

| Consideration | EEG | fNIRS | fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Advantage | Millisecond-level tracking of brain dynamics [28] | Balances portability with better spatial resolution than EEG; ideal for naturalistic settings [10] [24] | Gold standard for whole-brain spatial localization [10] |

| Primary Limitation | Poor spatial resolution and sensitivity to deep sources [28] | Limited to superficial cortical layers; cannot probe subcortical activity [10] | Very low temporal resolution; noisy, restrictive environment [10] |

| NVC Relationship | Measures the cause (electrical neural activity) [28] | Measures the effect (hemodynamic response) [27] | Measures the effect (BOLD signal, a hemodynamic correlate) [10] |

| Cost | Generally lower [30] | Low to moderate [24] [30] | High [24] [30] |

Experimental Evidence: Validating Neurovascular Coupling

The theoretical principles of NVC are consistently demonstrated and validated through empirical multimodal studies. These experiments often combine an electrical recording technique (EEG) with a hemodynamic modality (fNIRS or fMRI) to observe both sides of the coupling simultaneously.

Auditory Intensity-Dependent Amplitude Changes

A 2023 study explicitly designed to investigate NVC employed a paradigm of intensity-dependent amplitude changes (IDAP) [27]. The experimental protocol involved presenting participants with tones of varying intensities (77.9 dB, 84.5 dB, and 89.5 dB) while simultaneously recording EEG and fNIRS [27]. The results demonstrated a clear coupling: as the tone intensity increased, so did the amplitude of the ERP components (N1 and P2), indicating greater neural electrical response [27]. In parallel, the fNIRS data showed a corresponding increase in HbO and a decrease in HbR in the auditory and prefrontal cortices [27]. A Spearman correlation analysis further solidified this link, revealing a significant relationship between the N1 amplitude from EEG and the HbR concentration in the left auditory cortex measured by fNIRS [27]. This study provides a direct, within-experiment validation of the neurovascular coupling phenomenon.

A Representative Experimental Protocol

The following diagram outlines the workflow of a typical simultaneous EEG-fNIRS experiment, as used in studies investigating semantic decoding and NVC [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful multimodal research hinges on the appropriate selection of equipment and analytical tools. The following table details essential components for a study integrating EEG and fNIRS to investigate neurovascular coupling.

Table 3: Essential materials and tools for multimodal NIRS-EEG research

| Item | Function/Description | Example in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous EEG-fNIRS System | Integrated or synchronized hardware for co-registration of electrical and hemodynamic signals. | Systems used in auditory and semantic imagery paradigms to capture complementary data streams [27] [31]. |

| fNIRS Optodes | Sources that emit near-infrared light and detectors that measure its attenuation after passing through tissue. | Placed over auditory cortex (T7/T8) or prefrontal cortex to measure HbO/HbR changes during tasks [27] [32]. |

| EEG Electrodes | Sensors placed on the scalp according to the 10-20 system to record voltage fluctuations from neural activity. | Used to record event-related potentials (ERPs) like N1 and P2 in response to sensory stimuli [27]. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Software to deliver controlled auditory, visual, or cognitive tasks with precise timing. | Presenting intensity-varying tones or "Where's Wally" paradigms to evoke a measurable brain response [27] [29]. |

| Data Synchronization Interface | Hardware (e.g., TTL pulses) or software to align EEG and fNIRS data streams with sub-second precision. | Critical for correlating the fast ERP components with the slower hemodynamic response [31]. |

| Preprocessing & Fusion Algorithms | Software tools for artifact removal (e.g., motion, heartbeat) and joint data analysis (e.g., jICA, machine learning). | Used to address analytical variability and fuse features from both modalities for a unified result [33] [28]. |

Integrated Data Analysis and Workflow

The path from raw, simultaneous recordings to meaningful insights about NVC requires careful and often parallel data processing. The following diagram summarizes the analysis workflow that leads to a fused interpretation.

The choice between fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS is not a matter of identifying a single superior technology, but rather of strategically selecting the right tool for the specific research question. fMRI remains the gold standard when the objective is precise spatial localization of activity across the entire brain, including deep subcortical structures [10]. EEG is unparalleled for investigating the rapid temporal dynamics of brain function, such as the sequence of cognitive processes unfolding in the tens to hundreds of milliseconds after a stimulus [30]. fNIRS occupies a crucial middle ground, offering a favorable balance of moderate spatial resolution, good portability, and high motion tolerance, making it ideally suited for studies of cortical function in naturalistic environments or with populations that cannot tolerate the fMRI scanner [10] [24].

Ultimately, the theoretical link of neurovascular coupling empowers researchers to not only choose wisely but also to combine these modalities synergistically. A simultaneous EEG-fNIRS setup, for instance, provides a more comprehensive picture by capturing the immediate electrical neural response and its consequent hemodynamic manifestation within a portable and flexible experimental framework [28] [31]. As the field moves toward more naturalistic and clinically translatable research, understanding and leveraging the strengths of each modality through the common lens of neurovascular coupling will be paramount for future discoveries in human neurocognition.

Choosing Your Tool: Methodological Strengths and Application Scenarios in Design Neurocognition

In design neurocognition research, selecting the appropriate brain imaging technique is paramount for generating valid and insightful data. The core trade-off in this selection process almost invariably involves balancing temporal resolution—the ability to track rapid changes in brain activity over time—against spatial resolution—the precision in locating where this activity occurs in the brain. This guide provides an objective comparison of three prominent non-invasive neuroimaging modalities: functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). Understanding their complementary strengths and limitations enables researchers to align methodological capabilities with specific research questions, whether for fundamental cognitive science or applied drug development.

Technical Comparison of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

Fundamental Principles and Measured Signals

Each technique captures a distinct physiological correlate of neural activity, which fundamentally dictates its resolution characteristics.

- fMRI measures the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal, an indirect hemodynamic response linked to neural metabolism. When a brain region is active, a complex neurovascular coupling process leads to a localized change in the ratio of oxygenated to deoxygenated hemoglobin, which alters the local magnetic properties of blood [34] [26].

- EEG records electrical potentials on the scalp generated by the synchronized firing of large populations of cortical neurons, primarily pyramidal cells. These postsynaptic potentials represent the direct and instantaneous electrical activity of the brain [35] [23].

- fNIRS, like fMRI, is an indirect hemodynamic method. It uses near-infrared light to measure changes in the concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the superficial layers of the cortex, providing a measure of localized blood flow and oxygenation changes subsequent to neural firing [35] [36] [23].

Quantitative Resolution and Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes the key technical specifications of each modality, highlighting the inherent trade-offs.

Table 1: Technical Specification Comparison of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS

| Feature | fMRI | EEG | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| What It Measures | BOLD signal (indirect hemodynamic) [34] [26] | Electrical potentials (direct neural activity) [35] [23] | HbO & HbR concentration (indirect hemodynamic) [35] [23] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (seconds) [34] | Very High (milliseconds) [35] | Moderate (seconds) [35] |

| Spatial Resolution | High (millimeter-level) [26] [37] | Low (centimeter-level) [35] | Moderate (centimeter-level, cortical) [35] [36] |

| Depth of Measurement | Whole brain | Cortical surface [35] | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm deep) [35] [36] |

| Portability | Low (stationary scanner) | High (wearable systems available) [35] [23] | High (wearable and mobile formats) [35] [23] [26] |

| Tolerance to Movement | Low (highly sensitive) [26] | Moderate (susceptible to artifacts) [35] | High (relatively robust) [35] [26] |

| Typical Experimental Environment | Highly controlled lab [35] | Controlled lab or shielded room | Naturalistic, real-world settings [35] |

Signaling Pathways and Neurovascular Coupling

The relationship between electrical neural events and the subsequent hemodynamic response is central to understanding fMRI and fNIRS signals. This process, known as neurovascular coupling, is illustrated below.

Figure 1: Signaling Pathways for EEG, fMRI, and fNIRS. EEG measures the direct electrical signal (blue), while fMRI and fNIRS measure indirect hemodynamic responses (green) that are coupled to neural activity via metabolic demand (red).

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Common Experimental Designs

Robust experimental design is critical for isolating brain activity related to a specific cognitive process.

- Block Designs: Frequently used in fMRI and fNIRS studies due to the slow nature of the hemodynamic response. This design alternates extended periods (e.g., 30 seconds) of an experimental condition with a control condition, allowing the BOLD or HbO/HbR signal to rise and stabilize. It is optimal for detecting the presence of activation and is statistically powerful [34].

- Event-Related Designs: Suitable for all three modalities but analyzed differently. Brief, discrete trials are presented in a randomized or jittered sequence. In fMRI/fNIRS, this allows the hemodynamic response to return to baseline between trials, enabling the analysis of the response's shape and timing to different trial types [34]. In EEG, it is used to average many trials to extract Event-Related Potentials (ERPs), which are voltage fluctuations time-locked to a sensory, cognitive, or motor event with millisecond precision.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Workflows

Each modality requires a specialized data processing pipeline to transform raw recordings into interpretable brain activity maps or metrics. The general workflow for a multimodal experiment is shown below.

Figure 2: Concurrent fNIRS-EEG Experimental Workflow. Data is acquired simultaneously, processed through separate pipelines, and then integrated [23].

Detailed Preprocessing Steps:

- fMRI Preprocessing: Key steps include slice-time correction, motion realignment to correct for head movement, coregistration to a structural image, spatial normalization to a standard brain template, and spatial smoothing to increase signal-to-noise ratio [34].

- EEG Preprocessing: This involves filtering to remove low- and high-frequency noise, segmenting data into epochs, rejecting or correcting artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity), and re-referencing the electrodes. To improve spatial resolution, techniques like Current Source Density (CSD) or Surface Laplacian can be applied, which reduce the blurring effect of the skull and scalp [38].

- fNIRS Preprocessing: Raw light intensity is converted to optical density and then to HbO and HbR concentration changes using the Modified Beer-Lambert Law [23]. Processing includes filtering to remove cardiac and respiratory pulsations, correcting for motion artifacts, and sometimes converting channel data to a specific brain region using anatomical atlases [39].

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists essential tools and concepts used in neurocognitive experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Neurocognition

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Relevance in Research |

|---|---|---|

| International 10-20 System | Standardized EEG electrode placement system based on skull landmarks [35] [36]. | Ensures consistent and reproducible sensor placement across subjects and studies for EEG and fNIRS. |

| General Linear Model (GLM) | A statistical framework for modeling brain activity based on experimental design [34]. | The primary method for analyzing fMRI and fNIRS data to identify voxels or channels significantly activated by a task. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A blind source separation technique to isolate statistically independent signals from data [40]. | Used in EEG to remove artifacts (e.g., eye blinks) and in fMRI to identify resting-state networks. |